Abstract

Angelicin, a member of the furocoumarin group, is related to psoralen which is well known for its effectiveness in phototherapy. The furocoumarins as a group have been studied since the 1950s but only recently has angelicin begun to come into its own as the subject of several biological studies. Angelicin has demonstrated anti-cancer properties against multiple cell lines, exerting effects via both the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways, and also demonstrated an ability to inhibit tubulin polymerization to a higher degree than psoralen. Besides that, angelicin too demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity in inflammatory-related respiratory and neurodegenerative ailments via the activation of NF-κB pathway. Angelicin also showed pro-osteogenesis and pro-chondrogenic effects on osteoblasts and pre-chondrocytes respectively. The elevated expression of pro-osteogenic and chondrogenic markers and activation of TGF-β/BMP, Wnt/β-catenin pathway confirms the positive effect of angelicin bone remodeling. Angelicin also increased the expression of estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) in osteogenesis. Other bioactivities, such as anti-viral and erythroid differentiating properties of angelicin, were also reported by several researchers with the latter even displaying an even greater aptitude as compared to the commonly prescribed drug, hydroxyurea, which is currently on the market. Apart from that, recently, a new application for angelicin against periodontitis had been studied, where reduction of bone loss was indirectly caused by its anti-microbial properties. All in all, angelicin appears to be a promising compound for further studies especially on its mechanism and application in therapies for a multitude of common and debilitating ailments such as sickle cell anaemia, osteoporosis, cancer, and neurodegeneration. Future research on the drug delivery of angelicin in cancer, inflammation and erythroid differentiation models would aid in improving the bioproperties of angelicin and efficacy of delivery to the targeted site. More in-depth studies of angelicin on bone remodeling, the pro-osteogenic effect of angelicin in various bone disease models and the anti-viral implications of angelicin in periodontitis should be researched. Finally, studies on the binding of angelicin toward regulatory genes, transcription factors, and receptors can be done through experimental research supplemented with molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation.

Keywords: angelicin, psolaren, furocoumarin, biological activities, biological potential

Introduction

The use of plants as traditional medicine is common and has prevailed in many different cultures over time. Despite a lack of formal scientific evidence, the belief in the knowledge, traditions, and religious practices that endorse this is strong enough to have sustained this practice over the generations. It seems unlikely that these practices would have persisted for so long in the complete absence of beneficial effects. This suggests plants already used in traditional medicine represent an excellent start point in research to discover new, effective drugs to treat various human illnesses including cancer, bacterial infections, and cardiovascular disease, to name a few. The market trends which have shifted toward a demand for greener, cost-saving, and sustainable sources also created a drive to pursue plant bioprospecting; plants are easily obtained from the environment and are therefore regarded as a cheaper and safer source for consumers (Chandra, 2014).

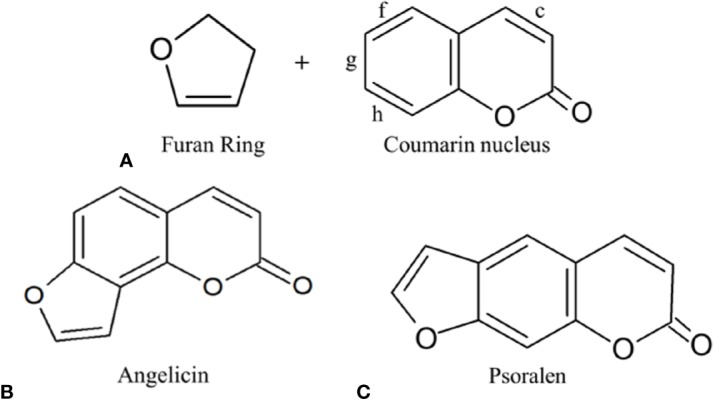

Among the compounds that have emerged from plant bioprospecting studies are the furocoumarin family of compounds that have been researched since the 1950s (Bordin et al., 1991). They are a family of natural active compounds that can be found in many different plants, vegetables and fruits we consume like parsnips, celery, figs, etc (Chaudhary et al., 1985; Lohman and McConnaughay, 1998; Marrelli et al., 2012). These compounds are mainly produced under stressful conditions as a self-defence mechanism against insect predation, fungal invasion, and bacterial attack. For example, celery infected with the fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum before storage has been found to have increased expression of furocoumarins—such as psoralen, 5-methoxypsoralen (5-MOP) and 8-methoxypsoralen (8-MOP)—as a response toward the fungal invasion (Chaudhary et al., 1985). Other studies showed that furocoumarins also displayed anti-feeding properties against insects and inhibition toward bacterial invasion (Yajima and Munakata, 1979; Berenbaum et al., 1991; Raja et al., 2011). The main skeletal structure of furocoumarin compounds encompasses a coumarin unit fused with a furan ring. The varying derivatives of furocoumarins can be formed by the fusing of the furan ring in either 2, 3- or 3,2- arrangements on the c, f, g, or h bonds of the coumarin unit as can be seen in Figure 1 (Santana et al., 2004; Kitamura and Otsubo, 2012). Among the many isomeric derivatives of the furocoumarins, the most commonly reported furocoumarins isomeric forms are linear and angular furocoumarins, with psoralen and angelicin being the most well-known of its isomers respectively (Munakata et al., 2016).

Figure 1.

(A) Furocoumarin's several different possible attachments of the furan ring on the coumarin nucleus; (B) Angular furocoumarin: Angelicin; (C) Linear furocoumarin: Psoralen.

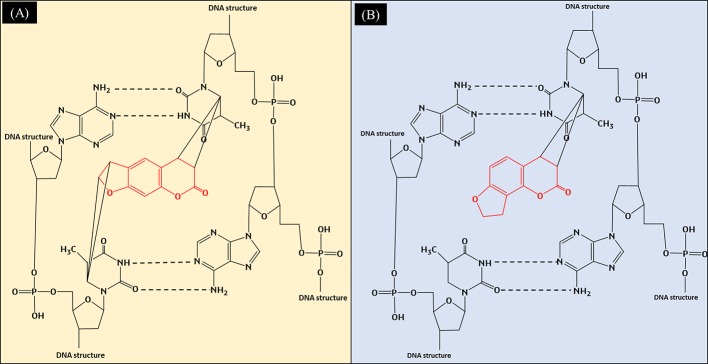

Both angelicin and psoralen are photosensitizing furocoumarins, but they interact very differently in the presence of ultraviolet radiation (UVR). With its linear structure, psoralen was discovered to form both monoadducts as well as interstrand cross-links with DNA when irradiated with UVR. When irradiated, the 3',4' or 4',5' double bonds of the molecule will covalently bind with the 5',6'-double bond of the pyrimidines from both sides of the DNA strand by absorbing photons, leading to the crosslinks that can be seen in Figure 2 (Ben-Hur and Elkind, 1973; Nagy et al., 2010). Angelicin, on the other hand, can only form monoadducts due to its steric structure (Grant et al., 1979). The monoadducts formed on DNA by angelicin are also quick to be repaired by the cells and hence, angelicin imposes lower phototoxicity as compared to psoralen (Bordin et al., 1976; Joshi and Pathak, 1983). Although both compounds are photosensitizing compounds, psoralen was favored to be used in phototherapy as it produces desirable effects such as the reduction of lesions in vitiligo, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, etc. (Vallat et al., 1994; Lee and Jang, 1998; Petering et al., 2004). However, usage of psoralen has reduced, with other modalities of phototherapy treatments and alternative drugs being preferred as psoralen was found to increase the risk of skin cancer and other systemic side effects when consumed (Llins and Gers, 1992; Stern et al., 1997).

Figure 2.

(A) Formation of interstrand crosslinks in the DNA by psoralen when exposed to UVR; (B) Formation of monoadducts in the DNA by angelicin when exposed to UVR.

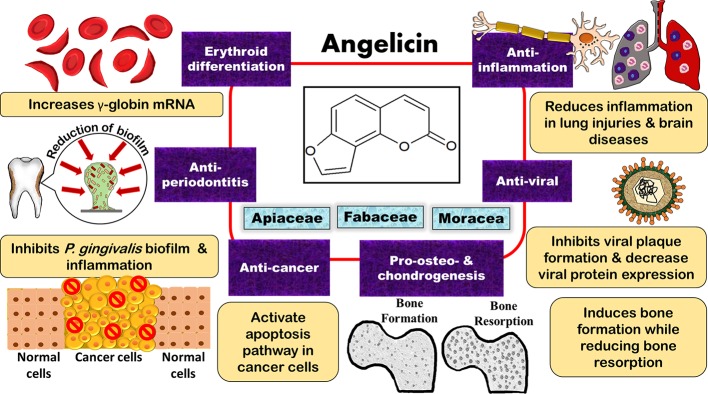

Though psoralen has been the subject of many studies due to its phototherapeutic properties, angelicin too has demonstrated multiple effects including anti-cancer, anti-viral, anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, pro-osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation, and erythroid differentiating properties (Lampronti et al., 2003; Cho et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2017a; Li et al., 2018). Regarding its anti-viral and erythroid differentiating properties, other studies have also compared angelicin to the common drugs on the market, such as ganciclovir (GCV) and hydroxyurea, and it had was shown that angelicin had almost equal or even better effect as compared to these drugs (Lampronti et al., 2003; Cho et al., 2013). This review evaluates and summarises the findings on the bioactivities of angelicin to showcase the potential of angelicin to be used as a therapeutic agent. A summary of all the biological properties of angelicin that were reported can also be seen in Table 1 and Figure 3.

Table 1.

Bioactivities of angelicin reported in in vitro and in vivo experimental models.

| Bioactivity | Experimental model | Exposure time | Chosen Concentration | Efficacy | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-cancer | SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line | 48 h in vitro assay | 0, 10, 30, 50, 70 and 100 μM angelicin | (a) Cell viability IC50: 49.56μM (b) Significant fold decrease of BcL-2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl-1: ≥ 30 μM (c) Significant fold increase of cleaved caspase 9: ≥50 μM (d) Significant fold increase of cleaved caspase 3: ≥40 μM (e) Decrease in procaspase 9 expression (f) No changes were seen on PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β, MAPK and Fas/FasL signaling pathways. |

(Rahman et al., 2012) |

| HL-60 cell line | 1. 24 h in vitro assay 2. 48 h in vitro assay |

40 and 80 μg/ml angelicin | (a) Cell viability IC50 at 24 and 48 h: 1) 148.4 μg/ml 2) 41.7 μg/ml (b) Dose-dependent upregulation of Bax and downregulation of Bcl-2 when treated with angelicin at both 24 and 48 h |

(Yuan et al., 2015) | |

| 1. Human lung carcinoma A459 cell line. 2. Female nude mice (aged 5 weeks |

1. 24 h for in vitro assay 2. In vivo experiments: (a) Oral gavage 100 mg/kg for 4 consecutive weeks. (b) Angelicin (100 mg/kg/day) was fed through intragastric administration daily for 4 weeks. |

In vitro assay: 10, 25, 50μM angelicin In vivo assay: 1. Oral gavage 100 mg/kg 2. Intragastric administration 100 mg/kg/day |

