Abstract

While industralization programmes have been central to the development of Asia-Pacific states and city-regions over the past half-century, service industries are increasingly important as instruments of urban growth and change. The purpose of this paper is to establish service industries as increasingly significant aspects of urban development within the Asia-Pacific, and to propose a conceptual and analytical framework for scholarly investigation within this important research domain. To this end the paper explores a sequence of related themes and issues, concerning the larger developmental implications of urban services growth (or tertiarization), the facets of urban transformation associated with tertiarization, and a preliminary typology of urban service functions which acknowledges the rich diversity of service vocations and stages of development within the Asia-Pacific. The paper concludes that “advanced services”—specialized, intermediate service industries, advanced-technology services, and creative service industries—will be quite crucial to the development of city-regions within the Asia-Pacific, with respect to employment growth and human capital formation, to the urban economic (or export) base, to the operation of flexible production systems, and to competitive advantage. The development of these urban service poles will require innovative policy commitments and regulatory adjustments, as will the multi-centred specialized urban service corridors which function as engines of regional economic growth, and which provide platforms for national modernization and responses to the pressures (and opportunities) of globalization. To date, urban and regional development strategies for service industries within the Asia-Pacific have privileged globalization, industrial restructuring, and modernization aims, but there is also an encouraging record of more progressive planning experimentation in some jurisdictions, incorporating principles of sustainability and co-operative development. There is also increasing interest in policies to support cultural and creative industries among Asia-Pacific city-regions, informed by some recent urban policy experimentation in this domain. These experiences can offer models for further policy and programmatic innovation in the 21st century, as service industries continue to play larger roles in urban and regional development within the Asia-Pacific.

Chapter 1. Introduction: service industries and urban transformation

Service industries have accounted for an increasing share of labour, output, and trade among the advanced economies of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) over the last quarter century. This phenomenon of sustained growth in services (both in absolute and relative terms) can be observed at the national level among OECD member countries in terms of the changing composition of gross domestic product (GDP) and employment, but is especially pronounced at the urban or city-region scale. Final demand service industries (for example retail, education, and most government services) are strongly tied to large metropolitan consumer markets, while intermediate services are even more spatially centralized, reflecting the influence of urban and agglomeration economies on the locational pattern of specialized, contact-intensive services. Following the protracted decline of traditional manufacturing, service industries have led employment growth among most advanced city-regions over the last three decades.

But the significance of service industries to urban (and especially metropolitan) development extends beyond measures of growth, as important as these are, to encompass comprehensive processes of change. At the broadest theoretical level we can discern intimate associations between service industries and redefining urban socio-economic processes and stylistic innovation over the past century. The growth of high-rise office complexes was an integral feature of the production of modernist urban landscapes, while advanced service industries have been central to the experiences of post-industrialism, flexible specialization, and post-modernism which have transformed urban landscapes, production sectors, and occupational structures over the past several decades. More particularly, service industries are directly involved in fundamental shifts in the urban economic base and industrial structure, but are also deeply implicated in the reconfiguration of regional structure, the metropolitan space-economy, and urban form. The rapid growth of service occupations among the most advanced post-industrial cities has also had profound implications for urban class structure and for the metropolitan social morphology, and is associated with the evolution of urban culture and even political preferences.

In addition to these internal facets of urban transformation, service industries are also influential in the repositioning of cities and city-regions within external networks and systems. Growth in urban service exports and trade may be significant in the recasting of city–hinterland relations, and in the reordering of national urban hierarchies, and is quite decisive in the emergence of global city-regions. At the apex of the global city hierarchy the most privileged status is associated with high concentrations of specialized banking and finance, and the projection of corporate power, as well as encompassing a more diversified ensemble of specialized service industries.

These far-reaching aspects of urban service growth (or tertiarization) are most pronounced within the mature societies of Europe and North America, but are increasingly relevant to an appreciation of urban growth and change within Asia-Pacific cities. The purpose of this paper is to propose a framework for investigating the influence of service industries on urban development within the Asia-Pacific, with an emphasis on dimensions of transformational change, both within the metropolis, and at the broader urban systems level. This entails an assessment of economic implications of tertiarization for cities and city-regions within the Asia-Pacific, including the emergence of new urban functions or vocations, and constituent shifts in the urban economic base, employment structure, and mix of industries. Advanced or specialized services—especially, banking and finance, business and trade services, professional and ‘informational’ service activities, among others—are increasingly associated with modernization aspirations among the region's post-industrial, late-industrial and transitional societies, as reflected in development strategies and programmes. However, the parameters of urban change within the Asia-Pacific associated with tertiarization extend beyond this economic dimension to encompass impacts of service industry growth on urban structure and form, the built environment, social class and social morphology: i.e. the comprehensive facets of transformation (and re-imaging) of cities increasingly engaged in advanced services production, exchange, trade and consumption.

Our conceptual point of departure is that the expansion of services activity within Asia-Pacific cities and city-regions represents not only incremental urban growth and change, but, rather, consequential shifts in the role of urban areas within advanced production systems, in the globalization of trade flows, and in new social divisions of production labour. Accordingly, the analytical focus will be on service industries and activities which the research literature has identified as ‘propulsive’ in urban growth and development; i.e. intermediate (rather than final demand) services, specialized service industries, and knowledge- and technology-based or informational services. At the same time, the record of urban services growth within the Asia-Pacific region discloses wide variations in stages of services development and mixes of service activity from place to place, and this variegation must be acknowledged in the interests of presenting a more rounded perspective on the experience than an exclusive discussion of leading edge examples would allow. Indeed, some of the most interesting and instructive stories of urban tertiarization within the Asia-Pacific concern the juxtaposition of informal and advanced services in transitional societies, with ensuing social, land use, and planning conflicts.

Following this introduction, the paper offers a discussion of contrasts in developmental trajectories between the ‘mature’ Atlantic core regions and those of the dynamic Pacific core (Chapter 2), including an acknowledgement of industrialization as the dominant development paradigm for much of the Asia-Pacific since the 1960s. Defining elements of advanced urban tertiarization are identified, and are constituted within a taxonomy of global cities' service functions. The following section (Chapter 3) addresses both commonalities and contrasts in service industry developments among city-regions of the Atlantic and Pacific cores, and identifies five principal implications of service growth for urban change within the Asia-Pacific. These include the role of service industries in reshaping urban development trajectories, in the reconfiguration of urban space, and in urban social and cultural change, as well as the ramifications of accelerated tertiarization for the everyday experiences of city life and for urban identity and image.

Next, the paper offers a typology of urban services development within the Asia-Pacific (Chapter 4), derived from levels of services specialization as well as from urban scale. The spatial development of specialized services production within the Asia-Pacific is described, including both polarized patterns and more extended territories of tertiary sector growth, observed in the form of incipient urban corridors. These corridors (or clusters) represent a functionally specialized form of territorial development which exhibit features of co-operation as well as competition, and in part express policy responses to the pressures of globalization.

The two final substantive chapters address planning issues and experiences associated with the development of the urban service sector. The first (Chapter 5) describes the basic evolution of local policy responses to urban tertiarization over the last quarter-century, from early development control policy regimes imposed to manage negative externalities of rapid service industry growth, to more balanced approaches, which combined developmental as well as regulatory elements. This chapter concludes with a set of important processes and events which have shaped a new policy environment for urban service industries in the early 21st century. Next, Chapter 6 extends this discussion, by introducing a framework of six strategic urban policy models which are deployed in cities within the Asia-Pacific, including experiments in progressive planning (co-operative regional development, sustainable city-regions), as well as familiar models associated with globalization and restructuring objectives. The paper concludes with suggestions for a research agenda, emphasizing developmental and transformational implications of service industry growth for city-regions within the Asia-Pacific.

