Abstract

Tankyrase 1 (TNKS1; PARP-5a) and Tankyrase 2 (TNKS2; PARP-5b) are poly-ADP-ribosyl-polymerase (PARP)-domain-containing proteins that regulate the activities of a wide repertoire of target proteins via post-translational addition of poly-ADP-ribose polymers (PARylation). Although tankyrases were first identified as regulators of human telomere elongation, important and expansive roles of tankyrase activity have recently emerged in the development and maintenance of stem cell states. Herein, we summarize the current state of knowledge of the various tankyrase-mediated activities that may promote human naïve and ‘extended’ pluripotency’. We review the putative role of tankyrase and PARP inhibition in trophectoderm specification, telomere elongation, DNA repair and chromosomal segregation, metabolism, and PTEN-mediated apoptosis. Importantly, tankyrases possess PARP-independent activities that include regulation of MDC1-associated DNA repair by homologous recombination (HR) and autophagy/pexophagy, which is an essential mechanism of protein synthesis in the preimplantation embryo. Additionally, tankyrases auto-regulate themselves via auto-PARylation which augments their cellular protein levels and potentiates their non-PARP tankyrase functions. We propose that these non-PARP-related activities of tankyrase proteins may further independently affect both naïve and extended pluripotency via mechanisms that remain undetermined. We broadly outline a hypothetical framework for how inclusion of a tankyrase/PARP inhibitor in small molecule cocktails may stabilize and potentiate naïve and extended pluripotency via pleiotropic routes and mechanisms.

INTRODUCTION

The pluripotent naïve epiblast undergoes a dynamic series of epigenomic, transcriptomic, and metabolic re-configurations during peri-implantation embryonic development. These transitions comprise a continuum of functionally distinct pluripotent stem cell states [1]. The core signaling pathways that orchestrate these transitions can be manipulated experimentally with small molecules and cytokines that stably capture naïve epiblast-like pluripotency, and possibly more primitive stem cell states (e.g., with capacities for generating both embryonic and extra-embryonic lineages). The LIF/STAT3 and BMP4/SMAD signaling pathways stimulate the growth of murine embryonic stem cells (mESC) in heterogeneous states that maintain characteristics of the rodent preimplantation naïve inner cell mass (ICM) [2–5]. In contrast, conventional human embryonic stem cells (hESC) derived from human preimplantation blastocyst-derived ICM, as well as reprogrammed human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSC), both employ FGF2/MEK/ERK signaling to stabilize a lineage-primed pluripotent state that is distinct from the murine and human naïve epiblast. This primed pluripotency resembles the molecular and epigenetic status of murine post-implantation epiblast-derived stem cells (EpiSC), which possess a more restricted functional pluripotency than the naïve epiblast [1, 6].

The discovery of the LIF-2i (i.e., LIF + MEK inhibitor + GSK3β inhibitor) culture system established that self-renewal of a naïve mESC ‘ground state’ required both a blockade of the MEK/ERK signaling and a reinforcement of β-catenin signaling [7]. However, the murine LIF-2i system alone was not sufficient to stabilize human pluripotent stem cells (hPSC) in a murine-equivalent naïve pluripotent ground state [1]. Instead, a series of independent studies reported that various complex culture systems (some of which partially incorporated the murine LIF-2i system) achieved pluripotent states that shared molecular traits of the human pre-implantation epiblast [1]. These studies primarily employed transgenic or chemical methods to sustain naïve mESC-like pluripotent states. Overall, these approaches established that defined common core molecular pathways may converge via various, and perhaps redundant routes to sustain naïve pluripotency in both rodents and humans.

For example, several diverse naïve pluripotency rewiring methods have employed activation of STAT3 signaling [8, 9], ectopic expression of NANOG or Kruppel-like factors [10–12], global erasure of epigenetic repressive marks (e.g., through histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition [13, 14]), activation of distinct signaling pathways (e.g., adenyl-cyclase, Hippo) [12, 15], and biochemical alterations of the balance between cell cycle and differentiation (e.g., p38, SRC, PKC inhibitions) [10, 11, 16–18]. However, some of these methods inadvertently generated genomic and epigenomic aberrations [14, 17, 19] similar to those reported in mESC following prolonged exposure to MEK inhibition [20]. The ultimate sequelae of these chemically-reverted human naïve states on their functional pluripotency (including efficacy of directed differentiation and chimera formation) currently remain unclear.

In contrast to these important studies, Zimmerlin et al. reported an alternative naïve reversion method that supplemented the classical LIF-2i chemical cocktail with an inhibitor of the poly-ADP-ribosylating enzymes tankyrase 1 and 2 (PARP5a/5b, ARTDF5/6) (i.e., XAV939) [8, 21, 22]. Supplementation of XAV939 per se to LIF-2i (i.e., LIF-3i) was sufficient to stably maintain conventional human pluripotent stem cells (hPSC) in a naïve epiblast-like state with improved functionality and without epigenomic aberrations. The method consisted of two culture steps for long-term naïve-reversion of conventional hPSC: 1) a brief adaptation culture step consisting of LIF and 5 small molecules (LIF-5i) that included XAV939 (tankyrase inhibition), CHiR99021 (GSK3β inhibition), PD0325901 (MEK inhibition), forskolin (adenylate cyclase activation), and purmorphamine (Hedgehog signaling activation); followed by 2) continued culture of LIF-5i-adapted hPSC in only LIF-3i medium (i.e., XAV939/CHIR99021/PD0325901) that stably maintained a human naïve state for at least 30 passages. The LIF-5i-> LIF-3i protocol (aka ‘the LIF-3i method’) was applied successfully on over 30 genetically independent conventional, lineage-primed hESC and hiPSC lines for reversion to a stable human naïve epiblast-like pluripotent state [8, 21, 22].

Although XAV939 has been widely employed as a small molecule WNT inhibitor when used alone, the LIF-3i method accentuated several other studies that also demonstrated that when used simultaneously with GSK-3β inhibition, XAV939 induced a stabilization of AXIN isoforms that enhanced self-renewal of both conventional human pluripotent stem cells and murine EpiSC. The mechanism of action was shown to be XAV939 synergizing with GSK-3β inhibition, to paradoxically augment canonical WNT signaling by reinforcing the stability of the active isoform of β-catenin in both cytoplasmic and nuclear subcellular compartments. However, unlike these previous studies, Zimmerlin et al, exploited this dual use of GSK-3β/tankyrase/PARP co-inhibition along with simultaneous (PD0325901) MEK inhibition to stably revert a wide repertoire of conventional hPSC to a naïve epiblast-like state without requirement for exogeneous FGF2. LIF-5i -> LIF-3i-reverted naïve hPSC (N-hPSC) re-activated naïve epiblast-like STAT3 signaling, and possessed naïve epiblast-like globally hypomethylated genomes, but without hypomethylated genomic imprinting aberrations [8, 21, 22]. N-hPSC were functionally competent for multi-lineage differentiation without need for an additional ‘capacitation’ step or re-culture back to primed state (i.e., ‘re-priming’). Moreover, these studies not only validated the functional pluripotency of reverted N-hPSC in multi-lineage directed differentiation assays, but also revealed that N-hPSC possessed significantly improved differentiation efficiencies relative to their isogenic primed, conventional hPSC counterparts.

Here, we review the current state of knowledge of the pleiotropic effects mediated by tankyrases, and outline their putative roles for stabilizing human naïve pluripotency. The mechanism of tankyrase/PARP inhibition-mediated stabilization of pluripotency remains incompletely understood, and we propose that it likely involves a broad modulation of tankyrase protein function beyond WNT signaling. For example, several groups recently reported that incorporation of tankyrase or PARP inhibition into culture conditions enhanced murine blastocyst chimerism and potentiated an expanded pluripotency with capacity for extra-embryonic differentiation. Furthermore, the tankyrase PARylome includes a repertoire of master regulatory factors that may independently impact naïve epiblast self-renewal, including PTEN, DICER, and the Hippo signaling pathway. Tankyrases also exert PARP domain-independent regulation of homologous recombination-mediated double strand DNA break repair and autophagy [23–25]. Thus, tankyrases may play broader roles in stabilizing pluripotency beyond their PARylation activity.

Simultaneous tankyrase and GSK-3β inhibition augments self-renewal and extends the developmental functionality of established pluripotent states.

An important role of PARylation in embryonic development was first revealed from observations that uncontrolled accumulation of poly-ADP-ribose resulted in early embryonic lethality [26]. The role of PARylation in modulating WNT signaling was subsequently investigated in pluripotency and cancer cell survival studies. XAV939 was first identified as an inhibitor of WNT signaling by its capacity to stimulate β-catenin degradation via antagonism of the PARylation activity of tankyrases [27]. The sole use of XAV939 inhibited WNT signaling in cancer cells by stabilizing AXIN, a tankyrase target, and reinforcing the β-catenin destruction complex [27]. XAV939 binds to a conserved subsite within the nicotinamide pocket in the PARP domain binding groove of tankyrases, but also PARP1 and PARP2 [28]. Some tankyrase inhibitors (i.e., IWR-1, IWR-2) are more selective to tankyrases since they bind instead the adenosine subsite of the catalytic domain of tankyrases [29, 30].

However, several groups utilized XAV939-mediated PARP inhibition to stabilize alternative human and rodent pluripotent states by combining it directly with GSK-3β small molecule co-inhibition [8, 31–34]. The dual combination of tankyrase inhibition (XAV939) and GSK-3β inhibition (CHIR99021) in primed rodent mEpiSC and primed, conventional hESC paradoxically increased WNT signaling by increasing AXIN expression (XAV939) while simultaneously stabilizing the AXIN-catenin complex (CHIR99021), which augmented cytoplasmic retention of the active non-phosphorylated isoform of β-catenin in both nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments [33]. Zimmerlin et al subsequently reported the LIF-3i system, which for the first time utilized XAV939/CHIR99021 co-inhibition along with simultaneous MEK inhibition [8]. These studies demonstrated that in the absence of MEK/ERK signaling (i.e., PD0325901 inhibition), synergistic XAV939/GSK-3β co-inhibition stabilized naïve epiblast-like hPSC self-renewal.

