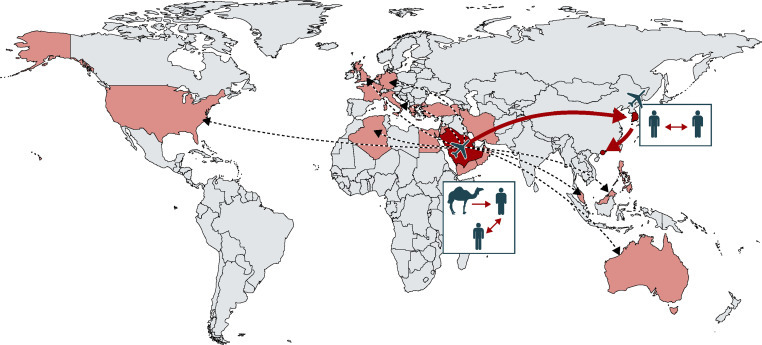

First reported in September, 2012, human infections with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) can result in severe respiratory disease, characterised by life-threatening pneumonia and renal failure.1 Countries with primary infections of MERS-CoV are located in the Middle East, but cases have been occasionally exported in other countries (figure ). Human-to-human infections of MERS-CoV are rare2 and confirmed cases are usually traced back to contact with camels, an intermediate host species for MERS-CoV.3

Figure.

Imported MERS-CoV human cases and affected countries

Countries affected by MERS-CoV are shown in red, including the recent cases in South Korea and China. Arrows show MERS-CoV importations. Red arrows show the recent importation of MERS-CoV in South Korea and China. Countries involved in the importation of MERS-CoV in South Korea and China are shown in dark red.

As of May 24, 2015, worldwide, a total of 1134 cases and 427 deaths (case fatality rate 37·7%) have been reported, according to WHO.4 There is no approved vaccine or treatment.

On May 11, 2015, a 68-year-old male in South Korea developed symptoms and sought medical care at a clinic between May 12–15, before admittance into hospital on May 15.4 The patient had been travelling between April 18–May 3 through Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar. He was asymptomatic upon return to South Korea on May 4, but tested positive for MERS-CoV on May 20, along with two additional cases: his 64-year-old wife, and a 76-year-old male who was a fellow patient.4 Concerns of further MERS-CoV spread were confirmed when a 71-year-old male fellow patient, the daughter of the 76-year-old case, and two medical staff developed symptoms and were diagnosed with MERS-CoV infection (appendix). As of May 29, 2015, South Korea has 12 laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS-CoV, and more than 120 additional contacts under surveillance.5

On May 28, a 44-year-old male traveller from South Korea to Huizhou, China was admitted into hospital. MERS-CoV infection was confirmed on May 29, marking the first laboratory-confirmed case in China (appendix), and the patient was immediately put in isolation. This patient was the son of the 76-year-old South Korean patient. He had visited his father in the hospital on May 16, developed symptoms on May 21,6 and travelled to Hong Kong by plane on May 26 before arriving by road into mainland China via Shenzhen.6 In response, the Chinese health authorities promptly placed 38 high-risk contacts under surveillance, but it is not known whether additional contacts exist and further MERS-CoV infections in China remains a possibility.

This series of events highlighted issues with the current surveillance system put in place to prevent the importation of infectious diseases. The diagnosis for MERS-CoV infection was made on May 20 for the 76-year-old patient. His 44-year-old son should have been monitored as a close contact of the laboratory-confirmed case, with provisional quarantine and testing upon development of symptoms and isolation upon a positive diagnosis. Such a high-risk case should not be travelling until after the incubation period, which is between 2–15 days for MERS-CoV.2 Non-compliance by the patient regarding travel advice likely contributed to this scenario.5

These events serve as a timely reminder that natural geographical barriers against pathogens can now be easily overcome through trade and travel, and marks the first MERS-CoV import case that did not come directly from the Middle East. These developments are worrisome given that Hong Kong airport is a major international transport hub, and thus any potential infections can travel worldwide in a short time.

After dealing with several pandemic threats over the past 15 years, notably severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in 2003, H1N1 influenza in 2009, and Ebola virus in 2014–15, authorities now have ample experience in outbreak response compared with past years. In addition to the need for increased vigilance from health authorities, compliance by the public is crucial for the effective implementation of outbreak responses. Everyone is responsible for upholding the principles of public health, and must play their part to minimise the chances of disease transmission across borders.

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Al-Tawfiq JA, Hinedi K, Ghandour J. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a case-control study of hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:160–165. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan JF, Lau SK, To KK, Cheng VC, Woo PC, Yuen KY. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: another zoonotic betacoronavirus causing SARS-like disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28:465–522. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00102-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azhar EI, El-Kafrawy SA, Farraj SA. Evidence for camel-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2499–2505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Global Alert and Response. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)—Republic of Korea. May 24, 2015. http://www.who.int/csr/don/24-may-2015-mers-korea/en/ (accessed May 30, 2015).

- 5.International Society for Infectious Diseases MERS-COV (50): South Korea, China, Saudi Arabia. http://www.promedmail.org/direct.php?id=3395374 (accessed May 31, 2015).

- 6.WHO Global Alert and Response (GAR). Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)—China. May 30, 2015. www.who.int/csr/don/30-may-2015-mers-china/en/ (accessed May 31, 2015).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.