Chapter 2. Services and city-regions in a global context

Among the defining attributes of economic globalization is a perception of increasing convergence and co-dependency of industrial production and exchange systems, impelled by factors which include market deregulation and integration, technological innovation and diffusion (notably production and telecommunications technologies), investments in strategic transportation infrastructure, and international migration. Salient features of this globalizing economic environment include the well-documented rise of multinational corporations (MNCs) and enterprises (MNEs), a range of public and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) designed to support, foster, or (in some cases) negotiate international trade and investment (as well as a growing roster of NGOs which vigorously resist globalization), and a new international division of labour (NIDL) engaged in product fabrication and assembly, organized and directed by MNCs and MNEs (Cohen, 1981, Ho, 1991). A related phenomenon is the rise of a hierarchy of ‘world’ (Friedmann and Wolff, 1982) or ‘global’ (Sassen, 1991) cities, at the apex of which are (by convention) New York, London and Tokyo, within which multinational head offices, intermediate banking and finance, and supporting specialized services are concentrated. These world cities direct industrial production on a global basis, are increasingly linked by air travel networks and sophisticated telecommunications systems, and perform strategic gateway roles for international trade and investment. Nor is the influence of these world cities confined to the economic sphere: globalization processes increasingly incorporate the production and dissemination of culture, in the broader sense. The capitals and dominant metropoles are both signifying elements of national culture (vide Paris and Beijing), and also centres of innovation, ideas, knowledge and creativity, therefore constituting key points in the exchange and diffusion of cultural values, norms and trends (Zukin, 1995). The dominance of these world cities in both economic and cultural domains entails notions of imposition, hegemony and exploitation, so there is to be sure a contested aspect to the global roles of metropolitan cities, and the transnational corporations and institutions domiciled within.

The formation of continental (and even supra-continental) trading associations may also be viewed at least in part as a feature of, or response to, the pressures and opportunities of economic globalization. These associations, which include the European Union (EU), North American Free Trade Association (NAFTA), and Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation (APEC), were established at different times, with a mix of motivations, and exhibit quite different levels of organizational maturity. However, support for freer trade and market integration within some of these associations reflects not only an attempt to enable member country firms to achieve economies of scope and scale in order to compete more effectively internationally, but also a desire to establish a stronger bulwark against the more destabilizing effects of globalizing trade and capital flows. In these respects, at least, the emergence of large, multinational trading blocs can be interpreted as a feature of globalization (see Scott et al. (1999) for further discussion of this important phenomenon).

The two dominant geo-spatial spheres of this globalizing economic production and trading system can be construed as follows: first, the advanced industrial (or post-industrial) nations and regions of an ‘old core’ centered on the North Atlantic, including the EU, and the mature, highly urbanized areas of eastern North America; and, secondly, a dynamic (and over much of the past quarter-century, rapidly growing) ‘new core’ situated within the Pacific Basin, incorporating East and Southeast Asia, Australasia, and those nations or regions of the Americas within the Pacific littoral (Daniels, 1998), an aggregation of nations which roughly corresponds to (and perhaps enjoys a measure of validation from) the APEC designation.1 Together, these massive economic spheres contain an overwhelming preponderance of the world's industrial production, advanced technology capacity, banking centres and financial assets, and specialized service industries. The leading nations and constituent regions of the Atlantic and Pacific spheres share or exhibit (albeit unevenly) important attributes of advanced economic and socio-economic development, including skilled and productive labour, high-value industrial outputs, and leading-edge production and distribution infrastructures, in contrast to many of the developing (or underdeveloped) countries of the ‘south’, the latter comprising much of Africa, South Asia, and Latin America, which are relatively deficient in these assets.2

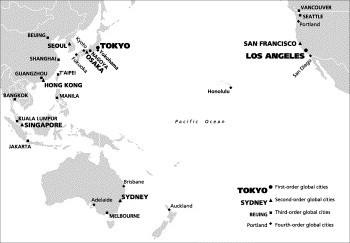

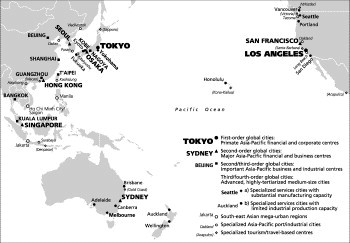

There are also important spatial expressions of developmental convergence or commonality between the nations and regions of the Atlantic-centred core and those of the Pacific Basin. These include processes of advanced urbanization and the emergence of city-region systems which embody aspects both of competition and complementarity, and which feature first order world cities such as New York, London and Paris, within the Atlantic sphere, and Tokyo and Los Angeles situated within the Pacific realm. While these powerful world cities (first described by Hall (1966)) have attracted the greatest attention from scholars and urban policy specialists, there are also globally significant second- and third-tier world cities within each of these dominant zones, including, for the purposes of illustration, Frankfurt, Milan, Chicago and Toronto, situated within the Atlantic zone or ‘old core’, and, within the ‘new core’ of the Pacific, Hong Kong, Osaka, Taipei, Sydney and Seattle. The process of urbanization is of course at a more mature stage within the Atlantic core, due in large part to earlier industrialization, and a longer record of tertiarization, but there is now a well-developed pattern of higher-echelon global cities within the Asia-Pacific (Rimmer, 1986, Preston, 1998) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Global cities with the Asia-Pacific.

These cities are centres of advanced industrial and services production, and are linked by capital flows, technology transfer, transportation and communication networks, and patterns of cultural exchange and diffusion, typifying aspects of international and global co-dependency. The second-order world cities achieve a level of global reach via the presence of certain specialized industry groups, propulsive firms, or influential international institutions, and thus comprise essential elements of the global economy. Global city status is conventionally associated with comparative concentrations of intermediate banking and finance, headquarters of MNCs, ‘producer’ services (Stanback et al., 1981) and international gateway functions. However, increasingly global city status encompasses other suites of specialized service industries, including design, knowledge, and technology-based activities, in part reflecting Scott's thesis concerning the transformational convergence of culture and urban economic development (Scott, 2000), as well as the competitive advantage of metropolitan cities for creative and informational services (Table 1).

Table 1.

