Abstract

Background

Escalating awareness of the magnitude of the challenge posed by low levels of physical activity in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) highlights the need for interventions to increase physical activity participation. The widely‐accepted benefits of physical activity, coupled with the increasing availability of wearable monitoring devices to objectively measure participation, has led to a dramatic rise in the number and variety of studies that aimed to improve the physical activity of people with COPD. However, little was known about the relative efficacy of interventions tested so far.

Objectives

In people with COPD, which interventions are effective at improving objectively‐assessed physical activity?

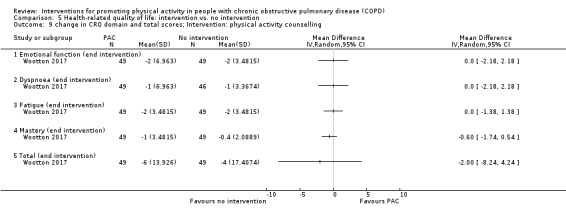

Search methods

We identified trials from the Cochrane Airways Trials Register Register, which contains records identified from bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, AMED, and PsycINFO. We also searched PEDro, ClinicalTrials.gov, the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform portal and the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (from inception to June 2019). We checked reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references, as well as respiratory journals and respiratory meeting abstracts, to identify relevant studies.

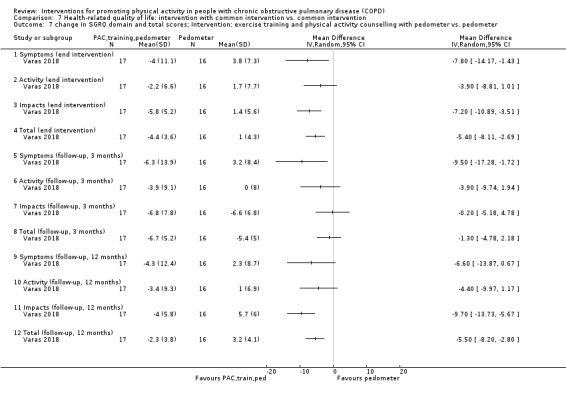

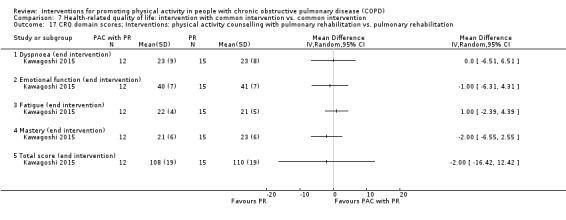

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials of interventions that used objective measures for the assessment of physical activity in people with COPD. Trials compared an intervention with no intervention or a sham/placebo intervention, an intervention in addition to another standard intervention common to both groups, or two different interventions.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methods recommended by Cochrane. Subgroup analyses were possible for supervised compared to unsupervised pulmonary rehabilitation programmes in clinically‐stable COPD for a range of physical activity outcomes. Secondary outcomes were health‐related quality of life, exercise capacity, adverse events and adherence. Insufficient data were available to perform prespecified subgroup analyses by duration of intervention or disease severity. We undertook sensitivity analyses by removing studies that were at high or unclear risk of bias for the domains of blinding and incomplete outcome data.

Main results

We included 76 studies with 8018 participants. Most studies were funded by government bodies, although some were sponsored by equipment or drug manufacturers. Only 38 studies had physical activity as a primary outcome. A diverse range of interventions have been assessed, primarily in single studies, but improvements have not been systematically demonstrated following any particular interventions. Where improvements were demonstrated, results were confined to single studies, or data for maintained improvement were not provided. Step count was the most frequently reported outcome, but it was commonly assessed using devices with documented inaccuracy for this variable.

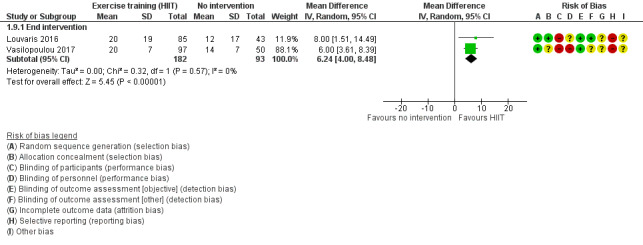

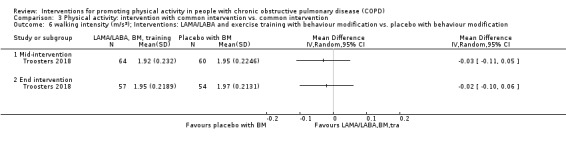

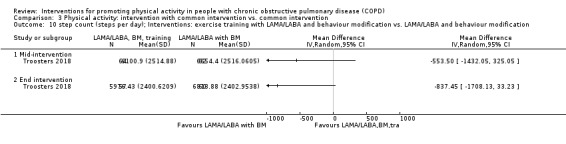

Compared to no intervention, the mean difference (MD) in time in moderate‐ to vigorous‐intensity physical activity (MVPA) following pulmonary rehabilitation was four minutes per day (95% confidence interval (CI) −2 to 9; 3 studies, 190 participants; low‐certainty evidence). An improvement was demonstrated following high‐intensity interval exercise training (6 minutes per day, 95% CI 4 to 8; 2 studies, 275 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). One study demonstrated an improvement following six months of physical activity counselling (MD 11 minutes per day, 95% CI 7 to 15; 1 study, 280 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence), but we found mixed results for the addition of physical activity counselling to pulmonary rehabilitation. There was an improvement following three to four weeks of pharmacological treatment with long‐acting muscarinic antagonist and long‐acting beta2‐agonist (LAMA/LABA) compared to placebo (MD 10 minutes per day, 95% CI 4 to 15; 2 studies, 423 participants; high‐certainty evidence). These interventions also demonstrated improvements in other measures of physical activity.

Other interventions included self‐management strategies, nutritional supplementation, supplemental oxygen, endobronchial valve surgery, non‐invasive ventilation, neuromuscular electrical stimulation and inspiratory muscle training.

Authors' conclusions

A diverse range of interventions have been assessed, primarily in single studies. Improvements in physical activity have not been systematically demonstrated following any particular intervention. There was limited evidence for improvement in physical activity with strategies including exercise training, physical activity counselling and pharmacological management. The optimal timing, components, duration and models for interventions are still unclear. Assessment of quality was limited by a lack of methodological detail. There was scant evidence for a continued effect over time following completion of interventions, a likely requirement for meaningful health benefits for people with COPD.

Plain language summary

What are the most effective ways to encourage people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to be more physically active?

Background

Being physically active is important for everyone's health. It can be particularly difficult for people with COPD and we do not know the best way to improve physical activity.

Study characteristics

This review includes 76 studies involving 8018 people with COPD (published before 27 June 2019). Most studies were funded by government bodies, although some were sponsored by equipment or drug manufacturers. Many strategies have been developed and different studies have measured physical activity in lots of different ways. This means that it was hard to compare and combine their findings. It was also hard to tell exactly what was involved in some of the interventions, and therefore which components were important for improving physical activity.

Key results

Some studies looked at current interventions for people with COPD, including pulmonary rehabilitation and different types of exercise training as well as self‐management and education. Other studies have looked at special types of nutritional supplements, oxygen therapy, surgery, muscle stimulation and singing.

Some strategies that did work involved exercise training, physical activity counselling and COPD medications. Some studies showed that people did an extra 6 to 24 minutes of at least moderate‐intensity physical activity, as well as walking for longer or taking more steps each day. However, we are still uncertain about when or how these approaches should be used. Only a few studies followed people up after the intervention finished. It is not clear exactly what needs to be done to improve physical activity in the long term, which is what may be required for health benefits.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of evidence was generally low, due to difficulties working out exactly what people did in the studies, and also because there were lots of single studies (some quite small) looking at different types of interventions. This means that it was difficult to generalise these findings to all people with COPD.

Summary of findings

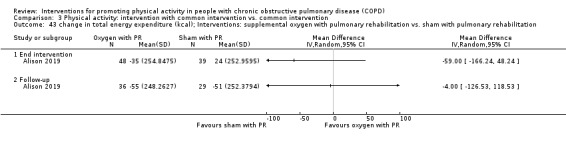

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Pulmonary rehabilitation/exercise training versus no intervention.

|

Population: people with COPD, clinical stability Intervention: pulmonary rehabilitation/exercise training Comparisons: intervention versus no intervention Outcome: time in physical activity (of at least moderate intensity) at end intervention | ||||||

| Interventions | Outcome | Illustrative comparative risks* [mean difference (95% CI) unless indicated] | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No intervention | Pulmonary rehabilitation/exercise training | |||||

| Pulmonary rehabilitation vs. no intervention (8 to 10 weeks) |

Time/change in time in MVPA | The mean change in time ranged from −1 to 6 minutes per day, mean time 27 minutes per day | The mean difference was 4 (−2 to 9) minutes per day | 190 participants (3 studies; Analysis 1.2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | Baseline values: De Roos 2017 no intervention mean 11 (SD 10), pulmonary rehabilitation 12 (11); Wootton 2017 no intervention 46 (39), pulmonary rehabilitation 54 (43) |

| High‐intensity interval training vs. no intervention (8 to 12 weeks) |

Time in MVPA | The mean time ranged from 12 to 14 minutes per day | The mean difference was 6 (4 to 8) minutes per day | 275 participants (2 studies; Analysis 1.9) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb |

‐ |

| Maintenance (telerehabilitation) following high‐intensity interval training vs. no intervention (12 months) |

Time in moderate intensity physical activity | The mean time was 11 minutes per day | The mean difference was 7 (4 to 10) minutes per day | 97 participants (1 study; Vasilopoulou 2017; Table 2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb |

‐ |

| Maintenance (centre‐based) following high intensity interval training vs. no intervention (12 months) |

The mean difference was 11 (8 to 14) minutes per day | 100 participants (1 study; Vasilopoulou 2017; Table 2) | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MVPA: moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity; SD: standard deviation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for high risk of performance bias. Downgraded one level for imprecision as CI does not exclude possibility of no effect. bDowngraded one level for high risk of performance bias.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Physical activity: intervention vs. no intervention, Outcome 2 time/change in time in moderate‐to‐vigorous intensity physical activity (minutes per day); Intervention: pulmonary rehabilitation/exercise training.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Physical activity: intervention vs. no intervention, Outcome 9 time in moderate‐to‐vigorous intensity physical activity (minutes per day); Intervention: high‐intensity interval training.

