Abstract

Many aspects of the supposed hyperthermal Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (T-OAE, Early Jurassic, c. 182 Ma) are well understood but a lack of robust palaeotemperature data severely limits reconstruction of the processes that drove the T-OAE and associated environmental and biotic changes. New oxygen isotope data from calcite shells of the benthic fauna suggest that bottom water temperatures in the western Tethys were elevated by c. 3.5 °C through the entire T-OAE. Modelling supports the idea that widespread marine anoxia was induced by a greenhouse-driven weathering pulse, and is compatible with the OAE duration being extended by limitation of the global silicate weathering flux. In the western Tethys Ocean, the later part of the T-OAE is characterized by abundant occurrences of the brachiopod Soaresirhynchia, which exhibits characteristics of slow-growing, deep sea brachiopods. The unlikely success of Soaresirhynchia in a hyperthermal event is attributed here to low metabolic rate, which put it at an advantage over other species from shallow epicontinental environments with higher metabolic demand.

Subject terms: Carbon cycle, Palaeoceanography, Palaeoclimate

Introduction

The Early Jurassic Toarcian Stage is characterized by possibly the largest global carbon cycle perturbation since the beginning of the Mesozoic (c. 250 Ma)1,2. A series of such perturbations, evidenced by large-scale carbon isotope excursions (CIE’s), through the late Pliensbachian to middle Toarcian stages (c. 184–180 Ma), are recorded globally by sedimentary strata. Organic matter and carbonate in bulk sediments2–4, as well as fossil wood1 and macrofossils5,6, show excursions in carbon isotope ratios which have not been matched in size since. This episode of environmental change was associated with widespread marine deposition of laminated, organic-rich mud in epicontinental seas, suggestive of at least regionally severe water de-oxygenation7,8, and has consequently become known as the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (T-OAE).

The evolution of environmental conditions across the T-OAE interval has been reconstructed in high temporal detail in previous studies. The earliest Toarcian is marked by the recovery from a negative CIE at the Pliensbachian-Toarcian boundary5,9 and linked to early magmatism of the Karoo-Ferrar large igneous province10–13. Within the T-OAE, regular, stepped changes in carbon isotope ratios resulted in a strong δ13C decrease, have been documented. These steps have been interpreted to signify repeated, astronomically paced, widespread release of methane from various sources3,14–16, probably also initially triggered by large scale volcanism of the Karoo-Ferrar Large Igneous Province. After the peak of the negative CIE, carbon isotope ratios rose strongly with δ13C values reaching up to around +6‰ in belemnite calcite in the UK sections6,17 and >+5‰ in brachiopod calcite in Portugal5,18. This positive shift of c. 5‰, in conjunction with coeval globally observed deposition of organic rich muds in marine7 and lacustrine strata19, can be taken as clear indication for large-scale organic matter burial preferentially removing 12C from the exogenic carbon cycle7,13,14.

Biotic consequences of the T-OAE were far-reaching reorganizations of marine and terrestrial flora and fauna, including severe extinctions and protracted recovery from the loss of biodiversity20–24. The magnitude and duration of the greenhouse warming that must have been associated with the large-scale release of methane and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, however, has so far been hard to quantify reliably. The lack of robust palaeotemperature reconstructions is due to poor proxy calibrations from sedimentary successions of this age, as well as proxy resetting due to post-depositional processes. The best established proxy for Jurassic seawater temperatures, oxygen isotope ratios in marine biological carbonates, requires the continued presence of well-preserved fossils with known life habits in sedimentary archives, even within the strata representative of the most severe environmental upheaval. These prerequisites have proven challenging for reconstructing temperature change across the T-OAE. Most records rely on the calcite of belemnite rostra6,25 which are rare or absent from strata deposited during peak anoxic conditions, and for which complications arising from vital effects and changes in habitat depth cannot be discounted. Data on calcite secreting, sessile faunas of the seafloor on the other hand are sparse, particularly in the intervals of most extreme environmental conditions5,18,26.

In this contribution we make use of a new multiproxy dataset to provide a high-quality, temporally well-resolved record of oxygen and carbon isotope data through the early Toarcian. The aim is to use these data to provide guidance on the evolution of temperatures and carbon cycle and to assess first-order controls on Earth system responses. This large dataset comprises macrofossil ranges, shell structure, element/Ca, and C and O isotope ratios for multiple taxa of rhynchonellid brachiopods, the bivalve Gryphaea, belemnite calcite, diagenetic cements, and bulk rocks, of the Toarcian strata from the Barranco de la Cañada section in Spain (40°23′53.4″N, 1°30′07.4″W; Fig. 1, supplements). These 550 geochemical analyses are supplemented by equivalent results from 135 brachiopod, bivalve and bulk rock samples from a correlative succession of Toarcian strata at Fonte Coberta and Rabaçal, Portugal (Fonte Coberta: 40°03′36.5″N, 8°27′33.4″W; Rabaçal: 40°03′08.0″N, 8°27′30.5″W; Fig. 1). Taxonomic control as well as rigorous optical and chemical screening of the shells for diagenesis permit discussion of palaeotemperature evolution and its relation to the carbon cycle perturbation of the T-OAE with a high degree of quantitative detail. The biomineral structures and geochemical fingerprints of the brachiopods represented in the strata are also studied in detail. These data are used to establish novel proxies that help better understand the extraordinary success of the brachiopod genus Soaresirhynchia during times of severe environmental change.

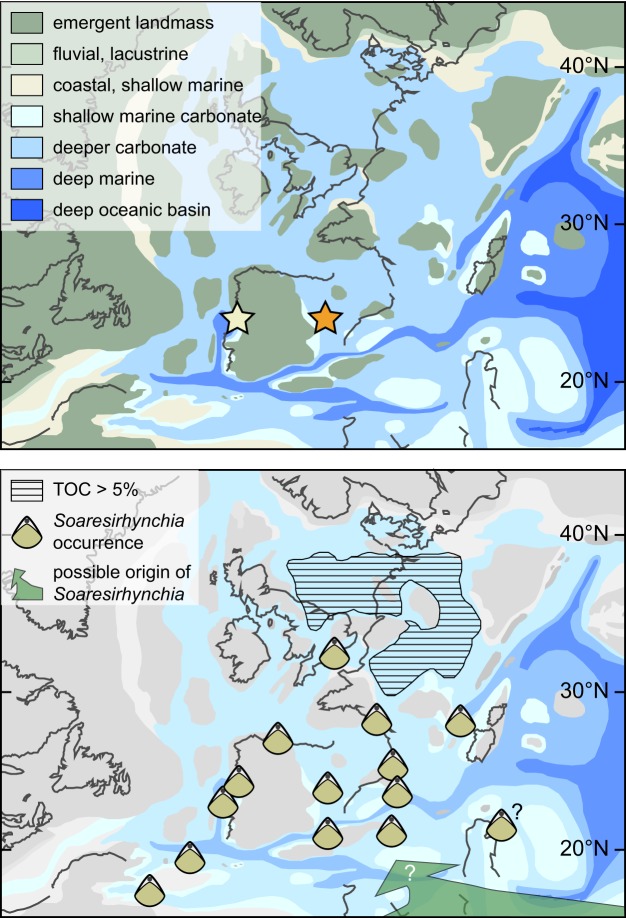

Figure 1.