1. In vitro assays: (a) Cell viability IC50: 50.14 μM (b) Significant apoptosis rate using Annexin V-FITC and TUNEL positive cells: ≥ 25 μM (c) Significant increase in Bax/BCL-2 ratio: ≥ 10 μM (d) Significant increase in cleaved caspase 3 and 9: ≥ 10 μM (e) significant cell count decrease in G1 and an increase in G2/M phase: ≥ 25 μM (d) Significant decrease in cyclin B1: ≥ 10 μM (e) Significant decrease in cyclin E1 and cdc2: ≥ 25 μM (f) Significant inhibition of cell migration, adhesion, and invasion: ≥ 25 μM (g) Significant increase in E-cadherin: ≥ 10 μM (h) Significant decrease in MMP2 and MMP9: ≥25 μM (i) Significant increase in pERK/ERK and pJNK/JNK: ≥ 10 μM (f) No changes were seen on p38 MAPK and AKT 2. In vivo assay (a) Significant decrease in tumor size and weight compared to the control. (b) Significant decrease in the number of lung lesions compared to the control. Significant increase in the ratio of TUNEL-positive cells. A decrease in the expression levels of MMP2 and MMP9 and increased expression of E-cadherin in the immunohistochemistry assay. |

(Li et al., 2016) | |

| 1. HepG2 hepatoblastoma cell line 2. Huh-7 hepatocellular carcinoma cell line 3. Male BALB/c-nu/nu mice (aged 4–6 weeks, mean weight= 25 g) |

1. 48 h for in vitro assays except in flow cytometry and TUNEL assay, Huh-7 were incubated for 36 h with angelicin. 2. In vivo experiments: Intraperitoneal injection of angelicin daily. |

In vitro assay: 0, 10, 30, and 60 μM angelicin In vivo assay: 20 and 50 mg/kg angelicin |

In vitro assay 1. HepG2 cell line (a) Cell viability IC50 for HepG2: 90 ± 6.565 μM (b) Significant decrease of PI3K/GADPH: ≥ 90 μM (c) Significant decrease of p-AKT/AKT: ≥ 60 μM (d) Upregulation of cleaved caspase 3, caspase 9, Bax, and cytochrome c (e) Downregulation of Bcl-2 2. Huh-7 cell line (a) Cell viability IC50 for Huh-7: 60 ± 4.256 μM (b) Significant decrease of PI3K/GADPH: ≥ 30 μM (c) Significant decrease in p-AKT/AKT: ≥ 10 μM (d) Upregulation of cleaved caspase 3, caspase 9, Bax, and cytochrome c (e) Downregulation of Bcl-2 In vivo assay (a) Significant decrease in tumor weight: ≥ 50 mg/kg (b) Significant increase of TUNEL-positive cells: ≥ 20 mg/kg (C) Significant decrease in Ki-67 values: ≥ 50 mg/kg (d) Significant decrease in p-VEGFR2 values: ≥ 50 mg/kg |

(Wang et al., 2017a) | |

| Cancer cell lines 1.Human renal carcinoma (Caki) cell line 2. Hepatocellular carcinoma (Sk-hep1) cell line 3. MDA-MB-361 cell line Normal cell lines: 1. Mouse renal tubular epithelial (TCMK-1) cell line 2. human skin fibroblasts (HSFs) cell line |

24 h in vitro assay | 1) 100 μM angelicin with 50 ng/ml of TRAIL 2) 50, 75, 100 μM angelicin alone 3) 50 ng/ml TRAIL alone |

Combination of angelicin and TRAIL (a) Significant increase in the percentage of sub G1 population on Caki cells: ≥ 50 μM angelicin + 50 ng/ml TRAIL (b) Increase in cleaved PARP: 100 μM angelicin + 50ng/ml TRAIL (c) Increased in caspase 3 activity:100 μM angelicin + 50ng/ml TRAIL (e) Down-regulation of c-FLIP:100 μM angelicin + 50 ng/ml TRAIL (f) No changes were seen in apoptosis related proteins: cIAP1, XIAP, DR5, Mcl-1, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and survivin. Angelicin alone increases Bim expression but combination treatment attenuated the effect. (g) Cytotoxicity of combination treatment of angelicin and TRAIL was independent of ER stress and ROS signaling (h) Combination treatment of angelicin and TRAIL did not affect normal cells but causes apoptosis in sk-hep1, MDA-MB-361 cells |

(Min et al., 2018) | |

| Human prostate cancer (PC-3) cell line | 48 h in vitro assay | 0, 25, 50, and 100 μM angelicin | (a)Cell viability IC50: 65.2 μM | (Wang et al., 2015a) | |

| 1. Human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cell line 2. Human epithelioma (Hep2) cell line 3. Colorectal carcinoma (HCT116) cell line 4. rhabdomyosarcoma (RD) cell line 5. Human breast adenocarcinoma (MCF7) cell line 6. normal cell line human lung fibroblasts (WI-38) cell line |

(a)Cell viability IC50 and IC50 of WI-38/IC50 (SI) 1. HePG2 cell line: 13.8 ± 0.64 μM; SI: 7.4 (angelicin) • Psoralen: 17.2 ± 0.21 μM; SI: 5.6 2. Hep2 cell line: 11.5 ± 2.28μM; SI: 8.9 (angelicin) • Psoralen: 20.5 ± 0.01 μM; SI: 4.7 3. HCT116 cell line: 8.7 ± 0.72 μM; SI: 11.8 (angelicin) • Psoralen: 26.1 ± 0.51 μM; SI: 3.7 4. RD cell line: 12.9 ± 1.33 μM; SI: 7.9 (angelicin) • Psoralen: 28.3 ± 0.22 μM; SI: 3.4 5.MCF7 cell line: 7 ± 0.91 μM; SI: 14.7 (angelicin) • Psoralen: 32.4 ± 0.43 μM; SI: 3 6. WI-38 cell line: 102.9 ± 1.35 μM (angelicin) • Psoralen: 97.2 ± 0.92 μM (b) Tubulin polymerization inhibition by angelicin: 57.1 ± 6.3% (Half-maximal inhibitory concentration of tubulin inhibition: 7.92 ± 1.9 μM) • Tubulin polymerization inhibition by psoralen: 30.13 ± 6.13% (c) Rank score match of angelicin with colchicine binding residues on tubulin microtubules: -53.19 ± 0.88 kcal/mol • Psoralen: -45.49 ± 0.46 kcal/mol (d) Inhibition of histone deacetylase 8 inhibitory (HDAC8) assay by angelicin: 33.86 ± 2.86% • Psoralen: 30.70± 3.52% (e) Angelicin rank score match with the binding site of HDAC8: -77.23 ± 0.73 kcal/mol • Psoralen: -72.75 ± 1.82 kcal/mol |

(Mira and Shimizu, 2015) | |||

| 1. Human myelogenous leukemia (K562) cell line 2. Human myelogenous leukemia with multidrug resistance (K562/A02) cell line |

48 h in vitro assay | For cytotoxicity experiments, different concentrations of compounds 1–9 were added into designated wells, and for MDR reversal experiments, different concentrations of doxorubicin (DOX) were added into designated wells with or without compounds 1–9 (10 mmol/L). |

(a) Cell viability IC50: 1. K562 cell line: 0.41 ± 0.20 μmol/L 2. K562/A02 cell line: 42.7 ± 0.14 μmol/L (b) reversal fold (RF) on K562/A02 =IC50 of cytotoxic DOX alone/IC50 of cytotoxic DOX: 0.97 |

(Wang et al., 2016) | |

| The marrow cavity of cortical bone (tuberosity region of the lower part of the tibia) of nude rats was injected with UMR-106 cells (rat osteosarcoma) | The treatment was administered via intratumoral multi-point injection when the tumor is 0.5 cm x 0.5 cm large. All treatment except cisplatin was administered for 2 courses (5 days per course) with a day break in between two courses. For the cisplatin treatment, the rats were only treated on day 1, 4, 7, and 10. | 1. Psoralen: 320 μg/(kg.d) and 1,600 μg/(kg.d) 2. Angelicin: 320μg/(kg.d) and 1,600 μg/(kg.d) 3. Cisplatin: 2 mg/kg |

1. No significant reduction in body weight was seen for both psoralen and angelicin treatment. However, the bodyweight of those treated with cisplatin experienced significant body weight loss after the 3rd of administration. 2. After the 3rd day administering psoralen and angelicin, the rats showed some toxic reactions such as lassitude, hypoactivity, and writhing movements. No writhing movements were seen in the treatment of cisplatin. 3. The osteosarcoma volume and weight were significantly decreased in all treatments. 4. Significant decrease in serum ALP in all treatments. 5. All treatment showed a decrease in tumor cell density, increased amount of necrotic tumor cells, cell debris, and protein-like substances can be found in the center, shrinking of cells with nuclei condensation, decreased mitosis. Some tumor tissue experienced haemorrhaging, increased intercellular substances and infiltration of lymphocyte. No metastatic lesion in the abdomen or changes in the liver, spleen, kidney, hearts, and lungs. 6. The higher doses of psoralen and angelicin, together with cisplatin, displayed inflammatory cell aggregation and tubulointerstitial vascular dilation and congestion in the renal intercellular space. 7. Electron microscope: (a) Low doses of angelicin and psoralen: Cells were arranged loosely with dilated endoplasmic reticulum, damaged and dissolved nuclear membranes, condensed nuclei, large vacuoles in cytoplasm, chromatins distributed in clumps, rare sighting of organelles and typical necrotic features. (b) High doses of angelicin and psoralen: Ruptured cells, loose and disappeared cytoplasm, ruptured and rough nuclear membranes, blurred intranuclear structure, loose chromatins, and large mitochondria. (c) Cisplatin: Cavitated and denatured mitochondria and matrices, homogenized nuclei, deepened colour, clumped chromosomes, and flocculent shaped lipid droplets. 8. No significant difference in the number of peripheral red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, haemoglobin and bone marrow nucleated cells between the control group and psoralen and angelicin treated group. Cisplatin had a significant decrease in white blood cells and bone marrow nucleated cells. |

(Lu et al., 2014) | |

| 1. Human cervical carcinoma cell line (HeLa) 2. Cervical squamous cell carcinoma cell line (SiHa) 3. Nontumor cervical epithelial cell line (ECT1/E6E7) |

1. Cell viability assay: Cells were exposed to angelicin for 24 h. 2. Cell viability assay (IC30): Cells were exposed to angelicin at their IC30 for 5 days. 3. Cell cycle, cell proliferation, colony formation, tumor formation, migration and invasion assays: Exposure time to angelicin were not mentioned 4. Apoptosis and autophagy assay: Cells were exposed to angelicin for 24 h. |

1. Cell viability assay to determine the IC30 and IC50 for each cell line: 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, 140, 160, 180, or 200 µM angelicin 2. The following assays (5 days cell viability, proliferation, cell cycle, colony formation, tumor formation, migration, invasion and autophagy assays) were demonstrated using the IC30 angelicin concentration of each cell line. 3. The following assays (apoptosis assay) were demonstrated using IC50 angelicin concentration for each cell line. |

