Key Points

Question

Does Klotho-VS heterozygosity protect against Alzheimer disease (AD) in individuals who carry APOE4?

Findings

In this study, associations were evaluated across 22 AD cohorts (n = 20 928), 3 longitudinal cohorts (n = 3008), and 4 cohorts collecting β-amyloid measurements (cerebrospinal fluid, n = 556; brain, n = 251). In individuals who carry APOE4, Klotho-VS heterozygosity was associated with reduced AD risk and more favorable β-amyloid profiles in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid of older control participants. Klotho-VS heterozygosity was also associated with reduced AD conversion risk in individuals who carry APOE4.

Meaning

Pathways associated with KL merit exploration for novel AD drug targets, and the KL-VS genotype should be considered in conjunction with APOE genotype to refine prediction models used in clinical trial enrichment.

This study combined data from 35 independent case-control, family-based, and longitudinal cohorts that examined Alzheimer disease to determine if Klotho-VS heterozygosity is associated with reduced Alzheimer disease risk and β-amyloid (Aβ) pathology in individuals who carry APOE4.

Abstract

Importance

Identification of genetic factors that interact with the apolipoprotein e4 (APOE4) allele to reduce risk for Alzheimer disease (AD) would accelerate the search for new AD drug targets. Klotho-VS heterozygosity (KL-VSHET+ status) protects against aging-associated phenotypes and cognitive decline, but whether it protects individuals who carry APOE4 from AD remains unclear.

Objectives

To determine if KL-VSHET+ status is associated with reduced AD risk and β-amyloid (Aβ) pathology in individuals who carry APOE4.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study combined 25 independent case-control, family-based, and longitudinal AD cohorts that recruited referred and volunteer participants and made data available through public repositories. Analyses were stratified by APOE4 status. Three cohorts were used to evaluate conversion risk, 1 provided longitudinal measures of Aβ CSF and PET, and 3 provided cross-sectional measures of Aβ CSF. Genetic data were available from high-density single-nucleotide variant microarrays. All data were collected between September 2015 and September 2019 and analyzed between April 2019 and December 2019.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The risk of AD was evaluated through logistic regression analyses under a case-control design. The risk of conversion to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or AD was evaluated through competing risks regression. Associations with Aβ, measured from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or brain positron emission tomography (PET), were evaluated using linear regression and mixed-effects modeling.

Results

Of 36 530 eligible participants, 13 782 were excluded for analysis exclusion criteria or refusal to participate. Participants were men and women aged 60 years and older who were non-Hispanic and of Northwestern European ancestry and had been diagnosed as being cognitively normal or having MCI or AD. The sample included 20 928 participants in case-control studies, 3008 in conversion studies, 556 in Aβ CSF regression analyses, and 251 in PET regression analyses. The genotype KL-VSHET+ was associated with reduced risk for AD in individuals carrying APOE4 who were 60 years or older (odds ratio, 0.75 [95% CI, 0.67-0.84]; P = 7.4 × 10−7), and this was more prominent at ages 60 to 80 years (odds ratio, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.61-0.79]; P = 3.6 × 10−8). Additionally, control participants carrying APOE4 with KL-VS heterozygosity were at reduced risk of converting to MCI or AD (hazard ratio, 0.64 [95% CI, 0.44-0.94]; P = .02). Finally, in control participants who carried APOE4 and were aged 60 to 80 years, KL-VS heterozygosity was associated with higher Aβ in CSF (β, 0.06 [95% CI, 0.01-0.10]; P = .03) and lower Aβ on PET scans (β, −0.04 [95% CI, −0.07 to −0.00]; P = .04).

Conclusions and Relevance

The genotype KL-VSHET+ is associated with reduced AD risk and Aβ burden in individuals who are aged 60 to 80 years, cognitively normal, and carrying APOE4. Molecular pathways associated with KL merit exploration for novel AD drug targets. The KL-VS genotype should be considered in conjunction with the APOE genotype to refine AD prediction models used in clinical trial enrichment and personalized genetic counseling.

Introduction

Klotho (KL) is a transmembrane protein and longevity factor implicated in reducing aging-associated phenotypes and cognitive decline.1,2 Two KL missense variants (F352V [rs9536314] and C370S [rs9527025]), in perfect linkage disequilibrium, form a functional haplotype known as KL-VS. Specifically, heterozygosity for KL-VS (KL-VSHET+ status) has been shown to increase serum levels of KL and exert protective effects on healthy aging and longevity when compared with individuals who are homozygotes for the major or minor alleles (KL-VSHET−).2,3,4,5 It currently remains unclear if KL-VSHET+ status also provides protection against aging-associated neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer disease (AD).

The apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4) allele is the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset AD.6 The most established pathogenic effect of APOE4 is β-amyloid (Aβ) accumulation in the brain, which correlates with decreased Aβ in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).7,8 Brain Aβ accumulation likely represents a central early step in AD pathogenesis9; Aβ accumulates before symptom onset in individuals during early old age (60-80 years) before it reaches plateau levels and individuals convert to experiencing mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and/or AD.10,11,12 Over this age range, Aβ accumulation and correlated cognitive decline are most prominent in individuals who carry APOE4.13,14,15,16 Similarly, during this time, APOE4 is most strongly associated with AD risk.17,18,19 In the search for new AD drug targets, it is thus critical to identify genetic factors that interact with APOE4 to reduce risk for AD by lowering Aβ burden.20

Two recent studies evaluated whether KL-VSHET+ status confers protection against AD in individuals who were cognitively normal. One cohort study21 (N = 309; mean age, 61 years) showed that KL-VSHET+ status reduced Aβ burden in individuals who carry APOE4. The second cohort study22 (N = 581; mean age, 71 years) showed that KL-VSHET+ did not protect against cognitive decline, and this was not modulated by APOE4 status. Here, we test on a larger scale and across the age span older than 60 years whether KL-VSHET+ status is associated with reduced risk for AD and conversion to MCI or AD. We also reevaluate in larger samples the putative protective association of KL-VSHET+ status with Aβ burden assessed by CSF and positron emission tomography (PET) scanning measures. Similar to the prior studies, we stratified analyses by APOE4 status to determine if the associations of KL-VS with outcome measures are specific to individuals who carry APOE4. Because the role of APOE4 in AD is most pronounced between age 60 to 80 years and genetic risk varies importantly in relatively younger individuals (60-80 years) compared with older individuals (≥80 years),23 we also tested the hypothesis that the associations of KL-VSHET+ status with AD risk would differ between those aged 60 to 80 years and those older than 80 years.

Methods

Ascertainment of Genotype and Phenotype Data

Twenty-two late-onset AD cohorts with genotype data were used for case-control analyses (Table 1).24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 Ascertainment and collection of genotype and phenotype data for each cohort are summarized in the eMethods in the Supplement and described in detail elsewhere.38 The National Alzheimer Coordinating Center’s Alzheimer’s Disease Center data sets 1 through 7 (NACC [ADC1-7]) and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) and Religious Orders Study and Memory and Aging Project (ROSMAP) longitudinal cohorts provided data on the age at MCI or AD diagnosis and were used in conversion-risk analyses. Genotyping was performed using various high-density single-nucleotide variant (formerly single-nucleotide polymorphism) microarrays across cohorts (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Participants or their caregivers provided written informed consent in the original studies.

