Key Points

Question

What percentage of children hospitalized with viral bronchiolitis who are not receiving any supplemental oxygen are continuously monitored with pulse oximetry?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study that included 56 hospitals and 3612 patient observations of children hospitalized with bronchiolitis without receipt of supplemental oxygen, pulse oximetry use ranged from 2% to 92%, with a mean of 46%.

Meaning

Continuous pulse oximetry monitoring among a sample of hospitalized children with bronchiolitis but without an apparent indication for its use had high prevalence.

Abstract

Importance

US national guidelines discourage the use of continuous pulse oximetry monitoring in hospitalized children with bronchiolitis who do not require supplemental oxygen.

Objective

Measure continuous pulse oximetry use in children with bronchiolitis.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A multicenter cross-sectional study was performed in pediatric wards in 56 US and Canadian hospitals in the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network from December 1, 2018, through March 31, 2019. Participants included a convenience sample of patients aged 8 weeks through 23 months with bronchiolitis who were not receiving active supplemental oxygen administration. Patients with extreme prematurity, cyanotic congenital heart disease, pulmonary hypertension, home respiratory support, neuromuscular disease, immunodeficiency, or cancer were excluded.

Exposures

Hospitalization with bronchiolitis without active supplemental oxygen administration.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome, receipt of continuous pulse oximetry, was measured using direct observation. Continuous pulse oximetry use percentages were risk standardized using the following variables: nighttime (11 pm to 7 am), age combined with preterm birth, time after weaning from supplemental oxygen or flow, apnea or cyanosis during the present illness, neurologic impairment, and presence of an enteral feeding tube.

Results

The sample included 3612 patient observations in 33 freestanding children's hospitals, 14 children's hospitals within hospitals, and 9 community hospitals. In the sample, 59% were male, 56% were white, and 15% were black; 48% were aged 8 weeks through 5 months, 28% were aged 6 through 11 months, 16% were aged 12 through 17 months, and 9% were aged 18 through 23 months. The overall continuous pulse oximetry monitoring use percentage in these patients, none of whom were receiving any supplemental oxygen or nasal cannula flow, was 46% (95% CI, 40%-53%). Hospital-level unadjusted continuous pulse oximetry use ranged from 2% to 92%. After risk standardization, use ranged from 6% to 82%. Intraclass correlation coefficient suggested that 27% (95% CI, 19%-36%) of observed variation was attributable to unmeasured hospital-level factors.

Conclusions and Relevance

In a convenience sample of children hospitalized with bronchiolitis who were not receiving active supplemental oxygen administration, monitoring with continuous pulse oximetry was frequent and varied widely among hospitals. Because of the apparent absence of a guideline- or evidence-based indication for continuous monitoring in this population, this practice may represent overuse.

This study characterizes use of continuous pulse oximetry monitoring in hospitalized children with bronchiolitis who do not require supplemental oxygen in Canadian and US hospitals.

Introduction

The implementation of continuous pulse oximetry (Spo2) monitoring has enabled timely detection of oxygen desaturation and improved outcomes in operating rooms1 and other high-risk settings2 over the past 50 years. Continuous monitoring use has since expanded to hospital wards without supporting evidence of benefit, likely because of perceptions that it improves safety with little downside.3

Acute viral bronchiolitis is the leading cause of infant hospitalization.4 Bronchiolitis hospital care is primarily supportive, including nasopharyngeal suctioning, nasogastric or intravenous fluids, and supplemental oxygen. Continuous Spo2 monitoring in children with bronchiolitis who do not require supplemental oxygen has been recognized as a form of medical overuse.5,6,7

Risks associated with continuous Spo2 monitoring in children with bronchiolitis include prolonged length of stay8,9,10,11; increased costs attributable to delayed discharge, supplemental oxygen, and oximeter probes12; and potential for iatrogenic harm.13 Monitor alarms also contribute to alarm fatigue among nurses, which is associated with delays in alarm response time.14,15

Appropriate use of continuous Spo2 monitoring in children with bronchiolitis is guided by an American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Clinical Practice Guideline5 and Society of Hospital Medicine Choosing Wisely recommendations.6 The American Academy of Pediatrics guideline states that “Clinicians may choose not to use continuous pulse oximetry for children with a diagnosis of bronchiolitis.” The Choosing Wisely recommendations state “Do not use continuous pulse oximetry routinely in children with acute respiratory illness unless they are on supplemental oxygen.”6

The primary objective of this study was to determine the extent of continuous Spo2 monitoring in a population in whom continuous monitoring is not indicated: hospitalized children with bronchiolitis who do not require supplemental oxygen. The primary hypothesis was that continuous Spo2 monitoring use would exceed 30% in the population specified above across sites. The 30% cut point was selected as a guide to inform the decision to subsequently perform a deimplementation trial.

Methods

Design

We performed a multicenter cross-sectional study using in-person observation to sample the practice of continuous Spo2 monitoring during bronchiolitis season (December 1, 2018, through March 31, 2019). An overview of this study’s protocol and the projects that will follow was previously published.16 The institutional review board at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia approved the study, and the remaining US sites established reliance agreements with the reviewing institutional review boards. Research ethics boards at the University of Calgary and The Hospital for Sick Children also reviewed and approved the study. All sites granted waivers of consent, assent, parental permission, and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization.

