Abstract

Background

Antibiotics are highly effective drugs used in the treatment of infectious diseases. Aminoglycoside antibiotics are one of the most common antibiotics in the treatment of bacterial infections. However, the development of drug resistance against those medicines is becoming a serious concern.

Aim

This study aimed to develop an efficient, rapid, accurate, and sensitive detection method that is applicable for routine clinical use.

Methods

Escherichia coli was used as a model organism to develop a rapid, accurate, and reliable multiplex polymerase chain reaction (M-PCR) for the detection of four aminoglycoside modifying enzyme (AME) resistance genes Aac(6′)-Ib, Aac(3)-II, Ant(3″)-Ia, and Aph(3′)-Ia. M-PCR was used to detect the distribution of AME resistance genes in 237 clinical strains of E. coli. The results were verified by simplex polymerase chain reaction (S-PCR).

Results

Results of M-PCR and S-PCR showed that the detection rates of Aac(6′)-Ib, Aac(3)-II, Ant(3″)-Ia, and Aph(3′)-Ia were 32.7%, 59.2%, 23.5%, and 16.8%, respectively, in 237 clinical strains of E. coli. Compared with the traditional methods for detection and identification, the rapid and accurate M-PCR detection method was established to detect AME drug resistance genes. This technique can be used for the clinical detection as well as the surveillance and monitoring of the spread of those specific antibiotic resistance genes.

Keywords: Polymerase chain reaction, Molecular detection, Multiplex polymerase chain reaction, Aminoglycoside modifying enzyme drug resistance gene

Introduction

With the abuse and misuse of antibiotics, bacterial tolerance is becoming an increasingly serious concern (Ferri et al., 2017; Levin-Reisman et al., 2017), leading to the emergence of a series of drug-resistant bacteria (multi-drug-resistance (MDR), extensively-drug-resistant (XDR), and pan-drug-resistant (PDR)) (Healey et al., 2016; Planet, 2017). MDR is defined as acquired non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories. XDR is defined as non-susceptibility to at least one agent in all but two or fewer antimicrobial categories. PDR is defined as non-susceptibility to all agents in all antimicrobial categories (Magiorakos et al., 2012). Aminoglycoside antibiotics (Amikacin, Gentamicin, Tobramycin, Kanamycin, Netilmicin, Streptomycin, and Neomycin) (Doi, Wachino & Arakawa, 2016; Krause et al., 2016; Yadegar et al., 2009) are mainly used to treat infections caused by aerobic Gram-negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, and non-fermenters like Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Jana & Deb, 2006; Magnet & Blanchard, 2005; Zavascki, Klee & Bulitta, 2017). However, bacteria can easily develop tolerance to aminoglycoside antibiotics due to the production of aminoglycoside modifying enzymes (AMEs) (Haidar et al., 2016; Khosravi, Jenabi & Montazeri, 2017) and the rapid transmission of AME resistance genes in pathogenic bacteria (Ramirez & Tolmasky, 2010). The severity of antibiotic tolerance has become a global worldwide concern. The theme of World Health Day in 2011 was “Combat Drug Resistance: No action today, No cure tomorrow” (Chellat, Raguz & Riedl, 2016; Tseng et al., 2012), whereas that in 2018 was “Change Can’t Wait. Our Time with Antibiotics is Running Out”. In such a severe situation of drug resistance, there is an urgent need to identify the species of bacteria and their drug resistance genes accurately and quickly to guide clinical drug use (Brossier et al., 2017; Mu et al., 2016). This need led to the establishment of a rapid, accurate, and economical method to detect pathogens and their drug resistance as early as possible. Such a technique is helpful for the rational use of drugs in clinical practice, as well as of great clinical significance to control and shorten the course of the disease (Laamiri et al., 2016).

Although the traditional method for bacterial resistance identification is simple and economical, identification is completed in about 4–7 days (Jami Al-Ahmadi & Zahmatkesh Roodsari, 2016; Phaneuf et al., 2013). It includes several steps, such as bacterial culture, single colony isolation, colony morphology observation, biochemical identification, and serotype identification (Panek, Frac & Bilinska-Wielgus, 2016). The accuracy of this method is low, and errors easily occur (Tuttle et al., 2011). The main methods used to test drug sensitivity include the disk diffusion method, E-test, dilution method (agar and broth dilution method), and automatic instruments (Biswas, 2016; Ghosh et al., 2015). Such methods have the advantages of low cost, easy operation, and strong flexibility. However, they also feature some inevitable disadvantages, such as slow, empirical dependance. With the development of biological science and technology, many new biological technologies have entered people’s lives. Interspecific and intraspecific conserved nucleic acid sequences have been discovered in succession (Nagar & Hahsler, 2013), and various bioinformatics and molecular biological techniques based on nucleic acid amplification have been used to identify pathogens; an example of such techniques is polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which has become the gold standard (Tuttle et al., 2011).

