Abstract

Background:

The misuse of benzodiazepine tranquilizers is prevalent and is associated with increased risk of overdose when combined with other substances. Yet, little is known about other substance use among those who misuse tranquilizers.

Objectives:

This study characterized subgroups of individuals with tranquilizer misuse, based on patterns of polysubstance use.

Methods:

Data were extracted from the 2015-2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health; adults with past-month tranquilizer misuse were included (N=1,253). We utilized latent class analysis to identify patterns of polysubstance use in the previous month.

Results:

We identified three distinct latent classes, including the: (1) limited polysubstance use class (approximately 54.6% of the sample), (2) binge alcohol and cannabis use class (28.5% of the sample), and (3) opioid use class (16.9% of the sample). The binge alcohol and cannabis use class and the opioid use class were characterized by high probabilities of other substance misuse, including cocaine and prescription stimulants. Those in the binge alcohol and cannabis use class and the opioid use class reported more motives for tranquilizer misuse and higher rates of sexually transmitted infection, criminal involvement, and suicidal ideation. Those in the opioid use class also had greater psychological distress and higher rates of injection drug use.

Conclusions:

Nearly half of those with tranquilizer misuse in a general population sample were categorized into one of two high polysubstance use classes, and these two classes were associated with poorer functioning. Findings from these analyses underscore the need to reduce polysubstance use among those who misuse tranquilizers.

Keywords: tranquilizers, benzodiazepines, polysubstance use, concurrent substance use, National Survey on Drug Use and Health

Introduction

In 2017, approximately 2.2% of United States (U.S.) citizens ages 12 and older misused benzodiazepines and other tranquilizers (e.g., buspirone, cyclobenzaprine), with misuse defined as use at a higher dose/frequency than prescribed, for other reasons than prescribed, or without a prescription. Accordingly, tranquilizers were the third most commonly misused illicit or prescription substance, following cannabis and opioid analgesics. (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018b). Overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines, often in combination with other substances, increased more than 300% from 2002-2015 (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2017). Despite the prevalence of benzodiazepine misuse and the risks of combining benzodiazepines with other substances (Gudin, Mogali, Jones, & Comer, 2013), little is known about heterogeneity in patterns of polysubstance use among those with tranquilizer misuse (Votaw, Geyer, Rieselbach, & McHugh, 2019). The aim of the present study was to characterize adults with tranquilizer misuse in the general population, based on patterns of polysubstance use. The term ‘polysubstance use’ refers to the use of more than one substance over a defined period (Connor, Gullo, White, & Kelly, 2014; Liu, Williamson, Setlow, Cottler, & Knackstedt, 2018).

In the general population, the use of multiple substances and other substance use disorders increase risk of tranquilizer misuse (Blanco, Han, Jones, Johnson, & Compton, 2018; Maust, Lin, & Blow, 2019; Schepis, Teter, Simoni-Wastila, & McCabe, 2018). Rates of tranquilizer misuse are approximately 4 and 39 times greater, respectively, among those with alcohol use disorder and opioid use disorder, as compared to the general population (Votaw, Witkiewitz, Valeri, Bogunovic, & McHugh, 2019). Elevated rates of tranquilizer misuse among those with substance use disorders might be partly explained by the many functions that these medications can serve in this population. Co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders are common among those with substance use disorders (Lai, Cleary, Sitharthan, & Hunt, 2015), and psychological distress increases risk of tranquilizer misuse (Blanco et al., 2018; McHugh, Geyer, Karakula, Griffin, & Weiss, 2018; McHugh et al., 2017; Schepis et al., 2018). Indeed, tranquilizers are most commonly misused to reduce negative affective (e.g., anxiety) and somatic (e.g., insomnia) states (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018b). However, individuals with opioid misuse report additional motives for tranquilizer misuse, including use to get high, to cope with withdrawal, and to modify the effects of other substances (Mateu-Gelabert et al., 2017; Stein, Kanabar, Anderson, Lembke, & Bailey, 2016).

Not only is tranquilizer misuse highly prevalent among those with substance use disorders, but misuse is also associated with concerning consequences in this population. Benzodiazepine misuse has been associated with opioid overdose (Moses, Lundahl, & Greenwald, 2018; Stein, Anderson, Kenney, & Bailey, 2017), infectious disease (Bach et al., 2016; Ickowicz et al., 2015), risky sexual behavior/risky injection practices (Ickowicz et al., 2015; Tucker et al., 2016), criminal involvement (Comiskey, Stapleton, & Kelly, 2012; Darke et al., 2010; Horyniak et al., 2016), suicidal ideation/attempt (Artenie, Bruneau, Roy, et al., 2015; Artenie, Bruneau, Zang, et al., 2015), and continued substance use during treatment (Darke et al., 2010; Naji et al., 2016). Explanations for these associations are largely unclear. Some authors have posited that benzodiazepine misuse might increase risk of these consequences by acute decreases in inhibition (Artenie, Bruneau, Roy, et al., 2015; Artenie, Bruneau, Zang, et al., 2015), and that greater psychological severity among those with benzodiazepine misuse is associated with poorer outcomes (Artenie, Bruneau, Roy, et al., 2015; Artenie, Bruneau, Zang, et al., 2015; Naji et al., 2016). It is also plausible that greater substance use involvement (i.e., polysubstance use) among those with tranquilizer misuse could explain the associations between misuse and negative consequences (Votaw, Geyer et al., 2019), but this hypothesis has not been systematically investigated.

We aimed to address several gaps in the literature on tranquilizer misuse. Despite robust evidence that those who use other substances are the most vulnerable to tranquilizer misuse (Votaw, Geyer et al., 2019), few studies have examined patterns of polysubstance use among those with tranquilizer misuse. Specifically, the concurrent and simultaneous use of benzodiazepines and opioids has been widely documented, but few studies have examined other substance use (e.g., alcohol, stimulants, etc.) among people who misuse tranquilizers. Previous studies have utilized latent class analysis (LCA) to identify patterns of past-year polysubstance use among those with alcohol dependence (Hedden et al., 2010) and prescription stimulant misuse (Chen et al., 2014) in the general population. Accordingly, we utilized LCA to identify patterns of polysubstance use among a general population sample of individuals with tranquilizer misuse. We chose a more tightly defined assessment period than previous studies (past-month vs. past-year) to increase the likelihood of capturing synchronic influences and effects of multiple substance use. Given consistent associations between tranquilizer misuse and the use of other substances, we hypothesized that a high polysubstance use class would be the most prevalent in our sample.

