Abstract

Recently discovered DNAJB1-PRKACA oncogenic fusions have been considered diagnostic for fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. In this study, we describe six pancreatobiliary neoplasms with PRKACA fusions, five of which harbor the DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion.

All neoplasms were subjected to a hybridization capture-based next-generation sequencing assay (MSK-IMPACT), which enables the identification of sequence mutations, copy number alterations, and selected structural rearrangements involving ≥ 410 genes (n=6) and/or to a custom targeted, RNA-based panel (MSK-Fusion) that utilizes Archer Anchored Multiplex PCR technology and next-generation sequencing to detect gene fusions in 62 genes (n=2). Selected neoplasms also underwent FISH analysis, albumin mRNA in-situ hybridization and arginase-1 immunohistochemical labeling (n=3).

Five neoplasms were pancreatic, and one arose in the intrahepatic bile ducts. All revealed at least focal oncocytic morphology: three cases were diagnosed as intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasms, and three as intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms with mixed oncocytic and pancreatobiliary or gastric features. Four cases had an invasive carcinoma component composed of oncocytic cells. Five cases revealed DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions and one revealed an ATP1B1-PRKACA fusion. None of the cases tested were positive for albumin or arginase-1. Our data prove that DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion is neither exclusive nor diagnostic for fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, and caution should be exercised in diagnosing liver tumors with DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions as fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, particularly if a pancreatic lesion is present. Moreover, considering DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions lead to up-regulated protein kinase activity and that this up-regulated protein kinase activity has a significant role in tumorigenesis of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, protein kinase inhibition could have therapeutic potential in the treatment of these pancreatobiliary neoplasms as well, once a suitable drug is developed.

Keywords: DNAJB1, PRKACA, fusion, oncocytic, pancreatic, biliary, fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma

INTRODUCTION:

The introduction of routine broad-spectrum genomic analysis of solid neoplasms has generated a wealth of data about alterations at the DNA and RNA level, some of which appear to have diagnostic specificity for distinctive neoplasms, and others may confer sensitivity to targeted therapies. Recently, a novel DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion was discovered in the fibrolamellar variant of hepatocellular carcinoma [1]. Both genes are located on the short arm of chromosome 19, and the in-frame fusion occurs due to a 400 kb deletion. PRKACA encodes the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A (PKA). In presence of cyclic AMP, the catalytic subunit of PKA is involved in regulation of downstream effectors via phosphorylation. The DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion results in the formation of a chimeric protein, which has up-regulated protein kinase activity [2]. It is believed that this up-regulated protein kinase activity has a significant role in tumorigenesis of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma [3]. The published literature documents the presence of this fusion in >95 % of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinomas, but it is reportedly absent in other neoplasms of the liver or other anatomical sites [4]. Thus, identification of this fusion has been regarded as diagnostic for fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma.

However, our comprehensive molecular testing of pancreatobiliary neoplasms demonstrated the recurrent presence of DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions in a subset with oncocytic features. Here, we discuss the clinicopathologic and molecular features of these pancreatobiliary neoplasms.

METHODS:

The study was approved by the institutional review board.

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center institutional database of 34830 solid neoplasms that underwent clinical sequencing testing with MSK-IMPACT (n=33,634) or MSK-Fusion Panel (n=1196) assays as well as the authors’ prior research cohorts of 23 pancreatic and biliary intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasms [5; 6; 7; 8] were searched for cases with fusions involving DNAJB1 or PRKACA, the specific DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion in particular. MSK-IMPACT is a hybridization capture-based next generation sequencing assay that assesses the coding regions as well as selected promoter and intronic regions of 410 genes (n=23849) or 468 genes (n=9785), depending upon the version of the test employed, for mutations, amplifications, deletions, selected structural rearrangements (including DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions), and microsatellite status against a patient’s matched normal [9; 10; 11]. Only cases tested using the newer (01/30/2015 or later) versions of the MSK-IMPACT panel (MSK-IMPACT 410 or 468) were included as the previous versions did not include probes that specifically target DNAJB1 intronic rearrangements. The MSK-Fusion assay is a custom targeted, RNA-based panel that utilizes Archer Anchored Multiplex PCR technology and next-generation sequencing to detect gene fusions in 62 genes (including DNAJB1, PRKACA, and ATP1B1) known to be involved in chromosomal rearrangements [12; 13; 14]. These custom assays have been validated and approved for clinical use at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center by the New York State Department of Health Clinical Laboratory Evaluation Program.

Separately, the Cancer Genome Atlas database [15; 16] was also searched for additional cases with fusions involving these genes.

Histologic sections of the cases with DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions in the institutional database were evaluated to characterize the diagnostic features of the neoplasms [slides of the primary neoplasm and metastases (if applicable) were reviewed and tissue from the primary was tested]. Available medical records, including pathology reports, were reviewed to obtain clinical data and outcome.

