Abstract

-

»

Osseointegrated prostheses provide a rehabilitation option for amputees offering greater mobility, better satisfaction, and higher use than traditional socket prostheses.

-

»

There are several different osseointegrated implant designs, surgical techniques, and rehabilitation protocols with their own strengths and limitations.

-

»

The 2 most prominent risks, infection and periprosthetic fracture, do not seem unacceptably frequent or insurmountable. Proximal amputations or situations leading to reduced mobility are exceptionally infrequent.

-

»

Osseointegrated implants can be attached to advanced sensory and motor prostheses.

In 2005, there were approximately 1.6 million amputees in the United States, a prevalence of almost 1 in 200 people, and that number is expected to double by 20501. The global amputee census is difficult to establish2, but estimates have suggested that worldwide there is a lower-extremity amputation performed every 30 seconds for a patient with diabetes3. The current accepted standard for rehabilitation and mobility following amputation is a socket-mounted prosthesis. Unfortunately, problems are common. Up to three-quarters of patients undergoing a lower-extremity amputation experience skin ulcers or intolerable perspiration4, require frequent refitting5, or have prosthesis-fit issues due to residuum size fluctuation6; approximately 7% sustain a fracture in the residual limb7; and the majority have reported that they lack confidence with mobility8.

Osseointegration surgery of the appendicular skeleton for reconstruction in amputees is defined as a procedure in which a metal implant is directly anchored to the residual bone, which is then attached to a prosthetic limb using a transcutaneous connector through a small opening in the skin. This technique has gradually gained greater acceptance in the almost 30 years since the first osseointegration surgical procedure was performed in Sweden on May 15, 1990. On that date, a patient who had undergone bilateral traumatic transfemoral amputations a decade earlier had the first-stage titanium implant anchored to 1 of the femora9. This implant technology was based on the work of Per-Ingvar Brånemark, who first discovered that rabbit bone became strongly bound and inextricably linked with titanium implants, leading to him coining the term osseointegration and using titanium for human dental implants as early as 196510. Dental implant technology has shown successful outcomes with screw fixation devices because of the small size of the bone, the high vascularity of the jaw, substantial support by the surrounding teeth minimizing torsional forces that can lead to early loosening, and the dental implants experiencing mostly axial compression forces11. Joint replacement has shown success with press-fit implants that provide a high surface area of integration and substantial porosity and rely on maximum contact with inherent geometric features of the implant to provide rotational stability12. The principles of osseointegration for amputees are more comparable with the principles of arthroplasty than those of dentistry13. For clarity, the remainder of this article will use the term “osseointegration” to refer specifically to direct metal-to-bone anchorage in the appendicular skeleton as a means to reconstruct amputated limbs or digits.

Osseointegration surgery using titanium implants directly attached to bone was successful from the start. The initial efforts to cement transcutaneous implants into bone, by Dr. Vert Mooney and other surgeons at Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center in Los Angeles in 1977, resulted in uniform loosening and infection, requiring early removal14, as did other earlier experiments15. The Brånemark technique is instead able to achieve intimate bone-titanium contact, and preliminary results were so encouraging that clinical trials soon expanded to patients who underwent upper-extremity amputation16. This demanding procedure requires meticulous attention to detail and skillfully merges hard-tissue and materials science principles from both dental and orthopaedic surgery, together with soft-tissue handling techniques more familiar to plastic surgeons. Perhaps due in part to this, only approximately 400 patients have been treated using this technique17.

Inspired by these preliminary outcomes, and with the goal of vastly increasing clinician adoption and patient access to this transformative prosthetic solution, Munjed Al Muderis began osseointegration with a different implant design, improved operative techniques, and accelerated rehabilitation strategies in 2009. Their goal was to make this technology more readily applicable for use by a wider community of surgeons, adhering to principles familiar to arthroplasty and reconstruction surgeons18. With the recent approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for osseointegration to be used in situations of humanitarian exemption19, and with the current FDA clinical trial spearheaded by the U.S. Department of Defense (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03720171), global interest in osseointegration for amputees is expected to increase dramatically in the coming years.

The purposes of this article were to introduce and describe the current osseointegration implant designs, to identify key variations of surgical and rehabilitation concepts, to briefly summarize the salient benefits of and residual concerns with regard to osseointegration, and to forecast where osseointegration may be headed in the near future. In this article, we will focus attention on lower-extremity (transfemoral and transtibial) osseointegration, as it represents the overwhelming majority of current and immediate future surgical procedures in the United States1 and around the world20-23.

Currently Active Osseointegration Implant Systems

The currently active osseointegration implant systems are shown in Table I and are discussed individually below.

TABLE I.

Comparison of Osseointegration Implant Systems

| OPRA | ILP | OPL | Compress | POP | ITAP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | Titanium | Cobalt-chromium-molybdenum | Titanium | Titanium | Titanium | Titanium |

| Retention | Threaded | Press-fit | Press-fit | Cross-pin | Press-fit | Press-fit |

| Anatomic suitability | Long bones, digits | Long bones | Long bones, pelvis | Humerus, femur | Femur | Humerus, femur |

| Bone-implant interface | Laser-etched | Czech hedgehog 1.5 mm | Plasma-sprayed up to 0.5 mm | Porous-coated, axial compression | Porous-coated | Hydroxyapatite |

| Skin-implant interface | Polished | Polished | Polished | Polished | Polished | Hydroxyapatite |

| Surgical stages | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Months from implantation to full weight | 3 to 18 | 2 to 3 | 2 to 3 | Unspecified | Unspecified | Unspecified |

The Osseointegrated Prostheses for the Rehabilitation of Amputees (OPRA) (Integrum) has evolved from the first osseointegration surgical procedure in 1990 under the direction of Rickard Brånemark24. The OPRA has principally been implanted into patients with transfemoral amputations, with smaller numbers of transhumeral, transradial, finger or thumb, and transtibial amputations. The OPRA is detailed in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

