Abstract

Introduction

Development of a support system for families caring for people with schizophrenia in routine psychiatric care settings is an important issue worldwide. Regional mental health systems are inadequate for delivering effective services to such family members. Despite evidence that family psychoeducation (FPE) alleviates the burden of schizophrenia on families, its dissemination in routine clinical practice remains insufficient, suggesting the need for developing an effective and implementable intervention for family caregivers in the existing mental health system setting. In Japan, the visiting nurse service system would be a practical way of providing family services. Visiting nurses in local communities are involved in the everyday lives of people with schizophrenia and their families. Accordingly, visiting nurses understand their needs and are able to provide family support as a service covered by national health insurance. The purpose of this study is to discover whether a brief FPE programme provided by visiting nurses caring for people with schizophrenia will alleviate family burden through a cluster randomised controlled trial (cRCT).

Methods and analysis

The study will be a two-arm, parallel-group (visiting nurse agency) cRCT. Forty-seven visiting nurse agencies will be randomly allocated to the brief FPE group (intervention group) or treatment as usual group (control group). Caregivers of people with schizophrenia will be recruited by visiting nurses using a randomly ordered list. The primary outcome will be caregiver burden, measured using the Japanese version of Zarit Burden Interview. Outcome assessments will be conducted at baseline, 1-month follow-up and 6-month follow-up. Multiple levels of three-way interactions in mixed models will be used to examine whether the brief FPE programme will alleviate the burden on caregivers relative to treatment as usual.

Ethics and dissemination

The Research Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine and Faculty of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Japan (No 2019065NI) approved this study. The results will be published in a scientific peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

UMIN000038044.

Keywords: brief family psychoeducation, schizophrenia, caregivers, visiting nurses

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will evaluate an implementable brief family psychoeducation (FPE) programme that potentially reduces time, cost and staffing problems by incorporating the programme into an existing mental health service system, namely visiting nurse services.

The study incorporated a variety of viewpoints from caregivers, visiting nurses and FPE experts based on the concept of coproduction and patient and public involvement.

One study limitation is that all outcomes will be based on self-reports, which may cause information bias or random error.

Introduction

Families caring for people with schizophrenia receiving community-based mental healthcare have a great need for support. People with schizophrenia who have severe symptoms require long-term care, which imposes a significant burden on families providing such care.1 For example, the financial burden on the family is severe because considerable amounts of time are devoted to caregiving, resulting in the loss of work opportunities and reduced income.2 Moreover, insufficient downtime to recover from the stress of caregiving results in both physical and mental illnesses.3 Families also become worn out and stressed by the demands of coping with this illness, which is characterised by repeated hallucinations and delusions if symptoms do not stabilise.4 Furthermore, a parent of a son or daughter with schizophrenia might worry about what will become of their child after his or her death. They might also feel they are not getting adequate information about what social services are available to them.5 Stigma against the illness is also deeply rooted and can lead to families becoming socially isolated.3 Therefore, families of people with schizophrenia have various physical, psychological, economic and social burdens.

Several studies have addressed the development and evaluation of effective family interventions. According to a systematic review, family psychoeducation (FPE) is a scientifically effective psychological intervention that has been used to reduce caregiver burden.6 7 The components of FPE mainly include sharing information about the disorder, early warning signs, relapse prevention, as well as skills training in coping, communication and problem solving.8 FPE can directly improve caregivers’ knowledge about schizophrenia and related caregiving problems.9 Improved knowledge of coping strategies and resources can lead to a more positive appraisal of caregiving experiences by families as well as caregivers’ own self-efficacy in coping with the demands of caring for people with schizophrenia, thereby lessening the burden.6

