Abstract

Objective

The insula consists of functionally diverse subdivisions, and each division plays different roles in schizophrenia neuropathology. The current study aimed to investigate the abnormal patterns of dynamic functional connectivity (dFC) of insular subdivisions in schizophrenia and the effect of antipsychotics on these connections.

Methods

Longitudinal study of the dFC of insular subdivisions was conducted in 42 treatment-naive first-episode patients with schizophrenia at baseline and after 8 weeks of risperidone treatment based on resting-state functional magnetic resonance image (fMRI).

Results

At baseline, patients showed decreased dFC variance (less variable) between the insular subdivisions and the precuneus, supplementary motor area and temporal cortex, as well as increased dFC variance (more variable) between the insular subdivisions and parietal cortex, compared with healthy controls. After treatment, the dFC variance of the abnormal connections were normalized, which was accompanied by a significant improvement in positive symptoms.

Conclusions

Our findings highlighted the abnormal patterns of fluctuating connectivity of insular subdivision circuits in schizophrenia and suggested that these abnormalities may be modified after antipsychotic treatment.

Keywords: schizophrenia, insular subdivision, resting-state fMRI, dynamic functional connectivity, antipsychotic medication

Introduction

The insula is a critical structure with extensive connections to the cortex and limbic system, and it plays important roles in diverse functions including consciousness, interoception, motor control, emotion, and interpersonal experience.1,2 In particular, the often-observed coactivation of the insula and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) across a variety of cognitive tasks suggests an intrinsic network involving these 2 regions, known as salience network. The salience network is crucial for detecting salient external stimuli and internal mental events, and for switching brain states from the default mode to the task-related activity mode.3 Insular dysfunction in the context of the salience network may contribute to many of the clinical features of psychosis by diminishing the capacity of the brain to discriminate between self-generated and external information.4–7 Studies in large samples have shown transdiagnostic abnormality of the salience network across a wide variety of mental illnesses,8 suggesting the possibility that some interventions that target the salience network may prove of broad implication across psychopathology.

The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia proposes that eventual formation of this disease results from dopamine dysfunction interacting with sociocultural milieu.9 Antipsychotic drugs play a key part in dopamine pathway and mainly act on dopamine (DA) and serotonin (5-HT2A) receptors in cortical regions. The insula receives strong dopaminergic innervation and contains a high density of D1 dopamine receptors.10 Numerous studies have provided clues about the association between the insula and antipsychotic treatment, although evidence is very conflicting. For instance, Sarpal et al11 found that increased connectivity between the anterior insula and ventral putamen was associated with improvement in symptoms after 12 weeks of risperidone treatment. Wang et al12 revealed decreased functional connectivity in the insula of schizophrenia patients after 6–8 weeks of antipsychotic treatment, but the altered connectivity was not associated with the relief of psychiatric symptoms. These inconsistent findings may be due to the heterogeneity of the insula, which demonstrates that the insula can be functionally and cytoarchitectonically divided into several subdivisions,13–15 and atypical engagement of different subdivision contributes to different aspects of schizophrenia.5,15–18

Recent developments in dynamic functional connectivity (dFC) have revealed that human brain activity is time varying and relates to the ongoing rhythmic activity. Thus, time-averaged or static connectivity may provide limited information on the functional organization of brain circuits in association with the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders.19–25 For example, previous studies demonstrated that static functional connectivity is insufficient for discriminating connection patterns specific to schizophrenia from bipolar disorder, but dFC robustly separates the 2 disorders.26,27 dFC has also been used to investigate the dynamic interactions of large-scale networks in patients with schizophrenia, demonstrating that dysregulated brain dynamics among the salience network and default-mode network are robust features of schizophrenia.28,29

Based on previous evidence, we hypothesized that abnormal dynamic connectivity patterns of insular subdivisions can be found in schizophrenia, and that the fluctuating connections of each subdivision may be modified after antipsychotic treatment. To test this hypothesis, we first compared treatment-naive first-episode schizophrenia patients with healthy controls to investigate the abnormal patterns of the dFC of insular subdivisions. We then conducted a longitudinal study to determine whether the dFC of insular subdivisions was modified after antipsychotic treatment by comparing schizophrenia patients at baseline and after 8 week treatment. Finally, we performed a correlation analysis to explore the relationship between the changes in dFC variance and the reduction in positive symptoms.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Forty-two individuals with schizophrenia were recruited from the Second Affiliated Hospital, Xinxiang Medical University, China, from October 2012 to January 2014. Schizophrenia diagnosis was made using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR, patient version (SCID-I/P) by 2 trained psychiatrists. All the patients met the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, and had less than 1 year of illness duration since the onset of psychotic symptoms. All patients did not have any form of antipsychotic treatment before this study was conducted. The symptom severity of all patients was measured using the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS). Thirty-eight age-, gender-, handedness-, years of education-matched healthy volunteers were recruited through advertising. All healthy controls had neither psychiatric illness evaluated using the SCID-Non-Patient Version nor had any first-degree relative with a family history of psychiatric illness. Moreover, all participants in our study had no history of drug abuse and neurological disorder, and they were all right-handed. After head motion exclusion, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data from 39 patients at baseline (SZ0W), 34 patients at follow-up (SZ8W), and 34 healthy controls (HC) were analyzed (for detailed information, please see supplementary materials).

