Abstract

The present study examined relationships among leadership styles, work engagement and work outcomes designated by task performance and innovative work behavior among information and communication technology professionals in two countries: Ethiopia and South Korea. In total, 147 participants from Ethiopia and 291 from South Korea were made to fill in the self-reporting questionnaire intended to assess leadership styles, work engagement, task performance, and innovative work behavior. To test the proposed hypotheses, multiple linear regression analysis was utilized. The results showed that transformational leadership style had a significant positive relationship with employees' work engagement and innovative work behavior, while transactional leadership style had a significant positive relationship with employees' task performance. However, laissez-faire leadership style had a significant negative relationship with task performance. Work engagement had significant positive relationships with the indicators of work outcomes. Besides, work engagement partially mediated the relationship between leadership styles and work outcomes. The observed associations and mediation were consistent across the two national samples considered, indicating the soundness of the assumptions across countries. The findings provide insights into how leadership styles correspond with employees’ work outcomes.

Keywords: Leadership, Workplace, Innovation, Performance, Industry, Organization, Human resources, Work engagement, Transformation, Transaction, Technology management, Organizational theory, Human resource management, Behavioral psychology, Organizational psychology

Leadership; Workplace; innovation; Performance; industry; Organization; Human Resources; work engagement; transformation; transaction, Technology Management; Organizational Theory; Human Resource Management; Behavioral Psychology; Organizational Psychology

1. Introduction

Leadership is crucial for effective functioning of any organization. The fundamental of leadership is its persuading power on human resources, organizations' source of competitive advantage, and the resultant outcomes. In swaying followers and harnessing organization member's selves to their work roles, leaders must enhance employees' motivation as having engaged employees is critical for organization to achieve its goal (Batista-Taran et al., 2009). Studies, (e.g., Bakker and Bal, 2010; Harter et al., 2002; Xathopoulou et al., 2009) recorded the noteworthiness of employees' work engagement for organizational achievement measured in terms of monetary returns, productivity, client satisfaction, and a number of individual-level alluring employees' characteristics such as taking initiative and being proactive.

Literature (e.g. Bakker and Demerouti, 2008; Kim, 2014; Park et al., 2013; Saks, 2006; Salanova et al., 2011; Salanova and Schaufeli, 2008; Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004; Song et al., 2012; Xathopoulo et al., 2007) studied employee engagement within the framework of its antecedents and consequences using mainly the job demand-resources model, social exchange theory, social cognitive theory, and leadership theory. In the plethora of studies examining the correlates of employee engagement, particularly in Western and some Asian contexts, the most discussed antecedents included job resources, personal resources, perceived supports, learning organizations, and transformational leadership, while the personal-level outcomes considered were performance, turnover intention, organizational citizenship behavior, health, proactive behavior, innovative behavior, and knowledge creation practices. In spite of significant empirical studies on associates of work engagement, little research have been found that explored the potential link between leadership behaviors and employee engagement in the wider human resources literature (Carasco-Saul et al., 2015).

Thus, the current study focused on examining relationships among leadership styles, employee work engagement and work outcomes. Leadership was targeted because previous research (e.g. Xu and Thomas, 2011; Carasco-Saul et al., 2015) also elucidated scarcity of findings that connect leadership styles and employees work engagement. Further, the dominant capacity of leadership over other work variables and its vulnerability to modifications were taken into consideration in its selection as correlates of work engagement and outcomes. For workoutcomes, employees' job performance and innovative work behavior were considered because of their pertinence to organizational existence and progress. Job performance is the term that academics and practitioners use most commonly and widely. Nonetheless, an aggregate definition of success across jobs and roles is very difficult to conceptualize since employees are engaged in a large number of tasks including even those not listed out in their formal job description (Demerouti and Cropanzano, 2010). On the basis of review of previous studies, Kim (2014) outlined various ways of conceptualizing job performance ranging from overall performance to organizational citizenship behaviour. In the present study, as indicator of employees' job performance, in-role performance is conceptualized as accomplishment of core tasks and activities specified in employee contract document connected to officially defined organizational outcomes ((Demerouti and Cropanzano, 2010). In addition to performing main tasks officially listed out, considering the current competitive work environment, employees are pressed to go extra mile beyond those formally recognized in their job description such as being innovative in their workplace. As Ramoorthy et al. (2005) suggested, to succeed organizations are pressuring employees to innovate their methods and operations. Janssen (2000) was of the view that to have a continuous flow of innovation and to achieve goals, individual employees need to be skilled to innovate. What is more, employees’ innovative work behavior is comprehended as a specific form of extra-role performance related to discretionary employee actions in connection to generating idea, promoting, and realizing it.

In spite of evidences on the relationship between styles of leadership and work outcomes such as job performance and innovative work behavior (e.g., Khan et al., 2012; Solomon, 2016), studies explored the meditational role of work engagement in the link between leadership and work outcomes were insignificant. In connection to work engagement mediation between leadership behaviour and work outcomes, findings of the study are directing to quality of leader-subordinate relationships (Agarwal et al., 2012), transformational leadership (Salanova et al., 2011) and employees affective commitment to their immediate supervisor (Chughtai, 2013) as antecedent factors.

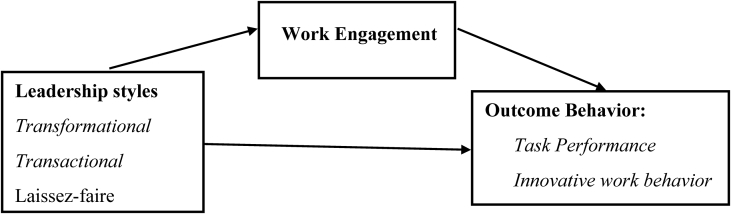

Thus, specifically, in the present study the researchers proposed and tested a model in which work engagement partly mediates relationship between leadership styles (focusing on the pattern of behavior of leaders’ exhibited) and work outcomes labelled by task performance and innovative work behavior. Hence, the conceptual model used in the study is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

Besides, the study also examined the associations among variables of the study and the mediation of work engagement in link between leaders’ style and work outcomes in two independent samples of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) professionals from Ethiopia and South Korea to test for soundness of suggested assumptions across the nations.

2. An overview of the study context

The participants of the study were professional ICT staffs working for for-profit companies engaged in ICT businesses in the two countries: Ethiopia and South Korea. Ethiopia is situated in the Horn of Africa; it has the second biggest populace in the continent, with more than 102 million occupants; however it has the most minimal per capita income (Ethiopia, 2018). Be that as it may, Ethiopia's economy has developed at a remarkable rate over the previous decade. As the International Monetary Fund (2016) revealed, the nation has had a great record of achievement of development and poverty decrease lately and it is portrayed as one of the fastest developing economies on the planet.

With respect to Ethiopia's work culture, on the continuum of Hofstede's dimensions of culture—power distance, collectivism vs. individualism, femininity vs. masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance—it is characterized by a large power distance, tight social ties and collective action, masculine characteristics, and high uncertainty avoidance (Beyene et al., 2016). Thus, in Ethiopian work culture, it appeared that power centralization is prevalent. Subordinates inclined to be told what to do and managers are expected to be influential and powerful. However, as Wasbeek (2004) indicated, individualism, masculinity, and a long-term orientation have been budding, specifically among the young and educated employees in Ethiopia.