Setting

We performed this study in 56 US and Canadian hospitals in the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Network, an independent, hospital-based research network that aims to improve the health of and health care delivery to hospitalized children and their families. Member hospitals were categorized as freestanding children's hospitals (hospitals devoted entirely to the care of children that include a full range of pediatric subspecialty services), children's hospitals within hospitals (general medical hospitals that care mainly for adult patients and include a pediatric department offering a full range of pediatric subspecialty services), and community hospitals (general medical centers that care mainly for adult patients and include a pediatric department offering limited or no pediatric subspecialty services). We performed observations only of acute care pediatric inpatient units not classified as intensive care.

Patients

We included patients aged 8 weeks through 23 months. Eligible patients had an active primary diagnosis of bronchiolitis in the hospital chart and were not receiving any supplemental oxygen or nasal cannula flow (even with room air [21% fraction of inspired oxygen]) at the time of data collection. Although the majority of children with bronchiolitis receive supplemental oxygen at some point during their hospital admission, some require only supportive care for respiratory distress (eg, frequent nasal suctioning) or feeding difficulties (eg, intravenous fluids or nasogastric feedings).17 Included patients were cared for by generalist services. We excluded patients documented as having experienced premature or preterm birth without a numeric gestational age listed and those with documented extreme prematurity (<28 weeks’ gestation), cyanotic congenital heart disease, pulmonary hypertension, home oxygen or positive pressure ventilation requirement, tracheostomy, neuromuscular disease, immunodeficiency, or cancer.

Data Collection

Observational Rounds for Primary Outcome

Staff at each hospital performed observational rounds during the study period by walking to the bedside of each patient who met the inclusion criteria outlined above. Investigators determined the continuous monitoring status of the patients based on visual confirmation of waveforms and data displayed on the bedside monitor. Each site principal investigator used convenience sampling based on the availability of their data collection team to determine on which dates to perform observational rounds. We restricted observational rounds to occur only during certain hours, designated as “daytime” (10 am to 5 pm) or “nighttime” (11 pm to 7 am). We asked sites to aim to collect at least 60 observations during the bronchiolitis season, targeting approximately 50% of observations during nighttime hours. Weekends were not specifically targeted for data collection. The end cutoff of daytime hours was extended from 4 pm (as in the original protocol16) to 5 pm at the request of site principal investigators prior to the start of data collection to increase feasibility.

Although we did not collect patient identifiers, we required that each observational rounds data collection session be separated by at least 36 hours to limit within-patient repeated measures, given that the median length of stay for bronchiolitis is 2 days.18

Chart Review for Demographic and Clinical Variables (Covariates)

Following the in-person data collection, investigators reviewed patients’ charts for demographic and clinical information, including age; gestational age; previous respiratory support during the same hospitalization; presence of feeding tube; apnea or cyanosis during the present illness; prior intensive care unit stay during the present hospitalization; and the presence of conditions associated with neurologic impairment. Patient family-reported race and ethnicity were abstracted from charts in categories defined by the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity, in compliance with National Institutes of Health inclusion reporting policies.19 In addition to reporting, we planned to analyze race and ethnicity as variables possibly associated with continuous Spo2 monitoring, which could suggest important disparities in care based on race or ethnicity.

Analysis

We estimated the frequency of within-patient repeated measures by first generating a patient phenotype variable for each unique combination of hospital, unit, age category, gestational age category, race, ethnicity, sex, presence of gastrostomy, and neurologic impairment. Based on bronchiolitis length of stay data from a randomized trial,12 we considered observations of the same patient phenotype that were separated by less than 4 days (approximately the 75th percentile of length of stay in the trial’s usual care group) to possibly represent the same patient.

Because of the straightforward approach to data collection, with basic elements collected from the chart combined with in-person direct observation of monitoring, we expected only trivial amounts of missing data. However, we anticipated missing numeric gestational age documentation in some patients and designed the data collection form to accommodate this issue. If a numeric gestational age was not listed in the chart, the data collector reviewed the chart for qualitative descriptions of the patient as “full term,” “premature,” or “preterm.” Patients described as premature or preterm in the absence of a documented gestational age were assumed to be born prior to 28 weeks and were excluded. Those described as full term or without a qualitative description of gestational age were included. In the analysis, we dichotomized included patients as preterm (28 0/7 to 33 6/7 weeks documented in the chart) or not preterm. We did not perform imputation or use any other methods to replace missing data with values.

We calculated the unadjusted observed continuous Spo2 monitoring use percentage for each hospital as a simple percentage of the total number of observations during which patients were continuously monitored divided by the total number of observations performed at that hospital, comprised exclusively of patients not receiving any supplemental oxygen or nasal cannula flow. We estimated the 95% CI of the unadjusted monitoring percentage accounting for clustering at the hospital level using linear regression with a sandwich estimator for the standard errors allowing for intrahospital correlation (Stata “regress” command with “vce cluster” option). We performed a 1-sample test of this percentage against the hypothesized percentage of 30%, specifying a conservative intraclass correlation of 40% to account for the hospital-level clustering (Stata “prtest” command with “cluster” and “rho” options).