Upper panel: Toarcian palaeogeography after Ref. 71. with sampled stratigraphic successions marked with stars (yellow star, Fonte Coberta / Rabaçal; orange star: Barranco de la Cañada). Lower panel: Same palaeogeography overlain by early Toarcian occurrences of Soaresirhynchia taken from refs. 22,60, areal extent of organic rich mudstones with TOC > 5 wt %72 and putative deep water habitat and migration direction of Soaresirhynchia62.

Results

Carbon and oxygen isotope stratigraphy

Carbon and oxygen isotope ratios of well-preserved rhynchonellid brachiopods and the bivalve Gryphaea (see supplements for assessment of preservation and construction of combined isotope record) show distinct fluctuations through the Barranco de la Cañada section (Fig. 2).

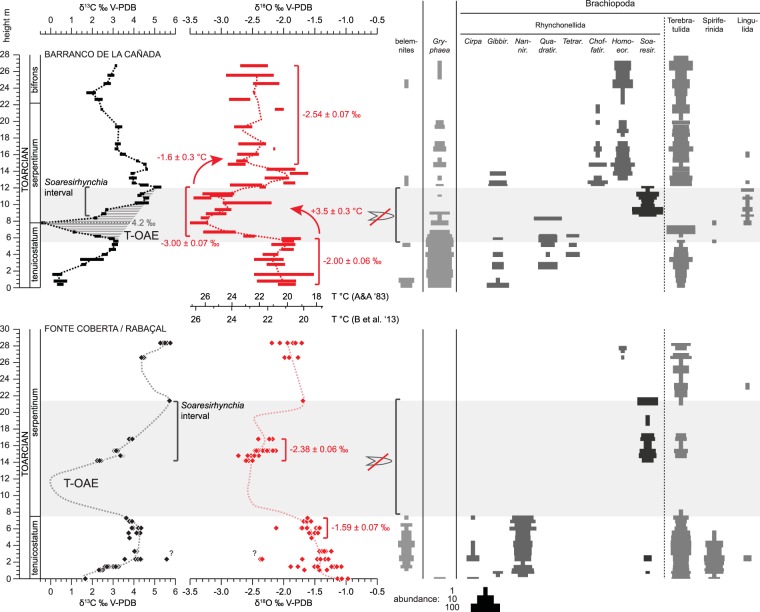

Figure 2.

C and O isotope stratigraphy as well as species distribution data for Barranco de la Cañada and Fonte Coberta/Rabaçal. C and O isotope data for Barranco de la Cañada are shown as averages with error bars of 2 standard errors of the mean, and the dotted line for oxygen isotope ratios represents a three point running average. Absolute temperature changes are computed using the oxygen isotope thermometers of Brand et al.39 and Anderson and Arthur69 for comparison. For Fonte Coberta/Rabaçal, for which fewer data are available, all individual brachiopod measurements that passed screening for diagenesis are plotted. Dotted lines represent the schematic evolution of isotopic ratios expected for this section from observations in well studied sections in Peniche (Lusitanian Basin1,5) and analytical data from Barranco de la Cañada. The belemnite gap in Fonte Coberta/Rabaçal is based on observations and comparison to correlative strata in Peniche1. The duration of the T-OAE (light grey band) as indicated by the negative CIE and elevated temperatures coincides remarkably well with the extent of this belemnite gap.

In the lowest three Toarcian horizons, δ13C values of +0.3 to +0.5‰ are recorded, above which a rise to +3.1‰ occurs. Above 5.6 m, a strong decrease in δ13C values commences, which culminates in a value of −0.4‰ at 7.8 m height. Within sampling resolution, this position coincides with the boundary of the tenuicostatum and serpentinum ammonite zones. Above this minimum, δ13C values recover and reach very positive values averaging +5.1‰ at 12.1 m height. Upsection, a general decrease of δ13C to c. +2.5‰ with superimposed minor fluctuations is observed which reaches into the lower bifrons ammonite zone.

Over the same interval, δ18O values are initially stable, with averages from −2.2 to −1.9‰ up to 5.9 m. Here, a strong decrease occurs with average values of −3.4 to −2.3‰ recorded in the interval from 6.2 to 12.4 m, encompassing the entire negative carbon isotope excursion. After a stratigraphically narrow return to less negative δ18O values of −2.1 to −1.8‰ in the interval from 12.6 to 14.3 m, δ18O attains intermediate values of −2.8 to −2.1‰ for the remainder of the studied part of the succession.

Correlative strata from the Portuguese section at Fonte Coberta / Rabaçal show qualitatively the same trends, but rarity of benthic organisms in parts of the studied strata leads to a less detailed record (Fig. 2). The rise of δ13C values through the lowest Toarcian and the initiation of the subsequent negative CIE are well developed in the lowest 8 m, representing the tenuicostatum ammonite zone. Above an interval of c. 6 m barren in brachiopods, a prominent rise in δ13C values from +2.4 to +5.7‰ is observed which is followed upwards by comparatively positive δ13C values between +4.4 to +5.8‰.

Oxygen isotope ratios in the Tenuicostatum zone at Fonte Coberta / Rabaçal are comparatively positive averaging −1.59 ± 0.07‰ (2 standard errors of the mean = 2se, n = 19) in the interval from 4.9 to 7.3 m. Distinctly more negative values are recorded by brachiopods from the lower serpentinum ammonite zone, averaging −2.38 ± 0.06‰ (2 se, n = 32) in the interval from 14.2 to 16.8 m. The δ18O values higher up in the section are intermediate between these two extremes.

Brachiopod ranges

In the studied interval, profound changes in the brachiopod assemblage are recorded in both successions which are consistent with previous reports21,27 (Fig. 2). The lowermost Toarcian strata in Barranco de la Cañada are characterized by the rhynchonellids Gibbirhynchia and Quadratirhynchia as well as sparse occurrences of Tetrarhynchia. Terebratulids are generally common and abundant in the uppermost part of the Tenuicostatum zone. This assemblage is abruptly replaced at the level of 8.7 m by the rhynchonellid Soaresirhynchia as the only brachiopod apart from rare occurrences of lingulids. The disappearance of Soaresirhynchia c. 3.5 m higher in the section is marked by the return of other rhynchonellids represented by Gibbirhynchia, Choffatirhynchia and Homoeorhynchia as well as terebratulids which are common in most collected beds of this interval. After initially abundant occurrence, the bivalve Gryphaea drops abruptly in abundance at 7 m, above which it occurs only sporadically and particularly seldom in the interval from 9.4 to 14.3 m. Belemnites are generally rare and entirely absent in the interval from 5.6 to 12.1 m.

