Abstract

Currently, the incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) is increasing across the world. The cancer stroma exerts an impact on the spread, invasion and chemoresistance of CRC. The tumor microenvironment involves a complex interaction between cancer cells and stromal cells, for example, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs). CAFs can promote neoplastic angiogenesis and tumor development in CRC. Mounting evidence suggests that many miRNAs are overexpressed (miR-21, miR-329, miR-181a, miR-199a, miR-382 and miR-215) in CRC CAFs, and these miRNAs can influence the spread, invasiveness and chemoresistance in neighboring tumor cells via paracrine signaling. Herein, we summarize the pathogenic roles of miRNAs and CAFs in CRC. Moreover, for first time, we highlight the miRNAs derived from CRC-associated CAFs and their roles in CRC pathogenesis.

Keywords: : cancer-associated fibroblasts, colorectal cancer, exosomes, metastasis, miRNAs, normal fibroblasts, oncogenes, tumor-suppressor genes

In the past few years, the tumor microenvironment has come into sharper focus as a determinant of the clinical prognosis and the response to treatment (especially radiotherapy and chemotherapy) for many types of cancer. The dynamic relationship between a progressing tumor and the neighboring host tissue is becoming more widely understood. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are often a prominent component of the tumor stroma. However, still not much is understood about the ways in which cancer cells convert normal fibroblasts (NFs) into CAFs, or about the cell-to-cell communications taking place between CAFs and cancer cells. These relevant interactions are important to understand different aspects of cancer behavior, and for predicting the emergence of resistance to therapy [1]. As one example, CAFs are able to stimulate tumorigenesis, hasten the development of an invasive phenotype and promote cancer metastasis. On the other hand, NFs are thought to hinder tumor development [2]. CAF activation is a key event in the synthesis and secretion of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, leading to ECM remodeling and increasing the invasiveness of cancer cells [3]. The resulting desmoplasia is not only produced by CAFs but also by neighboring stellate cells, which are also thought to be involved in the aggressive tumor phenotype.

Despite the widespread acceptance of the role of deregulation of miRNAs within human cancers, the influence of miRNA expression and function on the interaction between CAFs and cancer cells has not yet been fully clarified. Growing evidence suggests that miRNAs contribute to the conversion of NFs into CAFs and vice versa. miRNAs secreted from CAFs may influence numerous traits of cancer cells. Recent results imply that cross-talk exists between cancer cells and CAFs, and this may play a role in enhanced tumor aggressiveness [4].

miRNAs are small noncoding RNA molecules that can carry out negative regulation of gene expression at the post-transcriptional stage. The effects of miRNAs on the expression of target genes, includes processes such as, cell differentiation, growth, adhesion, spreading, migration and cell–cell communication, in addition to other functions. It is thought that miRNAs may be able to program somatic cells to transform into pluripotent stem cells [5]. miRNAs mostly occur in clusters. A cluster is a set of two, three or more miRNAs, which are transcribed from physically adjacent miRNA genes. miRNA genes can be found either in protein-coding or noncoding regions of transcription units (TUs). miRNAs in a cluster are transcribed in the same orientation, and are not separated by a TU or an miRNA in the opposite orientation. Clustering seems to play a key role in the evolutionary proliferation of miRNA genes across the human genome, and several clusters show substantial evolutionary conservation, suggesting that miRNA clustering is important for their biological effect [6–8]. In the present review, we summarize the pathogenic roles of miRNAs and CAFs in colorectal cancer (CRC). Moreover, for first time, we highlight how various miRNAs and CAFs can combine together to influence CRC pathogenesis.

miRNA biogenesis

miRNAs consist of a set of short noncoding RNAs that regulate post-transcriptional gene silencing. miRNAs were initially documented in 1993 in Caenorhabditis elegans [9]. However, a broad appreciation of the function of miRNAs in cell biology, did not take place until 2001 [10,11]. Since 2001, thousands of miRNAs have been described occurring in a wide range of different species [11]. The approximately 22-nucleotide miRNA generally binds to the 3′-UTR (untranslated region) of their target mRNAs and repress protein production by destabilizing the mRNA and preventing translation [12].

About 30% of miRNAs arise from protein-coding gene introns, while the majority of miRNAs come from dedicated miRNA gene loci. miRNAs are transcribed via Pol II into primary-miRNAs (pri-miRNA), which are then cleaved in the nucleus by the enzymes DROSHA/DGCR8. DROSHA is a double-stranded RNase III enzyme along with its integral cofactor, DGCR8 [13]. The hairpin structure formed by this cleavage is referred to as a pre-miRNA, which is an approximately 60–70-nucleotide hairpin-shaped molecule [14]. This cleavage occurs at the ssRNA–stem junction in addition to part of the terminal loop area. In particular, cleavage of dsRNA at approximately 11 bp from the junction with flanking ssRNA creates hairpin-shaped pre-miRNAs with an overhang at the 3′ end of either one nucleotide (group II miRNAs) or two nucleotides (group I miRNAs) [15,16]. The pre-miRNA is exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm via XPO5 and then further cleaved by DICER1, which is an RNase III enzyme operating from the 5′ and 3′ ends of the pre-miRNA resulting in a mature approximately 22-nucleotide miRNA duplex with the hairpin removed [14,17–19]. DICER1 binds to TARBP2 (also known as RISC-loading complex RNA-binding subunit) that binds to dsRNA [20]. DICER1-mediated cleavage can lead to formation of iso-miRNAs that differ from normal miRNAs [21]. TARBP2 binds to DICER1 in a physical manner via Argonaute proteins (Ago1, Ago2, Ago3 or Ago4) to eventually assemble the miRNA-induced silencing complex (miRISC) [20].

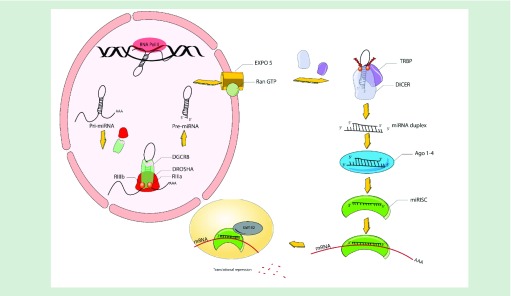

Ago removes the reverse complementary strand of the miRNA, which can then bind to target mRNAs and recruit the miRISC components to facilitate degradation. Degradation occurs in processing bodies, in other words, P-bodies, which are cytoplasmic foci, that are however unnecessary for miRNA-mediated gene silencing (Figure 1) [21].

Figure 1. . Overview of miRNA biogenesis.

miRNA genes are transcribed in the form of fundamental miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) via RNA Pol II within the nucleus. Longer pri-miRNAs are subjected to cleavage by a microprocessor that consists of DGR8 to create 60–70 nucleotide precursor miRNAs, in other words, pre-miRNAs. These pre-miRNAs are exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm via XPO5 prior to being further processed via DICER1, an RIII enzyme that creates mature miRNAs. A single miRNA strand binds to the miRISC that includes Ago protein and DICER1 enzyme and assembles the miRISC for the purpose of targeting mRNAs through sequence supplementary binding, while mediating gene suppression via targeted translational repression and mRNA degradation within procedural bodies.

Ago: Argonaute; miRISC: miRNA invoked silencing composite; Pol II: Polymerase II; pri: Primary; RIII: Ribonuclease III;.

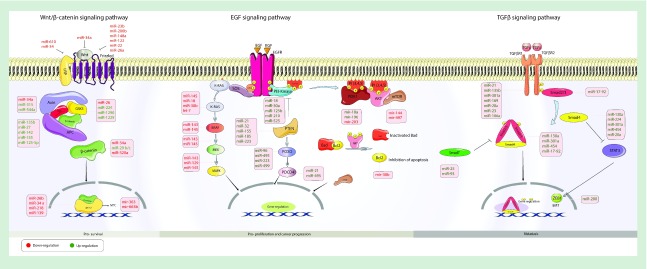

miRNAs … CRC pathogenesis

CRC is a heterogeneous disease in which various signaling pathways play critical roles in its progression [22–24]. miRNAs are important regulators, which could target components of pathways involved in cancer progression, most notably APC, K-RAS and p53, which can act as oncogenes or tumor-suppressor genes in CRC (Figure 2) [23,25]. These targets are involved in angiogenesis, apoptosis, cell cycle regulation and metastasis. Therefore, miRNA deregulation can influence cancer growth.

Figure 2. . Various miRNAs involved in colorectal cancer pathogenesis.

The large number of miRNAs has been divided into those that operate by three main signaling pathways: (i) wnt/β-catenin; (ii) EGF receptor; (iii) TGF-β receptor.

EMT: Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition.