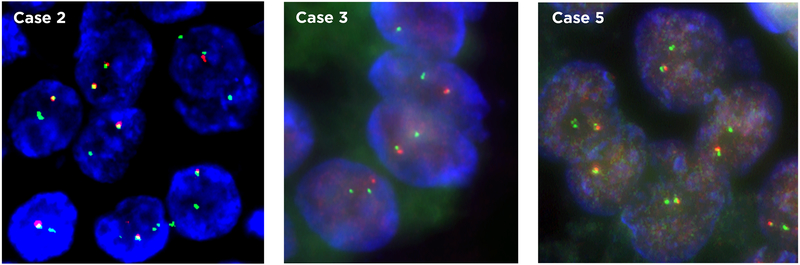

The cases with DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions, for which additional material was available (n=3), underwent FISH analysis following the standard protocols. Briefly, 4 μm-thick tissue sections were de-paraffinized, followed by dehydration in 100% ethanol. Tissues were treated with pepsin for 10-25 minutes, followed by fixation in 10% formalin, and dehydration in a series of 70%, 85% and 100% ethanol. The PRKACA break-apart probe set (Empire Genomics, Buffalo, NY) consists of two BAC probes for the 5’PRKACA region (383kb, labeled in spectrum red) and 3’PRKACA region (542kb, labeled in spectrum green), respectively. After applying the FISH probes to the tissue, both tissue and probes were co-denatured, hybridization was set at 37° C overnight, followed by post-hybridization washing, and counterstained with DAPI. Signal analysis was performed in combination with morphology correlation, and at least 100 interphase cells within the marked tumor area were evaluated and imaged using a Zeiss fluorescence microscope coupled with Metasystems ISIS software (Newton, MA).

The cases with DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions, for which additional material was available (n=3), as well as cases of intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasms of the pancreas and bile ducts from prior research cohorts (n=23) [6; 7; 8] were also labeled with arginase-1 immunohistochemical stain (Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA), using the standard avidin-biotin peroxidase method, and albumin mRNA in-situ hybridization, using the automated ViewRNA platform (Affymetrix) as previously described [17], to assess diagnostic value of arginase and albumin staining in these neoplasms.

RESULTS:

Among the 33,634 cases in the MSK-IMPACT clinical sequencing cohort (2434 of these cases also had MSK-Fusion), we found two non-fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma samples that harbored DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions. Both neoplasms were pancreatobiliary primaries with oncocytic morphology, and none had typical histologic features of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Additionally, among the 1196 cases in the MSK-Fusion clinical sequencing cohort (none of these cases had MSK-IMPACT), another pancreatobiliary neoplasm with similar oncocytic morphology was found to harbor an ATP1B1-PRKACA fusion. The prior research cohorts of 23 pancreatic and biliary intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasms [5; 6; 7; 8] revealed three more cases with DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions.

Of note, pancreatobiliary neoplasms in our MSK-IMPACT clinical sequencing cohort included ampullary carcinomas (n=84), pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (n=1584), adenosquamous carcinomas of the pancreas (n=36), undifferentiated carcinomas of the pancreas (n=18), intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas (n=14), mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas (n=3), pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (n=200), acinar cell carcinomas (n=34), pancreatoblastomas (n=3), solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (n=8), gallbladder carcinomas (n=138), cholangiocarcinomas, NOS (n=56), extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (n=102), perihilar cholangiocarcinomas (n=13), and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (n=334). Our MSK-Fusion clinical sequencing cohort included pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (n=13), adenosquamous carcinomas of the pancreas (n=2), pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (n=1), acinar cell carcinomas (n=2), pancreatoblastoma (n=1), gallbladder carcinomas (n=2), cholangiocarcinomas, NOS (n=6), and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (n=4). The prior research cohorts included solely intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasms of the pancreas (n=13) and bile ducts (n=10).

Of the 10,967 samples in the Cancer Genome Atlas database, none of the non-fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma samples harbored DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions. However, there were four samples that harbored PRKACA rearrangements with other partner genes and the primary sites of those neoplasms were breast (two invasive ductal carcinomas; one with a GATA2A-PRKACA fusion, another with a TPGS1-PRKACA fusion), lung (an invasive squamous cell carcinoma with an ASF1B-PRKACA fusion), and ovary (a high grade papillary serous carcinoma with an ASF1B-PRKACA fusion) [16].

Clinical Features:

The clinicopathologic features of the six PRKACA fusion positive oncocytic pancreatobiliary neoplasms are summarized in Table 1. The cohort included five males and one female, and the mean age was 55 years at first presentation (range, 36-76 years). Five cases were pancreatic and one case arose in an intrahepatic bile duct. Follow-up data were available for five patients (interval 9 months - 20 years). One patient died of disease, 4 years after initial diagnosis. One patient had a local recurrence as well as immunohistochemically confirmed distant metastases after 20 years. At the time of last follow-up, the remaining three patients were alive with no evidence of disease 9 months, 6 years, and 10 years after initial diagnosis.

