Abstract

Deficits in self-regulation (SR) have been proposed as a potential contributor to child overweight/obesity, a public health concern that disproportionately affects children living in poverty. Although poverty is known to influence SR, SR has not been considered as a potential mechanism in the association between poverty and child obesity. The aim of the current paper was to systematically review the current literature to determine whether SR is a viable mechanism in the relationship between child exposure to poverty and later risk for overweight/obesity. We systematically review and summarize literature in three related areas with the aim of generating a developmentally informed model that accounts for the consistent association between poverty and child weight, specifically how: 1) poverty relates to child weight, 2) poverty relates to child SR, and 3) SR is associated with weight. To quantify the strength of associations for each pathway, effect sizes were collected and aggregated. Findings from the studies included suggest small but potentially meaningful associations between poverty and child SR and between SR and child weight. The conceptualization and measurement of SR, however, varied across literatures and made it difficult to determine whether SR can feasibly connect poverty to child obesity. Although SR may be a promising potential target for obesity intervention for low-income children, additional research on how SR affects risk for obesity is crucial, especially based on the lack of success of the limited number of SR-promoting interventions for improving children’s weight outcomes.

Keywords: poverty, obesity, BMI, self-regulation, food insecurity

Introduction

Pediatric obesity is a public health concern that affects children’s quality of life and their current and future health outcomes. Seventeen percent of U.S. children ages 2–19 are estimated to be obese, and an additional 15% overweight (Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal 2012), with these numbers reflecting a substantial increase over the past several decades (Ogden et al. 2016). Although the medical problems associated with overweight may not become apparent until adulthood (e.g., cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome), the risk of adult obesity is known to be greater for children who are overweight in childhood (Simmonds, Llewellyn, Owen, & Woolacott 2016). Furthermore, overweight and obese children report lower quality of life (Friedlander, Larkin, Rosen, Palermo, & Redline 2003) and social isolation (Strauss & Pollack 2003). Unfortunately, research on child obesity prevention and treatment has only recently started to include children from low-income families (Kimbro, Brooks-Gunn, & McLanahan 2007; Shrewsbury & Wardle 2008), who tend to be at greater risk for weight problems. Obesity prevention and treatment may be especially challenging for children living in poverty because of increased exposure to environmental stress and chaotic living conditions (Evans & English 2002).

There are many adverse psychosocial outcomes associated with exposure to poverty in childhood. Family income and other markers of financial hardship have been found to have detrimental effects on children’s academic achievement (Votruba-Drzal 2006), behavior (Eamon 2002), and mental (Dearing, McCartney, & Taylor 2006) and physical health (Lawlor, Ronalds, Macintyre, Clark, & Leon 2006). Poverty has also been established as a potent risk factor for child overweight and obesity (Alaimo, Olson, & Frongillo 2001; Cameron et al. 2015), an association that at first glance may appear paradoxical. Historically, poverty has been associated with inability to afford food, leading to malnutrition and underweight. Several mechanisms for this association have been proposed, with most focused on the premise that children living in poverty tend to eat more high calorie, low-nutrient foods and have less access to opportunities for physical activity (Drewnowski & Specter 2004; Sallis & Glanz 2006).

Although both family-based (Epstein, Valoski, Wing, & McCurley 1990) and community interventions (Bleich, Segal, Wu, Wilson, & Wang 2013) have been developed to address and prevent child overweight, few have been found to have lasting effects on child weight (Ebbeling, Pawlak, & Ludwig 2002). Most intervention efforts fall broadly in the category of “lifestyle interventions,” with a relatively narrow focus on decreasing calorie intake and increasing physical activity (T. Brown & Summerbell 2009; McCallum et al. 2007; Nemet et al. 2005); prevention efforts tend to focus on similar objectives (Economos et al. 2007; Hollar et al. 2010). However, targeting these areas has proven surprisingly and frustratingly resistant to long-term change. Theoretically, these behaviors may be even more challenging to modify in low-income children because of lack of access to nutritionally sound food and limited opportunities for physical activity.