Let-7 (a family of miRNAs) can act as a negative regulator for the human RAS oncogene and is often downregulated in human tumors [26,27]. Akao et al. observed that let-7 miRNA showed reduced expression in both CRC tumors and cell lines. Significant growth inhibition was reported in cells transfected with a let-7a-1 construct. After transfection, the RAS and c-myc protein levels were remarkably lowered. A functional SNP has been reported in the let7 complementary site (LCS) in the 3′-UTR region of K-RAS, which consists of a T to G base change [28]. This SNP, known as LCS6, could attenuate the binding affinity between let-7 and K-RAS mRNA [29]. Early-stage CRC patients who were found to carry a K-RAS-LCS6 variant showed better outcomes [29].

MiR-143 has been shown to be frequently downregulated in CRC, and the K-RAS oncogene is one of the direct targets of miR-143 in CRC [30]. A negative correlation was observed between K-RAS protein and miR-143 in CRC tissue samples. Concordantly, the K-RAS expression level was reduced by a miR-143 mimic, whereas a miR-143 inhibitor induced an increase in K-RAS protein, and stimulated cell proliferation in a CRC cell line [31]. An association between K-RAS mutations and upregulation of miR-127-3p, miR-486-3p, miR-92a has been reported, and also with miR-378 downregulation. Some predicted target genes of the deregulated miRNAs, in cells with mutated or wild-type K-RAS (including RSG3 and TOB1), are involved in the apoptosis and proliferation pathways [32].

MiR-30b is expressed at significantly lower levels in CRC tissues, compared with normal surrounding tissues, and can stimulate G1 cell cycle arrest and induce apoptosis in CRC cells. This miRNA could target the oncogenes K-RAS and the antiapoptotic BCL2 gene [33]. Overexpression of miR-210 can inhibit clonogenicity, cause cell cycle arrest and an increase in generation of reactive oxygen species in CRC cell lines. In addition, miR-210 stimulated apoptosis in CRC cell lines, through upregulation of proapoptotic Bim (a member of the BCL-2 family), and enhancement of processing of caspase 2 [34].

Aberrant activation of the Wnt signaling pathway is associated with the initiation of CRC in the majority of human patients [35]. Tang et al. investigated the role of miR-93 in CRC, and its effect on the Wnt signaling pathway [36]. They demonstrated the tumor-suppressor role of miR-93 in CRC, via inhibition of the Wnt signaling pathway through regulating its Smad7 target gene. miR-93 inhibition induced cell proliferation, migration and metastasis in CRC cells. By contrast, overexpression of miR-93 inhibited the tumor aggressive phenotype. Kim et al. reported the positive correlation between p53, an important tumor-suppressor protein, and miR-34, which resulted in transcriptional suppression of β-catenin-TCF/LEF complexes [37]. Inactivation of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), a key component of the Wnt pathway and a tumor-suppressor gene, is a major initiating event in CRC [38,39]. APC-free β-catenin activates the transcription of the target genes involved in the Wnt signaling pathway, leading to activation of this pathway [40]. MiR-135a and miR-135b showed considerable upregulation in CRC. These miRNAs could target the 3′-UTR region of APC, leading to post-transcriptional suppression of its expression and activation of Wnt signaling. Overexpression of miR-135a and miR-135b induced the progression of colorectal adenomas to adenocarcinomas [41]. Axin, a negative regulator of Wnt signaling, is a direct target of miR-315. Overexpression of this miRNA resulted in activation of Wnt signaling [42]. miR-200a targets ZEB1 (also known as Tcf8) and ZEB2 (or SIP1), which are E-cadherin repressors. This led to the available E-cadherin for binding to β-catenin being increased [43]. In addition, miR-200a downregulation resulted in enhancement of free β-catenin in the cytoplasm and nucleus [44]. Ling et al. reported a high level of miR-224 in microsatellite-stable CRC samples compared with those with microsatellite instability. miR-224 overexpression promoted CRC metastasis to lung and liver in a mouse model [45]. The negative correlation between SMAD4 (an inhibitor of Wnt signaling pathway) and miR-224, implied that SMAD4 could be one of its targets.

miRNAs as diagnostic … therapeutic biomarkers in CRC

Efficient medical intervention for patients diagnosed with early primary CRC results in increased survival rates [46]. Numerous reports imply that understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms contributing to CRC pathogenesis, may play a vital role in the discovery of novel therapeutic, prognostic and diagnostic biomarkers in CRC patients [47]. miRNAs are the one of most promising options for CRC biomarkers with many advantages [48]. At the present time, detecting stage II CRC in patients is a major challenge, and the use of biomarkers may play a role in this goal [49]. Yamazaki et al. showed that miRNA deregulation may be useful as a diagnostic biomarker for patients with stage II CRC [50]. Their findings showed that a set of miRNAs, namely miR-128a, miR-23c, let-7a, let-7d, let-7e, miR-26b, miR-151-5p and miR-181c, are subjected to dysregulation in patients with stage II CRC. These results indicated that miR-181c may be used as a prognostic biomarker for the likelihood of disease reappearance. Furthermore, recurrence rates were correlated with miR-181c upregulation in CRC patients [50].

Michael et al. were the first to show alteration of miRNA profiles in CRC [51]. They reported that miR-143 and miR-145 were downregulated in CRC, and designated them as putative tumor-suppressor miRNAs. Other studies have validated the suppressor function of miR-143 and miR-145 in CRC [52–54]. miR21 is known to be a key regulator of several oncogenic processes and is involved in CRC [55]. Kulda et al. aimed to study the relationship between miR-21 and miR-143 expression levels, and the occurrence of CRC and colorectal liver metastases (CLM) [56]. The study was performed on a set of 46 paired (CRC tumor and control tissues) and 30 CLM tissue samples. They recorded an increase in miR-21 expression in CRC tissues versus control tissues. In contrast, miR-143, which functions as a tumor suppressor had lower expression in CRC tissues. Surprisingly, these expression profile patterns were repeated in CLM tissues.

Ng et al. investigated the occurrence of a panel of 95 cancer-related miRNAs in plasma and biopsy samples taken from five CRC patients, compared with plasma from five healthy controls [57]. The five miRNA markers measured (including miR-135b, miR-92, miR-95, miR-222 and miR-17-3p) were upregulated in both CRC plasma and biopsies, compared with controls. Upon re-evaluating these miRNA expression levels in an independent set of CRC serum samples, miR-17-3p and miR-92 showed the most significant increase in CRC samples, and were also significantly decreased in postoperative samples compared with preoperative tissues. In a further study, plasma miRNA levels were measured in a total of 159 plasma samples (including 100 CRC and 59 healthy controls). This study found that miR-29a and miR-92a were significantly upregulated in CRC serum samples compared with controls [58]. These miRNAs also showed a significantly increased expression profile in plasma samples from 37 advanced adenomas compared with those from healthy controls, emphasizing the diagnostic value of miR-29a and miR-92a in early lesions. The authors suggested that both miRNAs could be used as biomarkers for advanced adenomas, and the likelihood of progressing to CRC.

Ogata-Kawata et al. analyzed exosomal miRNAs in the serum of 88 primary CRC patients and 19 healthy controls [59]. Exosomes in CRC samples compared with controls, showed that eight miRNAs (let-7a, miR-23a, miR-223, miR-21, miR-150, miR-1246, miR-1229 and miR-1224-5p) showed a significantly increased expression in serum, but were downregulated after surgery. In order to verify their previous results, they re-evaluated the expression levels of these miRNAs by qRT-PCR of serum exosomes in a sample set including eight healthy controls, seven stage I and six stage II CRC patients. All (except miR-1224-5p) were significantly elevated in serum of CRC patients compared with controls. Arndt et al. reported that six miRNAs (miR-31, miR-7, miR-99b, miR-378, miR-133a and miR-125a) could discriminate early-stage disease (mostly stage II) and late stage (mostly stage III) in 45 CRC cases [60].

Ziad et al. analyzed miRNA signatures in a set of 46 CRC patients using cancer and adjacent normal tissue, 60 plasma samples of CRC patients and healthy controls [55]. miR-1 and miR-133a were the two most downregulated miRNAs, while miR-31 and miR-135b were the most upregulated in CRC tissue samples. Also, the expression level of miR-31 in stages III and IV was significantly higher than in stages I and II. In addition, they introduced plasma miR-21 as a reliable and promising biomarker for CRC. In a study from Wang et al., miR-31 was shown to be related to tumor stage and tumor invasion in 98 CRC biopsy samples compared with the adjacent noncancerous specimens, and was positively related to advanced-stage cancer and widespread metastasis [61]. Toiyama et al. reported a contradictory result concerning miR-31. They screened miR-31 expression levels in a set of 24 serum samples from CRC samples and normal subjects. No statistically significant difference was noted in levels of serum miR-31 expression [62]. In an independent set of samples of eight CRC biopsies and adjacent normal mucosa, the miR-32 levels were significantly increased in CRC tissues, which is consistent with other reports [55,63]. They claimed that miR-32 was upregulated in cancerous tissue but was not secreted into the bloodstream.