Principal suites of specialized service industries for global city-regions

| I (Suites of specialized service functions) | II (Service industries and institutions) |

|---|---|

| Banking and finance | Commercial, merchant, and investment banks; securities and brokerages; stock exchanges; non-depository financial institutions; insurance and re-insurance; industrial-commercial real estate and property development |

| Corporate control | Head offices of international and global corporations and multi-nationals; ‘propulsive’ corporations and firms |

| Producer services | Specialized, export-capable intermediate service industries and firms; corporate law and accounting firms; management consulting, consulting engineers |

| Gateway roles | Major international airports; major seaports; international telecommunications facilities |

| Capital functions | National capitals; state/province/regional capitals and administration; offices of international agencies |

| Tourism and conventions | International tourism and convention industries; major international fairs and expositions |

| Advanced-technology services | Software developers; IT firms; internet providers; ‘dot.com’ firms |

| Creative services and applied design | Architects; industrial design; graphic artists/design; fashion design; interior design; landscape design |

| Education and knowledge | Major national and international universities and colleges; R&D operations and science parks; major ‘think tanks’ and other research/knowledge-based institutions |

| Culture and heritage | Major museums and galleries; national libraries and archives; culturally defining heritage buildings, sites, and precincts |

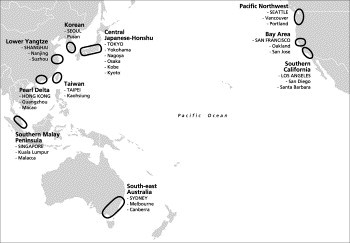

This city-centred growth pattern is complemented by complex and distinctive forms of regional development, which include (1) multi-centred urban growth corridors or ‘megalopolitan’ regions, such as the classic New York–New Jersey conurbation (Gottmann, 1961), and the Randstat urban corridor in the old Atlantic core, and the example of the ‘extended metropolitan regions’ (McGee, 1990) of East Asia and Southeast Asia, such as Jakarta–Bandung, Beijing–Tianjin, and Tokyo–Kawasaki–Yokohama, within the Asia-Pacific sphere; (2) ‘lead regions’ comprised of innovative industry complexes and propulsive firm networks, exemplified by Baden–Württemburg, the Veneto, the Ile de France, and the London–Oxford–Cambridge technology triangle within the old core (Storper and Salais, 1997), and the Kanto Plain, Orange County, and Silicon Valley (Scott, 1986) within the Pacific sphere; and (3) incipient trans-border ‘growth triangles’ (and other geoeconomic constructs), illustrated by the Singapore–Johore–Riau development triangle, and the Cascadia metropolitan bio-region of the Pacific North West, and, in the Atlantic old core, the Transmarche region, and the emerging Baltic development zone which aspires to foster mutually beneficial development in northern Germany, the former Soviet Baltic states of Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania, and Scandinavia. These new and emerging growth territories may exhibit positive spread effects of regional development generally lacking in less advanced zones of the global economy, and suggest possibilities of functional complementarity and reciprocal specialization, as well as the familiar exigencies of competitive advantage.3

In the aggregate, these characteristics—technology-intensive production, high quality economic infrastructure, productive human and social capital, superior external trade mechanisms and capacity, and the distinctive spatial patterns of growth described above —constitute defining aspects of development within the world's dominant economic spheres. These attributes affirm the exalted economic status of the mature Atlantic core and the dynamic Pacific core, define the trajectory of development at the leading edge of change and transformation, and suggest the power of convergence, interdependence, and hierarchy acknowledged as important facets of globalization.

2.1. Developmental contrasts between the Pacific and Atlantic cores

While important commonalities can be discerned, there are fundamental contrasts in the development experiences and transformational vectors of the Atlantic and Pacific spheres, as well as innumerable variations in the circumstances and growth paths of individual nations and regions within each of these dominant, supra-continental realms (see Yeung and Lo, 1976). The inexhaustible differentiation of regional histories, political traditions and structures of governance, culture and geographical and environmental factors are seen to underpin the persistence of variegation and exceptionalism among regions and localities within both the old and new cores. The confluence of exogenous forces, including the rise of MNEs, and increasing market integration and technological diffusion, has imposed some measure of developmental convergence and commonality across international space (as well as increasing disparities within urban social structures), but there are after all limits to the homogenizing effects of globalization, as the recent scholarly development literature attests. Without denying the impressive global sweep of MNEs and speculative capital, it is essential to acknowledge the significance of (largely) localized development influences, such as site and environment, the structures of social networks and civic institutions, and the quality of public policy and regulation.

In an insightful book aimed at ‘reasserting the power of the local’, a number of scholars enrich the discourse on globalization by an elucidation of factors which reaffirm the power of local identity, and which provide some friction to the movement of capital and firms. Storper, notably, asserts the significance of ‘territorialization’ in embedding some specialized forms of economic activity within specific locations, beyond the more generic considerations of urban agglomeration which can bind (especially contact-intensive) firms to central places, such as higher-order service enterprises which cluster within the corporate complex of the central business district (CBD). In this interpretation, a firm or activity is “fully territorialized when its economic viability is rooted in assets (including practices and relations) that are not available in many other places and that cannot be easily or rapidly created in places that lack them” (Storper, 1997: 21). This concept of territorialization can also incorporate the quality of civic institutions and civil society as influences on economic development and socio-economic welfare, as disclosed in Putnam's seminal study of regional and community development in Italy (Putnam et al., 1993). Other important factors of locality that can influence differentiation in patterns of economic growth and development are exemplified by amenity attributes, which may include access to education and learning opportunities, and community levels of tolerance and equity, as well as air and water quality, leisure, and recreational opportunities. Thus, the forces of globalization, as powerful and pervasive as they demonstrably are, may be significantly tempered, mitigated, or renegotiated at regional and local levels.

This more nuanced interpretation of the interactions and tensions between global imperatives and local (or domestic) factors provides a useful backdrop for inquiry into the comparative developmental conditions between the Atlantic and Pacific cores, a task that has assumed greater importance both in the wake of the Asia-Pacific's dynamism over much of the past three decades, as well as the serious downturn that commenced in mid-1997 in many East and Southeast Asian economies. This crisis, which delivered a major check to the continued growth and progress of many of the leading economies of the region, presents a complex set of economic, socio-cultural and political issues and underlying causes that vary widely from place to place, but certainly includes important structural factors (relating to governance, policy, regulation, and financial supervision), as well as more transitory or cyclical attributes (McLeod and Garnaut, 1998). An apparent recovery process can be discerned in some of the Asia-Pacific economies, but the experience is likely to be protracted and wrenching for many, as the (now decade-long) recession in Japan seems to attest. Sustained recovery (and, more pointedly, a shift from growth to development) will require major adjustments to the political structures of Asia-Pacific states, as well as to the governance of corporations and industrial enterprises, and to the supervision and regulation of banks and financial institutions. Both the depth and breadth of this economic downturn (and attendant social and political upheavals), and the quarter century or so of recurrent high growth levels that preceded it, raise questions concerning the contrasting trajectories of development within the mature Atlantic economies and those of the new core of the Pacific Basin, as well as the factors underlying these patterns of differentiation.4

Certainly one of the most salient and defining contrasts in the post-war trajectories of the Atlantic and Pacific spheres concerns the relative status and roles of the secondary (manufacturing) and tertiary (service) sectors, respectively, and the ensembles of policy, market and socio-demographic influences on these distinctive sectoral specializations. Beyond the obvious reality that the leading states of both the Pacific and Atlantic spheres contain advanced industrial production sectors, and are experiencing growth in tertiary activity, it is important to acknowledge that while the growth of services represents a dominant motif of the economic and social reconstruction of western economies and societies, the accelerated growth of manufacturing industry and employment has been the principal story in the rise of the Asia-Pacific economies over the past four decades. Among the mature economies of the OECD, concentrated within the old Atlantic core, this same period has seen a massive contraction of production capacity and labour in basic industries, especially in Fordist mass-production manufacturing, manifested most dramatically by wrenching processes of industrial decline (consisting mostly of outright factory closures but also some measure of locational decentralization) within long-established inner-city industrial precincts of large- and medium-size cities, and consequent losses of employment, income and revenue (Noyelle and Stanback, 1984). New industries characterized by flexible specialization processes and technology-intensive outputs have emerged in ‘lead regions’ and ‘new production spaces’ (Scott, 1988) within the Atlantic core, so aggregate manufacturing output has held up or even increased (by value) in some areas (Coffey, 1996), but in general manufacturing activity has lost ground in relative terms in most OECD regions.