In Fonte Coberta/Rabaçal the rhynchonellid genera Cirpa and Nannirhynchia are observed in the Tenuicostatum zone, together with common terebratulids, the last spiriferinids, and very rare finds of Gibbirhynchia, Soaresirhynchia, and lingulid brachiopods27,28 (Fig. 2). Above a brachiopod-barren interval between 7.9 and 14.2 m in this section, Soaresishynchia occurs together with sparse terebratulids and is followed by an impoverished fauna of terebratulids with a single find of a lingulid brachiopod and rare specimens of Homoeorhynchia.

Brachiopod geochemistry and ultrastructure

Detailed characterisation of shell ultrastructure and investigation of a large number of brachiopod samples for their geochemical signatures allows establishment here of a series of novel proxies for palaeobiological function. These proxies help understanding brachiopod palaeoecology, especially in the context of major environmental change. Besides distinct differences in the morphology of shell fibres, we also employ an approximation of shell organic matter content, the intra-specimen isotopic variability, and element/Ca ratios, to inform about growth rate and metabolic rate.

Two distinct types of shell ultrastructure are observed for the secondary layer calcite of the studied rhynchonellid brachiopods (Fig. 3).

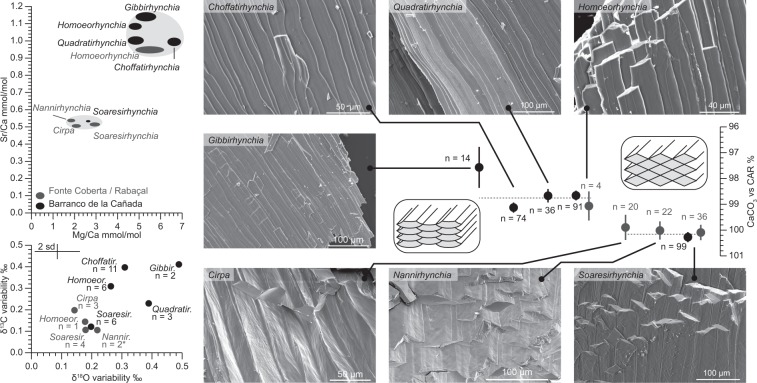

Figure 3.

Ultrastructural and geochemical compositions of studied rhynchonellid brachiopods. Black symbols: Barranco de la Cañada, grey symbols: Fonte Coberta/Rabaçal. Top left: Average Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca data for studied taxa. The ellipses indicate 95% confidence intervals of the averages for each genus. Light grey areas delineate two clusters assigned to shallow water forms with higher Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca and deeper water forms with very low Sr/Ca and Mg/Ca ratios. Bottom left: Median 2 sd isotopic variability of individual brachiopods from different genera sampled from the two sections. Only specimens for which 4 or more analyses were available were used (*: One spurious datum excluded, supplements). Error bars indicate analytical uncertainty for single isotope measurements. Right hand side: Representative SEM images of different observed shell structures illustrating the diamond-shaped cross sections of Cirpa, Nannirhynchia, and Soaresirhynchia. Schematic morphologies of the two different groups are plotted next to measurements of their average computed CaCO3 concentration versus the in-house calcite standard CAR (Carrara Marble). Note the inverted axis to illustrate the lower non-carbonate fraction at high CO2 yields. The difference between the two groups is 1.4%. Error bars denote 2 standard errors of the mean (2 se).

The fibres of Soaresirhynchia, Cirpa and Nannirhynchia have markedly diamond-shaped to rectangular cross sections with a distinct surface pattern of oblique, slightly curved bands that are laterally continuous across multiple shell fibres. The secondary layer calcite of other studied rhynchonellids in contrast comprises smooth fibres with typically flattened, hat-shaped cross section (Fig. 3).

The two brachiopod taxonomic clusters with shared ultrastructure characteristics are also distinct in their shell geochemical composition. The biomineral fibres of Soaresirhynchia, Cirpa and Nannirhynchia secondary shell layers have a c. 1.4% higher carbonate content than the other rhynchonellids (Fig. 3), suggesting that their shell calcite contains substantially less intracrystalline organic matter than that of Gibbirhynchia, Homoeorhynchia, Quadratirhynchia and Choffatirhynchia. Cation and anion impurities are also significantly lower in the former genera (Fig. 3), forming a cluster at 1.8 to 2.9 mmol/mol Mg/Ca and 0.51 to 0.54 mmol/mol Sr/Ca compared to 4.8 to 6.6 mmol/mol Mg/Ca and 0.95 to 1.14 mmol/mol Sr/Ca in the latter. Furthermore, Soaresirhynchia is the only studied brachiopod genus from the Barranco de la Cañada section whose Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca ratios are consistently lower than those of the bivalve Gryphaea. The difference is 0.3 ± 0.2 (2 se) mmol/mol for Mg/Ca and 0.21 ± 0.02 (2 se) mmol/mol for Sr/Ca.

Early Jurassic environments constrained by brachiopods

Brachiopods were amongst the first animals to successfully adopt external hard parts during the biomineralisation revolution of the Proterozoic-Paleozoic transition around 540 million years ago. Today, they are found in the oceans across a wide range of latitudes and water depths, even though their relative contribution to the composition of marine faunal assemblages has declined since the Mesozoic29. Modern brachiopods are characterized by a remarkable diversity in biomineralisation strategies and multi-layered shell structures, which are formed by amorphous calcium carbonate, low magnesium calcite, high magnesium calcite and phosphate30. This wide range of structure and composition is an evolutionary asset acquired, broadened, and preserved by brachiopods over more than 500 million years during which they adapted to environmental change and climatic upheavals that at times, as during the T-OAE, were catastrophic for global faunal diversity.