Medication and Clinical Assessments

In the current study, we used risperidone as a proxy for antipsychotic drugs with dopamine-antagonist and serotonin-antagonist actions.30 Risperidone is an atypical antipsychotic widely used in schizophrenia treatment,31 and it is known to inhibit dopaminergic D2 receptors and serotonergic 5-HT2A receptors in the brain. According to several guidelines for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, the sufficient treatment duration is about 6–10 weeks during the acute phase of treatment.32–34 Clinically, 8-week treatment for patients is a common treatment time during the acute phase of the disease. Accordingly, all patients with schizophrenia received risperidone treatment at a dosage of 4–6 mg/day for 8 weeks. Mood stabilizers and antidepressants were excluded. The efficacy and safety of risperidone were evaluated every week through clinical interviews. Throughout the 8-week treatment, no serious adverse effects were observed. The symptom severity of all patients was assessed at baseline and followed-up with the 30-item PANSS.

Ethic Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and healthy controls. All examinations were performed under the guidance of the Declaration of Helsinki 1975.35 This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital and the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xinxiang Medical University.

Data Acquisition

Resting-state fMRI data were acquired on a 3T Siemens MRI scanner (Siemens Verio, Erlangen, Germany). Patients were scanned both at baseline and follow-up, whereas healthy volunteers underwent scanning only once. Participants were instructed to keep their eyes closed but should not fall asleep throughout the entire scan. Gradient-echo echo-planar imaging was conducted with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 2000 ms, echo time (TE) =30 ms, flip angle = 90°, field of view = 240 × 240 mm2, matrix size = 64 × 64, 240 volumes, slice thickness = 3 mm, slice gap = 0, voxel size = 3.75 × 3.75 × 3 mm3, and a total of 8 min. Considering the effect of circadian rhythm on resting-sate fMRI, we performed fMRI scanning between 3 pm and 5 pm on weekdays. The scanning times for the patient and control groups were randomized.

Image Preprocessing

Resting-state fMRI images were preprocessed using the toolbox for Data Processing &Analysis of Brain Imaging (DPABI, http://rfmri.org/DPABI). The first 10 volumes were discarded to avoid nonequilibrium effects of magnetization, and slice timing and realignment correction were performed for the remaining images. Any participant with maximum head movement greater than 2.0 mm translation or more than 2.0° rotation was not included. Data were further normalized to the EPI template (resampled voxel size of 2 mm × 2 mm × 2 mm). Then, several covariates including Fristion 24 motion parameters, the cerebrospinal fluid, and white matter signals were regressed as nuisance variables to reduce spurious variance. Afterwards, spatial smoothing (full width at half maximum = 6 mm), detrending, and band-pass filtering (0.01–0.08 Hz) were conducted. Finally, we used AFNI’s 3dDespike algorithm to remove the outlier. This approach was similar to the “scrubbing” method in which signal spikes larger than the absolute median deviation is substituted by a third-order spline fit to clean parts of neighboring data. This technique has the advantages of lack of volume deletion and retention of temporal information for the sliding-window approach.36,37

Definition of Insular Subdivision

Three bilateral insular subdivisions were defined from a seminal study by Deen et al38 who parcelated the human insular lobe based on the clustering of functional connectivity patterns. Cluster analysis revealed 3 subregions of the insula for both left and right hemispheres: ventral anterior insula (vAI), dorsal anterior insula (dAI), and posterior insula (PI). The boundaries between the 3 bilateral insular regions have been described by Deen et al.38 The 3 bilateral subdivisions were then anatomically mapped to the Montreal Neurological Institute 152 standard space. The mean time series of all voxels in the insular subdivisions was regarded as seeds for the subsequent whole-brain dFC analysis in HC, SZ0W, and SZ8W.

dFC Analysis

The sliding window correlation approach, which captures the correlations between time series over specific time ranges, was used to calculate the dFC maps.39 First, the dynamic brain connectivity (DynamicBC) toolbox40 was used to compute seed-based dFC maps. Here, the sliding window method was utilized. The window size was set as 50 TR according to a previous study, and the step was set as 5 TR yielding 37 windows. For each seed region of interest (ROI) at each sliding window, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient between the mean signals of seed ROI with signals of other voxels. Then, for each seed ROI, 37 dFC maps were obtained. For all dFC maps, Fisher’s z-transformation was applied to convert the dFC values into normal distribution. For each subject, we measured the dFC variance of each voxel by calculating the standard deviation of dFC value across time. The dFC variance map of each seed ROI was then obtained for each subject.

Group-Level Dynamic Analysis

We performed group-level statistics on the dFC variance map of all 6 seed ROIs in healthy controls, patients at baseline, and follow-up. For each ROI, 2-sample t test was conducted to compare dFC variance between SZ0W (n = 39) and HC (n = 34) while controlling age, gender, and head motion measured by mean FD value. Paired-sample t test was conducted to evaluate the longitudinal alteration of dFC variance in SZ0W (n = 34) and SZ8W (n = 34). A combination of Bonferroni and AlphaSim corrections was conducted for the comparisons of 6 ROIs. The first step was to correct the comparisons using Bonferroni correction with P < .05, resulting in a correction threshold of P < .008 (0.05/6) for each ROI comparison. The second step was to correct the voxel-wise comparisons within each dFC variance maps of 6 ROIs using AlphaSim correction at P < .008 (a combination of threshold of voxel-level P < .001 and a minimum cluster size threshold). AlphaSim correction was conducted using the AlphaSim program in REST software (http://www.restfmri.net), which applied the Monte Carlo simulation to calculate the probability of false positive detection by taking the individual voxel probability thresholding and cluster size into consideration.41

The mean dFC variance value of the clusters, which showed significant differences either between SZ0W and HC, or between SZ0W and SZ8W, was extracted to conduct a post hoc comparison at the cluster level A correlation analysis was also conducted to examine the relationship between longitudinal alteration of dFC variance (the mean dFC variance value of SZ8W minus the mean dFC variance value of SZ0W) and the reduction of clinical symptoms (the PANSS scores of SZ0W minus the PANSS scores of SZ8W). The threshold of statistical significance was P <.05, Bonferroni correction.