We then examined the bivariable associations of the chart-abstracted demographic and clinical covariates listed above with continuous monitoring use using fixed-effects logistic regression. Given that gestational age and chronological age are often considered in combination when thinking about risk in clinical practice, we used dichotomous preterm status and categorical chronological age jointly as an interaction term in all models (categories shown in Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of Sampled Patients With Bronchiolitis Not Receiving Any Supplemental Oxygen or Nasal Cannula Flow.

| Variable | Patient observations, No. (%)a |

|---|---|

| Patient demographics | |

| Age | |

| 8 wk-5 mo | 1742 (48) |

| 6-11 mo | 1001 (28) |

| 12-17 mo | 560 (16) |

| 18-23 mo | 309 (9) |

| Gestational age | |

| Preterm (28 0/7 to 33 6/7 wk documented in the chart) | 361 (10) |

| Not pretermb | 3251 (90) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 2125 (59) |

| Female | 1485 (41) |

| Not specified | 2 (<1) |

| Racec | |

| White | 2034 (56) |

| Black or African American | 553 (15) |

| Specified as “other” | 500 (14) |

| Specified as “unknown” | 279 (8) |

| Asian | 144 (4) |

| More than 1 race | 56 (2) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 30 (1) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 16 (<1) |

| Ethnicityc | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 2454 (68) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 766 (21) |

| Unknown | 259 (7) |

| Other | 133 (4) |

| Illness characteristics at time of observation | |

| Time since weaning from supplemental oxygen or flow, h | |

| Never received | 1190 (33) |

| <1 | 80 (2) |

| 1-<2 | 148 (4) |

| 2-<4 | 244 (7) |

| 4-<6 | 234 (6) |

| 6-<12 | 505 (14) |

| 12-<24 | 687 (19) |

| ≥24 | 499 (14) |

| Unknown | 25 (<1) |

| Prior intensive care unit stay during present hospitalization | 884 (24) |

| Apnea or cyanosisd | 235 (7) |

| Comorbid condition associated with neurologic impairmente | 93 (3) |

| Enteral feeding tube (nasogastric or gastrostomy) | 305 (8) |

| Hospital typef | |

| Freestanding children’s hospital (n = 33) | 2667 (74) |

| Children's hospital within hospital (n = 14) | 591 (16) |

| Community hospital (n = 9) | 354 (10) |

| Time of day observation performed | |

| Day (10 am to 5 pm) | 2073 (57) |

| Night (11 pm to 7 am) | 1539 (43) |

For some variables, the sum of percentages does not equal 100% because of rounding.

Not preterm included the following: documented gestational age 34 0/7 weeks and above, absence of gestational age but documented as full term, or absence of gestational age but not labeled in chart as preterm or premature.

Patient family-reported race and ethnicity were abstracted from charts in categories defined by the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity, in compliance with National Institutes of Health inclusion reporting policies.

Includes documentation of apnea or cyanosis occurring at home or in the hospital during the present illness.

Static encephalopathy, cerebral palsy, hydrocephalus, spina bifida, epilepsy/seizure disorder, or hypotonia.

Median (interquartile range) number of observations was 70 (61-95) for freestanding children’s hospitals, 38 (24-62) for children’s hospitals within a hospital, and 35 (29-57) for community hospitals.

We also performed multivariable analyses to compare hospitals’ monitoring percentages in a standardized way, accounting for differences in the patient-level variables potentially associated with monitoring. The purpose of this risk standardization was to approximate what we would have found if we hospitalized a similar cohort of infants in each of the hospitals and to permit identification of statistical outlier hospitals. We chose this approach because we anticipated that patient-level factors associated with use would differ between sites due to site-level differences in patient populations with different degrees of risk20,21,22,23 and differences in sampling. To do this, we used methods developed for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for public reporting of hospital quality based on administrative data.24,25 These methods adjust for case-mix differences among hospitals using patient-level factors, thus permitting comparison of hospital performance.25 This approach also assumes that there are underlying differences between hospitals, allowing us to distinguish within-hospital variation from between-hospital variation in continuous Spo2 monitoring use.26

For each hospital, we first calculated the expected continuous Spo2 monitoring use percentage given the hospital-specific differences in case mix using patient-level variables. We used a fixed-effects multivariable logistic regression model that included the covariates that met the prespecified criteria of having composite P values less than .20 for being continuously Spo2 monitored in the model described above. We retained variables in this model with P values that remained less than .20 when included in the multivariable model. This expected use percentage estimates the monitoring percentage if the set of patients observed at this hospital were treated at the average hospital.26

We then calculated the predicted use percentage for each hospital by incorporating the hospital-specific random effect into the multivariable fixed-effects model (resulting in the final mixed-effects regression model that accounts for hospital-level clustering). We computed a risk-standardized monitoring percentage for each hospital as the ratio of the predicted to expected use percentages multiplied by the unadjusted overall percentage across all hospitals. We constructed percentile-based 95% CIs for the risk-standardized percentages of each hospital based on 1000 samples.25,26 We considered hospitals to be “statistical high-use outliers” if the lower bound of the 95% CI was higher than the overall observed monitoring percentage and “statistical low-use outliers” if the upper bound of the 95% CI was lower than the overall percentage.25 We excluded hospitals that submitted fewer than 20 observations from the hospital comparisons.

