In The Lancet today, Bradley Mathers and colleagues1 make a heroic effort—in fact, a systematic review—to document the coverage (services provided per individual in need of services) for HIV prevention and care for injecting drug users (IDUs) throughout the world. Whilst the problems in obtaining data and in assessing the quality of data that could be obtained were formidable, two conclusions can be safely drawn. First, there is great variation in coverage of HIV-related services for IDUs across different countries; and second, in much of the world, coverage is clearly inadequate.

There is considerable evidence that HIV-prevention programmes for IDUs, particularly combined programming, in which multiple programmes are provided, can be very effective in reducing injecting-related HIV transmission.2, 3 This evidence suggests that the primary global need is not for new interventions to change the behaviour of IDUs, but for effective interventions to change the behaviour of policy makers to make policies and programmes consistent with the evidence base for HIV prevention and care for IDUs. Over the past 25 years, several useful theories have been developed for changing the health behaviour of IDUs and others at high risk for HIV. It may be time to apply those theories to changing the behaviour of policy makers.

The first set of theories are diffusion of innovations and social learning/modelling theories. These theories articulate how new behaviours spread through social systems and how individuals in these systems influence each other to either adopt (or resist) new behaviours.4, 5 These theories have been applied in IDU interventions developed by many different researchers and have the major advantage of often producing self-sustaining behavioural changes in the IDU community. Applying these theories to changing the behaviour of national policy makers raises interesting questions. Is the policy-making system relatively open or relatively closed to innovations? Is the policy-making system highly centralised (one decision centre) or decentralised (multiple decision centres)? Who might become the early adopters and serve as models or opinion leaders for others in the system? The answers to such questions would provide guidance about initiating system change.

The second theory is contingency management. This theory comes from basic behaviourism theory.6, 7 If you want to increase the frequency with which an individual performs a specific behaviour, provide a reward when the individual completes the desired behaviour. Syringe-exchange programmes in which a drug user is given a new sterile syringe for bringing in a used and potentially contaminated syringe might be the most common example of contingency management to reduce HIV transmission. Within behaviour theory, one-for-one reinforcement is typically not the most effective schedule for behavioural change. For syringe exchange, the maximum reductions in risk behaviour seem to occur when drug users are provided with sufficient numbers of syringes to meet their own needs, and they obtain extra syringes which can then be given to peers, leading to additional social reinforcement. Syringe-exchange programmes typically have many services in addition to basic exchange,8 which serve as additional reinforcers. Who would provide what sort of reward to political leaders for implementing HIV services for IDUs? The reward of averting large numbers of HIV infections in IDUs is certainly important, but is not consistent with a primary principle of contingency management: that rewards should be given immediately after performance of the desired behaviour. International donors, however, could require that evidence-based services for IDUs be included in national plans to address HIV for a country to receive any HIV prevention and treatment resources. The Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria has adopted this approach, although, as shown by Mathers and colleagues, there is a need for better follow-through to ensure that appropriate resources are actually provided to IDUs, particularly for antiretroviral therapy.

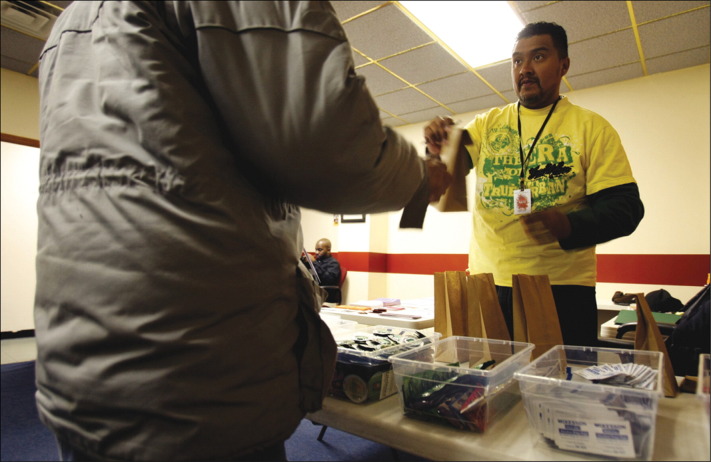

Needle-exchange programme

Care package, including new syringes, given by syringe-exchange worker at NJCRI (New Jersey Community Research Initiative) in Newark, New Jersey, USA.