Despite the accumulation of evidence, there are several barriers to FPE implementation. The initial report on the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team treatment recommendations found that FPE was provided to 31.6% of inpatients and 9.6% of outpatients who could have benefited from it.10 A nationwide survey in Japan revealed that the implementation rate for FPE programmes at psychiatric facilities is similarly low: 35.9% in hospitals and 14.5% in outpatient settings.11 One challenge in implementing these programmes is the length of the intervention. Most studies have found that such interventions range from 9 months to 2 years, which is impractical for medical staff and families in a clinical setting.12 Other reasons include funding and staff shortages, as well as providing necessary training.13 In Japan, even if healthcare professionals perform FPE for a family, they cannot obtain reimbursement for medical expenses. In addition, while the Meriden Family Programme appears to be effective, training is time consuming and expensive.14 The medical treatment fee system in most countries including Japan does not cover such a comprehensive family intervention. The development of a brief and implementable FPE programme within the existing mental health system that is covered by national health insurance is greatly needed.15

Brief FPE programmes have been examined in previous studies. In terms of the programme framework, studies have found that brief FPE programmes, delivered in five sessions or fewer or lasting no more than 3 months, were easy to conduct for both practitioners and caregivers.16 Brief FPE programmes have been shown to significantly increase caregivers’ knowledge of the disorder, leading to reductions in relapse and rehospitalisation rates in diverse settings.17 18 In addition, recent research has shown that a brief FPE programme may be beneficial in reducing caregiver burden. In a pre-post test in India, a brief FPE programme comprised three 1-hour sessions aimed at educating the primary caregiver and the patient about schizophrenia and imparting communication and problem-solving skills. A significant decrease in caregiver burden, measured using the Burden Assessment Scale, was found between baseline and the final follow-up at 3 months.19 In a randomised controlled trial in Iran, brief FPE consisted of ten 90 min sessions held over 5 weeks (two sessions each week) conducted by a psychiatric nurse or psychiatrist. Caregiver burden measured using the Family Burden Scale was significantly reduced both immediately after the intervention and 1 month later.20 However, the effects of brief FPE programmes are still inconclusive due to relatively low methodological quality in prior studies.7 16 In other words, evidence from a trial with a better design is needed.

Practical implementation strategies for a brief FPE programme need to be considered in addition to a scientific evaluation of the effects. Brief FPE programmes provided by visiting nurses appear to be a potentially feasible and sustainable way of implementing FPE in a Japanese clinical setting. Visiting nurses routinely visit clients with schizophrenia and their family members. They have already built rapport with clients and family members and would be able to respond according to their needs, which means they could seamlessly provide highly individualised brief FPE.21 In addition, the system of visiting nurses could easily be applied because the number of visiting nurses has been increasing recently in Japan. From a cost perspective, it would be possible to make family support a reimbursable service under national health insurance to cover psychiatric visiting nurse consultancy fees.22 Taken together, brief FPE provided by visiting nurses could overcome the poor implementation rate and become effective family interventions in the community setting in Japan.

Hypothesis and aims

We hypothesise that brief FPE provided by visiting nurses could alleviate the burden on families and caregivers of people with schizophrenia. The aim of this study is to clarify whether visiting nurses providing brief FPE to families caring for people with schizophrenia alleviates family burden through a cluster randomised controlled trial (cRCT).

Methods and analysis

Trial design

This study is a two-arm, parallel-group cRCT. The randomisation procedure will be conducted at the cluster level (visiting nurse agencies). Visiting nurse agencies will be randomly assigned to the intervention or control (treatment as usual) group in a 1:1 ratio. Data will be collected at the individual level. Analyses to evaluate the efficacy of the intervention programme will be conducted at the individual level, taking into consideration cluster-level effects. The study protocol was registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry. This protocol has been reported according to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials guidelines.23 The anticipated trial start date will be 18 September 2019 and the date of last follow-up will be 31 May 2020.