1. Measurement of 30% and 50% inhibitory concentration (IC30 and IC50) after treatment with angelicin for 24 h: (a) HeLa cells: IC30 = 27.8μM; IC50 = 38.2 μM (b) SiHa cells: IC30 = 36.6μM; IC50 = 51.3 μM (c) ECT1/E6E7 cells: IC30 = 82.7 μM; IC50 = 138.5μM 2. Cell viability of cells after incubating at their IC30 concentration: (a) HeLa cells: ≥ day 4 (b) SiHa cells: ≥ day 4 2. Angelicin decreased the proliferation of both HeLa and SiHa cells 2. Cell cycle assay: Both HeLa and SiHa cells were significantly arrested at the G1/G0 phase and significantly decreased at G2/M 3. Angelicin decreased the colony formation, tumor formation, migration and invasion of both HeLa and SiHa cells 4. Angelicin significantly increase apoptotic death rate in both HeLa and SiHa cell lines 5. Autophagy assay: (a) Angelicin increased the accumulation of LC3B in the cytoplasm of both HeLa and SiHa cell lines (b) Angelicin decreased the LC3B and LC3B-II quantity in both HeLa and SiHa cell lines (c) Angelicin decreased Atg3, Atg7, Atg12-5, and LC3B protein expression in both HeLa and SiHa cell lines. 6. Angelicin increased the phosphorylation of mTOR protein and decreased the protein level of LC3B-II in both cell lines. |

(Wang et al., 2019b) | |

| 1. Docking of angelicin to ERα, progesterone receptor (PR), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and mTOR 2. MCF-7 cells |

1. ERα reporter antagonist assay: 22–24 h treatment with angelicin 2. mTOR inhibition assay: MCF-7 cells were treated with angelicin for 24 h |

Not specified | 1. The binding energy of angelicin: (a) ERα: -12.01 kcal/mol (b) PR: -11.63 kcal/mol (c) EGFR: -12.60 kcal/mol (d) mTOR: -13.64 kcal/mol 2. Docking score (Ref/selected bio-molecules) and nature of interaction of angelicin: (a) ERα: -34.44/-12.01 kcal/mol, hydrophobic and polar H interactions (b) PR: -21.11/-11.63 kcal/mol, hydrophobic and polar H interactions (c) EGFR: -19.22/-12.60 kcal/mol, hydrophobic and polar H interactions (d) mTOR: -46.09/-13.64 kcal/mol, hydrophobic and polar H interactions 3. IC50 of angelicin in reducing luminescence intensity (antagonizing ERα): 11.02 µM 4. Angelicin attenuates the upregulated EGFR expression in MCF-07 cells 5. Angelicin was unable to inhibit mTOR |

(Acharya et al., 2019) | |

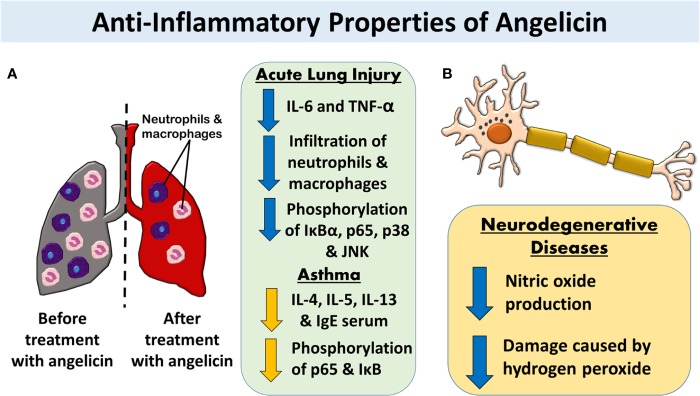

| Anti-inflammatory | 1. RAW 264.7 mouse macrophage cell line 2. BALB/c male mice (8-10 weeks old with the weight of 18-20g each) |

(1) In vitro assay: 1 h pretreatment with angelicin followed by 18 h of 4 µg/ml LPS stimulation (2) In vivo assay: 1 h pretreatment with angelicin intraperitoneally followed by 10µg LPS stimulation. Mice were sacrificed after 6 h. The lungs were lavaged and excised. |

1) 0–200 µg/ml angelicin for in vitro assay 2) 1, 5, and 10 mg/kg angelicin for in vivo assay |

(a) In vitro assays: 1. Concentrations of 100 and 200 µM were able to reduce cell viability 2. Significant decrease of TNFα and IL-6: ≥ 12.5 µg/ml (b) In vivo assays: 1. Significant decrease in total cells and neutrophils in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF): ≥ 1 mg/kg 2. Significant decrease in macrophages in BALF: ≥ 5 mg/kg 3. Significant decrease in TNF-α and IL-6 in BALF: ≥ 1mg/kg 4. Significant decrease in lung injury score: ≥ 1 mg/kg 5. Significant decrease in lung W/D ratio: ≥ 1 mg/kg 6. Significant decrease in MPO activity: ≥ 1 mg/kg 7. Significant decrease in p-p65NF-κB -actin ratio when induced with 500 µg/kg LPS: ≥ 1mg/kg 8. Significant decrease in p-IκBα/β- actin ratio when induced with 500 µg/kg LPS: ≥ 1 mg/kg 9. Significant increase in IκBα/β- actin ratio when induced with 500 µg/kg LPS: ≥ 1 mg/kg 10. Significant decrease in pJNK/JNK ratio and p-p48/p38 ratio when induced with 500 µg/kg LPS: ≥ 1 mg/kg |

(Liu et al., 2013) |

| 1. Female BALB/c mice with weight of 18-20g each | In vivo assay: Angelicin was given 1 h as a pretreatment before OVA treatment after initial sensitization. After 24 h, the mice were sacrificed. | 2.5, 5, 10 mg/kg angelicin | 1. Significant decrease of total inflammatory cell count, eosinophils, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages: ≥ 2.5 mg/kg 2. Significant decrease of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in BALF: ≥ 2.5 mg/kg 3. Significant decrease in IgE production: ≥ 2.5 mg/kg 4. Significant alleviation of OVA-induced airway hyperresponsiveness (expressed at enhanced minute pause (Penh) that reflects pulmonary resistance when treated with 10 mg/kg methchacholine: ≥ 2.5 mg/kg 5. Significant decrease in p-p65/β-actin ratio and p-IκB/β-actin ratio: ≥ 2.5 mg/kg |

(Wei et al., 2016) | |

| 1. Mouse microglia BV-2 cell line which is generated through infection of primary microglial cell with vraf/v-myc oncogene carrying retovirus. 2. Mouse hippocampal HT22 cell line |

1. Measurement of NO in BV-2 cells: 2 h pre-treatment with compound 2. Measurement of neuroprotective effect against hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in HT22 cells: 6 h co-treatment with H2O2 |

25, 50, 100 µM angelicin | 1. Significant decrease of LPS induced NO in BV-2 cells by angelicin: ≥ 50 µM • No significant change of LPS induced NO in BV-2 cells by psoralen 2. Significant (p < 0.01) increase in cell viability in HT22 cells treated with H2O2 by angelicin: ≥25 µM • Significant (p < 0.05) increase in cell viability in HT22 cells treated with H2O2 by psoralen: 25 µM (higher concentrations showed no significant changes in cell viability as compared to treating the cells alone with H2O2) |

(Kim et al., 2016) | |

| 1. Human neutrophils obtained from the venous blood of healthy adult patients (age: 20-28 years old) 2. RAW264.7 murine macrophage cell line |

1. Measurement of the generation of superoxide anion and release of elastase: 5 min of incubation with the compounds obtained from Psoralea corylifolia L. 2. To determine NO production: 24 h of incubation with the compounds obtained from Psoralea corylifolia L. |

1. Measurement of superoxide anion generation: 30–0.01 µM of compounds obtained from Psoralea corylifolia L. 2. Determination of NO production: 0,3, 15, 30, and 60 µM of compounds obtained from Psoralea corylifolia L. |

1. Percentage of angelicin induced inhibition of superoxide anion at 30 µM: 44.91± 6.46% (Significant against positive control) • IC50 of psoralen induced inhibition of superoxide anion: 5.91± 3.22 µM (Significant against positive control) 2. Percentage of angelicin induced inhibition of elastase release at 30 µM: 27.73 ± 4.22 (Significant against positive control) • Percentage of psoralen induced inhibition of elastase release at 30µM: 24.70 ± 5.99 (Significant against positive control) 3. IC50 inhibition against the formation of NO by RAW264.7 murine macrophages by angelicin: 56.82 ± 3.7 µM (Significant against positive control) • IC50 inhibition against the formation of nitric oxide by RAW264.7 murine macrophages by psoralen: 40.15 ± 2.27 µM (Significant against positive control) |

(Chen et al., 2017) | |

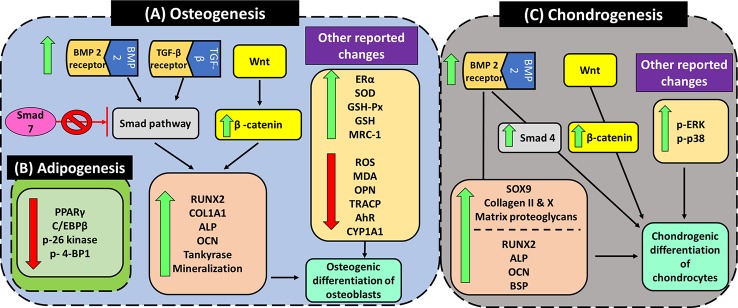

| Pro-osteogenesis | Primary rat calvarial osteoblasts isolated from calvaria of newborn Winstar rats | 1. Cell proliferation assay: the cells were treated with angelicin for 24 and 48 h 2. ALP assay: the cells were treated with angelicin for 24, 48 and 72 h |

1, 10, 100 µM angelicin | 1. No changes in proliferation rate or cell toxicity were seen. 2. No changes in ALP activity was seen |

(Li et al., 2014) |

| 1. Murine pre-osteoblast (MC3T3-E1) cells 2. HEK293T cells transfected with (CAGA) 12-Luc-reporter plasmid and internal control (pRL-TK vector) |

1. Cell viability assay on MC3T3-E1 cells: 72 h incubation with angelicin 2. Measurement of the luciferase activity (activation of TGF-β1 reporter gene): HEK293T cells were treated with angelicin for 12 h. 3. Measurement of mRNA and protein expression level of M3T3-E1 cells after incubation of cells with angelicin for 72 h. Before treatment, 24 h synchronization was done to cause the cells to quiescence at G0 stage. |

1. Cell viability assay, measurement of mRNA and protein expression level on MC3T3-E1 cells: 0.1, 0.01, 0.001 and 0.0001µM angelicin 2. Measurement of the luciferase activity (activation of TGF-β1 reporter gene) in HEK293T cells: 0.1, 0.01, 0.001 and 0.0001 µM |

1. Significant increase in MC3T3-E1 cell viability: ≥ 0.01 μM angelicin 2. Significant increase in relative luciferase activity which indicates the of TGF-β1 reporter gene activity: ≥ 0.01 μM angelicin 3. Significant increase in Type I collagen mRNA levels: ≥ 0.01 μM angelicin 4. Significant decrease in Smad7 protein levels: ≥ 0.01 μM angelicin |

(Zhang and Ta, 2017) | |

| OB-6 osteoblastic cells | Treatment of cells with angelicin, H2O2 or combination of both for 12, 24 and 48 h for all assays except when measuring the protein expression of β-catenin, tankyrase, and Wnt. The exposure time of cells to angelicin and/or H2O2 was not mentioned for protein expression analysis. | There are 4 groups: 1. Control group 2. Angelicin only group: cells treated with 1µM angelicin 3. H2O2 only group: cells treated with 100µM H2O2 4. Combined group: cells treated with both 1µM angelicin + 100µM H2O2 |

