Abstract

M1 aminopeptidase enzymes are a diverse family of metalloenzymes characterized by conserved structure and reaction specificity. Excluding viruses, M1 aminopeptidases are distributed throughout all phyla, and have been implicated in a wide range of functions including cell maintenance, growth and development, and defense. The structure and catalytic mechanism of M1 aminopeptidases are well understood, and make them ideal candidates for the design of small‐molecule inhibitors. As a result, many research groups have assessed their utility as therapeutic targets for both infectious and chronic diseases of humans, and many inhibitors with a range of target specificities and potential therapeutic applications have been developed. Herein, we have aimed to address these studies, to determine whether the family of M1 aminopeptidases does in fact present a universal target for the treatment of a diverse range of human diseases. Our analysis indicates that early validation of M1 aminopeptidases as therapeutic targets is often overlooked, which prevents the enzymes from being confirmed as drug targets. This validation cannot be neglected, and needs to include a thorough characterization of enzymes’ specific roles within complex physiological pathways. Furthermore, any chemical probes used in target validation must be carefully designed to ensure that specificity over the closely related enzymes has been achieved. While many drug discovery programs that target M1 aminopeptidases remain in their infancy, certain inhibitors have shown promise for the treatment of a range of conditions including malaria, hypertension, and cancer.

Keywords: anti‐cancer, anti‐malarial, drug discovery, inhibitors, M1 aminopeptidase

The large family of therapeutically interesting M1 aminopeptidase enzymes has enormous potential to provide important drug targets. However, conservation of sequence, structure, and substrate specificity results in substantial challenges, and necessitates the need for careful target validation. Some studies have achieved this, and successfully validated M1 aminopeptidases as targets for the treatment of malaria, hypertension, and cancer.

Abbreviations

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- APA

human aminopeptidase A

- APN

human aminopeptidase N

- EcAPN

Escherichia coli aminopeptidase N

- ERAP

endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase

- IRAP

insulin‐regulated aminopeptidase

- LTA4H

leukotriene A4 hydrolase

- NmAPN

Neisseria meningitidis aminopeptidase N

- PfA‐M1

Plasmodium falciparum M1 aminopeptidase

Introduction

Aminopeptidases constitute a diverse set of protease enzymes with essential roles in a wide range of cellular functions. The enzymes catalyze the removal of amino acids from the N terminus of polypeptides; the specific residues for which they show affinity, as well as their structure, determine their subdivision into families. The large family of M1 aminopeptidase enzymes (clan MA, family M1) are zinc‐dependent enzymes characterized by the presence of two conserved, catalytic sequence motifs; a consensus zinc‐binding motif (HEXXH‐(X18)‐E) and the ‘GXMEN’ exopeptidase motif 1, 2.

Excluding viruses, M1 aminopeptidases are distributed throughout all phyla, and have been implicated in a wide range of functions including cell maintenance, growth and development, and defense. Their wide range of essential functions in combination with their presence in such a wide distribution of organisms illustrates the importance of the family, and has led many research groups to assess their utility as therapeutic targets for both infectious and chronic diseases of humans. The result of this is an enormous field of study assessing the function, structure, and inhibition of M1 aminopeptidases in a range of organisms, each of which is often portrayed as a novel therapeutic target. In this review, we aim to examine this field and address the formidable question: do M1 aminopeptidases really constitute an entire family of therapeutic drug targets? We cannot attempt to summarize this field in a single review, nor is that our intention. Rather, we have focused on recent research articles, and where applicable, made reference to other more comprehensive reviews. Specifically, we have examined the potential of M1 aminopeptidases as therapeutic drug targets by assessing (1) whether the characterized enzyme plays a validated role in the health and disease of humans, and (2) if their activity can be modulated to affect a human disease state.1 The M1 aminopeptidases that we have discussed in the text are summarized in Table 1. We hope that this review stimulates further evaluation and discussion of the field, and addresses how those of us within the field can best utilize the available resources to progress toward the ultimate goal of developing novel therapeutics to treat human disease.

Table 1.

M1 Aminopeptidases that have been investigated as targets for treatment of human disease

| M1 Aminopeptidase | Characterized physiological role | Potential therapeutic indication | Proposed therapeutic strategy: small‐molecule or vaccine target? | Experimental evidence supporting strategy | Available structural informationa (RCSB PDB deposition IDs provided) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogenic infections | |||||

| EcAPN | Likely role within nutrient acquisition and metabolic pathways 11 | Antibacterial | Small‐molecule inhibitors | Not available | Many (> 20) crystal structures available including unliganded (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=2HPO) and liganded (product or inhibitor) |

| NmAPN | Likely role within nutrient acquisition and metabolic pathways 18 | Antibacterial | Small‐molecule inhibitors | Not available | Crystal structure of unliganded NmAPN (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=2GTQ), and multiple liganded structures (inhibitor or product analog) |

| Brucella spp. PepN | Unknown, investigation limited to diagnostic antigen 37 | Brucellosis | Vaccine target | Not validated yet. Protein is immunogenic 38 | None available |

| C. parvum M1 | Possible role in excystation 39 | Cryptosporidiosis | Vaccine target | Not validated yet. Protein is immunogenic 39 | None available |

| T. gondii M1 | Unknown, investigation thus far limited to immunogenicity 24 | Toxoplasmosis | Vaccine target | Not validated yet. Protein is immunogenic 24 | None available |

| PfA‐M1 | Hemoglobin digestion by Plasmodium spp. within intraerythrocytic parasites 26 | Malaria | Small‐molecule inhibitors | In vitro and in vivo control of Plasmodium spp. (P. falciparum in vitro and P. chaubaudi chabaudi in vivo) 27, 28, 33 | Many (> 20) crystal structures available including unliganded (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=3EBG) and inhibitor‐bound |

| AnAPN1 | Mediates parasite cell adhesion in mosquito midgut 41 | Malaria | Vaccine target | In vivo transmission block of P. falciparum and P. vivax parasites within anopheline species 42 | Crystal structure of unliganded AnAPN1 (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=4WZ9) |

| APN | Human cell entry receptor for some enveloped, plus‐RNA coronaviruses (CoV) 44 | Antiviral | Vaccine to target CoV and prevent the interaction with APN | Neutralizing antibody blocks viral entry 45 | Crystal structure of the porcine respiratory CoV spike receptor‐binding domain bound to the pAPN ectodomain (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=4F5C) |

| Chronic diseases of humans | |||||

| APA | Regulation of blood pressure within the brain renin–angiotensin system 46 | Hypertension | Small‐molecule inhibitors | Inhibitors of APA block the formation of AngIII in the brain, and normalize blood pressure in hypertensive rats 50, 51 | Crystal structures of APA in a range of forms including unliganded (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=4KX7), inhibitor‐bound (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=4KX8, http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=4KXB), and product‐bound in the presence and absence of Ca+2 (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=4KX9, http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=4KXA, http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=4KXC, http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=4KXD) |

| LTA4H | Bifunctional role in inflammation: anti‐inflammatory (breakdown of PGP) and proinflammatory (synthesis of leukotriene B4) 54, 55 | Inflammatory disease | Small‐molecule inhibitors |

Inhibition of LTA4H by Bufexamac alleviates lipopolysaccharide‐induced acute lung injury in mouse models 58. Selective inhibition of leukotriene B4 synthesis achieved with ARM1 56 |

Many (> 50) crystal structures available including liganded (inhibitor, product, and substrate analog) and unliganded forms |

| APN | Involved in a wide range of processes that include processing neuropeptides and chemokines, cell adhesion, and endocytosis 3 | Chemotherapeutic | Small‐molecule inhibitors | APN inhibitors in clinical use 3 | Crystal structure of unliganded APN available (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=45YQ), as well as inhibitor‐bound form (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=4FYR, http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=4FYT) and product‐bound form (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=4FYS) |

| ERAP1, ERAP2 and IRAP | Processing antigenic peptides for presentation to T‐cells 71, 72 | Immunomodulation | Small‐molecule inhibitors (partial or complete inhibition) | Inhibition of all three enzymes by phosphinic acids (e.g., DG013A) increases cytotoxic response in murine cell lines 70 | ERAP1: Crystal structure of unliganded form in open conformation (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=3QNF), and bestatin‐bound form in both closed (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=2DY0) and opened conformations (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=3MDJ) |

| ERAP2: Crystal structures of ERAP2 in unliganded, metal‐free conformation (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=5CU5), as well as bound to product (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=5AB2, http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=3SE6), substrate analog (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=5AB0), and inhibitor (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=4JBS) | |||||

| IRAP: Crystal structure of IRAP in unliganded conformation (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=5C97) as well as bound to substrate analog (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=4Z7I), and product (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=4P8Q, http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/search/structidSearch.do?structureId=4PJ6) | |||||