Setting and site selection at the cluster level

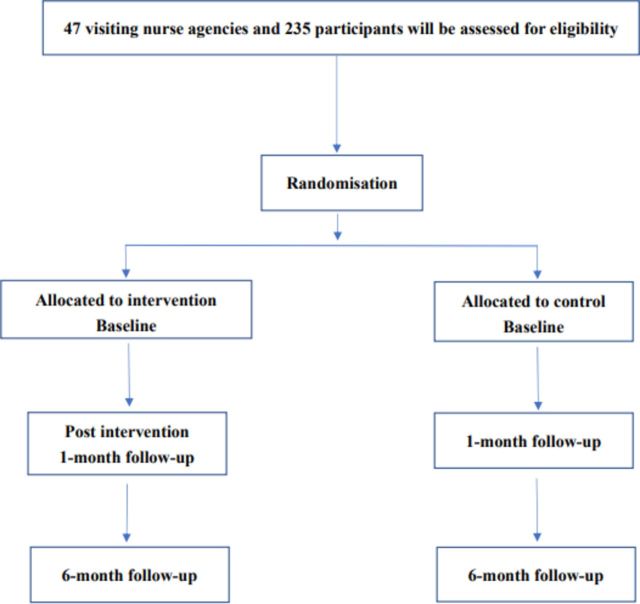

Figure 1 shows the participant flow chart for this study. The corresponding author (NY) explained the purpose of this study to 68 visiting nurse agencies in four prefectures in Japan (Tokyo, Saitama, Kanagawa and Chiba) through the organisation. Forty-seven visiting nurse agencies agreed to participate in the study. All the participating visiting nurse agencies are managed by one organisation.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

To be included, a visiting nurse agency must provide services mostly to psychiatric patients or clients, not elderly people or those with physical diseases. In each agency, visiting nurses must care for at least two people with schizophrenia who live with their family. There are no exclusion criteria at the cluster level.

Randomisation at the cluster level

Visiting nurse agencies that meet the inclusion criteria will be randomly allocated to the intervention group (brief FPE programme) or the control group. Randomisation will be stratified by the median of the average case load of visiting nurses in each agency. We used stratified randomisation based on this factor because the number of patients for whom a visiting nurse can maintain service quality is generally fixed.24 If a visiting nurse has too many patients, family support will probably be neglected. A random sequence table will be created by a researcher (HT) in another department at our institution who is not involved in the study protocol development process. In addition, another independent researcher (SY) who is not involved in intervention and analysis will conduct the randomisation and will inform each visiting nurse agency of the randomisation results. The primary investigator (NY) will be blinded through the entire randomisation process.

Participant eligibility criteria and recruitment procedure at the individual level

At the individual level, we set the following inclusion criteria for a caregiver of a person with schizophrenia: (1) is the primary caregiver; (2) aged over 20 years; (3) is a family member of the person with schizophrenia such as a parent, sibling, spouse or child; and (4) lives with the person with schizophrenia. There are no exclusion criteria for caregivers. In addition, the inclusion criteria for people with schizophrenia are as follows: (1) diagnosis of schizophrenia based on the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision and (2) receiving services from visiting nurses.

As part of the recruitment procedure at the individual level, all potential participants (caregivers of people with schizophrenia and people with schizophrenia) at each agency will be listed. Second, a randomly ordered list will be created using a random number generator in the Stata statistical software programme V.15, in order to avoid selection bias at the individual level. Third, each visiting nurse, after attending a lecture on study design and ethical considerations, will recruit participants in accordance with the randomly ordered list until five participants have been recruited. The study will include only participants who voluntarily agree to participate in the study.

Intervention programme

The intervention programme consists of a single-family intervention conducted by psychiatric visiting nurses. It is based on the Family Intervention and Support in Schizophrenia: A Manual on Family Intervention for the Mental Health Professional.25 This programme was developed through discussions and collaborations among members of the Family Association of Schizophrenia, psychiatric visiting nurses, FPE experts, psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, clinical psychologists and mental health social workers based on the concept of coproduction and patient and public involvement (PPI).26 During the development process, we tried to avoid long sentences, enlarged the characters and used visually appealing drawings. The programme consists of four sessions that last 60 min each using the above tool. It will be completed over a period of a month. Attendance of at least one session is required. Using this intervention tool, psychiatric visiting nurses will provide appropriate information and advice to the family about living problems based on their own nursing clinical experience. We will also create a checklist to confirm how many sessions visiting nurses are actually able to conduct with participants.