The early Toarcian carbon cycle perturbation

The most characteristic feature of the T-OAE carbon cycle perturbation is a pronounced negative CIE of several permil in magnitude commencing in the uppermost tenuicostatum ammonite zone1,3,4,7,13 (Fig. 2). The exact nature of this excursion is still debated, as its magnitude has been hard to constrain robustly. Belemnite calcite records6,25 usually show hardly any negative CIE, which can at least conceptually be explained by faunal turnover and habitat shifts of these mobile, marine predators6. Bulk organic matter3,4,7 and wood1,14,31 records on the other hand commonly feature a very prominent negative CIE, reaching amplitudes as large as 8‰. This amplitude is thought to be inflated due to coincident changes in organic matter sources for bulk organic matter2 as well as physiological effects in terrestrial floras1. To account for these effects, an amplitude correction has been proposed that limits the size of the negative carbon isotope excursion to 3–4‰2. The newly generated macrofossil dataset does not suffer from the above problems as it is derived from benthic organisms that are known for their consistent biomineralisation behaviour devoid of vital effects32,33. The negative CIE observed in Barranco de la Cañada has an amplitude of 4.2‰ when compared against a hypothetical linear increase between the carbon isotope maxima bounding the CIE (Fig. 2). This magnitude may nevertheless be somewhat biased. Potentially, strata relating to the most negative carbon isotope ratios were either not deposited or did not yield calcite fossils. The δ13C of ambient dissolved inorganic carbon may have also been somewhat affected by potential changes in surface productivity6. Nevertheless, because all other means of reconstructing the magnitude of the negative CIE are affected by the same complications, the new magnitude estimate is thought to be the most reliable thus far.

A rough estimate of the mass of 13C-depleted carbon that must be introduced into the exchangeable ocean-atmosphere carbon pool in order to drive the observed negative CIE can be derived from simple mass balance equations (see supplement, ref. 34). Assuming an exchangeable carbon pool with an average δ13C value of +2.6‰ and a size two to four times as great as that of pre-industrial times35, the observed negative CIE would require the addition of c. 3,500 to 7,000 Gt of carbon derived from methane (supplements). However, this estimate needs to be taken as a minimum for the amount of carbon injected into the ocean-atmosphere system. More realistically, one should conceive of the carbon cycle perturbations as resulting from multiple carbon sources, rather than a discrete, singular perturbation represented by the above calculations3,4,15,31,36.

Toarcian temperature evolution

The classification of the T-OAE as a major hyperthermal episode is not controversial (e.g. ref. 37), but the thermal evolution of the Earth surface system during the Toarcian is still poorly known. Large published belemnite datasets are likely affected by habitat and water mass changes6,38. Therefore, palaeotemperatures computed from the calcite of their fossil hard parts should not be taken as unequivocal reflection of sea surface water temperature. Data published on brachiopods5,18,26 on the other hand are hitherto sparse, lack resolution in the hyperthermal interval, and are partially based on terebratulids which are more prone than rhynchonellids to metabolically induced isotope disequilibrium33.

The newly gathered data from well-preserved fossils from the Barranco de la Cañada section now show that the beginning of the hyperthermal coincides precisely with the onset of the negative CIE (Fig. 2). The temperature increase is marked by a negative shift of 1.00 ± 0.09‰ in δ18O. Using the brachiopod oxygen isotope thermometer of Brand et al.39, this shift computes to a temperature increase of 3.5 ± 0.3 °C at the seafloor of the shallow epicontinental basin (Fig. 2; supplements), if confounding effects of sea-level change and salinity fluctuations can be discounted. This magnitude of temperature change is lower than previously inferred from brachiopod datasets from Portugal5 and Spain26, which can be explained by very different sample sizes. The earlier datasets are limited to a comparatively small number of analyses for which the inferred difference between coldest and warmest temperatures was taken to reflect T-OAE temperature change. Here, it is possible to quantify the increase of average temperatures from the earliest Toarcian into the T-OAE. This quantity is necessarily smaller than the difference between minimum pre-event and maximum event temperatures, but better reflects changes in the Earth surface system.

Besides temperature increase, more negative δ18O values could signify shallowing or partial freshening of the local seawater. Early Toarcian changes in sea-level have been recognized in Spanish21 and Portuguese basins1,40,41, generally pointing to an overall transgression and deepening. Inferring that sea-level is the primary driver of the observed oxygen isotope variability is therefore inconsistent with these reconstructions. Sea-level reconstructions neither suggest entirely parallel evolution in Portugal and Spain, nor a marked shallowing confined to the upper tenuicostatum and lower serpentinum zones. A gradual shallowing of a thermally stratified water body is also contradicted by the depositional environment of the studied sections21,27. Water mass stratification would likely have induced persistent bottom water anoxia for which there is no lithological or faunal indication in either of the studied successions.

Freshening has been proposed for UK and German basins42,43. However, the continuous presence of stenohaline organisms in both studied sections, particularly brachiopods44, makes such an interpretation unlikely. Salinity decrease in the European epicontinental sea has been interpreted to be much less noticeable in the Iberian region than the more northerly German and UK sites42,43. Substantial salinity fluctuations in the studied part of the western European epicontinental seas are also inconsistent with modelling results35,45 and thus appear much less plausible than a direct temperature forcing of the oxygen isotope signature.

Despite a gradual return to more positive δ13C values indicating the progressive drawdown of excess atmospheric greenhouse gases into sedimentary organic matter, temperatures remained stable and high. The first sign of a temperature reduction is only seen around the last occurrence of Soaresirhynchia, when δ13C values reached their global maximum. The temperature decrease thus lags several 100 kyr3,46 behind the minimum in δ13C values. A compatible pattern, albeit with less dense data coverage, is observed also in the Portuguese strata (Fig. 2). It therefore appears that at least regionally the T-OAE was associated with a climate shift into which the Earth system was locked.

Model constraints on palaeoenvironmental change

The newly assembled high-fidelity record of palaeoenvironmental proxy data permits the extraction of further Earth system parameters from inversion models such as GEOCARB and GEOCARBSULF47,48 and forward modelling (COPSE, refs. 49,50, supplements). Particular interest is in carbon cycle dynamics, their relation to climate change, and global weathering feedbacks which are intimately linked with atmospheric carbon dioxide levels and temperature.

Inverse modelling

Weathering fluxes can be approximated from palaeotemperature and pCO2 when combined with Toarcian-specific estimates of various tectonic forcings49,50 (Fig. 4; supplements). The combination of these weathering estimates and the measured δ13C data can then be used to derive corresponding estimates of the organic and carbonate carbon burial fluxes as long as inorganic and organic carbon pools are in isotopic equilibrium. At steady state, the fraction of carbon that is buried in reduced form, (i.e., organic carbon) increases with increasing carbonate δ13C. Carbonate δ13C values greater than +3‰ through much of the serpentinum zone can be attributed to such an increased organic matter burial flux. However, given the large-scale perturbation associated with external introduction of 13C-depleted carbon during the T-OAE (e.g., Refs. 3,7,14), it is highly likely that the system deviates from steady state at least at the low point of the negative CIE, compromising the reliability of carbon flux estimates at this point.

