Abstract

Here we designed and tested two highly specific quantitative TaqMan®-MGB-based reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) assays for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). The primers and probes for these assays were evaluated and found to have a limit of detection (LOD) of 0.005 plaque-forming units/PCR (pfu/PCR).

Keywords: RT-qPCR, MERS, Coronavirus, TaqMan®-MGB

Highlights

-

•

We designed two new RT-qPCR assays for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS).

-

•

These assays performed well with an LOD of 0.005 pfu/PCR.

-

•

Both assays are comparable to the currently used upE assay.

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome caused by a coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was first identified in 2012 during an outbreak of suspected pneumonia infections in Zarqa, Jordan [1]. Since 2012, MERS-CoV has led to an overall mortality rate of 35%, which is vastly higher (>50%) in immunocompromised and aged individuals than other people [2]. Currently, there are several published MERS-CoV RT-qPCR assays, with the upE RT-qPCR assay (University of Bonn Medical Center, Bonn, Germany) being the primary clinical diagnostic test [3]. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) also uses this assay in conjunction with their own designed assays (N2 and N3) for confirmatory testing [4]. In addition, RT-qPCR assays, targeting the ORF1a and ORF1b genes, have been published as well as an immunofluorescence assay (IFA), which is used for serological testing [3], [5].

Since 2012, multiple strains of MERS-CoVs have been identified and their genomes sequenced. The two MERS real-time qPCR assays presented in this paper were established using primers designed from an alignment of the original nine complete MERS genomes found in the GenBank database (GenBank accession numbers: KF192507, KC164505, KC667074, KF186567, KF186566, KF186564, KF186565, JX869059 and KC776174), using Clustal Omega (www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/services/web_clustalo). The alignment was assessed for highly conserved regions. Primer pairs and TaqMan®-minor groove binder (MGB) probes were then designed using both AlleleID 7.82 (PREMIER BioSoft, Palo Alto, CA; www.premierbiosoft.com) and Primer Express version 3.0.1 (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA; www.lifetechnologies.com), targeting the conserved regions (and avoiding all of the SNPs). The primers selected (Table 1 ) were assessed using TRIzol purified genomic RNA from cell-culture-derived MERS-CoV strain Jordan N3. Viral genomic RNA was extracted using the Qiagen EZ1 with the EZ1 Virus Mini Kit v2.0 (Qiagen, Valencia, CA; www.qiagen.com). All purified viral RNAs were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until use. The initial virus titer was 1.21 × 106 plaque-forming units (pfu)/ml. After extraction, the genomic RNA concentration was estimated at 1 × 103 pfu/μl, of which 5 μl were used for each reaction for a total of 5.0 × 103 pfu/PCR.

Table 1.

MERS9 and MERS27 assay information, including primer/probe sequences and concentrations.

| Assay | Genome target | Amplicon size | Primers/probe | Sequence (5′–3′) | Final conc (μM) | Sensitivity (PFU/PCR)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MERS9 | ORF4a | 62 bp | F217 | CGAATCGCTTGGTTGCTACA | 0.9 | 0.005 |

| R278 | CGGAGGTAGAGGGAACATCCA | 0.9 | ||||

| p239 | AGGATGGAGGAATCC – MGBNFQ | 0.2 | ||||

| MERS27 | ProdM | 56 bp | F456 | CATGCATTTCGGTGCTTGTG | 0.9 | 0.005 |

| R511 | TGGCCACGGTGACTTCATT | 0.9 | ||||

| p477 | CTACGACAGACTTCC – MGBNFQ | 0.2 |

*PCR = polymerase chain reaction; PFU = plaque-forming units; MGB = minor groove binder; ORF = open reading frame; SGP = soluble glycoprotein.

Limit of Detection (LOD) for all assays were measured in PFU/PCR; all sensitivities were done in triplicate and were positive in three of three replicates.

Two primer pairs, MERS9 (target: orf4a) and MERS27 (target: Product M), were initially screened using SYBR Green and Invitrogen SuperScript II One-Step RT-PCR reagents (Life Technologies) on the LightCycler 480 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, ID; www.roche.com). PCR products were then examined using gel electrophoresis. Both assays produced distinct (single-band) amplicons, and amplification was efficient based on real-time curves. Both amplicons (orf4a [62 bp] and Product M [56 bp]) were sequenced. The orf4a amplicon matched 100% to 112 complete MERS genomes currently in GenBank, while the Product M amplicon matched 120 complete MERS genomes. We therefore identified these two primer pairs as candidates for a MERS-CoV-specific RT-qPCR TaqMan®-MGB assay. TaqMan®-MGB probes (Table 1) from Life Technologies were optimized and additional evaluations of these two assays were performed using Invitrogen SuperScript II One-Step RT-PCR reagents using the following protocol: 1× master mix, 4 mM MgSO4, 2 mM dNTPs, 200 nM probe, and 0.4 units of Superscript RT/Platinum Taq mix in a 20 μl reaction. Cycling conditions were: 50 °C for 15 min; 95 °C for 5 min; 45 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 20 s; 40 °C for 30 s. All RT-qPCR assay optimizations and evaluations were conducted using the LightCycler 96 system (Roche Applied Science).

