Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) remains one of the most devastating infectious diseases worldwide. The burden of TB is alarmingly high in developing countries, where diagnosis latent TB infection (LTBI), Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB), drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB), HIV-associated TB, and paediatric TB is still a challenge. This is mainly due to delayed or misdiagnosis of TB, which continues to fuel its worldwide epidemic. The ideal diagnostic test is still unavailable, and conventional methods remain a necessity for TB diagnosis, though with poor diagnostic ability. The nanoparticles have shown potential for the improvement of drug delivery, reducing treatment frequency and diagnosis of various diseases. The engineering of antigens/antibody nanocarriers represents an exciting front in the field of diagnostics, potentially flagging the way toward development of better diagnostics for TB. This chapter discusses the presently available tests for TB diagnostics and also highlights the recent advancement in the nanotechnology-based detection tests for M. tuberculosis.

Keywords: M. tuberculosis, Nano diagnostics, Nanoparticles

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by an aerobic, acid-fast bacillus, that is, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis), to humans, and it is still a major public health problem worldwide (Kerantzas and Jacobs 2017). For many decades, it has continued to pose a significant threat to human health (WHO 2017). The situation becomes critical by the increasing incidence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) forms of M. tuberculosis, that is, resistance to both isoniazid (INH) and rifampicin (RIF) and now, extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis (XDR-TB) strains, that is, MDR TB strains plus resistance to any fluoroquinolone and at least one of three injectable second-line drugs (amikacin, kanamycin, or capreomycin) that is virtually untreatable (CDC 2006). It has been estimated that almost billions of peoples will be newly affected with TB between 2000 and 2020. WHO estimated 10.4 million new cases and more than 1.3 million deaths in 2016 (WHO 2017). Among the estimated 10.4 million incident cases, 10% were children and 35% were female. In 2016, 153,119 cases of multidrug-resistant TB and rifampicin-resistant TB (MDR/RR-TB) were reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) globally (WHO 2017). Most of the TB cases reported in 2016 occurred in Asia (56%) and the African Region (29%). The smaller proportions of cases were reported in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (8%), European Region (4%), and the Region of the Americas (3%).

A fast and reliable laboratory diagnosis would help in the control of TB especially in the high burden countries. Current TB diagnostics mostly depend on the identification of M. tuberculosis by acid-fast bacilli (AFB) staining directly from clinical specimens, culture, and molecular tests. Although, smear microscopy permits the rapid detection of mycobacteria in clinical samples, it has comparatively low sensitivity and requires at least 5 × 103 bacilli/ml in the specimen (Desikan 2013). Also, it has a higher failure rate in children and immuno-compromised groups such as Acquired Immuno Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) (Desikan 2013; Tuberculosis Division 2005).

The solid culture method is based on the visible appearance of growth on the medium, but it takes very long time for detection (up to 60 days), while automated liquid culture system, that is, Mycobacterial Growth Indicator Tube (MGIT) 960 system (Recommended by WHO for liquid culture and drug susceptibility test) is slightly better than solid culture due to reduced time duration required (42 days) for bacilli detection (Chihota et al. 2010; Lawson et al. 2013). However, it requires longer duration to obtain the results and also specific laboratory facilities, which may be unreachable by resource-limited or poor countries. Immunological approaches, such as the Tuberculin Skin Test (TST) and IFN-Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) have been developed for the detection of TB/latent TB infection (LTBI) (Lagrange et al. 2013, 2014; Pai et al. 2004). However, both TST and IGRA failed to distinguish between latent TB and active TB infection in the high burden countries (Chegou et al. 2009; Ra et al. 2011).

Current nucleic acid amplification-based tests (NAAT), that is, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) (Gopinath and Singh 2009), Xpert MTB/Rif assay (Rufai et al. 2017), Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) (Kumar et al. 2014) and Line Probe Assay (LPA) (Rufai et al. 2014) are able to detect M. tuberculosis within few hours to days in suspected TB patients than culture methods and play an important role in the patient care and TB control programmes.

Despite all advances in TB diagnosis landscape, there is no accurate, rapid, inexpensive, point-of-care assay available for M. tuberculosis detection, well-matched for children, extrapulmonary TB (EPTB) and HIV associated TB (HIV-TB)(Kozel and Burnham-Marusich 2017). Furthermore, in developing countries, like India and Pakistan, where resources are very limited and the requirement of sophisticated, costly instruments becomes an extraburden due to the requirement of trained technicians to perform the tests, which directly or indirectly increases the diagnostic cost. Therefore, an improvised version and/or new diagnostic test/techniques are urgently required for the prevention and treatment of M. tuberculosis infection to fulfil the unmet demands (Singh et al. 2015). From these viewpoints, diagnostic test based on nanotechnology can offer fast and efficient alternative methods for TB detection (Caliendo et al. 2013).

Nanotechnology, known as general purpose technology, utilizes nanoscale molecules ranging from 1 nm to100 nm. It plays a key role in the development of many fields such as automotive, textile, electronics, food, healthcare, and due to its unique characteristics, it is useful in optical, mechanical, magnetic, catalytic, and electrical perspectives (Chaturvedi et al. 2012). For the past several decades, biomedical applications such as tissue engineering, drug delivery, bioimaging, and nanodiagnostics have been developed by utilizing the concept of nanotechnology. Among these applications, nanodiagnostics-based rapid test has drawn more and more attention for infectious diseases due to its unique characteristics in the early detection with high sensitivity and specificity (Wang et al. 2017).

These potential of nanodiagnostics opened the door for development of portable, robust, and affordable POCs, which can detect infectious diseases very efficiently (Sharma and Bhargava 2013; Wang et al. 2017; Singh et al. 2017). In this direction, various innovative and efficient nanodiagnostics have been developed by researchers for infectious diseases including TB. Laksanasopin et al. (2015) developed a smartphone-based POC to diagnose infectious diseases by connecting traditional immunoassay into a smartphone via accessories such as dongle (Laksanasopin et al. 2015). Hence, nanodiagnostics-based POCs are promising tools for rapid detection of infectious diseases and could be exploited in the near future for different clinical requirements.

In this chapter, we highlight prospects of the advances in the nanotechnology-based diagnostic methods that can offer better solutions for diagnosis of M. tuberculosis infections.

Diagnosis of Tuberculosis

The TB diagnostic method can be divided into three categories: conventional methods, immunological methods, and new diagnostic methods.

Conventional Methods

Microscopy is possibly the earliest and most rapid procedure that can be performed in the laboratory to detect the presence of AFB, Adenosine Deaminase Activity (ADA), culture (egg-based solid media like Lowenstein–Jensen medium, agar-based medium like Middlebrook 7H10), which is shown in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1.

