Abstract

Background and study aims Accurate diagnosis and risk stratification of pancreatic cysts (PCs) is challenging. The aim of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the feasibility, safety, and diagnostic yield of endoscopic ultrasound-guided through-the-needle biopsy (TTNB) versus fine-needle aspiration (FNA) in PCs.

Methods Comprehensive search of databases (PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane, Web of Science) for relevant studies on TTNB of PCs (from inception to June 2019). The primary outcome was to compare the pooled diagnostic yield and concordance rate with surgical pathology of TTNB histology and FNA cytology of PCs. The secondary outcome was to estimate the safety profile of TTNB. Results: Eight studies (426 patients) were included. The diagnostic yield was significantly higher with TTNB over FNA for a specific cyst type (OR: 9.4; 95 % CI: [5.7–15.4]; I 2 = 48) or a mucinous cyst (MC) (OR: 3.9; 95 % CI: [2.0–7.4], I 2 = 72 %). The concordance rate with surgical pathology was significantly higher with TTNB over FNA for a specific cyst type (OR: 13.5; 95 % CI: [3.5–52.3]; I 2 = 48), for a MC (OR: 8.9; 95 % [CI: 1.9–40.8]; I 2 = 29), and for MC histologic severity (OR: 10.4; 95 % CI: [2.9–36.9]; I 2 = 0). The pooled sensitivity and specificity of TTNB for MCs were 90.1 % (95 % CI: [78.4–97.6]; I 2 = 36.5 %) and 94 % (95 % CI: [81.5–99.7]; I 2 = 0), respectively. The pooled adverse event rate was 7.0 % (95 % CI: [2.3–14.1]; I 2 = 82.9).

Conclusions TTNB is safe, has a high sensitivity and specificity for MCs and may be superior to FNA cytology in risk-stratifying MCs and providing a specific cyst diagnosis.

Introduction

Pancreas cysts (PCs) are being diagnosed with increasing frequency given the widespread use of cross-sectional imaging in our health care system 1 . PCs can be broadly categorized as either non-neoplastic or neoplastic, with the latter being estimated as high as 13.5 % in the general population 2 . Accurate diagnosis and risk stratification of neoplastic cysts are crucial as to provide guidance for the most appropriate management strategy.

The optimal diagnostic approach to PCs remains unclear as there is currently no single test that can reliably differentiate non-neoplastic PCs from those lesions with malignant potential or harboring malignancy. Given the well-recognized limitations of imaging alone 2 3 4 , EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) for cytology and cyst fluid analysis is the commonly performed guideline endorsed test for aid with diagnosis and risk stratification 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 . FNA cytology is often limited by the scant cellularity within the cyst fluid 11 12 . While cyst fluid carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) has been traditionally used to differentiate mucinous versus non-mucinous PCs 13 , it has modest diagnostic accuracy and does not discriminate between benign and malignant mucinous cysts 14 15 .

Recently, a through-the-needle microforceps device (Moray Microforceps, US Endoscopy, Mentor, Ohio, United States) was introduced for EUS-guided tissue sampling of PCs. The microforceps can be advanced through the lumen of a standard 19-gauge EUS-FNA needle for through-the-needle tissue biopsy (TTNB) of PCs. Since its introduction, there have been several studies reporting on the performance of the TTNB 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 . We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of the current literature to better assess the feasibility, safety, and diagnostic yield of TTNB as compared to EUS-FNA in the evaluation of PCs.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a comprehensive search of four electronic databases (MEDLINE through Pubmed, EMBASE, Cochrane, and Web of Science) for all relevant studies with the last search performed in July 2019. The search was performed with the assistance of an experienced medical librarian.

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines were followed. Key terms used in the search query included a combination of the following: “Endoscopic ultrasound-guided through the needle microforceps”, “microforceps”, “micro-forcep”, “pancreas AND microforceps”, “through the needle”, (“pancreas AND through the needle,”) (“pancreas” AND “through the needle” AND “EUS”), (“pancreatic cysts” AND “through the needle”), (“pancreatic cyst” AND “moray”), “moray micro-forceps,” (“microforceps” AND “pancreas”). We attempted to identify additional studies by reviewing the reference list of all included studies and by manual search in order to retrieve other articles that may have been missed on the initial search strategy. Using the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, two investigators (S.P., D.W.) independently screened the title and abstract of all studies identified in the primary search. The full text of all relevant studies was subsequently reviewed. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus and by discussion with the co-authors (P.V.D., D.Y.).

Study selection

All studies were screened based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies were included if they: (1) were retrospective or prospective, case-control or cohort studies and clinical trials (including randomized controlled trials); (2) reported EUS-TTNB of pancreas cysts; and (3) included data on cytology and/or histology for EUS-TTNB. Studies were excluded if: (1) they included fewer than five cases; (2) animal studies; (3) EUS-TTNB was performed in non-cystic pancreatic lesions, (3) cytologic or histological diagnosis for EUS-TTNB was not provided; or (4) were publications in a language other than English.

In the case of publications from the same group of authors, we contacted the authors as to determine whether these were from the same cohort. If publications were from the same cohort or if this could not be verified, then only data from the most recent and/or most comprehensive study was included. In our search query, we encountered one such study by Kovacevic et al 20 .

Data extraction and quality assessment

Three investigators (S.P., D.W., D.Y.) independently extracted data from each study by using a standardized data collection form, which included: (1) study author; (2) year of publication; (3) study period; (4) patient demographics; (5) pancreatic cyst characteristics (i. e. size, morphology, location); (6) cyst fluid analysis; (7) cytology from EUS-FNA; (8) histology from EUS-TTNB (9) adverse events (AES); and (10) surgical pathology.