PDB code for the unliganded form only is provided when the number of available structures exceeds 10.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Structure and tools for drug discovery

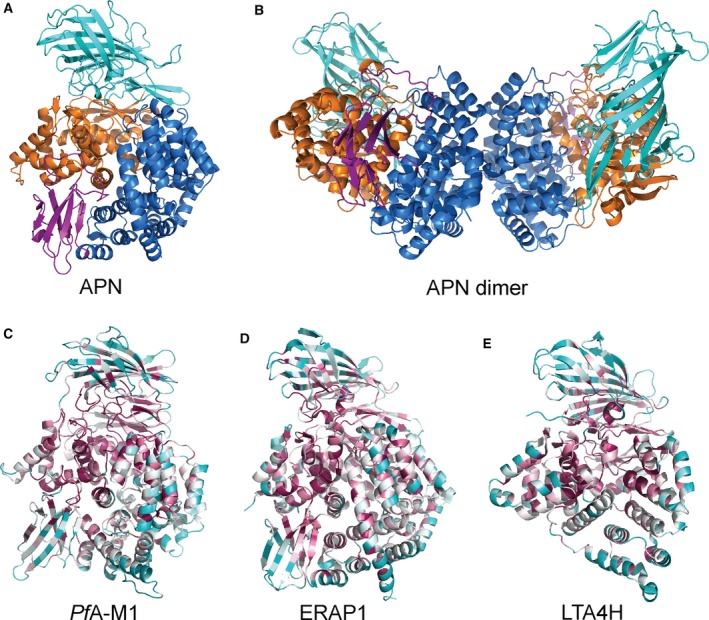

As of September 2016, the International Protein Databank contained 17 unique structures of M1 aminopeptidases from archaea, fungi, bacteria, and animals, which provides a wealth of structural information to aid our examination of the family. M1 aminopeptidases exist as monomers and/or dimers (Fig. 1A,B), are generally membrane bound, and can be found surface‐exposed or within the cytoplasm 3, 4. The general structure comprises a short tail from the transmembrane anchor/stalk and a large ectodomain with a conserved 3–4 domain fold (Fig. 1C–E) 5.

Figure 1.

Structure and conservation of M1 aminopeptidases. (A) X‐ray crystal structure of human aminopeptidase N (APN) 7 colored according to domains with domain I in teal, domain II in orange, domain III in magenta, and domain IV in blue. (B) Crystallographically observed dimer of APN, that is also proposed to occur on the cell surface membrane 7 to which APN is attached via domain I (teal). Domains colored as in A. (C–E) Characteristic structures of M1 aminopeptidases colored according to sequence conservation (high degree of conservation in purple, average in white, and low in cyan). Sequence alignments and conservation calculations performed using ConSurf http://consurf.tau.ac.il/2016/ 83): (C) the M1 aminopeptidase from P. falciparum (PfA‐M1) 27, (D) human endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 (ERAP1) 75, (E) human leukotriene A4 hydrolase (LTA4H) 6.

The N‐terminal domain I has a β‐sheet core which, while largely solvent‐exposed, contains a hydrophobic region that links to a membrane‐spanning anchor 5. The thermolysin‐like catalytic domain II contains the active site flanked by a mixed β‐sheet and α‐helical structure that is highly conserved throughout the family. Within the active site, the catalytic zinc ion is coordinated by Nϵ2 atoms of two conserved histidine residues, the carboxyl Oϵ atom of the glutamate and a nucleophilic water molecule 5. Domain III is composed of an immunoglobulin‐like fold and is completely absent in some family members, such as leukotriene A4 hydrolase (LTA4H; Fig. 1E) 6. The C−terminal domain IV is the most variable region of the protein family and is completely helical in nature, arranged to cap the active site and sequester it from bulk solvent. Domain IV is also involved in dimerization, primarily in mammalian forms 5, 7, 8, 9.

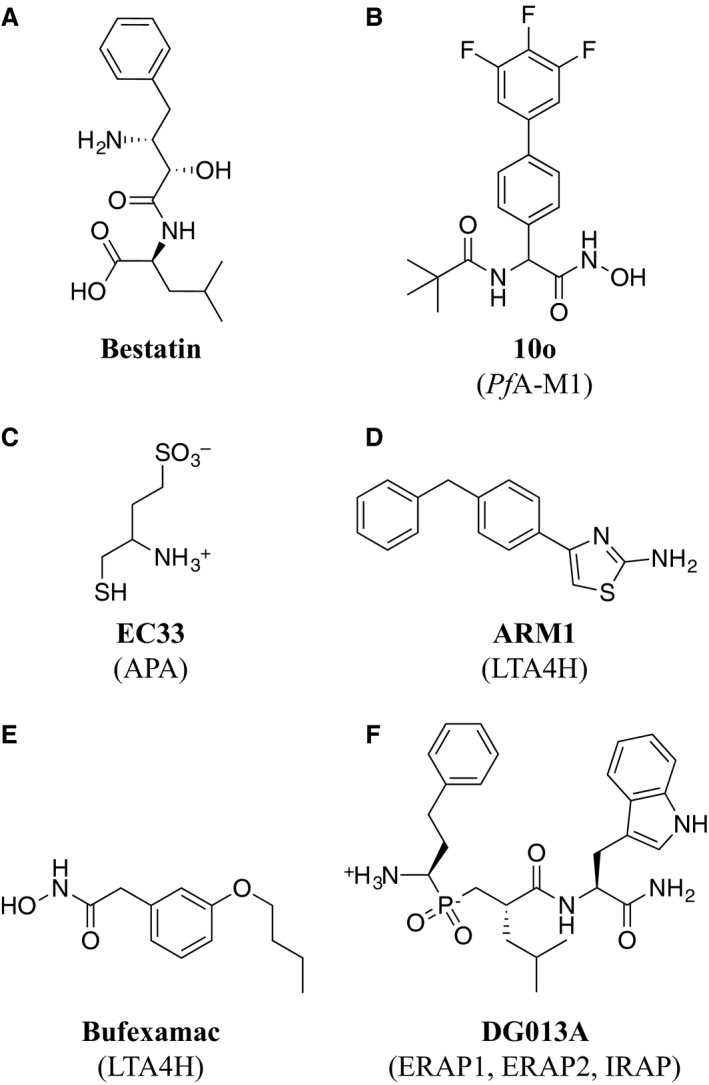

The ready availability of M1 aminopeptidase structures, a well‐defined active site amenable to binding of small molecules, and well characterized reaction mechanisms, make M1 aminopeptidases ideal candidates for the application of structure‐guided inhibitor discovery. Such programs are supported by the ready availability of generic aminopeptidase inhibitors, which can be used to assess the effect of aminopeptidase inhibition in cell culture or animal models. For example, bestatin (Fig. 2A), a pseudodipeptide originally isolated from Streptomyces olivoreticuli as an immunomodulating agent 10, generally demonstrates moderate inhibitory activity against M1 aminopeptidases. However, it should be noted that these generic inhibitors often show activity against other aminopeptidase families. With such a wealth of broadly applicable tools, it is therefore no surprise that many studies have used a combination of cell‐ and structure‐based methods to explore M1 aminopeptidases as potential therapeutic targets.

Figure 2.

Small‐molecule inhibitors of M1 aminopeptidases that are discussed in the text. (A) Bestatin, a generic aminopeptidase inhibitor. (B) 10o, a PfA‐M1 inhibitor. (C) EC33, an APA inhibitor. (D) ARM1, a selective inhibitor of LTA4H epoxide activity. (E) Bufexamac, a LTA4H inhibitor. (F) DG013A, an inhibitor of ERAP1, ERAP2, and IRAP.

Pathogenic infections

The identification of a single, essential protein in a pathogenic organism that is amenable to inhibition by small molecules is the holy grail of drug discovery in infectious disease. Therefore, if M1 aminopeptidases are in fact essential to the survival of a range of pathogenic organisms, they are ideal targets for drug discovery. Infectious diseases of humans can be caused by bacteria, parasites, viruses, fungi, and in rare cases, archaea. Viruses do not possess M1 aminopeptidases and the remaining microbes use them primarily within nutrient acquisition and metabolic pathways 11. While M1 aminopeptidases from fungi have been identified 1, 2, there is no evidence to date that they constitute potential targets for antifungal therapeutics.