The OPRA. The cannulated titanium alloy implant is secured to the skeleton by using a threading tool to cut spiral groove threads in the intramedullary cortex of the residual bone and then screwing in the implant. The external threading of the OPRA is laser-etched to promote osseous ongrowth. The typical OPRA consists of a threaded bone implant that is coupled to a transcutaneous abutment and an abutment screw to interface with the appropriate external prosthesis for the patient. Immediate retention is achieved by screw thread interdigitation with bone. Fig. 1-A Schematic of the OPRA. (Reproduced, with modification, from: Cecilia Berlin, PhD, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden. Adapted version of an illustration by Cecilia Berlin, originally published in Tillander et al., 2017, p. 3102. Illustration licensed under Creative Commons BY 4.0. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) Fig. 1-B Radiographic depiction during stage-1 implantation. (Reproduced, with permission, from: Stenlund P, Trobos M, Lasumaa J, Brånemark R, Thomsen P, Palmquist A. Effect of load on the bone around bone-anchored amputation prostheses. J Orthop Res. 2017 May;35[5]:1113-22. Epub 2016 Jul 4. © 2016 Orthopaedic Research Society. Published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc.) Fig. 1-C Radiographic depiction after placement of the transcutaneous abutment. (Reproduced, with permission, from: Stenlund P, Trobos M, Lasumaa J, Brånemark R, Thomsen P, Palmquist A. Effect of load on the bone around bone-anchored amputation prostheses. J Orthop Res. 2017 May;35[5]:1113-22. Epub 2016 Jul 4. © 2016 Orthopaedic Research Society. Published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc.)

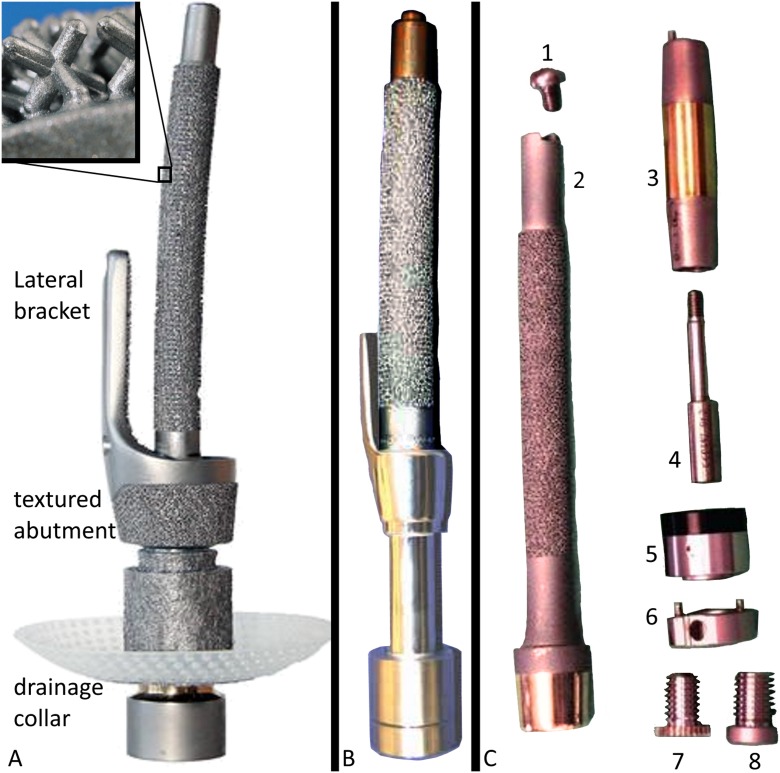

The Integral Leg Prosthesis (ILP) (Orthodynamics) evolved from the Endo-Exo implant (ESKA Orthopaedic Handels), which was introduced by Hans Grundei in Germany. The Endo-Exo and ILP are detailed in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Endo-Exo prosthesis (Figs. 2-A and 2-B) and ILP (Fig. 2-C). All iterations of this implant are made of cobalt-chromium-molybdenum, with an intramedullary nail-type stem featuring onlaid 1.5-mm Czech hedgehogs (a 3-dimensional plus sign, featured in Fig. 2-A) to promote bone ingrowth. All models achieve immediate implant retention via the press-fit implantation, analogous to hip arthroplasty, and the external prosthetic limb is mounted via a multicomponent dual cone and screw system. Fig. 2-A The original version of this device featured a distal collar that was porous-coated to promote skin adhesion and a lateral stabilizing bracket to fit over the external bone surface to enhance torsional stability. Early failures were attributed to this bracket and the rough collar, which prompted modifications. (Adapted, by permission, from Springer Nature: Springer Nature, Sports Engineering. Direct skeletal attachment prosthesis for the amputee athlete: the unknown potential. Al Muderis M, Aschoff HH, Bosley B, Raz G, Gerdesmeyer L, Burkett B. Sports Engineering. 2016 Sep;19[3]:141-5. Copyright 2016. The zoom-in box of ILP texture in Fig. 2-A is adapted, by permission, from Springer Nature: Springer Nature, Der Orthopäde. Juhnke DL, Aschoff HH. Endo-Exo-Prothesen nach Gliedmaßenamputation. Der Orthopäde. 2015 Jun; 44[6]:419-25. Epub 2015 May 14. Copyright 2015.) Fig. 2-B A revised version retained the bracket but polished the collar. (Adapted with permission from: Kennon RE. A transcutaneous intramedullary attachment for AKA prostheses. Reconstructive Rev. 2013 Mar;3[1]:49-51. Licensed under Creative Commons BY 4.0. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) Fig. 2-C The next version, renamed ILP, removed the bracket and coated the collar with titanium niobium oxynitride ceramic to prevent skin adherence. Note that osseointegration is only designed to occur at the textured surface approximately 1.5 cm proximal to the abutment, not on the smooth surface between the abutment and the textured surface. 1, proximal cap screw; 2, ILP body with main portion textured, distal flare untextured, abutment highly polished with titanium niobium oxynitride ceramic surface; 3, dual cone abutment adapter; 4, safety screw; 5, taper sleeve; 6, distal bushing; 7, permanent locking propeller screw; and 8, temporary cover screw. (Adapted by permission from Springer Nature: Springer Nature, Operative Orthopädie und Traumatologie. Aschoff HH, Clausen A, Tsoumpris K, Hoffmeister T. Implantation der Endo-Exo-Femurprothese zur Verbesserung der Mobilität amputierter Patienten. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2011 Dec;23[5]:462-72. German.)

The Osseointegrated Prosthetic Limb (OPL) (Permedica Manufacturing) evolved from the experience with the ILP. Al Muderis began designing the OPL in 2010, and it became commercially available in 201425. For all 3 types, immediate implant retention is achieved through press-fit interdigitation25. The OPL is detailed in Figure 3.

Fig. 3.