Before the intervention, we will provide the intervention team of psychiatric visiting nurses with a 1-day lecture. The lecture will consist of three parts. First, caregivers will talk about their life problems and what they want visiting nurses to do; this is expected to increase the motivation of visiting nurses. Second, basic communication training will be conducted through role-playing. Visiting nurses, who will be brief FPE providers, will be in groups of three. They will each play the role of a visiting nurse, caregiver and evaluator. They will practise listening to caregivers. Third, the primary investigator (NY) will equip them with basic knowledge about FPE and explain the contents of this intervention tool and the points that the primary investigator wants to emphasise. Through these trainings, we expect to improve the motivation, knowledge and skills of the visiting nurses in providing the brief FPE programme.

Table 1 shows the contents of the intervention tool. Session I will cover general knowledge about schizophrenia: definition, causes, symptoms, prognosis, pharmacological treatment and psychosocial rehabilitation. Regarding definition and causes, visiting nurses will stress that schizophrenia is a brain disease that can manifest in anyone using the diathesis-stress model and the dopamine hypothesis. It is important to provide the family with a biological explanation about the aetiology of schizophrenia because there might be family members who think people become schizophrenic because of family relationships.27 In addition to an explanation of the symptoms themselves, visiting nurses will describe how people with schizophrenia have difficulties living their own lives due to their symptoms. Visiting nurses will explain the disease course such as the prodromal phase, acute phase and recovery phase. Next, visiting nurses will explain the characteristics of each phase and what to do during each phase. In terms of prognosis, visiting nurses will emphasise that schizophrenia is not necessarily a disease with a bad prognosis. In people with their first episode of schizophrenia, about 70% will have a good intermediate to long-term outcome if they receive appropriate pharmacological therapy.28Concerning medication, visiting nurses will appreciate the idea that people with schizophrenia usually do not want to take medication. Visiting nurses will talk about the necessity, safety and reasons for adherence to pharmacological therapy. In addition, the side effects of antipsychotic medications will be described clearly, using relevant pictures. Finally, visiting nurses will give an outline of psychosocial therapy. At the end, participants will answer questions with dichotomous answers—‘yes’ or ‘no’—to confirm what they have learnt from the session.

Table 1.

Outline of the brief family psychoeducation programme

| Session No | Session aim | Content |

| I | General knowledge about schizophrenia | Definition, causes, symptoms, prognosis, pharmacological treatment, psychosocial rehabilitation. Activity: Let’s review the knowledge gained in this session. |

| II | How to cope with people with schizophrenia using problem-solving skills | How to cope with hallucinations and delusions; signs of recurrence and how to prevent recurrence; how to cope when the disease gets worse; what to do with people with schizophrenia when they stay at home all day; how to respond to people with schizophrenia who do not want to take their medication; what to do when domestic violence is imminent, is happening or has happened; how to get involved when self-injury or suicide is suspected. Activity: Let’s learn how to apply problem-solving skills. |

| III | Handling communication and emotions | Understanding the feelings of people with schizophrenia, expressed emotion theory, basic knowledge about communication and lecture about desirable and undesirable communication with people with schizophrenia. Activity: Let’s practise conversations using real cases. |

| IV | Family recovery | Thinking about the family’s recovery, importance of living one’s own life, taking care of the family’s physical and mental health needs, proper stress management, and experiences and messages from members of the Family Association. Activity: Let’s identify social resources in the community and recognise the importance of connecting with many supporters around families. |

This intervention programme consists of four 60 min modules completed over 1 month.

Session II will deal with how to cope with people with schizophrenia and provide problem-solving skills. The contents of this session include how to cope with hallucinations and delusions; signs of recurrence; how to prevent recurrences; how to cope when the disease gets worse; what to do with people with schizophrenia when they stay at home all day; how to respond to people with schizophrenia who do not want to take their medication; how to respond when domestic violence is imminent, is occurring or has occurred; and how to get involved when self-injury or suicide is suspected. Finally, visiting nurses will explain problem-solving skills. In a routine clinical setting, the family will work on matters that are causing trouble in daily life using problem-solving skills.