Summary of the available diagnostic tests/methods for TB

| Technology, test | Stage of development | Developer(s)/ supplier(s) | Level of the health system | DST utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Conventional method | ||||

| Direct visualization (Microscopy) | ||||

| Conventional microscopy with acid-fast staining | In routine use | Multiple | Microscopy | No |

| Fluorescent microscopy with nonspecific cell-wall staining | In routine use | Multiple | Microscopy | No |

| Fluorescent microscopy with LED light source | In routine use | Various | Microscopy | No |

| Growth-based detection (Culture) | ||||

|

Conventional solid media LJ, Middlebrook 7H10/7H11 agar, 7H9/7H12/Dubos medium |

Commercialized reagents and prepared media | Multiple | Referral | Yes |

| Automated liquid culture systems MGIT 960, BacT/ALERT 3D, VersaTREK Myco, etc. | Commercialized, under study for feasibility and impact of use in resource-limited settings | BD, BioMerieux, Thermofisher | Referral | Yes |

| MODS assay, thin-layer culture | Academic evaluations published | Non-commercial testing methods | Referral | Yes |

| Phage-based detection | Commercialized, improved test in development | Biotec | Referral | Yes |

| B: Immunological method | ||||

| Latent Tuberculosis Infection detection | ||||

| Tuberculin skin test with PPD | Commercialized | Multiple | Microscopy | No |

| Whole-blood IFN-γ release assay | Commercialized; in evaluation for disease-endemic countries | Cellestis | Referral | No |

| ELISPOT IFN-γ release assay | Commercialized; in evaluation for disease-endemic countries | Oxford Immunotech | Referral | No |

| Antigen detection (Immunodiagnosis) | ||||

| TB-derived antigen detection in urine or other clinical material | In development | Various | Research centre | No |

| TB-derived antigen detection in exhaled air/breath | In evaluation | Rapid Biosensor Systems | Health centre | No |

| Antibody detection (Immunodiagnostic) | ||||

| Detection of diagnostic antibody responses to TB | WHO banned all existing commercial test | Various | Health centre | No |

| C: Molecular detection | ||||

| Automated, non-integrated NAAT | Commercialized | GenProbe,Roche, | Referral | No |

| Automated, integrated NAAT | Commercialized | Cepheid | Referral | Yes |

| Simplified manual NAAT (LAMP) | In evaluation | Eiken | Referral | No |

| Non-amplified probe detection | In development | Investigen, | Microscopy | No |

| GeneXpert | Commercialized | Cepheid, USA | Referral | Yes |

Modified from Pai and O’Brien (2008)

Immunological Methods

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), tuberculin skin test (TST), interferon-gamma determination, and tuberculin test are discussed in Table 11.1 above.

New Diagnostic Methods

Automated culture methods (BECTEC 460 TB (Aggarwal et al. 2008), BECTEC MGIT™ 960 (Rodrigues et al. 2009), Versa TREK and BacT/ALERT 3D) (Mirrett et al. 2007), Nucleic acid amplification methods (amplified MTD, amplified M. tuberculosis direct test (AMTD) (Goessens et al. 2005; Reischl et al. 1998), transcriptase-mediated amplification system and amplicor MTB test (Wang and Tay 1999), Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) (Gopinath and Singh 2009), LAMP (Yadav et al. 2017), Real-time PCR (Watanabe Pinhata et al. 2015), LPA (Desikan et al. 2017), Xpert MTB/RIF assay (Osman et al. 2014). Genetic identification methods: PCR restriction-enzyme analysis, RFLP (Gómez Marín et al. 1995), Spoligo typing (Mistry et al. 2002), DNA probes (Badak et al. 1999) and DNA sequencing (Brown et al. 2015), etc. are shown in Table 11.1. Other molecular tests that are under development or under evaluation have been mentioned in Table 11.2.

Table 11.2.

Tuberculosis diagnostics pipeline (2016): Products in later-stage development or on track for evaluation by WHO

| New molecular diagnostics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. No. | Test | Type | Developer(s)/ supplier(s) | Status | Comments |

| 1. | BD MAX MTB assay | qPCR for MTB in automated BD MAX | Becton, Dickinson | 100% sensitivity and 97.1% specificity with smear-positive samples (Rocchetti et al. 2016) | Under the evaluation stage |

| 2. | EasyNAT | Isothermal DNA amplification /lateral flow to detect MTB | Ustar | Poor sensitivity, especially for smear-negative specimens, in Tanzanian field study (Bholla et al. 2016; Mhimbira et al. 2015) | |

| 3. |

FluoroType MTB |

Semi-automated direct MTB detection; PCR in a closed system; results in 3 h | Hain Lifescience | Sensitivity 88%, specificity- 98% (Bwanga et al. 2015; Obasanya et al. 2017) | Marketed |

| 4. | GeneChip | RT-PCR for RIF + INH DR | CapitalBio | CCDCP and University of Georgia published a paper on 1400 samples from SW China (Sensitivity 83–94.6%, specificity 91.3–98%) (Zhang et al. 2018; Zhu et al. 2015) | Marketed |

| 5. |

Genedrive MTB/RIF |

Portable RT-PCR for MTB + RIF resistance | Epistem | Lower sensitivity (45.4%) (Shenai et al. 2016) | Marketed in India |

| 6. |

GenoType MTBDRplus |

Line probe assay for RIF + INH resistance | Hain Life science | (Sensitivity 90.3% and specificity 98.5%) (Nathavitharana et al. 2016) | WHO recommended |

| 7. | LiPA pyrazinamide | Line probe assay for PZA resistance | Nipro | High sensitivity (65.9–100%) and specificity (98.2–100%) (Rienthong et al. 2015) | Marketed |

| 8. | LiPA MDR-TB | Line probe assay for RIF + INH resistance | Nipro | Sensitivity 89% and 99.4% Specificity(Havumaki et al. 2017) | Marketed |

| 9. | REBA MTB-MDR | Line probe assay for RIF + INH resistance | YD Diagnostics | (Havumaki et al. 2017) | Marketed |

| 10. | REBA MTB-XDR | Line probe assay for FQ + SLID DR | YD Diagnostics | Initial study 2015 (Jaksuwan et al. 2018; Lee et al. 2015) | Marketed |

| 11. |

MeltPro TB/INH |

Closed-tube RT-PCR for INH DR | Zeesan Biotech |

3-site evaluation of 1096 clinical |

Chinese FDA-approved |

| 12. |

MeltPro TB/STR |

Closed-tube RT-PCR for streptomycin DR | Zeesan Biotech |

3-site evaluation of 1056 clinical Isolates (Zhang et al. 2015) |

WHO guidance pending |

| 13. | PURE-LAMP | Manual NAAT by LAMP for MTB detection | Eiken | Eddabra and AitBenhassou (2018) | WHO review |

| 14. |

Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra |

Next-generation cartridge-based detection of MTB + RIF resistance | Cepheid | Sensitivity (77–90%) and specificity (96–98%) (Arend and Soolingen 2018; Dorman et al. 2018) | Recommended by WHO (2017) |

| 15. | XpertOmini | Single cartridge mobile platform | Cepheid | FIND’s study results awaited | |

| 16. | Truenat MTB | Chip-based NAAT with RT-PCR on a handheld device for MTB | Molbio Diagnostics, Bigtec Labs | Sensitivity (99%) (Nikam et al. 2014) | FIND & ICMR studies underway |

| 17. | TB-LAMP | Single tube detection system | Eiken-Chemical Company, Japan | The sensitivity of TB-LAMP is lower than Xpert MTB/RIF assay but greater than smear microscopy (Gray et al. 2016; Pham et al. 2018) | Recommended by WHO |

Diagnostic Gaps Between Existing Technologies and Its Unmet Clinical Need

M. tuberculosis was identified more than a century ago, and its diagnosis in the developing world still remains a major healthcare issue owing to a number of challenges, listed below. First, M. tuberculosis is a slow-growing bacterium, and therefore it cannot provide direction for on-site patient care. Second, the PTB patient do not develop symptoms at the early stage of infection, which lead to delays in seeking patient care (Parsons et al. 2011; Kritski et al. 2013). Third, even the active PTB cases often exhibit low bacteria count of sputum thus making it difficult to detect with smear microscopy and other commonly used POC diagnostic tests in the developing world. Fourth, use of sputum and other invasive body fluids in the diagnosis of TB with existing techniques is more complex compared to blood and urine samples (Sharma et al. 2015).

The unavailability of accurate and validated biomarkers (for Active TB and LTBI infection) either derived from host or pathogen are due to inadequate knowledge of the host–pathogen interaction, pathogenesis, and protected immune response generated by M. tuberculosis during infection, which limited utility of rapid diagnostic test of TB (Goletti et al. 2016).