1. Combined group significantly increase the percentage of cell viability as compared with H2O2 only group: ≥ 12 h treatment 2. Combined group significantly decrease the apoptotic rate as compared with H2O2 only group: ≥ 12 h treatment 3. Combined group significantly decrease the ROS levels as compared with H2O2 only group ≥ 12 h treatment 4. Combined group significantly increase complex I activity as compared with H2O2 only group: ≥ 12 h treatment 5. Combined group significantly increase the calcium levels as compared with H2O2 only group: ≥ 12 h treatment 6. Combined group significantly increase the OCN and RUNX2 mRNA expression as compared with H2O2 only group: ≥ 12 h treatment 7. Combined group significantly increase the β-catenin and tankyrase protein expression as compared with the H2O2 only group. The expression of Wnt protein experienced no changes with any treatment. |

(Li et al., 2019) | |

| Primary rat osteoblasts cells obtained from female Winstar rat with a weight of 5-6g | 1. Cell proliferation assay: 24, 48, 72 h incubation with angelicin 2. Measurement of ALP activity: 7 days incubation with angelicin 3. Quantification on level of osteoblast mineralization: 12 days incubation with angelicin 4. Gene and protein expression analysis: 24 h incubation with angelicin |

0.1, 1, 10µM angelicin | 1. Significant increase in osteoblasts cell proliferation after 48 and 72 h incubation with ≥ 1µM angelicin and ≥ 0.1 µM angelicin respectively. 2. Significant increase in ALP relative activity in osteoblasts after 7 days incubation with angelicin: ≥ 0.1 µM 3. Significant increase in mineralization of osteoblasts after 12 days incubation with angelicin: ≥ 1 µM 4. Significant increase in ALP and OCN mRNA after 24 h incubation with angelicin: ≥ 1 µM 5. Significant increase in RUNX2 and COL1A1 mRNA after 24 h incubation with angelicin: ≥ 0.1 µM 6. Significant increase in RUNX2, BMP2, and ERα protein expression after 24 h incubation with angelicin: ≥ 1 µM 7. Significant increase in β-catenin protein expression after 24 h incubation with angelicin: ≥ 0.1 µM |

(Ge et al., 2019) | |

| 1. Primary femoral BMSCs obtained from C57BL/6 mice (4 weeks old) 2. Female C57BL/6 mice (aged 2 months) |

(a) In vitro assay: 1. Measurement of cell growth after 2 days of treatment with angelicin 2. Measurement of ALP- positive cells after 14 days of treatment with angelicin 3. Analysis of the adipogenesis rate after adipogenic differentiation at day 7 and day 14 4. Measurement of OCN and RUNX2 expression in BMSC differentiated osteoblasts after 14 days of treatment (Immunocytochemistry and western blotting) 5. Measurement of C/EBPβ and PPARγ expression in BMSC differentiated adipocytes after 7 and 14 days of treatment (Immunocytochemistry and western blotting) 6. Assessment of the changes in the mTORC1 signaling pathway (4E/BP1 and p-S6) in BMSC adipogenesis after treatment with angelicin for 7 and 14 days. (b) In vivo assay: The mice were administered angelicin for 5 days prior to overiectomy and angelicin was continuously administered for 2 months after the operation. 1. Measurement of RUNX2 and PPARγ expression in the distal femur 2. Measurement of the number of adipocytes in the bone marrow 3. Measurement of the trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), bone volume/total volume (BV/TV) and trabecular number (Tb.N) in mouse distal femur |

(a) In vitro assay: 1. Measurement of cell growth: 0.1, 1, 10, 100, and 1,000 μM angelicin 2. Other assays: 5, 10 and 20μM angelicin (b) In vivo assay: 20mg/kg angelicin |

(a) In vitro assay: 1. Cell growth: No changes in the cell growth up to 100 μM angelicin. Concentrations of 1,000 μM significantly decrease cell viability. 2. Significant increase in ALP- positive cells: ≥ 5 μM angelicin 3. Significant decrease in adipogenesis rate after adipogenic differentiation at day 7 and day 14: ≥ 5 μM angelicin 4. Significant increase in OCN and RUNX2 expression in BMSC differentiated osteoblasts after 14 days of treatment (Immunocytochemistry and western blotting): ≥ 5 μM angelicin 5. Significant decrease in C/EBPβ and PPARγ expression in BMSC differentiated adipocytes after 7 and 14 days of treatment (Immunocytochemistry and western blotting):≥ 5 μM angelicin 6. Significant increase and decrease in 4E/BP1 and p-S6 expression respectively in BMSC adipogenesis after treatment with angelicin for 7 and 14 days: ≥ 5 μM angelicin 7. There was an increase and decrease in 4E/BP1 and p-S6 expression respectively in BMSC osteogenic differentiation after treatment with angelicin for 14 days (b) In vivo assay: 1. Significant increase and decrease in RUNX2 and PPARγ expression respectively in the distal femur after treatment with angelicin 2. Significant decrease in the number of adipocytes in the bone marrow after treatment with angelicin 3. Significant increase in the trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), bone volume/total volume (BV/TV) and trabecular number (Tb.N) in mouse distal femur after treatment with angelicin |

(Wang et al., 2017b) | |

| 1. MC3T3-E1 cells 2. C57BL/c mice (8 weeks old) |

(a) In vitro assay: 1. Quantification of MC3T3 cell mineralization: 14 days incubation with angelicin 2. Measurement of relative ALP activity: 9 days incubation with angelicin 3. Gene expression analysis: 24 and 72 h incubation with angelicin 4. Analysis of AhR protein expression in nucleus and cytoplasm of osteoblasts: 24 h incubation with angelicin 5. Analysis of the binding affinity of angelicin to AhR using drug affinity responsive target stability (DARTS) analysis. MC3T3-E1 cell lysate (5 mg/ml) was incubated with 10µM angelicin for 1 h at room temperature before digestion of protein with pronase to 1:1,000 or 1:2,000 for 30 min. 6. Analysis of ERα protein expression: 5 days incubation with angelicin (b) In vivo assay: 1. Analysis of CYP1A1 content in serum after injection of mice with angelicin |

(a) In vitro assays: 2, 10, and 50 µM angelicin (b) In vivo assays: 10 mg/kg angelicin |

(a)In vitro assay 1. Significant increase in MC3T3-E1 mineralization after 14 days incubation with angelicin: ≥ 10 μM 2. Significant increase in relative ALP activity after 9 days incubation with angelicin: ≥ 10 μM 3. Significant increase in ALP mRNA after 24 and 72 h incubation with ≥ 10 μM and ≥ 2 μM angelicin respectively. 4. Significant increase in COL1A1 mRNA after 24 and 72 h incubation with ≥ 10 μM and ≥ 2 μM angelicin, respectively. 5. Significant increase in RUNX2 mRNA after 24 and 72 h incubation with ≥ 50 μM and ≥ 10 μM angelicin respectively. 6. Significant decrease in CYP1A1 mRNA after 24 and 72 h incubation with ≥ 2 μM angelicin. 7. Significant increase in AhR protein levels in the cell cytoplasm while a significant decrease in AhR protein levels in the cell nucleus after incubation with ≥ 2 μM angelicin for 24 h 8. Significant binding of 10 µM angelicin to AhR, inhibiting proteolysis at 1:1,000 and 1:2,000 protein ratios. 9. Significant increase in ERα protein expression after 5 days incubation with angelicin: ≥ 2 μM (b) In vivo analysis: 1. Significant decrease in CYP1A1 content in serum after treatment of mice with 10 mg/kg angelicin |

(Ge et al., 2018) | |

| ICR mice 1. Female mice (8 weeks old and ovariectomized) 2. Male mice (10 weeks old and orchidectomized) |

Six weeks after the mice were ovariectomized or orchidectomized, the mice were randomly divided into 6 groups with 12 mice each. The mice were treated intragastrically once a day for 8 weeks before being sacrificed. 1. Control group: sham-operated mice 2. Model group: ovariectomized/orchidectomized mice 3. Female positive drug group: females treated with estradiol valerate (E2) 4. Male positive drug group: males with alendronate sodium (AS) 5. Psoralen group: mice treated with psoralen for both gender groups 6. Angelicin group: mice treated with angelicin for both gender groups |

1. Psoralen group: 10 and 20 mg/kg 2. Angelicin group: 10 and 20 mg/kg |

1. Female group: (a) No changes in the ALP in the serum were seen even in between the control and model groups. (b) Significant decrease in TRACP in the serum was seen in mice treated with 20mg/kg angelicin. However, there were no changes seen between control and model group. (c) Significant increase in the ALP/TRACP ratio in the serum were seen in the mice treated with E2, 10 mg/kg psoralen and 10mg/kg angelicin. However, there were no changes seen between control and model group. (d) Significant increase of CTX-1(degraded type I collagen) in the serum model group as compared to the control group. However, the effect was significantly attenuated by E2, 20 mg/kg psoralen, 10 mg/kg angelicin and 20 mg/kg angelicin. (e) No changes in OCN in the serum were seen even in between the control and model groups. (f) Significant increase in the degree of anisotrophy (DA) was seen in the model group compared to the control group but the effect was reversed by E2, 10 mg/kg psoralen, 10mg/kg angelicin and 20mg/kg angelicin. (g) Significant decrease in bone volume (BV/TV) in model group compared to the control group but were attenuated by E2 and 20 mg/kg psoralen. (h) Significant decrease in trabecular number (Tb.N) in model group compared to the control group but were attenuated by all treatments. (g) Significant increase in trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) in model group compared to the control group but were attenuated by all treatments. (h) Significant increase in trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) in model group compared to the control group but were attenuated by all treatments. (i) Significant decrease in bone strength in model group compared to the control group but was attenuated by all treatments. 2. Male group: (a) Significant increase in ALP in male mice was seen when treated with 10mg/kg psoralen and angelicin. However, there were no changes seen between the control and model groups. (b) No changes were seen in the TRACP in the serum even in between the control and model groups. (c) Significant increase in the ALP/TRACP ratio in the serum was seen in the mice treated with 10 mg/kg psoralen and 10 mg/kg angelicin. However, there were no changes seen between control and model group. (d) Significant increase in CTX-1 in the serum in the model group. However, the effect was significantly by AS, 10 mg/kg psoralen, 10 mg/kg angelicin and 20 mg/kg angelicin. (e) Significant increase in the OCN in the serum model group as compared to the control group. However, the effect was significantly attenuated by 10 mg/kg angelicin. (f) Significant increase in the DA were seen in the model group compared to the control group but the effect was reversed by 10 and 20 mg/kg psoralen and angelicin. (g) Significant decrease in bone volume (BV/TV) in model group compared to the control group but were attenuated by all treatments. (h) Significant decrease in trabecular number (Tb.N) in model group compared to the control group but were attenuated by all treatments. (g) Significant increase in trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) in model group compared to the control group but were attenuated by 20 mg/kg psoralen. (h) Significant increase in trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) in model group compared to the control group but were attenuated by all treatments. (i) Significant decrease in bone strength in model group compared to the control group but was attenuated by all treatments. |

(Yuan et al., 2016) | |

| 6 week old female Sprague Dawley rats (weight: 140–160g) | The rats were distributed into 4 groups before ovariectomizing. The rats were treated with angelicin every 3 days for 12 weeks. 1. Control group: sham-operated 2. Model group: ovariectomized mice (osteoporosis) 3. 10 mg/kg angelicin group 4. 20 mg/kg angelicin group |