Bacterial diseases

Zinc‐dependent proteases are often discussed with regard to the design of new antibiotics 12. There is tremendous information regarding the cloning, purification, and biochemical characterization of many such zinc proteases from both gram‐positive and gram‐negative pathogens, however, few inhibitors have been assessed for potential antimicrobial activity. This observation extends to inhibitors specific for M1 aminopeptidases; the bacterial members are often promoted as potential drug targets, but there is currently no definitive evidence to validate this assertion. Bestatin shows only moderate antimicrobial activity 13, 14, 15, and there have been no reports of bestatin‐sensitive bacteria that contain an M1 family aminopeptidase. The Escherichia coli Aminopeptidase N (EcAPN), has been studied in detail and like most bacterial M1s, is not essential for bacterial survival 16. EcAPN is involved in ATP‐dependent downstream processing during cytosolic protein degradation, however, there appears to be redundant peptidases which likely accounts for its nonessential nature 11.

Although M1 aminopeptidases are not suitable as targets for broad‐spectrum antibiotics, the M1 aminopeptidase from Neisseria meningitidis, NmAPN, has been described in the literature as a potential drug target for the treatment of meningitis. Early work to produce the X‐ray crystal structure arose from a structural genomics initiative, and therapeutic utility was extrapolated from reports describing aminopeptidases from pathogenic bacteria as potential drug targets 17. Extensive substrate profiling experiments characterized NmAPN as possessing a preference for bulky basic and hydrophobic ligands 18, and a subsequent inhibitor development initiative produced selective compounds with low micromolar potency 19. However, despite these advances in understanding the enzyme mechanism of activity and inhibition, there is no published literature to support the hypothesis that NmAPN is a valid drug target. Indeed, we were unable to find any literature assessing the efficacy of NmAPN inhibitors in controlling N. meningitidis growth or infection.

Parasitic diseases

Many proteases have been implicated in the development, virulence and pathogenesis of parasites (for recent review, see 20), and aminopeptidases have been evaluated as potential vaccine candidates or drug targets for Fasciola hepatica 21, Leishmania donovani 22, and Trypanosoma cruzi 23. However, only a small selection of M1 aminopeptidases have been examined. The M1 aminopeptidases from Toxoplasma gondii 24 and the animal pathogen, Trypanosoma congolense, 25 have both been characterized as immunogenic, but their potential as targets for small‐molecule inhibitors has not been investigated. The only parasite M1 aminopeptidase that has been extensively evaluated as a potential drug target is PfA‐M1 from Plasmodium falciparum, the causative agent of malaria.

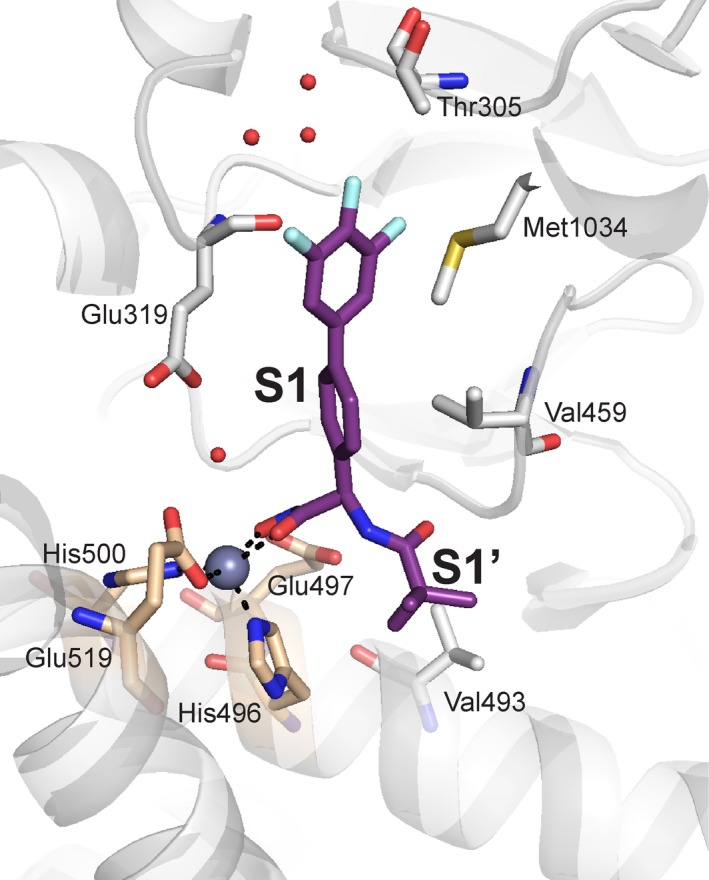

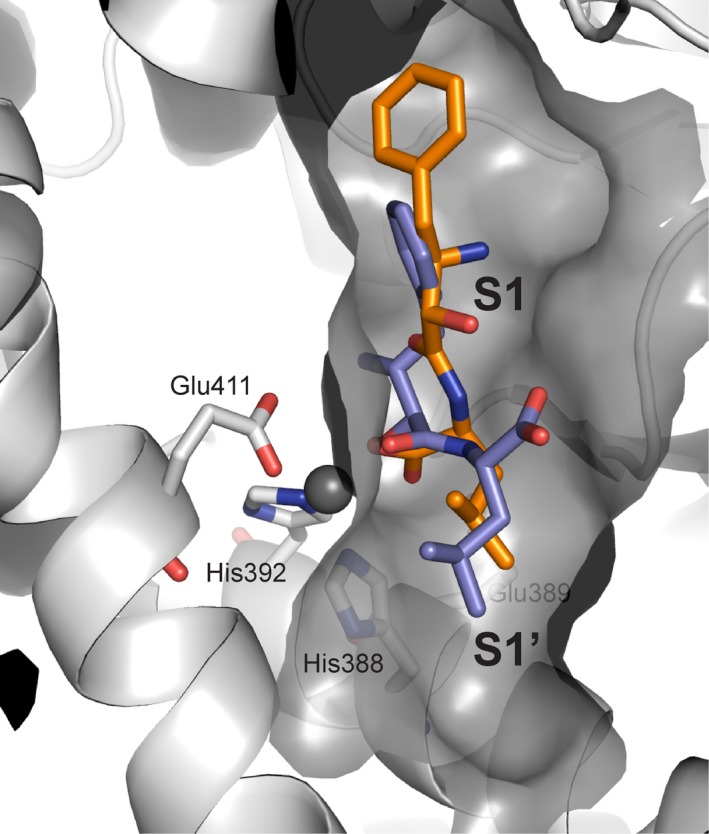

PfA‐M1 is involved in the final stage of the digestion of human hemoglobin, the removal of N‐terminal residues from short peptides, which provides free amino acids for incorporation into parasite proteins 26. There is only a single gene encoding PfA‐M1 in P. falciparum, and attempts to knockout the gene have been unsuccessful, suggesting an essential role for PfA‐M1 in parasite viability 26, 27. This observation was further supported by a chemical genetics approach that showed that the absence of M1 aminopeptidase activity resulted in parasite death 28. Agents that inhibit PfA‐M1 activity in parasites have been shown to control both laboratory (P. falciparum) 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 and murine (P. c. chabaudi) models of malaria 33, 34. Bestatin is an effective inhibitor of PfA‐M1 and derivatives have been developed as chemical probes to investigate the biological role and substrate specificity of the aminopeptidase, although it should be noted that many of these inhibitors are not only selective for PfA‐M1 but also act on a second, unrelated essential zinc‐dependent aminopeptidase, PfA‐M17 (clan MF, family M17) 28, 30. Organophosphorous inhibitors, such as hPheP[CH2]Phe, have also been developed as PfA‐M1 inhibitors and characterized as potent antimalarials both in vitro and in vivo 27, 33, 35, 36. More recent studies have strategically developed dual inhibitors to target both PfA‐M1 and PfA‐M17 in an approach designed to reduce the risk of the rapid development of drug resistance. The most effective of these inhibitors combines a hydroxamic acid zinc‐binding group linked to fluoro‐substituted bi‐aryl system (10o, Fig. 2B), which occupies the S1 subsite, and short aliphatic moieties, to probe the S1′ subsite (Fig. 3) 29, 32. These inhibitors have shown promise in in vitro parasite cultures, but are yet to be tested in animal models. Despite this, PfA‐M1 is to our knowledge, the only validated M1 aminopeptidase drug target identified in pathogenic organisms.

Figure 3.

PfA‐M1 in complex with potent inhibitor. The designed inhibitor 10o (purple stick representation), coordinates the catalytic zinc ion (gray sphere) through a hydroxamic acid, and occupies both the S1 and S1′ subsites 32. Key PfA‐M1 active site residues lining the subsites are shown as gray sticks, with those of the zinc‐binding motif colored wheat.

