Abstract

Background

SOVA (Supporting Our Valued Adolescents) is a web-based technology intervention designed to increase depression and anxiety treatment uptake by adolescents in the context of an anonymous peer community with an accompanying website for parents. With a goal of informing the design of a hybrid effectiveness-implementation randomized controlled trial, we conducted a pre-implementation study in two primary care practices to guide implementation strategy development.

Methods

We conducted focus groups with primary care providers (PCPs) at 3 different timepoints with PCPs (14 total) from two community practices. A baseline survey was administered using Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS) and Physician Belief Scale (PBS). Subsequently, during each focus group, PCPs listened to a relevant presentation after which a facilitated discussion was audio recorded and transcribed. After timepoint 1, a codebook based on Consolidated Framework for Intervention Research (CFIR) and qualitative description were used to summarize findings and inform implementation strategies that were then adapted based on PCP feedback from timepoint 2. PCPs were provided with resources to implement SOVA over 5 months and then a third focus group was conducted to gather their feedback.

Results

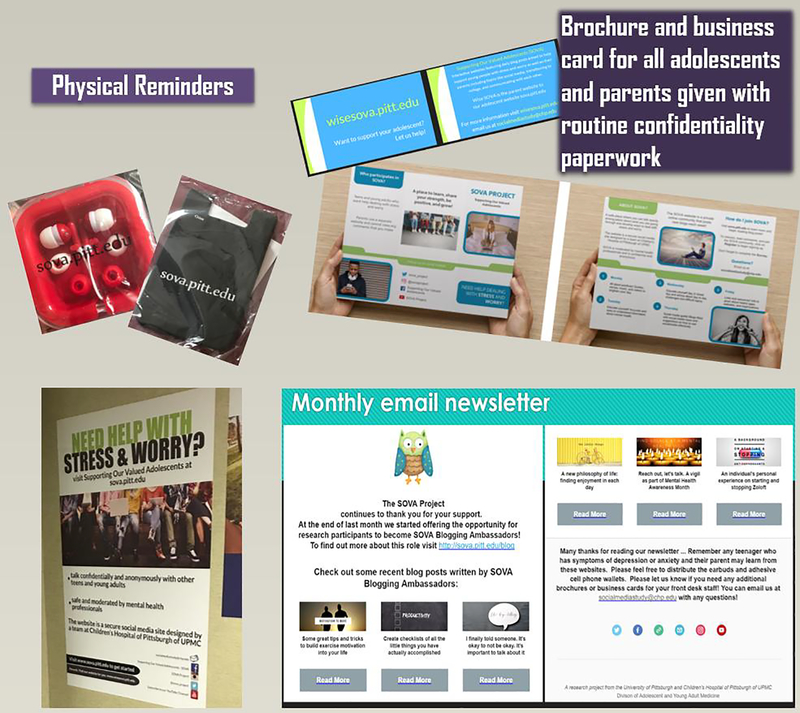

Based on EBPAS and PBS, PCPs are willing to try new evidence-based practices and have positive feelings about taking care of psychosocial problems with some concerns about increased burden. During focus groups, PCPs expressed SOVA has a relative advantage and intuitive appeal, especially due to its potential to overcome stigma and reach adolescents and parents who may not want to talk about mental health concerns with their PCP. PCPs informed various implementation strategies (e.g. advertising to reach a wider audience than the target population; physical patient reminders). During timepoint 3, however, they shared they had a difficult time utilizing these despite their intention. PCPs requested use of champions and others to nudge them and priming of families with advertising, so that the PCP would not be required to initiate recommendation of the intervention, but only offer their strong endorsement when prompted.

Conclusions

The process of conducting a pre-implementation study in primary care settings may assist with piloting potential implementation strategies and understanding barriers to their use.

Trial registration

Keywords: adolescent, depression, anxiety, technology, health services, implementation science, primary health care, pediatrics

Background

Depression in adolescents is associated with substance use, decreased academic and social functioning, and suicidal ideation and behaviors.(1, 2) However, an alarming number of adolescents who experience depression do not receive treatment.(3) In addition to barriers in accessing appropriate mental health treatment, teens may also choose not to see a mental health provider because of stigma, lack of parental support, or lack of education.(4) In an effort to improve identification, treatment, and prognosis of adolescent mental health disorders, major medical organizations encourage primary care settings to intervene more robustly in mental health care.(5, 6)

SOVA (Supporting Our Valued Adolescents) is a technology intervention designed to assist primary care providers with increasing uptake of recommended treatment when they identify a depressed or anxious adolescent. Two moderated social media websites – one for adolescents with symptoms of depression or anxiety and one for their parents – feature daily blogposts meant to educate, address potential negative beliefs such as stigma, and encourage conversation and support between peers (interactions are anonymous). SOVA shows adequate usability and feasibility(7) and the intervention is currently being tested in a pilot randomized controlled trial.(8) SOVA’s design was informed by primary care and mental health provider stakeholders(9). From its inception, the goal was to design a tool that could be briefly recommended by PCPs to adolescents and their parents in the context of a mental health treatment referral, thereby meeting PCPs’ desire to address potential attitudinal barriers to treatment uptake without increasing their overall burden of tasks during the visit.(10, 11)

Better understanding challenges of implementing such a non-routine technology intervention can inform strategies to decrease barriers and increase facilitators to executing an intervention.(12, 13) To plan for a future hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial,(14) we conducted a pre-implementation study in two primary care offices to guide adaptations which may improve SOVA’s uptake in these settings. This process in assessing potential barriers and facilitators within PC was guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). (15) The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research or CFIR is a widely used framework with extensive free and user-friendly online resources.(16) This framework offers an approach for systematically assessing potential barriers and facilitators in preparation for implementing an innovation. It maps well to constructs found to be important in primary care implementation including the following key elements: intervention, professional, organizational, and external context.(17) CFIR has already been used successfully in the primary care setting to implement weight management programs(18), Electronic Health Record (EHR) usage(19), internet patient-provider communication(20), cancer screenings(21), and HPV vaccine use(22). Applying the framework to a technology-based intervention targeted at adolescents with mental health concerns will help to inform the continued efficacy and versatility of CFIR.

PC settings face multiple competing demands on time and effort, and leadership, organizational factors, patient satisfaction, and provider experiences and perceptions influence successful implementation of both technology interventions(23) and mental health interventions(24) within primary care settings. We sought to develop and investigate potential implementation strategies for the introduction of SOVA with the goal of translating to more effective implementation in the future.