We used data collection forms designed in REDCap and hosted centrally at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.27 We used SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC) for analysis. We used publicly available statistical code in the 2018 CMS Mortality Measures SAS pack to calculate the risk-standardized monitoring percentage for each hospital and to construct percentile-based 95% CIs. Statistical significance was defined as 2-sided P < .05.

Results

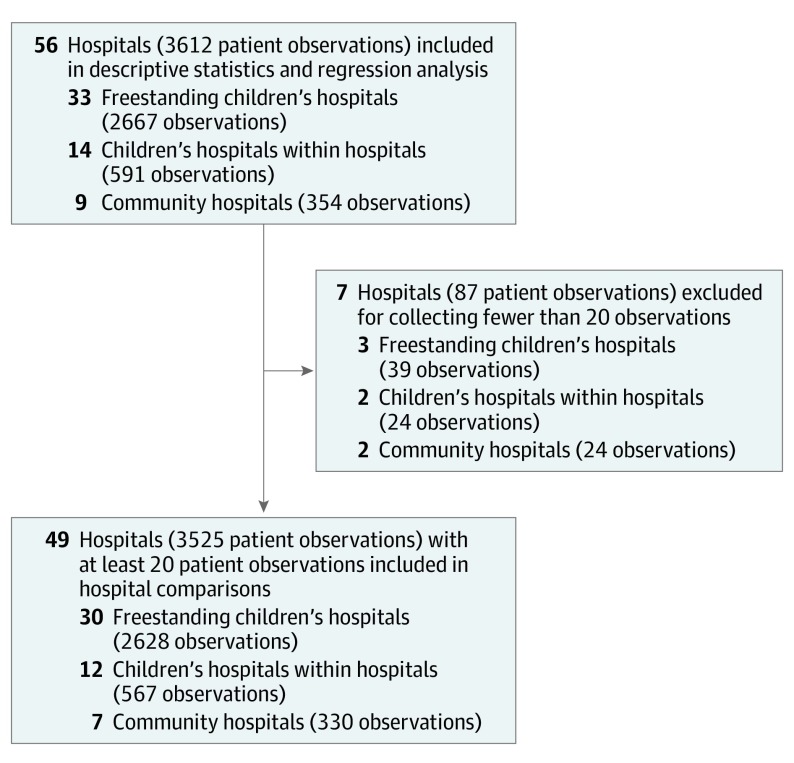

We conducted 3612 patient observations in 33 freestanding children's hospitals, 14 children's hospitals within hospitals, and 9 community hospitals during the 4-month study period (Figure 1). Seven hospitals collected fewer than 20 observations and were excluded from hospital comparisons. Of the 49 hospitals with at least 20 observations, the median (interquartile range) number of observations per hospital was 63 (50-89). Two hospitals were in Canada and the remainder were in the US.

Figure 1. Flow of Hospitals and Patient Observations in a Study of the Prevalence of Continuous Pulse Oximetry Monitoring in Hospitalized Children With Bronchiolitis Not Requiring Supplemental Oxygen.

The study population of children with bronchiolitis was 59% male, 56% white, 15% black, and 21% Hispanic or Latino; 48% were aged 8 weeks through 5 months, 28% were aged 6 through 11 months, 16% were aged 12 through 17 months, and 9% were aged 18 through 23 months. Overall, 66% of patients received supplemental oxygen or flow earlier during their current admission. Investigators performed 43% of observations during nighttime hours (11 pm to 7 am). Ten percent of observations had another observation of the same patient phenotype in the preceding 4 days. Other patient characteristics are included in Table 1.

In the included patients with bronchiolitis, none of whom were receiving any supplemental oxygen or nasal cannula flow at the time of data collection, the overall percentage with continuous Spo2 monitoring use, accounting for clustering at the hospital level, was 46% ([95% CI, 40%-53%]; 2-sided P < .001), rejecting the null hypothesis. Of the 49 hospitals that collected at least 20 observations, the hospital-level unadjusted continuous Spo2 monitoring use percentages ranged from 2% to 79% for the 30 freestanding children’s hospitals (hospital-level median, 40%), from 7% to 92% for the 12 children’s hospitals within hospitals (hospital-level median, 58%), and from 22% to 77% for the 7 community hospitals (hospital-level median, 48%).

In unadjusted fixed-effects analyses, the following variables met the prespecified criteria to be included in the multivariable model: nighttime, age combined with preterm birth, time after weaning from supplemental oxygen or flow, documented history of apnea or cyanosis during the present illness, neurologic impairment, and presence of an enteral feeding tube (Table 2). Ethnicity met initial criteria to enter the multivariable model based on having a bivariable association P value less than .20 but was eliminated from the multivariable model for having a composite P value of 0.34.

