Abstract

Purinergic signaling by extracellular ATP regulates a variety of cellular events and is implicated in both normal physiology and pathophysiology. Several molecules have been associated with the release of ATP and other small molecules, but their precise contributions have been difficult to assess because of their complexity and heterogeneity. Here, we report on the results of a gain-of-function screen for modulators of hypotonicity-induced ATP release using HEK-293 cells and murine cerebellar granule neurons, along with bioluminescence, calcium FLIPR, and short hairpin RNA–based gene-silencing assays. This screen utilized the most extensive genome-wide ORF collection to date, covering 90% of human, nonredundant, protein-encoding genes. We identified two ABCG1 (ABC subfamily G member 1) variants, which regulate cellular cholesterol, as modulators of hypotonicity-induced ATP release. We found that cholesterol levels control volume-regulated anion channel–dependent ATP release. These findings reveal novel mechanisms for the regulation of ATP release and volume-regulated anion channel activity and provide critical links among cellular status, cholesterol, and purinergic signaling.

Keywords: ATP, ion channel, high-throughput screening (HTS), ABC transporter, cholesterol, ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 1 (ABCG1), genome-wide ORF screen, hypotonic shock, neurotransmission, volume-regulated anion channel (VRAC)

Introduction

Intracellular molecules can mediate intercellular communications once secreted by cells. For example, ATP provides energy for numerous intracellular processes but also signals extracellularly through its cell surface receptors: the ionotropic purinergic P2X receptors and metabotropic P2Y receptors (P2YRs)2 (1–3). P2 receptors have an affinity for ATP (∼0.1–100 μm) corresponding to the low extracellular concentrations of ATP compared with intracellular levels (∼1–10 nm versus 1–10 mm, respectively) (2–7). The extracellular release of ATP is thought to be controlled by both an ATP pore and fusion of ATP-containing vesicles with the plasma membrane. Indeed, P2 receptors are not localized only at vesicular fusion sites but also are present all along the plasma membrane, which supports a nonvesicular mechanism of ATP release (8).

Cell volume is tightly controlled to maintain normal cellular function, and cell swelling upon hypotonic stimulation releases ATP, as well as other compounds (9–12), through ATP-permeable pores in the plasma membrane. Several molecules are proposed to mediate this stimulus-induced ATP release (5, 6), including calcium homeostasis modulator (CALHM) (13), pannexin/connexin (14, 15), P2X7 receptors (16), SLCO2A1 (17), and LRRC8 (18). However, the relative contributions of these channels and potential modulators of their activity are not clear. Systematic approaches, such as loss-of-function (LOF) and gain-of-function (GOF) screens, might identify other unknown factors involved in the regulation of ATP release.

The LOF approach to identify critical molecules typically involves the detection of phenotypes in genetically mutagenized model systems. For example, a genome-wide RNAi-based LOF screen identified LRRC8 as a component of volume-regulated anion channel (VRAC) (19, 20). However, this approach does not identify molecules with redundant functions, housekeeping genes that result in early lethality, or those with multiple functions that produce general phenotypes. By contrast, the GOF approach involves the detection of phenotypes via the overexpression of targeted genes. This approach benefits from its ability to identify molecules with functionally redundant homologs and from its high sensitivity based on high protein expression levels. Nevertheless, caution must be applied with this approach because abnormal gene function may be induced by artificially high expression. Furthermore, the cDNA library used in this approach can affect the outcome if the collection is biased toward certain cDNAs. To circumvent this issue, we prepared a collection of 17,284 nonredundant genes covering 90% of human protein-coding ORFs. We performed GOF analyses with this collection and identified ABCG1 as the most robust, specific modulator of purinergic signaling. Our studies further demonstrate that ABCG1 modulates hypotonicity-induced ATP release through LRRC8A-containing VRACs in a cholesterol-dependent manner. These findings shed light on novel modulatory machinery for the release of ATP and neurotransmitters that act in cell autonomous and nonautonomous manners.

Results

Assay development for genome-wide GOF screen

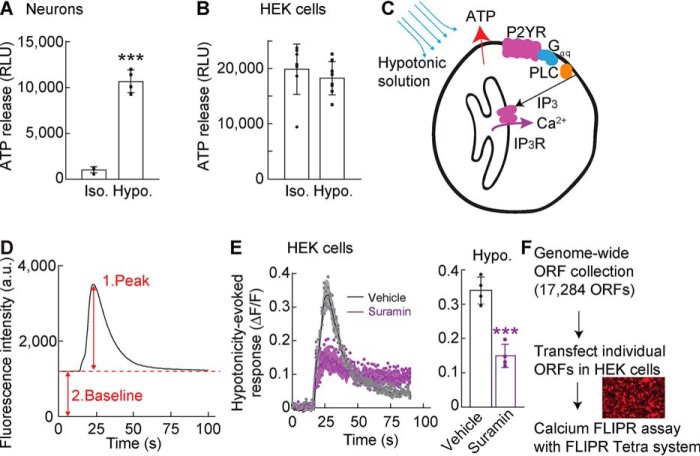

Hypotonicity induces ATP release (5, 6), which we observed by performing a luciferin–luciferase bioluminescence assay with cerebellar granule neurons treated for 30 s with a hypotonic solution (final concentration, 250 mmol/kg) (Fig. 1A). By contrast, HEK cell lines from frozen stocks responded differently to the hypotonic stimulation, and we identified a subline of HEK cells in which the hypotonic solution did not show a significant increase in extracellular ATP relative to isotonic solution (Fig. 1B). Therefore, this HEK subline was used for GOF screening.

Figure 1.

Establishing a screening platform for ATP release machinery. A and B, cerebellar granule neurons (A) or HEK cells (B) were plated and stimulated with conditioned HEPES-buffered saline (isotonic 330–340 mmol/kg; Iso.) or hypotonic solution (final concentration, 250 mmol/kg; Hypo.). Hypotonic stimulation increased ATP released from primary cerebellar neurons (n = 4) but not HEK cells (n = 8) relative to isotonic stimulation. RLU, relative luminescent unit. C, schematic diagram of hypotonic activation of Gq-coupled P2YR signaling in HEK cells. D, calcium responses using the calcium FLIPR assay. Each trace was analyzed by measuring a peak (1) response normalized to its baseline (2) response (ΔF/F). E, hypotonicity-induced calcium responses were measured with the calcium FLIPR assay in HEK cells preincubated without (vehicle) or with a P2 receptor antagonist, 300 μm suramin, for 15 min; traces and quantification of peak calcium response (ΔF/F) with error bars are shown (n = 4). F, overview of the GOF screen with a genome-wide ORF collection to identify modulators of hypotonicity-induced ATP release. The genome-wide ORF collection, including 17,284 nonredundant ORFs, was generated (see details under “Experimental procedures”). Each ORF was transfected transiently into HEK cells, followed by measurements of fluorescence intensity from each well using the calcium FLIPR assay. The data are means ± standard deviation; unpaired t test (A and E). ***, p < 0.001.

ATP release in response to hypotonicity can stimulate Gq-coupled P2YRs, which subsequently activate PLC and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors to induce the release of calcium from the endoplasmic reticulum into the cytosol (Fig. 1C). Thus, we evaluated changes in cytosolic calcium concentrations to indirectly evaluate hypotonicity-induced ATP release from the HEK cell subline. We performed calcium 4 dye-based FLIPR assays in a 384-well plate format and monitored real-time responses as changes in fluorescence analyzed as the peak fluorescence value normalized to each baseline value (ΔF/F) (Fig. 1D). With this method, a calcium response was observed in HEK cells in response to the application of the hypotonic solution (Fig. 1E). This response was significantly attenuated (p < 0.001) by an inhibitor of P2 receptors, 300 μm suramin, suggesting that ATP-activated P2 receptors mediate the hypotonicity-induced calcium response. Importantly, these results demonstrate that the calcium FLIPR assay can be used as a sensitive and real-time detector of ATP release.