Matsumura et al. focused on altered miRNA expression in serum exosomes for the early diagnosis of recurrence in CRC patients [64]. The study was carried out using 299 serum samples, and found that the miR-17-92a cluster expression level was correlated with CRC recurrence. miR-17-92a is a well-known polycistronic cluster that encodes six individual miRNAs, miR-17, miR-18a, miR-19a, miR-20a, miR-19b and miR-92a [65].

Another study aimed to identify miRNAs in 208 CRC and healthy control stool samples as a novel approach for screening of CRC [66]. miR-135b levels were significantly increased in CRC stool samples compared with healthy controls. They claimed that stool-based miR-135b could function as a potential CRC biomarker.

Since some miRNAs, namely miR-506, miR-487b, miR-20a, miR-126, miR-31 and miR-33a, are subject to downregulation in CRC, and may function as a tumor-suppressor implying therapeutic possibilities. Zu et al. showed that miR-506 plays the role of a tumor repressor in CRC cells, while the upregulation may hinder CRC cell growth via targeting LAMC1 [67]. Therefore, miR-506 may be effective as a novel therapeutic target for CRC patients. LAMC1 is an important CRC target, and plays a role in the growth of this disease [68].

A study conducted by Hata et al. showed that miR-487b plays the role of a tumor suppressor, as well as a negative controller of CRC liver metastasis through the KRAS signaling pathway [69]. miR-487b was downregulated in CRC patients with liver metastasis. Furthermore, miR-478b overexpression was associated with better prognosis. Evidently, miR-487b overexpression is able to hinder the invasiveness and cell proliferation. miR-487b downregulates KRAS, and signaling pathways that are related to KRAS. MiR-487b may impact LRP6, which is a receptor in the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway. The results imply that miR-487b may be employed as a possible therapeutic biomarker for patients with CRC and liver metastasis [69].

Table 1 lists various miRNAs that have been tested as prognostic, diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers in CRC.

Table 1. . miRNAs as prognostic, diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers in colorectal cancer.

| miRNA | Biomarker | Expression in CRC | Target | Detection method | Sample size | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21 | Diagnosis | Upregulation | PDCD4 | qRT-PCR | 10 | [70] |

| miR-143 | Diagnosis | Downregulation | DNMT3A | qRT-PCR | 40 | [71] |

| miR-143 | Diagnosis | Downregulation | MACC1 | Western blot and luciferase assay | 6 | [41] |

| miR-143 | Diagnosis | Downregulation | KRAS | qRT-PCR and luciferase | - | [72] |

| miR-143 | Diagnosis | Downregulation | ERK5 | PCR | - | [59] |

| miR-143 | Diagnosis | Downregulation | KLF5, BRAF and CD44 | qRT-PCR | - | [54] |

| miR-497 | Diagnosis | Downregulation | IGF-1 | Microarray | 5 | [73] |

| miR-675 | Diagnosis | Upregulation | RB | Luciferase assay | 30 | [54] |

| miR-200c | Diagnosis | Upregulation | TGF-β2 and ZEB1 | Luciferase assay | [74] | |

| miR-27b | Therapeutic agent | Downregulation | VEGF C | Microarray | [75] | |

| miR-195 | Therapeutic agent | Downregulation | Bcl-2 | Luciferase assay | [76] | |

| miR-137 | Diagnosis | Downregulation | Cdc42 | Luciferase assay, Western blot and qRT-PCR | [77] | |

| miR-196a | Diagnosis | Upregulation | Homeobox protein | RT-PCR | [78] | |

| miR-34a | Diagnosis | Downregulation | E2F | Microarray | [79] | |

| miR-145 | Diagnosis | Downregulation | Insulin receptor substrate-1 | Luciferase assay | [59] | |

| miR-145 | Diagnosis | Downregulation | KLF5, BRAF and CD44 | qRT-PCR | [54] | |

| Let-7a-1 | Diagnosis | Downregulation | RAS | qRT-PCR | [80] | |

| miR-137 | Diagnosis | Downregulation | FMNL2 | Luciferase assay, qRT-PCR | [70] | |

| miR-125 | Prognosis | Upregulation | P53, p21 | RT-PCR | 89 | [81] |

| miR-451 | Diagnosis | Downregulation | COX-2, ABCB1 | qRT-PCR | 35 | [71] |

| miR-449b | Diagnosis | Downregulation | E2F3, CCND1 | RT-PCR | [73] | |

| miR-21 | Diagnosis | Upregulation | PDCD4 | Microarray, immunohistochemistry | 10 | [74] |

| miR-135a miR-135b |

Diagnosis | Upregulation | APC | qRT-PCR, Western blot | 43 | [41] |

| miR-31 | Diagnosis | Upregulation | STATB2 | Luciferase assay | 174 | [75] |

| miR-342 | Potential therapeutic agent | Downregulation | DNMT1 | Western blot, luciferase assay | 15 | [76] |

| miR-95 | Diagnosis | Upregulation | SNX1 | Luciferase assay, Western blot | [82] | |

| miR-491 | Potential therapeutic agent | Downregulation | Bcl-XL | Luciferase assay, Western blot | [72] | |

| miR-320a | Potential therapeutic agent | Downregulation | NRP-1 | Luciferase assay, Western blot and qRT-PCR | 62 | [77] |

| miR-10b | Prognostic indicator of chemosensitivity to 5-FU | Upregulation | BIM | Luciferase assay, Western blot | [78] | |

| miR-224 | Prognosis | Upregulation | p21Cip1 and p27Kip1, PHLPP1 and PHLPP2 | Luciferase assay | [79] |

CRC: Colorectal cancer; qRT: Real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR; RB: Retinoblastoma.

miRNAs … cancer-associated fibroblasts

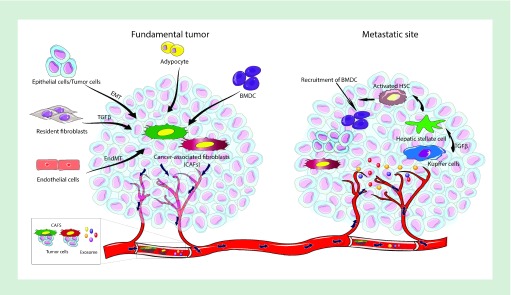

Fibroblasts have been long recognized as a prominent component of human tumors and may be categorized as either activated or resting fibroblasts [83]. Activated fibroblasts are characteristic of wound-healing sites [84]. Stimulated fibroblasts infiltrate lesions while generating ECM to act as a scaffold for the proliferation of various new cells. After a wound is fully healed, the activated fibroblasts regress to a dormant phenotype that is referred to as resting or NFs [85]. It is known that the growth of tumors is not only attributed to proliferating malignant cells but also to CAFs [86]. CAFs promote the spreading and growth of cancer cells by secreting not only ECM but also various chemokines and cytokines [83,87]. In regard to fibroblast activation, growth factors such as FGF2, TGF-β and VEGF are known to play important roles [88,89]. Moreover, the molecular mechanism of the conversion of the NFs into CAFs is incompletely understood [90]. Numerous lines of evidence show that miRNAs play a governing role in not only in carcinogenesis but also in fibroblast activation and conversion (Figure 3 … Table 2)

Figure 3. . Schematic depiction showing the activity of cancer-associated fibroblasts in tumors and at metastatic sites.

CAFs arise from different cells, for example, resident fibroblasts, adipocytes, endothelial cells through an endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, tumor cells via EMT and BMDCs. CAFs with various colors denote heterogeneous CAF populations that may possess tumor-suppressing or tumor-promoting properties. The CAFs that promote tumors induce protumorigenic and prometastatic signals at the tumor site. CAFs can escort tumor cells to reach the bloodstream, and allow extravasation to form new metastatic tumors. In addition to the production of ECM, CAFs produce factors that support tumor development at distant sites. The tumor cells secrete exosomes, which may accumulate in metastatic organs, for example, the lungs and liver. For the liver, as shown, exosomes are taken up by Kupffer cells that then induce the creation of premetastatic niches in the liver. Various pathways of CAFs, namely TGF-βR, PDGFR, hedgehog and integrins may prevent the activation of CAFs, or lessen CAF-derived tumorigenic signal secretion. Moreover, dysregulated miRNA can be reversed in CAFs by using miRNA mimetics, anti-miRNAs or siRNA delivery causing reversal of the CAF phenotype. These approaches may hinder CAF-activated protumorigenic and prometastatic signals and augment drug delivery via reduction of intratumoral pressure, in addition to inhibiting production of the prometastatic niche.

BMDC: Bone marrow-derived cell; ECM: Extracellular matrix; EMT: Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; PDGFR: PDGF receptor; TGF-βR: TGF-β receptor.