1. Physical activity outcomes.

| Study |

Comparison (setting, if known) Clinical stability unless indicated |

Timepoint (end intervention unless indicated) | Outcome (minutes unless indicated) | Intervention group | Comparison group | Between‐group MD (95% CI) where available unless indicated | ||

| n | mean (95% CI) unless indicated | n | mean (95% CI) unless indicated | |||||

| Altenburg 2015 | Physical activity counselling vs. no intervention (primary care) | 12 weeks | ∆ step count (n) | 22 | median 537 (IQR −611 to 1740) | 18 | median 431 (IQR −899 to 749) | P = 0.48* |

| ∆ "daily physical activity" (n) | median 1408 (IQR −2165 to 3304) | median 528 (IQR −966 to 2179) | P = 0.35* | |||||

| follow‐up (12 months post‐intervention) | ∆ step count (n) | 20 | median 157 (IQR −1679 to 994) | 18 | median 48 (IQR −1004 to 885) | P = 0.90* | ||

| ∆ "daily physical activity" (n) | median 353 (IQR −1518 to 3038) | median −576 (IQR −2517 to 1008) | P = 0.26* | |||||

| Physical activity counselling vs. no intervention (secondary care) | 12 weeks | ∆ step count (n) | 21 | median 1002 (IQR −612 to 3077) | 22 | median −814 (IQR −2827 to 1063) | P = 0.007* | |

| ∆ "daily physical activity" (n) | median 1575 (IQR −752 to 3864) | median −1041 (IQR −1971 to 1031) | P = 0.007* | |||||

| follow‐up (12 months post‐intervention) | ∆ step count (n) | 20 | median 1128 (IQR −1322 to 2707) | 19 | median −217 (IQR −1951 to 1147) | P = 0.15* | ||

| ∆ "daily physical activity" (n) | median 1798 (IQR −1994 to 3128) | median −718 (IQR −1812 to 512) | P = 0.11* | |||||

| Physical activity counselling with PR vs. PR | 12 weeks | ∆ step count (n) | 22 | median 547 (IQR 187 to 1323) | 15 | median −211 (IQR −1337 to 1038) | P = 0.03* | |

| ∆ "daily physical activity" (n) | median 1302 (IQR −173 to 1922) | median −849 (IQR −2223 to 961) | P = 0.03* | |||||

| follow‐up (12 months post‐intervention) | ∆ step count (n) | 10 | median −569 (IQR −2512 to 1551) | 13 | median −1137 (IQR −2376 to 1427) | P = 0.58* | ||

| ∆ "daily physical activity" (n) | median −213 (IQR −4525 to 2274) | median −1827 (IQR −3540 to 629) | P = 0.97* | |||||

| Physical activity counselling vs. no intervention (primary care) SUBGROUP: ≥ 10,000 steps per day (baseline) |

12 weeks | ∆ step count (n) | median 675 (IQR 4 to 1853) | median 342 (IQR −955 to 658) | P = 0.20* | |||

| ∆ "daily physical activity" (n) | median 1807 (IQR 164 to 3720) | median 519 (IQR −1089 to 1709] | P = 0.11* | |||||

| follow‐up (12 months post‐intervention) | ∆ step count (n) | median 201 (IQR −693 to 1170) | median 38 (IQR −1071 to 821) | P = 0.55* | ||||

| ∆ "daily physical activity" (n) | median 525 (IQR −545 to 3078) | median −726 (IQR −2954 to 711) | P = 0.06* | |||||

| Physical activity counselling vs. no intervention (secondary care) SUBGROUP: ≤ 10,000 steps per day (baseline) |

12 weeks | ∆ step count (n) | median 1289 (IQR −183 to 3107) | median 34 (IQR −1707 to 1095) | P = 0.02* | |||

| ∆ "daily physical activity" (n) | median 1763 (IQR −763 to 3913) | median −925 (IQR −1452 to 1052) | P = 0.03* | |||||

| follow‐up (12 months post‐intervention) | ∆ step count (n) | median 1436 (IQR −1492 to 2722) | median 0 (IQR −1825 to 1103) | P = 0.12* | ||||

| ∆ "daily physical activity" (n) | median 1928 (IQR −1140 to 3320) | median −526 (IQR −1657 to 435) | P = 0.078* | |||||

| Physical activity counselling with PR vs. PR SUBGROUP: ≤ 10,000 steps per day (baseline) |

12 weeks | ∆ step count (n) | median 547 (IQR 187 to 1323) | median −198 (IQR −1403 to 1051) | P = 0.04* | |||

| ∆ "daily physical activity" (n) | median 1302 (IQR −173 to 1922) | median −843 (IQR −1737 to 1329) | P = 0.052* | |||||

| follow‐up (12 months post intervention) | ∆ step count (n) | median −569 (IQR −1770 to 2170) | median −759 (IQR −2027 to 1641) | P = 0.78* | ||||

| ∆ "daily physical activity" (n) | median −213 (IQR −4525 to 2274) | median −644 (IQR −3706 to 844) | P = 0.91* | |||||

| Beeh 2014 | LAMA vs. placebo | 3 weeks | ∆ step count (n) | 51 | median 69 (IQR −834 to 1262) | 53 | median 125 (IQR −1180 to 1249) | P = 0.73 |

| ∆ MVPA time | median 1 (IQR −22 to 25) | median −6 (IQR −21 to 15) | P = 0.11 | |||||

| ∆ PAL | median 0.00 (IQR −0.08 to 0.09) | median −0.01 (IQR −0.09 to 0.09) | P = 0.95 | |||||

| ∆ active EE (kcal) | median 10 (−131 to 116) | median −44 (IQR −122 to 40) | P = 0.11 | |||||

| Bender 2016 | Physical activity counselling with pedometer vs. pedometer | 12 weeks | step count (n) | 49 | x | 50 | x | x |

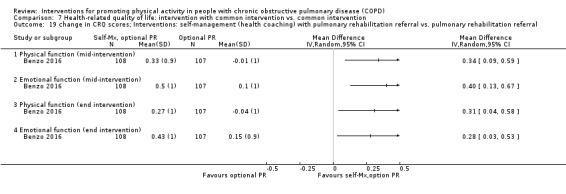

| Benzo 2016 | Self‐management (health coaching) with PR referral vs. PR referral | 12 months | ∆ PAL | 108 | mean −0.10 | 106 | mean 0.01 | P = not significant* |

| step count (n) | only baseline values reported | only baseline values reported | "We did not find a difference in any physical activity outcome between the intervention and control arms at any time point"* | |||||

| time sedentary | ||||||||

| LIPA time | ||||||||

| MPA time | ||||||||

| VPA time | ||||||||

| resting metabolic rate (calories per 24 hours) | ||||||||

| total EE (calories per 24 hours) | ||||||||

| Blumenthal 2014 | Self‐management vs. education and symptom management | 16 weeks | activity time | 162 | mean 13 (SE 1) | 164 | mean 11 (SE 1) | P = 0.045* |

| MPA time | mean 6 (SE 0.4) | mean 5.5 (SE 0.4) | 0.5 (−0.6 to 1.6) | |||||

| total EE ("caloric expenditure") | mean 3605 (SE 211) | mean 3113 (SE 212) | P = 0.022* | |||||

| Borges 2014 | Exercise training (whole‐body resistance training) vs. no intervention (inpatient) | 4‐week follow‐up | time lying | 15 | mean 224 (SD 131) | 14 | mean 203 (SD 140) | 21 (−78 to 120) |

| time sitting | mean 287 (122) | mean 298 (SD 107) | −11 (−94 to 72) | |||||

| time standing | mean 168 (104) | mean 153 (SD 94) | 15 (−57 to 87) | |||||

| time walking | mean 31 (21) | mean 50 (SD 35) | −19 (−40 to 2) | |||||

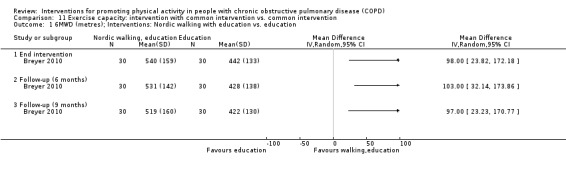

| Breyer 2010 | Nordic walking with education vs. education | 12 weeks | ∆ time sitting | 30 | mean −128 (SD 15) | 30 | "Controls did not show any significant change in their daily physical activities at any time point" | P = 0.014* |

| ∆ time standing | mean 129 (SD 26) | x | ||||||

| ∆ time walking | mean 15 (SD 20) | P = 0.034* | ||||||

| follow‐up (3 months post‐intervention) | ∆ time sitting | mean −120 (SD 32) | P < 0.05* | |||||

| ∆ time standing | mean 133 (SD 14) | P < 0.05* | ||||||

| ∆ time walking | mean 13 (SD 2) | x | ||||||

| follow‐up (6 months post‐intervention) | time sitting | mean 233 (SD 172) | mean 342 (SD 126) | P < 0.01* | ||||

| time standing | mean 320 (SD 178) | mean 220 (SD 130) | P = 0.16 | |||||

| time walking | mean 56 (SD 38) | mean 32 (SD 25) | P < 0.01 | |||||

| Chaplin 2017 | Web‐based PR vs. centre‐based PR | 7 weeks | step count (n) | 20 | x | 34 | x | P = 0.37* |

