Abstract

MEK inhibitors (MEKi) demonstrate anti-proliferative activity in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma, but responses are short-lived. In the present study, we evaluated the MEKi trametinib alone and in combination with drugs targeting epigenetic regulators, including DOT1L, EZH2, LSD1, DNA methyltransferases, and histone acetyltransferases. The DNA methyltransferase inhibitor (DNMTi) decitabine effectively enhanced the anti-proliferative activity of trametinib in cell viability, colony formation, and 3D organoid assays. RNA-Seq analysis showed the MEKi-DNMTi combination primarily affected the expression of genes involved in G1 and G2/2M checkpoints, cell survival, chromosome segregation and mitotic spindle. The DNMTi-MEKi combination did not appear to induce a DNA damage response (as measured by γH2AX foci) or senescence (as measured by β-galactosidase staining) compared to either MEKi or DNMTi alone. Instead, the combination increased expression of the CDK inhibitor p21 and the pro-apoptotic protein BIM. In vivo, the DNMTi-MEKi combination was more effective at suppressing growth of MP41 uveal melanoma xenografts than either drug alone. Our studies indicate that DNMTi may enhance the activity of MEKi in uveal melanoma.

Keywords: adaptation, DNMT, epigenetics, MEK, uveal

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Uveal melanoma is derived from the cranial neural crest-derived uveal melanocytes of the eye (Harbour, 2012). In contrast to cutaneous melanoma, uveal melanoma is not strongly associated with exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, exhibits a much lower mutational burden, and is instead characterized by a high prevalence of initiating mutations in the G-alpha-q subunits GNAQ and GNA11 (Van Raamsdonk et al., 2009). The most common GNAQ and GNA11 mutations occur at position Q209 and lead to their constitutive activation by abrogating GTP hydrolase activity. GNAQ/11 mutations function in an analogous fashion to Ras mutations and activate multiple signaling pathways involved in oncogenic transformation, including the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and YAP/Hippo pathways (Chen et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2014). Among these, FDA-approved drugs exist only for the MAPK pathway, with MEK inhibitors being FDA-approved for unresectable BRAF-mutant cutaneous melanoma. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that MAPK signaling is required for the growth of uveal melanoma cell lines in vitro, with MEK inhibitors (MEKi) being found to have anti-proliferative activity in the single-agent setting (Ambrosini, Khanin, Carvajal, & Schwartz, 2014; Ambrosini et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2017, 2015; Faiao-Flores et al., 2019). The therapeutic utility of MEKi have also been explored clinically in advanced uveal melanoma. In a phase II clinical trial of advanced uveal melanoma, treatment with the single agent MEKi selumetinib was associated with some responses and an increase in the progression-free survival from 7 to 16 weeks (Carvajal et al., 2014). Unfortunately, this was not replicated in later studies, and a trial of selumetinib plus dacarbazine failed to show any benefit over dacarbazine alone in a phase III double-blind clinical trial (Carvajal et al., 2018). Studies in multiple cancers have shown that tumor cells rapidly adapt to kinase inhibitors through the adoption of a drug-tolerant state, which is often epigenetically mediated. Indeed, epigenetic drugs such as pan-HDAC inhibitors increase the efficacy of drugs targeting EGFR, JAK, p38 MAPK and RAF (Emmons et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2010). The goal of the present study was to evaluate a series of clinical-grade epigenetic inhibitors to identify candidates that may increase the activity of MEKi in uveal melanoma. We focused on epigenetic inhibitors as there is evidence from BRAF-mutant cutaneous melanoma that epigenetic inhibitors can limit adaptation to BRAF inhibition (Emmons et al., 2019; Shao & Aplin, 2012).

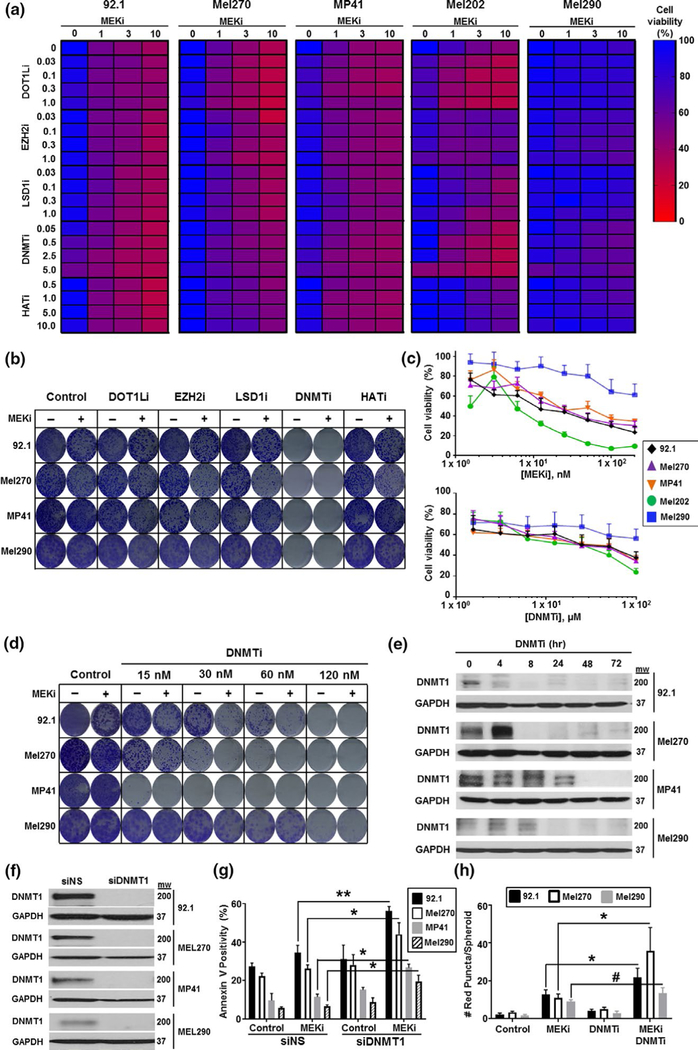

The MEKi trametinib was investigated in five uveal melanoma cell lines (92.1, Mel270, MP41, Mel202 and Mel290) as both a single agent and in combination with inhibitors of disruptor of telomeric silencing 1-like (DOTL1i, pinometostat), enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2i, tazemetostat), lysine-specific histone demethylase-1 (LSD1i, GSK2879552), DNA methyl transferase (DNMTi, decitabine), and histone acetyl transferase (HATi, anacardic acid). Using MTT cell viability assays, the five cell lines exhibited considerable variation in their responses to the inhibitors, with the DOT1Li and DNMTi compounds demonstrating the strongest activity in combination with the MEKi (Figure 1a). Consistent with the well-established delay for DNMTi to manifest their anti-proliferative effects, we found in long-term colony formation assays that DNMTi also had a significant single-agent activity in every cell line tested (Figure 1b). Adjustment of the dosing of the DNMTi alone based upon its single-agent activity (Figure 1c) demonstrated that DNMTi treatment enhanced the effects of trametinib in the 92.1, MP41, Mel290, and Mel270 uveal melanoma cells (Figure 1c). Silencing of BAP1 increased the responses to single agent MEKi and DNMTi in 92.1 cells, but not the Mel202 cells (Figure S1a,b). It was further noted that neither drug alone or in combination had significant effects upon untransformed human UMC025 and UMC026 uveal melanocytes (Figure S2).

FIGURE 1.

Decitabine improves the responses to trametinib in uveal melanoma cell lines. (a) Effects of epigenetic inhibitors and trametinib (MEKi) on cell viability in a panel of uveal melanoma cell lines. 92.1, Mel270, MP41, Mel202, and Mel290 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of trametinib (0–10 nM) alone and in combination with inhibitors of DOTLi, EZH2, LSD1, DNMT, or HAT for 72 hr before cell viability was measured using an MTT assay. (b) Effects of epigenetic inhibitors and trametinib in long-term colony formation assays. Cells were grown in the presence of drug for 4 weeks, with drugs changed every two days before being stained with crystal violet. (c) Single-agent activity of trametinib (MEKi, top panel) and decitabine (DNMTi, lower panel) in a panel of uveal melanoma cell lines. Cells were treated with drug for 72 hr before cell viability was measured by an MTT assay. (d) Decitabine has concentration-dependent effects upon MEKi activity in long-term colony formation assays. Cells were treated with decitabine (DNMTi 0–120 nM) alone and in combination with trametinib (MEKi, 1 nM) for 4 weeks before being stained with crystal violet. (e) Treatment with decitabine inhibits DNMT1 protein expression. Cells were treated with decitabine (120 nM) for indicated time points and probed for DNMT1 expression by Western Blot. (f, g) Silencing DNMT1 increases sensitivity to trametinib. (f) DNMT1 was silenced using siRNA against the non-targeting control (siNS) or DNMT1 (siDNMT1) for 72 hr and probed for DNMT expression by Western blot. (g) Cells were silenced with siNS or siDNMT1 and treated with trametinib (MEKi, 10 nM) for 72 hr. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for Annexin V positivity. (h) Treatment with trametinib and decitabine increased cell death in 3D uveal melanoma spheroid assays. Cells were implanted into collagen and treated for 72 hr with vehicle, trametinib (MEKi, 10 nM), decitabine (DNMTi, 120 nM), or the combination (MEKi + DNMTi) before being stained with Calcein-AM and propidium iodide (PI). Pl-positive cells were quantified as a readout of cell death after drug treatment. To determine significance, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used followed by a post hoc t test. Significant differences between the control and treated groups are indicated by **p < .01 and *p < .05

DNMTi compounds such as decitabine (also known as 2’-deoxy-5-aza-cytidine) irreversibly inhibit the enzyme DNMT1 by forming DNA adducts that covalently bind to DNMT1, leading to its downregulation (Stresemann & Lyko, 2008). In agreement with this, treatment of uveal melanoma cells with decitabine led to a decrease in DNMT1 protein expression over a 4–24 hr period, depending upon the cell line (Figure 1e). Some modulation in DNMT3 levels were also noted (Figure S3). Silencing of DNMT1 using siRNA also enhanced the response to MEKi in 92.1, Mel270, MP41, and Mel290 uveal melanoma cell lines in both apoptosis and colony formation assays (Figure 1f,g and Figure S4). As DNMTi forms DNA adducts, it has been suggested that these drugs also initiate a DNA damage response (Maes et al., 2014). While DNMTi increased the number of γH2AX foci in 92.1 cells, this was not seen in the MP41 cells, and no increase in foci was detected following treatment with trametinib (Figure S5). It thus seemed unlikely that DNMTi mediated its effects through an increased DNA damage response.

3D organoid cultures can more faithfully model the tumor microenvironment than 2D cell cultures, and they may represent better predictors of in vivo activity (Smalley et al., 2006; Smalley, Lioni, Noma, Haass, & Herlyn, 2008). In 3D organoid-like spheroids using 92.1 Mel270 and Mel290 cells, the MEKi demonstrated some single-agent cytotoxicity, which was enhanced by the addition of the DNMTi, as shown by increased levels of propidium iodide uptake (red staining) and reduced Calcein-AM staining (Figure 1f and Figure S6). Some inhibition of invasion was also noted, suggesting that the MEKi-DNMTi combination could limit metastatic dissemination.

Cancer cells frequently inactivate expression of tumor suppressor genes through promoter methylation (Das & Singal, 2004). DNMTis work in part by reversing this DNA methylation, leading to suppression of tumor cell growth. Diverse effects of DNMTi inhibitors have been reported across cancers, such as myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), where DNMTi compounds exert their anti-proliferative activity by restoring the expression of the cell cycle inhibitor p15INK4b (Lubbert et al., 2011). In triple-negative breast cancer, DNMTi alters the expression of multiple genes implicated in cell cycle control, differentiation, transcription factor activity, cell adhesion, apoptosis, cytokine signaling, the stress response, and metabolism (Schmelz et al., 2005). To better understand how DNMTi modulated the transcriptional responses to MEKi in uveal melanoma, we performed RNA-Seq experiments (Figure 2a). Treatment of 92.1 cells with MEKi alone versus vehicle led to the enrichment of gene signatures implicated in Rho-GTPase driven cytoskeletal remodeling, GPCR signaling, PI3K signaling, MITF, and other pathways involved in metabolism and cell cycle regulation (Figure S7a). Treatment with the DNMTi alone was associated with a decrease in cell cycle pathways and the spindle checkpoint (Figure S7b). Comparison of the DNMTi-MEKi combination to vehicle control demonstrated the suppression of multiple pathways involved in apoptosis, signaling, and Rho-GTPase driven cytoskeleton remodeling (Figure S7c). An analysis of MEKi alone versus the MEK-DNMTi combination identified a significant upregulation of the CDK inhibitor p21, the neurofilament gene NEFH and the apoptosis regulator BCL2L1 (BIM). Key genes that were downregulated included the ribosomal precursor RNA SNORD3A, the histone gene HIST1H3H, the connective tissue growth factor CCN2A, and the cell cycle regulator CDK1. An analysis of the data using Gene Ontology pathway mapping (Figure 2b) and network interaction software was performed. This analysis of global network changes and use of STRING to enrich for specific networks revealed the major genes to be affected by the MEK-DNMTi combination to be those involved in cell cycle and specifically the G1/S transition, G2/M, mitosis, and chromosome segregation (Figure 2b–d). Among some of the most highly connected hubs were genes involved in the mitotic checkpoint and spindle formation including BUB1, CDC20, CDK, KIF23, KIF11, and PRC1(Figure 2d).

FIGURE 2.

The combination of trametinib and decitabine has profound effects upon cell cycle-related genes. (a) Volcano plot of RNA-Seq data showing genes that were significantly changed following treatment with either vehicle control or the decitabine–trametinib combination. Significant changes are denoted by a p-value < .05 in red. (b) Key gene networks identified as changing in response to decitabine-trametinib treatment. Shown are the most significantly changed pathways, along with the −log10(p-value). (c, d) A global gene network interaction analysis identified cell cycle genes as being altered following treatment with decitabine-trametinib. (c) Interactions between significantly changed genes identified in GeneGo were visualized in Cytoscape using the degree sorted circle layout algorithm, with the 16 highest degree nodes identified. (d) Enrichment for protein interactions between significantly changed cell cycle genes was identified in STRING, with interactions surpassing the most stringent threshold of 0.9 being exported and visualized by Gephi visualization software using the OpenOrD algorithm

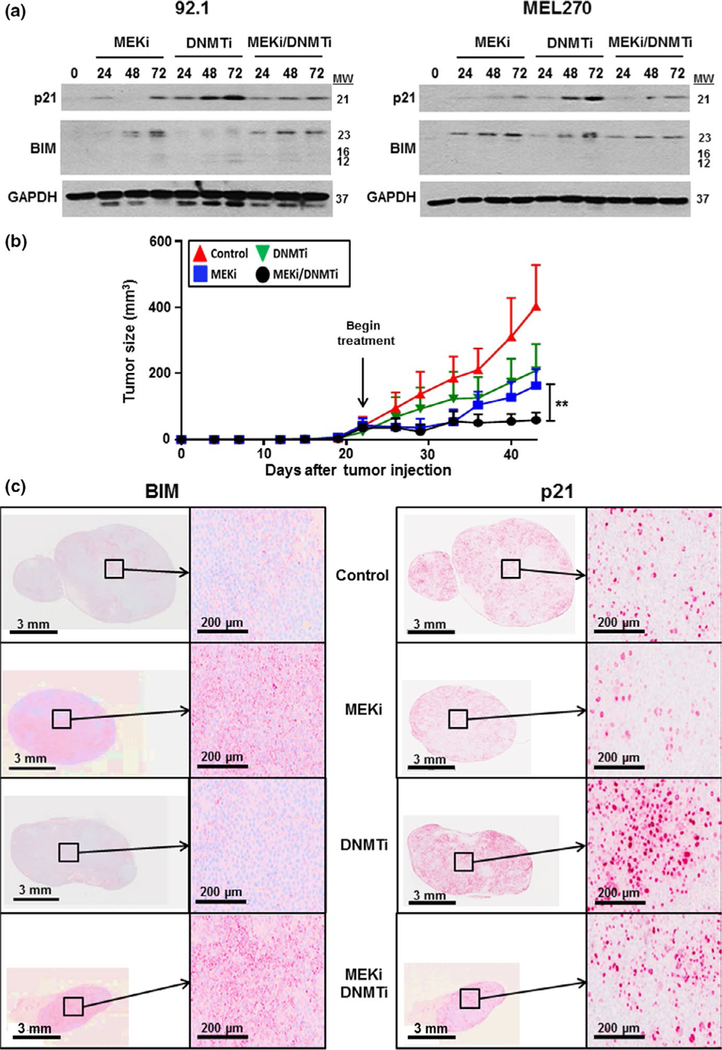

The increase in RNA expression of p21Cip1 and BIM in response to the DNMTi-MEKi combination was also seen at the protein level by Western blot (Figure 3a). In the 92.1 and Mel270 cell lines, it was noted that decitabine led to the strongest upregulation of p21 whereas trametinib induced the most BIM expression (Figure 3a). As exit from the cell cycle can be associated with a senescence-like response, we tested for senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining in uveal melanoma cells treated with either vehicle, DNMTi, MEKi, or the MEKi-DNMTi combination (Figure S8). There was no correlation between any drug treatment and β-galactosidase staining, consistent with a lack of senescence response. Finally, we evaluated the MEKi, DNMTi, and the combination in vivo using a MP41 xenograft model of uveal melanoma. The single agent MEKi provided modest anti-tumor efficacy, and DNMTi monotherapy had little effects upon tumor growth in vivo (Figure 3b). However, the MEKi-DNMTi combination was associated with significant synergy, leading to marked reduction in tumor growth over time (Figure 3b and Figure S9). IHC analysis revealed strong p21 staining in tumors treated with either the DNMTi or the DNMTi-MEKi combination, but not with vehicle or MEKi alone (Figure 3c). Conversely, MEKi alone and the MEKi-DNMTi combination was associated with a strong induction of BIM expression. These findings confirm in vitro findings showing induction of p21 and BIM and suggest that DNA methyl transferase inhibition may be of utility in limiting the escape to MEK inhibitor therapy. Clinically, decitabine is FDA-approved for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes (Lubbert et al., 2011), where it is mostly used in the monotherapy setting. At this time, little is known about whether decitabine could enhance the effects of MAPK pathway-targeted inhibitors. Our studies provide the preclinical rationale for combining decitabine with MEK inhibitors in uveal melanoma, for future evaluation in the clinical setting. The high level of heterogeneity between uveal melanoma cell lines suggests that further investigation of this drug combination across a larger panel of tumors may be warranted.

FIGURE 3.

Decitabine enhances the therapeutic effect of trametinib in an in vivo xenograft model of uveal melanoma. (a) Treatment with decitabine and trametinib increases expression of p21 and BIM in 92.1 and Mel270 uveal melanoma cells. Cells were treated with vehicle, trametinib (MEKi, 10 nM), decitabine (DNMTi, 120 nM), or the two drugs in combination for 0–72 hr and probed for p21 and BIM by Western blot. (b) Decitabine enhances the effects of trametinib in a uveal melanoma xenograft model. Xenografts of MP41 melanoma cells were allowed to engraft for 22 days and subsequently treated with vehicle, decitabine (DNMTi, 0.5 mg/kg 3 times per week), trametinib (MEKi, 1 mg/kg daily), or the two drugs in combination for 21 days. Tumor volumes were measured 2 times per week. (c) BIM and p21 levels are increased after treatment with decitabine and trametinib in vivo. Tumors from (b) were stained for p21 and BIM expression by immunohistochemistry. To determine significance, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used followed by a post hoc t test. Significant differences between the control and treated groups are indicated by **p < .01

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Uveal melanoma cell lines

The uveal melanoma cell lines 92.1, Mel270, MP41, Mel202, and Mel290 were used as previously described (Faiao-Flores et al., 2019). The identities of the cell lines were confirmed through STR validation analysis. All uveal melanoma cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, L-glutamine, and antibiotics at 5% CO2.

2.2 |. Reagents

Pinometostat, tazemetostat, GSK2879552, decitabine, and anacardic acid were purchased from SelleckChem (Houston, TX). Trametinib was purchased from ChemieTek (Indianapolis, IN). For Western blot analysis, antibodies against DNMT1 (ab19905, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), p21 (#2947, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), BIM (#2933, CST), and GAPDH (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA) were used. For immunohistochemistry analysis, antibodies against p21(#2947, CST) and BIM (ab32158, Abcam) were used. For siRNA studies, siRNAS for DNMT(#4390771, Ambion, Austin, TX) and Control (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA) were used.

2.3 |. MTT assay

Uveal melanoma cells were plated in triplicate wells (1 × 103 cells per well) and treated with increasing concentrations of drugs for 72 hr. Cell viability was determined using the MTT assay as described previously (Faiao-Flores et al., 2017).

2.4 |. Colony formation assay

1 × 103 cells were plated and allowed to attach overnight. The medium and drug/vehicle was replaced every two days for 4 weeks. After the specific treatments for each experiment, colonies were stained with crystal violet dye, as previously described (Faiao-Flores et al., 2017).

2.5 |. Cell death assay

Apoptosis was determined as previously described (13). Briefly, cells were treated with drug for 72 hr and incubated with Annexin V APC (BD biosciences, San Jose, CA) in Annexin V binding buffer (BD). Cells were analyzed for Annexin V positivity using a FACSCalibur (BD).

2.6 |. RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq)

RNA was extracted from 92.1 uveal melanoma cells using Qiagen’s Rneasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and screened for quality on an Agilent BioAnalyzer after 48hr treatment with vehicle, decitabine (1 μM), MEKi (10 nM), or combination. A Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p-value of less than 0.05 was used as a cutoff to determine significantly differentially expressed genes. Significantly expressed genes were uploaded into GeneGo (Thomson Reuters, Eagan, MN). Data were analyzed for pathway analysis and significant interactions between uploaded gene IDs. Significant interactions between genes were visualized by Cytoscape using the degree sorted circle algorithm. Significantly changed genes were also uploaded into STRING, with interactions surpassing the most stringent threshold of 0.9 being exported and visualized by Gephi software using the OpenOrD algorithm.

2.7 |. 3D spheroid assays

Uveal melanoma spheroids were prepared and placed in a collagen matrix as previously described (Smalley, Contractor, et al., 2008a; Smalley et al., 2006). The spheroids were treated with drugs for 72 hr, and subsequently stained with Live/Dead viability stain (Thermo Fisher, Carlsbad, CA) to be analyzed using a Nikon-300 inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY). Red puncta, indicating dead cells, were measured for each spheroid.

2.8 |. Animal experiments

All animal experiments were carried out in agreement with ethical regulations and protocols approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Animal Care and by The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC number IS00002983). Eight-week-old female CBySmn.CB17-Prdkc scid/j mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bay Harbor, ME) were subcutaneously injected with 1.0 × 106 MP41 uveal melanoma cells per mouse. The tumors were allowed to engraft for 22 days until palpable, and mice were randomized into 4 groups based on tumor volumes which were on average 50 mm3, with a total of six mice per group. Mice were treated with trametinib (1mg/kg – gavage - daily), decitabine (0.5mg/kg – IP – three times a week) or combination of both agents for 30 days. The control group received both vehicles (Trametinib-0.5% methylcellulose + 0.5% Tween-80 in water; Decitabine-phosphate-buffered saline). Mouse weight and tumor volumes (½ × L × W2) were measured every 72 hr. Tumors were collected at endpoint and analyzed by immunohistochemistry staining as previously described (13). All animal experiments were carried out in agreement with ethical regulations and protocols approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Animal Care and by The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC number IS00002983).

2.9 |. Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of a triplicate of at least three independent experiments. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used followed by a post hoc t test. Significant differences between the control and treated groups are indicated by ***=p < .001, **=p < .01 and *=p < .05. # indicates non-significant (p > .05).

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Although small molecule inhibitors of MEK have been explored in uveal melanoma, levels of progression-free survival are very short and the majority of patients fail therapy. Here, we evaluated a panel of epigenetic inhibitors as a strategy to limit escape from MEKi therapy. It was found that that the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor (DNMTi) decitabine enhanced the efficacy of the MEK inhibitor trametinib in in vitro and in vivo models of uveal melanoma through effects upon the cell cycle and apoptosis. This work provides the preclinical rationale for exploring new combinations of epigenetic and MEK inhibitors in uveal melanoma.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is supported by the Bankhead-Coley Program of the State of Florida 7BC05 (to KSMS, JWH and JDL). It has been also supported in part by the Flow Cytometry Core Facility, the Analytic Microscopy Core Facility, the Proteomics and Metabolomics Core Facility, the Molecular Genomics Core and the Tissue Core Facility at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292). This work has also been supported in part by Bolsista da Capes PDSE - Edital no 19/2016 Processo no 88881.131638/2016–01. Uveal melanoma studies in the Aplin laboratory are funded by a Melanoma Research Alliance team science award and Dr. Ralph and Marian Falk Medical Research Trust Bank of America, N.A., Trustee.

Funding information

Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, Grant/Award Number: P30-CA076292; Bolsista da Capes, Grant/Award Number: 131638/2016–01, PDSE - Edital n° 19/2016 and Processo n° 88881; Florida Department of Health, Grant/Award Number: 7BC05

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

REFERENCES

- Ambrosini G, Khanin R, Carvajal RD, & Schwartz GK (2014). Overexpression of DDX43 mediates MEK inhibitor resistance through RAS Upregulation in uveal melanoma cells. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, 13, 2073–2080. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosini G, Pratilas CA, Qin LX, Tadi M, Surriga O, Carvajal RD, & Schwartz GK (2012). Identification of unique MEK-dependent genes in GNAQ mutant uveal melanoma involved in cell growth, tumor cell invasion, and MEK resistance. Clinical Cancer Research, 18, 3552–3561. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal RD, Piperno-Neumann S, Kapiteijn E, Chapman PB, Frank S, Joshua AM, … Nathan P. (2018). Selumetinib in combination with dacarbazine in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma: A phase III, multicenter, randomized trial (SUMIT). Journal of Clinical Oncology, 36, 1232–1239. 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Quevedo JF, Milhem MM, Joshua AM, Kudchadkar RR, … Schwartz GK (2014). Effect of selumetinib vs chemotherapy on progression-free survival in uveal melanoma: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 311, 2397–2405. 10.1001/jama.2014.6096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wu Q, Depeille P, Chen P, Thornton S, Kalirai H, … Bastian BC (2017). RasGRP3 Mediates MAPK Pathway Activation in GNAQ Mutant Uveal Melanoma. Cancer Cell, 31(685–696), e6. 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Chua V, Liao C, Purwin TJ, Terai M, Kageyama K, … Aplin AE (2017). Co-targeting HGF/cMET signaling with mek inhibitors in metastatic uveal melanoma. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, 16, 516–528. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Terai M, Kageyama K, Ozaki S, Mccue PA, Sato T, & Aplin AE (2015). Paracrine effect of NRG1 and HGF drives resistance to MEK inhibitors in metastatic uveal melanoma. Cancer Research, 75, 2737–2748. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das PM, & Singal R. (2004). DNA methylation and cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22, 4632–4642. 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons MF, Faião-Flores F, Sharma R, Thapa R, Messina JL, Becker JC, … Smalley KSM (2019). HDAC8 regulates a stress response pathway in melanoma to mediate escape from BRAF inhibitor therapy. Cancer Research, 79, 2947–2961. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-0040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faião-Flores F, Alves-Fernandes DK, Pennacchi PC, Sandri S, Vicente ALSA, Scapulatempo-Neto C, … Maria-Engler SS (2017). Targeting the hedgehog transcription factors GLI1 and GLI2 restores sensitivity to vemurafenib-resistant human melanoma cells. Oncogene, 36, 1849 10.1038/onc.2016.348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faiao-Flores F, Emmons MF, Durante MA, Kinose F, Saha B, Fang B, … Rix U. et al. (2019). HDAC inhibition enhances the in vivo efficacy of MEK inhibitor therapy in uveal melanoma. Clinical Cancer Research, 25, 5686–5701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbour JW (2012). Update in uveal melanoma. Clinical Advances in Hematology and Oncology, 10, 459–461. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lübbert M, Suciu S, Baila L, Rüter BH, Platzbecker U, Giagounidis A, … Wijermans PW (2011). Low-dose decitabine versus best supportive care in elderly patients with intermediate- or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) ineligible for intensive chemotherapy: Final results of the randomized phase III study of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Leukemia Group and the German MDS Study Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29, 1987–1996. 10.1200/jc0.2010.30.9245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes K, De Smedt E, Lemaire M, De Raeve H, Menu E, Van Valckenborgh E, … De Bruyne E. (2014). The role of DNA damage and repair in decitabine-mediated apoptosis in multiple myeloma. Oncotarget, 5, 3115–3129. 10.18632/oncotarget.1821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz K, Sattler N, Wagner M, Lubbert M, Dorken B, & Tamm I. (2005). Induction of gene expression by 5-Aza-2’-deoxycytidine in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) but not epithelial cells by DNA-methylation-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Leukemia, 19, 103–111. 10.1038/sj.leu.2403552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y, & Aplin AE (2012). BH3-only protein silencing contributes to acquired resistance to PLX4720 in human melanoma. Cell Death and Differentiation, 19, 2029–2039. 10.1038/cdd.2012.94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SV, Lee DY, Li B, Quinlan MP, Takahashi F, Maheswaran S, … Settleman J. (2010). A chromatin-mediated reversible drug-tolerant state in cancer cell subpopulations. Cell, 141, 69–80. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalley KS, Contractor R, Nguyen TK, Xiao M, Edwards R, Muthusamy V, … Nathanson KL (2008a). Identification of a novel subgroup of melanomas with KIT/cyclin-dependent kinase-4 overexpression. Cancer Research, 68, 5743–5752. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalley KS, Haass NK, Brafford PA, Lioni M, Flaherty KT, & Herlyn M. (2006). Multiple signaling pathways must be targeted to overcome drug resistance in cell lines derived from melanoma metastases. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, 5, 1136–1144. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalley KS, Lioni M, Noma K, Haass NK, & Herlyn M. (2008). In vitro three-dimensional tumor microenvironment models for anticancer drug discovery. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery, 3, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stresemann C, & Lyko F. (2008). Modes of action of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitors azacytidine and decitabine. International Journal of Cancer, 123, 8–13. 10.1002/ijc.23607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Raamsdonk CD, Bezrookove V, Green G, Bauer J, Gaugler L, O’Brien JM, … Bastian BC (2009). Frequent somatic mutations of GNAQ in uveal melanoma and blue naevi. Nature, 457, 599–602. 10.1038/nature07586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F-X, Luo J, Mo J-S, Liu G, Kim YC, Meng Z, … Guan K-L (2014). Mutant Gq/11 promote uveal melanoma tumorigenesis by activating YAP. Cancer Cell, 25, 822–830. 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.