Table 2. . Selected miRNAs related to cancer-associated fibroblast formation.

| Cancer | miRNA | Expression | Effect (s) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal cancer | miR-10b | Upregulation | Promote cancer growth | [91] |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | miR-21 | Upregulation | Effect on EMT | [92] |

| miR-155 | Upregulation | Effect on EMT | [92] | |

| miR-146a | Upregulation | Effect on EMT | [92] | |

| miR-148a | Upregulation | Effect on EMT | [92] | |

| let-7g | Upregulation | Effect on EMT | [92] | |

| Prostate cancer | miR-210 | Upregulation | Effect on EMT and angiogenesis | [93] |

| miR-133b | Upregulation | Cancer progression | [94] | |

| miR-409-3p | Upregulation | Promote tumorigenesis and EMT | [95] | |

| miR-409-5p | Upregulation | Promote tumorigenesis and EMT | [95] | |

| miR-133b | Upregulation | IL-6 stimulation of CAF released miR133b to active NF | [94] | |

| Lung cancer | miR-1 | Downregulation | Migration, colony formation, TAM recruitment, tumor growth and angiogenesis | [96] |

| miR-1247-3p | Upregulation | Induce metastasis | ||

| miR-206 | Downregulation | Migration, colony formation, TAMs recruitment, tumor growth and angiogenesis | [96] | |

| miR-31 | Upregulation | Migration, colony formation, TAMs recruitment, tumor growth and angiogenesis | [96] | |

| Pancreatic cancer | miR-155 | Upregulation | Growth, invasion | [97] |

| miR-199a | Upregulation | Migration and proliferation | [98] | |

| miR-214 | Upregulation | Migration and proliferation | [98] | |

| Breast cancer | miR-221/222 | Upregulation | Cancer progression | [99] |

| miR-200 s | Upregulation | Cancer progression | [3] | |

| Ovarian cancer | miR-31 | Downregulation | Growth, invasion, motility | [5] |

| miR-214 | Downregulation | Growth, invasion, motility | [5] | |

| miR-155 | Upregulation | Cancer progression | [5] | |

| Esophageal cancer | miR-21 | Upregulation | Cancer progression | [100] |

| miR-27a/b | Upregulation | Increased secretion of TGF-β leads to cisplatin resistance | [101] | |

| Breast cancer | miR-200 s | Downregulation | Migration, invasion, metastasis | [3] |

| miR-9 | Upregulation | Migration and invasion | [102] | |

| Melanoma | miR-211 | Upregulation | Proliferation, motility, collagen contraction | [103] |

| miR-155 | Upregulation | Promote angiogenesis | [104] | |

| miR-424 | Upregulation | Cancer growth | [105] | |

| Gastric cancer | miR-27a | Upregulation | Increase the proliferation and motility | [106] |

| Head and neck cancer | miR-7 | Upregulation | Enhance cell proliferation and migration | [107] |

CAF: Cancer-associated fibroblast; EMT: Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; NF: Normal fibroblast; TAM: Tumor-associated macrophages.

Mitra et al. conducted a study, which showed the downregulation of miR-214 and miR-31 in ovarian cancer and CAFs, as well as the upregulation of miR-155 in tumor adjacent fibroblasts in comparison with NFs [5]. Laboratory modeling of this deregulation through transfecting miRNAs and use of miRNA inhibitors also produced a functional transformation of NFs to CAFs. The reverse experiment led to the regression of CAFs back to NFs. There were a number of chemokine genes that were upregulated in the miRNA-reprogrammed NFs and in patient-derived CAFs, and these genes were deemed vital to CAF function. The chemokine that was most upregulated, in other words, C–C motif ligand 5 (CCL5) was determined to be a direct miR-214 target. These findings show that ovarian cancer cells enable the reprogramming of fibroblasts to transition into CAFs via the action of miRNAs. The targeting of these miRNAs in stromal cells may be a therapeutic strategy [5].

Shen et al. discovered that miRNAs were involved in the transformation of NFs into CAFs [96]. Results of this study showed that miR-1 and miR-206 were subject to downregulation, while miR-31 was upregulated in lung CAFS in comparison to matched NFs. The modification of the expression pattern of the three deregulated miRNAs was related to the conversion of NFs to CAFs, and vice versa. Upon the coculture of the mi-RNA-transformed NFs and the authentic CAFs with lung cancer cells, an identical cytokine expression profile pattern was evident in the two groups. By utilizing cytokine expression profiling combined with miRNA algorithms, VEGFA/CCL2 and FOXO3a were determined to be the direct targets of miR-1, miR-206 and miR-31, respectively. Systemic delivery of anti-VEGFA/CCL2 or pre-miR-1, pre-miR-206 and anti-miR-31 resulted in substantial inhibition of tumor angiogenesis, tumor-associated macrophages, tumor development and lung metastasis. The findings demonstrated the integral role of miRNA-mediated FOXO3a/VEGF/CCL2 signaling in lung cancer cells and the NF to CAF transition that could have future clinical implications as new biomarker(s) and possible curative target(s) for lung cancer [96].

Other studies on esophageal cancer showed that miR-27a/b was a mediator for the formation of CAFs with increased TGF-β production that caused cisplatin resistance [101]. Evidently, miR-7 overexpression in NFs triggers the NF to CAF conversion in head and neck cancer via the downregulation of RASSF2, leading to reduced PAR-4 secretion by CAFs, augmenting the spread and migration of cocultured cancer cells [107]. Other comparable results showed that NFs displayed downregulated miR-200s and exhibited the properties of activated CAFs with regard to breast cancer. The upregulation of lysyl oxidase and fibronectin promoted the migration, metastasis and infiltration of the cancer cells [3]. In prostate cancer, hypoxia-induced miR-210 overexpression in proliferating fibroblasts enhanced senescence-related traits, and transformed NFs into CAF-type cells, promoting the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT in the cancer cells) [93].

MiR-21 binds to the 3′-UTR of Smad7 mRNA while decreasing competitive binding to TGFBR, because Smad7 binds to Smad2 and Smad3. Deregulation of miR-21 or Smad7 promotes the formation of CAFs in the absence of TGF-β1 stimulation [108]. Other esophageal cancer studies showed that miR-21 may cause the activation of NFs and their transformation to CAFs [100]. With regard to pancreatic cancer, miR-214 and miR-199a overexpression is a prominent regulator of CAF activation, increasing the spreading and migration of cancer cells [98]. In gastric cancer CAFs, miR-149 was downregulated. miR-149 hinders the stimulation of fibroblasts via IL-6 downregulation. Other research showed that CAFs could augment the EMT and increase stem-cell-type traits within gastric cancer cells, which were dependent on miR-149-IL-6. PTGER2 (subtype EP2) is a possible miR-149 target. Helicobacter pylori infection possibly increases the protumor characteristics of stromal fibroblasts through silencing of mmu-miR-149 and stimulation of IL-6 secretion [109]. Moreover, the expression of miR-409 in NFs increases the CAF phenotype and causes miR-409 secretion in extracellular vesicles in order to promote EMT and tumor induction [87].

CAFs … CRC progression

The most abundant cells in most connective tissues are fibroblasts, which form the structural backbone of the tissue by the production of ECM. CAFs are heterogeneous primary cells present in the stroma of tumors, which undergo irreversible activation resulting in dense fibrosis or desmoplasia around the tumor through deposition of excessive amounts of ECM. The cross-talk between CAFs and cancer cells occurs in both directions: cancer cells induce a reactive response in CAFs; and the CAFs affect cancer cell malignancy [110]. CAFs are abundant in the stroma associated with many tumors, including breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, as well as CRC [111,112].

The overexpression of PDGF and fibroblast activation protein (FAP) has been extensively reported in CAFs located within solid tumor tissues [111,113]. FAP is a protein involved in the EMT process, and is implicated in CRC invasion [114,115]. It is overexpressed in CAFs compared with NFs in patients, which make it a CAF biomarker and a potential target for anticancer therapy [116]. Based on immunohistochemical staining, FAP was expressed by CAFs in 85–90% of specimens from 44 CRC patients. The high stromal levels of FAP were associated with poor prognosis and were linked to more aggressive progression in CRC patients [117,118]. The conditioned medium isolated from CRC cell lines stimulated FAP expression in CAFs. These activated fibroblasts stimulated the invasive behavior of CRC cells through FGF1/FGF receptor 3 (FGF1/FGFR-3) signaling [119]. High activation of PDGF receptor signaling is one of the major functional findings in CAFs and is usually associated with increased invasive behavior in CRC. STC1 is a secreted glycoprotein, that can act as a mediator of CRC metastasis through PDGF receptor signaling. A significant correlation between stromal PDGF receptor and STC1 expression has been observed in CRC. An in vivo study in a CRC mouse model showed that STC1-deficient fibroblasts formed tumors with reduced invasion, and fewer and smaller distant metastases compared with those in the presence of STC1 in fibroblasts [120]. Blocking the PDGF receptor pathway in CAFs inhibited CRC cell growth and metastasis in the CRC mouse model [121].