Based on the observation that LIF-3i-reverted hPSC cultures were more amenable to directed lineage differentiation independent of genetic background, Park et al recently expanded the application of tankyrase inhibitor-regulated N-hiPSC by testing their capacity for repairing ischemia-damaged tissue in a pre-clinical humanized animal model of ischemic retinopathy [22]. In these studies, conventional hiPSC were episomally-reprogrammed from skin fibroblasts of type-I diabetic patients, and subsequently chemically-reverted to naïve hiPSC (N-hiPSC) using the LIF5i -> LIF-3i method [8, 21, 22].. Vascular progenitors (VP) differentiated from diabetic N-hiPSC demonstrated significantly improved vascular functionality in paired comparisons with isogenic primed diabetic hiPSC-derived VP. For example, normal and diabetic N-hPSCderived VP possessed superior self-renewal and proliferation, and reduced senescence and sensitivity to DNA damage. More importantly, diabetic N-hiPSC-derived VP demonstrated enhanced survival and long-term engraftment within the injured ischemic retina [22].

In other studies, PARP inhibition along with GSK-3β co-inhibition (CHIR99021) was employed as a component of small molecule cocktails that potentiated increased incorporation of extraembryonic lineages from murine, human and porcine stem cells into chimeric embryos and fetuses [31, 32, 34]. PARP1 inhibition (with small molecules other than XAV939) along with co-inhibition with GSK-3β inhibition (CHIR99021) and LIF augmented the capacity of murine pluripotent stem cells to contribute to both embryonic and trophectoderm lineages in chimeric murine fetuses [31]. In this study, additional inhibition of tankyrase-mediated PARylation (i.e., with IWR-1-endo) converted conventional human PSC into “extended human pluripotent stem (EPS) cells” [31]. However, unlike Zimmerlin et al’s LIF-3i system, this study did not additionally include a MEK/ERK inhibitor to sustain a naïve pluripotent state, and thus the developmental and epigenomic status of these novel extended pluripotency hPSC remains unclear [31].

Interestingly, Yang et al developed a chemical cocktail similar to LIF-3i that included XAV939 along with LIF, GSK-3β and MEK co-inhibition that augmented the capacity of murine blastomeres to self-renew, and allowed the derivation of stem cells capable of extra-embryonic differentiation potency that they termed expanded potential stem cells (EPSC) [32]. Murine EPSC contributed not only to embryonic lineages, but also to trophectoderm lineages in chimera assays, including the in vitro generation of trophoblast stem cells (TSC) and extra-embryonic endoderm (XEN) cells [32]. The same group reported protocols to derive human and porcine EPSC [34]. Interestingly, unlike murine EPSC, the human/pig methods omitted MEK inhibition, and these human and porcine EPSC states, and unlike murine EPSC which had transcriptional profiles similar to LIF-2i ground state mESC, these human EPSC appeared to possess a primed (non-naïve epiblast) epigenome, while maintaining trophectoderm lineage differentiation capacity [34]. Collectively, these studies suggested that inhibition of PARP enzymatic activity (especially tankyrase-mediated PARylation) may regulate multiple cellular processes that stabilize both naïve and primed pluripotent states in the embryo while also potentiating an expanded functional pluripotency. Interestingly, other human pluripotent stem cell studies recently employed sole XAV939 inhibition without simultaneous GSK-3β co-inhibition (i.e., used as a WNT inhibitor), to rescue the functionality of a human naïve state prior to reversion [14] or differentiation [35] in a process they termed ‘capacitation’. The mechanism of sole WNT inhibition with XAV9393 per se in this capacitation system, and how it relates to the LIF-3i system and to murine EPSC systems (which both simultaneously employ tankyrase/GSK3β co-inhibition along with simultaneous MEK inhibition) requires further investigation.

Tankyrases are redundant post-translational modifiers with a diverse repertoire of PARylated and non-PARylated protein targets.

Tankyrase-1 (TRF1-interacting ankyrin related ADP-ribose polymerase) was first identified as a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) that localized at human telomeres and interacted with the telomere repeat binding factor 1 (TRF1), a component of the shelterin complex [36]. Tankyrase-1 (PARP-5a) is flanked at the N-terminus by a region carrying homopolymeric histidine, proline and serine (HPS) residues (Figure 1). Tankyrase-1 is a modular protein with multiple interacting domains, including a region containing 24 ankyrin repeats, and a sterile alpha module motif at the C-terminal region. The C-terminus also contains the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) domain responsible for poly ADP-ribosylation of tankyrase-1 and its binding partners using NAD+ as a cofactor [36]. Tankyrase-2 (PARP-5b) is a homolog protein that lacks the N-terminal HPS domain (Figure 1), but shares 83% sequence identity with tankyrase-1 [37]. Tankyrase 2 was first discovered as a tumor antigen that elicited an auto-immune reaction [38, 39]. Due to substantial redundancy between tankyrase 1 and tankyrase 2, single knockout mice did not exhibit any defects in developmental progression, telomere length maintenance, or cell cycle regulation [40]. However, double deficiency was lethal by E10.5.

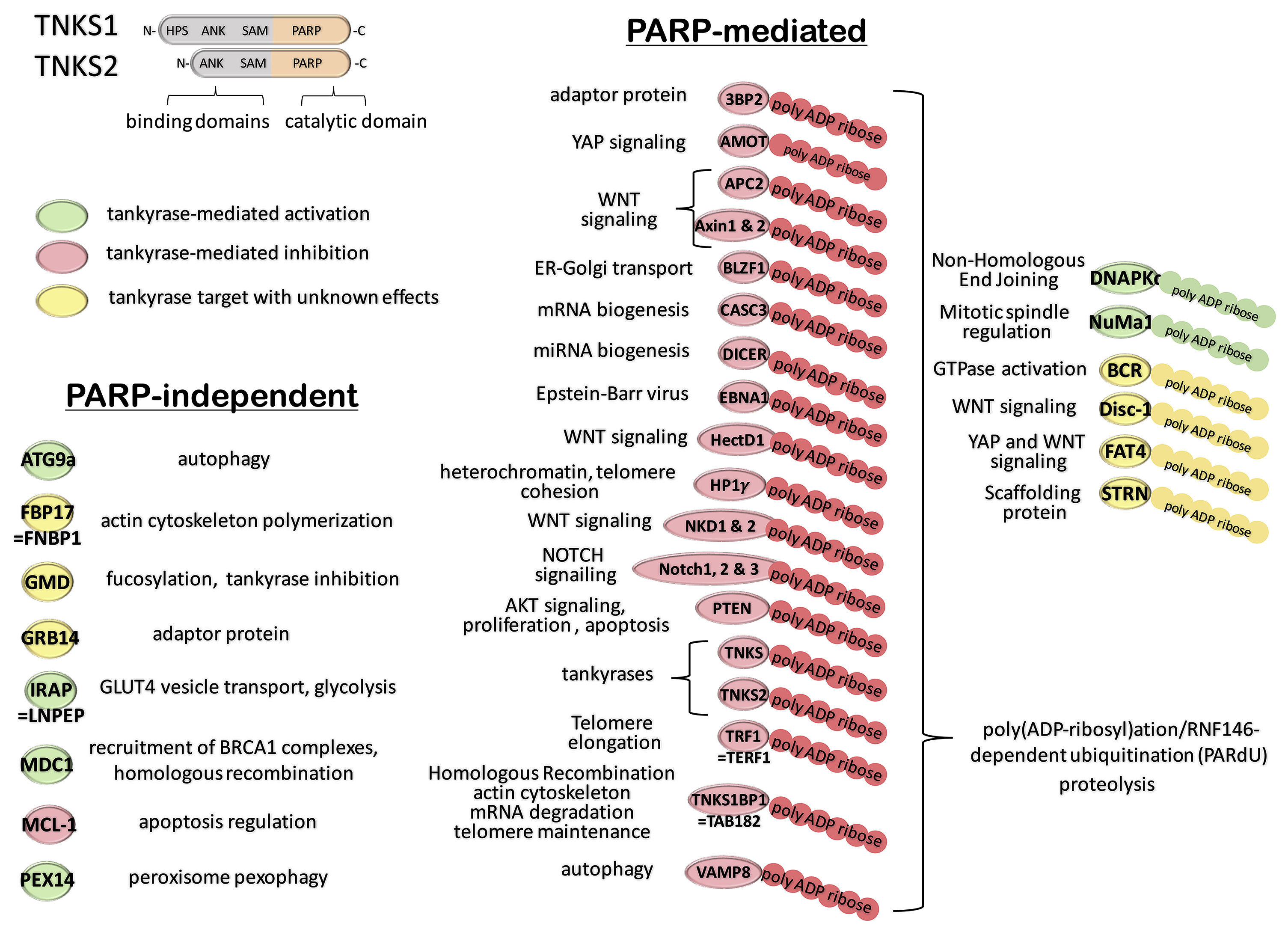

FIGURE 1. Schema of the PARylated and non-PARylated tankyrase interactome.

(Top Left). Although tankyrases share 83% sequence identity, tankyrase-2 differs from tankyrase-1 by lacking the N-terminal homopolymeric histidine, proline and serine (HPS) domain. The C-terminus of tankyrases share binding motifs (a region containing ankyrin repeats (ANK), and a sterile alpha module motif (SAM)) as well as a highly conserved catalytic poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) domain responsible for enzymatic PARP activity. (Bottom Left). Shown are known proteins recruited (green) or inhibited (red) by tankyrases without involvement of their PARylating activity (e.g.., MDC1, ATG9A). Tankyrase interactions with non-characterized effects are indicated in yellow. (Right). Shown are known proteins targeted by tankyrase PARylation. For most target proteins, covalent addition of PAR polymers by tankyrases leads to recruitment of the E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase RNF146, ubiquitination and degradation in the proteasome (red). More rarely, acceptors of tankyrase PARylation have been shown to be activated or recruited (green). The effects of tankyrase PARylation remain to be determined for a number of proteins (yellow).