Despite exiting technologies, development of simple POCs test in the near future is still challenging in the current TB diagnostics pipeline (Pai and Nathavitharana 2014). Although Xpert MTB provides same-day detection, its use is limited by its cost and poor detection rate in extra-pulmonary tuberculosis ( EPTB) (Rufai et al. 2017). Hence, there is an urgent need of inexpensive TB diagnostic test for resource-limited settings to miniaturize TB diagnosis, which can be done by using a novel nanotechnology approach.

Nanotechnology

Nanoparticles

Nanoparticle (NP) is a small particle less than 100 nm in diameter. The unique property depends on the size and composition of the particles compared to atoms and other materials. These properties includes: (1) large to volume ratio (metal NP, in particular gold NP), (2) surface plasmon resonance, (3) Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS), (4) super-magnetization or ferromagnetic nanoparticles (e.g. iron oxide), (5) enhanced photoluminescence (semiconductor quantum dots), (6) high electric and heat conductivity, (7) potent surface catalytic activity (Gatoo et al. 2014; Khan et al. 2019). The combination of nanoparticles with biology has led to the development of various diagnostic test/devices, contrast agents, analytical tools, physical therapy, and drug delivery systems. Since biomolecules and cellular organelles lie in the nanosized range, NPs can be altered with various biomolecules, such as antibodies, nucleic acid, peptides (Jacob and Deigner 2018; Wang and Wang 2014). Such manipulations enable NPs to be extremely useful in both in vivo and in vitro biomedical research and applications (Curtis and Wilkinson 2001). A schematic presentation of a core/shell nanoparticle for multipurpose biomedical applications is shown in Fig. 11.1.

Fig. 11.1.

Outline of multifunctional nanoparticle in human health including molecular imaging, disease diagnostics, drug delivery and therapy (Adopted from Chatterjee et al. 2014)

Types of Nanoparticle-Based Platforms

The designing of nanodiagnostics are based on the binding of a labelled nanoparticle or probe to the target biomolecule, generates a quantifiable electric signal characteristic of the target biomolecules (Alharbi and Al-sheikh 2014). The most promising approaches include nanoparticles (carbon and gold nanoparticles), nanotubes, nanoshells, nanopores, quantum dots (QDs), and nanocantilever technologies, which display promising activity in the diagnostic applications (Capek 2016; Mancebo 2009). The QDs are semiconductor nanocrystals which are characterized by strong light absorbance, and they can be used as fluorescent labels/tag for the detection of biomolecules. The cantilevers and QDs are the most promising nanostructures, which are mainly characterized by high photostability, single-wavelength excitation, and size-tunable emission (Azzazy et al. 2006; Rizvi et al. 2010). Different types of nanostructure or nanodevices that are used for specific purposes are listed in Table 11.3.

Table 11.3.

Types of nanodevices used in clinical applications

| S. No | Nonodevices | Applications | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Cantilevers |  |

High thoughtful screening Protein biomarkers detection SNPs Gene expression detection |

| 2. | Carbon Nanotubes |  |

SNPs Protein biomarkers detection |

| 3. | Dendrimers |  |

Image contrast agents |

| 4. | Nanocrystals |  |

Improved formulation for poorly soluble drugs |

| 5. | Nanoparticles |  |

Target drug delivery MRI, USG image contrast agents Reporters of apoptosis |

| 6. | Nanoshell |  |

Tumour-specific imaging |

| 7. | Nanowires |  |

High thoughtful screening Disease protein biomarkers detection SNPs Gene expression analysis |

| 8. | Quantum dots |  |

Optical detection of genes and proteins in animal model Cell assays Visualization of tumour and lymph node in human |

Nanoparticle-Based Diagnostics

Nano diagnostics, referred to as the use of nanotechnology in diagnostic applications, has been widely explored for the development of diagnostic test with high sensitivity and prior detection of infection. The nanoscale size and high surface-to-volume ratio of nanoparticles makes this field superior and indispensable in multifield of human action. The unique properties of nanomaterials or nanostructures deliberate the nanodiagnostic platforms and ability of rapid detection by utilizing very small volumes of clinical samples (Jackson et al. 2017). The technology itself is variegated, and several options are available, for instance, nanosuspensions, nanoemulsions, niosomes (nonionic surfactant-based vesicles). Therefore, nanodiagnostic approaches have strong potential to be cost-effective, user-friendly, and robust (Azzazy et al. 2006; Kumar et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2017).

The significant progress has been made in the field of nanotechnology in the last two decade, which showed its wide potential and advantageous applications in the field of biomedicine, biotechnology, human and animal health including nanodiagnostics and nanomedicines. Majority of the nanodiagnostic work has been carried out in the field of cancer diagnostics, but this technique has also been contributed significantly to the diagnosis of various infectious diseases presently (Kumar et al. 2011; Yukuyama et al. 2017). Most of the infectious disease-causing agents such as bacteria (M. tuberculosis), virus (SARS), and fungi may sometimes cause an epidemic outbreak, resulting in higher morbidity and mortality (Mathuria 2009; Nasiruddin et al. 2017; Xu et al. 2018). Thus, initiation of nano-based diagnostic platforms in a clinical setting is gaining importance these days. This is because of the ability of nanodiagnostics to achieve consistency, quick conclusions with simple and movable devices by using various body fluids, such as blood, sputum, or urine samples from patients (Banyal et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2017).

In addition, the highly sensitive nanodiagnostics platforms, with strong potential must be robust, cost effective, and reproducible and could be extremely applicable for the diagnosis of infectious diseases, especially in resource-limited areas in the developing countries.

Gold Nanoparticle (AuNPs)-Based Diagnostics for TB

The gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) pose unique physiochemical (inert and nontoxic) and optical characteristics making them most appropriate nanomaterial for clinical diagnosis, treatments, and other multidisciplinary research. The optical property of AuNPs with antibody or antigen and other biomolecules enable their utility in the diagnosis of various pathogens. Moreover, AuNPs do not disturb the functional activity even after antigen immobilization (Choi and Frangioni 2010; Sonawane and Nimse 2016). The antibody–antigen reaction is enhanced by the surface functionalization of gold nanoparticles, thereby increasing immunoassay signals, which ultimately increase the test sensitivity (Kim et al. 2018). It offers an easy, low-cost assay, which allows simultaneously numerous sample testing. The assay has been found to be very specific and produce reliable results even with tiny amount of mycobacterial DNA. The colorimetric detection of target gene/sequence from test DNA samples via AuNP probes (thiol-linked single-stranded DNA, or ssDNA, modified gold nanoparticles) offer a low-cost alternative method for detection (Chandra et al. 2010; Cordeiro et al. 2016).

The utilization of AuNPs was firstly reported in TB diagnosis by (Baptista et al. 2008), which utilized DNA probes (oligonucleotide derived from the gene sequence of the M. tuberculosis RNA polymerase subunit) coupled with AuNPs for the colorimetric detection of M. tuberculosis. Principally, at wavelength 526 nm, if the complementary DNA is present, the nanoprobe solution remains pink in colour (no DNA probe aggregation), while the solution turns purple (due to nanoprobe aggregation at a high NaCl concentration) in the absence of complementary DNA in the samples. The method is more accurate when compared to other diagnostic methods, that is, InnoLiPA-Rif-TB, which gave 100% concordance (Baptista et al. 2008). The test was proved to be more sensitive than smear microscopy and can be simply visualized for detection. The major advantage of this method is that the chances of contamination is very less (carried out in a single tube reducing contamination), rapid (takes approximately 15 min per sample).

Subsequently, activity of this method was also compared with automated liquid culture system (BACTEC™ MGIT™) and semi-nested PCR, which shows greater sensitivity and specificity of the test in the detection of M. tuberculosis complex (Baptista et al. 2008; Cordeiro et al. 2016). Insertion sequence (IS6110) of M. tuberculosis was also used to increase the sensitivity of this test along with microfluidics technology, which utilized calorimetric detection of AuNPs coupled with IS6110 sequence (Tsai et al. 2017).