Multiplex polymerase chain reaction (M-PCR) (Chamberlain et al., 1988) usually means that two or more pairs of primers exist in one PCR reaction system at the same time; it can amplify multiple target bands at one time (Henegariu et al., 1997). Its reaction principle, operation steps, and general composition of the required reagents are basically the same as those of simplex PCR (S-PCR). To date, M-PCR has been widely used in many fields, such as scientific research and disease diagnosis, especially in the simultaneous detection of pathogenic microorganisms, hereditary diseases, and oncogenes (Azizi et al., 2016; Skodvin et al., 2017). What’s more, M-PCR can also be used in the simultaneous detection of multidrug resistance genes in pathogenic bacteria (Hong et al., 2009). Compared with traditional drug sensitivity test and S-PCR, M-PCR is fast, efficient, and able to timely guide the clinical antibiotic therapy (Chavada & Maley, 2015; Lee et al., 2014; Park & Ricke, 2015). M-PCR has higher efficiency than S-PCR, and the former can detect a variety of pathogenic bacteria or drug-resistant genes simultaneously in one reaction system (Kim, Hwang & Kim, 2017). At the same time, M-PCR can reduce any experimental errors that may occurs during the experiment.

Among the AME resistance genes, Aac(6′)-Ib, Aac(3)-II, Ant(3″)-Ia, and Aph(3′)-Ia are the most widely distributed (Costello et al., 2019; Haldorsen et al., 2014; Nasiri et al., 2018; Odumosu, Adeniyi & Chandra, 2015; Ojdana et al., 2018; Vaziri et al., 2011; Xiao & Hu, 2012). Given that the M-PCR can detect multiple genes simultaneously, we aimed to develop a M-PCR system for the detection of the four most widely spread AME genes. The reaction system was verified in 237 clinical E. coli strains.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and culture

The 237 clinical strains of E. coli used in this study were provided, isolated, cultured, and identified by the First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province. All the strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid medium in a shaking incubator at 37 °C and 180 rpm for 12 h. The bacterial genome was extracted using the TIANamp genomic DNA kit following the manufacturer’s protocol and then stored at −40 °C for further experiments.

Search of drug resistance genes searching and design of primers

Four AME resistance genes Aac(6′)-Ib, Ant(3″)-Ia, Aph(3′)-Ia, and Aac(3)-II were downloaded from the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (https://card.mcmaster.ca/). The primers were designed according to the conservative region and synthesized by TSINGKE Biological Technology. The primers sequences are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Primers used in this study.

| Gene | Primers | Sequence (5′–3′) | Product size (bp) | Annealing temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aac(6′)-Ib | Aac(6′)-I-F | AAACCCCGCTTTCTCGTAGC | 112 | 57 |

| Aac(6′)-I-R | AAACCCCGCTTTCTCGTAGC | |||

| Ant(3″)-Ia | Ant(3″)-F | CCGGTTCCTGAACAGGATC | 180 | 59 |

| Ant(3″)-R | CCCAGTCGGCAGCGACATC | |||

| Aph(3′)-Ia | Aph(3′)-F | CAAGATGGATTGCACGCAGG | 317 | 56 |

| Aph(3′)-R | TTCAGTGACAACGTCGAGCA | |||

| Aac(3)-II | Aac(3)-II-F | GCTCGGTTGGATGACAAAGC | 379 | 57 |

| Aac(3)-II-R | AGGCGACTTCACCGTTTCTT |

Establishment of S-PCR reaction system

S-PCR was performed using 2X Tsingke Master Mix, which was purchased from Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd. (Kunming, China). According to the manufacturer’s protocol, the S-PCR reaction system containing 12.5 µL of 2X Tsingke Master Mix, 1 µL of primers (10 µM), and 1 µg of DNA template from each strain was added with nuclease-free water up to 25 µL. The reactions were performed in a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) with the following amplification conditions: pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 57 °C, 59 °C, 56 °C, and 57 °C (Aac(6′)-Ib, Ant(3″)-Ia, Aph(3′)-Ia, and Aac(3)-II) for 30 s; extension at 72 °C for 30 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The S-PCR products were verified using gel electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel and stained with GelStain (Beijing Transgen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China).

Construction and verification of positive plasmids

The positive plasmids with resistance genes were constructed as described in a previous study (Li et al., 2019). In brief, the DNA fragments of the target genes were obtained by PCR reactions using the genomic DNA of E. coli as a template. The target fragment was inserted into the pMD 19-T simple vector and transformed into JM109-competent cells. The positive clones were selected for overnight culture to extract plasmids. Finally, the copies of recombinant plasmids were calculated.