Both tankyrases localize to multiple subcellular sites in a cell cycle-dependent manner. During interphase, tankyrases predominantly co-localize with TRF1 at telomeres, but can also be detected at nuclear pore complexes. Like most other targets of tankyrase-mediated PARylation (Figure 1), TRF1 undergoes RNF146-dependent ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis upon release from telomeres [41]. Recently, a repertoire of proteins degraded in response to interactions with tankyrases were identified by proteomic analysis of human tankyrase-double-knockout (KO) cells [42]. PARylation-mediated degradation of putative targets was validated using XAV939-treated cells [42]. This study revealed that the tankyrase PARylome extends to multiple components of the WNT, Hippo and NOTCH signaling pathways, as well as DICER (the master regulator of miRNA biogenesis [42]).

During mitosis, concomitant with nuclear envelope breakdown and nuclear pore complex disassembly, tankyrases relocate to the peri-centriolar matrix of mitotic centrosomes [43]. In that context, tankyrases are involved in the control of spindle pole assembly during mitosis via interactions with NuMA [44], a major acceptor of tankyrase-mediated PARylation [45, 46]. Unlike most other proteins that are PARylated by tankyrases, NuMA, and nuclear DNA-dependent serine/threonine protein kinase (DNA-PKc) are stabilized by poly-ADP-ribosylation [47]. The catalytic subunit of DNA-PKc is the key enzyme responsible for non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) DNA repair of double strand breaks [47]. Additionally, tankyrases regulate homologous recombination (HR) via interactions with the DNA-damage sensor MDC1 independently of PARP activity [23].

A recent proteomic analysis evaluated the tankyrase interactome in human cells exposed to XAV939 to specify network interactions that involved PARylation [24]. Interestingly, this study revealed more than 100 tankyrase-interacting proteins that were PARylation-independent (e.g., PEX14, ATG9A; Figure 1). Finally, it should be noted that the mouse and human TRF1 genes show considerable evolutionary divergence; the human PARylation site is not present in the mouse sequence [48, 49]. Indeed, the canonical tankyrase-binding motif within human TRF1 is absent in both mice and rats; two species that share high somatic telomerase activity, and possess much longer telomeres than other mammals [49]. However the PARylation site is conserved in other mammalian species, suggesting that these two rodent species may have evolved tankyrase-independent telomere maintenance mechanisms [49]. Thus, the modeling of tankyrase-mediated effects in rodents requires vigilant scrutiny when studying tankyrase inhibitors in human cell systems.

Tankyrases exert control over multiple signaling pathways that orchestrate molecular pluripotency via PARP-dependent and PARP-independent mechanisms.

Even though tankyrases were first identified as negative post-translational regulators of TRF1 [36], most current studies of pluripotency that employ tankyrase inhibitors have focused primarily on tankyrase control over AXIN and its effects on the canonical WNT pathway [8, 33, 42, 50]. Indeed, although tankyrase-mediated PARylation directly controls the stability of multiple components of the canonical WNT pathway (Figure 1), it also exerts direct control over multiple master regulators including NOTCH [42], DICER [42], PTEN [51], and Hippo/YAP (i.e., via Angiomotin (AMOT)) [42, 52]. Additionally, the concentration at which XAV939 is used in most pluripotency-related studies (i.e., 4–10 μM) likely exerts inhibition of PARP1, PARP2, and PARP3 [24]. Such non-specific PARP inhibition may alter the activity of multiple PARylated proteins that regulate DNA methylation (e.g., DNMT1, CTCF, TET1 and UHRF1 [53]). Because these proteins direct and maintain transitions between primed and pluripotent epigenomes [1], the level of tankyrase-mediated and PARP-mediated PARylation may indirectly regulate these pluripotent states by controlling DNA methylation. Thus, inhibition of tankyrase-mediated PARylation may exert pleiotropic effects that synergize to stabilize multiple pluripotency networks that are usually considered to be independent (summarized in Figure 2). The putative effects on specific pluripotency pathways are reviewed below.

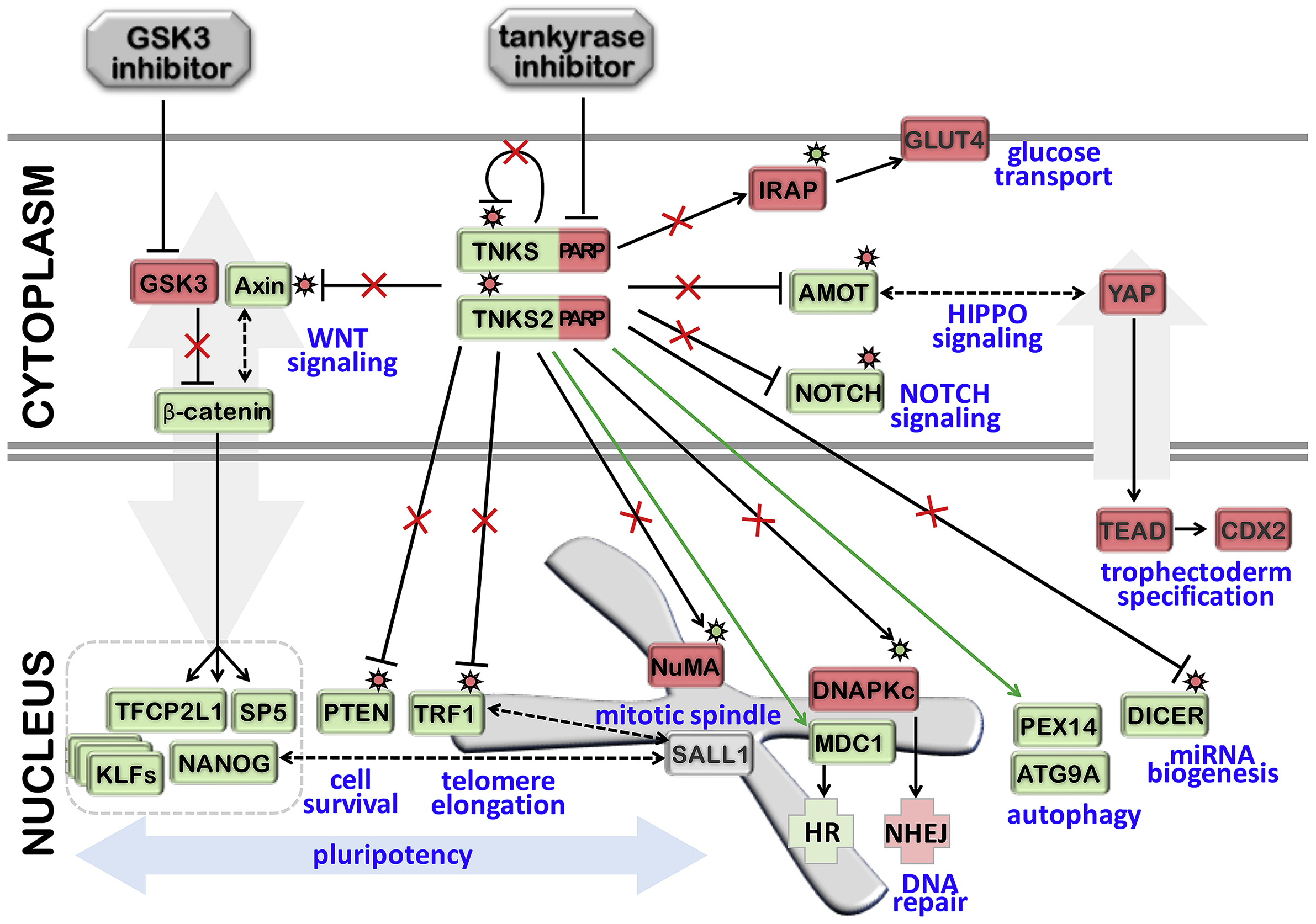

FIGURE 2. Schema of the putative downstream effects of LIF-3i that may maintain human naïve pluripotency.

The human LIF-3i medium cocktail combines human LIF (i.e., Leukemia inhibitory factor; JAK/STAT3 activation) and the small molecules PD0325901 (i.e., MEK inhibitor; FGF/MEK/ERK blockade), CHIR99021 (i.e., GSK3-β inhibitor; interrupts the initiation of the cascade of phosphorylation of β-catenin and β-catenin degradation) and XAV939 (i.e., inhibitor of tankyrase-mediated PARylation). The outcomes of XAV939-mediated inhibition of tankyrases (TNKS1 and TNKS2) on the tankyrase interactome are complex. XAV939 is a small molecule with high affinity for TNKS1 and TNKS2 that blocks the enzymatic domain responsible for PARylation (PARP). Tankyrases act primarily as post-translational inhibitors (via RNF146 recruitment and proteolysis of target proteins (e.g., AXIN, TRF1, AMOT, NOTCH, DICER, PTEN)). In the LIF-3i cocktail, CHIR99021 and XAV939 synergize to stabilize AXIN and reorganize the subcellular distribution of the active isoform of β-catenin. Downstream effects of this β-catenin reorganization may reinforce core pluripotency factor and KLF protein circuitry expression, and other WNT targets that orchestrate the naïve state (e.g., SP5, TFCP2L1). XAV939-mediated inhibition of tankyrase PARylation can also activate select proteins (e.g., DNAPKc, NuMA, IRAP). Because tankyrases auto-PARylate, XAV939 simultaneously stabilizes the tankyrase proteins themselves, while repressing their PARP activity. Several proteins have been shown to be recruited by tankyrases independently of PARylation and regulators of homologous recombination (e.g., MDC1), and autophagy (PEX14 and ATG9A).

Thus, we propose that XAV939 potentiates a broad array of PARP-dependent and PARP-independent cellular effects that may stabilize the human naïve pluripotent state. Arrows and blocked lines represent the actual activities between each proteins and/or small molecules. Asterisks symbolize PARylation that are inhibiting (red) or activating (green) the target proteins. The resulting effects of tankyrase PARP domain inhibition by XAV939 and GSK3β inhibiton by CHIR99021 are represented by red crosses (disrupted inhibition or activation) and green arrows (PARP-independent tankyrase-mediated activation) with resulting stabilized or inhibited proteins/domain in green or red respectively.

