Significance

Deportation has an outsize effect on the lives of Latinos living in the United States. Among Latino noncitizens vulnerable to deportation, their reports of deportation fears have been high and stable since 2007—regardless of the national deportation rate. Among Latino US citizens largely immune to deportation but who fear it for their loved ones or communities, their reports of deportation fears have increased substantially since the 2016 US presidential election. US citizens’ increasing fears reflect not changing deportation rates but a growing national awareness of deportation policy and practice.

Keywords: fear, deportation, citizenship, legal status, Latinos

Abstract

Deportation has become more commonplace in the United States since the mid-2000s. Latin American noncitizens—encompassing undocumented and documented immigrants—are targeted for deportation. Deportation’s threat also reaches naturalized and US-born citizens of Latino descent who are largely immune to deportation but whose loved ones or communities are deportable. Drawing on 6 y of data from the National Survey of Latinos, this article examines whether and how Latinos’ deportation fears vary by citizenship and legal status and over time. Compared with Latino noncitizens, Latino US citizens report lower average deportation fears. However, a more complex story emerges when examining this divide over time: Deportation fears are high but stable among Latino noncitizens, whereas deportation fears have increased substantially among Latino US citizens. These trends reflect a growing national awareness of—rather than observable changes to—deportation policy and practice since the 2016 US presidential election. The article highlights how deportation or its consequences affects a racial group that the US immigration regime targets disproportionately.

Between 2007 and 2018, the United States carried out 4 million deportations—two-thirds of all deportations since 1990 (1). All noncitizens—encompassing the undocumented, temporary visa holders, and lawful permanent residents (“green card holders”)—are legally vulnerable to deportation (2–5). As policy changes since the mid-1980s have integrated tools from criminal law enforcement into immigration law enforcement (6), deportation’s reach has expanded from the border to millions of noncitizens living inside the country (7, 8). Latin American noncitizens, in particular, experience deportation at rates higher than their share of the noncitizen population subject to deportation (9). This disproportionality reflects longstanding, bipartisan efforts to construct Latin American immigration as a societal threat (10). Deportation subjects noncitizens to unsafe detention facilities (11), upends their livelihoods (12), and negatively impacts their behavioral, mental, and physical health outcomes (13, 14). These economic and health consequences manifest even absent a noncitizen’s direct experience with deportation (15).

US citizens—encompassing naturalized immigrants as well as born Americans—are all but immune to deportation.† Deportation’s threat reaches them via their loved ones and communities who are deportable. In total, 26.6 million Latino US citizen adults live with 4.8 million noncitizens; 17.3 million Latino US citizen children live with 7.7 million noncitizens.‡ Ethnographies of these mixed-citizenship families reveal that US citizens internalize fears their family members may be deported (16, 17). Even in households where all Latino members are US citizens, worries of being misrecognized as deportable in a US immigration regime racialized in its enforcement may contribute to deportation fears (13, 18, 19). High-profile news reports of Latino US citizens temporarily detained or investigated for their suspected deportability further validate these fears (20). Together, ethnographic research and journalistic accounts suggest that deportation fears may manifest among US citizens worried about their loved ones’ or communities’ deportability.

Despite accumulating evidence of deportation fears among Latino US citizens and noncitizens, we know surprisingly little about whether and how these fears manifest nationally and over time. Research using population-representative administrative or survey data has linked changes to deportation policy or practice with negative consequences for Latino US citizens’ and noncitizens’ behavioral (21–27), mental (28–32), and physical (33–35) health. In each study, a structural factor—for example, the national deportation rate—is linked to an outcome of interest—such as increased rates of psychological distress—and deportation fear is assumed to underlie any observed association. Few measure fear directly, and most assume fear to be increasing alongside the deportation rate. However, since at least 2007, national deportation rates have remained elevated under the successive presidential administrations of George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump (1). Latinos’ perceptions of deportation threat associated with each administration may have nonetheless shifted. This article measures fear through forward-looking questions about deportation’s possibility to examine whether and how Latino US citizens and noncitizens fear deportation in their daily lives, and if these fears have changed over time.

Research Strategy and Key Findings

This article relies on 6 y of population-representative data from the National Survey of Latinos conducted by the Pew Hispanic Center (hereafter, Pew). Although the survey is cross-sectional, Pew regularly polls adults age 18 and older of Latino descent in the United States to elicit their opinions on economics, politics, and society. In 2007, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2016, and 2018, Pew inquired as to respondents’ fears that they or a loved one could be deported. These surveys form the basis of this analysis. The results show that Latinos’ fears are mostly stable between 2007 and 2018; that only US citizens’ fears are increasing across time; that, among noncitizens, lawful permanent residents and likely undocumented immigrants harbor high but stable fears; and that these trends do not reflect changing deportation rates but rather a growing national awareness of deportation policy and practice since the 2016 US presidential election.

The dependent variable is self-reported deportation fears. Respondents were asked in each year, “Regardless of your own immigration or citizenship status, how much, if at all, do you worry that you, a family member, or a close friend could be deported?” This single indicator captures personal and vicarious fears of deportation, which qualitative research views as intertwined in Latino families and communities whose members hold diverse citizenship or legal statuses: Even when someone’s own social location immunizes them from deportation (e.g., US citizens), they may still report deportation fears emanating from their loved ones’ vulnerable social locations—or from being temporarily detained for their suspected “deportability” in a US immigration regime racialized in its enforcement (13, 17, 18, 36, 37). To produce reliable estimates, respondents answering “not much” or “not at all” are coded as “0,” and those answering “some” or “a lot” as “1.” SI Appendix, Fig. S2 shows similar results when deportation fears are measured as a scale.

The primary independent variable is respondents’ citizenship and legal status. Those born in the United States or a US territory, and those born abroad to a US-citizen parent, are US-born citizens. Naturalized citizens are born abroad to foreign-born parents and report holding US citizenship. Lawful permanent residents have a foreign birthplace and say they hold or have been approved for a green card. The final category is a residual grouping of respondents I term “likely undocumented.” Although this group may include some documented immigrants, like student- or work-visa holders, as well as beneficiaries of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) or Temporary Protected Status, these provisional permits entail a precariousness most similar to an undocumented status (38).§ This precariousness emerges from policy changes since the 1980s that have made it easier to fall out of a legal status—through requirements for more frequent visa renewals, expensive legal fees, and confusing rules governing specific visas—than to fall into one (2, 5, 39–41). The primary analysis distinguishes between all US citizens and all noncitizens, but I also present results that delineate among US-born citizens, naturalized citizens, lawful permanent residents, and likely undocumented immigrants.

I use multiple imputation through chained equations to impute missing values in the pooled Pew data. The primary analysis estimates a logistic regression model to compare the odds that US citizens report deportation fears relative to noncitizens. To evaluate any changes in reported deportation fears by citizenship across time, I add an interaction term between citizenship and survey year. I calculate differences in average marginal effects to facilitate interpretation of the interaction term (42). I describe the data and methods—including alternative specifications, assumptions, and limitations—in Materials and Methods.

Data Availability

A replication package containing all data and code used in this analysis is available through the Harvard Dataverse (43).