Over the past half-century, services have been essential features of the development of metropolitan cities (Gottmann, 1974). More specifically, intermediate services have emerged as increasingly strategic and propulsive elements of advanced production systems, as observed in successive rounds of industrial restructuring, in new divisions of labour, and in the rise of service-based global cities and new urban service poles (Table 2). At the same time, the post-war period has seen among the most advanced societies the sustained expansion of service industries which (with related shifts in industrial production processes) have profoundly changed the economic base, industrial mix, labour force, land use and physical form of city-regions within the Atlantic zone. Service sector growth has thus constituted a central feature of economic restructuring among advanced nations and regions, with service-type occupations leading employment formation not only in the tertiary and quaternary (or informational) sectors, but also in manufacturing, where the growth of management, clerical, sales and technical workers has exceeded that for direct production workers and operatives in most cases.5

Table 2.

Evolving role of intermediate services in advanced production systems 1950–2000

| I (Administrative functions: ‘Lubricating’effects) | II (Facilitating functions: ‘Productivity’ effects) | III (Strategic functions: ‘Propulsive’ effects) |

| Accounting | Management consulting | Informatics and IT |

| Inventory control | Marketing consulting | Innovation and design |

| Public relations | Consulting engineering | Technology JV specialists |

| Stock exchanges | Commercial and merchant banking | Global financial intermediaries |

| Industrial/commercial real estate (ICI) | International mega-project consortia | |

| 1950s | 1970s | 1990s |

| (A) Shifts in intermediate services with respect to(1) dominant industrial production regime, (2) sourcing arrangements, and (3) employment formation | ||

| (1) Expanding business services within Fordist industrial production modes | (1) Producer services as key to flexible specialization production regimes (Coffey) | (1) Emergence of integrated sevice-technology-production systems |

| (2) Internalized service production | (2) Externalized service production | (2) Globalized service production |

| (3) Professionalization of service occupations | (3) Accelerating divisions of labour; growth of professional, managerial, technical occupations | (3) Emerging international division of production labour; rise of ‘knowledge worker’ and ‘informational society’ (Castells) |

| (B) Context for shifts in intermediate service production | ||

| Sustained periods of high growth and corporate expansion | OPEC shocks - OECD recession; recovery in mid/late 1970s | Collapse of COMECON system; de-regulation of financial and other service industries; GATT and NAFTA regimes |

| US–European economic hegemony | New production spaces within OECD and NICs | Competition for service investment and trade within global markets and urban networks (Daniels) |

| CBD ‘office boom’ in primate cities and large business centres (New York, Chicago, London) | Growth of ‘world cities’ (London, New York, Tokyo) (Friedmann); metropolitan service industry deconcentration strategies | Emerging service poles (Shanghai, Singapore, Fukuoka, Hong Kong, Toulouse, Seattle, Barcelona, Singapore, Vancouver) |

Source: adapted from Hutton (2000).

But these structural consequences of tertiarization extend well beyond the economic dimension, as the sustained expansion of service labour (and concomitant decline in blue-collar workers) within the Atlantic core regions has led in turn to the reformation of urban society, in terms of social class, community and neighbourhood patterns, culture, and political values and preferences, as documented in scholarly treatments of post-industrial society (summarized in Table 3(a)). The tight spatial bonding of specialized, contact-intensive service industries within intricate input–output relations has been instrumental in the reformation of urban structure and land use within the metropolitan core (Gottmann, 1970, Hutton and Ley, 1987). Tertiarization has also generated more comprehensive changes in metropolitan structure, as seen principally in the emergence of specialized service nodes and clusters which dominate the space-economies of advanced city-regions, and also in urban form and the built environment, exemplified in the growth of the central city corporate complex, new districts of services production and consumption on the CBD fringe and inner city (including design and technology-based services), regional office and retail centres, and proto-urban forms which incorporate advanced service industries within ‘edge cities’ (Garreau, 1991)6 (Table 3(b)).

Table 3.

Defining attributes of advanced urban tertiarization

| Attributes | Defining conditions within highly tertiarized cities |

|---|---|

| (a) Urban industrial structure, economic base, employment and class | |

| Sectoral/industrial structure | Tertiary sector larger than secondary sector; service industries growing faster than manufacturing industries both in relative and absolute terms |

| Industrial output | Services share of urban/regional GDP growing faster than manufacturing share |

| Market orientation/production linkages | Intermediate sector services growing faster than final demand services; specialized services and manufacturing co-dependent elements of advanced production systems |

| Urban economic base | Services comprise large and increasing share of urban economic base; significant and growing volume of specialized service exports and trade |

| Employment | >75% of urban employment in service industries |

| Occupational structure | Rapid growth of executives, managers, professionals; emerging social division of service labour favouring knowledge- and technology-based service workers, design, creative and cultural services |

| Urban class structure | Emerging hegemony of ‘new middle class’ (Ley, 1996) of upper-tier service cohorts |

| Urban social morphology | Extensive social upgrading (gentrification) in older inner city neighbourhoods; growth of inner city loft housing and ‘live-work’/‘work-live’ studios; increasing social displacement and inter-group tensions |

| (b) Urban spatial structure, space-economy, form, image and identity | |

| Urban/metropolitan structure | Service industries dominant elements of urban core and (established or incipient) metropolitan sub-centres |

| Urban space-economy | Specialized service clusters and corridors dominant features of urban/metropolitan space-economy (CBD corporate complex, seaports and airports, distribution centres, retail centres, higher education institutions, government and public administration, business parks, R&D parks] |

| Inner city landscapes | New and emerging precincts of specialized services: applied design, creative and cultural services; internet providers and ‘dot.com’ firms; cultural centres; higher education; professional sports and entertainment; public recreation; live-work studios and new artist/artisan neighbourhoods |

| Urban form | Mix of modernist–post-modernist urban forms: high-rise officeprecincts in CBD and metro sub-centres, as well as new services domiciled in ‘reconstructed’ services production and consumption landscapes within inner city and inner suburbs; ‘edge cities’ and proto-urban forms on the metropolitan periphery |

| Infrastructure | Derived demand for transportation and other infrastructure associated with urban tertiarization |

| Identity | Post-industrialism; post-modernity |

| Image | ‘Global’ or ‘world’ city (Hall, Friedmann, Sassen); ‘Informational city/society’ (Castells); ‘Transactional city’ (Gottmann) |