To identify the machinery responsible for ATP release in a GOF screen, we utilized a nonredundant genome-wide ORF collection that included 3,896 transmembrane ORFs from OriGene and 15,743 ORFs from the Broad Institute (through Thermo Fisher Scientific). After comparison with the HUGO database (21), we cloned an additional 3,274 ORFs from the ORFeome Collaboration (22) into mammalian expression vectors. The final ORF collection contained 17,284 nonredundant ORFs (Fig. 1F), covering 90% of the 19,224 nonredundant human ORFs in the HUGO database, some of which were tagged with a V5 epitope at the C terminus. The HEK cells were transfected with these expression plasmids and some redundant ORFs (for a total 20,680 ORFs) in a 384-well plate format (80–90% transfection efficiency estimated by the red fluorescence from cells transfected with RFP using the same procedure; Fig. 1F, inset). Two days after transfection, stimulus-induced calcium responses were assayed using the FLIPR Tetra system. For this screen, we used a combined stimulus with a minimal difference in hypotonicity (i.e. 320 mmol/kg stimulant and 340 mmol/kg assay solution) to widen the range of screening and 100 μm glutamate to activate glutamate receptors as a control. We then calculated averages and standard deviations for the peak calcium responses (ΔF/F) for each 384-well plate. With this initial screen, we identified 45 ORFs that induced a calcium response >3 times the standard deviation above the plate mean.

Genome-wide ORF-based GOF screen identifies ABCG1 as a purinergic modulator

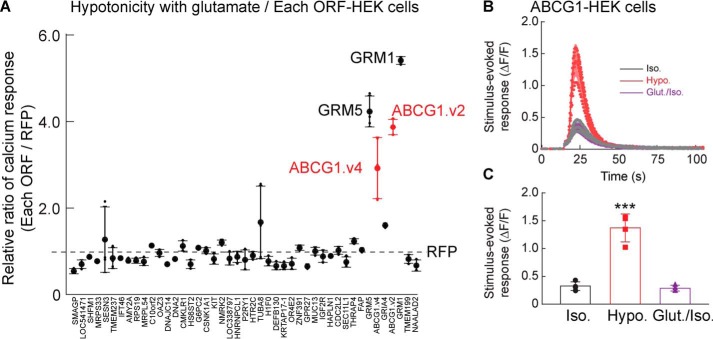

We next validated the 45 ORFs identified from the initial screen with three replicates (Fig. 2A). Calcium responses induced by stimulation with the minimum hypotonic assay solution containing 100 μm glutamate were notably high from HEK cells transfected with ORFs encoding GRM1, GRM5, ABCG1 variant 2, and ABCG1 variant 4 (Fig. 2A). GRM1 and GRM5 encode mGluR1 and mGluR5, respectively, which are Gq-coupled metabotropic glutamate receptors that modulate intracellular calcium signaling (23). ORFs encoding ionotropic glutamate receptors were not identified in this screen because their responses to 100 μm glutamate were much smaller in the absence of chemical potentiators or their auxiliary subunits. Of the two ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter ABCG1 variants, variant 2 is shorter and was used for subsequent experiments, because both variants induced similar responses. HEK cells harboring the ABCG1 ORF were treated with an isotonic solution (final concentration, 340 mmol/kg) or stimulated with a hypotonic solution (final concentration, 250 mmol/kg) or glutamate (final concentration, 100 μm) in the isotonic solution. The cells responded robustly to only the hypotonic solution (Fig. 2, B and C). These results indicate that ABCG1 is a novel enhancer of the hypotonicity-induced calcium response.

Figure 2.

Genome-wide ORF screen identifies ABCG1 as an enhancer of hypotonicity-induced calcium responses. Stimulus-induced calcium responses were measured from ORF-transfected HEK cells with the calcium FLIPR assay. A, HEK cells were transfected with 45 individual ORFs identified from the first GOF screen using the genome-wide ORF collection, and calcium responses induced by minimum hypotonic solution (320 mmol/kg stimulus and 340 mmol/kg assay solution) containing glutamate (final concentration, 100 μm) were measured. The relative ratios of calcium responses of ORF- to RFP-transfected HEK cells were calculated (n = 3). Higher responses were observed in HEK cells transfected with mGluR1, mGluR5, and two transcriptional variants (v1 and v2) of ABCG1. The dashed line indicates responses from RFP-transfected HEK cells. B and C, ABCG1-transfected HEK cells showed significantly different calcium responses to hypotonic solution (final concentration, 250 mmol/kg; Hypo.), but not to the isotonic solution (340 mmol/kg; Iso.) or that with glutamate (final concentration, 100 μm; Glut.); traces (B) and quantification of peak calcium response (ΔF/F) with error bars (C) are shown (n = 4). One-way ANOVA (F(2,9) = 63.64, p < 0.001) was used followed by Tukey's test (C). The data are means ± standard deviation. ***, p < 0.001.

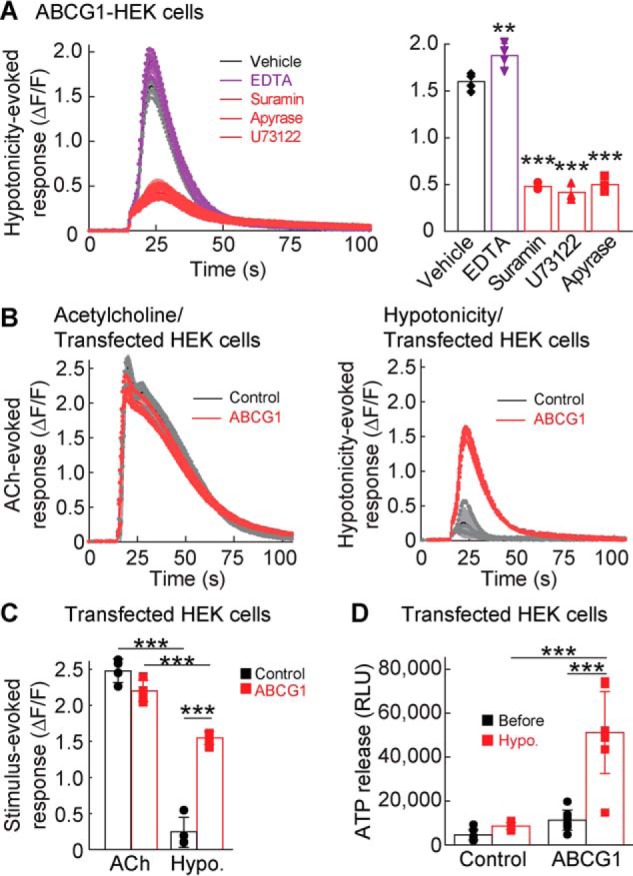

ABCG1 enhances hypotonicity-induced ATP release

We next investigated the mechanism by which ABCG1 expression enhances hypotonicity-induced calcium responses in the FLIPR assay. To exclude extracellular calcium as a potential source, we added 5 mm EDTA, a calcium chelator, to the media and observed a modest increase rather than a decrease in the hypotonicity-induced intracellular calcium responses (Fig. 3A). This suggests that the calcium source for the hypotonicity-induced calcium response is unlikely to be extracellular. Calcium can also be released intracellularly from the endoplasmic reticulum in an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate–dependent manner (Fig. 1C). Indeed, preincubation of ABCG1-transfected HEK cells with a PLC blocker, 10 μm U73122, as well as the P2R blocker, 300 μm suramin, for 15 min reduced the hypotonicity-induced calcium response significantly (p < 0.001). Similarly, the addition of an ATP diphosphatase, 10 unis/ml apyrase, to hydrolyze ATP to AMP in the medium reduced the hypotonicity-induced calcium responses. These results suggest that ABCG1 modulates Gq-coupled P2YR signaling.

Figure 3.