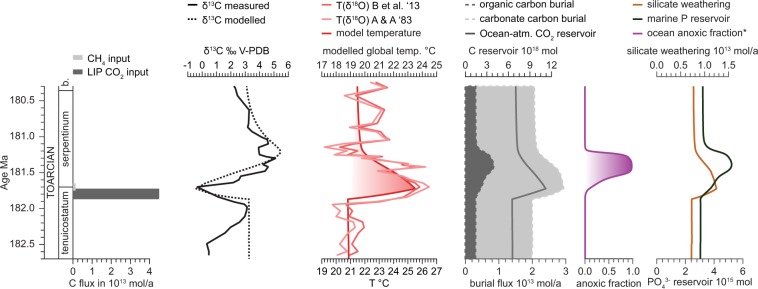

Figure 4.

Modelling results for carbon cycle perturbation, temperature change, weathering and nutrient dynamics as well as intensity of ocean anoxia. Measured δ13C values are shown next to temperature reconstructions using temperature equations of Anderson and Arthur69 and Brand et al.39. The coarse features of the δ13C values are matched by a transient injection of thermogenic CO2 as well as CH4 in the COPSE forward biogeochemical model. *: The representation of the global ocean anoxic fraction depicted is defined as the fraction of the ocean surface area below which the oxygen saturation in the oxygen minimum zone would be below 10%70.

In order to sustain high marine organic carbon burial, limiting nutrients supporting primary production have to be in high supply, and areas subject to ocean anoxia due to the increased oxygen consumption of organic carbon remineralization expanded51. Increased fluxes of elements to the ocean derived from continental weathering are well documented for the T-OAE12,36,37,52 even though timing and magnitude of these fluxes are not unequivocal. The ocean anoxic fraction and the quantities of limiting nutrients, which ultimately derive from such rock weathering, can be approximated using carbon burial flux estimates (supplements).

Important modulations of the Earth system’s response to climate perturbations arise on the basis of two distinct limiting factors on the silicate weathering flux53,54: kinetic factors (i.e., CO2 supply and temperature) versus substrate- related factors (i.e. supply of fresh rock through uplift). If silicate weathering is limited by CO2 then it is intimately connected with atmospheric carbon dioxide and thus planetary temperature via a homeostatic negative feedback55. By contrast, if supply of silicates is insufficient to counterbalance any increase in atmospheric CO2, this will prolong any associated hyperthermal greenhouse interval (and, in this case, any associated OAE). The nature of silicate weathering limitation has consequently been proposed as a key controlling factor on the duration of other hyperthermal intervals56.

Forward biogeochemical modelling

“Forward” biogeochemical models allow reproduction of the observed carbon cycle and climate perturbation of the T-OAE independent of the analysed data. We employ the COPSE (Carbon, Oxygen, Phosphorous, Sulphur, Evolution49,50) box model in order to mimic a carbon cycle perturbation driven by large igneous province (LIP)-derived CO2 and hydrate-derived CH4 (supplements; Fig. 4). Geochemical data extracted from fossils can be matched closely by this approach. Modelling these data provides further constraints on types, timing and magnitude of carbon injection and yields valuable information on the weathering feedback and nutrient supplies at the time36,52,57.

Within the COPSE model, the greenhouse perturbation leads to an increase in the input of phosphorous to the ocean via weathering, which boosts production and therefore the respiratory oxygen demand imposed by remineralization of sinking organic matter. This increases marine anoxia, leading to a reduction in marine phosphate burial which further amplifies organic carbon production, thus creating a short term positive feedback. Over longer timescales, the increase in production also leads to enhanced marine organic carbon burial. This increase in organic carbon burial ultimately causes a compensating increase in the global atmosphere-ocean oxygen reservoir, which may be of sufficient magnitude to create a long-term negative feedback that contributes to the system coming out of the OAE58. This sequence of events is reproduced by the model, and is sufficient to reproduce the coarse features of the δ13C curve when coupled to the carbon isotope equations (see supplement). However, the associated change in the global oxygen reservoir is modest, and CO2 consumption by weathering, relative to the magnitude of the initial greenhouse input, is the main controlling factor on the duration of the OAE.

The timing of anoxia lags behind that of the greenhouse gas input (Fig. 4), consistent with the lag between the lower limit of the δ13C curve and the maximum value of the marine organic carbon burial flux implied by the inversion model. As observed in the fossil δ18O data, the hyperthermal interval also lasts longer than the negative CIE, due to the time needed for weathering to consume the CO2 introduced via the perturbation. The duration of the OAE is ultimately dictated by the time it takes to consume the excess CO2 by silicate weathering, again raising the above issue of supply versus kinetic silicate weathering limitation. Figure 4 represents this using a formulation at which silicate weathering cannot exceed twice its current value (supplements).

The actual threshold at which silicate weathering becomes supply-limited is uncertain, and the formulation in the model relates the theoretical kinetically limited rate to a maximum weathering rate parameter. Some calculations place an upper limit on this maximum value of about 10 times the present rate, on the basis of crustal composition56, whereas lower estimates of c. 3 times the present flux have been derived within Precambrian modelling based on the maximum amount of CO2 consumable by rock flour59. Further empirical data may help determining such controls on the length of OAEs, including the Toarcian, with better reliability, and our model highlights the importance of such data.

Environmental extremes and the faunal response of Soaresirhynchia

Soaresirhynchia is commonly associated with the later part of the T-OAE, and found in the lower serpentinum ammonite zone in western Tethyan sections where black shales are not extensively developed21,22,60. A singular Soaresirhynchia occurrence in the lowermost Toarcian of the Lusitanian Basin has previously been reported by Almeras61 which is here confirmed by rare finds in the tenuicostatum zone in Fonte Coberta (Fig. 2; supplements). These finds may indicate that Soaresirhynchia already partially took hold in the Lusitanian Basin before the T-OAE. This earlier occurrence coincides with the end of the Pliensbachian-Toarcian boundary perturbation, an event that has been described as a significant extinction event and thermal perturbation in its own right9,11,20. The sediments in Fonte Coberta are interpreted to represent deeper water environments than at Barranco de la Cañada21,28. In Fonte Coberta, Soaresirhynchia is found together with two other brachiopod genera showing very similar shell ultrastructure and geochemical composition, pointing at comparable biomineralisation styles, and suggesting that physicochemical conditions at Fonte Coberta aligned better with the ecological requirements of Soaresirhynchia than in basins east of the Iberian Massif (Fig. 3). Indeed, this morphologically simple but variable brachiopod is thought to be a representative of a group of deep water brachiopods that invaded the shallow shelf seas during times of environmental perturbation62.

The reduced isotopic heterogeneity in its shell calcite compared with other Toarcian rhynchonellids from shallow water habitats (Fig. 3) suggests that this genus grew comparatively slowly. Such an interpretation is further supported by the low Sr/Ca and Mg/Ca ratios in its shell (Fig. 3), which in modern brachiopods are preferentially observed for species from habitats below the photic zone30,33. In addition, the reduced shell organic matter content as compared to the shallow water brachiopods at Barranco de la Cañada signifies that Soaresirhynchia secreted shell calcite at very little energy expense63 and thus that metabolic rates were low.