Sensitivity and accuracy evaluation of S-PCR

After the positive plasmids were constructed, the sensitivity of S-PCR reactions was evaluated using the serially diluted 10-fold positive plasmids. According to the resistance gene information of 237 clinical strains of E. coli provided by the First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province, the strains with Aac(6′)-Ib, Ant(3″)-Ia, Aph(3′)-Ia, and Aac(3)-II resistance genes were screened to evaluate accuracy.

Establishment of M-PCR reaction system and accuracy evaluation of M-PCR

The M-PCR was performed by using a Multiplex PCR kit (Nanjing Vazyme Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China). According to the manufacturer’s protocol, the M-PCR reaction system containing 25 µL of 2X Multiplex Buffer, 10 µL of 5X Multiplex GC Enhancer, 1 µL of each primer (10 µM), 1 µL of Multiplex DNA polymerase, and 1 µg of DNA template from each strain, was added with nuclease-free water up to 50 µL. The reactions were performed in a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) with the following amplification conditions: pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 60 °C for 3 min, extension at 72 °C for 3 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 30 min. The M-PCR products were verified by gel electrophoresis on 2% agarose gel and stained with GelStain (Beijing Transgen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China).

Based on the drug sensitivity information of 237 clinical strains of E. coli, five isolates (1611NY0004, 1611UR0282, 1611SP0549, 1611UR0062, and 1611UR0215) previously tested for the Aac(6′)-Ib, Ant(3″)-Ia, Aph(3′)-Ia, and Aac(3)-II by S-PCR were tested for the M-PCR.

Sensitivity evaluation of M-PCR

The sensitivity of M-PCR was performed by using gradient dilution plasmids and bacterial solution. The four equal concentration plasmids with Aac(6′)-Ib, Ant(3″)-Ia, Aph(3′)-Ia, and Aac(3)-II resistance genes were mixed together and serially diluted to 10-fold (108–100). E. coli 1611NY0004 was selected as the representive strain for sensitivity evaluation. The stain was cultured in LB liquid medium to OD600 = 1, and the colony-forming units of bacterial solution were calculated by the plate count method. The bacterial solution was serially diluted as 10-fold (108–100).

M-PCR detection for clinical samples

All the 237 clinical E. coli strains were provided and identified by the First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province and used in the accuracy evaluation of S-PCR and M-PCR.

Results

Establishment of S-PCR reaction system

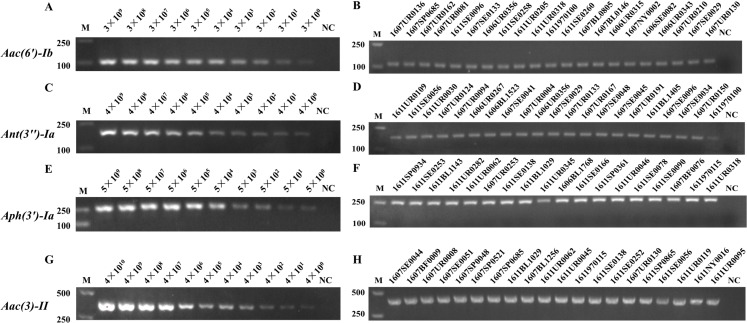

The positive plasmids with drug resistance genes (Aac(6′)-Ib, Ant(3″)-Ia, Aph(3′)-Ia, and Aac(3)-II) were successfully constructed, with 3 × 109, 4 × 109, 5 × 109 and 4 × 1010 copies/μL (114.5, 141.2, 156.8 and 153.2 ng/μL), respectively. The S-PCR reaction template comprised the serially diluted plasmids. Meanwhile, the four drug resistance genes were detected in the 237 clinical strains of E. coli, and the bacterial solution was the S-PCR template. As shown in Fig. 1, the limitation for the detection of the four drug resistance genes was 100 copies/μL. The accuracy rate for the detection of drug resistance genes was 100% (partially representative results), which was consistent with the hospital data (Table S1).

Figure 1. The sensitivity and accuracy evaluation of Aac(6′)-Ib, Ant(3″)-Ia, Aph(3′)-Ia, and Aac(3)-II resistance genes by S-PCR.

The serially diluted positive plasmids with resistance gene were used as the template in the sensitivity evaluation of S-PCR. (A) Aac(6′)-Ib, 3 × 109−3 × 100 copies/µL. (C) Ant(3″)-Ia, 4 × 109−4 × 100 copies/µL. (E) Aph(3′)-Ia, 5 × 109−5 × 100 copies/µL. (G) Aac(3)-II, 4 × 1010−4 × 100 copies/µL. Meanwhile, the four resistance genes were detected in the 237 clinical strains of E. coli respectively, the bacterial solution as the S-PCR template. (B) The accuracy evaluation of Aac(6′)-Ib resistance genes. (D) The accuracy evaluation of Ant(3″)-Ia resistance genes. (F) The accuracy evaluation of Aph(3′)-Ia resistance genes. (H) The accuracy evaluation of Aac(3)-II resistance genes. All experiments were repeated six times. The nuclease-free water used as template for NC (Negative control). M, marker.