OPL. Three models exist, labeled A, B, and C. The OPL is a forged titanium alloy, stem-shaped implant whose surfaces have a plasma-sprayed coating, up to 0.5 mm thick, to promote bone ingrowth and rapid integration. The external portions of the collars are treated with titanium niobium oxynitride ceramic to promote smooth soft-tissue gliding, limiting the probability of symptomatic soft-tissue adhesion and tethering. Proximal fluted fins provide initial rotational stability, akin to a Wagner-style hip arthroplasty stem. Fig. 3-A OPL types A, B, and C with matching dual cone abutment adapters. Type A has a flat abutment with a relatively long smooth collar and a proximal tail that is tapered to accept an extension nail or an arthroplasty attachment, when indicated. Type B has a conical abutment that embeds into the distal bone with a smaller, smooth extraosseous collar; these also possess the tapered tail adapter, identical to Type A. Type C features the same abutment and collar style as Type B but the body is shorter, and instead of a tapered tail adapter, there is a 135° hole bored near the proximal tail to accept a femoral neck screw, which can prophylactically be used to prevent femoral neck fractures. This type is most suitable for short femoral residua. All models use a similar dual cone connection mechanism to the external prosthetic limb. All models’ dual cone adapter features titanium niobium oxynitride ceramic at the portion exposed to the skin to prevent skin adhesion. Fig. 3-B Exploded view of a Type-A implant, with the components arranged at approximately the proximal-distal levels in which they would be once assembled and implanted in a patient who had undergone a femoral amputation. 1, proximal cap screw; 2, OPL body; 3, safety screw; 4, dual cone abutment adapter; 5, permanent locking propeller screw; 6, proximal connector; and 7, prosthetic connector. Fig. 3-C Radiograph of OPL Type A in a patient who had undergone a femoral amputation.

A percutaneous osseointegrated prosthesis (POP) (DJO Global) is still currently in the development phase26 and is detailed in Figure 4.

Fig. 4.

Photograph of a POP. Manufactured from a titanium alloy, its shape is tubular and solid and retains features in common with a hip arthroplasty stem with a plasma-sprayed coating. Osseointegration occurs over a few centimeters near the abutment; the remainder of the proximal aspect of the implant is for alignment only. The goal of this limited integration, analogous to uncemented total hip implants that integrate mainly at the proximal femoral metaphyseal flare, is to avoid stress-shielding. The abutment is smooth niobium oxide, with the goal of inhibiting skin adhesion to the implant. Attachment to the external implant features a dual cone adapter, and immediate implant retention is achieved through press-fit implantation. (Reproduced, with modification, from: Allyn G, Bloebaum RD, Epperson RT, Nielsen MB, Dodd KA, Williams DL. Ability of a wash regimen to remove biofilm from the exposed surface of materials used in osseointegrated implants. J Orthop Res. 2019 Jan;37[1]:248-57. Epub 2018 Nov 19. This article is a U.S. Government work and is in the public domain in the USA.)

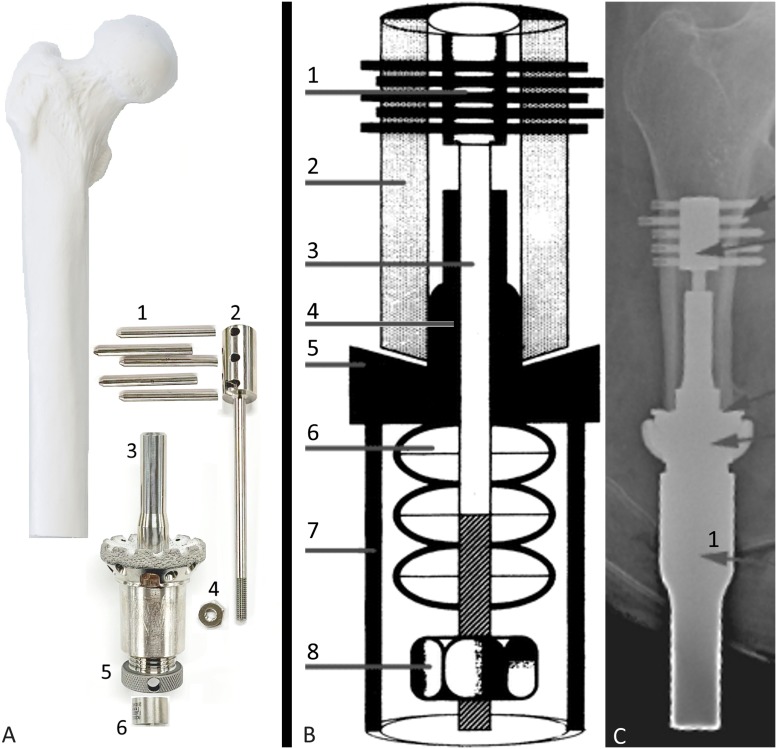

The Compress Device (Zimmer Biomet) was originally designed as a solution for large-gap limb salvage for patients with bone tumors, for which it is still used, and has since been modified to become a transcutaneous implant system. This device features a porous-coated titanium abutment with a narrow minimally contacting intramedullary shaft, anchoring the implant to bone by transverse cross-pins. Spring forces inherent in this design, both static and dynamic, promote bone remodeling continuously even when patients are not weight-bearing27,28. The Compress Device is detailed in Figure 5.

Fig. 5.

Compress Device. The distinguishing feature of this device compared with the others is that the cross-pin design allows a screw-and-nut apparatus to transmit force from a Belleville spring-style washer system directly to the end of the residual bone, resulting in a compressive force, for which the product is named. The abutment is polished at the skin interface, and connection to a prosthetic limb is achieved with a customized attachment. Immediate implant retention is achieved via the unique spring and cross-pin mechanism. The main difference between the tumor endoprosthesis currently commercially available and the transcutaneous osseointegrated implant configuration under trial is the addition of a transcutaneous taper sleeve (intellectual property not available to be shown in photography). Fig. 5-A Exploded schematic of the device, with the components arranged at approximately the proximal-distal levels in which they would be once assembled and implanted in a patient who had undergone a femoral amputation. 1, transverse retention pins; 2, anchor plug; 3, spindle with hydroxyapatite coating at bone interface; 4, Compress nut; 5, temporary compression cap before nut placement; and 6, centering sleeve to position the anchor plug in the center of the medullary canal. (Reprinted with permission from Zimmer Biomet.) Fig. 5-B Illustrated cross-sectional schematic of the device showing approximate in situ component positions. 1, transverse retention pins; 2, bone; 3, anchor plug; 4, centering sleeve; 5, spindle; 6, Belleville washers; 7, taper; and 8, Compress nut. (Adapted by permission from Springer Nature: Springer Nature, International Orthopaedics. Compressive osseointegration promotes viable bone at the endoprosthetic interface: retrieval study of Compress® implants. Kramer MJ, Tanner BJ, Horvai AE, O’Donnell RJ. Int Orthop. 2008 Oct;32[5]:567-71. Copyright 2008.) Fig. 5-C Radiograph of Compress Device in a patient with a femoral amputation. Arrow 1 identifies the transcutaneous taper sleeve. (Adapted, by permission, from Springer Nature: Springer Nature, Der Unfallchirurg. The Compress® transcutaneous implant for rehabilitation following limb amputation. McGough RL, Goodman MA, Randall RL, Forsberg JA, Potter BK, Lindsey B. Der Unfallchirurg. 2017 Apr;120[4]:300-5. Copyright 2017.)