| "20 min bouts of purposeful activity" (n) | mean change 10% | x | P = 0.26* | |||||

| Charususin 2018 | Inspiratory muscle training with PR vs. sham with PR | 12 weeks (total n = 150) | step count (n) | x | mean 3958 (SD 2253) | x | mean 4506 (SD 1899) | −206 (−923 to 512)* |

| Curtis 2016 | ACE inhibitor with PR vs. placebo with PR | 10 weeks | ∆ step count (n) | 18 | mean −382 (SD 2082) | 22 | mean 561 (SD 2528) | −943 (−2372 to 486) |

| ∆ PAL | mean −0.06 (SD 0.16) | mean 0.04 (SD 0.15) | −0.10 (−0.20 to −0.00) | |||||

| Demeyer 2017 | Physical activity counselling vs. no intervention | 12 weeks | ∆ time walking | 140 | 7 (1 to 13) | 140 | −10 (−14 to −6) | 17 (10 to 24) |

| ∆ intensity movement (m/s2) | 0.06 (0.02 to 0.10) | −0.03 (−0.06 to −0.00) | 0.09 (0.04 to 0.14) | |||||

| ∆ MVPA time | 8 (5 to 12) | −3 (−6 to 0.2) | 11 (7 to 15) | |||||

| Duiverman 2008 | Non‐invasive ventilation with PR vs. PR | 12 weeks | step count (n) | 24 | median 2799 (IQR 891 to 6135) | 32 | median 2093 (IQR 914 to 3155) | median 1269 (IQR 242 to 2296)* |

| Felcar 2018 | Water‐based exercise training vs. land‐based exercise training | 6 months | active (n) (> 7500 steps per day) | 20 | baseline 4 end intervention 10 |

16 | baseline 4 end intervention 5 |

x |

| Hartman 2016 | Endobronchial valve surgery vs. no intervention | 6 months post‐surgery | ∆ step count (n) | 19 | 1252 (545 to 1960) | 24 | −148 (−512 to 216) | 1400 (655 to 2145) |

| ∆ time walking (%) | 1 (0 to 2) | 0 (−1 to 0) | 1 (0 to 2) | |||||

| ∆ time sitting (%) | 0 (−3 to 3) | 2 (1 to 3) | −2 (−5 to 1) | |||||

| ∆ time inactive | −1 (−3 to 1) | 0 (−1 to 1) | −1 (−3 to 1) | |||||

| ∆ intensity movement (g) | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.01) | 0.00 (−0.01 to 0.00) | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.02) | |||||

| Hornikx 2015 | Physical activity counselling vs. no intervention | 4 weeks | ∆ step count (n) | 12 | 984 (217 to 1752) | 14 | 1013 (307 to 1719) | −29 (−969 to 911) |

| ∆ time walking | 13 (3 to 23) | 13 (5 to 21) | 0 (−12 to 12) | |||||

| ∆ intensity movement (m/s2) | 0.06 (0.03 to 0.09) | 0.08 (−0.05 to 0.11) | −0.02 (−0.06 to 0.02) | |||||

| Jolly 2018 | Self‐management vs. no intervention | 12 months | MVPA time a week | 179 | mean 347 (SD 277) | 232 | mean 316 (SD 256) | 12 (−21 to 45)* |

| Kanabar 2015 | Self‐management (SPACE) vs. no intervention (post‐admission) | 7 days | ∆ step count (n) | 15 | −208 (−1146 to 730) | 10 | −518 (−2572 to 1536) | 310 (−1665 to 2285) |

| ∆ time sedentary | −14 (−71 to 43) | −18 (−87 to 51) | 4 (−75 to 83) | |||||

| ∆time in "physical activity" | −1 (−14 to 12) | −16 (−66 to 34) | 15 (−30 to 60) | |||||

| ∆ MPA time | −1 (−14 to 12) | −14 (−61 to 33) | 13 (−30 to 56) | |||||

| ∆ VPA time | 0 (−1 to 1) | −2 (−61 to 2) | 2 (−1 to 5) | |||||

| ∆ total EE (kcal) | −128 (−236 to −20) | −98 (−292 to 96) | −30 (−225 to 165) | |||||

| ∆ active EE (kcal) | −12 (−77 to 53) | −97 (−310 to 116) | 85 (−108 to 278) | |||||

| Kawagoshi 2015 | Physical activity counselling with PR vs. PR | 12 months | ∆ time sitting | 12 | 59 (−6 to 124) | 15 | 6 (−44 to 56) | 53 (−21 to 127) |

| ∆ time standing | 43 (24 to 60) | 31 (5 to 57) | 11 (−18 to 40) | |||||

| ∆ time walking | 51 (10 to 92) | 12 (−2 to 27) | 39 (1 to 78) | |||||

| ∆ time lying | −53 (−96 to −10) | −29 (−60 to 2) | −24 (−72 to 24) | |||||

| ∆ frequency postural changes: total (n) | 40 (−2 to 82) | 19 (−5 to 43) | 21 (−23 to 65) | |||||

| ∆ frequency postural changes: getting up (n) | 0 (−16 to 16) | 6 (−11 to 23) | −6 (−27 to 15) | |||||

| ∆ frequency postural changes: standing up (n) | 43 (5 to 81) | 14 (−5 to 33) | 29 (−9 to 67) | |||||

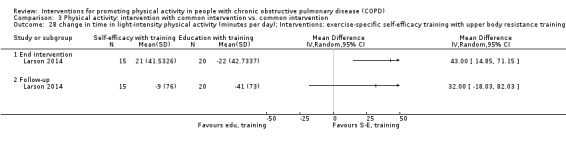

| Larson 2014 | Exercise‐specific self‐efficacy training with upper‐body resistance training vs. upper‐body resistance training | 4 months | time sedentary | 15 | mean 602 (SD 112) | 20 | mean 577 (SD 107) | 25 (−49 to 99) |

| time sedentary (% monitored time) | mean 70 (SD 10) | mean 70 (SD 9) | 0 (−6 to 6) | |||||

| MVPA time | mean 6 (SD 6) | mean 4 (SD 3) | 2 (−1 to 5) | |||||

| Upper‐body resistance training with health education vs. health education | time sedentary | 20 | mean 577 (SD 107) | 14 | mean 634 (SD 114) | −57 (−133 to 19) | ||

| time sedentary (% monitored time) | mean 70 (SD 9) | mean 70 (SD 9) | −2 (−8 to 4) | |||||

| MVPA time | mean 4 (SD 3) | mean 3 (SD 2) | 1 (−1 to 3) | |||||

| Loeckx 2018 | Physical activity counselling with PR vs. PR | 12 weeks | ∆ step count (n) | 25 | x | 25 | x | MD 1319 (SE 571), P = 0.02* |

| ∆ MVPA time | MD 8 (SE 4), P = 0.11* | |||||||

| 9 months (follow‐up) | ∆ step count (n) | MD 1348 (SE 628), P = 0.03* | ||||||

| ∆ MVPA time | MD 13 (SE 5), P = 0.02* | |||||||

| Lord 2012 | Singing vs. sham | 8 weeks | ∆ step count (n) | 13 | −763 (−1758 to 232) | 11 | 1011 (337 to 1685) | −1774 (−2848 to −700) |

| ∆ time sedentary | −36 (−113 to 41) | −27 (−72 to 18) | −9 (−88 to 71) | |||||

| ∆ “physical activity duration” | −93 (−224 to 38) | 50 (22 to 77) | −142 (−263 to −22) | |||||

| ∆ "activity‐related" EE (kJ) | −144 (−408 to 119) | 229 (131 to 327) | −373 (−625 to −121) | |||||

| Louvaris 2016 | High‐intensity interval training vs. no intervention | 12 weeks | step count (n) | 85 | mean 5136 (SD 2866) | 43 | mean 3453 (SD 2493) | 1683 (721 to 2646) |

| vector magnitude units (n) | mean 495 (SD 213) | mean 406 (SD 205) | 89 (13 to 165) | |||||

| "sedentarism" (%) (< 5000 steps per day) | baseline 69 end intervention 48 |

baseline 68 end intervention 69 |

x | |||||

| Magnussen 2017 | LAMA vs. placebo | 3 weeks | ∆ step count (n) | 14 | median 177 (IQR −222 to 1038) | 15 | median 86 (IQR −366 to 1000) | P = 0.63 |

| ∆ MVPA time | median −2 (IQR −12 to 26] | median −4 (IQR −16 to 19) | P = 0.51 | |||||

| ∆ PAL | median 0.01 (IQR −0.03 to 0.07] | median 0.01 (IQR −0.06 to 0.04) | P = 0.71 | |||||

| ∆ active EE (kcal) | median 43 (IQR −25 to 153) | median 17 (IQR −69 to 50) | P = 0.51 | |||||

| Mantoani 2018 | Physical activity counselling with PR vs. PR | 12 weeks | ∆ step count (n) | 22 | mean 1251 (SD 2408) | 22 | mean −410 (SD 1118) | 1661 (552 to 2770) |

| Mendoza 2015 | Pedometer with physical activity counselling vs. physical activity counselling | 12 weeks | ∆ step count (n) | 50 | mean 3080 (SD 3255) | 47 | mean 138 (SD 1950) | 2942 (1881 to 4003) |

| Mitchell 2013 | Self‐management (SPACE) vs. no intervention | 6 weeks | ∆ step count (n) | 52 | 333 (−85 to 751) | 65 | −214 (−566 to 138) | 547 (12 to 1082) |

| ∆ time sedentary | −10 (−53 to 33) | 13 (−21 to 47) | −23 (−77 to 31) | |||||

| ∆ total EE (kcal) | −4 (−105 to 97) | −20 (−83 to 43) | 16 (−100 to 132) | |||||

| time in bouts (data from graph) | median 142 (95% CI 91 to 190) | median 96 (95% CI 56 to 135) | P = 0.215* | |||||

| Nakamura 2016 | LAMA (aclidinium bromide) vs. LAMA (tiotropium) | 8 weeks | "physical activity with sedentary time" | 22 | x | 22 | x | P = 0.385* |

| NCT00144326 | LAMA vs. placebo | 12 weeks | not defined | 123 | x | 125 | x | "increase of activity in tiotropium relative to placebo from 7.9% to 12.23%" "the majority of the mean values over time in the tiotropium group are larger than those in the placebo group" |

| NCT01351792 | ICS (beclomethasone) with LABA (formoterol) vs. ICS (budesonide) with LABA (formoterol) | 16 weeks (4‐week run‐in, 12 week intervention) | step count (n) | 30 | mean 3826 (SD 2097) | 29 | mean 3510 (SD 2409) | 316 (−838 to 1470) |

| Ng 2015 | Four‐wheeled walker vs. no intervention | 4 weeks | step count (n) | 8 | mean 6465 (SD 4541) minimum 3039, maximum 16,558 |

