Abstract

Streptococcus suis is a zoonotic pathogen suspected to be a reservoir of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes. The genomes of 214 strains of 27 serotypes were screened for AMR genes and chromosomal Mobile Genetic Elements (MGEs), in particular Integrative Conjugative Elements (ICEs) and Integrative Mobilizable Elements (IMEs). The functionality of two ICEs that host IMEs carrying AMR genes was investigated by excision tests and conjugation experiments. In silico search revealed 416 ICE-related and 457 IME-related elements. These MGEs exhibit an impressive diversity and plasticity with tandem accretions, integration of ICEs or IMEs inside ICEs and recombination between the elements. All of the detected 393 AMR genes are carried by MGEs. As previously described, ICEs are major vehicles of AMR genes in S. suis. Tn5252-related ICEs also appear to carry bacteriocin clusters. Furthermore, whereas the association of IME-AMR genes has never been described in S. suis, we found that most AMR genes are actually carried by IMEs. The autonomous transfer of an ICE to another bacterial species (Streptococcus thermophilus)—leading to the cis-mobilization of an IME carrying tet(O)—was obtained. These results show that besides ICEs, IMEs likely play a major role in the dissemination of AMR genes in S. suis.

Keywords: Streptococcus suis, integrative conjugative elements, integrative mobilizable elements, chromosomal excision, conjugative transfer, antimicrobial resistance, bacteriocin synthesis cluster

1. Introduction

Streptococcus suis—a normal inhabitant of the upper respiratory tract of pigs—is an important cause of post-weaning infections in pigs and a zoonotic agent afflicting people in close contact with infected pigs or eating insufficiently cooked pork meat [1,2]. It is also a major agent of human meningitis in Asia [2]. In Western countries, cases are less frequent but can be severe and even fatal [3,4,5]. The most prevalent serotype causing human infection is serotype 2, although virulence differs among MultiLocus-Sequence-Typing (MLST) groups [2,5]. Serotype 14 strains are also frequently associated with human infections [2,5]. Moreover, a case of human infection due to serotype 9, which is increasingly reported in pig invasive disease worldwide, was reported in Thailand [6].

In the context of the rising threat of antimicrobial resistance [7,8] requiring a One Health approach, S. suis is receiving growing attention due to its extended drug resistance [9]. Numerous resistance determinants (in particular tetracycline, macrolide, aminoglycoside, and chloramphenicol resistance genes) have been described in this bacterial species, many of them being carried by Integrative Conjugative Elements (ICEs) [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. ICEs are mobile genetic elements that excise from the chromosome and transfer autonomously by conjugation [17]. After cleavage at a site called oriT, DNA is addressed to a type IV secretion system by a relaxase, thanks to its interactions with a coupling protein [18]. The main families of ICEs carrying antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes described in S. suis are Tn916, Tn5252, and Tn1549 families [11,12,13,14,15,19,20]. Mosaic or composite elements resulting from tandem accretions of ICEs or internal insertions of ICEs within another ICE were reported [11,12,13,14,15,19,20]. Other extremely abundant but poorly documented Mobile Genetic Elements (MGEs) are Integrative and Mobilizable Elements (IMEs). IMEs were originally defined as excisable MGEs carrying their own oriT and encoding one or two mobilization proteins [21]. They can subvert the conjugation apparatus of unrelated conjugative elements to promote their own transfer [17,22,23]. According to their current definition, IMEs are not defective ICEs, i.e., elements deriving from these elements by deletion of parts of their conjugation modules. Furthermore, all known IMEs are unrelated or distantly related to ICEs [23]. So far, only one study examined the IME content of S. suis genomes (in 17 complete genomes), but cargo genes of these MGEs were not reported [22].

In this work, we made a comprehensive in silico search and analysis of ICEs and IMEs and extensive identification of AMR genes present in 214 S. suis draft genomes. We then analyzed whether these AMR genes are carried by MGEs and whether other genes of interest (bacteriocin synthesis clusters in particular) are found in MGEs. The ability to transfer of two ICEs that host IMEs carrying AMR genes was also investigated. A huge amount of ICEs and IMEs and derived elements were detected at various chromosomal sites (416 ICE-related and 457-IME-related elements). High diversity was observed in recombination but also in conjugation/mobilization modules. Besides ICEs, IMEs appear to be major vehicles of AMR genes. An IME carrying tet(O) was transferred from S. suis to Streptococcus thermophilus by cis-mobilization mediated by a Tn5252-related ICE.

2. Results

2.1. Prevalence and Diversity of ICEs and IMEs in S. suis Strains Belonging to Various Serotypes

Analysis of 214 genomes of S. suis strains belonging to 27 different serotypes revealed 232 ICEs with a full sequence, 49 ICEs with a partial sequence (due to sequencings gap(s) in the de novo assembled genome) and 135 elements deriving from ICEs (with truncated recombination and/or conjugation genes, called dICEs). IME-related elements appeared more prevalent than ICEs since 406 IMEs and 51 elements deriving from IMEs (with truncated integrase or relaxase gene, called dIMEs) were detected.

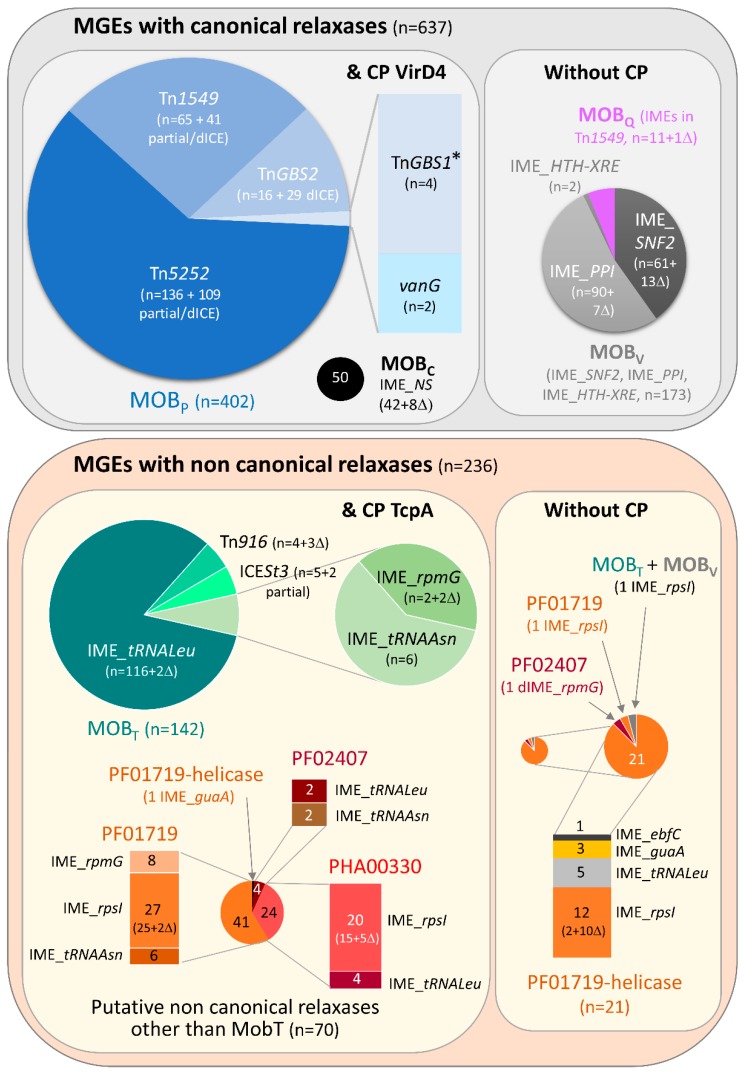

Most of the ICE-related elements found in S. suis genomes encoded a canonical relaxase of the MOBP family (n = 402) associated with a coupling protein of the VirD4 family. By contrast, more diversity was observed for IMEs with canonical relaxases of the MOBC, MOBV or MOBQ families or putative non-canonical relaxases with various domains found in RCR initiators (PF02486 or MOBT, PF01719 associated or not with a helicase domain, PF02407, PHA00330 or MOBT + MOBV). These relaxases were associated or not with a coupling protein (of the TcpA family except for those harboring a MOBC relaxase that is associated with a VirD4 CP) (Figure 1 and Table S1).

Figure 1.

Description of the whole set of Integrative Conjugative Elements (ICEs), Integrative Mobilizable Elements (IMEs) and derived elements found in the 214 S. suis genomes analyzed. Elements were grouped according to the nature of their relaxase and the presence or absence of an associated coupling protein. * TnGBS1 is indicated in the elements with a MobP relaxase but it should be pointed out that its relaxase is only distantly related to MobP relaxases and does not possess the characteristic PF03432 domain of this family [23]. The sizes of the circles are at scale, except when zooming to provide further details. The integration sites of the IMEs are indicated in the element names themselves.

Only one strain devoid of ICE and IME was identified. This strain did not possess any acquired resistance gene (Table S1).