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) has attracted much attention for novel metal (Au), which gives a red colour to the AuNPs colloid. The method is based on the real-time monitoring of changes happening in the surface refractive index, formed by association or dissociation of the molecules from the sensor (Khan et al. 2019). The major advantage of the SPR-based test is its optical sensor sensitivity making it capable of detecting even tiny amount of disease-specific analyte from the complex fluid without any specific procedure (Masson 2017; Nguyen et al. 2015; Wang and Fan 2016). Due to these advantages, SPR has emerged as a powerful optical tool, which can provide valuable data in the analysis of biomedical and chemical analyses. The SPR-based CFP-10 antigen detection system was developed in clinical samples by Yang et al. (2014), which showed reputable usefulness in TB diagnostics (Hsieh et al. 2012; Yang et al. 2014).

Zhu et al. (2017) developed AuNPs modified indium tin oxide (ITO) electrode for the direct detection of M. tuberculosis using genomic DNA (gDNA) isolated directly from clinical samples. The method utilized two probes: capture probe and gold nanoprobe coupled with alkaline phosphatase (ALP) enzyme as detection probe. First, ITO probe is activated via capture probe, then activated probe is immersed in the gDNA containing hybridization buffer to form double strand DNA (dsDNA) via hybridization of probe and target nucleotide sequence. Finally, ITO is placed as electrode in the buffer containing detection probe to generate hybridization sandwich. The electric signals are then recorded using voltametry (Zhu et al. 2017).

AuNP-Mediated Dipstick Assay

The colloidal AuNPs were coated with the M. tuberculosis antigen using alkanethiols derivatives and anti-MTB rabbit antibodies. These antigen-coated AuNPs act as a counter or detector reagent in this assay. The serum samples or antibody immobilized on the nitrocellulose (NC) membrane binds to the M. tuberculosis antigen coated on AuNPs. Resultant binding could be visually detected by naked eye, due to the development of the red colour formed by the gold nanoparticles on the nitrocellulose membrane (NC) (Stephen et al. 2015).

Silica Nanoparticles-Based Detection

The application of mesoporous silica nanoparticle (SiO2NPs) has been reported in the various fields, that is, imaging, drug delivery, and biosensors (Sun et al. 2015). The indirect immunofluorescence microscopy has been developed by utilizing nanoparticle coupled with fluorescent dye for the detection of M. tuberculosis. The technology consists of SYBR Green I mediated assay, which stained only bio-conjugated fluorescent silica nanoparticles. The intensity of fluorescent signals is five-fold higher than conventional fluorescence isothiocyanate (FITC)-based detection method. This assay gives promising results within 2 h and therefore is considered to be a promising method for the rapid detection of M. tuberculosis (Qin et al. 2007).

Magnetic Nanoparticles-Based Detection

The magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), nanoscale-sized molecules are present in nature. They harbour favourable features for their usage in the nano-biomedicine, that is, imaging therapy (Akbarzadeh et al. 2012). The surface of MNPs can be easily modified with recognition moieties, that is, antibodies, antibiotics, and carbohydrate, which enable their use for bacterial detection. Super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle (Iron oxide nanoparticles [IONPs], composed of magnetite [Fe3O4] or maghemite [γ-Fe2O3] nanoparticles) is commonly used in the field of drug therapy, cell tracking, drug delivery by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Cristea et al. 2017; Sabale et al. 2017). Using IONPs coupled with IgG has allowed enhanced detection limit (104 CFU/mL) of bacterial cells significantly by using nano-MALDI platforms (Chiu, 2014). Various studies have reported the use of diagnostic magnetic resonance (DMR) along with iron oxide nanoparticles for the detection of M. tuberculosis DNA (Kaittanis et al. 2010; Vallabani and Singh 2018).

Engstrom and his co-workers developed a novel platform using streptavidin tagged magnetic nanobeads labelled with biotin, for the detection of rifampicin mutation in the rpoB gene of M. tuberculosis. The assay comprised of 11 padlock probes (PLPs) targeting 23S ITS region of M. tuberculosis (Engstrom et al. 2013).Of which, one probe was for MTBC detection and another PLP for wild-type and a remaining mixture of nine PLPs are designed for identification of a common mutation in the RRDR-rpoB gene. The detection system is based on the Brownian relaxation principal, and signal is detected via AC susceptometry (Engström et al. 2013).

Efficacy of super-paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles has also been tried for improvement of the sensitivity and specificity of MRI systems in TB detection (Sabale et al. 2017). This method is more effective for the diagnosis of TB at the molecular level and also provides a valuable tool for the analysis of antibody–antigen and parasite–host interactions. The procedure includes activation of SPIO nanoparticles using an anti-MTB surface antibody to form conjugates. Then, conjugate was incubated with mycobacterium followed by MRI imaging, which reveals specific target recognition by reducing signal intensity. This method is more specific for the detection of EPTB (Musculoskeletal TB, Central nervous system TB, abdominal TB) (Skoura et al. 2015).

Quantum Dots-Based Detection System

Quantum dots, also known as semiconductor nanocrystals, possess unique optical and physical properties making them suitable for diagnostics developments (Kairdolf et al. 2013; Smith and Nie 2010). The broad absorption spectra, narrow emission spectra, slow excited-state decay rates, and broad absorption cross-sections are major advantages of quantum dots over other fluorescence-based methods (Rizvi et al. 2010). Also, it can identify multiple targets at the same time, which makes it a much sought after application in the identification of various pathogens in single clinical samples (Rizvi et al. 2010).

The hybrid detection system (Quantum dots and magnetic beads) uses M. tuberculosis-specific molecular probes for TB detection. One probe binds to the 23S rRNA gene of the mycobacterium very precisely and the second probe precisely recognizes IS900 conserved sequence in mycobacterium, which was treated on sulphurous acid chromium quantum dots. Subsequently, sandwich is formed after hybridization with target gene sequences of mycobacterium DNA, isolated from suspected samples of TB patients. Then, quantum dot-magnetic bead conjugates are exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light, which emits red fluorescence (visible to the naked eye).

These conjugate detection systems are also highly versatile molecular probes, which can be easily modified according to their diagnostic utility/purposes. The method can identify the unamplified DNA of M. tuberculosis complex directly from clinical samples (Gazouli et al. 2012). A similar study was reported by Liandris and his co-workers who utilized quantum dots of CdSeO3 coupled with streptavidin and species-specific probes, which detect surface antigen of mycobacterium species. The gDNA of mycobacterial was targeted by a sandwich hybridization, which consisted of two biotinylated probes that would recognize and detect the target DNA specifically. The detection limit is approximately 104cell/mL of the sample (Liandris et al. 2011).

Magnetic Barcode Assays

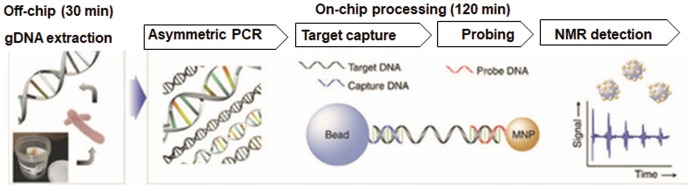

The principal of magnetic barcode (MB) assays is more or less similar to QDs. The assay used specific complementary DNA sequences of M. tuberculosis as probes for TB detection (Liong et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2017).

The major differences are the necessity for DNA extraction and PCR amplification, which are not required in quantum dots assay. After DNA is captured by probes, the resultant conjugate is then marked by complementary magnetic nanoparticle probes, which is then detected by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques (Chen et al. 2017) (Fig. 11.2).

Fig. 11.2.