Vaccine development

Vaccines are considered the ultimate goal for the control of infectious diseases. Immunogenic pathogen‐encoded M1 aminopeptidases have been identified in the eubacterial and protista kingdoms, and therefore represent exciting possibilities for the development of novel vaccine candidates. Although this therapeutic potential is not directly related to their enzyme activity, it relies on the importance of the M1 aminopeptidases to the target organism. Brucella spp., the causative agents of brucellosis in humans, possess an M1 aminopeptidase, PepN, which is recognized by sera from human patients with acute and chronic brucellosis 37, 38. In parasites, Cryptosporidium parvum 39 and T. gondii 24 produce at least one M1 aminopeptidase that is immunogenic. While promising, the potential to raise vaccines against these enzymes for therapeutic use against pathogen infection requires further investigation.

As a novel approach to develop a malaria vaccine, the Anopheles mosquito aminopeptidase N (AnAPN1) has been targeted to prevent transmission of the parasite from human to mosquito. The ultimate aim of such a transmission‐blocking vaccine is to limit the number of infectious mosquito vectors and introduce local herd immunity 40. In Anopheles gambiae, AnAPN is present on the apical surface of the midgut of the mosquito as a membrane bound dimer and is required for parasite infection 41. Therefore, should a mosquito feed on a vaccinated human, antibodies specific for AnAPN1 would block infection of the mosquito. AnAPN1 is an immunogenic antigen that induces potent, long‐lasting, strain‐ and species‐transcending, transmission‐blocking antibodies that function independently of aminopeptidase activity 42. Interestingly, when the epitopes of transmission‐blocking monoclonal antibodies are mapped onto the structure of AnAPN1, they are localized to the surface of domain I on the inner wall of the proposed dimer 43. This region of the protein is in close proximity to the membrane surface, which raises questions as to the molecular mechanism of antibody recognition and binding to AnAPN1 in vivo.

Human aminopeptidase N (APN) acts as a cell entry receptor for a number of enveloped, plus‐RNA coronaviruses (CoV), which are responsible for a range of enteric and respiratory diseases (reviewed in 44). Binding between a CoV glycoprotein spike on the envelope of the virus and the helical C‐terminal domain(s) IV of the APN dimer initiates membrane fusion and viral entry 44, 45. This interaction, crucial to viral infection, is therefore an exciting target for vaccine development. Current studies have already validated the approach, with antibodies targeted against the surface glycoprotein spike of CoV demonstrated to prevent the interaction with APN and neutralize the virus 45. This action occurs independently of APN aminopeptidase activity, which in itself is a validated therapeutic target, and discussed later in this review.

Chronic diseases of humans

Treatment of a pathogenic organism is, in theory, a simple case of inhibition of an essential process within an invading organism. In contrast, treatment of chronic diseases of humans often requires modulating the activity of key regulators of disease‐relevant pathways. The identification of a single therapeutic target through which to modulate this pathway is incredibly complex. In cases wherein aberrant expression or activity of a protein results in disease, then it is a relatively simple process of inhibiting that proteins’ activity, however, these cases are rare. More commonly, it is an abnormal function of a protein that contributes to disease, or a complex network of factors that are often not well understood. In these cases, target identification involves the dissection of the roles of individual proteins within the complex regulatory pathway(s). This is further complicated when targeting human M1 aminopeptidases. There are nine characterized M1 aminopeptidases in humans, which are closely related, and possess overlapping reaction specificities. The selective targeting of a single family member is therefore difficult. Six of the human M1 aminopeptidases have been implicated in the pathology of disease states, which has served to illuminate the function of the enzymes and identify possibly therapeutic uses for inhibitors. The remaining three (Thyrotropin‐releasing, hormone‐degrading ectoenzyme, NPEPPS, and Aminopeptidase B), to our knowledge, have no identified role in the pathogenesis or treatment of disease, and will not be discussed further.

Hypertension

The brain renin–angiotensin system is an important regulator of blood pressure. The pathway involves a cascade of proteolytic steps to process peptidic hormones, each of which possess unique functions. Two M1 aminopeptidases are involved in this pathway; aminopeptidase A (APA) catalyses the conversion of angiotensin II to angiotensin III, which is then processed to angiotensin IV by APN 46. Angiotensin III has been identified as exerting the greatest effect on central blood pressure in animal models 46. Therefore, while both enzymes have been implicated in the central regulation of blood pressure, only the inhibition of APA has been validated as a strategy to treat hypertension. Prior to the availability of a crystal structure, a homology model of APA was designed and used to dock inhibitors into the active site 47. When the crystal structure was subsequently determined, it showed good agreement with the model 9. APA activity requires a Ca+2 at the base of the S1 subsite in addition to the conserved Zn+2 characteristic of this enzyme class. Lead compound EC33 (Fig. 2C, K i for APA = 0.29 μm) engaged both metal ions, was selective for APA over APN, and inhibited brain APA in a dose‐dependent manner 48, 49. Further, the orally active prodrug form of EC33, RB150, reduced blood pressure in hypertensive rats models, and did not affect blood pressure in normotensive animals 50, 51. EC33 is small, and contains a thiol predicted to interact with the catalytic Zn+2 (Fig. 2C). While selectivity over APN has been determined, to our knowledge, no studies assessing its binding to other human zinc‐dependent proteases have been conducted. Given EC33 is a relatively weak APA inhibitor, the presence of additional physiological effectors cannot be ruled out. Promisingly, a single dose of RB150 is well tolerated in humans, and has progressed through Phase Ib clinical trials, and is therefore suitable for further longer term studies in hypertensive patients 51, 52.

If a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of human disease includes strategic targeting of a pathway with an important physiological role, side effects are a major concern. The central renin–angiotensin system has been implicated in neurovascular unit disorders (see review 53). Evidence for this role includes studies in experimental models that show angiotensin II is deleterious to stroke recovery and the pathogenesis of retinopathy (see review 53). If APA inhibitors, which inhibit the conversion of angiotensin II to angiotensin III, lead to a buildup in angiotensin II, then long‐term treatment could have serious adverse effects.

Inflammatory disease

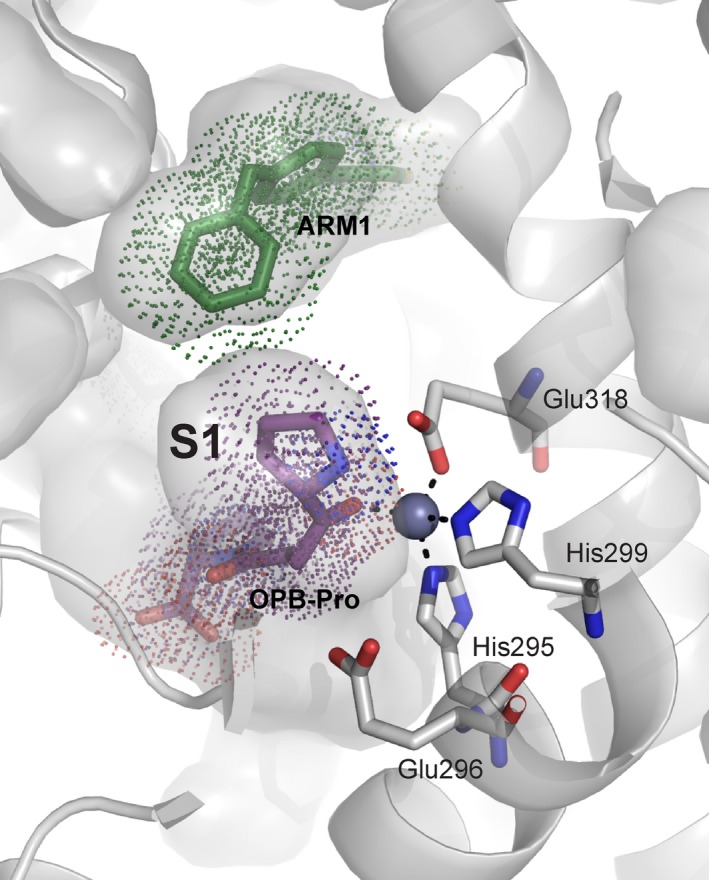

The structure of the human LTA4H was the first determined structure of a eukaryotic M1 aminopeptidase 6. It was the subject of such early scrutiny due to its unique characterization as a bifunctional enzyme with two distinct catalytic functions: epoxide hydrolase activity to convert LTA4 into leukotriene B4 (LTB4) 54 and aminopeptidase activity to degrade and inactivate the tripeptide Pro‐Gly‐Pro (PGP) 55. Perhaps even more curious, is that these two catalytic functions operate on opposing sides of the inflammatory response. LTB4 and PGP both attract neutrophils and promote inflammation, therefore while the epoxide hydrolase activity of LTA4H has a proinflammatory effect, the aminopeptidase activity of LTA4H has an anti‐inflammatory effect 56, and only inhibition of the hydrolase activity would be desired for an anti‐inflammatory therapeutic. Prior to identification of PGP as a physiological substrate, LTA4H was targeted for the treatment of inflammatory diseases such as acute lung injury, cardiovascular disease, and stroke. The identification of PGP as the physiological substrate for LTA4H has since precipitated the structural characterization of the two distinct catalytic roles. Despite the necessity of the catalytic zinc ion for both catalytic mechanisms, the two sites are distinct (Fig. 4), and the inhibitor ARM1 (Fig. 2D) is capable of selective inhibition of the epoxide hydrolase activity 56. This study provides the first convincing evidence that LTA4H could be a useful therapeutic target.