The second aim of the study was to examine sociodemographic, clinical, and substance use predictors of identified latent classes. We hypothesized that male gender, younger age, white race, greater psychological distress, more motives for misuse, and use without a prescription would be associated with greater probability of expected membership in a high polysubstance use class. Examining predictors of identified classes might help identify potential risk factors for more severe polysubstance use and subgroups to target for future research. Lastly, we examined functional correlates of identified latent classes, and hypothesized that individuals with expected classification in a high polysubstance use class would display the highest proportions of criminality, suicidal ideation, sexually transmitted infection, and injection drug use. Hypothesized predictors and functional correlates of latent class membership were factors that have been associated with benzodiazepine misuse (Votaw, Geyer, et al., 2019), and were also informed by a previous study that identified patterns and correlates of polysubstance use among a general population sample of individuals with prescription stimulant misuse (Chen et al., 2014).

Method

Data Source and Participants

We extracted data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), which is an annual, population-based survey of U.S. citizens ages 12 and older. Detailed NSDUH methodology has been previously reported (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2017a). We utilized combined data from the 2015, 2016, and 2017 public use data files. Households selected for participation are not eligible for participation the following year. Thus, resampling of participants is unlikely, but participants may be resampled in consecutive years if they move and their new residence is selected. Weighted interview response rates for the 2015-2017 NSDUH ranged from 67 to 70% (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016, 2017b, 2018a). Participants in the present analysis were adult respondents who reported misusing tranquilizer medications in the previous month and had complete data on all predictor variables (N=1,235). Benzodiazepines are the most commonly misused medications in the tranquilizer class (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018b), and 93.7% of individuals included in the present analysis reported benzodiazepine misuse in the previous year. Thus, we chose the present sample to primarily represent those with past-month benzodiazepine misuse.

Measures

Sociodemographics.

We included the following sociodemographic measures in the present analysis: gender (which in NSDUH is subjectively assigned by the interviewer or by participants’ self-identified gender identity, if their gender identity is unclear to the interviewer), age (categorized as 18-25 years old, 26-34, 35+), and racial/ethnic identity (non-Hispanic White vs. racial/ethnic minority).

Substance use.

To determine lifetime prescription tranquilizer (e.g., alprazolam, lorazepam, diazepam, clonazepam, buspirone, hydroxyzine) use, participants were shown cards with pictures and names of these medications and specified which, if any, they had ever used. Participants with lifetime tranquilizer use indicated if they had ever misused these medications, which was defined as use at higher doses/frequency than prescribed, for reasons other than prescribed, or use without a prescription. Those with lifetime tranquilizer misuse then indicated the length of time since their last episode of misuse.

Similar procedures as described above were used to determine past-month prescription opioid, stimulant, and sedative (e.g., zolpidem, eszopiclone, zaleplon, temazepam, triazolam, barbiturates) misuse. Participants were also asked if they had ever used any illicit substances (e.g., cannabis, cocaine/crack cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants) or alcohol. Binge alcohol use (4/5+ drinks for men/women, respectively) was also assessed. Participants with lifetime use of illicit drugs or alcohol answered a standardized set of questions to determine length of time since their most recent use.

Tranquilizer misuse behaviors and motives.

Participants reported their behaviors that comprised tranquilizer misuse. Specifically, participants were asked: “Which of these statements describe your use of tranquilizers at any time in the past 12 months?” Response options included the following: used without my own prescription, used in greater amounts than prescribed, used more often than prescribed, used over longer periods of time than prescribed, and used in some other way that was not directed by a physician. Participants were able to choose more than one misuse behavior. We recoded responses into a dichotomous variable representing any misuse of tranquilizer medications without a prescription in the past year (termed nonmedical use behaviors) or only misusing one’s own prescription for longer periods of time, at higher doses, or for longer periods of time than prescribed (termed medical misuse behaviors).

To determine motives for tranquilizer misuse, participants were asked about the reasons for their most recent use: “Now think about the last time you used tranquilizers in any way a doctor did not direct you to. What were the reasons you used tranquilizers the last time?” Response options included the following: to relax/relieve tension, to experiment/to see what tranquilizers are like, to feel good/get high, to help with sleep, to help with feelings/emotions, to increase/decrease the effect(s) of another drug, because I’m hooked/have to have tranquilizers, and some other reason. Participants could choose more than one reason. We totaled participants’ number of motives at their last episode of misuse, and included this variable in the present analysis. We chose to examine participants’ total number of motives, given prior evidence that more motives for tranquilizer misuse is associated with polysubstance use (Nattala, Leung, Abdallah, Murthy, & Cottler, 2012).

Psychological distress.

The measure of psychological distress utilized in the present analysis was the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6 Scale). This scale was only administered to participants over the age of 18, which limited our analysis to adult respondents. This scale is a general measure of psychological distress that includes six questions about the frequency of mood and anxiety symptoms, such as nervousness, hopelessness, and restlessness. The scale has a potential range of scores from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating greater psychological distress in the previous month. The K6 scale has demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s a=0.89) and construct validity, as evidenced by the ability to differentiate those with and without serious mental illness (Kessler et al., 2003).

Functional correlates.