Table 1. Demographics of Cohorts Used in the Alzheimer Disease Case-Control Regression Analysis.

| Cohort | Diagnosis | Female, No. (%) | Age, mean (SD) [%] | Age, No. (%), y | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Namea | Participants after quality control, No. | Type | No. | At death | At last visit | At examinationb | At onsetc | 60-80 y | ≥80 y | |||

| All | APOE4+ | All | APOE4+ | |||||||||

| ACT | 2132 | CN | 1604 | 881 (54.9) | 83.6 (5.7) [56.9] | 80.3 (5.9) [43.1] | NA | NA | 630 | 144 (22.9) | 974 | 199 (20.4) |

| AD | 528 | 342 (64.8) | 86.0 (3.5) [0.6] | NA | 83.1 (5.2) [20.6] | 80.7 (6.6) [78.8] | 232 | 138 (59.5) | 296 | 99 (33.4) | ||

| NACC | ||||||||||||

| ADC1 | 1790 | CN | 404 | 243 (60.1) | 85.5 (8.6) [38.4] | 78.0 (8.4) [61.6] | NA | NA | 196 | 68 (34.7) | 208 | 36 (17.3) |

| AD | 1386 | 770 (55.6) | 83.5 (6.3) [1.40] | NA | 79.7 (8.7) [7.4] | 72.4 (7.2) [91.3] | 1155 | 830 (71.9) | 231 | 122 (52.8) | ||

| ADC2 | 705 | CN | 105 | 72 (68.6) | 86.1 (7.0) [19.0] | 78.8 (9.4) [81.0] | NA | NA | 54 | 19 (35.2) | 51 | 8 (15.7) |

| AD | 600 | 317 (52.8) | NA | NA | 77.2 (7.5) [1.5] | 72.9 (7.0) [98.5] | 518 | 370 (71.4) | 82 | 30 (36.6) | ||

| ADC3 | 1036 | CN | 380 | 238 (62.6) | 88.8 (8.1) [20.0] | 77.6 (8.5) [80.0] | NA | NA | 209 | 59 (28.2) | 171 | 26 (15.2) |

| AD | 656 | 368 (56.1) | 99.0 (NA) [0.2] | NA | 80.4 (8.8) [4.9] | 74.3 (8.1) [95.0] | 512 | 367 (71.7) | 144 | 56 (38.9) | ||

| ADC4 | 629 | CN | 325 | 200 (61.5) | 86.9 (8.2) [19.4] | 77.8 (7.6) [80.6] | NA | NA | 174 | 57 (32.8) | 151 | 26 (17.2) |

| AD | 304 | 164 (53.9) | NA | NA | 72.5 (0.7) [0.7] | 73.4 (7.0) [99.3] | 257 | 173 (67.3) | 47 | 7 (14.9) | ||

| ADC5 | 807 | CN | 498 | 336 (67.5) | 89.0 (6.4) [20.3] | 80.2 (8.3) [79.7] | NA | NA | 222 | 58 (26.1) | 276 | 52 (18.8) |

| AD | 309 | 170 (55.0) | NA | NA | NA | 73.4 (7.3) [100] | 259 | 193 (74.5) | 50 | 21 (42.0) | ||

| ADC6 | 535 | CN | 253 | 182 (71.9) | 86.8 (8.6) [20.6] | 77.6 (7.9) [79.4] | NA | NA | 149 | 52 (34.9) | 104 | 20 (19.2) |

| AD | 282 | 154 (54.6) | NA | NA | NA | 73.7 (7.6) [100] | 233 | 161 (69.1) | 49 | 14 (28.6) | ||

| ADC7 | 1035 | CN | 601 | 395 (65.7) | 84.1 (8.4) [9.0] | 76.5 (7.4) [91.0] | NA | NA | 404 | 132 (32.7) | 197 | 52 (26.4) |

| AD | 434 | 236 (54.4) | NA | NA | NA | 72.3 (7.6) [100] | 371 | 262 (70.6) | 63 | 29 (46.0) | ||

| ADDNEURO | 239 | CN | 115 | 64 (55.7) | NA | 78.5 (7.2) [100] | NA | NA | 77 | 23 (29.9) | 38 | 9 (23.7) |

| AD | 124 | 77 (62.1) | NA | NA | 79.8 (6.6) [9.7] | 73.3 (6.9) [90.3] | 101 | 67 (66.3) | 23 | 9 (39.1) | ||

| ADNI | 724 | CN | 291 | 149 (51.2) | 84.0 (0.3) | 78.2 (6.8) [99.7] | NA | NA | 188 | 62 (33.0) | 103 | 22 (21.4) |

| AD | 433 | 183 (42.3) | NA | NA | 75.2 (6.6) [100] | NA | 340 | 251 (73.8) | 93 | 49 (52.7) | ||

| ADOD | 72 | CN | 72 | 0 | NA | 70.3 (5.3) [100] | NA | NA | 69 | 17 (24.6) | 3 | 1 (33.3) |

| AD | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| GenADA | 1371 | CN | 687 | 436 (63.5) | NA | 74.3 (7.1) [100] | NA | NA | 545 | 131 (24.0) | 142 | 34 (23.9) |

| AD | 684 | 398 (58.2) | NA | NA | 85.2 (6.4) [2.2] | 73.7 (6.7) [97.8] | 576 | 390 (67.7) | 108 | 51 (47.2) | ||

| NIA-LOAD | 1693 | CN | 718 | 443 (61.7) | 85.9 (5.9) [2.9] | 74.8 (7.8) [97.1] | NA | NA | 556 | 190 (34.2) | 162 | 36 (22.2) |

| AD | 975 | 631 (64.7) | NA | NA | 80.3 (8.0) [0.9] | 72.2 (6.7) [99.1] | 881 | 705 (80.0) | 94 | 38 (40.4) | ||

| MAYO | 1738 | CN | 1079 | 557 (51.6) | NA | 73.3 (4.3) [100] | NA | NA | 1079 | 301 (27.9) | NA | NA |

| AD | 659 | 387 (58.7) | NA | NA | 73.8 (4.9) [100] | NA | 659 | 442 (67.1) | NA | NA | ||

| MAYO2 | 122 | CN | 62 | 28 (45.2) | 83.0 (7.7) [100] | NA | NA | NA | 19 | 2 (10.5) | 43 | 5 (11.6) |

| AD | 60 | 39 (65.0) | 83.9 (5.5) [100] | NA | NA | NA | 60 | 33 (55.0) | NA | NA | ||

| MIRAGE | 481 | CN | 211 | 116 (55.0) | NA | 71.6 (7.4) [100] | NA | NA | 184 | 74 (40.2) | 27 | 9 (33.3) |

| AD | 270 | 168 (62.2) | NA | NA | 73.4 (6.1) [1.90] | 70.6 (6.6) [98.1] | 252 | 163 (64.7) | 18 | 8 (44.4) | ||

| OHSU | 316 | CN | 226 | 120 (53.1) | 85.6 (7.1) [100] | NA | NA | NA | 42 | 16 (38.1) | 184 | 34 (18.5) |

| AD | 90 | 58 (64.4) | NA | NA | 88.5 (9.5) [4.4] | 86.8 (7.2) [95.6] | 16 | 9 (56.3) | 74 | 26 (35.1) | ||

| ROSMAP | 1379 | CN | 821 | 579 (70.5) | 87.2 (6.8) [56.4] | 84.7 (6.9) [43.6] | NA | NA | 171 | 40 (23.4) | 650 | 104 (16.0) |

| AD | 558 | 411 (73.7) | 88.2 (2.6) [1.1] | NA | 83.8 (6.6) [98.9] | NA | 163 | 88 (54.0) | 395 | 131 (33.2) | ||

| TGEN2 | 946 | CN | 334 | 163 (48.8) | 80.0 (8.7) [100] | NA | NA | NA | 182 | 44 (24.2) | 152 | 28 (18.4) |

| AD | 612 | 410 (67.0) | 83.2 (6.6) [85.1] | NA | NA | 74.3 (7.1) [14.9] | 526 | 359 (68.3) | 86 | 48 (55.8) | ||

| UPITT | 1664 | CN | 682 | 436 (63.9) | NA | 75.6 (6.2) [100] | NA | NA | 546 | 117 (21.4) | 136 | 17 (12.5) |

| AD | 982 | 628 (64.0) | NA | NA | 76.7 (7.8) [11.7] | 72.6 (6.4) [88.3] | 844 | 523 (62.0) | 138 | 56 (40.6) | ||

| UM/VU/MSSM | 1198 | CN | 642 | 410 (63.9) | 76.8 (10.7) [10.0] | 73.2 (6.9) [90.0] | NA | NA | 531 | 135 (25.4) | 111 | 19 (17.1) |

| AD | 556 | 358 (64.4) | 83.8 (9.0) [6.1] | NA | 81.3 (10.4) [2.9] | 72.6 (7.3) [91.0] | 453 | 310 (68.4) | 103 | 49 (47.6) | ||

| WASHU | 316 | CN | 127 | 81 (63.8) | NA | 76.4 (8.5) [100] | NA | NA | 92 | 31 (33.7) | 35 | 4 (11.4) |

| AD | 189 | 108 (57.1) | NA | NA | NA | 74.7 (7.5) [100] | 146 | 91 (62.3) | 43 | 17 (39.5) | ||

| Total | 20 928 | CN | 10 237 | 6129 (59.9) | 84.5 (7.6) [25.4] | 76.4 (7.6) [74.6] | NA | NA | 6319 | 1772 (28.0) | 3918 | 741 (18.9) |

| AD | 10 691 | 6377 (59.6) | 83.3 (6.6) [6.0] | NA | 78.0 (7.6) [19.4] | 73.5 (7.5) [74.6] | 8554 | 5925 (69.3) | 2137 | 860 (40.2) | ||