Methods

Participants and Sampling

Two pediatric community practices were recruited via purposive sampling to participate in a short survey and a series of separate focus groups. Focus groups were conducted at three different timepoints in 2017–8, with 6 to 8 primary care providers (PCPs) participating in each group, and a practice manager from each practice participating in an interview after the initial focus group. Practices were recruited by Pediatric PittNet, a Clinical and Transformational Science Institute-funded practice-based research network which works collaboratively with University of Pittsburgh researchers and community pediatric primary care practices. Practices in this network routinely screen adolescents for depression and refer as needed, often to embedded therapists available within or at a nearby practice. To understand adolescents’ perspectives on provider feedback about the implementation strategy, an additional focus group was conducted with adolescents and young adults participating in a youth research advisory board (YRAB).(25)

Data Collection

Survey

We first administered a brief survey to develop an understanding of PCPs’ general attitudes and preferences around implementing an evidence based practice addressing psychological concerns. Providers completed the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale(26) (EBPAS) (0–45). The EBPAS(26) was developed with mental health providers providing care to a pediatric sample and measures readiness for making a practice change with regard to four dimensions: appeal of the EBP, likelihood to adopt the EBP if it is required, openness to new EBPs, and the providers’ perceived divergence of the EBP from usual care. Standardized scores range from 0–4. Higher scores on the EBPAS, representing more positive attitudes toward adopting an EBP, have been found in newer providers and providers working in less bureaucratic systems.(26) Providers also completed the modified 14-item Physician Belief Scale (PBS), which includes 2 subscales – belief and feeling (8–40, a higher score indicating more negative attitudes toward addressing psychosocial concerns) and burden (6–30, a higher score indicating more feelings of burden when treating psychosocial concerns) (Cronbach’s alpha of .81 for original scale)(27). The PBS(27) measures beliefs regarding PCPs’ attitudes toward their role and desire (or lack of desire) to treat psychosocial problems.

Focus Groups

All focus groups and interviews were conducted by an adolescent medicine physician researcher from the UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh (AR) experienced in conducting qualitative interviews with adolescents,(28) parents, and PCPs(11) about stakeholder engagement techniques in primary care settings (see SRQR checklist).(9) Focus groups lasted about 45 minutes and were digitally audio recorded and transcribed except the YRAB meeting where only notes were taken. Consent was obtained verbally. Interviewees were asked to refrain from using patient or participant identifiers; if used, these were removed from transcripts along with clinic location to preserve confidentiality and patient privacy. Participant demographic information was not collected to maintain anonymity. Each focus group was preceded by a brief presentation related to SOVA (see topics in Table 1) after which a facilitated discussion was conducted.

Table 1.

PCP Focus Group Format at each Timepoint (T1, T2, T3)

| Time | Focus Group (FG) Content Presented | Focus Group Discussion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Month 1 | T1 | Describe SOVA and potential implementation influences (i.e. intervention source, evidence, design, relative advantage, adaptability) | Perceptions about current practice, need for intervention, potential barriers and facilitators to implementation, acceptability to patients |

| Month 2 | Post-FG Activity: Adaptations to intervention, development of implementation strategies, decisions how to best measure implementation outcomes | ||

| Month 3 | T2 | Propose implementation strategies, tools developed, potential techniques to measure implementation | Feedback on proposed strategies, tools, measurement; how PCPs envision introducing site to families |

| Months 4–8 | Post-FG Activity: PCPs begin implementing intervention, recruit participants fitting engagement study criteria | ||

| Month 9 | T3 | Present results of implementation outcomes and user engagement | Assess fidelity, what actual barriers and facilitators were |

At T1, an initial discussion was held about factors which may influence potential implementation of SOVA. PCPs were presented with ideas for an implementation strategy and provided feedback. Practice managers were interviewed individually and asked for feedback as well as to discuss how they felt the intervention may impact front desk staff. After T1 and prior to T2, a focus group was held with the YRAB group and youth also provided thoughts on an implementation strategy. At T2, PCPs were presented with a summary of survey and qualitative findings from T1 as well as a draft of the implementation strategy. These strategies were then adapted based on PCP feedback from T2 and provided to practices. PCPs and their practice managers were asked to recommend SOVA to their patients using the strategies for 5 months, during which the frequency of SOVA site use was tracked.(7) At the timepoint 3 (T3) focus group, we elicited participants’ feedback on the approaches used in implementing SOVA. An interview script was used for focus groups as well as an accompanying projected presentation (See Appendix). Each participant received a $25 debit card upon completion of each focus group/interview. This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh institutional review board.

Information Collection and Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize results for the survey. Interviews and focus groups were audiotaped, transcribed removing identifiers and filler words (“yeah”), and coded using NVivo software Version 11 (QSR International). Analysis of the T1 focus group was theory driven, applying principles of the CFIR model. For the T1 focus group, a publicly available codebook based on the CFIR model was adapted from Atlas to NVivo (16). CFIR has previously been applied in the pre-implementation phase to identify barriers and facilitators to implementation in health settings.(29) With technology interventions, CFIR has also proven to be a useful framework(30) revealing challenges across settings requiring multiple implementation methods. A research assistant (RA) independently coded the T1 focus group data based on the CFIR codebook(16). AR reviewed the coded data and the RA and AR discussed and resolved discrepancies. The approach of qualitative description as described by Sandelowski was used whereby the coders utilized the available CFIR definitions, summarized the findings while staying very close to the data.(31) A similar approach was used for the T2 and T3 focus groups, except the codebook was developed by AR by initially reviewing the text and then an RA and AR applied it more closely to the data. During T2, triangulation was used for validation and to inquire from PCPs whether they agreed with the findings presented summarizing information collected during T1. A content analysis approach was used to finalize and synthesize themes.

Results

Baseline Survey Results

Out of 14 PCPs present at the first focus group, total average standardized score on EBPAS was 2.43 (SD = 0.94). Participants rated the Appeal (standardized average of 2.64 (SD = 0.40)) and Requirements, (2.43 (SD = 0.56)) as being the most important attributes of an intervention. Openness to evidence-based practices was rated slightly lower at 2.30 (SD = 0.42), although still between a moderate and great extent. Divergence, or rating usefulness of research compared to knowledge from clinical practice was 2.34 (SD = 0.44). Based on EBPAS, PCPs were willing to try new evidence-based practices especially if they make sense, are intuitively appealing, are approved by colleagues, and if they receive enough training. The total average PBS score was 27.5 (SD = 6.36) and average PBS subscale scores were: Belief and Feeling 12.86 (SD = 1.75) and Burden 14.64 (SD = 5.61), indicating positive feelings toward treating psychosocial problems and medium levels of burden when faced with them. These are very similar to how a larger sample from this group of PCPs scored in the past.(10)

Timepoint 1 Focus Group Findings: Pre-implementation strategy

During the initial focus groups, PCPs’ thoughts about SOVA aligned with CFIR constructs (See Appendix, Table 1). PCPs indicated that SOVA has a relative advantage to usual care due to its extensive information, interactivity, lack of advertising or inaccurate information, and a lack of other comparable interventions that address adolescents or parents who are not ready to seek care for depression. As one PCP described,

“in our world we have the patient who wants treatment (and another) who doesn’t want treatment. …the person who doesn’t want treatment, a lot of times we have no idea because they don’t disclose. And it’s almost like the website would be more valuable (than) the PHQ-9: if you’re not ready to talk about this, check out this website. Or whatever it is because they might circle just all zeros and be on their way.”