Tankyrase regulation of WNT/β-catenin signaling.

The net effects of tankyrase inhibition on WNT regulation of pluripotency are complex, and depend on cellular context and synergy with other small molecules. We previously reviewed the divergent outcomes of AXIN stabilization on β-catenin subcellular localization and shuttling based on the on/off state of the WNT/β-catenin pathway, and the putative role of these configurations to support either primed or naïve pluripotent states [1]. The canonical WNT pathway controls the stability of its downstream effector β-catenin via a cascade of phosphorylations initiated by the protein kinase GSK3β within a destruction complex (AXIN/APC/GSK3β). Chemical inhibitors of GSK3β (i.e., CHIR99021) disrupt β-catenin destruction, and stabilize the active non-phosphorylated β-catenin isoform. Reinforcement of WNT signaling via GSK3β inhibition has been exploited to reinforce naïve pluripotency in mouse ESC [54], and to promote acquisition of expanded functionality in primed EpiSC [55, 56].

Among targets of the WNT pathway, most tankyrase inhibitor studies have focused on stabilizing effects on AXIN, which is the limiting component of the β-catenin destruction complex [27]. For example, in cultures supplemented with FGF2, XAV939 by itself stabilized AXIN, promoted destruction of β-catenin, and supported the growth of primed murine EpiSC [50, 57]. Similar studies reported the use of other WNT inhibitors that do not affect tankyrase-mediated PARylation (i.e., the Porcupine inhibitor IWP-2 [58]) or target a different binding site than XAV939 in the PARP domain of tankyrases and with weaker inhibition of PARP1/2 (i.e., IWR-1-endo) [27], and demonstrated improved mouse EpiSC derivation or reinforced the primed pluripotent state [57, 59]. However, in the absence of FGF2 and in the context of simultaneous co-inhibition of both GSK3β and tankyrases (i.e., CHIR99021 + XAV939), stabilization of AXIN that did not diminish β-catenin stability occurred, and instead paradoxically reinforced the levels of active non-phosphorylated β-catenin in non-nuclear compartments (i.e., cytoplasm, membrane) [8, 33]. Simultaneous stabilization of activated β-catenin its component partners of the AXIN/APC/GSK3β complex can alter the subcellular localization of β-catenin [60–63] particularly in the cytoplasm [63, 64]. These CHIR99021/XAV939 co-inhibitory activities synergized to relocate activated non-phosphorylated β-catenin from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and membrane; which resulted in a paradoxical net augmentation of WNT/β-catenin signaling. [8, 33, 63]. Thus, CHIR99021/XAV939 co-inhibition improved not only the growth of murine EpiSC [33], but when combined simultaneously with LIF and MEK inhibitor (PD032590) differentiation blockade, allowed stabilization of a human naïve pluripotent stem cell state [8].

Interestingly, NANOG and OCT4 form multiple complexes with β-catenin in the nucleus and cytoplasm of mouse ESC [65, 66], and OCT4 participates in a shuttling complex with β-catenin and AXIN [67]. β-catenin fluctuations may similarly control NANOG levels in mouse naïve ESC [68], and a membrane-associated β-catenin/OCT4 complex specifically marks the mouse ground-state of pluripotency [65]. We previously proposed that rewiring of β-catenin stability and localization similarly impacted the shuttling and nuclear availability of the core pluripotency factors NANOG and OCT4, as well as reinforced E-Cadherin/STAT3 signaling in LIF-3i-reverted hPSC [1, 8].

Tankyrase regulation of Hippo signaling.

The Hippo downstream effector YAP is a critical factor for sustaining stable mESC growth and differentiation [69]. While YAP downregulation impairs pluripotency, its overexpression promotes mESC self-renewal and represses differentiation [69]. Interestingly, ectopic YAP overexpression also promoted a human naïve pluripotent state when combined with the adenyl-cyclase agonist Forskolin [15]. Hippo signaling was also reported to regulate pluripotency in primed hESC via a mechanism involving switch-enhancers [70]. These enhancers control fate decisions through a regulatory complex that involves OCT4, Hippo and TGFβ signaling and NurD repressor complexes [70]. YAP pluripotency targets are diverse and include members of the Polycomb repressor complex (e.g., the histone methyltransferase EZH2), core pluripotency factors, and downstream effectors of LIF and BMP4 pathways [69].

Interestingly, Hippo signaling is also critical for the normal development of trophectoderm derivatives [71]. In mouse blastocysts, YAP protein expression is restricted to the cytoplasm in ICM cells, and in nuclei in trophectoderm cells [72]. XAV939 targets YAP by stabilizing angiomotin (AMOT) [52]. AMOT further antagonizes YAP signaling by translocating YAP into the cytoplasm to prevent differentiation of ICM cells toward trophectoderm [73]. However, the ICM of dpf 5–6 human embryos does not replicate the cytoplasmic retention patterns of murine YAP, but rather exhibits diffuse nuclear staining in ICM cells and a punctuated nuclear pattern in trophectoderm cells [15]. Thus, a higher complexity of YAP accessibility and cellular regulation may exist in human cells.

Furthermore, tankyrase inhibition may indirectly control Hippo signaling not only through AMOT stabilization, but also via AXIN stabilization. The E-Cadherin/β-catenin complex is an upstream regulator of Hippo signaling [74] and the Hippo effectors YAP and TAZ can incorporate within the β-catenin destruction complex [75]. AXIN1 regulates the nuclear accessibility of YAP/TAZ [75]. In a WNT-on state, displacement of AXIN1 promotes interactions with the membrane receptor LRP6 and antagonizes YAP/TAZ transcriptional activities [75]. Inversely, YAP-mediated effects may negatively regulate differentiation via GSK3β inhibition of active β-catenin levels [15]. The ultimate outcome on YAP/TAZ signaling from the simultaneous (and possibly synergistic) stabilization of AXIN1 and AMOT and forced WNT-on state by GSK3β chemical blockade employed in the LIF-3i naïve reversion method remains to be clarified [8].

Tankyrase regulation of PTEN.

The tumor suppressor PTEN, a well-known negative regulator of PI3K signaling and mediator of apoptosis, was recently identified as a substrate for tankyrase PARylation in cancer cells [51]. PTEN can be detected in mouse embryos from the 2-cell to the blastocyst stage, albeit subcellular localization appears to differ between isoforms at the cleavage stage [76]. A similar differential subcellular localization of PTEN was reported in Xenopus embryos, and was essential for proper gastrulation [77]. Tankyrase-mediated PARylation-induced PTEN ubiquitination and degradation has been reported to be efficiently inhibited by XAV939 [51]. Such inhibition of PARylation downregulated the AKT phosphorylation and glycolytic activities associated with PTEN. Although a similar role for XAV939-mediated reinforcement of PTEN in LIF-3i-reverted N-hPSC remains to be identified, PTEN is essential for proper development of the preimplantation embryo [78]. Exposure to a PTEN inhibitor significantly impaired the developmental competence of mouse embryos beyond the 2-cell stage, with increasing sensitivity up to the blastocyst stage [76]. Injection of a PTEN antisense oligonucleotide into uterine horns at day 3 of pregnancy also interfered with embryo implantation, but mainly by altering decidualization of endometrial cells [79]. Interestingly, PTEN knockout in mESC also resulted in aberrant formation of embryoid bodies as well as altered multi-lineage directed differentiation and oxidative phosphorylation [78]. PTEN was also shown to regulate pluripotency and lineage bias in primed hESC [80]. Although PTEN knockdown improved hESC survival, it significantly impaired directed multi-lineage differentiation capacity, and mediated a pronounced differentiation bias toward neuroectoderm lineages [80].

Tankyrase regulation of NOTCH signaling.

Multiple NOTCH isoforms are regulated by tankyrase-mediated PARylation in human cells [42]. Notch is active from the 4-cell stage and becomes restricted to the trophectoderm in the blastocyst [81]. Additionally, Notch signaling converges with the Hippo pathway in early preimplantation mouse embryos to regulate expression of Cdx2 and specify the trophectoderm [82]. Notch later reactivates throughout the epiblast upon implantation [83], and Notch signaling has been proposed to control exit from naïve pluripotency by antagonizing early naïve genes (e.g., Dppa3, Prdm14) and controlling the expression of transcriptional repressors (e.g., Tle4, Tbx3) [81]. Notch signaling also plays a role in potentiating neuroectoderm differentiation [84]. Thus, Notch signaling may play multiple distinct roles in tankyrase-inhibited N-hPSC to potentiate the observed augmentation of functional pluripotency.

Tankyrase regulation of DICER and miRNA biogenesis.

Dicer is a critical RNase III protein that mediates miRNA biogenesis, and is essential for mouse development and mESC derivation [85]. Interestingly, a double tankyrase knockout in human cells revealed that Dicer is a primary target of tankyrases [42]. Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of tankyrases over DICER stability involves their PARylating activity and was revealed with XAV939 [42].

Furthermore, the loss of Dicer compromised mESC self-renewal [86] and destabilized naïve pluripotency [87]. RNA interference of DICER repressed the translation of several chromatin regulators (e.g., Dnmt3b, SmarcA4, Kdm2b) that are essential for naïve mESC stability [87]. Most dicer-null mutants died at embryonic day E7.5, and the remaining mouse embryos were poorly developed, malformed, and lacked multipotent stem cells [85]. Dicer excision in mESC disrupted maturation of miRNA and silencing mediated by long dsRNA [86]. Additionally, other studies reported epigenetically-regulated shifts in miRNA expression during maturation of morulae into blastocysts [88], as well as during naïve mESC and primed EpiSC transitions [89]. Overall, we propose that a XAV939-mediated stabilization of DICER may be a main mechanism for supporting a naïve preimplantation epiblast-like phenotype in LIF-3i-reverted N-hPSC.