Results

Demographics

Forty-two patients were well matched with 38 HC on age [t(78) = 0.09, P = .929], gender [χ 2(1) = 0.02, P = .888], years of education [t(78) = 0.90, P = .373], alcohol [χ 2(1) = 1.16, P = .282], and tobacco use [χ 2(1) = 0.002, P = .967]. The demographic characteristics of the participants are given in table 1. The average age of patients was 24.86 years (SD = 4.80). The average age at onset of schizophrenia, defined as the time of the first sign of psychiatric symptoms or social withdrawal noticeable by the patient’s relatives or friends was 24.21 years (SD = 4.69; range = 18–37 years). The mean duration since onset of psychiatric symptoms was 8.38 months (SD = 2.61; range = 6–12 months). The demographic and clinical characteristics of participants included for analysis are shown in supplementary table S2.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants

| Variable | SZ0W (n = 42) | SZ8W (n = 42) | HC (n = 38) | Analysisa | Analysisb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | M ± SD | M ± SD | t(df) | P | Effect Size | t(df) | P | Effect Size | |

| Age (years) | 24.86 ± 4.80 | 24.86 ± 4.80 | 24.76 ± 4.56 | 0.09 (78) | .929 | 0.0212 | |||

| Education (years) | 10.48 ± 2.84 | 10.48 ± 2.84 | 11.05 ± 2.91 | 0.90 (78) | .373 | 0.2125 | |||

| Duration of illness (month) | 8.38 ± 2.61 | 8.38 ± 2.61 | |||||||

| PANSS-T | 91.90 ± 11.23 | 67.24 ± 10.10 | 13.19 (41) | <.001 | 3.1990 | ||||

| PANSS-P | 25.60 ± 3.75 | 15.83 ± 3.28 | 14.58 (41) | <.001 | 3.5362 | ||||

| PANSS-N | 18.17 ± 5.21 | 17.07 ± 4.86 | 1.42 (41) | .163 | 0.3444 | ||||

| PANSS-G | 48.14 ± 6.47 | 34.33 ± 4.71 | 13.37 (41) | <.001 | 3.2427 | ||||

| Analysis c | |||||||||

| n | N | n | χ2(df) | P | Effect Size | ||||

| Gender (male/female) | 27/15 | 27/15 | 25/13 | 0.02 (1) | .888 | 0.03 | |||

| Alcohol use | 6 | 6 | 9 | 1.16 (1) | .282 | 0.58 | |||

| Tobacco use | 9 | 9 | 8 | 0.002 (1) | .967 | 0.02 | |||

| Family history of psychiatric illness | 15 | 15 | 0 | ||||||

Note: MRI data of 4 healthy controls and 3 SZ0W fMRI data were excluded due to the head motions, 4 patients failed to complete the follow-up MRI scans, and 3 patients at follow-up were not included due to head motions. Consequently, we collected fMRI data from 39 SZ0W, 34 SZ8W, and 34 HC. Symptom severity of all patients (n = 42) was evaluated both at baseline and follow-up with the 30-item Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). PANSS-T, PANSS total scores; PANSS-P, PANSS positive symptom scores; PANSS-N, PANSS negative symptom scores; PANSS-G, PANSS general psychopathological symptom scores; M, mean; SD, standard deviation; df, degree of freedom. Effect size was measured by Cohen’s d.

aSZ0W vs HC, 2-samples t-test.

bSZ8W vs SZ0W, paired-samples t-test.

cSZ0W vs HC, chi-square test.