Contingency 2 × 2 tables were constructed with information of true positive, false positive, true negative, and false negative for TTNB discrimination between mucinous and non-mucinous cysts, with surgical pathology as the reference standard.

The quality of the studies was assessed by using a modified Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies 29 . The modified NOS consisted of 6 components: representative of the average population (1 point for population-based studies, 0.5 point for multi-center studies, 0 point for single-center hospital-based study), large cohort size (1 point > 50 patients, 0.5 point for 30–49 patients, and 0 point < 30 patients); information on how a mucinous cyst was diagnosed (1 point if reported with clarity; 0 point if not reported); information on the specific cyst diagnosis obtained by FNA and TTNB (1 point if reported for both; 0.5 if reported for either FNA or TTNB, 0 point if not reported); information on AEs (1 point if reported, 0 point if not reported); information on concordance between FNA, TTNB and surgical pathology (1 point if reported, 0.5 if reported for either FNA or TTNB, 0 point if not reported). Studies with scores ≥ 5, 3–4, and ≤ 2 were suggestive of high, moderate, and low quality, respectively.

Study aim and definitions

The primary aim of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the feasibility, safety, and diagnostic yield of EUS-TTNB versus FNA in PCs. A secondary aim was to determine the pooled sensitivity and specificity of TTNB for mucinous cysts. Technical feasibility was defined as successful passage of the microforceps through the indwelling EUS needle and completion of intended tissue acquisition (EUS-TTNB). Diagnostic yield was defined as the number of cases in which a diagnosis was attained divided by the total of number of cases. The concordance rate was defined as the number of cases in which TTNB or FNA matched the final surgical diagnosis divided by the total number of surgical specimens for that category. TTNB diagnostic accuracy parameters for mucinous cysts were calculated from eligible studies by using the surgical pathology as the reference standard. AEs were defined as any deviation from the expected post-procedural clinical course. Intracystic hemorrhage was defined as the presence of blood within a cyst as identified on EUS or subsequent cross-sectional imaging.

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed with Review Manager 5.2 (RevMan, The Nordic Cochrane Center, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012) for computation of comparative forest plots and funnel plots. Pooled proportions were calculated from the weighted means of individual proportions and funnel plots were calculated using STATA (Stata Statistical Software, STATA 15, College Station, Texas, United States). Subgroup analysis were also performed to compare EUS-TTNB verses EUS-FNA and reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95 % confidence intervals (CI) calculated using the Mantel-Haenszel method. The heterogeneity estimate of the studies was calculated using the Cochran Q test I 2 statistic. Values of < 30 %, 30 % to 60 %, 61 % to 75 %, and > 75 % were considered low, moderate, substantial, and considerable heterogeneity, respectively 30 . A fixed- or random-effects model was applied based on heterogeneity. In the eligible studies, the pooled sensitivity and specificity was calculated. A receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve could not be calculated as none of the studies included reported false positive results for TTNB in the diagnosis of mucinous cysts. Funnel plots were visually inspected for publication bias; Egger’s test was not performed to test for funnel plot asymmetry as this is not appropriate for meta-analysis with less than 10 studies 31 32 33 .

Results

Search results

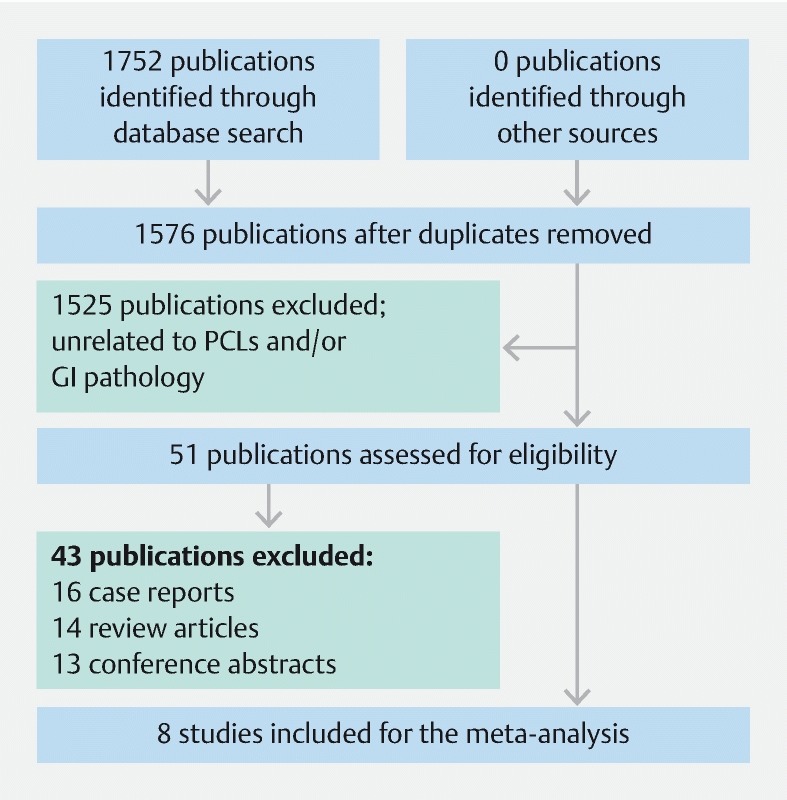

Our primary search strategy yielded 1752 studies, of which 176 were duplicates. Of the remaining 1576 publications, 1525 were excluded after screening titles and abstracts. Full text review was subsequently performed on 51 studies using our predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eight studies with a total of 426 cases were included in the final meta-analysis 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 . The study flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flowchart of included studies. From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

Study characteristics and quality assessment

Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1 . All articles were cohort studies (7 retrospective and 1 prospective), study period between 2014 to 2018, and originating from the United States (n = 5) or Europe (n = 3). The mean age ranged between 50 to 70 years with 59.9 % (255 out of 426) being female. Most studies reported a mean pancreas cyst size between 28.2 mm to 40.7 mm. Pancreas cyst location was reported in all studies except by Kovacevic et al 19 . Most cysts were primarily located in the body/tail (64.6 %) followed by head/uncinated process (35.4 %). The median number of passes for EUS-TTNB was three, with two studies reporting tissue acquisition until a visible specimen was obtained 22 26 .