10 and 20 mg/kg angelicin | 1. Significant decrease in calcium/creatine (Ca/Cr) levels in urine: ≥ 10 mg/kg angelicin 2. Significant increase in bone mineral density (BMD): ≥ 10 mg/kg angelicin 3. Significant decrease in structure score of the proximal tibial metaphysis (PTM): ≥ 10 mg/kg angelicin 4. Significant increase in serum leptin levels: ≥ 10 mg/kg angelicin 5. Significant decrease in serum calcium levels: 20 mg/kg angelicin 6. Significant decrease in ALP activity in blood: ≥ 10 mg/kg angelicin 7. Significant decrease in COL I, OCN and OPN mRNA in total cartilage tissue: ≥ 10 mg/kg angelicin 8. Significant decrease in MDA activity in blood: ≥ 10 mg/kg angelicin 9. Significant increase in SOD, GSH and GSH-PX activity in blood: ≥ 10 mg/kg angelicin 10. Significant decrease in caspase 3 and 9 activity: ≥ 10 mg/kg angelicin 11. Significant increase in WNT protein expression: ≥ 10 mg/kg angelicin 12. Significant increase in β-catenin protein expression: ≥ 10 mg/kg angelicin 13. Significant decrease in PPARγ protein expression: ≥ 10 mg/kg angelicin |

(Wang et al., 2018) | |

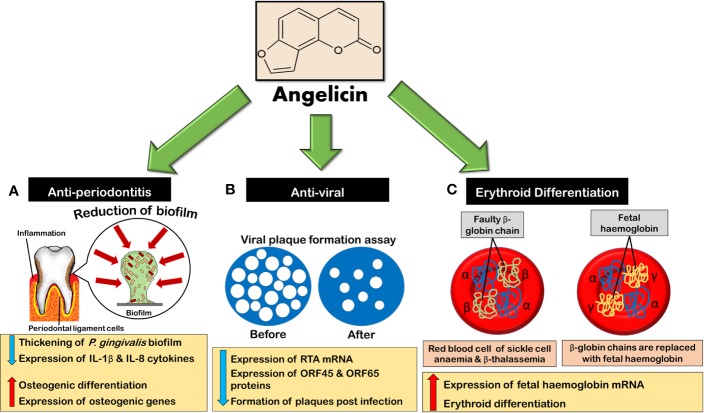

| Anti-periondontitis | 1. Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) 2. THP-1 cells 3. Primary human periodontal ligament cells (hPDLCs) obtained from patients using tissue explant method. 4. In vivo: Wild type 8 week old male C57BL/6 mice |

In vitro assays: (a) Incubation for 48 h under anaerobic conditions for MBC, MIC, biofilm formation assays (b) Incubation for 24 h in assays to assess biofilm reduction, viability, and thickness (c) Incubation for 24 h in MTT assay for hPDLCs and THP-1 cells (d) Pretreatment for 2 h on THP-1 cells before inflammatory stimulation with P. gingivalis-derived lipopolysaccharide (Pg-LPS) (e) Treatment for 9 days on hPDLCs in osteogenic induction assay. On the 3rd day, the expression of osteogenic proteins was analyzed via measurement of concentration in BCA protein assay kit. In vivo assays: (a) Mice were injected with angelicin 30 min prior to injection with Pg-LPS. The mice were injected with angelicin and 10 mg/ml Pg-LPS three times a week for 4 weeks. |

1. In vitro assays: (a) 1.5625, 3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, and 50 µg/ml angelicin and psoralen in bacterial, cell viability (on THP-1 and hPDLCs) and inflammatory analysis (b) 6.25 µg/ml of psoralen and 3.125 µg/ml angelicin in osteogenic induction analysis 2. In vivo assays: 20mg/ml angelicin |

1. In vitro assays: (a) Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) (lowest concentration that shows no macroscopically visible bacterial growth at 625 nm) of angelicin: 3.125 μg/ml •MIC of psoralen: 6.25 μg/ml (b) Minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) (lowest concentration where no bacterial clone grew on the agar) of angelicin: 50 μg/ml •MBC of psoralen: 50 μg/ml (c) Minimum biofilm inhibition concentration (MBIC50) (lowest drug concentration that results in 50% inhibition of formation of biofilm compared to control) of angelicin: 7.5 μg/ml • MBIC50 of psoralen: 15.8 μg/ml (d) Minimum biofilm reduction concentration (MBRC50) (lowest drug concentration that reduces biofilm to 50% compared to control) of angelicin: 23.7 μg/ml • MBRC50 of psoralen: 24.5 μg/ml (e) Sesemile MIC (SMIC50) (lowest concentration causing 50% reduction in bacterial viability compared to untreated control) of angelicin: 6.5 μg/ml • SMIC50 of psoralen: 5.8 μg/ml (f) Angelicin has shown more significant decrease in thickness of biofilm (p < 0.001) as compared to psoralen (p < 0.01) (g) Significant decrease in THP-1 and hPDLCs cell viability for both psoralen and angelicin: ≥ 2.5 μg/ml (h) Significant decrease of IL-1β mRNA expression by angelicin: 1.5625 μg/ml (p < 0.001) • Significant decrease of IL-1β mRNA expression by psoralen: 1.5625 μg/ml (p < 0.05) (i) Significant decrease in IL-8 mRNA expression by angelicin: 1.5625 μg/ml (p < 0.001) • Significant decrease in IL-8 mRNA expression by psoralen: 3.125 μg/ml (p < 0.01) (j)Significant decrease in IL-1β protein expression by angelicin: 1.5625 μg/ml (p < 0.05) • Significant decrease in IL-1β protein expression by psoralen: 3.125 μg/ml (p < 0.05) (k) Significant decrease in IL-8 protein expression by angelicin: 3.125 μg/ml (p < 0.05) • Significant decrease in IL-8 protein expression by psoralen: 6.25 μg/ml (p < 0.05) (l) Significant increase in RUNX2, DLX5, and OPN mRNA expression hPDLCs as compared to control by both angelicin and psoralen: Day 3, 6, and 9 2. In vivo assays: (a)Significant in bone volume percentage (bone volume/total volume, BV/TV), bone mineral density (BMD) and bone surface/bone volume (BS/BV) by angelicin |

(Li et al., 2018) |

| Pro-chondrogenesis | Pre-chondrogenic ATDC5 cells | 1. Measurement of the rate of cell growth with MTT assay: 24 h incubation with angelicin 2. Induction of chondrogenic differentiation: Incubation of cells with angelicin for 14 days 3. Measurement of chondrogenic marker genes after treatment with angelicin for 7, 14 and 21 days 4. Measurement of ALP activity of cells treated with angelicin for 7, 14 and 21 days 5. Measurement of BMP-2 protein level after treatment with angelicin for 1, 2 and 3 days. 6. Measurement of JNK, ERK and p38 protein levels (including phosphorylated proteins) after cells were serum-starved for 16 h and then treated with angelicin for 1.5, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h. |

1. Rate of cell growth with MTT assay: 0.001, 0.005, 0.05, 0.1, and 1 μM angelicin 2. Induction of chondrogenic differentiation (formation of cartilage nodules): 0.01, 0.05, 0.5, and 1μM angelicin 3. Measurement of collagen X and collagen II mRNA for 21 days: 0.005, 0.05, 0.5, and 1 µM 4. Measurement of BSP, collagen I, RUNX2, collagen II, collagen X, OCN, β-catenin, smad 4, and SOX9 mRNA for 21 days: 0.05 µM 5. Analysis of the ALP activity in cells: 0.05 µM angelicin 6. Measurement of BMP-2 protein level: 0.05 µM angelicin 7. Measurement of MAPK kinase protein levels: 0.05 µM angelicin |

1. No increase in the rate of cell growth was observed after treatment with angelicin. 2. Significant increase in number of stained cartilage nodules (synthesis of matrix proteoglycan): 0.01, 0.05, and 0.5μM angelicin 3. Increase in collagen X and collagen II mRNA: ≥0.005 μM angelicin 4. Increase in BSO, collagen I and RUNX2 mRNA: day 14 5. Increase in collagen II, collagen X, OCN, β-catenin, smad 4, and SOX9 mRNA: ≥ day 7 6. Increase in ALP activity in cells treated with angelicin: ≥ day 14 7. Increase in BMP-2 protein expression after 24 h 8. Increase in phosphorylated ERK and p38 at 1.5 h after treatment with angelicin. |

(Li et al., 2012) |

| Anti-viral | 1. African green monkey kidney (CV-1) cells infected with HSV 2. Human normal skin (KD) cell line (CRL 1295) infected with HSV 2. Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) cell line (CRL 1223) infected with HSV |

Pretreatment of angelicin or 8-MOP for 30 min before being irradiated with 1.6 KJm-2min-1 at 365nm UVA | 1. 50 µM angelicin or 8-MOP for CV-1 cells 2. For human skin cells, 0.3mM angelicin and 50µM 8-MOP |

1. 8-MOP is 7.5 fold higher than angelicin in reducing the HSV production capacity in CV-1 cells with UVA. 2. For the first 12 h of treatment of angelicin with 365nm UVA, the viral yield decreases and then starts to recover after 24 h and finally reaches its maximum yield after 72 h in CV-1 cells. Similar results were seen with 8-MOP with the exception that an initial decrease and then an increase in HSV production, reaching a maximum at 72 h was seen. 3. In normal and XP cell lines, angelicin is 5.4 and 4.1 less efficient than 8-MOP, respectively. The HSV production is more inhibited in XP cells as compared to normal cells when treated with angelicin. 4. The amount of unscheduled DNA synthesis induced by 8-MOP with UVA is 40% higher than angelicin with light. |

(Coppey et al., 1979) |

| 1. Mouse 3T3 cell line infected with murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) | Virus suspensions were incubated with the compounds for 30 min before exposing UVA irradiation (incident energy = 300 W/m2) for 30 min. | 10 µg/ml of angelicin | 1. Angelicin did not produce cross-links in the viral DNA but its phototoxicity suggests that monoadducts may cause viral genome to be non-infectious. | (Altamirano‐Dimas et al., 1986) | |

| 1. Mouse 3T3 cell line infected with murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) and sindbis virus (SV) 2. Eschericia coli infected with bacterial phage T4 and phage M13 |

Virus suspensions were incubated with the compounds for 30 min before UVA irradiation (incident energy = 5 W/m2). | (Not mentioned) | Angelicin has relative toxicity against double stranded DNA phage T4, double stranded DNA MCMV, single stranded DNA phage M13, and single stranded RNA SV. | (Hudson and Towers, 1988) | |

| 1. BHK21 cells (baby hamster kidney fibroblast) containing MHV-68 virus 2.Vero cells (green monkey kidney) containing MHV-68 virus 3. BC-3 cells (KSHV positive, EBV negative cells) 4. BCBL-1 cells (KSHV positive, EBV negative cells) 5. B95.8 cells (EBV positive, KSHV negative) 6. Raji cells (EBV positive, KSHV negative) 7. BC-3G cells (containing strong RTA-responsive element which drives destabilized EGFP expression) 9. 293T cells for promoter reporter analysis |

1. Antiviral screening: Pretreatment of compounds 3 h prior to viral infection and during 1 h of viral adoption in BHK21 cells 2. Analysis of promoter reporter: 294T cells were transfected with 650 ng of plasmid and then angelicin was used to treat 1 h after post-transfection. 3. Plaque reduction assays: compounds were added as a pretreatment 3 h prior to viral adoption or as a post-treatment in the media. 4. Cytotoxic assay: angelicin was incubated with cells for 24 h before MTT assay. |