Abbreviations: ACT, Adult Changes in Thought; ADC1-7, Alzheimer’s Disease Center data sets 1 through 7; ADDNEURO, European Collaboration for the Discovery of Novel Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease; ADNI, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; ADOD, ADNI Department of Defense; GenADA, Multi-Site Collaborative Study for Genotype-Phenotype Associations in Alzheimers Disease; NA, not applicable; NACC, National Alzheimer Coordinating Center; NIAGADS, National Institute on Aging and Genetics of Alzheimer’s Disease Data Storage Site; NIA-LOAD, National Institute on Aging Genetics Initiative for Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease; MAYO, Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Studies; MAYO2, Mayo RNaseq Study; MIRAGE, Multi-institutional Research on Alzheimer Genetics Epidemiology; OHSU, Oregon Health and Science University study; ROSMAP, Rush University Religious Orders Study/Memory and Aging Project; TGEN2, Translational Genomics Research Institute Series 2; UM/VU/MSSM, University of Miami/Vanderbilt University/Mt. Sinai School of Medicine Studies; UPITT, University of Pittsburgh Study; WASHU, Washington University Study.

Cohort data were available through NIAGADS, the NACC, AMP-AD Knowledge Portal, the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes, Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center at Rush University, and the Image & Data Archive powered by Laboratory of Neuro Imaging. Cohorts included the ACT, ADC1-7 (for which phenotype data are managed by the NACC), ADDNEURO, ADNI, ADOD, GenADA, NIA-LOAD, MAYO, MAYO2, MIRAGE, OHSU, ROSMAP, TGEN2, UM/VU/MSSM, UPITT, and WASHU.

Age at examination represents a mixture of age types; when multiple data were available for a participant, the youngest age was taken to approximate age at onset.

Age at onset refers to the first onset of cognitive symptoms as reported by the participant or informant and generally precedes clinical diagnosis.

The current study protocol was granted an exemption by the Stanford University institutional review board because the analyses were carried out on deidentified, off-the-shelf data. Further informed consent was therefore not required.

The ADNI cohort provided longitudinal measures of Aβ42 in CSF and Aβ aggregates in the brain from florbetapir PET24 (with sample and image processing described elsewhere39,40). For Aβ levels on PET scans, we investigated standardized uptake value ratios (referenced to the cerebellum) in a set of brain regions (composite regions of interest: parietal, temporal, frontal, and cingulate cortices) commonly affected by amyloid pathology.41,42 Associations with CSF Aβ42 were also evaluated in 3 cross-sectional cohorts that are available through National Institute on Aging Genetics of Alzheimer’s Disease Data Storage Site (NIAGADS). The cohorts’ genetic data and CSF measures were made publicly available on NIAGADS as part of the data sharing associated with an article by Cruchaga et al.43 Both the genetic data and CSF measures were processed in the Cruchaga et al article43 and made available under their processed format. All data were collected between September 2015 and September 2019.

The conversion and Aβ analyses used cohorts that are largely overlapping with the main case-control analysis. Thus, these should be considered supportive rather than fully independent analyses.

Genetic Data Quality Control and Processing

Genetic data underwent standard quality control (Plink version 1.9 [the Laboratory of Biological Modeling and the Purcell Lab]), imputation, and ancestry determination (SNPweights version 2.1 [T. H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard University]; eFigure 1 in the Supplement).44,45,46 To obtain the largest and most homogeneous sample, only non-Hispanic individuals of Northwestern European ancestry were selected. Principal component analysis of genotyped single-nucleotide variants was performed to obtain principal components that capture population substructure (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Participants’ relatedness was estimated from identity-by-descent analysis. If samples were from related individuals (identity-by-descent value ≥0.25; ie, second-degree relatives), only a single participant per relatedness cluster was used. Detailed descriptions of processing procedures and inclusion criteria are in the eMethods and eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Statistical Analyses

We evaluated the association of KL-VSHET+ status with (1) relative risk for AD, (2) absolute risk of converting from being cognitively normal to having MCI or AD, and (3) Aβ levels. All analyses were stratified by groups who carried APOE4 (APOE-24/34/44) and did not carry APOE4 (APOE-22/23/33). Associations with AD risk and Aβ were evaluated across 3 age ranges: 60 years and older, 60 to 80 years, and 80 years and older. The full sample of those 60 years and older represents the primary analyses. The groups aged 60 to 80 years and 80 years or older were used to test the secondary hypothesis that outcomes of KL-VS status differ across age. Associations with conversion risk were evaluated in the full sample of individuals 60 years and older, whereas age stratification was not needed in these time-to-event analyses. We also evaluated the formal interaction of APOE4 with KL-VSHET+ status in analyses that additionally included APOE4 and APOE4 × KL-VSHET interactions as model covariates. Outcomes were evaluated per cohort and combined using inverse-variance–weighted meta-analysis. In all models, we adjusted the outcome measure for sex and the first 3 genetic principal components. For associations with AD risk and Aβ, we also adjusted for age, even within age-stratified groups, to account for remaining age-associated outcomes. Associations were considered significant at a threshold P value of less than .05 (2-tailed).

A schematic overview of all analyses is provided in eFigure 3 in the Supplement. The association between KL-VSHET+ status and AD risk was evaluated using logistic regression analysis under a case-control design. When multiple age data were available, we prioritized age at onset (AAO) above age at examination, which was itself prioritized above age at death in affected individuals, and we prioritized age at death above age at last examination in control participants (Table 1). This priority ranking is consistent with prior AD studies34,38 and reflects the reasoning that AAO best marks the advent of pathological changes, while age at death in control participants marks the total time spent without cognitive impairment. Association between KL-VSHET+ status and absolute risk of conversion to MCI or AD, accounting for death as a competing risk, was evaluated using competing risk regression.47,48 In competing risk regression, we also adjusted for years of education, which was available for most participants in cohorts with conversion data. Participants were required to be cognitively normal at baseline and have at least 3 years of follow-up.49,50,51 Conversions were defined as the first clinical diagnosis of MCI or AD, while participants who were cognitively normal and did not convert or die were censored. Association testing with Aβ levels was restricted to control participants, as in prior studies.21,22 Associations between KL-VSHET+ status and Aβ measures in the ADNI study were evaluated by linear mixed-effects analysis to take into account the correlation between multiple measurements within each participant, additionally adjusting for diagnosis and participant as a random effect. The diagnosis term dealt with reversions from having MCI to being cognitively normal. Associations with Aβ CSF in the Cruchaga et al43 sample were evaluated by means of multiple linear regression, additionally adjusting for cohort (eMethods in the Supplement).

To evaluate and quantify potential cohort bias, case-control and conversion risk analyses were repeated using mega-analyses that included the cohort as a covariate. To evaluate potential bias attributable to the heterogeneity in age information across different cohorts (Table 1), case-control analyses were repeated using only cases that had AAO data available (n = 7994). To increase the reliability of age at diagnosis, conversion risk analyses were repeated requiring 4 and 5 years of minimal follow-up.49,50,51 In addition, we performed regression analyses to validate whether the association of APOE4 with risk for AD differs across age groups (60-80 years vs ≥80 years) and if APOE4 status affects AAO. All analyses were performed in R version 3.6.0 (nlme, metaphor, and cmprsk packages; R Foundation for Statistical Computing) between April 2019 and December 2019. Additional details for model/inclusion criteria are in the eMethods in the Supplement.