SOVA had intuitive appeal to PCPs who felt that it has potential to facilitate adolescents and parents in communicating about symptoms and increasing help-seeking:

“The website is a fantastic idea for kids on the fence or parents on the fence or where the kid doesn’t want the parent to know what’s going on with them fully. They’re not harming themselves, they’re not a danger to themselves, they’re not you know having side effects of their depression, but there’s definitely something there and it allows a chance to kind of get them more education. Then they maybe feel more confident about sharing that information with their parent or realizing that they actually need help, and therefore need to disclose to their parent.”

PCPs had recommendations for adaptability about how to introduce the intervention (e.g. mobile app), reduce its complexity (e.g. place website links in electronic health record), and modify the packaging (e.g. business card for parents, general materials in the waiting room).

Relating to outer setting, PCPs identified that SOVA could provide patients with the resources and information to overcome some barriers such as stigma. As one related,

“a lot of families are anti-mental health. It’s because ‘Oh, we don’t believe in that kind of stuff, kids just need to stiffen their upper lip’ or something. So it’s a hard thing to overcome if they’re really deep in those kinds of beliefs, but if you can help them see an opportunity to feeling better...”

PCPs shared many viewpoints on their inner setting and SOVA’s fit. In relation to networks and communication, PCPs shared that providing their patients with in-person recommendations seemed to be more impactful than printed after visit summaries. For themselves, viewing new information was quite difficult as most felt too burdened to frequently check email, although others mentioned actively trying to find new mental health resources (i.e. learning climate). PCPs also felt SOVA was compatible with the practices’ goal to become more adolescent-friendly and did not overlap their current behavioral health initiatives, as one described,”

“It’s a tangible thing to offer and if it’s effective then that’s nice to be able to say ‘Look we have [therapy], but here’s a site you can go to.’ … Parents can look at this also and get information from it and its interactive… (it) would be really nice to be able to not just send them out the door and we’ll get you to therapy … but here’s something that you can start today.”

Both practice managers suggested incorporating providing adolescent and parent SOVA materials within an existing workflow which involved providing information on the importance of confidentiality during the adolescent visit to both adolescents and parents.

During the YRAB meeting, youth agreed with PCP feedback that they would like materials like a poster in the waiting room that they could take a photo of. Contrary to PCPs’ beliefs on adolescents not viewing after visit summaries, adolescents reported that they do sometimes access the summary after the visit as a reminder of what was discussed. Also, although PCPs requested to not have a link on their smartphone to the website as they wanted to role model digital restraint, youth commented that a PCP referring them to a resource on their own smartphone would indicate a stronger endorsement.

Timepoint 2 Focus Group Findings: Implementation strategy design feedback

At T2, PCPs gave detailed feedback about a brochure, business card, and poster design. They made recommendations that the logo should distinguish the website as adolescent-specific as adolescents often feel the pediatric office is more child-focused. PCPs believe that giving SOVA to all adolescents would better capture adolescents not ready to accept treatment for depression or anxiety, as one related, ”

“I like giving it to everyone, cause I feel like sometimes even if kids aren’t ready to talk about (depression), and even though we ask about it and screen for it… they have something to take with them to look over and might help them to be more ready to talk.”

PCP’s also suggested that a website reminder strategy might be more effective than a newsletter. Discussing the newsletter, one remarked ”

“… if it’s just like an email and it doesn’t have an extra thing to click on… I would read.” but later revealed, “Honestly unless it’s like immediately affecting me I tend not to look.” While another, discussing using an EHR strategy, related “we need a specific order for SOVA and if you type in SOVA and it pops up it’s gonna be easy.”

Implementation Strategies

Table 2 describes SOVA implementation strategies revised incorporating on feedback from focus groups at T1 and T2.

Table 2:

Proposed Implementation Strategies

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Advertisement to Reach a Wider Audience | Because (1) Some adolescents may not share depression or anxiety symptoms during the visit and (2) PCPs would not want patients to confuse SOVA as a substitute for treatment, they recommended: • Poster in waiting room • Brochure for all adolescents and a business card for parents to be administered with routine paperwork for all adolescent well-visits • Use lay terms (e.g. “stress” and worry” vs. “depression” and “anxiety”) |

| Design Preferences | Logo artwork must differentiate intervention as an adolescent intervention (e.g. more serious “not cute” logo which would not stand out in pediatric office; pictures of diverse group of adolescents) |

| Ability to Easily Demonstrate Intervention in Visit | In-room computer desktop shortcut to website* PCPs did not want to take smartphones with them in the room but desired to instead ask adolescents to pull up website on their own smartphone |

| Physical Patient Reminders | Prefer to pass out trinkets with website name adolescents might find useful (e.g. cell phone wallet; ear buds) |

| PCP Reminders about Intervention | Prefer monthly emailed newsletter - although many admitted they would not open it unless highly relevant; some commented they would open because of SOVA team engagement with their group and relevance of the intervention; some desired to get feedback on their performance (e.g. patients referred, patients who accessed the website) |

| Electronic Charting* | Prefer an electronic order to the intervention all in one step because this: • Reinforces their recommendation to the intervention • Documents their recommendation • Inserts recommendation into patient’s printed after visit summary, also on the online health portal |

strategies such as including website in after visit summary, desktop shortcut, showing information on TV, and EHR orderset requiring network wide changes beyond participating clinics were not considered

A blueprint and associated implementation materials were created to support SOVA implementation, and PCPs were encouraged to use these for 5 months. These included: a) when receiving standard consent information from the front desk for a well-visit, all adolescents would receive a brochure and their parents would receive a business card about SOVA; b) the waiting room would contain a SOVA poster; c) during the adolescent visit, if appropriate the PCP could recommend SOVA, provide trinket, show the SOVA website on PCP’s smartphone or computer and document in the EHR free text note that they recommend SOVA; also, d) PCPs would receive a monthly newsletter showcasing new SOVA articles and feedback on whether patients used the website.

Timepoint 3 Focus Group Findings: Post-implementation strategy

After the intervention (T3), PCPs shared that they did not complete most implementation steps due to the complexity of patient visits and workflow barriers, despite their intention to do so. PCPs related that visits involving mental health concerns are often more complex due to comorbid somatic complaints and safety concerns. Prioritizing those clinical issues, PCPs commonly would not remember to offer the intervention, despite SOVA’s perceived value. “I have one kid that I think would really like it. And she was here last week. And I just totally forgot because she was having all this other stuff going on, “ shared one PCP. PCPs also found fitting parts of the strategy, such as passing out trinkets, difficult because “you had to kind of come back out (of the exam room) and grab it and take it back in. Even though it is only like 30 seconds, it’s something to hand out.” Similarly, email newsletters were commonly not opened by PCPs with little time to check email, as related by one PCP, “Yeah newsletter sounds not important… Right, bye, I don’t have time.”