South Korea, on the other hand, is an East Asian country on the southern portion of the Korean Peninsula and is home to more than 51 million people. South Korea is the fourth biggest economy in Asia and the eleventh biggest on the planet (South Korea, 2018).

When South Korean culture is examined, regarding power distance, it is a slightly hierarchical society with a collectivist nature and feminine as South Koreans are low on masculine/feminine dimension. Regarding uncertainty avoidance, South Korea might be taken as one of the most uncertainty avoiding countries, where people show a convincing enthusiastic prerequisite for rules, value time, and have an internal tendency to be involved and buckle down. Besides, South Korea's score on long-term orientation is at 100, showing that it is a highly pragmatic and long-term-oriented society (Compare Countries—Hofstede Insights, n.d.).

Nevertheless, as Yim (2002) indicated, Korean customary culture has in slight change, and to some level giving way to Western influx. Rapid socioeconomic transformation and the apparently indiscriminate inflow of Western culture were accounted for the change.

3. Previous research and hypotheses

3.1. Leadership styles and work-related outcomes

Leadership is the most commonly discussed topic in the organizational sciences. Lines of research may be delineated along three major approaches: trait, behavioral and inspirational. Trait theorists seek to identify a set of universal leadership traits whereas behaviorists focused on behaviors exhibited by specific leaders. Inspirational approach deliberated on leader as one who moves adherents through their words, thoughts and conduct (Robbins et al., 2009). As Carasco-Saul et al. (2015) suggested in the 1970s and 1980s, the charismatic leadership concept emerged, emphasizing that a charisma leader, a leader who inspires, attracts and influences followers by their personal qualities are considered effective. A typical characteristic of charismatic leadership is that it has the ability to motivate subordinates to concede to goals by imparting a vision, displaying charming behavior, and being a powerful model.

As part of neo-charismatic movement, full range leadership theory, which is also referred to as the Full Range Leadership Theory of Bass and Avolio's distinguished three groups of leaders in behaviors/styles: transformational, transactional and laissez-faire (Avolio et al., 1999; Bass and Riggio, 2006; Judge and Piccolo, 2004; Solomon, 2016). The theory defines a complete range of influencing styles from influential transformational leadership to laissez-faire style.

Based on a review of various studies, Vincent-Hoper et al. (2012) portrayed transformational leaders as managers who advance and propel their followers by anticipating and communicating appealing visions, common goals, and shared values, as well as by setting an illustration of the requested behavior. Facets of transformational leadership are: idealized influence (idealized attribution and idealized behavior), inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration (Bass and Avolio, 1994; Bass and Riggo, 2006).

Transactional leadership contains among other things, an exchange process (between leader & follower) that results in adherent compliance to leader demands, but it is not expected to create zeal and commitment to an errand objective (Trottier et al., 2008). The transactional leadership style constituted a constructive style labeled “contingent reward” and a corrective style labeled “management-by-exception.”

The last style is laissez-faire, which is characterized by non-involvement, showing indifference, being absent when needed, overlooking achievements and problems as well. It is a style of leadership in which leaders offer very little direction and allow group members to make decisions on their own (Bass and Riggio, 2006; Koech & Namusonge, 2012; Solomon, 2016).

Several studies (e.g., Judge and Piccolo, 2004; Pourbarkhordari et al., 2016; Solomon, 2016) examined the influence of leadership styles on a number of employee work outcomes critical to an organization's productivity and effectiveness, such as job satisfaction, commitment, performance, and motivation. Judge and Piccolo (2004) carried out a comprehensive meta-analytic review of studies that employed a complete range of leadership from influential transformational to influential laissez-faire style to test their relative validity in predicting a number of leadership criteria: follower job satisfaction, follower satisfaction with the leader, follower motivation, leader job performance, group or organizational performance, and leader effectiveness. The researchers found out an overall positive relationship for transformational leadership and transactional leadership (contingent rewards), but a negative overall relationship between laissez-faire style and the criteria considered.

Other researches in broad leadership literature (e.g, Bass and Avolio, 1994; Hayward et al., 2003; Kotter, 1988; Meyer and Botha, 2000) elucidated that transformational leadership style is the most successful in enhancing employee performance and other characteristics. In the studies, transformational leadership is positively related with a range of workplace desirable behaviour such as individual employee's performance, satisfaction and organizational performance. For instance, in South African pharmaceutical industry, Hayward et al., 2003) found a significant positive linear relationship between transformational leadership and employee performance but not for transactional leadership and employee performance. In Ethiopian education sector, Solomon (2016) reported positive association of both transformational and transactional styles of leadership with employees' performance while the relations of laissez-fair style with employees' performance failed to reach significance level. Khan et al. (2012) examined leadership styles (transformational, transactional & laissez-fair) assessed with Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire, as indicator variables in predicting innovative work behaviour and found out that both transformational and transactional leadership styles had positive relationship while laissez-faire had negative relationship with innovative work behaviour.

In general, it appears that transformational leadership style seems prominent in enhancing employees' work performance and other characteristics such as innovative behavior. The qualities of transformational leaders such as providing intellectual stimulation, inspiring followers through setting appealing vision and setting higher expectations maintains it effectiveness in organizational settings. Moreover, the motivational aspect and the fact that leaders serve as role model make this style to have profound influence on employees’ work outcomes. Because of the goal oriented nature of Transactional leaders focusing on expectations and recognizing achievement characteristics may positively initiate workers to exert higher levels of effort and performance Ejere and Abasilim (2013); Bass and Riggio (2006). Based on the above discussion, the followings were hypothesized:

H1

Transformational leadership style is positively related to (a) innovative work behavior and (b) task performance.

H2

Transactional leadership style is positively related to (a) innovative work behavior and (b) task performance.

H3

Laissez-faire style of leadership is negatively related to (a) innovative work behavior and (b) task performance.

H4

Transformational leadership style is positively related to work engagement.

H5

Transactional leadership style is positively related to work engagement.

H6

Laissez-faire leadership style is negatively related to work engagement.

3.2. Mediating role of work engagement

Kahn (1990) presented an early interpretation of engagement, which conceptualized it as personal involvement in the workplace reflecting a condition in which workers "bring in" their personal selves during job performance, expend personal energy and feel an emotional connection to their jobs. According to Kahn, engaged employees dedicate themselves physically, cognitively, and emotionally during role performances, while disengaged ones withdraw and guard themselves in all aspects (physically, cognitively & emotionally)in the course of role performances.

Based on Kahn's work, researchers—particularly those from the occupational health psychology fields further illuminate the concept of engagement. Early works based themselves on burnout model to clarify the concept of employee engagement (Maslach and Leiter, 1997; Maslach et al., 2001). To Maslach and Leiter, for instance, elements of engagement are energy, involvement, and efficacy, which are in stark contrast to the three burnout dimensions: exhaustion, cynicism, and lack of accomplishment, respectively. In the same burnout framework, an alternative view that considered work engagement as a unique concept stands by its own and negatively related to burnout appeared. As a concept by its own right work engagement, consequently, defined as a positive, fulfilling, work related state of mind characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá and Bakker, 2002). Here, Vigor refers to a high amount of drive and mental toughness while working, a willingness to invest effort in one's work, and sustain the determination even in the face of challenges. Dedication refers to a robust engagement in one's work and experiencing a sense of purpose and being enthusiastic, and absorption refers to fully and happily absorbed in one's work, such that time passes without notice while on work.

