Abstract

Background

A 45-year old woman of Cambodian ethnic background presented with fatal respiratory failure due to a severe diaphragmatic dysfunction. Two years before, she had developed early onset of urinary symptoms.

Methods and results

Neuroimaging showed atrophy of the spine and medulla as well as a leukodystrophy affecting both supra- and infra-tentorial regions. At autopsy, polyglucosan bodies (PB) were seen in several peripheral tissues, including the diaphragm, and nervous tissues such as peripheral nerves, cerebral white matter, basal ganglia, hippocampus, brainstem and cerebellum. Immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy of the brain revealed an exclusive astrocytic localization of the PB. The diagnosis of adult polyglucosan body disease (APBD) was confirmed by enzymatic and molecular studies.

Conclusion

Storage of abnormal glycogen in astrocytes is sufficient to cause the leukodystrophy of APBD. Since brain glycogen is almost exclusively metabolized in astrocytes, this observation sheds light on the pathophysiology of APBD. In addition, this is the first report of an APBD patient presenting with a subacute diaphragmatic failure.

Abbreviations: PB, polyglucosan body; PAS, periodic acid Schiff; APBD, adult polyglucosan body disease; GBE, glycogen branching enzyme; GSD, glycogen storage disease; NF, neurofilaments; LFB, Luxol-fast blue; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; AQP4, aquaporin 4; MBP, myelin basic protein

Keywords: Adult polyglucosan body disease, Glycogenosis type IV, Brain glycogen metabolism, Astrocytes

Highlights

► We diagnosed a 45-year old woman with adult polyglucosan body disease (APBD). ► The patient died from a severe diaphragmatic dysfunction. ► At autopsy, polyglucosan bodies were abundant in the diaphragm. ► In the brain, polyglucosan bodies were exclusively present in astrocytes. ► Abnormal glycogen in astrocytes is sufficient to cause the leukodystrophy of APBD.

1. Introduction

Adult polyglucosan body disease (APBD) is a rare progressive neurological disorder due to a deficiency in glycogen branching enzyme (GBE) (Bruno et al., 1993, Moses and Parvari, 2002). Polyglucosan bodies (PB) refer to the accumulation of glucose polymers, staining strongly with periodic acid Schiff (PAS), due to the abnormal synthesis and degradation of glycogen. Glycogen storage type IV (GSD IV) was first described in neonates and children as Andersen disease. In the adult-onset form (APBD), the symptoms begin in the fourth to sixth decade. The most frequent inaugural symptom is bladder dysfunction, often followed by motor and sensory deficits, and mild cognitive impairment in about half of the patients. APBD is characterized by a leukodystrophy on brain MRI and a severe atrophy of the spine and medulla (Lossos et al., 1998). APBD is autosomal recessive, affecting predominantly Ashkenazi Jewish families (Moses and Parvari, 2002).

We report detailed neuropathological analyses of an APBD case with unusual clinical presentation. This study enlarges the phenotypic spectrum of GSD IV and contributes to expand our understanding of brain glycogen metabolism.

2. Patient and methods

A 45 year-old Cambodian woman was admitted in the emergency room because of subacute respiratory failure. Family history was uninformative and there was no consanguinity. Over the preceding 5 years, the patient had been treated for breast cancer. On admission, the patient required an emergency tracheal intubation because of hypercapnic coma. The first line of investigations did not reveal any sign of infection or inflammation, neither pulmonary embolism. Proximal four-limb weakness was noticed with hyperreflexia, suggesting a motor neuron disease. Nevertheless, the electromyography performed at bedside was normal, as well as standard biochemical analyses in blood and cerebrospinal fluid. Full-body CT scan displayed metastases in the liver and in the spinal column.

On further inquiry, family members reported bladder dysfunction, which started about 2 years earlier, and mild difficulty walking over the past months. In addition, the family indicated that the patient had suffered from dyspnea for a couple of weeks. The clinical status of the patient worsened as she developed a pulmonary infection. Within a few days, she suffered from a severe acute respiratory syndrome and died 3 weeks following admission.

The study was approved by local ethics committees and written informed consent for autopsy was obtained from the patient's relatives. In the brain, the following regions were analyzed: midfrontal gyrus, superior temporal gyrus, caudate nucleus, thalamus and mamillary bodies, hippocampus, calcarin sulcus, cerebellum, substantia nigra, motor cortex, lenticular nucleus, pons, medulla oblongata, spinal cord, orbital–frontal cortex and temporal amygdala. Details on the antibodies that were used for immunohistochemistry are listed in the Supplementary table. In order to confirm the cellular localization of PB, the immunolabelling of neurofilaments (NF) was followed by PAS stain. On muscular and neural sections PAS technique, Masson's Trichromic stain, Congo Red and Luxol-fast blue (LFB) staining were performed. Specimens of sural nerve and musculocutaneous nerve were analyzed by transmission electron microscopy.