In contrast, PCPs felt strategies which did not require action on their part were helpful. PCPs felt the large bright posters in the waiting room and in their clinic space were very helpful reminders and were noticed by patients and parents. “It was a reminder of the existence of the project. Which as we were talking about [was] the hardest part to [accomplish].” Posters were able to reach even those patients who may not speak to their PCP about mental health symptoms

“We [PCPs] are hitting the surface from people that actually present with a problem…especially the somatic kids don’t even realize [they have a mental health problem too] …that’s why I felt like the poster …was really helpful just to have there and maybe to have the [trinkets] in the room because some kids may be curious as they are waiting for us and they are reading about it on their own. “

PCPs felt these subtle messages – posters, brochures, and business cards - had greater reach to patients and parents as PCPs would struggle to remember to talk about the intervention. One PCP remarked the brochure caused a family to bring the websites up with their PCP, “One of the parents of those two kids was actually interested in talking about the website. I think I actually pulled it up on the computer from the brochure.”

PCPs had multiple suggestions on how to revise the implementation strategy moving forward. They recommended to increase targeting to all parents and all adolescents attending the practice (even those outside of well visits) by adding content about the intervention to the practice’s main website. This messaging could also benefit practices, as some PCPs commented that adolescent attendance of well-child visits is low which they attributed to a lack of recognition of the importance of screening for emotional concerns. PCPs preferred receiving a nudge to use the intervention at the appropriate time by a staff member as opposed to an EHR notification due to electronic fatigue, remarking this system currently worked well for them with an embedded research assistant. They also recommended having a PCP champion introduce the intervention to new practices, be available to address PCP concerns, and discuss how PCPs can navigate potential parent concerns.

“Initially a lot of us were a little bit squeamish about a blog format and about people who could comment. You are probably going to have to spend some time calming people’s fears like no there is not going to be any trolls on this site. And getting people’s buy-in to provide us their recommendation you almost have to have a champion for it…You know because we are at least always talking and complaining and somebody might say, ‘Oh, those stupid teenagers’ and then the champion could be like: ‘hey, don’t forget about that SOVA website.’ You know, and then I am like, ‘oh yeah, that might save me some time.’ You know I can just punt it to SOVA.”

Discussion

This pre-implementation study which aimed to enhance recommendation of SOVA, a technology intervention for adolescent depression treatment uptake in primary care, uncovered multiple, unanticipated barriers. First, despite PCPs’ buy-in and intentions to implement such an intervention in a climate that appeared ready, this did not necessarily translate to actual behavior change due to multiple factors discussed below. Instead PCPs requested support from other staff and PCP champions to remind them to recommend the intervention at the appropriate time so they do not miss an opportunity to recommend an intervention they value or feel would be helpful. Second, PCPs informed a generalized and repeated introduction of the intervention to adolescents and parents as opposed to relying only on the PCP’s specific one-time recommendation. Technology interventions, and in particular those addressing sensitive topics such as mental illness, may require this unique implementation approach which incorporates initial priming to the end-user (in our case parents and adolescents) and then multiple opportunities for re-introduction/recommendation of the intervention (by the PCP). When end-users were primed, PCPs, who expressed enthusiasm about the intervention, were more effective at implementation.

Our baseline survey data and initial focus group found that PCPs were amenable to evidence-based changes to their routine practice and that the implementation climate was one in which SOVA may have good potential. PCPs felt a tension to intervene on difficulties engaging patients in mental health treatment and believed SOVA would meet some of their needs, especially for their patient population who may not share symptoms during routine screenings. PCPs recognized that families may experience attitudinal barriers such as being “anti-mental health” which prevent them from seeking mental health treatment (32–34) and that they lacked interventions like SOVA to address these concerns. PCPs also appreciated that SOVA provides education about healthy social media use, as they felt a push to offer interventions which can address negative effects of social media. PCPs felt SOVA has advantages to existing online educational material that they deemed as less trustworthy, especially if it included advertising. PCPs and their practice managers exhibited readiness and a learning climate and helped to refine the implementation approach.

Despite their interest and readiness, PCPs’ intentions for utilizing the implementation strategy they informed did not translate into behavior changes in a real-world scenario. Although PCPs suggested specific strategies they could use to introduce the website (e.g. giving the adolescent trinkets or including information in an after visit summary) they seldomly employed these due to visit complexity when seeing a patient for somatic and mental health concerns, citing workflow barriers. PCPs also reported feeling overwhelmed by emails in general and would miss reminders about the existence of the intervention. Models of behavior change reveal the importance of additional factors in addition to intention in predicting behavior.(35) For example, the theory of planned behavior (36) incorporates both attitudes and social norms.(37) Using a PCP champion – a provider who endorses and increases awareness about the intervention - as suggested during the third focus group, may help change social norms. PCP champions may be identified as those who are innovators or early adopters (38), up-to-date with professional literature, and well-networked.(39, 40) They can prompt a better match between current need for an intervention and it being suggested by a colleague. This process follows providers’ clinical decision-making and technology-uptake patterns as they are influenced by social norms(41), and suggests using “nudging” techniques may better influence provider behavior.(42) In the third focus group post-intervention, quite a few PCPs emphasized the desire for additional support staff such as already embedded research assistants to nudge them, as this process was an already effective one they used for research recruitment.

PCPs informed a different implementation approach than initially anticipated. They requested a more generalized and repeated introduction of SOVA as opposed to a specific PCP recommendation. This is in contrast to referrals for mental health treatment which PCPs would provide only for patients who screen positive. PCPs informed the research team that if only PCPs were offering SOVA to patients being referred to treatment, then the target population - those with negative health beliefs about mental health - may be missed as some adolescents may answer falsely on screens and deny symptoms to the PCP. In addition, PCPs felt the intervention was of value to all adolescents and parents because (a) they could benefit from psychoeducation for depression and anxiety and guidance on social media use and (b) the intervention may meet a practice need by increasing recognition of the PCP’s office as an initial access point for mental health services. One PCP mentioned adolescent non-attendance of well-visits was a concern due to competition of urgent cares conducting sports physicals or immunizations, and wanted to emphasize to families the importance of seeing the PCP annually to assess for emotional health concerns which may be missed in such venues or with fewer than annual appointments. Practice managers provided insight into processes already in place for all adolescents including distribution of information about confidentiality to parents and teens. Generalizing introduction of SOVA to all adolescents and parents then became more feasible as front-desk staff were able to hand out business cards (to parents) and brochures (to adolescents) along with other routine materials. Large posters in the waiting room and clinic space highlighted existence of the intervention to families and aimed to normalize discussing mental health in the PCP practice. Despite PCPs missing opportunities to recommend SOVA, during the time period of implementing the intervention, there was an increase in unique IP addresses visiting both websites, by about 50% in the parent website and 200% in the adolescent website (although for SOVA, this rise was mostly due to a particular article which was shared widely online). We attributed this due to parents viewing the poster in the PCPs’ waiting room. This adaptation of casting a wider net than initially intended seemed to meet the PCPs’ needs and capabilities as well as those of the research team in reaching the target audience.