Despite some criticisms on confounding nature of some sub-constructs, the Schaufeli et al., 2002a, Schaufeli et al., 2002b model is hailed as a representative conceptualization of engagement and has been widely used in many fields (Jeung, 2011).

The distinctive essence of work engagement was described in various works using constructs, such as employee engagement, job engagement, and role engagement in line with Kahn's conceptualization (Rich, Lepine & Crawford, 2010; Rothbard, 2001; Saks, 2006). Among the different terms for engagement, work engagement and employee engagement are frequently and sometimes interchangeably used in literature. However the two terms vary in range in that work engagement focuses on the relationship between an individual employee and his or her work, while employee engagement applies to the relationships between the employee and the work and between the employee and the organization (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2010). In the current study, since the focus was on the specific relationship between an individual employee and his her work, the term “work engagement” and conceptualization of Schaufeli et al., 2002a, Schaufeli et al., 2002b which connotes work engagement as ‘a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption’ was utilized.

Regarding the links among leadership styles, work engagement, and employee outcome behaviors, a closer look at the related literature showed that the quality of leader–subordinate relationships (LMX), empowering leadership, and transformational leadership behavior were the most frequently discussed topics (Agarwal et al., 2012; Park et al., 2013; Zhang and Bartol, 2010). For instance, Agarwal et al. (2012) pointed out that the excellence of leader-member exchange influences engagement, and work engagement in turn correlates positively with innovative work behavior and negatively with intention to quit. The researchers asserted the meditational role of work engagement in the relationship between LMX as predictor and innovative work behavior and intention to quit as outcomes.

Park et al. (2013) also investigated the mediating effect of work engagement on the relationship between learning organizations and innovative behavior in the Korean context. The researchers found that a culture of learning organizations characterized by a positive learning environment, specific learning processes and procedures, and premeditated leadership behaviors through work engagement had direct and indirect impacts on the innovative work behaviors of employees.

In connection to transformational leadership and its link with various individual/organizational outcome behaviors, the mediating role of work engagement has been documented in various studies. Work engagement was found to mediate the link between transformational leadership and employees’ subjective occupational success designated by career satisfaction, social and career successes (Vincent-Höper et al., 2012), staff nurse extra-role performance (Salanova et al., 2011), organizational performance (Evelyn and Hazel, 2015), and organizational knowledge creation practices (Song et al., 2012). Thus, the researchers hypothesized:

H7

Work engagement is positively related to (a) innovative work behavior and (b) task performance.

H8

Work engagement partly mediates the relationship between leadership styles and work outcomes (task performance & innovative work behavior).

3.3. Cross-national aspects of leadership styles and work engagement

Despite some authors' claims that leadership styles are common across cultures, results are inconsistent with the degree to which leadership styles reign and their impact across cultures on followers. Shahin and Wright (2004) investigated the appropriateness of Bass and Avolio's leadership model in non-western country such as Egypt. They found that only certain factors that were considered as ideal leadership styles corresponded with U.S. factors, suggesting the influence of culture in labeling best leadership. Contrary to this finding, Walumbwa et al. (2007) made comparison based on data from China, India, Kenya, and the U.S. and found a robust manifestation of transformational and/or transactional leadership in these countries.

Ardichvili and Kuchinke (2002) carried out a comparative study on leadership styles and cultural values of managerial and non-managerial employees across culture by taking into account 10 business organizations in Russia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Germany, and the U.S., countries that differ widely in socio-economic and political orientation. The researchers elucidated that cross-cultural human resource development matters cannot be seen in terms of simplified dichotomies of East and West or developed versus developing economies.

In terms of the influences of leadership styles on work outcomes, it appeared that transformational-related behavior of leaders had a universally positive impact on followers’ behaviors (Dorfman et al., 1997; Walumbwa et al., 2005). For instance, Walumbwa et al. (2005) examined influence of transformational leadership on two work-related attitudes: organizational commitment and job satisfaction based on data from Kenya and the U.S. and obtained its strong positive effect on both indicators and in both countries. Dunn et al. (2012) also reported similar results on the association of transformational leadership with organizational commitment based on data collected from two countries: the U.S. and Israel.

With regard to work engagement as a psychological construct, cross-cultural investigations are scant. However, existing evidence reveals invariance in the construct—at least, in Western countries. For instance, Schaufeli et al., 2002a, Schaufeli et al., 2002b observed the invariance of the UWES, consisting of vigor, dedication, and absorption, on a sample of students from three countries: Spain, Portugal, and the Netherlands. Salanova and Schaufeli (2008) also reported the mediation model of work engagement in the link between job resources and managers’ proactive behavior at work in two independent samples drawn from Spain and the Netherland reflecting the consistence of the assertion across culture. In the current study, hence it was hypothesized that:

H9

The proposed relationships among study variables and thus the interceding of work engagement between leadership styles and work outcomes are consistent for the two national samples.

4. Materials and method

The study partly used a cross-sectional method of online survey research. As pointed out by Nasbary (2000), using an electronic format for a survey study does not pose any threat to the validity or reliability of the survey results, but rather has advantages such as low cost and rapid delivery.

4.1. Participants’ selection procedure

The target population for the study comprised of full-time professional ICT staff (with at least a college education) from for-profit companies engaged in ICT-related activities in Ethiopia and South Korea. Professionals in the ICT field were chosen mainly because of their crucial role in modern economic development in the least developed and advanced countries. Furthermore, the online survey was easily accessible due to their frequent contact to the internet. Additionally, selecting single industry enabled researchers to minimize errors emanating from industry-type. To collect data, Amharic (for Ethiopians) and Korean (for Koreans) versions of questionnaires were utilized for the study. In South Koreaa a survey company administered the questionnaire using random sampling approach in March–April, 2018. Using the company database, the questionnaire was sent to 500 staff, of which 300 replied. In Ethiopia, however, considering network quality and poor habit of using web, a hard-copy questionnaire was administered to 200 professionals selected by availability sampling in which 151 usable data were obtained. During data screening, nine extreme outliers (below or above 1.5 interquartile ranges of Q1 & Q3 respectively.) from South Korea and four from Ethiopia were removed. Thus, the analyses were based on 291 (Males = 229 [78.7%], Females = 62 [21.3%]) participants from South Korea and 147 (Males = 98 [66.7%], Females = 49 [33.3%]) from Ethiopia.

The School Scientific Committee for Research and Publication (School of Humanities & Social Sciences, Adama Science & Technology University) approved the proposal of the study. The purpose of the research was also clearly explained for the participants to obtain their consent for participation.