ABCG1 enhances hypotonicity-induced ATP release. A–C, calcium responses induced by hypotonic solution (final concentration, 250 mmol/kg) were measured in ABCG1-transfected HEK cells by using the FLIPR assay. A, addition of a calcium chelator (EDTA; final concentration, 5 mm) slightly increased the hypotonicity-induced calcium response (ΔF/F), whereas a 15-min preincubation with a P2 receptor blocker suramin (final concentration, 300 μm), a PLC blocker U73122 (final concentration, 10 μm), or the ATP diphosphatase apyrase (final concentration, 10 units/ml) significantly blocked the hypotonicity-induced calcium response in ABCG1-transfected HEK cells (one-way ANOVA; F(4,15) = 262.7; p < 0.001). B and C, Gq-coupled receptor signaling was unaltered by ABCG1 expression. Acetylcholine (ACh)–induced (final concentration, 100 μm) calcium responses from endogenous Gq-coupled mAChRs were measured in HEK cells transfected transiently with either ABCG1 or RFP (control). ABCG1 expression increased calcium responses stimulated by the hypotonic solution (final concentration, 250 mmol/kg); traces with error bars (B) and quantification of peak calcium responses (ΔF/F) with error bars (C) are shown (n = 4) (two-way ANOVA; F(1,12) = 326.6, p < 0.001 for stimulus comparison; F(1,12) = 40.98, p < 0.001 for ABCG1 comparison; interaction; F(1,12) = 99.85, p < 0.001). D, extracellular ATP in medium was measured before and after hypotonic stimulation (final concentration, 250 mmol/kg) of ABCG1- and RFP (control)–transfected HEK cells by using a luciferin–luciferase bioluminescence assay. ABCG1 increased hypotonicity-induced ATP release (n = 8) (two-way ANOVA; F(1,28) = 52.09, p < 0.001; for ABCG1 comparison; F(1,28) = 40.71, p < 0.001 for stimulus comparison; F(1,28) = 27.18, p < 0.001 for interaction. The data are means ± standard deviation; one-way ANOVA was followed by Tukey's test versus vehicle (A) or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test (C and D). **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. RLU, relative luminescent unit

To determine whether ABCG1 modulates other Gq-coupled receptors, we measured calcium responses in response to acetylcholine, because HEK cells endogenously express muscarinic-type acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs). We found that ABCG1 expression did not influence the ACh-induced calcium response but increased hypotonicity-induced calcium responses (Fig. 3, B and C). These results establish ABCG1 as a specific enhancer of hypotonicity-induced calcium responses through purinergic signaling.

This could be due to an increase in extracellular ATP upon hypotonic stimulation. Thus, we measured extracellular ATP amounts from HEK cells transfected with ABCG1 or RFP (control) before and 30 s after hypotonic stimulation. The medium was collected using a 96-well liquid handler, and ATP was measured using a luciferin–luciferase bioluminescence assay. ATP amounts were similar between RFP (control)– and ABCG1-expressing cells before stimulation but were significantly higher in ABCG1-expressing cells after hypotonic stimulation (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3D). Elevated ATP in the extracellular media could result from impaired ATP degradation extracellularly or increased ATP release from the cytosol. We verified that the ATP release and calcium response induced by hypotonicity were not due to impaired exonuclease activity. Hypotonicity-induced calcium responses and ATP release were similar between treatments with vehicle and 100 μm ARL67156 to block extracellular nuclease activity in both ABCG1- and RFP-transfected HEK cells (Fig. S1). From these results, we concluded that ABCG1 increases ATP release upon hypotonic stimulation.

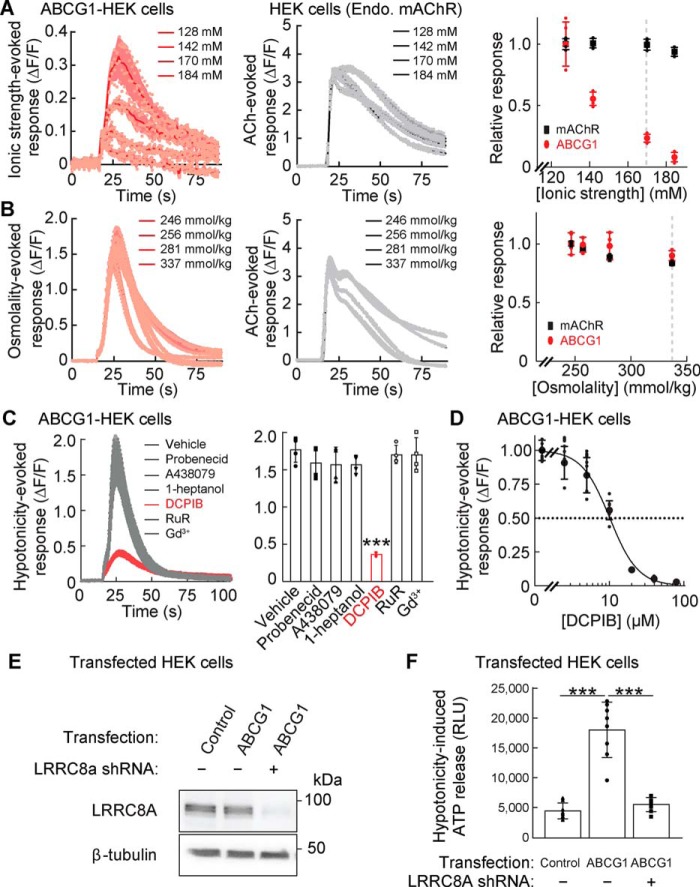

ABCG1-dependent ATP release is mediated by ionic strength and VRAC

To identify the component in the hypotonic solution inducing ATP/P2YR-dependent calcium responses in ABCG1-transfected cells, we evaluated the contributions of ionic strength and osmolality, which are lower under hypotonic conditions. We again used the calcium FLIPR assay to measure calcium responses from ABCG1-transfected HEK cells stimulated with varying ionic strength with a constant osmolality (340 mmol/kg) maintained by adding mannitol. Solutions with a lower ionic strength induced larger calcium responses (Fig. 4A; see the dose-response plot on the right). However, ionic strength did not influence ACh-evoked responses from endogenous mAChRs in HEK cells transfected with RFP (Fig. 4A, control). To examine the contribution of osmolality, we stimulated ABCG1-transfected HEK cells with varying osmolality with a constant ionic strength. The peak amplitudes of the calcium responses were relatively insensitive to a change in the osmolality, and the response to ACh stimulation showed similar responses (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that a low ionic strength is the primary factor driving hypotonicity-induced calcium responses from ABCG1-transfected HEK cells through P2YRs, but not mAChRs.

Figure 4.

Ionic strength-evoked VRAC activity mediates hypotonicity-induced ATP release. A–D, stimulus-induced calcium responses were measured from ABCG1- or RFP (control)–transfected HEK cells with the calcium FLIPR assay. A, lower ionic strength induced larger calcium responses from ABCG1-transfected HEK cells but did not alter acetylcholine (ACh)–induced (final concentration, 100 μm) calcium responses of endogenous mAChR in RFP-transfected HEK cells (n = 4). Solutions with various ionic strengths maintain a constant osmolality (340 mmol/kg) with mannitol. B, solutions with various osmolalities were prepared while maintaining a constant ionic strength (final concentration, 113 mm). The osmolality solutions without and with ACh (final concentration, 100 μm) similarly induced calcium responses from ABCG1-transfected cells and HEK cells, respectively. Osmolality had no obvious effects on peak calcium responses (n = 4). C, hypotonic stimulation (final concentration, 250 mmol/kg) induced calcium responses (ΔF/F) from ABCG1-transfected HEK cells, which were decreased significantly by 1 h of preincubation with the VRAC inhibitor DCPIB (final concentration, 20 μm) but not with inhibitors of pannexin (final concentration, 2.5 mm probenecid), P2X7 receptor (final concentration, 5 μm A438079), connexin (final concentration, 1 mm heptanol), CALHM (final concentration, 20 μm ruthenium red (RuR)), and Maxi anion channel (final concentration, 50 μm Gd3+) (n = 4) (one-way ANOVA; F(6,21) = 31.97; p < 0.001). D, hypotonicity (final concentration, 250 mmol/kg)–induced peak calcium responses (ΔF/F) were measured in ABCG1-transfected HEK cells preincubated with various doses of DCPIB (IC50 = 10.2 ± 0.4 μm) (n = 8). E and F, ABCG1 does not alter LRRC8A expression. LRRC8A-deficient or control HEK cells were transfected transiently with RFP (control) or ABCG1. E, whereas the loss of LRRC8A protein was confirmed in LRRC8A-deficient HEK cells, ABCG1 transfection did not alter LRRC8A protein amount. The β-tubulin protein amount was unaltered under all conditions examined. F, ABCG1 transfection increased hypotonicity (final concentration, 250 mmol/kg)–induced ATP release in the control HEK cells, but not in the LRRC8A-deficient HEK cells (n = 8) (one-way ANOVA; F(2,21) = 55.78; p < 0.001). The data are means ± standard deviation (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test (C and F)). ***, p < 0.001. RLU, relative luminescent unit.