Tankyrases regulate multiple activities during early preimplantation development, including trophectoderm specification

Proteomic studies have revealed that tankyrases control the proteolysis of a broad repertoire of PARylated target proteins (Figure 1) [24, 42]. The tankyrase interactome is complex and includes target proteins that both bind tankyrases independent of their PARP activity, as well as proteins that require their active PARylation activity. Several partners of tankyrases regulate biological activities that are prominent during preimplantation (Figure 2).These critical activities include autophagy (e.g., via PEX14 and ATG9A [24], VAMP8 [42]), trophectoderm specification (e.g., via Notch [42], and Hippo [42]) signaling, miRNA biogenesis (i.e., DICER [42]), homologous recombination (i.e., MDC1 [23]), and telomere elongation (i.e., TRF1 [36]).

Single cell analyses have delineated trophectodermal lineage segregation steps from E2.5 morulae to E4.5 blastocysts in the mouse [90, 91], and E5 human preimplantation blastocysts [92]. While murine tankyrase double knockout embryos deteriorated by E10.5, these studies revealed a role for tankyrases in early lineage segregation [40]. Interestingly, the poorly developed tankyrase-mutant embryos possessed aberrant placentae and no umbilical cord, suggesting an impact of tankyrase deficiency on the development of trophectoderm derivatives [40]. Contribution of tankyrase in trophectoderm lineage specification may reflect regulatory roles of multiple targets including effectors of Hippo [52] and Notch [42] signaling; two pathways that converge to control Cdx2 expression and the emergence of trophoblast derivatives in preimplantation embryos [71, 82].

Tankyrases may also regulate trophectoderm specification through Cripto-1/TDGF1-TGF-β signaling [93]. Cripto is a co-receptor of Nodal and controls embryo patterning during gastrulation, as well as germ layer lineage specification [94]. Cripto is a primary target of β-catenin in the early embryo [93], but Cripto itself enhances WNT signaling by binding to the LRP5/LRP6 co-receptors and stabilizing cytoplasmic β-catenin [95] in a manner similar to that observed in XAV989-inhibited N-hPSC [8]. However, the role of Cripto in human naïve pluripotency may be more complex; unlike in the mouse, human naive epiblast expresses high levels of NODAL and Cripto/TDGF1 [92, 96]. In mESC, Cripto controls trophoblast specification by positively modulating the canonical WNT pathway [97]. Cripto has also been proposed to be a key determinant of the transition between naïve and primed states in mouse and human PSC [97].

Tankyrase regulation of telomeres and centromeres

Tankyrase was originally discovered in human cells as a negative post-transcriptional regulator of TRF1, a protein that controls telomere lengthening [36]. Telomere lengthening has previously been linked to functional pluripotency in mESC, including capacity for chimeric formation and germline contribution [98]. Even though tankyrase does not control Trf1 in rodents, mouse studies of TRF1 and the shelterin complex may provide clues on the role of tankyrase-mediated PARylation at hPSC telomeres. Trf1 deletion led to embryonic lethality independently of telomere elongation by telomerase and promoted severe growth defects of the mouse ICM [99]. Importantly, TRF1 expression facilitates cellular reprogramming [100], and controls functional pluripotency independently of its telomere activity in mouse embryos [99], but also in human PSC [100].

Mouse ESC are characterized by a non-restrained expansion of their telomeres that do not accurately reflect their telomere lengths in the ICM in vivo [101]. This discordance was attributed to loss of telomeric heterochromatin histone marks and reinforcement of TRF1 expression levels [101]. The molecular mechanism that links TRF1 to functional pluripotency is unclear, but may involve interactions with the transcriptional repressor SALL1 at pericentromeric heterochromatin (Figure 2) [102] where it ensures Aurora B kinase recruitment at centromeres and reinforces sister centromere cohesion for proper chromosome segregation during mitosis [103]. Interestingly, SALL1 also enhanced canonical WNT signaling by localizing to the heterochromatin [104] and epigenetically regulating ESC differentiation via promoting and synergizing with Nanog expression while inhibiting expression of primed developmental genes [105]. More recently, TRF1 has been shown to recruit the Polycomb Repressor complex 2 (PRC2) to pluripotency genes and regulate the genome-wide deposition of H3K27me3 repressive marks by controlling the expression of the telomere-transcribed long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) TERRA in mouse naïve PSC [106]. Future studies will be necessary to elucidate a similar involvement of XAV939-induced stabilization of TRF1 and TERRA lncRNA regulation of PRC2 in LIF-3i-cultured hPSC.

Tankyrase control of DNA repair and alternative telomere elongation (ALT)

Another substrate of tankyrase, DNA-PKc, is the key enzyme responsible for NHEJ [47]. PARylation of DNAPKc promotes its stabilization and reinforce NHEJ activity [47]. NHEJ negatively regulates telomere recombination and sister chromatid exchange (SCE)-like recombination between telomeres (T-SCE) [47]. T-SCE is emerging as an alternate mechanism for telomere elongation in the absence of telomerase activity. Although alternative telomere lengthening (ALT) is exploited by cancer cells (reviewed in [107]), recombination-mediated ALT is a normal telomere lengthening mechanism during early preimplantation embryogenesis [108]. Telomere lengthening in early cleavage embryos preferentially utilizes ALT-mediated mechanisms (i.e., T-SCE and HR) rather than telomerase-mediated lengthening, which progressively takes over telomere maintenance from the blastocyst stage onwards [108]. Unlike mESC [109], conventional hESC rely exclusively on telomerase for telomere maintenance once the lines are established [110]. However, ALT pathway activity can be detected during early expansion of human blastocysts [110]. Thus far, no human naïve pluripotency study has investigated usage of ALT-like mechanisms for telomere elongation.

Tankyrases not only promote NHEJ-mediated DNA repair in response to double strand DNA breaks via PARylation of DNA-PKc [47], but they can also potentiate HR-mediated DNA repair by binding to MDC1 at DNA lesions [23]. This interaction regulates DNA end resection and activates checkpoint activation by stabilizing the BRCA1A complex [23]. The recruitment of MDC1 does not involve the catalytic domain of tankyrase and as a result, the inhibitor XAV939 does not interfere with the effects of tankyrase on HR [23]. In comparison, XAV939 exposure rapidly depleted DNA-PKc protein levels and suppressed NHEJ [47]. Consequentially, inhibition of the catalytic domain of tankyrase by XAV939 may directly alter the balance between HR and NHEJ-mediated repairs and synthesis.

Mouse ESC preferentially utilize HR [111] and exhibit low levels of DNA-PKc in comparison to primed hESC [112] which employ predominantly the error-prone NHEJ repair system [113]. Inhibition of NHEJ is known to improve HR efficiencies and was used to promote HR-mediated CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing strategies [114, 115]. A few human naïve states have demonstrated enhanced HR capacity [16, 116]. Future studies should explore if LIF-3i N-hPSC possess a preferential mechanism for telomere elongation and DNA repair. It should be noted that Zimmerlin et al did not detect obvious deleterious effects on karyotype or epigenomic imprinting from the LIF-3i medium, despite use of MEK inhibition [11, 17–19].

Crosstalk between tankyrases and cellular metabolism

Tankyrases are members of the PARP family, which are enzymes that utilize NAD+ as a substrate to post-translationally either modify a variety of proteins and alter their affinity for binding partners, or alternatively, recruit the E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase RNF146 for proteolysis by covalently adding poly-ADP-ribose polymers [36]. Accordingly, PARylation intersects with both primed and naïve PSC metabolism (Figure 3). PARylation is accompanied by marked reductions in cellular NAD+ and ATP levels, and energetic expenditures related to PARP activation can be catastrophic to the cell and lead to mitochondrial energy failure [117]. Despite strong sequence similarity between the catalytic domains of PARPs, PARP-1, PARP-2, and tankyrases all produce longer PAR polymers than other PARPs, and are responsible for most of PARP-related NAD+ consumption [118]. Other PARP enzymes are either generally defective in elongation or mostly inactive [118].