Figure 4.

The two distinct catalytic sites of LTA4H. The cocrystal structure of LTA4H in complex with substrate analog OPB‐Pro (purple) and ARM1 (green), a selective inhibitor of the epoxide hydrolase activity 56. Ligands are shown as colored sticks, with dots indicating atomic radii. LTA4H is shown in gray with catalytic zinc (sphere), residues of the zinc‐binding motif (sticks), and solvent‐exposed area (surface representation) indicated.

These recent advances in our understanding of LTA4H have emphasized the remaining gaps in our knowledge. Early structure‐based substrate profiling studies demonstrated LTA4H shows a preference for tripeptides with a P1 arginine that binds within a distinct specificity pocket 57. The identification of PGP as the physiological substrate is therefore surprising and suggests there are important physiological substrates for the LTA4H aminopeptidase activity that we do not yet understand. As we continue to uncover these unknown functions, we are likely to further illuminate other phenomena not previously understood. For example, a 2016 study recently implicated LTA4H as the potential target of a topical anti‐inflammatory agent, Bufexamac (Fig. 2E), which was previously attributed to targeting cyclooxygenase, although with limited direct evidence 58. Xiao et al. characterized the inhibition of the LTA4H epoxide hydrolase activity by bufexamac, and determined the cocrystal structure. This structure showed bufexamac bound in the PGP site by coordination of the catalytic Zn+2. Therefore, we can infer that bufexamac inhibits both the aminopeptidase and hydrolase activity of LTA4H. Interestingly, side effects of Bufexamac include allergic contact dermatitis 59, which could be explained by the inhibition of PGP breakdown. This has led to recommendations in Europe to remove it from the market. Despite this, Xiao et al. went on to show that bufexamac inhibits LTB4 biosynthsis in neutrophils, thus inhibiting chemotaxis, and alleviated lipopolysaccharide‐induced acute lung injury, a neutrophilic inflammation‐associated disease, in mouse models 58. While this is promising, the potential side effects caused by interfering with PGP breakdown need to be given serious consideration in future LTA4H inhibition studies.

Cancer

Aminopeptidase N (APN) has been described as a ‘moonlighting’ enzyme because it is involved in a vast range of biological processes including processing of neuropeptides and chemokines, cell adhesion, endocytosis, and as a receptor for coronavirus (reviewed in 3). APN is most commonly observed as a membrane‐anchored dimer 3, 7, although a monomeric form in serum has also been described 60. Overexpression of APN has been observed on leukemic blasts in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) 61, and compelling studies have implicated APN protease activity in tumor‐associated processes, particularly angiogenesis and metastasis 62, 63. The aminopeptidase activity of APN has therefore been intensively studied as a target for AML and a wide range of tumor types 64, 65, 66, 67, 68. The most widely studied competitive APN inhibitors, Ubenimex (Bestatin) and Tosedostat (formerly CHR‐2797), have been clinically investigated for their anticancer effects: Ubenimex is approved for treatment of lung cancer, AML, and nasopharyngeal cancer, and Tosedostat showed significant antileukemic activity in Phase I/II clinical trials 65. Currently Phase I/II studies of Tosedostat in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents for AML and metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma are ongoing. Furthermore, Su et al. 69, showed that increasing a compounds APN inhibitory activity improved the antimetastasis and antiangiogenesis effects in vivo, thereby providing evidence that their anticancer effect is a direct result of inhibition of APN peptidase activity.

Bestatin also inhibits other human M1 aminopeptidases including aminopeptidase B, aminopeptidase A, LTA4H, and the M17 leucyl aminopeptidase 1, 2. Therefore, selectivity is a particular concern for its use as a therapeutic. The recent determination of the X‐ray crystal structure of bestatin in complex with APN showed that bestatin binds with a noncanonical pose, coordinating the zinc with its terminal carboxylic acid (Fig. 5) 7. This is curious, given that all other bestatin‐bound aminopeptidase structures, including the closely related porcine APN (80% sequence identity), show a binding mode wherein the backbone hydroxy ketone of bestatin coordinates the active site zinc ion (Fig. 5). Irrespective of whether this unusual binding pose is observed in solution, it shows that human APN has the capacity to bind ligands differently to other M1 aminopeptidases, and suggests that careful structure‐guided drug discovery methods could exploit the differences in M1 aminopeptidase active sites to design selective APN inhibitors. A second potential solution to the selectivity issues of bestatin is presented by in vitro studies conducted by Saiki et al., who demonstrated that an APN‐specific monoclonal antibody WM15 inhibits invasion of highly metastatic cancer cells into recombinant basement membrane in a dose‐dependent manner 63. Subsequent studies showed that WM15 inhibits tumor‐derived APN activity and degradation of type‐IV collagen, suggesting that APN may also be involved in extracellular matrix degradation 63.

Figure 5.

Bestatin binds APN in a noncanonical pose (orange) 7, rather than the conserved canonical pose for other M1 aminopeptidases (blue, APA in complex with bestatin used as representative 9). APN solvent accessible surface area shown in gray and residues of the zinc‐binding motif as gray sticks. Catalytic zinc ions shown as spheres for APN (orange) and APA (blue).

A second human M1 aminopeptidase, endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 (ERAP1), has also been targeted for the development of small‐molecule inhibitors as anticancer therapeutics 70. This strategy, however, does not directly target cancer cells, but modulates immune function to elicit a cytotoxic T‐cell response. Therefore, we will discuss inhibitors that target human M1 aminopeptidases to modulate immune responses separately.

Immune‐mediated disease

Perhaps the most complex target of human M1 aminopeptidase inhibitors is the cellular adaptive immune response via the action of thee highly homologous enzymes: endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidases 1 and 2 (ERAP1 and ERAP2), and insulin‐regulated aminopeptidase (IRAP). Broadly, their role is to process antigens for loading onto the major histocompatibility complex and subsequent recognition by the appropriate T‐cell. Much of our understanding of the role of these enzymes is derived from comparative genome studies showing polymorphisms in the three enzymes are associated with immune‐mediated diseases, as well as mouse models and in vitro knockdown (see reviews 71, 72). Polymorphisms of ERAP1/ERAP2/IRAP undoubtedly result in disease; however, proposed therapeutic uses of inhibitors are not targeted to these loss‐of‐function phenotypes, but rather toward autoimmune diseases and manipulation of the body's own immune response to combat disease (for a review of the proposed uses of ERAP1/ERAP2/IRAP as therapeutic targets see 72). Compounds that coordinate the catalytic zinc ion of ERAP1/ERAP2/IRAP with a phosphinic acid and occupy the substrate pockets via peptide‐like moieties (e.g., DG013A, Fig. 2F) potently inhibit all three enzymes, and alter antigen processing and presentation to enhance the cytotoxic response in murine cancer cell lines 70. While promising, complete inhibition of all three enzymes can be expected to result in side effects analogous to loss‐of‐function phenotypes. The strategy to target one or more of ERAP1/ERAP2/IRAP therefore requires careful validation, and a greater understanding of the specific physiological roles of each of the enzymes. Examination of their function and assessment of their potential as therapeutic targets is greatly complicated by the current choices of animal models; while mouse models have often been used, there are major differences in the antigen‐processing pathway between mice and humans, including a complete lack of ERAP2 in mice (discussed by Ref. 73).