Nakagawa et al. generated a gene expression profile of fibroblast cells obtained from liver and skin from metastatic CRC patients. CAFs and skin fibroblasts showed a distinct gene expression pattern and were each clustered into a group; many genes related to growth factors, cell adhesion molecules and cyclooxygenase-2 were upregulated in liver CAFs compared with skin fibroblasts. Base on immunohistochemistry, the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and TGF-β2 was detected in CAFs from metastatic CRC. Also, the conditioned media from these isolated CAFs could enhance HCT116 cell growth [122]. CAFs are able to detoxifiy metabolites and buffer the acidity in the colorectal tumor environment, thereby displaying a metabolic protumorigenic effect [123].

miRNA derived from colorectal CAF cells

Cancer-related fibroblasts, in other words, CAFs are important components of the tumor microenvironment encouraging tumor development, despite the poor understanding of the relevant mechanisms. Exosomes are prominent mediators of intercellular communication with regard to cancer. Exosomes mediate the horizontal transfer of miRNAs, proteins and mRNAs, and can affect the progression of cancer (Table 3). Donnarumma et al. conducted a study in which exosomal mRNAs extracted from breast CAFs were assessed [124]. Their findings showed that differential expression patterns of three miRNAs (i.e., miR-21, miR-378e and -143) were seen in exosomes from CAFs in comparison to typical fibroblasts. Immunofluorescence studies showed that exosomes could be transferred from CAFs to breast cancer cells, releasing cargo miRNAs. Breast cancer cells that were exposed to CAF exosomes, in other words, BT549, MDA-MB-231 and T47D cell lines, or transfected with relevant miRs displayed substantial enhancement of their ability to form mammospheres, enhanced stem cell characteristics and EMT markers, as well as anchorage-independent cell growth. These observations were reversed via transfection with anti-miRNAs. As with CAF exosomes, typical fibroblast exosomes that were transfected with miR-21, miR-378e and miR-143 showed increased stemness and the EMT phenotype in breast cancer cells. This paper showed unprecedented evidence for the effect of CAF exosomes and the relevant miRNAs on stemness and EMT phenotype in several breast cancer cell lines. CAFS significantly promoted the development of a more aggressive breast cancer cell phenotype [124].

Table 3. . Selected miRNAs derived from cancer-associated fibroblasts in various cancers.

| Cancer | miRNA (s) | Expression in cancer | Effects (s) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal cancer | miR-329, miR-181a, miR-199b, miR-382, miR-215 and miR-21 | Upregulation | Cancer progression | [125] |

| miR-31 | Upregulation | Enhance radiosensitivity | [126] | |

| miR-10b | Upregulation | Cancer progression | [127] | |

| miR-141 | Downregulation | Cancer progression | [128] | |

| Pancreatic cancer | miR-199a-3p and miR-214-3p | Upregulation | Induce migration and proliferation | [98] |

| Lung cancer | miR-1 | Upregulation | Induce cell proliferation and chemoresistance to cisplatin | [129] |

| miR-200 | Downregulation | Growth and metastasis of tumor cells | [130] | |

| Ovarian cancer | miR-21 | Upregulation | Induce metastasis | [131] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | miR-21 | Upregulation | Induce secretion of angiogenic cytokines, including VEGF, MMP2, MMP9, bFGF and TGF-β | [132] |

| miR-320a | Downregulation | Cancer progression | [133] | |

| Osteosarcoma | miR-1228 | Upregulation | Promote osteosarcoma invasion and migration | [134] |

| Oral cancer | miR-34a-5p | Downregulation | Induce the EMT | [135] |

| miR-145 | Upregulation | Tumor progression | [136] | |

| Endometrial cancer | miR-148b | Downregulation | Enhancing cancer cell metastasis | [137] |

| Prostate cancer | miR-409 | Upregulation | Tumor progression | [95] |

EMT: Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition.

MiR-21 is an oncogenic miRNA, which is subject to upregulation in different types of cancer, namely lung adenocarcinoma [138–141]. At a cellular level, prior studies were mostly focused on the overexpression of miR-21 in cancer cells that increases cellular proliferation, EMT, apoptosis evasion and invasion. The effect of miR-21 in CAFs is currently being studied with regard to numerous cancers [142,143].

Kunita et al. conducted a study where they hypothesized that the overexpression of miR-21 in lung fibroblasts stimulated lung adenocarcinoma tumor growth by upregulation of CAF activity [144]. They used in situ hybridization (ISH) to validate their hypothesis in order to analyze the expression of miR-21 in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections from lung adenocarcinoma. Subsequently, they assessed whether miR-21 was involved in the interaction between lung fibroblasts and lung adenocarcinoma cancer cells in vitro. It is noteworthy that miR-21 was expressed significantly in lung adenocarcinoma cells and CAFs and its expression in CAFs exhibited an inverse correlation with the survival of patients. The findings of this study implied that the expression of miR-21 in lung fibroblasts invoked the CAF phenotype and has an effect on lung adenocarcinoma development. Thus, miR-21 can be considered as a new molecular biomarker for the prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma [144].

Recent emerging evidence has shown that cancer stem cells (CSCs) that are a stem cell-like population found in tumors, might play a critical role in CRC initiation, metastasis, relapse and chemoresistance [145,146]. CAFs can affect the tumor microenvironment and ECM, which generate the CSC niche. Moreover, the cross-talk between cancer cells and CAFs could stimulate tumor development and progression, but the underlying mechanism is not yet clear [147,148]. Hu et al. studied whether CAFs might increase the fraction of CSCs thus inducing chemoresistance [149]. CAF-derived exosomes promoted the emergence of CSCs, which are inherently resistant to chemotherapy, upon treatment with oxaliplatin or 5-fluorouracil. Accordingly, inhibition of exosome secretion caused a significant decrease in the percentage, clonogenicity and tumor formation of CSCs. Also, Lotti et al. suggested that colorectal CSCs caused an increase in chemoresistance by affecting CAFs [150]. CAFs secreted specific cytokines, such as IL-17A, which increased self-renewal and invasiveness in CSCs. It is worth noting that chemotherapy induces IL-17A overexpression in colorectal CAFs. Very recent research suggested that miRNAs were key players in the tumor-supportive function of CAFs [151].

Recently, Ren et al. investigated the molecular mediators involved in CRC-promoting roles of CAFs, and the role of H19 in stemness and chemoresistance in CRC. H19, a long noncoding RNA, has a critical role in embryonic development, hematopoietic stem cells, and in human cancers such as CRC, breast cancer, bladder cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma [152–155]. In CRC patients, overexpressed H19 was related to poor prognosis and was shown to be implicated in CRC cell proliferation, cell cycle progression and metastasis [156,157]. The results of this study showed that H19 was highly overexpressed in colitis-associated cancer (CAC) mice and in different stage of CRC. In addition, H19 overexpression could enhance stemness and oxaliplatin resistance in CRC cells. Importantly, H19 could be secreted from CAF exosomes, which mediates the cross-talk between tumor stromal cells and CRC cells in the tumor microenvironment. Moreover, this long noncoding RNA acted as an endogenous RNA sponge for miR-141, a suppressor for CRC cell stemness and activated the β-catenin pathway. miR-21 is predominantly expressed in CAFs located in the tumor microenvironment and is significantly correlated with shorter disease-free survival in CRC patients [128]. Yamamichi et al. reported that miR-21 was upregulated in CRC, and in CAFs adjacent to CRC tissues [158]. Aberrant expression of miR-21 was not observed in fibroblasts farther away from the tumor site. They suggested that CAFs might induce miR-21 expression due to secreted fibroblast-derived factors. Bullock et al. examined the effects of miR-21 deregulation in the cancer-associated stroma [159]. Compared with normal tissue, miR-21 was approximately fourfold overexpressed in CRC stroma. Conditioned medium originating from miR-21-overexpressing fibroblast enhanced CRC cell resistance to oxaliplatin, a commonly used chemotherapy drug, and also increased tumor progression.

Bhome et al. sought to identify and characterize exosomal miRNAs that mediated cross-talk between CAFs and CRC cells [160]. They found that exosomal miRNA, originating from CAFs, induced proliferation and chemoresistance in CRC cells. The miRNA signature delivered in CAF exosomes consisted of miR-329, miR-181a, miR-199a, miR-382, miR-215 and miR-21, with the most abundant being miR-21. Also, miR-21-overexpressing fibroblasts and CRC cells resulted in increased liver metastasis compared with control fibroblasts in a mouse model of orthotopic xenografts. Dai et al. explored the miRNA expression signature of CRC cell-derived exosomes, and identified some miRNAs that showed remarkable differential expression compared with normal cells, including miR-10b [127]. Exosomes that contained an abundant level of miR-10b stimulated tumor growth and enhanced TGF-β and SM α-actin production in CAFs. The PIK3CA signaling pathway was suppressed in fibroblasts containing miR-10b. These results showed that cancer cells can potentially control fibroblast cells through the secretion of exosomes.