Results

KL-VS Heterozygosity and AD Risk per APOE4 Status

We evaluated the association of KL-VSHET+ status with AD risk by meta-analyzing across 22 AD cohorts (Table 1). We investigated 3 different age ranges, stratified by APOE4 status (Table 2). While KL-VSHET+ status is associated with decreased risk for AD in participants who carry APOE4 across the entire age range of those 60 years and older (odds ratio [OR], 0.75 [95% CI, 0.67-0.84]; P = 7.4 × 10−7), the outcome was driven mainly by the group aged 60 to 80 years (OR, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.61-0.79]; P = 3.6 × 10−8), with no significant association observed in the group 80 years and older (OR, 0.99 [95% CI, 0.77-1.27]; P = .94). There was no association found in any APOE4-negative group. The interaction between KL-VSHET+ status and APOE4 status for AD risk in the group aged 60 to 80 years was significant and protective (OR, 0.76 [95% CI, 0.66-0.89]; P = 3.9 × 10−4). Forest plots in eFigure 4 in the Supplement show high cohort homogeneity of KL-VSHET+ status association patterns in individuals who carry APOE4.

Table 2. Association of Klotho-VS Heterozygosity (KL-VSHET+) Status With Alzheimer Disease Status in Age and Apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4) Strataa.

| Group | Association between KL-VSHET+ and AD risk by APOE4 status | Interaction between KL-VSHET+ and AD risk by APOE4 status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control participants with KL-VSHET+ status, No./total No. (%) | Participants with AD with KL-VSHET+ status, No./total No. (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Control participants with KL-VSHET+ status, No./total No. (%) | Participants with AD with KL-VSHET+ status, No./total No. (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| 60-80 y | ||||||||

| APOE4+ | 528/1737 (30.4) | 1475/5883 (25.1) | 0.69 (0.61-0.79) | 3.6 × 10−8 | 1694/6189 (27.3) | 2137/8478 (25.2) | 0.73 (0.61-0.87) | 5.1 × 10−4 |

| APOE4− | 1166/4452 (26.2) | 662/2595 (25.5) | 0.98 (0.87-1.11) | .79 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| ≥80 y | ||||||||

| APOE4+ | 187/713 (26.2) | 218/826 (26.4) | 0.99 (0.77-1.27) | .94 | 972/3772 (25.9) | 552/2053 (26.9) | 0.92 (0.69-1.24) | .61 |

| APOE4− | 796/3090 (25.8) | 339/1253 (27.1) | 1.09 (0.93-1.28) | .28 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Full sample | ||||||||

| APOE4+ | 724/2488 (29.1) | 1707/6752 (25.3) | 0.75 (0.67-0.84) | 7.4 × 10−7 | 2704/10 103 (26.8) | 2718/10 631 (25.5) | 0.76 (0.66-0.89) | 3.9 × 10−4 |

| APOE4− | 1997/7670 (26.0) | 1015/3906 (26.0) | 1.01 (0.91-1.11) | .91 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer disease; HET+, heterozygous; NA, not applicable.

This Table shows the results of meta-analyses including cohorts with a minimal sample size of 50 that had both affected individuals and control participants.

In sensitivity analyses, results were highly consistent when cohorts were combined through mega-analysis (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Additionally, given that 25.4% of cases did not have AAO data provided (Table 1), we repeated analyses using only affected individuals with AAO data and all control participants (eTables 4 and 5 in the Supplement). Despite smaller sample sizes, the protective association of KL-VSHET+ status with AD in individuals carrying APOE4 was even more pronounced and remained strongest in the group of individuals who carried APOE4 and were between 60 and 80 years (meta-analysis; OR, 0.64 [95% CI, 0.55-0.74]; P = 4.0 × 10−9). In addition, we confirmed that, as expected, the association between APOE4 positivity and AD risk was stronger in those aged 60 to 80 years (OR, 5.79 [95% CI, 5.38-6.23]) compared with those 80 years or older (OR, 2.97 [95% CI, 2.63-3.35]; P < 2.2 × 10−16). Participants who carried APOE4 also had reduced AAO (mean [SD] age, 72.0 [6.7] years) compared with participants who did not carry APOE4 (mean [SD] age, 76.1 [8.1] years; P < 2.2 × 10−16).

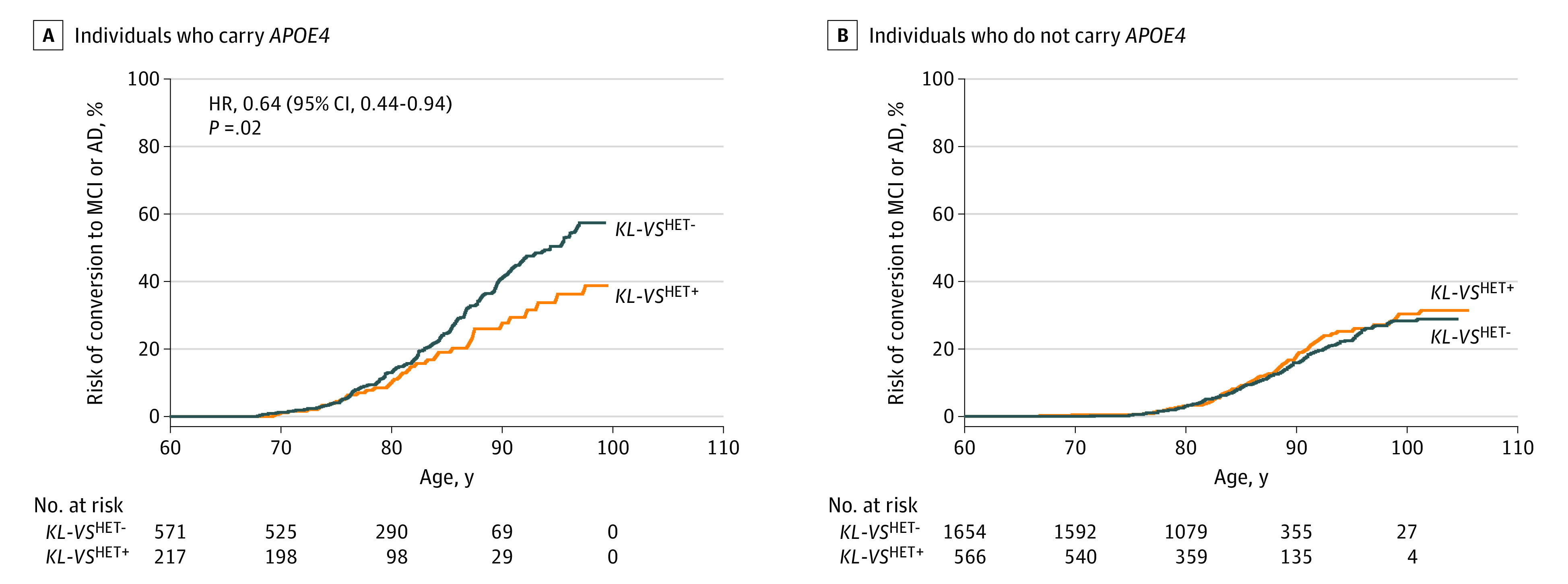

KL-VSHET+ Status and Risk of Conversion to MCI or AD in Individuals Stratified by APOE4 Status

We then assessed the association of KL-VSHET+ status with risk for conversion to MCI or AD. Meta-analysis across the 3 investigated cohorts (eTable 6 in the Supplement) showed a significant protective association of KL-VSHET+ status with conversion risk in those who carry APOE4 (hazard ratio [HR], 0.64 [95% CI, 0.44-0.94]; P = .02) but not in participants who did not carry APOE4 (HR, 1.06 [95% CI, 0.81-1.37]; P = .69; eTable 7 in the Supplement). The interaction between KL-VSHET+ status and APOE4 status was significant and protective (HR, 0.62 [95% CI, 0.39-1.00]; P = .048). Figure 1 shows the cumulative conversion risk across the age span, where the protective association of KL-VSHET+ status in the group with APOE4 begins around 77 years of age. Forest plots in eFigure 5 in the Supplement and cumulative risk plots in eFigure 6 in the Supplement show that these association and interaction patterns are consistent across all 3 cohorts. In sensitivity analyses, these findings remained consistent when evaluated through mega-analysis and after requiring minimum follow-up times of 4 or 5 years (eTable 8 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Risk of Conversion to Mild Cognitive Impairment or Alzheimer disease by Klotho-VS Heterozygosity Status, Stratified by APOE4 Status.