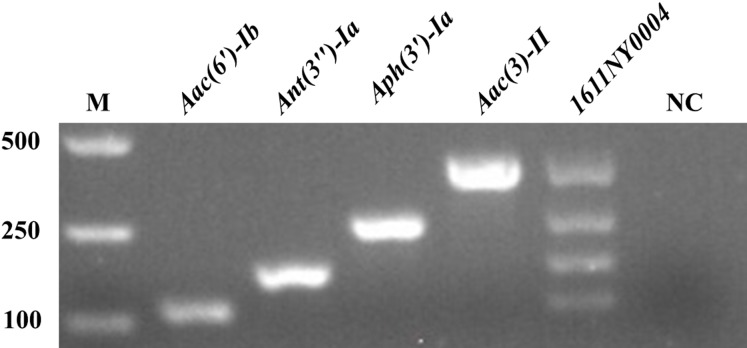

Establishment of M-PCR reaction system

After the S-PCR reaction system was established and optimized (data not shown), the M-PCR reaction system was constructed. As shown in Fig. 2, Aac(6′)-Ib, Ant(3″)-Ia, Aph(3′)-Ia, and Aac(3)-II with 112, 180, 317, and 379 bp, respectively, were amplified successfully. E. coli 1611NY0004 with the four drug resistance genes was used as the positive control template for the M-PCR reaction. In the M-PCR reaction system, the four drug resistance genes could be amplified well simultaneously.

Figure 2. Establishment of M-PCR reaction system.

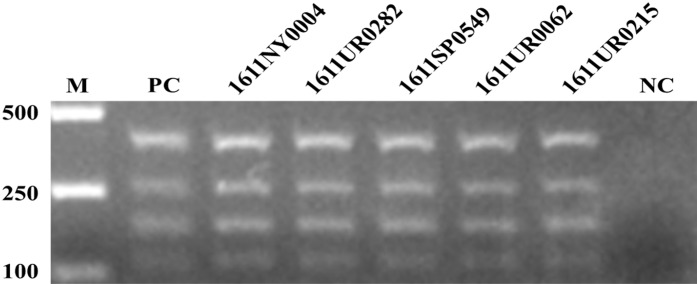

Accuracy evaluation of M-PCR

The five clinical E. coli strains (1611NY0004, 1611UR0282, 1611SP0549, 1611UR0062, and 1611UR0215) with four resistance genes were screened for the accuracy evaluation of M-PCR. The four equal concentration plasmids with Aac(6′)-Ib, Ant(3″)-Ia, Aph(3′)-Ia, and Aac(3)-II resistance genes were mixed together as the positive control. As shown in Fig. 3, the four resistance genes were successfully amplified by M-PCR in the tested strains, which was consistent with the resistance gene information provided by the hospital.

Figure 3. The accuracy evaluation of M-PCR.

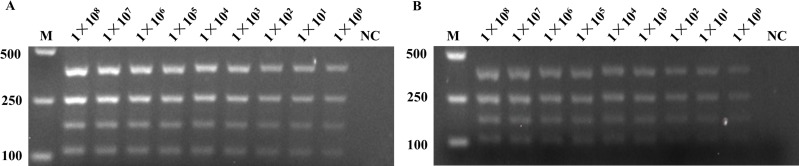

Sensitivity evaluation of M-PCR

The gradient dilution of plasmids and bacterial solution was used in the sensitivity evaluation of M-PCR. The gradient dilution of plasmids was the mixture of the four equal concentration plasmids with Aac(6′)-Ib, Ant(3″)-Ia, Aph(3′)-Ia, and Aac(3)-II resistance gene and then serially diluted as 10-fold (108–100 copies/mL). The E. coli 1611NY0004 strain was used in the gradient 10-fold (108–100 CFU/mL) dilution of bacterial solution for sensitivity evaluation. As shown in Fig. 4, the detection system could reach the detection limit of 100 copies/mL or 100 CFU/mL at the plasmid level and bacterial liquid level.

Figure 4. The sensitivity evaluation of M-PCR.

The gradient dilution of plasmids and bacterial solution was used in the sensitivity evaluation of M-PCR. (A) The four equal concentration plasmids with Aac(6′)-Ib, Ant(3″)-Ia, Aph(3′)-Ia, and Aac(3)-II resistance genes were mixed, and serially diluted as 10-fold (1 × 108−1 × 100), as the sensitivity evaluation of M-PCR. The nuclease-free water used in lane 10 as template for NC. (B) The E. coli 1611NY0004 strain with four resistance genes was used as the template for the the sensitivity evaluation of M-PCR. The bacterial solution was serially diluted as 10-fold (1 × 108−1 × 100). The nuclease-free water used in lane 10 as template for NC. NC, negative control; M, marker.