Another study aimed to identify whether miRNA-derived from CRC stroma were associated with liver metastasis [161]. Abundant expression of miR-221 and miR-222 was detected, not only in CRC cells but also in CAFs, which showed a significant association with liver metastasis, distant metastasis, as well as with a shorter survival rate in CRC patients.

Autophagy has both advantages and disadvantages with regard to tumor growth. Current research has determined the inhibitory impact of miRNAs on regulation of autophagy. It has been documented that miR-31 exerts an important effect on CRC growth [162]. Although its precise role has not yet been discovered. Yang et al. showed that expression of miR-31 in CAFs exceeded that in normal colorectal fibroblasts (NFs) [126]. Their findings showed that CAF treatment with a miR-31 mimic reduced the expression of the autophagy-related genes Beclin-1, ATG, DRAM and LC3 expression. Moreover, it was determined that miR-31 upregulation substantially impacted CRC cell functions, namely apoptosis, invasion and proliferation. In addition, miR-31 upregulation in CAFs may enhance the radiosensitivity of CRC cells that have been cocultured with CAFs. To summarize, miR-31 may hinder autophagy within colorectal CAFs while affecting the development of CRC and increasing radiosensitivity [126].

Conclusion … future perspective

CRC is a prevalent disease across the world with increasing incidence. A variety of internal and external risk factors (i.e., genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors) are associated with the initiation and development of CRC. Among these different factors, epigenetic factors have central roles in CRC pathogenesis. miRNAs are one of the important epigenetic players, which are involved in a sequence of vital cell-biology processes (e.g., growth, differentiation and angiogenesis). Increasing evidence has shown that deregulation of these molecules is associated with CRC pathogenesis. Therefore, it seems that further exploration of the roles of these molecules may establish them as prognostic, therapeutic and diagnostic biomarkers for CRC patients.

Cancer survival is negatively associated with metastatic proliferation, and a better understanding of the signaling pathways that govern aggressiveness, metastasis and treatment resistance is urgently required. Cancer stroma (including CAFs) has an important influence on the spread and invasion of tumors as well as encouraging CRC chemo- and radio-resistance. The influence of miRNA expression and function on the interaction between CAFs and cancer cells has not yet been fully clarified. Growing evidence suggests that miRNAs contribute to the conversion of NFs into CAFs and vice versa. miRNAs secreted from CAFs may influence several different traits of cancer cells. Different miRNAs such as miR-21, miR-329, miR-181a, miR-199a, miR-382 and miR-215 that have been found in colorectal CAFs, may encourage enhanced proliferation, invasiveness and chemoresistance, by affecting neighboring tumor cells via paracrine signaling pathways. A deeper understanding of the exosomal miRNAs released from CAFs, and their cellular and molecular roles in the pathogenesis of CRC, could contribute to designing and developing new therapeutic approaches. We have not been able to trace any clinical trials targeting CAF-derived miRNAs as yet. It does appear that such trials could be introduced in clinical settings in the near future. Further investigation can contribute to the discovery of new biomarkers and the development of new therapeutic platforms.

Executive summary.

miRNA biogenesis

miRNAs are short noncoding RNAs that regulate post-transcriptional gene silencing.

miRNAs are produced by a complex molecular cascade ending in the miRNA-induced silencing complex.

miRNAs … colorectal cancer pathogenesis

miRNAs can target components of pathways involved in colorectal cancer (CRC) progression, APC, K-RAS and p53, which can act as oncogenes or tumor-suppressor genes.

Let 7, miR-143, miR-30b can affect apoptosis pathways.

miR-93 can affect Wnt signaling and miR-135a and miR-135b are involved with APC.

miRNAs as diagnostic … therapeutic biomarkers in CRC

miRNA deregulation may be useful as a diagnostic biomarker for prognosis and progression in patients with CRC.

miRNAs … cancer-associated fibroblasts

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) promote the spreading and growth of CRC cells by secreting not only extracellular matrix but also various chemokines and cytokines.

miRNAs are involved in the transformation of normal fibroblasts into CAFs via Smad and TGF-β signaling.

CAFs … CRC progression

Gene expression patterns of CAFs encourage growth, metastasis of CRC.

CAFs can alter the tumor microenvironment favoring tumor progression.

miRNA derived from colorectal CAF cells

Exosomes are secreted by CAFs and can transfer miRNAs to CRC cells.

Cross-talk between CRC cells and CAFs can increase cancer stem cells and induce chemoresistance.

Footnotes

Financial … competing interests disclosure

MR Hamblin was supported by US NIH grants R01AI050875 and R21AI121700. MR Hamblin declares the following potential conflicts of interest. Scientific Advisory Boards: Transdermal Cap Inc., Cleveland, OH, USA; BeWell Global Inc., Wan Chai, Hong Kong; Hologenix Inc., Santa Monica, CA, USA; LumiThera Inc., Poulsbo, WA, USA; Vielight, Toronto, Canada; Bright Photomedicine, Sao Paulo, Brazil; Quantum Dynamics LLC, Cambridge, MA, USA; Global Photon Inc., Bee Cave, TX, USA; Medical Coherence, Boston MA USA; NeuroThera, Newark, DE, USA; JOOVV Inc., Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN, USA; AIRx Medical, Pleasanton CA, USA; FIR Industries, Inc., Ramsey, NJ, USA; UVLRx Therapeutics, Oldsmar, FL, USA; Ultralux UV Inc., Lansing MI, USA; Illumiheal … Petthera, Shoreline, WA, USA; MB Lasertherapy, Houston, TX, USA; ARRC LED, San Clemente, CA, USA; Varuna Biomedical Corp., Incline Village, NV, USA; Niraxx Light Therapeutics, Inc., Boston, MA, USA. Consulting: Lexington Int., Boca Raton, FL, USA; USHIO Corp., Japan; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany; Philips Electronics Nederland B.V., Eindhoven, The Netherlands; Johnson … Johnson Inc., Philadelphia, PA, USA; Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Stockholdings: Global Photon Inc., Bee Cave, TX, USA; Mitonix, Newark, DE, USA. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.De Vlieghere E, Verset L, Demetter P, Bracke M, De Wever O. Cancer-associated fibroblasts as target and tool in cancer therapeutics and diagnostics. Virchows Archiv. 467(4), 367–382 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Good review about the role of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in cancer diagnosis and treatment.

- 2.Han Y, Zhang Y, Jia T, Sun Y. Molecular mechanism underlying the tumor-promoting functions of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts. Tumour Biol. 36(3), 1385–1394 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang X, Hou Y, Yang G. et al. Stromal miR-200s contribute to breast cancer cell invasion through CAF activation and ECM remodeling. Cell Death Differ. 23(1), 132–145 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali S, Suresh R, Banerjee S. et al. Contribution of microRNAs in understanding the pancreatic tumor microenvironment involving cancer associated stellate and fibroblast cells. Am. J. Cancer Res. 5(3), 1251–1264 (2015). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitra AK, Zillhardt M, Hua Y. et al. MicroRNAs reprogram normal fibroblasts into cancer-associated fibroblasts in ovarian cancer. Cancer Discov. 2(12), 1100–1108 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Showing that miRNAs can reprogram normal fibroblasts into CAFs.

- 6.Griffiths-Jones S, Saini HK, Van Dongen S, Enright AJ. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 36(Database Issue), D154–D158 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altuvia Y, Landgraf P, Lithwick G. et al. Clustering and conservation patterns of human microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 33(8), 2697–2706 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haier J, Strose A, Matuszcak C, Hummel R. miR clusters target cellular functional complexes by defining their degree of regulatory freedom. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 35(2), 289–322 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75(5), 843–854 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science 294(5543), 853–858 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Important paper first describing miRNAs.

- 11.Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 39(Database Issue), D152–D157 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N. Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nat. Rev. Genet. 9(2), 102–114 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregory RI, Yan KP, Amuthan G. et al. The microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature 432(7014), 235–240 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Kim YK, Jin H, Kim VN. The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev. 18(24), 3016–3027 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burke JM, Kelenis DP, Kincaid RP, Sullivan CS. A central role for the primary microRNA stem in guiding the position and efficiency of Drosha processing of a viral pri-miRNA. RNA 20(7), 1068–1077 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heo I, Ha M, Lim J. et al. Mono-uridylation of pre-microRNA as a key step in the biogenesis of group II let-7 microRNAs. Cell 151(3), 521–532 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yi R, Qin Y, Macara IG, Cullen BR. Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev. 17(24), 3011–3016 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park JE, Heo I, Tian Y. et al. Dicer recognizes the 5′ end of RNA for efficient and accurate processing. Nature 475(7355), 201–205 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee Y, Kim M, Han J. et al. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 23(20), 4051–4060 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chendrimada TP, Gregory RI, Kumaraswamy E. et al. TRBP recruits the Dicer complex to Ago2 for microRNA processing and gene silencing. Nature 436(7051), 740–744 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin S, Gregory RI. MicroRNA biogenesis pathways in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15(6), 321–333 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang JY, Richardson BC. The MAPK signalling pathways and colorectal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 6(5), 322–327 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • miRNAs and colorectal cancer (CRC) pathogenesis.