Functional correlates in the present analysis were behaviors that were hypothesized as potential consequences of benzodiazepine misuse (Votaw, Geyer, et al., 2019). Consistent with previous analyses using NSDUH data (Chen et al., 2014; Hedden et al., 2010), we defined past-year deviant behavior by self-reported endorsement of attacking someone with the intent to seriously hurt them, selling illegal drugs, or attempting to steal anything worth more than $50. We defined past-year arrest status by responses to a question that asked participants how many times they have been arrested and booked in the previous year, not including minor traffic violations. We defined participants self-reported suicidal ideation by a single item indicating if they seriously thought about trying to kill themselves in the previous year. We determined past-year injection drug use by responses to a question that asked participants if they had ever used a needle to inject any drug; those with lifetime injection drug use indicated the amount of time since their last episode of injection drug use. Finally, we defined sexually transmitted infection by self-report of prior formal medical diagnosis.

Statistical Analyses

We utilized latent class analysis (LCA) to identify patterns of polysubstance use in the previous month. Indicators we included in the current analysis were past-month misuse of prescription medications (e.g., opioids, sedatives, stimulants), illicit drugs (e.g., cannabis, cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, etc.), and binge alcohol use. Functional correlates were also included as indicators in the LCA, consistent with the distal outcomes-as-indicator approach (see below). We first estimated the LCA with a 1-class solution and estimated an increasing number of classes until the optimal model was identified. Consistent with best-practice guidelines, both predictors and functional correlates of latent class membership (see below) were included in the measurement models during latent class enumeration (Nylund-Gibson & Choi, 2018; Nylund-Gibson, Grimm, & Masyn, 2019). We determined the optimal number of classes by the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) and sample size adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria (aBIC), with lower values indicating better fitting models, and theoretical interpretability. We did not report the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LRT) as an indicator of model fit because LRT estimates do not account for complex sampling designs, such as those used by the NSDUH (Muthén, 2016). We also reported model entropy, which is a measurement of classification precision.

We included potential predictors of latent class membership as covariates in the LCA, with latent class membership as a categorical outcome variable. Including covariates in the LCA determines if estimated class prevalences vary across the levels of the covariate. Results are interpreted as a multinomial logistic regression and effect sizes reported are adjusted odds ratios (aOR), controlling for all covariates in the model. We chose predictors that have previously demonstrated associations with the incidence and severity of tranquilizer misuse (Votaw, Geyer et al., 2019), including: gender, age (18-25, 26-34, 35+), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white vs. racial/ethnic minority), total number of motives for participants’ last misuse of tranquilizers, misuse behaviors (nonmedical use behaviors vs. medical misuse behaviors), and total K6 score in the previous month. Notably, we chose predictors that were hypothesized to precede or influence benzodiazepine misuse and patterns of polysubstance use in this population, based on temporal precedence (e.g., gender identity likely precedes substance use) and previous findings (Votaw, Geyer, et al., 2019).

Finally, we examined functional correlates of latent class membership, using the distal outcomes-as-indicator approach (Nylund-Gibson et al., 2019). Using this approach, we included functional correlates as indicators in the LCA. Thus, we estimated the proportion of individuals within each latent class who were expected to have reported the distal outcome. We then examined pairwise comparisons of the proportion difference in each of the functional correlates across identified latent classes to determine statistically significant differences. In contrast to predictors of latent class membership, functional correlates examined were behaviors that have been hypothesized to represent consequences of benzodiazepine misuse and, perhaps, might be consequences of polysubstance use among those with benzodiazepine misuse (Votaw, Geyer, et al., 2019). Functional correlates included in the present analysis have previously been associated with benzodiazepine misuse (Votaw, Geyer et al., 2019), and include deviant behavior, arrest, suicidal ideation, injection drug use, and sexually transmitted infection. Given the conceptualization of functional correlates as potential consequences of benzodiazepine misuse, we were interested in evaluating mean differences in functional correlates across identified latent classes. Accordingly, we estimated these functional correlates using the distal outcomes-as-indicator approach, as opposed to including them as covariates (Nylund-Gibson & Choi, 2018).

All analyses were conducted in Mplus version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). We utilized the nesting and weighting variables provided in the public use dataset to account for the complex sampling procedures of the NSDUH (e.g., stratification and clustering, oversampling youth and minorities). Maximum likelihood estimation was used to account for missing data in the indicator variables. Listwise deletion was utilized for missing data on predictor variables, and therefore individuals with missing data on any of the covariate variables were excluded from all analyses. A total of 1,256 participants reported past-month tranquilizer misuse. Data from 21 participants were missing on predictor variables (1.7% of the eligible sample; all did not answer the question regarding misuse behaviors), and therefore 1,235 individuals were included in the LCA.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Individuals with tranquilizer misuse in the previous month with complete data on covariates were included as participants in analyses (N=1,235). Participants most commonly reported binge alcohol use (57.9%), followed by cannabis (51.5%), prescription opioid (33.1%), prescription stimulant (16.0%), cocaine (14.9%), hallucinogen (9.7%), sedative (7.1%), methamphetamine (7.0%), heroin (6.8%), and inhalant (2.0%) use.