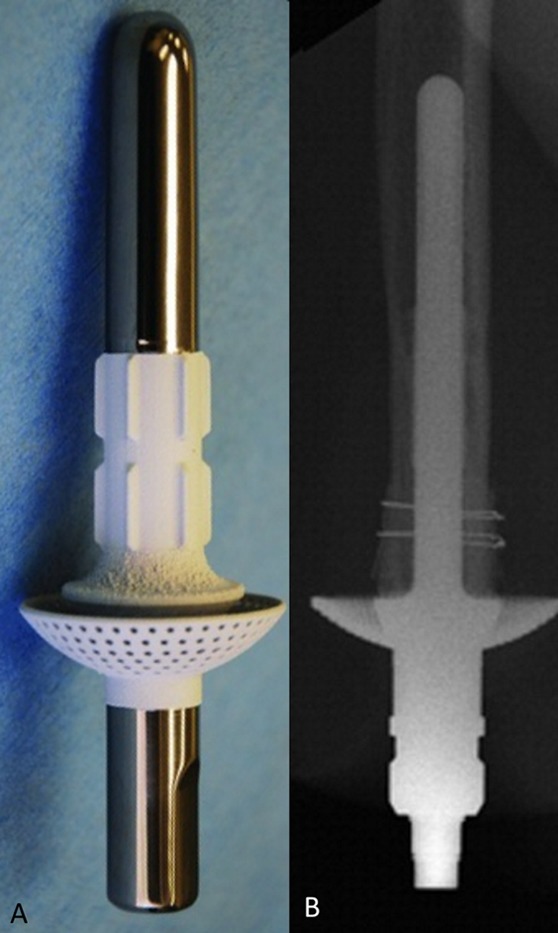

The Intraosseous Transcutaneous Amputation Prosthesis (ITAP) (Stryker Orthopaedics) is a device that recently completed its clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02491424) but will not be released. Its main goal was to replicate the skin-implant interface that is seen with animal antlers, a biologic example of a hard tissue protruding through skin while resisting infection. Although animal trials were promising29, human trials led to problems with the hydroxyapatite interface breaking down, leading to implant failure and infection. The ITAP is detailed in Figure 6.

Fig. 6.

ITAP. The implant features a titanium intramedullary stem and a large expansile flanged cap that is coated with hydroxyapatite. The goal of the distal coating was to promote skin adhesion, with the aim of achieving a complete seal against bacterial infiltration. Fig. 6-A The model used in a canine study before the human clinical trial. Note the proximal polished surface with hydroxyapatite coating of the distal portion. (Reproduced from: Fitzpatrick N, Smith TJ, Pendegrass CJ, Yeadon R, Ring M, Goodship AE, Blunn GW. Intraosseous Transcutaneous Amputation Prosthesis [ITAP] for limb salvage in 4 dogs. Vet Surg. 2011 Dec;40[8]:909-25. Epub 2011 Nov 4. © Copyright 2011 by The American College of Veterinary Surgeons. Reproduced with permission.) Fig. 6-B Radiographic view of ITAP in a patient with a humeral amputation. (Reprinted from: J Hand Surg. 35[7], Kang NV, Pendegrass C, Marks L, Blunn G. Osseocutaneous integration of an Intraosseous Transcutaneous Amputation Prosthesis implant used for reconstruction of a transhumeral amputee: case report, 1130-4, 2010. Copyright 2010, with permission from Elsevier.)

Major Surgical and Rehabilitation Principles

The OPRA is the oldest extant osseointegration implant, and has been developed over 3 decades with continuous clinical use and research development. Of all osseointegration techniques, the OPRA has the longest patient follow-up data available30. The OPRA technique9 is characterized by 2 surgical events per bone, spaced 6 months apart. The goal of the first procedure is to implant the threaded intramedullary bone anchor. In brief, this is achieved by gently reaming the canal and then tapping the thread for the implant to later be screwed into position at least 20 mm deep, beyond the distal bone edge, as a buffer against potential bone resorption. After inserting the implant, the incision is then fully closed. If inadequate bone graft is harvested during the reaming, iliac crest bone can be auto-transplanted to plug the distal end below the fixture. Either the extremity remains non-weight-bearing, or patients may continue to walk in a traditional socket, to avoid bone loading during the initial osseointegration. Following an interval of 6 months to allow the implant to integrate with the host bone, the second surgical event is undertaken. This features the attachment of an abutment to the implanted fixture, the externalization of the abutment through the skin, and additional soft-tissue procedures to create a stoma at the skin-implant interface. The points of emphasis with this protocol include eliminating hair follicles surrounding the implant to reduce this potential source of infection and tightly securing soft tissue to limit movement, which can cause inflammation and provoke infection. Muscle endings should be sutured to the periosteum within 10 mm of the distal bone end, and the subcutaneous fat should be excised to promote skin adhesion directly to bone. The patient is then limited to non-weight-bearing, range-of-motion exercises for 10 to 12 days to promote soft-tissue healing. The routine postoperative protocol is detailed31 but may be summarized as non-weight-bearing for approximately 1 month following the second stage, with progressive weight-bearing limited to a few hours daily featuring a short training prosthesis attachment and increasing the amount of weight loaded through the prosthesis and the hours of weight-bearing each day through the initial 3 months. By month 4, patients are encouraged to increase prosthetic wear time and to then graduate to independent walking without crutches and full weight-bearing, possibly without a time limitation, by month 6. For patients with suboptimal bone quality, the recommended time to each milestone may be doubled. Approximately 400 OPRA have been implanted so far17.