Table 1. Study characteristics.

| Study | Study design | Patients (n) | Age (years) | Gender | Pancreas cyst (mm) | Cyst location | Unilocular/septated | CEA ≥ 192 ng/mL n, (%) | # Passes for TTNB | Patients who underwent surgery n (%) | ||

| Male | Female | head/uncinated | Body/tail | |||||||||

| Barresi 2018 21 | MC Retrospective | 56 | 58 | 17 | 39 | Mean 38.6 (range 16–55) | 24 | 32 | 32/24 | 18 (32.1 %) | Mean 3.1 (range 1–5) | 15 (26.8 %) |

| Basar 2018 22 | MC Retrospective | 42 | 69 | 19 | 23 | Mean 28.2 (range 12–60) | 16 | 26 | 17/25 | 12 (28.6 %) | Until visible tissue obtained | 7 (16.7 %) |

| Kovacevic 2018 23 | SC Retrospective | 31 | 70 | 16 | 15 | Median 30 (range 12–130) | NR | NR | NR | 6 (19.4 %) | Median 3 (IQR 2–4) | 4 (12.9 %) |

| Mittal 2018 24 | SC Retrospective | 27 | 65 | 11 | 16 | Mean 37.8 (15–70) | 14 | 13 | NR | 12 (44.4 %) | Mean 3.7 (range 1–7) | 5 (18.5 %) |

| Yang 2018 25 | MC Retrospective | 47 | 66 | 21 | 26 | Mean 30.8 (11.6–110) | 16 | 31 | 16/35 | 9 (19.1 %) | Median 3 (IQR 2–4) | 8 (17.0 %) |

| Zhang 2018 26 | SC Retrospective | 48 | 70 | 23 | 25 | Mean 31 (range 12–60) | 13 | 35 | NR | 13 (27.1 %) | Until visible tissue obtained | 10 (20.8 %) |

| Yang 2019 27 | MC Prospective | 114 | 64 | 50 | 64 | Mean 35.1 (IQR 20–41) | 39 | 75 | 68/36 | 32 (28.1 %) | Median 3 (IQR 2–4) | 23 (20.2 %) |

| Crino 2019 28 | SC Retrospective | 61 | 50 | 14 | 47 | Mean 40.7 (range 16–75) | 18 | 43 | 34/27 | N/A | Median 3 (range 2–5) | 20 (32.8 %) |

CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; MC, multicenter; SC, single center; IQR, interquartile range

The quality of the studies was assessed by using the modified NOS scale as shown in Table 2 . None of the studies were population based; with equal number of single center (n = 4) and multicenter (n = 4) studies. Three studies had > 50 patients 21 27 28 , four studies included 30–49 patients 22 23 25 26 , and one study < 30 patients 24 . Six out of the eight studies provided clear definitions on how a mucinous cyst was diagnosed 21 22 25 26 27 28 . Six of the 8 studies provided information on the specific cyst type diagnosis obtained via TTNB and FNA 22 23 24 25 26 27 . All studies provided information on adverse events. Six of the eight studies provided information on FNA cytology, TTNB histology and the corresponding surgical pathology. Overall, three studies were considered to be of high quality 22 25 28 , five of medium quality 21 23 24 26 28 , and none of low quality.

Table 2. Study quality assessment using the modified Newcastle Ottawa Scale.

| Study | Representative of average population | Cohort Size | Information on how a mucinous cyst was diagnosed | Information on specific diagnosis by FNA and TTNB | Information on adverse events | Data on TTNB, FNA and corresponding surgical pathology | Total |

| Barresi 2018 21 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 4.5 |

| Basar 2018 22 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Kovacevic 2018 23 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Mittal 2018 24 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3.5 |

| Yang 2018 25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Zhang 2018 26 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3.5 |