If we are to comprehensively characterize the function of each of ERAP1, ERAP2, and IRAP, and properly judge whether they are valid therapeutic targets, inhibitors that are both potent and selective for each of the three enzymes are required for use as chemical probes. High‐resolution crystal structures of all three enzymes are available 74, 75, 76, which opens the door to the use of structure‐based drug design to develop such inhibitors. Research led by Stratikos recognizes this, and is spearheading the design of selective inhibitors for all three enzymes guided by a combination of crystallography and docking studies 77, 78. Although they have successfully developed submicromolar inhibitors, the use of IC50 values rather than inhibition constants (K i) to measure compound inhibitory activity means that it is difficult to determine whether true selectivity has been achieved. Most recently, Weglarz‐Tomczak et al. have used a collection of previously designed, generic M1 aminopeptidase inhibitors to generate selective, submicromolar inhibitors of ERAP2 79. However, ERAP1 could not be selectively inhibited over ERAP2, and the compounds have not been tested for IRAP inhibition.

While there is temptation to promote ERAP1, ERAP2, and/or IRAP inhibitors as therapeutic agents to regulate immune function, the strategy remains speculative. Inhibitors have been developed, and unarguably show disease‐relevant changes in the host response. But, whether these will be effective in treating specific disease states has not been established. There are complex and multiple roles attributed to ERAP1, ERAP2, and IRAP, which we do not fully understand. Therefore, any pharmaceutical modification of their activity must proceed with extreme caution. For example, IRAP clearly has other roles outside of immune regulation including memory and cognition 80, 81 and regulating spine density 82. While these studies present further tantalizing ideas for the use of inhibitors specific for ERAP1, ERAP2, or IRAP as therapeutics, their role in such a range of essential physiological processes should also serve as a warning.

Conclusions

M1 aminopeptidases play multiple, important roles in a wide range of physiological processes and organisms. The importance of these functions, in combination with a defined active site readily amenable to inhibitor design, has led many research groups to target their protease activity with the intention of developing novel human therapeutics. This has been supported by a vast repertoire of structural information available to guide and accelerate inhibitor development. However, as tempting as these attributes may be, the combination of disease‐relevant physiological functions with druggable active sites does not alone rationalize them as valid drug targets.

If a pathogenic organism possesses a single, essential M1 aminopeptidase, as we observe in P. falciparum, subsequent design of a potent inhibitor with therapeutic activity is, in theory, straightforward. However, our review of the literature shows that the first vital step, the demonstration that the M1 aminopeptidase activity is absolutely required for pathogen survival, has often been neglected. This oversight has resulted in unsubstantiated claims of compounds possessing antimicrobial activity. Once validated, the major challenge for targeting an M1 aminopeptidase is likely to be acquiring specificity over the highly conserved human homologs. However, it could be argued that manageable side effects that result from inhibition of a human M1 aminopeptidase may be acceptable for the short span of treatment required to clear a pathogen from the body.

Humans possess nine M1 aminopeptidases, the precise physiological roles of which are not fully understood. Those that have been implicated in a disease state have been studied in greater detail, which has illustrated the complexity of the physiological networks and roles for a single human M1 aminopeptidase. Despite this, inhibitors of both APA and APN have already shown promise in the clinic for treatment of hypertension and cancer‐type diseases, respectively. In the remaining cases, particularly LTA4H, ERAP1, ERAP2, and IRAP, carefully designed chemical probes need to be used as tools to further investigate the precise physiological roles for the enzymes in vivo before a single enzyme can be validated as a therapeutic target. During this validation process, close attention needs to be paid to ensure that the inhibitors are specific for the targeted enzyme over the other M1 aminopeptidases, and that suitable animal models are chosen. Many of the developed inhibitors have been based on substrate analogs or small zinc‐binding compounds. This design strategy raises substantial concerns regarding selectivity, as the M1 aminopeptidases all possess conserved active site zinc‐binding and catalytic exopeptidase motifs, and are therefore likely to be inhibited by similar molecules. As a result, much of the available information describing the role of an M1 aminopeptidase and its potential as a therapeutic target is derived from nonspecific inhibitors. Inhibitor specificity remains a problem even for those M1 aminopeptidases that have been validated as drug targets. Off‐target side effects caused by lack of selectivity for a specific enzyme may not be identified until long‐term treatment during clinical trials. However, they could potentially be avoided during the development stage by utilizing the detailed structural information on enzyme homologs to guide inhibitor development as well as comprehensive testing of the inhibitory capacity of lead compounds against the full panel of human M1 aminopeptidases.

Overall, while our analysis of recent literature has identified some attractive therapeutic uses for M1 aminopeptidase inhibitors, it has also highlighted a need for early validation of M1 aminopeptidases via appropriate in vivo studies using knockdown/knockout models and carefully designed chemical probes. Therefore, while M1 aminopeptidase inhibitors hold promise for the treatment of a range of conditions including malaria, hypertension, and cancer, inhibitor design must be approached with great caution, and conducted with full respect for the vast range of physiological processes with which related M1 aminopeptidases are involved. Finally, recent research highlighting the potential for vaccines targeted against M1 aminopeptidases independent of protease function may further broaden the range of treatment options for M1 aminopeptidase‐targeted therapeutics.

Author contributions

ND and SM defined the concept of the review, checked the literature, and wrote the manuscript; JL, WY, and TM checked literature and assisted in writing the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (Project grant 1063786 to SM). JL, TM, and WY are supported by postgraduate scholarships from Monash University as well as a Sir James McNeil Foundation Postgraduate Scholarship to JL.

Note

We apologize in advance if during our efforts to condense an enormous field down to a short opinion piece, we have not done justice to your research or cited your research directly.