The ILP was developed by Hans Grundei for 2-stage implantation. The first stage is implant placement via sequential broaching (without reaming) and insertion of the implant using a press-fit technique and a temporary plug inserted into the distal end of the implant. The wound is fully closed, and, 4 to 6 weeks later, a circular corer is used to open the skin over the abutment to create a stoma. The implant plug is then removed, and a dual cone adapter is inserted percutaneously. The rehabilitation protocol involves activity progression as tolerated, and permanent prosthetic limbs usually are attached within the first few weeks thereafter32.

The OPL was designed for single-stage implantation by Al Muderis, the first implant available specifically with this intent, and there have already been >800 implantations of the OPL worldwide33. For patients with prohibitively short residual bone (less than approximately 8 cm), lengthening of the residuum using an externally powered intramedullary magnetic telescopic nail can be performed34-36. Following a period of bone consolidation after attaining the desired length, routine osseointegration ensues. Using a guillotine or other incision as is best suited to address any existing skin compromise, first the distal bone end is prepared. This may include heterotopic ossification removal or resection and face reaming to a uniform surface using a calcar reamer. Flat reaming fits OPL type A implants and conical reaming fits OPL type B and C implants. The developing surgeon recommends tight purse-string cerclage closure of the muscular envelope around the bone-implant interface; there is no suturing to bone. Canal preparation is then performed using sequential flexible reamers, followed by sequential implant-specific broaches. Press-fit implantation is then performed until the collar solidly abuts the distal part of the femur. Further modification of the circumferential myodesis is performed, tightening the muscle so that it is directly apposed to both implant and bone. The subcutaneous tissue is then defatted, and the skin is secured to adjacent muscle before tightly closing the amputation incision. Finally, the circular coring device is used to create a stoma and to percutaneously insert the dual cone and endoprosthetic connection adapter. Since the development of the single-stage protocol in 2014, almost all patients have had a single-stage surgical procedure instead of a 2-stage surgical procedure37, followed by a standardized rehabilitation protocol38. Rehabilitation occurs in 3 distinct and progressive phases. The first day after the surgical procedure, the patients stand and axially load the operatively treated leg through a manual bathroom scale, increasing progressively by 5 kg each day until they achieve 50 kg or 50% of their body weight, which should occur by week 2. A lightweight training leg is then attached, and core strengthening and balance exercises are performed, as well as supervised ambulation. The final stage of rehabilitation consists of attachment of the final prosthetic limb, and weight-bearing as tolerated with crutches is recommended. This process usually completes by 6 weeks after osseointegration. Unrestricted body-weight loading and ambulation are encouraged, but patients are cautioned that regaining adequate proprioception usually takes close to a year or even more, so they must be mindful of their balance to limit the potential for inadvertent falls.

The POP and the Compress Device are newer systems and surgical technique or rehabilitation guidelines have not yet been published to establish the preferences of their development groups. The ITAP has been discontinued and will not be further detailed.

Clinical Aspects of Osseointegration: Indications, Expected Outcomes, and Concerns

No formal consensus indications exist for osseointegration. Early contraindications included peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, age of >70 years, ongoing chemotherapy, immunosuppressive medications, skeletal immaturity, irradiated limbs, pregnancy, and situations of questionable patient compliance or psychiatric stability31,38,39. On the basis of positive early experience, some surgeons have expanded indications or disproven supposed contraindications to osseointegration, improving the mobility of patients with peripheral vascular disease40, those who underwent total hip arthroplasty41 or total knee arthroplasty42, and elderly patients who underwent amputation decades ago43. Although both major designs have been implanted into patients who have undergone transhumeral and transradial amputations, only the OPL has demonstrated a high success rate with patients who have undergone transtibial amputation, perhaps due to its 3-dimensional printed customization to individual patient anatomy. The screw design of the OPRA system has shown a particular utility in small implants such as thumb amputations30 and penile epitheses44. As basic science understanding and clinical experience improve, it is likely that the indications will broaden and the contraindications will narrow.

The overwhelming majority of amputees who change from a traditional socket prosthesis to an osseointegrated prosthesis improve dramatically, both subjectively and objectively. One study showed that when amputees changed from a socket prosthesis to an osseointegrated prosthesis, there were improvements on the Questionnaire for Persons with Transfemoral Amputation (from 45.27 to 84.86 points), Short Form-36 Physical Component Summary (from 36.97 to 49.00 points), 6 Minute Walk Test (from 286.25 to 512.72 meters), and the Timed Up and Go test (from 13.86 to 9.12 seconds)45. Another group reported similar trends for those same metrics and also found that the oxygen requirement was reduced from 1,330 mL/min to 1,093 mL/min46. Laboratory gait analysis revealed that cadence, duration of the gait cycle, and support phases are closer to normal in patients with osseointegrated prostheses than in patients with socketed prostheses47,48. Sitting comfort and position are improved49. Prosthesis use is high, with 82% to 90% of patients reporting daily use50. The donning and doffing are quicker and easier51. Patients have also reported that osseointegrated prostheses provide a much more intimate and “part of me” experience than socket prostheses52.

An additional exciting phenomenon that improves the patient experience with an osseointegrated prosthesis is that of osseoperception. Osseoperception is defined as the mechanical stimulation of a bone‐anchored prosthesis that is transduced by mechanoreceptors likely located in the muscles, joints, skin, and other bone-adjacent tissues that travel to the central nervous system to cause passive awareness of a patient’s own sensorimotor position and function53. Osseoperception has been well studied in dental implants, in which mechanical and neurologic mechanisms have been identified54. Although relatively few studies focus on this aspect of appendicular skeletal osseointegration, it is clear that osseointegrated prostheses facilitate improved vibration detection in patients compared with socket prostheses55,56. This improved sensation may, in part, be due to innervation in the newly integrated bone57. Further studies are needed to further characterize the potential clinical utility and day-to-day impact of this phenomenon on the patient quality of life.