For the South Korean participants, the average age was 37 years, with 58 being the highest age and 24 the lowest. The average tenure was seven years. Qualification wise, 16 (5.5%) had a diploma, 226 (77.7%) a bachelor’ degree, 43 (14.8%) a master's degree, and six (2.1%) were PhD holders. With respect to work position, 182 (62.5%) worked as staff, while 95 (32.6%) and 14 (4.8%) South Korean participants worked as team leaders and department heads respectively. A total of 176 (59.5%) worked for companies engaged in software development, followed by 86 (29.1%) who worked in telecom services. For the Ethiopian participants, the average age was 32, with 21 being the lowest age and 55 the highest. Average work experience was 5.6 years. In terms of educational qualifications, four (2.1%) had a diploma, 110 (74.8%) a first degree, 31 (21.1%) a second degree, and 2 (1.4%) of them were third degree holders. With regard to their work position, 129 (87.8%) worked as staff, while 12 (8.2%) and 6 (4.8%) of the Ethiopian participants worked as team leaders and department heads respectively. Most of (80%) the Ethiopian participants work for a telecom service company.

4.2. Measures

The study variables were measured using extensively used and validated instruments.

4.2.1. Leadership style

To measure the three leadership styles, participants ' impressions of the leadership behavior of their immediate supervisor were retrieved using the short form of the Multi-Factor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ-5X), a measure built based on the full range leadership model of Avolio and Bass (Avolio et al., 1999) and commonly used and evaluated in different cultures (Trottier et al., 2008; Solomon, 2016). The short form of the MLQ 5X consists of 36 items measuring nine outcomes of leadership: idealized influence (attributed), idealized influence (behavioral), inspirational motivation, individualized consideration, intellectual stimulation, contingent rewards, management-by-exception (active), management-by-exception (passive), and laissez-faire. The response are rated using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “not at all” to 4 “frequently, if not always.”

4.2.2. Work engagement

The UWES which was initially designed by Schaufeli et al., 2002a, Schaufeli et al., 2002b and subsequently reviewed by Schaufeli et al. (2006), has been used to measure the level of work engagement of the individual employees The scale was validated in many studies (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2010) and utilized in non-Western countries such as South Korea (Kim, 2014; Song et al., 2012). The short form of UWES is called the UWES-9; it has nine items, three for each dimension: vigor, dedication, and absorption. It is a self-report scale. All items of the UWES-9 were presented with a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“never”) to 6 (“always”). Through analyzing data from various countries via CFA and test-retest reliability, Schaufeli et al. (2006) reported that the Cronbach's alpha for the UWES-9 ranged between 0 .85 and 0.92. Besides, other studies also confirmed its acceptable applicability in terms of the items' homogeneity and the construct factor structure (e.g., Park et al., 2013; Seppala et al., 2009).

4.2.3. Innovative work behavior

Innovative work behavior was measured using Janssen (2000) 9-item test with a 7-point Likert scale ranging from (1) “never” to (7) “always.” The instrument measures three aspects of innovative work behavior: breeding a new idea, gaining support from others for its implementation, and turning an idea into an application. The respondents were asked how often creative tasks relevant to these three fields were performed. To create measure of innovative work behavior, scores of the three aspects were summed up. With respect to its internal consistency, Agarwal et al. (2012), reported Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.92.

4.2.4. Task performance

In order to assess in-role task performance, a three-item self-report scale which is utilized widely in recent studies (e.g., Kim, 2014), has been used. Responses were recorded on seven-point Likert scale ranging from (1) “strongly disagree” to (7) “strongly agree.” Drawing on review of different studies that had employed the scale, Kim (2014) reported its reliability ranging from 0.77 to 0.87.

All the scales that became part of the questionnaire used in this analysis were in English. Hence, to suit the current study, forward-then-backward translation procedures (English to Amharic and English to Korean) were performed on all instruments by independent bilingual professionals. This procedure ensures linguistic equivalence between the original language of the instrument and the language used for its administration (McGorry, 2000).

4.3. Data analysis

In order to examine the data, descriptive statistics, Cronbach's alpha, Pearson's product momentum correlation, and linear multiple regression analysis were employed. To assess the amount of variability explained by the predictors, coefficient of determination (R2) and to determine the magnitude of the path effects, standardized path coefficient estimates were considered. For the sake of comparison, analyses were made for the two national samples separately.

Prior to the analyses, basic assumptions of multivariate data analysis such as normality, linearity, and multicollinearity were tested. Data from the two national samples showed approximately normal distributions. The assumption of linearity was also met. With respect to multicollinearity, the high bivariate correlation between transformational leadership style and transactional leadership style, particularly for South Korean participants, resulted in a relatively high variance inflation factor (VIF) of 5.33 for the variable transactional leadership worrisome as per the suggestion by Hair et al. (2010).

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive analyses

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for the variables included in the study are presented in Table 1. The bivariate correlations are indicated by a Pearson's product momentum correlation coefficient (r). Among the background factors, weak negative correlations between sex and work engagement (r = - 0.18, p < 0.01) and sex and task performance (r = -0.17, p < 0.01) were obtained for the South Korean sample, while for Ethiopia they failed to reach significance. Work position was weakly negatively correlated with work engagement (r = -0.22, p < 0.01 for South Korea and r = -0.16, p < 0.05 for Ethiopia) and innovative work behavior (r = -0.19, p < 0.01 for South Korea and r = -0 .24, p < 0.01 for Ethiopia). Transformational and transactional leadership styles were positively correlated with work engagement and indicators of work outcomes in both countries, with the exception of the relationship between the transactional leadership style and work engagement in Ethiopia, which failed to reach significance. Laissez-faire leadership was weakly positively correlated with work engagement (r = 0.13, p < 0.05) and innovative work behavior (r = 0.17, p < 0.01) in South Korea, while in Ethiopia it was negatively correlated with work engagement (r = -0.21, p < 0.05) and innovative work behavior (r = -0.16, p < 0.05). Its correlation with task performance failed to reach the significance level in both countries. Work engagement was moderately positively related with measures of outcome indicators —innovative work behavior (r = 0.57, p < 0.01, and r = 0.66, p < 0.01) and task performance (r = 0.46, p < 0.01, and r = 0.54, p < 0.01) for Ethiopia and South Korea, respectively. With respect to internal consistency, all measures for both samples demonstrated traditionally acceptable internal reliability levels (α ranged from 0.77 to 0.95).

Table 1.