2.1.1. ICEs and Elements Deriving from ICEs

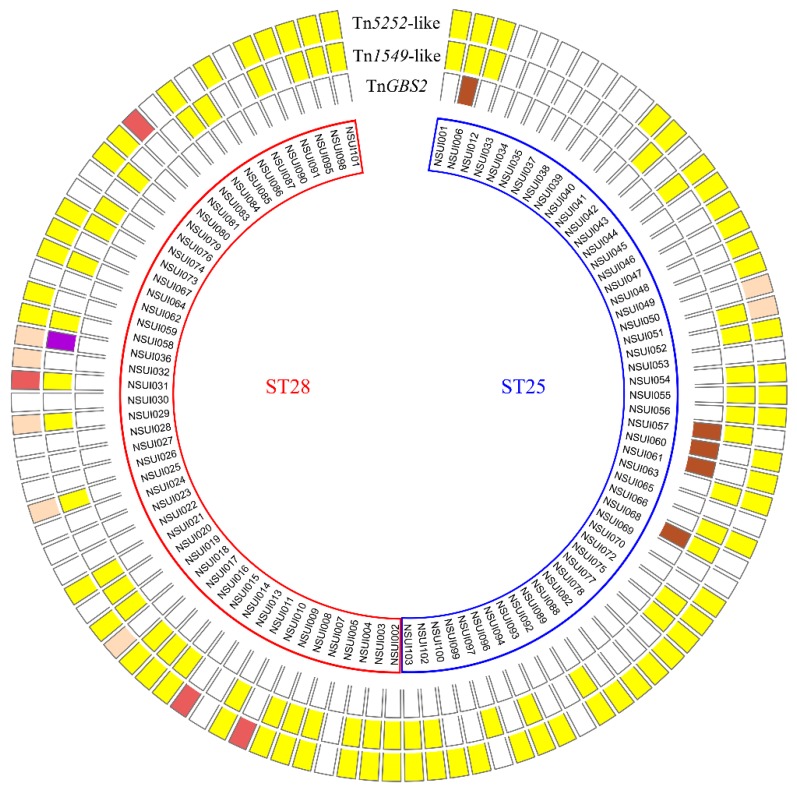

In strains of serotype 2 (belonging either to MLST groups ST25 or ST28), three families of ICEs (defined according to their conjugative module, i.e., >40% of identity for relaxase, CP and VirB4 protein [10]) were detected (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Integrative and conjugative elements detected in the genomes of S. suis strains belonging to serotype 2. Strains belonging to LultiLocus-Sequence-Typing (MLST) groups ST25 (n = 51, with a blue frame) and ST28 (n = 51, with a red frame) appear separately. Only ICEs with a full sequence are shown in the figure. Boxes located in front of a strain name are either empty (absence of ICE) or colored (presence of an ICE). Boxes in the outer circle, middle circle, and inner circle, correspond to ICEs belonging to Tn5252, Tn154,9 and TnGBS2 families, respectively. The color of the box indicates the integration site of the element: yellow for integration into the 3′ end of rplL, salmon for integration into rumA, dark red for integration into mutT, purple for integration into the 5′ end of rbgA, dark brown for the lower specificity of TnGBS2.

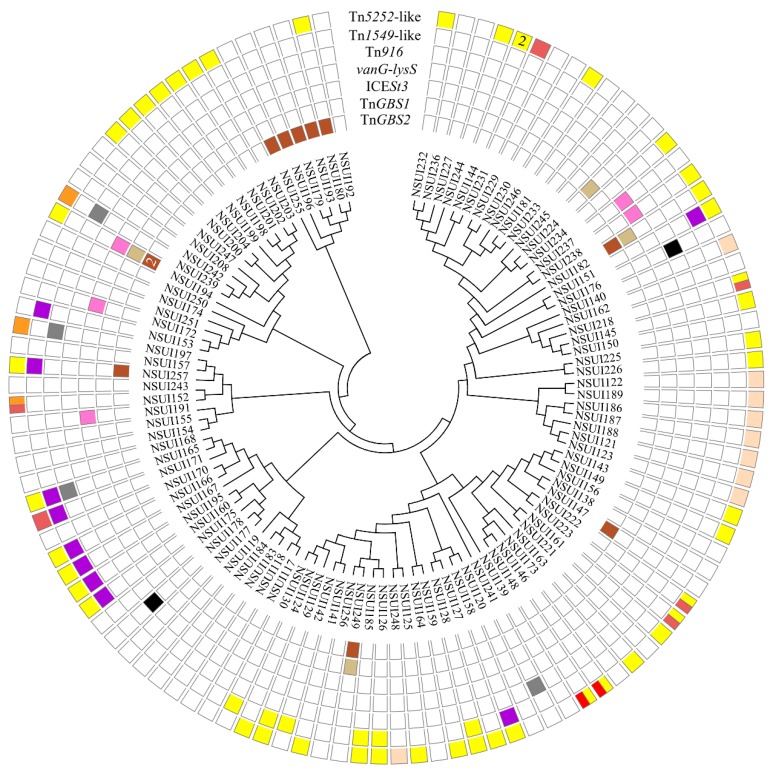

In the other serotypes examined, seven families of ICEs were detected: Tn5252, Tn1549, and TnGBS2 families and four additional ones: Tn916, vanG, ICESt3, and TnGBS1 families (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Integrative and conjugative elements detected in the genomes of S. suis strains belonging to other serotypes than serotype 2. Strains were grouped according to their MLST alleles. The cladogram was generated by maximum likelihood method on concatenated sequences of the aroA, cpn60, dpr, gki, mutS, recA, and thrA genes. Each family of ICEs is indicated on a specific circle. The color of the box indicates the integration site of the element. For elements of the Tn5252 family (first outer circle): yellow is used for integration into rplL, salmon for integration inside rumA, dark red for integration inside mutT, red for integration in the ADP ribose pyrophosphatase gene and orange for integration in the luciferase monooxygenase gene. For elements of the Tn1549 family (second outer circle), yellow is used for integration into the 3′ end of rplL and purple for integration into the 5′ end of rbgA. On the third outside circle, elements of the Tn916 family are indicated in dark grey. Elements of the vanG family integrated into the 3′ end of lysS are indicated in black on the 4th circle (middle circle) and elements of the ICESt3 family integrated into the 3′ end of tRNALys on the 5th circle (pink color). Elements of the TnGBS1 and TnGBS2 families are indicated on the 6th and 7th inner circles respectively (light and dark brown colors). When several elements of the same family are integrated in different sites in the same strain, the corresponding box is bicolor (for example 2 elements of Tn5252 family in NSUI218, one integrated into rplL and one integrated inside mutT) whereas if they are inserted in the same site the number of elements is indicated (for example 2 elements of Tn5252 family in NSUI144 both integrated into the rplL gene).

In total, considering all the genomes studied, Tn5252-related ICEs were the most prevalent ones (n = 136 ICEs with full sequence). They were found integrated either into the 3′ end of rplL (gene encoding the ribosomal protein L7/L12), inside rumA (gene encoding an RNA methyltransferase), inside mutT (gene encoding a NTP pyrophosphohydrolase), inside a gene encoding a luciferase-like monooxygenase or inside a gene encoding an ADP ribose pyrophosphatase (Figure 2). Partial ICEs or elements deriving from ICEs by deletion were also detected at the 5′ end of rbgA (gene encoding a ribosomal biogenesis GTPase) (Table S1).

Most of the Tn1549-related elements (49 out of 65 elements found in total) were integrated in tandem with a Tn5252-related element (into rplL). We also found that two ICEs (or elements deriving from ICEs) of the same family (Tn5252 or Tn1549 families) can co-exist in the same strain.

All the detected 16 TnGBS2-related ICEs were integrated into intergenic regions. None were found in the rplL integration site.

The four ICEs of the Tn916 family detected in this work include two Tn916 (with one integrated into an ICE of the Tn5252 family) and two ICEs with a conjugation module distantly related to Tn916 (integrated inside a tRNAArg gene).

ICEs of the ICESt3, TnGBS1, and vanG families were found in 5, 4, and 2 genomes, respectively.

2.1.2. IMEs and Elements Deriving from IMEs

IMEs were detected in a large panel of chromosomal integration sites (13 different integration specificities as reported in Table S1). Half of these integrations (n = 6) relied on tyrosine integrases that mostly target genes encoding tRNAs (tRNALeu or tRNAAsn) or ribosomal proteins (mostly in rpsI, several in rpmG but none in rplL). Five cases of IME-IME accretions were detected (in tRNALeu and rpsI sites). The second half of integrations (n = 7) was mediated by serine recombinases. Interestingly, some of them target conserved genes located on ICEs including two genes of the Tn5252 family: the SNF2 gene encoding a putative adenine-specific DNA methylase with a COG4646 domain and a helicase domain (n = 61) and a gene encoding a putative peptidylprolyl isomerase (PPI) (n = 90).

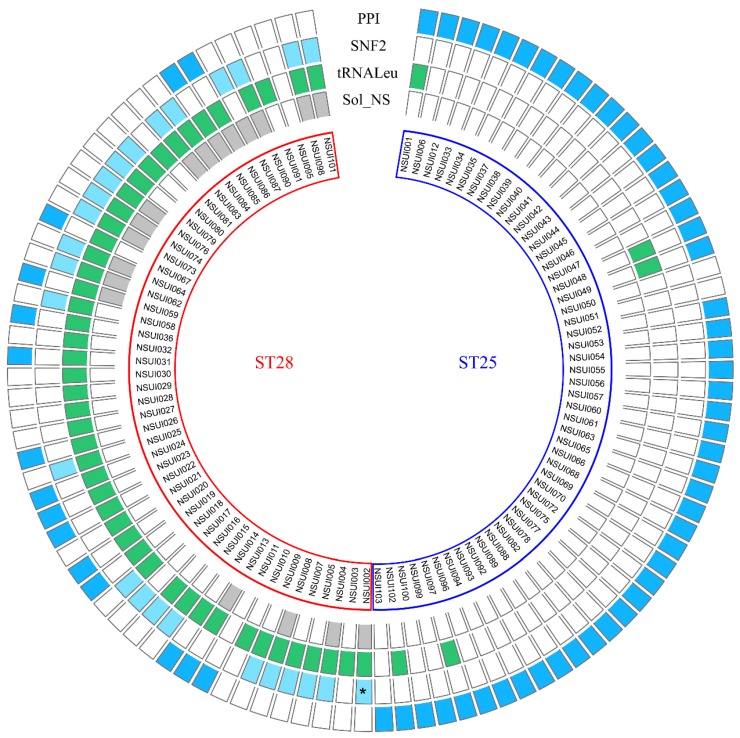

For strains of serotype 2, four different integration specificities were detected (Figure 4). All strains belonging to MLST group ST25 (except two) carry an IME integrated inside the PPI gene whereas most of the ST28 strains carry an IME integrated inside the SNF2 gene. ST28 strains also frequently harbor IMEs integrated into a tRNALeu gene or IMEs with a low specificity of integration.