Baseline Comparisons of dFC Variance Between Patients and Controls

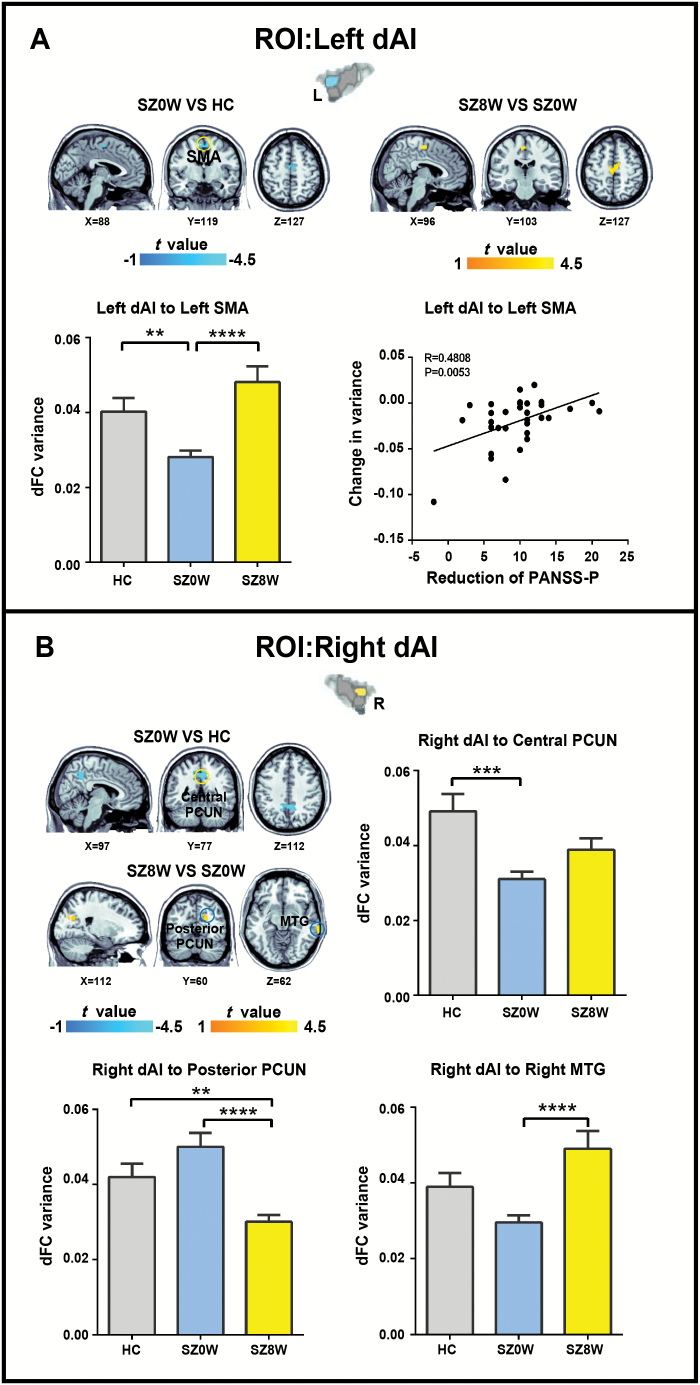

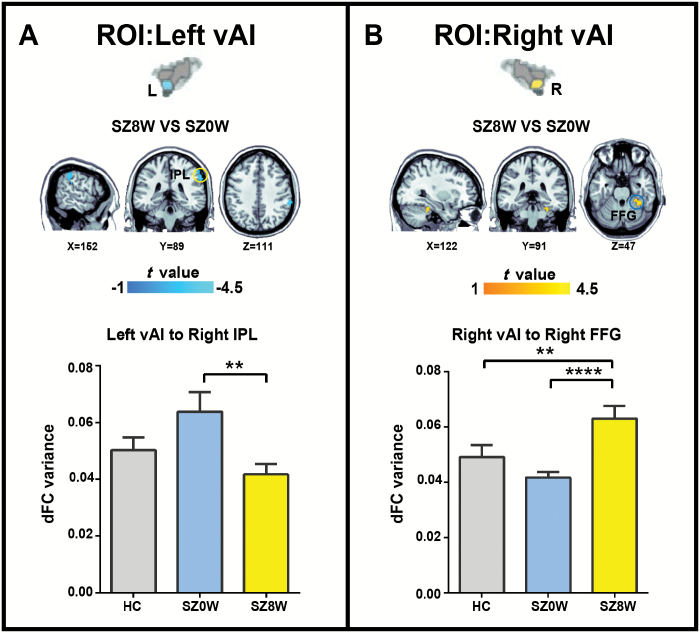

Between-group comparisons on the dFC variance maps revealed decreased dFC variance between the left dAI and supplementary motor area (SMA), right dAI and central precuneus, left PI and left middle temporal gyrus (MTG), left PI and left superior temporal gyrus (STG), right PI and right MTG, and right PI and right precuneus when SZ0W was compared with HC (figures 1–3 and table 2; 2-sample t test; Bonferroni correction at P < .05, combined with AlphaSim correction at P < .008).

Fig. 1.

Group differences in dFC variance for left dAI (A) and right dAI (B) (Bonferroni correction at P < .05, combined with AlphaSim correction at P < .008). The histograms show average dFC variance in the target regions for each group. *P < .01, **P < .005, ***P < .001, ****P < .0005.

Fig. 3.

Group differences in dFC variance analysis for left vAI (A) and vAI (B) (Bonferroni correction at P < .05, combined with AlphaSim correction at P < .008). The histograms show average dFC variance in target regions for each group. *P < .01, **P < .005, ***P < .001, ****P < .0005.

Table 2.

Baseline and Follow-up Comparisons in dFC Variance

| ROI | Brain Regions | Cluster Size | BA | MNI Coordinates (X, Y, Z) | t Value (df) | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SZ0W vs HC | ||||||

| Left dAI | Cluster 1 | 116 | ||||

| Supplementary motor area | 6 | −8, −10, 64 | −3.46 (67) | −0.8118 | ||

| Right dAI | Cluster 1 | 386 | ||||

| Central precuneus | 7 | −16, −66, 44 | −3.56 (67) | −0.8353 | ||

| Left PI | Cluster 1 | 438 | ||||

| Left middle temporal gyrus | 22 | −56, −42, 6 | −2.90 (67) | −0.6804 | ||

| Left superior temporal gyrus | 42 | −60, −44, 16 | −4.88 (67) | −1.145 | ||

| Right PI | Cluster 1 | 186 | ||||

| Right middle temporal gyrus | 21 | 66, −26, −10 | −4.01 (67) | −0.9409 | ||

| Cluster2 | 97 | |||||

| Right precuneus | 7 | 4, −60, 42 | −3.16 (67) | −0.7414 | ||

| SZ8W vs SZ0W | ||||||

| Left dAI | Cluster 1 | 163 | ||||

| Supplementary motor area | 6 | 6, −14, 58 | 3.62 (33) | 1.2416 | ||

| Right dAI | Cluster 1 | 163 | ||||

| Posterior precuneus | 18 | 16, −76, 28 | −5.14 (33) | −1.763 | ||

| Cluster 2 | 88 | |||||

| Right middle temporal gyrus | 21 | 70, −32, −12 | 3.95 (33) | 1.3548 | ||

| Left PI | Cluster 1 | 77 | ||||

| Left middle temporal gyrus | 22 | −56, −36, 6 | 3.65 (33) | 1.2519 | ||

| Left superior temporal gyrus | 42 | −62, −52, 22 | 4.34 (33) | 1.4886 | ||

| Right PI | Cluster 1 | 88 | ||||

| Right middle temporal gyrus | 21 | 68, −20, −2 | 4.63 (33) | 1.5881 | ||

| Cluster 2 | 185 | |||||

| Right precuneus | 7 | 6, −44, 34 | 3.87 (33) | 1.3274 | ||

| Left vAI | Cluster 1 | 241 | ||||

| Right inferior parietal lobule | 40 | 64, −36, 40 | −3.90 (33) | −1.3377 | ||

| Right vAI | Cluster 1 | 118 | ||||

| Right fusiform gyrus | 37 | 38, −46, −16 | 4.21 (33) | 1.444 |

Note: Bonferroni correction at P < .05, combined with AlphaSim correction at P < .008; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; BA, Brodman’s area; vAI, ventral anterior insula; dAI, dorsal anterior insula; PI, posterior insula. Effect size was measured by Cohen’s d.