Bivariate correlation, mean (M), standard deviation (SD), and internal consistencies (Cronbach'sα) of the study variables for the South Korean (n = 291) and Ethiopian (n = 147) samples.

| M | SD | α value | Age | Gender | Education | Work position | Work Experience | TRF | TRA | LAF | WE | IWB | TP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | 31.6 | 1.33 | 2.21 | 2.84 | 5.63 | 2.59 | 2.42 | 1.94 | 4.82 | 3.75 | 4.92 | ||||

| SD | 5.75 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 3.73 | 0.77 | 0.66 | 1.04 | 1.05 | 1.21 | 0.96 | ||||

| α value | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.77 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.88 | |||||||||

| Age | 36.56 | 5.50 | 1 | -0.24∗∗ | 0.27∗∗ | -0.09 | 0.49∗∗ | -0.23∗∗ | -0.18∗ | 0.02 | -0.12 | -0.12 | -0.11 | ||

| Gender | 1.21 | 0.41 | -0.30∗∗ | 1 | -0.10 | 0.22∗∗ | -0.17∗ | 0.18∗ | 0.10 | -0.04 | 0.13 | -0.04 | 0.01 | ||

| Education | 2.13 | 0.52 | 0.11∗ | -0.05 | 1 | -0.23∗∗ | 0.29∗∗ | -0.08 | -0.03 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.09 | ||

| Work position | 2.58 | 0.58 | -.43∗∗ | 0.09 | -0.19 | 1 | -0.05 | -0.13 | -0.17∗ | -0.15 | -0.16∗ | -0.24∗∗ | -0.13 | ||

| Work Experience | 6.96 | 4.79 | 0.63∗∗ | -0.17∗∗ | 0.02 | -0.38∗∗ | 1 | -0.23∗∗ | -0.18∗ | -0.10 | -0.21∗∗ | -0.05 | -0.09 | ||

| TRF | 3.19 | 0.70 | 0.95 | -0.002 | -0.09 | -0.03 | -0.10 | -0.01 | 1 | 0.51∗∗ | -0.26∗∗ | 0.52∗∗ | 0.53∗∗ | 0.41∗∗ | |

| TRA | 3.13 | 0.61 | 0.84 | 0.03 | -0.14∗ | -0.01 | -0.22∗∗ | -0.10 | 0.84∗∗ | 1 | 0.25∗∗ | 0.16 | 0.31∗∗ | 0.36∗∗ | |

| LAF | 2.73 | 0.88 | 0.79 | 0.07 | -0.01 | 0.07 | -0.16∗∗ | 0.068 | 0.06 | 0.35∗∗ | 1 | -0.21∗ | -0.16∗ | -0.14 | |

| WE | 4.62 | 1.02 | 0.93 | 0.11 | -0.18∗∗ | 0.05 | -0.22∗∗ | 0.11 | 0.59∗∗ | 0.57∗∗ | 0.13∗ | 1 | 0.57∗∗ | 0.46∗∗ | |

| IWB | 4.42 | 1.10 | 0.94 | 0.10 | -0.17∗∗ | 0.02 | -0.19∗∗ | 0.06 | 0.71∗∗ | 0.68∗∗ | 0.17∗∗ | 0.66∗∗ | 1 | 0.53∗∗ | |

| WP | 4.87 | 1.03 | 0.86 | 0.13∗ | -0.04 | -0.03 | -0.10 | 0.10 | 0.42∗∗ | 0.41∗∗ | -0.04 | 0.54∗∗ | 0.57∗∗ | 1 | |

Notes: ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01 (two tailed).

The coding scheme was as follows: Gender: 1 = male, 2 = female; Education: 1 = diploma, 2 = BSc, 3 = MSc, 4 = PhD; work position: 1 = director/division head/assistant head, 2 = team leader, 3 = staff.

TRF - transformational, TRA - transactional, LAF - laissez-faire, WE - work engagement, IWB - innovative work behavior, TP - task performance.

Values below the diagonals are correlation coefficients for the South Korean sample, while those above the diagonals are values for the Ethiopian sample, along with internal consistency measures (Cronbach's alpha values).

5.2. Influence of leadership styles on work-related behaviors

To ascertain the proposed hypotheses related to the relationships between leadership styles and the measures of work outcomes and work engagement, a series of multiple linear regression analyses was performed, in which each indicator of work outcomes and work engagement was regressed on styles of leadership consecutively for the two countries separately. In the analyses, the background variables of the participants were controlled to remove their effects. As shown in Table 2, the outputs indicated that the three leadership styles taken together explained a significant amount of the variability in innovative work behavior (ΔR2 = 0.26, F (8,138) = 8.82, p < 0.01 for Ethiopia; ΔR2 = 0.48, F (8,182) = 47.1, p < 0.01 for South Korea), task performance (ΔR2 = 0.20, F (8,138) = 5.55, p < .0.05 for Ethiopia; ΔR2 = 0.21, F (8,182) = 10.46, p < 0.01 for South Korea), and work engagement (ΔR2 = 0.24, F (8,138) = 8.82, p < 0.01 for Ethiopia; ΔR2 = 0.32, F (8,182) = 23.2, p < 0.01 for South Korea). However, when the path coefficient estimates were taken into account, the path effects of the transformational leadership style on innovative work behavior (β = 0.47, p < 0.01 for Ethiopia; β = 0. 54, p < 0. 01 for South Korea) and work engagement (β = 0.52, p < 0.01 for Ethiopia; β = 0.45, p < 0.01 for South Korea) were significant, while its effect on task performance failed to reach the significance level in both countries. The effect of the transactional leadership style was significant only for task performance (β = 0.29, p < 0. 01 for Ethiopia; β = 0.35, p < 0.01 for South Korea), not for innovative work behavior. Similarly, laissez-faire leadership's negative effect also reached significance level for task performance only (β = -0.19, p < 0.05 for Ethiopia; β = - 0.17, p < 0.01 for South Korea).

Table 2.

Regression results for predicting innovative work behavior, task performance, and work engagement from leadership styles.

| IWB |

TP |

WE |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETH | KOR | ETH | KOR | ETH | KOR | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Age | -0.12 | -0.01 | -0.12 | 0.10 | -0.04 | -0.06 |

| Gender | -0.01 | -0.16 | 0.01 | -0.004 | 0.13 | -0.17∗∗ |

| Education | 0.05 | -0.01 | 0.11 | -0.05 | 0.10 | 0.03 |

| Work position | -0.24 | -0.20 | -0.12 | -0.06 | -0.18∗ | -0.22∗∗ |

| Work experience | -0.02 | -0.04 | -0.06 | -0.02 | -0.20∗ | 0.04 |

| R2 |

0.07 |

0.06∗ |

0.04 |

0.02 |

0.10∗∗ |

0.08∗∗ |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| TRF | 0.47∗∗ | 0.54∗∗ | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.52∗∗ | 0.45∗∗ |

| TRA | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.29∗∗ | 0.35∗∗ | -0.14 | 0.15 |

| LAF | -0.10 | 0.06 | -0.19∗ | -0.17∗∗ | -0.09 | 0.03 |

| ΔR2 | 0.26∗∗ | 0.48∗∗ | 0.20∗∗ | 0.21∗∗ | 0.24∗∗ | 0.32∗∗ |

| R2 total | 0.34∗∗ | 0.54∗∗ | 0.24∗∗ | 0.23∗∗ | 0.34∗∗ | 0.40∗∗ |

| F value for total | 8.82∗∗ | 41.71∗∗ | 5.55∗∗ | 10.46∗∗ | 8.82∗∗ | 23.82∗∗ |

Notes: ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01 (two tailed). ETH - Ethiopia, KOR - South Korea.

The results in Table 2 provided support for H1 (a), H2 (b), H3 (b), and H4 but not for H5 and H6.