Framework of the procedure of magnetic barcode (MB) assays

Biosensors-Based Detection System

A biosensor is an analytical system developed for the detection of presences/absences of a specific biological analyte via integrating a bio-recognition element (transduction system, amplifiers, and display unit). The biosensor consists of an analytical device coupled with biological analytes, which report physio-chemical changes in the sensing area (Bhalla et al. 2016; van den Hurk and Evoy 2015; Mehrotra 2016). The biosensor is based on the detection of short nucleotide sequences of M. tuberculosis DNA. TB biosensor can be divided into one of the following categories: mass/piezoelectric, biochemical, electrical, and optical sensors (Table 11.4). These sensing platforms are based on the detecting antibody–antigen interaction, nucleic acid hybridization, and whole mycobacterium bacilli (Lim et al. 2015; Prabhakar et al. 2008; Zhou et al. 2011).

Table 11.4.

Comparison of different biosensors developed for M. tuberculosis detection

| S. No | Technology | Biomarkers | Detection Limit | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | QCM | Whole MTB bacilli | 105 CFU/mL | Kaewphinit et al. (2010) |

| 2. | MSPQC | NH3 & CO2 absorption | 102CFU/mL | Mi et al. (2012) |

| 3. | RBS breath analyser | Ag85 B antigen |

94% sensitivity 79% specificity |

Camilleri (2015) and McNerney et al. (2010) |

| 4. | Interferometric biosensor | 38 kDa antigen | _ | Wang et al. (2013) |

| 5. | SPR | ssDNA | 115 ng/mL (28fM ssDNA) | Hsu et al. (2013) and Prabowo et al. (2016) |

| 6. | SPCE | Ag360 & Ag231 | 1 ng/mL | Wang et al. (2013) |

| 7. | Enzymatic sensor | Mycolic acid antibody | _ | Wang et al. (2013) |

| 8. | Electro-osmosis microchip sensor | Whole M. tuberculosis Bacilli | 100 CFU/mL | Hiraiwa et al. (2015) and Khairulina et al. (2017) |

Abbreviations: QCM quartz crystal microbalance, MSPQC multi-channel series piezoelectric quartz crystal, RBS rapid biosensor system, SPR surface plasmon resonance, SPCE screen-printed carbon electrode, BES bioelectric sensor, CFU colony forming unit

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Presently, approximately 40–50% of TB cases still remain undetected either due to non-availability of diangstic services, poor awareness in the masses or due to scanty or absence of tubercle bacilli in the clinical samples. In such conditions, tests taregetting the whole bacilli in clinical samples are missing many cases due to their poor detection sensitivity. This suggested that detection of bacillary by-products or detection of triggered changes in the host-immune response might be an alternative diagnostic approach for TB detection. Although several attempts have been made in this direction, none of these attempts has displayed clear clinical utility.

Nanotechnology is a fast progressing field, which attracts multi-disciplinary teams to target various healthcare challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases. These technologies have contributed significantly in the diagnosis of various bacterial and viral diseases.Most significantly the nano-based technologies help miniaturizing the diagnostic devices and implants. In the field of tuberculosis, which is one of the major killer disease, the application of nanobiotechnology can help management of TB with added advantage of rapidity, ease of performing test, at cheaper rates, and especially useful for resource-limited countries.

Contributor Information

Shailendra K. Saxena, Email: myedrsaxena@gmail.com

S. M. Paul Khurana, Email: smpaulkhurana@gmail.com.

Sarman Singh, Email: sarman_singh@yahoo.com, Email: sarman.singh@gmail.com.

References

- Aggarwal P, Singal A, Bhattacharya SN, Mishra K. Comparison of the radiometric BACTEC 460 TB culture system and Löwenstein-Jensen medium for the isolation of mycobacteria in cutaneous tuberculosis and their drug susceptibility pattern. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:681–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbarzadeh A, Samiei M, Davaran S. Magnetic nanoparticles: preparation, physical properties, and applications in biomedicine. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2012;7:144. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-7-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi KK, Al-sheikh YA. Role and implications of nanodiagnostics in the changing trends of clinical diagnosis. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2014;21:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arend SM, van Soolingen D. Performance of Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra: a matter of dead or alive. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:8–10. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30695-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzazy HME, Mansour MMH, Kazmierczak SC. Nanodiagnostics: a new frontier for clinical laboratory medicine. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1238–1246. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.066654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badak FZ, Goksel S, Sertoz R, Nafile B, Ermertcan S, Cavusoglu C, Bilgic A. Use of nucleic acid probes for identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis directly from MB/BacT bottles. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1602–1605. doi: 10.1128/JCM.37.5.1602-1605.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyal S, Malik P, Tuli HS, Mukherjee TK. Advances in nanotechnology for diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19:289–297. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32835eff08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista P, Pereira E, Eaton P, Doria G, Miranda A, Gomes I, Quaresma P, Franco R. Gold nanoparticles for the development of clinical diagnosis methods. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:943–950. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1768-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla N, Jolly P, Formisano N, Estrela P. Introduction to biosensors. Essays Biochem. 2016;60:1–8. doi: 10.1042/EBC20150001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bholla M, Kapalata N, Masika E, Chande H, Jugheli L, Sasamalo M, Glass TR, Beck H-P, Reither K. Evaluation of Xpert® MTB/RIF and Ustar EasyNAT™ TB IAD for diagnosis of tuberculous lymphadenitis of children in Tanzania: a prospective descriptive study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:246. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1578-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AC, Bryant JM, Einer-Jensen K, Holdstock J, Houniet DT, Chan JZM, Depledge DP, Nikolayevskyy V, Broda A, Stone MJ, et al. Rapid whole-genome sequencing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates directly from clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:2230–2237. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00486-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bwanga F, Disqué C, Lorenz MG, Allerheiligen V, Worodria W, Luyombya A, Najjingo I, Weizenegger M (2015) Higher blood volumes improve the sensitivity of direct PCR diagnosis of blood stream tuberculosis among HIV-positive patients: an observation study. BMC Infect Dis 15:1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Caliendo AM, Gilbert DN, Ginocchio CC, Hanson KE, May L, Quinn TC, Tenover FC, Alland D, Blaschke AJ, Bonomo RA, et al. Better tests, better care: improved diagnostics for infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2013;57:S139–S170. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri D (2015) Point-of-care disease diagnosis: a breath screen for active tuberculosis at the point-of-care. In: BioOptics World. https://www.bioopticsworld.com/biomedicine/article/16429686/pointofcare-disease-diagnosis-a-breath-screen-for-active-tuberculosis-at-the-pointofcare

- Capek I (2016) Nanosensors based on metal and composite nanoparticles and nanomaterials. In: Parameswaranpillai J, Hameed N, Kurian T, Yu Y (eds) Nanocomposite materials: synthesis, properties and applications. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 1–40

- CDC (2006) Notice to readers: revised definition of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. MMWR 55(43):1176

- Chandra P, Das D, Abdelwahab AA (2010) Gold nanoparticles in molecular diagnostics and therapeutics. Digest J Nanomater Biostruct 5:363–367