Table 1:

Clinicopathologic Features of the Pancreatobiliary Neoplasms with PRKACA Fusions

| Case | Age/Sex | Initial Presentation | Pathology Diagnosis | Clinical Follow-up | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraductal Component | Invasive Component | Metastasis | ||||

| 1 | 63/M | 7 cm mass in head of the pancreas | IOPN | Invasive adenocarcinoma with mucinous and oncocytic features | Not applicable | No follow up data available |

| 2 | 47/M | 10 cm cystic mass in caudate lobe of liver | IOPN of the bile ducts | Invasive adenocarcinoma with oncocytic features | Not applicable | Recurrence after 4 years; now deceased |

| 3 | 36/M | 4.5 cm cystic mass in head of the pancreas | IOPN | Not applicable | Not applicable | No evidence of disease for 10 years |

| 4 | 58/F | Complex cystic mass in head of the pancreas | IPMN, mixed oncocytic and pancreatobiliary features | Minute focus of invasion with mucinous and oncocytic features | Not applicable | No adjuvant therapy given. No evidence of disease for 9 months |

| 5 | 52/M | 2.8 cm cystic mass in head of the pancreas | IPMN, mixed oncocytic and gastric features | Not applicable | Not applicable | No evidence of disease for 6 years |

| 6 | 76/M | Distal pancreatic mass | IPMN, mixed oncocytic and pancreatobiliary features | Invasive adenocarcinoma | Metastatic adenocarcinoma with oncocytic features, involving liver | Recurrence and liver metastases after 20 years, disease progression despite chemotherapy |

IOPN: Intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasm; IPMN: Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm

Histologic Features:

There was significant morphologic overlap among these six neoplasms. All six were either an intraductal neoplasm (n=2) or an invasive carcinoma arising in association with an intraductal neoplasm (n=4).

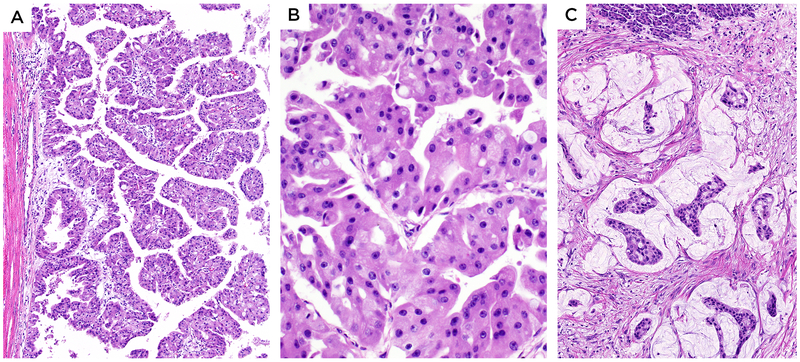

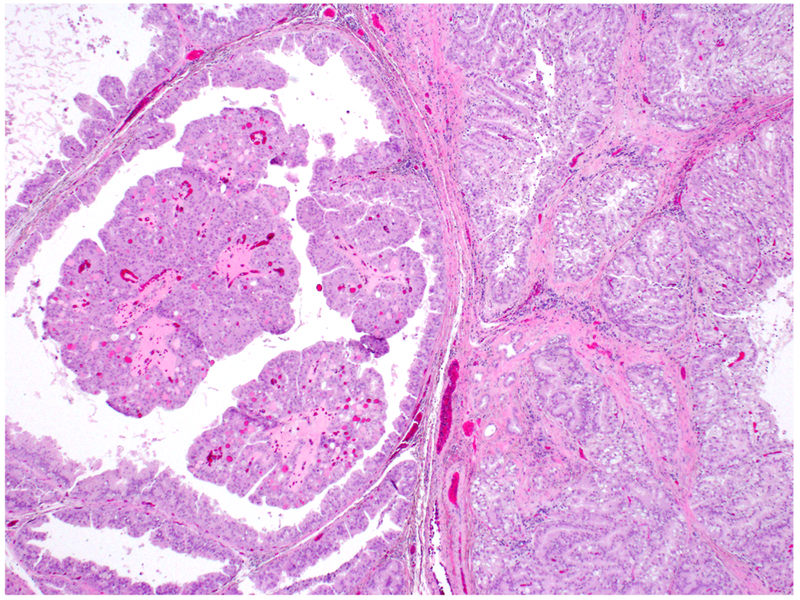

Three cases were diagnosed as intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasm (two in the pancreas, one in the intrahepatic bile ducts). These cases exhibited arborizing papillae lined by multiple layers of neoplastic cells with abundant eosinophilic, granular cytoplasm and large, and fairly uniform nuclei containing single, prominent nucleoli (Figure 1). Intraepithelial lumina and interspersed goblet cells were also present [5]. Three additional pancreatic cases were diagnosed as intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms with mixed oncocytic and pancreatobiliary features (n=2) or mixed oncocytic and gastric features (n=1), as they also demonstrated foci of pancreatobiliary or gastric differentiation (Figure 2).

Figure 1:

A-B. Intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasms exhibited papillary architecture with distinct oncocytic cytology and intracytoplasmic lumens. C. If present, invasive component revealed stromal mucin accumulation in which the neoplastic cells were suspended (Case 1 is depicted here).

Figure 2:

Three pancreatic neoplasms demonstrated mixed features, Case 5 with mixed oncocytic and gastric features is shown here.