Figure 4.

Integrative and mobilizable elements detected in the genomes of S. suis strains of serotype 2. Boxes located on the same line as a strain name are either empty (absence of IME) or colored (presence of an IME). Strains belonging to MLST groups ST25 (n = 51) and ST28 (n = 51) are grouped in the figure (blue and red frames, respectively). From the outer to the inner: IMEs integrated in the peptidylprolyl isomerase gene (in dark blue on the first outside circle); IMEs integrated into SNF2 gene (in light blue on the second circle); IMEs integrated into a tRNALeu gene (in green on the third circle); IMEs integrated into intergenic regions (in light grey on the inner circle). One element resulting from recombination between an IME_SNF2 and an IME_PPI (called “hybrid” in Table S1) is indicated by a star.

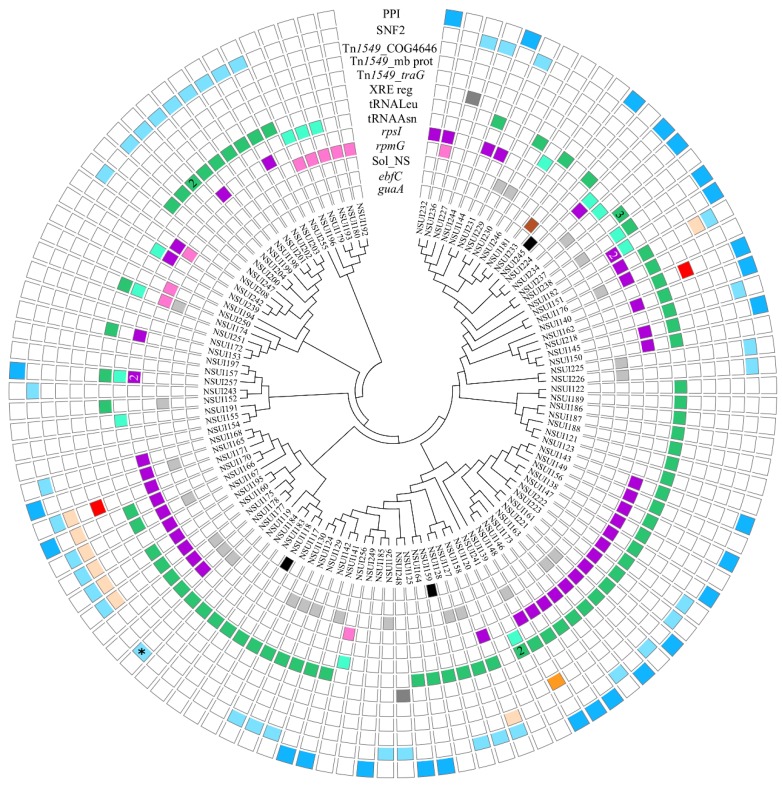

In the other serotypes examined, a large diversity of IMEs was detected. In addition to the four integration specificities already detected in strains of serotype 2, nine additional ones were found (Figure 5). IMEs that target the SNF2 and PPI genes were detected in ICEs integrated into either rplL, inside rumA or inside mutT. IMEs integrated inside genes of Tn1549-related ICEs were also detected: (i) inside a gene that encodes a protein distantly related to SNF2 of Tn5252 (indicated as Tn1549_COG4646); (ii) inside a gene encoding a membrane protein (Tn1549_mb prot), and (iii) inside a gene encoding the coupling protein of the ICE (Tn1549_traG). IMEs encoding a serine integrase were also detected inside a gene encoding an HTH_XRE regulator and at various intergenic sites for elements encoding related serine integrases (Table S1, Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Integrative and mobilizable elements detected in the genomes of S. suis strains of serotypes other than 2. Boxes located on the same line as a strain name are either empty (absence of IME) or colored (presence of an IME). Strains were grouped according to their MLST alleles (see material and method section for the method used to generate the cladogram that appears in the middle of the figure). The first two outer circles indicate IMEs integrated into the peptidylprolyl isomerase gene (in dark blue) and IMEs integrated into the SNF2 gene (in light blue) (IMEs integrated into ICEs belonging to the Tn5252 family). The third, 4th and 5th circles show IMEs integrated into ICEs of the Tn1549 family (from outside to inside: in a gene encoding a protein with a COG4646 domain shown with a salmon color, a membrane protein shown in orange and in traG shown in red). The next circle indicates the presence of IMEs integrated into an XRE regulator gene (dark grey color). Middle circles show IMEs integrated into the 3′ end of tRNA genes; in green for integration into tRNALeu gene (7th circle) and in light green for tRNAAsn gene (8th circle). On the following circles (still from outside to inside): IMEs integrated into rpsI (in purple on the 9th circle) and into rpmG (in pink on the 10th circle). Inner circles indicate IMEs with a low specificity of integration (in light grey on the 11th circle), in ebfC gene (in dark brown on the 12th circle) and in guaA (in black on the 13th last inner circle). One element resulting from recombination between an IME_SNF2 and an IME_PPI (called “hybrid” in Table S1) is indicated by a star. When several elements are present at the same integration site, the number of elements is indicated in the box (for example, 3 IME_tRNALeu in strain NSUI237).

It is difficult to define families for IMEs since a relaxase of a given family (defined according to phylogenetic analysis and 40% sequence identity clustering [22]) can be associated with different families of coupling proteins (for example, relaxase with a PF02486_6 domain can be associated with two different CPs in S. suis IMEs, Figure S1). In the same way, a coupling protein of a given family (for example, a TcpA_12 coupling protein) can be associated with different families of relaxases (2 different relaxases for the example of TcpA_12, Figure S1). In total, twenty-two different combinations of integrase-relaxase-(coupling protein) were observed for IMEs (Figure S1). The highest diversity was observed for IMEs integrated into rpsI and into a tRNALeu gene (Table S1, Figure 6).

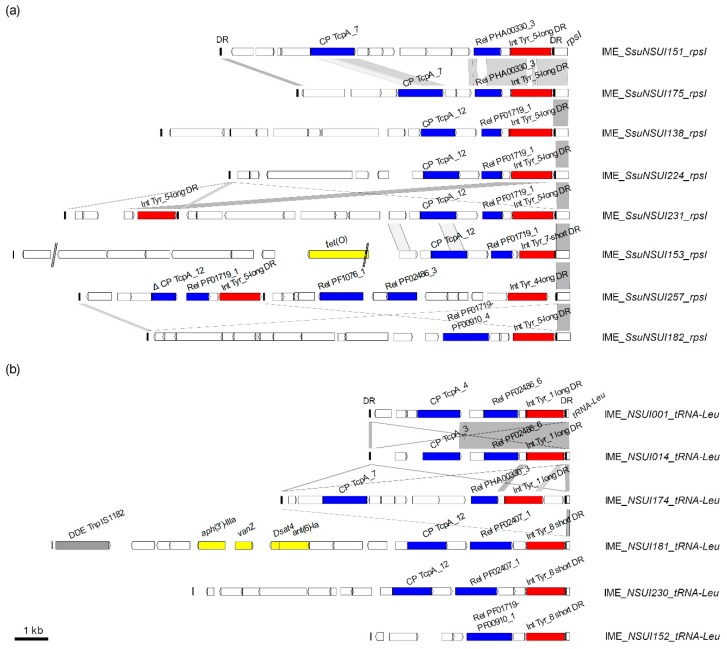

Figure 6.

Comparison of integrative and mobilizable elements (IMEs) integrated (a) into rpsI and (b) into a tRNALeu gene in S. suis. IMEs are named according to their host strains and integration sites. Direct repeats are indicated as black vertical rectangles. Coding DNA sequences (CDSs) appear as arrows (truncated genes are indicated by deltas). The integrase genes appear in red. The relaxase and coupling protein genes appear in blue. The different integration genes (rpsI and tRNALeu gene) targeted by the integrase are indicated in the figure and are part of the IME name. Genes encoding proteins with putative function inferred from in silico analysis are indicated (in yellow for antimicrobial resistance genes and in gray for transposase genes). Nucleic acid sequence identity between sequences is indicated in light gray when >80% of identity and in dark gray when higher than 90% of identity. Gaps in the assembly are indicated by a double slash.

2.2. Antimicrobial Resistance Genes Carried by Chromosomal MGEs in S. suis

All acquired AMR genes (n = 393) detected in the 214 genomes of S. suis were located on MGEs (Table S1). For strains of serotype 2 and MLST group ST25, the detected resistance genes support previously described phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility determinations [11]. In addition, to select strains for downstream analysis (see below), the susceptibility to chloramphenicol, kanamycin, tetracycline, lincomycin, and erythromycin of 14 strains of serotype 2/MLST group ST28 was evaluated in this study. In all cases, resistance genes matching the observed resistance phenotype were detected by in silico analysis, thus supporting the notion that these genes are fully functional and expressed by the corresponding S. suis strains.

2.2.1. ICEs carrying AMR Genes in S. suis

A total of 55 AMR genes were found on ICEs (excluding ICEs hosting IMEs carrying AMR genes).