To test the hypothesis related to the relationship between work engagement and the measures of work outcomes: innovative work behavior and task performance were regressed on work engagement consecutively and separately for the two countries. The results in Table 3 showed that a significant proportion of the variance in innovative work behavior (ΔR2 = 0.28, F (6,140) = 13.10, p < 0.01 for Ethiopia; ΔR2 = 0.38, F (6,140) = 38.04, p < 0.01 for South Korea) and task performance (ΔR2 = 0.18, F (6,140) = 6.74, p < 0.01 for Ethiopia; ΔR2 = 0. 29, F (6,284) = 21.95, p < 0 .01 for South Korea) were explained by work engagement. The standardized path coefficients of work engagement on innovative work behavior (β = 0.56, p < 0.01 and β = 0.64, p < 0.01) and on task performance (β = 0. 45, p < 0.01 andβ = 0.56, p < 0.01) for Ethiopia and South Korea, respectively, indicated positive and significant relationships of work engagement with innovative work behavior and task performance and thus provided support for H7.

Table 3.

Regression results for predicting innovative work behavior and task performance from work engagement.

| IWB |

TP |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETH | KOR | ETH | KOR | |

| Step 1 | ||||

| Age | -0.12 | -0.01 | -0.12 | 0.10 |

| Gender | -0.01 | -0.16 | 0.01 | -0.004 |

| Education | 0.05 | -0.09 | 0.11 | -0.05 |

| Work position | -0.24 | -0.20 | -0.12 | -0.06 |

| Work experience | -0.02 | -0.04 | -0.06 | 0.02 |

| R2 |

0.07 |

0.06∗∗ |

0.04 |

0.02 |

| Step 2 | ||||

| WE | 0.56∗∗ | 0.64∗∗ | 0.45∗∗ | 0.56∗∗ |

| ΔR2 | 0.28∗∗ | 0.38∗∗ | 0.18∗∗ | 0.29∗∗ |

| R2 total | 0.36∗∗ | 0.45∗∗ | 0.22∗∗ | 0.32∗∗ |

| F value for total | 13.10∗∗ | 38.04∗∗ | 6.74∗∗ | 21.95∗∗ |

Note: ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01 (two tailed).

5.3. Mediational role of work engagement

In testing the hypothesis related to the partial mediational role of work engagement in the link between leadership styles and indicators of outcome behavior, as per Baron and Kenny's (1986) suggestion, certain conditions need to be met for mediation establishment. First, the predictor variable(s) had to be related to the mediator variable. Second, the mediator had to be related to the predicted variable(s). Third, a significant relationship between the predictor variable(s) and predicted variable(s) was to be reduced for partial mediation to operate when controlling for the mediator variable. As described earlier, the first two conditions were partly met. Thus, for the mediation test, the two indicators of work outcomes were regressed over leadership styles consecutively while controlling for background factors and work engagement. As the results in Table 4 showed, the amount of variance in innovative work behavior explained by leadership styles was reduced from 26% to 9% (ΔR2 = 0. 09, F (9,137) = 12.56, p < 0.01) for Ethiopia and from 48% to 16% (ΔR2 = 0.16, F (9,281) = 48.62, p < 0.01) for South Korea, while for task performance reduction was from 20% to 10% (ΔR2 = .10, F (9,137) = 7.63, p < 0.01) for Ethiopia and from 21% to 4% (ΔR2 = 0.04, F (9,281) = 17.44, p < 0.01) for South Korea. Thus, H8 is supported.

Table 4.

Regression results for predicting work outcomes (innovative work behavior and task performance) from leadership styles while controlling work engagement.

| IWB |

TP |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETH | KOR | ETH | KOR | |

| Step 1 | ||||

| Age | -0.09 | 0.03 | -0.10 | 0.14 |

| Gender | -0.09 | -0.05 | -0.05 | 0.09 |

| Education | -0.004 | -0.03 | 0.07 | -0.06 |

| Work position | -0.14 | -0.06 | -0.03 | 0.07 |

| Work experience | 0.09 | -0.07 | 0.03 | -0.005 |

| WE | 0.56∗∗ | 0.64∗∗ | 0.45∗∗ | 0.56∗∗ |

| R2 |

0.36∗∗ |

0.45∗∗ |

0.22∗∗ |

0.32∗∗ |

| Step 2 | ||||

| TRF | 0.25∗ | 0.39∗∗ | 0.01 | -0.06 |

| TRA | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.34∗∗ | 0.28∗ |

| LAF | -0.06 | 0.05 | -0.16 | -0.18∗∗ |

| ΔR2 | 0.09∗∗ | 0.16∗∗ | 0.10∗∗ | 0.04∗∗ |

| R2 total | 0.45∗∗ | 0.61∗∗ | 0.33∗∗ | .36∗∗ |

| F value for total | 12.56∗∗ | 48.62∗∗ | 7.63∗∗ | 17.44∗∗ |

Note: ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01 (two tailed).

With respect to hypothesis 9, (nature of relationships & mediation model across the two national samples), the separately presented results elucidated that the relationships among styles of leadership, work engagement and work outcomes were more or less consistent across Ethiopia and South Korea samples. Work engagement also partly mediated the relationship between leadership styles and work outcomes in both samples. Hence, H9 is supported.

6. Discussion

The present study investigated relationships among leadership styles, employee work engagement and some indicators of work outcomes and tested a mediation model of work engagement in the link between styles of leadership and work outcomes among ICT professionals. The model viewed leadership styles (the behavior of leaders varying from powerful transformation to "non-leadership") as antecedent to work engagement and innovative work behavior and task performance were taken as work outcomes. It also investigated the nature of relationships among variables and cross-national validity of the proposed model in two independent samples from Ethiopia and South Korea, countries that differ in their social, cultural, economic, and technological levels. The obtained results were as follows:

First, the transformational leadership style had significant positive relationships with employees' work engagement and innovative work behavior, while the transactional leadership style had a significant positive relationship with employee task performance. Laissez-faire leadership had a significant negative relationship with task performance. These associations were consistent across the two national samples. The assumed positive links of transformational leadership style with task performance and transactional leadership style with employees’ innovative work behavior, and the negative relationship of the laissez-faire style with innovative behavior were not supported in both national samples. The relationships obtained have shown that leaders who stimulate and inspire followers by articulating visions, goals, and shared values and engaged in building capacity via coaching and challenging employees promote innovative behavior, while leaders who emphasize compliance of followers through supervision may have influence on task performance.

Second, as expected, work engagement had significant positive relationships with the indicators of work outcomes (innovative work behavior and task performance) among ICT professionals in both countries. This suggests that, employees who psychologically identify with their work or “bring in” their personal selves to work, devoting and experiencing an emotional connection to their work, appear to be innovative and put discretionary effort into performance of tasks.

Third, work engagement partially mediated the relationships between leadership styles and indicators of outcomes. Specifically, the relationship between transformational leadership and professionals’ innovative work behavior was partially mediated by work engagement in both countries. This implies that transformational leaders influence innovative behavior of staff directly and indirectly through influencing their level of work engagement.

Work outcomes such as task performance and innovative work behavior are influenced by a number of factors of which leadership is an important one. Consistent to current study results, previous studies (e.g. Khan et al., 2012; Ejere and Abasilim, 2013; Judge and Piccolo, 2004; Solomon, 2016) underscored the significant contributions of transactional and transformational styles of leadership for employees’ performance.