2.2. The primacy of the industrialization paradigm within the Asia-Pacific

While tertiarization stands as the definitive and most consequential feature of economic growth and social change among Western or Atlantic nations and regions over the post-war period, industrialization has represented the principal development modality for much of the Asia-Pacific since the 1950s and 1960s.7 (Although there have been to be sure important shifts in agriculture and other forms of primary and staple production in many Pacific nations.) There is of course considerable variation in the temporal sequencing, specific industry emphasis, scale and stage of manufacturing growth among individual nations (and even among regions and sub-regions), but accelerated industrialization, supported in most cases by state policies and programmes, has been central to the expansion of every high growth Asian-Pacific state (Douglass, 1994), including (1) the Japanese ascendancy, seen in the industrial development of the Japanese archipelago (especially within the principal conurbations of Honshu but also including urban centres in Kyushu and Hokkaido) over much of the present century, with accelerated development of production in industrial and consumer goods from the 1950s, including the expansion of global-scale industrial conglomerates and MNCs; (2) the origins of takeoff growth among the Newly Industrializing Countries (NICs), with accelerated industrialization initiated in Taiwan and Hong Kong in the 1950s, and Singapore and South Korea about a decade later (McGee and Lin, 1993); (3) the later emergence of the ‘threshold’ or ‘near’ NICs, notably Malaysia and Thailand, which retain important bases of agriculture and staple production outside the principal metropolitan zones, but which have experienced substantial manufacturing growth over the past two decades; (4) the tumultuous growth and transformation of China, dating from the ideologically impelled industrialization programme enunciated in the series of 5-year economic plans commencing in the period 1953–57, to the industrial stimulus generated by the economic liberalization policies launched in 1978, and then to the more recent expansion of advanced manufacturing in the Lower Yangtze, Pearl River Delta, and certain other coastal regions; (5) the larger role played by industrial development in the transition of other populous agrarian nations, notably Indonesia and the Philippines; and (6) the current economic restructuring programme in Vietnam, associated with the ‘doi moi’ policy of economic and social renovation. In addition to these important examples, industrialization also represents a goal (or ideal) of lagging states within the region, such as Laos, Burma and North Korea, although the realization of these industrial aspirations has been seriously impeded by a prejudicial mélange of factors including war, flawed development models, governmental corruption and administrative incompetence, lack of capital and other resources, and isolation.

These national industrialization programmes and trajectories also featured important urban and regional dimensions. By the 1970s, the Asia-Pacific sphere included a number of world-scale industrial metropoles, such as Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, Seoul, Taipei, Hong Kong and Shanghai, while by the 1980s manufacturing emerged as an important feature of the metropolitan space-economies of Southeast Asian primate cities, including Bangkok, Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur, and Manila (Douglass, 1989). Beyond these large-scale urban industrial complexes, manufacturing activity increased within the metropolitan periphery, exurban areas, and even rural zones, for instance in the Lower Yangtze region, within the Chinese special enterprise zones (SEZs), within designated receptor areas (such as Penang) for Japanese foreign direct investment (FDI), and within desakota areas of East and Southeast Asia, proliferating the spatial milieux for industrial production in the region.

Even in Pacific America, within which urban tertiarization processes are generally advanced, some city-regions have exhibited greater buoyancy in manufacturing than many of the older industrial cities of the Great Lakes region and Eastern Seaboard, within the broadly defined Atlantic core. Over the past two decades, Los Angeles, the San Francisco Bay area, Seattle and even Vancouver have experienced significant growth in advanced manufacturing such as aerospace and electronics (and in some basic production industries as well, such as garment production) within their regional territories, in contrast to the record of industrial decline in many other North American metropolitan areas, although to be sure they have also experienced high growth in service industries, and contractions in some traditional industries. At the end of the 20th century, then, industrialization represented the dominant trajectory for many states and regions within the Asia-Pacific, constituted a significant aspect of growth (together with specialized services) in some of the more advanced economies of the Pacific realm, and remained an aspiration of less-developed, agrarian and staple-dominated countries in the region. These industrialization trajectories will continue to be highly influential in the development of Asia-Pacific city-regions in the new century, but it is equally clear that service industries will emerge as increasingly significant features of urban growth and change, a theme we will explore in the following chapters.

Chapter 3. Contours of urban tertiarization within the Pacific Basin

To date there has been relatively little scholarly attention paid to the development of service industries and employment within the Asia-Pacific, with the notable exception of case studies of cities within which services (especially advanced or ‘higher-order’ services) are playing significant roles (Taylor and Kwok, 1989), and specialist studies of banking, finance and investment, and transportation and communications. The research emphasis has tended to be on multinational service corporations and international trade in services (Waelbroeck et al., 1985, Thrift, 1986, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 1990, Sieh-Lee, 1992, Lasserre and Redding, 1995), rather than on services development and associated issues for cities and city-regions. This situation reflects, to some extent, the pervasive influence of industrialization as a development paradigm within much of the Pacific realm, emphasizing the primacy of manufacturing and industrial production within the growth trajectories of many Asia-Pacific states, regions and societies.8 The hegemony of the industrialization paradigm has created a kind of shadow effect within the scholarly literature on the economic development of the Pacific Basin, within which services are customarily treated as elements of the traditional urban retail or commercial sector, as essentially ancillary activities which can be effectively subsumed within industrialization processes and systems, or as special, almost aberrant features of exceptional cases such as Hong Kong and Singapore. Indeed, many of the region's leading service industries and corporations (notably banks, trading companies, and ocean freight lines) were established to facilitate manufacturing growth and the expansion of trade in goods, thus comprising essential features of the Asia-Pacific's industrialization experience. Moreover, service industries, including modern, advanced services, are now sufficiently well-represented in a broad sampling of national and regional jurisdictions, and are now so increasingly central to the economic and social transformation of Pacific cities, that a more incisive investigation of services growth trends and associated impacts is clearly merited (O'Connor, 1998).

3.1. The growth of intermediate services

The centrepieces of urban service sectors within the Asia-Pacific are of course the large national and multinational service industry corporations, including the major banks and financial institutions (including brokerages and securities companies), trading houses, property firms, integrated construction and development corporations, and the leading airlines and hotel groups. These are, as is well known, highly concentrated within the region's first- and second-tier global cities, especially Tokyo, Osaka, Seoul, Taipei, Hong Kong, Singapore, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Sydney. Many of these financial corporations and other large service enterprises have become extensively globalized, enhancing the status of the cities within which they are domiciled; but a significant proportion of these corporations have been seriously damaged by the events of 1997 and after, and there have already been a number of major bankruptcies, with, no doubt, more to follow. The corporate power of cities within the Asia-Pacific is therefore pervasive, but by no means immutable.

At a smaller scale, we can identify the full range of intermediate or producer services which, as in the mature economies of the Atlantic sphere, typically include corporate legal firms and accountancies, management consulting firms, public relations and personnel companies, technical service operations, as well as planning and architectural firms which cater wholly or in part to the corporate sector. At the vanguard of growth and change there are also an expanding number of firms in the computer software and knowledge industry groups that are so crucial to the progress of advanced, information-based economies. In general, however, this intermediate services subsector (comprised mainly of small- and medium-size firms) is somewhat less well-developed in Asia than is the case among the leading regional and national economies of Europe and North America, where the producer services are seen as essential to the efficient operation of flexible production regimes, and have constituted the most dynamic elements of these economies and labour forces over the past two decades. This disparity is reflected in the large balance of trade deficits in specialized services incurred by most Pacific Asian nations (Daniels and O'Connor, 2000).

We can provisionally attribute the (relatively) less developed nature of intermediate services within the Asia-Pacific to a number of factors and conditions, including the perhaps obvious observation that services are generally at a less mature stage than among the more advanced Atlantic core economies. However, there are also important structural factors as well. These include, notably, contrasts in the regulatory conditions and legal and contractual regimes between countries, which impose different kinds and levels of requirements upon firms domiciled within these jurisdictions. Within many of the Western societies these regulatory and legal regimes have become exceedingly complex and demanding, giving rise to specialized intermediate service firms which provide expert advice to corporations on a subcontracting basis, as the demand arises. Within the Asian realm, as we have already noted, many of these specialized service inputs are generated either internally within the corporation, as is the case with some of the larger Korean and Japanese conglomerates; or, as is the practice in many firms in China and Southeast Asia, are supplied by a network of advisors defined by kinship and social relations. Moreover, there has been a substantial (if spatially and temporally uneven) growth of producer services within the Asia-Pacific, reflecting “the wide socio-cultural heterogeneity in this region and the distance between trade centres” (Ho, 1998: 179).