Optimal primer concentrations (earliest Cq and highest end point fluorescence [EPF]) for the two assays were chosen prior to further testing by using an internal protocol, resulting in a final concentration of 0.9 μM for both assays. Sensitivity (limit of detection, LOD) was then established by generating a standard curve for MERS-CoV genomic RNA (from 5.0 × 103 to 0.0005 pfu/PCR). Confirmatory LOD testing for both assays (MERS9 and MERS27) was performed by testing 60 replicates of MERS-CoV genomic RNA at the preliminary LOD of 0.005 pfu/PCR. For the MERS9 assay (orf4a), 57 of 60 replicates were positive (average Cq 36.94), and 58 of 60 were positive (average Cq 36.65) for the MERS27 (Product M), giving 95% and 96.7% confidence, respectively, that MERS can be detected at a concentration of 0.005 pfu/PCR using the two assays (Table 1).

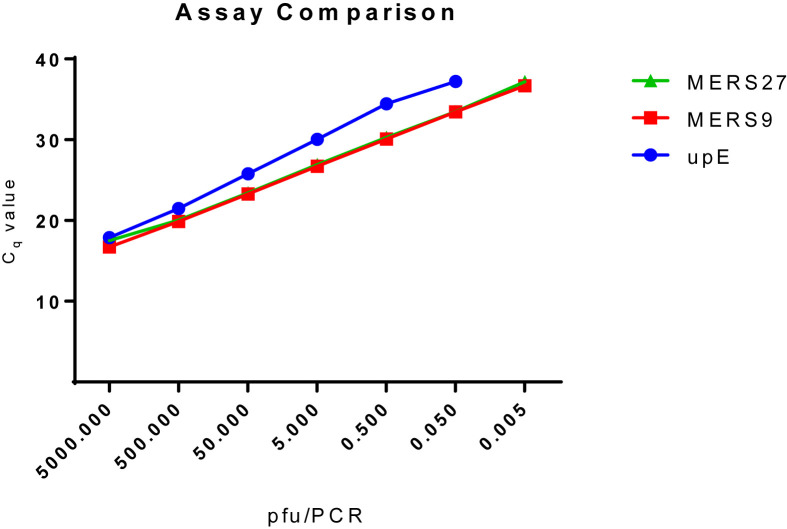

The two assays were then compared with the upE RT-PCR assay [4], as it is the primary assay used for molecular testing for MERS-CoV. The upE assay was performed as described [4], with the lone exception that it was tested on a Roche LightCycler 96 system, instead of the ABI 7500 platform. The data reveals that the preliminary upE LOD using the MERS-CoV strain Jordan N3 is 0.05 pfu/PCR (Fig. 1 ). A confirmatory LOD was performed for the upE assay at 0.05 pfu/PCR, which was detected 60/60 times with an average Cq of 39.17. This is compared with the MERS9 and MERS27 assays, which both were shown to have a confirmatory LOD of 0.005 pfu/PCR (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the MERS9, MERS27 and upE RT-PCR assays. The MERS27 (green triangles), MERS9 (red squares), and upE (blue circles) assays were tested using a 1:10 standard dilution from 5 × 103 pfu/PCR to 0.005 pfu/PCR. Average PCR assay Cq values at each concentration are shown for comparison. Only data where 3/3 replicates tested positive are shown. This comparison shows that the MERS27 and MERS9 assays were able to detect MERS-CoV strain Jordan N3 at a lower concentration than the upE assay.

Lastly, exclusivity testing (the ability of the assay to only detect MERS and not cross-react with closely related taxa) was conducted using the MERS9 and MERS27 assays. A panel of 23 respiratory disease-causing organisms was assembled to test the specificity of the assays (Table 2 ). All viruses were tested at a concentration 1000-times the MERS9 and MERS27 LOD: 5 pfu/PCR for genomic viral RNA. Genomic bacterial DNA was tested at 100 pg/PCR, which is generally 1000-times the LOD of most published PCR assays. No cross-reactivity was seen for either assay using the “nearest neighbor” RNA/DNA panel. Additional inclusivity testing (the ability of the assays to detect all strains of MERS) was not performed due to the limited availability of different MERS-CoV strains.

Table 2.