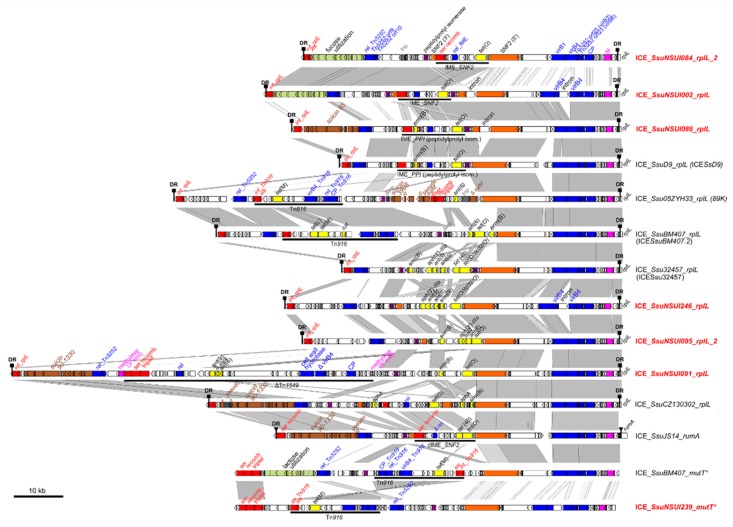

Most of the ICEs carrying AMR genes belong to the Tn5252 family (see Figure 7 for representative ICEs of this family).

Figure 7.

Comparison of the integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) belonging to the Tn5252 family and carrying AMR genes found in S. suis. ICEs are named according to their host strains and integration sites. When another name has already been published for the element, it is indicated in brackets. ICEs identified in this work are indicated in red. For more clarity, elements in accretion with ICEs of the Tn5252 family are not shown in the figure. ICEs or IMEs integrated inside ICEs are indicated as black lines with an indication of the name of the element. Nucleic acid sequence identity higher than 80% between two sequences is indicated in light gray and that higher than 90% in dark gray. Direct repeats (DR) delimiting ICEs are shown as squares or triangles depending on the integration gene (rplL, rumA or mutT *). Coding DNA sequences (CDSs) appear as arrows (truncated genes are indicated by deltas). Modules of recombination (integrase [int], excisionase [xis] and serine recombinase genes [ser recomb]) and conjugation appear in red and blue, respectively. The different integration sites (rplL, rumA, mutT *) targeted by the integrase are indicated in the figure and are part of the ICE name. Genes encoding proteins with putative function inferred from in silico analysis are indicated in yellow for antimicrobial resistance genes, in orange for SNF2, in purple for the peptidylprolyl isomerase gene, in green for sugar metabolism cluster, in pink for methylase genes, in gray for transposase genes, and in brown for bacteriocin synthesis clusters.

AMR genes were also found on four other ICE families (Figure 8). The first one is the vanG family with elements integrated into a lysS gene (with a tet(W) gene). The second one is the TnGBS2 family (one ICE with tet(L)-ant(6)-Ia-aph(3′)-IIIa genes). Interestingly, a thorough analysis of the TnGBS2-related ICE indicated that the cluster of AMR genes could have been brought by the integration of an IME inside the ICE. Indeed, a gene encoding a serine recombinase was detected as well as a gene encoding a relaxase with a PF01076 domain (MobV family). The third family is the Tn916 family with two Tn916 and two ICEs (carrying an erm(B) gene) with a conjugation module distantly related to the one of Tn916 that are integrated into a tRNAArg gene. These latter are almost identical to Tn6194 previously characterized in Clostridioides difficile CII7 [24]. The fourth family is the Tn1549 family with two ICEs (carrying erm(B)) found in rbgA and a dICE (with ant(6)-Ia-ant(9)-Ia-Δsat4 genes) integrated in a newly reported integration site i.e., a gene encoding a methylase located on a Tn5252-related ICE (Figure 8 and Table S1).

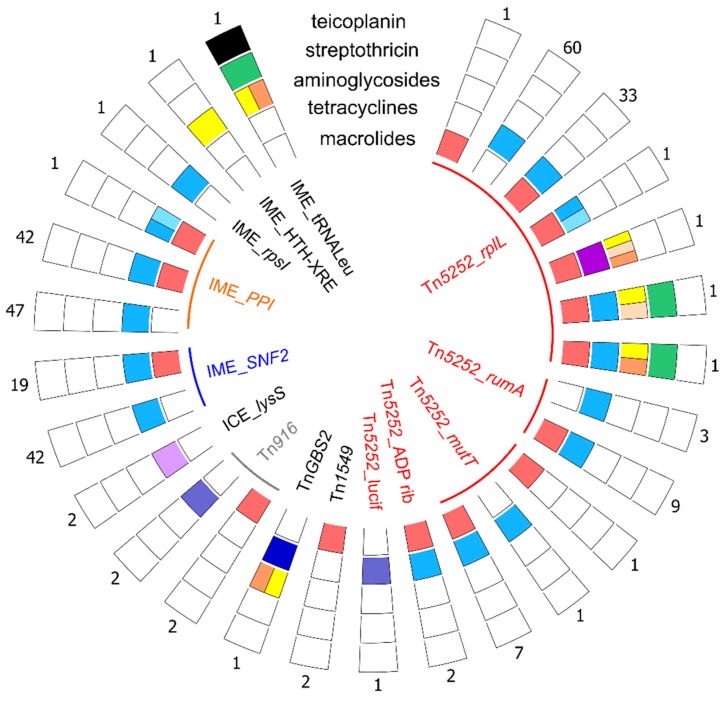

Figure 8.

ICEs and IMEs carrying AMR genes in the 214 genomes of S. suis analyzed. Each panel of boxes represents the combination of AMR genes present on the corresponding ICE or IME indicated in the inner circle. ICEs are grouped by families (with an indication of the integration site for ICEs of the Tn5252 family) and IMEs by integration sites. Each outer circle corresponds to resistance genes against a family of antibiotics: teicoplanin, streptothricin, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines and macrolides (from outside to inside). Different colors are used for the boxes to distinguish the AMR genes: black for vanZ, green for sat4, yellow for ant(6)-Ia, salmon for ant(9)-Ia, orange for aph(3′)-IIIa, light blue for tet(40), blue for tet(O), darker blue for tet(M) (on Tn916) and tet(L) (on TnGBS2), light purple for tet(W) and deep purple for tet(O/W/32/O) and red for erm(B). The number of corresponding elements is indicated at the extremity of each panel of boxes. ICEs of the Tn5252 family are all counted even if the AMR genes are carried by IMEs integrated inside a conserved gene of the ICEs.

2.2.2. IMEs Carrying AMR Genes in S. suis

More than half of the detected AMR genes (n = 221) were found on putative IMEs.

The mobilization modules of these IMEs carrying AMR genes include unrelated relaxases belonging to three families (Table S1).

Most of them carry tet(O) (that confers resistance to tetracycline) (n = 89) or tet(O) and erm(B) (that confers resistance to macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramin B) (n = 62) (Figure 8) and are themselves carried by ICEs of the Tn5252 family. They are integrated into SNF2 (for example, in ICE_SsuNSUI002_rplL, Figure 7) or into PPI (for example, in ICE_SsuNSUI086_rplL and the previously described ICE_SsD9 [14], Figure 7).

IMEs carrying AMR genes were also detected in three additional integration sites in S. suis genomes: one in the rpsI gene (carrying a tet(O) gene), one in a gene encoding a putative HTH-XRE regulator (with ant(6)-Ia), and one in a tRNALeu gene. This latter carries four different AMR genes: aph(3’)-IIIa-vanZ-sat4-ant(6)-Ia (Figure 8) conferring resistance to kanamycin, teicoplanin (low-resistance), streptothricin, and streptomycin, respectively. The encoded VanZ protein displays only 38% of identity with the one previously described in S. suis GZ0565 [25]. However, interestingly, it shows 100% of identity with the one encoded by an IME integrated inside a Tn1549-related ICE—itself integrated with a Tn5252-related ICE—in Streptococcus lutetiensis (ICESluvan) [17,26]. These two IMEs carrying vanZ differ by their integrase and mobilization proteins (different relaxase and presence of a coupling protein only for the IME integrated into a tRNALeu gene).

2.2.3. Other MGEs Carrying AMR Genes in S. suis

AMR genes were also found on prophages (n = 33, Table S1), most of them being integrated in rumA.

AMR genes were also located on genomic islands (GI) which correspond either to partial ICEs or elements deriving from ICEs (n = 40) or to elements for which no relaxase has been detected and were not categorized as IMEs in this work (n = 45, called GI in Table S1).

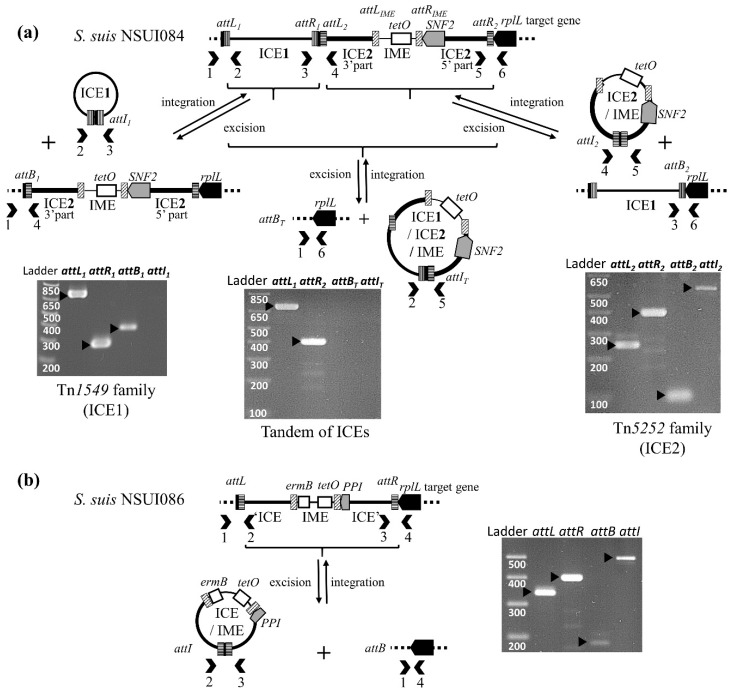

2.3. Excision and Transfer of ICEs and IMEs in S. suis

Two strains carrying putative ICEs—NSUI084 and NSUI086—were selected for the experimental part of the work. Strain NSUI084 carries two ICEs: an ICE of the Tn1549 family (ICE_SsuNSUI084_rplL_1) in accretion with an ICE of the Tn5252 family (ICE_SsuNSUI084_rplL_2 integrated into the rplL gene as shown in Figure 7). This latter hosts an IME integrated into its SNF2 gene. Strain NSUI086 carries an ICE of the Tn5252 family that hosts an IME integrated into the PPI gene of the ICE (ICE_SsuNSUI086_rplL shown in Figure 7).