Session III will cover communication and emotions: understanding the feelings of people with schizophrenia, expressed emotion (EE) theory, basic knowledge and skills about communication, and a lecture on desirable and undesirable communication with people with schizophrenia. In the first section, visiting nurses will describe the importance of understanding that people with schizophrenia are likely to have a pessimistic view about their future. In the second section on EE theory, visiting nurses will appreciate that it is natural for a family to have high EE, poor knowledge and lack of support for mental illness.29 Of note, visiting nurses will not force family members to play the role of supporter. When family members hear the explanation of high EE, many might feel that they are responsible for their burden. Visiting nurses will emphasise that both families and people with schizophrenia should think about positive and constructive communication to ensure mutual independence. In the third section on basic knowledge about communication and the lecture of desirable and undesirable communication with patients, caregivers will practise conversations using real cases and will be given time to consider better communication strategies.

Session IV will focus on the family’s recovery. Topics will include thinking about the family’s recovery, the importance of living one’s own life, taking care of the family’s physical and mental health needs, proper stress management, experiences and messages from members of the Family Association and identifying available social resources in the community. During this session, visiting nurses will stress that people with schizophrenia and family members each have their own lifestyle and individual goals. Visiting nurses will also encourage family members to live their own lives using a variety of social resources instead of only working hard to take care of a person with schizophrenia. In addition, visiting nurses expect that family members will improve their physical and mental health by acquiring knowledge on self-care and stress management skills. Furthermore, visiting nurses will introduce the experiences of three members of the Family Association who have taken care of a person with schizophrenia. It is expected that others’ similar experiences will help family members understand that they are not the only people experiencing such a hard time and relieve their feelings of sadness or hopelessness. Finally, visiting nurses will explain the social resources available in the community for family members and confirm the importance of connecting with many supporters around them.

Control group

Caregivers enrolled in the control group will receive usual care from visiting nurses. They will be put on a waiting list to receive the same intervention programme after completing the 6-month follow-up assessment. They will not receive any type of psychoeducation or supportive therapies.

Outcomes

Table 2 shows an overview of the outcome measures. Outcome measures will be assessed at baseline prior to the intervention (T1), immediately after the completion of the intervention (1-month follow-up, T2) and 6 months after the baseline assessment (6-month follow-up, T3).

Table 2.

Outcome measures

| Outcome measure | Baseline | 1-month follow-up | 6-month follow-up | |

| Caregivers | Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-22) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| WHO-5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Knowledge of Illness and Drug Inventory (KIDI) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| People with schizophrenia | Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-32) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| WHO-5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Hospitalisation during the past 6 months | ✓ | – | ✓ |

Primary outcome for caregivers

Zarit Burden Interview

Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-22) will be used to measure caregiver burden. It consists of 22 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (nearly always), except for the final item on global burden, which is rated from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The total score ranges from 0 to 88, with higher scores indicating higher burden. The Japanese version of ZBI-22 has high test–retest reproducibility and internal consistency. Construct validity has also been confirmed.30

Secondary outcome for caregivers

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6) will be used to measure subclinical depression and anxiety disorders as part of a self-administered questionnaire. It consists of six items answered on a 5-point Likert scale. Scores range from 0 to 24, with higher scores representing higher degrees of subclinical depression and anxiety disorder. The Japanese versions have essentially equivalent screening performance as the original English versions.31

General Self-Efficacy Scale

General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) is a measurement of self-efficacy in daily living. It includes 16 items with dichotomous questions. The higher the score, the better the self-efficacy, in general. GSES has high test–retest reproducibility and internal consistency. Construct validity has been confirmed.32

WHO-5

WHO-5 will be used to measure subjective quality of life based on positive mood (good spirits and relaxation), vitality (being active and waking up fresh and rested) and general interest (being interested in things). It consists of five items rated on a 6-point Likert scale. Higher scores mean higher well-being. The Japanese version of WHO-5 has adequate internal consistency. It has been confirmed to have external concurrent validity and external discriminatory validity.33