Four cases had an associated invasive carcinoma component (three in the pancreas, one in the intrahepatic bile ducts). The invasive component was characterized either by small tubular units composed of oncocytic cells infiltrating loose, myxoid stroma or by stromal mucin accumulation in which oncocytic neoplastic cells were suspended, resembling the pattern of colloid carcinoma (Figure 1). In one case, prominent cytoplasmic eosinophilic globules were noted.

Immunohistochemical Features:

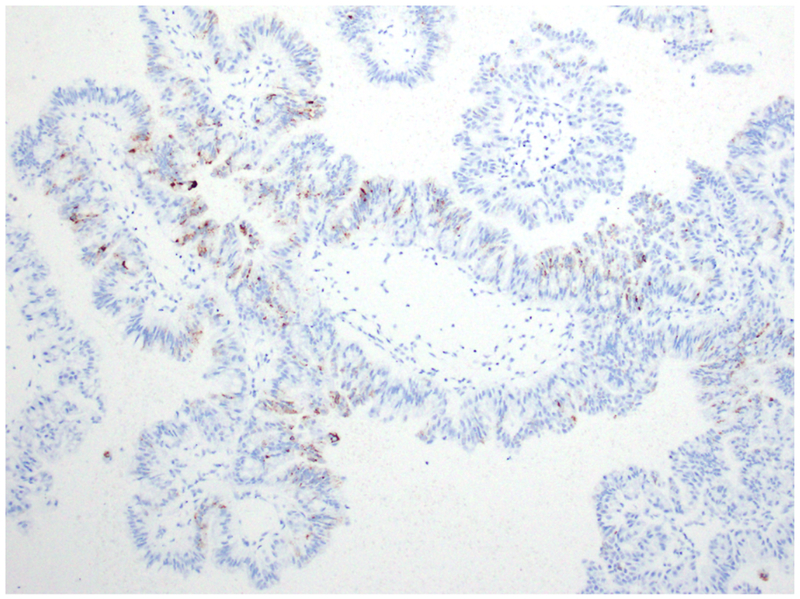

None of the three cases with DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions tested (Cases #2, #3 and #5) were positive for albumin mRNA by in-situ hybridization or arginase-1 by immunohistochemistry.

Among the 23 cases from the prior research cohorts, although two pancreatic (15%) and one biliary (10%) intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasms were positive (all patchy) for albumin mRNA by in-situ hybridization (Figure 3), none demonstrated arginase-1 immunolabeling.

Figure 3:

Albumin mRNA by in-situ hybridization was positive in two pancreatic intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasms (none of these cases had DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions).

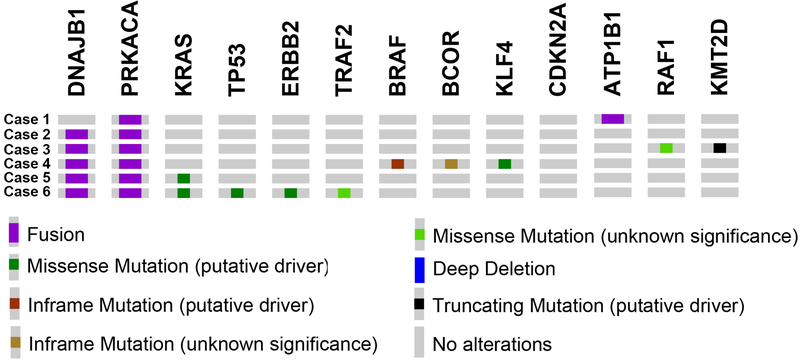

Molecular Features:

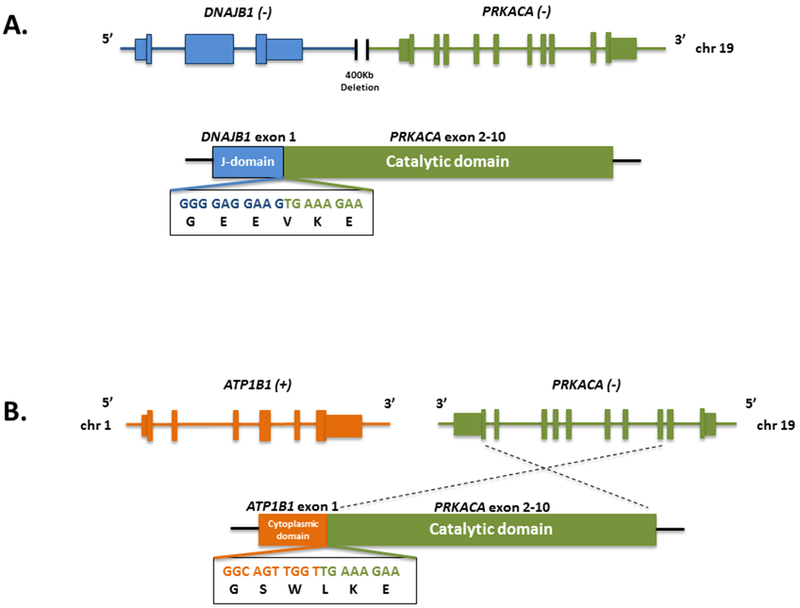

Of the six cases harboring PRKACA fusions, five revealed DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions and one (Case #1) revealed an ATP1B1-PRKACA fusion. All five cases with DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions harbored fusions involving exon 2 or intron 1 of DNAJB1 with intron 1 or the promoter of PRKACA. Case #1 harbored a fusion involving exon 1 of ATP1B1 with exon 2 of PRKACA (Figures 4 and 5, Table 2).