To identify the signaling pathway responsible for this effect, we stimulated ABCG1-transfected HEK cells with various molecules inhibiting potential pathways of ATP release. In these experiments, we found that hypotonicity-induced calcium responses were reduced by 20 μm DCPIB, a VRAC inhibitor, but unaltered by 2.5 mm probenecid (pannexin inhibitor), 20 μm ruthenium red (CALHM inhibitor), 50 μm gadolinium (Gd3+; Maxi anion channel inhibitor), 1 mm heptanol (connexin inhibitor), or 5 μm A438079 (P2X7 receptor inhibitor) (Fig. 4C). The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of DCPIB for hypotonicity-induced calcium responses in the ABCG1-expressing HEK cells was 10.2 ± 0.4 μm (Fig. 4D), which is similar to the IC50 for VRAC (24).

The sensitivity to low ionic strength and DCPIB indicates that VRAC mediates this hypotonicity-induced ATP release (24–26). To examine this directly, we knocked down LRRC8A, the gene encoding a critical VRAC constituent, in HEK cells using a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) published previously (19). LRRC8A protein levels were similar in control and ABCG1-transfected cells, indicating that ABCG1 does not affect VRAC expression, but markedly lower in shRNA-stably transfected ABCG1-expressing cells (Fig. 4E). Notably, hypotonicity-induced ATP release was abolished in LRRC8A shRNA-treated cells (Fig. 4F). These results strongly suggest that ABCG1 increases hypotonicity-induced ATP release through LRRC8A-containing VRACs.

ABC transporters regulate hypotonicity-induced ATP release through cholesterol modulation

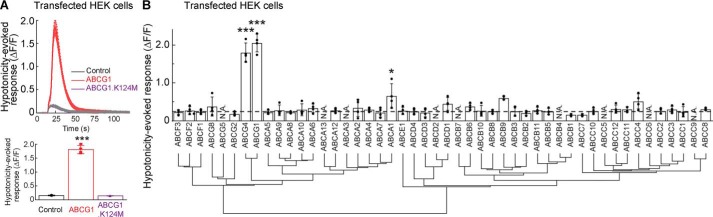

We next examined how ABCG1 modulates VRAC activity. ABCG1 is one of 48 ABC transporters, which typically use their ATPase activities to transport substrates (27). The ATPase activity of ABCG1 can be disrupted by a point mutation replacing the lysine residue at position 124 with methionine (K124M) (28). We measured hypotonicity-induced calcium responses in HEK cells expressing the ABCG1.K124M mutant using the calcium FLIPR assay. The hypotonicity-induced calcium response was abolished in HEK cells harboring the ABCG1.K124M mutant (Fig. 5A), suggesting that ATPase activity is required for VRAC modulation.

Figure 5.

Hypotonicity-induced purinergic signaling requires the ATPase activity of specific ATP transporters. Hypotonicity (final concentration, 250 mmol/kg)–induced calcium responses from HEK cells transfected transiently with ABC transporters, an ABCG1 mutant, or RFP (control) were measured with the calcium FLIPR assay. A, the ATPase activity of ABCG1 is required for hypotonicity-induced calcium responses. ABCG1, but not the ABCG1 mutant with a lysine-to-methionine substitution at position 124 (K124M) in the ABC, robustly increased hypotonicity-induced calcium responses (n = 4) (one-way ANOVA; F(2,9) = 501.7; p < 0.001). B, phylogenetic tree and hypotonicity-induced calcium responses of ABC transporters. Three ABC transporters (ABCG1, ABCG4, and ABCA1) among 39 ABC transporters increased the hypotonicity-induced calcium responses (n = 4) significantly relative to control (RFP). Eight ABC transporters were untested (N.A.). The dashed line indicates the response from RFP-transfected HEK cells (one-way ANOVA; F(39,120) = 35.04; p < 0.001). The data are means ± standard deviation (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test (A and B)). *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001.

To determine whether any other ABC transporters contribute to hypotonicity-induced ATP release, we re-evaluated 39 ABC transporter family proteins in the ORF collection with four replicates. Three ABC transporters (ABCG1, ABCG4, and ABCA1) induced significantly higher hypotonicity-induced calcium responses than RFP-transfected HEK cells (control) (Fig. 5B), supporting redundant modulatory functions among several ABC transporters in the hypotonicity-induced responses.

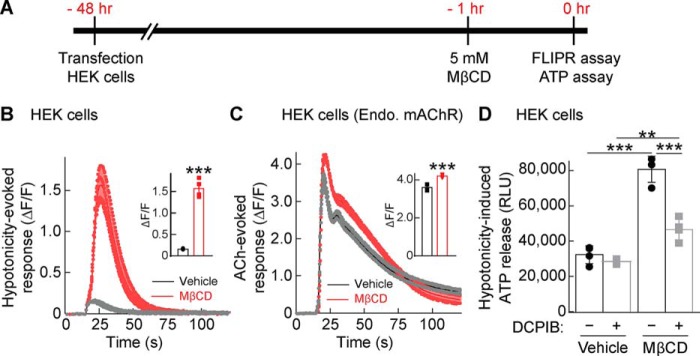

Because ABCG1 as well as ABCG4 and ABCA1 export cholesterol from intracellular compartments or the plasma membrane (29, 30), we postulated that these ABC transporters regulate ATP release and VRAC activity through cholesterol modulation. To test this, we treated RFP-expressing HEK cells with 5 mm methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) for 1 h, which is an established method to reduce cellular cholesterol (31). We confirmed that MβCD treatment reduced the fluorescent signal of filipin that recognizes cholesterol (Fig. S2, A and B). Then we measured hypotonicity-induced calcium responses with the calcium FLIPR assay (Fig. 6A). MβCD treatment enhanced hypotonicity-induced calcium responses (Fig. 6B) robustly compared with its effects on ACh-evoked calcium responses (Fig. 6C), suggesting that cholesterol depletion enhanced hypotonicity-induced responses more than Gq-coupled receptor signaling. Furthermore, we quantified ATP release from these HEK cells 30 s after hypotonic stimulation by using the luciferin–luciferase bioluminescence assay and found that cholesterol depletion via MβCD treatment enhanced the amount of ATP released into the medium (Fig. 6D). Moreover, this increased release was abolished by inhibiting VRAC activity with 20 μm DCPIB (Fig. 6D). The hypotonicity-induced ATP release was observed in a MβCD, presumably cholesterol dose–dependent manner (Fig. S3). These results demonstrated that hypotonicity-induced ATP release depends on cholesterol content and VRAC activity.

Figure 6.

Cholesterol depletion increases hypotonicity-induced ATP release. HEK cells were transfected with RFP; 48 h later, the cells were incubated with 5 mm MβCD or vehicle for 1 h and stimulated with hypotonic solution (final concentration, 250 mmol/kg) before the calcium response or ATP release was assayed. A, experimental overview. B and C, preincubation with MβCD robustly enhanced hypotonicity-induced calcium responses in HEK cells transfected with RFP (B), whereas MβCD enhanced the acetylcholine (ACh)–induced (100 μm) calcium response from endogenous mAChRs to a lesser extent (C). Traces and quantifications of peak calcium responses (ΔF/F) with error bars are shown (n = 4). D, ATP released into the extracellular medium upon hypotonic stimulation was measured with a luciferin–luciferase bioluminescence assay. MβCD enhanced hypotonicity-induced ATP release, and this enhancement was blocked by preincubation with 20 μm DCPIB (n = 4) (two-way ANOVA; F(1,12) = 146.3, p < 0.001 for MβCD comparison and F(1,12) = 48.12, p < 0.001 for DCPIB comparison; interaction; F(1,12) = 30.14, p < 0.001. The data are means ± standard deviation (unpaired t test (B and C) or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test (D)). ***, p < 0.001. RLU, relative luminescent unit.