The approach of introducing the website to a larger audience and at multiple timepoints is also in line with theories of technology acceptance.(43) For example, in Innovation Diffusion Theory, aspects such as visibility – or to what degree a potential user sees another using the tool – and voluntariness of use – the degree to which a potential user feels they would use a tool out of their own free will – can influence innovation adoption. For our study, we found that visibility – through a poster available in the waiting room and information given to every adolescent and parent whether they were depressed, anxious, or seemingly symptom-free, seemed to increase numbers who visited the website, even when PCPs did not routinely recommend the intervention. The presence of these materials may have normalized to teens and parents that other patients may be using the intervention as well. This method of introduction by employing voluntariness – instead of a directed prescription from the PCP – may have also influenced adoption. In addition to these concepts, the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT),(43) proposes that social influence, performance and effort expectancy are also important in technology use. While we studied SOVA’s usability to enhance performance and effort expectancy in a prior study,(7) we have not investigated social influence or the degree to which an individual believes that those who are influential to them, such as their PCP, think they should use the new technology.(43, 44) These theories point to an approach informed by our study which may be useful. Priming all parents and adolescents – despite presence of depression or anxiety - with images and information about the intervention prior to the patient visit at multiple timepoints will allow parents and adolescents to feel SOVA is in widespread use by others, and then perceive that they may voluntarily use it with or without PCP recommendation. Once primed, PCPs may use their social influence within the patient visit to recommend SOVA and further enhance its adoption.

Limitations

Our findings may be less generalizable to settings which are not already interested in improving behavioral health services available within primary care. In spite of this, other clinical interventions can apply our results, especially with regard to the approach of priming a target population with a technology intervention prior to it being introduced by the clinician and the utility of pre-implementation studies with a brief run-in or pilot testing period to distinguish provider behavior from intentions. In addition, we were unable to include all of the suggested implementation strategies such as an electronic health record order, and so we do not know if this would have resulted in improved implementation.

Implications

Even when PCPs find an intervention has value, is needed, and has intuitive appeal, different behavioral and environmental factors can supersede whether or not the PCP actually is able to carry out introducing an intervention in practice. PCPs in our study would readily recommend the intervention when brought up in discussion by the parent or adolescent, but rarely remembered to mention it on their own. They recommended more systemic exposure to the intervention for families so the requirement from the PCP is only to endorse an intervention that the family is already aware of, an approach supported by current technology adoption theories. This study informs the next phase of testing of SOVA, which will be a hybrid cluster randomized controlled trial of its effectiveness while also describing implementation outcomes (hybrid Type II),(14) with the implementation strategy consisting of a systematic way to introduce the intervention to every adolescent and parent in one primary care practice (therefore necessitating a group trial), a PCP champion, as well as frequent “nudges” to providers by support staff (such as embedded research assistants) to remind them of the existence of the intervention. If found to be effective, future iterations may include efforts to reduce the role of support staff to understand what different implementation efforts are needed for sustained adoption.

Conclusions

Behavioral technology interventions for depression or anxiety targeting primary care settings may benefit from offering the intervention to all patients in a non-targeted and de-stigmatized way early in the workflow of patient care (e.g. in the waiting room or prior to the patient visit on an electronic health portal). This may increase intervention reach, imply patient voluntariness of use, and limit PCP burden, only requiring PCPs to endorse an intervention which has already been introduced to the patient. In addition, PCPs desire to be “nudged” about such interventions by PCP champions who change social norms and colloquially, are the trendsetters for newer clinical changes, such as those incorporating technology. Pre-implementation studies or a run-in period with iterative feedback to test implementation strategies prior to a full-scale effectiveness or hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial may be an efficient method to enhance the potential implementation of behavioral technology interventions.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Implementation Materials

Acknowledgments

We thank Cassandra Long for assistance with research recruitment and interview transcription. We thank Sharanya Bandla for technical assistance. We thank the University of Pittsburgh Clinical and Translational Science Institute’s (UL1TR001857) Pediatric PittNet practice-based research network for enhancing our recruitment efforts in their affiliated pediatric offices in the greater Pittsburgh area. We thank and acknowledge the pediatric practices and primary care providers, practice managers, and insurance representatives for informing this study and making it possible.

Funding

Dr. Radovic was supported on an institutional career development award during this study (AHRQ PCOR K12 HS 22989-1) and is currently on a second career development award (NIMH 1K23MH111922-01A1). This research was also supported in part by UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. The project described was also supported by the National Institutes of Health through Grant Number UL1TR001857.

List of abbreviations

- AVS

after visit summary

- CFIR

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- EBP

evidence-based practice

- EBPAS

Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale

- EHR

electronic health record

- FG

focus groups

- IP

Internet Protocol

- PBS

Physician Belief Scale

- PCP

primary care physician

- SOVA

Supporting our Valued Adolescents

- T

Timepoint

- UPMC

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

- UTAUT

Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology

- YRAB

Youth Research Advisory Board

Appendix

Appendix Table 1.

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Constructs based on PCP Feedback

| Construct | Description | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention Characteristics | PCPs perceived a relative advantage of SOVA to usual care due to its extensive information, interactivity, lack of advertising or inaccurate information, and a lack of other comparable interventions that address adolescents or parents who are not ready to seek care for depression. | “I ... just looked at some health resources articles that are being written, but probably not quite to this extent and certainly not interactive.” PCP 1, Site A “Next to it [online article from a popular health website] talks about all sort of other things [advertisements] that nobody wants them to see.” PCP 3, Site A “It seems in our world we have the patient who wants treatment and then the patient who doesn’t want treatment. And like [another PCP] said, the person who doesn’t want treatment, a lot of times we have no idea because they don’t disclose. And it’s almost like the website would be more valuable (than) the PHQ-9: if you’re not ready to talk about this, check out this website. Or whatever it is because they might circle just all zeros and be on their way.” – PCP 1, Site A |

| PCPs had recommendations for adaptability with regard to how the intervention was introduced by them and questioned whether a mobile application could be included in addition to the website. | “I feel like kids would more use app-based or other social media apps they already use, I think if it was more streamlined with that somehow.” PCP 6, Site A | |