© 2010 Corbis

The third theory is psychological framing of decisions. Framing refers to setting the psychological context within which a decision will be made.9, 10 The same person might make different decisions depending on how a question is framed. AIDS reframed the act of sharing syringes for IDUs. Before AIDS, sharing was an act of assistance and solidarity; after AIDS, sharing syringes became an act in which a fatal disease could be transmitted.

Many policy makers frame HIV prevention for IDUs in terms of what appears to encourage or condone drug use, and then oppose harm-reduction programmes. Within this frame, data showing that such programmes do not lead to increased drug use have had little effect in reducing opposition.

It might be more effective to frame HIV prevention for IDUs in terms of the health of the community as a whole, and that public health is fundamental to the economic wellbeing of a society. For example, the economic costs of the epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome in China were instrumental in convincing the Government there that it needed to address AIDS.11

What are we learning? Literally millions of dollars and euros have been spent on collecting data and evaluating interventions to change the HIV-related behaviours of IDUs. It is time to establish a mechanism for collecting and systematically analysing data on efforts to change policies to increase implementation of HIV programmes for IDUs.

HIV continues to spread among IDUs in many different countries, and the need for scaling up prevention and treatment is urgent. Although theory-based policy-implementation interventions need to be adapted to local situations, we suggest that contingency management and framing the issue in community health-economic terms might be the most useful for immediate policy change. Long-term sustained efforts to protect the health of individuals who use both licit and illicit drugs might require that policy makers acquire a basic scientific understanding of drug use and addiction, and frame policies toward drug users within a public health and human rights perspective.12

Acknowledgments

DCDJ joined the Reference Group to the UN on HIV and Injecting Drug Use, chaired by Bradley Mathers, in December, 2009. Preparation of this Comment was supported by US NIH grants R01AI 083035 and R01DA003574 (DCDJ and KA) and R01AI070005 (MG). KA and MG declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mathers B, Degenhardt L, Ali H, for the 2009 Reference Group to the UN on HIV and Injecting Drug Use HIV prevention, treatment, and care services for people who inject drugs: a systematic review of global, regional, and national coverage. Lancet. 2010 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60232-2. published online March 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on the Prevention of HIV Infection among Injecting Drug Users in High Risk Countries . Preventing HIV infection among injecting drug users in high risk countries: an assessment of the evidence. Institute of Medicine; Washington: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Des Jarlais D, Arasteh A, McKnight C. HIV infection during limited versus combined HIV prevention programs for IDUs in New York City: the importance of transmission behaviors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.028. published online Dec 12, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bandura A. Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall; Englewood, NJ: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogers E. Diffusion of innovations. The Free Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ledgerwood D, Petry N. Does contingency management affect motivation to change substance use? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rawson R, McCann M, Huber A. Contingency management and relapse prevention as stimulant abuse treatment interventions. In: Higgins ST, Silverman K, editors. Motivating behavior change among illicit-drug abusers: research on contingency management interventions. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Des Jarlais D, Arasteh K, McKnight C, Ringer M, Friedman SR. Syringe exchange, injecting and intranasal drug use. Addiction. 2010;105:155–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahneman D, Tversky A, editors. Choices, values and frames. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau R, Lev J. Contributions of behavioural decision theory to research in political science. Appl Psychol. 1998;47:29–44. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammett TM, Norton GD, Kling R. Community attitudes toward HIV prevention for injection drug users: findings from a cross-border project in southern China and northern Vietnam. J Urban Health. 2005;82(suppl 3):iv34–iv42. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Semaan S, Des Jarlais D, Malinowska-Sempruch K, et al. Human rights and HIV prevention among drug users. In: Beracochea E, Weinstein C, Evans D, eds. Right based approaches to public health. New York: Springer (in press).