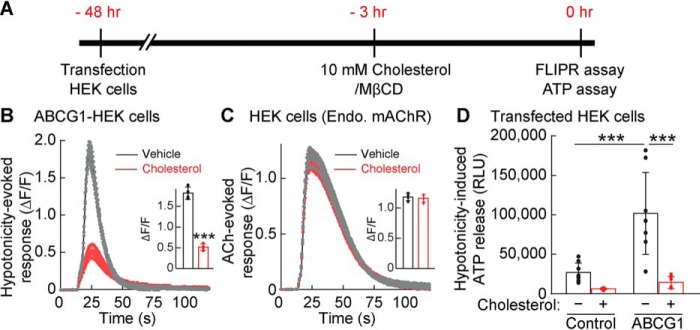

Cholesterol depletion and ABCG1 expression enhanced hypotonicity-induced ATP release and P2YR-mediated calcium signaling, supporting a model in which ABCG1 transports cholesterol from cells, which induces ATP release upon hypotonic stimulation through VRAC. If this is the case, cholesterol repletion should reduce ABCG1-dependent ATP release. To examine this, we assayed calcium responses and ATP release from ABCG1-expressing HEK cells incubated with a mixture of cholesterol and MβCD (Fig. 7A). Hypotonicity-induced calcium responses were significantly reduced in cells supplied with 10 mm cholesterol/MβCD (p < 0.001) (Fig. 7B), with no change in ACh-induced responses (Fig. 7C), suggesting that cholesterol repletion specifically inhibits hypotonicity-induced purinergic signaling. Accordingly, ABCG1 transfection increased hypotonicity-induced ATP release, which was abolished by cholesterol repletion (Fig. 7D). Further addition of cholesterol did not change the hypotonicity-induced ATP release (Fig. S3). Altogether, we concluded that hypotonicity-induced responses are sensitive to cellular cholesterol level, such that cholesterol depletion enhances hypotonicity-induced ATP release through VRAC activity.

Figure 7.

Cholesterol repletion inhibits ABCG1-dependent ATP release. HEK cells were transfected with ABCG1 or RFP; 48 h later, the cells were incubated with a mixture of 10 mm cholesterol/MβCD for cholesterol repletion or vehicle for 3 h and stimulated with hypotonic solution (final concentration, 250 mmol/kg) before the calcium response or ATP release was assayed. A, the experimental overview. B, cholesterol repletion suppressed hypotonicity-induced calcium responses from ABCG1-transfected HEK cells. Traces and quantifications of peak calcium responses (ΔF/F) with error bars are shown (n = 4). C, acetylcholine (ACh)–induced (final concentration, 100 μm) calcium responses from endogenous (Endo.) mAChRs were unaltered by cholesterol/MβCD treatment in the RFP-transfected HEK cells. Traces and quantifications of peak calcium responses (ΔF/F) with error bars are shown (n = 4). D, cholesterol repletion suppressed ABCG1-dependent ATP release. ABCG1 transfection increased hypotonicity-induced ATP release. Cholesterol repletion reduced extracellular ATP substantially in ABCG1-transfected HEK cells (n = 8) (two-way ANOVA; F(1,28) = 33.59; p < 0.001 for cholesterol comparison and F(1,28) = 18.25, p < 0.001 for ABCG1 comparison; interaction, F(1,28) = 11.56, p = 0.002). The data are means ± standard deviation (unpaired t test (B and C) and two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test (D)). ***, p < 0.001. RLU, relative luminescent unit.

Neurons release ATP by regulating VRAC activity through cholesterol modulation

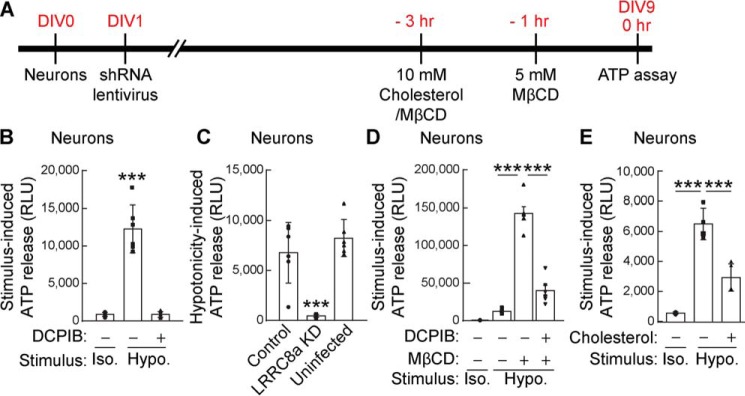

To validate the identified ATP release machinery, we returned to cerebellar granule neurons that exhibit hypotonicity-induced ATP release (Fig. 1A). For these experiments, we performed the luciferin–luciferase bioluminescence assay to measure ATP release from primary cerebellar granule neurons cultured for 9 days in vitro (Fig. 8A). The hypotonicity-induced ATP release was blocked by preincubating the neurons with 20 μm DCPIB, the VRAC inhibitor (Fig. 8B). Furthermore, lentivirus infection with shRNA for LRRC8A at day 1 in vitro similarly blocked the ATP release 30 s after stimulation with the hypotonic solution (Fig. 8C). These results indicate that, like HEK cells, cerebellar neurons utilize LRRC8A-containing VRACs for hypotonicity-induced ATP release.

Figure 8.

Neurons release ATP upon hypotonic stimulation through cholesterol-dependent VRAC. Primary cerebellar neurons were prepared, and extracellular ATP in the medium was measured 30 s after conditioned Hanks' balanced salt solution (isotonic 340 mmol/kg; Iso.) or hypotonic (final concentration, 250 mmol/kg; Hypo.) stimulation by using the luciferin–luciferase bioluminescence assay. A, experimental overview. B, hypotonic, but not isotonic, stimulation increased extracellular ATP in the neuronal medium, and DCPIB (20 μm) inhibited hypotonicity-induced ATP release (n = 8) (one-way ANOVA; F(2,15) = 74.61, p < 0.001). C, neuronal LRRC8A is required for hypotonicity-induced ATP release. Primary cerebellar neurons were infected with lentivirus carrying LRRC8A shRNA or random shRNA encoded in pFUGW-H1 (control). ATP release upon hypotonic stimulation was abolished in LRRC8A shRNA-infected neurons but was unaltered in uninfected neurons or neurons infected with a control virus (n = 6) (one-way ANOVA; F(2,15) = 24.29, p < 0.001). D, cholesterol depletion by preincubation of neurons with 5 mm MβCD robustly enhanced hypotonicity-induced ATP release, and this enhancement was blocked by the addition of 20 μm DCPIB (n = 8) (one-way ANOVA; F(3,20) = 131.2, p < 0.001). E, cholesterol repletion by preincubation of neurons with a mixture of 5 mm cholesterol with MβCD suppressed hypotonicity-induced ATP release (n = 4) (one-way ANOVA; F(2,9) = 55.95, p < 0.001). The data are means ± standard deviation (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test (B–E)). ***, p < 0.001. RLU, relative luminescent unit.

Hypotonicity-induced ATP release was magnified by depleting cholesterol from the cultured neurons via treatment for 1 h with 5 mm MβCD (Fig. 8D). Moreover, this enhancement was attenuated by incubating the neurons for 1 h with 20 μm DCPIB, confirming the contribution of VRAC activity to cholesterol-dependent ATP release. The hypotonicity-induced ATP release was also reduced in neurons preincubated with a mixture of 10 mm cholesterol and MβCD for 3 h (Fig. 8E). All of these results in neurons are consistent with what we observed in HEK cells, supporting the roles of cholesterol and VRAC in hypotonicity-induced ATP release.

Discussion

We utilized a genome-wide ORF collection for a GOF screen that identified ABC transporters as modulators of hypotonicity-induced ATP release. Further experiments demonstrated that ABC transporter activity modulates hypotonicity/ionic strength-induced ATP release through LRRC8A-containing VRACs by regulating cellular cholesterol levels. These findings reveal a novel ATP-dependent ATP release pathway for the modulation of extracellular ATP that triggers purinergic cellular signaling.

Genome-wide ORF collection

Our GOF screen with the genome-wide ORF collection covering 90% of nonredundant, human ORFs identified ABCG1, mGluR1, and mGluR5 as modulators of hypotonicity- and glutamate-induced purinergic calcium signaling (Fig. 2). Glutamate-induced calcium responses are observed in cells expressing ionotropic glutamate receptors or Gq-coupled mGluRs. However, fluorescence signals from calcium-sensitive dyes are easier to detect for mGluR activity, because calcium responses are transient from ionotropic receptors, which desensitize quickly upon glutamate application. There are only two known Gq-coupled mGluRs (23) that we identified in our screen, supporting its quality and sensitivity. With regard to the hypotonicity-induced response, the screen identified only ABCG1 as a robust modulator of ATP release.