Figure 4:

OncoPrint diagram of types of genetic alterations seen in our cases.

Figure 5:

Schematic representations of PRKACA fusions detected by the MSK-Fusion targeted RNASeq assay. A. DNAJB1-PRKACA in-frame fusion resulting from a 400 Kb deletion on chromosome 19 and joining exon1 of DNAJB1 (NM_006145) to exons 2-10 of PRKACA (NM_002730). B. ATP1B1-PRKACA fusion derived from a translocation between chromosome 1 and chromosome 19. This in-frame fusion event involves exon 1 of ATP1B1 (NM_001677) and exons 2-10 of PRKACA (NM_002730). The chimeric transcript sequence and its corresponding protein sequence are indicated under the fusion breakpoint region. +/− indicate the direction of transcription of each gene.

Table 2:

Molecular Features of PRKACA Rearranged Pancreatobiliary Neoplasms

| Case | Diagnosis | Test | Partner Gene (5’) | Kinase Gene (3’) | Predicted Fusion | Other Genomic Mutations / Alterations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IOPN with invasion | MSK-Fusion | ATP1B1 Exon 1 (NM_001677) | PRKACA Exon 2 (NM_002730) | Protein fusion: in frame (ATP1B1-PRKACA) | BCL10 D139V, GREM1 S137del, MYD88 S129C, MDM2 amplification |

| 2 | Biliary IOPN with invasion | MSK-IMPACT & FISH | DNAJB1 Intron 1 (NM_006145) | PRKACA Intron 1 (NM_002730) | Protein fusion: in frame (DNAJB1-PRKACA) | KIT P34L, NOTCH4 R373W, BLM D239N, LATS2 V367I |

| 3 | IOPN | MSK-IMPACT & FISH | DNAJB1 Intron 1 (NM_006145) | PRKACA Promoter (NM_002730) | Transcript fusion (DNAJB1-PRKACA) | RAF1 A150S, KMT2D G5189R, KMT2D W2038X |

| 4 | IPMN, mixed oncocytic and pancreatobiliary features, with invasion | MSK-IMPACT | DNAJB1 Intron 1 (NM_006145) | PRKACA Intron 1 (NM_002730) | Protein fusion: in frame (DNAJB1-PRKACA) | BRAF V600_K601delinsE, BCOR E382Qfs*53, KLF4 K409Q, loss of chromosome arm 9p21-24 |

| 5 | IPMN, mixed oncocytic and gastric features | MSK-IMPACT & FISH | DNAJB1 Exon 2 (NM_006145) | PRKACA Intron 1 (NM_207518) | Protein fusion: mid-exon (DNAJB1-PRKACA) | KRAS G12D |

| 6 | IPMN with mixed oncocytic and pancreatobiliary features, with invasion | MSK-IMPACT | DNAJB1 Intron 1 (NM_006145) | PRKACA Intron 1 (NM_002730) | Protein fusion: in frame (DNAJB1-PRKACA) | KRAS G12R, TP53, R110C, ERBB2, R678W, TRAF2 I376V |

IOPN: Intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasm; IPMN: Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm

In all three cases tested (Cases #2, #3 and #5), FISH analysis revealed that more than 90% of the tumor cells had a signal pattern of one single signal (green) for the 3’PRKACA region and one to two normal fusion signals (Figure 6). These results are consistent with a complete deletion of the 5’ PRKACA region between PRKACA and DNAJB1, which results in the DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion, supporting the results of MSK-IMPACT and MSK-Fusion assays.

Figure 6:

FISH analysis using PRKACA break-apart probes reveals a complete loss of the 5’PRKACA signal (labeled in red) in most cells, indicative of an interstitial deletion of the 5’ upstream region between the PRKACA and DNAJB1 at 19p13.12.

Of note, all cases revealed other genomic mutations and/or alterations. In four cases, mutations in key driver genes involved in the MAPK pathway (KRAS, BRAF and RAF1) were identified. Three of these were pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms with either mixed oncocytic and pancreatobiliary (n=2) or mixed oncocytic and gastric (n=1) features that harbored KRAS G12R, KRAS G12D or BRAF V600_K601delinsE mutations. The last one was a pancreatic intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasm that had a RAF1 A150S mutation. Additionally, the case with distant metastasis had alterations in key cell cycle regulator genes, such as TP53 (Table 2 and Figure 4).