Soaresirhynchia has the coarse shell fibres with isometric cross sections typical of the rhynchonellid superfamily Basilioloidea64, which is thought to thrive in warm waters65. The association of Soaresirhynchia with low palaeolatitudes with only rare finds beyond 35°N in palaeolatitude22,60 further suggests that this genus relied on warm waters. Indeed, its disappearance in the Barranco de la Cañada section is marked by the first indications for a return to cooler palaeotemperatures (Fig. 2). A thermophilic character of this genus, however, seems at odds with its supposed deeper water origin. One might rather hypothesize that Soaresirhynchia could tolerate a wide temperature range and thrive where competition with less well adapted species was reduced or absent26.

The advent of Soaresirhynchia, occupying a large part of western Tethyan shallow shelf seas and ranging far beyond its earliest Toarcian appearance in the Lusitanian Basin has been ascribed to the pioneering repopulation after severe benthic turnover of the T-OAE22,66. However, considering the protracted hyperthermal conditions along with major changes in ocean chemistry caused by expanded anoxia elsewhere in the global ocean and increased continental weathering fluxes36,67, one should not equate this repopulation phase with a return to normal environmental conditions. Besides the ability of Soaresirhynchia to withstand high temperatures it could also survive in seawater characterized by substantial changes in ion content, having been depleted in sulphate52,68 and enriched in nutrients36,37 (Fig. 4) as a consequence of the T-OAE. The observed faunal turnover in brachiopods across the T-OAE may serve as an analogue for similar scenarios of faunal changes that are possible outcomes of ongoing alterations in climate and oceanic nutrient balance51. Shallow marine environments might become occupied by similarly unlikely survivors, calling for particular study and conservation of deeper water faunas.

Conclusions

Well-preserved benthic macrofossils from Toarcian strata of Portugal and Spain allow for the reconstruction of palaeoenvironmental conditions during the early Toarcian in unprecedented detail. The negative carbon isotope excursion of the T-OAE is constrained to a magnitude of c. 4.2‰. The associated palaeotemperature rise of c. 3.5 °C lasted until carbon isotope ratios recovered to maximum values in the studied sections.

Modelling of the newly generated data suggests that the carbon cycle perturbation of the T-OAE could have been caused by the injection of carbon primarily derived from the interaction of large igneous province volcanism with sedimentary organic matter and methane, leading to an approximately doubled atmospheric pCO2. The prolonged duration of the thermal perturbation associated with the T-OAE is likely to have been controlled primarily by the silicate weathering flux, making the distinction between silicate supply versus kinetic components of this flux during this and other OAEs an important focus for future research.

The rhynchonellid brachiopod genus Soaresirhynchia occurs abundantly during the rising limb of the T-OAE negative carbon isotope excursion, an interval characterised by persisting elevated temperatures. New geochemical and microscopic data corroborate that this genus likely originated in deeper water habitats. Its success during the stressful conditions of the early Toarcian can be linked to its ability to tolerate hot temperatures and its inferred low metabolic rates.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Friedrich Lucassen (Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen) is thanked for joint fieldwork. This study received funding from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant DFG AB 09/10–1 and the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NE/N018508/1). It forms part of the Research Unit TERSANE (FOR 2332: Temperature‐related Stressors as a Unifying Principle in Ancient Extinctions). This work is also a contribution to the IGCP-655 (IUGS-UNESCO: Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event: Impact on Marine Carbon Cycle and Ecosystems) and the Early Jurassic Earth System and Timescale (JET) project. We thank Juan Carlos García and the Dirección General de Cultura y Patrimonio (Gobierno de Aragon, Zaragoza) for authorizing field work and José Ignacio Canudo (Universidad de Zaragoza) for the loan of specimens.

Author contributions

M.A. conceived of the project; L.V.D., V.P., M.A. & T.K. conducted field work;V.P. & M.A. described the fossil material taxonomically; C.V.U. extracted fossil shell material, conducted SEM work and geochemical analyses on fossil calcite; S.K. & T.K. conducted bulk rock geochemical analyses; R.B. and T.L. carried out the modelling; C.V.U. led writing of the study with input from R.B., L.V.D., S.P.H., S.K., T.K., T.L., V.P., and M.A.

Data availability

All geochemical data pertaining to this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files). SEM images of shell ultrastructures are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Fossil specimens from the Fonte Conberta/Rabaçal sections are curated and archived in the Museum für Naturkunde, Leibniz Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity Science, Berlin, Germany. Studied specimens from the Barranco de la Cañada section are curated and archived in the Museu de Ciencias Naturales, Zaragoza, Spain.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-63487-6.