The results from our GOF screen with the genome-wide ORF collection are compelling. However, there are caveats with this method. One such caveat involves the properties of the encoded proteins. In this screen, we transfected one plasmid/ORF in each well. Thus, genes that code for functional proteins are detectable. However, many proteins function as a complex with other proteins, which would be missed in this type of screen. For example, this study revealed that LRRC8A is an essential component for the hypotonicity-induced ATP release, but it was not detected by the GOF screen. One potential reason is that LRRC8A functions as a heteromer with LRRC8B–F (19, 20), and LRRC8A overexpression by itself does not increase overall VRAC activity (19, 20). Another example pertains to the cholesterol transporters, ABCG5 and ABCG8. We tested 39 ABC transporters and found 3 that enhanced hypotonicity-induced purinergic signaling (Fig. 5B). However, it remains unclear whether the negative 36 transporters play any role in regulating ATP release in vivo. Because ABCG5 and ABCG8 require heteromerization to be a functional transporter (32, 33), it is unlikely that expression of either transporter alone reconstitutes its transporter activity in transfected cells. Thus, a multigene expression system could be helpful in the future, although it is currently infeasible, because a combination of only 2 genes would involve 361 million pairs (19,224 genes times 19,224 genes). Nevertheless, these potential combinations could be narrowed down by incorporating expression patterns. Another caveat involves the quality of the ORFs. We have been collecting ORFs from the OriGene transmembrane protein collection and the ORF collection from the Broad Institute (22) since 2009 and custom cloning in the laboratory. These ORFs are cloned into vectors with a cytomegalovirus promoter and likely to be expressed in transfected HEK cells. However, the expression of all ORFs has not been confirmed. It will be cost-effective to generate one human ORF collection with validated expression and to expand the collection with various splice isoforms.

Molecular signaling for ATP release

Our screen identified ABC transporters as modulators of ATP release through LRRC8A-containing VRAC in both nonpolarized cells and polarized neurons. Some ABC transporters are expressed in polarized epithelial cells, so we also examined hypotonicity-induced ATP release from MDCK cells, a frequently used model cell line for polarized epithelial cells. We did not detect significant ATP release from untreated or cholesterol-depleted MDCK cells in response to hypotonicity (Fig. S4). Because our proposed machinery of hypotonicity-induced ATP releases requires LRRC8A downstream of ABC transporters (ABCG1/ABCG4/ABCA1) and cholesterol, this result suggests the lower activity of LRRC8A in MDCK cells. ABC transporter-like ion channel, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator/ABCC7, p-glycoprotein/multidrug-resistant protein 1/ABCB1, and other ABC transporters were previously shown to regulate ATP release (34–36), but there is evidence against the ABC transporter as a pore for ATP release (5, 6). There are currently two models: (i) ATP transporters by themselves excrete ATP from cells and (ii) ATP transporters modulate some factors that regulate ATP release.

With regard to the first model, the high-resolution structures of ABC transporters and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (37, 38) suggest that these proteins do not support ATP permeation, because the pockets are too small for ATP. However, there may be accessory proteins that change the structures of the transporters substantially. As evidence supporting the second model, we showed that ATP transporter ABCG1 modulates ATP release via the regulation of the cellular cholesterol level and VRAC activity. Recent evidence suggests that VRAC itself is capable of gating its channel activity in response to hypotonicity/lowered ionic strength (37, 38). Further, as stated above, several ABC transporters, including ABCG1, can export cholesterol from the cell (29, 30). Thus, it is reasonable to consider this machinery as a general modulator of ATP release that may be implicated in disease. For example, human patients or mice with elevated cholesterol levels might have altered VRAC-dependent ATP release and purinergic signaling and consequently may have defects in pain sensation or other disorders. Future analyses of ABC transporters and cellular cholesterol levels in association with human disease status will help determine this.

We showed that hypotonicity-induced ATP release requires the ATPase activity of ABCG1. This result supports the critical role of ABCG1 transporter activity in modulating ATP release through VRAC, whose activity depends on intracellular ATP (39, 40). However, other studies showed that low-hydrolyzable ATP is sufficient to permit VRAC activity (41, 42). Because ATP hydrolysis is required for the ATPase activity of ABCG1, additional studies are needed to clarify how nonhydrolyzable ATP modulates VRAC activity.

ATP-permeable pore and its regulation

Our results suggest that, under hypotonic conditions, ATP is released through LRRC8-containing VRACs. Moreover, this release is enhanced by cholesterol depletion. Typically, the osmolality of hypotonic solution is ∼200 mmol/kg that is substantially lower than isotonic solution ∼330 mmol/kg. It remains unclear whether such a robust reduction in osmolality occurs in the brain in vivo. However, under the ABCG1-expressing condition, just a 6% osmolality difference between the hypotonic stimulus and the assay solution induced VRAC activity (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, we found that altering the ionic strength of the extracellular solution induced VRAC activation (Fig. 4A). At physiological ionic strength (170 mm), VRAC shows low activity. With the expression of ABCG1 or cholesterol depletion, a 5 mm difference in ionic strength is sufficient to induce a 20% difference in VRAC activity. Importantly, cholesterol depletion by itself does not activate VRAC. Perhaps cholesterol plays a critical role in regulating VRAC activity under physiological conditions with small changes in ion concentration.

The mechanism(s) by which cholesterol depletion induces the release of ATP through LRRC8A-containing VRACs is not known. Interestingly, the structure of the LRRC8A homomer shows electron density at the pore, which may indicate some type of lipid (43–46). Our findings suggest that this lipid could be cholesterol. Under normal conditions, cholesterol could plug or narrow the pore diameter, and only small molecules, such as ions, can pass through, such as observed upon ionic activation of LRRC8A channels reconstituted in liposomes (25). However, under cholesterol-depleted conditions, the cholesterol may be removed from the pore, enabling larger molecules to permeate. Consistent with this, we showed that restoration of the depleted cholesterol substantially reduced ATP release through LRRC8A-containing VRACs. It is possible that VRAC activity is dysregulated under high-cholesterol conditions, inducing an imbalance in the homeostasis of VRAC-permeable molecules in human disorders. Further studies of the relationships between cholesterol and VRAC substrates may provide insights into such human disorders.

In summary, the results of this study show that ABCG1 activity modulates hypotonicity-induced ATP release through VRACs in a cholesterol level-dependent manner. Further studies are needed to confirm these data and to clarify the mechanism by which ABCG1 regulates VRAC permeability.

Experimental procedures

Animals

All animal handling was in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Yale University. Animal care and housing were provided by the Yale Animal Resource Center, in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., 1996). The animals were maintained in a 12-h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. WT (C57BL/6J, stock no. 000664) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Sample sizes were estimated by previous studies. Both male and female animals were used.

Cell lines

HEK-293 (CRL-1573) cells obtained from ATCC were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in Advanced Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 4% dialyzed FBS, penicillin-streptomycin, and GlutaMAX. 293FT cells for lentivirus generation were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 0.1 mm minimal essential medium nonessential amino acids, 2 mm glutamine, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, penicillin/streptomycin, and 500 μg/ml G418.

Primary cultured cerebellar granule neurons

Primary cultured cerebellar granule neurons were prepared as described previously (47). Briefly, cerebella were dissected from P7 mice and treated with trypsin, and the cells were seeded on poly-d-lysine–coated 384-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well and grown in medium with cytosine arabinoside to suppress growth of non-neuronal cells in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. All experiments were performed at day 9 in vitro.

Building genome-wide ORF collection

Mammalian ORFs were obtained from the CCSB-Broad ORFeome lentiviral expression collection (15,743 ORFs; pLX304), CCSB-Broad gateway collection (23,644 ORFs, pENTR221/223), and OriGene transmembrane cDNA collection (3,896 ORFs, pCMV6). To assemble the genome-wide ORF collection, 13,192 nonredundant ORFs from the CCSB-Broad lentiviral expression collection were supplemented with 817 nonredundant ORFs from the OriGene transmembrane cDNA collection. An additional 3,274 nonredundant ORFs from the CCSB-Broad gateway collection were subcloned into pCDNA3.1-v5 using LR Clonase II and sequenced with T7 primer.

Plasmid transfection

Plasmid was introduced into cells by reverse transfection, unless otherwise noted. Briefly, the cells were plated in a well with a mixture of transfection reagent (FuGENE 6; Promega) and plasmid. The cells were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2 to allow for gene expression.