| Yang 2019 27 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5.5 |

| Crino 2019 28 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 4.5 |

FNA, fine-needle aspiration; TTNB, through-the-needle biopsy

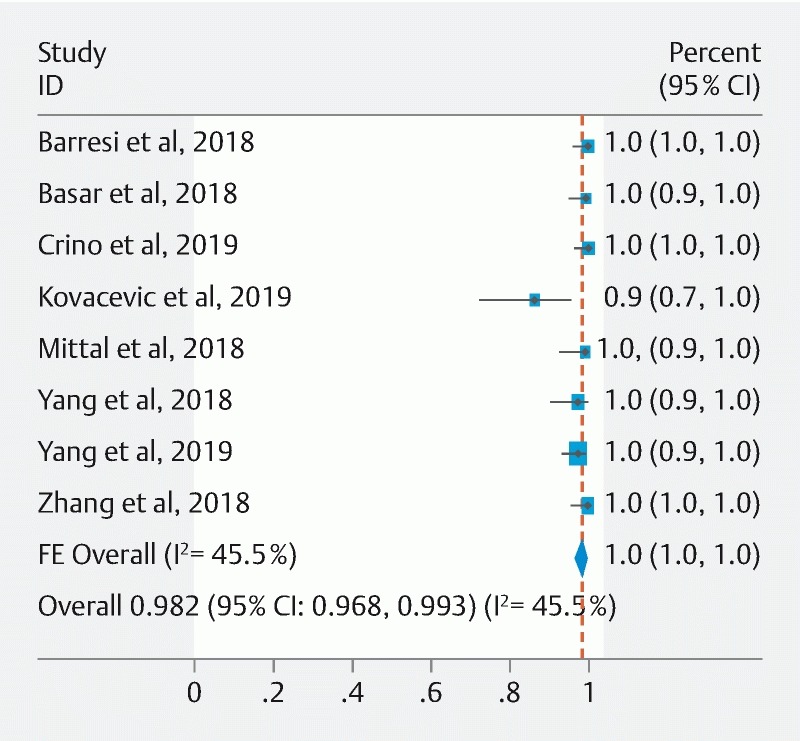

Feasibility of EUS-TTNB in the evaluation of pancreatic cysts

In all, EUS-TTNB was successfully performed in 418 of 426 cases, for a pooled technical success of 98.2 % (95 % CI: [96.8–99.3 %]; I 2 = 45.5) ( Fig. 2 ). EUS-TTNB failed in five cases because the microforceps could not be advanced through the angulated EUS-FNA needle via a transduodenal approach 23 25 . In the remainder three cases, EUS-TTNB was not performed due to the presence of interposing vessels between the EUS needle and cyst (n = 1), as a result of insufficient sedation and transient hypoxia prior to EUS-TTNB (n = 1), or in the setting of a bloody aspirate with EUS-FNA (n = 1) 25 28 .

Fig. 2.

Pooled technical success of EUS-TTNB in the evaluation of pancreatic cysts (Fixed-effect Model).

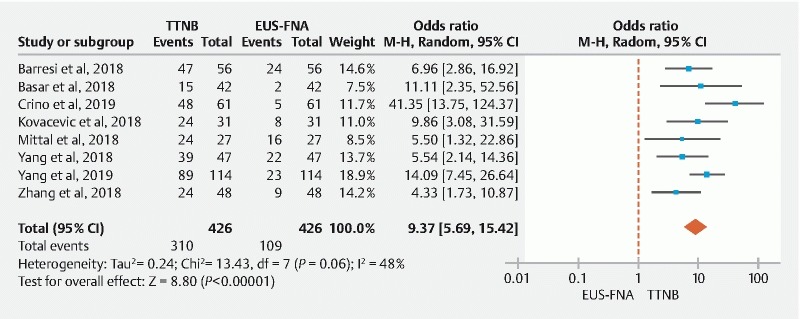

Diagnostic yield of TTNB versus FNA in pancreas cysts

Specific cyst type

The specific cyst type diagnosis obtained via TTNB histology and FNA cytology from all the studies in this meta-analysis are summarized in Table 3 . The pooled diagnostic yield for a specific cyst type was significantly higher with TTNB histology (72.5 %; 95 % CI: [60.6–83.0]) than FNA cytology (38.1 %; 95 % CI: [18.0–60.5]). Furthermore, in comparator analysis the diagnostic yield was significantly higher with TTNB compared to FNA (OR: 9.37; 95 % CI: [5.69–15.42]), with moderate heterogeneity among the studies (I 2 = 48) ( Fig. 3 ).

Table 3. Specific cyst type diagnoses obtained via TTNB histology and FNA cytology 1 .

| Study | ||||||||||||||||

| Diagnosis | Barresi 2018 21 | Basar 2018 22 | Kovacevic 2018 23 | Mittal 2018 24 | Yang 2018 25 | Zhang 2018 26 | Yang 2019 27 | Crino 2019 28 | ||||||||

| FNA | TTNB | FNA | TTNB | FNA | TTNB | FNA | TTNB | FNA | TTNB | FNA | TTNB | FNA | TTNB | FNA | TTNB | |

| Mucinous cyst | NS | 19 | 0 | 8 | 6 | 19 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 26 | 26 | 28 | 11 | 61 | NS | 23 |

| Fibrous non-epithelium/inflammatory cells (pseudocyst) | NS | 7 | – | – | 1 | 2 | 13 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 14 | NS | 2 | ||

| Serous cystadenoma | NS | 14 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 2 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | NS | 13 |

| Mucinous cyst with malignant transformation; adenocarcinoma | NS | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | NS | 0 |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | NS | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | 0 | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 6 | NS | 5 |

| Acinar cystadenoma | NS | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0 | 1 | – | – | NS | 0 |

| Benign glandular epithelium | NS | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 9 | 7 | – | – | 18 | 6 | NS | 0 |

| Solid pseudopapillary tumor | NS | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0 | 1 | NS | 1 |

| Squamoid cyst | NS | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | NS | 3 |

| Lymphangioma | NS | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | NS | 2 |

| Lymphoepithelial cyst | NS | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | NS | 1 |

| Undefined | NS | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | NS | 11 |

FNA, fine-needle aspiration; TTNB, through-the-needle biopsy; NS, not specified

Diagnosis was based on cyst fluid analysis and cytology

Fig. 3.

Pooled diagnostic yield of TTNB histology vs FNA cytology for a specific cyst type diagnosis (Random-Effect Model).

Mucinous cysts

The pooled diagnostic yield for a mucinous cyst was 56.2 % (95 % CI: [45.1–67.0]) with TTNB and 29.5 % (95 % CI: [15.5–45.9]) with FNA, respectively. Cyst fluid CEA levels were specified in 7 out of the 8 studies 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 . The pooled rate of PCs with CEA ≥ 192 ng/mL was 28.2 % (95 % CI: [23.7–32.8]). Overall, in comparator analysis the diagnostic yield for a mucinous cyst was significantly higher with TTNB histology when compared to either FNA cytology (OR: 3.86; 95 % CI: [2.0–7.44], I 2 = 72 %) ( Fig. 4a ) or CEA ≥ 192 ng/mL (OR: 2.94; 95 % CI: [1.66–5.21], I 2 = 67 %) ( Fig. 4b ).

Fig. 4 a.