Knowledge of Illness and Drug Inventory

Knowledge of Illness and Drug Inventory (KIDI) will be used to assess knowledge regarding mental illness and the effects of medications on mental illness. There are two subscales: 10 items assessing knowledge of mental illness and 10 items assessing knowledge of the effects of antipsychotic drugs. This inventory consists of a self-reported inventory where respondents are asked to select the correct answer from three choices, with higher scores representing greater knowledge. KIDI is frequently used to assess knowledge about mental disorders and treatments in Japan.34

Secondary outcomes in people with schizophrenia

Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale

Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-32) is a commonly used measure in mental health. It includes 32 items on a 5-point Likert scale, where 0 indicates no difficulties and 4 indicates severe difficulties. The scale measures five factors: (1) relation to self and others (seven items); (2) depression/anxiety (six items); (3) everyday life and role functioning (nine items); (4) impulsive and addictive behaviour (six items); and (5) psychosis (four items). Factors 1, 2, 4 and 5 are assessed as the total score divided by the number of items answered (mean score). Factor 3 is assessed based on the highest rating. Internal consistency and construct validity of the Japanese version of BASIS-32 have been demonstrated.35

WHO-5

WHO-5 is used to measure subjective quality of life based on positive mood (good spirits and relaxation), vitality (being active and waking up fresh and rested) and general interest (being interested in things). WHO-5 comprises five items rated on a 6-point Likert scale. Higher scores mean higher well-being. The Japanese version of WHO-5 has adequate internal consistency. It has been confirmed to have external concurrent validity and external discriminatory validity.33

Hospitalisation by 6-month follow-up

This is a question with a dichotomous answer (yes or no) about whether the patient has been hospitalised during the past 6 months. The answer will be provided by the caregiver at baseline and the 6-month follow-up.

Sample size calculation

The sample size required was calculated according to guidelines in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) for cRCTs,36 taking into account intraclass correlations (ICC). The effect size of a brief FPE programme for individual caregiver burden was estimated based on a previous pre-post test.19 The pre-post test concluded that the standardised mean difference (d) of brief FPE on family burden was 0.46. Sample size was estimated as 76 in each arm based on an alpha error probability of 0.05 and power (1-β) of 0.80, using G*Power V.3.1.9.2.37 38 For cRCTs, this value should be multiplied by design effect (1+[m−1]ρ), where m is the average cluster size and ρ is the ICC.39 The estimated ICC for the primary outcome in this study was set to 0.05 and the average number of caregivers per cluster was set at 5. Assuming an attrition rate of 20%, the required sample size is 110 caregivers in each arm. Thus, at least 44 visiting nurse agencies will be recruited.

Quantitative analysis

The statistician will be blinded to the treatment group. We will analyse clinical outcomes on the basis of intention to treat and model the effect of the intervention on primary and secondary continuous outcomes using generalised linear latent and mixed models. This will allow for missing data to be taken into account within the statistical model. In this study, a three-level model will be used, with repeated measures nested in participants and participants nested in clusters. Time (baseline, 1-month follow-up, 6-month follow-up) will be considered level 1, individual caregivers will be considered level 2 and clusters (visiting nurse agencies) will be considered level 3. Regarding fixed effects, condition (intervention vs control), time, and a two-way interaction effect, condition by time, will be included. Models will adjust for baseline differences in caregiver sociodemographics such as age, gender, education, household income, family relationship with the person with schizophrenia, length of caregiving and length of visiting nurse system use. Multiple levels of Cox proportional hazards regression models will also be used for the dichotomous question of hospitalisation at the 6-month follow-up. A p value <0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Data monitoring

A data monitoring committee (DMC) will be set up. It will consist of at least two independent members. The DMC will meet monthly after the first participant has been randomised. The purpose of the meeting will be to review participation rates and reasons for study dropout. The DMC will be independent from any sponsor and competing interest.