1. Anti-viral screening for compounds: 4, 20 and 100µg/ml of compounds against MHV-68 2. To reconfirm the anti-viral effect of angelicin on viral replication= 3,7.5, 15, and 30 µg/ml before and after viral infection.) 3. To determine antiviral efficacy: 0.1–90 µg/ml (0.54–483.3µM) angelicin 4. To determine cytotoxicity toward Vero cells: 0.1 to 500 µg/ml (0.54 to 2,685.86 µM) •Positive control: GCV 20 µg/ml |

1. Angelicin reduces MHV-68 viral replication dose-dependently. 2. Angelicin inhibits ORF45 and ORF65 late gene protein expressions dose-dependently. • GCV inhibits completely the expression of both proteins. 3. Angelicin decreases viral genome replication dose-dependently. 4. Angelicin directly inhibits mRNA expression of RTA dose-dependently by reducing the transactivation of RTA promoter. 5. Angelicin reduces plaque formation of MHV-68 by about 80% as compared to negative control post-treatment. • GCV reduces plaque formation by 100% in pre and post-treatments. 6. Concentration of angelicin required to inhibit MHV-68 replication by 50% (IC50): 5.39 µg/ml (28.95 µM) 7. Concentration of angelicin to decrease cell viability to 50% (CC50): Not obtainable. At 500 µg/ml (2,685.86 µM) angelicin, cell viability is at 72.5% 8. Angelicin efficiently inhibits EBV lytic replication via inhibition of early antigen diffuse (EA-D) expression, relative EBV viral genome loads and expression of BMRF1 (EBV early lytic transcript gene) mRNA levels in Raji and B95.8 cells. 9 Angelicin significantly reduces the number of KSHV lytic replication via inhibition of RTA protein expression and reducing KSHV viral genome loads in BC-3G and BCBL-1 cells. 10. Angelicin is more effective in reducing MHV-68 plaque formation as compared to psoralen. 11. Psoralen is more effective in reducing KSHV lytic replication as compared to angelicin. 12. Angelicin and psoralen are equal in reducing EBV lytic replication. |

(Cho et al., 2013) | |

| Erythroid differentiation | 1. Human leukemic K562 cell line 2. two-phase liquid culture of human erythroid progenitors isolated from peripheral blood samples of normal donors |

1. Angelicin was incubated with K562 cells for up to 7 days to determine the effect of angelicin on the proliferation and differentiation of the cells. 2. K562 cells were incubated with angelicin for 5 days to determine the mRNA content of γ and α- globin. 3. Compounds were added on day 4–5 of phase II culture in two-phase liquid culture before harvesting the cells on day 12. |

1. K562 cell proliferation: 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, and 1mM angelicin 2. K562 cell differentiation: 50, 100, 200, and 400μM angelicin 3. Determination of γ and α-globin mRNA expression level in K562 and two-phase culture: 200μM angelicin • 120 μM hydroxyurea was used as a positive control in Determination of γ and α-globin mRNA expression level in two-phase culture |

1. Angelicin caused dose-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation and differentiation of K562 cells 2. Differentiation of K562 cells based on the percentage of benzidine positive cells: (a) Angelicin at 400 μM = 60.6 ± 6.2 (b) Angelicin at 200 μM = 48.7 ± 7.7 (c) Cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C) at 1 μM = 78.3 ± 4.1 (d) Mithramycin at 50 mM = 85.6 ± 7.2 (e) Cisplatin at 6 μM = 62.5 ± 7.8 (f) Butyric acid at 2.4 mM = 35.3 ± 3.7 3. Angelicin induces 44.9 fold increase as compared to ara-C (18-fold increase) in γ-globin mRNA in K562 cells 4. Angelicin induces high increase of γ-globin mRNA and a low increase in α-globin mRNA. The increase in γ-globin for angelicin is 20.4 fold induction as compared to hydroxyurea that only increased induction by 6.6 fold. 5. HPLC analysis of HbF in angelicin treated cultures increased from 1.4 ± 0.6% in control cells to 11.2 ± 3.8%. Hydroxyurea increased to 4.8 ± 0.9%. |

(Lampronti et al., 2003) |

| 1. Human leukemic K562 cells 2. two-phase liquid culture isolated from peripheral blood samples of normal donors |

1. Pre-irradiated solutions of 5 -MOP, 8-MOP, and angelicin with 16 Jcm-2 UVA were incubated with K562 cells for 5, 6, and 7 days. 2. Pre-irradiated solutions of 5-MOP, 8-MOP, and angelicin with UVA with 16 Jcm-2 were added on day 4-5 of phase II and cells were harvested on day 7. |

5, 10, 15, and 20 μM of compounds | 1. Angelicin photoproducts increase erythroid differentiation dose-dependently. A modest reduction of cell viability is seen dose-dependently after incubation for 6 days. 2. The erythroid differentiating properties of angelicin photoproducts is significantly reduced under anaerobic conditions compared to aerobic conditions. 3. Angelicin photoproducts significantly increase HbA and HbF after 7 days of incubation in two-phase culture system. HbF fold increase is higher than HbA fold increase. Angelicin photoproducts induced a higher fold increase in both HbA and HbF as compared to 5-MOP and 8-MOP. |

(Viola et al., 2008) |

Figure 3.

Potential bioproperties of the furocoumarin, angelicin, as an anti-cancer, anti-inflammation, anti-viral, anti-periodontitis, erythroid differentiating, and pro-osteo- and chondrogenic therapeutic agent.

Natural Occurrence of Angelicin

Both psoralen and angelicin can be found in plants from the Leguminosae (Fabaceae), Apiaceae (Umbelliferae) and Moracea family. However, not all plants produce both these furocoumarins. In the Rutaceae family, which encompasses the citrus fruits, only linear isomers were produced (Pathak et al., 1962; Zobel and Brown, 1991). No plant has so far been found that produces only angular furocoumarin; the plants studied so far have always found to be either produce both isomers or linear isomers alone. This finding suggests that angular furocoumarins came later from an evolutionary viewpoint than linear furocoumarins (Dueholm et al., 2015). The existence of angular furocoumarin was hypothesized to be an evolutionary advantage over insects that can metabolize linear furocoumarins. An example is the larvae of Papilo polyxenes or the Black Swallowtail butterfly that produces microsomal cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (P450s)- an enzyme that can catalyze the metabolism of linear furocoumarins. However, angular furocomarins such as angelicin can bind to the active sites of these enzymes, inhibiting the enzyme from metabolizing the toxic linear furocoumarin (Ma et al., 1994; Wen et al., 2006). This shows that there was an evolutionary need for plants to develop angular furocoumarin, even though it is less cytotoxic than its sister isomer. In this review, the list of plants that produce angelicin is tabulated in Table 2. Other extracted compounds are also included. From the table, it can be seen that the percentage yield of angelicin and the other compounds not only changes with the type of plants but also with the part of plant and season, suggesting as mentioned above that these compounds could be produced to act as a defence system against diseases or pests. Other than that, the other listed plants were also used traditionally as medicine. However, whether the compounds contribute individually or accumulatively to the traditionally believed “medicinal” attributes of the plant is still unclear and under research.

Table 2.

Plants containing angelicin and its traditional uses.

| Plant | Family | Geographical location | Parts containing angelicin | Percentage of reported compounds | Traditional medicine uses | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angelica shikokiana | Umbelliferae/Apiaceae | Japan | Aerial parts | 1. α-glutinol (0.0097% 68mg) 2. β-amyrin (0.0014%, 10mg) 3. Isoxypteryxin (0.0017%, 12mg) 4. Isoepoxypteryxin 0.26%, 1.8g) 5. Angelicin (0.0043%, 30mg) 6. β-sitosterol glucoside (0.005%, 35mg) 7. Bergapten (0.0014%, 10mg) 8. Psoralen (0.0019%, 13mg) 9. Hyuganin C (0.001%, 7mg) 10. Hyganin E (0.002%, 14mg) 11. Hydroxymethyl-2-furaldehyde (0.001%, 7mg) 12. Kaempferol (0.0086%, 60mg) 13. Luteolin (0.0073%, 51mg) 14. Methyl chlorogenate (0.005%, 35mg) 15. Chlorogenic acid (0.0023%, 16mg) 16. Quercetin (0.0041%, 29mg) 17. Kaempferol glucoside (0.0087%, 61mg) 18. Kaempferol rutinoside (0.0014%, 10mg) 19. Adenosine (0.0014%, 10mg) *Percentage calculated based on 10kg powdered dried aerial parts |

Treating digestive and circulatory systems diseases | (Mira and Shimizu, 2015; Mira and Shimizaru, 2016) |

| Angelica sylvestris L. var. sylvestris | Umbelliferae/Apiaceae | Europe and Asia Minor | Aerial parts | 1. Angelicin (0.31 ± 0.015 mg/100g) 2. Imperatorin (2.36 ± 0.033 mg/100g) *Compounds were extracted from aerial parts of the plant. |

Stimulate appetite, treat anorexia, anaemia, vertigo, influenza, dizziness, migraine, and bronchitis, relieve cough, sore throat, indigestion and cold | (Sarker et al., 2003; Mira and Shimizu, 2016; OrHan et al., 2016) |

| Bituminaria basaltica | Fabaceae/Leguminosae | Italy | Aerial parts | 1. angelicin (0.0008%, 10mg) 2. psoralen (0.0002%, 3mg) 3. plicatin B (0.0005%, 6mg) 4. erybraedin C (0.0037%, 46mg) 5. 3,9-dihydroxy-4-isoprenyl-pterocarpan (0.0014%, 17mg) 6. isoorientin (0.0003%, 4mg) 7. daidzin (0.0005%, 6mg) 8. bitucarpin A (0.001%, 12mg) *Percentage calculated based on 1220g air dried and powdered aerial parts |

Disinfection to treat wounds, hair restoration, urinary infections | (Minissale et al., 2013; Bandeira Reidel et al., 2017) |

| Bituminaria bituminosa. L | Fabaceae/Leguminosae | Mediteranian Europe and Maaronesia | Leaves and stems | Average mean concentration of compounds in dry matter from 7 populations: (a) Leaves: 1. Angelicin (4.59 g/kg in the summer; 6.58g/kg in the autumn) 2. Psoralen (6.15g/kg in the summer; 5.59g/kg in the autumn) 3. (E)- werneria chromena (0.15g/kg in the summer; 0.10g/kg in the autumn) 4. Plicatin B (2.10g/kg in the summer; 0.99g/kg in the autumn) 5. Bitucarpin A (1.32g/kg in the summer; 1.49g/kg in the autumn) 6. Morisianin (0.02g/kg in the summer; 0.01g/kg in the autumn) 7. Erybraedin C (0.57g/kg in the summer; 0.27g/kg in the autumn) (b) Stems: 1. Angelicin (2.37g/kg in the summer) 2. Psoralen (2.55g/kg in the summer) |

Vulnerary, disinfectant and cicatrising | (Azzouzi et al., 2014; Pecetti et al., 2016) |

| Bituminaria morisiana | Fabaceae/Leguminosae | Sardinia Italy | Seed | 1. Morisianine (0.003%, 2.7mg) 2. Erybraedin C (0.018%, 18.5mg) 3. Angelicin (0.014%, 13.8mg)4. Psoralen (0.006%, 5.6mg) *Percentage calculated based on 100.9g air-dried and powdered seeds |