At the leading edge of change among a growing number of Asia-Pacific societies, the implications of service industry growth may at least selectively reflect the experience of the mature economies of the Atlantic-centred core, within which specialized service industries (1) represent both agents and outcomes of economic restructuring, as well as leading elements of overall urban and regional transformation; (2) constitute (with technology and manufacturing) co-dependent elements of advanced, flexible production systems; (3) are associated with important, and in some cases defining, new divisions of labour and social class reformation; (4) reflect, in part, increasing income levels and consumption rates within host societies; and (5) have become significant elements of inter-regional and international trade flows, reflecting inter alia externalization tendencies and aspects of competitive advantage for specialized services production, export, and trade.

As observed among the mature industrial (or post-industrial) societies of the Atlantic sphere, too, service industries within the Asia-Pacific tend not to be distributed evenly across national territories, but are instead concentrated within urban regions, reflecting the spatial association between consumer services and their residentiary markets, and the even more centralized patterns of highly agglomerative intermediate (or producer) services. There is also a tendency toward greater levels of specialization in services production among larger cities, although there are to be sure some notable exceptions to this. This correlation between tertiarization levels, growth rates and degrees of specialization is of course most easily observed among the region's major corporate centres, such as Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Singapore, but the familiar spatial manifestations of service industry growth (CBDs, corporate complexes, commercial strips and nodes, and the like) are features of a growing roster of Asia-Pacific city-regions, although their specific form may be locally distinctive. The study of specialized service industries within the Asia-Pacific, then, as in the Atlantic sphere, necessarily implies an urban emphasis.

These important commonalities notwithstanding, even at the most generalized level of analysis we can readily identify some defining distinctions between current services growth rates, development patterns and interdependencies within the new core of the Asia-Pacific, and those observed within the Atlantic-centred old core. As in other facets of urban development, it is essential to achieve an appreciation of signifying contrasts in urbanization experiences in the Asia-Pacific, as distinct from the patterns of urban development within the Atlantic core (Lin, 1994). These contrasts include the following:

-

1.

Generally higher growth rates of service industries and employment among Asia-Pacific nations and city-regions over the past decade and a half, reflecting more incipient stages of tertiarization in many Asian jurisdictions and, broadly, more buoyant economic conditions over the past two decades or so. By way of contrast, service growth in Europe has been (as Daniels notes) slow or even stagnant (Daniels, 1993). (It must, however, be acknowledged that the depressed condition of certain Asian currencies and financial markets are diminishing growth expectations in financial and service sectors among certain business centres over the short- to medium-term, and ensuing political instability and social unrest will almost inevitably exacerbate those impacts. Moreover, urban service sector growth rates will inevitably slow among advanced cities with high existing levels of services labour, including Singapore, Hong Kong, and Japanese cities).

-

2.

Highly differentiated trajectories of tertiarization and economic restructuring among Asia-Pacific city-regions, which represent in many cases significant departures from the more linear patterns of service industry growth common to the old Atlantic-centred core. These contrasting tertiarization trends and processes are in part a consequence of the widely varying stages of overall development among specific national and regional jurisdictions, but are also associated with important (and in some cases decisive) policy factors and local development strategies.

-

3.

The diversity of services-production linkage patterns among Asia-Pacific economies, which to some extent may follow the services externalization and subcontracting processes widely documented among European and North American firms, but are also exemplified in other respects by the distinctive nature of industrial organization in ‘lead’ Asian economies in which large integrated corporations (keiretsu in Japan, the chaebol in South Korea) maintain internalized service supply; by the intricate entrepreneurial networks based on kinship relationships in parts of East and Southeast Asia (Hsing, 1995); and by the intimate spatial linkages between industrial production and service providers observed in exurban or countryside production regimes in certain regions of China (Marton, 1996).

-

4.

Variation in the reconfiguration of metropolitan space-economies to accommodate the introduction of new, specialized service industry nodes and clusters, which follow to some extent the locational tendencies of services in advanced economies and city-regions; while at the same time exhibiting persistent spatial patterns derived from more traditional systems of urban and regional economic development, as exemplified in the desakota areas of Southeast Asia and Japan, and, at a smaller scale, the intimate juxtaposition of advanced and informal service activities in central areas of developing societies (Leaf, 1996). In the most advanced cases, new spatial patterns of specialized services production include clusters of design, creative services, and advanced-technology service industries within reconstructed inner city precincts.

-

5.

Distinctive divisions of labour within urban service industries, which may appear to mimic the Western model at the apex of the occupational hierarchy (i.e., the growth of managers, professionals, knowledge-based and advanced-technology workers), but also display substantial variation, derived in large part from localized culture, class structures and traditions, the pre-existing base of service workers, and region-based entrepreneurial or mercantile cultures.

To these broad points of contrast in the tertiarization experiences of the Asia-Pacific and Atlantic spheres, it is essential to highlight important differences in policy approaches and roles. Within the Asia-Pacific, we observe a spectrum of (sometimes quite assertive and even grandiose) developmental policies and programmes designed wholly or in part to promote the growth of specialized service industries. These include the highly dirigiste approaches of Japan (Shapira et al., 1994) and Singapore (Ho, 1994), within which central governments have assigned leading roles to advanced service industries in support of urban and national economic transformation, and enhanced roles for service industries in local economic development strategies and policies. In contrast, public policy approaches toward services among Western societies have tended to emphasize regulation, including zoning, development control, and growth management, in addition to mostly episodic experiments with developmental policies, and only very exceptional attempts to undertake service industry ‘megaprojects’ on the heroic scale of numerous Asian cities.9

3.2. Five categories of tertiarization impacts

Although there are profound differences in stages and levels of tertiarization among Asia-Pacific city-regions, as we shall shortly see, the implications of urban service industry growth can be structured within five broad categories: (1) a set of essentially propulsive and transformational impacts, within which services (especially advanced intermediate and knowledge-based service industries and institutions) are assigned leading roles in urban, regional and even national development; (2) the (direct and indirect) impact of services on the internal restructuring and reconfiguration of the city-region, including regional structure, the metropolitan space-economy, and built form; (3) services and the reformation of urban class and the city's social morphology (or ecology); (4) implications of rapid tertiarization for the experiences of everyday life; and (5) the role of services in the transformation of the city's image and identity. It must be emphasized that these are by no means neatly compartmentalized, discrete categories of consequence, however, as there are innumerable interactions and interdependencies between and among them.

First, rapid tertiarization may have the potential to significantly accelerate the processes of urban growth and change, and to quite fundamentally modify basic urban economic functions or vocations, as reflected in the recomposition of the metropolitan industrial structure, economic base, and regional GDP. At one level, this process evokes the idea of post-industrialism, which positions service industries and occupations as ascendant features of the urban economy in a context of (relative or even absolute) contractions in basic manufacturing. However, in the Asia-Pacific setting the growth of specialized services can be seen as a concomitant element of advanced production systems, national modernization programmes, and globalization strategies of central and regional governments. These strategic aspirations are by no means fully realized, but they do underscore the importance of advanced services to the future development of the region.