Pooled diagnostic yield of TTNB histology vs FNA cytology for mucinous cysts (Random-Effect Model). b Pooled diagnostic yield of TTNB histology vs. cyst fluid CEA ≥ 192 ng/mL for mucinous cysts (Random-Effect Model). c Pooled diagnostic yield of TTNB histology vs FNA cytology for serous cystadenoma (Fixed-Effect Model).

Serous cystadenoma

Six studies provided information on serous cystadenoma based on both TTNB histology and FNA cytology 22 23 24 25 26 27 . Among these studies, the pooled diagnostic yield for a serous cystadenoma was significantly higher with TTNB (12.4 %; 95 % CI: [7.3–18.6]) as compared to FNA (1.2 %; 95 % CI: [0.3–2.5]). In comparator analysis, the diagnostic yield of a serous cystadenoma was greater with TTNB compared to FNA (OR: 5.35; 95 % CI: [2.02–14.16]), with low heterogeneity among the studies (I 2 = 0) ( Fig. 4c ).

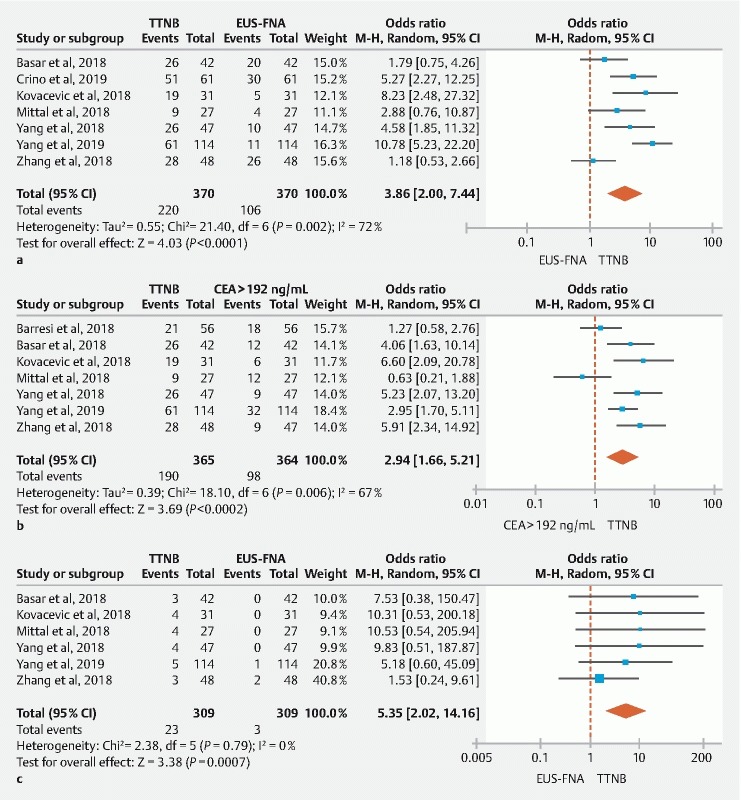

TTNB and FNA concordance with surgical pathology

Ninety two patients in the 8 studies included in this meta-analysis underwent surgery for their PCs. Six studies provided information on the respective TTNB histology and FNA cytology for each surgical pathology specimen 22 23 24 25 27 28 .

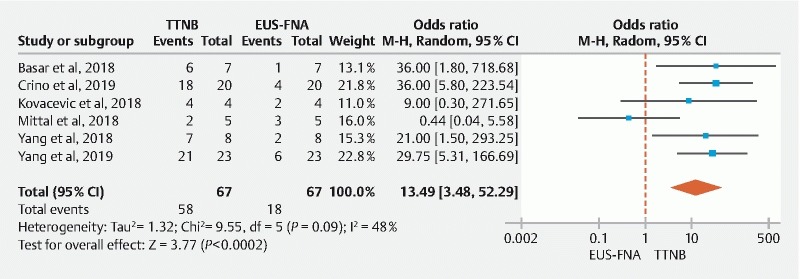

Diagnosis of specific cyst type

The pooled concordance of TTNB and FNA with surgical pathology for a specific cyst type were 82.3 % (95 % CI: [71.9–90.7]) and 26.8 % (95 % CI: [17.0–37.8]), respectively. Compared to FNA cytology, TTNB histology was significantly more likely (OR: 13.49; 95 % CI: [3.49–52.29]) to match the diagnosis on surgical pathology; with moderate heterogeneity between the studies (I 2 = 48 %) ( Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Pooled concordance of TTNB histology vs FNA cytology with surgical pathology for a specific cyst type (Random-Effect Model).