One potential risk of osseointegration is periprosthetic fracture, which might lead to further impairment or more proximal amputation. To date, safety studies have only briefly touched on that topic18,58. Although, to our knowledge, no currently available peer-reviewed article exists specifically addressing fractures adjacent to osseointegration implants, periprosthetic fractures are managed with device removal and potential replacement in cases involving OPRA9 and POP59 implants, whereas fractures adjacent to ILP and OPL implants are managed with implant retention and routine fracture techniques such as plating60. Infection continues to be the main challenge, although this is less common than many believe. Even in this early stage of development and exploration, infection requiring an additional surgical procedure occurs in only 5% to 8% of patients18,61. This risk appears to be reducing as soft-tissue management experience increases, especially with a single-stage surgical procedure, and the risk of implant removal due to infection is even less common. Curiously, the risk of osteomyelitis following osseointegration might be influenced by the implant design62. Currently published infection rates reflect the outcomes of relatively tightly controlled and highly selected cohorts of patients. Unfortunately, the vast majority of amputees worldwide have diabetes3 and would be expected to have an increased risk of deep infection.

The ideal implant likely should achieve stable fixation immediately to allow independent ambulation, would be short (perhaps 5 to 10 cm) to allow implantation into very short residual bones without pre-lengthening procedures, would be inexpensive to manufacture, would successfully scale to accommodate a variety of long bones with similar techniques, would incorporate neural connection technology, would limit the risk of infection, and would provide durable long-term osseointegration. Of all those goals, perhaps the least certain is how to address the implant-skin interface. The transcutaneous nature of the implant and the exposure to the external environment represent the most clinically important and obvious risk. Generally, stable skin is less likely to become inflamed than skin that is moved or stretched18,63. Detailed research with regard to the ideal skin-implant interface is actively being pursued, and creative innovations may be necessary.

The Future of Osseointegration

The field of osseointegration has existed for almost 30 years and now appears to be on the verge of greater acceptance and widespread implementation. Beyond providing an excellent mobility solution for an expanding spectrum of long bone amputees, some patients with a hip disarticulation, hemipelvectomy, or flail arm due to brachial plexus avulsion have already had their mobility or quality of life improved by relatively simple technical improvisations to the established fundamentals of osseointegration. Amputation and osseointegration may even prove to be a favorable alternative when compared with limb-salvage megaprostheses for patients with appendicular skeletal tumors64 or those who have debilitating chronic pain in an extremity such as persistent complex regional pain syndrome.

Osseointegration already provides direct skeletal anchorage for prosthetic limbs designed with both afferent and efferent neural integration, allowing patients to more intuitively control the force65,66, approaching the scenes depicted in science fiction movies only a generation ago. It may soon be reasonable to restore sensation and mobility to amputees, perhaps even those with paralysis, with an intimately connected endoprosthetic limb67. However, the problem of infection must be aggressively researched: is an antler model actually achievable in humans, or would a fingernail, gum-tooth, or muscular sphincter interface be a better concept to adopt?

Perhaps the most exciting developing frontier of osseointegration may not be strictly medical, but instead may reflect changes in regulation and legislation, with greater access to care afforded by a potential influx of supply. Upon FDA trial completion, American institutions with immediately available funding may quickly scale procedures to meet existing domestic demand. With the resultant increased implant production, the unit cost per implant should be reduced, and this would, in turn, permit greater access worldwide. This is especially important for patients who live in areas of the world where amputation is often the solution to relatively routine trauma, or where land mines and war injuries remain a devastating cause of limb loss68,69. Given the value and impact of orthopaedic outreach recently endorsed by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS)70 and the already-proven success providing high-quality single-surgery osseointegration even in hospitals with modest resources such as in postwar environments71, osseointegration seems ready to quickly and dramatically improve the lives of millions of amputees around the world.

Osseointegration for the reconstruction of the amputated limb appears to now be poised to follow a trajectory similar to that demonstrated by total joint arthroplasty, which gained universal acceptance and then underwent widespread adoption globally over the past 50 years. As the concepts and principles guiding surgical techniques and implant technology become further established and more uniform, the surgeons and other clinicians providing care and the patients benefiting most from this procedure can become even more diverse.

Footnotes

Investigation performed at Macquarie University Hospital, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Disclosure: The authors indicated that no external funding was received for any aspect of this work. On the Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest forms, which are provided with the online version of the article, one or more of the authors checked “yes” to indicate that the author had a relevant financial relationship in the biomedical arena outside the submitted work (including with the manufacturers of some of implants discussed in this article) and “yes” to indicate that the author had a patent and/or copyright, planned, pending, or issued, broadly relevant to this work (including for some of the implants discussed in this article) (http://links.lww.com/JBJSREV/A561).