- Chatterjee K, Sarkar S, Jagajjanani Rao K, Paria S. Core/shell nanoparticles in biomedical applications. Adv Colloid Interf Sci. 2014;209:8–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi S, Dave PN, Shah NK. Applications of nano-catalyst in new era. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2012;16:307–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jscs.2011.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chegou NN, Black GF, Kidd M, van Helden PD, Walzl G. Host markers in QuantiFERON supernatants differentiate active TB from latent TB infection: preliminary report. BMC Pulm Med. 2009;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-T, Kolhatkar AG, Zenasni O, Xu S, Lee TR (2017) Biosensing using magnetic particle detection techniques. Sensors 17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chihota VN, Grant AD, Fielding K, Ndibongo B, van Zyl A, Muirhead D, Churchyard GJ. Liquid vs. solid culture for tuberculosis: performance and cost in a resource-constrained setting. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis Off J Int Union Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:1024–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu T-C. Recent advances in bacteria identification by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry using nanomaterials as affinity probes. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:7266–7280. doi: 10.3390/ijms15057266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HS, Frangioni JV. Nanoparticles for biomedical imaging: fundamentals of clinical translation. Mol Imaging. 2010;9:291–310. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro M, Ferreira Carlos F, Pedrosa P, Lopez A, Baptista PV (2016) Gold nanoparticles for diagnostics: advances towards points of care. Diagnostics 6:1–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cristea C, Tertis M, Galatus R (2017) Magnetic nanoparticles for antibiotics detection. Nanomaterials 7:1–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Curtis A, Wilkinson C. Nantotechniques and approaches in biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 2001;19:97–101. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(00)01536-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan P. Sputum smear microscopy in tuberculosis: Is it still relevant? Indian J Med Res. 2013;137:442–444. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan P, Panwalkar N, Mirza SB, Chaturvedi A, Ansari K, Varathe R, Chourey M, Kumar P, Pandey M. Line probe assay for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex: an experience from Central India. Indian J Med Res. 2017;145:70–73. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_831_14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman SE, Schumacher SG, Alland D, Nabeta P, Armstrong DT, King B, Hall SL, Chakravorty S, Cirillo DM, Tukvadze N, et al. Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance: a prospective multicentre diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:76–84. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30691-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddabra R, Ait Benhassou H. Rapid molecular assays for detection of tuberculosis. Pneumonia. 2018;10:4. doi: 10.1186/s41479-018-0049-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engström A, de la Torre TZG, Strømme M, Nilsson M, Herthnek D. Detection of rifampicin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by padlock probes and magnetic nanobead-based readout. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatoo MA, Naseem S, Arfat MY, Mahmood Dar A, Qasim K, Zubair S (2014) Physicochemical properties of nanomaterials: implication in associated toxic manifestations. Biomed Res Int:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gazouli M, Lyberopoulou A, Pericleous P, Rizos S, Aravantinos G, Nikiteas N, Anagnou NP, Efstathopoulos EP. Development of a quantum-dot-labelled magnetic immunoassay method for circulating colorectal cancer cell detection. World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2012;18:4419–4426. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i32.4419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goessens WHF, de Man P, Koeleman JGM, Luijendijk A, te Witt R, Endtz HP, van Belkum A. Comparison of the COBAS AMPLICOR MTB and BDProbeTec ET assays for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in respiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2563–2566. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2563-2566.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goletti D, Petrucciani E, Joosten SA, Ottenhoff TH. Tuberculosis biomarkers: from diagnosis to protection. Infect Dis Rep. 2016;8(2):6568. doi: 10.4081/idr.2016.6568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Marín JE, Rigouts L, Villegas Londoño LE, Portaels F. Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis and tuberculosis epidemiology. Bull Pan Am Health Organ. 1995;29:226–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath K, Singh S. Multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous detection and differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium complexes and other Mycobacterial species directly from clinical specimens. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;107:425–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray CM, Katamba A, Narang P, Giraldo J, Zamudio C, Joloba M, Narang R, Paramasivan CN, Hillemann D, Nabeta P et al (2016) Feasibility and operational performance of TB LAMP in decentralized settings — results from a multi-center study. J Clin Microbiol 54(8):1984–1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Havumaki J, Hillemann D, Ismail N, Omar SV, Georghiou SB, Schumacher SG, Boehme C, Denkinger CM. Comparative accuracy of the REBA MTB MDR and Hain MTBDRplus line probe assays for the detection of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a multicenter, non-inferiority study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0173804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraiwa M, Kim J-H, Lee H-B, Inoue S, Becker AL, Weigel KM, Cangelosi GA, Lee K-H, Chung J-H. Amperometric immunosensor for rapid detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Micromech Microeng Struct Device Syst. 2015;25:055013. doi: 10.1088/0960-1317/25/5/055013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh S-C, Chang C-C, Lu C-C, Wei C-F, Lin C-S, Lai H-C, Lin C-W. Rapid identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection by a new array format-based surface plasmon resonance method. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2012;7:180. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-7-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S-H, Lin Y-Y, Lu S-H, Tsai I-F, Lu Y-T, Ho H-T. Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA detection using surface plasmon resonance modulated by telecommunication wavelength. Sensors. 2013;14:458–467. doi: 10.3390/s140100458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson TC, Patani BO, Ekpa DE. Nanotechnology in diagnosis: a review. Adv Nanopart. 2017;06:93. doi: 10.4236/anp.2017.63008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob LJ, Deigner H-P (2018) Chapter 10: Nanoparticles and nanosized structures in diagnostics and therapy. In: Deigner H-P, Kohl M (eds) Precision medicine. Academic Press, pp 229–252

- Jaksuwan R, Patumanond J, Tharavichikul P, Chuchottaworn C, Pokeaw P, Settakorn J. The prediction factors of Pre-XDR and XDR-TB among MDR-TB patients in Northern Thailand. J Tuberc Res. 2018;06:36–48. doi: 10.4236/jtr.2018.61004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaewphinit T, Santiwatanakul S, Promptmas C, Chansiri K. Detection of non-amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis genomic DNA using piezoelectric DNA-based biosensors. Sensors. 2010;10:1846–1858. doi: 10.3390/s100301846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kairdolf BA, Smith AM, Stokes TH, Wang MD, Young AN, Nie S. Semiconductor quantum dots for bioimaging and biodiagnostic applications. Annu Rev Anal Chem Palo Alto Calif. 2013;6:143–162. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anchem-060908-155136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaittanis C, Santra S, Perez JM. Emerging nanotechnology-based strategies for the identification of microbial pathogenesis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:408–423. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerantzas CA, Jacobs WR. Origins of combination therapy for tuberculosis: lessons for future antimicrobial development and application. MBio. 2017;8:e01586–e01516. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01586-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khairulina K, Chung U, Sakai T. New design of hydrogels with tuned electro-osmosis: a potential model system to understand electro-kinetic transport in biological tissues. J Mater Chem B. 2017;5:4526–4534. doi: 10.1039/C7TB00064B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan I, Saeed K, Khan I (2019) Nanoparticles: properties, applications and toxicities. Arab J Chem 12:908–931

- Kim J, Oh SY, Shukla S, Hong SB, Heo NS, Bajpai VK, Chun HS, Jo C-H, Choi BG, Huh YS, et al. Heteroassembled gold nanoparticles with sandwich-immunoassay LSPR chip format for rapid and sensitive detection of hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) Biosens Bioelectron. 2018;107:118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2018.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozel TR, Burnham-Marusich AR. Point-of-care testing for infectious diseases: past, present, and future. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:2313–2320. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00476-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritski A, Fujiwara PI, Vieira MA, Netto AR, Oliveira MM, Huf G, Squire SB. Assessing new strategies for TB diagnosis in low- and middle-income countries. Braz J Infect Dis. 2013;17:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Mazinder Boruah B, Liang X-J (2011) Gold nanoparticles: promising nanomaterials for the diagnosis of cancer and HIV/AIDS. J Nanomater:1–17