9 | mean 2384 (SD 1319) minimum 574, maximum 4453 |

4081 (818 to 7344) N.B. no baseline assessment; likely imbalance, data skewed |

| Nolan 2017 | Physical activity counselling with PR vs. PR | 8 weeks (mid‐intervention, post‐PR) | ∆ step count (n) (SenseWear) | 63 | median 272 (IQR −342 to 782) | 59 | median 155 (IQR −438 to 867) | P = 0.99* |

| ∆ step count (n) (pedometer) | median 727 (IQR −1493 to 3119) | median 892 (IQR −1187 to 2534) | P = 0.55* | |||||

| ∆ MVPA time | median 11 (IQR −1 to 33) | median 11 (IQR −2 to 28) | P = 0.62* | |||||

| 6 months | ∆ step count (n) (SenseWear) | 56 | median −263 (IQR −778 to 197) | 57 | median −461 (IQR −1168 to −62) | P = 0.09* | ||

| ∆ step count (n) (pedometer) | median 116 (IQR −1698 to 3200) | median 481 (IQR −1931 to 1781) | P = 0.85* | |||||

| ∆ MVPA time | median 2 (IQR −12 to 25) | median 12 (IQR −7 to 31) | P = 0.16* | |||||

| ∆ LIPA time | 44 | median 13 (IQR −38 to 33) | 49 | median 0 (IQR −62 to 36) | P = 0.60* | |||

| ∆ time sedentary | median 2 (IQR −38 to 62) | median 22 (IQR −36 to 81) | P = 0.31 | |||||

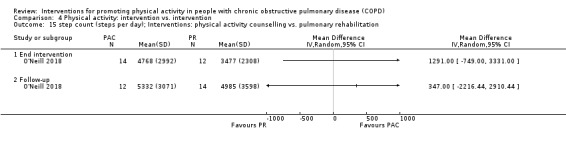

| O'Neill 2018 | Physical activity counselling vs. PR | 12 weeks physical activity counselling, 6 weeks PR | ∆ MVPA time | 14 | 7 (−10 to 24) | 12 | 1 (−3 to 5) | 6 (−10 to 22) |

| ∆ MVPA bouts (n) | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.1) | −0.03 (−0.1 to 0.05) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.8) | |||||

| ∆ MVPA time in bouts | 9 (−4 to 22) | −0.4 (−1 to 1) | 10 (−2 to 21) | |||||

| Orme 2018 | Feedback and education vs. no intervention; Education vs. no intervention; Feedback with education vs. education (post‐admission) | 14 days | ∆ step count (n) | no group data presented | ||||

| "stationary" time | ||||||||

| "light activity" time | ||||||||

| MVPA time | ||||||||

| Ogasawara 2018 | Enriched nutritional supplement with inpatient PR vs. nutritional supplement with inpatient PR | hospital discharge | ∆ step count | 24 | mean 1900 (SD 2110) | 21 | mean 1700 (SD 1694) | 200 (−913 to 1313) |

| ∆ EE (kcal) | mean 1521 (SD 285) | mean 1441 (SD 235) | 80 (−72 to 232) | |||||

| Priori 2017 | Physical activity counselling vs. no intervention | 4 weeks (mid intervention) | % ∆ MPA time | 10 | mean 19 (SD 30) | 8 | mean −5 (SD 13) | 2 (4 to 45) |

| 8 weeks | mean 20 (SD 29) | mean −12 (SD 22) | 32 (8 to 55) | |||||

| Probst 2011 | Exercise training (callisthenics) vs. exercise training (endurance and strength training) | 12 weeks (data from graph) | step count (n) | 20 | mean 4235 (SD 822) | 20 | mean 4198 (SD 680) | "There were no significant inter‐group differences in any variable"* |

| time walking | mean 43 (SD 26) | mean 53 (SD 39) | ||||||

| time standing | mean 231 (SD 123) | mean 243 (SD 106) | ||||||

| time sitting | mean 334 (SD 126) | mean 318 (SD 108) | ||||||

| time lying | mean 115 (SD 89) | mean 100 (SD 78) | ||||||

| MVPA time | mean 55 (SD 15) | mean 75 (SD 19) | ||||||

| active EE (kcal) | mean 335 (SD 104) | mean 389 (SD 119) | ||||||

| total EE (kcal) | mean 1362 (SD 186) | mean 1318 (SD 113) | ||||||

| Saini 2017 | Physical activity counselling vs. no intervention | 8 weeks (total n = 28) | % ∆ MPA time | x | mean −9 (SD 24) | x | mean −21 (SD 21) | P = 0.116* |

| Sandland 2008 | Supplemental oxygen vs. placebo (air) | 8 weeks | % ∆ "domestic activity counts" | 10 | mean 7 (SD 54) | 10 | mean −8 (SD 19) | 15 (−21 to 51) |

| Sena 2013 | Exercise training (eccentric cycle training) vs. exercise training (concentric cycle training) |

10 weeks | "physical activity levels" | 8 | x | 8 | x | "unchanged"* |

| Singh 1998 | Aware of purpose of pedometer with PR vs. unaware of purpose of pedometer with PR | 7 days | step count (n) | 10 | mean 4098 | 9 | mean 3679 | MD 419 "no significant difference between groups"* |

| Steele 2019 | Adherence intervention vs. PR | 6 months (follow‐up) | step count (n) | 32 | mean 5045 (SD 3147) | 31 | mean 5204 (SD 3261) | −159 (−1742 to 1424) |

| peak performance | mean 56 (SD 19) | mean 56 (SD 19) | 0 (−9 to 9) | |||||

| time inactive (%) | mean 68 (SD 15) | mean 70 (SD 13) | −2 (−9 to 5) | |||||

| Tabak 2014a | Physical activity counselling with optional supervised exercise vs. optional supervised exercise | 4 weeks | step count (n) | 13 | mean 5603 (SD 3475) | 16 | mean 4617 (SD 3460) | 986 (−1553 to 3525) |

| Tahirah 2015 | Exercise training (progressive walking and functional‐resistance exercises) vs. no intervention (inpatient) | hospital discharge | step count (n) | 17 | median 4215 (IQR 2133 to 6693) | 17 | median 2198 (IQR 1242 to 4857) | P = 0.07** |

| Troosters 2014 | LAMA with behavioural management vs. placebo with behavioural management | 6 months | step count (n) | 221 | mean 6485 | 205 | mean 6122 | x |

| MVPA time | mean 72 | mean 64 | MD 8 | |||||

| LIPA time | mean 111 (SD 82) | mean 101 (SD 80) | 10 (−6 to 26) | |||||

| inactive (%) (< 6000 steps per day) | mean 40 | mean 43 | OR 0.86 (95% CI 0.57 to 1.30) P = 0.477* | |||||

| Tsai 2016 | PR (telerehabilitation) vs. no intervention | 8 weeks | ∆ PAL | 19 | −0.03 (−0.1 to 0.02) | 17 | −0.02 (−0.1 to 0.1) | 0.08 (−0.1 to 0.1) |

| Vasilopoulou 2017 | Maintenance (telerehabilitation) following HIIT vs. no intervention | 12 months (data from graph) | time sedentary | 47 | mean 584 (SD 98) | 50 | mean 615 (SD 76) | −31 (−66 to 4) |

| LIPA time | mean 157 (SD 44) | mean 113 (SD 44) | 44 (27 to 62) | |||||

| MPA time | mean 18 (SD 6) | mean 11 (SD 7) | 7 (4 to 10) | |||||

| "lifestyle" physical activity time | mean 41 (SD 16) | mean 34 (SD 16) | 7 (1 to 13) | |||||

| Maintenance (centre‐based) following HIIT vs. no intervention | time sedentary | 50 | mean 551 (SD 83) | 50 | 615 (SD 76) | −64 (−95 to −33) | ||

| LIPA time | mean 159 (SD 43) | 113 (SD 44) | 46 (29 to 63) | |||||

| MPA time | mean 22 (SD 7) | 11 (SD 7) | 11 (8 to 14) | |||||

| "lifestyle" physical activity time | mean 52 (SD 17) | 34 (SD 16) | 18 (12 to 25) | |||||

| Maintenance (telerehabilitation) vs. maintenance (centre‐based) following HIIT | time sedentary | 47 | mean 584 (SD 98) | 50 | mean 551 (SD 83) | 33 (−3 to 69) | ||

| LIPA time | mean 157 (SD 44) | mean 159 (SD 43) | −2 (−19 to 15) | |||||

| MPA time | mean 18 (SD 6) | mean 22 (SD 7) | −4 (−7 to −1) | |||||

| "lifestyle" physical activity time | mean 41 (SD 16) | mean 52 (SD 17) | −11 (−18 to −4) | |||||