Latent Class Analysis

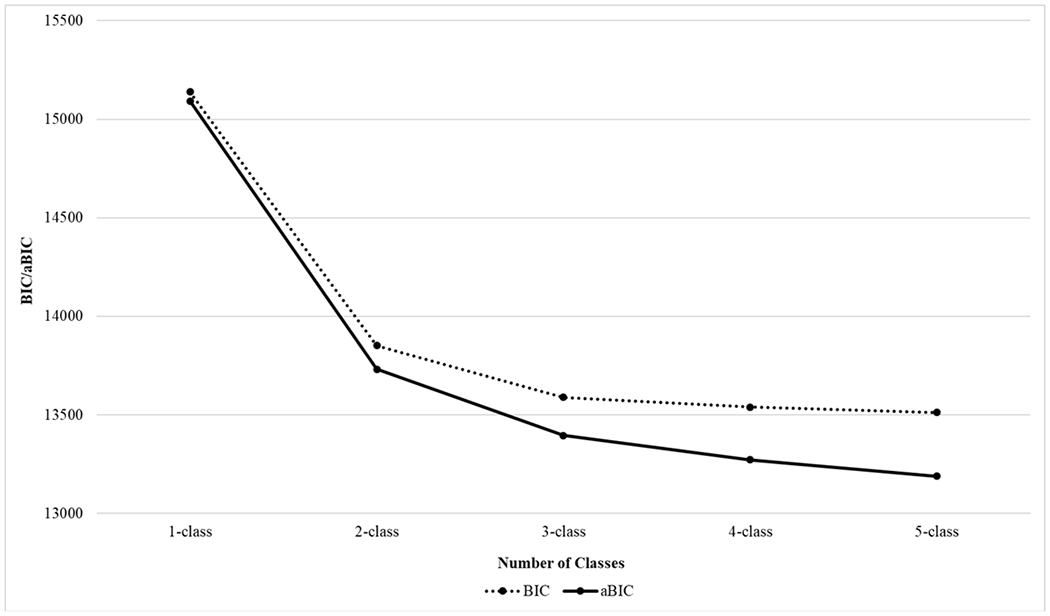

BIC, aBIC, and entropy for the 1- through 5-class latent class analysis solutions are presented in Table 1. BIC and aBIC decreased across all estimated models. In the case that BIC and aBIC continue to decrease across class enumeration, plotting these estimates and identifying the “elbow” of the plot is recommended to aid in identifying the best-fitting model (Nylund-Gibson & Choi, 2018). The slope of decrease in BIC and a BIC was very small following the 3-class model (see Figure 1). Therefore, we selected the 3-class solution as the final model to prevent over-extraction of latent classes (Bauer and Curran, 2004) and to increase parsimony. This model was also selected for greater equality between class prevalences (Nylund-Gibson & Choi, 2018) and theoretical interpretability.

Table 1.

Indicators of model fit for the 1- through 5-class solutions

| BIC | aBIC | Entropy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-class | 15139.406 | 15091.759 | 1.000 |

| 2-class | 13852.566 | 13731.862 | 0.722 |

| 3-class | 13589.281 | 13395.519 | 0.760 |

| 4-class | 13539.363 | 13272.542 | 0.798 |

| 5-class | 13512.782 | 13188.785 | 0.751 |

Note: BIC = Bayesian Information Criteria, a measure of model fit, in which the optimal number of classes is indicated by the lowest BIC; aBIC = Adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria, adds a penalty to the BIC estimate for increasing parameters related to sample size. We did not report the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LRT) as an indicator of model fit given that LRT estimates do not account for complex sampling designs (Muthen, 2016).

Figure 1.

Decreases in BIC and aBIC across the 1- through 5-class models

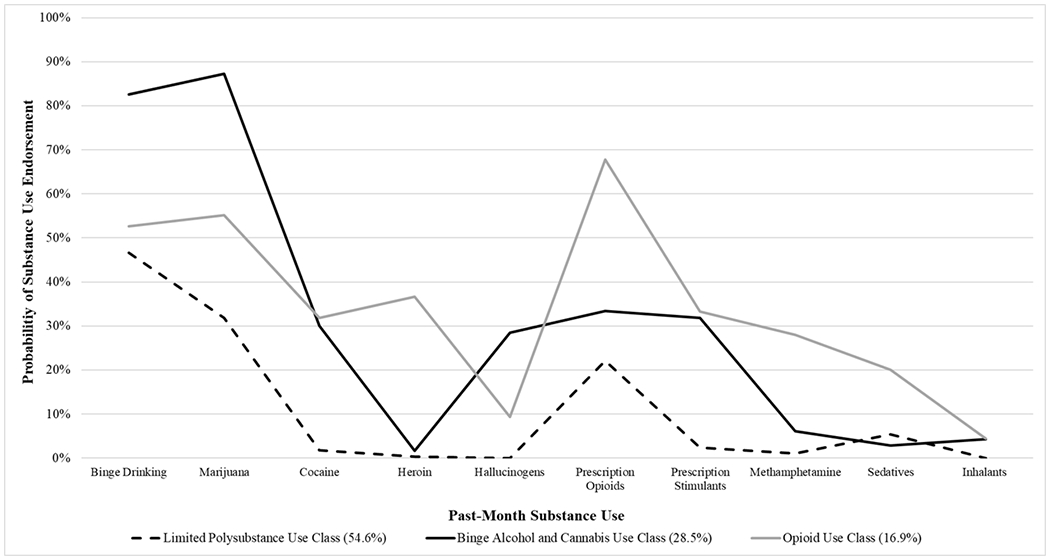

The probabilities of endorsing each substance category, by the three latent class, are presented in Figure 2. All three latent classes demonstrated at least moderate probabilities of binge alcohol, cannabis, and prescription opioid misuse. The first latent class, which we labeled the “limited polysubstance use class,” comprised approximately 54.6% of the sample and demonstrated near near-zero probabilities of other substance use. The second latent class, which we labeled the “binge alcohol and cannabis use class,” consisted of approximately 28.5% of the sample and displayed very high probabilities of binge alcohol and cannabis use. This class also demonstrated moderate probabilities of cocaine, hallucinogen, prescription opioid, and prescription stimulant misuse. The last latent class, which we labeled the “opioid use class,” comprised approximately 16.9% of the sample and displayed a high probability of prescription opioid use. This class also demonstrated moderate probabilities of binge alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, heroin, prescription stimulant, and methamphetamine use. Notably, we titled the binge alcohol and cannabis use class and the opioid use class based on the substance categories with the highest item response probabilities within each class, though both classes demonstrated moderate probabilities of misusing multiple other substances.

Figure 2.

Probabilities of substance use endorsement by expected latent class membership

Multinomial Logistic Regression

Results of the multinomial logistic regression examining predictors of expected membership in the latent classes are presented in Table 2; bolded p-values indicate statistically significant predictors of expected class membership. Male gender was associated with greater odds of expected membership in the binge alcohol and cannabis use class and the opioid use class, as compared to the limited polysubstance use class. Older age was associated with lower odds of membership in the binge alcohol and cannabis use class, as compared to the limited polysubstance use class. Conversely, older age was associated with greater odds of membership in the opioid use class, as compared to the binge alcohol and cannabis use class. Racial/ethnic minority identity was associated with lower odds of membership in the binge alcohol and cannabis use class, as compared to the limited polysubstance use class. More motives for misuse was associated with greater odds of membership in the binge alcohol and cannabis use class and the opioid use class, as compared to the limited polysubstance use class. Greater psychological distress was associated with expected membership in the opioid use class, as compared to both other classes. Lastly, nonmedical use behaviors (vs. medical misuse behaviors) was not significantly associated with class membership.