A, Individuals with apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4). The outcome of KL-VSHET+ status, as determined from competing risk regression analysis meta-analyzed across 3 independent cohorts, is significant in individuals who carry APOE4 (hazard ratio, 0.64 [95% CI, 0.4-0.94]; P = .02). B, Individuals without APOE4 (hazard ratio, 1.06 [95% CI, 0.81-1.37]; P = .69). AD indicates Alzheimer disease; HET+, heterozygosity; HET-, nonheterozygosity; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

We additionally evaluated the association of KL-VSHET+ status with conversion from being cognitively normal or having MCI to having AD (eTables 9 and 10 and eFigure 7 in the Supplement). The KL-VSHET+ status reduced conversion risk in the group carrying APOE4 (HR, 0.81 [95% CI, 0.66-1.00]; P = .047) but not in the group without APOE4 (HR, 1.12 [95% CI, 0.78-1.61]; P = .99). These outcomes were consistent for a minimum of 4 years and 5 years of follow-up. The interaction of KL-VSHET+ status with APOE4 status was protective but significant only for patients with a minimum of 5 years of follow-up (HR, 0.68 [95% CI, 0.49-0.95]; P = .02; eTable 9 in the Supplement).

KL-VSHET+ Status and Aβ in Control Participants Aged 60 to 80 Years Stratified by APOE4 Status

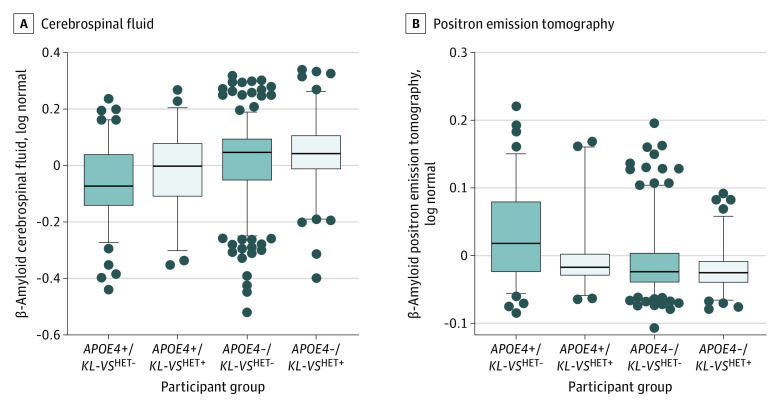

Similar to AD risk analyses, we evaluated whether there was an age-dependent association of KL-VSHET+ status with Aβ CSF levels. In the age range of 60 to 80 years, KL-VSHET+ status was significantly associated with increased Aβ CSF levels in control participants carrying APOE4 (β, 0.06 [95% CI, 0.01-0.10], P = .03) but not in control participants without APOE4 (β, 0.04 [95% CI, −0.02 to 0.09]; P = .22; Figure 2A). In the full age range (≥60 years), this association was not significant in control participants carrying APOE4 (β, 0.02 [95% CI, −0.03 to 0.06]; P = .50) or control participants without APOE4 (β, 0.02 [95% CI, −0.03 to 0.07]; P = .44; eFigure 8 in the Supplement). Forest plots in eFigure 9 in the Supplement show consistent associations for both cohorts in those aged 60 to 80 years who carried APOE4. Finally, we evaluated the association of KL-VSHET+ status with Aβ findings on PET in an AD-relevant brain composite region of interest. Findings were highly consistent with those for CSF levels; that is, KL-VSHET+ status significantly decreased Aβ on PET in the group who were positive for APOE4 and aged 60 to 80 years (β, −0.04 [95% CI, −0.07 to 0.00]; P = .04; Figure 2B) but not in those aged 60 to 80 years who did not carry APOE4 (β, 0.00 [95% CI, −0.02 to 0.01]; P = .69) or either of the other groups aged 60 years or older (eFigure 8 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Association of Klotho-VS Heterozygosity Status with β-Amyloid Levels in Control Participants 60 to 80 Years Old, Stratified by Apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4) Status.

A, Measured by cerebrospinal fluid samples. B, Measured by positron emission tomography imaging. Box plot error bars show the 95th-percentile range. Gray circles indicate values outside of the 95th percentile range. Meta-analyses between Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative and Cruchaga et al43 samples were significant in participants who carry APOE4 (leftmost pairs in each graph; cerebrospinal fluid, β, 0.06 [95% CI, 0.01-0.10]; P = .03; positron emission tomography, β, −0.04 [95% CI, −0.07 to −0.00]; P = .04). HET+ indicates heterozygosity; HET-, nonheterozygosity.

Additional Analyses

In addition to comparing participants with KL-VSHET+ status vs KL-VSHET− status, we contrasted individuals with KL-VSHET+ status vs those who did not carry KL-VS (eTables 11-15 in the Supplement). Results were highly consistent with the main analyses but had slightly reduced effect sizes. Because KL-VS homozygosity (KL-VSHOM) has been associated with negative outcomes on life span,2 brain-aging resilience,52 and cognition,4 we also evaluated individuals with KL-VSHOM status compared with those who did not carry KL-VS (eTables 16-19 and eFigure 10 in the Supplement). In individuals who carry APOE4, results were consistent, with KL-VSHOM status increasing risk, but only conversion risk from being cognitively normal or having MCI to having AD reached nominal significance. There were no significant results in participants who did not carry APOE4. Finally, given the biological ambiguity of individuals who carry APOE24 (both risk-increasing and decreasing alleles), we repeated analyses excluding these participants (eTables 20-24 in the Supplement). Again, results were highly consistent with the main analyses.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that KL-VSHET+ status was associated with reduced AD risk in individuals who carried APOE4, and this was so mostly between 60 and 80 years. In this age range, KL-VSHET+ status was also associated with lower Aβ burden in individuals who are cognitively normal and carry APOE4. Additionally, starting close to 80 years of age, control participants who carried APOE4 and had KL-VSHET+ status were at reduced risk of converting to MCI or AD.

To our knowledge, the current study is the largest to date to evaluate a heterozygous genetic association with AD risk. Specifically, we hypothesized that KL-VSHET+ status would reduce risk of AD in those who carried APOE4. Furthermore, given that the genetic risk for AD attributable to APOE4 is higher between 60 and 80 years of age,17,18,19 which was confirmed in our case-control analysis in which the OR for APOE4 was almost 2-fold higher in the group 60 to 80 years old (OR, 5.8) compared with those 80 years or older (OR, 3.0), we hypothesized that the protective association of KL-VSHET+ status in those with APOE4 would be strongest in the 60-year to 80-year age range. We showed that protective outcomes of KL-VSHET+ status on AD risk in those who carry APOE4 was highly significant across the entire age range older than 60 years but was considerably stronger between the ages of 60 and 80 years and was not detectable in the ages 80 years and older. This age-specific interaction of KL-VSHET+ status with APOE4 is also consistent with recent work that showed how genome-wide risk for AD differs between 60 and 80 years and those older than 80 years.43 The largest (to our knowledge) prior APOE4-stratified genome-wide association study of AD did not stratify by age and only evaluated additive genetic effects and so would not have picked up the KL-VSHET+ status outcome identified here.53

We then evaluated the association of KL-VSHET+ status with conversion risk. In individuals who carry APOE4, KL-VSHET+ status reduced risk of conversion from cognitively normal status to MCI or AD with a hazard ratio of approximately 0.65 and from cognitively normal status or MCI to AD with a hazard ratio of about 0.80. This suggests that the protective nature of KL-VSHET+ status is stronger in control participants and diminishes in affected individuals who have already developed MCI. Ascertainment differences across cohorts represent a source of bias, but findings were consistent for both mega-analyses and meta-analyses. Additionally, by restricting our analyses to participants with a minimal follow-up time of 3, 4, or 5 years, we could increase confidence in the age at diagnosis.49,50,51 For each model that required 5 or more years of minimal follow-up, we obtained significant results for KL-VSHET+ status in the APOE4-positive groups and interactions of KL-VSHET+ status with APOE4. Lastly, we could add years of education as a covariate in the conversion models, allowing us to account for MCI or AD risk mitigation attributable to possible differences in cognitive reserve.54

Notably, the difference in conversion risk between participants who had KL-VSHET+ status vs those with KL-VSHET− status who carried APOE4 became apparent around 80 years of age. There are no prior reports on MCI or AD conversion risk attributable to having KL-VSHET+ status to compare our findings with. However, Porter et al22 examined individuals who were cognitively normal with a mean age of 71 years and reported there was neither an association of KL-VSHET+ status with longitudinal measures of global cognition nor a modifying association with APOE4 status. Other studies that evaluated the association of KL-VSHET+ status with measures of cognition in control participants did not directly investigate interactions with APOE4 but did observe protective associations that were more pronounced closer to 80 years of age.3,5,55 Overall, our findings appear consistent with prior literature, but further studies need to evaluate the interaction of age, APOE4, and KL-VSHET+ status on cognition in control populations.