Specifically, the association of transformational leadership style with innovative work behavior and transactional leadership style with task performance observed in the current study may be explained in terms of peculiar characteristics of these styles. With respect to innovative work behaviour, transformational leadership style is considered as a suitable style of leadership as in this style followers are encouraged to commence new ideas and challenge old ways of doing things (Bass and Avolio, 2000). For innovative behaviour transformational leaders' behaviour such as being role model by engaging in needed change, stimulating followers to challenge the status quo and be inspirational while leading others are all vital qualities. In addition, transformative leadership style demanding alignment of the needs and desires of followers with the organization's one (Bass, 1999), may encourage employees to go additional mile necessary for creative behaviour. On the other hand, transactional leadership can be argued to be significant for task performance of employees' as it is focused more on immediate outcomes, monitor performance and correct mistakes. Additionally, transactional leaders make clear expectations and give feedback about meeting expectations may push employees to focus on tasks listed in job description.

The findings related to linkages among leadership styles, work engagement and work outcomes obtained in the current study are also consistent with some earlier studies (e.g.,Bakker and Bal, 2010; Salanova et al., 2011; Song et al., 2012). Bakker and Bal (2010) reported on weekly work engagement as a predictor of performance among starting teachers. With respect to leadership styles, Song et al. (2012) affirmed the significant impact of transformational leadership on employee work engagement and organizational knowledge creation practices, and partial mediation of employee work engagement in the link between those two constructs. Salanova et al. (2011) also reported a relationship between transformational leadership and work engagement where, contrary to the findings of the current study, work engagement fully mediated the relationship between transformational leadership and nurses’ extra-role performance.

The observed mediation of work engagement across independent samples found in the current study is also consistent with some previous studies (Dorfman et al., 1997; Walumbwa et al., 2005; Salanova and Schaufeli, 2008). While the consistency of the mediation model observed here across the two independent national samples does not justify either its utility or its contribution, it may add confidence in the generalizability of the findings.

6.1. Implications

The results of this study have some theoretical and practical implications in HR-related fields for researchers and practitioners. The study provides insights into the ongoing investigations of correlates of employees' work engagement. In particular, the study may shed light on the nature of associations among leadership styles, work engagement, and critical work outcomes such as task performance and innovative work behavior among ICT professionals. It may also disentangle the role of transformational leadership, particularly when it comes to employees personally committing themselves to role performance and innovation efforts. Besides, the study elucidated the cross-national aspect of the relationships among the variables it considered. Despite a number of background differences, it appeared that styles of leadership had more or less similar links with work engagement and outcome behaviors among participants from Ethiopia and South Korea. Specifically, the invariance in the mediating role of work engagement in the link between transformational leadership and employees’ discretionary actions with respect to idea generation, promotion, and realization among ICT professionals working in different countries solidify the existing understanding of the importance of this leadership style.

Practically, the results of the study highlight the need to improve leadership by applying a transformational style, as it is essential for organizations to have ICT workforces that perform their roles and are willing to demonstrate discretionary efforts. Thus, practitioners in the field should develop strategies and training programs targeting transformational leadership skills such as being supportive and intellectually stimulating, and conveying a vision to employees so that leaders can influence their staff. In particular, to strengthen the ICT sector's human resources in Ethiopia so that it can contribute significantly to the development of the country, more attention should be given to leadership development.

Furthermore, practitioners could closely scrutinize employees' work engagement by assessing it using well-established scales such as the UWES or a locally developed one. For ICT companies to be competitive, collecting information on the work engagement level of staff should be part of employees' opinion surveys, and identifying practices and policies that promote their staff's work engagement behavior is imperative.

6.2. Limitations and future research

Notwithstanding its important theoretical and practical contributions, there are some drawbacks to this study. The cross-sectional research design used primarily did not allow researchers to establish causality among variables. This means that the suggested associations among the variables should not be interpreted as causal relationships, but as associations that suggest causal ordering, which needs to be confirmed by longitudinal research. Secondly, the data for the study were gathered using a self-report questionnaire with its own inherent pros and cons, particularly when it comes to the participants’ assessments of their immediate supervisor. Thirdly, as antecedent variables, the study limited to full range of leadership model consists of transformational, transactional and laissez fair styles. That is, there are also other potential aspects of leadership nature that might be relevant that are not included in the current study. Finally, the relatively high VIF of the transactional leadership style could undermine the role of this variable in the web. Thus, for future research, the researchers suggest a longitudinal research design and outcomes measured through methods other than self-reports.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Habtamu Kebu Gemeda, Jaesik Lee: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Agarwal U.A., Datta S., Blake-Beard S., Bhargava S. Linking LMX, innovative work behavior and turnover intentions: the mediating role of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2012;17(3):208–230. [Google Scholar]

- Ardichvili A., Kuchinke K.P. Leadership styles and cultural values among managers and subordinates: a comparative study of four countries of the former Soviet Union, Germany, and the US. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2002;5(1):99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio B.J., Bass B.M., Jung D.I. Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1999;72:441–462. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A.B., Bal P.M. Weekly work engagement and performance: a study among starting teachers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010;83(1):189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A.B., Demerouti E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008;13(3):209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Baron R.M., Kenny D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass B.M. Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 1999;8:9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bass B.M., Avolio B.J. Sage Publications Inc; Thousand Oaks: 1994. Improving Organizational Effectiveness: through Transformational Leadership. [Google Scholar]

- Bass B.M., Avolio B.J. second ed. Mind Garden; Redwood City, CA: 2000. Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Bass B.M., Riggio R.E. second ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; London: 2006. Transformational Leadership. [Google Scholar]

- Batista-Taran L.C., Shuck M.B., Gutierrez C.C., Baralt S. The role of leadership style in employee engagement. In: Plakhotnik M.S., Nielsen S.M., Pane D.M., editors. Proceedings of the Eighth Annual College of Education & GSN Research Conference. Florida International University; Miami: 2009. pp. 15–20.http://coeweb.fiu.edu/research_conference/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Beyene K.T., Shi C.S., Wu W.W. Linking culture, organizational learning orientation and product innovation performance: the case of Ethiopian manufacturing firms. Afr J. Ind. Eng. 2016;27(2):88–101. [Google Scholar]

- Carasco-Saul M., Kim W., Kim T. Leadership and employee engagement proposing research agendas through a review of literature. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2015;14(1):38–63. [Google Scholar]

- Chughtai A.A. Linking affective commitment to supervisor to work outcomes. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013;28(6):606–627. [Google Scholar]

- Compare Countries-Hofstede Insights https://www.hofstede-insights.com/product/compare-countries/ n.d., Wikipedia.