Table 2.

Multinomial logistic regression examining predictors of expected latent class membership

| Binge Alcohol and Cannabis Use Class vs. Limited Polysubstance Use class (Ref) | Opioid Use Class vs. Limited Polysubstance Use Class (Ref) | Opioid Use Class vs. Binge Alcohol and Cannabis Use Class (Ref) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | aOR (95% CI) | p | aOR (95% CI) | p | aOR (95% CI) | p |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Male | 2.62 (1.54, 4.47) | <0.001 | 2.60 (1.25, 5.43) | 0.011 | 0.99 (0.39, 2.50) | 0.987 |

| Age | ||||||

| 18-25 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| 26-34 | 0.16 (0.09, 0.28) | <0.001 | 1.50 (0.50, 4.46) | 0.471 | 9.58 (3.32, 27.66) | <0.001 |

| 35 and older | 0.02 (0.01, 0.09) | <0.001 | 1.49 (0.46, 4.85) | 0.504 | 65.24 (10.72, 397.12) | <0.001 |

| Race | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Racial/Ethnic Minority | 0.55 (0.31-0.98) | 0.044 | 0.79 (0.38, 1.65) | 0.524 | 1.44 (0.53, 3.87) | 0.475 |

| Nonmedical Use Behaviors | ||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Yes | 1.80 (0.84, 3.85) | 0.131 | 1.36 (0.65, 2.84) | 0.421 | 0.75 (0.27, 2.14) | 0.595 |

| Number of Motives for Misuse | 1.39 (1.12, 1.73) | 0.003 | 1.54 (1.13, 2.11) | 0.006 | 1.11 (0.79, 1.55) | 0.544 |

| Psychological Distress (K6 Score) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.10) | 0.788 | 1.22 (1.11, 1.34) | <0.001 | 1.21 (1.09, 1.34) | <0.001 |

Note: aOR (95% CI) = adjusted odds ratio with 95% confidence interval. Ref = Reference class for each latent class and nominal covariate.