References

- 1.Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, Travison TG, Brookmeyer R. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008. March;89(3):422-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moxey PW, Gogalniceanu P, Hinchliffe RJ, Loftus IM, Jones KJ, Thompson MM, Holt PJ. Lower extremity amputations—a review of global variability in incidence. Diabet Med. 2011. October;28(10):1144-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. 8th ed. 2017. https://diabetesatlas.org/. Accessed 2019 Jun 25. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koc E, Tunca M, Akar A, Erbil AH, Demiralp B, Arca E. Skin problems in amputees: a descriptive study. Int J Dermatol. 2008. May;47(5):463-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, MacKenzie EJ, Burgess AR. Use and satisfaction with prosthetic devices among persons with trauma-related amputations: a long-term outcome study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001. August;80(8):563-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanders JE, Fatone S. Residual limb volume change: systematic review of measurement and management. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011;48(8):949-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nehler MR, Coll JR, Hiatt WR, Regensteiner JG, Schnickel GT, Klenke WA, Strecker PK, Anderson MW, Jones DN, Whitehill TA, Moskowitz S, Krupski WC. Functional outcome in a contemporary series of major lower extremity amputations. J Vasc Surg. 2003. July;38(1):7-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagberg K, Brånemark R. Consequences of non-vascular trans-femoral amputation: a survey of quality of life, prosthetic use and problems. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2001. December;25(3):186-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, Brånemark R. Osseointegrated prostheses for rehabilitation following amputation: the pioneering Swedish model. Unfallchirurg. 2017. April;120(4):285-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abraham CM. A brief historical perspective on dental implants, their surface coatings and treatments. Open Dent J. 2014. May 16;8:50-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Velzen FJJ, Ofec R, Schulten EAJM, Ten Bruggenkate CM. 10-year survival rate and the incidence of peri-implant disease of 374 titanium dental implants with a SLA surface: a prospective cohort study in 177 fully and partially edentulous patients. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2015. October;26(10):1121-8. Epub 2014 Nov 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Head WC, Bauk DJ, Emerson RH., Jr Titanium as the material of choice for cementless femoral components in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995. Feb;311:85-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu W, Crocombe AD, Hughes SC. Finite element analysis of bone stress and strain around a distal osseointegrated implant for prosthetic limb attachment. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 2000;214(6):595-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mooney V, Schwartz SA, Roth AM, Gorniowsky MJ. Percutaneous implant devices. Ann Biomed Eng. 1977. March;5(1):34-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy EF. History and philosophy of attachment of prostheses to the musculo-skeletal system and of passage through the skin with inert materials. J Biomed Mater Res. 1973;7(3):275-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jönsson S, Caine-Winterberger K, Brånemark R. Osseointegration amputation prostheses on the upper limbs: methods, prosthetics and rehabilitation. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2011. June;35(2):190-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Integrum . OPRA Implant System. https://integrum.se/opra-implant-system/. Accessed 2019 Jun 25. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al Muderis M, Khemka A, Lord SJ, Van de Meent H, Frölke JPM. Safety of osseointegrated implants for transfemoral amputees: a two-center prospective cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016. June 1;98(11):900-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Humanitarian Device Exemption (HDE). OPRA. 2019. June 24 https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfhde/hde.cfm?id=H080004. Accessed 2019 Jun 25. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wegner L, Rhoda A. Common causes of lower limb amputation in a rural community in South Africa [abstract]. In: Proceedings of the 23rd International Academic Conference, Venice; 2016. April 27-30 International Institute of Social and Economic Sciences (IISES); 2016 p 515. [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Fátima Dornelas L. Uso da prótese e retorno ao trabalho em amputados por acidentes de transporte. Acta Ortop Bras. 2010. January;18(4):204-6. Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmad N, Thomas GN, Gill P, Torella F. The prevalence of major lower limb amputation in the diabetic and non-diabetic population of England 2003-2013. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2016. September;13(5):348-53. Epub 2016 Jun 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norman PE, Schoen DE, Gurr JM, Kolybaba ML. High rates of amputation among indigenous people in Western Australia. Med J Aust. 2010. April 5;192(7):421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thesleff A, Brånemark R, Håkansson B, Ortiz-Catalan M. Biomechanical characterisation of bone-anchored implant systems for amputation limb prostheses: a systematic review. Ann Biomed Eng. 2018. March;46(3):377-91. Epub 2018 Jan 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al Muderis M, Lu W, Li JJ. Osseointegrated Prosthetic Limb for the treatment of lower limb amputations: experience and outcomes. Unfallchirurg. 2017. April;120(4):306-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holt BM, Bachus KN, Jeyapalina S, Beck JP, Bloebaum R. Percutaneous osseointegrated prosthetic implant system. United States Patent No. US 9,668,889 B2. 2017. June 6 https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/03/24/50/b33765aeee1279/US9668889.pdf. Accessed 2019 Jun 25. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGough RL, Goodman MA, Randall RL, Forsberg JA, Potter BK, Lindsey B. The Compress® transcutaneous implant for rehabilitation following limb amputation. Unfallchirurg. 2017. April;120(4):300-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kramer MJ, Tanner BJ, Horvai AE, O’Donnell RJ. Compressive osseointegration promotes viable bone at the endoprosthetic interface: retrieval study of Compress implants. Int Orthop. 2008. October;32(5):567-71. Epub 2007 Jun 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fitzpatrick N, Smith TJ, Pendegrass CJ, Yeadon R, Ring M, Goodship AE, Blunn GW. Intraosseous Transcutaneous Amputation Prosthesis (ITAP) for limb salvage in 4 dogs. Vet Surg. 2011. December;40(8):909-25. Epub 2011 Nov 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Kulbacka-Ortiz K, Caine-Winterberger K, Brånemark R. Thumb amputations treated with osseointegrated percutaneous prostheses with up to 25 years of follow-up. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2019. January 23;3(1):e097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hagberg K, Brånemark R. One hundred patients treated with osseointegrated transfemoral amputation prostheses—rehabilitation perspective. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(3):331-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aschoff H. Osseointegrated percutaneous implants for rehabilitation following below-knee amputation. Read at the First International Symposium on Innovations in Amputation Surgery and Prosthetic Technologies; 2016. May 13; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al Muderis M, Atallah R, Lu WY, Li JJ, Frolke JPM. Safety of osseointegrated implants for transtibial amputees: a two-center prospective proof-of-concept study. Read at the Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2019. March 13; Las Vegas, NV: Paper no. 431. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fragomen AT, Rozbruch SR. Lengthening of the femur with a remote-controlled magnetic intramedullary nail: retrograde technique. JBJS Essent Surg Tech. 2016. May 11;6(2):e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rozbruch SR, Birch JG, Dahl MT, Herzenberg JE. Motorized intramedullary nail for management of limb-length discrepancy and deformity. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014. July;22(7):403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirane YM, Fragomen AT, Rozbruch SR. Precision of the PRECICE internal bone lengthening nail. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014. December;472(12):3869-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al Muderis M, Tetsworth K, Khemka A, Wilmot S, Bosley B, Lord SJ, Glatt V. The Osseointegration Group of Australia Accelerated Protocol (OGAAP-1) for two-stage osseointegrated reconstruction of amputated limbs. Bone Joint J. 2016. July;98-B(7):952-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al Muderis M, Lu W, Tetsworth K, Bosley B, Li JJ. Single-stage osseointegrated reconstruction and rehabilitation of lower limb amputees: the Osseointegration Group of Australia Accelerated Protocol-2 (OGAAP-2) for a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017. March 22;7(3):e013508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sullivan J, Uden M, Robinson KP, Sooriakumaran S. Rehabilitation of the trans-femoral amputee with an osseointegrated prosthesis: the United Kingdom experience. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2003. August;27(2):114-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atallah R, Li JJ, Lu W, Leijendekkers R, Frölke JP, Al Muderis M. Osseointegrated transtibial implants in patients with peripheral vascular disease: a multicenter case series of 5 patients with 1-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017. September 20;99(18):1516-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khemka A, FarajAllah CI, Lord SJ, Bosley B, Al Muderis M. Osseointegrated total hip replacement connected to a lower limb prosthesis: a proof-of-concept study with three cases. J Orthop Surg Res. 2016. January 19;11:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khemka A, Frossard L, Lord SJ, Bosley B, Al Muderis M. Osseointegrated total knee replacement connected to a lower limb prosthesis: 4 cases. Acta Orthop. 2015;86(6):740-4. Epub 2015 Aug 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leijendekkers RA, van Hinte G, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW, Staal JB. Gait rehabilitation for a patient with an osseointegrated prosthesis following transfemoral amputation. Physiother Theory Pract. 2017. February;33(2):147-61. Epub 2017 Jan 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Selvaggi G, Branemark R, Elander A, Liden M, Stalfors J. Titanium-bone-anchored penile epithesis: preoperative planning and immediate postoperative results. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2015. February;49(1):40-4. Epub 2014 Jun 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al Muderis M, Lu W, Glatt V, Tetsworth K. Two-stage osseointegrated reconstruction of post-traumatic unilateral transfemoral amputees. Mil Med. 2018. March 1;183(suppl_1):496-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van de Meent H, Hopman MT, Frölke JP. Walking ability and quality of life in subjects with transfemoral amputation: a comparison of osseointegration with socket prostheses. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013. November;94(11):2174-8. Epub 2013 Jun 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frossard L, Hagberg K, Häggström E, Gow DL, Brånemark R, Pearcy M. Functional outcome of transfemoral amputees fitted with an osseointegrated fixation: temporal gait characteristics. J Prosthet Orthot. 2010;22(1):11-20. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frossard L, Stevenson N, Sullivan J, Uden M, Pearcy M. Categorization of activities of daily living of lower limb amputees during short-term use of a portable kinetic recording system: a preliminary study. J Prosthet Orthot. 2011;23(1):2-11. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hagberg K, Häggström E, Uden M, Brånemark R. Socket versus bone-anchored trans-femoral prostheses: hip range of motion and sitting comfort. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2005. August;29(2):153-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Eck CF, McGough RL. Clinical outcome of osseointegrated prostheses for lower extremity amputations: a systematic review of the literature. Curr Orthop Pract. 2015. Jul-Aug;26(4):349-57. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hagberg K, Brånemark R, Gunterberg B, Rydevik B. Osseointegrated trans-femoral amputation prostheses: prospective results of general and condition-specific quality of life in 18 patients at 2-year follow-up. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2008. March;32(1):29-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lundberg M, Hagberg K, Bullington J. My prosthesis as a part of me: a qualitative analysis of living with an osseointegrated prosthetic limb. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2011. June;35(2):207-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klineberg I, Calford MB, Dreher B, Henry P, Macefield V, Miles T, Rowe M, Sessle B, Trulsson M. A consensus statement on osseoperception. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2005. Jan-Feb;32(1-2):145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bhatnagar VM, Karani JT, Khanna A, Badwaik P, Pai A. Osseoperception: an implant mediated sensory motor control- a review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015. September;9(9):ZE18-20. Epub 2015 Sep 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Häggström E, Hagberg K, Rydevik B, Brånemark R. Vibrotactile evaluation: osseointegrated versus socket-suspended transfemoral prostheses. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(10):1423-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jacobs R, Brånemark R, Olmarker K, Rydevik B, Van Steenberghe D, Brånemark PI. Evaluation of the psychophysical detection threshold level for vibrotactile and pressure stimulation of prosthetic limbs using bone anchorage or soft tissue support. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2000. August;24(2):133-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ysander M, Brånemark R, Olmarker K, Myers RR. Intramedullary osseointegration: development of a rodent model and study of histology and neuropeptide changes around titanium implants. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2001. Mar-Apr;38(2):183-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsikandylakis G, Berlin Ö, Brånemark R. Implant survival, adverse events, and bone remodeling of osseointegrated percutaneous implants for transhumeral amputees. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014. October;472(10):2947-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gillespie B. Development of a percutaneous osseointegrated prosthesis for transfemoral amputees. Presented at the State of the Science Symposium: Recent Advances in Osseointegration Rehabilitation; 2019. May 17; Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu W. Comments made during presentation by Gillepsie B. Development of a percutaneous osseointegrated prosthesis for transfemoral amputees. Presented at the State of the Science Symposium: Recent Advances in Osseointegration Rehabilitation; 2019. May 17; Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tillander J, Hagberg K, Hagberg L, Brånemark R. Osseointegrated titanium implants for limb prostheses attachments: infectious complications. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010. October;468(10):2781-8. Epub 2010 May 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tillander J, Hagberg K, Berlin Ö, Hagberg L, Brånemark R. Osteomyelitis risk in patients with transfemoral amputations treated with osseointegration prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017. December;475(12):3100-8. Epub 2017 Sep 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paley D. Problems, obstacles, and complications of limb lengthening by the Ilizarov technique. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990. January;250:81-104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schmolders J, Koob S, Schepers P, Pennekamp PH, Gravius S, Wirtz DC, Placzek R, Strauss AC. Lower limb reconstruction in tumor patients using modular silver-coated megaprostheses with regard to perimegaprosthetic joint infection: a case series, including 100 patients and review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2017. February;137(2):149-53. Epub 2016 Oct 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mastinu E, Branemark R, Aszmann O, Ortiz-Catalan M. Myoelectric signals and pattern recognition from implanted electrodes in two TMR subjects with an osseointegrated communication interface. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2018. July;2018:5174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ortiz-Catalan M, Håkansson B, Brånemark R. An osseointegrated human-machine gateway for long-term sensory feedback and motor control of artificial limbs. Sci Transl Med. 2014. October 8;6(257):257re6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pasquina PF, Evangelista M, Carvalho AJ, Lockhart J, Griffin S, Nanos G, McKay P, Hansen M, Ipsen D, Vandersea J, Butkus J, Miller M, Murphy I, Hankin D. First-in-man demonstration of a fully implanted myoelectric sensors system to control an advanced electromechanical prosthetic hand. J Neurosci Methods. 2015. April 15;244:85-93. Epub 2014 Aug 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ebrahimzadeh MH, Rajabi MT. Long-term outcomes of patients undergoing war-related amputations of the foot and ankle. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2007. Nov-Dec;46(6):429-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McKinley TO, DʼAlleyrand JC, Valerio I, Schoebel S, Tetsworth K, Elster EA. Management of mangled extremities and orthopaedic war injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2018. March;32(Suppl 1):S37-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.D’Onofrio K. What you give—and gain—through humanitarian outreach. 2019. January https://www.aaos.org/AAOSNow/2019/Jan/Cover/cover01/?ssopc=1. Accessed 2019 Jun 25. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Al Muderis M, Weaver P. Going back: how a former refugee, now an internationally acclaimed surgeon, returned to Iraq to change the lives of injured soldiers and civilians. Allen & Unwin; 2019. [Google Scholar]