| Watz 2017 | LAMA/LABA vs. placebo | 4 weeks | inactive (%) (< 6000 steps per day) | 127 | mean 41 | 123 | mean 55 | OR 0.27 (95% CI 0.1 to 0.5)* |

| Widyastuti 2018 | Physical activity counselling vs. PR | 6 weeks | step count (n) | 18 | mean 6021 (SD 2549) | 18 | mean 6113 (SD 2403) | −92 (−1710 to 1526) |

| Wootton 2017 | Ground‐based walking vs. no intervention | 8 weeks | time sedentary (% awake time) | 62 | mean 69 (SD 10) | 39 | mean 68 (SD 10) | −2 (−6 to 2)* |

| LIPA time (% awake time) | mean 25 (SD 7) | mean 25 (SD 7) | 1 (−2 to 4)* | |||||

| MPA time (% awake time) | mean 7 (SD 5) | mean 7 (SD 5) | 1 (−2 to 4)* | |||||

| VPA time (% awake time) | mean 0 (SD 0) | mean 0 (SD 0) | 0 (0 to 0)* | |||||

| Physical activity counselling with pedometer vs. no intervention (following ground‐based walking training) | 12 months | ∆ total EE (kcal) | 23 | −75 (−156 to 6) | 20 | −80 (−166 to 5) | 17 (−131 to 164)* | |

| ∆ step count (n) | −157 (−753 to 439) | −1051 (−1687 to −424) | −617 (−1669 to 453)* | |||||

| ∆ time sedentary | −9 (−34 to 17) | −13 (−40 to 14) | −8 (−50 to 33)* | |||||

| ∆ LIPA time | 8 (−19 to 35) | −16 (−44 to 13) | −27 (−70 to 14)* | |||||

| ∆ MPA time | −11 (−23 to 1) | −1 (−13 to 12) | 20 (−1 to 41)* | |||||

| ∆VPA time | 0 (−1 to 1) | 0 (−1 to 1) | 0 (0 to 1)* | |||||

* from paper ** from author x data not provided Data are per day unless indicated

ACE: angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ∆ change from baseline; cpm: counts per minute; "daily physical activity": step count + metabolic equivalents; EE: energy expenditure; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; LABA: long‐acting beta2 agonist; LAMA: long‐acting muscarinic antagonist; LIPA: light‐intensity physical activity; MD: mean difference; METs: metabolic equivalents; MPA: moderate‐intensity physical activity; MVPA: moderate‐to‐vigorous intensity physical activity; n: number of participants; OR: odds ratio; PAL: physical activity level; PR: pulmonary rehabilitation; SPACE: self‐management programme of activity, coping and education; SD: standard deviation; VPA: vigorous‐intensity physical activity

Summary of findings 2. Comparison of types of pulmonary rehabilitation/exercise training.

|

Population: people with COPD, clinical stability Intervention: pulmonary rehabilitation/exercise training Comparisons: intervention vs. another intervention Outcome: time in physical activity (of at least moderate intensity) at end intervention | ||||||

| Interventions | Outcome | Illustrative comparative risks* [mean difference (95% CI) unless indicated] | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Comparator | Intervention of interest | |||||

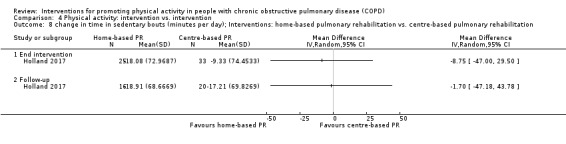

| Home‐based pulmonary rehabilitation vs. centre‐based pulmonary rehabilitation (8 weeks) |

Change in time in MVPA | The mean change in time in the centre‐based group was 5 minutes per day | The mean difference was 6 (−19 to 31) minutes per day | 58 participants (1 study; Analysis 4.2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | Baseline values: centre‐based median 79 (IQR 24 to 136), home‐based median 68 (IQR 29 to 121) |

| Calisthenics vs. exercise training (12 weeks) |

Time in MVPA | The mean time in the exercise training group was 75 minutes per day | "no significant inter‐group differences in any variable" | 40 participants (1 study; Probst 2011; Table 2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | ‐ |

| Physical activity counselling vs. pulmonary rehabilitation (6 to 12 weeks) |

Change in time in MVPA | The mean change in time in the pulmonary rehabilitation group was 1 (−3 to 5) minutes per day | The mean difference was 6 (−10 to 22) minutes per day | 26 participants (1 study; O'Neill 2018; Table 2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | Baseline values: pulmonary rehabilitation mean 15 (SD 5), physical activity counselling mean 14 (SD 15) |

| Telerehabilitation maintenance programme vs. centre‐based maintenance programme (following high‐intensity interval training, 12 months) |

Time in moderate‐intensity physical activity | The mean time in the centre‐based group was 22 minutes per day | The mean difference was −4 (−7 to −1) minutes per day | 97 participants (1 study; Vasilopoulou 2017; Table 2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatec |

‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; IQR: interquartile range; MVPA: moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity; SD: standard deviation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for high risk of performance bias. Downgraded one level for imprecision as CI does not exclude possibility of no effect.

bDowngraded one level for unclear risk of selection, performance, detection, attrition and other potential bias. Downgraded one level for imprecision as CI does not exclude possibility of no effect. cDowngraded one level for high risk of performance bias.

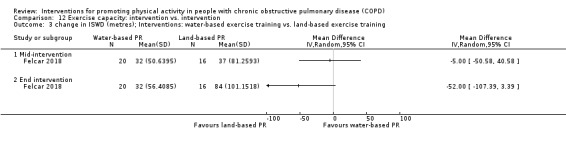

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Physical activity: intervention vs. intervention, Outcome 2 change in time in moderate‐to‐vigorous intensity physical activity (minutes per day); Interventions: home‐based pulmonary rehabilitation vs. centre‐based pulmonary rehabilitation.

Summary of findings 3. Physical activity counselling.

|

Population: people with COPD, clinical stability Intervention: physical activity counselling Comparisons: intervention vs. no intervention, intervention in addition to a standard intervention common to both groups Outcome: time in physical activity (of at least moderate intensity) at end intervention | ||||||

| Interventions | Outcome | Illustrative comparative risks* [mean difference (95% CI) unless indicated] | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Comparator | Intervention of interest | |||||

| Comparison: intervention vs. no intervention | ||||||

| Physical activity counselling vs. no intervention (12 weeks) |

Change in time in MVPA | The mean change in time was −3 (−0.6 to 0.2) minutes per day | The mean difference was 11 (7 to 15) minutes per day | 280 participants (1 study; Demeyer 2017; Table 2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea |

Baseline values: no intervention median 15 (IQR 5 to 35), intervention median 14 (IQR 5 to 26) |

| Physical activity counselling vs. no intervention (following pulmonary rehabilitation, 12 months) |

Change in time in moderate intensity physical activity | The mean change was −1 (−13 to 12) minutes per day | The mean difference was 20 (−1 to 41) minutes per day | 43 participants (1 study; Wootton 2017; Table 2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | Baseline values: no intervention mean 51 (SD 49), intervention mean 59 (SD 52) |

| Comparison: intervention in addition to a standard intervention common to both groups | ||||||

| Physical activity counselling with pulmonary rehabilitation vs. pulmonary rehabilitation (6 months) |

Time in MVPA | The mean time in the pulmonary rehabilitation group was 28 minutes per day | The mean difference was 24 (2 to 45) minutes per day | 26 participants (1 study; Analysis 3.21) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatec |

P = 0.03 |

| Change in time in MVPA | The median change in time in the pulmonary rehabilitation group was 12 minutes per day | The median change in time was 2 (−12 to 25) minutes per day | 113 participants (1 study; Nolan 2017; Table 2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowd | P = 0.16 Baseline values: no intervention median 47 (IQR 18 to 103), intervention median 45 (IQR 20 to 81) |

|

| Physical activity counselling with pulmonary rehabilitation vs. sham intervention with pulmonary rehabilitation (6 months) |

Change in time in MVPA | The mean change in time in the pulmonary rehabilitation group was 0 minutes per day | The mean difference was −6 (−16 to 3) minutes per day | 50 participants (1 study; Analysis 3.25) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowe | Baseline values: no intervention median 29 (IQR 17 to 44), intervention median 33 (IQR 16 to 47) |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; IQR: interquartile range; MVPA: moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity; SD: standard deviation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for high risk of performance bias and detection bias. bDowngraded one level for high risk of performance bias. Downgraded one level for imprecision as CI does not exclude possibility of no effect. cDowngraded one level for high risk of performance, detection and reporting bias. dDowngraded one level for high risk of performance bias. Downgraded one level for imprecision as results do not exclude possibility of no effect. eDowngraded one level for unclear risk of selection, reporting and other bias. Downgraded one level for imprecision as CI does not exclude possibility of no effect.

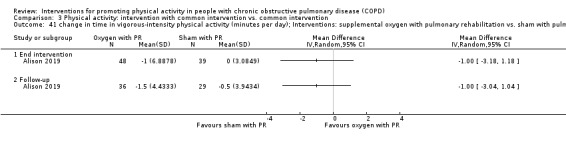

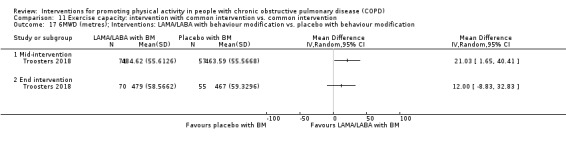

3.21. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Physical activity: intervention with common intervention vs. common intervention, Outcome 21 time in moderate‐to‐vigorous intensity physical activity (minutes per day); Interventions: physical activity counselling with pulmonary rehabilitation vs. pulmonary rehabilitation.

3.25. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Physical activity: intervention with common intervention vs. common intervention, Outcome 25 change in time in moderate‐to‐vigorous intensity physical activity (minutes per day); Interventions: physical activity counselling with pulmonary rehabilitation vs. sham with pulmonary rehabilitation.