Results

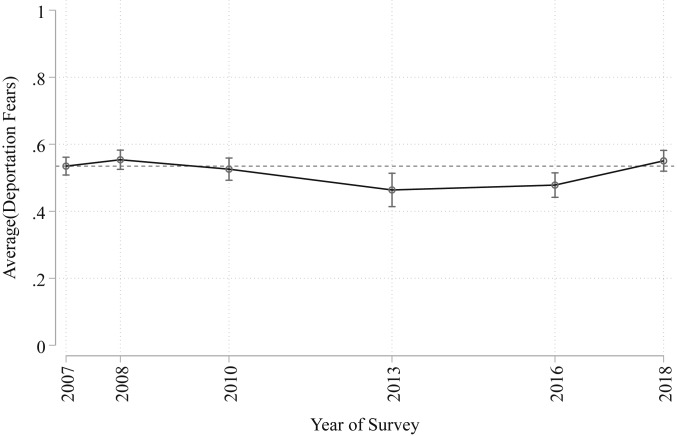

Fig. 1 displays Latinos’ reported deportation fears using the Pew data between 2007 and 2018. Overall, 51.8% [50.3%, 53.2%] (95% confidence interval) of Latinos reported deportation fears within the survey period. Fears are generally stable across time. In total, 53.5% [50.8%, 56.1%] of Latinos reported deportation fears in 2007; 55.0% [51.9%, 58.2%] did in 2018.

Fig. 1.

Proportion of Latinos reporting deportation fears, 2007 to 2018. Notes: The dashed horizontal line represents the sample average in 2007 (53.5%). The vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals based on linearized SEs. Deportation fears question asks: “Regardless of your own immigration or citizenship status, how much, if at all, do you worry that you, a family member, or a close friend could be deported? Would you say that you worry a lot, some, not much, or not at all?” Respondents answering “a lot” and “some” are combined into a single category; those answering “not much” and “not at all” are also combined. Source: Author’s tabulation of 2007, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2016, and 2018 National Survey of Latinos from Pew Hispanic Center.

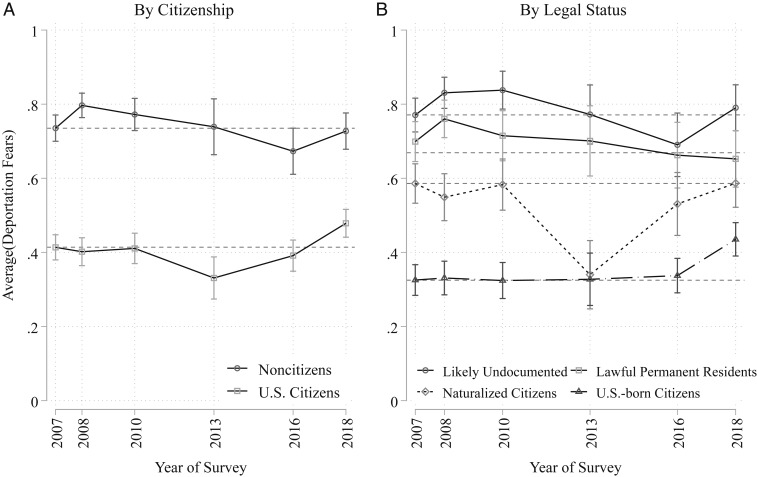

Fig. 2 presents Latinos’ reported deportation fears across time by (Fig. 2A) citizenship and (Fig. 2B) legal status. The highest average fears are among noncitizens, a diverse group that shares a legal vulnerability to deportation. However, noncitizens’ fears are stable. In total, 73.5% [70.0%, 77.1%] of Latino noncitizens reported deportation fears in 2007. Their fears climax in 2008 (79.7% [76.4%, 83.0%]) but return to their 2007 level thereafter. This pattern is similar among lawful permanent residents and likely undocumented immigrants. Among Latino US citizens, a diverse group that is largely immune to deportation but likely worried about their loved ones and communities, 41.4% [38.0%, 44.8%] report fears in 2007. By 2013, 33.1% [27.4%, 38.8%] of Latino US citizens fear deportation. Changes to naturalized citizens’ average fears drive this reduction for reasons considered below and in the conclusion. Fears nonetheless increase among both naturalized citizens (contrast: 0.25 [0.13, 0.36]) and US-born citizens (contrast: 0.11 [0.02, 0.19]) between 2013 and 2018. In 2018, 47.9% [44.1%, 51.6%] of all Latino US citizens report deportation fears. These trends suggest that, while noncitizens have exhibited stable fears, US citizens’ fears have increased.¶

Fig. 2.

Proportion of Latinos reporting deportation fears by citizenship and legal status, 2007 to 2018. Notes: The dashed horizontal lines in A represent the average for noncitizens (73.5%) and US citizens (41.4%) in 2007. The dashed horizontal lines in B represent the average for likely undocumented immigrants (77.1%), lawful permanent residents (66.9%), naturalized citizens (58.6%), and US-born citizens (32.5%) in 2007. Missing data are imputed using chained equations. The vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals based on linearized SEs. Deportation fears question asks: “Regardless of your own immigration or citizenship status, how much, if at all, do you worry that you, a family member, or a close friend could be deported? Would you say that you worry a lot, some, not much, or not at all?” Respondents answering “a lot” and “some” are combined into a single category; those answering “not much” and “not at all” are also combined. Source: Author’s tabulation of 2007, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2016, and 2018 National Survey of Latinos from Pew Hispanic Center.

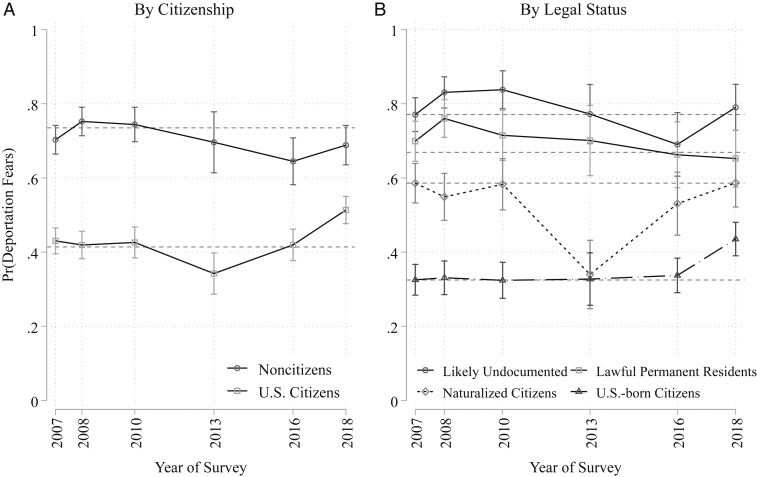

Fig. 3 presents adjusted predicted probabilities of reporting deportation fears by (Fig. 3A) citizenship and (Fig. 3B) legal status. In all cases, the predicted probabilities are similar to the proportions observed in Fig. 2, an indication that citizenship and legal status are meaningful dimensions patterning Latinos’ fears. Noncitizens have the highest predicted probabilities of reporting fears, and US citizens have the lowest. Among noncitizens, the predicted probability is 0.70 [0.66, 0.74] in 2007 and statistically similar through 2018. This pattern is similar when considering lawful permanent residents and likely undocumented immigrants separately. Lawful permanent residents evince stable predicted probabilities of reporting deportation fears in 2007 (0.68 [0.62, 0.73]) and through 2018 (0.63 [0.55, 0.71]). Likely undocumented immigrants’ predicted probabilities are also similar in 2007 (0.72 [0.67, 0.78]) and through 2018 (0.75 [0.68, 0.82]).