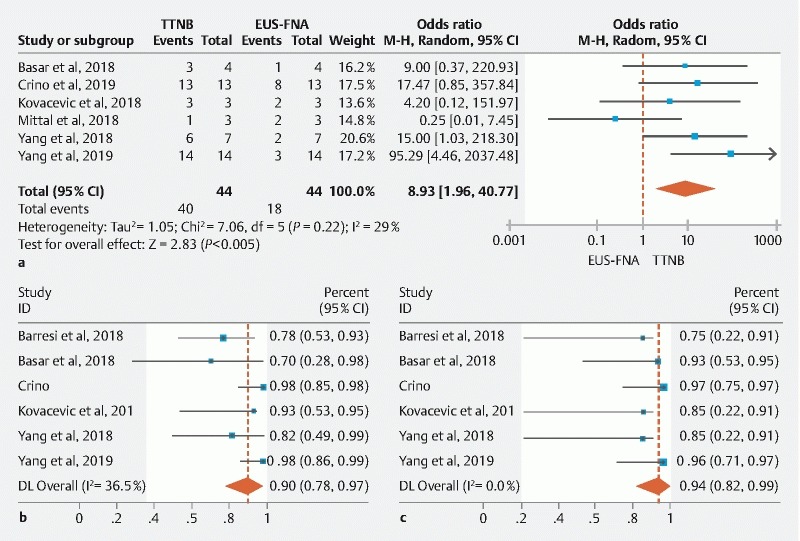

Diagnosis of mucinous cysts

The pooled concordance for mucinous cysts was also higher for TTNB (89 %; 95 % CI: [80.0–95.0]) vs FNA (41 %; 95 % CI: [28–55]). Compared to FNA, TTNB was significantly more likely (OR: 8.93; 95 % CI: [1.96–40.77]) to match the diagnosis of mucinous cyst with surgical pathology; with low heterogeneity detected (I 2 = 29 %) ( Fig. 6a ). Using the surgical pathology as the reference standard, the overall sensitivity and specificity of TTNB for mucinous cysts were 90.1 % (95 % CI: [78.4–97.6]; I 2 = 36.5 %) and 94 % (95 % CI: [81.5–99.7]; I 2 = 0), respectively ( Fig. 6b , Fig. 6c ).

Fig. 6 a.

Pooled concordance of TTNB histology vs FNA cytology with surgical pathology for a mucinous cyst (Random-Effect Model). b Pooled sensitivity of TTNB histology for diagnosing a mucinous cyst using surgical pathology as reference standard (Random-Effect Model). c Pooled specificity of TTNB histology for diagnosing a mucinous cyst using surgical pathology as reference standard (Fixed-Effect Model).

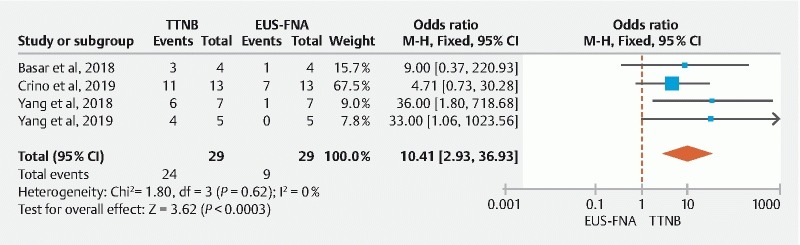

Diagnosis of histological grading of mucinous cysts

Four studies provided information on histological grading of mucinous cysts on TTNB histology, FNA cytology, and corresponding surgical pathology 22 25 27 28 . The pooled concordance with the histological grade of a mucinous cyst on surgical pathology was significantly higher with TTNB (75.6 %; 95 % CI: [62.3–86.8]) versus FNA (26 %; 95 % CI: [6.7–52.3]). Furthermore, TTNB in comparison to FNA was significantly more likely to match the histologic grade compared to surgical pathology (OR: 10.4; 95 % CI: [2.93–36.93]); with low heterogeneity (I 2 = 0) ( Fig. 7 ).

Fig. 7.

Pooled concordance of TTNB histology vs FNA cytology with histological grading of mucinous cysts on surgical pathology (Fixed-Effect Model)

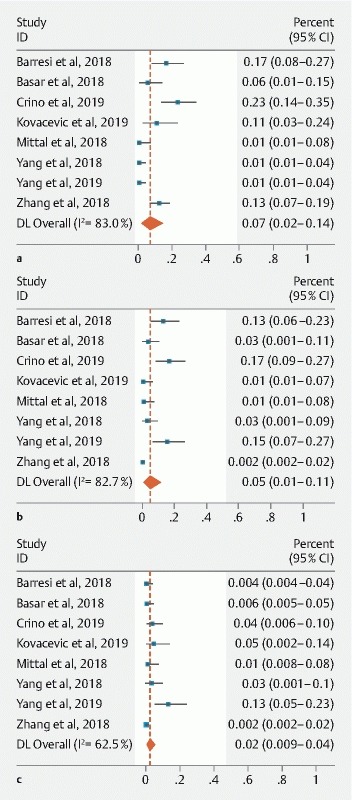

Adverse events

The pooled rate of AEs was 7.0 % (95 % CI: [2.3–14.1]; I 2 = 82.9) ( Fig. 8a ). The pooled occurrence for intracystic hemorrhage and acute pancreatitis were 5.0 % (95 % CI: [1.2–11.2]; I 2 = 82.6) and 2.3 % (95 % CI: [0.5–5.3]; I 2 = 62.5), respectively ( Fig. 8b , Fig. 8c ). None of the cases of intracystic hemorrhage required additional interventions. Among the 10 cases of acute pancreatitis reported, six did not require hospitalization 21 25 27 28 , three were discharged within 24 to 48 hours with supportive care 25 28 , whereas one developed a pseudocyst that required endoscopic drainage 27 .

Fig. 8 a.

Pooled adverse events with TTNB of pancreatic cysts. b Pooled occurrence of intracystic hemorrhage with TTNB of pancreatic cysts. c Pooled occurrence of acute pancreatitis with TTNB of pancreatic cysts.

Publication bias

Funnel plots have been included in the supplementary material ( Supplementary Fig. 9 ). There was no evidence of substantial publication bias on visual inspection of the funnel plots for any of the analyses except for the calculation of the pooled concordance rate between TTNB, FNA and surgical pathology for a specific cyst type diagnosis, which is in part due to precision bias being skewed by the two larger studies favoring TTNB histology concordance with surgical pathology 27 28 .

Discussion

Accurate diagnosis and risk stratification of PCs is of utmost importance as it may allow the early detection and management of PCs with malignant potential, while limiting unnecessary interventions in most inconsequential benign PCs. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we evaluated the performance of TTNB of PCs using a novel microforceps device.