The enzymatic activity of GBE was assayed in the patient's leukocytes obtained prior to death using an indirect method (Brown and Brown, 1966). Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using standard procedures. The 16 exons and exon/intron boundaries of the GBE1 gene were amplified and PCR products were sequenced using the Big-Dye terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and an ABI Prism 3730 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

3. Results

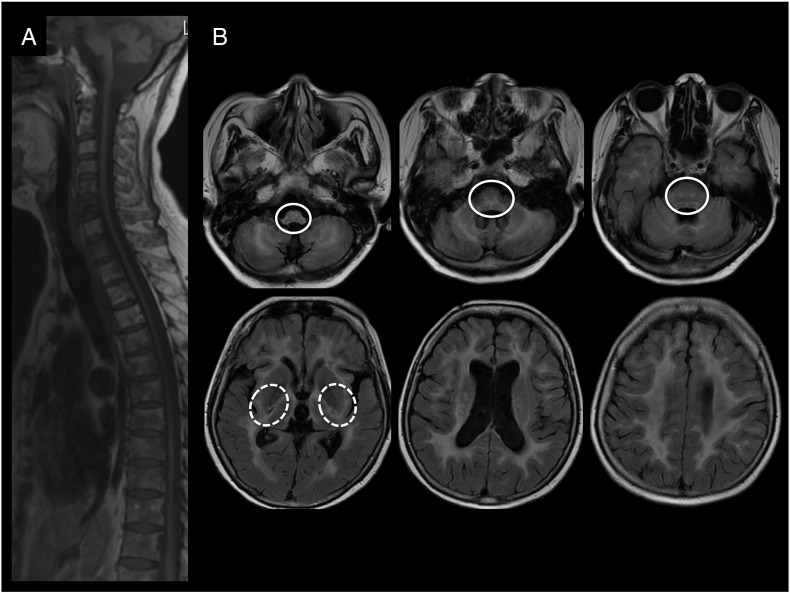

Neuroimaging on a 3 T scan displayed noteworthy atrophy of the medulla and of the spinal cord (Fig. 1A). Brain MRI also revealed a diffuse white matter disease (Fig. 1B). Hyperintense white matter abnormalities on T2 and FLAIR sequences were present in the medulla and pons, in the pyramidal tracts and the medial lemniscus (Fig. 1B). In the cerebral hemispheres, white matter lesions were symmetric and confluent, affecting the frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital areas. The external capsule and the posterior limb of the internal capsule were also affected while the anterior limb was spared (Fig. 1B). The abnormal white matter areas had normal or hypointense signal on T1-weighted images (data not shown). In addition, there was diffuse cortical and subcortical atrophy, mild vermian atrophy and thin corpus callosum (data not shown). None of the white matter lesion showed contrast enhancement. This pattern suggested APBD due to GBE deficiency.

Fig. 1.

Brain and spinal MRI. A) T1 sagittal scan showing important medulla and spinal cord atrophy. B) FLAIR axial scans showing hyperintense white matter changes in the periventricular regions, the external capsule and the posterior limb of the internal capsule (dashed circles), the cerebellar hemispheres and in the pyramidal tracts and medial lemniscus of the medulla and pons (solid circles).