| PCPs had multiple recommendations to reduce the complexity of introducing the intervention within clinic including placing links to the website within the electronic health record or practice intranet. | “I think having the website that you can do one click. ‘Here’s what I’m talking about and here’s a card that explains this, but just to show you how easy this is to get into and user-friendly. You may find this really useful. It’s a really cool site.’” – PCP 4, Site B | |

| PCPs also had recommendations for modifying the packaging of the intervention with regard to how they would introduce it during clinic. They recommended a business card instead of a postcard although some thought that might not be as effective, or including a link in the after visit summary. PCPs also recommended general materials for the waiting room. | “Just giving people stuff and not explaining what you’re doing... is probably not as useful [as] if you’re actively interacting with what you’re giving them.” PCP 2, Site B “And then a card to reinforce.” PCP 4, Site B “And a card to reinforce, I think that would be really good.” PCP 5, Site B |

|

| Outer Setting | PCPs recognized that patients and families experience barriers to seeking mental health treatment such as guilt, or not wanting to disclose symptoms to family or PCP, or parental perception that the adolescent is functioning well as opposed to someone who has physical complaints or is missing school. PCPs felt that SOVA may be helpful in addressing some of these barriers. (patient needs and resources) | “in [a specific area] a lot of families are anti-mental health. It’s because ‘Oh, we don’t believe in that kind of stuff, its kids just need to stiffen up their upper lip’ or something. So it’s a hard thing to overcome if they’re really deep in those kinds of beliefs, but if you can help them see the perspective of like an opportunity to feeling better, if you can.” PCP 2, Site B “He [adolescent patient] just had this overwhelming feeling of guilt that he was going to ah ... he didn’t want to bother his parents with his problems. And I told him I guarantee your parents feel worse not being able to do anything that they’re there for you.” PCP 4, Site B “They know the answer if they want help, they know the answer if they don’t want help. Like any survey. So if they’re filling it out all zeros, but in their brain they’re going ‘Yeah, I really do have a problem with this and I do have a problem, but I’m not telling her.’ ... if you don’t want to deal with it and somebody hands you a survey, you know what to fill out. Kids know what to fill out. It doesn’t mean they’re not experiencing the problems. You know cause sometimes they’re sitting with their parents.” PCP 2, Site A “I think it’s more sellable when you’re doing a kid that comes in for an episode because the parents are invested in: ‘Why aren’t you sleeping?’ and ‘I’m really worried about you.’ And you suggest ‘Well you know a lot of people who have sleep problems are depressed and there’s a possibility that it could be nothing physical, but it could be a depression.’ And the parents are like ‘Ohhh yeah I didn’t think about it.’ But if you have a kid in for like a well visit and they’re like playing soccer and getting good grades and eating normally and everything is great, but something comes up that makes you, like something on the PHQ-9 that they weren’t expecting, you say ‘No, I think there’s some worry here about some depression.’ And the parents like ‘Nah, he’s playing soccer, he’s eating good, his sleep and his grades are great. I don’t think so.’ Cause you know what I mean, I think selling it is a little bit easier when the kids actually come in with physical complaints that could be a depression.” PCP 3, Site A |

| Inner Setting | Although PCPs utilize formal communication with patients like the after visit summary, they felt more informal communication (explaining advice verbally) was better utilized by especially adolescent patients. They also mentioned parents using the waiting room TV to get information. PCPs mentioned that they infrequently look at emails sent to them. PCPs and nurse coordinators at one practice reported communicating frequently to track mental health patients’ progress. (networks & communication) | “I’m old fashioned I will just write the [web, URL] address and circle it on the top of their AVS [printed after visit summary]. Because I find anything in the AVS is just buried in there and I don’t think anyone actually reads them.” PCP 2, Site B “I go through [the after visit summary] and say ‘Look this is what it says here, this is what we were talking about,’ star, underline stuff.” PCP 4, Site B “Yeah, put it on the TV screen. I was surprised somebody said something the other day they were like ‘Oh on the TV it said ...’” PCP 4, Site B “I’ll get a message from one of the providers that will say ‘Can you touch base?’ And then you know we’ll create a telephone encounter and then kind of go from there.” Nurse coordinator, Site A |

| PCPs felt a tension for change due to the prevalence of negative media for adolescents who are depressed. (implementation climate) | “the way people use their phone for everything now. There needs to be a resource for them, I mean if there’s websites on how to cut yourself appropriately, there should be countermeasures to that.” PCP 3, Site A “We want them to stop at us [ask PCPs about recommended websites] first and then that way the links that they get are going to be healthykids.org [from American Academy of Pediatrics] or it’s going to be those kind of things rather than just who knows what.” PCP 3, Site A |

|

| PCPs felt the intervention was compatible and didn’t overlap with activities they do already. (implementation climate) | “We don’t overlap because [our practice network] does Twitter, we do Facebook, all of those things.” PCP 2, Site A | |

| Individual PCPs mentioned that they are actively looking for more education on the topic for the office (learning climate, implementation climate). | “I’ve just been looking into more taking care of self, like sleep like those kind of things. I am looking into doing like [further brief counseling training programs] so then I’m able to do some more in the office.” PCP 3, Site A | |

| PCPs were receptive to the intervention and felt it fell in line with their current initiatives. (readiness for implementation) | “Is this something you’d want to co-market with [our practice group] on their website because right now we’re trying to flush out our adolescent health resources... One of the things [our practice group] right now is trying to do is engage with adolescents. And this is exactly what they’re looking for, is something that’s written kind of with that [less medicalized, informal] text because we want to engage them more.” PCP 2, Site A “I certainly think it’s something that we could offer. It’s a tangible thing to offer and if it’s effective then that’s nice to be able to say ‘Look we have [therapy], but here’s a site you can go to’ and parents can look at this also and get information from it and its interactive and I think that would be really nice to be able to not just send them out the door and we’ll get you to therapy ... but here’s something that you can start today.” PCP 4, Site B |

|

| Characteristics of Individuals | PCPs felt they would be able to achieve implementation goals (self-efficacy). | “Can we go on this website and tool around on it? That’s open for us to go to?” [interviewer responds yes] “Okay. That’s how I learn. You were asking about some websites where I’ll search something. I do go on and tool around and think: is this useful or ... could I specifically go in here and say ‘Hey, there’s this really neat article on this that you might find helpful.’” PCP 4, Site B |

| Process | PCPs had multiple ideas for how to engage providers and front desk staff to help market SOVA including: PCPs showing the website to patients during the visit with an easy to click desktop link and then passing out a business card to reinforce the site. PCPs recommended having a poster for the waiting room to engage adolescents and parents while they are waiting. | “I also think something for the waiting room, especially as we’re going to develop something that’s a little more adolescent focused whether it’s a bulletin board or a section to have that up because I think a lot of the parents would love to have you know ‘Are you concerned about your child’s behavior, your adolescent, is this normal?’ Or some catchy wording, I think you’d get a lot of engagement.” PCP 2, Site A |

FOCUS GROUP 1 – Informing Implementation Script

INTRODUCTION

Hello, my name is Ana Radovic and this is my research coordinator, [name]. I am an adolescent medicine physician studying interventions to increase the uptake of depression treatment for adolescents identified in primary care. Thank you so much for participating in this focus group today.