Functional Correlates

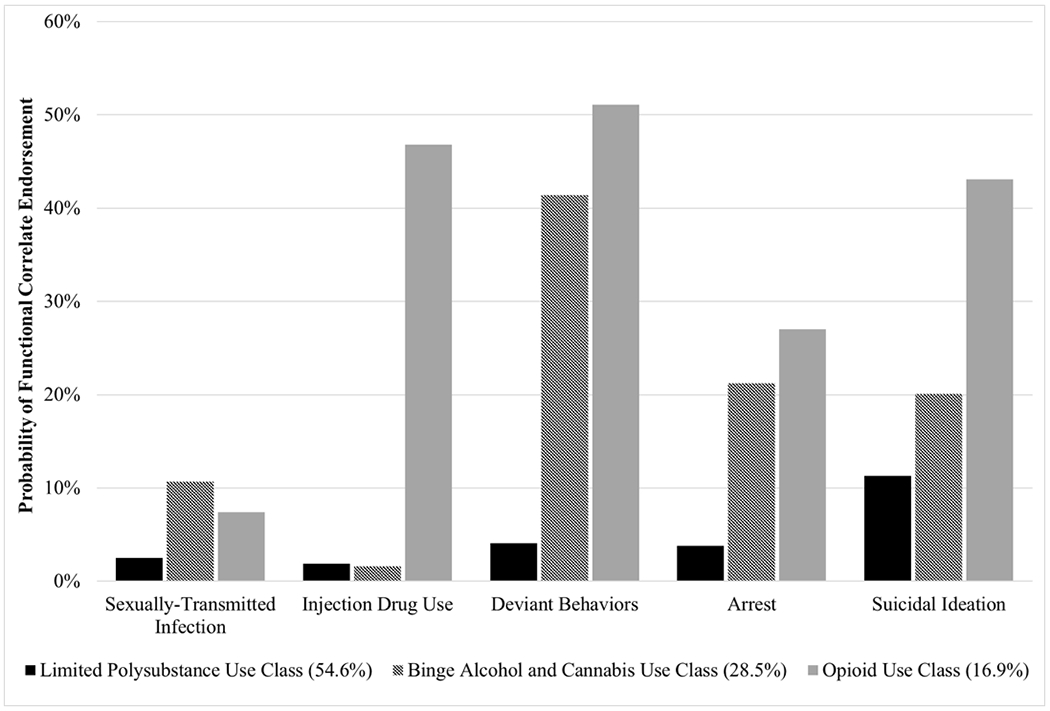

The estimated proportions of each functional correlate by expected latent class membership are presented in Figure 3. Results from the distal outcomes-as-indicator approach indicated the binge alcohol and cannabis use class had a significantly higher rate of sexually transmitted infection, as compared to those in the limited polysubstance use class (Est=0.082 (SE=0.27), p=0.002). There was not a significant difference between the opioid use class and the limited polysubstance use class (Est=0.049 (SE=0.03), p=0.140) or between the opioid use class and the binge alcohol and cannabis use class (Est=0.033 (SE=0.04), p=0.403) on sexually transmitted infection. Those in the opioid use class had a significantly higher rate of injection drug use, as compared to the limited polysubstance use class (Est=−0.452 (SE=0.10), p<0.001), and the binge alcohol and cannabis use class (Est=0.449 (SE=0.10), p<0.001); there was not a significant difference in injection drug use between the limited polysubstance use class and the binge alcohol and cannabis use class (Est=−0.003 (SE=0.02), p=0.840). Both the binge alcohol and cannabis use class and the opioid use class had greater rates of arrest, as compared to the limited polysubstance use class (Est=0.174 (SE=0.04), p<0.001; Est=0.232 (SE=0.06), p<0.001; for the binge alcohol and cannabis use class and the opioid use class, respectively), with no significant different between the binge alcohol and cannabis use class and the opioid use class (Est=−0.057 (SE=0.09), p=0.503). Likewise, the binge alcohol and cannabis use class and the opioid use class had greater rates of deviant behaviors, as compared to the limited polysubstance use class (Est=0.374 (SE=0.06), p<0.001; Est=0.470 (SE=0.08), p<0.001; for the binge alcohol and cannabis use class and the opioid use class, respectively). Lastly, those with expected membership in the opioid use class had a greater rate of endorsing suicidal ideation, as compared to both the limited polysubstance use class (Est=0.318 (SE=0.08), p<0.001) and the binge alcohol and cannabis use class (Est=−0.230 (SE=0.09), p=0.013). The binge alcohol and cannabis use class also had a higher rate of suicidal ideation, as compared to the limited polysubstance use class (Est=0.088 (SE=0.05), p=0.048).

Figure 3.

Past-year functional correlates of expected latent class membership

Note: We identified significant differences between latent classes for each functional correlate. See Results section for details

Discussion

The misuse of benzodiazepine tranquilizers has been documented for over four decades, and overdose related to benzodiazepines is an emerging public health problem in the U.S. (Votaw, Geyer, et al., 2019). Yet, the misuse of benzodiazepines has been largely overlooked by clinicians, the scientific community, and policymakers, particularly in comparison to opioid analgesics (Lembke, Papac, & Humphreys, 2018). The present study aimed to address this gap in the literature by examining patterns of polysubstance use among a U.S. general population sample of adults with tranquilizer misuse. We identified three distinct latent classes: a limited polysubstance use class, a binge alcohol and cannabis use class, and an opioid use class. Nearly half of the sample was classified in either the binge alcohol and cannabis use class (28.5%) or the opioid use class (16.9%), both of which were characterized by moderate to high probabilities of misusing multiple substances (particularly cocaine and prescription stimulants). An unexpected majority of the sample was classified in the limited polysubstance use class (54.6%). However, even those in this class had moderate probabilities of binge alcohol, cannabis, and opioid analgesic misuse. These findings corroborate consistent and robust associations between the use of other substances and risk of tranquilizer misuse (Votaw, Geyer et al., 2019).

Those in the two high polysubstance use classes—the binge alcohol and cannabis use class and the opioid use class—were more likely to experience the assessed functional correlates. These findings indicate that previously identified consequences associated with benzodiazepine misuse (Votaw, Geyer, et al., 2019) might be partly attributable to polysubstance use involvement in this population, as opposed to the effects of benzodiazepines alone. For example, the acute (e.g., greater disinhibition) and prolonged (e.g., greater withdrawal severity, psychological distress) effects of misusing multiple substances might contribute to poorer overall functioning. In the present analysis, the functional correlates and substance use indicators were measured over different time frames (past-year vs. past-month), and therefore it is possible that functional correlates occurred before substance use. Accordingly, individuals experiencing these functional correlates (e.g., criminal involvement, suicidal ideation, etc.) might use multiple substances to cope with negative affective and somatic states. It is also possible that a third factor, such as impulsivity, contributes to both polysubstance use and adverse functioning among those with tranquilizer misuse.

The concurrent use of tranquilizers and opioids was associated with particularly poor psychological functioning. Psychological distress was only associated with membership in the opioid use class, and those in the opioid use class displayed significantly higher rates of suicidal ideation than the other two latent classes. There are numerous potential explanations for these findings. Benzodiazepines and opioids are commonly co-ingested (Votaw, Geyer, et al., 2019), and prior research suggests that one motive for co-ingestion is coping with negative affect (Gelkopf, Bleich, Hayward, Bodner, & Adelson, 1999). Those with greater psychological distress might also have greater availability of both opioids and tranquilizers, as evidenced by the finding that psychiatric disorders are associated with increased risk of benzodiazepine and opioid co-prescribing (Kim, McCarthy, Mark Courtney, Lank, & Lambert, 2017).

Interestingly, the binge alcohol and cannabis use class did not differ from the opioid use class on rates of arrest, deviant behaviors, and sexually transmitted infection. The binge alcohol and cannabis use class also demonstrated probabilities of cocaine and prescription stimulant misuse that were similar to probabilities among the opioid use class. Although a large body of research has characterized benzodiazepine misuse among those with opioid misuse (Votaw, Geyer, et al., 2019), much less is known about those with concurrent use of benzodiazepines with alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, and prescription stimulants. Future research examining the development and maintenance of benzodiazepine misuse in this group is clearly warranted given particularly high rates of sexually transmitted infection, suicidal ideation, arrest, and deviant behavior.

Other identified predictors of class membership might be utilized to inform targeted intervention efforts to reduce the harms of combining tranquilizers with other substances. Male gender, younger age, and white racial/ethnic identity were associated with expected class membership in the binge alcohol and cannabis use class, while only male gender was associated with the opioid use class. These sociodemographic predictors of latent class membership were mostly consistent with our hypotheses, and with previous latent class analyses of substance use patterns among general population samples (Chen et al., 2014; Moss, Goldstein, Chen, & Yi, 2015).

In addition, a greater number of motives for tranquilizer misuse was associated with expected membership in both the binge alcohol and cannabis use class and the opioid use class. Those who use multiple substances might display more substance-specific motives for tranquilizer misuse, such as withdrawal relief, enhancing the effects of opioids, and reducing the effects of stimulants (Gelkopf et al., 1999; Mateu-Gelabert et al., 2017), in addition to more common motives, such as negative affect relief and enhancement (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018b). This is consistent with evidence that individuals with substance use disorders typically display multiple motives for benzodiazepine misuse (Votaw, Geyer et al., 2019). Accordingly, many factors might influence the development and maintenance of a pattern of polysubstance use among those with tranquilizer misuse. Cognitive-behavioral treatments for substance use disorders typically address craving, negative affect, decision-making, and interpersonal functioning (Carroll & Kiluk, 2017), and might be particularly promising for the treatment of polysubstance use among those with tranquilizer misuse.