PCR experiments were carried out in order to evaluate the excision ability of the ICEs and the hosted IMEs. For strain NSUI084, PCR results indicated that elements of the Tn1549 and Tn5252 families are able to excise as separate elements but not as a Tn1549-Tn5252 tandem. By contrast, IME_SsuNSUI084_SNF2 does not appear to excise, at least in the laboratory conditions tested (Figure 9). For strain NSUI086, the Tn5252-related element was able to excise but not IME_SsuNSUI086_PPI (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

PCR detection of integrated and excised forms of: (a) ICEs of strain NSUI084: whole tandem structure or Tn1549 (ICE1) and Tn5252 (ICE2) separate elements; (b) ICE_SsuNSUI086_rplL. The sizes of the PCR fragments obtained for the amplification of controls attL (left site of the integrated element) and attR (right site of the integrated element), attB (empty site) and attI (circular form) were confirmed by parallel migration of a DNA ladder. The primers pairs used for these amplifications are listed in Table S2.

Whereas IME_NSUI084_SNF2 fulfills all the requirements for an active IME, a thorough sequence re-analysis of IME_SsuNSUI086_PPI revealed that it is likely a defective IME (and thus should not be called IME). Indeed, the erm(B) gene and two other CDSs are carried by a genetic element—a 1.7 kb-erm(B) element—that is integrated into the serine integrase gene of the IME, leading to a truncated gene. This erm(B) element is related to the one described in Tn6002 ICE [27]. PCR experiments—by both PCR and nested PCR—did not show excision of the erm(B) element (data not shown).

Many defective elements related to IME_NSUI084_SNF2 and IME_SsuNSUI086_PPI or signatures of the integration of these IMEs—truncated SNF2 or PPI genes—were detected in the genomes (Figure 7 and Table S1).

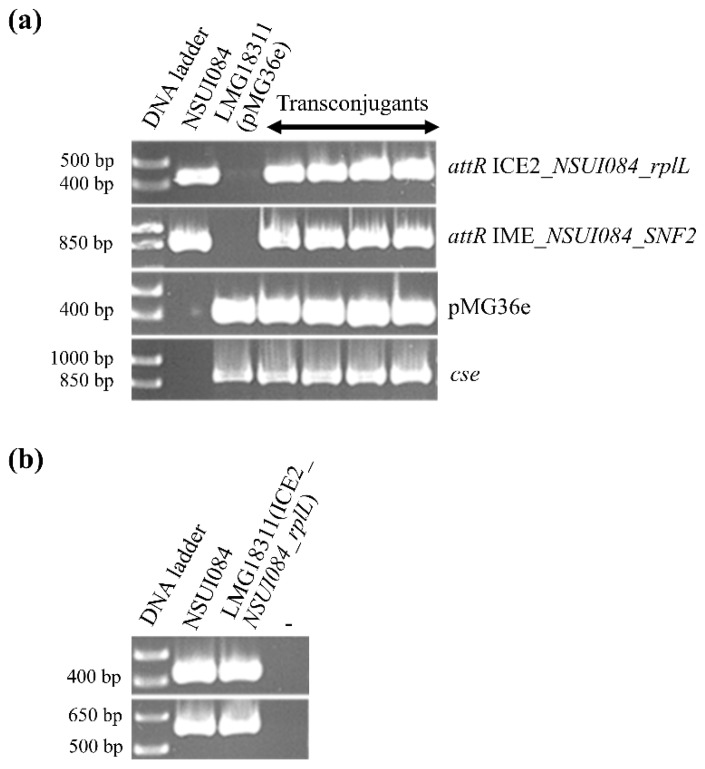

Conjugation experiments were carried out in order to evaluate the conjugative transfer of Tn5252-related ICEs from strains NSUI084 and NSUI086 (ICE_SsuNSUI084_rplL and ICE_SsuNSUI086_rplL respectively). Whatever the donor, no transconjugant was obtained using S. suis NSUI029 strain as a recipient (frequency below the detection limit of 10−7 per donor cells). By contrast, a conjugative transfer of ICE_SsuNSUI084_rplL_2—the Tn5252-related ICE part of the composite element—was obtained using S. thermophilus LMG18311 (pMG36e) as a recipient (at a high frequency of 2 × 10−3 ± 1.10−3 per donor cells). This ICE was still able to excise from the rplL site in the transconjugants (Figure 10), but as in the initial donor strain, IME_NSUI084_SNF2 hosted by the ICE was still unable to excise (data not shown). One of these transconjugants was used as a donor in mating experiments after plasmid curing with S. thermophilus LMG18311 (pMG36e) as a recipient. Transconjugants were obtained indicating that the ICE is able to retransfer (with a similar frequency) (Figure S2).

Figure 10.

Characterization of transconjugants of S. thermophilus LMG18311 (pMG36e) carrying ICE_SsuNSUI084_rplL_2 obtained after interspecies mating with S. suis NSUI084. (a) PCR experiments were done to amplify the right attachment site of ICE_SsuNSUI084_rplL_2 (attR_Tn5252_84) and of IME_SNF2 hosted by this ICE (attR_IME_84), the erm(B) gene carried by pMG36e (pMG36e) and a gene-specific of S. thermophilus (cse); (b) excision tests on one of these transconjugants (LMG18311 Tn5252 by comparison with the control donor strain NSUI084) before using it in retransfer experiments, attR on the upper panel and attI detection on the lower panel (-: negative control of PCR mix without DNA).

The viability of recipient cells of S. suis NSUI029 and S. thermophilus (LMG18311 (pMG36e) or JIM8232 (pMG36e)) was affected after contact with the NSUI086 S. suis donor strain. Further testing revealed that this strain produces a bacteriocin that was toxic for these recipient strains (Figure S3). Strains from two species that appeared resistant to this bacteriocin (Enterococcus faecalis JH2-2 (pMG36c) and Streptococcus salivarius JIM8777 (pMG36c), Figure S3) were thus tested as recipient cells in following mating assays. However, conjugative transfer of ICE_SsuNSUI086_rplL was not observed even when using these strains (indicating a frequency below the detection limit of 10−7 per donor cells).

2.4. Suicin Synthesis Clusters Carried by ICEs in S. suis

Observations made during conjugation experiments with strain NSUI086 prompted us to search for the presence of bacteriocin synthesis clusters in our set of 214 genomes of S. suis. Three suicin synthesis clusters have been described in S. suis: suicin 65, 90–1330, and 3908 synthesis clusters [28,29,30]. These clusters have already been described in the ST25 and ST28 strains analyzed in this study [31].

Our sequence analysis indicated that suicin 65 clusters are located on ICEs of the Tn5252 family integrated into the rplL gene (as for example in ICE_SsuNSUI086_rplL, Figure 7). Fifteen strains belonging to various serotypes carried a complete suicin 65 cluster of genes.

A full suicin 90-1330 cluster of genes was found on an ICE in four strains (as in the published ICE ICE_SsuCZ130302-rplL [16]).

A partial suicin 3908 cluster of genes was detected on an ICE in one strain of our collection (as in ICE_Ssu05ZYH33_rplL [32]) (Table S1, Figure 7).

3. Discussion

This large-scale genome analysis reveals the high diversity of putative MGEs transferring by conjugation (ICEs and IMEs) in S. suis.

In addition to the five families of ICEs already reported in S. suis (Tn5252, Tn1549, TnGBS2, Tn916, and vanG) [13,15], ICEs of the ICESt3 and TnGBS1 families were also detected in a few strains. These families are frequent in other streptococci [21,33,34] but were not reported in S. suis until now. As described in previous studies, Tn5252-related ICEs appear as the most prevalent ones. A new chromosomal integration site (ADP ribose pyrophosphatase gene) was detected in this work for this family, leading to a total of six different reported target genes for Tn5252-related ICEs. The second most prevalent family of ICEs is Tn1549-related elements. As already described by Huang et al. [13], most of them are integrated in tandem with Tn5252-related elements. Thus, whereas accretion of ICEs is rarely described in bacteria, Tn1549-Tn5252 tandem accretion appears very frequent in S. suis. ICEs of the other families appear less frequent (2–16 elements with full sequence detected in the genomes). It also appears that ICEs of the same family can co-exist in the same strain. This likely contributes to the evolution of the elements by enabling gene or module exchanges. Evidence of such recombination events was obtained by pairwise-comparison of ICEs.