- 23.Smith G, Carey FA, Beattie J. et al. Mutations in APC, Kirsten-ras, and p53 – alternative genetic pathways to colorectal cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99(14), 9433–9438 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leggett B, Whitehall V. Role of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 138(6), 2088–2100 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moridikia A, Mirzaei H, Sahebkar A, Salimian J. MicroRNAs: potential candidates for diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 233(2), 901–913 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takamizawa J, Konishi H, Yanagisawa K. et al. Reduced expression of the let-7 microRNAs in human lung cancers in association with shortened postoperative survival. Cancer Res. 64(11), 3753–3756 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J. et al. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell 120(5), 635–647 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chin LJ, Ratner E, Leng S. et al. A SNP in a let-7 microRNA complementary site in the KRAS 3′ untranslated region increases non–small cell lung cancer risk. Cancer Res. 68(20), 8535–8540 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smits KM, Paranjape T, Nallur S. et al. A let-7 microRNA SNP in the KRAS 3'UTR is prognostic in early-stage colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 17(24), 7723–7731 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pichler M, Winter E, Stotz M. et al. Down-regulation of KRAS-interacting miRNA-143 predicts poor prognosis but not response to EGFR-targeted agents in colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 106(11), 1826 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen X, Guo X, Zhang H. et al. Role of miR-143 targeting KRAS in colorectal tumorigenesis. Oncogene 28(10), 1385 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosakhani N, Sarhadi VK, Borze I. et al. MicroRNA profiling differentiates colorectal cancer according to KRAS status. Gene. Chromosome. Canc. 51(1), 1–9 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liao WT, Ye YP, Zhang NJ. et al. MicroRNA-30b functions as a tumour suppressor in human colorectal cancer by targeting KRAS, PIK3CD and BCL2. J. Pathol. 232(4), 415–427 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tagscherer KE, Fassl A, Sinkovic T. et al. MicroRNA-210 induces apoptosis in colorectal cancer via induction of reactive oxygen. Cancer Cell Int. 16(1), 42 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brabletz T, Jung A, Hermann K, Günther K, Hohenberger W, Kirchner T. Nuclear overexpression of the oncoprotein β-catenin in colorectal cancer is localized predominantly at the invasion front. Pathol. Res. Pract. 194(10), 701–704 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang Q, Zou Z, Zou C. et al. MicroRNA-93 suppress colorectal cancer development via Wnt/β-catenin pathway downregulating. Tumor Biol. 36(3), 1701–1710 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim NH, Kim HS, Kim NG. et al. p53 and microRNA-34 are suppressors of canonical Wnt signaling. Sci. Signal. 4(197), ra71–ra71 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sparks AB, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Mutational analysis of the APC/β-catenin/Tcf pathway in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 58(6), 1130–1134 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang L, Shay JW. Multiple roles of APC and its therapeutic implications in colorectal cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 109(8), (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fodde R, Brabletz T. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cancer stemness and malignant behavior. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19(2), 150–158 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagel R, Le Sage C, Diosdado B. et al. Regulation of the adenomatous polyposis coli gene by the miR-135 family in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 68(14), 5795–5802 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silver SJ, Hagen JW, Okamura K, Perrimon N, Lai EC. Functional screening identifies miR-315 as a potent activator of Wingless signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104(46), 18151–18156 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Korpal M, Lee ES, Hu G, Kang Y. The miR-200 family inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer cell migration by direct targeting of E-cadherin transcriptional repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. J. Biol. Chem. 283(22), 14910–14914 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burk U, Schubert J, Wellner U. et al. A reciprocal repression between ZEB1 and members of the miR-200 family promotes EMT and invasion in cancer cells. EMBO Rep. 9(6), 582–589 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • miRNAs as diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers in CRC.

- 45.Ling H, Pickard K, Ivan C. et al. The clinical and biological significance of MIR-224 expression in colorectal cancer metastasis. Gut 65(6), 977–989 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chi Y, Zhou D. MicroRNAs in colorectal carcinoma-from pathogenesis to therapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 35(1), 1 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dakubo GD. Colorectal cancer biomarkers in circulation. : Cancer Biomarkers in Body Fluids. Springer, NY, USA, 213–246 (2017.). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dong Y, Yu J, Ng SS. MicroRNA dysregulation as a prognostic biomarker in colorectal cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 6, 405 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Misiakos EP, Karidis NP, Kouraklis G. Current treatment for colorectal liver metastases. World J. Gastroenterol. 17(36), 4067–4075 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamazaki N, Koga Y, Taniguchi H. et al. High expression of miR-181c as a predictive marker of recurrence in stage II colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 28(10), 14344 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Michael MZ, O'connor SM, Van Holst Pellekaan NG, Young GP, James RJ. Reduced accumulation of specific microRNAs in colorectal neoplasia. Mol. Cancer Res. 1(12), 882–891 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akao Y, Nakagawa Y, Hirata I. et al. Role of anti-oncomirs miR-143 and-145 in human colorectal tumors. Cancer Gene Ther. 17(6), 398 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akao Y, Nakagawa Y, Naoe T. MicroRNA-143 and-145 in colon cancer. DNA Cell Biol. 26(5), 311–320 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pagliuca A, Valvo C, Fabrizi ED. et al. Analysis of the combined action of miR-143 and miR-145 on oncogenic pathways in colorectal cancer cells reveals a coordinate program of gene repression. Oncogene 32(40), 4806 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kanaan Z, Rai SN, Eichenberger MR. et al. Plasma miR-21: a potential diagnostic marker of colorectal cancer. Ann. Surg. 256(3), 544–551 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kulda V, Pesta M, Topolcan O. et al. Relevance of miR-21 and miR-143 expression in tissue samples of colorectal carcinoma and its liver metastases. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 200(2), 154–160 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ng EK, Chong WW, Jin H. et al. Differential expression of microRNAs in plasma of patients with colorectal cancer: a potential marker for colorectal cancer screening. Gut 58(10), 1375–1381 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang Z, Huang D, Ni S, Peng Z, Sheng W, Du X. Plasma microRNAs are promising novel biomarkers for early detection of colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 127(1), 118–126 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ogata-Kawata H, Izumiya M, Kurioka D. et al. Circulating exosomal microRNAs as biomarkers of colon cancer. PLoS ONE 9(4), e92921 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arndt GM, Dossey L, Cullen LM. et al. Characterization of global microRNA expression reveals oncogenic potential of miR-145 in metastatic colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 9(1), 374 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang CJ, Zhou ZG, Wang L. et al. Clinicopathological significance of microRNA-31,-143 and-145 expression in colorectal cancer. Dis. Markers 26(1), 27–34 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Toiyama Y, Takahashi M, Hur K. et al. Serum miR-21 as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in colorectal cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 105(12), 849–859 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Slattery ML, Herrick JS, Mullany LE. et al. An evaluation and replication of mi RNA s with disease stage and colorectal cancer-specific mortality. Int. J. Cancer 137(2), 428–438 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matsumura T, Sugimachi K, Iinuma H. et al. Exosomal microRNA in serum is a novel biomarker of recurrence in human colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 113(2), 275 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Concepcion CP, Bonetti C, Ventura A. The miR-17-92 family of microRNA clusters in development and disease. Cancer J. (Sudbury, Mass.) 18(3), 262 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu CW, Ng SC, Dong Y. et al. Identification of microRNA-135b in stool as a potential noninvasive biomarker for colorectal cancer and adenoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 20(11), 2994–3002 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zu C, Liu T, Zhang G. MicroRNA-506 inhibits malignancy of colorectal carcinoma cells by targeting LAMC1. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 46(6), 666–674 (2016). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peters U, Jiao S, Schumacher FR. et al. Identification of genetic susceptibility loci for colorectal tumors in a genome-wide meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 144(4), 799–807.e724 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hata T, Mokutani Y, Takahashi H. et al. Identification of microRNA-487b as a negative regulator of liver metastasis by regulation of KRAS in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 50(2), 487–496 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liang L, Li X, Zhang X. et al. MicroRNA-137, an HMGA1 target, suppresses colorectal cancer cell invasion and metastasis in mice by directly targeting FMNL2. Gastroenterology 144(3), 624–635.e624 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bitarte N, Bandres E, Boni V. et al. MicroRNA-451 is involved in the self-renewal, tumorigenicity, and chemoresistance of colorectal cancer stem cells. Stem Cells 29(11), 1661–1671 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nakano H, Miyazawa T, Kinoshita K, Yamada Y, Yoshida T. Functional screening identifies a microRNA, miR-491 that induces apoptosis by targeting Bcl-XL in colorectal cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer 127(5), 1072–1080 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fang Y, Gu X, Li Z, Xiang J, Chen Z. miR-449b inhibits the proliferation of SW1116 colon cancer stem cells through downregulation of CCND1 and E2F3 expression. Oncol. Rep. 30(1), 399–406 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baffa R, Fassan M, Volinia S. et al. MicroRNA expression profiling of human metastatic cancers identifies cancer gene targets. J. Pathol. 219(2), 214–221 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang MH, Yu J, Chen N. et al. Elevated microRNA-31 expression regulates colorectal cancer progression by repressing its target gene SATB2. PLoS ONE 8(12), e85353 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang H, Wu J, Meng X. et al. MicroRNA-342 inhibits colorectal cancer cell proliferation and invasion by directly targeting DNA methyltransferase 1. Carcinogenesis 32(7), 1033–1042 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang Y, He X, Liu Y. et al. microRNA-320a inhibits tumor invasion by targeting neuropilin 1 and is associated with liver metastasis in colorectal cancer. Corrigendum in/10.3892/or. 2015.3773. Oncol. Rep. 27(3), 685–694 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nishida N, Yamashita S, Mimori K. et al. MicroRNA-10b is a prognostic indicator in colorectal cancer and confers resistance to the chemotherapeutic agent 5-fluorouracil in colorectal cancer cells. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 19(9), 3065–3071 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liao WT, Li TT, Wang ZG. et al. microRNA-224 promotes cell proliferation and tumor growth in human colorectal cancer by repressing PHLPP1 and PHLPP2. Clin. Cancer Res. 19(17), 4662–4672 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang J, Yan F, Zhao Q. et al. Circulating exosomal miR-125a-3p as a novel biomarker for early-stage colon cancer. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 4150 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nishida N, Yokobori T, Mimori K. et al. MicroRNA miR-125b is a prognostic marker in human colorectal cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 38(5), 1437–1443 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huang Z, Huang S, Wang Q. et al. MicroRNA-95 promotes cell proliferation and targets sorting Nexin 1 in human colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 71(7), 2582–2589 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• miRNAs and CAFs.