Patient and public involvement

The research question, study design and outcome measures were determined based on a discussion with representatives of the Family Association of Schizophrenia. The intervention programme was developed through discussion and collaboration among members of the Family Association of Schizophrenia, psychiatric visiting nurses, FPE experts, psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, clinical psychologists and mental health social workers. After the completion of the study, this intervention tool will be available for anyone who wants to use it via the internet.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical considerations

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine and the Faculty of Medicine at The University of Tokyo, Japan (No 2019065NI). We will obtain informed consent from all caregivers and patients. The consent form will inform caregivers and patients that we guarantee protection of personal information and that the data will be anonymous and used only for academic purposes. There are no competing interests. This study is supported by the fundamental study on effective community services for people with severe mental disorders and their families.

Dissemination of the research findings

The findings will be published in a scientific peer-reviewed journal according to the CONSORT guidelines for cRCTs.36 The participants will be informed of conference presentations and publications.

Strengths and limitations

The study has both strengths and limitations. First, the study will evaluate an implementable brief FPE programme that potentially reduces time, cost and staffing problems by incorporating the programme into an existing mental health service system, namely visiting nurse services. Second, this is the first cRCT of a brief FPE programme, which could prevent contamination between the intervention and control groups. Third, based on the concept of coproduction and PPI,26 the study incorporated a variety of viewpoints from caregivers, visiting nurses and FPE experts.

We recognise three limitations of this study. First, since the sampling method for participating agencies was not random, there is a possibility of selection bias. Second, since subjects will provide data through a self-reported questionnaire, information bias or random error is possible. For example, the severity of symptoms in people with schizophrenia that impact a caregiver’s burden may not be accurately measured. Third, we designed the study and intervention based on coproduction, but there are still concerns about its feasibility in actual clinical settings. For example, participants might not complete all four sessions due to the condition of people with schizophrenia, family work and family hospitalisation. Fourth, due to the short study period, the number of participants may not be able to meet the target sample size. These may lead to a high attrition rate during implementation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the Mokusei Family Association of Schizophrenia and N・FIELD CO., Ltd. for their invaluable advice on many aspects of the project.