Table 2. Continuous Pulse Oximetry Use in Patients With Bronchiolitis Not Receiving Any Supplemental Oxygen or Nasal Cannula Flow.

| Variable | No. of patients continuously monitored with pulse oximetry/total No. (%) | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) for use of continuous pulse oximetry | P value | OR (95% CI) for use of continuous pulse oximetry | P value | ||||

| Category | Compositea | Category | Compositea | ||||

| Overall (n = 56 hospitals) | 1679/3612 (46) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Agec | .11 | <.001 | |||||

| 8 wk-5 mo | |||||||

| Preterm | 103/183 (56) | 1.78 (1.12-2.83) | .02 | 2.58 (1.65-4.02) | <.001 | ||

| Not preterm | 758/1559 (49) | 1.31 (1.03-1.66) | .03 | 1.51 (1.12-2.03) | .007 | ||

| 6-11 mo | |||||||

| Preterm | 47/107 (44) | 1.08 (0.74-1.59) | .68 | 1.21 (0.72-2.05) | .48 | ||

| Not preterm | 402/894 (45) | 1.13 (0.89-1.43) | .31 | .14 | |||

| 12-17 mo | |||||||

| Preterm | 20/48 (42) | 0.99 (0.52-1.86) | .97 | 0.77 (0.38-1.58) | .48 | ||

| Not preterm | 219/512 (43) | 1.03 (0.74-1.45) | .85 | 1.01 (0.72-1.42) | .95 | ||

| 18-23 mo | |||||||

| Preterm | 10/23 (43) | 1.06 (0.46-2.47) | .89 | 0.50 (0.18-1.37) | .18 | ||

| Not preterm | 120/286 (42) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Sex | .52 | Not includedb | |||||

| Male | 977/2125 (46) | 1 [Reference] | |||||

| Female | 702/1485 (47) | 1.05 (0.90-1.23) | .52 | ||||

| Raced | .61 | Not includedb | |||||

| White | 938/2034 (46) | 1 [Reference] | |||||

| Other | 502/1025 (49) | 1.12 (0.82-1.53) | .47 | ||||

| Black or African American | 239/553 (43) | 0.90 (0.62-1.28) | .53 | ||||

| Ethnicityd | .11 | Not includedb | |||||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 1088/2454 (44) | 1 [Reference] | |||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 410/766 (54) | 1.45 (1.05-1.98) | .02 | ||||

| Unknown | 123/259 (48) | 1.14 (0.77-1.68) | .53 | ||||

| Other | 58/133 (44) | 0.97 (0.62-1.51) | .90 | ||||

| Time since weaning from supplemental oxygen or flow, he | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| Never received | 442/1190 (37) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| <1 | 59/80 (74) | 4.75 (1.90-11.93) | .001 | 5.01 (2.76-9.07) | <.001 | ||

| 1-<2 | 108/148 (73) | 4.57 (2.50-8.35) | <.001 | 5.97 (3.84-9.30) | <.001 | ||

| 2-<4 | 166/244 (68) | 3.60 (2.31-5.61) | <.001 | 5.55 (3.91-7.89) | <.001 | ||

| 4-<6 | 135/234 (58) | 2.31 (1.49-3.58) | <.001 | 2.96 (2.13-4.13) | <.001 | ||

| 6-<12 | 276/505 (55) | 2.04 (1.42-2.93) | <.001 | 2.12 (1.65-2.72) | <.001 | ||

| 12-<24 | 302/687 (44) | 1.33 (0.98-1.80) | .07 | 1.16 (0.93-1.45) | .20 | ||

| ≥24 | 179/499 (36) | 0.95 (0.68-1-31) | .74 | 0.75 (0.58-0.97) | .03 | ||

| Intensive care unit stay during present hospitalization | .54 | Not includedb | |||||

| Yes | 424/884 (48) | 1.08 (0.84-1.39) | .54 | ||||

| No | 1255/2728 (46) | 1 [Reference] | |||||

| Apnea or cyanosisf | .02 | .04 | |||||

| Yes | 128/235 (54) | 1.41 (1.07-1.86) | .02 | 1.40 (1.01-1.93) | .04 | ||

| No | 1551/3377 (46) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Comorbid condition associated with neurologic impairmentg | .08 | .10 | |||||

| Yes | 51/93 (55) | 1.41 (0.96-2.06) | .08 | 1.50 (0.93-2.43) | .10 | ||

| No | 1628/3519 (46) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Enteral feeding tube in placeh | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 176/305 (58) | 1.64 (1.23-2.17) | <.001 | 1.98 (1.46-2.67) | <.001 | ||

| No | 1503/3307 (45) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Hospital type | .58 | Not includedb | |||||

| Freestanding children’s hospital (n = 33) | 1198/2667 (45) | 1 [Reference] | |||||

| Children's hospital within hospital (n = 14) | 317/591 (54) | 1.42 (0.74-2.73) | .29 | ||||

| Community hospital (n = 9) | 164/354 (46) | 1.06 (0.55-2.02) | .86 | ||||

| Time of day observation performed | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| Day (10 am to 5 pm) | 870/2073 (42) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Night (11 pm to 7 am) | 809/1539 (53) | 1.53 (1.27-1.85) | <.001 | 2.07 (1.76-2.43) | <.001 | ||

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

In variables with multiple categories, composite P value was obtained using the Wald test.