Putative IMEs appear even more widespread than ICEs in S. suis. A thorough analysis of these genetic elements indicates a huge diversity of integration specificities (13 different ones). Some of these integration sites (PPI, three sites inside ICEs of the Tn1549 family and gene encoding a HTH-XRE regulator) are reported here for the first time. This further extends the repertoire of IMEs found in Streptococci [23]. Twenty-two different combinations of integrase-relaxase-(coupling protein) were observed. This indicates a high dynamics of evolution and plasticity of IMEs as suggested previously [22]. As for ICEs, tandem accretion of IMEs also exists, enabling gene exchange and increasing the evolution potential of these elements. As observed in a previous study on complete genomes of streptococci [22], we did not find IMEs carrying canonical relaxases of the MobF or MobH families but the four other canonical families (MOBP, MOBQ, MOBV, and MOBC) were detected. More importantly, half of the IMEs harbor a putative non-canonical relaxase, i.e., related to RCR initiators (MOBT, PF01719, PF01719-helicase, PHA00330 or PF02407) and in most cases these IMEs also encode a coupling protein (always from the TcpA family). As proposed previously [23], IMEs encoding relaxases related to RCR initiators can likely only hijack conjugative elements that encode TcpA. The elements that encode a TcpA coupling protein could probably replace the CP from the T4SS of the helper conjugative element by their own CP to promote their transfer (likely at the expense of the helper element).

In this work, genetic elements encoding an integrase but for which no relaxase was detected were not categorized as IMEs but rather as GIs. This does not mean that they should be considered as not transferable by conjugation but rather that further evidence of possible mobilization is needed. In particular, GI integrated into rpsI could be mobilizable by subverting the relaxase and mating apparatus of a co-resident ICE. Indeed, the transfer of such element—mis-annotated as an ICE even if it does not carry any conjugation gene—was described recently (at a very low frequency: 3.7×10−9 per donor) [35]. It should be pointed out that such elements are more difficult to detect in the genomes and are likely overlooked. In addition, elements with an incomplete conjugation module that we called dICEs are likely still able to excise and thus could still transfer to other cells by using the conjugation apparatus of the other resident ICEs (mobilization in trans).

Almost 400 antimicrobial resistance genes were detected in the 214 genomes analyzed.

A total of 55 of these AMR genes were found on ICEs. Most of the ICEs carrying AMR genes belong to the Tn5252 family that has already been largely described as AMR genes vehicle in S. suis [12,15]. Some of them carry novel combinations of AMR genes compared to ICEs previously described by Huang et al. [13] and Palmieri et al. [15]. AMR genes were also found on four other families (Tn1549, TnGBS2, Tn916 and vanG family). An ICE, related to TnGBS2 of Streptococcus agalactiae [36], that carries three AMR genes was identified in one strain of serotype 9, which is the most important and prevalent serotype causing disease in pigs in many European countries [5]. To our knowledge, this is the first case of TnGBS2 element carrying AMR genes. A thorough analysis of this ICE indicated that the cluster of AMR genes (ant(6)-Ia, aph(3′)-IIIa, tet(L) conferring resistance to streptomycin, kanamycin and tetracycline, respectively) could have been brought by the integration of an IME inside the ICE. Indeed, a gene encoding a serine recombinase was detected as well as a gene encoding a relaxase of the MobV family. The sequence of this putative IME is partial since the two genes are located on separate contigs of the genome, so it is difficult to conclude. Among the Tn916-elements, two ICEs—carrying an erm(B) gene and integrated into a tRNAArg gene—show a conjugation module distantly related to the one of Tn916 and are almost identical to Tn6194 previously characterized in Clostridioides difficile CII7 [24]. Conjugative transfer of the ICE of C. difficile was previously demonstrated towards Enterococcus faecalis. In C. difficile, the ICE was found integrated with various genes (including a tRNAArg gene) whereas, as observed in S. suis, it was found only in a tRNAArg gene in E. faecalis [24]. ICEs of this family are more promiscuous than the other ICE families and could contribute to AMR dissemination not only to streptococci but also to other Firmicutes. An AMR gene (tet(W)) was also found on ICEs of the vanG family integrated into the lysS gene in 2 strains of S. suis belonging to serotype 9. These ICEs are almost identical to ICE_SsuGZ1_lysS described previously [15].

More surprisingly, more than half of the detected AMR genes are carried by putative IMEs. It is important to mention that this is the first report of IMEs carrying AMR genes in S. suis. Most of the IMEs carrying AMR genes are integrated into SNF2 or PPI. They are also carried by ICEs as previously described, but were not recognized as IMEs by the authors of these works [12,14]. These IMEs are related to the tet(O) fragment integrated into ICESp2905 described in Streptococcus pyogenes [37]. AMR genes were also found on IME integrated into rpsI, tRNALeu, and in a gene encoding an HTH-XRE regulator. Interestingly, the vanZ gene found on an IME_tRNALeu exhibits 100% of identity with the one encoded by an IME (not identified as an IME by the authors) integrated inside a Tn1549-related ICE—itself integrated into a Tn5252-related ICE—in Streptococcus lutetiensis (ICESluvan) [17,26]. This suggests a capture of this resistance gene by different genetic elements rather than clonal dissemination of MGEs carrying this gene.

Some AMR genes were also detected on prophages integrated into rumA. Since this gene is also a hotspot of integration of ICEs, this could lead to the formation of composite elements between ICEs and prophages as described previously [15].

ICEs of S. suis do not only carry AMR genes but also bacteriocin synthesis clusters. As described recently for suicin 90–1330 [38] and for ICE_Ssu05ZYH33_rplL [32]—suicin 65 clusters also appear located on ICEs of the Tn5252 family integrated into the rplL gene. All the three suicins (suicin 65, 90-1330, and 3908) described in S. suis appear bactericidal for highly virulent ST1 strains of S. suis [28,29,30]. However, the carriage of the corresponding biosynthesis clusters on ICEs will hamper their suggested use as an alternative to antibiotics [39] since these MGEs will contribute to the dissemination of resistance genes to these suicins.

Experimental work was also done in order to evaluate the mobility of several ICEs (ICEs of the Tn5252 family hosting an IME, in tandem or not with a Tn1549 ICE). Excision of the whole Tn5252-Tn1549 tandem was not observed but the two ICEs were able to excise separately. The Tn5252-related ICE part of the tandem was successfully transferred to S. thermophilus. Thus, accretion of the ICEs does not hamper their mobility and interspecies gene transfer can occur. No excision of the IMEs hosted by the ICEs (IME_SNF2 and IME_PPI) was detected in the tested conditions. For one of them (IME_NSUI086_PPI), this is due to the insertion of an erm(B) element in the gene of the serine integrase that impairs the production of active full-length integrase. This can be viewed as a matrioshka: erm(B) element integrated into IME_PPI that is itself integrated into an ICE of the Tn5252 family. The erm(B) element found in this putative IME is related to the erm(B) element described in the ICE Tn6002 [27]. In this ICE, which belongs to the Tn916 family, the erm(B) element is integrated into the 3′ end of the relaxase gene of the ICE and extends the length of the gene (adding 71 amino acids at the C terminal end of the relaxase protein, without any other modification). This does not impair the conjugative transfer of Tn6002 [27]. The other IME studied in this work (IME_NSUI084_SNF2) fulfills all the requirements for an active IME but still, its excision was not detected. This suggests that either this IME is not mobile anymore as a single element but is transferred passively by the ICE that hosts it (whose conjugative transfer to S. thermophilus was observed), or that the IME excision occurs only in specific conditions not met in our laboratory experiments. Many defective elements related to these IMEs were detected in the genomes, suggesting that after integration in the ICEs, these elements undergo decay and lose their mobility.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Conditions

Characteristics of the strains used in this study are indicated in Table 1. Two strains of S. suis carrying an ICE of the Tn5252 family—that itself hosts an IME integrated into the SNF2 gene (strain NSUI084) or PPI gene (strain NSUI086)—were selected as donor strains for the conjugation experiments. Transfer was followed using the AMR genes—tet(O) or tet(O)/erm(B)—carried by the IMEs. Strain NSUI029 is susceptible to erythromycin and tetracycline and does not carry an ICE of the Tn5252 family at the rplL site. NSUI029 (pMG36c) that carries a plasmid conferring chloramphenicol resistance was used as a recipient. Strains of other species were also tested as recipients in mating experiments (Streptococcus salivarius JIM8777, S. thermophilus LMG18311 and JIM8232, E. faecalis JH2-2). S. suis, S. thermophilus and E. faecalis strains were grown in M17 broth supplemented with 0.5% lactose (LM17) at 37 °C. When required, cultures were supplemented with the following antibiotic concentrations: tetracycline, 6 mg/L; erythromycin, 5 mg/L; chloramphenicol, 4 mg/L.

Table 1.

Strains used in the experimental part of the work.

| Strains | Relevant Phenotype or Genotype | Sequence Type | Source or Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. suis | |||

| NSUI029 | Wild-type (WT) pig isolate devoid of Tn5252 element at the rplL site (but carrying an element of the Tn1549 family at this site), TetS 1 and EryS 2 | ST28 | [40] |

| NSUI029 (pMG36c) | NSUI029 carrying pMG36c, a plasmid conferring chloramphenicol resistance, CmR 3 | ST28 | This work |

| NSUI084 | WT pig isolate carrying putative ICEs of the Tn1549 (ICE_SSuNSUI084_rplL_1) and the Tn5252 (ICE_SsuNSUI084_rplL_2) families. The latter hosts an IME (IME_SsuNSUI084_SNF2) that carries a tet(O) gene, TetR 1 | ST28 | [40] |

| NSUI086 | WT pig isolate carrying a putative ICE of the Tn5252 family (ICE_SsuNSUI086_rplL) which hosts an IME (IME_SsuNSUI086_PPI) that carries a tet(O) and an erm(B) gene, TetR 1 and EryR 2 | ST28 | [40] |

| S. salivarius | |||

| JIM8777 | WT commensal strain with an empty rplL site | [41] | |

| JIM8777 (pMG36e) | JIM8777 carrying pMG36e, a plasmid conferring erythromycin resistance, EryR 2 | [42] | |

| S. thermophilus | |||

| LMG18311 | WT strain with empty rplL site | BCCM/LMG | |

| LMG18311 (pMG36e) | LMG18311 carrying pMG36e, a plasmid conferring erythromycin resistance, EryR 2 | [43] | |

| JIM8232 | WT strain carrying a putative ICE of the Tn5252 family in the rplL gene and IMEs in the rpsI, tRNALys and tRNALeu genes. | [44] | |

| JIM8232 (pMG36e) | JIM8232 carrying pMG36e, a plasmid conferring erythromycin resistance, EryR 2 | This work | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | [43] | ||

| JH2-2 (pMG36e) | JH2-2 carrying the plasmid pMG36e conferring erythromycin resistance, EryR 2 |

1 TetS or R, susceptibility or resistance to tetracycline; 2 EryS or R, susceptibility or resistance to erythromycin; 3 CmR, resistance to chloramphenicol.