Footnotes

Contributors: NY is the principal investigator responsible for the initial draft of this manuscript and organising and implementing the study. NY and KW calculated the sample size. NY, KW, SY and AM decided on the analytical strategy. SS, TS, HT, KI, DN, CF and NK helped throughout the development of the interventions and gave valuable feedback on the study protocol. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by the fundamental study on effective community services for people with severe mental disorders and their families.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Research Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine and the Faculty of Medicine at The University of Tokyo, Japan.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Awad AG, Voruganti LNP. The burden of schizophrenia on caregivers: a review. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:149–62. 10.2165/00019053-200826020-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saunders JC. Families living with severe mental illness: a literature review. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2003;24:175–98. 10.1080/01612840305301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah AJ, Wadoo O, Latoo J. Psychological distress in carers of people with mental disorders. British Journal of Medical Practitioners 2010;3:a327. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gopinath PS, Chaturvedi SK. Distressing behaviour of schizophrenics at home. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992;86:185–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb03249.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McAuliffe R, O'Connor L, Meagher D. Parents' experience of living with and caring for an adult son or daughter with schizophrenia at home in Ireland: a qualitative study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2014;21:145–53. 10.1111/jpm.12065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sin J, Gillard S, Spain D, et al. Effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions for family carers of people with psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2017;56:13–24. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sin J, Jordan CD, Barley EA, et al. Psychoeducation for siblings of people with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;5:Cd010540. 10.1002/14651858.CD010540.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, et al. Evidence-Based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:903–10. 10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birchwood M, Smith J, Cochrane R. Specific and non-specific effects of educational intervention for families living with schizophrenia. A comparison of three methods. Br J Psychiatry 1992;160:806–14. 10.1192/bjp.160.6.806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the schizophrenia patient outcomes research team (Port) client survey. Schizophr Bull 1998;24:11–20. discussion 20–32. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oshima I, Mino Y, Nakamura Y, et al. Implementation and dissemination of family psychoeducation in Japan: nationwide survey on psychiatric hospitals in 1995 and 2001. Journal of Social Policy & Social Work 2007;11:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rummel-Kluge C, Kissling W. Psychoeducation in schizophrenia: new developments and approaches in the field. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2008;21:168–72. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f4e574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey C. Family psychoeducation for people living with schizophrenia and their families. BJPsych Adv 2018;24:9–19. 10.1192/bja.2017.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fadden G, Heelis R. The Meriden family programme: lessons learned over 10 years. J Ment Health 2011;20:79–88. 10.3109/09638237.2010.492413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McFarlane WR, Dixon L, Lukens E, et al. Family psychoeducation and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. J Marital Fam Ther 2003;29:223–45. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01202.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okpokoro U, Adams CE, Sampson S. Family intervention (brief) for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;3:Cd009802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitschel-Walz G, Leucht S, Bäuml J, et al. The effect of family interventions on relapse and rehospitalization in schizophrenia--a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull 2001;27:73–92. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith JV, Birchwood MJ. Specific and non-specific effects of educational intervention with families living with a schizophrenic relative. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:645–52. 10.1192/bjp.150.5.645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devaramane V, Pai NB, Vella S-L. The effect of a brief family intervention on primary carer's functioning and their schizophrenic relatives levels of psychopathology in India. Asian J Psychiatr 2011;4:183–7. 10.1016/j.ajp.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharif F, Shaygan M, Mani A. Effect of a psycho-educational intervention for family members on caregiver burdens and psychiatric symptoms in patients with schizophrenia in Shiraz, Iran. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:48. 10.1186/1471-244X-12-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang X-Y, Ma W-F, Shih H-H, et al. Roles and functions of community mental health nurses caring for people with schizophrenia in Taiwan. J Clin Nurs 2008;17:3030–40. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02426.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Setoya N, Kayama M, Tsunoda A, et al. A survey of the family care provided in psychiatric home-visit nursing and related characteristics of clients. Japanese Bulletin of Social Psychiatry 2011;20:17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. Spirit 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake RE, et al. Models of community care for severe mental illness: a review of research on case management. Schizophr Bull 1998;24:37–74. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varghese M, Shah A, Kumar GSU, et al. Family intervention and support in schizophrenia: a manual on family intervention for the mental health professional, version 2. Bangalore, India: National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Batalden M, Batalden P, Margolis P, et al. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:509–17. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferriter M, Huband N. Experiences of parents with a son or daughter suffering from schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2003;10:552–60. 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00624.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Menezes NM, Arenovich T, Zipursky RB. A systematic review of longitudinal outcome studies of first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med 2006;36:1349–62. 10.1017/S0033291706007951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amaresha AC, Venkatasubramanian G. Expressed emotion in schizophrenia: an overview. Indian J Psychol Med 2012;34:12–20. 10.4103/0253-7176.96149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arai Y, Kudo K, Hosokawa T, et al. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Zarit caregiver burden interview. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1997;51:281–7. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1997.tb03199.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakurai K, Nishi A, Kondo K, et al. Screening performance of K6/K10 and other screening instruments for mood and anxiety disorders in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2011;65:434–41. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02236.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakano Y, Tohjoh M. The general self-efficacy scale (GSES): scale development and validation. Japanese Journal of Behavior Therapy 1986;12:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Awata S, Bech P, Yoshida S, et al. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the world health Organization-Five well-being index in the context of detecting depression in diabetic patients. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007;61:112–9. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01619.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maeda M, Renri T OM, et al. It is as a result of disease drug knowledge degree investigation (knowledge of illness and drugs inventory, KIDI) for a person with IIB-29 schizophrenia and the family. Japanese Bulletin of Social Psychiatry 1994;2:173–4. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Setoya Y NY, Kurita H. Utility of the Japanese version of the BASIS-32 in inpatients in psychiatric hospital. Japanese Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2002;31:571–5. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, et al. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2012;345:e5661. 10.1136/bmj.e5661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, et al. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 2009;41:1149–60. 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, et al. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91. 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, et al. Consort statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2004;328:702–8. 10.1136/bmj.328.7441.702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.