Prior to starting I’d like you to complete two brief surveys about your thoughts about whether an intervention like this is needed and your comfort taking care of adolescents with mental health problems. These are anonymous so please do not write your name. These should take no more than 5 minutes.

Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale

Physician Psychosocial Belief Scale

I will be using an audio recorder and will inform you when I am recording. This is an anonymous interview and we will not be recording your names or any other identifying information. If in the process of the discussion, you would like to describe a patient you’ve seen, in accordance with HIPAA, please refrain from giving me any patient’s name or any other identifying information. Answering questions is voluntary and if there are any questions you do not want to answer, you may choose not to. If there’s anything you would like to add, please do so. This focus group should last no more than sixty minutes, but if we are interrupted, we can continue at a later time.

Are there any questions before we start?

I will begin recording now.

OVERALL WEBSITE DESIGN

A powerpoint presentation to facilitate discussion and key concepts will be displayed. Websites (sova.pitt.edu and wisesova.pitt.edu) will be pulled up on projector and screen.

(intervention source)

Several years ago, I interviewed a group of CCP clinicians about treating adolescent depression. They told me they love having improved access to behavioral health services, but for some families, they’d still run into difficult discussions about treatment with teens and especially with parents. It’d be hard to address if families did not accept a depression diagnosis or had worries or concerns about treatment.

Hand out article I published on PCP beliefs

(design)

The purpose of these two website tools – one for parents (wisesova.pitt.edu) – and one for adolescents (sova.pitt.edu) – is to give PCPs a tool for families at the same time they recommend depression or anxiety treatment.

Each website aims to:

educate about depression diagnosis and treatment

inform about potential negative attitudes about depression

offer access to a community of peers who have experienced depression and benefited from treatment in themselves or in their child

offer positive interactions with therapist moderators.

This website is moderated by behavioral health trainees in psychology and social work 24–7

(evidence)

The design of these websites has been informed by stakeholders including your primary care practice and the behavioral health clinicians who worked with you. We’ve tested the sites and found that adolescents and parents find them highly usable and acceptable. And we have encountered no safety concerns and have successfully moderated all new content.

(relative advantage)

Before we test them to see if they actually result in what we think they do: increase social support, decrease negative health beliefs, and improve parent-adolescent communication, we want to make sure they are adapted in a way that PCPs could actually use them in practice. The advantage of this is instead of testing an intervention that only works in a research setting, we will produce something that is ready to use off the shelf.

Our research group envisions after you recommend treatment, you would offer this website as a supportive intervention providing information and moderated peer support that we hypothesize will help adolescents and parents accept treatment for depression or anxiety.

My first question for you is:

Perceptions about current practice

-

1What is your current practice after recommending depression or anxiety treatment to a patient?…What do you do if someone does not seem interested in treatment? Or raises negative health beliefs such as thinking treatment doesn’t work?

Need for Intervention

-

2

Do you feel an intervention like this is needed? Why?

Potential Barriers and Facilitators to Implementation

-

3How do you envision introducing this intervention to your patients/their parent?…What kinds of things would help you implement this intervention? (possible suggestions: Epic Best Practice Alerts, a modified patient education handout, an EHR smartphrase and integrating with workflow, getting feedback, educational outreach visits, ongoing training, developing a toolkit, business card size with name of website, screensaver on computer screen, having the website on their own phones, adaptations to website itself – keeping track of score)…What kinds of things would stand in the way of implementing this intervention?

Acceptability to Patients

-

4Do you think adolescents and parents would find this intervention acceptable?….if no, what would make it more acceptable?

-

5

Before we end, is there anything else you’d like to share?

I will now turn off the audio device.

Thank you very much for your time. Your WePay card will be filled within 24 hours. Please contact me if there is any difficulty with using it or you have any further questions.

---- After this first Focus Group I will develop a prototype implementation strategy based on PCP feedback ----

FOCUS GROUP 2 – Evaluating Implementation Strategy

Script

I will be using an audio recorder and will inform you when I am recording. This is an anonymous interview and we will not be recording your names or any other identifying information. If in the process of the discussion, you would like to describe a patient you’ve seen, in accordance with HIPAA, please refrain from giving me any patient’s name or any other identifying information. Answering questions is voluntary and if there are any questions you do not want to answer, you may choose not to. If there’s anything you would like to add, please do so. This focus group should last no more than sixty minutes, but if we are interrupted, we can continue at a later time.

Are there any questions before we start?

I will begin recording now.

Based on our last discussion, you informed me that the following adaptations would need to be made to SOVA: (summarize FG1 discussion points).

This helped inform the following implementation strategy: (explain strategy).

My first question for you is:

What do you think of this implementation strategy?

Do you have any remaining concerns about implementation?

What else could be changed to improve it?

Do you still anticipate any potential barriers to introducing the websites to adolescents and their parents?

Before we end, is there anything else you’d like to share?

I will now turn off the audio device.

Thank you very much for your time. Your WePay card will be filled within 24 hours. Please contact me if there is any difficulty with using it or you have any further questions.

---- After this first Focus Group, PCPs will be offered use of the implementation strategy which will most likely take advantage of clinic resources they already have such as patient education handouts, or will involve adapting advertisements about the sites (creating business cards, etc.). They will begin to offer the websites to patients and their parents.----

FOCUS GROUP 3 – Feedback on Implementation Strategy

Script

I will be using an audio recorder and will inform you when I am recording. This is an anonymous interview and we will not be recording your names or any other identifying information. If in the process of the discussion, you would like to describe a patient you’ve seen, in accordance with HIPAA, please refrain from giving me any patient’s name or any other identifying information. Answering questions is voluntary and if there are any questions you do not want to answer, you may choose not to. If there’s anything you would like to add, please do so. This focus group should last no more than sixty minutes, but if we are interrupted, we can continue at a later time.

Are there any questions before we start?

I will begin recording now.

Please tell me your overall impression about offering the SOVA websites.

- During prior focus groups, we discussed using the following implementation strategy (describe). Were you able to use this strategy?… If not at all, why not?… If somewhat, why did you modify it?

What were some challenges of implementing offering the SOVA websites?

What were some things which helped you offer it?

Before we end, is there anything else you’d like to share?