Exclusivity panel of organisms and their strains tested to show no crossreactivity with both MERS assays.

| Organism | Strain | Sourcea | Concentration testedb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bordetella parapertussis | 12822 (ATCC BAA-587D) | ATCC | 100 pg |

| Bordetella pertussis | 18323 (ATCC 9797D) | ATCC | 100 pg |

| Human coronavirus | A59 | USAMRIID | 5 pfu |

| Human coronavirus | JHM | USAMRIID | 5 pfu |

| Human coronavirus | MHV-2 | USAMRIID | 5 pfu |

| Human coronavirus (SARS) | CDC 809921 | USAMRIID | 5 pfu |

| Coxiella burnetti | AD-25 production seed, California 1948 | NIH | 100 pg |

| Haemophilous influenzae | Rd KW20 (ATCC 51907D) | ATCC | 100 pg |

| Influenza A (H1N1) | A/SW/GB/19582/92 | USAMRIID | 5 pfu |

| Influenza A (H3N2) | A/SW/IA/1/99 | USAMRIID | 5 pfu |

| Influenza A (H3N8) | A/MAL/ALB/16/87 | USAMRIID | 5 pfu |

| Influenza A (H5N2) | A/DK/SC/318328-3/04 | USAMRIID | 5 pfu |

| Influenza A (H7N2) | A/CK/NY/273874/03 | USAMRIID | 5 pfu |

| Influenza A (H7N3) | A/TY/UT/24721-10/95 | USAMRIID | 5 pfu |

| Influenza B | B/Ohio/01/2005 (B/Victoria/2/87 genetic group) | USAMRIID | 5 pfu |

| Influenza B | B/Florida/07/2004 (B/Yamagata/16/88 genetic group) | USAMRIID | 5 pfu |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | NCTC 9633 (ATCC 13883) | ATCC | 100 pg |

| Legionella pneumophila | Philadelphia-1 (ATCC 33152) | ATCC | 100 pg |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | FH strain of Eaton Agent (ATCC 15531) | ATCC | 100 pg |

| Neisseria meningitidis | Murray (ATCC 13090) | ATCC | 100 pg |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Boston 41501 (ATCC 27853) | ATCC | 100 pg |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Wood 46 (ATCC 10832) | ATCC | 100 pg |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | NCTC 7465 (ATCC 33400) | ATCC | 100 pg |

USAMRIID = United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases; NIH = National Institutes of Health; ATCC = American Type Culture Collection.

Concentration tested was per 5 μL added to each RT-PCR reaction.

Viruses can rapidly change with each outbreak, and it has been estimated that MERS-CoV has been evolving at a rate of 1.12 × 10−3 substitutions/site per year [6] for clade B sequences (this clade includes all sequences, except those of the Jordan-N3/2012 and EMC/2012 isolates). Due to the genetic diversity that has been shown for MERS-CoV, as the genomes of new samples are sequenced, it is important to ensure current RT-qPCR assays are still reliable for clinical testing. A subsequent BLAST analysis of the recent RefSeq database (March 2015) of all four primers and two TaqMan-MGB probe sequences from the MERS9 and MERS27 assays resulted in 100% matches to all 75 currently accessible complete genomes representing MERS-CoVs. While we realize similarity comparisons by BLAST do not guarantee the reliability of a method, the present assays were designed using available complete genomes, and should be able to detect the additional 66 MERS isolates found in the current RefSeq database. Nonetheless, additional assay testing will be conducted upon the acquisition of additional MERS-CoV strains to corroborate our assertion. It is also likely that since the assays were designed using what are predicted to be conserved regions, new isolates should also be detected using one or both of the assays established here. Obviously, having more than one assay for any infectious agent (particularly an RNA virus that is rapidly mutating) is preferable, because of potential for “assay degradation” due to nucleotide alterations. In conclusion, we have established two specific and sensitive assays for the detection of MERS-CoV genomic RNA, which can now be added to the molecular detection/diagnostic toolbox, and offer a new viable option for virus detection in infected individuals.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) project ID no. CB3901. The opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations in this report are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army.

References

- 1.Al-Abdallat M.M., Payne D.C., Alqasrawi S., Rha B., Tohme R.A., Abedi G.R. Hospital-associated outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a serologic, epidemiologic, and clinical description. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014;59(9):1225–1233. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gralinski L.E., Baric R.S. Molecular pathology of emerging coronavirus infections. J. Pathol. 2015;235(2):185–195. doi: 10.1002/path.4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corman V.M., Eckerle I., Bleicker T., Zaki A., Landt O., Eschbach-Bludau M. Detection of a novel human coronavirus by real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. Euro Surveill. 2012;(39):17. doi: 10.2807/ese.17.39.20285-en. pii: 20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu X., Whitaker B., Sakthivel S.K., Kamili S., Rose L.E., Lowe L. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay panel for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52(1):67–75. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02533-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corman V.M., Muller M.A., Costabel U., Timm J., Binger T., Meyer B. Assays for laboratory confirmation of novel human coronavirus (hCoV-EMC) infections. Euro. Surveill. 2012;(49):17. doi: 10.2807/ese.17.49.20334-en. pii: 20334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cotten M., Watson S.J., Zumla A.I., Makhdoom H.Q., Palser A.L., Ong S.H. Spread, circulation, and evolution of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. MBio. 2014;(1):5. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01062-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]