References

- 1.Hesselbo SP, Jenkyns HC, Duarte LV, Oliveira LCV. Carbon-isotope record of the Early Jurassic (Toarcian) Oceanic Anoxic Event from fossil wood and marine carbonate (Lusitanian Basin, Portugal) Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 2007;253:455–470. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2006.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suan G, van de Schootbrugge V, Adatte T, Fiebig J, Oschmann W. Calibrating the magnitude of the Toarcian carbon cycle perturbation. Paleoceanography. 2015;30(5):495–509. doi: 10.1002/2014PA002758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kemp DB, Coe AL, Cohen AS, Schwark L. Astronomical pacing of methane release in the Early Jurassic. Nature. 2005;437:396–399. doi: 10.1038/nature04037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermoso M, et al. Dynamics of a stepped carbon-isotope excursion: Ultra high-resolution study of Early Toarcian environmental change. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 2012;319–320:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2011.12.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suan G, Mattioli E, Pittet B, Mailliot S, Lécuyer C. Evidence for major environmental perturbation prior to and during the Toarcian (Early Jurassic) oceanic anoxic event from the Lusitanian Basin, Portugal. Paleoceanography. 2008;23:PA1202. doi: 10.1029/2007PA001459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ullmann CV, Thibault N, Ruhl M, Hesselbo SP, Korte C. Effect of a Jurassic oceanic anoxic event on belemnite ecology and evolution. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111(28):10073–10076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320156111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jenkyns HC, Jones CE, Gröcke DR, Hesselbo SP, Parkinson DN. Chemostratigraphy of the Jurassic System: applications, limitations and implications for palaeoceanography. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 2002;159:351–378. doi: 10.1144/0016-764901-130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickson AJ, et al. Molybdenum-isotope chemostratigraphy and paleoceanography of the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (Early Jurassic) Paleoceanography. 2017;32:813–829. doi: 10.1002/2016PA003048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Littler K, Hesselbo SP, Jenkyns HC. A carbon-isotope perturbation at the Pliensbachian-Toarcian boundary: evidence from the Lias Group, NE England. Geol. Mag. 2010;147(2):181–192. doi: 10.1017/S0016756809990458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pálfy J, Smith PL. Synchrony between Early Jurassic extinction, oceanic anoxic event, and the Karoo-Ferrar flood basalt volcanism. Geology. 2000;28(8):747–750. doi: 10.1130/0091-7613(2000)28<747:SBEJEO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caruthers AH, Smith PL, Gröcke DR. The Pliensbachian-Toarcian (Early Jurassic) extinction, a global multi-phased event. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 2013;386:104–118. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Percival LME, et al. Osmium isotope evidence for two pulses of increased continental weathering linked to Early Jurassic volcanism and climate change. Geology. 2016;44(9):759–762. doi: 10.1130/G37997.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu W, et al. Magnetostratigraphy of the Toarcian Stage (Lower Jurassic) of the Llanbedr (Mochras Farm) Borehole, Wales: basis for a global standard and implications for volcanic forcing of palaeoenvironmental change. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 2018;175:594–604. doi: 10.1144/jgs2017-120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hesselbo SP, et al. Massive dissociation of gas hydrate during a Jurassic oceanic anoxic event. Nature. 2000;406:392–395. doi: 10.1038/35019044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Them TR, II, et al. High-resolution carbon isotopes records of the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (Early Jurassic) from North America and implications for the global drivers of the Toarcian carbon cycle. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 2017;459:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2016.11.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruebsam W, Mayer B, Schwark L. Cryosphere dynamics control early Toarcian global warming and sea level evolution. Global Planet. Change. 2019;172:440–453. doi: 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2018.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McArthur JM, Donovan DT, Thirlwall MF, Fouke BW, Mattey D. Strontium isotope profile of the early Toarcian (Jurassic) oceanic anoxic event, the duration of ammonite biozones, and belemnite palaeotemperatures. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 2000;179:269–285. doi: 10.1016/S0012-821X(00)00111-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suan G, et al. Secular environmental precursors to Early Toarcian (Jurassic) extreme climate changes. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 2010;290:448–458. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2009.12.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu W, et al. Carbon sequestration in an expanded lake system during the Toarcian oceanic anoxic event. Nat. Geosci. 2018;10:129–135. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little CTS, Benton MJ. Early Jurassic mass extinction: A global long-term event. Geology. 1995;23(6):495–498. doi: 10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023<0495:EJMEAG>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gahr ME. Response of Lower Toarcian (Lower Jurassic) macrobenthos of the Iberian Peninsula to sea lever changes and mass extinction. J. Iber. Geol. 2005;31(2):197–215. [Google Scholar]

- 22.García Joral F, Gómez JJ, Goy A. Mass extinction and recovery of the Early Toarcian (Early Jurassic) brachiopods linked to climate change in Northern and Central Spain. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 2011;302:367–380. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.01.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danise S, Twitchett RJ, Little CTS, Clémence M-E. The impact of global warming and anoxia on marine benthic community dynamics: an example from the Toarcian (Early Jurassic) Plos One. 2013;8(2):e56255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caswell BA, Dawn SJ. Recovery of benthic communities following the Toarcian oceanic anoxic event in the Cleveland Basin, UK. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 2019;521:114–126. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.02.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bailey TR, Rosenthal Y, McArthur JM, van de Schootbrugge B, Thirlwall MF. Paleoceanographic changes of the Late Pliensbachian-Early Toarcian interval: a possible link to the genesis of an Oceanic Anoxic Event. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 2003;212:307–320. doi: 10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00278-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danise S, et al. Stratigraphic and environmental control on marine benthic community change through the early Toarcian extinction event (Iberian Range, Spain) Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 2019;524:183–200. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.03.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piazza V, Duarte LV, Renaudie J, Aberhan M. Reductions in body size of benthic macroinvertebrates as a precursor of the early Toarcian (Early Jurassic) extinction event in the Lusitanian Basin, Portugal. Paleobiology. 2019;45(2):296–316. doi: 10.1017/pab.2019.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.García Joral F, Baeza-Carratalá JF, Goy A. Changes in brachiopod body size prior to the Early Toarcian (Jurassic) mass extinction. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 2018;506:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2018.06.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clapham ME, et al. Assessing the ecological dominance of Phanerozoic marine invertebrates. Palaios. 2006;21:431–441. doi: 10.2110/palo.2005.P05-017R. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brand U, Logan A, Hiller N, Richardson J. Geochemistry of modern brachiopods: applications and implications for oceanography and paleoceanography. Chem. Geol. 2003;198:305–334. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2541(03)00032-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hesselbo SP, Pienkowski G. Stepwise atmospheric carbon-isotope excursion during the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (Early Jurassic, Polish Basin) Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 2011;301:365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2010.11.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parkinson D, Curry GB, Cusack M, Fallick AE. Shell structure, patterns and trends of oxygen and carbon stable isotopes in modern brachiopod shells. Chem. Geol. 2005;219:193–235. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2005.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ullmann CV, Frei R, Korte C, Lüter C. Element/Ca, C and O isotope ratios in modern brachiopods: Species-specific signals of biomineralization. Chem. Geol. 2017;460:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2017.03.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dickens GR, O’Neill JR, Rea DK, Owen RM. Dissociation of oceanic methane as the cause of the carbon isotopic excursion at the end of the Paleocene. Paleoceanography. 1995;10(6):965–971. doi: 10.1029/95PA02087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dera G, Donnadieu Y. Modelling evidences for global warming, Arctic seawater freshening, and sluggish oceanic circulation during the Early Toarcian anoxic event. Paleoceanography. 2012;27:PA2211. doi: 10.1029/2012PA002283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brazier J-M, et al. Calcium isotope evidence for dramatic increase of continental weathering during the Toarcian oceanic anoxic event (Early Jurassic) Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 2015;411:164–176. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2014.11.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jenkyns HC. Geochemistry of oceanic anoxic events. Geochem. Geophys. Geosy. 2010;11(3):Q03004. doi: 10.1029/2009GC002788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Korte C, et al. Jurassic climate mode governed by ocean gateway. Nature Commun. 2015;6:10015. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brand U, et al. Oxygen isotopes and MgCO3 in brachiopod calcite and a new paleotemperature equation. Chem. Geol. 2013;359:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duarte LV. Facies analysis and sequential evolution of the Toarcian-Lower Aalenian series in the Lusitanian Basin (Portugal) Comun. Inst. Geol. e Mineiro. 1997;83:65–94. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pittet B, Suan G, Lenoir F, Duarte LV, Mattioli E. Carbon isotope evidence for sedimentary discontinuities in the lower Toarcian of the Lusitanian bains (Portugal): Sea level change at the onset of the Oceanic Anoxic Event. Sediment. Geol. 2014;303:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.sedgeo.2014.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McArthur JM, Algeo TJ, van de Schootbrugge B, Li Q, Howarth RJ. Basinal restriction, black shales, Re-Os dating, and the Early Toarcian (Jurassic) oceanic anoxic event. Paleoceanography. 2008;23:PA4217. doi: 10.1029/2008PA001607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harazim D, et al. Spatial variability of watermass conditions within the European Epicontinental Seaway during the Early Jurassic (Pliensbachian-Toarcian) Sedimentology. 2013;60:359–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3091.2012.01344.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ager DV. Brachiopod palaeoecology. Earth-Sci. Rev. 1967;3:157–179. doi: 10.1016/0012-8252(67)90375-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bjerrum C, Surlyk F, Callomon JH, Slingerland RL. Numerical Paleoceanographic Study of the Early Jurassic Transcontinental Laurasian Seaway. Paleoceanography. 2001;16:390–404. doi: 10.1029/2000PA000512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang C, Hesselbo SP. Pacing of the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event (Early Jurassic) from astronomical correlation of marine sections. Gondwana Res. 2014;25:1348–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2013.06.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berner RAG., II A revised model of atmospheric CO2 over geologic time. Am. J. Sci. 1994;294:55–91. doi: 10.2475/ajs.294.1.56. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Royer DL, Donnadieu Y, Park J, Kowalczyk J, Godderis Y. Error analysis CO2 and O2 estimates from the long-term geochemical model Geocarbsulf. Am. J. Sci. 2014;314:1259–1284. doi: 10.2475/09.2014.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bergman NM, Lenton TM, Watson AJ. COPSE: a new model of biogeochemical cycling over Phanerozoic time. Am. J. Sci. 2004;304:397–437. doi: 10.2475/ajs.304.5.397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lenton TM, Daines SJ, Mills BM. COPSE reloaded: An improved model of biogeochemical cycling over Phanerozoic time. Earth Sci. Rev. 2018;178:1–28. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watson AJ, Lenton TM, Mills BJW. Ocean deoxygenation, the global phosphorus cycle and the possibility of human-caused large-scale ocean anoxia. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2017;375:20160318. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2016.0318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gill BC, Lyons TW, Jenkyns HC. A global perturbation to the sulfur cycle during the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 2011;312:484–494. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2011.10.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.West AJ, Galy A, Bickle MJ. Tectonic and climate control on silicate weathering. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 2008;235:211–238. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2005.03.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.West AJ. Thickness of the chemical weathering zone and implications for erosional and climatic drivers of weathering and for carbon-cycle feedbacks. Geology. 2012;40:811–814. doi: 10.1130/G33041.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walker JCG, Hays PB, Kasting JF. A negative feedback mechanism for the long-term stabilization of Earth’s surface temperature. J. Geophys. Res. 1981;86(C10):9776–9782. doi: 10.1029/JC086iC10p09776. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kump LR. Prolonged Late Permian early Triassic hyperthermal: Failure of climate regulation? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2018;376:20170078. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2017.0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Them TR, et al. Evidence for rapid weathering response to climatic warming during the Toarcian Oceanic Anoxic Event. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:5003. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05307-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Cappellen P, Ingall ED. Benthic phosphorus regeneration, net primary production, and ocean anoxia: a model of the coupled marine biogeochemical cycles of carbon and phosphorus. Paleoceanography. 1994;9:677–692. doi: 10.1029/94PA01455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mills BJW, Watson AJ, Goldblatt C, Boyle RA, Lenton TML. Timing of Neoproterozoic glaciations linked to transport-limited global weathering. Nat. Geosci. 2011;4:861–864. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Comas-Rengifo MJ, et al. Latest-Pliensbachian-Early Toarcian brachiopod assemblages from the Peniche section (Portugal) and their correlation. Episodes. 2015;38:2–8. doi: 10.18814/epiiugs/2015/v38i1/001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alméras, Y. Le genre Soaresirhynchia nov. (Brachiopoda, Rhynchonellacea, Wellerellidae) dans le Toarcien du sous-bassin nord-lusitanien (Portugal) (No. 130). Centre des sciences de la terre, Université Claude-Bernard-Lyon I (1994).