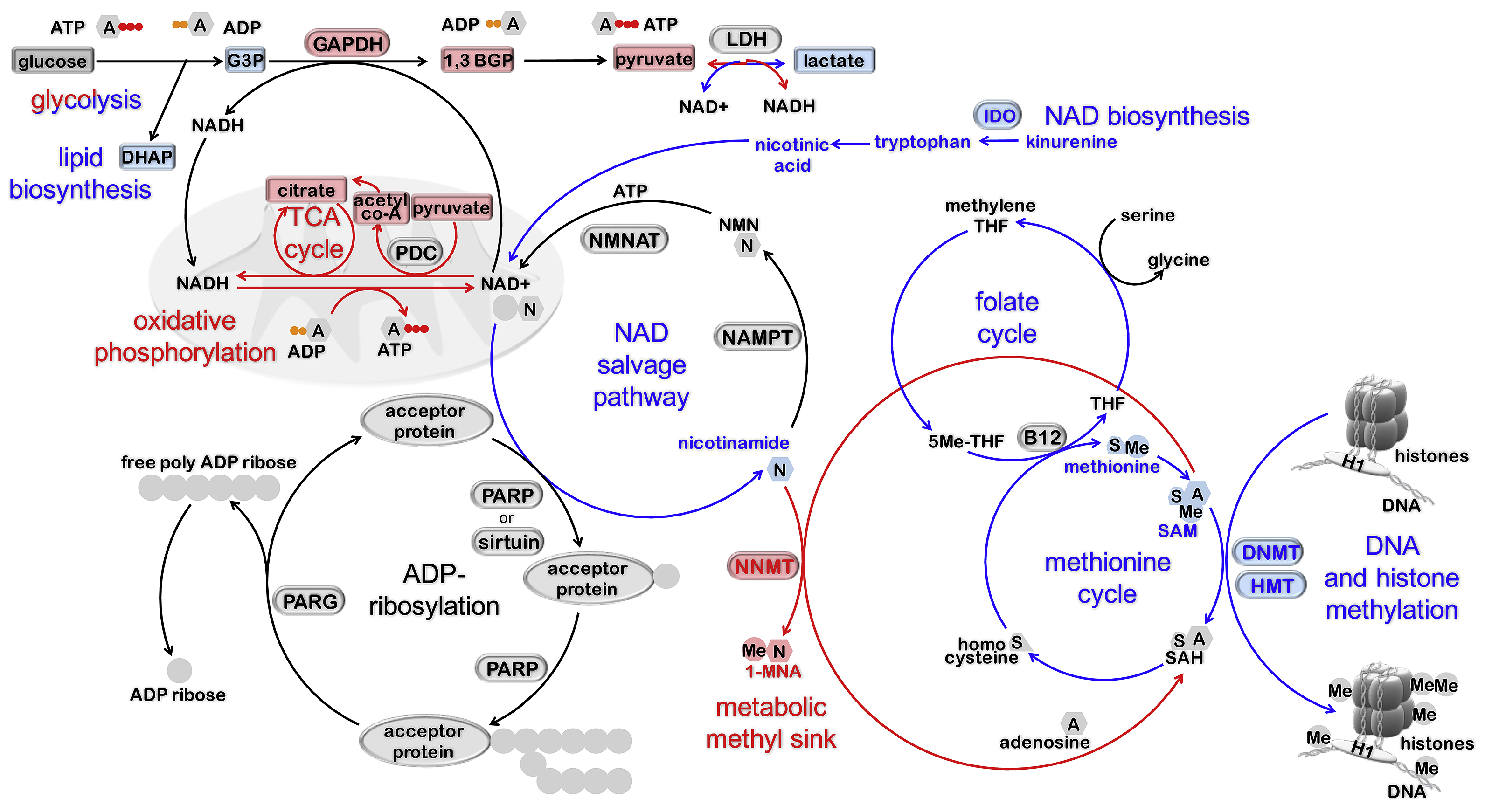

FIGURE 3. PARylation is at the intersection of primed and naïve pluripotent metabolomes.

Distinct metabolomes have been characterized in primed and naïve states of human and mouse PSC [128, 129]. Metabolic activities, metabolites, and enzymes that are predominant in primed and naïve pluripotent states [128, 129] are indicated in blue and red, respectively. The substrate of ADP-ribosylation (i.e., NAD+) and its byproduct (i.e., nicotinamide) are integrated within PSC metabolic activities (i.e., oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis, metabolic methyl-sink, one-carbon cycle). PARP-1, PARP-2, and tankyrases produce longer PAR polymers than all other PARP, and are responsible for most PARP-related NAD+ consumption. Thus, the PARP activity of these enzymes is presumptively the most affected by switching metabolism.

A metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis occurs in the preimplantation embryo [119–121], and demarcates the morula stage in regards to energy substrate use and oxygen consumption (reviewed in [122], Figure 3). The balance between oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis is an established determinant of the NADH/NAD+ cellular ratio and a well-known regulator of Sirtuins (SIRT), another family of NAD+ dependent enzymes with HDAC and mono-ADP-ribosyl-transferase activity [123] that is involved in the maintenance of naïve mESC [124]. A crosstalk between PARP and SIRT activity, possibly involving competition for NAD+ has been suggested [125], and may be connected by nicotinamide, a PARylation byproduct, and a known inhibitor of SIRT activity [126]. High rates of glycolysis led to an elevated NADH/NAD+ ratio and downregulated the HDAC activity of SIRT [123]. Similarly, the augmentation of NAD+ flux resulting from glucose metabolism appears to drive the PARylating activity of tankyrases in insulinoma cells [127].

A switch between bivalent respiration and exclusive anaerobic glycolysis-dependent metabolism also occurs during the transition between mouse and human naïve ESC to primed PSC [121, 128, 129]. This metabolic switch involves the nicotinamide-N-methyltransferase (NNMT), an enzyme consuming two substrates, S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) and nicotinamide [128]. Sperber et al proposed that N-hPSC [13] are regulated by an NNMT-induced methyl-sink (Figure 3), where NNMT and its enzymatic product 1–1-methyl-nicotinamide (1-MNA) are highly upregulated, while levels of its substrates, nicotinamide and SAM are reduced, thereby sequestering histone repressive marks [128].

Gene targeting experiments suggested that the reduced body weight of tankyrase 2 mutant mice was related to altered glucose uptake in adipose cells [40]. However, it was later revealed that tankyrase-deficient mice exhibited an increase in energy expenditure, fatty acid oxidation, and insulin-stimulated glucose consumption; without any effect on mitochondrial respiration [130]. Although this mechanism is unclear, tankyrases localize not only to the nucleus, but cytoplasmic patterns are also detected in the Golgi, where tankyrases interact with IRAP [131] to promote membrane translocation of the glucose transporter GLUT4 [130]. Insulin-mediated exocytosis of GLUT4 storage vesicles were also reported to require both IRAP and the PARylating activity of tankyrase [132]. It was also established that this tankyrase-mediated regulation of GLUT4 involves AXIN [133].

Tankyrase inhibition by XAV939 also reinforced mitochondrial AXIN levels in HeLa cells and increased glycolysis without modifying the mitochondrial membrane potential [134]. Indeed, while tankyrase may participate in the regulation of oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis via AXIN stabilization [135], metabolic alteration in human naïve PSC have revealed a reciprocal feedback on WNT signaling. NNMT KO in human naïve PSC not only disrupted the naïve epigenome by augmenting levels of H3K27Me3 repressive histone marks, but also contributed to inhibiting WNT signaling [128]. Collectively, these data support the importance of sustained WNT signaling for maintaining naïve epiblast-like metabolism in human PSC. It is possible that the manipulation of NAD+ flux and nicotinamide metabolism alter PARP activities, including tankyrase-mediated WNT regulation. In any case, these studies support the notion that cellular metabolism and tankyrase PARP activities are closely and reciprocally intertwined.

Conclusions

Various complex small molecule approaches have putatively captured human ‘naïve-like’ pluripotent molecular states that are more primitive than those exhibited by conventional, lineage-primed hiPSC. However, many culture systems supporting human naïve-like pluripotency have potentiated karyotypic instability, global loss of parental genomic imprints, and impaired multi-lineage differentiation performance. Tankyrase-inhibited N-hiPSC and N-hESC did not suffer these caveats, and possessed greater differentiation potency than conventional hPSC. This improved functional pluripotency was potentiated by inclusion of the small molecule tankyrase/PARP inhibitor XAV939 to the classical 2i (GSK3β/MEK inhibition) naive reversion chemical cocktail. Along with expanded pluripotency stem cells (EPSC) that also employ XAV939 chemical modulation, tankyrase-inhibited N-hPSC may be members of a new class of pluripotent stem cells with high functionality and improved epigenetic stability that may highly impact regenerative medicine. In this review, we have outlined a hypothetical framework for how inclusion of a tankyrase/PARP inhibitor to the classic LIF-2i cocktail may stabilize and potentiate naïve and extended pluripotency via pleiotropic routes and mechanisms. Future investigations will focus on elucidating the non-PARylating functions of tankyrase that stabilize human naïve and extended pluripotency without promoting the genomic or epigenomic abnormalities that were reported in other human naïve systems that did not employ a tankyrase inhibitor in their small molecule cocktails.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the NIH/NEI (R01EY023962), NIH/NICHD (R01HD082098), RPB Stein Innovation Award, The Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund (2018-MSCRFV-4048), and The Lisa Dean Moseley Foundation.

ABBREVIATIONS

- 1-MNA

1–1-methyl-nicotinamide

- ADP

adenosine diphosphate

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- ALT

alternate lengthening of telomeres

- AMOT

angiomotin

- ATG9A

autophagy-related protein 9A

- BMP4

bone morphogenetic protein 4

- BRCA1

breast cancer 1 gene

- CDX2

caudal type homeobox 2

- CTCF

CCCTC-binding factor

- CRISPR

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- DICER

double-stranded RNA-specific endoribonuclease

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- DNA-PKc

DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit

- DNMT

DNA methyltransferase

- DPPA3

developmental pluripotency-associated 3

- dsRNA

Double-strand ribonucleic acid

- EpiSC

epiblast stem cell

- EPS

extended pluripotent stem

- EPSC

expanded potential stem cell

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- EZH2

enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit

- FGF2

fibroblast growth factor 2

- GLUT4

glucose transporter type 4

- GSK3β

glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- hESC

human embryonic stem cell

- hiPSC

human induced pluripotent stem cell

- hPSC

human pluripotent stem cell

- HPS

histidine, proline, serine

- HR

homologous recombination

- ICM

inner cell mass

- IRAP

insulin responsive amino peptidase

- KDM2B

Lysine Demethylase 2B

- KO

knock-out

- LIF

leukemia inhibitory factor

- lncRNA

long non-coding RNA

- LRP5/6

LDL receptor related protein 5/6

- MDC1

Mediator of DNA damage checkpoint protein 1

- MEK

mitogen-activated protein ERK kinase

- mESC

mouse embryonic stem cell

- miRNA

microribonucleic acid

- N-hPSC

naïve human pluripotent stem cell

- NAD

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NANOG

Nanog homeobox

- NHEJ

non-homologous end joining

- NNMT

nicotinamide-N-methyltransferase

- NOTCH

Notch receptor

- NuMA

nuclear mitotic apparatus protein

- NuRD

mucleosome remodeling deacetylase

- OCT4

octamer-binding transcription factor 4

- PAR

poly-ADP-ribose

- PARP

poly ADP ribose polymerase

- PEX14

peroxisomal Bbogenesis factor 14

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PRC2

Polycomb Repressor complex 2

- PRDM14

PR/SET domain 14

- PSC

pluripotent stem cells

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- RNase

ribonuclease

- RNF146

E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase ring finger protein 146