- Demerouti E., Cropanzano R. From thought to action: employee work engagement and job performance. In: Bakker A.B., Leiter M.P., editors. Vol. 65. 2010. pp. 147–163. (Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research). [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman P.W., Howell J.P., Hibino S., Lee J.K., Tate U., Bautista A. Leadership in Western and Asian countries: communalities and differences in effective leadership processes across cultures. Leader. Q. 1997;8(3):233–274. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn M.W., Dastoor B., Sims R.L. Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: a cross-cultural perspective. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2012;4(1):45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ejere E.I., Abasilim U.D. Impact of transactional and transformational leadership styles on organizational Performance: empirical Evidence from Nigeria. J. Commer. 2013;1(5):30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ethiopia. 2018. Retrieved on 5th March, 2018, from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- Evelyn D., Hazel G. Effects of transformational leadership on employee engagement: the mediating role of employee engagement. Int. J. Manag. 2015;6(2):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Black W.C., Babin B.J., Anderson R.E. seventh ed. Pearson; New York: 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Harter J.K., Schmidt F.L., Hayes T.L. Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: a meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002;87(2):268–279. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward B.A., Davidson A.J., Pascoe J.B., Tasker M.L., Amos T.L., Pearse N.J. Paper Presented at the Society for Industrial and Organisational Psychology 6th Annual Conference, 25-27 June 2003, Sandton, Johannesburg. 2003. The relationship between leadership and employee performance in a South African pharmaceutical company. [Google Scholar]

- International Monitory Fund . 2016. Country Report, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2016/cr16322 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen O. Job demands, perceptions of effort-reward fairness, and innovative work behavior. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000;73:287–302. [Google Scholar]

- Jeung C.W. The concept of employee engagement: a comprehensive review from a positive organizational behavior perspective. Perform. Improv. Q. 2011;24:49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Judge T.A., Piccolo R.F. Transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analytic test of their relative validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004;89(5):755–768. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990;33(4):692–724. [Google Scholar]

- Khan M.J., Aslam N., Riaz M.N. Leadership styles as predictors of innovative work behavior. Pak. J. Clin. Psychol. 2012;9(2):17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kim W. The Pennsylvania State University; 2014. An Examination of Work Engagement in Selected Major Organizations in Korea: its Role as a Mediator between Antecedents and Consequences.https://etda.libraries.psu.edu/files/final_submissions/9386 Dissertation. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Koech P.M., Namusonge G.S. The effect of leadership styles on organizational performance at state corporations in Kenya. Int. J. Bus. Commer. 2012;2(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter J.P. The Free Press; New York: 1988. The Leadership Factor. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C., Leitier M.P. first ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1997. The Truth about Burnout: How Organizations Cause Personal Stress and what to Do about it. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C., Schaufeli W.B., Leiter M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001;52(1):397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry S.Y. Measurement in a cross-cultural environment: survey translation issues. Qual. Market Res. 2000;3(2):74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer M., Botha E. Butterworths; Durban: 2000. Organizational Development & Transformation in South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Nasbary D.K. Allyn& Bacon; Boston: 2000. Survey Research and the World Wide Web. [Google Scholar]

- Park Y.K., Song J.H., Yoon S.W., Kim J. Learning organization and innovative behavior: the mediating effect of work engagement. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2013;38:75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Pourbarkhordari1 A., Zhou E.H., Pourkarimi J. How Individual-focused transformational leadership enhances its influence on job performance through employee work engagement. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2016;11(2):249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Ramoorthy N., Flood J., Slattery T.F., Sardessai R. The impact of human resource management practices on perceptions of organizational performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2005;19:959–971. [Google Scholar]

- Rich B.L., Lepine J.A., Crawford E.R. Job engagement: antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010;53(3):617–635. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins S.P., Judge T.A., Sanghi S. Dorling Kindersley pvt.Ltd; New Delhi: 2009. Organizational Behavior (13ed) [Google Scholar]

- Rothbard N.P. Enriching or depleting? The dynamics of engagement in work and family roles. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001;46(4):655–684. [Google Scholar]

- Saks A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006;21(7):600–619. [Google Scholar]

- Salanova M., Lorente L., Chambel M.T., Martinez I.M. Linking transformational leadership to nurses’ extra-role performance: the mediating role of self-efficacy and work engagement. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011;67(10):2256–2266. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salanova M., Schaufeli W.B. A cross-national study of work engagement as a mediator between job resources and proactive behavior. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008;19(1):116–131. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli W.B., Bakker A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004;25(3):293–315. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli W.B., Bakker A.B. Defining and measuring work engagement: bringing clarity to the concept. In: Bakker A.B., Leiter M.P., editors. Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research. Psychology Press; New York, NY: 2010. pp. 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli W.B., Bakker A.B., Salanova M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: a cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006;66(1):701–716. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli W.B., Martínez I., Marques-Pinto A., Salanova M., Bakker A.B. Burnout and engagement in university students: a cross-national study. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2002;33:464–481. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli W.B., Salanova M., González-Romá V., Bakker A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two-sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002;3(1):71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon S. Addis Ababa University; 2016. The Relationship between Leadership Styles and Employees’ Performance in Selected Sub-city Education Offices of Addis Ababa City Administration. Unpublished master thesis submitted to. [Google Scholar]

- Seppala P., Mauno S., Feldt T., Hakanen J., Kinnunen U., Tolvanen A., Schaufeli W. The construct validity of the Utrecht work engagement scale: multi sample and longitudinal evidence. J. Happiness Stud. 2009;10(4):459–481. [Google Scholar]

- Shahin A.I., Wright P.L. Leadership in the context of culture: an Egyptian perspective. Leader. Organ. Dev. J. 2004;25(6):499–511. [Google Scholar]

- Song J.,H., Kolb J.A., Lee U.H., Kim H.K. Role of transformational leadership in effective organizational knowledge creation practices: mediating effects of employees’ work engagement. Human Dev. Q. 2012;23(1):65–101. [Google Scholar]

- South Korea. 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Korea Retrieved on 5th March, 2018, from Wikipedia: [Google Scholar]

- Trottier T., Van Wart M., Wang X. Examining the nature and significance of leadership in government organizations. Publ. Adm. Rev. 2008;68(2):319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent-Höper S., Muser C., Janneck M. Transformational leadership, work engagement, and occupational success. Career Dev. Int. 2012;17:663–682. [Google Scholar]

- Walumbwa F.O., Lawler J.L., Avolio B.J. Leadership, individual differences, and work-related attitudes: a cross-culture investigation. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2007;56(2):212–230. [Google Scholar]

- Walumbwa F.O., Orwa B., Wang P., Lawler J.J. Transformational leadership, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction: a comparative study of Kenyan and U.S. financial firms. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2005;16(2):235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Wasbeek D.J. Dissertation; Robert Kennedy College: 2004. Human Resource Management Practices in Selected Private Companies: A Study to Increase Employee Productivity in Ethiopia.www.bookpump.com/dps/pdf-b/1122446b.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulou D., Bakker A.B., Demerouti E., Schaufeli W.B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007;14(2):121–141. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulou D., Bakker A.B., Demerouti E., Schaufeli W.B. Work engagement and financial returns: a diary study on the role of job and personal resources. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009;82(1):183–200. [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Thomas H. How can leaders achieve high employee engagement? Leader. Organ. Dev. J. 2011;32:399–416. [Google Scholar]

- Yim H. Cultural identity and cultural policy in South Korea. Int. J. Cult. Pol. 2002;8(1):37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.M., Bartol K.M. Linking empowering leadership and employee creativity: the influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 2010;53:107–128. [Google Scholar]