Follow-up Comparisons of dFC Variance Before and After Treatment

After 8 weeks of risperidone therapy, patients showed increased dFC variance between the left dAI and SMA, right dAI and right MTG, left PI and left STG, right PI and right MTG, right PI and right precuneus, and right vAI and right fusiform gyrus (FFG). Patients showed decreased dFC variance between the right dAI and posterior precuneus, and between left the vAI right inferior parietal lobule (IPL) after antipsychotic treatment (figures 1–3 and table 2; paired-samples t test, Bonferroni correction at P < .05, combined with AlphaSim correction at P < .008).

Fig. 2.

Group differences in dFC variance analysis for left PI (A) and right PI (B) (Bonferroni correction at P < .05, combined with AlphaSim correction at P < .008). The histograms show average dFC variance in target regions for each group. *P < .01, **P < .005, ***P < .001, ****P < .0005.

The unthresholded statistical maps of each comparison can be found at https://neurovault.org/collections/5444/.

Relationships Between the Longitudinal Change of dFC Variance and Clinical Symptoms

To test the relationship between the changes in dFC variance and the reduction of clinical symptoms (measured by the changes in PANSS score before and after treatment), correlation analysis was conducted. We found that with decreased symptoms, the left dAI seed showed increased dFC variance with the left SMA (P < .05, Bonferroni correction; figure 1A). No significant correlation was observed when other seed regions were considered. We also examined the correlation between the change in dFC variance and the improvement in positive symptoms with 8 week accumulated dose of antipsychotic medication, and no significant correlation was observed (Pearson correlation, P < .05, uncorrected).

Discussion

This study used resting-state fMRI to examine the effects of risperidone on the dFC of insular subdivisions in treatment-naive first-episode schizophrenia. At baseline, patients showed decreased dFC variance (less variable) between the insular subdivisions and the precuneus, SMA and temporal cortex, as well as increased dFC variance (more variable) between the insular subdivisions and parietal cortex, compared with healthy controls. After treatment, the dFC variance of abnormal connections were normalized, which was accompanied by a significant improvement in positive symptoms. Additionally, as psychotic symptoms reduced, we observed an increase of dFC variance between the left dAI and SMA in patients. These results indicated the abnormal fluctuating connectivity patterns of insular subdivision circuits in schizophrenia, and these abnormalities may be modified after treatment.

Abnormal dFC Variance of dAI Circuits and the Treatment Effects on These Connections

The dAI is a key node of the salience network, whereas the precuneus is a cardinal node of the default-mode network (DMN). The DMN is typically suppressed during a variety of cognitively demanding tasks and is involved in self-referential and autobiographical processes.42,43 The salience network, on the other hand, is crucial for the detection of salient external stimuli and internal mental events, and through its interactions with task-positive networks and DMN, switching brain states from the default mode to the task-related activity mode.3,15,44 Our finding of decreased dFC variance between the bilateral dAI and precuneus in SZ0W compared with HC may suggest an abnormal dynamic interaction between the salience network and DMN, thereby supporting the insular dysfunction model of schizophrenia from the perspective of dFC.27–29,45,46 Comparison of SZ8W with SZ0W revealed a reversal of dFC variance between the bilateral dAI and precuneus, demonstrating a positive effect of antipsychotic treatment on the dynamic interaction between the salience network and DMN, and suggesting that the dAI might be an effective target for antipsychotic treatment.

The SMA is involved in action perception and processing, and adjusting behavioral responses to stimuli.47–53 Smith et al54 found a peak activation in the SMA/aMCC cluster correlated with social competence and social attainment in individuals with schizophrenia during a cognitive empathy task, indicating that the abnormal self-reported and performance-based cognitive empathy in patients with schizophrenia were related to social functioning. Massey et al55 found that patients with schizophrenia have reduced cortical thickness in the insula and SMA, which was associated with deficit in social empathy. In the present study, the disrupted dFC variance in the dAI-SMA circuit may suggest abnormal social functioning in schizophrenia. We also found that the dFC variance between the left dAI and left SMA was modified after antipsychotic treatment. Existing evidence shows that risperidone increases the functional activation of the SMA during a working memory task in schizophrenia, providing direct evidence that risperidone enhances the SMA function when proceeding cognitive-related process.56

Abnormal dFC Variance of PI Circuits and the Treatment Effects on These Connections

Decreased dFC variance between the PI and temporal areas was observed in SZ0W. Studies using diffusion-weighted imaging techniques demonstrated that the PI has structural connections with parietal and posterior temporal areas, and these connections form a network with posterior temporal areas including the auditory cortex.57–59 The role of the posterior insula in this network involves the mapping of the auditory information onto motor action.59 Meanwhile, the current study showed abnormal dFC variance between the PI and temporal areas, indicating that the dysfunctional auditory-motor feed forward and feedback loops failed to monitor and adjust performance, which may result in lost control of goal-directed behavior in schizophrenia.60–62 We also found that the dFC variance between the PI and temporal areas increased after antipsychotic treatment. A meta-analysis of longitudinal MRI studies speculated that the reduction of gray matter in the temporal lobe seems to be associated with antipsychotic treatment.63 This finding imply the positive effect of antipsychotic treatment on auditory-motor integration involving insula and temporal areas.

Abnormal dFC Variance of vAI Circuits and the Treatment Effects on These Connections

Impaired sensory integration is one of the earliest and most common symptoms of schizophrenia.64 Studies have revealed that the IPL is involved in the experience of pain,65,66 while the vAI is involved in the process of emotion15,38,44 particularly in processing pain in the emotional dimension.67–69 Our results showed that after 8-week treatment, the dFC variance between the left vAI and right IPL decreased, indicating that the treatment effect on the integration of the sensory processing of pain was associated with vAI and IPL in schizophrenia.

Moreover, increased dFC variance between the right vAI and right FFG was observed when compared SZ8W with SZ0W. The FFG is known as the face-responsive region related to processing facial identity and invariant features of faces.70,71 The anterior insula is also believed to help lucidate the emotional content of facial expressions.72 A study has shown that patients with schizophrenia have difficulty in recognizing the emotional content of facial expressions.73 Other researchers have found reduced activity in FFG in schizophrenia when performing facial emotion tasks.74,75 In the present study, the increased dFC variance between the right vAI and right FFG after antipsychotic treatment indicated the treatment effect on the integration of emotional processing of facial expression associated with vAI and fusiform gyrus in schizophrenia.

The Mechanism for the Action of Risperidone

Risperidone is one of the atypical antipsychotics with dopamine D2 (DAD2) and serotonin 5-HT2 receptor antagonistic action.30 Given previous evidence suggesting potential relationship between serotonin or dopamine signaling and modulation of functional connectivity measures,76,77 we speculated that the post-treatment reversal of dynamic functional connectivity between the insular subdivisions and other brain areas in this study might result from treatment-related dopamine and serotonin antagonistic action.

In addition to DAD2 and 5-HT2, antipsychotic agents have also been found to change other neurotransmitters like GABA, glutamate, or glutamine, as well as neuronal metabolism like N-acetylaspartate in frontal, insular or temporal cortex.78–80 Moreover, altered neurochemicals is proposed to serve as a material substrate for functional connectivity.81 It is therefore possible that the alterations of dynamic functional connectivity of insular subdivisions after 8 weeks of treatment in this study may result from the altered neurochemicals. It is worth mentioning that this study used risperidone as a proxy for atypical medications. The current observations may be likely for other atypical antipsychotic agents, thus further studies with other control group treated with other atypical medications are needed to verify this speculation.

Limitations

Several limitations of the current study must be noted. First, there is no patient control group receiving placebo, so we cannot confidently exclude other causes of changes in brain imaging. However, a design with a patient control group receiving placebo would be clinically unethical, because effective antipsychotic treatments cannot be withheld from patients for 8 weeks. Second, there is no patient control group receiving other types of antipsychotics, so we cannot determine whether the effects observed in this study were specific to risperidone. Third, dFC is an expansion of traditional functional connectivity. The controversy over dFC originates from the indirect nature of fMRI which is used to observe it. Therefore, dFC is maybe an improvement over conventional functional connectivity, but it still does not achieve the temporal resolution required to delineate the real neural network dynamics. Forth, although dFC variance and symptom change are related, these measures did not correlate with the 8-week accumulated dose of antipsychotic medication. This result confirmed that the effect of antipsychotic treatment on dFC measures within 8 weeks was not dose dependent. However, the 8-week accumulated dose of risperidone cannot accurately reflect the plasma concentration of medication. Thus, future studies are needed to explore the relationships among plasma concentration of medication, behavior, and dFC.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated the aberrant dynamic variations of insular subdivisions in schizophrenia and a reversal of these dynamics after antipsychotic treatment. Our findings supported the proximal salience notion of schizophrenia, thereby suggesting that a dysfunction of the insula can lead to the generation of inappropriate proximal salience and thus result in the disrupted recruitment of relevant networks. A reversal of insula dynamic variations may demonstrate the treatment effect on the physiology of insula which result in an improvement in clinical status, and move forward a step closer to understanding the neuropathology of schizophrenia.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61533006, 61673089, 81871432, and U1808204), The project of the Science and Technology Department in Sichuan Province (2017JY0093, 2018TJPT00160, and 2019YJ0180), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (ZYGX2016J187 and 2672018ZYGX2018J079), the Wuhan Science and Technology Bureau grant (2017060201010169), the China Scholarship Council Program (201506370095), the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2018CFB232), the Teachers Funding Project of Wuhan University (2042018kf0125), and the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC1314600).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the participants in this study. The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1. Zaki J, Davis JI, Ochsner KN. Overlapping activity in anterior insula during interoception and emotional experience. Neuroimage. 2012;62(1):493–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Craig AD. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3(8):655–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sridharan D, Levitin DJ, Menon V. A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(34):12569–12574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blakemore SJ, Smith J, Steel R, Johnstone CE, Frith CD. The perception of self-produced sensory stimuli in patients with auditory hallucinations and passivity experiences: evidence for a breakdown in self-monitoring. Psychol Med. 2000;30(5):1131–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wylie KP, Tregellas JR. The role of the insula in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;123(2–3):93–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liao W, Fan YS, Yang S, Li J, Duan X, Cui Q, Chen H. Preservation effect: cigarette smoking acts on the dynamic of influences among unifying neuropsychiatric triple networks in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45(6):1242–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Palaniyappan L, Liddle PF. Does the salience network play a cardinal role in psychosis? An emerging hypothesis of insular dysfunction. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2012;37(1):17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goodkind M, Eickhoff SB, Oathes DJ, et al. Identification of a common neurobiological substrate for mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):305–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Howes OD, Kapur S. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: version III—the final common pathway. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(3):549–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Naqvi NH, Bechara A. The hidden island of addiction: the insula. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32(1):56–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sarpal DK, Robinson DG, Lencz T, et al. Antipsychotic treatment and functional connectivity of the striatum in first-episode schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(1):5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang YC, Tang WJ, Fan XD, et al. Resting-state functional connectivity changes within the default mode network and the salience network after antipsychotic treatment in early-phase schizophrenia. Neuropsych Dis Treat 2017;13:397–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kurth F, Zilles K, Fox PT, Laird AR, Eickhoff SB. A link between the systems: functional differentiation and integration within the human insula revealed by meta-analysis. Brain Struct Funct. 2010;214(5–6):519–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cauda F, D’Agata F, Sacco K, Duca S, Geminiani G, Vercelli A. Functional connectivity of the insula in the resting brain. Neuroimage. 2011;55(1):8–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Uddin LQ. Salience processing and insular cortical function and dysfunction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(1):55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li H, Chan RC, McAlonan GM, Gong QY. Facial emotion processing in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging data. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(5):1029–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Palaniyappan L, Mallikarjun P, Joseph V, Liddle PF. Appreciating symptoms and deficits in schizophrenia: right posterior insula and poor insight. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(2):523–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen X, Duan M, He H, et al. Functional abnormalities of the right posterior insula are related to the altered self-experience in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2016;256:26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Calhoun VD, Miller R, Pearlson G, Adali T. The chronnectome: time-varying connectivity networks as the next frontier in fMRI data discovery. Neuron. 2014;84(2):262–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hutchison RM, Womelsdorf T, Allen EA, et al. Dynamic functional connectivity: promise, issues, and interpretations. Neuroimage. 2013;80:360–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. He C, Chen Y, Jian T, et al. Dynamic functional connectivity analysis reveals decreased variability of the default-mode network in developing autistic brain. Autism Res. 2018;11(11):1479–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen H, Nomi JS, Uddin LQ, Duan X, Chen H. Intrinsic functional connectivity variance and state-specific under-connectivity in autism. Hum Brain Mapp. 2017;38(11):5740–5755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li R, Liao W, Yu Y, et al. Differential patterns of dynamic functional connectivity variability of striato-cortical circuitry in children with benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39(3):1207–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li J, Duan X, Cui Q, Chen H, Liao W. More than just statics: temporal dynamics of intrinsic brain activity predicts the suicidal ideation in depressed patients. Psychol Med. 2019;49(5):852–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liao W, Li J, Ji GJ, et al. Endless fluctuations: temporal dynamics of the amplitude of low frequency fluctuations. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2019. doi:10.1109/TMI.2019.2904555. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rashid B, Damaraju E, Pearlson GD, Calhoun VD. Dynamic connectivity states estimated from resting fMRI identify differences among schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and healthy control subjects. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8. Art. no: 897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Palaniyappan L, Deshpande G, Lanka P, Rangaprakash D, Iwabuchi S, Francis S, Liddle PF. Effective connectivity within a triple network brain system discriminates schizophrenia spectrum disorders from psychotic bipolar disorder at the single-subject level. Schizophr Res. 2018. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2018.01.006. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Supekar K, Cai W, Krishnadas R, Palaniyappan L, Menon V. Dysregulated brain dynamics in a triple-network saliency model of schizophrenia and its relation to psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;85(1):60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guo S, Zhao W, Tao H, Liu Z, Palaniyappan L. The instability of functional connectivity in patients with schizophrenia and their siblings: a dynamic connectivity study. Schizophr Res. 2018;195:183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stathis P, Antoniou K, Papadopoulou-Daifotis Z, Rimikis MN, Varonos D. Risperidone: a novel antipsychotic with many “atypical” properties? Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1996;127(3):181–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9896):951–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2 suppl):1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, et al. ; World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Schizophrenia, part 1: update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and the management of treatment resistance. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13(5):318–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kuipers E. Schizophrenia: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Primary and Secondary Care (Update). Edited by Taylor C. Leicester, UK: British Psychological Society; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shephard DA. The 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and consent. Can Med Assoc J. 1976;115(12):1191–1192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage. 2012;59(3):2142–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nomi JS, Farrant K, Damaraju E, Rachakonda S, Calhoun VD, Uddin LQ. Dynamic functional network connectivity reveals unique and overlapping profiles of insula subdivisions. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37(5):1770–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Deen B, Pitskel NB, Pelphrey KA. Three systems of insular functional connectivity identified with cluster analysis. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21(7):1498–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Majeed W, Magnuson M, Hasenkamp W, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of low frequency BOLD fluctuations in rats and humans. Neuroimage. 2011;54(2):1140–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liao W, Wu GR, Xu Q, et al. DynamicBC: a MATLAB toolbox for dynamic brain connectome analysis. Brain Connect. 2014;4(10):780–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chao-Gan Y, Yu-Feng Z. DPARSF: a MATLAB toolbox for “Pipeline” data analysis of resting-state fMRI. Front Syst Neurosci. 2010;4:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(2):676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Greicius MD, Supekar K, Menon V, Dougherty RF. Resting-state functional connectivity reflects structural connectivity in the default mode network. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(1):72–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Menon V, Uddin LQ. Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Struct Funct. 2010;214(5–6):655–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zong X, Hu M, Pantazatos SP, et al. A dissociation in effects of risperidone monotherapy on functional and anatomical connectivity within the default mode network. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45(6):1309–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Li M, Becker B, Zheng J, et al. Dysregulated maturation of the functional connectome in antipsychotic-naive, first-episode patients with adolescent-onset schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45(3):689–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fan Y, Duncan NW, de Greck M, Northoff G. Is there a core neural network in empathy? An fMRI based quantitative meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(3):903–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lamm C, Batson CD, Decety J. The neural substrate of human empathy: effects of perspective-taking and cognitive appraisal. J Cogn Neurosci. 2007;19(1):42–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Etkin A, Egner T, Kalisch R. Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(2):85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mukamel R, Ekstrom AD, Kaplan J, Iacoboni M, Fried I. Single-neuron responses in humans during execution and observation of actions. Curr Biol. 2010;20(8):750–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Keysers C, Gazzola V. Expanding the mirror: vicarious activity for actions, emotions, and sensations. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19(6):666–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jabbi M, Bastiaansen J, Keysers C. A common anterior insula representation of disgust observation, experience and imagination shows divergent functional connectivity pathways. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shamay-Tsoory SG, Lester H, Chisin R, et al. The neural correlates of understanding the other’s distress: a positron emission tomography investigation of accurate empathy. Neuroimage. 2005;27(2):468–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Smith MJ, Schroeder MP, Abram SV, et al. Alterations in brain activation during cognitive empathy are related to social functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(1):211–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Massey SH, Stern D, Alden EC, et al. Cortical thickness of neural substrates supporting cognitive empathy in individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2017;179:119–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Honey GD, Bullmore ET, Soni W, Varatheesan M, Sharma T. Differences in frontal cortical activation by a working memory task after substitution of risperidone for typical antipsychotic drugs in patients with schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(23):13432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cerliani L, Thomas RM, Jbabdi S, et al. Probabilistic tractography recovers a rostrocaudal trajectory of connectivity variability in the human insular cortex. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33(9):2005–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dennis EL, Jahanshad N, McMahon KL, et al. Development of insula connectivity between ages 12 and 30 revealed by high angular resolution diffusion imaging. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(4):1790–1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cloutman LL, Binney RJ, Drakesmith M, Parker GJ, Lambon Ralph MA. The variation of function across the human insula mirrors its patterns of structural connectivity: evidence from in vivo probabilistic tractography. Neuroimage. 2012;59(4):3514–3521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dosenbach NU, Visscher KM, Palmer ED, et al. A core system for the implementation of task sets. Neuron 2006;50(5):799–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Houde JF, Jordan MI. Sensorimotor adaptation in speech production. Science. 1998;279(5354):1213–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mutschler I, Wieckhorst B, Kowalevski S, et al. Functional organization of the human anterior insular cortex. Neurosci Lett. 2009;457(2):66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Fusar-Poli P, Smieskova R, Kempton MJ, Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Borgwardt S. Progressive brain changes in schizophrenia related to antipsychotic treatment? A meta-analysis of longitudinal MRI studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(8):1680–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Torrey EF. Schizophrenia and the inferior parietal lobule. Schizophr Res. 2007;97(1–3):215–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Apkarian AV, Darbar A, Krauss BR, Gelnar PA, Szeverenyi NM. Differentiating cortical areas related to pain perception from stimulus identification: temporal analysis of fMRI activity. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81(6):2956–2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Geschwind N. Disconnexion Syndromes in Animals and Man. Netherlands: Springer; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Baliki MN, Geha PY, Apkarian AV. Parsing pain perception between nociceptive representation and magnitude estimation. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101(2):875–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Peyron R, Laurent B, García-Larrea L. Functional imaging of brain responses to pain. A review and meta-analysis (2000). Neurophysiol Clin. 2000;30(5):263–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kong J, White NS, Kwong KK, et al. Using fMRI to dissociate sensory encoding from cognitive evaluation of heat pain intensity. Hum Brain Mapp. 2006;27(9):715–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Haxby JV, Hoffman EA, Gobbini MI. The distributed human neural system for face perception. Trends Cogn Sci. 2000;4(6):223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ishai A, Schmidt CF, Boesiger P. Face perception is mediated by a distributed cortical network. Brain Res Bull. 2005;67(1–2):87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Arnold AE, Iaria G, Goghari VM. Efficacy of identifying neural components in the face and emotion processing system in schizophrenia using a dynamic functional localizer. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2016;248:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Schneider F, Gur RC, Koch K, et al. Impairment in the specificity of emotion processing in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):442–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Quintana J, Wong T, Ortiz-Portillo E, Marder SR, Mazziotta JC. Right lateral fusiform gyrus dysfunction during facial information processing in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(12):1099–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Johnston PJ, Stojanov W, Devir H, Schall U. Functional MRI of facial emotion recognition deficits in schizophrenia and their electrophysiological correlates. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22(5):1221–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tollens F, Gass N, Becker R, et al. The affinity of antipsychotic drugs to dopamine and serotonin 5-HT2 receptors determines their effects on prefrontal-striatal functional connectivity. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28(9):1035–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Tan HY, Chen AG, Kolachana B, et al. Effective connectivity of AKT1-mediated dopaminergic working memory networks and pharmacogenetics of anti-dopaminergic treatment. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 5):1436–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Szulc A, Galinska-Skok B, Waszkiewicz N, Bibulowicz D, Konarzewska B, Tarasow E. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy changes after antipsychotic treatment. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20(3):414–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Szulc A, Galinska B, Tarasow E, et al. The effect of risperidone on metabolite measures in the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, and thalamus in schizophrenic patients. A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS). Pharmacopsychiatry. 2005;38(5):214–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Smesny S, Langbein K, Rzanny R, et al. Antipsychotic drug effects on left prefrontal phospholipid metabolism: a follow-up 31P-2D-CSI study of haloperidol and risperidone in acutely ill chronic schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(2–3):164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Duncan NW, Wiebking C, Tiret B, et al. Glutamate concentration in the medial prefrontal cortex predicts resting-state cortical-subcortical functional connectivity in humans. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.