- 62.Vörös A. The smooth brachiopods of the Mediterranean Jurassic: Refugees or invaders? Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 2005;223:222–242. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Palmer AR. Relative cost of producing skeletal organic matrix versus calcification: evidence from marine gastropods. Mar. Biol. 1983;75:287–292. doi: 10.1007/BF00406014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Radulović B, Motchurova-Dekova N, Radulović V. New Barremian rhynchonellide brachiopod genus from Serbia and the shell microstructure of Tetrarhynchiidae. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 2007;52(4):761–782. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smirnova TN. Early Cretaceous rhynchonellids of Dagestna: system, morphology, stratigraphic and paleobiogeographic significance. Paleontolog. J. 2012;46(11):1197–1296. doi: 10.1134/S0031030112110019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baeza-Carratalá JF, Reolid M, García Joral F. New deep-water brachiopod resilient assemblage from the South-Iberian Palaeomargin (Western Tethys) and its significance for the brachiopod adaptive strategies around the Early Toarcian Mass Extinction Event. B. Geosci. 2017;92(2):233–256. doi: 10.3140/bull.geosci.1631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jones MT, Jerram DA, Svensen HH, Grove C. The effects of large igneous provinces on the global carbon and sulphur cycles. Palaeogeogr. Palaeocl. 2016;441:4–21. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.06.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Newton RJ, et al. Low marine sulfate concentrations and the isolation of the European epicontinental sea during the Early Jurassic. Geology. 2011;39(1):7–10. doi: 10.1130/G31326.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Anderson, T. F. & Arthur, M. A. Stable isotopes of oxygen and carbon and their application to sedimentologic and palaeoenvironmental problems, Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists Short Course 10, I.1-I-151 (1983).

- 70.Handoh IC, Lenton TM. Periodic mid-Cretaceous oceanic anoxic events linked by oscillations of the phosphorus and oxygen biogeochemical cycles. Global Biogeochem. Cy. 2003;17(4):1092. doi: 10.1029/2003GB002039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thierry, J. et al. (eds.). Atlas Peri-Tethys. Palaeogeographical Maps, 1–97 (2000).

- 72.Ruebsam, W., Müller, T., Kovács, Pálfy, J. & Schwark, L. Environmental response to the early Toarcian carbon cycle and climate perturbations in the northeastern part of the West Tethys shelf. Gondwana Res. 59, 144–158, 10.1016/j.gr.2018.03.013 (2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All geochemical data pertaining to this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files). SEM images of shell ultrastructures are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Fossil specimens from the Fonte Conberta/Rabaçal sections are curated and archived in the Museum für Naturkunde, Leibniz Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity Science, Berlin, Germany. Studied specimens from the Barranco de la Cañada section are curated and archived in the Museu de Ciencias Naturales, Zaragoza, Spain.