The following variables met the prespecified criteria to be included in the multivariable model: age and gestational age category, time since weaning from supplemental oxygen or flow, apnea or cyanosis, comorbid condition associated with neurologic impairment, enteral feeding tube, and time of day observation was performed. Ethnicity met initial criteria to enter the model based on having a bivariable association composite P value less than .20 but was eliminated from the multivariable model for a composite P value of .34.

Not preterm included the following: documented gestational age 34 0/7 weeks and above, absence of gestational age but documented as full term, or absence of gestational age but not labeled in chart as preterm or premature.

Patient family-reported race and ethnicity were abstracted from charts in categories defined by the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity, in compliance with National Institutes of Health inclusion reporting policies. In this Table, “other” race includes all of the following categories: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, specified as more than one race, specified as other, and specified as unknown.

Individuals with unknown time since weaning (n = 25) are not included.

Includes documentation of apnea or cyanosis occurring at home or in the hospital during the present illness.

Static encephalopathy, cerebral palsy, hydrocephalus, spina bifida, epilepsy/seizure disorder, or hypotonia.

Nasogastric or gastrostomy.

In the final adjusted mixed-effects regression analysis (Table 2), the following variables were significantly associated with continuous Spo2 monitoring: age combined with preterm birth (eg, odds ratio [OR] of children aged 8 wk through 5 mo and born preterm, 2.58 [95% CI, 1.65-4.02]; P < .001 relative to reference group of children aged 18 through 23 mo and not born preterm), time since weaning from supplemental oxygen or flow (eg, OR of patients who had not received supplemental oxygen for the past 2-<4 h, 5.55 [95% CI, 3.91-7.89]; P < .001 relative to reference group of patients who never received supplemental oxygen or flow), documented history of apnea or cyanosis during the present illness (OR, 1.40 [95% CI, 1.01-1.93]; P = .041), presence of an enteral feeding tube (OR, 1.98 [95% CI, 1.46-2.67]; P < .001), and nighttime (OR, 2.07 [95% CI, 1.76-2.43]; P < .001).

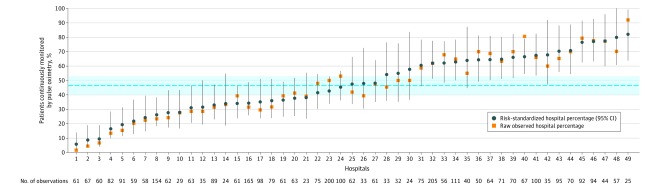

Risk-standardized percentages of continuous Spo2 monitoring use ranged from 6% to 82% (Figure 2). Seventeen hospitals were statistical high-use outliers (9 freestanding children’s hospitals, 6 children's hospitals within hospitals, and 2 community hospitals) and 10 hospitals were statistical low-use outliers (6 freestanding children’s hospitals, 2 children's hospitals within hospitals, and 2 community hospitals). The adjusted model’s intraclass correlation coefficient suggested that 27% (95% CI, 19%-36%) of the observed variation was attributable to unmeasured hospital level factors.

Figure 2. Continuous Pulse Oximetry Use in Patients With Bronchiolitis Not Receiving Any Supplemental Oxygen or Nasal Cannula Flow .

Patients were aged 8 weeks through 23 months. Points represent the percentage of patients with bronchiolitis actively monitored with continuous pulse oximetry, measured using direct observation. The dotted blue line indicates overall percentage across all hospitals and the shaded area represents the 95% CI. The risk-standardized percentage for each hospital is the ratio of the predicted to expected use percentages multiplied by the overall percentage across all hospitals. Hospitals are ordered by risk-standardized percentage of patients monitored.

Discussion

In this multicenter cross-sectional study involving a convenience sample of children hospitalized with bronchiolitis who were not actively receiving supplemental oxygen, continuous Spo2 monitoring occurred frequently, and this practice varied widely among hospitals.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to measure continuous Spo2 monitoring use in patients with bronchiolitis using direct observation. In a multicenter pediatric quality improvement collaborative, use of continuous Spo2 monitoring in patients with bronchiolitis not receiving supplemental oxygen was assumed if an active monitoring order existed at the time the patient was discharged, but the investigators did not measure the use of continuous Spo2 monitoring at other points in the hospitalization.28 A single-center quality improvement project targeting length of stay reduction in individuals with bronchiolitis also used orders as a measure of continuous vs intermittent Spo2 monitoring practice.11 Neither project validated the presence of orders against actual monitoring at the bedside. A second single-center quality improvement project identified continuous Spo2 monitoring status in children with wheezing by examining monitor data that was directly integrated into the electronic health record to quantify time undergoing continuous Spo2 monitoring after patients were weaned to receive albuterol treatments every 2 hours or off supplemental oxygen to room air.29