Detection of clinical samples by multiplex PCR

All the 237 E. coli strains were detected by S-PCR and M-PCR. The detection results and the accuracy are shown in Table S1. The results showed that the detection rates of Aac(6′)-Ib, Aac(3)-II, Ant(3″)-Ia, and Aph(3′)-Ia were 32.7%, 59.2%, 23.5% and 16.8% in 237 clinical strains of E. coli, respectively. These values were consistent with the gene information of the strains given by the hospital.

Discussion

Antibiotics are considered the most effective drugs in the treatment of infectious diseases (Elder, Kuentz & Holm, 2016). The emergence of antibiotics changed the outcome of infectious diseases and extended life expectancy (Wagner & Maynard, 2018). However, given the overuse and misuse of antibiotics, MDR strains have emerged (Elder, Kuentz & Holm, 2016). Therefore, rapid and accurate methods for the detection of bacterial resistance are urgently needed, and the use of antibiotics or antibiotic therapy should be more standardized and technically, where possible, monitored. With the development of molecular biology and bioinformatics, the detection methods of bacterial drug resistance genes, including PCR, loop-mediated isothermal amplification, and whole genome sequencing (WGS) (Moran et al., 2017; Su, Satola & Read, 2019), have increased (Tamburro & Ripabelli, 2017). Although WGS is gradually reaching maturity, while sequencing costs are drastically decreasing, it is however still relatively costly, complex in operation and requires for analysis specialized personnel like bioinformaticians, which limits its popularization and application (Quainoo et al., 2017). M-PCR is widely used in the identification and drug resistance detection of bacteria for its rapid, sensitive, economy-friendly and high-effect characteristics (Pham et al., 2017).

Aminoglycoside antibiotics are one of the most widely used antibiotics, and the main reason for aminoglycoside antibiotic resistance is the production of AME. Aminoglycoside antibiotic resistance is related to the AME drug resistance genes Aac(6′)-Ib, Aac(3)-II, Ant(3″)-Ia, and Aph(3′)-Ia (Zarate et al., 2018). Thus, this study designed primers for the four drug resistance genes and constructed a four-drug resistance genes detection system, which greatly improved the detection efficiency and shortened the detection time.

The MDR gene detection system was established successfully in this experiment, and it exhibited the advantages of high efficiency, rapidity, and high performance-to-price ratio compared with the S-PCR reaction system. The MDR gene detection system also fully met the requirements for the clinical detection of pathogens and drug resistance. In this experiment, the four drug-resistant genes were identified in the five representative E. coli MDR bacteria by M-PCR. The results obtained by M-PCR were consistent with those of S-PCR, thereby indicating the accuracy of M-PCR. The M-PCR detection system was applied to the detection of 237 clinical strains of E. coli. On the basis of the drug resistance gene information given by the hospital, the accuracy rate of M-PCR could reach 100%; the detection rates of Aac(6′)-Ib, Aac(3)-II, Ant(3″)-Ia, and Aph(3′)-Ia were 32.7%, 59.2%, 23.5% and 16.8%, respectively. These findings indicated the potential of reintroducing additional resistant genes into the M-PCR system to detect numerous genes at a time. Even the specific genes of the bacteria could be added into the M-PCR system for the identification of bacterial species. From the detection rate of the four aminoglycoside modifying enzyme resistance genes, Aac(3)-II had the highest detection rate in the 237 clinical strains of E. coli. This result suggested that the resistance of three aminoglycoside antibiotics gentamicin, tobramycin, and netilmicin resistance is widespread in bacterial infections and should be avoided.

Conclusion

The M-PCR system developed in this study could amplify the four genes with very extremely high sensitivity to 100 copies. The sensitivity rate of M-PCR was higher than that of most previously reported studies, which proved the sensitivity of this technique. Moreover, the M-PCR detection method greatly reduced the detection time and improved the detection efficiency. M-PCR in this study demonstrated high sensitivity and efficiency, low price, and other characteristics but not one-to-one correspondence between genotype and phenotype. Therefore, simply detecting genes failed to completely determine the phenotype, but the four genes selected genes had the highest prevalence of aminoglycoside antibiotic resistance. We conducted the simultaneous detection of these four genes to compensate for the limitations of detecting one gene, thereby making our methodology reliable and persuasive. Our method was established to assist medical institutions to predict drug resistance, to provide an accurate direction for clinical drug selection, and to meet the needs of both doctors and patients for rapid diagnosis. In the future, we will propose a rapid drug sensitivity identification technique based on phenotype. We will also combine traditional detection methods with modern molecular techniques, starting from the phenotype, for the accurate identification of bacterial drug resistance.