- Kumar P, Pandya D, Singh N, Behera D, Aggarwal P, Singh S. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid and sensitive diagnosis of tuberculosis. J Infect. 2014;69:607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagrange PH, Thangaraj SK, Dayal R, Deshpande A, Ganguly NK, Girardi E, Joshi B, Katoch K, Katoch VM, Kumar M, et al. A toolbox for tuberculosis (TB) diagnosis: an Indian multicentric study (2006–2008). Evaluation of QuantiFERON-TB gold in tube for TB diagnosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagrange PH, Thangaraj SK, Dayal R, Deshpande A, Ganguly NK, Girardi E, Joshi B, Katoch K, Katoch VM, Kumar M, et al. A toolbox for tuberculosis (TB) diagnosis: an Indian multi-centric study (2006–2008); evaluation of serological assays based on PGL-Tb1 and ESAT-6/CFP10 antigens for TB diagnosis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laksanasopin T, Guo TW, Nayak S, Sridhara AA, Xie S, Olowookere OO, Cadinu P, Meng F, Chee NH, Kim J, et al. A smartphone dongle for diagnosis of infectious diseases at the point of care. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:273re1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson L, Emenyonu N, Abdurrahman ST, Lawson JO, Uzoewulu GN, Sogaolu OM, Ebisike JN, Parry CM, Yassin MA, Cuevas LE. Comparison of Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug susceptibility using solid and liquid culture in Nigeria. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:215. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, Kang MR, Jung H, Choi SB, Jo K-W, Shim TS. Performance of REBA MTB-XDR to detect extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in an intermediate-burden country. J Infect Chemother Off J Jpn Soc Chemother. 2015;21:346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liandris E, Gazouli M, Andreadou M, Sechi LA, Rosu V, Ikonomopoulos J. Detection of pathogenic mycobacteria based on functionalized quantum dots coupled with immunomagnetic separation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B, Tan Y, Li Z, Tian X, Du C, Li H, Li G, Yao X, Wang Z, Xu Y et al (2018) Highly Sensitive Detection of Isoniazid Heteroresistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DeepMelt Assay. J Clin Microbiol 56:e01239-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lim JW, Ha D, Lee J, Lee SK, Kim T (2015) Review of micro/nanotechnologies for microbial biosensors. Front Bioeng Biotechnol:1–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liong M, Hoang AN, Chung J, Gural N, Ford CB, Min C, Shah RR, Ahmad R, Fernandez-Suarez M, Fortune SM, et al. Magnetic barcode assay for genetic detection of pathogens. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1752. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancebo SM (2009) Synthesis and applications of nanoparticles in biosensing systems. Nanobioelectronics and biosensors Group, Catalan Institute of NanotechnologyBellaterra, Barcelona, Spain (PhD thesis), 1–108. https://www.tdx.cat/bitstream/handle/10803/3300/smm1de3.pdf;sequence=1

- Masson J-F. Surface plasmon resonance clinical biosensors for medical diagnostics. ACS Sens. 2017;2:16–30. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.6b00763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathuria JP (2009) Nanoparticles in tuberculosis diagnosis, treatment and prevention -a hope for future. Dig J Nanomater Biostruct 4(2):309–312

- McNerney R, Wondafrash BA, Amena K, Tesfaye A, McCash EM, Murray NJ. Field test of a novel detection device for Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen in cough. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrotra P. Biosensors and their applications – a review. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2016;6:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhimbira FA, Bholla M, Sasamalo M, Mukurasi W, Hella JJ, Jugheli L, Reither K. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by EasyNAT diagnostic kit in sputum samples from Tanzania. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:1342–1344. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03037-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi X, He F, Xiang M, Lian Y, Yi S. Novel phage amplified multichannel series piezoelectric quartz crystal sensor for rapid and sensitive detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Anal Chem. 2012;84:939–946. doi: 10.1021/ac2020728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirrett S, Hanson KE, Reller LB. Controlled clinical comparison of VersaTREK and BacT/ALERT blood culture systems. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:299–302. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01697-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry NF, Iyer AM, D’souza DTB, Taylor GM, Young DB, Antia NH. Spoligotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from multiple-drug-resistant tuberculosis patients from Bombay, India. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2677–2680. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.7.2677-2680.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasiruddin M, Neyaz MK, Das S (2017) Nanotechnology-based approach in tuberculosis treatment. Tuberc Res Treat 4920209:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nathavitharana RR, Hillemann D, Schumacher SG, Schlueter B, Ismail N, Omar SV, Sikhondze W, Havumaki J, Valli E, Boehme C, et al. Multicenter noninferiority evaluation of hain genoType MTBDRplus version 2 and Nipro NTM+MDRTB line probe assays for detection of rifampin and isoniazid resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:1624–1630. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00251-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HH, Park J, Kang S, Kim M. Surface plasmon resonance: a versatile technique for biosensor applications. Sensors. 2015;15:10481–10510. doi: 10.3390/s150510481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikam C, Kazi M, Nair C, Jaggannath M, M M, R V, Shetty A, Rodrigues C. Evaluation of the Indian TrueNAT micro RT-PCR device with GeneXpert for case detection of pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2014;3:205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmyco.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obasanya J, Lawson L, Edwards T et al (2017) FluoroType MTB system for the detection of pulmonary tuberculosis. ERJ Open Res:1–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Osman M, Simpson JA, Caldwell J, Bosman M, Nicol MP. GeneXpert MTB/RIF version G4 for identification of rifampin-resistant tuberculosis in a programmatic setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:635–637. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02517-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai M, O’Brien R. New diagnostics for latent and active tuberculosis: state of the art and future prospects. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;29:560–568. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1085707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai M, Riley LW, Colford JM. Interferon-gamma assays in the immunodiagnosis of tuberculosis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:761–776. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01206-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai M, Nathavitharana R (2014) Extrapulmonary tuberculosis: new diagnostics and new policies. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 56:71–73 [PubMed]

- Pang Y, Dong H, Tan Y, Deng Y, Cai X, Jing H, Xia H, Li Q, Ou X, Su B, et al. Rapid diagnosis of MDR and XDR tuberculosis with the MeltPro TB assay in China. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25330. doi: 10.1038/srep25330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons LM, Somoskövi Á, Gutierrez C, Lee E, Paramasivan CN, Abimiku A, Spector S, Roscigno G, Nkengasong J. Laboratory diagnosis of tuberculosis in resource-poor countries: challenges and opportunities. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:314–350. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00059-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham TH, Peter J, Mello FCQ, Parraga T, Lan NTN, Nabeta P, Valli E, Caceres T, Dheda K, Dorman SE, et al. Performance of the TB-LAMP diagnostic assay in reference laboratories: Results from a multicentre study. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;68:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar N, Arora K, Arya SK, Solanki PR, Iwamoto M, Singh H, Malhotra BD. Nucleic acid sensor for M. tuberculosis detection based on surface plasmon resonance. Analyst. 2008;133:1587–1592. doi: 10.1039/b808225a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabowo BA, Alom A, Secario MK, Masim FCP, Lai H-C, Hatanaka K, Liu K-C. Graphene-based portable SPR sensor for the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA strain. Procedia Eng. 2016;168:541–545. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2016.11.520. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin D, He X, Wang K, Zhao XJ, Tan W, Chen J. Fluorescent nanoparticle-based indirect immunofluorescence microscopy for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2007;2007:89364. doi: 10.1155/2007/89364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ra SW, Lyu J, Choi C-M, Oh Y-M, Lee S-D, Kim WS, Kim DS, Shim TS. Distinguishing tuberculosis from Mycobacterium avium complex disease using an interferon-gamma release assay. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis Off J Int Union Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:635–640. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reischl U, Lehn N, Wolf H, Naumann L. Clinical evaluation of the automated COBAS AMPLICOR MTB assay for testing respiratory and nonrespiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2853–2860. doi: 10.1128/JCM.36.10.2853-2860.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rienthong S, Boonin C, Chaiyasirinrote B, Satproedprai N, Mahasirimongkol S, Yoshida H, Kondo Y, Namwat C, Rienthong D. Evaluation of a novel line-probe assay for genotyping-based diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Thailand. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis Off J Int Union Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19:817–822. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi SB, Ghaderi S, Keshtgar M, Seifalian AM (2010) Semiconductor quantum dots as fluorescent probes for in vitro and in vivo bio-molecular and cellular imaging. Nano Rev 1:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rocchetti TT, Silbert S, Gostnell A, Kubasek C, Widen R. Validation of a multiplex real-rime PCR assay for detection of Mycobacterium spp., Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, and Mycobacterium avium complex directly from clinical samples by use of the BD Max open system. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:1644–1647. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00241-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues C, Shenai S, Sadani M, Sukhadia N, Jani M, Ajbani K, Sodha A, Mehta A. Evaluation of the bactec MGIT 960 TB system for recovery and identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in a high volume tertiary care centre. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27:217. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.53203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rufai SB, Kumar P, Singh A, Prajapati S, Balooni V, Singh S. Comparison of Xpert MTB/RIF with line probe assay for detection of rifampin-monoresistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:1846–1852. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03005-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rufai SB, Singh S, Singh A, Kumar P, Singh J, Vishal A. Performance of Xpert MTB/RIF on ascitic fluid samples for detection of abdominal tuberculosis. J Lab Physician. 2017;9:47–52. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.187927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabale S, Kandesar P, Jadhav V, Komorek R, Motkuri RK, Yu X-Y. Recent developments in the synthesis, properties, and biomedical applications of core/shell superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles with gold. Biomater Sci. 2017;5:2212–2225. doi: 10.1039/C7BM00723J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P, Bhargava M (2013) Applications and characteristics of nanomaterials in industrial environment. Int J Civ, Struct, Environ Infrastructure Eng Res Dev (IJCSEIERD) 3:63–72. ISSN 2249-6866