The current study provides evidence suggesting continuous Spo2 monitoring overuse in children with bronchiolitis, despite national guidelines discouraging its use in this population, and has additional broader implications. Recent estimates suggested that the total cost of waste from overtreatment or low-value care in the US ranges from $75.7 billion to $101.2 billion.30 Since the publication of a landmark 2010 article challenging medical specialty societies to create “top 5” lists of frequently ordered tests or treatments that provide little benefit,31 attention to minimizing the use of low-value, ineffective, or unproven health care practices increased.32,33,34 There is an emerging science of deimplementation, the systematic, structured reduction or elimination of low-value care practices, that may inform efforts to reduce monitoring overuse.35,36 This project represents essential first steps in deimplementing an overused low-value care practice: measuring “baseline” or “usual care” practices, measuring contextual contributors to overuse, and identifying outlier sites to begin the process of assessing barriers and facilitators to deimplementation.37

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it is possible that the convenience sampling approach resulted in a sample not representative of the entire population of stable patients with bronchiolitis. This pragmatic approach was necessary to include a diverse set of hospitals, many of which had limited resources for data collection. However, because data collectors were physicians and nurses at some hospitals, it is possible that during very high-census days in the hospital, those individuals were required to provide direct patient care and thus were unavailable to collect data. If monitor use was more prevalent during high-census days, this convenience sampling approach would have biased our findings toward the null. As physiologic monitoring data become more easily accessible, it is likely that future studies will determine continuous monitoring status using electronic health record data only, eliminating the need for in-person data collection. Second, freestanding children’s hospitals were overrepresented in the sample. There is a need to include more community hospitals in research because less than 30% of pediatric hospitalizations in the US occur in freestanding children’s hospitals.38 Third, the relationships of other hospital-level factors (eg, presence of clinical pathways [which have been shown to improve quality of care and reduce overuse in pediatric asthma],39 characteristics of the nurse work environment associated with patient safety40) and other patient-level factors (eg, work of breathing, respiratory rate, other comorbidities) were not analyzed in this study but might contribute to continuous Spo2 monitoring use. Fourth, because observers only visited each bedside once during data collection rounds, it is possible that some patients were classified as being continuously monitored at time points when they were actually having intermittent vital sign measurements. Fifth, no data were available to determine whether actions were taken to change monitoring practice during the study period in response to occurrence of the observational data collection rounds. Actively changing individual practice was discouraged by requiring that the data collectors not be simultaneously involved in the care of the patients whose data were being collected. Actively changing group practice (eg, at the unit or department level) in response to feedback of continuous Spo2 use results was prevented by hosting and managing the REDCap database centrally. Individual sites had data entry access only and could not generate reports or download their raw data. Continuous Spo2 use data were shared with hospitals after the data collection period ended. Sixth, the statistical analysis accounted for clustering at the hospital level but could not account for patient, nurse, or physician clustering due to limitations of the data collected.

Conclusions

In a convenience sample of children hospitalized with bronchiolitis not receiving active supplemental oxygen administration, continuous Spo2 monitoring was frequent and varied widely among hospitals. Because of the apparent absence of a guideline- or evidence-based indication for continuous monitoring in this population, this practice may represent overuse.