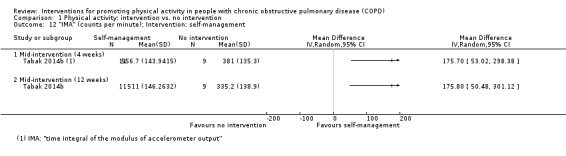

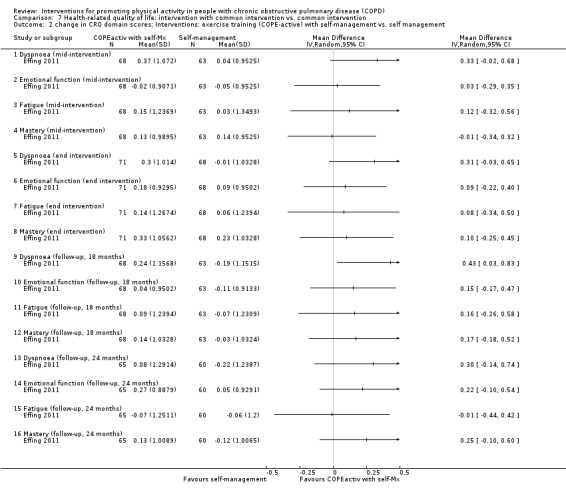

Summary of findings 4. Self‐management.

|

Population: people with COPD, clinical stability Intervention: self‐management Comparisons: intervention vs. no intervention, intervention in addition to a standard intervention common to both groups, intervention vs. another intervention Outcome: time in physical activity (of at least moderate intensity) at end intervention | ||||||

| Interventions | Outcome | Illustrative comparative risks* [mean difference (95% CI) unless indicated] | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Comparator | Intervention of interest | |||||

| Comparison: intervention vs. no intervention | ||||||

| Self‐management vs. no intervention (12 months) |

Time in MVPA | The mean time was 316 minutes a week | The mean difference was 12 (−21 to 45) minutes a week | 411 participants (1 study; Jolly 2018; Table 2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | P = 0.48 |

| Comparison: intervention in addition to a standard intervention common to both groups | ||||||

| Self‐efficacy training with upper limb exercise vs. education with upper limb exercise (16 weeks) |

Time in moderate‐intensity physical activity | The mean time in the education and upper‐limb exercise group was 4 minutes per day | The mean difference was 2 (−1 to 5) minutes per day | 35 participants (1 study; Larson 2014; Table 2) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | ‐ |

| Comparison: intervention vs. another intervention | ||||||

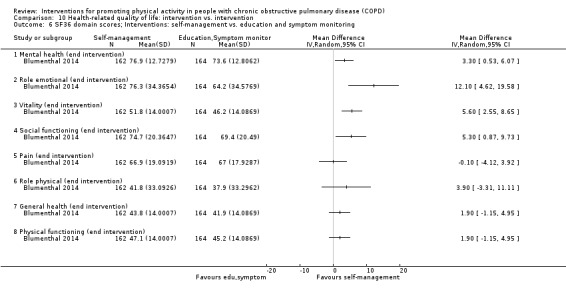

| Self‐management vs. education and symptom monitoring (16 weeks) |

Time in moderate‐intensity physical activity | The mean time in the self‐management group was 6 minutes per day | The mean difference was 1 (−1 to 2) minutes per day | 326 participants (1 study; Blumenthal 2014; Table 2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MVPA: moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for high risk of performance bias. Downgraded one level for imprecision as CI does not exclude possibility of no effect.

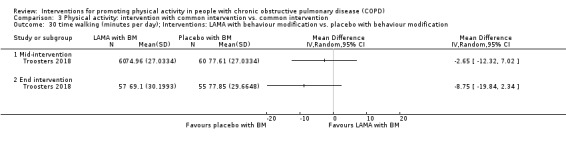

Summary of findings 5. Pharmacological interventions.

|

Population: people with COPD, clinical stability Intervention: pharmacological interventions Comparisons: intervention vs. placebo, intervention in addition to a standard intervention common to both groups Outcome: time in physical activity (of at least moderate intensity) at end intervention | ||||||

| Interventions | Outcome | Illustrative comparative risks* [mean difference (95% CI) unless indicated] | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Comparator | Intervention of interest | |||||

| Comparison: intervention vs. sham/placebo intervention | ||||||

| LAMA vs. placebo (3 weeks) |

Change in time in MVPA | The median change in time was −6 minutes per day | The median change in time was −1 (IQR −17 to 24) minutes per day | 131 participants (2 studies; Beeh 2014; Magnussen 2017; Table 2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea |

P = 0.07 Baseline values: Beeh 2014 placebo median 73 (IQR 38 to 135), LAMA median 74 (IQR 32 to 132) Magnussen 2017 placebo mean 88 (SD 65), intervention mean 57 (SD 32) |

| LAMA/LABA vs. placebo (3 to 4 weeks) |

Change in time in MVPA | The mean change in time ranged from −16 to −1 minutes per day | The mean difference was 10 (4 to 15) minutes per day | 423 participants (2 studies; Analysis 2.3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high |

Baseline values: Watz 2016 placebo mean 130, LAMA/LABA mean 125 |

| Comparison: intervention in addition to a standard intervention common to both groups | ||||||

| LAMA with behaviour modification vs. placebo with behaviour modification (12 weeks to 6 months) |

Time in MVPA | The mean time was 64 minutes per day | The mean difference was 8 minutes per day | 426 participants (1 study; Troosters 2014; Table 2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb |

P = "not statistically significantly different" |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; IQR: interquartile range; LABA: long‐acting beta2 agonist; LAMA: long‐acting muscarinic antagonist; MVPA: moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity; SD: standard deviation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for imprecision as results do not exclude possibility of no effect. bDowngraded one level for imprecision as no formal analysis of difference presented.

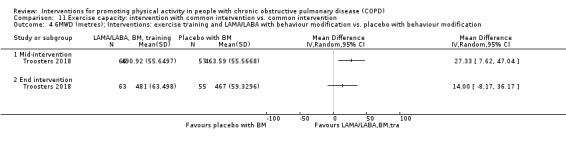

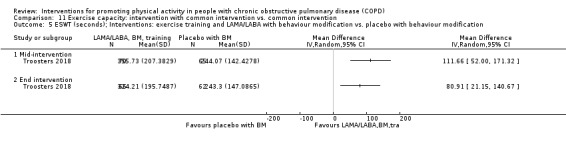

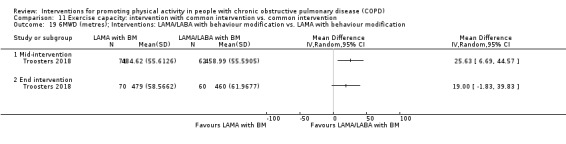

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Physical activity: intervention vs. placebo/sham, Outcome 3 change in time in moderate‐to‐vigorous intensity physical activity (minutes per day): Intervention: LAMA/LABA.

Background

Description of the condition

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common, treatable but incurable obstructive lung disease defined by persistent airflow limitation. Diagnosis is confirmed by spirometry in the clinical context of a person presenting with dyspnoea, chronic cough or sputum production, and a history of risk factor exposure (GOLD 2019). Development of COPD is primarily attributable to an enhanced chronic inflammatory airway response to noxious particles or gases, and is strongly linked to a history of smoking. However, there are a number of other risk factors including exposure to air pollution, occupational exposures, genetics, chronic asthma, history of severe childhood respiratory infections and low socioeconomic status (GOLD 2019). Systemic effects, including systemic inflammation and muscle dysfunction, and comorbid conditions, including cardiovascular disease, anxiety and depression, are commonly associated with COPD (Choudhury 2014). Prevalence studies suggest that COPD affects upwards of 384 million people (Adeloye 2015) and is the third leading cause of death worldwide (WHO 2017). Associated with advancing age (Anton 2016), and in the context of the fastest rate of population growth occurring in people over 65 years of age (UN 2015), COPD poses a substantial and growing economic and social burden globally (GOLD 2019).

Description of the intervention

We define the term ‘physical activity’ as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure (Casperson 1985). It is a complex behaviour traditionally described according to type, intensity and duration, and incorporates a subset of undertakings including exercise, occupational and household activities. Public health promotion for regular participation in physical activity typically recommends a minimum of 150 minutes a week of at least moderate‐intensity activity as ‘sufficient’ for health benefits across the adult population (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2018). These benefits include reduced risk of all‐cause mortality, coronary heart disease, hypertension, stroke, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes and depression (Lee 2012).

Participation in regular physical activity is also endorsed for people with COPD (GOLD 2019). Low levels of physical activity are one of the main risk factors for development of cardiovascular, metabolic and musculoskeletal comorbid conditions in people with COPD, and is observed across the disease spectrum (Van Remoortel 2014). Recent studies show that physical activity is reduced in smokers prior to diagnosis (Furlanetto 2014) and in people with a recent diagnosis and mild COPD before symptom onset (Johnson‐Warrington 2014). Physical activity participation is not clearly related to other clinical characteristics including impaired exercise capacity (Fastenau 2013; Gagnon 2015; Van Remoortel 2013; Watz 2009), but is reduced compared to healthy peers (Pitta 2005; Vorrink 2011) and to people with other chronic conditions (Arne 2009). It is further compromised during and after hospitalisation for an acute exacerbation (Pitta 2006a) and with increasing disease severity (Shrikrishna 2012; Troosters 2010; Waschki 2015). In people with COPD, low levels of participation in physical activity have been independently associated with poor outcomes, including increased risks of hospitalisation and mortality (Garcia‐Aymerich 2006; Garcia‐Rio 2012; Vaes 2014; Waschki 2011).

Much attention has been given to the development of physical activity interventions that incorporate strategies specifically designed to promote the adoption and maintenance of active lifestyles in the general population (Marcus 2006). Such interventions may be provided by a broad range of healthcare professionals and be delivered in a variety of ways (for example, in person, by internet or telephone).