Calcium FLIPR assay

The cells were washed with an assay buffer (1× Hanks' balanced salt solution with calcium, magnesium, 2.5 mm probenecid, and 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4) using a Versette liquid handler (Thermo Scientific). The cells were then loaded with calcium-4 FLIPR dye (Molecular Devices) in the assay buffer and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. The calcium FLIPR assay was performed using a FLIPRTETRA System (Molecular Devices). Solution osmolality was confirmed with a vapor pressure osmometer (Vapro, model5520).

ATP detection

The cells were washed once and then incubated in the assay buffer for 1 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Stimulation and media collection before and after stimulation were performed using a Versette liquid handler (ThermoScientific). Extracellular ATP levels were measured using a luciferin–luciferase bioluminescence assay (ATP determination kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a bioluminescence plate reader (GloMax; Promega).

Cholesterol modification

Cholesterol free modification was performed using established, cyclodextrin-based methods (31). The cells were washed with serum-free medium and then incubated with either serum-free medium containing 5 mm methyl-β-cyclodextrin (Sigma) for 1 h or serum-free medium containing cholesterol (Sigma) as 10 mm cholesterol mixed with methyl-β-cyclodextrin for 3 h.

Generation of LRRC8a shRNA stable cell line

HEK cells were transfected with LRRC8a shRNA construct in pFUGW-H1 (Addgene: no. 25870) (48), and stable cell lines were established by isolating individual Zeocin-resistant (200 μg/ml) colonies. The shRNA target sequence, GGUACAACCACAUCGCCUA, was previously described (19).

Generation of lentivirus carrying each shRNA

Lentivirus was generated as previously described (49). Briefly, 293FT cells were transfected with plasmids psPAX2 (gift from Didier Trono (Addgene plasmid 12260)), pVSVg (50) and LRRC8a-shRNA in pFUGW-H1 using a calcium–phosphate transfection method. After 40–44 h, the cell medium was collected, filtered, and centrifuged (120,000 × g for 1.5 h at 4 °C). The pellet was resuspended in PBS, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C until use.

Western blotting

HEK cells were washed with a TE buffer of 20 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA once, incubated with 1% SDS in the TE buffer, and sonicated briefly. Protein concentration was measured using a BCA assay (Pierce) and adjusted to 0.5 mg/ml. Same protein amount was loaded on SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and then detected with anti-LRRC8a (Bethyl Labs, rabbit, 1:5000) or anti-β-tubulin (Sigma, rabbit, 1:10,000) antibodies.

Molecular biology

ABCG1 ABC (K124M) mutant construct was generated using a QuikChange mutagenesis (Stratagene) protocol with mutagenic primers: ABCG1 K124M, mutagenic, forward: GGGGCCGGGATGTCCACGCTG; and

ABCG1 K124M, mutagenic, reverse: CAGCGTGGACATCCCGGCCCC. The mutations were verified by Sanger sequencing.

ABC-family phylogenetic tree

Reference human protein sequences for each member of the ABC family were obtained from the UniProt database and then used to generate a protein alignment (ClustalW) and phylogenetic tree (Jukes-Cantor, UPGMA, no outgroup) with Geneious6 software (Biomatters).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Quantification and statistics are detailed in the figure legends. Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software). All data are given as means ± standard deviation. Data normality was confirmed using the Shapiro–Wilkes test. Then statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post test, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post, or unpaired t test as required by experimental design. In two-way ANOVA analyses, p values from Tukey's post hoc tests were shown for comparisons between data groups with differences in one experimental factor.

Author contributions

P. J. D., E. J. S., and S. T. resources; P. J. D. data curation; P. J. D. and E. J. S. software; P. J. D. formal analysis; P. J. D. validation; P. J. D. and S. T. investigation; P. J. D. visualization; P. J. D. and E. J. S. methodology; P. J. D. and S. T. writing-original draft; E. J. S. and S. T. writing-review and editing; S. T. conceptualization; S. T. supervision; S. T. funding acquisition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. David Zenisek, Fred Sigworth, Shawn Ferguson, Yasuko Iwakiri, Richard Kibby, Megan King, Michael V. L. Bennett, and the members of the Tomita lab for fruitful discussions and advice. We thank Addgene and OriGene for the plasmids listed under “Experimental procedures.”

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants RC1 NS068966 from NINDS and U01 MH104984 from NIMH; the NIGMS, National Institutes of Health Predoctoral Pharmacology Training Program Grant T32-GM007324 (to P. J. D.); National Institutes of Health Cellular and Molecular Biology Training Grant T32-GM007223; National Institutes of Health Neurobiology of Cortical Systems Training Grant T32-GNS007224 (to E. J. S.); and funds from Yale University (to S. T.), the Gruber Foundation, and the Kavli Foundation. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1–S4.

- P2YR

- P2Y receptor

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- VRAC

- volume-regulated anion channel

- shRNA

- short hairpin RNA

- LOF

- loss-of-function

- GOF

- gain-of-function

- ABC

- ATP-binding cassette

- mAChR

- muscarinic-type acetylcholine receptor

- MβCD

- methyl-β-cyclodextrin

- CALHM

- calcium homeostasis modulator

- PLC

- phospholipase C

- DCPIB

- 4-[(2-Butyl-6,7-dichloro-2-cyclopentyl-2,3-dihydro-1-oxo-1H-inden-5-yl)oxy]butanoic acid.