DISCUSSION:

In this study, we present six pancreatobiliary neoplasms with fusions involving PRKACA. All neoplasms at least focally demonstrated oncocytic morphology in their intraductal and/or invasive components. The morphologic overlap of these neoplasms with each other as well as with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, which are also defined by fusions involving the PRKACA gene, suggests that the oncocytic morphology may be associated with fusions involving this gene.

In 2014, Honeyman et al. reported the DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion transcript in fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma [1]. This finding has been validated by subsequent studies and touted as a diagnostic biomarker for this entity [18]. In the seminal study, the authors documented a ~400kb deletion on chromosome 19 resulting in a fusion that either starts in intron 1 or exon 2 of DNAJB1 and ends in intron 1 of PRKACA. Since the description of the fusion, several studies have been undertaken to determine the role of this fusion transcript in the development of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. The fusion codes for an active and oncogenic form of protein kinase A (PKA) enzyme. The fusion protein is phosphorylated at a site in the Cα catalytic subunit of the PKA (PKA-Cα), which is often associated with kinase activity even in the absence of activators of adenylyl cyclase, suggesting that the fusion protein is constitutively more active than wild-type PKA-Cα, but can be further induced with signals that normally activate PKA in cells [19]. The reason for upregulated activity of the fusion transcript as compared to wild-type PKA may be related to the replacement of the PRKACA promoter by the DNAJB1 promoter, leading to a higher basal transcription rate. Engelholm et al., using CRISPR/Cas9 techniques, showed generation of the DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion gene in wild-type mice to be sufficient to initiate formation of tumors that have many features of human fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, but carcinogenesis may be more complex in humans [20]. In fact, in human fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinomas, recurrent mutations that hyperactivate the Wnt pathway have been reported, together with the DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion. Furthermore, genetic alteration of this pathway -but not several other oncogenes or tumor suppressors- synergized with DNAJB1-PRKACA driven carcinogenesis in mouse models [21]. Sanford et al. also suggested that sole activation of PRKACA is not sufficient for human carcinogenesis and perhaps the conformational properties of this chimera may play a role [22]. More recently, microRNA-375 dysregulation was also identified in cases of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, but how the DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion transcript plays a role in the suppression of microRNA-75 expression and whether microRNA-75 has important targets in this tumor remain to be studied [23]. Of note, while the DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion is highly recurrent in fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, rare cases of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma without the fusion have been described [2, 24]. In those cases, alternative mechanisms of upregulation of PKA, such as loss of PRKACA1 in Carney complex, or amplification of PRKACA, have been demonstrated [4, 24, 25].

Through analysis of a large series of pancreatobiliary neoplasms, we identified six neoplasms, five with DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions and one with an ATP1B1-PRKACA fusion. The structural variants of DNAJB1-PRKACA observed in our study are similar to those described by Honeyman et al in their seminal study [1], indicating that the functional implications of the fusions are also most likely similar [1]. However, additional possible driver mutations, including key drivers of the MAPK pathway and key cell cycle regulatory genes, were also present in our cases (Table 2). Of note, ATP1B1-PRKACA fusions have been reported in cholangiocarcinoma [26, 27]. ATP1B1 is also a known gene partner in NRG1 rearrangements, which are oncogenic drivers that are enriched in invasive mucinous adenocarcinomas of the lung [28].

In addition to the shared genomic event, these pancreatobiliary neoplasms shared some specific histologic features as well. All six cases had an intraductal neoplasm with at least mixed, if not pure, oncocytic morphology. Of note, the pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms with mixed (oncocytic and pancreatobiliary or gastric) features harbored MAPK pathway mutations, more typical of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms [6]. All four cases with an invasive component also revealed similar oncocytic features in the invasive carcinoma. The morphologic overlap between fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinomas and the pancreatobiliary neoplasms in this series is also interesting. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinomas are composed of cords of large and polygonal neoplastic cells in background of dense collagen bundles frequently arranged in parallel lamellae. The neoplastic cells have abundant granular and eosinophilic cytoplasm with frequent hyaline globules and typical nuclear features include open chromatin and prominent “cherry red” macronucleoli [4]. While the pancreatobiliary neoplasms in this series are architecturally different from fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, they are cytologically similar, as they also exhibit abundant granular and eosinophilic cytoplasm, large vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli [29].

Although number of the cases is too limited to draw any definitive conclusions, the morphologic similarity among these tumors that have the same fusion resulting in activation of PKA is intriguing. Studies have shown that oncocytic neoplasms including fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma and intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasm are rich in mitochondria [30]. It is also known that PKA acts on several substrates located in the mitochondria in various organs [31]. The constitutional activation of the PKA pathway by the chimeric fusion protein probably causes mitochondrial hyperplasia within the cells, which results in the oncocytic appearance. Therefore, it is possible that fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma and the pancreatobiliary neoplasms described in this series may share common progenitors, especially considering they overlap not only morphologically but also immunophenotypically. While conventional hepatocellular carcinomas are usually CK7 negative, fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinomas label with CK7 [32; 33] and oncocytic pancreatobiliary neoplasms express HepPar-1 [7; 34] and, focally, albumin mRNA. Moreover, transcriptomic analysis of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinomas has shown enrichment of certain transcription factor gene sets associated with pancreatic cancer, namely ERBB2, E2F1, E2F3, CDKN2A, CDK6, SMAD2, TGFBR1, and TGFB2 [3]. What this likely means is that altered PKA function, leading to alteration in the activity of these oncogenic proteins, may at least play a part in, if not driving, oncogenesis. Interestingly, one of our cases shared genomic mutations/alterations in some of the above-mentioned genes (ERBB2 in Case #6).