References

- 1. Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ & Bateman A (2012) MEROPS: the database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res 40, D343–D350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rawlings ND, Tolle DP & Barrett AJ (2004) Evolutionary families of peptidase inhibitors. Biochem J 378, 705–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mina‐Osorio P (2008) The moonlighting enzyme CD13: old and new functions to target. Trends Mol Med 14, 361–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peer WA (2010) The role of multifunctional M1 metallopeptidases in cell cycle progression. Ann Bot 107, 1171–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen L, Lin YL, Peng G & Li F (2012) Structural basis for multifunctional roles of mammalian aminopeptidase N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 17966–17971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thunnissen M, Nordlund P & Haeggstrom JZ (2001) Crystal structure of human leukotriene A(4) hydrolase, a bifunctional enzyme in inflammation. Nature Struct Biol 8, 131–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wong AHM, Zhou D & Rini JM (2012) The X‐ray crystal structure of human aminopeptidase N reveals a novel dimer and the basis for peptide processing. J Biol Chem 287, 36804–36813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hermans SJ, Ascher DB, Hancock NC, Holien JK, Michell BJ, Chai SY, Morton CJ & Parker MW (2015) Crystal structure of human insulin‐regulated aminopeptidase with specificity for cyclic peptides. Protein Sci 24, 190–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang Y, Liu C, Lin YL & Li F (2013) Structural insights into central hypertension regulation by human aminopeptidase A. J Biol Chem 288, 25638–25645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Umezawa H, Aoyagi T, Suda H, Hamada M & Takeuchi T (1976) Bestatin, an inhibitor of aminopeptidase B, produced by actinomycetes. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 29, 97–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chandu D & Nandi D (2003) PepN is the major aminopeptidase in Escherichia coli: insights on substrate specificity and role during sodium‐salicylate‐induced stress. Microbiology 149, 3437–3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Supuran CT & Mastrolorenzo A (2011) Bacterial zinc proteases and their inhibition. Curr Enzym Inhib 7, 2–23. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grenier D & Michaud J (1994) Selective growth inhibition of Porphyromonas gingivalis by bestatin. FEMS Microbiol Lett 123, 193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Modak JK, Rut W, Wijeyewickrema LC, Pike RN, Drag M & Roujeinikova A (2016) Structural basis for substrate specificity of Helicobacter pylori M17 aminopeptidase. Biochimie 121, 60–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Singh AK, Singh R, Tomar D, Pandya CD & Singh R (2012) The leucine aminopeptidase of Staphylococcus aureus is secreted and contributes to biofilm formation. Int J Infect Dis 16, e375–e381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yen C, Green L & Miller CG (1980) Peptide accumulation during growth of peptidase deficient mutants. J Mol Biol 143, 35–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nocek B, Mulligan R, Bargassa M, Collart F & Joachimiak A (2007) Crystal structure of aminopeptidase N from human pathogen Neisseria meningitidis . Proteins 273, 273–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weglarz‐Tomczak E, Poreba M, Byzia A, Berlicki L, Nocek B, Mulligan R, Joachimiak A, Drag M & Mucha A (2013) An integrated approach to the ligand binding specificity of Neisseria meningitidis M1 alanine aminopeptidase by fluorogenic substrate profiling, inhibitory studies and molecular modeling. Biochimie 95, 419–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weglarz‐Tomczak E, Berlicki L, Pawelczak M, Nocek B, Joachimiak A & Mucha A (2016) A structural insight into the P1S1 binding mode of diaminoethylphosphonic and phosphinic acids, selective inhibitors of alanine aminopeptidases. Eur J Med Chem 117, 187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rascon AA Jr & McKerrow JH (2013) Synthetic and natural protease inhibitors provide insights into parasite development, virulence and pathogenesis. Curr Med Chem 20, 3078–3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maggioli G, Acosta D, Silveira F, Rossi S, Giacaman S, Basika T, Gayo V, Rosadilla D, Roche L, Tort J et al (2011) The recombinant gut‐associated M17 leucine aminopeptidase in combination with different adjuvants confers a high level of protection against Fasciola hepatica infection in sheep. Vaccine 29, 9057–9063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gupta R, Kushawaha PK, Tripathi CD, Sundar S & Dube A (2012) A novel recombinant Leishmania donovani p45, a partial coding region of methionine aminopeptidase, generates protective immunity by inducing a Th1 stimulatory response against experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Int J Parasitol 42, 429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cadavid‐Restrepo G, Gastardelo TS, Faudry E, de Almeida H, Bastos IM, Negreiros RS, Lima MM, Assumpcao TC, Almeida KC, Ragno M et al (2011) The major leucyl aminopeptidase of Trypanosoma cruzi (LAPTc) assembles into a homohexamer and belongs to the M17 family of metallopeptidases. BMC Biochem 12, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berthonneau J, Rodier MH, El Moudni B & Jacquemin JL (2000) Toxoplasma gondii: purification and characterization of an immunogenic metallopeptidase. Exp Parasitol 95, 158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pillay D, Boulange AF, Coustou V, Baltz T & Coetzer TH (2013) Recombinant expression and biochemical characterisation of two alanyl aminopeptidases of Trypanosoma congolense . Exp Parasitol 135, 675–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dalal S & Klemba M (2007) Roles for two aminopeptidases in vacuolar hemoglobin catabolism in Plasmodium falciparum . J Biol Chem 282, 35978–35987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McGowan S, Porter CJ, Lowther J, Stack CM, Golding SJ, Skinner‐Adams TS, Trenholme KR, Teuscher F, Donnelly SM, Grembecka J et al (2009) Structural basis for the inhibition of the essential Plasmodium falciparum M1 neutral aminopeptidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 2537–2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harbut MB, Velmourougane G, Dalal S, Reiss G, Whisstock JC, Onder O, Brisson D, McGowan S, Klemba M & Greenbaum DC (2011) Bestatin‐based chemical biology strategy reveals distinct roles for malaria M1‐ and M17‐family aminopeptidases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, E526–E534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mistry SN, Drinkwater N, Ruggeri C, Sivaraman KK, Loganathan S, Fletcher S, Drag M, Paiardini A, Avery VM, Scammells PJ et al (2014) Two‐pronged attack: dual inhibition of Plasmodium falciparum M1 and M17 metalloaminopeptidases by a novel series of hydroxamic acid‐based inhibitors. J Med Chem 57, 9168–9183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Velmourougane G, Harbut MB, Dalal S, McGowan S, Oellig CA, Meinhardt N, Whisstock JC, Klemba M & Greenbaum DC (2011) Synthesis of new (‐)‐bestatin‐based inhibitor libraries reveals a novel binding mode in the S1 pocket of the essential malaria M1 metalloaminopeptidase. J Med Chem 54, 1655–1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Deprez‐Poulain R, Flipo M, Piveteau C, Leroux F, Dassonneville S, Florent I, Maes L, Cos P & Deprez B (2012) Structure‐activity relationships and blood distribution of antiplasmodial aminopeptidase‐1 inhibitors. J Med Chem 55, 10909–10917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Drinkwater N, Vinh NB, Mistry SN, Bamert RS, Ruggeri C, Holleran JP, Loganathan S, Paiardini A, Charman SA, Powell AK et al (2016) Potent dual inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum M1 and M17 aminopeptidases through optimization of S1 pocket interactions. Eur J Med Chem 110, 43–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Skinner‐Adams TS, Lowther J, Teuscher F, Stack CM, Grembecka J, Mucha A, Kafarski P, Trenholme KR, Dalton JP & Gardiner DL (2007) Identification of phosphinate dipeptide analog inhibitors directed against the Plasmodium falciparum M17 leucine aminopeptidase as lead antimalarial compounds. J Med Chem 50, 6024–6031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Skinner‐Adams TS, Peatey CL, Anderson K, Trenholme KR, Krige D, Brown CL, Stack C, Nsangou DM, Mathews RT, Thivierge K et al (2012) The aminopeptidase inhibitor CHR‐2863 is an orally bioavailable inhibitor of murine malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56, 3244–3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kannan Sivaraman K, Paiardini A, Sienczyk M, Ruggeri C, Oellig CA, Dalton JP, Scammells PJ, Drag M & McGowan S (2013) Synthesis and structure‐activity relationships of phosphonic arginine mimetics as inhibitors of the M1 and M17 aminopeptidases from Plasmodium falciparum . J Med Chem 56, 5213–5217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grembecka J, Mucha A, Cierpicki T & Kafarski P (2003) The most potent organophosphorus inhibitors of leucine aminopeptidase. Structure‐based design, chemistry, and activity. J Med Chem 46, 2641–2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Contreras‐Rodriguez A, Ramirez‐Zavala B, Contreras A, Schurig GG, Sriranganathan N & Lopez‐Merino A (2003) Purification and characterization of an immunogenic aminopeptidase of Brucella melitensis . Infect Immun 71, 5238–5244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Contreras‐Rodriguez A, Seleem MN, Schurig GG, Sriranganathan N, Boyle SM & Lopez‐Merino A (2006) Cloning, expression and characterization of immunogenic aminopeptidase N from Brucella melitensis . FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 48, 252–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Padda RS, Tsai A, Chappell CL & Okhuysen PC (2002) Molecular cloning and analysis of the Cryptosporidium parvum aminopeptidase N gene. Int J Parasitol 32, 187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dinglasan RR & Jacobs‐Lorena M (2008) Flipping the paradigm on malaria transmission‐blocking vaccines. Trends Parasitol 24, 364–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dinglasan RR, Kalume DE, Kanzok SM, Ghosh AK, Muratova O, Pandey A & Jacobs‐Lorena M (2007) Disruption of Plasmodium falciparum development by antibodies against a conserved mosquito midgut antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 13461–13466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Armistead JS, Morlais I, Mathias DK, Jardim JG, Joy J, Fridman A, Finnefrock AC, Bagchi A, Plebanski M, Scorpio DG et al (2014) Antibodies to a single, conserved epitope in Anopheles APN1 inhibit universal transmission of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax malaria. Infect Immun 82, 818–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Atkinson SC, Armistead JS, Mathias DK, Sandeu MM, Tao D, Borhani‐Dizaji