(Not found) | (Pistelli et al., 2003; Leonti et al., 2010) |

|

Cicuta virosa Linnaeus (water hemlock) |

Umbelliferae/Apiaceae | Russia, Japan, China | Dried whole plant | 1. 11,110 -dimer of scopoletin (0.83%, 25mg) 2. 11-O-b-glucopyranosylhamaudol (1.17%, 35.2mg) 3. Isobyakangelicin (1.54%, 46.3mg) 4. Psoralene (1.27%, 38.1mg) 5. Angelicin (2.02%, 60.5mg) 6. Prim-O-glucosylangelicain (1.44%, 43.1mg) 7. Apiosylskimmin (1.86%, 55.8mg) 8. Rutin (1.18%, 35.3mg) 9. Quercetin-3-Ob-D-rhamnoside (2.61%, 78.3mg) *Percentage calculated based on 3kg air dried powder plant material |

Lethal poisoning toward humans | (Uwai et al., 2000; Tian et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2016) |

|

Ficus carica (Common Fig) |

Moracea | Tropical and sub-tropical countries | Fruit | (A) Volatile compounds extracted from figs of Ficus carica by Gibernau and team. Compounds labelled with an asterisk are those that were tentatively identified with mass spectrophotometer library. The yield and original weight of the compounds were not reported. 1. Benzyl aldehyde (2 isomers) 2. Benzyle alcohol 3. Furanoid (cis) linalool oxide 4. Furanoid (trans) 5. Pyranoid (cis) linalool oxide 6. Pyranoid (trans) 7. Cinnamic aldehyde 8. Indole 9. Cinnamic alcohol 10. Eugenol 11. trans-Caryophyllene 12. Sesquiterpene 1 13. Sesquiterpene 2 14. Sesquiterpene 3 15. Sesquiterpene 4 16. Sesquiterpene 5 17. Hydroxycaryophyllene 18. Oxygenated sesquiterpene 1 19. Oxygenated sesquiterpene 2 20. Angelicin* 21. Bergapten* (B) Coumaric compounds obtained in the month of June only and their relative concentrations based on FID peak areas of n-hexane or dichloromethane fraction by Marrelli and team. 1. Psoralen (23.30%) 2. 8-methoxypsoralen (3.65%) 3. Angelicin (2.5%) 4. Bergapten (15.20%) 5. Rutaretin (21.10%) 6. Pimpinellin (1.9%) 7. Seselin (19.5%) *Weight of Ficus samples for extraction: 300g *List of relative concentration (based on FID peak fractions) for major fatty acids, sterols and terpenes obtained from the month of June, July and September can be viewed in the original article by Marrelli and team. |

Anti-pyretic, aphrodisiac, inflammation, paralysis, purgative, control haemorrhages | (Gibernau et al., 1997; Marrelli et al., 2012) |

| Heracleum maximum | Umbelliferae/Apiaceae | North America | Roots | 1. (3R,8S)-Falcarindiol (0.037%, 37mg)2. Bergapten (0.015%, 15mg)3. Isobergapten (0.031%, 31mg)4. Angelicin (0.005%, 5mg)5. Sphondin (0.023%, 23mg)6. Pimpinellin (0.029%, 29mg)7. Isopimpinellin (0.033%, 33mg)8. 6-Isopentenyloxyisobergapten (%, 1mg) *Percentage calculated based on 100g freeze dried roots |

Infectious diseases and respiratory ailment including tuberculosis | (O׳Neill et al., 2013; Bahadori et al., 2016) |

| Heracleum meoellendorffi | Umbelliferae/Apiaceae | Korea and China | Roots | 1. Angelicin (21.43%, 300mg) 2. Isobergapten (12.14%, 170mg) 3. Pimpinellin (41.43%, 580mg) 4. (3S, 4R)-3, 4-epoxypimpinellin (14.07%, 197mg) *Percentage calculated based on 1.4kg air dried roots |

Common cold, headache and analgesics | (Bahadori et al., 2016; Yeol Park et al., 2017) |

|

Heracleum persicum (Persian hogweed) |

Umbelliferae/Apiaceae | Iran | Roots | 1. Psoralen (0.013%, 2mg) 2. Bergapten (0.106%, 15.9mg) 3. Xanthotoxin (0.117%, 17.6mg) 4. Isopimpinellin (0.089%, 13.3mg) 5. Angelicin (0.017%, 2.5mg) 6. Isobergapten (0.135%, 20.3mg) 7. Sphondin (0.085%, 12.8mg) 8. Pimpinellin (0.371%, 55.6mg) 9. Beratomin (0.039%, 5.8mg) 10. 5-methoxyheratomin (0.015%, 2.3mg) 11. Moellendorffiline (0.038%, 5.7mg) 12. Fraxetin (0.011%, 1.7mg) *Percentage calculated from 15g n-hexane extract of dried and grounded roots |

Anti-flatulence, digestive, anti-infection, pain killer and tonic agent | (Bahadori et al., 2016; Dehghan et al., 2017) |

| Heracleum platytaenium | Umbelliferae/Apiaceae | Turkey | Aerial parts | 1. Xanthotoxin (2.97 ± 0.019 mg/100g) 2. Angelicin (1.74 ± 0.033 mg/100g) 3. Isopimpinellin (0.31 ± 0.003 mg/100g) 4. Bergapten (2.51 ± 0.045 mg/100g) 5. Pimpinellin (7.73 ± 0.159 mg/100g) 6. Osthol *Compounds were extracted from aerial parts of the plant. |

Gastric, epilepsy, enteritis | (Dincel et al., 2013; Bahadori et al., 2016; OrHan et al., 2016) |

| Heracleum rawianum | Umbelliferae/Apiaceae | Iran | Aerial parts of the plant | 1. Angelicin (0.12%, 5.9g) 2. Allobergapten (0.00056%, 28mg) 3. Sphondin (0.00066%, 33mg) *Percentage calculated based on 5kg aerial parts of the plant |

Antiseptic, carminative, digestive and analgesic | (Mahmoodi Kordi et al., 2015; Bahadori et al., 2016) |

| Heraculeum thomsoni | Umbelliferae/Apiaceae | India | Aerial parts | 1.Angelicin (0.0138% yield) 2. Psoralen (not mentioned) 3. heratomin (not mentioned) 4. Sphondin (not mentioned) 5. Bergaptol (not mentioned) 6. Apterin (not mentioned) *Weight of the aerial parts of the plant: 2.05kg |

(Not found) | (Patnaik et al., 1988) |

|

Pastinaca sativa (parsnip) |

Umbelliferae/Apiaceae | North America | Leaf, seeds, roots, and shoots | (A) Biosynthethic pathway of angelicin and psoralen were studied in the leaves and seeds by Munakata and team. (B) Compounds extracted from the roots and shoots. The yield or initial plant weight was not mentioned by Lohman and McConnaughay. 1. Angelicin 2. Bergapten 3. Imperatorin 4. Isopimpinellin 5. Xanthotoxin 6. Sphondin |

Sudorifics and diuretics | (Baskin and Baskin, 1979; Hendrix, 1984; Berenbaum et al., 1991; Lohman and McConnaughay, 1998; Waksmundzka-Hajnos et al., 2004; Munakata et al., 2016) |

| Pleurospermum brunonis | Umbelliferae/Apiaceae | Pakistan | Aerial parts | 1. 5-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-6-methoxyangelicin (0.001%, 21mg) 2. Ferulic acid (0.0015%, 29mg) 3. Angelicin (0.0045%, 89mg) *Percentage calculated from 2kg air dried and powdered aerial parts of the plant |

Fever, analgesic, headache | (Sharma et al., 2005; Ikram et al., 2015; Rather et al., 2017) |

| Psoralea corylifolia L. | Fabaceae/Leguminosae | Malay peninsula, Indonesia, China, Taiwan | Fruit | (A) Yield reported by Lin and team 1. Bakuchiol (0.85%, 8.5g) 2. Psoralen (0.32%, 3.2g) 3. Angelicin (0.34%, 3.4g) *Percentage calculated based on 1kg pulverized plant (part of the plant was not mentioned) were (B) Yield reported by Chen and team 1. 7-O-Methylcorulifol A (0.00012%, 4.5mg) 2. 7-O-Isoprenylcorylifol A (0.00012%, 4.5mg) 3. 7-O-Isoprenylneobavaisoflavone (0.00011%, 4.1mg) 4. Angelicin (0.0027%, 10.4mg) 5. Psoralen (0.0001%, 3.9mg) 6. Bakuchiol (0.00011%, 4.3mg) 7. 12,13-dihyro-12,2-epoxybakuchiol (0.00012%, 4.5mg) 8. p-hydroxybenzaldehyde (0.0002%, 7.6mg) 9. Bavachalcone (0.000095%, 3.6mg) 10. Psoralidin (0.00012%, 4.5mg) 11. β-sitosterol 12. Stigmasterol (Combination β-sitosterol and stigmasterol: 0.0035%, 128mg) *Percentage calculated based on 3.8kg dried fruit |

Spermatorrhea, backache, vitiligo, callus, knee pain, pollakiuria, enuresis, premature ejaculation, alopecia, psoriasis, asthma, nephritis | (Prasad et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2007; Choi et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2017) |

|

Sanicula lamelligera Hance (Fei-Jing-Cao) |

Umbelliferae/Apiaceae | North America and China | Dried whole plant | 1. Angelicin (0.00016%, 40mg) 2. Isoferulaldehyde (0.00002%, 5.1mg) 3. Hydroxybakuchiol (0.00011%, 27mg) 4. 22-angeloyl-R1-barrigenol (0.000013%, 3.2mg) 5. 5, 6, 7, 8, 4'-pentamethoxyflavone (0.00017%, 42.6mg) 6. 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 3',4'-heptamethoxyflavone (0.000053%, 13.2mg) 7. Isobavachin (0.00012%, 30.5mg) 8. Isoliquiritigenin (0.000018%, 4.5mg) 9. Furano(2”, 3”, 7, 6)-4'-hydrpxyflavone (0.000036%, 9mg) *Percentage based on dried whole plant 25kg |

Colds, asthma, bleeding, cough, gall, chromic chest pains, mild cattarhs, wounds, and amenorrhea | (Naylor et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2015) |

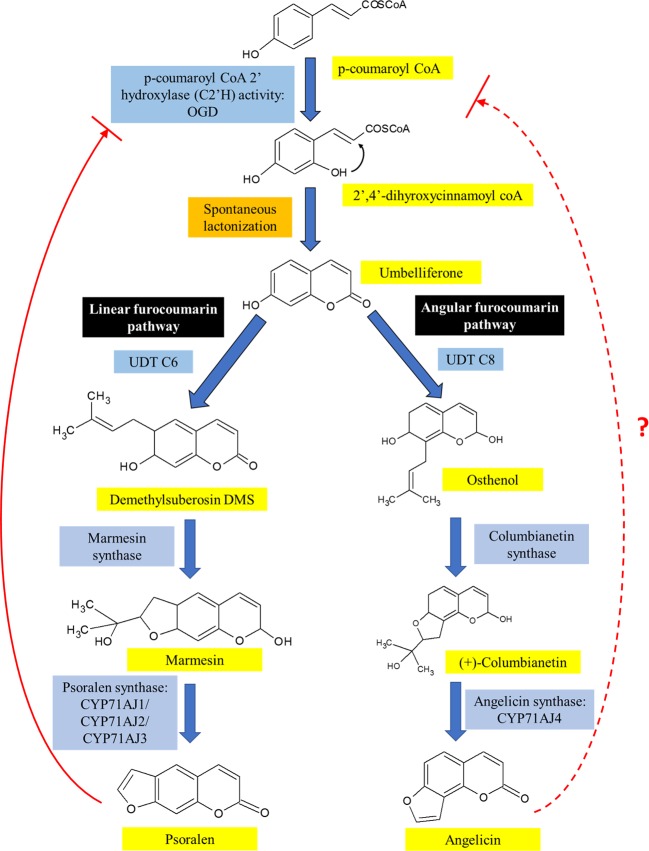

A summary of the biosynthesis of both angelicin and psoralen is illustrated in Figure 4. Umbelliferone is the precursor compound of both linear and angular furocoumarins. Umbelliferone is an intermediate 7-hydroxycoumarin derived from p-coumaryl CoA that has undergone ortho-hydroxylation via p-coumaroyl coA2'hyroxylase (C2'H) activity. In Ruta graveolens L. 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase (OGD) was found to synthesise 2,4-dihydroxycinnamoyl CoA which then transforms into umbelliferone after spontaneous closure of the lactone ring under acidic or neutral conditions independent of enzymes. Further investigation had also discovered that psoralen acts as negative feedback against C2'H activity to prevent excessive production of psoralen in the plant (Vialart et al., 2012). It is not known if angelicin is also involved in the negative feedback loop against C2'H activity.