As is well known, tertiarization within many Asia-Pacific city-regions is impelled both by market and policy factors. This latter tendency is particularly marked in the region, as we can instance numerous examples of assertive public policy efforts both at central and local government and administrative levels designed to accelerate tertiarization (and/or deploy tertiarization as an instrument of broader economic and socio-economic transformation). Examples of the deployment of policies for services in the interests of supporting or promoting transformational change include (a) synergies between national economic liberalization policies and local development strategies which have accelerated tertiarization processes (including advanced services) among designated Chinese city-regions, (b) intersections between national industrial policies and urban economic programmes which have supported specialized service functions among Japanese metropolitan cities, (c) ensembles of national development programmes and regulatory adjustments designed to enhance the growth of advanced, export-oriented services, as in the case of Singapore since the mid-1980s, (d) central government support for strategic service industries as instruments of national development, accompanied by complementary local land use initiatives, as in the case of finance, producer services and information technology in Malaysia, and (e) the more episodic (or less committed) support for service industries within (often somewhat schizophrenic) clusters of local development and growth management plans in Sydney, Melbourne, Seattle, San Francisco, Vancouver, among other cities.10

The second category of urban tertiarization impacts concerns the role of services in change within the internal form and structure of the metropolis or city-region, and reflects the profound and comprehensive impacts of service industry development on the space-economy of the contemporary city. The internal reordering of metropolitan space associated with rapid service industry growth incorporates processes which are multi-faceted and interdependent: demand for services generates growth among service industries and firms to create a new sectoral mix within the city's economic base, and new patterns of services production and consumption as observed in the emergence of high-rise office complexes, secondary business centres, specialized service clusters (for example tertiary education and medical complexes), and new retail landscapes. These developments have visibly reconstructed urban structure and form in many American cities, but in some European cities have been situated more carefully within older districts, creating a more subtle and complex urban form, while in Asia (for example in Shanghai and Osaka), preservation has been subordinated to the imperatives of accelerated restructuring, and has been in policy terms an afterthought at best.11

While market forces have constituted agents of urban respatialization, public authorities have deployed services as instruments of internal metropolitan reconfiguration within the Asia-Pacific, as in (a) the construction of new financial and corporate complexes, both to accelerate economic restructuring at the local level, and to support national modernization goals (as exemplified by the massive Pudong project across the Huangpu River from the established central district of Shanghai) (Yeh, 1996), (b) the development of modern commercial and telecommunications infrastructure to support future world city aspirations (as seen in Kuala Lumpur), (c) the promotion of specialized financial and producer services in established CBDs and designated subcentres to support world city status, and to maximize regional competitive advantage (with Singapore presenting a vivid example), (d) the reclamation of land resources for accommodating the expansion of spatially or topographically constrained CBDs (Hong Kong), and (e) the development of commercial and business mega-projects to diversify local economies, advance international business and financial relationships, and compete more effectively against other (often larger) centres within regional settings (as is the case with the Minato Mirai 21 project in Yokohama) (Hutton, 1997). More generically, public authorities also respond to infrastructure demand (for example airports and transit systems) derived from growth in services industries and activities (Daniels, 1991).

The growth of service industries and occupations within Asia-Pacific city-regions also has important social implications, representing a third major set of urban tertiarization impacts. Here, the growth of (especially advanced) service industries and related occupational cohorts generates an increasingly tertiarized labour force, which Daniel Bell described as a pre-condition for the emergence of a post-industrial society, over a quarter century ago (Bell, 1973): a contested idea, to be sure (Gershuny, 1978), but a seminal and prescient contribution in many ways. Within the highly tertiarized city, the growth of specialized services leads to significant socio-spatial effects, including the familiar pattern of social upgrading within inner city neighbourhoods, and the formation of new suburban communities comprised largely of service workers, but also the recent emergence of a ‘new middle class’ of higher-echelon service labour (Ley, 1996). The rise of this new middle class of elite service workers (professionals, executives and managers, entrepreneurs and creative services occupations) as a presence in the inner city, a larger process than earlier, more incremental experiences of gentrification, comprises individuals who view the metropolitan core as a place to work, live, and recreate, leading to the transformation of the central city with respect to structure, land use, form, and lifestyles. There are also broader cultural connotations associated with the new middle class, as seen in shifts in tastes, values, behaviours, and even political affiliation. This new middle class enjoys a hegemonic status within the most highly tertiarized cities in the region, such as Vancouver, Seattle, San Francisco, and Sydney, and comprises the ascendant social cohort within Singapore, Tokyo, and Hong Kong, but is also observed as a growing presence (with some local variation in specific features) within the central districts of Seoul, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Kuala Lumpur, among other cities.

The fourth set of impacts of service industry growth within cities of the Asia-Pacific concerns changes at the micro-level, what Braudel termed the ‘structures of everyday life’ (Braudel, 1982). Although much of the scholarly analysis of tertiarization has emphasized change within the three strategic categories described earlier, a more nuanced appreciation of the more intensely localized implications of growth in services is essential to attaining an appropriately rounded profile of the process. These include, for the purposes of illustration, the impact of service industries and the growth of service occupations on the quality of working life, and on localized displacement and dislocation at the neighbourhood and household levels (Chua, 1989, Chua, 1991), especially within a context of industrial decline or restructuring. There is considerable potential for research on the important gender aspects of tertiarization, which may include the tendency for over-representation of females within many service occupations and industries. Within the highly tertiarized societies of the old Atlantic core, the past several decades have seen both the impressive progress of women within some of the credentialized service occupations, for example in law, accountancy, and planning, but also a more discouraging tendency for women to congregate in more menial, poorly paid and distinctly marginalized positions.

There are also important linkages between the growth of service industries in Asia-Pacific cities and international migration. Australian scholars have suggested that immigration can enhance the ‘productive diversity’ of economies, and more specifically that skilled immigrant professionals can support urban services exports, for example in sharing or transferring within the firm knowledge about overseas markets (Aislabee et al., 1994). Lin observes that characteristics of mobility, flexibility and entrepreneurial skills are defining attributes of Hong Kong migrants (Lin, 2000: 13), enhancing their attractiveness to receiving urban societies and business communities. In certain cities, recent immigrants are over-represented both within entrepreneurial and management occupations, but also among more menial service occupations; this is especially the case in large global cities (Sassen, 1991). Again, as in other facets of tertiarization, we can discern within Asian labour markets some powerful resonances of trends initially observed in mature cities of the Atlantic core, but there are also quite distinctive, persistent traditional socio-cultural contexts to consider.

The importance of maintaining a perspective on the more localized implications of tertiarization also acknowledges the reality that the expansion of service industries by no means involves just the formal business, professional and managerial activities that have led growth among the Western urban economies, but also the full range of neighbourhood shops and markets, casual restaurants and bars, and personal and retail services (to say nothing of other service establishments that may operate on, or even over, the margins of legality and social acceptance). In many Asian cities, these smaller scale service operations may be viewed as an extension of the traditional population of informal service workers (itself a contested term), service activities which occupy the urban interstices between the more formal corporate business and retail structures. These can be seen as persistent features of the central city, not only among the mega-cities of Southeast Asia, such as Bangkok and Jakarta, but also within the downtown spaces of modern world cities such as Tokyo. They are not simply residual activities, but essential, if often undervalued, operations that support the more formal service economy in 100 different ways within the metropolitan core, including the provision of food and beverages (Yasmeen, 1992). These small-scale, low-return service firms survive by virtue of entrepreneurship, reliability, thrift, and knowledge of where the commercial niches exist in the modern city, and they contribute to the vitality and identity of the urban place.