We observed significant protective interactions between APOE4 status and KL-VSHET+ status for both risk of AD and risk of conversion, whereas KL-VSHET+ status had no association with outcome in individuals who did not carry APOE4. This suggests that KL-VS interacts with aspects of AD pathology that are more pronounced in those who carry APOE4, such as Aβ accumulation during the presymptomatic phases of the disease. Our analyses of Aβ CSF and PET in control participants with APOE4 between ages 60 and 80 years indeed confirmed reduced Aβ burden attributable to KL-VSHET+ status. Erickson et al21 reported similar results, in that those with KL-VSHET+ status did not display the commonly expected difference in Aβ burden (in CSF levels and on PET scanning) between control participants with APOE4 vs without APOE4, but participants who were KL-VSHET− did. All brain areas that we investigated in the composite region of interest also displayed consistent results in the study by Erickson et al. While Porter et al22 reported there was no association of KL-VSHET+ status with cognition, they did not directly evaluate associations with Aβ. In that study,22 participants were classified as having low or high amounts of Aβ based on brain Aβ levels on PET scans. When we considered ratios of participants with low and high Aβ amounts, as reported in Table 2 of their article,22 we could derive risk estimates associated with high levels of Aβ for those with KL-VSHET+ status and APOE4 (OR, 0.59) and without APOE4 (OR, 0.82). These are similar to our finding that KL-VSHET+ status reduced Aβ on PET in those who carry APOE4. Overall, our findings associating KL-VSHET+ status with Aβ appear consistent with results in 2 prior, independent studies.

Reduced Aβ burden attributable to KL-VSHET+ status in control participants with APOE4 between ages 60 and 80 years may provide an explanation for the age shift between our case-control and conversion findings. The AD risk attributable to KL-VSHET+ status in those who carry APOE4 was lower between ages 60 and 80 years, where the age for cases mainly represented AAO (mean age, 72 years). Protective associations of KL-VSHET+ status with conversion risk became apparent around 77 years of age, roughly indicating a 5-year shift between the onset of symptoms and a formal diagnosis or conversion. Abnormal Aβ levels in control participants can precede conversion by 5 to 10 years,10 suggesting that KL-VSHET+ status may delay conversion by reducing Aβ levels. Currently, there is an increasing need to identify risk factors that improve prognostication of AD conversion risk.56 These risk factors can be used to stratify patients into high-risk groups who can be recruited into clinical prevention trials to increase their statistical power and efficiency. The APOE4 allele is a major genetic risk factor used for AD trial enrichment.57 Our results suggest that for prevention trials, it will help to further select control participants who have KL-VSHET− status and APOE4 (70% of the sample), who appear more likely to convert to AD. On an interesting, related matter, KL-VSHET+ status has been associated with increased serum levels of KL,3,52 while KL-VSHOM has conversely been associated with decreased serum levels of KL.52 Both studies further found direct correlations between systemic KL levels and cognitive performance in mice3 and brain aging resilience in humans.52 Additionally, CSF levels of KL were shown to be lower in individuals with AD vs age-matched participants who were cognitively normal.58 Combined with our findings that KL-VSHET+ status is consistently associated with reductions (and KL-VSHOM with increases) in AD conversion risk, this suggests that systemic KL levels may serve as a promising biomarker to help identify those who are positive for APOE4 and at higher risk for developing AD.

Currently, there is no known mechanism by which KL-VS interacts with APOE4 to modulate Aβ levels. Interestingly, KL expression is regulated by amyloid precursor protein (APP).59 Furthermore, 3 enzymes linked to APP cleavage (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing proteins 10 and 17 [ADAM10 and ADAM17] and β-secretase 1 [BACE1]) also cleave KL in the cell membrane leading to shedding of KL’s extracellular domain.60,61,62 In AD mouse models, therapies aimed at increasing KL expression or KL cleavage were shown to reduce Aβ burden through autophagy-mediated clearance and confer neuroprotection through increased expression of ADAM10.63,64 Overall, this raises the intriguing possibility of an interaction between APOE4, KL-VS, and the molecular APP processing machinery that produces Aβ. Other studies, in animal models and humans, indicate that KL-VSHET+ status confers resilience to brain-aging and cognitive aging,4,52,65,66 which may also contribute to protective associations against AD. Although lacking direct validation, our findings may also suggest that individuals with KL-VSHET+ status are biologically younger than those who have KL-VSHET− status. Indeed, previous studies reported both a slowed epigenetic age for individuals with KL-VS heterozygosity67 and a direct correlation between telomerase activity and KL expression.68 Notably, KL-VSHET+ status showed an age-specific association with AD here, which is in line with prior findings on life span trajectories.2,69 Future studies will need to explore these promising research avenues.

Limitations

One limitation for our analyses is the variability in age and diagnosis ascertainment across cohorts. However, we repeated all tests using both meta-analyses and mega-analyses. We also performed sensitivity analyses, including only individuals with AD who had AAO data available. Our findings were highly consistent across all models and displayed little to no heterogeneity, making it unlikely that the results were affected by cohort bias. The null findings in the groups 80 years and older may, however, also be attributable to limited sample sizes in this age stratum.

Conclusions

Overall, our findings suggest that KL-VSHET+, possibly by increasing systemic KL levels, is associated with a protective outcome against AD that manifests in participants who carry APOE4 and are cognitively normal between the ages of 60 and 80 years. Our work paves the way for biological validation studies to elucidate the molecular pathways by which KL-VS and APOE interact. Information on KL-VS status should also prove useful in further refinement of genetic risk profiles for both clinical trial enrichment and personalized genetic counseling.

eMethods. Phenotype Ascertainment, Genetic Data Quality Control and Processing, and Statistical Analyses – Additional Model Criteria.

eFigure 1. Admixture plots for A) the five major super populations and B) three major sub-European populations across all 22 case-control cohorts.

eFigure 2. First three principal components of the genetic population structure in Northwestern European subjects across all 22 case-control cohorts.

eFigure 3. Schematic overview of data sets and performed analyses.

eFigure 4. Forest plots for the association of KL-VSHET+ with Alzheimer disease case-control status in 60-80 year old subjects.

eFigure 5. Forest plots for the association of KL-VSHET+ with risk of conversion to mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease in subjects with a minimum of three years follow-up time.

eFigure 6. Cohort-specific risk of conversion to mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease by KL-VS heterozygosity status in A) APOE4+ and B) APOE4- subjects.

eFigure 7. Risk of conversion to Alzheimer disease by KL-VS heterozygosity status in A) APOE4+ and B) APOE4- subjects.

eFigure 8. Association of KL-VS heterozygosity status with amyloid beta levels in 60+ years old controls stratified by APOE4 status, as measured from A) CSF samples and B) PET imaging.

eFigure 9. Forest plots for the association of KL-VSHET+ with amyloid beta CSF in APOE4+ controls of ages A) 60-80 and B) 60+ years.

eFigure 10. Association of KL-VSHOM, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with amyloid beta levels as measured from CSF samples, in A) 60-80 and B) 60+ years old controls, stratified by APOE4 status.

eTable 1. SNP microarray platforms per cohort.

eTable 2. Case-control sample sizes per cohort after sequential quality control and filtering steps (detailed in the titles above each column).

eTable 3. Association of KL-VSHET+ with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, determined by MEGA-analysis.

eTable 4. Association of KL-VSHET+ with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, determined by META-analysis and using only age-at-onset data for cases.

eTable 5. Association of KL-VSHET+ with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, determined by MEGA-analysis and using only age-at-onset data for cases.

eTable 6. Sample sizes per conversion risk cohort after sequential quality control and filtering steps.