Figure 4.

The biosynthesis pathway of linear and angular furocoumarin in plants. Both psoralen and angelicin come from the same precursor, umbelliferone, which had been modified differently to form both linear and angular furocoumarin pathways. Though psoralen is able to act as a negative feedback against C2'H activity, it is not known yet if angelicin is also involved in the negative feedback loop.

After umbelliferone, the distinction of both linear and angular furocoumarin biosynthesis happens based on the prenylation position of umbelliferone at C6 or C8 by umbelliferone dimethylallyltransferase (UDT). UDT is a prenyltransferase that synthesizes demethylsuberosin (DMS) at C6 position of umbelliferone and ostenol at the C8 position (Karamat et al., 2013; Munakata et al., 2016). The synthesis of DMS would lead to the formation of psoralen while osthenol is the precursor of angelicin. DMS is then catalyzed by both marmesin synthase and psoralen synthase to form psoralen itself (Hamerski and Matern, 1988; Larbat et al., 2008; Roselli et al., 2017). On the other hand, for angular furocoumarins, osthenol is catalyzed by columbianetin synthase to form (+)-columbianetin (Roselli et al., 2017). Angelicin synthase then catalyzes the conversion of (+)-columbianetin to angelicin through the abstraction of syn-C3'-hydrogen (Larbat et al., 2008). The first to discover angelicin synthase were Larbat and colleagues who isolated the parsnip variant of angelicin synthase (CYP71AJ4) together with its complementary psoralen synthase, CYP71AJ3, using the genomic sequence of psoralen synthase isolated from Ammi majus (Larbat et al., 2008; Munakata et al., 2016). They also discovered that the genes for angelicin synthase and psoralen synthase from the CYP71AJ subfamily of parsnip share 70% similarity with each other, but the portions were believed to code for active substrate sites sides only showed 40% similarity (Larbat et al., 2008). A recent journal article reported that using bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) library, it was identified that both CYP71A3 and CYP71A4 genes were only separated by approximately 7.6 kb. Both genes also sit in a cluster on a separate chromosome from the cluster where UDT C6 and p-coumaryl CoA 2'hydroxylase genes, were located. Genes transcribing the enzymes involved upstream of the furocoumarin biosynthesis pathway were seen to cluster together with both UDT C6 and p-coumaryl CoA genes, while the other P450 genes were clustered together with CYP71A3 and CYP71A4 genes (Roselli et al., 2017). This study goes against the common idea that genes from a similar self-defence pathway would be found together as an evolutionary advantage. It could be possible that further downstream genes can be found on a separate cluster or anywhere separately on the genome. Further studies still need to be done to fully understand the biosynthesis of psoralen and angelicin including its location on the genome and the co-localization within the plant cell.

Anti-Cancer and Anti-Tumor Properties

In the year 2013, cancer claimed the lives of 8.2 million people worldwide, making it the world's second leading cause of death, second only to cardiovascular diseases. In 2013 alone, there were 14.9 million new cases of cancer reported (Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration, 2015). For women, breast cancer remains the most prevalent cancer, while for males, lung cancer tops the chart in developed and developing countries. Prostate cancer is also on the rise for men at the global level; and cervical cancer shows a similar trend among women (Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration, 2015; Torre et al., 2015). Colorectal, stomach, and liver cancer are the next most frequently diagnosed cancers globally. Many factors are believed to contribute to the increased incidence of cancer including lifestyle behaviors which have become more common over the decades such as smoking, physical inactivity, poor diet and later dates of first births—all of which have been suggested to increase the risk of cancer (Torre et al., 2015).

The basic hallmarks of cancer include its ability to evade the immune system, resist cell death and growth suppressors, maintain cell proliferation, induce angiogenesis as well as activate invasion and metastasis (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). These properties make cancer a difficult disease to manage and eradicate. However, by targeting apoptotic pathways, such as the AKT pathway, MAPK pathway, and modulating the expression of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins, anti-cancer drugs can slow the progress and even reduce the spread of cancer (Wong, 2009; Falasca, 2010). Another key factor for a good anti-cancer drug is that the drug should have as specific as possible cytotoxicity toward cancer cells only while sparing healthy cells as much as possible. Therefore, natural products have become the research focus as they are easily obtained, safer to use and have low toxicity (Pratheeshkumar et al., 2012).

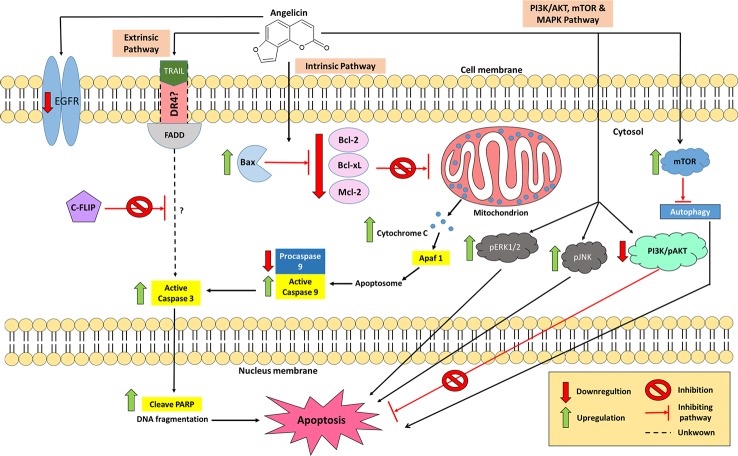

Many studies have been conducted to test for anti-cancer properties in angelicin, with several of these demonstrating angelicin's ability to reduce the cell viability of human prostate cancer (PC-3), human epithelioma (Hep2), colorectal carcinoma (HCT116), rhabdomyosarcoma (RD), human cervical carcinoma (HeLa) cell line, cervical squamous cell carcinoma (SiHa) cell line and human breast adenocarcinoma (MCF7) cell lines (Mira and Shimizu, 2015; Wang et al., 2015a; Wang et al., 2019b). Historically, the first cell line tested which showed angelicin's anti-cancer properties was the neuroblastoma (SH-SY5Y) cell line, which are cells derived from a metastatic bone tumor biopsy. It was found that when treated with angelicin, upregulation of both caspase 3 and 9 could be seen. In addition, anti-apoptotic proteins were also affected by angelicin in SH-SY5Y cells. Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl-1 proteins were seen to decrease their expression levels together with procaspase 9 (Rahman et al., 2012; Kovalevich and Langford, 2013). Irregularity in the regulation of the anti-apoptotic proteins is one of the factors that contribute to the development of cancer as overexpression of them blocks apoptosis and makes the cells resistant to anti-cancer drugs (Oltersdorf et al., 2005). When decreased in its expression, cancer cells became less resistant to anti-cancer therapies (Webb et al., 1997). Hence, the changes seen in the expression of apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins by angelicin is a positive indicator that angelicin has anti-cancer properties. Besides that, several different cells, such as promyelocytic leukaemia (HL-60), human lung cancer (A549), hepatoblastoma (HepG2), and hepatocellular carcinoma (Huh-7) cell lines, also yielded the same changes in the proteins mentioned above when incubated with angelicin for 24 or 48 h (Yuan et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017a). This shows that angelicin has the potential to be effective against multiple cancer cell lines. Besides seeing a decreased expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, increased expression of apoptosis-inducing Bcl-2 family, Bax, was also reported in the treated cell lines. Even the expression levels of cytochrome C was increased dose-dependently when tested in HepG2 and Huh-7 cells (Wang et al., 2017a). An increase in the expression of cytochrome C and Bax had been known to indicate the activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. This is because Bax protein causes the permeation of the mitochondrial outer cell membrane, thus releasing cytochrome c into the cytosol, which then triggers the caspase 3 and 9 cascades, mediating apoptotic programmed cell death (Fulda and Debatin, 2006; Ashkenazi, 2008). Hence, based on what had been reported, it is possible that angelicin mainly induces cell death via the intrinsic apoptotic pathway in various cancer cell lines.

Having demonstrated possible activity in inducing apoptosis via the intrinsic pathway, the possibility of angelicin to have effects on the extrinsic pathway was also studied. In human SH-SY5Y cells no changes in the regulation of FAS receptor, FAS ligand and caspase 8 were seen, suggesting that the FAS pathway may not be activated by angelicin (Rahman et al., 2012). On the contrary, human renal carcinoma (Caki) cells displayed a different kind of result when incubated with angelicin. Caki cells have always been known to be one of those cancer cell lines that are resistant to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL) (Han et al., 2016). When the compound was tested alone, angelicin was not able to induce apoptosis, yet when incubated together with 50 ng/ml of TRAIL the combined treatment was able to promote cell death (Min et al., 2018). Further investigation then went on to show how this combination treatment was even more effective than cycloheximide in downregulating cellular FLICE (FADD-like IL-1β- converting enzyme)-inhibiting protein (c-FLIP) post-translationally. Active caspase 3 was also upregulated and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase was also cleaved, confirming cell apoptosis, though the mechanism was independent of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling. Also, there were no changes with death receptor 5 (DR5) as well as the other intrinsic related apoptosis proteins, which suggest that angelicin does not induce apoptosis through the intrinsic pathway or DR5 in the Caki cells. There were also no changes in the inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAP) family, which includes cIAP1, XIAP, and survivin. Interestingly, the pro-apoptotic protein Bim was shown to increase in its expression when Caki cells which were only treated with angelicin; however, combination treatment with TRAIL attenuated the effect. The combination treatment of angelicin and TRAIL was able to induce apoptosis in other cancer cell lines, such as Sk-hep1 and MDA-MB-361 cells but normal cell lines were not affected (Min et al., 2018). This is a good therapeutic option to be exploited as this combination treatment could have the potential to be used as targeted cancer therapy toward cancer cell lines that are resistant to TRAIL.