- Sharma S, Zapatero-Rodríguez J, Estrela P, O’Kennedy R. Point-of-care diagnostics in low resource settings: present status and future role of microfluidics. Biosensors. 2015;5:577–601. doi: 10.3390/bios5030577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenai S, Armstrong DT, Valli E, Dolinger DL, Nakiyingi L, Dietze R, Dalcolmo MP, Nicol MP, Zemanay W, Manabe Y, et al. Analytical and clinical evaluation of the epistem genedrive assay for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:1051–1057. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02847-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Gopinath K, Sharma P, Bisht D, Sharma P, Singh N, Singh S. Comparative proteomic analysis of sequential isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from a patient pulmonary tuberculosis turning from drug sensitive to multidrug resistant. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:27–45. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.154492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Gupta AK, Gopinath K, Sharma P, Singh S. Evaluation of 5 Novel protein biomarkers for the rapid diagnosis of pulmonary and extra-pulmonary tuberculosis: preliminary results. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44121. doi: 10.1038/srep44121(2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoura E, Zumla A, Bomanji J. Imaging in tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;32:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AM, Nie S (2010) Semiconductor nanocrystals: structure, properties, and band gap engineering. Acc Chem Res 43:190–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sonawane MD, Nimse SB (2016) Surface modification chemistries of materials used in diagnostic platforms with biomolecules. J Chem:1–19

- Stephen BJ, Singh SV, Datta M, Jain N, Jayaraman S, Chaubey KK, Gupta S, Singh M, Aseri GK, Khare N, et al. Nanotechnological approaches for the detection of mycobacteria with special references to Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) Asian J Anim Vet Adv. 2015;10:518–526. doi: 10.3923/ajava.2015.518.526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun R, Wang W, Wen Y, Zhang X. Recent advance on mesoporous silica nanoparticles-based controlled release system: intelligent switches open up new horizon. Nano. 2015;5:2019–2053. doi: 10.3390/nano5042019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai T-T, Huang C-Y, Chen C-A, Shen S-W, Wang M-C, Cheng C-M, Chen C-F. Diagnosis of tuberculosis using colorimetric gold nanoparticles on a paper-based analytical device. ACS Sens. 2017;2:1345–1354. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.7b00450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuberculosis Division IUTALD. Tuberculosis bacteriology–priorities and indications in high prevalence countries: position of the technical staff of the Tuberculosis Division of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis Off J Int Union Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:355–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallabani NVS, Singh S. Recent advances and future prospects of iron oxide nanoparticles in biomedicine and diagnostics. 3 Biotech. 2018;8:279. doi: 10.1007/s13205-018-1286-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Hurk R, Evoy S. A review of membrane-based biosensors for pathogen detection. Sensors. 2015;15:14045–14078. doi: 10.3390/s150614045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D-S, Fan S-K (2016) Microfluidic surface plasmon resonance sensors: from principles to point-of-care applications. Sensors (Basel) 16(8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang EC, Wang AZ. Nanoparticles and their applications in cell and molecular biology. Integr Biol Quant Biosci Nano Macro. 2014;6:9–26. doi: 10.1039/c3ib40165k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Inci F, De Libero G, Singhal A, Demirci U. Point-of-care assays for tuberculosis: role of nanotechnology/microfluidics. Biotechnol Adv. 2013;31:438–449. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SX, Tay L. Evaluation of three nucleic acid amplification methods for direct detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in respiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1932–1934. doi: 10.1128/JCM.37.6.1932-1934.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Yu L, Kong X, Sun L (2017) Application of nanodiagnostics in point-of-care tests for infectious diseases. Int J Nanomedicine 12:4789–4803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Watanabe Pinhata JM, Cergole-Novella MC, Moreira dos Santos Carmo A, Ruivo Ferro e Silva R, Ferrazoli L, Tavares Sacchi C, Siqueira de Oliveira R. Rapid detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex by real-time PCR in sputum samples and its use in the routine diagnosis in a reference laboratory. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64:1040–1045. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2017) WHO | Global tuberculosis report 2017

- Xu K, Liang ZC, Ding X, Hu H, Liu S, Nurmik M, Bi S, Hu F, Ji Z, Ren J, et al. Nanomaterials in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis infections. Adv Healthc Mater. 2018;7:1700509. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201700509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav R, Sharma N, Khaneja R, Agarwal P, Kanga A, Behera D, Sethi S. Evaluation of the TB-LAMP assay for the rapid diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in Northern India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis Off J Int Union Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21:1150–1153. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.17.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Qin L, Wang Y, Zhang B, Liu Z, Ma H, Lu J, Huang X, Shi D, Hu Z (2014) Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on H R binding peptides using surface functionalized magnetic microspheres coupled with quantum dots – a nano detection method for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J Nanomedicine 17:77–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yukuyama MN, Kato ETM, Lobenberg R, Bou-Chacra NA. Challenges and future prospects of nanoemulsion as a drug delivery system. Curr Pharm Des. 2017;23:495–508. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666161027111957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M-J, Ren W-Z, Sun X-J, Liu Y, Liu K-W, Ji Z-H, Gao W, Yuan B. GeneChip analysis of resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis with previously treated tuberculosis in Changchun. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:234. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3131-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Hu S, Li G, Li H, Liu X, Niu J, Wang F, Wen H, Xu Y, Li Q. Evaluation of the MeltPro TB/STR assay for rapid detection of streptomycin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberc Edinb Scotl. 2015;95:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, He X, He D, Wang K, Qin D (2011) Biosensing technologies for Mycobacterium tuberculosis detection: status and new developments. Clin Dev Immunol 193963:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhu L, Liu Q, Martinez L, Shi J, Chen C, Shao Y, Zhong C, Song H, Li G, Ding X, et al. Diagnostic value of GeneChip for detection of resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in patients with differing treatment histories. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:131–135. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02283-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Song L, Liu W, Yan X, Xiao J, Chen C. Gold nanoparticles-modified indium tin oxide microelectrode for in-channel amperometric detection in dual-channel microchip capillary electrophoresis. Anal Methods. 2017;29:4319–4326. doi: 10.1039/C7AY01008G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]