How the intervention might work

Evidence suggests that people with COPD avoid participation in physical activity due to the perception of breathlessness, resulting from inefficiencies related to gas trapping and lung hyperinflation. A vicious circle is perpetuated, where muscle deconditioning results from avoiding activities that involve physical exertion and exacerbate symptoms, further compromising physical capacity to engage in activity (O’Donnell 2014). It is theorised that targeted interventions may be able to interrupt this cycle and increase participation in physical activity at a range of intensities that are associated with health benefits. The dual role of low physical activity levels as both a cause and consequence in chronic disease identifies physical activity as a potentially modifiable target that could affect health‐related quality of life and disease trajectory (Esteban 2010; Vaes 2014; Watz 2014a). Whether improvements in physical activity can ameliorate these effects in COPD is unknown.

Many physical and physiological disease features also appear to influence participation in physical activity by people with COPD. However, the quality of association between such features, including lung function, systemic inflammation, body composition, comorbidities and psychosocial factors, and physical activity participation is variable (Gimeno‐Santos 2011). Additional considerations, including fatigue (Andersson 2015), balance (Iwakura 2016), and seasonal and environmental factors (Alahmari 2015; Sewell 2010) may also impact on physical activity participation in this group. The broad range of strategies considered to date to address low levels of physical activity in people with COPD (for instance, exercise training, nutritional interventions and behavioural strategies) reflect the complexity of this issue.

There is evidence for a relationship between physical activity and rate of acute exacerbations (Esteban 2014) and therefore targeting improvements in physical activity in people with COPD may be an important therapeutic goal (Langer 2016; Singh 2016). However, achieving consistent improvements in participation and convincing evidence for the positive impact on health outcomes remain elusive.

Why it is important to do this review

Escalating awareness of the magnitude of the challenge posed by low levels of physical activity in people with COPD at all points in the disease course highlights the need for interventions to increase physical activity participation by people with COPD. The widely‐accepted benefits of physical activity, coupled with the increasing availability of wearable monitoring devices to objectively measure participation, has led to a dramatic rise in the number and variety of studies that aim to improve physical activity levels in people with COPD. However, little is known about the range of interventions tested so far, partly attributable to the complexities of data analysis and the challenge of rapidly evolving technology, and the relationship between effects on physical activity and other outcomes including exercise capacity and health‐related quality of life. This Cochrane Review aims to evaluate the efficacy of existing interventions to increase physical activity in people with COPD, and to signpost directions for future work.

Objectives

In people with COPD, which interventions are effective at improving objectively‐assessed physical activity?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We include randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of any intervention where objectively‐assessed physical activity or sedentary behaviour was a measured outcome in people with COPD, as previous consensus statements (Watz 2014a) and systematic reviews (Dhillon 2015; Gimeno‐Santos 2011) have failed to identify subjective tools that accurately reflect this in people with COPD.

We include studies reported as full‐text articles, those published as abstract only and unpublished data. Physical activity could be either a primary or a secondary outcome of the study. We include cross‐over trials where pre‐cross‐over data were available from study authors.

Types of participants

We include adults (18 years of age and over) with a diagnosis of COPD according to established criteria, regardless of disease severity. We planned to include studies that incorporated a mix of diagnostic groups, only if we could obtain data on any of the review outcomes separately for people with COPD.

Types of interventions

We include trials that objectively assessed physical activity as an outcome. These trials compared an intervention versus no intervention or a sham/placebo intervention, compared an intervention in addition to another standard intervention common to both groups or to a different intervention. Interventions could be supervised or unsupervised. Interventions could include, but were not limited to, physical activity counselling, education programmes and self‐management strategies. Studies including exercise training undertaken as a stand‐alone intervention or as part of a comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation programme incorporating other components targeting chronic disease self‐management (Hill 2013) were considered together. We analysed studies that included pulmonary rehabilitation (as defined by authors) separately from studies that did not include pulmonary rehabilitation. We also included studies in which both groups received pulmonary rehabilitation and which assessed the inclusion of an additional specific physical activity intervention in one group.

Comparisons

One or more interventions versus no intervention

One or more interventions versus sham/placebo intervention

One or more interventions in addition to a standard intervention common to both groups

One or more interventions versus a different intervention

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Studies had to include variable(s) that reflected participation in physical activity or sedentary behaviour, as measured objectively using a pedometer, accelerometer or activity monitor. Outcomes of interest included but were not limited to step count, activity counts, energy expenditure and physical activity time (different intensities, range of thresholds used). Primary time points were at baseline (prior to start) and at the time of intervention completion; we used change in physical activity from baseline for analysis where possible. We also categorised any follow‐up measurements reported following intervention completion as either short‐term (within one month), medium‐term (between one and six months) or long‐term (longer than six months). We sought raw data from the study authors where possible to facilitate comparisons.

Secondary outcomes

Health‐related quality of life (measured using either a generic or disease‐specific tool)

Exercise capacity: measured using a laboratory or field exercise test, e.g. cardiopulmonary exercise test, six‐minute walk test (6MWT)

Adverse events, e.g. musculoskeletal injury

Adherence to intervention

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified studies from the Cochrane Airways Trials Register, which is maintained by the Information Specialist for the Group. The Cochrane Airways Trials Register contains studies identified from several sources:

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), through the Cochrane Register of Studies Online (crso.cochrane.org);

Weekly searches of MEDLINE Ovid SP 1946 to June 2019;

Weekly searches of Embase Ovid SP 1974 to June 2019;

Monthly searches of PsycINFO Ovid SP 1967 to June 2019;

Monthly searches of Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL EBSCO), 1937 to June 2019;

Monthly searches of Allied and Complementary Medicine (AMED EBSCO), all years to June 2019;

Handsearches of the proceedings of major respiratory conferences.

Studies contained in the Trials Register are identified through search strategies based on the scope of Cochrane Airways. Details of these strategies, as well as a list of handsearched conference proceedings, are in Appendix 1. See Appendix 2 and Appendix 3 for search terms used to identify studies for this review.

We also searched Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro), www.clinicaltrials.gov, the WHO ICTRP portal (www.who.int/ictrp/en/) and the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au/). We searched all databases from their inception to June 2019, and imposed no restriction on language of publication.

Searching other resources

We checked reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references. We searched relevant manufacturers' websites for trial information.

We searched for errata or retractions from included studies published in full text on PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) on 12 July 2019.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (AB and NC) independently screened titles and abstracts for inclusion of all the potentially eligible studies we identified from the search, and coded them as either 'retrieve' (eligible or potentially eligible/unclear) or 'do not retrieve'. We retrieved the full‐text study reports/publications and two review authors (AB and NC) independently screened the full‐text articles and identified studies for inclusion, recording reasons for exclusion of the ineligible studies. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third review author (AH). We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study rather than each report was the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram and Characteristics of excluded studies tables (Moher 2009).

Data extraction and management

We used a data collection form that was piloted on at least one study included in the review, to record study characteristics and outcome data. Two review authors (AB and NC) independently extracted the following study characteristics from included studies:

Methods: study design, duration of study, study locations, study setting, date of study;

Participants: number, mean age, age range, gender, severity of condition, diagnostic criteria, baseline lung function, smoking history, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, withdrawals;

Interventions: intervention, comparison, concomitant interventions;

Measurement tool;

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected (at baseline and at the time of intervention completion) and follow‐up measurements at any other time points noted;

Notes: funding for trial, declared conflicts of interest by trial authors.

We resolved disagreements by reaching consensus, or by involving a third review author (AH or MA). We noted in the Characteristics of included studies table if the included studies did not report outcome data in a useable way. We contacted study authors to verify extracted data when necessary and we provided details of missing data when possible. One review author (AB) transferred data into the Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) file (Review Manager 2014). We double‐checked that the review author had entered data correctly by comparing data presented in the systematic review with data provided in the study reports. A second review author (NC) spot‐checked study characteristics for accuracy against the trial report.

Where meta‐analyses of physical activity outcome were possible, we included figures in the review.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (AB and NC) independently assessed risks of bias for each included RCT, using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017). We resolved disagreements by discussion or by involving another review author (AH or MA). Where conflicts of interest were present, an independent co‐author conducted the assessment. We assessed risks of bias according to the following domains:

Random sequence generation;

Allocation concealment;

Blinding of participants and personnel;

Blinding of outcome assessment;

Incomplete outcome data;

Selective outcome reporting;

Other potential bias.

For the 'blinding of outcome assessment' domain, we rated both primary and secondary outcomes as ‘objective’ for objectively‐measured outcomes and ‘other’ for those outcomes with greater potential to be affected by lack of blinding (e.g. quality of life questionnaires).

We graded each potential source of bias as either high, low or unclear, and provided an extract from the study report together with a justification for our judgement. We resolved discrepancies by consensus. We summarised the 'Risk of bias' judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed and summarised results in a ’Risk of bias' table. When considering treatment effects, we took into account the risks of bias for studies that contributed to this outcome.

Assessment of bias in conducting the systematic review

We conducted the review according to this published protocol and have reported any deviations from it in the Differences between protocol and review section of the review.

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed all the data reported for each outcome, irrespective of dropout rate or use of intention‐to‐treat analysis.

We undertook meta‐analyses only when this was meaningful, i.e. if treatments, participants and the underlying clinical question were similar enough for pooling to make clinical sense.

We intended to analyse dichotomous data as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) but no data were available. For continuous data we calculated mean differences (MDs: same metric scale). To retain the units of measurement, we did not express any data as standardised mean differences (SMDs: different metric scales) with 95% CIs. We narratively described skewed data reported as medians and interquartile ranges.

Where multiple arms were reported in a single trial, we included only the relevant arms. We had intended to halve the control group to avoid double‐counting in the event that we combined two comparisons (e.g. drug A versus placebo and drug B versus placebo) in the same meta‐analysis, but this approach was not required.