- SALL1

spalt Llke transcription factor 1

- SAM

S-adenosyl-methionine

- SCE

sister chromatid exchange

- SIRT

sirtuin

- SMAD

mothers against decapentaplegic homolog

- SMARCA4

SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily A, member 4

- SRC

SRC (sarcoma) proto-oncogene, non-receptor tyrosine kinase

- STAT3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- T-SCE

telomere sister chromatid exchange

- Tankyrase

TRF1-interacting ankyrin related ADP-ribose polymerase

- TAZ

transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif

- TBX3

T-box 3

- TDGF1

teratocarcinoma-derived growth factor-1

- TERRA

telomeric repeat-containing RNA

- TET1

ten-eleven translocation 1

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor beta

- TLE4

transducin-like enhancer of split 4

- TNKS

tankyrase

- TRF1

telomere repeat binding factor 1

- UHRF1

ubiquitin-like PHD and RING finger domain-containing protein 1

- VAMP8

vesicle associated membrane protein 8

- VP

vascular progenitors

- WNT

wingless-type MMTV integration site family

- XEN

extraembryonic endoderm stem

- YAP

yes-associated protein

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zimmerlin L, Park TS, and Zambidis ET, Capturing Human Naïve Pluripotency in the Embryo and in the Dish. Stem Cells Dev, 2017. 26(16): p. 1141–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ying QL, et al. , BMP induction of Id proteins suppresses differentiation and sustains embryonic stem cell self-renewal in collaboration with STAT3. Cell, 2003. 115(3): p. 281–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshida K, et al. , Maintenance of the pluripotential phenotype of embryonic stem cells through direct activation of gp130 signalling pathways. Mech Dev, 1994. 45(2): p. 163–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niwa H, et al. , Self-renewal of pluripotent embryonic stem cells is mediated via activation of STAT3. Genes Dev, 1998. 12(13): p. 2048–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams RL, et al. , Myeloid leukaemia inhibitory factor maintains the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells. Nature, 1988. 336(6200): p. 684–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossant J, Stem cells and early lineage development. Cell, 2008. 132(4): p. 527–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ying QL, et al. , The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature, 2008. 453(7194): p. 519–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmerlin L, et al. , Tankyrase inhibition promotes a stable human naïve pluripotent state with improved functionality. Development, 2016. 143(23): p. 4368–4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H, et al. , Reinforcement of STAT3 activity reprogrammes human embryonic stem cells to naive-like pluripotency. Nat Commun, 2015. 6: p. 7095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takashima Y, et al. , Resetting Transcription Factor Control Circuitry toward Ground-State Pluripotency in Human. Cell, 2014. 158(6): p. 1254–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Theunissen TW, et al. , Systematic identification of culture conditions for induction and maintenance of naive human pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell, 2014. 15(4): p. 471–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanna J, et al. , Human embryonic stem cells with biological and epigenetic characteristics similar to those of mouse ESCs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010. 107(20): p. 9222–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ware CB, et al. , Derivation of naive human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2014. 111(12): p. 4484–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo G, et al. , Epigenetic resetting of human pluripotency. Development, 2017. 144(15): p. 2748–2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin H, et al. , YAP Induces Human Naive Pluripotency. Cell Rep, 2016. 14(10): p. 2301–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gafni O, et al. , Derivation of novel human ground state naive pluripotent stem cells. Nature, 2013. 504(7479): p. 282–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Theunissen TW, et al. , Molecular Criteria for Defining the Naive Human Pluripotent State. Cell Stem Cell, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo G, et al. , Naive Pluripotent Stem Cells Derived Directly from Isolated Cells of the Human Inner Cell Mass. Stem Cell Reports, 2016. 6(4): p. 437–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pastor WA, et al. , Naive Human Pluripotent Cells Feature a Methylation Landscape Devoid of Blastocyst or Germline Memory. Cell Stem Cell, 2016. 18(3): p. 323–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi J, et al. , Prolonged Mek1/2 suppression impairs the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells. Nature, 2017. 548(7666): p. 219–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park TS, et al. , Chemical Reversion of Conventional Human Pluripotent Stem Cells to a Naïve-like State with Improved Multilineage Differentiation Potency. JoVE, 2018(136): p. e57921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park TS, et al. , Vascular Progenitors Generated from Tankyrase Inhibitor-Regulated Diabetic Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Potentiate Efficient Revascularization of Ischemic Retina. bioRxiv, 2019: p. 678599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagy Z, et al. , Tankyrases Promote Homologous Recombination and Check Point Activation in Response to DSBs. PLoS Genet, 2016. 12(2): p. e1005791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, et al. , Proteomic Analysis of the Human Tankyrase Protein Interaction Network Reveals Its Role in Pexophagy. Cell Rep, 2017. 20(3): p. 737–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsukamoto S, et al. , Autophagy is essential for preimplantation development of mouse embryos. Science, 2008. 321(5885): p. 117–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koh DW, et al. , Failure to degrade poly(ADP-ribose) causes increased sensitivity to cytotoxicity and early embryonic lethality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004. 101(51): p. 17699–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang SM, et al. , Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes ax in and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature, 2009. 461(7264): p. 614–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karlberg T, et al. , Structural basis for the interaction between tankyrase-2 and a potent Wnt-signaling inhibitor. J Med Chem, 2010. 53(14): p. 5352–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haikarainen T, et al. , Structural basis and selectivity of tankyrase inhibition by a Wnt signaling inhibitor WIKI4. PLoS One, 2013. 8(6): p. e65404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gunaydin H, Gu Y, and Huang X, Novel binding mode of a potent and selective tankyrase inhibitor. PLoS One, 2012. 7(3): p. e33740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y, et al. , Derivation of Pluripotent Stem Cells with In Vivo Embryonic and Extraembryonic Potency. Cell, 2017. 169(2): p. 243–257 e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang J, et al. , Establishment of mouse expanded potential stem cells. Nature, 2017. 550(7676): p. 393–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim H, et al. , Modulation of beta-catenin function maintains mouse epiblast stem cell and human embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nat Commun, 2013. 4: p.2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao X, et al. , Establishment of porcine and human expanded potential stem cells. Nat Cell Biol, 2019. 21(6): p. 687–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rostovskaya M, Stirparo GG, and Smith A, Capacitation of human naïve pluripotent stem cells for multi-lineage differentiation. Development, 2019. 146(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith S, et al. , Tankyrase, a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase at human telomeres. Science, 1998. 282(5393): p. 1484–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyons RJ, et al. , Identification of a novel human tankyrase through its interaction with the adaptor protein Grb14. J Biol Chem, 2001. 276(20): p. 17172–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monz D, et al. , Novel tankyrase-related gene detected with meningioma-specific sera. Clin Cancer Res, 2001. 7(1): p. 113–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuimov AN, et al. , Cloning and characterization of TNKL, a member of tankyrase gene family. Genes Immun, 2001. 2(1): p. 52–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiang YJ, et al. , Tankyrase 1 and tankyrase 2 are essential but redundant for mouse embryonic development. PLoS One, 2008. 3(7): p. e2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang W, Dynek JN, and Smith S, TRF1 is degraded by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis after release from telomeres. Genes Dev, 2003. 17(11): p. 1328–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhardwaj A, et al. , Whole proteome analysis of human tankyrase knockout cells reveals targets of tankyrase-mediated degradation. Nat Commun, 2017. 8(1): p. 2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith S and de Lange T, Cell cycle dependent localization of the telomeric PARP, tankyrase, to nuclear pore complexes and centrosomes. J Cell Sci, 1999. 112 (Pt 21): p. 3649–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang P, Coughlin M, and Mitchison TJ, Tankyrase-1 polymerization of poly(ADP-ribose) is required for spindle structure and function. Nat Cell Biol, 2005. 7(11): p. 1133–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang P, Coughlin M, and Mitchison TJ, Interaction between Poly(ADP-ribose) and NuMA contributes to mitotic spindle pole assembly. Mol Biol Cell, 2009. 20(21): p. 4575–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang W, Dynek JN, and Smith S, NuMA is a major acceptor of poly(ADPribosyl) ation by tankyrase 1 in mitosis. Biochem J, 2005. 391(Pt 2): p. 177–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dregalla RC, et al. , Regulatory roles of tankyrase 1 at telomeres and in DNA repair: suppression of T-SCE and stabilization of DNA-PKcs. Aging (Albany NY), 2010. 2(10): p. 691–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Broccoli D, et al. , Comparison of the human and mouse genes encoding the telomeric protein, TRF1: chromosomal localization, expression and conserved protein domains. Hum Mol Genet, 1997. 6(1): p. 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muramatsu Y, et al. , Cross-species difference in telomeric function of tankyrase 1. Cancer Sci, 2007. 98(6): p. 850–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sumi T, et al. , Epiblast ground state is controlled by canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in the postimplantation mouse embryo and epiblast stem cells. PLoS One, 2013. 8(5): p. e63378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li N, et al. , Poly-ADP ribosylation of PTEN by tankyrases promotes PTEN degradation and tumor growth. Genes Dev, 2015. 29(2): p. 157–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang W, et al. , Tankyrase Inhibitors Target YAP by Stabilizing Angiomotin Family Proteins. Cell Rep, 2015. 13(3): p. 524–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ciccarone F, Zampieri M, and Caiafa P, PARP1 orchestrates epigenetic events setting up chromatin domains. Semin Cell Dev Biol, 2017. 63: p. 123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wray J, et al. , Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 alleviates Tcf3 repression of the pluripotency network and increases embryonic stem cell resistance to differentiation. Nat Cell Biol, 2011. 13(7): p. 838–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsukiyama T and Ohinata Y, A modified EpiSC culture condition containing a GSK3 inhibitor can support germline-competent pluripotency in mice. PLoS One, 2014. 9(4): p. e95329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hanna J, et al. , Metastable pluripotent states in NOD-mouse-derived ESCs. Cell Stem Cell, 2009. 4(6): p. 513–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sugimoto M, et al. , A simple and robust method for establishing homogeneous mouse epiblast stem cell lines by wnt inhibition. Stem Cell Reports, 2015. 4(4): p. 744–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen B, et al. , Small molecule-mediated disruption of Wnt-dependent signaling in tissue regeneration and cancer. Nat Chem Biol, 2009. 5(2): p. 100–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu J, et al. , An alternative pluripotent state confers interspecies chimaeric competency. Nature, 2015. 