A final aspect of urban transformation associated with tertiarization is derived from an accumulation of the changes described earlier—economic, social, cultural, physical, and spatial—and is commonly articulated as a metamorphosis of the city's character, as perceived by citizens (constructed as ‘identity’) or as reconstructed by government and corporate entities and external agencies (‘image’). The perceived image of a city can be substantially altered by comprehensive processes of tertiarization, as seen in the repositioning of Singapore and Hong Kong as post-industrial, specialized service centres, although usage of decidedly obsolete nomenclature such as ‘newly industrializing economies’ is surprisingly persistent, as are outdated tropes like ‘little dragons’ or ‘little tigers’ (Cartier, 1999).12 In some cases national governments have supported specialized service industry projects as quite deliberate instruments of urban re-imaging, as seen in the creation of international banking and producer services in the Pudong development in Shanghai, and in the construction of the Petronas Towers in the central area of Kuala Lumpur. These initiatives are designed in part to underscore a commitment to modernity, and by extension to symbolize national economic progress and aspirations to global status and engagement, but also to supplant traditional (or, more pejoratively, ‘backward’) industries and related social groups. These more grandiose visions can be contested, especially where the elite beneficiaries of advanced service industry growth (for example professionals and managers in financial and business services, as well as cronies of rulers and oligarchs) represent a particularly visible and privileged expression of dichotomous ‘development’ as set against the condition of the urban masses in places like Jakarta and Manila.

The issue of urban identity may also be deeply problematic, as the rapid growth of services elites within Asian-Pacific cities can presage decisive shifts in power relations (political as well as economic) within the urban community. In some cases the ascendancy of upper-tier service workers represents a new socio-economic and socio-political hegemony, implying a coincident subordination of traditional industrial-sector cohorts, as well as an exacerbation of income disparities. As in other aspects of urban tertiarization within the Asia-Pacific, contrasts in scale and stages of development are significant, as are tendencies toward exceptionalism when case studies are subjected to closer analysis. Thus, Baum concluded that the sustained growth of specialized service industries, advanced-technology activities and related occupations in Singapore, coupled with comprehensive public housing programmes and education investments, has resulted in a predominantly professionalized (as opposed to polarized) occupational and social structure within the city-state (Baum, 1999). In Hong Kong, where specialized services have also driven urban growth and socio-economic change (Kwok, 1996), the post-colonial record since 1997 includes growing poverty (about 600 000 residents earn less than $600 per month), attributable in some part to the inadequacies of the secondary school system, a situation which one legislator fears may lead to ‘serious social instability’ (Lee Cheuk-yan, quoted in Far Eastern Economic Review: 26 October 2000). At a larger scale, a combination of market liberalization and selective tertiarization in certain Chinese cities, with attendant political and bureaucratic corruption, has generated income polarization rates approaching or even exceeding the American level. This striving for new urban identities in the Chinese case, with its repressed tensions and conflicts, can be seen in the Shanghai government's preference for ‘high class’ individuals (well-educated, with the right attitudes, outlooks and professional profiles) for the glittering new towers of the Pudong project (Halliday, 1995), a far cry indeed from the earlier Communist exaltation of the urban industrial worker and fraternal colleagues in the PLA and in rural peasant communes.

We can also discern highly localized intersections of globalization and tertiarization in the reconstruction of identity at the district level. The proliferation of transnational retail and food services within commercial complexes is of course a ubiquitous phenomenon, as observed in places like Shinkjuku and Shibuya stations (and commercial subcentres) in Tokyo. In Hong Kong, the incursion of service industry commuters in the New Territories has transformed the social identity of certain of the post-war industrial communities, as seen in the transformation of Tsuen Wan from ‘Hakka enclave’ to ‘post-industrial city’ (Johnson, n.d.). In the case of Singapore, the last decade has seen the demise of the Kampung Kopi-tiam (informal eating places, serving authentic local fare) as a result of relentless modernization (Chua, 1995), and the almost total disappearance of traditional rural life, while other local retail and shopping districts have been subject to the reformation of identity associated with the tastes and behavioural preferences of affluent expatriate populations. Chang deploys the term ‘expatriatization’ to describe a “spatial transformation in which land use increasingly reflects an expatriate bias”, as typified in Holland Village, a local commercial centre within an affluent residential district of Singapore, but one which “reflects the influence and influx of global cultures” (Chang, 1995:157).

In the most highly tertiarized cities within the Asia-Pacific, exemplified by San Francisco, Seattle, Vancouver, Sydney and Singapore, a distinctive urban profile associated with dominant service industries and occupations within the financial and producer services now incorporates a more recent overlay of technology specialists, notably internet providers, software developers, and the so-called ‘dot.com’ firms. Many of these firms have been concentrated within “new service production landscapes” within or proximate to the central area, exemplified by ‘Silicon Alley’ and Telok Ayer in Singapore, Yaletown in Vancouver, Belltown in Seattle, and the northeast Mission and South Park districts of San Francisco (Hutton, 2000). These technology-based service firms (which also include graphic designers, who exemplify the production synergies of technology and culture in applied design) typically exhibit employment structures dominated by young entrepreneurs and ‘techies’, with distinctive skills and lifestyles, underscoring both the new social divisions of labour in the urban service sector, and the highly volatile nature of urban identity in the post-modern, globalized metropolitan order. Over the last 2 years, the number of these technology-intensive firms within inner city production districts has contracted significantly, as part of the crash of the dot.coms. However, new survey research has disclosed the emergence of ‘hybridized’ firms combining creativity and technology toward the production of high-value goods and services, signifying a new phase of development within the metropolitan core of advanced societies (Hutton, 2003). These trends therefore demonstrate both the volatile nature of recent phases of service industry development, as evidenced by the accelerated processes of transition and succession, as well as the distinctive role of the inner city as site of innovation.

Chapter 4. Stages of urban service industry development within the Asia-Pacific

The preceding narrative described important distinctions in the broader tertiarization experiences as observed within the old Atlantic core and the new core of the Pacific realm. At the same time, there are also quite profound differences in stages or levels of service industry development among (and within) Asia-Pacific nations, just as there are important contrasts in levels and rates of industrialization.

The construction of typologies of urban tertiarization among Asia-Pacific city-regions is hampered by data constraints and conceptual problems, and more recently by the short-term impacts of the crisis of currencies and financial markets of 1997 and afterwards. Although this crisis was seen to depress prospects for the Asia-Pacific generally, the impacts have been spatially quite uneven, and as the fiscal-economic malaise spread within the regions of the Asia-Pacific, and within social and political domains, it is by no means beyond the realm of possibility that the medium- to long-term outlook for certain urban centres has been seriously compromised. Thus, to the overall perception of dynamism among the urban service sectors and industries of the Pacific region, we must add considerable uncertainty.

There is also a clear need at the outset to acknowledge the increasing complexity of overall urban development patterns, within which (we are arguing in this paper) service industries are increasingly playing larger roles. To illustrate, Terry McGee, in a retrospective paper on his concept of ‘The Southeast Asian City’ published in 1967 following years of extensive fieldwork, observed that “while urbanization levels will continue to rise there will be much differentiation between countries which will make the construction of any one model of the Southeast Asian city impossible” (McGee, 2000:10). In this interpretation, models (or typologies) cannot reasonably function as templates of “supposedly universalizing tendencies” (McGee, 2000:10), but rather should reflect the importance of specificity and exceptionalism in urban development experiences.