N, Tarimo BB, Morlais I, Dinglasan RR & Borg NA (2015) The Anopheles‐midgut APN1 structure reveals a new malaria transmission‐blocking vaccine epitope. Nat Struct Mol Biol 22, 532–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bosch BJ, Smits SL & Haagmans BL (2014) Membrane ectopeptidases targeted by human coronaviruses. Curr Opin Virol 6, 55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Reguera J, Santiago C, Mudgal G, Ordono D, Enjuanes L & Casasnovas JM (2012) Structural bases of coronavirus attachment to host aminopeptidase N and its inhibition by neutralizing antibodies. PLoS Pathog 8, e1002859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zini S, FournieZaluski MC, Chauvel E, Roques BP, Corvol P & LlorensCortes C (1996) Identification of metabolic pathways of brain angiotensin II and III using specific aminopeptidase inhibitors: predominant role of angiotensin III in the control of vasopressin release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93, 11968–11973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rozenfeld R, Iturrioz X, Maigret B & Llorens‐Cortes C (2002) Contribution of molecular modeling and site‐directed mutagenesis to the identification of two structural residues, Arg‐220 and Asp‐227, in aminopeptidase A. J Biol Chem 277, 29242–29252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chauvel EN, Llorens‐Cortes C, Coric P, Wilk S, Roques BP & Fournie‐Zaluski MC (1994) Differential inhibition of aminopeptidase A and aminopeptidase N by new beta‐amino thiols. J Med Chem 37, 2950–2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fournie‐Zaluski MC, Fassot C, Valentin B, Djordjijevic D, Reaux‐Le Goazigo A, Corvol P, Roques BP & Llorens‐Cortes C (2004) Brain renin‐angiotensin system blockade by systemically active aminopeptidase A inhibitors: a potential treatment of salt‐dependent hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101, 7775–7780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Marc Y, Gao J, Balavoine F, Michaud A, Roques BP & Llorens‐Cortes C (2012) Central antihypertensive effects of orally active aminopeptidase A inhibitors in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 60, 411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bodineau L, Frugiere A, Marc Y, Inguimbert N, Fassot C, Balavoine F, Roques B & Llorens‐Cortes C (2008) Orally active aminopeptidase A inhibitors reduce blood pressure – a new strategy for treating hypertension. Hypertension 51, 1318–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gao J, Marc Y, Iturrioz X, Leroux V, Balavoine F & Llorens‐Cortes C (2014) A new strategy for treating hypertension by blocking the activity of the brain renin‐angiotensin system with aminopeptidase A inhibitors. Clin Sci (Lond) 127, 135–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fouda AY, Artham S, El‐Remessy AB & Fagan SC (2016) Renin‐angiotensin system as a potential therapeutic target in stroke and retinopathy: experimental and clinical evidence. Clin Sci (Lond) 130, 221–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Haeggstrom JZ (2004) Leukotriene A4 hydrolase/aminopeptidase, the gatekeeper of chemotactic leukotriene B4 biosynthesis. J Biol Chem 279, 50639–50642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Snelgrove RJ, Jackson PL, Hardison MT, Noerager BD, Kinloch A, Gaggar A, Shastry S, Rowe SM, Shim YM, Hussell T et al (2010) A critical role for LTA4H in limiting chronic pulmonary neutrophilic inflammation. Science 330, 90–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Stsiapanava A, Olsson U, Wan M, Kleinschmidt T, Rutishauser D, Zubarev RA, Samuelsson B, Rinaldo‐Matthis A & Haeggstrom JZ (2014) Binding of Pro‐Gly‐Pro at the active site of leukotriene A4 hydrolase/aminopeptidase and development of an epoxide hydrolase selective inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 4227–4232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tholander F, Muroya A, Roques BP, Fournie‐Zaluski MC, Thunnissen MM & Haeggstrom JZ (2008) Structure‐based dissection of the active site chemistry of leukotriene A4 hydrolase: implications for M1 aminopeptidases and inhibitor design. Chem Biol 15, 920–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Xiao Q, Dong N, Yao X, Wu D, Lu Y, Mao F, Zhu J, Li J, Huang J, Chen A et al (2016) Bufexamac ameliorates LPS‐induced acute lung injury in mice by targeting LTA4H. Sci Rep 6, 25298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Uter W & Schnuch A (2011) EMA revokes marketing authorization for bufexamac. Contact Dermatitis 64, 235–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Watanabe Y, Ito K, Iwaki‐Egawa S, Yamaguchi R & Fujimoto Y (1998) Aminopeptidase N in sera of healthy subjects is a different N‐terminal processed derivative from the one obtained from maternal serum. Mol Genet Metab 63, 289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Taussig DC, Pearce DJ, Simpson C, Rohatiner AZ, Lister TA, Kelly G, Luongo JL, Danet‐Desnoyers GA & Bonnet D (2005) Hematopoietic stem cells express multiple myeloid markers: implications for the origin and targeted therapy of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 106, 4086–4092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lu P, Weaver VM & Werb Z (2012) The extracellular matrix: a dynamic niche in cancer progression. J Cell Biol 196, 395–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Saiki I, Fujii H, Yoneda J, Abe F, Nakajima M, Tsuruo T & Azuma I (1993) Role of aminopeptidase N (CD13) in tumor‐cell invasion and extracellular matrix degradation. Int J Cancer 54, 137–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bauvois B & Dauzonne D (2006) Aminopeptidase‐N/CD13 (EC 3.4.11.2) inhibitors: chemistry, biological evaluations, and therapeutic prospects. Med Res Rev 26, 88–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lowenberg B, Morgan G, Ossenkoppele GJ, Burnett AK, Zachee P, Duhrsen U, Dierickx D, Muller‐Tidow C, Sonneveld P, Krug U et al (2010) Phase I/II clinical study of Tosedostat, an inhibitor of aminopeptidases, in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplasia. J Clin Oncol 28, 4333–4338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mucha A, Drag M, Dalton JP & Kafarski P (2010) Metallo‐aminopeptidase inhibitors. Biochimie 92, 1509–1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Piedfer M, Dauzonne D, Tang R, N'Guyen J, Billard C & Bauvois B (2011) Aminopeptidase‐N/CD13 is a potential proapoptotic target in human myeloid tumor cells. FASEB J 25, 2831–2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wickstrom M, Larsson R, Nygren P & Gullbo J (2011) Aminopeptidase N (CD13) as a target for cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Sci 102, 501–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Su L, Jia Y, Zhang L, Xu Y, Fang H & Xu W (2012) Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel amino acid ureido derivatives as aminopeptidase N/CD13 inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem 20, 3807–3815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zervoudi E, Saridakis E, Birtley JR, Seregin SS, Reeves E, Kokkala P, Aldhamen YA, Amalfitano A, Mavridis IM, James E et al (2013) Rationally designed inhibitor targeting antigen‐trimming aminopeptidases enhances antigen presentation and cytotoxic T‐cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, 19890–19895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Agrawal N & Brown MA (2014) Genetic associations and functional characterization of M1 aminopeptidases and immune‐mediated diseases. Genes Immun 15, 521–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Stratikos E (2014) Regulating adaptive immune responses using small molecule modulators of aminopeptidases that process antigenic peptides. Curr Opin Chem Biol 23, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Robinson PC & Brown MA (2014) ERAP1 biology and assessment in Ankylosing Spondylitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, E1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Birtley JR, Saridakis E, Stratikos E & Mavridis IM (2012) The crystal structure of human endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 2 reveals the atomic basis for distinct roles in antigen processing. Biochemistry 51, 286–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kochan G, Krojer T, Harvey D, Fischer R, Chen L, Vollmar M, von Delft F, Kavanagh KL, Brown MA, Bowness P et al (2011) Crystal structures of the endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase‐1 (ERAP1) reveal the molecular basis for N‐terminal peptide trimming. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 7745–7750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Mpakali A, Saridakis E, Harlos K, Zhao YG, Papakyriakou A, Kokkala P, Georgiadis D & Stratikos E (2015) Crystal structure of insulin‐regulated aminopeptidase with bound substrate analogue provides insight on antigenic epitope precursor recognition and processing. J Immunol 195, 2842–2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Stamogiannos A, Papakyriakou A, Mauvais FX, van Endert P & Stratikos E (2016) Screening identifies thimerosal as a selective inhibitor of endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1. ACS Med Chem Lett 7, 681–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Papakyriakou A, Zervoudi E, Theodorakis EA, Saveanu L, Stratikos E & Vourloumis D (2013) Novel selective inhibitors of aminopeptidases that generate antigenic peptides. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 23, 4832–4836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Weglarz‐Tomczak E, Vassiliou S & Mucha A (2016) Discovery of potent and selective inhibitors of human aminopeptidases ERAP1 and ERAP2 by screening libraries of phosphorus‐containing amino acid and dipeptide analogues. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 26, 4122–4126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Albiston AL, Diwakarla S, Fernando RN, Mountford SJ, Yeatman HR, Morgan B, Pham V, Holien JK, Parker MW, Thompson PE et al (2011) Identification and development of specific inhibitors for insulin‐regulated aminopeptidase as a new class of cognitive enhancers. Br J Pharmacol 164, 37–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Albiston AL, Morton CJ, Ng HL, Pham V, Yeatman HR, Ye S, Fernando RN, De Bundel D, Ascher DB, Mendelsohn FA et al (2008) Identification and characterization of a new cognitive enhancer based on inhibition of insulin‐regulated aminopeptidase. FASEB J 22, 4209–4217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Diwakarla S, Nylander E, Grönbladh A, Vanga SR, Khan YS, Gutiérrez‐de‐Terán H, Ng L, Pham V, Sävmarker J, Lundbäck T et al (2016) Binding to and inhibition of insulin‐regulated aminopeptidase by macrocyclic disulfides enhances spine density. Mol Pharmacol 89, 413–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ashkenazy H, Abadi S, Martz E, Chay O, Mayrose I, Pupko T & Ben‐Tal N (2016) ConSurf 2016: an improved methodology to estimate and visualize evolutionary conservation in macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res 44, W344–W350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]