- 83.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6(5), 392–401 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3(5), 349–363 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Parsonage G, Filer AD, Haworth O. et al. A stromal address code defined by fibroblasts. Trends Immunol. 26(3), 150–156 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mueller MM, Fusenig NE. Friends or foes - bipolar effects of the tumour stroma in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4(11), 839–849 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Orimo A, Gupta PB, Sgroi DC. et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell 121(3), 335–348 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Elenbaas B, Weinberg RA. Heterotypic signaling between epithelial tumor cells and fibroblasts in carcinoma formation. Exp. Cell Res. 264(1), 169–184 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brown LF, Guidi AJ, Schnitt SJ. et al. Vascular stroma formation in carcinoma in situ, invasive carcinoma, and metastatic carcinoma of the breast. Clin. Cancer Res. 5(5), 1041–1056 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Aprelikova O, Palla J, Hibler B. et al. Silencing of miR-148a in cancer-associated fibroblasts results in WNT10B-mediated stimulation of tumor cell motility. Oncogene 32(27), 3246–3253 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dai G, Yao X, Zhang Y. et al. Colorectal cancer cell-derived exosomes containing miR-10b regulate fibroblast cells via the PI3K/Akt pathway. Bull. Cancer 105(4), 336–349 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Paggetti J, Haderk F, Seiffert M. et al. Exosomes released by chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells induce the transition of stromal cells into cancer-associated fibroblasts. Blood 126(9), 1106–1117 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Taddei ML, Cavallini L, Comito G. et al. Senescent stroma promotes prostate cancer progression: the role of miR-210. Mol. Oncol. 8(8), 1729–1746 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Doldi V, Callari M, Giannoni E. et al. Integrated gene and miRNA expression analysis of prostate cancer associated fibroblasts supports a prominent role for interleukin-6 in fibroblast activation. Oncotarget 6(31), 31441–31460 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Josson S, Gururajan M, Sung SY. et al. Stromal fibroblast-derived miR-409 promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and prostate tumorigenesis. Oncogene 34(21), 2690–2699 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shen H, Yu X, Yang F. et al. Reprogramming of normal fibroblasts into cancer-associated fibroblasts by miRNAs-Mediated CCL2/VEGFA Signaling. PLoS Genet. 12(8), e1006244 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pang W, Su J, Wang Y. et al. Pancreatic cancer-secreted miR-155 implicates in the conversion from normal fibroblasts to cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Sci. 106(10), 1362–1369 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kuninty PR, Bojmar L, Tjomsland V. et al. MicroRNA-199a and -214 as potential therapeutic targets in pancreatic stellate cells in pancreatic tumor. Oncotarget 7(13), 16396–16408 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shah SH, Miller P, Garcia-Contreras M. et al. Hierarchical paracrine interaction of breast cancer associated fibroblasts with cancer cells via hMAPK-microRNAs to drive ER-negative breast cancer phenotype. Cancer Biol. Ther. 16(11), 1671–1681 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nouraee N, Van Roosbroeck K, Vasei M. et al. Expression, tissue distribution and function of miR-21 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE 8(9), e73009 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tanaka K, Miyata H, Sugimura K. et al. miR-27 is associated with chemoresistance in esophageal cancer through transformation of normal fibroblasts to cancer-associated fibroblasts. Carcinogenesis 36(8), 894–903 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Baroni S, Romero-Cordoba S, Plantamura I. et al. Exosome-mediated delivery of miR-9 induces cancer-associated fibroblast-like properties in human breast fibroblasts. Cell Death Dis. 7(7), e2312 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Garcia-Silva S, Peinado H. Melanosomes foster a tumour niche by activating CAFs. Nat. Cell Biol. 18(9), 911–913 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhou X, Yan T, Huang C. et al. Melanoma cell-secreted exosomal miR-155-5p induce proangiogenic switch of cancer-associated fibroblasts via SOCS1/JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 37(1), 242 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhang D, Wang Y, Shi Z. et al. Metabolic reprogramming of cancer-associated fibroblasts by IDH3alpha downregulation. Cell Rep. 10(8), 1335–1348 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang J, Guan X, Zhang Y. et al. Exosomal miR-27a derived from gastric cancer cells regulates the transformation of fibroblasts into cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 49(3), 869–883 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• miRNA derived from CRC-associated fibroblast cells.

- 107.Shen Z, Qin X, Yan M. et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote cancer cell growth through a miR-7-RASSF2-PAR-4 axis in the tumor microenvironment. Oncotarget 8(1), 1290–1303 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• CAFs and CRC progression.

- 108.Li Q, Zhang D, Wang Y. et al. MiR-21/Smad 7 signaling determines TGF-beta1-induced CAF formation. Sci. Rep. 3, 2038 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Li P, Shan JX, Chen XH. et al. Epigenetic silencing of microRNA-149 in cancer-associated fibroblasts mediates prostaglandin E2/interleukin-6 signaling in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Res. 25(5), 588–603 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Giannoni E, Bianchini F, Masieri L. et al. Reciprocal activation of prostate cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts stimulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stemness. Cancer Res. 70(17), 6945–6956 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6(5), 392 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pietras K, Östman A. Hallmarks of cancer: interactions with the tumor stroma. Exp. Cell Res. 316(8), 1324–1331 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Cirri P, Chiarugi P. Cancer-associated-fibroblasts and tumour cells: a diabolic liaison driving cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 31(1-2), 195–208 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Review of the effects of CAFs in cancer progession.

- 114.Shi M, Yu DH, Chen Y. et al. Expression of fibroblast activation protein in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma and its clinicopathological significance. World J. Gastroenterol. 18(8), 840 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Garin-Chesa P, Old LJ, Rettig WJ. Cell surface glycoprotein of reactive stromal fibroblasts as a potential antibody target in human epithelial cancers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 87(18), 7235–7239 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Scott AM, Wiseman G, Welt S. et al. A Phase I dose-escalation study of sibrotuzumab in patients with advanced or metastatic fibroblast activation protein-positive cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 9(5), 1639–1647 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wikberg ML, Edin S, Lundberg IV. et al. High intratumoral expression of fibroblast activation protein (FAP) in colon cancer is associated with poorer patient prognosis. Tumor Biol. 34(2), 1013–1020 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Henry LR, Lee HO, Lee JS. et al. Clinical implications of fibroblast activation protein in patients with colon cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 13(6), 1736–1741 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Henriksson ML, Edin S, Dahlin AM. et al. Colorectal cancer cells activate adjacent fibroblasts resulting in FGF1/FGFR3 signaling and increased invasion. Am. J. Pathol. 178(3), 1387–1394 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Peña C, Céspedes MV, Lindh MB. et al. STC1 expression by cancer-associated fibroblasts drives metastasis of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 73(4), 1287–1297 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kitadai Y, Sasaki T, Kuwai T, Nakamura T, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Targeting the expression of platelet-derived growth factor receptor by reactive stroma inhibits growth and metastasis of human colon carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 169(6), 2054–2065 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]