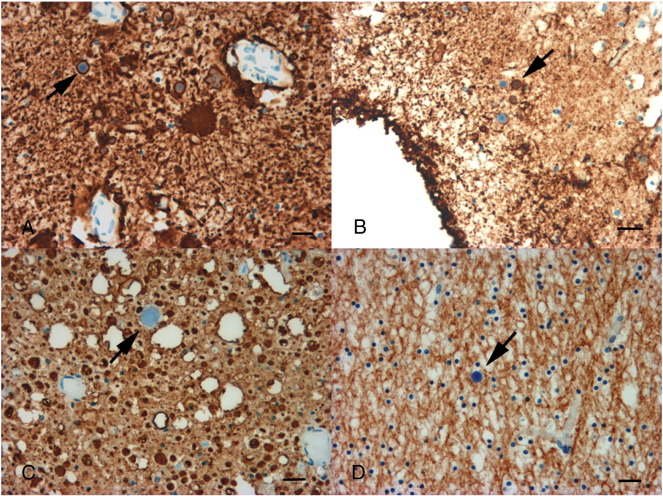

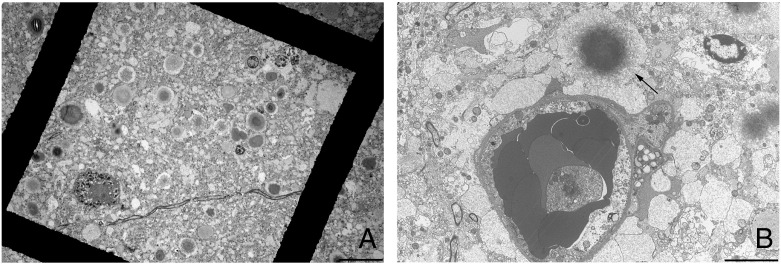

At autopsy, numerous PB were observed in the myoepithelial cells of the sweat glands, the cardiac and diaphragmatic myocytes, and in the sural nerve (Supplementary Figs. 1A, B, C and D). Of note, PB were relatively more abundant in the diaphragm than in limb muscles. In the sural nerve, PB appeared surrounded by LFB, compatible with their localization in Schwann cells rather than in axons (Supplementary Fig. 2), but were not found in serial semi-thin sections. Externally, the cerebrum and brainstem were normal. By contrast, the spinal cord was severely and globally atrophic (Supplementary Fig. 3). Examination of the brain sections showed atrophy of the corpus callosum associated with grayish discoloration of the white matter with sparing of the U fibers, particularly in the frontal lobes. PB were present in all examined cerebral regions, within both the white and gray matters, central gray nuclei, cerebellum and brainstem. They were particularly abundant in the hippocampus (Supplementary Fig. 4). PB were localized within the astrocytes, particularly in the astrocytic endings, as shown with anti-GFAP and anti-AQP4 immunostaining (Figs. 2A and B). By contrast, no PB were found in other cell types of the CNS, such as neurons (Fig. 2C), oligodendrocytes (Fig. 2D) or microglia (data not shown). PAS stain performed on NF immunolabeled sections confirmed the absence of PB in neurons (data not shown). Electron microscopy confirmed the exclusive astrocytic localization of PB (Fig. 3 ). PB were associated with white matter pallor, diffuse microglial activation and astrogliosis. Axonal loss and swelling suggested degeneration rather than demyelination (Figs. 2C and D). Likewise, the diffuse white matter disease hyperintensity on T2-weighted MRI images seen in the patient reflected this concurrent myelin and axonal loss. Examination of the spinal cord showed many PB in the gray and white matter, but sparing of motor neurons (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Fig. 2.

Cellular localization of PB in the brain (specimen of frontal lobe white matter). A) Anti-GFAP immunostaining of astrocytes. Astrocytic processes contain PB (arrow). B) Anti-AQP4 immunostaining of reactive astrocytes. PB are surrounded by a positively stained rim showing their intra-astrocytic localization (arrow). C) Anti-NF immunostaining of axonal swellings. PB are not surrounded by the immunostaining, suggesting an extra-axonal localization (arrow). D) Anti-MBP immunostaining of myelin. PB are not surrounded by the immunostaining, suggesting an extra-axonal localization (arrow). Note that there is no evidence of demyelination. Scale bar 10 μm.

Fig. 3.

Electron microscopy of the dentate gyrus. A) Low power, showing PG of different sizes, at a distance from neuron nuclei. Scale bar 20 μm. B) Blood vessel surrounded by basal lamina in contact with astrocytes, forming the blood–brain barrier. PB have an electron dense core with a less dense periphery and a characteristically fibrillar pattern. A PB is found in an astrocyte close to a blood vessel (arrow). Scale bar 10 μm.

Enzymatic studies displayed a significant reduction of the branching enzyme compared to healthy controls. A concurrent normal control was also sampled and analyzed on that same day confirming a reduced GBE activity in the patient's leukocytes — 1.01 U/g protein for the control vs 0.22 U/g for the patient. Molecular studies identified 2 compound heterozygote mutations in the GBE1 gene: (i) p.H319Y mutation (c.955C>T) in exon 7, a mutation already identified in an antenatal GSD IV presentation (R. Froissart, unpublished data) and (ii) p.G353A mutation (c.1058G>C) in exon 8, a missense mutation not previously reported. These 2 mutations were likely pathogenic since they affect conserved residues of the GBE protein, are predicted to alter protein function (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph/) and are absent from control sequences (http://browser.1000genomes.org/index.html and http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP).