Fig. 3.

Adjusted predicted probabilities of Latinos reporting deportation fears by citizenship and legal status, 2007 to 2018. Notes: The dashed horizontal lines in A represent the average for noncitizens (73.5%) and US citizens (41.4%) in 2007. The dashed horizontal lines in B represent the average for likely undocumented immigrants (77.1%), lawful permanent residents (66.9%), naturalized citizens (58.6%), and US-born citizens (32.5%) in 2007. The vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals based on linearized SEs. Missing data are imputed using chained equations. Deportation fears question asks: “Regardless of your own immigration or citizenship status, how much, if at all, do you worry that you, a family member, or a close friend could be deported? Would you say that you worry a lot, some, not much, or not at all?” Respondents answering “a lot” and “some” are combined into a single category; those answering “not much” and “not at all” are also combined. Controls include: age, sex, educational attainment, political party, the number of adults in a respondent’s household, the geographic region in which the respondent completed the survey, the survey year, and an interaction term between citizenship and survey year. Source: Author’s analysis of 2007, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2016, and 2018 National Survey of Latinos from Pew Hispanic Center.

Among US citizens, the predicted probability of reporting fears fluctuates. It starts at 0.43 [0.40, 0.47] in 2007, falls to 0.34 [0.29, 0.40] in 2013, and increases in 2016 relative to 2013 (contrast: 0.08 [0.01, 0.14]) and 2018 relative to 2016 (contrast: 0.09 [0.04, 0.15]). US citizens in 2018 have a predicted probability of fearing deportation of 0.51 [0.48, 0.55]. Between 2013 and 2018, US citizens’ predicted probability of fearing deportation increases by 50%. This pattern varies by naturalized and US-born citizens. Naturalized citizens’ predicted probability of fearing deportation in 2007 is 0.60 [0.55, 0.65], falls to 0.36 [0.26, 0.44] in 2013, and boomerangs to its 2007 level in 2016 (0.57 [0.49, 0.65]) and 2018 (0.61 [0.55, 0.68]). US-born citizens’ predicted probability of fearing deportation in 2007 is 0.33 [0.29, 0.37] and similar through 2016; by 2018, however, it increases to 0.47 [0.42, 0.51]. The difference in US-born citizens’ predicted probabilities between 2018 and 2013 (contrast: 0.13 [0.05, 0.21]) represents a 42% increase. A longer time series is needed to assess whether this increase among US-born citizens reflects an ongoing trend. The data overall nonetheless point to growing deportation fears among Latino US citizens as a group.

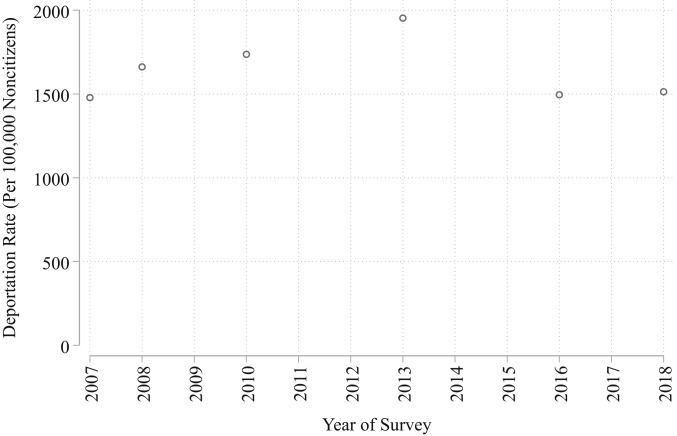

What might account for US citizens’ increasing fears? Changes to deportation policy and practice across the study period is one potential culprit. Fig. 4 charts national deportation rates (per 100,000 noncitizens) in each of the survey years in the primary analysis. Deportation rates climb under the Bush administration in 2007 (1,478.2) and 2008 (1,661.8). They climax under the Obama administration in 2010 (1,736.8) and 2013 (1,952.9) before falling in 2016 (1,495.5). The deportation rate (1,513.2) under the Trump administration in 2018 is among the lowest in the series. If trends in deportation rates predict trends in deportation. fears, then the predicted probabilities in Fig. 3 should similarly wax and wane for Latino US citizens and noncitizens.They do not, suggesting that changes to deportation policy and practice likely do not account for the observed trends.

Fig. 4.

National deportation rate (per 100,000 noncitizens), 2007 to 2018. Source: Number of deportations is from the Department of Homeland Security’s Yearbook of Immigration Statistics data (table 39) for fiscal years 2007, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2016, and 2018. Estimates of the number of noncitizens at risk for deportation are from the 2007 (3-y estimates), 2008 (3-y estimates), 2010 (5-y estimates), 2013 (5-y estimates), 2016 (5-y estimates), and 2018 (5-y estimates) American Community Survey.

Evidence in the Pew data further supports the idea that deportation policy and practice are disconnected from Latino US citizens’ heightened fears. First, changing deportation rates may underlie trends in fears through one’s proximity to people who have been deported. If so, there should be observable changes across time in whether Latino US citizens know someone who has been detained or deported. These data are available only in 2010 among the surveys used in the primary analysis, and in additional Pew surveys in 2011, 2012, and 2014.# SI Appendix, Fig. S3 shows Latino US citizens—naturalized or born—are as likely across time to know someone who has been deported when deportation rates under the Obama administration are at their height.

Second, deportation policy and practice target Latin American noncitizens. This targeting may temporarily burden Latino US citizens in a US immigration regime where to be “deportable” so often means to be Latino (but not always vice versa) (18, 44). Changes in deportation fears may therefore reflect Latinos’ changing perceptions of racial/ethnic discrimination. These data are available for 2007, 2008, 2010, and 2018 and reported in SI Appendix, Fig. S4 by 1) citizenship and 2) legal status. Results are similar when controlling for reports of racial/ethnic discrimination.

Third, deportation specifically targets immigrants from Mexico and Central America. If deportation policy and practice explain the observed trends in fear, then heightened fears may result from the changing composition of the Latino population descended from Mexico or Central America. Data on national heritage are available for 2007, 2008, 2010, and 2018. Results in SI Appendix, Fig. S5 are similar by 1) citizenship and 2) legal status when controlling for national heritage.

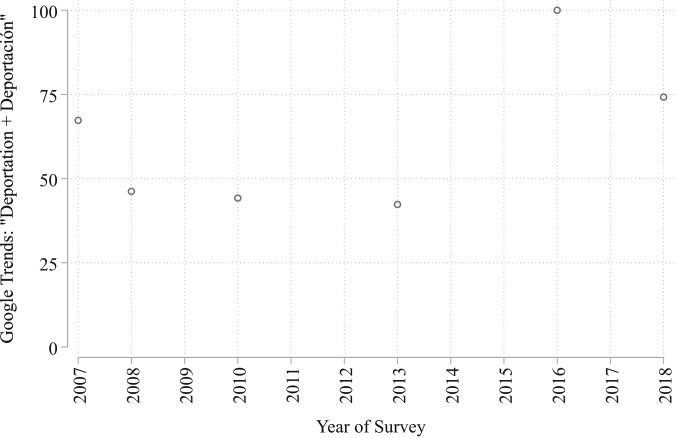

Changes in Latino US citizens’ deportation fears may therefore more closely reflect a growing national salience of—rather than observable changes to—deportation policy and practice (10, 35, 45). Fig. 5 uses Google Trends data to measure the US public’s online searches for “deportation” (in English and Spanish) across the study period (46). This measure, normalized to range from 0 (lowest) to 100 (highest), evaluates deportation’s relative salience to the US public in the months surrounding data collection for each survey.‖ It is an elevated 67.3 under the Bush administration during the months of the 2007 survey, which followed two failed congressional attempts at comprehensive immigration reform that would have granted undocumented immigrants a pathway to US citizenship (47). Although the Bush administration does not change deportation policy or practice between 2007 and 2008 (48), the Google Trends measure falls to 46.2 during the months of the 2008 survey. Deportation rates continue to climb under the Obama administration, but the Google Trends measure is a similar 44.2 at the time of the 2010 survey. At the height of the national deportation rate in 2013, and following the implementation of the DACA program and Barack Obama’s reelection (49), the Google Trends measure falls slightly to 42.3.** The measure climaxes at 100 in 2016 following the US presidential election but prior to Donald Trump’s inauguration, which corresponds to well-documented uncertainty surrounding deportation policy and practice at the time (50, 51). The measure remains elevated at 74.2 in 2018. Changes in Latino US citizens’ deportation fears track these changes in deportation’s salience to the US public.

Fig. 5.

Google Trends measure of searches for “deportation” and “deportación,” 2007 to 2018. Source: Google Trends. The search period is defined from January 1, 2007 through December 31, 2018. Trends are normalized by coding the highest frequency as 100. The search terms are “Deportation” + “Deportación” (in Spanish). For each year, the Google Trends measure represents the averages of the month–year scores in months spanning each Pew survey (i.e., October to November 2007, June to July 2008, August to September 2010, October to November 2013, December 2016 to January 2017, and July to September 2018).

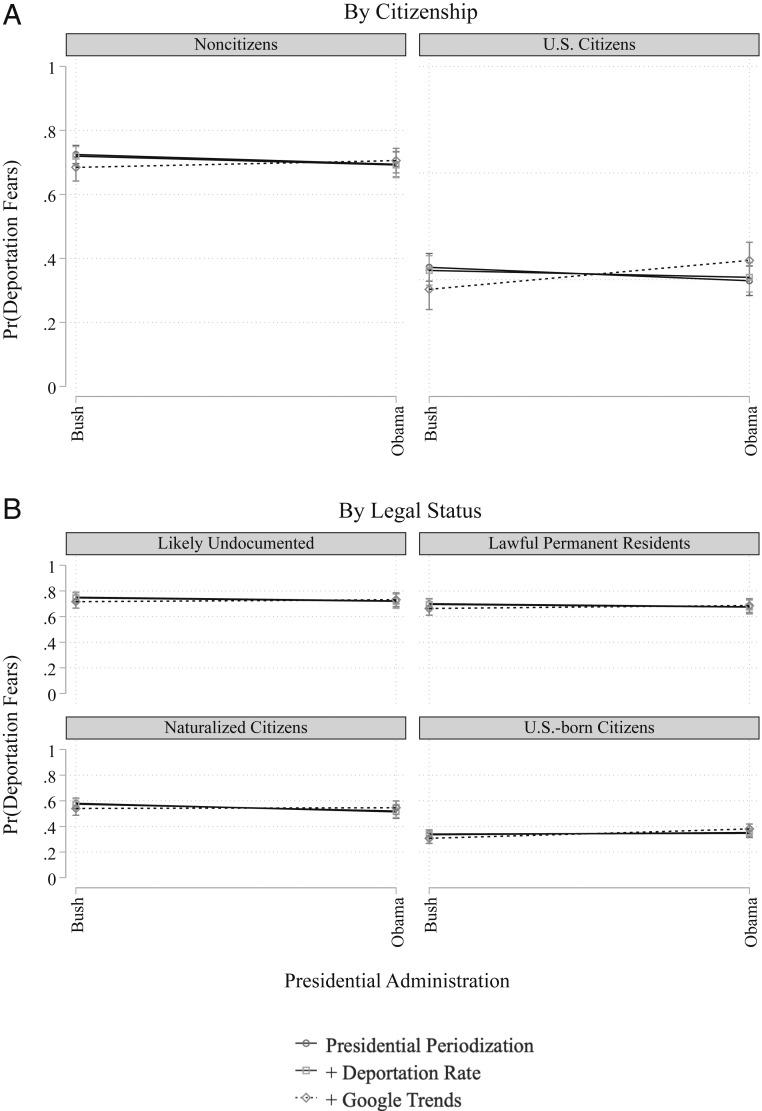

The preceding analysis offers suggestive evidence that a growing national awareness of deportation policy and practice across time—particularly in the time since the 2016 US presidential election—underlies the observed trends in fear. To more systematically assess this claim, Fig. 6 replaces the survey year indicator with an indicator for the Bush (2007 and 2008) and Obama (2010, 2013, and 2016) administrations.†† It shows trends in deportation fears by (Fig. 6A) citizenship and (Fig. 6B) legal status when the main analysis is presented by presidential administration, when the deportation rate control is added, and when the Google Trends measure is added. In the fully adjusted model, US citizens’ deportation fears under the Obama and Bush administrations are similar (contrast: 0.03 [−0.02, 0.09]). However, when decomposed by legal status, only US-born citizens have a higher predicted probability of reporting fear under the Obama relative to the Bush administration (contrast: 0.07 [0.01, 0.14]). The Google Trends measure in 2016, which is at its maximum following the presidential election, underlies this result. Divergent patterns among naturalized citizens and US-born citizens under the Bush and Obama administrations may reflect these groups’ differential social proximity to noncitizens who are deportable. More than one-fourth of all Latino naturalized citizen adults have at least one noncitizen family member; about one-seventh of all Latino US-born citizen adults have the same.‡‡ The naturalized may have been especially attentive to changes in the real or perceived context of deportability across time given their greater social proximity to noncitizens; for the US-born, deportation threat may have become more palpable following the election of a candidate whose rhetoric explicitly and consistently threatened their families (50, 52).

Fig. 6.

Adjusted predicted probabilities of Latinos reporting deportation fears by (A) citizenship and (B) legal status, 2007 to 2018. Notes: Bush administration includes 2007 and 2008 survey. Obama administration includes 2010, 2013, and 2016 survey. Trump administration excluded due to limited time series. The vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals based on linearized SEs. Missing data are imputed using chained equations. Deportation fears question asks: “Regardless of your own immigration or citizenship status, how much, if at all, do you worry that you, a family member, or a close friend could be deported? Would you say that you worry a lot, some, not much, or not at all?” Respondents answering “a lot” and “some” are combined into a single category; those answering “not much” and “not at all” are also combined. Controls include: age, sex, educational attainment, political party, the number of adults in a respondent’s household, the geographic region in which the respondent completed the survey, the presidential administration, and an interaction term between legal status and the presidential administration. Source: Author’s analysis of 2007, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2016, and 2018 National Survey of Latinos from Pew Hispanic Center.

Discussion

This article examines Latinos’ reported deportation fears between 2007 and 2018 using 6 y of population-representative survey data. As a group, Latinos’ fears are stable across time. However, comparing Latino US citizens and noncitizens reveals a more complex narrative. Noncitizens, encompassing undocumented and documented immigrants, are deportable but report static fears. Among US citizens, encompassing naturalized and US-born citizens largely immune to deportation, fears have increased. Changing deportation rates do not account for these trends for either group, which more closely reflect a growing national awareness of deportation policy and practice—particularly since the 2016 US presidential election. These results uncover stability in Latino noncitizens’ fears and highlight growing fears among Latino US citizens worried about a US immigration regime they perceive as hostile toward their loved ones or communities.

Additional work is needed to extend the analyses presented here. First, survey questions that allow researchers to disentangle one’s personal fear of deportation from vicarious fears of a family member’s or close friend’s deportation would be invaluable. Second, complete household rosters—including the age, relationship, and citizenship status of household members—are needed to assess whether the observed trends vary by single- and mixed-citizenship households and/or households with and without young children. Third, the nationally representative, cross-sectional survey data on which this article is based help illuminate important nuances in Latinos’ deportation fears. However, longitudinal and survey experimental data are needed to identify causal relationships between citizenship and legal status and deportation fears. Fourth, features of the US immigration regime vary across state and local contexts. Although changes to the national deportation rate do not account for the observed trends in deportation fears, large-scale survey data that allow researchers to link subnational place characteristics to deportation fears would help to account for more localized experiences of the US immigration regime. If these data also captured respondents from different racial/ethnic groups, then future analyses might scrutinize whether far-reaching deportation fears are a phenomenon unique to Latinos. Finally, future efforts to collect survey data might consider including an attribution scale measuring respondents’ perception of stigma on the basis of perceived legal status. These data would permit analysis of the specific source of discrimination underlying deportation fears.

Results from this study nonetheless contribute to research on the US immigration regime. Ethnographic studies in individual locales suggest noncitizenship—rather than undocumented status per se—is an axis along which deportability manifests (2, 53). This article supports this idea with nationally representative survey data. However, the results also offer an important qualification insofar as noncitizens’ fears are generally similar across time—regardless of the national deportation rate. This stability makes statistical and practical sense in light of expansions to the US immigration regime in the mid-1980s and 1990s, which expanded noncitizens’ deportability through massive investments in Mexico–United States border security, the related settlement of larger numbers of undocumented immigrants from Latin America in the United States who could no longer return home regularly, the creation of increasingly temporary legal statuses with no pathway to US citizenship, and a widened deportation dragnet (2, 4, 54). Democratic and Republican presidential administrations’ efforts to govern the US immigration regime may differ in their tenor but are similar in their enforcement tactics. Noncitizens are aware of this reality (55) and report stable deportation fears across time.

However, this article has unearthed growing fears among US citizens. Multiple mechanisms may underlie this result (19). Among Latino naturalized citizen adults, who experienced a sharp decline in fears in 2013, their greater social proximity to noncitizens vulnerable to deportation may matter. The Obama administration has outsize deportation rates, but it is also credited for moving away in its second term from detaining or deporting immigrants who have settled in the country long-term (56). Latino naturalized citizens may have read this shift optimistically for their loved ones and communities. Uncertainty since the 2016 presidential election with respect to deportation policy and practice, including rare but nascent efforts at denaturalization, may have reversed this optimism (57–59). Among Latino US-born citizen adults, who are about half as likely as their naturalized counterparts to live in households with noncitizens, a growing national salience of deportation policy and practice under a vocally hostile presidential administration may matter (16). Their privileged birthright citizenship may have buffered against deportation fears prior to the 2016 presidential election, but virulent rhetoric targeting Latinos—regardless of citizenship or legal status—may underlie their heightened fears (13). Among all Latino US citizens, fears may magnify under a racialized US immigration regime when their loved ones or communities, as well as anyone who “looks ‘deportable,’” may be investigated or detained for their suspected deportability (13, 18).

Whatever the precise mechanism underlying the results, the study points to the consequences of deportability on a racial group the US immigration regime targets disproportionately. Focusing on the situation of Latinos in the United States, the analysis reveals how deportation fears reach beyond noncitizens to ensnare US citizens worried about their loved ones and communities. More broadly, the article underscores how laws apparently intended to regulate a single social group—here, noncitizens—can have collateral consequences for the lives of individuals outside the target population. Future research attuned to the long arm of other ostensibly race-neutral laws that are racially unequal in their enforcement may well uncover similar dynamics.

Materials and Methods

This article relies on 6 y of data from the National Survey of Latinos conducted by the Pew Hispanic Center (hereafter, Pew). Although the survey is cross-sectional, Pew regularly polls adults age 18 and older of Latino descent in the United States to elicit their opinions on economics, politics, and society. In October to November 2007, June to July 2008, August to September 2010, October to November 2013, December 2016 to January 2017, and July to September 2018, Pew inquired as to respondents’ deportation fears. These surveys form the basis of this analysis.

Full documentation regarding sampling methodology for each survey year is available from Pew online, but sampling is consistent across time. Survey research firms working on behalf of Pew used random-digit dialing of landlines and mobile phones to contact households. Telephone numbers were stratified by whether they matched surnames listed in several databases known to be associated with Latino heritage. An optimal allocation scheme was then used to determine the minimum sample size across each stratum required to yield a precise estimate of the Latino-descended population. Sample weights and poststratification weights using demographic data from the American Community Survey or Current Population Survey (CPS) that also include nativity, year of US entry, and Latino heritage ensure each cross-sectional sample reflects the profile of Latinos surveyed that year (Dataset S1). The CPS undercounts noncitizens, although sampling weights correct some of this undercount in the CPS data. Pew survey weights, however, do not account for unit nonresponse in the Pew survey. It is conceivable that Latino respondents across citizenship categories who are most fearful of deportation did not respond to the Pew survey. If so, this article would underestimate the prevalence of deportation fears.

Participants across survey years were interviewed using computer-assisted telephone interviewing and had the option of completing the survey in either English or Spanish. Question order was randomized to minimize bias stemming from spillover effects within and across years. The 2007 survey included 2,000 respondents, and questions focused on politics, immigration enforcement and reform, and perceptions of discrimination. In 2008, the survey included 2,015 respondents who were polled about the 2008 US presidential election as well as attitudes regarding criminal justice and immigration enforcement. The 2010 survey polled 1,375 respondents about politics, immigration enforcement, and technology. In 2013, the survey included 701 respondents who were asked about politics and immigration enforcement and reform. In late 2016 and early 2017, following the 2016 US presidential election but prior to Donald Trump’s inauguration, 1,001 respondents were asked about the 2016 US presidential election and about immigration enforcement and reform. Finally, the 2018 survey reached 1,501 respondents and recorded opinions regarding the Trump administration and immigration policy.

This article examines differences in deportation fears among Latinos in the United States by citizenship and legal status across time. The time period this article covers, 2007 to 2018, includes the presidential administrations of George W. Bush (2007 and 2008), Barack Obama (2010, 2013, and 2016), and Donald Trump (2018). This era represents the height of contemporary efforts to detain and deport largely Latin American immigrants under three successive administrations. Because the Pew surveys were fielded during defined periods in each year—2007 (October 3 to November 9), 2008 (June 9 to July 13), 2010 (August 17 to September 19), 2013 (October 16 to November 3), 2016 (December 7, 2016, to January 15, 2017), and 2018 (July 26 to September 9)—results within survey years may be reasonably interpreted as snapshots of Latinos’ deportation fears at specific points during these three presidential administrations. Caution should nonetheless be exercised in identifying the specific trigger(s) underlying Latinos’ reported fears within each survey.

Key Variables.

The dependent variable is a self-reported measure of deportation fears. Respondents were asked, “Regardless of your own immigration or citizenship status, how much, if at all, do you worry that you, a family member, or a close friend could be deported?” Possible answers included “a lot,” “some,” “not much,” or “not at all.” To produce reliable estimates, the primary analysis codes respondents who answered “not much” or “not at all” as “0,” and those who answered “some” or “a lot” as “1.” Results are similar when the dependent variable is coded from “0” (not at all”) to “3” (“a lot”) and considered in an ordered logistic regression model (SI Appendix, Fig. S2, 1). Missingness in deportation fears (n = 102) does not vary by citizenship status.

The primary independent variable is respondents’ citizenship status. Pew does not ask its respondents’ citizenship in a single question. It first inquires as to respondents’ birthplace. Respondents born in the United States, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or another US territory, as well as those born abroad to a US-citizen parent, are coded as US-born citizens. Naturalized citizens are those who indicate they are foreign born to foreign-born parents and who report holding US citizenship. Lawful permanent residents are respondents who report a foreign birthplace and who say they have a green card or have been approved for one. A final category is a residual grouping of respondents who are not US-born or naturalized citizens or lawful permanent residents. I term this grouping “likely undocumented.” Although this group may include small numbers of documented immigrants, such as student- or work-visa holders, as well as beneficiaries of DACA or Temporary Protected Status, these provisional permits entail a precariousness most similar to an undocumented status (2, 5, 39, 40). The primary analysis distinguishes between US citizens and noncitizens. The 2013 data do not distinguish between lawful permanent residents and likely undocumented immigrants, but results are similar when finer-grained legal status categories are considered using the multiply imputed data. Missingness in citizenship status (n = 37) does not vary by reported deportation fears.

Control Variables.

The main analysis includes a set of controls available across survey years in the Pew data: age (continuous), sex (reference: male), educational attainment (high school, some college, or college or more; reference: less than high school), political party (Democrat, Independent; reference: Republican), the number of adults in a respondent’s household (continuous), the geographic region in which the respondent completed the survey (North Central, South, West; reference: Northeast), and survey year (reference: 2007). Dataset S2 provides additional details regarding all control variables included in the main analysis.

The Pew data are valuable in that they allow consideration of how citizenship status relates to deportation fears. However, they have their limitations. One is that possible control variables associated with both the key dependent and independent variables are not always available across survey years, raising concerns about potential omitted variable bias stemming from observable confounders. In addition, if control variables are available across surveys, they may not measure the same concept (e.g., self-reported income is observed in 1 y and self-reported financial stability is observed in another). However, supplementary analyses presented in SI Appendix support the main findings presented here. Dataset S2 lists the controls unique to particular survey years. To partly grapple with any potential omitted variable bias, in SI Appendix, Fig. S1, 1, I estimate deportation fears in each survey year using the full set of theoretically relevant controls available in each survey year. These supplementary results allow for comparisons by citizenship status within survey years but cannot be used to draw conclusions between survey years; results are substantively similar to the main analysis.

Any changes in reported fears across the study period may reflect Latinos’ changing perceptions of racial/ethnic discrimination under a racialized US immigration regime. Data on perceptions of racial/ethnic discrimination are available in 2007, 2008, 2010, and 2018. In 2007 and 2010, respondents were asked “During the last five years, have you, a family member, or close friend experienced discrimination because of your racial or ethnic background, or not?” In 2008, respondents were asked, “Have any of these things happened to you in the last year, or not? (a) been stopped by police or other authorities and asked about your immigration status, (b) had trouble getting or keeping a job because you are Latino, or (c) had trouble finding or keeping housing because you are Latino.” In 2018, respondents were asked “During the last twelve months, have you personally experienced racial/ethnic discrimination?” Respondents answering “yes” to any of these questions are coded as having perceived racial/ethnic discrimination under the assumption that those inclined to report discrimination will do so regardless of the specified time horizon. About 31% of respondents in the available years report discrimination.

Deportation specifically targets immigrants from Mexico and Central America. Any changes in reported fears across the study period may therefore reflect changes in the composition of Latino US citizens and noncitizens descended from Mexico or Central America. Data on national heritage are available in 2007, 2008, 2010, 2013, and 2018. I categorize respondents who report Mexican or Central American heritage into a single “Mexican and Central American” category, and all other respondents into an “Other” category. About 71% of respondents surveyed in the available years report Mexican or Central American heritage.

Pew data are available at the national level, and information on when Latino respondents completed each survey is available at the year level. Accordingly, the survey year indicators included in the primary analysis capture year-to-year changes in the “real” and “perceived” context of deportation threat across the surveys. Another way to capture time in the analysis is by replacing the survey year indicators with the presidential administration periodization (i.e., Bush, Obama, and Trump) outlined above. This periodization offers analytical leverage on the question of whether changes to the “real” or “perceived” context of deportation threat account for changes to Latinos’ deportation fears—at least under the Bush and Obama administrations. Since the 2018 data alone capture the Trump administration, the analysis cannot disentangle whether the “real” or “perceived” context of deportation threat under this administration explains Latinos’ observed fears. However, as outlined in the main text, Latinos’ fears are likely driven less by the reality of deportation policy and practice than by a growing national awareness of the same.

The “real” context of deportation threat is measured using data from the Department of Homeland Security on the share of all removals from the United States over the total noncitizen-immigrant population at risk for deportation in each year, which is taken from the American Community Survey (3-y estimates for 2007 and 2008; 5-y estimate for all others). Results are similar using an alternative measure based on data from Immigration and Customs Enforcement on the share of removals from the US interior over the total noncitizen-immigrant population at risk for deportation in each year (60, 61); that is, all deportations occurring outside the United States’ 100-mile border zone in which Customs and Border Protection primarily operates.

The “perceived” context of deportation threat is measured using Google Trends data, which provide aggregate information on the general public’s Google search behavior. Research shows that the Google Trends data reliably capture the US public’s awareness of important social problems such as immigration and immigration enforcement (46). I define the search period from January 1, 2007 through December 31, 2018 to capture the long-term relative salience of deportation in the US public’s Google search behavior throughout the study period. The search terms I include are “Deportation” + “Deportación” (in Spanish), as Pew allows respondents to complete surveys in either language. The measure averages the Google Trends scores in months spanning each Pew survey. For example, the 2007 survey was fielded in October and November 2007; I take the average of the Google Trends score for October and November 2007. Trends are normalized by coding the highest frequency as 100. An alternative measure of the context of “perceived” deportation threat, which averages the number of news articles from four national newspapers mentioning “deport*” in the months spanning each Pew survey and normalizes these counts by coding the highest as 100, bears similar results. The newspapers are The New York Times, The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and The Wall Street Journal, as captured by the Nexis Uni. database.

Analytic Strategy.

This article examines the association of citizenship and legal status with Latinos’ fears of deportation in the United States. I use Stata 16 to estimate logistic regression models predicting the odds of reporting deportation worries by citizenship status. The primary analysis compares US citizens with noncitizens. All estimates incorporate survey weights calculated by Pew but rescaled so that they sum to the same value.

I pool Pew’s National Survey of Latinos for 2007, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2016, and 2018. The proportion of missing data across the control variables used in the main analysis ranges from a low of 0.00% to a high of 15.68% (Dataset S3). Missing data were multiply imputed across 10 datasets using chained equations with the mi impute chained command. To avoid model misspecification, the dependent and independent variables of interest were included in the imputation model, but imputed values of these variables were not used in the primary analyses (53). The imputation model included all variables used in the primary analysis, as well as one auxiliary variable (voter registration status) available in all survey years. The proper model specification for each variable type was used to impute missing data. To avoid perfect prediction, the augment command was used (53). Dataset S4 presents descriptive statistics for the analytic sample by reported deportation fears. Dataset S5 compares odds ratios from logistic regression models using listwise deletion and the imputed data for the main analysis, and Dataset S6 does the same for the analysis involving the finer-grained legal status categories. Estimates from the imputed data are similar to those obtained using listwise deletion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Ana Gonzalez from the Pew Research Center facilitated access to these data, which come from the 2007, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2016, and 2018 National Survey of Latinos. The opinions expressed herein, including any implications for policy, are those of the author and not the Pew Research Center. Andrew Mercer from Pew and Stephen Parry from the Cornell Statistical Consulting Unit offered support with the analyses. Justin Scoggins and Carolina Otero from the University of Southern California Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration provided the tabulations for Dataset S7. Matthew Clair and Alix S. Winter kindly offered comments on multiple iterations of this article. I also thank Frank Edwards, Filiz Garip, Jackelyn Hwang, Katherine Morris, Michela Musto, Aliya Saperstein, Florencia Torche, and the anonymous reviewers for their feedback. I acknowledge funding from the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University, as well as additional support from the Center for the Study of Inequality at Cornell University and the Cornell Population Center’s Training Program. Any errors are authorial.

Footnotes

The author declares no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

†A nascent effort to investigate naturalized citizens for possible denaturalization—preceding but expanding under the Trump administration—is underway. However, contemporary instances of denaturalization remain rare. Whether denaturalization targets naturalized citizens from Latin America is unknown.

‡Source: University of Southern California Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration analysis of 2017 5-y American Community Survey microdata from Integrated Public Use Microdata Series-USA on behalf of the author. See Dataset S7 for complete information.

§Visa overstays have exceeded undocumented entries in their contribution to the total number of undocumented immigrants in the United States since 2007. In 2014, visa overstays accounted for two-thirds of the entire undocumented population in the country (38).

¶The population of Latino US citizen adults in the United States in 2007 was ∼17,613,000; it was ∼28,394,000 in 2018. The 6.4% raw increase in deportation fears among US citizens between 2007 and 2018 amounts to an additional 5 million US citizens fearful of deportation.

#The 2011, 2012, and 2014 surveys lack data on respondents’ reported deportation fears.

‖The Google Trends measure is highly correlated (r = 0.88) with a measure of the relative mention of “deport*” in four major national newspapers throughout the survey period: The New York Times, The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and The Wall Street Journal. See the replication package.

**In 2012 alone, which does not include a measure of deportation fears, Pew asked respondents whether they know someone who has applied for DACA. Latino US-born (0.24 [0.20, 0.28]) and naturalized citizens (0.29 [0.23, 0.37]) are as likely to know someone who has applied for DACA (contrast: 0.05 [−0.03, 0.13]).

††The Trump administration (2018) is excluded from this analysis, which requires at least two data points per administration. The similar deportation rates between 2016 and 2018, coupled with the fluctuating Google Trends measure during the same period, are nonetheless consistent with the idea that a growing national awareness of—rather than observable changes to—deportation policy and practice underlie the results.

‡‡See Dataset S7.

Data deposition: All data replication files from this article are posted at Harvard Dataverse (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/REQH8F).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1915460117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Department of Homeland Security , Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: Table 39 (Department of Homeland Security, Washington, DC, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asad A. L., On the radar: System embeddedness and Latin American immigrants’ perceived risk of deportation. Law Soc. Rev. 54, 133–167 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baum J., In the Child’s Best Interest? The Consequences of Losing a Lawful Immigrant Parent to Deportation (DIANE Publishing, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massey D. S., Bartley K., The changing legal status distribution of immigrants: A caution. Int. Migr. Rev. 39, 469–484 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menjívar C., Liminal legality: Salvadoran and Guatemalan immigrants’ lives in the United States. Am. J. Sociol. 111, 999–1037 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stumpf J. P., The crimmigration crisis: Immigrants, crime, and sovereign power. Am. Univ. Law Rev. 56, 367 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain E., The interior structure of immigratoin enforcement. Univ. Pa. Law Rev. 167, 1–50 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moinester M., Beyond the border and into the heartland: Spatial patterning of U.S. immigration detention. Demography 55, 1147–1193 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golash-Boza T., Hondagneu-Sotelo P., Latino immigrant men and the deportation crisis: A gendered racial removal program. Lat. Stud. 11, 271–292 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chávez L. R., The Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation (Stanford University Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steel Z., et al. , Impact of immigration detention and temporary protection on the mental health of refugees. Br. J. Psychiatry 188, 58–64 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patler C., Golash‐Boza T. M., The fiscal and human costs of immigrant detention and deportation in the United States. Sociol. Compass 11, e12536 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asad A. L., Clair M., Racialized legal status as a social determinant of health. Soc. Sci. Med. 199, 19–28 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castañeda H., et al. , Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 36, 375–392 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Genova N. P., Migrant “illegality” and deportability in everyday life. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 31, 419–447 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abrego L. J., Relational legal consciousness of US citizenship: Privilege, responsibility, guilt, and love in Latino mixed‐status families. Law Soc. Rev. 53, 641–670 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enriquez L. E., Multigenerational punishment: Shared experiences of undocumented immigration status within mixed‐status families. J. Marriage Fam. 77, 939–953 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flores R. D., Schachter A., Who are the “illegals”? The social construction of illegality in the United States. Am. Sociol. Rev. 83, 839–868 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryo E., Peacock I., Denying citizenship: Immigration enforcement and citizenship rights in the United States. Stud. Law Polit. Soc., 10.2139/ssrn.3463902 (2019). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flynn M., ICE detained US citizen for nearly a month over paperwork problem, attorney says. The Washington Post, 24 July 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2019/07/23/francisco-erwin-galicia-ice-cpb-us-citizen-detained-texas/. Accessed 18 March 2020.

- 21.Allen C. D., Who loses public health insurance when states pass restrictive omnibus immigration-related laws? The moderating role of county Latino density. Health Place 54, 20–28 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fix M. E., Passel J. S., “Trends in noncitizens’ and citizens’ use of public benefits following welfare reform: 1994–97” (The Urban Institute, Washington, DC, 1999).

- 23.Van Hook J., Welfare reform’s chilling effects on noncitizens: Changes in noncitizen welfare recipiency or shifts in citizenship status? Soc. Sci. Q. 84, 613–631 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Hook J., Balistreri K. S., Ineligible parents, eligible children: Food stamps receipt, allotments, and food insecurity among children of immigrants. Soc. Sci. Res. 35, 228–251 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vargas E. D., Immigration enforcement and mixed-status families: The effects of risk of deportation on Medicaid use. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 57, 83–89 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vargas E. D., Pirog M. A., Mixed‐status families and WIC uptake: The effects of risk of deportation on program use. Soc. Sci. Q. 97, 555–572 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watson T., Inside the Refrigerator: Immigration Enforcement and Chilling Effects in Medicaid Participation (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allen B., Cisneros E. M., Tellez A., The children left behind: The impact of parental deportation on mental health. J. Child Fam. Stud. 24, 386–392 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ayón C., Marsiglia F. F., Bermudez-Parsai M., Latino family mental health: Exploring the role of discrimination and familismo. J. Community Psychol. 38, 742–756 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lopez W. D., et al. , Health implications of an immigration raid: Findings from a Latino community in the midwestern United States. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 19, 702–708 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suárez-Orozco C., Yoshikawa H., Teranishi R., Suárez-Orozco M., Growing up in the shadows: The developmental implications of unauthorized status. Harv. Educ. Rev. 81, 438–473 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshikawa H., Immigrants Raising Citizens: Undocumented Parents and Their Young Children (Russell Sage Foundation, New York, NY, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gemmill A., et al. , Association of preterm births among US Latina women with the 2016 presidential election. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e197084 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Novak N. L., Geronimus A. T., Martinez-Cardoso A. M., Change in birth outcomes among infants born to Latina mothers after a major immigration raid. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 839–849 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torche F., Sirois C., Exposure to restrictive immigration law in Arizona reduces birth weight of Latina immigrant women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 188, 24–33 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Enriquez L. E., Millán D., Situational triggers and protective locations: Conceptualising the salience of deportability in everyday life. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud., 10.1080/1369183X.2019.1694877 (2019). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menjívar C., Lakhani S. M., Transformative effects of immigration law: Immigrants’ personal and social metamorphoses through regularization 1. Am. J. Sociol. 121, 1818–1855 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warren R., Kerwin D., The 2,000 mile wall in search of a purpose: Since 2007 visa overstays have outnumbered undocumented border crossers by a half million. J. Migr. Hum. Secur. 5, 124–136 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobs E. M., Pathways to permanence. Front. Sociol. 4, 44 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kreisberg A. N., Starting points: Divergent trajectories of labor market integration among US lawful permanent residents. Soc. Forces 98, 849–884 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Asad A. L., Deportation decisions: Judicial decision-making in an American immigration court. Am. Behav. Sci. 63, 1221–1249 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Long J. S., Mustillo S. A., Using predictions and marginal effects to compare groups in regression models for binary outcomes. Sociol. Methods Res., 10.1177/0049124118799374 (2018). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asad A. L., Replication data for “Latinos’ deportation fears by citizenship and legal status, 2007 to 2018.” Harvard Dataverse. 10.7910/DVN/REQH8F. Deposited 12 March 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Asad A. L., Rosen E., Hiding within racial hierarchies: How undocumented immigrants make residential decisions in an American city. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 45, 1857–1882 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Massey D. S., Durand J., Pren K. A., Why border enforcement backfired. Am. J. Sociol. 121, 1557–1600 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DiGrazia J., Using internet search data to produce state-level measures: The case of tea party mobilization. Sociol. Methods Res. 46, 898–925 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clark A., 2007 National Survey of Latinos: As Illegal Immigration Issue Heats up, Hispanics Feel a Chill (Pew Hispanic Center, Washington, DC, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lopez M. H., Minushkin S., Center P. H., Hispanics See Their Situation in US Deteriorating; Oppose Key Immigration Enforcement Measures (Pew Hispanic Center, Washington, DC, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 49.López M. H., Taylor P., Funk C., Gonzalez-Barrera A., On Immigration Policy, Deportation Relief Seen as More Important than Citizenship (Pew Research Center, Washington, DC, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones B. S., et al. , Trump-induced anxiety among Latina/os. Group Process. Intergroup Relat., 10.1177/1368430219889132 (2019). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patler C., Hamilton E., Meagher K., Savinar R., Uncertainty about DACA may undermine its positive impact on health for recipients and their children. Health Aff. 38, 738–745 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Flores R. D., Can elites shape public attitudes toward immigrants?: Evidence from the 2016 US presidential election. Soc. Forces 96, 1649–1690 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Joseph T. D., The documentation status continuum: Citizenship and increasing stratification in American life. 10.31235/osf.io/2x6hq (13 March 2020). [DOI]

- 54.Asad A. L., Hwang J., Indigenous places and the making of undocumented status in Mexico-US migration. Int. Migr. Rev. 53, 1032–1077 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lopez M. H., Gonzalez-Barrea A., Motel S., “As deportations rise to record levels, most Latinos oppose Obama’s policy” in Hispanic Trends (Pew Research Center, Washington, DC, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chishti M., Pierce S., Bolter J., The Obama record on deportations: Deporter in chief or not? Migration Policy Institute, 26 January 2017. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/obama-record-deportations-deporter-chief-or-not. Accessed 12 March 2020.

- 57.Aptekar S., The Road to Citizenship: What Naturalization Means for Immigrants and the United States (Rutgers University Press, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grace B. L., Bais R., Roth B. J., The violence of uncertainty: Undermining immigrant and refugee health. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 904–905 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wessler S. F., Is denaturalization the next front in the Trump administration’s war on immigration? NY Times, 19 December 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/19/magazine/naturalized-citizenship-immigration-trump.html. Accessed 12 March 2020.

- 60.Moinester M., A look to the interior: Trends in US immigration removals by criminal conviction type, gender, and region of origin, fiscal years 2003–2015. Am. Behav. Sci. 63, 1276–1298 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 61.US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Fiscal year 2018 ICE enforcement and removal operations report (US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Washington, DC, 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

A replication package containing all data and code used in this analysis is available through the Harvard Dataverse (43).