The overall estimated pooled technical success of TTNB with the microforceps was very high (98.2 %), supporting its applicability in the diagnosis of a broad range of PCs, irrespective of cyst size or location. The microforceps device permits targeted tissue acquisition from the cyst wall, septations and/or mural nodules for histological evaluation, which in turn, potentially increases the likelihood of obtaining a specific cyst diagnosis as compared to FNA cytology. In this meta-analysis, the overall diagnostic yield for a specific cyst type was significantly higher with TTNB versus FNA (OR: 9.37; CI: [5.7–15.4]). The superior diagnostic yield of TTNB for a specific cyst type was further supported in this meta-analysis by the overall higher concordance of TTNB over FNA (OR: 13.49; CI: [4.5–52.3]) for a specific cyst diagnosis on surgical pathology. Differentiating between specific cyst types has significant clinical implications. For instance, SCAs are benign lesions that do not necessitate surveillance or intervention in the absence of symptoms. However, previous studies have demonstrated that FNA cytology has a low sensitivity for the diagnosis of SCA 34 35 . Our results demonstrated that the diagnostic yield for serous cystadenoma was also significantly higher with TTNB as compared to FNA (OR: 5.35; CI: [2.0–14.2]). In aggregate, these findings suggest that TTNB can be helpful when elucidating a specific cyst type may impact subsequent care.

The limitations of EUS-FNA for the evaluation of mucinous cysts are well-recognized 4 11 12 and additional modalities are much needed to improve our diagnostic ability. In this study, the diagnostic yield for mucinous cysts was significantly higher with TTNB histology when compared to either FNA cytology (OR: 3.86; CI: [2.0–7.4]) or cyst fluid CEA ≥ 192 ng/mL (OR: 2.94; CI:[1.7–5.2]). Using surgical pathology as the reference standard, the pooled sensitivity and specificity of TTNB for mucinous cysts were 90.1 % and 94 %, respectively; with low heterogeneity among the studies. Indeed, our data demonstrated that TTNB was nearly 9-fold more likely to diagnose a mucinous cyst when compared to FNA cytology (OR: 8.93; CI: [2.0–40.8]); and hence, should be entertained as part of the multi-modality approach in the evaluation of PCs.

Accurate risk stratification of mucinous cysts is perhaps the most important yet also the most challenging step in the management of PCs. Cyst fluid analysis is not helpful as neither CEA nor molecular mutations correlate with histological grade. While relatively specific, the diagnostic accuracy of FNA cytology is often hindered by the suboptimal cellular specimen obtained from PCs 11 36 . In this meta-analysis, we demonstrate that the concordance rate with the histological grade among surgically resected mucinous cysts was 10-fold higher with TTNB histology when compared to FNA cytology (OR 10.41; CI: [2.9–37.0]) with low heterogeneity. Given the high rate of tissue adequacy for histological grading, TTNB may prove to add significant value, particularly when triaging patients with no overt “high-risk” cyst features.

The estimated pooled occurrence of AEs associated with TTNB was 7 %, with the calculated rate of intracystic hemorrhage and acute pancreatitis being 5 % and 2.3 %, respectively. Given the lack of current data to evaluate for risk factors, we can only speculate that the more aggressive mode of tissue acquisition with TTNB may account for the higher rates of adverse events. The study by Crino et al 28 suggests that two TTNB macroscopically visible specimens allowed reaching a 100 % histological adequacy and therefore additional attempts at TTNB may not improve the yield but rather increase the risk of AEs. Further studies are needed to help define not only the optimal number of passes but also the preferred tissue acquisition technique with this device.

This study has several strengths. We performed a systematic literature search that was comprehensive with well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the quality of the studies was rigorously assessed based on the pre-defined parameters in the modified NOS. All subjects in the included studies underwent both EUS-FNA and TTNB for the comparative outcome measures, thereby serving as their own control and reducing variance. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that we strictly used surgical pathology as the reference criterion when calculating the diagnostic accuracy of TTNB for mucinous cysts. We also acknowledge the limitations. Most included studies were small in sample size and retrospective in design, thereby contributing to selection and reporting bias. Furthermore, publication bias was observed for some of the subgroup calculations in this meta-analysis, primarily driven by the small cohort size of each study and the limited number of studies available. In addition, all studies were performed at tertiary care referral centers and thus not representative of the general population. TTNB is not regarded as a standard method in the evaluation of pancreatic cysts, and additional data are needed to further determine its role in the diagnostic algorithm of these lesions. In addition, while our data suggested higher odds of obtaining a correct diagnosis with TTNB as compared to FNA, these results should be interpreted with caution given the large confidence intervals. There was considerable heterogeneity among the studies in the overall analysis comparing diagnostic yield of TTNB vs FNA for specific cyst type, mucinous cyst, and the estimated adverse event rate with TTNB. Possible explanations include variability in: (1) indications for EUS-FNA and TTNB; (2) cyst sampling technique and number of passes for FNA cytology and TTNB histology; (3) pancreas cyst size and morphology; (4) inclusion of cyst fluid analysis and cytology for the evaluation of FNA performance 26 ; and (5) patient follow-up post-procedure. We were not able to further evaluate the data based on these parameters given that most studies were inconsistent in the reporting of this information and when available, the outcomes were not categorized according to these findings. Even though a meta-regression analysis could not be performed for these reasons, no evidence of significant heterogeneity was found with regards to the diagnostic accuracy of TTNB for mucinous cysts or in its superiority over FNA in its correlation with a diagnosis of mucinous cyst and histological grade using surgery as reference standard.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our meta-analysis demonstrates that TTNB has a high sensitivity and specificity for distinguishing mucinous from non-mucinous cysts and may be superior to FNA cytology in risk stratifying mucinous cysts and providing a specific cyst diagnosis. Future well-designed comparative studies between TTNB and FNA in the evaluation of PCs are needed to corroborate these results.

Footnotes

Competing interests Dr. Draganov is a consultant for Boston Scientific, Olympus, Cook Medical, Lumendi and Microtech. Dr. Yang is a consultant for US Endoscopy, Boston Scientific, Lumendi and Steris.