The present analysis had several methodological limitations. First, data from the present study are cross-sectional, only include non-institutionalized, civilian citizens, and were from retrospective, self-report measures. Therefore, we cannot make causal conclusions about findings from the present analysis, and excluding certain subgroups (e.g., incarcerated individuals, those in substance use disorder treatment) might obscure population estimates of substance use. Findings might also be influenced by recall bias. Previous analyses have not examined the reliability and validity of two variables included in the present analysis—misuse behaviors (i.e., nonmedical use behaviors vs. medical misuse behaviors) and the number of motives for participants’ last episode of misuse. This is an important area of future research as investigators are increasingly using NSDUH data to understand prescription drug misuse. In addition, this study utilized LCA, which is probabilistic and has been criticized for reifying subgroups that do not exist (Raudenbush, 2005). Accordingly, latent classes identified in the present analysis should be interpreted as a heuristic for heterogeneity in polysubstance use among those with tranquilizer misuse. Misclassification of participants in expected latent classes could also cause spurious associations between predictors and expected latent class membership (see Kamata, Kara, Patarapichayatham, & Lan, 2018). Lastly, our findings reflect the concurrent misuse of tranquilizers with other substances, as opposed to simultaneous use (e.g., co-ingestion) (Liu, Williamson, Setlow, Cottler, & Knackstedt, 2018). Future studies are needed to characterize simultaneous substance use among those with tranquilizer misuse.

Overall, nearly half of those with tranquilizer misuse in a U.S. general population sample were classified in one of two polysubstance use profiles—a binge alcohol and cannabis use class and an opioid use class. Functional correlates of these two classes included sexually transmitted infection, arrest, deviant behaviors, suicidal ideation, and injection drug use (for the opioid use class, only). These might also represent subgroups who are at risk of overdose, given that benzodiazepines increase heart rate and respiratory depression when combined with alcohol and/or opioids (Gudin et al., 2013). It is important to note that the limited polysubstance use class had moderate probabilities of binge alcohol, cannabis, and prescription opioid misuse, and therefore this subgroup might also be at heightened risk of overdose. Interventions to reduce polysubstance use and associated consequences among those with tranquilizer misuse should target males, young adults, those with greater psychological distress, and should address multiple motives for misuse. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine temporal relationships between tranquilizer misuse onset, the development of a pattern of multiple substance use, and functional outcomes. Future studies should also examine patterns of polysubstance use in general population samples outside of the U.S., given that benzodiazepine misuse has been widely documented in Europe, Canada, Australia, and Asia, but limited representative population-based data is currently available in countries outside of the U.S. (Votaw, Geyer, et al., 2019).

References

- Artenie AA, Bruneau J, Roy É, Zang G, Lespérance F, Renaud J, … Jutras-Aswad D (2015). Licit and illicit substance use among people who inject drugs and the association with subsequent suicidal attempt. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 110(10), 1636–1643. 10.1111/add.13030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artenie AA, Bruneau J, Zang G, Lespérance F, Renaud J, Tremblay J, & Jutras-Aswad D (2015). Associations of substance use patterns with attempted suicide among persons who inject drugs: can distinct use patterns play a role? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 147, 208–214. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach P, Walton G, Hayashi K, Milloy M-J, Dong H, Kerr T, … Wood E (2016). Benzodiazepine Use and Hepatitis C Seroconversion in a Cohort of Persons Who Inject Drugs. American Journal of Public Health, 106(6), 1067–1072. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Han B, Jones CM, Johnson K, & Compton WM (2018). Prevalence and Correlates of Benzodiazepine Use, Misuse, and Use Disorders Among Adults in the United States. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 79(6). 10.4088/JCP.18m12174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, & Kiluk BD (2017). Cognitive behavioral interventions for alcohol and drug use disorders: Through the stage model and back again. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors : Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 31(8), 847–861. 10.1037/adb0000311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2016). 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Public Use File and Codebook. Retrieved from https://samhda.s3-us-gov-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/field-uploads-protected/studies/NSDUH-2015/NSDUH-2015-datasets/NSDUH-2015-DS0001/NSDUH-2015-DS0001-info/NSDUH-2015-DS0001-info-codebook.pdf

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2017a). 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological Summary and Definitions. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-MethodSummDefsHTML-2015/NSDUH-MethodSummDefsHTML-2015/NSDUH-MethodSummDefs-2015.htm

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2017b). 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Public Use File and Codebook. Retrieved from http://samhda.s3-us-gov-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/field-uploads-protected/studies/NSDUH-2016/NSDUH-2016-datasets/NSDUH-2016-DS0001/NSDUH-2016-DS0001-info/NSDUH-2016-DS0001-info-codebook.pdf

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2018a). 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Public Use File and Codebook. Retrieved from http://samhda.s3-us-gov-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/field-uploads-protected/studies/NSDUH-2017/NSDUH-2017-datasets/NSDUH-2017-DS0001/NSDUH-2017-DS0001-info/NSDUH-2017-DS0001-info-codebook.pdf