Unit of analysis issues

Where studies randomly allocated individual participants to study groups, we considered the participant as the unit of analysis. We only included cross‐over trials where data were available prior to cross‐over, due to the potential carry‐over effects of behavioural interventions. We had intended to consider the cluster as the unit of analysis for cluster‐randomised studies, but this approach was not required.

Dealing with missing data

In the event of missing data, we contacted investigators or study sponsors to verify key study characteristics and to obtain missing numerical outcome data when possible, e.g. when a study was reported only as an abstract. If this was not possible, we had intended to analyse the impact of including studies with missing data that may be related to the intervention by performing a sensitivity analysis, but this approach was not required.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I2 statistic to measure heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis. Where we identified it, we considered statistical heterogeneity to be substantial if I2 was greater than 50% (Deeks 2017), and explored possible causes using prespecified subgroup analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

We had intended to create a funnel plot to explore possible small‐study and publication biases if we could pool more than 10 included trials, but this was not possible.

Data synthesis

We performed a pooled quantitative synthesis where the trials were clinically homogeneous. We pooled data using a random‐effects model to incorporate between‐study heterogeneity into the meta‐analysis. Where the trials were clinically heterogeneous, we performed a narrative synthesis. For instance, we analysed data for different types of interventions separately, and data for studies starting in the period following acute exacerbation separately from those in stable disease.

'Summary of findings' table

We created 'Summary of findings' tables using the following outcomes:

time spent in moderate or moderate‐to‐vigorous physical activity at end intervention in participants with clinically‐stable COPD.

We used the five Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of a body of evidence as it related to studies that contributed data to the meta‐analyses for prespecified outcomes. We used methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 (Higgins 2017) and Chapter 12 (Schünemann 2017) of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, and we used the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool software (GRADEpro GDT 2014). We justified all decisions to downgrade or upgrade the quality of the evidence using footnotes, and we provide comments to aid the reader's understanding of the review where necessary. We did not include data from studies published only in abstract form or on clinical trial registries, due to inadequate assessment of risks of bias.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform the following subgroup analyses.

Duration of intervention (≤ 3 months versus > 3 months);

Supervision of intervention (yes or no);

Disease severity (mild disease, defined as forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) % predicted ≥ 80%, forced expiratory ratio (FER) < 0.7, compared with other classifications).

We used physical activity as the outcome for subgroup analyses.

We used the formal test for subgroup interactions in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) (Review Manager 2014).

Sensitivity analysis

We examined the effects of methodological quality on the pooled estimate by removing studies that were at high or unclear risk of bias for the domains of blinding and incomplete outcome data. We had also intended to examine the effects of measurement device on the pooled estimate by removing studies that used pedometers, as previous studies suggest that these might be less accurate in detecting steps in people with COPD (Pitta 2006b).

Results

Description of studies

Details are available in the Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Results of the search

The search yielded 3233 citations and ended with 76 studies included from 179 citations. These included 12 abstracts (see Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Eighty‐four studies are currently underway and pending study completion/publication (see Ongoing studies).

Included studies

Of the 76 studies included, 24 studies compared an intervention to promote physical activity versus no intervention (comparison 1). These included pulmonary rehabilitation/exercise training (Borges 2014; De Roos 2017; Egan 2010; Louvaris 2016, Tahirah 2015; Tsai 2016; Vasilopoulou 2017; Wootton 2017), physical activity counselling (Altenburg 2015; Arbillaga‐Etxarri 2018; Demeyer 2017; Hornikx 2015; Hospes 2009; Orme 2018; Priori 2017; Saini 2017; Wootton 2017), self‐management (Jolly 2018; Kanabar 2015; Mitchell 2013; Tabak 2014b), nutritional supplementation (Goris 2003), gait aid (Ng 2015) and endobronchial valve surgery (Hartman 2016).

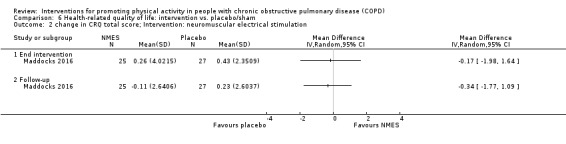

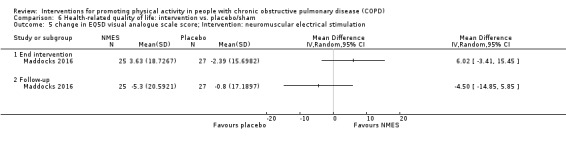

There were 10 studies that compared an intervention to promote physical activity to sham/placebo (comparison 2). These included self‐management (Schuz 2015), pharmaceutical interventions (Beeh 2014;Magnussen 2017;NCT00144326; Watz 2016;Watz 2017), nutritional supplementation (Dal Negro 2012), supplemental oxygen (Sandland 2008), singing (Lord 2012) and neuromuscular electrical stimulation (Maddocks 2016).

There were 31 studies that compared an intervention to promote physical activity in addition to an intervention common to both groups (comparison 3). These included pulmonary rehabilitation/exercise training (Breyer 2010; Effing 2011; Larson 2014; Troosters 2018; Varas 2018), physical activity counselling (Altenburg 2015; Bender 2016; Cruz 2016; De Blok 2006; Kawagoshi 2015; Loeckx 2018; Mantoani 2018; Mendoza 2015; Moy 2015a; Nguyen 2009; Nolan 2017; Orme 2018; Singh 1998; Tabak 2014a; Vorrink 2016; Wan 2017), self‐management (Benzo 2016; Larson 2014), pharmaceutical interventions (Curtis 2016; Troosters 2014; Troosters 2018), nutritional supplementation (Ogasawara 2018; Van de Bool 2017) supplemental oxygen (Alison 2019), non‐invasive ventilation (Duiverman 2008) and inspiratory muscle training (Charususin 2018).

Sixteen studies compared two interventions to increase physical activity with each other (comparison 4). These studies included alternative models of or alternatives to pulmonary rehabilitation/exercise training (Chaplin 2017; Felcar 2018; Gamper 2019; Holland 2017; O'Neill 2018; Polkey 2018; Probst 2011; Rinaldo 2017; Sena 2013; Steele 2019; Vasilopoulou 2017; Widyastuti 2018), self‐management (Blumenthal 2014), pharmaceutical interventions (Nakamura 2016; NCT01351792) and a lightweight cylinder for supplemental oxygen (Casaburi 2012).

Of studies with more than two groups, four contributed to more than one comparison (Altenburg 2015; Larson 2014; Orme 2018; Vasilopoulou 2017).

The total number of participants involved in the included studies was 8018. The sample sizes ranged from eight participants (Nguyen 2009; Priori 2017; Sena 2013) to 289 participants (Jolly 2018). The mean age of participants was 66 years and mean FEV1 54% predicted. On average, groups comprised 63% men, but details relating to the sex of participants were not reported in four abstracts (Egan 2010; Nakamura 2016; Priori 2017; Sena 2013), three papers (Larson 2014; Lord 2012; Polkey 2018) and two clinical trial registries (NCT00144326; NCT01351792). Interventions were provided in person and by telephone call, smart phone app, website, device or printed information. Study duration ranged from one day (surgical procedure) to 12 months, with follow‐up provided in 11 studies (ranging from seven days to 12 months post‐intervention). Three studies assessed interventions provided during inpatient admissions for acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD) and five studies in the post‐admission phase. Of the 76 studies included, 38 had assessed physical activity as a primary outcome. Details are available in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Excluded studies

We excluded most of these 134 studies (n = 84) due to physical activity not being objectively assessed. We report reasons for exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, the domains with the highest risks of bias were performance bias, as the method of delivery of some interventions precluded participant blinding, and reporting bias. Domains with the lowest risks of bias were detection bias, as objective assessment of physical activity was an inclusion criterion, and selection bias, as most studies did report the method of random sequence generation (Figure 2).

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

For random sequence generation, 48 studies had a low risk of bias. Insufficient information was available to inform a decision for 17 studies (Bender 2016; Burtin 2015; Casaburi 2012; De Blok 2006; Gamper 2019; Hartman 2016; Hornikx 2015; Hospes 2009; Kawagoshi 2015; Magnussen 2017; Orme 2018; Polkey 2018; Probst 2011; Sandland 2008; Troosters 2014; Watz 2017; Widyastuti 2018), nine abstracts (Egan 2010; Kanabar 2015; Loeckx 2018; Mantoani 2018; Nakamura 2016; Ng 2015; Priori 2017; Saini 2017; Singh 1998) and studies from two clinical trial registries (NCT00144326; NCT01351792).

For allocation concealment, one study was assessed at high risk of bias (Altenburg 2015) and 28 at low risk of bias. Insufficient information was available to inform a decision in 36 studies (Beeh 2014; Bender 2016; Benzo 2016; Blumenthal 2014; Breyer 2010; Casaburi 2012; Curtis 2016; De Blok 2006; Duiverman 2008; Effing 2011; Gamper 2019; Goris 2003; Hartman 2016; Hornikx 2015; Hospes 2009; Kawagoshi 2015; Larson 2014; Magnussen 2017; Mendoza 2015; Moy 2015a; Nolan 2017; Ogasawara 2018; Orme 2018; Polkey 2018; Probst 2011; Rinaldo 2017; Sandland 2008; Steele 2019; Troosters 2014; Tsai 2016; Varas 2018; Vasilopoulou 2017; Vorrink 2016; Watz 2016; Watz 2017; Widyastuti 2018), nine abstracts (Egan 2010; Kanabar 2015; Loeckx 2018; Mantoani 2018; Nakamura 2016; Ng 2015; Priori 2017; Saini 2017; Singh 1998) and studies from two clinical trial registries (NCT00144326; NCT01351792).

Blinding

We assessed performance bias separately for participants and personnel.

Participants