Supplementary material :

References

- 1.Lee K S, Sekhar A, Rofsky N M et al. Prevalence of incidental pancreatic cysts in the adult population on MR imaging. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2079–2084. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khashab M A, Kim K, Lennon A M et al. Should we do EUS/FNA on patients with pancreatic cysts? The incremental diagnostic yield of EUS over CT/RMI for prediction of cystic neoplasms. Pancreas. 2013;42:717–721. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182883a91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Visser B C, Yeh B M, Qayyum A et al. Characterization of cystic pancreatic masses: relative accuracy of CT and MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;189:648–656. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alkaade S, Chahla E, Levy M. Role of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration, cytology, viscosity, and carcinoembryonic antigen in pancreatic cyst fluid. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:299–303. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.170417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brugge W R. The use of EUS to diagnose cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:S203–S209. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brugge W R, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1330–1336. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vege S S, Ziring B, Jain R et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Diagnosis and Management of Asymptomatic Neoplastic Pancreatic Cysts. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:819–822. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka M, Fernandez-del-Castillo C, Kamisawa T et al. Revisions of international consensus Fukuoka guidelines for the management of IPMN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2017;17:738–753. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elta G H, Enestvedt B K, Sauer B G et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Pancreas Cysts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:464–479. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2018.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Study Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas . European evidence-based guidelines on pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Gut. 2018;67:789–804. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Jong K, Poley J W, van Hooft J E et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of pancreatic cystic lesions provides inadequate material for cytology and laboratory analysis: initial results from a prospective study. Endoscopy. 2011;43:585–590. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Attasaranya S, Pais S, LeBlanc J et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration and cyst fluid analysis for pancreatic cysts. JOP. 2007;8:553–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brugge W R, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1330–1336. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park W G, Mascarenhas R, Palaez-Luna M et al. Diagnostic performance of cyst fluid carcinoembryonic antigen and amylase in histologically confirmed pancreatic cysts. Pancreas. 2011;40:42–45. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181f69f36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaddam S, Ge P S, Keach J W et al. Suboptimal accuracy of carcinoembryonic antigen in differentiation of mucinous and nonmucinous pancreatic cysts: results of a large multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:1060–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samarasena J B, Nakai Y, Shinoura S et al. EUS-guided, through-the-needle forceps biopsy: a novel tissue acquisition technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:225–226. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coman R M, Schlachterman A, Esnakula A K et al. EUS-guided through-the-needle forceps: clenching down the diagnosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:372–373. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.03.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Attili F, Pagliari D, Rimbas M et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided histological diagnosis of a mucinous non-neoplastic pancreatic cyst using a specially designed through-the-needle microforceps. Endoscopy. 2016;48:E188–E189. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-108194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huelsen A X, Cooper C X, Saad N X et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided, through-the-needle forceps biopsy in the assessment of an incidental large pancreatic cystic lesion with prior inconclusive fine-needle aspiration. Endoscopy. 2017;49:E109–E110. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-100217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kovacevic B, Karstensen J G, Havre R F et al. Initial experience with EUS-guided microbiopsy forceps in diagnosing pancreatic cystic lesions: A multicenter feasibility study (with video) Endosc Ultrasound. 2018;7:383–388. doi: 10.4103/eus.eus_16_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barresi L, Crino S F, Fabbri C et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-through-the-needle biopsy in pancreatic cystic lesions: A multicenter study. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:760–770. doi: 10.1111/den.13197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basar O, Yuksel O, Yang D et al. Feasibility and safety of micro-forceps biopsy in the diagnosis of pancreatic cysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovacevic B, Klausen P, Hasselby J P. A novel endoscopic ultrasound-guided through-the-needle microbiopsy procedure improves diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions. Endoscopy. 2018;50:1105–1111. doi: 10.1055/a-0625-6440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mittal C, Obuch J C, Hammad H et al. Technical feasibility, diagnostic yield, and safety of microforceps biopsies during EUS evaluation of pancreatic cystic lesions (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:1263–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang D, Samarasena J B, Jamil L H et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided through-the-needle microforceps biopsy in the evaluation of pancreatic cystic lesions: a multicenter study. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E1423–E1430. doi: 10.1055/a-0770-2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang M L, Arpin R N, Brugge W R et al. Moray micro forceps biopsy improves the diagnosis of specific pancreatic cysts. Cancer Cytopathol. 2018;126:414–420. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang D, Trindade A J, Yachimski P et al. Histologic analysis of endoscopic ultrasound- guided through the needle microforceps biopsies accurately identifies mucinous pancreas cysts. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1587–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crino S F, Bernardoni L, Brozzi L et al. Association between macroscopically visible tissue samples and diagnostic accuracy of EUS-guided through-the-needle microforceps biopsy of pancreatic cystic lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90:933–943. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guyatt G H, Oxman A D, Kunz R et al. GRADE guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence – inconsistency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:1294–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Easterbrook P J, Gopalan R, Berlin J A et al. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet. 1991;337:867–872. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90201-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lau J, Ioannidis J P, Terrin N et al. The case of the misleading funnel plot. BMJ. 2006;333:597–600. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7568.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins J PT, Green S. Chichester, West Sussex; Hoboken NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lilo M T, VandenBussche C J, Allison B D et al. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: potentials and pitfalls of a preoperative cytopathologic diagnosis. Acta Cytol. 2017;61:27–33. doi: 10.1159/000452471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belsey N A, Pitman M B, Lauwers G Y et al. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: limitations and pitfalls of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Cancer. 2008;114:102–110. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pitman M B, Centeno B A, Genevay M et al. Grading epithelial atypia in endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: an international observer concordance study. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121:729–736. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.