4.2. Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

Bacterial genomes analyzed in this work were sequenced previously [11,40,45]. DNA sequencing short-reads (see accession numbers listed in Table S1) were retrieved from the Sequence Read Archive of NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra). De novo assemblies were carried out with the A5 pipeline [46]. Contigs were annotated with Prokka (v. 1.12, [47]).

4.3. Search for ICEs, IMEs and for Resistance Genes in Streptococcal Genomes

The overall workflow of the strategy used to detect, characterize, and delineate ICEs and IMEs in streptococcal genomes was described previously [10,22].

Resistance genes were searched using MegaBlast (using default NCBI parameters and no filtering) against the ARG-annot database [48] (as uploaded on 2017/06/25).

The localization of the resistance genes on chromosomal genetic elements (ICEs, IMEs, prophages or other genomic elements) was thoroughly examined by visual inspection of surrounding genes in the genome and analysis of their putative function by CD-search on NCBI website.

4.4. Comparative Analysis of Genetic Elements

Pairwise comparisons of elements were performed with Artemis Comparison Tool provided by the Sanger Centre [49]. Protein clustering was done as described previously [22]. Circos6 was used to show the signature protein associations and the content of MGEs of each strain [50].

4.5. Phylogenetic Tree Based on MLST Data

A Fasta file with the concatenated sequences of the aroA, cpn60, dpr, gki, mutS, recA and thrA genes—according to the MLST scheme of S. suis described by King et al. [51]—was generated. These sequences were used to generate a phylogenetic tree using MEGA 7 and the maximum likelihood method (Tamura-Nei model) [52,53].

4.6. Excision Tests

PCR amplifications were done to detect left (attL) and right (attR) MGEs borders, the attI site of the circular form of the MGEs and the empty chromosomal integration site attB as described previously [54] (see Table S2 for primers used).

4.7. Mating Experiments

Mating experiments were done as described in Dahmane et al. [55]. Selection of transconjugants was made at 37 °C (for intraspecies S. suis mating), 39 °C (for interspecies from S. suis to S. thermophilus mating) or 42 °C (for intraspecies S. thermophilus mating) using tetracycline and chloramphenicol containing-LM17 plates. Mating frequency was reported as the number of transconjugants per donor CFU.

Plasmid curing of the transconjugants used as donor cells in retro-transfer experiments was done as described previously [55].

4.8. Tests of Production of Bacteriocin

The multilayer method was done as described by Fontaine et al. [56]. Briefly, a fresh culture of donor S. suis strains at an OD600 of 1 was diluted 106-fold in 6 mL of prewarmed soft LM17 (0.8% agar) and poured on a solid LM17 plate. After a 24 h-incubation at 37 °C, a second 6 mL soft LM17 layer of 40-fold diluted fresh culture of the recipient strains at an OD600 of 1 was poured on the top. Plates were incubated 12 h at an optimal growth temperature of the recipient strain and the presence of an inhibition zone surrounding the donor colonies was evaluated.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, our results indicate high diversity and prevalence of integrated MGEs carrying AMR genes and transmissible by conjugation in S. suis.

A large part of them corresponds to ICEs and dICEs belonging to five families of ICEs (Tn5252, Tn916, TnGBS2, Tn1549, and vanG). Since most of these five families of ICEs are largely present in other streptococcal species and even in other Firmicutes, they certainly participate in the dissemination of AMR genes along the food chain but also in the environment.

More importantly, more than half of the AMR genes detected in S. suis genomes are carried by IMEs. This new finding indicates that this other category of integrative MGEs transferring by conjugation that has been very poorly studied until now likely plays a major role in the dissemination of AMR genes inside the S. suis species but also to other species sharing the same ecosystem.