eTable 7. Association of KL-VSHET+ with risk of conversion to mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 8. Association of KL-VSHET+ with risk of conversion to mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by MEGA-analysis.

eTable 9. Association of KL-VSHET+ with risk of conversion to Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 10. Association of KL-VSHET+ with risk of conversion to Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by MEGA-analysis.

eTable 11. Association of KL-VSHET+, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 12. Association of KL-VSHET+, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, determined by META-analysis and using only age-at-onset data for cases.

eTable 13. Association of KL-VSHET+, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with risk of conversion to mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 14. Association of KL-VSHET+, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with risk of conversion to Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 15. Association of KL-VSHET+, in contrast to KL-VSHET- or KL-VSNC, with Aβ levels in cognitively normal subjects, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 16. Association of KL-VSHOM, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, determined by MEGA-analysis.

eTable 17. Association of KL-VSHOM, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, determined by MEGA-analysis and using only age-at-onset data for cases.

eTable 18. Association of KL-VSHOM, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with risk of conversion to mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by MEGA-analysis.

eTable 19. Association of KL-VSHOM, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with risk of conversion to Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by MEGA-analysis.

eTable 20. Association of KL-VSHET+ with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, but excluding APOE24 carriers, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 21. Association of KL-VSHET+ with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, but excluding APOE24 carriers, determined by META-analysis and using only age-at-onset data for cases.

eTable 22. Association of KL-VSHET+ with risk of conversion to mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status but excluding APOE24 carriers, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 23. Association of KL-VSHET+ with risk of conversion to Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status but excluding APOE24 carriers, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 24. Association of KL-VSHET+ with Aβ levels in cognitively normal subjects, stratified by APOE4 status but excluding APOE24 carriers, determined by META-analysis.

eReferences.

References

- 1.Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, et al. Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho. Science. 2005;309(5742):1829-1833. doi: 10.1126/science.1112766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arking DE, Krebsova A, Macek M Sr, et al. Association of human aging with a functional variant of klotho. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(2):856-861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022484299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubal DB, Yokoyama JS, Zhu L, et al. Life extension factor klotho enhances cognition. Cell Rep. 2014;7(4):1065-1076. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yokoyama JS, Sturm VE, Bonham LW, et al. Variation in longevity gene KLOTHO is associated with greater cortical volumes. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2015;2(3):215-230. doi: 10.1002/acn3.161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Vries CF, Staff RT, Harris SE, et al. Klotho, APOEε4, cognitive ability, brain size, atrophy, and survival: a study in the Aberdeen Birth Cohort of 1936. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;55:91-98. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belloy ME, Napolioni V, Greicius MD. A quarter century of APOE and Alzheimer’s disease: progress to date and the path forward. Neuron. 2019;101(5):820-838. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.01.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, et al. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42 in humans. Ann Neurol. 2006;59(3):512-519. doi: 10.1002/ana.20730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris JC, Roe CM, Xiong C, et al. APOE predicts amyloid-β but not tau Alzheimer’s pathology in cognitively normal aging. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(1):122-131. doi: 10.1002/ana.21843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256(5054):184-185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jack CR Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):207-216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burnham SC, Bourgeat P, Doré V, et al. ; AIBL Research Group . Clinical and cognitive trajectories in cognitively healthy elderly individuals with suspected non-Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology (SNAP) or Alzheimer’s disease pathology: a longitudinal study. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(10):1044-1053. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30125-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vos SJB, Xiong C, Visser PJ, et al. Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and its outcome: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(10):957-965. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70194-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toledo JB, Zetterberg H, van Harten AC, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarker in cognitively normal subjects. Brain. 2015;138(pt 9):2701-2715. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutphen CL, Jasielec MS, Shah AR, et al. Longitudinal cerebrospinal fluid biomarker changes in preclinical Alzheimer disease during middle age. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(9):1029-1042. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.1285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ossenkoppele R, Jansen WJ, Rabinovici GD, et al. ; Amyloid PET Study Group . Prevalence of amyloid PET positivity in dementia syndromes: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(19):1939-1949. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim YY, Kalinowski P, Pietrzak RH, et al. Association of β-amyloid and apolipoprotein E ε4 with memory decline in preclinical Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(4):488-494. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.4325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neu SC, Pa J, Kukull W, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype and sex risk factors for alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(10):1178-1189. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, et al. ; APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium . Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1997;278(16):1349-1356. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550160069041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bickeböller H, Campion D, Brice A, et al. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: genotype-specific risks by age and sex. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60(2):439-446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karran E, Mercken M, De Strooper B. The amyloid cascade hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease: an appraisal for the development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(9):698-712. doi: 10.1038/nrd3505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erickson CM, Schultz SA, Oh JM, et al. KLOTHO heterozygosity attenuates APOE4-related amyloid burden in preclinical AD. Neurology. 2019;92(16):e1878-e1889. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porter T, Burnham SC, Milicic L, et al. Klotho allele status is not associated with Aβ and APOE ε4-related cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;76:162-165. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo MT, Kauppi K, Fan CC, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Consortium . Identification of genetic heterogeneity of Alzheimer’s disease across age. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;84:243.e1-243.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiner MW, Aisen PS, Jack CR Jr, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . The Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative: progress report and future plans. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(3):202-11.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9(6):646-663. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JH, Cheng R, Graff-Radford N, Foroud T, Mayeux R; National Institute on Aging Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Family Study Group . Analyses of the National Institute on Aging Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Family Study: implication of additional loci. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(11):1518-1526. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamboh MI, Minster RL, Demirci FY, et al. Association of CLU and PICALM variants with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(3):518-521. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiner MW, Veitch DP, Hayes J, et al. ; Department of Defense Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Effects of traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder on Alzheimer’s disease in veterans, using the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(3)(suppl):S226-S235. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li H, Wetten S, Li L, et al. Candidate single-nucleotide polymorphisms from a genomewide association study of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(1):45-53. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lovestone S, Francis P, Kloszewska I, et al. AddNeuroMed Consortium. AddNeuroMed—the European collaboration for the discovery of novel biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1180:36-46. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen M, Carrasquillo MM, Funk C, et al. Human whole genome genotype and transcriptome data for Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. Sci Data. 2016;3:160089. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carrasquillo MM, Zou F, Pankratz VS, et al. Genetic variation in PCDH11X is associated with susceptibility to late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41(2):192-198. doi: 10.1038/ng.305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Besser L, Kukull W, Knopman DS, et al. ; Neuropsychology Work Group . Directors, and Clinical Core leaders of the National Institute on Aging-funded US Alzheimer’s Disease Centers. Version 3 of the national Alzheimer’s coordinating center’s uniform data set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2018;32(4):351-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naj AC, Jun G, Beecham GW, et al. Common variants at MS4A4/MS4A6E, CD2AP, CD33 and EPHA1 are associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43(5):436-441. doi: 10.1038/ng.801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beecham GW, Martin ER, Li YJ, et al. Genome-wide association study implicates a chromosome 12 risk locus for late-onset Alzheimer disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84(1):35-43. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kukull WA, Higdon R, Bowen JD, et al. Dementia and Alzheimer disease incidence: a prospective cohort study. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(11):1737-1746. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.11.1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Green RC, Cupples LA, Go R, et al. ; MIRAGE Study Group . Risk of dementia among white and African American relatives of patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2002;287(3):329-336. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kunkle BW, Grenier-Boley B, Sims R, et al. ; Alzheimer Disease Genetics Consortium (ADGC) . European Alzheimer’s Disease Initiative (EADI); Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology Consortium (CHARGE); Genetic and Environmental Risk in AD/Defining Genetic, Polygenic and Environmental Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease Consortium (GERAD/PERADES). Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Aβ, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat Genet. 2019;51(3):414-430. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0358-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker signature in Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative subjects. Ann Neurol. 2009;65(4):403-413. doi: 10.1002/ana.21610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jagust WJ, Bandy D, Chen K, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative positron emission tomography core. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(3):221-229. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landau SM, Harvey D, Madison CM, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Associations between cognitive, functional, and FDG-PET measures of decline in AD and MCI. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(7):1207-1218. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landau SM, Mintun MA, Joshi AD, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Amyloid deposition, hypometabolism, and longitudinal cognitive decline. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(4):578-586. doi: 10.1002/ana.23650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cruchaga C, Kauwe JSK, Harari O, et al. GERAD Consortium; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI); Alzheimer Disease Genetic Consortium (ADGC). GWAS of cerebrospinal fluid tau levels identifies risk variants for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2013;78(2):256-268. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, et al. 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526(7571):68-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen CY, Pollack S, Hunter DJ, Hirschhorn JN, Kraft P, Price AL. Improved ancestry inference using weights from external reference panels. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(11):1399-1406. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Das S, Forer L, Schönherr S, et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat Genet. 2016;48(10):1284-1287. doi: 10.1038/ng.3656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496-509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scrucca L, Santucci A, Aversa F. Regression modeling of competing risk using R: an in depth guide for clinicians. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45(9):1388-1395. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vos SJB, Verhey F, Frölich L, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Prevalence and prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease at the mild cognitive impairment stage. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 5):1327-1338. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Belleville S, Fouquet C, Hudon C, Zomahoun HTV, Croteau J. Consortium for the Early Identification of Alzheimer’s disease-Quebec. Neuropsychological measures that predict progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s type dementia in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev. 2017;27(4):328-353. doi: 10.1007/s11065-017-9361-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gauthier S, Reisberg B, Zaudig M, et al. International Psychogeriatric Association Expert Conference on mild cognitive impairment. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet. 2006;367(9518):1262-1270. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68542-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yokoyama JS, Marx G, Brown JA, et al. Systemic klotho is associated with KLOTHO variation and predicts intrinsic cortical connectivity in healthy human aging. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017;11(2):391-400. doi: 10.1007/s11682-016-9598-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jun G, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Vronskaya M, et al. IGAP Consortium. A novel Alzheimer disease locus located near the gene encoding tau protein. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(1):108-117. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(11):1006-1012. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70191-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deary IJ, Harris SE, Fox HC, et al. KLOTHO genotype and cognitive ability in childhood and old age in the same individuals. Neurosci Lett. 2005;378(1):22-27. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Maurik IS, Vos SJ, Bos I, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Biomarker-based prognosis for people with mild cognitive impairment (ABIDE): a modelling study. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(11):1034-1044. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30283-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ballard C, Atri A, Boneva N, et al. Enrichment factors for clinical trials in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2019;5:164-174. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2019.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Semba RD, Moghekar AR, Hu J, et al. Klotho in the cerebrospinal fluid of adults with and without Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2014;558:37-40. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.10.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li H, Wang B, Wang Z, et al. Soluble amyloid precursor protein (APP) regulates transthyretin and Klotho gene expression without rescuing the essential function of APP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(40):17362-17367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012568107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Brien RJ, Wong PC. Amyloid precursor protein processing and Alzheimer’s disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:185-204. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen C-D, Podvin S, Gillespie E, Leeman SE, Abraham CR. Insulin stimulates the cleavage and release of the extracellular domain of Klotho by ADAM10 and ADAM17. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(50):19796-19801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709805104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bloch L, Sineshchekova O, Reichenbach D, et al. Klotho is a substrate for α-, β- and γ-secretase. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(19):3221-3224. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zeng CY, Yang TT, Zhou HJ, et al. Lentiviral vector-mediated overexpression of Klotho in the brain improves Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology and cognitive deficits in mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;78:18-28. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuang X, Zhou HJ, Thorne AH, Chen XN, Li LJ, Du JR. Neuroprotective effect of ligustilide through induction of α-secretase processing of both APP and Klotho in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:353. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dubal DB, Zhu L, Sanchez PE, et al. Life extension factor klotho prevents mortality and enhances cognition in hAPP transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2015;35(6):2358-2371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5791-12.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abraham CR, Mullen PC, Tucker-Zhou T, Chen CD, Zeldich E. Klotho is a neuroprotective and cognition-enhancing protein. Vitam Horm. 2016;101:215-238. doi: 10.1016/bs.vh.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wolf EJ, Morrison FG, Sullivan DR, et al. The goddess who spins the thread of life: Klotho, psychiatric stress, and accelerated aging. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;80:193-203. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ullah M, Sun Z. Klotho deficiency accelerates stem cells aging by impairing telomerase activity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(9):1396-1407. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Invidia L, Salvioli S, Altilia S, et al. The frequency of Klotho KL-VS polymorphism in a large Italian population, from young subjects to centenarians, suggests the presence of specific time windows for its effect. Biogerontology. 2010;11(1):67-73. doi: 10.1007/s10522-009-9229-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Phenotype Ascertainment, Genetic Data Quality Control and Processing, and Statistical Analyses – Additional Model Criteria.