Supplemental Information

Note: SPEC_NUM and SPEC_TYPE means the specimen number and type. AMK_NM, GEN_NM, and TOB_NM means the resistance of amikacin, gentamicin, and tobramycin antibiotics. SP, UR, SE, BF,DG, BL, SW, ST means the sputum, clearing urine, secretion, excreta, blood, surgical incision, and stool of the patients, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the strains donated and the drug resistant information provided by the First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Yunnan Science and Technology Commission (grant numbers: 2015BC001, 2015DH010). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

A-Mei Zhang, Email: zam1980@yeah.net.

Yuzhu Song, Email: yuzhusong@kmust.edu.cn.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Yaoqiang Shi performed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft.

Chao Li performed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft.

Guangying Yang analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft.

Xueshan Xia analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Xiaoqin Mao analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Yue Fang analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

A-Mei Zhang conceived and designed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Yuzhu Song conceived and designed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

Raw data is available in Table S1.

References

- Azizi et al. (2016).Azizi O, Shahcheraghi F, Salimizand H, Modarresi F, Shakibaie MR, Mansouri S, Ramazanzadeh R, Badmasti F, Nikbin V. Molecular analysis and expression of bap gene in biofilm-forming multi-drug-resistant acinetobacter baumannii. Reports of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2016;5:62–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas (2016).Biswas B. Clinical performance evaluation of molecular diagnostic tests. Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 2016;18(6):803–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brossier et al. (2017).Brossier F, Sougakoff W, Aubry A, Bernard C, Cambau E, Jarlier V, Mougari F, Raskine L, Robert J, Veziris N. Molecular detection methods of resistance to antituberculosis drugs in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses. 2017;47(5):340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain et al. (1988).Chamberlain JS, Gibbs RA, Ranier JE, Nguyen PN, Caskey CT. Deletion screening of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus via multiplex DNA amplification. Nucleic Acids Research. 1988;16(23):11141–11156. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.23.11141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavada & Maley (2015).Chavada R, Maley M. Evaluation of a commercial multiplex PCR for rapid detection of multi drug resistant gram negative infections. Open Microbiology Journal. 2015;9(1):125–135. doi: 10.2174/1874285801509010125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chellat, Raguz & Riedl (2016).Chellat MF, Raguz L, Riedl R. Targeting antibiotic resistance. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2016;55(23):6600–6626. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello et al. (2019).Costello SE, Deshpande LM, Davis AP, Mendes RE, Castanheira M. Aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme and 16S ribosomal RNA methyltransferase genes among a global collection of Gram-negative isolates. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance. 2019;16:278–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi, Wachino & Arakawa (2016).Doi Y, Wachino JI, Arakawa Y. Aminoglycoside resistance: the emergence of acquired 16S ribosomal RNA methyltransferases. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 2016;30(2):523–537. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder, Kuentz & Holm (2016).Elder DP, Kuentz M, Holm R. Antibiotic resistance: the need for a global strategy. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2016;105(8):2278–2287. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri et al. (2017).Ferri M, Ranucci E, Romagnoli P, Giaccone V. Antimicrobial resistance: a global emerging threat to public health systems. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2017;57(13):2857–2876. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2015.1077192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh et al. (2015).Ghosh R, Nagavardhini A, Sengupta A, Sharma M. Development of loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay for rapid detection of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris—wilt pathogen of chickpea. BMC Research Notes. 2015;8(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-0997-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidar et al. (2016).Haidar G, Alkroud A, Cheng S, Churilla TM, Churilla BM, Shields RK, Doi Y, Clancy CJ, Nguyen MH. Association between the presence of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes and in vitro activity of gentamicin, tobramycin, amikacin, and plazomicin against klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase- and Extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing enterobacter species. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2016;60:5208–5214. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00869-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldorsen et al. (2014).Haldorsen BC, Simonsen GS, Sundsfjord A, Samuelsen O, Norwegian Study Group on Aminoglycoside R Increased prevalence of aminoglycoside resistance in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. in Norway is associated with the acquisition of AAC(3)-II and AAC(6′)-Ib. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2014;78:66–69. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey et al. (2016).Healey KR, Zhao Y, Perez WB, Lockhart SR, Sobel JD, Farmakiotis D, Kontoyiannis DP, Sanglard D, Taj-Aldeen SJ, Alexander BD, Jimenez-Ortigosa C, Shor E, Perlin DS. Prevalent mutator genotype identified in fungal pathogen Candida glabrata promotes multi-drug resistance. Nature Communications. 2016;7(1):11128. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henegariu et al. (1997).Henegariu O, Heerema NA, Dlouhy SR, Vance GH, Vogt PH. Multiplex PCR: critical parameters and step-by-step protocol. Biotechniques. 