Our data raise awareness that DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions are not unique to fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma and may also be seen in oncocytic pancreatobiliary neoplasms. Although diagnostic confusion is unlikely based upon resected specimens, caution should be exercised in the context of biopsy and cytology specimen interpretation. Because the differential diagnosis of an oncocytic neoplasm in the liver, perihepatic soft tissue or regional lymph nodes, with CK7, HepPar-1, and albumin mRNA expression and a DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion includes fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma as well as intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasms (and associated invasive carcinomas) of the bile ducts and the pancreas [32; 35]. Therefore, more specific hepatocellular differentiation markers, such as arginase-1 immunohistochemical staining, as well as radiographic findings demonstrating the lack of a pancreas mass may be needed to establish a definitive diagnosis.

Furthermore, this chimera is potentially targetable, and new therapeutics are on the horizon, including kinase inhibitors or other modalities altering the PKA pathway [36]. Considering clinical trials using non-specific tyrosine/aurora kinase inhibitors for advanced stage fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma are already enrolling patients [37], it is only a matter of time before specific targeted therapy becomes available for fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Identifying PRKACA fusions will then become therapeutically important not only for fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma but also in other neoplasms harboring this fusion [38].

Conclusion:

We report six novel cases of oncocytic pancreatobiliary neoplasms with PRKACA fusions, including five with DNAJB1-PRKACA fusions. Our data proves that DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion is not a specific marker for the diagnosis of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. As in depth next-generation sequencing of tumors becomes a standard of care in the oncologic management of patients, we are likely to find more cases exhibiting similar molecular alterations, which might be amenable to targeted therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

The authors gratefully acknowledge the members of the Molecular Diagnostics Service in the Department of Pathology. The authors also thank Dr. Achim Jungbluth for his assistance with arginase immunohistochemical stain and albumin mRNA in-situ hybridization and Ms. Jordana Shapiro for her assistance with the figures.

FUNDING:

This work was funded in part by the Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology, by the Melamed Family Foundation, and by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Core Grant No. P30-CA008748.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Honeyman JN, Simon EP, Robine N, Chiaroni-Clarke R, Darcy DG, Lim II, et al. Detection of a recurrent DNAJB1-PRKACA chimeric transcript in fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Science 2014; 343:1010–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham RP, Jin L, Knutson DL, Kloft-Nelson SM, Greipp PT, Waldburger N, et al. DNAJB1-PRKACA is specific for fibrolamellar carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2015; 28:822–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon EP, Freije CA, Farber BA, Lalazar G, Darcy DG, Honeyman JN, et al. Transcriptomic characterization of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112:E5916–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham RP. Fibrolamellar Carcinoma: What Is New and Why It Matters. Surg Pathol Clin 2018; 11:377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adsay NV, Adair CF, Heffess CS, Klimstra DS. Intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasms of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol 1996; 20:980–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basturk O, Tan M, Bhanot U, Allen P, Adsay V, Scott SN, et al. The oncocytic subtype is genetically distinct from other pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm subtypes. Mod Pathol 2016; 29:1058–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang T, Askan G, Adsay V, Allen P, Jarnagin WR, Memis B, et al. Intraductal Oncocytic Papillary Neoplasms: Clinical-Pathologic Characterization of 24 Cases, With An Emphasis on Associated Invasive Carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2019; 43:656–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang T, Askan G, Zehir A, Adsay N, Akturk G, Bhanot U, et al. Mass-Forming Intraductal Neoplasms of the Biliary Tract Comprise Morphologically and Genetically Distinct Entities (Abstract). Modern Pathology 2018; 31:1927A. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, Shah RH, Benayed R, Syed A, et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): A Hybridization Capture-Based Next-Generation Sequencing Clinical Assay for Solid Tumor Molecular Oncology. J Mol Diagn 2015; 17:251–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Middha S, Zhang L, Nafa K, Jayakumaran G, Wong D, Kim HR, et al. Reliable Pan-Cancer Microsatellite Instability Assessment by Using Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Data. JCO Precis Oncol 2017:Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen R, Seshan VE. FACETS: allele-specific copy number and clonal heterogeneity analysis tool for high-throughput DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res 2016; 44:e131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng Z, Liebers M, Zhelyazkova B, Cao Y, Panditi D, Lynch KD, et al. Anchored multiplex PCR for targeted next-generation sequencing. Nat Med 2014; 20:1479–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH, Syed A, Middha S, Kim HR, et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med 2017; 23:703–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benayed R, Offin M, Mullaney K, Sukhadia P, Rios K, Desmeules P, et al. High Yield of RNA Sequencing for Targetable Kinase Fusions in Lung Adenocarcinomas with No Mitogenic Driver Alteration Detected by DNA Sequencing and Low Tumor Mutation Burden. Clin Cancer Res 2019; 25:4712–4722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov 2012; 2:401–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal 2013; 6:pl1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Askan G, Deshpande V, Klimstra DS, Adsay V, Sigel C, Shia J, et al. Expression of Markers of Hepatocellular Differentiation in Pancreatic Acinar Cell Neoplasms: A Potential Diagnostic Pitfall. Am J Clin Pathol 2016; 146:163–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reid LM, Sethupathy P. The DNAJB1-PRKACA chimera: Candidate biomarker and therapeutic target for fibrolamellar carcinomas. Hepatology 2016; 63:662–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu L, Hazard FK, Zmoos AF, Jahchan N, Chaib H, Garfin PM, et al. Genomic analysis of fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Hum Mol Genet 2015; 24:50–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engelholm LH, Riaz A, Serra D, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Johansen JV, Santoni-Rugiu E, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 Engineering of Adult Mouse Liver Demonstrates That the Dnajb1-Prkaca Gene Fusion Is Sufficient to Induce Tumors Resembling Fibrolamellar Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2017; 153:1662–1673 e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kastenhuber ER, Lalazar G, Houlihan SL, Tschaharganeh DF, Baslan T, Chen CC, et al. DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion kinase interacts with beta-catenin and the liver regenerative response to drive fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017; 114:13076–13084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomasini MD, Wang Y, Karamafrooz A, Li G, Beuming T, Gao J, et al. Conformational Landscape of the PRKACA-DNAJB1 Chimeric Kinase, the Driver for Fibrolamellar Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Sci Rep 2018; 8:720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dinh TA, Jewell ML, Kanke M, Francisco A, Sritharan R, Turnham RE, et al. MicroRNA-375 Suppresses the Growth and Invasion of Fibrolamellar Carcinoma. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 7:803–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham RP, Garcia JJ, Greipp PT, Barr Fritcher EG, Kipp BR, Torbenson MS . FGFR1 and FGFR2 in fibrolamellar carcinoma. Histopathology 2016; 68:686–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graham RP, Lackner C, Terracciano L, Gonzalez-Cantu Y, Maleszewski JJ, Greipp PT, et al. Fibrolamellar carcinoma in the Carney complex: PRKAR1A loss instead of the classic DNAJB1-PRKACA fusion. Hepatology 2018; 68:1441–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura H, Arai Y, Totoki Y, Shirota T, Elzawahry A, Kato M, et al. Genomic spectra of biliary tract cancer. Nature Genetics 2015; 47:1003–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shibata T, Arai Y, Totoki Y. Molecular genomic landscapes of hepatobiliary cancer. Cancer Science 2018; 109:1282–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drilon A, Somwar R, Mangatt BP, Edgren H, Desmeules P, Ruusulehto A, et al. Response to ERBB3-Directed Targeted Therapy in NRG1-Rearranged Cancers. Cancer Discov 2018; 8:686–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reid MD, Stallworth CR, Lewis MM, Akkas G, Memis B, Basturk O, et al. Cytopathologic diagnosis of oncocytic type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm: Criteria and clinical implications of accurate diagnosis. Cancer Cytopathol 2016; 124:122–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farhi DC, Shikes RH, Silverberg SG. Ultrastructure of fibrolamellar oncocytic hepatoma. Cancer 1982; 50:702–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomson M Evidence of undiscovered cell regulatory mechanisms: phosphoproteins and protein kinases in mitochondria. Cell Mol Life Sci 2002; 59:213–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ward SC, Huang J, Tickoo SK, Thung SN, Ladanyi M, Klimstra DS. Fibrolamellar carcinoma of the liver exhibits immunohistochemical evidence of both hepatocyte and bile duct differentiation. Mod Pathol 2010; 23:1180–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin CC, Yang HM. Fibrolamellar Carcinoma: A Concise Review. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2018; 142:1141–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basturk O, Chung SM, Hruban RH, Adsay NV, Askan G, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, et al. Distinct pathways of pathogenesis of intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasms and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Virchows Arch 2016; 469:523–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin RC, Klimstra DS, Schwartz L, Yilmaz A, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin W. Hepatic intraductal oncocytic papillary carcinoma. Cancer 2002; 95:2180–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lalazar G, Simon SM. Fibrolamellar Carcinoma: Recent Advances and Unresolved Questions on the Molecular Mechanisms. Semin Liver Dis 2018; 38:51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Casi Pharmaceuticals. Update On Phase 2 Trial Of ENMD-2076 In Fibrolamellar Carcinoma. Available from: http://www.casipharmaceuticals.com/investor-relations/news/casi-pharmaceuticals-provides-update-on-phase-2-trial-of-enmd-2076.

- 38.Kastenhuber ER, Craig J, Ramsey J, Sullivan KM, Sage J, De Oliveira S, et al. Road map for fibrolamellar carcinoma: progress and goals of a diversified approach. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 2019; 6:41–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]