References

- 1. Burnstock G. (2014) Purinergic signalling: from discovery to current developments. Exp. Physiol. 99, 16–34 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.071951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brake A. J., and Julius D. (1996) Signaling by extracellular nucleotides. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12, 519–541 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. North R. A., and Barnard E. A. (1997) Nucleotide receptors. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 7, 346–357 10.1016/S0959-4388(97)80062-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Melani A., Turchi D., Vannucchi M. G., Cipriani S., Gianfriddo M., and Pedata F. (2005) ATP extracellular concentrations are increased in the rat striatum during in vivo ischemia. Neurochem. Int. 47, 442–448 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Okada Y., Okada T., Islam M. R., and Sabirov R. Z. (2018) Molecular identities and ATP release activities of two types of volume-regulatory anion channels, VSOR and Maxi-Cl. Curr. Top. Membr. 81, 125–176 10.1016/bs.ctm.2018.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taruno A. (2018) ATP release channels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, E808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vitiello L., Gorini S., Rosano G., and la Sala A. (2012) Immunoregulation through extracellular nucleotides. Blood 120, 511–518 10.1182/blood-2012-01-406496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lazarowski E. R. (2012) Vesicular and conductive mechanisms of nucleotide release. Purinergic Signal. 8, 359–373 10.1007/s11302-012-9304-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoffmann E. K., Lambert I. H., and Pedersen S. F. (2009) Physiology of cell volume regulation in vertebrates. Physiol. Rev. 89, 193–277 10.1152/physrev.00037.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jentsch T. J. (2016) VRACs and other ion channels and transporters in the regulation of cell volume and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 293–307 10.1038/nrm.2016.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Osei-Owusu J., Yang J., Vitery M. D. C., and Qiu Z. (2018) Molecular biology and physiology of volume-regulated anion channel (VRAC). Curr. Top. Membr. 81, 177–203 10.1016/bs.ctm.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Strange K., Yamada T., and Denton J. S. (2019) A 30-year journey from volume-regulated anion currents to molecular structure of the LRRC8 channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 151, 100–117 10.1085/jgp.201812138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ma Z., Tanis J. E., Taruno A., and Foskett J. K. (2016) Calcium homeostasis modulator (CALHM) ion channels. Pflugers Archiv. 468, 395–403 10.1007/s00424-015-1757-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bao L., Locovei S., and Dahl G. (2004) Pannexin membrane channels are mechanosensitive conduits for ATP. FEBS Lett. 572, 65–68 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bennett M. V., Garré J. M., Orellana J. A., Bukauskas F. F., Nedergaard M., and Sáez J. C. (2012) Connexin and pannexin hemichannels in inflammatory responses of glia and neurons. Brain Res. 1487, 3–15 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.08.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Velázquez B., Garrad R. C., Weisman G. A., and González F. A. (2000) Differential agonist-induced desensitization of P2Y2 nucleotide receptors by ATP and UTP. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 206, 75–89 10.1023/A:1007091127392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sabirov R. Z., Merzlyak P. G., Okada T., Islam M. R., Uramoto H., Mori T., Makino Y., Matsuura H., Xie Y., and Okada Y. (2017) The organic anion transporter SLCO2A1 constitutes the core component of the Maxi-Cl channel. EMBO J. 36, 3309–3324 10.15252/embj.201796685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gaitán-Peñas H., Gradogna A., Laparra-Cuervo L., Solsona C., Fernández-Dueñas V., Barrallo-Gimeno A., Ciruela F., Lakadamyali M., Pusch M., and Estévez R. (2016) Investigation of LRRC8-mediated volume-regulated anion currents in Xenopus oocytes. Biophys. J. 111, 1429–1443 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Qiu Z., Dubin A. E., Mathur J., Tu B., Reddy K., Miraglia L. J., Reinhardt J., Orth A. P., and Patapoutian A. (2014) SWELL1, a plasma membrane protein, is an essential component of volume-regulated anion channel. Cell 157, 447–458 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Voss F. K., Ullrich F., Münch J., Lazarow K., Lutter D., Mah N., Andrade-Navarro M. A., von Kries J. P., Stauber T., and Jentsch T. J. (2014) Identification of LRRC8 heteromers as an essential component of the volume-regulated anion channel VRAC. Science 344, 634–638 10.1126/science.1252826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yates B., Braschi B., Gray K. A., Seal R. L., Tweedie S., and Bruford E. A. (2017) Genenames.org: the HGNC and VGNC resources in 2017. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D619–D625 10.1093/nar/gkw1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. ORFeome Collaboration (2016) The ORFeome Collaboration: a genome-scale human ORF-clone resource. Nat. Methods 13, 191–192 10.1038/nmeth.3776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nakanishi S. (1992) Molecular diversity of glutamate receptors and implications for brain function. Science 258, 597–603 10.1126/science.1329206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Decher N., Lang H. J., Nilius B., Brüggemann A., Busch A. E., and Steinmeyer K. (2001) DCPIB is a novel selective blocker of I(Cl,swell) and prevents swelling-induced shortening of guinea-pig atrial action potential duration. Br. J. Pharmacol. 134, 1467–1479 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Syeda R., Qiu Z., Dubin A. E., Murthy S. E., Florendo M. N., Mason D. E., Mathur J., Cahalan S. M., Peters E. C., Montal M., and Patapoutian A. (2016) LRRC8 proteins form volume-regulated anion channels that sense ionic strength. Cell 164, 499–511 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Voets T., Droogmans G., Raskin G., Eggermont J., and Nilius B. (1999) Reduced intracellular ionic strength as the initial trigger for activation of endothelial volume-regulated anion channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 5298–5303 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moitra K., and Dean M. (2011) Evolution of ABC transporters by gene duplication and their role in human disease. Biol. Chem. 392, 29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cserepes J., Szentpétery Z., Seres L., Ozvegy-Laczka C., Langmann T., Schmitz G., Glavinas H., Klein I., Homolya L., Váradi A., Sarkadi B., and Elkind N. B. (2004) Functional expression and characterization of the human ABCG1 and ABCG4 proteins: indications for heterodimerization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 320, 860–867 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Velamakanni S., Wei S. L., Janvilisri T., and van Veen H. W. (2007) ABCG transporters: structure, substrate specificities and physiological roles: a brief overview. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 39, 465–471 10.1007/s10863-007-9122-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Woodward O. M., Köttgen A., and Köttgen M. (2011) ABCG transporters and disease. FEBS J. 278, 3215–3225 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08171.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zidovetzki R., and Levitan I. (2007) Use of cyclodextrins to manipulate plasma membrane cholesterol content: evidence, misconceptions and control strategies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1768, 1311–1324 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Graf G. A., Li W. P., Gerard R. D., Gelissen I., White A., Cohen J. C., and Hobbs H. H. (2002) Coexpression of ATP-binding cassette proteins ABCG5 and ABCG8 permits their transport to the apical surface. J. Clin. Invest. 110, 659–669 10.1172/JCI0216000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Graf G. A., Yu L., Li W. P., Gerard R., Tuma P. L., Cohen J. C., and Hobbs H. H. (2003) ABCG5 and ABCG8 are obligate heterodimers for protein trafficking and biliary cholesterol excretion. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 48275–48282 10.1074/jbc.M310223200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abraham E. H., Prat A. G., Gerweck L., Seneveratne T., Arceci R. J., Kramer R., Guidotti G., and Cantiello H. F. (1993) The multidrug resistance (mdr1) gene product functions as an ATP channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 312–316 10.1073/pnas.90.1.312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reisin I. L., Prat A. G., Abraham E. H., Amara J. F., Gregory R. J., Ausiello D. A., and Cantiello H. F. (1994) The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is a dual ATP and chloride channel. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 20584–20591 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schwiebert E. M. (1999) ABC transporter-facilitated ATP conductive transport. Am. J. Physiol. 276, C1–C8 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.1.C1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu F., Zhang Z., Csanády L., Gadsby D. C., and Chen J. (2017) Molecular structure of the human CFTR ion channel. Cell 169, 85–95.e8 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang Z., and Chen J. (2016) Atomic structure of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Cell 167, 1586–1597.e9 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Banderali U., and Roy G. (1992) Activation of K+ and Cl− channels in MDCK cells during volume regulation in hypotonic media. J. Membr. Biol. 126, 219–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nilius B., Eggermont J., Voets T., Buyse G., Manolopoulos V., and Droogmans G. (1997) Properties of volume-regulated anion channels in mammalian cells. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 68, 69–119 10.1016/S0079-6107(97)00021-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jackson P. S., Morrison R., and Strange K. (1994) The volume-sensitive organic osmolyte-anion channel VSOAC is regulated by nonhydrolytic ATP binding. Am. J. Physiol. 267, C1203–C1209 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.5.C1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Oike M., Droogmans G., and Nilius B. (1994) The volume-activated chloride current in human endothelial cells depends on intracellular ATP. Pflugers Arch. 427, 184–186 10.1007/BF00585960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Deneka D., Sawicka M., Lam A. K. M., Paulino C., and Dutzler R. (2018) Structure of a volume-regulated anion channel of the LRRC8 family. Nature 558, 254–259 10.1038/s41586-018-0134-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kasuya G., Nakane T., Yokoyama T., Jia Y., Inoue M., Watanabe K., Nakamura R., Nishizawa T., Kusakizako T., Tsutsumi A., Yanagisawa H., Dohmae N., Hattori M., Ichijo H., Yan Z., et al. (2018) Cryo-EM structures of the human volume-regulated anion channel LRRC8. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 797–804 10.1038/s41594-018-0109-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kefauver J. M., Saotome K., Dubin A. E., Pallesen J., Cottrell C. A., Cahalan S. M., Qiu Z., Hong G., Crowley C. S., Whitwam T., Lee W. H., Ward A. B., and Patapoutian A. (2018) Structure of the human volume regulated anion channel. eLife 7, e38461 10.7554/eLife.38461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kern D. M., Oh S., Hite R. K., and Brohawn S. G. (2019) Cryo-EM structures of the DCPIB-inhibited volume-regulated anion channel LRRC8A in lipid nanodiscs. eLife 8, e42636 10.7554/eLife.42636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Martenson J. S., Yamasaki T., Chaudhury N. H., Albrecht D., and Tomita S. (2017) Assembly rules for GABAA receptor complexes in the brain. eLife 6, e27443 10.7554/eLife.27443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fasano C. A., Dimos J. T., Ivanova N. B., Lowry N., Lemischka I. R., and Temple S. (2007) shRNA knockdown of Bmi-1 reveals a critical role for p21-Rb pathway in NSC self-renewal during development. Cell Stem Cell 1, 87–99 10.1016/j.stem.2007.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang W., St-Gelais F., Grabner C. P., Trinidad J. C., Sumioka A., Morimoto-Tomita M., Kim K. S., Straub C., Burlingame A. L., Howe J. R., and Tomita S. (2009) A transmembrane accessory subunit that modulates kainate-type glutamate receptors. Neuron 61, 385–396 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stewart S. A., Dykxhoorn D. M., Palliser D., Mizuno H., Yu E. Y., An D. S., Sabatini D. M., Chen I. S., Hahn W. C., Sharp P. A., Weinberg R. A., and Novina C. D. (2003) Lentivirus-delivered stable gene silencing by RNAi in primary cells. RNA 9, 493–501 10.1261/rna.2192803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.