4. Discussion

The unique features in this APBD patient are the prominent diaphragmatic involvement leading to subacute respiratory failure and, in the CNS, the restricted localization of the PB to astrocytes, sparing other cell types including neurons. Brain MRI showing a specific pattern of white matter abnormalities as recently described (Mochel et al., 2012), together with early onset of urinary symptoms and severe spinal cord atrophy was suggestive of APBD, which was confirmed by neuropathology, enzymatic and molecular testing. To our knowledge, this is the first APBD patient of Cambodian origin. As expected, this patient did not harbor the most common Ashkenazi Jewish mutation (Y329S). This confirms that APBD should be considered in patients with non-Jewish ethnic background. Although this is the first case report of GSD IV affecting the diaphragm, this observation is reminiscent of the involvement of the diaphragm, heart and skeletal muscle in GSD II (Pompe disease) caused by the 1,4 alpha glucosidase. Moreover, one of the 2 mutations identified in our patient has previously been associated with an antenatal presentation of GSD IV characterized by severe muscular involvement.

This neuropathological study addresses the controversial cellular localization of PB in the brain, which is likely to have an impact on therapeutic strategies in APBD. Unlike previous observations where PB were also reported in neurons (Gray et al., 1988, Robitaille et al., 1980), our patient is the first confirmed GBE deficient patient in whom PB were consistently seen in astrocytes only. The observation that the exclusive astrocytic localization of the PB is sufficient to cause APBD due to GBE deficiency is in agreement with what is known about brain glycogen metabolism (Benarroch, 2010). Glycogen is almost exclusively localized in astrocytes even though neurons have the capacity to synthesize it. Neurons that recover their capacity to synthesize glycogen are indeed driven to apoptosis (Vilchez et al., 2007). The glycogen present in astrocytes is converted into lactate and then transmitted to neurons where it is used as a main substrate (Magistretti and Allaman, 2007). The accumulation of glycogen in astrocytes due to GBE deficiency is likely to result in a lack of energy substrates, first for astrocytes and then for neurons. Accordingly, the relative young age of our patient at autopsy is a likely explanation for the exclusive presence of PB in astrocytes at this early stage of the disease. Considering that this patient already manifested neurological symptoms – i.e. urinary symptoms and pyramidal signs – and typical neuroimaging finding of APBD, our report therefore emphasizes that the presence of PB in astrocytes is sufficient to cause APBD.

Astrocytic involvement was also found in the spinal cord of our patient. Microscopy showed no motor neuron damage – i.e. normal abundance and morphology – contrary to the reduced number and distorted morphology of axons without significant myelin changes. Of note, severe spinal cord and medulla atrophy is also seen in Alexander disease due to GFAP mutations. The predominant glial involvement in Alexander disease and APBD may therefore underlie the severe spinal atrophy in both diseases.

While it is likely that the metastatic disease of our patient contributed to her death, this observation raises awareness of the possible involvement of the diaphragm in APBD, as documented here by pathology. The exclusive astrocytic localization of PB in the brain that we found also broadens our understanding of the pathophysiology of APBD and brain glycogen metabolism.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Thierry Maisonobe for helpful discussion and Pr Charles Duyckaerts for his critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2012.12.065.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary materials

References

- Benarroch E.E. Glycogen metabolism: metabolic coupling between astrocytes and neurons. Neurology. 2010;74:919–923. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d3e44b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B.I., Brown D.H. Lack of an alpha-1,4-glucan: alpha-1,4-glucan 6-glycosyl transferase in a case of type IV glycogenosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1966;56:725–729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.56.2.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno C. Glycogen branching enzyme deficiency in adult polyglucosan body disease. Ann. Neurol. 1993;33:88–93. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray F., Gherardi R., Marshall A., Janota I., Poirier J. Adult polyglucosan body disease (APBD) J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1988;47:459–474. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lossos A. Adult polyglucosan body disease in Ashkenazi Jewish patients carrying the Tyr329Ser mutation in the glycogen-branching enzyme gene. Ann. Neurol. 1998;44:867–872. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistretti P.J., Allaman I. Glycogen: a Trojan horse for neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:1341–1342. doi: 10.1038/nn1107-1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochel F. Adult polyglucosan body disease: natural history and key magnetic resonance imaging findings. Ann. Neurol. 2012;72:433–441. doi: 10.1002/ana.23598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses S.W., Parvari R. The variable presentations of glycogen storage disease type IV: a review of clinical, enzymatic and molecular studies. Curr. Mol. Med. 2002;2:177–188. doi: 10.2174/1566524024605815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robitaille Y., Carpenter S., Karpati G., DiMauro S.D. A distinct form of adult polyglucosan body disease with massive involvement of central and peripheral neuronal processes and astrocytes: a report of four cases and a review of the occurrence of polyglucosan bodies in other conditions such as Lafora's disease and normal ageing. Brain. 1980;103:315–336. doi: 10.1093/brain/103.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilchez D. Mechanism suppressing glycogen synthesis in neurons and its demise in progressive myoclonus epilepsy. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:1407–1413. doi: 10.1038/nn1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials