Abstract

Trophoblasts, as the cells that make up the main part of the placenta, undergo cell differentiation processes such as invasion, migration, and fusion. Abnormalities in these processes can lead to a series of gestational diseases whose underlying mechanisms are still unclear. One protein that has proven to be essential in placentation is the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), which is expressed in the nuclei of extravillous cytotrophoblasts (EVCTs) in the first trimester and villous cytotrophoblasts (VCTs) throughout pregnancy. Here, we aimed to explore the genome-wide effects of PPARγ on EVCTs and VCTs via treatment with the PPARγ-agonist rosiglitazone. EVCTs and VCTs were purified from human chorionic villi, cultured in vitro, and treated with rosiglitazone. The transcriptomes of both types of cells were then quantified using microarray profiling. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were filtered and submitted for gene ontology (GO) annotation and pathway analysis with ClueGO. The online tool STRING was used to predict PPARγ and DEG protein interactions, while iRegulon was used to predict the binding sites for PPARγ and DEG promoters. GO and pathway terms were compared between EVCTs and VCTs with clusterProfiler. Visualizations were prepared in Cytoscape. From our microarray data, 139 DEGs were detected in rosiglitazone-treated EVCTs (RT-EVCTs) and 197 DEGs in rosiglitazone-treated VCTs (RT-VCTs). Downstream annotation analysis revealed the similarities and differences between RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs with respect to the biological processes, molecular functions, cellular components, and KEGG pathways affected by the treatment, as well as predicted binding sites for both protein-protein interactions and transcription factor-target gene interactions. These results provide a broad perspective of PPARγ-activated processes in trophoblasts; further analysis of the transcriptomic signatures of RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs should open new avenues for future research and contribute to the discovery of possible drug-targeted genes or pathways in the human placenta.

1. Introduction

The human placenta serves as a critical bridge between mother and fetus and thus plays a crucial role in maternal and fetal physiology. The placenta is composed mainly of trophoblast cells, which derive from the outer layer of the blastocyst. Certain trophoblasts can be further distinguished as villous cytotrophoblasts (VCTs), whose development progresses along with that of the placenta. In the process of embryo implantation and placenta formation, VCTs that invade the maternal uterus are known as extravillous cytotrophoblasts (EVCTs); these anchor the chorionic villi. Other VCTs differentiate and fuse to form the syncytiotrophoblast layer, which has critical functions in gas and nutrient exchange between the fetus and the mother. Defects in EVCT invasion and VCT differentiation and fusion contribute to a series of gestational diseases, such as fetus-related miscarriage [1], preterm birth [2], and preeclampsia [3]. The causes of and mechanisms behind these diseases have been the focus of much research, but as yet remain unclear.

As a member of the ligand-dependent nuclear receptor superfamily, PPARγ regulates many downstream target genes involved in lipid metabolism, cell differentiation, and tumorigenesis. PPARγ functions by forming a heterodimer with the nuclear receptor retinoid X receptor α (RXRα) and then binding to the PPAR response element (PPRE) of target genes [4]. It has been reported that a lack of PPARγ leads to defects in trophoblast differentiation and abnormal vasculogenesis in mice [5, 6], and PPARγ−/− embryonic lethality can be rescued via PPARγ transfection in the trophoblast [7]. To be more specific, previous research showed that the activation of PPARγ inhibited the invasion of first-trimester EVCTs, which implicates PPARγ in the regulation of invasion of the decidua [8, 9]. Furthermore, the activation of PPARγ can also induce the differentiation of VCTs isolated from term placenta [10]. Taken together, the current literature on the effects of PPARγ on the regulation of EVCTs and VCTs suggests that it plays a critical role in trophoblast invasion and differentiation but also that these effects differ dramatically among different subtypes of trophoblast. PPARγ thus appears to play a crucial but poorly understood role in placental development.

To explore the role of PPARγ in biological processes, the PPARγ-agonist rosiglitazone has been widely applied to various tissues. In human placenta, rosiglitazone has been used for the study of placental metabolism [11, 12], inflammation [13, 14], antioxidant response [15, 16], and preeclampsia [17]. In vitro treatment with rosiglitazone has been shown to reverse inflammation of the placenta that is mediated by the PPARγ-NF-κB pathway [13]. Similarly, rosiglitazone can improve the survival rate of trophoblasts under oxidative stress via its effects on the PPARγ pathway [15]. Other investigations into the activity of this drug have identified new potential target genes of PPARγ [17, 18]. Furthermore, the activation of PPARγ in both first-trimester EVCTs and term VCTs, as described in the research cited above on the influence of PPARγ in trophoblast invasion and differentiation, was also accomplished by this PPARγ-agonist. Taken together, these studies show the enormous potential and benefit of rosiglitazone use in studies of the placenta.

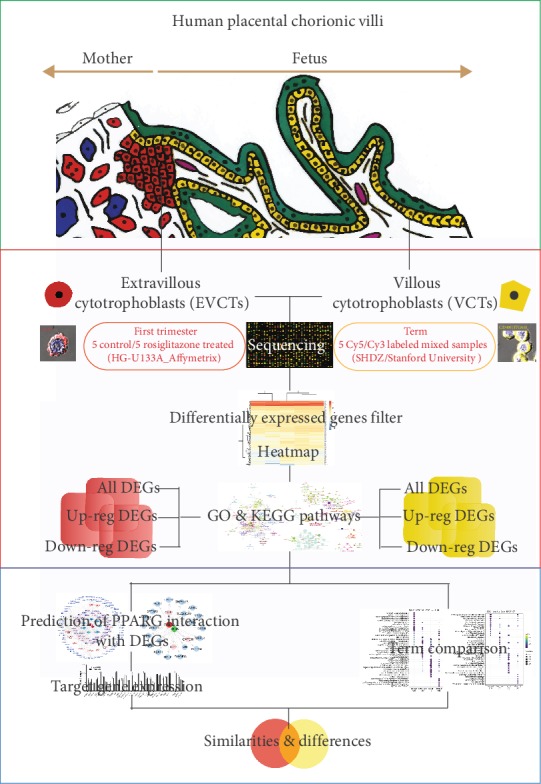

In the human placenta, PPARγ is exclusively located in the nuclei of EVCTs during the first trimester and of VCTs throughout pregnancy [19–21]. To date, there is a lack of systematic research on the effects of PPARγ in these tissues and during these developmental periods. Therefore, our purpose here was to investigate the performance of PPARγ-activated trophoblasts by analyzing the transcriptomic signatures of rosiglitazone-treated EVCTs (RT-EVCTs) and VCTs (RT-VCTs). In this study, we isolated EVCTs and VCTs from first trimester and term human chorionic villi, respectively; cultured these cells with rosiglitazone; and quantified the transcriptome of each type of cell using microarray analysis, as shown in Figure 1. Our results provide abundant information on the biological processes and pathways affected by PPARγ, as well as on the specific genes and pathways targeted, and constitute an invaluable knowledge base for future research.

Figure 1.

Summary of procedures. Extravillous cytotrophoblasts (EVCTs, HLAG+ cells) [22] and villous cytotrophoblasts (VCTs, CD49f+ cells) were isolated from human first trimester and term placental chorionic villi, respectively, treated with rosiglitazone, and analyzed using microarrays. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were filtered for quality control and submitted for annotation. Terms associated with DEGs and predictions of PPARγ-target genes were compared between the rosiglitazone-treated EVCTs and VCTs. PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. The top graphic was modified from Handschuh et al. (2007).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

Placenta samples in this study were collected with patients' written informed consent, in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Placenta tissues were collected from women with normal pregnancies during the 8-9th gestational weeks and at term (39 gestational weeks). Our ethics committee (CCPRB Paris Cochin no. 18-05) approved the collection of placentas from legal and voluntary terminations of pregnancy in the first trimester as well as of the normal term placentas.

2.2. Cell Isolation and Culture

As previously described [22], five effective first-trimester placentas were obtained for EVCT isolation. Villous tissues were rinsed and minced in Ca2+-, Mg2+-free Hanks' balanced salt solution for membrane removal. Mononucleated VCTs were isolated using digestion with trypsin-DNase and fractionation on a discontinuous Percoll gradient according to the protocol of Kliman et al. [23] and Alsat et al. [24]. In brief, villous tissues were digested in Hanks' balanced salt solution, containing 5 IU/mL of DNase I, 4.2 mM MgSO4, 0.25% (wt/vol) trypsin powder (Difco), 100 IU/mL penicillin, 25 mM HEPES, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Biochemical Industry), and monitored under invert microscopy. The initial digested solution (consisting mostly of red blood cells) was discarded while the subsequent digested solution (clearly consisting of EVCTs) was retained. A discontinuous Percoll gradient (5–70% in 5% steps) was used to stratify the digested solutions; the middle layer (which included EVCTs) was retained for further analysis. The purified EVCTs were diluted with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), with 2 mM glutamine, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and 10% decomplemented fetal calf serum (FCS), to a final density of 0.9 × 106 cells/mL in 60 mm diameter plastic tissue culture dishes (Techno Plastic Products, Switzerland). In preparation for culturing, culture plates (Techno Plastic Products, Switzerland) were coated with Matrigel™ (7 μg/cm2; Collaborative Biomedical Products, Le Pont de Claix, France), then seeded with EVCTs at a density of 5 × 104 cells/cm2. To maintain continuous culture conditions, DMEM-F12 medium was used that contained 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), Glutamax, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 100 IU/mL penicillin (Invitrogen). Plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C and 5% CO2; then, nonadherent EVCTs were rinsed off. At this point, fresh medium with or without 1 μM rosiglitazone (Cayman) dissolved at 1 mM in ethanol (treatment) or 0.1% ethanol (vehicle) was added for another 24 h of incubation.

VCTs were isolated from five term placentas using the following procedures. Placentas were oriented with the maternal side facing upwards, and tissues were sampled at a depth of 1.5 cm, half the distance from the edge to the centre. Villous tissues were rinsed, minced, digested, and purified using the steps described above. Culture dishes containing 0.9 × 106 cells/mL were placed in a humidified incubator at 37°C under 5% CO2 for 3 h. Nonadherent VCTs were rinsed off, fresh medium with or without 1 μM rosiglitazone (Cayman) dissolved at 1 mM in ethanol (treatment) or 0.1% ethanol (vehicle) was added, and dishes were incubated for another 24 h.

2.3. Microarray Experiments

After 24 h of incubation, RT-EVCTs and control EVCTs were harvested for microarray experiments. Cell RNA was extracted using TRIzol® reagents (Invitrogen) and purified using RNeasy® Mini Kits (Qiagen). RNA integrity and purity were examined with a 2100 Bioanalyzer with the RNA 6000 LabChip kit (Agilent Technologies). The U133A 2.0 GeneChip (Affymetrix, Inc.) was used for gene expression detection according to the manufacturer's manual. From the 22,000 probe sets on the gene chip, 14,500 genes were detected.

RT-VCTs and control VCTs were likewise harvested after 24 h of incubation for microarray experiments; RNA extraction, purification, and quality control were performed as described. The SHDZ gene chip (Stanford University) was used for gene detection as described in [25]: for each sample, the MessageAmp RNA kit (Ambion) was used, with 1 μg total RNA, for RNA amplification, and 3 μg amplified RNA were then labeled with Cy-dye using the 26 CyScribe first-strand cDNA labeling kit (Amersham Biosciences). Amplified RNA from rosiglitazone-treated VCTs was labeled with Cy5, and amplified RNA from control VCTs was labeled with Cy3. A Microcon YM 30 column (Millipore) was used to purify and concentrate the labeled mixture (Cy5 and Cy3) after additional modifications with human cot-1, yeast tRNA, and poly A. The probes were denatured and the mixture was hybridized at 65°C overnight in a sealed humidified hybridization chamber, then rinsed with 1XSSC, 2XSSC, 0.03% SDS, and 0.2% SDS solutions for 2 min each. Arrays were scanned with a GenePrix 4000A microarray scanner (Axon Instruments).

2.4. Data Processing

Since gene expression in EVCTs and VCTs was detected using different microarray platforms, different procedures were followed for data processing. For EVCT gene expression, which was quantified using the GeneChip (U133A 2.0, Affymetrix) application, data processing used the following filter thresholds: (i) percentage of missing data was no more than 50%, (ii) threshold to identify up- and downregulated genes for statistical comparison was set to a fold change of 1.5, (iii) maximum false discovery rate (FDR) was set to 5%, and (iv) fold change of one gene was equal to mean of treated groups minus mean of control groups and then divided by the minimum value from all (fold change = (mean (treated)–mean (control))/minimum (treated, control)) [22]. For VCT gene expression, which was measured using the SHDZ GeneChip/Stanford University (GPL21609) application, data processing used the following filter thresholds: (i) background-corrected data were log2-transformed and subjected to the Loess normalization method [11], (ii) differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were determined via the significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) method [26], and (iii) the maximum false discovery rate (FDR) was set to 1%, without a fold change threshold imposed [27].

2.5. GO and Pathway Enrichment Analyses

ClueGO is a Cytoscape plug-in application for the functional classification of genes [28]. Our analysis used Cytoscape version 3.7.1 (The Cytoscape Consortium, New York, NY) and ClueGO version 2.5.4 (released 28 Feb 2019), with the simultaneous update of gene ontology (GO) terms. Using ClueGO, we recovered the GO terms associated with the dataset of all DEGs as well as of up- or downregulated DEGs only; this same application was also used for KEGG and Reactome pathway analysis. GO terms were compared between EVCTs and VCTs using the R package clusterProfiler (version 3.9, synced to latest GO terms and pathways) [29]. For term comparison in clusterProfiler, 10 category terms for each group were selected for inclusion in charts. Instead, ClueGO analyses were based on approximately 30 terms per group in order to generate more detailed visualizations. P values lower than 0.05 identified significant enrichment.

2.6. Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network

The STRING database (https://string-db.org) was used to analyze the interactions of DEG-encoded proteins and construct a PPI network. For this, the significant confidence score was set to greater than 0.4. Cytoscape was used to visualize and organize the PPI network. Proteins interacting with PPARγ or RXRα were indicated by different colors, and shapes were used to represent different groups. Binding site interactions between transcription factors and target genes were predicted by the Cytoscape plug-in iRegulon (based on the TRANSFAC database; version 1.3). Putative regulatory regions were defined as 10 kb around transcription starting sites. The FDR was set to 0.1% to verify the interaction. The resulting chart was modified in Cytoscape using red to indicate upregulated genes and blue to indicate downregulated genes.

3. Results

3.1. Gene Expression Profiling of RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs

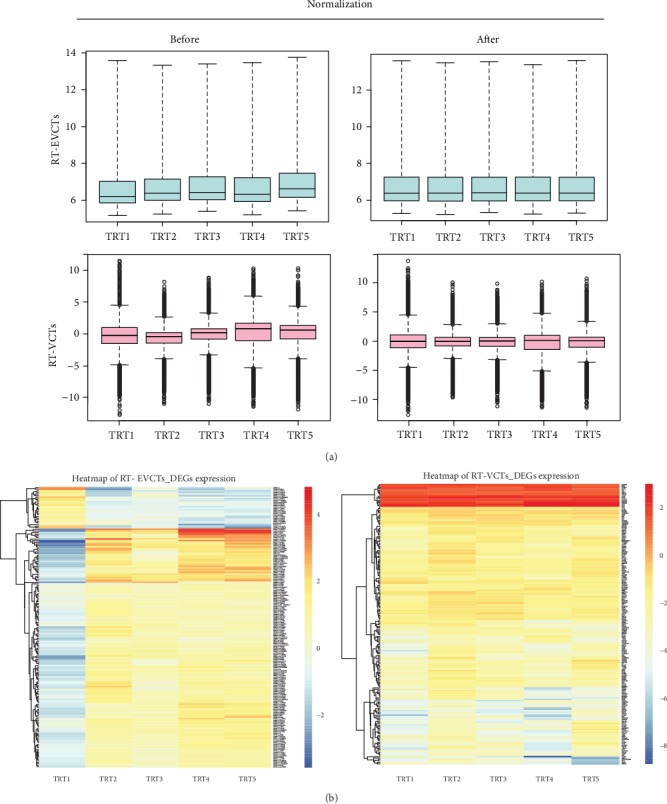

Microarrays were used to characterize gene expression in EVCTs and VCTs with or without rosiglitazone treatment. Our microarray data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus public repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; EVCT microarray data under accession number GSE28426, VCT microarray data under accession number GSE137434). Gene expression profiles of the rosiglitazone-treated (TRT) samples of EVCTs and VCTs were normalized (Figure 2(a)). Four of the five independent RT-EVCT samples yielded consistent results, with one sample appearing slightly different; instead, all five independent RT-VCT samples yielded similar results. Next, DEGs were detected based on thresholds for both fold change in expression levels and FDR. In RT-EVCTs, a total of 139 genes were identified as DEGs (P < 0.05), of which 114 genes were upregulated (red) and 25 genes were downregulated (blue). In RT-VCTs, a total of 197 genes were identified as DEGs (P < 0.05), of which 181 genes were upregulated (red) and 16 genes were downregulated (blue) (Figure 2(b)).

Figure 2.

Microarray data normalization and DEG heatmap of RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs. (a) RT-EVCT gene expression microarray was performed with the Affymetrix GeneChip while the RT-VCT microarray used the SHDZ/Stanford University chip. DEGs were detected based on the thresholds of 1.5-fold change and 5% FDR for the RT-EVCT microarray matrix; a threshold of 1% FDR was applied for the RT-VCT microarray matrix. The Loess normalization method was used to normalize both datasets. Box plots represent microarray data before and after normalization, with blue indicating data from RT-EVCTs and pink data from RT-VCTs. (b) Heatmaps of five independent samples of RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs. Upregulated DEGs are represented in red and downregulated DEGs in blue. DEGs: differentially expressed genes; RT-EVCTs: rosiglitazone-treated extravillous cytotrophoblasts; RT-VCTs: rosiglitazone-treated villous cytotrophoblasts; FDR: false discovery rate; TRT: treated.

3.2. Gene Ontology and Pathway Terms of all DEGs from RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs

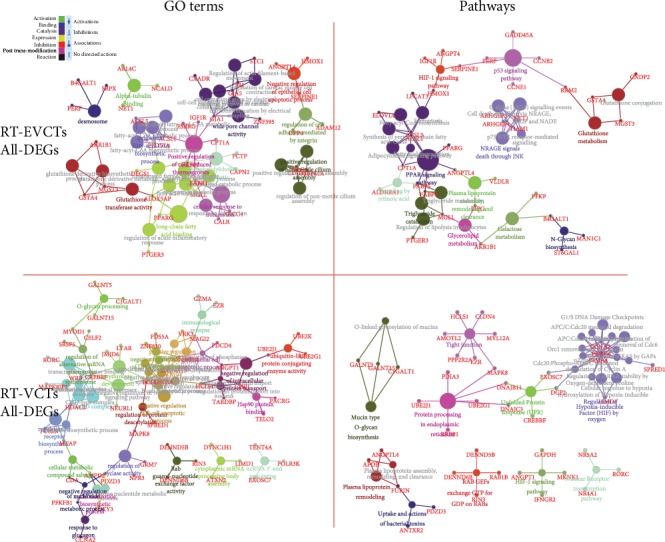

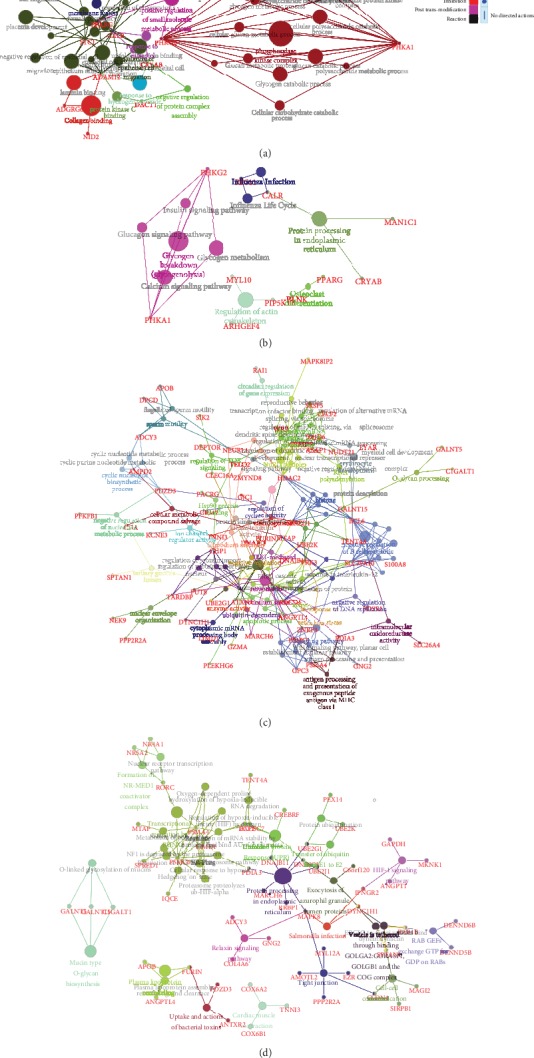

The entire set of DEGs from RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs was separated by cell type of origin and submitted independently to ClueGO with the default parameters. GO and pathway enrichment were set up for analysis. DEGs were classified by three ways: by GO biological process, GO molecular function, and GO cellular component. Enriched pathways were identified through a search of the KEGG and Reactome databases. The results are visualized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

GO and pathway terms associated with all DEGs in RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs. All DEGs were submitted separately according to their cell type of origin to ClueGO with the default parameters. GO and pathway enrichment were set up for analysis. DEGs were classified by three ways: by GO biological process, GO molecular function, and GO cellular component. The KEGG and Reactome database was consulted to determine pathway enrichment. An exhaustive list of all terms (including those not shown above) can be found in supplementary materials (Tables ). DEGs: differentially expressed genes; RT-EVCTs: rosiglitazone-treated extravillous cytotrophoblasts; RT-VCTs: rosiglitazone-treated villous cytotrophoblasts; GO: gene ontology; KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes.

Among the DEGs identified in RT-EVCTs, the main GO biological processes represented were “negative regulation of epithelial cell apoptotic process,” “long-chain fatty-acyl-CoA biosynthetic process,” and “phosphatidylcholine biosynthetic process.” For the same group of DEGs, the GO molecular functions were mainly classified as “alpha-tubulin binding,” “wide pore channel activity,” “positive regulation of cold-induced thermogenesis,” “glutathione transferase activity,” “long-chain fatty acid binding,” “regulation of cell adhesion mediated by integrin,” and “positive regulation of non-motile cilium assembly.” Finally, the GO cellular component that was most associated with these DEGs was “desmosome.” In the pathway enrichment analysis of RT-EVCTs, DEGs were mainly associated with the terms “HIF-1 signaling pathway,” “p53 signaling pathway,” “glutathione metabolism,” “NRAGE signals death through JNK,” “PPAR signaling pathway,” “plasma lipoprotein assembly,” and “remodeling and clearance”.

In the analysis of GO terms associated with the RT-VCT dataset, DEGs were mainly involved in the following biological processes: “regulation of receptor biosynthetic process,” “negative regulation of nucleotide metabolic process,” “cyclic nucleotide biosynthetic process,” and “negative regulation of B cell apoptotic process.” The molecular functions of this same group of DEGs were mainly linked to “negative regulation of DNA replication,” “regulation of protein deacetylation,” “ubiquitin-like protein conjugating enzyme activity,” “Hsp90 protein binding,” “negative regulation of intracellular protein transport,” and “positive regulation of phosphoprotein.” With respect to GO cellular components, DEGs were mainly associated with the terms “NuRD complex,” “cellular metabolic compound salvage,” and “immunological synapse.” Finally, the pathway enrichment analysis of RT-VCTs revealed that DEGs were mainly involved in “tight junction,” “regulation of HIF by oxygen,” “unfolded protein response,” “HIF-1 signaling pathway,” “nuclear receptor transcription pathway,” and “plasma lipoprotein remodeling”.

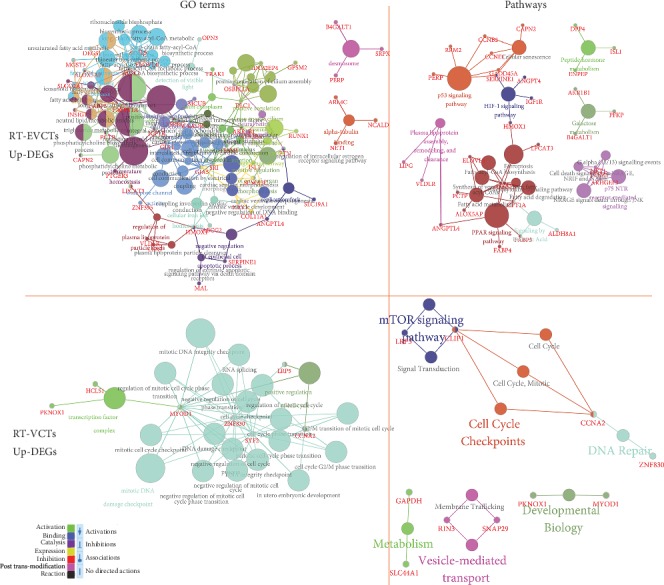

3.3. GO and Pathway Terms Associated with Upregulated DEGs in RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs

DEGs that were upregulated in RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs were submitted separately to ClueGO following the same procedure as described above. The results are visualized in Figure 4. In RT-EVCTs, upregulated DEGs were mainly associated with the GO biological processes “fatty acid derivative biosynthetic process” and “negative regulation of epithelial cell apoptotic process,” and the GO molecular functions “positive regulation of insulin secretion,” “temperature homeostasis,” “wide pore channel activity,” “nuclear receptor activity,” and “regulation of plasma lipoprotein particles levels.” The main GO cellular components implicated in the activity of these DEGs were “desmosome” and “intrinsic component of mitochondrial membrane.” Finally, the pathway enrichment analysis indicated that upregulated DEGs in RT-EVCTs were mainly involved in the “p53 signaling pathway,” “HIF-1 signaling pathway,” “peptide hormone metabolism,” “PPAR signaling pathway,” “p57 NTR receptor-mediated signaling,” and “signaling by retinoic acid”.

Figure 4.

GO and pathway terms associated with DEGs that were upregulated in RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs. These DEGs were submitted separately to ClueGO by their cell type of origin with the default parameters. GO and pathway enrichment were set up for analysis. Upregulated DEGs were classified by three ways: by their GO biological process, GO molecular function, and GO cellular component. The KEGG and Reactome databases were consulted to determine pathway enrichment. All additional enrichment terms (not shown above) can be found in supplementary materials (Tables ). DEGs: differentially expressed genes; RT-EVCTs: rosiglitazone-treated extravillous cytotrophoblasts; RT-VCTs: rosiglitazone-treated villous cytotrophoblasts; GO: gene ontology; KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes.

Instead, from the DEGs that were upregulated in RT-VCTs, no significant GO biological process was identified. In the classification of GO molecular functions, these DEGs were mainly linked with “positive regulation of cell cycle” and “mitotic DNA damage checkpoint,” and the most significant GO cellular component was “transcription factor complex.” In the pathway enrichment analysis, upregulated DEGs in RT-VCTs were mainly associated with the terms “mTOR signaling pathway,” “cell cycle checkpoints,” “DNA repair,” “developmental biology,” “metabolism,” and “vesicle-mediated transport”.

3.4. GO and Pathway Terms Associated with Downregulated DEGs in RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs

DEGs that were downregulated in RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs with respect to controls were submitted to ClueGO using the same procedure as described above. Results are visualized in Figure 5. In RT-EVCTs, downregulated DEGs were mainly associated with the GO biological process “positive regulation of small molecular metabolic process;” the GO molecular functions “membrane fusion,” “regulation of epithelial cell migration,” “response to estriol,” and “protein kinase binding;” and the GO cellular component “phosphorylase kinase complex.” From the analysis of pathway enrichment based on the KEGG and Reactome database, downregulated DEGs in RT-EVCTs appeared to be mainly associated with pathways linked with “glycogen breakdown,” “influenza infection,” “protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum,” and “regulation of actin cytoskeleton”.

Figure 5.

GO and pathway terms associated with DEGs that were downregulated in RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs, respectively, compared to controls. Downregulated DEGs of RT-EVCTs (a, b) and RT-VCTs (c, d) were submitted to ClueGO separately, with the default parameters. GO and pathway enrichment were set up for analysis. DEGs were classified by three ways: by GO biological process, GO molecular function, and GO cellular component (a, c). Pathway enrichment was determined via comparison with the KEGG database (b, d). (a) The GO terms most associated with DEGs that were downregulated in RT-EVCTs. (b) The pathways that were most enriched among the downregulated DEGs in RT-EVCTs. (c) The GO terms most associated with DEGs that were downregulated in RT-VCTs. (d) The pathways that were most enriched among the downregulated DEGs in RT-VCTs. An exhaustive list of all associated terms (including those not pictured above) can be found in supplementary materials (Tables ). DEGs: differentially expressed genes; RT-EVCTs: rosiglitazone-treated extravillous cytotrophoblasts; RT-VCTs: rosiglitazone-treated villous cytotrophoblasts; GO: gene ontology; KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes.

Instead, DEGs that were downregulated in RT-VCTs were mainly involved in the GO biological processes “cyclic nucleotide biosynthetic process,” “negative regulation of nucleotide metabolic process,” “ncRNA 3'-end processing,” and “O-glycan processing;” the GO molecular functions “nuclear receptor activity,” “histone deacetylation,” “regulation of TOR signaling,” “Hsp90 protein binding,” “ion channel regulator activity,” “nuclear envelope organization,” and “peptidyl-threonine modification;” and the GO cellular component “organellar ribosome.” In the pathway enrichment analysis of RT-VCTs, downregulated DEGs were mainly associated with the “HIF-1 signaling pathway,” “transfer of ubiquitin from E1 to E3,” “cell-cell communication,” “transcription regulation of RUNX3,” and “formation of NR-MED1 coactivator complex”.

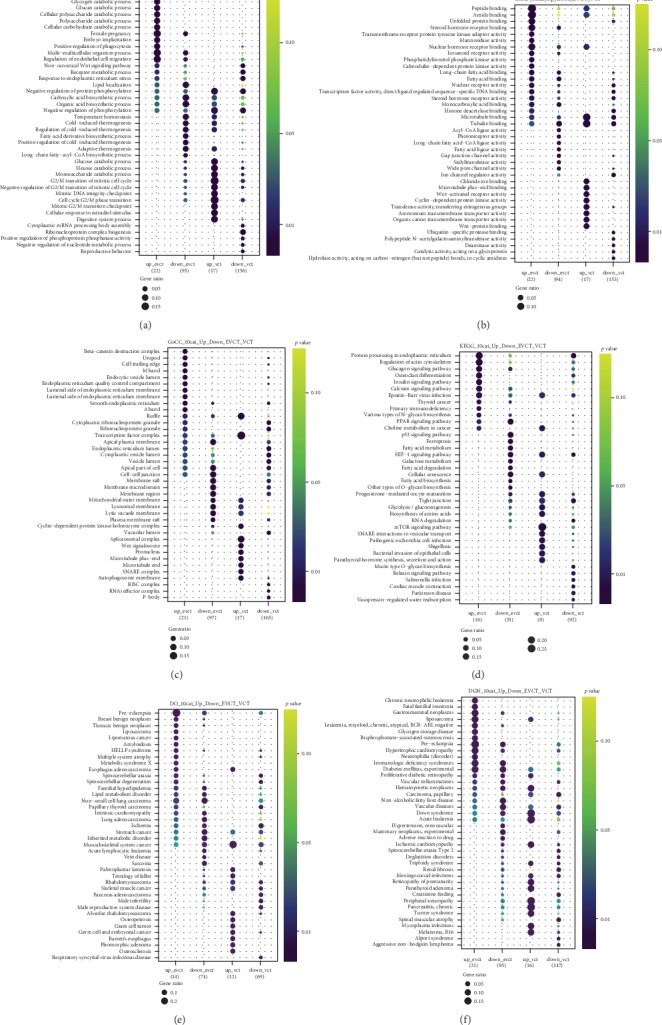

3.5. Comparison of GO Terms Associated with Tissue-Specific or Tissue-Generalist DEGs

Next, we wanted to determine the extent to which the cellular processes affected by rosiglitazone treatment were specific to either EVCTs or VCTs, and which instead were present in both tissue types. To do this, we characterized the up- and downregulated DEGs of RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs separately using clusterProfiler, using information from the GO and KEGG databases, as well as the Disease Ontology (DO) and Disease Gene Network (DisGeNET) databases. Terms appearing in at least three columns were thought important in both, while terms appearing only in the RT-EVCT or RT-VCT dataset were labelled tissue-specific; significance was determined by P values less than 0.05.

In both RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs, the GO biological processes “regulation of endothelial cell migration,” “non-canonical Wnt signaling pathway,” “receptor metabolic process,” “negative regulation of protein phosphorylation,” and “metabolism process” appeared to play important roles. Instead, processes specific to RT-EVCTs included “glycogen catabolic process,” “cellular carbohydrate catabolic process,” “embryo implantation,” “fatty acid derivative biosynthetic process,” and “long-chain fatty-acyl-CoA biosynthetic process,” while those specific to RT-VCTs were “cytoplasmic mRNA processing body assembly,” “ribonucleoprotein complex biogenesis,” “positive regulation of phosphoprotein phosphatase activity,” and “negative regulation of nucleotide metabolic process” (Figure 6(a)).

Figure 6.

Comparison of enriched GO terms between RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs. Up and downregulated DEGs of RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs were submitted separately to analysis in clusterProfiler, for a total of four groups. GO and pathway enrichment were set up for analysis. DEGs were classified by their associated (a) GO biological process, (b) GO molecular function, and (c) GO cellular component. DEGs were further compared with the (d) KEGG database to characterize pathway enrichment, (e) the Disease Ontology (DO) gene set, and (f) the Disease Gene Network (DisGeNET) database. For the purpose of visualization, the top ten categories of enriched terms were included for each gene set. A P value less than 0.05 determined significance. DEGs: differentially expressed genes; RT-EVCTs: rosiglitazone-treated extravillous cytotrophoblasts; RT-VCTs: rosiglitazone-treated cytotrophoblasts; GO: gene ontology; KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes.

The GO molecular functions “nuclear hormone receptor binding,” “long-chain fatty acid binding,” “fatty acid binding,” “nuclear activity,” and “transcription factor activity” seemed to be important in both RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs. Functions specific to RT-EVCTs included “steroid hormone receptor binding,” “eicosanoid receptor activity,” “phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase activity,” and “fatty acid ligase activity,” while those specific to RT-VCTs were “Wnt-activated receptor activity,” “cyclin-dependent protein kinase activity,” “transferase activity,” and “ubiquitin-specific protease activity” (Figure 6(b)).

Both tissue types shared the significant GO cellular components “smooth endoplasmic reticulum,” “ruffle,” “transcription factor complex,” “apical plasma membrane,” “lumen,” and “cell-cell junction.” Instead, the component terms “beta-catenin destruction complex,” “M band,” “integral component of lumenal side of endoplasmic reticulum membrane,” and “A band” were found only in RT-EVCTs, while “spliceosomal complex,” “Wnt signalosome,” “pronucleus,” “microtubule end,” and “autophagosome membrane” appeared to be specific to RT-VCTs (Figure 6(c)).

Through a search of the KEGG database, the following pathways appeared to be important in both tissue types: “protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum,” “glucagon signaling pathway,” “Epstein-Barr virus infection,” “PPAR signaling pathway,” “HIF-1 signaling pathway,” “progesterone-mediated oocyte maturation,” and “mTOR signaling pathway.” Pathway terms specific to RT-EVCTs included “primary immunodeficiency” and “fatty acid metabolism,” while those specific to RT-VCTs were linked with “bacterial invasion of epithelial cells” and “parathyroid hormone synthesis, secretion, and action” (Figure 6(d)).

From the Disease Ontology database, the terms “preeclampsia,” “HELLP syndrome,” “spinocerebellar ataxia,” “familial hyperlipidemia,” “lipid metabolism disorder,” and “musculoskeletal system cancer” were important in both EVCTs and VCTs. Terms specific to RT-EVCTs included “breast benign neoplasm,” “thoracic benign neoplasm,” “lipomatous cancer,” “amyloidosis,” and “vein disease,” while those specific to RT-VCTs were “alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma,” “osteopetrosis,” “giant cell tumor,” and “germ cell and embryonal cancer” (Figure 6(e)).

From a search of the DisGeNET database, the terms “preeclampsia,” “hypertrophic cardiomyopathy,” “immunologic deficiency syndromes,” “diabetes mellitus,” “vascular inflammations,” “hematopoietic neoplasms,” “non-alcoholic fatty liver disease,” “vascular disease,” “ischemic cardiomyopathy,” and “triploidy syndrome” were significant for both tissue types. Instead, “chronic neutrophilic leukemia,” “glycogen storage disease,” and “myeloid, chronic, atypical, and BCR-ABL negative leukemia” were specific to RT-EVCTs, and “alport syndrome” and “aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma” were specific to RT-VCTs (Figure 6(f)).

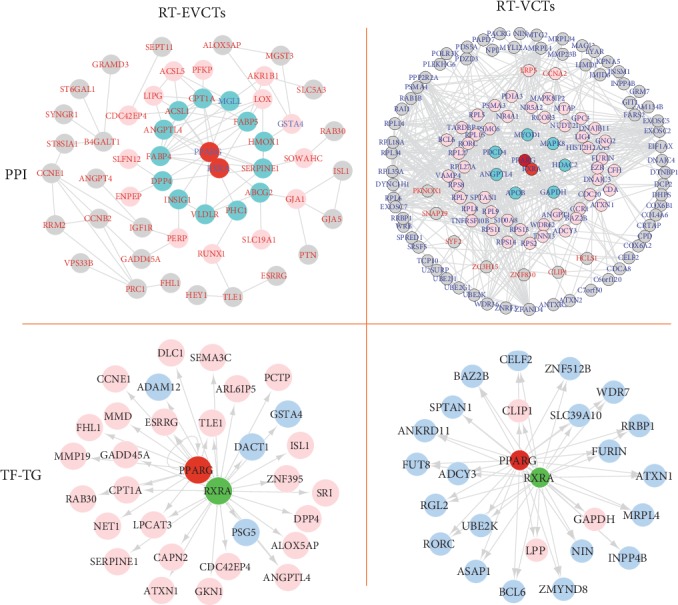

3.6. PPARγ Interactions with DEGs of RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs

Since the gene expression changes we observed here were caused by the activation of PPARγ by rosiglitazone, we next attempted to predict (i) the protein-protein interactions (PPI) of PPARγ with DEG-encoded proteins and (ii) the transcription factor-target gene (TF-TG) interactions of PPARγ with DEG promoters. In RT-EVCTs (Figure 7(a)), the following proteins appeared to interact directly with the PPARγ complex: MGLL, FABP5, HMOX1, SERPINE1, ABCG2, PHC1, VLDLR, INSIG1, DPP4, ANGPTL4, FAPB4, ACSL1, and CPT1A. Instead, ACSL5, PFKP, AKR1B1, LOX, GXTA4, SOWAHC, GJA1, SLC19A1, RUNX1, PERP, ENPEP, SLFN12, CDC42EP, and LIPG participated in secondary interactions. In RT-VCTs (Figure 7(b)), the PPARγ complex interacted directly with MYOD1, MAPK8, HDAC2, GAPDH, APOB, ANGPTL4, and PDCD4 and secondarily with PDIA3, MAPK8IP2, NR4A1, GNG2, and CCR1. Our analysis of TF-TG interactions in RT-EVCTs (Figure 7(c)) predicted that the target genes of the PPARγ complex were the upregulated DEGs DLC1, SEMA3C, ARL6IP5, PCTP, ISL1, ZNF395, SR1, DPP4, ALOX5AP, ANGPL4, CDC42EP4, GKN1, ATXN1, CAPN2, LPCAT3, SERPINE1, NET1, LPCAT3, CPT1A, RAB30, GADD45A, MMP19, FHL1, MMD, CCNE1, and ESRRG, as well as the downregulated DEGs ADAM12, GSTA4, PSG5, and DACT1. The same analysis of RT-VCTs (Figure 7(d)) predicted that the target genes of the PPARγ complex were the upregulated DEGs CLIP1, GAPDH, and LPP, as well as the downregulated DEGs CELF2, ZNF512B, SLC39A10, WDR7, FURIN, RRBP1, ATXN1, MRPL4, INNPP4B, ZMYND8, BCL6, ASAP1, UBE2K, RORC, RGL2, ADCY3, FUT8, ANKRD11, SPTAN1, and BAZ2B.

Figure 7.

Interactions of the PPARγ and RXRα complex with DEGs of RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs. Predictions were made of protein-protein interactions between PPARγ and DEG-encoded proteins, as well as of the transcription factor-target gene (TF-TG) interactions of PPARγ with DEG promoters. The PPARγ and RXRα (heterodimeric nuclear receptor partner of PPARγ) complex, together with the DEGs recovered in this study, were submitted to the STRING online tool. Visualizations were modified in Cytoscope to depict hierarchical interactions and gene expression. For hierarchical protein-protein interactions, red text represents upregulated genes, blue text represents downregulated genes, blue circles represent direct interactions with the PPARγ complex, red circles represent second-level interactions, and grey circles represent plus-level interactions. TF-TG interactions of the PPARγ complex with DEG promoters were predicted by iRegulon based on the TRANSFAC database. Red circles represent upregulated DEGs and blue circles represent downregulated DEGs. PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ; RXRα: retinoid x receptor-α; RT-EVCTs: rosiglitazone-treated extravillous cytotrophoblasts; RT-VCTs: rosiglitazone-treated villous cytotrophoblasts; DEGs: differentially expressed genes; PPI: protein-protein-interaction; TF-TG: transcription factor-target gene.

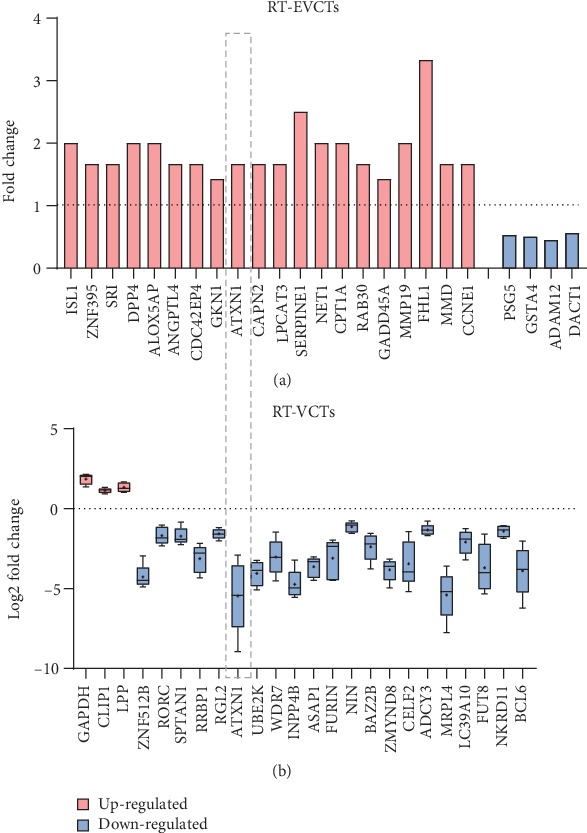

3.7. Expression of Genes Targeted by PPARγ in RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs

We next filtered our datasets to examine only the DEGs targeted directly by the PPARγ complex, based on the TF-TG predictions described above. The filtered RT-EVCT database contained 26 upregulated and 4 downregulated DEGs (Figure 8(a)), while the filtered RT-VCT database contained 3 upregulated and 21 downregulated DEGs (Figure 8(b)). Only one target gene, ATXN1, was present in both datasets; it was upregulated in RT-EVCTs and downregulated in RT-VCTs (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Expression of genes targeted by PPARγ and RXRα in RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs. Gene symbols were retrieved from the normalized gene expression matrix, together with the log2 fold change values in each sample. With these values, boxplots were graphed for (a) RT-EVCTs and (b) RT-VCTs, with upregulation represented in red and downregulation in blue. The grey dashed box indicates the only gene found in both tissue types. PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ; RXRα: retinoid x receptor-α; RT-EVCTs: rosiglitazone-treated extravillous cytotrophoblasts; RT-VCTs: rosiglitazone-treated cytotrophoblasts.

4. Discussion

The human placenta is a critical bridge between mother and fetus, facilitating nutrient exchange and various endocrine and immunological processes. As the cells that form the main part of the placenta, trophoblasts undergo extensive cell differentiation, including invasion, migration, and fusion. Abnormalities in these physiological processes can lead to a series of gestational diseases such as preeclampsia or intrauterine growth restriction. Specifically, both of these disorders appear to be associated with irregularities in the invasion of EVCTs into the maternal uterus, a biological process that is tightly controlled both spatially and temporally [30, 31]. However, the underlying mechanism linking EVCT invasion to gestational dysfunction has yet to be fully investigated. Our team has previously shown the critical influence of activated PPARγ on trophoblasts via treatment of the natural ligands of PPARγ or its specific agonist rosiglitazone [9, 20, 22, 32]. Rosiglitazone is the first synthetic chemical compound to be developed that demonstrates high selectivity for PPARγ (Kd approximately 40 nM); concentrations of up to 100 μM of this compound have been reported to activate only PPARγ (including the PPARα/β/δ complex [33]). Moreover, our previous research revealed that a concentration of only 1 μM rosiglitazone led to significant alterations in trophoblast differentiation, with more than 50% inhibition of EVCT invasion [9]. In this study, we treated EVCTs and VCTs with 1 μM rosiglitazone in order to more fully understand the effects of PPARγ on gene expression in these tissues.

Our microarray results for EVCTs were published previously with the aim of identifying significant DEGs for further study [22]. However, this work provided little information about the relative enrichment of pathways and processes among these DEGs and did not include any comparisons with RT-VCTs. To more broadly determine the key genes, biological processes, and pathways affected by activated PPARγ in trophoblasts, in this study, we also analyzed gene expression changes in VCTs using microarray profiling, and, through various approaches, identified the enriched processes that were linked with these DEGs in RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs. We were thus able to compare the similarities and differences between EVCTs and VCTs affected by activated PPARγ. In total, there were 139 DEGs in RT-EVCTs and 197 DEGs in RT-VCTs, and these were associated with enrichment in more than 200 GO and pathway terms (Tables ). Of these terms, the most significant and relevant are depicted in the figures. The majority of the terms recovered in our analysis were consistent with reports from the existing literature. For example, the terms “long-chain fatty-acyl-CoA biosynthetic process,” “regulation of plasma lipoprotein particle levels,” “plasma lipoprotein remodeling,” and “PPAR signaling pathway” are all associated with “fatty acid transport,” which in the placenta is known to demonstrate sex-specific differences due to the PPARγ-dependent response of genes involved in lipogenesis [34]. Signaling molecules and dynamic regulation of the cytoskeleton are required in trophoblast invasion [35–37], which are related to such terms as “regulation of epithelial cell migration,” “regulation of actin cytoskeleton,” and “tight junction.” Among the specific pathways highlighted, the HIF-1 signaling pathway is known to participate in PPARγ-mediated placental angiogenesis [16]; the P53 signaling pathway mediates trophoblast apoptosis via ligand-specific activation of PPARγ [10]; the JNK signaling pathway plays an essential role in blood-placental barrier formation [38, 39], as well as in EVCT migration and endothelial-like tube formation [40]; and the mTOR signaling pathway regulates adipogenic proteins in the placenta, with mTOR acting as a decidual nutrient sensor in histotrophic nutrition, which is crucial to embryo viability as well as early placental and fetal development [41]. Furthermore, our results were also consistent with the posttranscriptional modifications involved in placentation, with the terms “positive regulation of phosphoprotein,” “regulation of protein deacetylation,” “histone deacetylation,” and “ubiquitin-like protein conjugating enzyme activity” all known from previous reports. Indeed, different subtypes of trophoblast vary in phosphorylation status depending on the stage of placental development and differentiation. For example, EVCTs require Smad2/3 phosphorylation for differentiation while the absence of pSmad2C is necessary for VCTs [42]. Downregulation of histone deacetylase-9 can repress trophoblast migration and invasion [43], and likewise, inhibition of histone acetylation in human endometrial stromal cells limits trophoblast invasion [44]. Ubiquitination of amino acid transporters expressed specifically in the plasma membrane of the trophoblast can decrease amino acid uptake, leading to abnormal development of the placenta and restricted fetal growth [45, 46]. In addition, PPARγ can be phosphorylated through activation of the downstream ERKs 1/2 or p38/c-JNK pathways [47, 48]. Rosiglitazone blocks the acetylation of lysine residues of PPARγ at positions K268ac and K293ac [49]. Atypical polyubiquitination of PPARγ reduces proteasomal degradation and guarantees the stabilization of PPARγ [50, 51].

A major aim of this study was to compare patterns of enrichment between RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs. During EVCT invasion, noninvasive EVCTs undergo an epithelial-mesenchymal transition to acquire the invasive phenotype [52]. Invasive EVCTs then migrate away from the placenta up to the first third of the endometrium and colonize the maternal spiral arteries. We found a comparison of these two types of trophoblasts to be particularly compelling, given the number of studies that have focused on their differences and similarities. For example, the transformation of noninvasive EVCTs into invasive EVCTs involves expression differences in adhesion molecules, which manifest themselves when EVCTs escape from the anchoring column and invade into the endometrium (decidua, spiral arteries, and myometrium) [53]. Other studies have examined differences between EVCTs and VCTs with respect to hCG secretion for the normal maintenance of pregnancy [54] and placental cytokine secretion [55]. These biological processes are apparent in the terms recovered here that were associated with “regulation of endothelial cell migration,” “embryo implantation,” “steroid hormone receptor binding,” “secretion and action,” and “preeclampsia.” The main point is that these biological processes have all been reported to be regulated by PPARγ. For example, the activation of PPARγ has been found to prevent the TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition via inhibition of transcription of the E-cadherin and N-cadherin promoters [56]. Furthermore, PPARγ was reported to modulate basal levels of the hCGα and hCGβ subunits, resulting in differences in expression between EVCTs and VCTs [57]. Additional evidence has been obtained from studies with rosiglitazone; for example, treatment with 1 μM of the PPARγ agonist was found to decrease and increase, respectively, the number of transcripts of TGFβ2 and IL1β [32]. Such regulatory changes might be represented here by the terms “regulation of endothelial cell migration,” “Wnt signaling pathway,” “negative regulation of protein phosphorylation,” “transcription factor activity,” “PPAR signaling pathway,” and “HIF-1 signaling pathway”.

In general, our datasets revealed an abundance of biological processes or pathways affected by PPARγ, many of which are consistent with previous reports. This concordance should increase confidence in our results and indicate avenues for further study. However, because this study relied on DNA microarray technology, it was inherently limited by the probe set used; it is possible that some unknown genes may not have been detected effectively and certain biological processes or pathways may have been missed. Further exploration with the application of advanced technology such as RNAseq would be helpful to identify and fill in any missing gaps in our dataset.

Finally, in order to facilitate study of the mechanisms behind the molecular interactions, we attempted to predict the protein-protein interactions between the DEGs recovered here and PPARγ and RXRα. As was recently reviewed, the transcription exerted by the PPARγ and RXRα complex can be modified by different types of cofactors, such as the transcriptional corepressors SMRT (silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors) and NCoR (nuclear receptor corepressor), which block transactivation or the transcriptional coactivators CREB-binding protein (CBP), histone acetyltransferase p300 (p300), and PPAR-binding protein (PBP), which have the opposite effect [58]. We propose that the interaction with PPARγ might affect the transcription complex formed by PPARγ and RXRα, their cofactors or transcription partners, which could then lead to alterations in the regulation of different transcription circuits. Our results provided evidence for direct protein-protein and protein-promoter interaction with the PPARγ complex. Among the proteins that appear to interact directly with PPARγ, several have been experimentally verified, including ANGPTL4 [59–61], ABCG2 [62], APOB [63], CCNE1 [64], CPT1B [65], FABP4 [66–69], HMOX1 [70], and SERPINE1 [71, 72]. Many of the TF-TG interactions, which were predicted using the position weight matrix algorithm, have not been previously reported and await further verification. Our interaction matrix (Figure 7) also revealed more extensive upstream-to-downstream signaling pathways, such as the PPARγ-MAPK-MMP signaling pathway. Commonly, phosphorylated PPARγ stimulates the MAPK-activated pathway, leading to the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) that then induce the upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) [73–75]. Here, only a single DEG, ATXN1, was found in both types of rosiglitazone-treated trophoblast, but with opposing responses in RT-EVCTs and RT-VCTs: this gene was upregulated in RT-EVCTs and downregulated in RT-VCTs. It has been reported that the ATXN1 protein family can regulate remodeling of the extracellular matrix [76], which indicates a potential involvement in trophoblast differentiation. However, further research is needed to determine if this gene is solely responsible for the different responses of the two distinct cell types to PPARγ activation. In addition to the direct target genes predicted here, the genes in secondary relationships should be paid equal attention in terms of potential regulation by other target genes. For example, our previous research has shown the key role of LOX1, through secondary interactions, in cytotrophoblast invasion [22].

5. Conclusions

To our knowledge, our results reveal for the first time the widespread effects of PPARγ activation in EVCTs and VCTs, highlighting extensive changes in gene expression and the biological processes and pathways affected. This study provides a broad perspective of PPARγ-influenced biological processes in trophoblasts and facilitates further study, particularly into potential drug-targeted genes or pathways in the human placenta.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the consenting patients and the clinical staff midwives of Cochin Port Royal for providing placental tissues and Dr. Danièle Evain-Brion, former director of the Unit, for her support, as well as Lindsay Higgins for English editing (http://www.englishservicesforscientists.com). This work was carried out with the funding support of INSERM, University of Paris Descartes, and RSI Professions Libérales Provinces, 44 boulevard de la Bastille, 75578 Paris Cedex 12, as well as the China Scholarship Council (CSC) in Chegongzhuang Avenue, Beijing 100044, P. R China.

Data Availability

Our microarray data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus public repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/); EVCT microarray data under accession number GSE28426, VCT microarray data under accession number GSE137434).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest that could affect the impartiality of the reported research.

Authors' Contributions

Séverine A. Degrelle and Thierry Fournier contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary Materials

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were selected from the EVCT microarray data under accession number GSE28426 and VCT microarray data under accession number GSE137434. These genes were subsequently enriched according to the gene ontology (GO) terms. The terms of the enriched results were shown in detail in Tables S1-S8. Table S1-S4 shows the terms of GO biological process, GO cellular component, GO molecular function, and pathways of DEGs from the EVCT microarray data, respectively, while Table S5-S8 shows the terms of GO biological process, GO cellular component, GO molecular function, and pathways of DEGs from the VCT microarray data, respectively. Table S1_EVCT_DEGs_Go_Biological Process. Table S2_EVCT_DEGs_Go_Cellular Component. Table S3_EVCT_DEGs_Go_Molecular Function. Table S4_EVCT_DEGs_Pathways. Table S5_VCT_DEGs_Go_Biological Process. Table S6_VCT_DEGs_Go_Cellular Component. Table S7_VCT_DEGs_Go_Molecular Function. Table S8_VCT_DEGs_Pathways.

References

- 1.Buchrieser J., Degrelle S. A., Couderc T., et al. IFITM proteins inhibit placental syncytiotrophoblast formation and promote fetal demise. Science. 2019;365(6449):176–180. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw7733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Labarrere C. A., DiCarlo H. L., Bammerlin E., et al. Failure of physiologic transformation of spiral arteries, endothelial and trophoblast cell activation, and acute atherosis in the basal plate of the placenta. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017;216(3):287.e1–287.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ji L., Brkić J., Liu M., Fu G., Peng C., Wang Y.-L. Placental trophoblast cell differentiation: physiological regulation and pathological relevance to preeclampsia. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2013;34(5):981–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandra V., Huang P., Hamuro Y., et al. Structure of the intact PPAR-γ-RXR-α nuclear receptor complex on DNA. Nature. 2008;456(7220):350–356. doi: 10.1038/nature07413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barak Y., Nelson M. C., Ong E. S., et al. PPARγ is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Molecular Cell. 1999;4(4):585–595. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kubota N., Terauchi Y., Miki H., et al. PPARγ mediates high-fat diet-induced adipocyte hypertrophy and insulin resistance. Molecular Cell. 1999;4(4):597–609. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duan S. Z., Ivashchenko C. Y., Whitesall S. E., et al. Hypotension, lipodystrophy, and insulin resistance in generalized PPARγ-deficient mice rescued from embryonic lethality. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117(3):812–822. doi: 10.1172/JCI28859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fournier T., Pavan L., Tarrade A., et al. The role of PPAR-γ/RXR-α heterodimers in the regulation of human trophoblast invasion. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2002;973:26–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tarrade A., Schoonjans K., Pavan L., et al. PPARγ/RXRα heterodimers control human trophoblast invasion. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86(10):5017–5024. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaiff W. T., Carlson M. G., Smith S. D., Levy R., Nelson D. M., Sadovsky Y. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ modulates differentiation of human trophoblast in a ligand-specific manner. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2000;85(10):3874–3881. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.10.6885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Q., Yang D., Gao L., et al. Downregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in the placenta correlates to hyperglycemia in offspring at young adulthood after exposure to gestational diabetes mellitus. Journal of Diabetes Investigation. 2019;10(2):499–512. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J. R., Lazarenko O. P., Blackburn M. L., et al. Maternal obesity programs senescence signaling and glucose metabolism in osteo-progenitors from rat and human. Endocrinology. 2016;157(11):4172–4183. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kadam L., Kilburn B., Baczyk D., Kohan-Ghadr H. R., Kingdom J., Drewlo S. Rosiglitazone blocks first trimester in-vitro placental injury caused by NF- κB-mediated inflammation. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1, article 2018) doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-38336-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kadam L., Gomez-Lopez N., Mial T. N., Kohan-Ghadr H. R., Drewlo S. Rosiglitazone regulates TLR4 and rescues HO-1 and NRF2 expression in myometrial and decidual macrophages in inflammation-induced preterm birth. Reproductive Sciences. 2017;24(12):1590–1599. doi: 10.1177/1933719117697128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohan-Ghadr H. R., Kilburn B. A., Kadam L., et al. Rosiglitazone augments antioxidant response in the human trophoblast and prevents apoptosis. Biology of Reproduction. 2019;100(2):479–494. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioy186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J., Peng X., Yuan A., Xie Y., Yang Q., Xue L. Peroxisome proliferator‑activated receptor γ mediates porcine placental angiogenesis through hypoxia inducible factor‑, vascular endothelial growth factor‑ and angiopoietin‑mediated signaling. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2017;16(3):2636–2644. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu L., Zhuang X., Jiang M., Guan F., Fu Q., Lin J. ANGPTL4 mediates the protective role of PPARγ activators in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Cell Death & Disease. 2017;8(9, article e3054) doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin Y., Bircsak K. M., Gorczyca L., Wen X., Aleksunes L. M. Regulation of the placental BCRP transporter by PPARγ. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology. 2017;31(5, article e21880) doi: 10.1002/jbt.21880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fournier T., Guibourdenche J., Handschuh K., et al. PPARγ and human trophoblast differentiation. Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2011;90(1):41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fournier T., Therond P., Handschuh K., Tsatsaris V., Evain-Brion D. PPARγ and early human placental development. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;15(28):3011–3024. doi: 10.2174/092986708786848677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fournier T., Handschuh K., Tsatsaris V., Guibourdenche J., Evain-Brion D. Role of nuclear receptors and their ligands in human trophoblast invasion. Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2008;77(2):161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Segond N., Degrelle S. A., Berndt S., et al. Transcriptome analysis of PPARγ target genes reveals the involvement of lysyl oxidase in human placental cytotrophoblast invasion. PLoS One. 2013;8(11, article e79413) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kliman H. J., Nestler J. E., Sermasi E., Sanger J. M., Strauss J. F., III Purification, characterization, and in vitro differentiation of cytotrophoblasts from human term Placentae. Endocrinology. 1986;118(4):1567–1582. doi: 10.1210/endo-118-4-1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alsat E., Mirlesse V., Fondacci C., Dodeur M., Evain-Brion D. Parathyroid hormone increases epidermal growth factor receptors in cultured human trophoblastic cells from early and term placenta. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1991;73(2):288–295. doi: 10.1210/jcem-73-2-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henegar C., Tordjman J., Achard V., et al. Adipose tissue transcriptomic signature highlights the pathological relevance of extracellular matrix in human obesity. Genome Biology. 2008;9(1, article R14) doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tusher V. G., Tibshirani R., Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(9):5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rouault C., Clément K., Guesnon M., et al. Transcriptomic signatures of villous cytotrophoblast and syncytiotrophoblast in term human placenta. Placenta. 2016;44:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bindea G., Mlecnik B., Hackl H., et al. ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(8):1091–1093. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu G., Wang L. G., Han Y., He Q. Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16(5):284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huppertz B. Placental origins of Preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2008;51(4):970–975. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.107607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts J. M., Cooper D. W. Pathogenesis and genetics of pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2001;357(9249):53–56. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03577-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fournier T., Handschuh K., Tsatsaris V., Evain-Brion D. Involvement of PPARγ in human trophoblast invasion. Placenta. 2007;28(Supplement A):S76–S81. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lehmann J. M., Moore L. B., Smith-Oliver T. A., Wilkison W. O., Willson T. M., Kliewer S. A. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(22):12953–12956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gimpfl M., Rozman J., Dahlhoff M., et al. Modification of the fatty acid composition of an obesogenic diet improves the maternal and placental metabolic environment in obese pregnant mice. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2017;1863(6):1605–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ridley A. J., Schwartz M. A., Burridge K., et al. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302(5651):1704–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chakraborty C., Gleeson L. M., McKinnon T., Lala P. K. Regulation of human trophoblast migration and invasiveness. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2002;80(2):116–124. doi: 10.1139/y02-016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bischoff P., Meisser A., Campana A. Paracrine and Autocrine Regulators of Trophoblast Invasion– A Review. Placenta. 2000;21(Supplement A):S55–S60. doi: 10.1053/plac.2000.0521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nadeau V., Charron J. Essential role of the ERK/MAPK pathway in blood-placental barrier formation. Development. 2014;141(14):2825–2837. doi: 10.1242/dev.107409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charron J., Bissonauth V., Nadeau V. Implication of MEK1 and MEK2 in the establishment of the blood-placenta barrier during placentogenesis in mouse. Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 2012;25(1):58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lala N., Girish G. V., Cloutier-Bosworth A., Lala P. K. Mechanisms in decorin regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced human trophoblast migration and acquisition of endothelial Phenotype1. Biology of Reproduction. 2012;87(3):p. 59. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.097881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberti S. L., Higa R., White V., Powell T. L., Jansson T., Jawerbaum A. Critical role of mTOR, PPARγ and PPARδ signaling in regulating early pregnancy decidual function, embryo viability and feto-placental growth. Molecular Human Reproduction. 2018;24(6):327–340. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gay013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haider S., Kunihs V., Fiala C., Pollheimer J., Knofler M. Expression pattern and phosphorylation status of Smad2/3 in different subtypes of human first trimester trophoblast. Placenta. 2017;57:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xie D., Zhu J., Liu Q., et al. Dysregulation of HDAC9 represses trophoblast cell migration and invasion through TIMP3 activation in preeclampsia. American Journal of Hypertension. 2019;32(5):515–523. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpz006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Estella C., Herrer I., Atkinson S. P., et al. Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity in human endometrial stromal cells promotes extracellular matrix remodelling and limits embryo invasion. PLoS One. 2012;7(1, article e30508) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosario F. J., Dimasuay K. G., Kanai Y., Powell T. L., Jansson T. Regulation of amino acid transporter trafficking by mTORC1 in primary human trophoblast cells is mediated by the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2. Clinical Science. 2016;130(7):499–512. doi: 10.1042/CS20150554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Y. Y., Rosario F. J., Shehab M. A., Powell T. L., Gupta M. B., Jansson T. Increased ubiquitination and reduced plasma membrane trafficking of placental amino acid transporter SNAT-2 in human IUGR. Clinical Science. 2015;129(12):1131–1141. doi: 10.1042/CS20150511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Camp H. S., Tafuri S. R. Regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activity by mitogen-activated protein kinase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(16):10811–10816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu E., Kim J. B., Sarraf P., Spiegelman B. M. Inhibition of adipogenesis through MAP kinase-mediated phosphorylation of PPARγ. Science. 1996;274(5295):2100–2103. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qiang L., Wang L., Kon N., et al. Brown remodeling of white adipose tissue by SirT1-dependent deacetylation of Pparγ. Cell. 2012;150(3):620–632. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li J. J., Wang R., Lama R., et al. Ubiquitin ligase NEDD4 regulates PPARγ stability and adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 Cells. Scientific Reports. 2016;6(1) doi: 10.1038/srep38550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watanabe M., Takahashi H., Saeki Y., et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM23 regulates adipocyte differentiation via stabilization of the adipogenic activator PPARγ. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.05615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DaSilva-Arnold S., James J. L., Al-Khan A., Zamudio S., Illsley N. P. Differentiation of first trimester cytotrophoblast to extravillous trophoblast involves an epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Placenta. 2015;36(12):1412–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harris L. K., Jones C. J., Aplin J. D. Adhesion molecules in human trophoblast - a review. II. Extravillous trophoblast. Placenta. 2009;30(4):299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Handschuh K., Guibourdenche J., Tsatsaris V., et al. Human chorionic gonadotropin expression in human trophoblasts from early placenta: comparative study between villous and extravillous trophoblastic cells. Placenta. 2007;28(2-3):175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Naruse K., Innes B. A., Bulmer J. N., Robson S. C., Searle R. F., Lash G. E. Secretion of cytokines by villous cytotrophoblast and extravillous trophoblast in the first trimester of human pregnancy. Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2010;86(2):148–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reka A. K., Kurapati H., Narala V. R., et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activation inhibits tumor metastasis by antagonizing Smad3-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2010;9(12):3221–3232. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Handschuh K., Guibourdenche J., Cocquebert M., et al. Expression and regulation by PPARγ of hCG α- and β-subunits: comparison between villous and invasive extravillous trophoblastic cells. Placenta. 2009;30(12):1016–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ma X., Wang D., Zhao W., Xu L. Deciphering the roles of PPARγ in adipocytes via dynamic change of transcription complex. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamagishi S., Matsui T., Nakamura K., Takeuchi M., Inoue H. Telmisartan inhibits advanced glycation end products (AGEs)-elicited endothelial cell injury by suppressing AGE receptor (RAGE) expression via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gammaactivation. Protein and Peptide Letters. 2008;15(8):850–853. doi: 10.2174/092986608785203746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen J. G., Li X., Huang H. Y., et al. Identification of a peroxisome proliferator responsive element (PPRE)-like cis -element in mouse plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene promoter. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;347(3):821–826. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mandard S., Zandbergen F., Tan N. S., et al. The direct peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor target fasting-induced adipose factor (FIAF/PGAR/ANGPTL4) is present in blood plasma as a truncated protein that is increased by fenofibrate treatment. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(33):34411–34420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403058200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Szatmari I., Vámosi G., Brazda P., et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-regulated ABCG2 expression confers cytoprotection to human dendritic cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(33):23812–23823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604890200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu N., Ahren B., Jiang J., Nilsson-Ehle P. Down-regulation of apolipoprotein M expression is mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in HepG2 cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2006;1761(2):256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leung W. K., Bai A. H., Chan V. Y., et al. Effect of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma ligands on growth and gene expression profiles of gastric cancer cells. Gut. 2004;53(3):331–338. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.021105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baldan A., Relat J., Marrero P. F., Haro D. Functional interaction between peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors-alpha and Mef-2C on human carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1β (CPT1β) gene activation. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32(16):4742–4749. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Park U. H., Yoon S. K., Park T., Kim E. J., Um S. J. Additional sex comb-like (ASXL) proteins 1 and 2 play opposite roles in adipogenesis via reciprocal regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(2):1354–1363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.177816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sarov-Blat L., Kiss R. S., Haidar B., et al. Predominance of a proinflammatory phenotype in monocyte-derived macrophages from subjects with low plasma HDL-cholesterol. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2007;27(5):1115–1122. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.106.138990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rival Y., Stennevin A., Puech L., et al. Human adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein (aP2) gene promoter-driven reporter assay discriminates nonlipogenic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligands. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2004;311(2):467–475. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.068254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Savage D. B., Sewter C. P., Klenk E. S., et al. Resistin / Fizz3 expression in relation to obesity and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma action in humans. Diabetes. 2001;50(10):2199–2202. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.10.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Krönke G., Kadl A., Ikonomu E., et al. Expression of heme oxygenase-1 in human vascular cells is regulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2007;27(6):1276–1282. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.142638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yoon J. C., Chickering T. W., Rosen E. D., et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ target gene encoding a novel angiopoietin-related protein associated with adipose differentiation. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2000;20(14):5343–5349. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.14.5343-5349.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marx N., Bourcier T., Sukhova G. K., Libby P., Plutzky J. PPARγ activation in human endothelial cells increases plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 Expression. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 1999;19(3):546–551. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.19.3.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lan X., Fu L. J., Zhang J., et al. Bisphenol A exposure promotes HTR-8/SVneo cell migration and impairs mouse placentation involving upregulation of integrin-β1 and MMP-9 and stimulation of MAPK and PI3K signaling pathways. Oncotarget. 2017;8(31):51507–51521. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu L., Wang Y., Shen C., et al. Benzo(a)pyrene inhibits migration and invasion of extravillous trophoblast HTR-8/SVneo cells via activation of the ERK and JNK pathway. Journal of Applied Toxicology. 2016;36(7):946–955. doi: 10.1002/jat.3227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cohen M., Meisser A., Haenggeli L., Bischof P. Involvement of MAPK pathway in TNF-α-induced MMP-9 expression in human trophoblastic cells. Molecular Human Reproduction. 2006;12(4):225–232. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee Y., Fryer J. D., Kang H., et al. ATXN1 protein family and CIC regulate extracellular matrix remodeling and lung alveolarization. Developmental Cell. 2011;21(4):746–757. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were selected from the EVCT microarray data under accession number GSE28426 and VCT microarray data under accession number GSE137434. These genes were subsequently enriched according to the gene ontology (GO) terms. The terms of the enriched results were shown in detail in Tables S1-S8. Table S1-S4 shows the terms of GO biological process, GO cellular component, GO molecular function, and pathways of DEGs from the EVCT microarray data, respectively, while Table S5-S8 shows the terms of GO biological process, GO cellular component, GO molecular function, and pathways of DEGs from the VCT microarray data, respectively. Table S1_EVCT_DEGs_Go_Biological Process. Table S2_EVCT_DEGs_Go_Cellular Component. Table S3_EVCT_DEGs_Go_Molecular Function. Table S4_EVCT_DEGs_Pathways. Table S5_VCT_DEGs_Go_Biological Process. Table S6_VCT_DEGs_Go_Cellular Component. Table S7_VCT_DEGs_Go_Molecular Function. Table S8_VCT_DEGs_Pathways.

Data Availability Statement

Our microarray data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus public repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/); EVCT microarray data under accession number GSE28426, VCT microarray data under accession number GSE137434).