References

- 1.Cullen DJ, Nemeskal AR, Cooper JB, Zaslavsky A, Dwyer MJ. Effect of pulse oximetry, age, and ASA physical status on the frequency of patients admitted unexpectedly to a postoperative intensive care unit and the severity of their anesthesia-related complications. Anesth Analg. 1992;74(2):181-188. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199202000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ochroch EA, Russell MW, Hanson WC III, et al. The impact of continuous pulse oximetry monitoring on intensive care unit admissions from a postsurgical care floor. Anesth Analg. 2006;102(3):868-875. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000195583.76486.c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watkins T, Whisman L, Booker P. Nursing assessment of continuous vital sign surveillance to improve patient safety on the medical/surgical unit. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(1-2):278-281. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasegawa K, Tsugawa Y, Brown DFM, Mansbach JM, Camargo CA Jr. Trends in bronchiolitis hospitalizations in the United States, 2000-2009. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):28-36. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ralston SL, Lieberthal AS, Meissner HC, et al. ; American Academy of Pediatrics . Clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):e1474-e1502. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinonez RA, Garber MD, Schroeder AR, et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479-485. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quinonez RA, Coon ER, Schroeder AR, Moyer VA. When technology creates uncertainty: pulse oximetry and overdiagnosis of hypoxaemia in bronchiolitis. BMJ. 2017;358:j3850. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunningham S, Rodriguez A, Adams T, et al. ; Bronchiolitis of Infancy Discharge Study (BIDS) group . Oxygen saturation targets in infants with bronchiolitis (BIDS): a double-blind, randomised, equivalence trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9998):1041-1048. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00163-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroeder AR, Marmor AK, Pantell RH, Newman TB. Impact of pulse oximetry and oxygen therapy on length of stay in bronchiolitis hospitalizations. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(6):527-530. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.6.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham S, McMurray A. Observational study of two oxygen saturation targets for discharge in bronchiolitis. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(4):361-363. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.205211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mittal S, Marlowe L, Blakeslee S, et al. Successful use of quality improvement methodology to reduce inpatient length of stay in bronchiolitis through judicious use of intermittent pulse oximetry. Hosp Pediatr. 2019;9(2):73-78. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2018-0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham S, Rodriguez A, Boyd KA, McIntosh E, Lewis SC; BIDS Collaborators Group . Bronchiolitis of Infancy Discharge Study (BIDS): a multicentre, parallel-group, double-blind, randomised controlled, equivalence trial with economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(71):i-xxiii, 1-172. doi: 10.3310/hta19710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McBride SC, Chiang VW, Goldmann DA, Landrigan CP. Preventable adverse events in infants hospitalized with bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):603-608. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonafide CP, Lin R, Zander M, et al. Association between exposure to nonactionable physiologic monitor alarms and response time in a children’s hospital. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):345-351. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonafide CP, Localio AR, Holmes JH, et al. Video analysis of factors associated with response time to physiologic monitor alarms in a children’s hospital. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(6):524-531. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.5123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasooly IR, Beidas RS, Wolk CB, et al. ; Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network . Measuring overuse of continuous pulse oximetry in bronchiolitis and developing strategies for large-scale deimplementation: study protocol for a feasibility trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019;5(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s40814-019-0453-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unger S, Cunningham S. Effect of oxygen supplementation on length of stay for infants hospitalized with acute viral bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):470-475. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Cleve WC, Christakis DA. Unnecessary care for bronchiolitis decreases with increasing inpatient prevalence of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):e1106-e1112. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NIH policy and guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research. National Institutes of Health website. Updated December 6, 2017. Accessed January 27, 2020. https://grants.nih.gov/policy/inclusion/women-and-minorities/guidelines.htm

- 20.Schroeder AR, Mansbach JM, Stevenson M, et al. Apnea in children hospitalized with bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):e1194-e1201. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker MJ, Allen U, Stephens D, Lalani A, Schuh S. Predictors of major intervention in infants with bronchiolitis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44(4):358-363. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freire G, Kuppermann N, Zemek R, et al. ; Pediatric Emergency Research Networks (PERN) . Predicting escalated care in infants with bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2018;142(3):e20174253. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schuh S, Kwong JC, Holder L, Graves E, Macdonald EM, Finkelstein Y. Predictors of critical care and mortality in bronchiolitis after emergency department discharge. J Pediatr. 2018;199:217-222.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Mattera JA, et al. An administrative claims model suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day mortality rates among patients with an acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2006;113(13):1683-1692. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.611186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mortality measures. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Published March 2019. Accessed February 1, 2020. https://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier4&cid=1163010421830

- 26.Lagu T, Pekow PS, Stefan MS, et al. Derivation and validation of an in-hospital mortality prediction model suitable for profiling hospital performance in heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(4):e005256. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.005256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ralston SL, Garber MD, Rice-Conboy E, et al. ; Value in Inpatient Pediatrics Network Quality Collaborative for Improving Hospital Compliance with AAP Bronchiolitis Guideline (BQIP) . A multicenter collaborative to reduce unnecessary care in inpatient bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):e20150851. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schondelmeyer AC, Simmons JM, Statile AM, et al. Using quality improvement to reduce continuous pulse oximetry use in children with wheezing. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):e1044-e1051. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US health care system: estimated costs and potential for savings. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-1509. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.13978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brody H. Medicine’s ethical responsibility for health care reform—the top five list. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(4):283-285. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing Wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1801-1802. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morgan DJ, Brownlee S, Leppin AL, et al. Setting a research agenda for medical overuse. BMJ. 2015;351:h4534. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coon ER, Quinonez RA, Morgan DJ, et al. 2018 Update on pediatric medical overuse: a review. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(4):379-384. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Bodegom-Vos L, Davidoff F, Marang-van de Mheen PJ. Implementation and de-implementation: two sides of the same coin? BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(6):495-501. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Norton WE, Chambers DA, Kramer BS. Conceptualizing de-implementation in cancer care delivery. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(2):93-96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niven DJ, Mrklas KJ, Holodinsky JK, et al. Towards understanding the de-adoption of low-value clinical practices: a scoping review. BMC Med. 2015;13:255. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0488-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leyenaar JK, Ralston SL, Shieh M-S, Pekow PS, Mangione-Smith R, Lindenauer PK. Epidemiology of pediatric hospitalizations at general hospitals and freestanding children’s hospitals in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):743-749. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaiser SV, Rodean J, Bekmezian A, et al. ; Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network . Effectiveness of pediatric asthma pathways for hospitalized children: a multicenter, national analysis. J Pediatr. 2018;197:165-171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.01.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lake ET, Roberts KE, Agosto PD, et al. The association of the nurse work environment and patient safety in pediatric acute care. J Patient Saf. Published online December 28, 2018. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]