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2018b). Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L-Y, Crum RM, Martins SS, Kaufmann CN, Strain EC, & Mojtabai R (2014). Patterns of concurrent substance use among nonmedical ADHD stimulant users: results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 142, 86–90. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comiskey CM, Stapleton R, & Kelly PA (2012). Ongoing cocaine and benzodiazepine use: Effects on acquisitive crime committal rates amongst opiate users in treatment. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 19(5), 406–414. 10.3109/09687637.2012.668977 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connor JP, Gullo MJ, White A, & Kelly AB (2014). Polysubstance use: diagnostic challenges, patterns of use and health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 27(4), 269–275. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Ross J, Mills K, Teesson M, Williamson A, & Havard A (2010). Benzodiazepine use among heroin users: baseline use, current use and clinical outcome. Drug and Alcohol Review, 29(3), 250–255. 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelkopf M, Bleich A, Hayward R, Bodner G, & Adelson M (1999). Characteristics of benzodiazepine abuse in methadone maintenance treatment patients: a 1 year prospective study in an Israeli clinic. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 55(1–2), 63–68. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10402150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudin JA, Mogali S, Jones JD, & Comer SD (2013). Risks, Management, and Monitoring of Combination Opioid, Benzodiazepines, and/or Alcohol Use. Postgraduate Medicine, 125(4), 115–130. 10.3810/pgm.2013.07.2684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden SL, Martins SS, Malcolm RJ, Floyd L, Cavanaugh CE, & Latimer WW (2010). Patterns of illegal drug use among an adult alcohol dependent population: results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 106(2–3), 119–125. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horyniak D, Dietze P, Degenhardt L, Agius P, Higgs P, Bruno R, … Burns L (2016). Age-related differences in patterns of criminal activity among a large sample of polydrug injectors in Australia. Journal of Substance Use, 21(1), 48–56. 10.3109/14659891.2014.950700 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ickowicz S, Hayashi K, Dong H, Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Montaner JSG, & Wood E (2015). Benzodiazepine use as an independent risk factor for HIV infection in a Canadian setting. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 155, 190–194. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamata A, Kara Y, Patarapichayatham C, & Lan P (2018). Evaluation of Analysis Approaches for Latent Class Analysis with Auxiliary Linear Growth Model. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 130 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, … Zaslavsky AM (2003). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(2), 184–189. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, McCarthy DM, Mark Courtney D, Lank PM, & Lambert BL (2017). Benzodiazepine-opioid co-prescribing in a national probability sample of ED encounters. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 35(3), 458–464. 10.1016/J.AJEM.2016.11.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai HMX, Cleary M, Sitharthan T, & Hunt GE (2015). Prevalence of comorbid substance use, anxiety and mood disorders in epidemiological surveys, 1990–2014: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 154, 1–13. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lembke A, Papac J, & Humphreys K (2018). Our Other Prescription Drug Problem. New England Journal of Medicine, 378(8), 693–695. 10.1056/NEJMp1715050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateu-Gelabert P, Jessell L, Goodbody E, Kim D, Gile K, Teubl J, … Guarino H (2017). High enhancer, downer, withdrawal helper: Multifunctional nonmedical benzodiazepine use among young adult opioid users in New York City. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 46, 17–27. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maust DT, Lin LA, & Blow FC (2019). Benzodiazepine Use and Misuse Among Adults in the United States. Psychiatric Services, 70(2), 97–106. 10.1176/appi.ps.201800321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Geyer R, Karakula S, Griffin ML, & Weiss RD (2018). Nonmedical benzodiazepine use in adults with alcohol use disorder: The role of anxiety sensitivity and polysubstance use. The American Journal on Addictions, 27(6), 485–490. 10.1111/ajad.12765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Votaw VR, Bogunovic O, Karakula SL, Griffin ML, & Weiss RD (2017). Anxiety sensitivity and nonmedical benzodiazepine use among adults with opioid use disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses TEH, Lundahl LH, & Greenwald MK (2018). Factors associated with sedative use and misuse among heroin users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 185, 10–16. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.11.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HB, Goldstein RB, Chen CM, & Yi H-Y (2015). Patterns of use of other drugs among those with alcohol dependence: Associations with drinking behavior and psychopathology. Addictive Behaviors, 50, 192–198. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO (2016). Re: LCA and sampling weights [Online discussion group]. Retrieved from http://www.statmodel.com/discussion/messages/13/1202.html?1473360685

- Muthén L, & Muthén B (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed). In Los Angeles: Author; 10.13155/29825 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naji L, Dennis BB, Bawor M, Plater C, Pare G, Worster A, … Samaan Z (2016). A Prospective Study to Investigate Predictors of Relapse among Patients with Opioid Use Disorder Treated with Methadone. Substance Abuse : Research and Treatment, 10, 9–18. 10.4137/SART.S37030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2017). Overdose Death Rates. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates

- Nattala P, Leung KS, Abdallah A. Ben, Murthy P, & Cottler LB (2012). Motives and simultaneous sedative-alcohol use among past 12-month alcohol and nonmedical sedative users. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 38(4), 359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund-Gibson K, & Choi AY (2018). Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 4(4), 440–461. 10.1037/tps0000176 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund-Gibson K, Grimm RP, & Masyn KE (2019). Prediction from Latent Classes: A Demonstration of Different Approaches to Include Distal Outcomes in Mixture Models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 1–19. 10.1080/10705511.2019.1590146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW (2005). How Do We Study “What Happens Next”? The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 602(1), 131–144. 10.1177/0002716205280900 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis TS, Teter CJ, Simoni-Wastila L, & McCabe SE (2018). Prescription tranquilizer/sedative misuse prevalence and correlates across age cohorts in the US. Addictive Behaviors, 87, 24–32. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MD, Anderson BJ, Kenney SR, & Bailey GL (2017). Beliefs about the consequences of using benzodiazepines among persons with opioid use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 77, 67–71. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MD, Kanabar M, Anderson BJ, Lembke A, & Bailey GL (2016). Reasons for Benzodiazepine use Among Persons Seeking Opioid Detoxification. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 68, 57–61. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker D, Hayashi K, Milloy M-J, Nolan S, Dong H, Kerr T, & Wood E (2016). Risk factors associated with benzodiazepine use among people who inject drugs in an urban Canadian setting. Addictive Behaviors, 52, 103–107. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Votaw VR, Geyer R, Rieselbach MM, & McHugh RK (2019). The Epidemiology of Benzodiazepine Misuse: A Systematic Review. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 200, 95–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Votaw VR, Witkiewitz K, Valeri L, Bogunovic O, & McHugh RK (2019). Nonmedical prescription sedative/tranquilizer use in alcohol and opioid use disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 88, 48–55. 10.1016/J.ADDBEH.2018.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]