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The original study protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. All individuals provided verbal consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Aalto-Setälä T, Marttunen M, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Poikolainen K, Lönnqvist J. Depressive symptoms in adolescence as predictors of early adulthood depressive disorders and maladjustment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(7):1235–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ. Mental health, educational, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Archives of general psychiatry. 2002;59(3):225–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(NIMH) NIoMH. Treatment of Major Depressive Episode Among Adolescents. 2017.

- 4.Wisdom JP, Clarke GN, Green CA. What teens want: barriers to seeking care for depression. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 2006;33(2):133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuckerbrot RA, Cheung A, Jensen PS, Stein RE, Laraque D, GROUP G-PS. Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care (GLAD-PC): part I. Practice preparation, identification, assessment, and initial management. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20174081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, Laraque D, Stein RE, GROUP G-PS. Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care (GLAD-PC): Part II. Treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20174082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radovic A, Gmelin T, Hua J, Long C, Stein BD, Miller E. Supporting Our Valued Adolescents (SOVA), a Social Media Website for Adolescents with Depression and/or Anxiety: Technological Feasibility, Usability, and Acceptability Study. JMIR Ment Health. 2018;5(1):e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radovic A, Li Y, Landsittel D, Stein BD, Miller E. A Social Media Website (Supporting Our Valued Adolescents) to Support Treatment Uptake for Adolescents With Depression and/or Anxiety and Their Parents: Protocol for a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8(1):e12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radovic A, DeMand AL, Gmelin T, Stein BD, Miller E. SOVA: Design of a Stakeholder Informed Social Media Website for Depressed Adolescents and Their Parents. Journal of Technology in Human Services. 2017:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radovic A, Farris C, Reynolds K, Reis EC, Miller E, Stein BD. Primary care providers’ initial treatment decisions and antidepressant prescribing for adolescent depression. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics: JDBP. 2014;35(1):28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radovic A, Reynolds K, McCauley H, Sucato G, Stein B, Miller E. Parents’ role in adolescent depression care: primary care provider perspectives. The Journal of pediatrics. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stetler CB, Legro MW, Wallace CM, Bowman C, Guihan M, Hagedorn H, et al. The role of formative evaluation in implementation research and the QUERI experience. Journal of general internal medicine. 2006;21(2):S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation science. 2009;4(1):50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical care. 2012;50(3):217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research 2019. [Available from: https://cfirguide.org/.

- 16.Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research [Available from: http://www.cfirguide.org/.

- 17.Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN, Dziedzic K, Treweek S, Eldridge S, et al. Achieving change in primary care--effectiveness of strategies for improving implementation of complex interventions: systematic review of reviews. BMJ open. 2015;5(12):e009993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Damschroder LJ, Lowery JC. Evaluation of a large-scale weight management program using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). Implementation Science. 2013;8(1):51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richardson JE, Abramson EL, Pfoh ER, Kaushal R, Investigators H, editors. Bridging informatics and implementation science: evaluating a framework to assess electronic health record implementations in community settings AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings; 2012: American Medical Informatics Association. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varsi C, Ekstedt M, Gammon D, Ruland CM. Using the consolidated framework for implementation research to identify barriers and facilitators for the implementation of an internet-based patient-provider communication service in five settings: a qualitative study. Journal of medical Internet research. 2015;17(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang S, Kegler MC, Cotter M, Phillips E, Beasley D, Hermstad A, et al. Integrating evidence-based practices for increasing cancer screenings in safety net health systems: a multiple case study using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implementation Science. 2015;11(1):109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garbutt JM, Dodd S, Walling E, Lee AA, Kulka K, Lobb R. Theory-based development of an implementation intervention to increase HPV vaccination in pediatric primary care practices. Implementation Science. 2018;13(1):45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venkatesh V, Zhang X, Sykes TA. “Doctors do too little technology”: A longitudinal field study of an electronic healthcare system implementation. Information Systems Research. 2011;22(3):523–46. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benzer JK, Beehler S, Miller C, Burgess JF, Sullivan JL, Mohr DC, et al. Grounded theory of barriers and facilitators to mandated implementation of mental health care in the primary care setting. Depression research treatment. 2012;2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navratil J, McCauley HL, Marmol M, Barone J, Miller E. Involving Youth Voices in Research Protocol Reviews. The American journal of bioethics: AJOB. 2015;15(11):33–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aarons GA. Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Ment Health Serv Res. 2004;6(2):61–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLennan JD, Jansen-McWilliams L, Comer DM, Gardner WP, Kelleher KJ. The Physician Belief Scale and psychosocial problems in children: a report from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings and the Ambulatory Sentinel Practice Network. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics: JDBP. 1999;20(1):24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radovic A, Gmelin T, Stein BD, Miller E. Depressed adolescents’ positive and negative use of social media. J Adolesc. 2017;55:5–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cole AM, Esplin A, Baldwin L-M. Adaptation of an Evidence-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening Program Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Preventing chronic disease. 2015;12:E213–E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramsey A, Lord S, Torrey J, Marsch L, Lardiere M. Paving the way to successful implementation: identifying key barriers to use of technology-based therapeutic tools for behavioral health care. The journal of behavioral health services research. 2016;43(1):54–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandelowski M Focus on Research Methods: Whatever Happened to Qualitative Description?. Research in Nursing & Health 2000;23:334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC psychiatry. 2010;10:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanielian T, Jaycox LH, Paddock SM, Chandra A, Meredith LS, Burnam MA. Improving treatment seeking among adolescents with depression: understanding readiness for treatment. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(5):490–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meredith LS, Stein BD, Paddock SM, Jaycox LH, Quinn VP, Chandra A, et al. Perceived barriers to treatment for adolescent depression. Med Care. 2009;47(6):677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eccles MP, Hrisos S, Francis J, Kaner EF, Dickinson HO, Beyer F, et al. Do self-reported intentions predict clinicians’ behaviour: a systematic review. 2006;1(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Godin G, Kok G. The theory of planned behavior: a review of its applications to health-related behaviors. American journal of health promotion. 1996;11(2):87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Millstein SG. Utility of the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior for predicting physician behavior: a prospective analysis. Health Psychology. 1996;15(5):398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations: Simon and Schuster; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in health care. JAMA. 2003;289(15):1969–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grol R Successes and failures in the implementation of evidence-based guidelines for clinical practice. Medical care. 2001;39(8):II-46–II-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holden RJ. Social and personal normative influences on healthcare professionals to use information technology: towards a more robust social ergonomics. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science. 2012;13(5):546–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hesse BW, Ahern DK, Woods SS. Nudging best practice: the HITECH act and behavioral medicine. Translational behavioral medicine. 2011;1(1):175–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS quarterly. 2003:425–78. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lai P The literature review of technology adoption models and theories for the novelty technology. JISTEM-Journal of Information Systems Technology Management. 2017;14(1):21–38. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.