1997;23(3):504–511. doi: 10.2144/97233rr01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong et al. (2009).Hong Y, Liu T, Lee MD, Hofacre CL, Maier M, White DG, Ayers S, Wang L, Berghaus R, Maurer J. A rapid screen of broth enrichments for Salmonella enterica serovars enteritidis, Hadar, Heidelberg, and Typhimurium by Using an allelotyping multiplex PCR that targets O- and H-antigen alleles. Journal of Food Protection. 2009;72(10):2198–2201. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-72.10.2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jami Al-Ahmadi & Zahmatkesh Roodsari (2016).Jami Al-Ahmadi G, Zahmatkesh Roodsari R. Fast and specific detection of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa from other pseudomonas species by PCR. Annals of Burns and Fire Disasters. 2016;29:264–267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana & Deb (2006).Jana S, Deb JK. Molecular understanding of aminoglycoside action and resistance. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2006;70(2):140–150. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0279-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosravi, Jenabi & Montazeri (2017).Khosravi AD, Jenabi A, Montazeri EA. Distribution of genes encoding resistance to aminoglycoside modifying enzymes in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains. Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences. 2017;33(12):587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hwang & Kim (2017).Kim TH, Hwang HJ, Kim JH. Development of a novel, rapid multiplex polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection and differentiation of Salmonella enterica serovars enteritidis and typhimurium using ultra-fast convection polymerase chain reaction. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 2017;14(10):580–586. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2017.2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause et al. (2016).Krause KM, Serio AW, Kane TR, Connolly LE. Aminoglycosides: an overview. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2016;6(6):a027029. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a027029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laamiri et al. (2016).Laamiri N, Fallgren P, Zohari S, Ben Ali J, Ghram A, Leijon M, Hmila I. Accurate detection of avian respiratory viruses by use of multiplex PCR-based luminex suspension microarray assay. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2016;54(11):2716–2725. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00610-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee et al. (2014).Lee N, Kwon KY, Oh SK, Chang HJ, Chun HS, Choi SW. A multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous detection of Escherichia coli O157: H7, Bacillus cereus, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Salmonella spp., Listeria monocytogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus in Korean ready-to-eat food. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 2014;11(7):574–580. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2013.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin-Reisman et al. (2017).Levin-Reisman I, Ronin I, Gefen O, Braniss I, Shoresh N, Balaban NQ. Antibiotic tolerance facilitates the evolution of resistance. Science. 2017;355(6327):826–830. doi: 10.1126/science.aaj2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al. (2019).Li C, Shi Y, Yang G, X-s Xia, Mao X, Fang Y, Zhang A-M, Song Y. Establishment of loop‑mediated isothermal amplification for rapid detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2019;6:131–136. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magiorakos et al. (2012).Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B, Paterson DL, Rice LB, Stelling J, Struelens MJ, Vatopoulos A, Weber JT, Monnet DL. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2012;18(3):268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnet & Blanchard (2005).Magnet S, Blanchard JS. Molecular insights into aminoglycoside action and resistance. Chemical Reviews. 2005;105(2):477–498. doi: 10.1021/cr0301088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran et al. (2017).Moran RA, Anantham S, Holt KE, Hall RM. Prediction of antibiotic resistance from antibiotic resistance genes detected in antibiotic-resistant commensal Escherichia coli using PCR or WGS. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2017;72:700–704. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu et al. (2016).Mu XQ, Liu BB, Hui E, Huang W, Yao LC, Duo LB, Sun WY, Li GQ, Wang FX, Liu SL. A rapid loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) method for detection of the macrolide-streptogramin type B resistance gene msrA in Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance. 2016;7:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagar & Hahsler (2013).Nagar A, Hahsler M. Fast discovery and visualization of conserved regions in DNA sequences using quasi-alignment. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14(S11):403. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-S11-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasiri et al. (2018).Nasiri G, Peymani A, Farivar TN, Hosseini P. Molecular epidemiology of aminoglycoside resistance in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae collected from Qazvin and Tehran provinces. Iran Infection Genetics and Evolution. 2018;64:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odumosu, Adeniyi & Chandra (2015).Odumosu BT, Adeniyi BA, Chandra R. Occurrence of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes genes (aac(6′)-I and ant(2″)-I) in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Southwest Nigeria. African Health Sciences. 2015;15(4):1277–1281. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v15i4.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojdana et al. (2018).Ojdana D, Sienko A, Sacha P, Majewski P, Wieczorek P, Wieczorek A, Tryniszewska E. Genetic basis of enzymatic resistance of E. coli to aminoglycosides. Advances in Medical Sciences. 2018;63(1):9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.advms.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panek, Frac & Bilinska-Wielgus (2016).Panek J, Frac M, Bilinska-Wielgus N. Comparison of chemical sensitivity of fresh and long-stored heat resistant neosartorya fischeri environmental isolates using BIOLOG phenotype microarray system. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(1):e0147605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park & Ricke (2015).Park SH, Ricke SC. Development of multiplex PCR assay for simultaneous detection of Salmonella genus, Salmonella subspecies I, Salm. Enteritidis, Salm. Heidelberg and Salm. Typhimurium. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2015;118(1):152–160. doi: 10.1111/jam.12678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham et al. (2017).Pham NT, Ushijima H, Thongprachum A, Trinh QD, Khamrin P, Arakawa C, Ishii W, Okitsu S, Komine-Aizawa S, Hayakawa S. Multiplex PCR for the detection of 10 viruses causing encephalitis/encephalopathy and its application to clinical samples collected from Japanese Children with suspected viral. Clinical Laboratory. 2017;63:91–100. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2016.160630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phaneuf et al. (2013).Phaneuf CR, Oh K, Pak N, Saunders DC, Conrardy C, Landers JP, Tong S, Forest CR. Sensitive, microliter PCR with consensus degenerate primers for Epstein Barr virus amplification. Biomedical Microdevices. 2013;15(2):221–231. doi: 10.1007/s10544-012-9720-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planet (2017).Planet PJ. Life after USA300: the rise and fall of a superbug. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2017;215(Suppl. 1):S71–S77. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quainoo et al. (2017).Quainoo S, Coolen JPM, Van Hijum S, Huynen MA, Melchers WJG, Van Schaik W, Wertheim HFL. Whole-Genome Sequencing of Bacterial Pathogens: the Future of Nosocomial Outbreak Analysis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2017;30(4):1015–1063. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00016-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez & Tolmasky (2010).Ramirez MS, Tolmasky ME. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. Drug Resistance Updates. 2010;13(6):151–171. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodvin et al. (2017).Skodvin B, Aase K, Brekken AL, Charani E, Lindemann PC, Smith I. Addressing the key communication barriers between microbiology laboratories and clinical units: a qualitative study. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2017;72(9):2666–2672. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, Satola & Read (2019).Su M, Satola SW, Read TD. Genome-based prediction of bacterial antibiotic resistance. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2019;57(9):336. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00352-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamburro & Ripabelli (2017).Tamburro M, Ripabelli G. High resolution melting as a rapid, reliable, accurate and cost-effective emerging tool for genotyping pathogenic bacteria and enhancing molecular epidemiological surveillance: a comprehensive review of the literature. Annali di Igiene. 2017;29:293–316. doi: 10.7416/ai.2017.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng et al. (2012).Tseng SH, Lee CM, Lin TY, Chang SC, Chuang YC, Yen MY, Hwang KP, Leu HS, Yen CC, Chang FY. Combating antimicrobial resistance: antimicrobial stewardship program in Taiwan. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. 2012;45(2):79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuttle et al. (2011).Tuttle MS, Mostow E, Mukherjee P, Hu FZ, Melton-Kreft R, Ehrlich GD, Dowd SE, Ghannoum MA. Characterization of bacterial communities in venous insufficiency wounds by use of conventional culture and molecular diagnostic methods. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2011;49(11):3812–3819. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00847-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri et al. (2011).Vaziri F, Peerayeh SN, Nejad QB, Farhadian A. The prevalence of aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme genes (aac (6′)-I, aac (6′)-II, ant (2″)-I, aph (3′)-VI) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66:1519–1522. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000900002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner & Maynard (2018).Wagner EK, Maynard JA. Engineering therapeutic antibodies to combat infectious diseases. Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering. 2018;19:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.coche.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao & Hu (2012).Xiao Y, Hu Y. The major aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme AAC(3)-II found in Escherichia coli determines a significant disparity in its resistance to gentamicin and amikacin in China. Microbial Drug Resistance. 2012;18(1):42–46. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2010.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadegar et al. (2009).Yadegar A, Sattari M, Mozafari NA, Goudarzi GR. Prevalence of the genes encoding aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes and methicillin resistance among clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus in Tehran. Iran Microbial Drug Resistance. 2009;15(2):109–113. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2009.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarate et al. (2018).Zarate SG, De la Cruz Claure ML, Benito-Arenas R, Revuelta J, Santana AG, Bastida A. Overcoming aminoglycoside enzymatic resistance: design of novel antibiotics and inhibitors. Molecules. 2018;23(2):284. doi: 10.3390/molecules23020284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavascki, Klee & Bulitta (2017).Zavascki AP, Klee BO, Bulitta JB. Aminoglycosides against carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae in the critically ill: the pitfalls of aminoglycoside susceptibility. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 2017;15(6):519–526. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2017.1316193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Note: SPEC_NUM and SPEC_TYPE means the specimen number and type. AMK_NM, GEN_NM, and TOB_NM means the resistance of amikacin, gentamicin, and tobramycin antibiotics. SP, UR, SE, BF,DG, BL, SW, ST means the sputum, clearing urine, secretion, excreta, blood, surgical incision, and stool of the patients, respectively.

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

Raw data is available in Table S1.