521(7552): p. 316–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cong F and Varmus H, Nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of Axin regulates subcellular localization of beta-catenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2004. 101(9): p. 2882–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wiechens N, et al. , Nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of Axin, a negative regulator of the Wnt-beta-catenin Pathway. J Biol Chem, 2004. 279(7): p. 5263–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Henderson BR, Nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of APC regulates beta-catenin subcellular localization and turnover. Nat Cell Biol, 2000. 2(9): p. 653–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schmitz Y, Rateitschak K, and Wolkenhauer O, Analysing the impact of nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of beta-catenin and its antagonists APC, Axin and GSK3 on Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Cell Signal, 2013. 25(11): p. 2210–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krieghoff E, Behrens J, and Mayr B, Nucleo-cytopla smic distribution of beta-catenin is regulated by retention. J Cell Sci, 2006. 119(Pt 7): p. 1453–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Faunes F, et al. , A membrane-associated beta-catenin/Oct4 complex correlates with ground-state pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Development, 2013. 140(6): p. 1171–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Munoz Descalzo S, et al. , A competitive protein intera ction network buffers Oct4-mediated differentiation to promote pluripotency in embryonic stem cells. Mol Syst Biol, 2013. 9: p. 694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abu-Remaileh M, et al. , Oct-3/4 regulates stem cell identity and cell fate decisions by modulating Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. EMBO J, 2010. 29(19): p. 3236–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marucci L, et al. , beta-Catenin Fluctuates in Mouse ESCs and Is Essential for Nanog-Mediated Reprogramming of Somatic Cells to Pluripotency. Cell Rep, 2014. 8(6): p. 1686–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lian I, et al. , The role of YAP transcription coactivator in regulating stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genes Dev, 2010. 24(11): p. 1106–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beyer TA, et al. , Switch enhancers interpret TGF-beta and Hippo signaling to control cell fate in human embryonic stem cells. Cell Rep, 2013. 5(6): p. 1611–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morin-Kensicki EM, et al. , Defects in yolk sac vasculogenesis, chorioallantoic fusion, and embryonic axis elongation in mice with targeted disruption of Yap65. Mol Cell Biol, 2006. 26(1): p. 77–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nishioka N, et al. , The Hippo signaling pathway components Lats and Yap pattern Tead4 activity to distinguish mouse trophectoderm from inner cell mass. Dev Cell, 2009. 16(3): p. 398–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Leung CY and Zernicka-Goetz M, Angiomotin prevents pluripotent lineage differentiation in mouse embryos via Hippo pathway-dependent and - independent mechanisms. Nat Commun, 2013. 4: p. 2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim NG, et al. , E-cadherin mediates contact inhibition of proliferation through Hippo signaling-pathway components. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2011. 108(29): p. 11930–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Azzolin L, et al. , YAP/TAZ incorporation in the beta-catenin destruction complex orchestrates the Wnt response. Cell, 2014. 158(1): p. 157–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang XH, et al. , [Role of PTEN in mouse pre-implantation development]. Dongwuxue Yanjiu, 2011. 32(6): p. 647–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ueno S, Kono R, and Iwao Y, PTEN is required for the normal progression of gastrulation by repressing cell proliferation after MBT in Xenopus embryos. Dev Biol, 2006. 297(1): p. 274–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Di Cristofano A, et al. , Pten is essential for embryonic development and tumour suppression. Nat Genet, 1998. 19(4): p. 348–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen XL, et al. , Expression of phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten in mouse endometrium and its effect during blastocyst implantation. Sheng Li Xue Bao, 2008. 60(1): p. 119–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alva JA, et al. , Phosphatase and tensin homolog regulates the pluripotent state and lineage fate choice in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells, 2011. 29(12): p. 1952–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Menchero S, et al. , Transitions in cell potency during early mouse development are driven by Notch. Elife, 2019. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rayon T, et al. , Notch and hippo converge on Cdx2 to specify the trophectoderm lineage in the mouse blastocyst. Dev Cell, 2014. 30(4): p. 410–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nowotschin S, et al. , A bright single-cell resolution live imaging reporter of Notch signaling in the mouse. BMC Dev Biol, 2013. 13: p. 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lowell S, et al. , Notch promotes neural lineage entry by pluripotent embryonic stem cells. PLoS Biol, 2006. 4(5): p. e121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bernstein E, et al. , Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat Genet, 2003. 35(3): p. 215–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Murchison EP, et al. , Characterization of Dicer-deficient murine embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2005. 102(34): p. 12135–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pandolfini L, et al. , RISC-mediated control of selected chromatin regulators stabilizes ground state pluripotency of mouse embryonic stem cells. Genome Biol, 2016. 17(1): p. 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee YM, et al. , MicroRNA regulation via DNA methylation during the morula to blastocyst transition in mice. Mol Hum Reprod, 2012. 18(4): p. 184–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gu KL, et al. , Pluripotency-associated miR-290/302 family of microRNAs promote the dismantling of naive pluripotency. Cell Res, 2016. 26(3): p. 350–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Boroviak T, et al. , The ability of inner-cell-mass cells to self-renew as embryonic stem cells is acquired following epiblast specification. Nat Cell Biol, 2014. 16(6): p. 516–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Boroviak T, et al. , Lineage-Specific Profiling Delineates the Emergence and Progression of Naive Pluripotency in Mammalian Embryogenesis. Dev Cell, 2015. 35(3): p. 366–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Petropoulos S, et al. , Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals Linea ge and XChromosome Dynamics in Human Preimplantation Embryos. Cell, 2016. 165(4): p. 1012–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Morkel M, et al. , Beta-catenin regulates Cripto- and Wnt3-dependent gene expression programs in mouse axis and mesoderm formation. Development, 2003. 130(25): p. 6283–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nagaoka T, et al. , An evolving web of signaling networks regulated by Cripto-1. Growth Factors, 2012. 30(1): p. 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nagaoka T, et al. , Cripto-1 enhances the canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway by binding to LRP5 and LRP6 co-receptors. Cell Signal, 2013. 25(1): p. 178–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Blakeley P, et al. , Defining the three cell lineages of the human blastocyst by single-cell RNA-seq. Development, 2015. 142(20): p. 3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fiorenzano A, et al. , Cripto is essential to capture mouse epiblast stem cell and human embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Nat Commun, 2016. 7: p. 12589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Huang J, et al. , Association of telomere length with authentic pluripotency of ES/iPS cells. Cell Res, 2011. 21(5): p. 779–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Karlseder J, et al. , Targeted deletion reveals an essential function for the telomere length regulator Trf1. Mol Cell Biol, 2003. 23(18): p. 6533–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schneider RP, et al. , TRF1 is a stem cell marker and is essential for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Commun, 2013. 4: p. 1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Varela E, et al. , Different telomere-length dynamics at the inner cell mass versus established embryonic stem (ES) cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2011. 108(37): p. 15207–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Netzer C, et al. , SALL1, the gene mutated in Townes-Brocks syndrome, encodes a transcriptional repressor which interacts with TRF1/PIN2 and localizes to pericentromeric heterochromatin. Hum Mol Genet, 2001. 10(26): p. 3017–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ohishi T, et al. , TRF1 ensures the centromeric function of Aurora-B and proper chromosome segregation. Mol Cell Biol, 2014. 34(13): p. 2464–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sato A, et al. , Sall1, a causative gene for Townes-Brocks syndrome, enhances the canonical Wnt signaling by localizing to heterochromatin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2004. 319(1): p. 103–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Karantzali E, et al. , Sall1 regulates embryonic stem cell differentiation in association with nanog. J Biol Chem, 2011. 286(2): p. 1037–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Marion RM, et al. , TERRA regulate the transcriptional landscape of pluripotent cells through TRF1-dependent recruitment of PRC2. Elife, 2019. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dilley RL and Greenberg RA, ALTernative Telomere Maintenance and Cancer. Trends Cancer, 2015. 1(2): p. 145–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Liu L, et al. , Telomere lengthening early in development. Nat Cell Biol, 2007. 9(12): p. 1436–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yang J, et al. , Tet Enzymes Regulate Telomere Maintenance and Chromosomal Stability of Mouse ESCs. Cell Rep, 2016. 15(8): p. 1809–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zeng S, et al. , Telomerase-mediated telomere elongation from human blastocysts to embryonic stem cells. J Cell Sci, 2014. 127(Pt 4): p. 752–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tichy ED, et al. , Mouse embryonic stem cells, but not somatic cells, predominantly use homologous recombination to repair double-strand DNA breaks. Stem Cells Dev, 2010. 19(11): p. 1699–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Banuelos CA, et al. , Mouse but not human embryonic stem cells are deficient in rejoining of ionizing radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks. DNA Repair (Amst), 2008. 7(9): p. 1471–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bogomazova AN, et al. , Error-prone nonhomologous end joining repair operates in human pluripotent stem cells during late G2. Aging (Albany NY), 2011. 3(6): p. 584–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Maruyama T, et al. , Increasing the efficiency of precise genome editing with CRISPR-Cas9 by inhibition of nonhomologous end joining. Nat Biotechnol, 2015. 33(5): p. 538–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Vartak SV and Raghavan SC, Inhibition of nonhomologous end joining to increase the specificity of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. FEBS J, 2015. 282(22): p. 4289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Buecker C, et al. , A murine ESC-like state facilitates transgenesis and homologous recombination in human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell, 2010. 6(6): p. 535–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bai P, et al. , Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases as modulators of mitochondrial activity. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2015. 26(2): p. 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hottiger MO, et al. , Toward a unified nomenclature for mammalian ADPribosyltransferases. Trends Biochem Sci, 2010. 35(4): p. 208–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Leese HJ and Barton AM, Pyruvate and glucose uptake by mouse ova and preimplantation embryos. J Reprod Fertil, 1984. 72(1): p. 9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Houghton FD, et al. , Oxygen consumption and energy metabolism of the early mouse embryo. Mol Reprod Dev, 1996. 44(4): p. 476–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]