Further studies are needed to evaluate such gene fluxes inside and between ecosystems and the contribution of ICEs and IMEs in these gene transfers bearing in mind a One Health global perspective.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/9/1/22/s1, Figure S1: Co-occurrence of relaxases, CPs and integrases among IMEs. Figure S2: Characterization of the transconjugants obtained after intraspecies transfer of ICE_SsuNSUI084_rplL_2 from S. thermophilus LMG18311(ICE_SsuNSUI084_rplL_2) to S. thermophilus LMG18311(pMG36e). Figure S3: Tests of production of bacteriocin by S. suis NSUI086 using a lawn of different indicative bacteria. Table S1: MGE genome content. Table S2: Primers used in this study to detect the integration and excision of putative mobile elements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.L., G.G., N.L.-B., and S.P.; methodology, V.L., G.G., N.L.-B., and S.P.; validation, V.L. and S.P.; formal analysis, V.L. and S.P.; investigation, V.L., Y.N., J.S., and S.P.; resources, C.C., M.G., S.T., N.F., G.G., and N.L.-B.; data curation, C.C., G.G., S.T., and N.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P.; writing—review and editing, V.L., G.G., M.G., N.F., N.L.-B., and S.P.; visualization, V.L. and S.P.; supervision, S.P.; funding acquisition, V.L., N.L.-B., and S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Région Lorraine and Université de Lorraine (2016–2017), the french PIA project «Lorraine Université d’Excellence», grant ANR-15-IDEX-04-LUE, and by the European Union through the Regional Operational Program of the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- 1.Feng Y., Zhang H., Wu Z., Wang S., Cao M., Hu D., Wang C. Streptococcus suis infection: An emerging/reemerging challenge of bacterial infectious diseases? Virulence. 2014;5:477–497. doi: 10.4161/viru.28595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huong V.T., Ha N., Huy N.T., Horby P., Nghia H.D., Thiem V.D., Zhu X., Hoa N.T., Hien T.T., Zamora J., et al. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and outcomes of Streptococcus suis infection in humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:1105–1114. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.131594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenberg T., Hudemann C., Hossain H.M., Hewer A., Tello K., Bandorski D., Rohde M., Valentin-Weigand P., Baums C.G. Characterization of five zoonotic Streptococcus suis strains from Germany, including one isolate from a recent fatal case of streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome in a hunter. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015;53:3912–3915. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02578-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomez-Torres J., Nimir A., Cluett J., Aggarwal A., Elsayed S., Soares D., Teatero S., Chen Y., Gottschalk M., Fittipaldi N. Human case of Streptococcus suis disease, Ontario, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017;23:2107–2109. doi: 10.3201/eid2312.171005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goyette-Desjardins G., Auger J.P., Xu J., Segura M., Gottschalk M. Streptococcus suis, an important pig pathogen and emerging zoonotic agent-an update on the worldwide distribution based on serotyping and sequence typing. Emerg. Microbes. Infect. 2014;3:e45. doi: 10.1038/emi.2014.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerdsin A., Hatrongjit R., Gottschalk M., Takeuchi D., Hamada S., Akeda Y., Oishi K. Emergence of Streptococcus suis serotype 9 infection in humans. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2017;50:545–546. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Europe 2017. Annual Report of the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; Stockholm, Sweden: 2018. [(accessed on 13 November 2019)]. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/EARS-Net-report-2017-update-jan-2019.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.HHS . The National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System: NARMS 2015 Integrated Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, FDA; Laurel, MD, USA: 2017. [(accessed on 13 November 2019)]. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/108304/download. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varela N.P., Gadbois P., Thibault C., Gottschalk M., Dick P., Wilson J. Antimicrobial resistance and prudent drug use for Streptococcus suis. Anim. Health. Res. Rev. 2013;14:68–77. doi: 10.1017/S1466252313000029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ambroset C., Coluzzi C., Guédon G., Devignes M.D., Loux V., Lacroix T., Payot S., Leblond-Bourget N. New insights into the classification and integration specificity of Streptococcus integrative conjugative elements through extensive genome exploration. Front. Microbiol. 2016;6:1483. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Athey T.B., Teatero S., Takamatsu D., Wasserscheid J., Dewar K., Gottschalk M., Fittipaldi N. Population structure and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 sequence type 25 strains. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0150908. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang J., Liang Y., Guo D., Shang K., Ge L., Kashif J., Wang L. Comparative genomic analysis of the ICESa2603 family ICEs and spread of erm(B)- and tet(O)-carrying transferable 89K-subtype ICEs in swine and bovine isolates in china. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:55. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang J., Ma J., Shang K., Hu X., Liang Y., Li D., Wu Z., Dai L., Chen L., Wang L. Evolution and diversity of the antimicrobial resistance associated mobilome in Streptococcus suis: A probable mobile genetic elements reservoir for other streptococci. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2016;6:118. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang K., Song Y., Zhang Q., Zhang A., Jin M. Characterisation of a novel integrative and conjugative element ICESsD9 carrying erm(B) and tet(O) resistance determinants in Streptococcus suis, and the distribution of ICESsD9-like elements in clinical isolates. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2016;7:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palmieri C., Varaldo P.E., Facinelli B. Streptococcus suis, an emerging drug-resistant animal and human pathogen. Front. Microbiol. 2011;2:235. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan Z., Liu J., Zhang Y., Chen S., Ma J., Dong W., Wu Z., Yao H. A novel integrative conjugative element mediates transfer of multi-drug resistance between Streptococcus suis strains of different serotypes. Vet. Microbiol. 2019;229:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellanger X., Payot S., Leblond-Bourget N., Guédon G. Conjugative and mobilizable genomic islands in bacteria: Evolution and diversity. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014;38:720–760. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grohmann E., Christie P.J., Waksman G., Backert S. Type IV secretion in gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 2018;107:455–471. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holden M.T., Hauser H., Sanders M., Ngo T.H., Cherevach I., Cronin A., Goodhead I., Mungall K., Quail M.A., Price C., et al. Rapid evolution of virulence and drug resistance in the emerging zoonotic pathogen Streptococcus suis. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng H., Du P., Qiu X., Kerdsin A., Roy D., Bai X., Xu J., Vela A.I., Gottschalk M. Genomic comparisons of Streptococcus suis serotype 9 strains recovered from diseased pigs in Spain and Canada. Vet. Res. 2018;49:1. doi: 10.1186/s13567-017-0498-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burrus V., Pavlovic G., Decaris B., Guédon G. The ICESt1 element of Streptococcus thermophilus belongs to a large family of integrative and conjugative elements that exchange modules and change their specificity of integration. Plasmid. 2002;48:77–97. doi: 10.1016/S0147-619X(02)00102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coluzzi C., Guédon G., Devignes M.D., Ambroset C., Loux V., Lacroix T., Payot S., Leblond-Bourget N. A glimpse into the world of integrative and mobilizable elements in streptococci reveals an unexpected diversity and novel families of mobilization proteins. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:443. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guédon G., Libante V., Coluzzi C., Payot S., Leblond-Bourget N. The obscure world of integrative and mobilizable elements, highly widespread elements that pirate bacterial conjugative systems. Genes. 2017;8:337. doi: 10.3390/genes8110337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wasels F., Monot M., Spigaglia P., Barbanti F., Ma L., Bouchier C., Dupuy B., Mastrantonio P. Inter- and intraspecies transfer of a Clostridium difficile conjugative transposon conferring resistance to MLSB. Microb. Drug Resist. 2014;20:555–560. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2014.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lai L., Dai J., Tang H., Zhang S., Wu C., Qiu W., Lu C., Yao H., Fan H., Wu Z. Streptococcus suis serotype 9 strain GZ0565 contains a type VII secretion system putative substrate EsxA that contributes to bacterial virulence and a vanZ-like gene that confers resistance to teicoplanin and dalbavancin in Streptococcus agalactiae. Vet. Microbiol. 2017;205:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bjorkeng E.K., Hjerde E., Pedersen T., Sundsfjord A., Hegstad K. ICESluvan, a 94-kilobase mosaic integrative conjugative element conferring interspecies transfer of VanB-type glycopeptide resistance, a novel bacitracin resistance locus, and a toxin-antitoxin stabilization system. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:5381–5390. doi: 10.1128/JB.02165-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warburton P.J., Palmer R.M., Munson M.A., Wade W.G. Demonstration of in vivo transfer of doxycycline resistance mediated by a novel transposon. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007;60:973–980. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LeBel G., Vaillancourt K., Frenette M., Gottschalk M., Grenier D. Suicin 90-1330 from a nonvirulent strain of Streptococcus suis: A nisin-related lantibiotic active on gram-positive swine pathogens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:5484–5492. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01055-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vaillancourt K., LeBel G., Frenette M., Fittipaldi N., Gottschalk M., Grenier D. Purification and characterization of suicin 65, a novel class I type B lantibiotic produced by Streptococcus suis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0145854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaillancourt K., LeBel G., Frenette M., Gottschalk M., Grenier D. Suicin 3908, a new lantibiotic produced by a strain of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 isolated from a healthy carrier pig. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0117245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Athey T.B., Vaillancourt K., Frenette M., Fittipaldi N., Gottschalk M., Grenier D. Distribution of suicin gene clusters in Streptococcus suis serotype 2 belonging to sequence types 25 and 28. BioMed Res. Int. 2016;2016:6815894. doi: 10.1155/2016/6815894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li M., Shen X., Yan J., Han H., Zheng B., Liu D., Cheng H., Zhao Y., Rao X., Wang C., et al. GI-type T4SS-mediated horizontal transfer of the 89K pathogenicity island in epidemic Streptococcus suis serotype 2. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;79:1670–1683. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brochet M., Couve E., Glaser P., Guédon G., Payot S. Integrative conjugative elements and related elements are major contributors to the genome diversity of Streptococcus agalactiae. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:6913–6917. doi: 10.1128/JB.00824-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puymège A., Bertin S., Guédon G., Payot S. Analysis of Streptococcus agalactiae pan-genome for prevalence, diversity and functionality of integrative and conjugative or mobilizable elements integrated in the tRNA(Lys CTT) gene. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2015;290:1727–1740. doi: 10.1007/s00438-015-1031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang K., Zhang Q., Song Y., Zhang Z., Zhang A., Xiao J., Jin M. Characterization of spectinomycin resistance in Streptococcus suis leads to two novel insights into drug resistance formation and dissemination mechanism. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016;60:6390–6392. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01157-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guérillot R., Da Cunha V., Sauvage E., Bouchier C., Glaser P. Modular evolution of TnGBSs, a new family of integrative and conjugative elements associating insertion sequence transposition, plasmid replication, and conjugation for their spreading. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:1979–1990. doi: 10.1128/JB.01745-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giovanetti E., Brenciani A., Tiberi E., Bacciaglia A., Varaldo P.E. ICESp2905, the erm(TR)-tet(O) element of Streptococcus pyogenes, is formed by two independent integrative and conjugative elements. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:591–594. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05352-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun Y., Veseli I.A., Vaillancourt K., Frenette M., Grenier D., Pombert J.F. The bacteriocin from the prophylactic candidate Streptococcus suis 90-1330 is widely distributed across S. suis isolates and appears encoded in an integrative and conjugative element. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0216002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cotter P.D., Ross R.P., Hill C. Bacteriocins—A viable alternative to antibiotics? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013;11:95–105. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Athey T.B., Auger J.P., Teatero S., Dumesnil A., Takamatsu D., Wasserscheid J., Dewar K., Gottschalk M., Fittipaldi N. Complex population structure and virulence differences among serotype 2 Streptococcus suis strains belonging to sequence type 28. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0137760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guédon E., Delorme C., Pons N., Cruaud C., Loux V., Couloux A., Gautier C., Sanchez N., Layec S., Galleron N., et al. Complete genome sequence of the commensal Streptococcus salivarius strain JIM8777. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:5024–5025. doi: 10.1128/JB.05390-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dahmane N., Libante V., Charron-Bourgoin F., Guédon E., Guédon G., Leblond-Bourget N., Payot S. Diversity of integrative and conjugative elements of Streptococcus salivarius and their intra-and interspecies transfer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017;83:e00337-17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00337-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bellanger X., Roberts A.P., Morel C., Choulet F., Pavlovic G., Mullany P., Decaris B., Guédon G. Conjugative transfer of the integrative conjugative elements ICESt1 and ICESt3 from Streptococcus thermophilus. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:2764–2775. doi: 10.1128/JB.01412-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Delorme C., Bartholini C., Luraschi M., Pons N., Loux V., Almeida M., Guédon E., Gibrat J.F., Renault P. Complete genome sequence of the pigmented Streptococcus thermophilus strain JIM8232. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:5581–5582. doi: 10.1128/JB.05404-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Athey T.B., Teatero S., Lacouture S., Takamatsu D., Gottschalk M., Fittipaldi N. Determining Streptococcus suis serotype from short-read whole-genome sequencing data. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:162. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0782-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tritt A., Eisen J.A., Facciotti M.T., Darling A.E. An integrated pipeline for de novo assembly of microbial genomes. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seemann T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gupta S.K., Padmanabhan B.R., Diene S.M., Lopez-Rojas R., Kempf M., Landraud L., Rolain J.M. Arg-annot, a new bioinformatic tool to discover antibiotic resistance genes in bacterial genomes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:212–220. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01310-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carver T., Berriman M., Tivey A., Patel C., Bohme U., Barrell B.G., Parkhill J., Rajandream M.A. Artemis and act: Viewing, annotating and comparing sequences stored in a relational database. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2672–2676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krzywinski M., Schein J., Birol I., Connors J., Gascoyne R., Horsman D., Jones S.J., Marra M.A. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome. Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.King S.J., Leigh J.A., Heath P.J., Luque I., Tarradas C., Dowson C.G., Whatmore A.M. Development of a multilocus sequence typing scheme for the pig pathogen Streptococcus suis: Identification of virulent clones and potential capsular serotype exchange. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002;40:3671–3680. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.10.3671-3680.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. Mega7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tamura K., Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1993;10:512–526. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carraro N., Libante V., Morel C., Charron-Bourgoin F., Leblond P., Guédon G. Plasmid-like replication of a minimal streptococcal integrative and conjugative element. Microbiology. 2016;162:622–632. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dahmane N., Robert E., Deschamps J., Meylheuc T., Delorme C., Briandet R., Leblond-Bourget N., Guédon E., Payot S. Impact of cell surface molecules on conjugative transfer of the integrative and conjugative element ICESt3 of Streptococcus thermophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018;84:e02109–e02117. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02109-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fontaine L., Boutry C., Guédon E., Guillot A., Ibrahim M., Grossiord B., Hols P. Quorum-sensing regulation of the production of Blp bacteriocins in Streptococcus thermophilus. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:7195–7205. doi: 10.1128/JB.00966-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.