eFigure 1. Admixture plots for A) the five major super populations and B) three major sub-European populations across all 22 case-control cohorts.

eFigure 2. First three principal components of the genetic population structure in Northwestern European subjects across all 22 case-control cohorts.

eFigure 3. Schematic overview of data sets and performed analyses.

eFigure 4. Forest plots for the association of KL-VSHET+ with Alzheimer disease case-control status in 60-80 year old subjects.

eFigure 5. Forest plots for the association of KL-VSHET+ with risk of conversion to mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease in subjects with a minimum of three years follow-up time.

eFigure 6. Cohort-specific risk of conversion to mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease by KL-VS heterozygosity status in A) APOE4+ and B) APOE4- subjects.

eFigure 7. Risk of conversion to Alzheimer disease by KL-VS heterozygosity status in A) APOE4+ and B) APOE4- subjects.

eFigure 8. Association of KL-VS heterozygosity status with amyloid beta levels in 60+ years old controls stratified by APOE4 status, as measured from A) CSF samples and B) PET imaging.

eFigure 9. Forest plots for the association of KL-VSHET+ with amyloid beta CSF in APOE4+ controls of ages A) 60-80 and B) 60+ years.

eFigure 10. Association of KL-VSHOM, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with amyloid beta levels as measured from CSF samples, in A) 60-80 and B) 60+ years old controls, stratified by APOE4 status.

eTable 1. SNP microarray platforms per cohort.

eTable 2. Case-control sample sizes per cohort after sequential quality control and filtering steps (detailed in the titles above each column).

eTable 3. Association of KL-VSHET+ with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, determined by MEGA-analysis.

eTable 4. Association of KL-VSHET+ with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, determined by META-analysis and using only age-at-onset data for cases.

eTable 5. Association of KL-VSHET+ with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, determined by MEGA-analysis and using only age-at-onset data for cases.

eTable 6. Sample sizes per conversion risk cohort after sequential quality control and filtering steps.

eTable 7. Association of KL-VSHET+ with risk of conversion to mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 8. Association of KL-VSHET+ with risk of conversion to mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by MEGA-analysis.

eTable 9. Association of KL-VSHET+ with risk of conversion to Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 10. Association of KL-VSHET+ with risk of conversion to Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by MEGA-analysis.

eTable 11. Association of KL-VSHET+, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 12. Association of KL-VSHET+, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, determined by META-analysis and using only age-at-onset data for cases.

eTable 13. Association of KL-VSHET+, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with risk of conversion to mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 14. Association of KL-VSHET+, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with risk of conversion to Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 15. Association of KL-VSHET+, in contrast to KL-VSHET- or KL-VSNC, with Aβ levels in cognitively normal subjects, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 16. Association of KL-VSHOM, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, determined by MEGA-analysis.

eTable 17. Association of KL-VSHOM, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, determined by MEGA-analysis and using only age-at-onset data for cases.

eTable 18. Association of KL-VSHOM, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with risk of conversion to mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by MEGA-analysis.

eTable 19. Association of KL-VSHOM, in contrast to KL-VSNC, with risk of conversion to Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status, determined by MEGA-analysis.

eTable 20. Association of KL-VSHET+ with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, but excluding APOE24 carriers, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 21. Association of KL-VSHET+ with Alzheimer disease case-control status in age- and APOE4-strata, but excluding APOE24 carriers, determined by META-analysis and using only age-at-onset data for cases.

eTable 22. Association of KL-VSHET+ with risk of conversion to mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status but excluding APOE24 carriers, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 23. Association of KL-VSHET+ with risk of conversion to Alzheimer disease, stratified by APOE4 status but excluding APOE24 carriers, determined by META-analysis.

eTable 24. Association of KL-VSHET+ with Aβ levels in cognitively normal subjects, stratified by APOE4 status but excluding APOE24 carriers, determined by META-analysis.

eReferences.