Historically, child obesity treatment and prevention efforts have not taken into account differences in children’s developmental status. “Sensitive periods” during which excessive child weight gain is particularly strongly linked to later obesity have been identified (i.e., during middle childhood in a period known as “adiposity rebound,” and during adolescence when they go through puberty (Dietz 1994). However, knowledge about development has infrequently been incorporated into designing targeted treatment and prevention efforts for children at specific development stages, nor has it been systematically evaluated as a moderator of treatment efficacy in reviews or meta-analyses (Ho et al. 2012). In addition, few researchers have evaluated whether the effect of poverty on child weight varies depending on the timing and duration of poverty exposure at different developmental stages of childhood.

Because of the lack of success in reducing children’s weight by modifying their energy balance, it could prove valuable to investigate potential alternative mechanisms leading to child obesity as targets of prevention and/or intervention (i.e., focusing on nutrition and physical activity), targets that might be more malleable than diet or physical activity. Although addressing energy balance in children is the ultimate goal to promote and sustain healthy weight maintenance, it has become clear that addressing childhood obesity by focusing narrowly and primarily on children’s calorie intake and physical activity has shown limited success. Identifying broader behavioral styles that may underlie children’s tendencies to overeat and/or be physically inactive and exploring how such behavioral styles may exacerbate continued weight gain could prove helpful in improving obesity prevention efforts in particular. Such issues may be particularly critical for children living in poverty because of their greater exposure to contexts that promote obesity.

A critical attribute for children’s social and academic success that has been linked to poverty is self-regulation. Self-regulation (SR) encompasses one’s ability to modulate behavior and emotions in response to internal and external demands and is often conceptualized using a dual process model consisting of “hot,” reactive processes (e.g., impulsivity) and a “cool,” reasoned, cognitive system (Isasi & Wills 2011; Metcalfe & Mischel 1999). Children living in poverty have been postulated and found to show lower levels of SR because of their greater exposure to witnessing and experiencing violence and trauma, more frequent changes in residence, and both exposure to and genetic risk of mental health problems among family members (Evans & English 2002; Lengua, Honorado, & Bush 2007; Raver 2004). As SR is vital for helping children manage their emotions and behavior, it is not surprising that deficits in SR have been linked to a variety of adverse outcomes for children and adults, including peer rejection in middle childhood (Trentacosta & Shaw 2009), antisocial behavior in adolescence (Sitnick et al. 2017), and importantly, physical health in adulthood (Moffitt et al. 2011). As maintenance of healthy body weight involves appropriate SR of energy intake, it follows that SR has been found to be associated with child body mass index (BMI), overweight, and obesity in both cross-sectional studies (Miller, Rosenblum, Retzloff, & Lumeng 2016) and longitudinal ones (Francis & Susman 2009; Paulo A Graziano, Calkins, & Keane 2010; Seeyave et al. 2009).

As child weight and poverty have been associated with multiple components of SR, SR may be especially important in explaining how poverty affects child weight. In addition, as SR has been found to be malleable using school-, family-, and individual-based approaches during multiple developmental periods (Johnson 2000; Raver et al. 2011; Riggs, Greenberg, Kusché, & Pentz 2006; Shelleby et al. 2012), it represents a viable target for prevention and intervention. However, almost no studies have investigated the potential mediating role of SR in associations between poverty and child weight.

The current review summarizes literature in three related areas with the aim of generating a developmentally informed model that accounts for the consistent association between poverty and child weight, specifically how: 1) poverty relates to child weight, 2) poverty relates to child SR, and 3) SR is associated with weight. Although there is a relatively rich literature documenting each of these direct paths, extremely few empirical papers have attempted to integrate these literatures to investigate the possibility that SR might mediate associations between poverty and child weight. Further, a developmental approach to this literature can determine whether there are sensitive developmental periods during which child weight and SR are particularly vulnerable to the effects of poverty. In addition to summarizing and consolidating the evidence from studies across two separate literatures (i.e., obesity literature and SR literature), the goal of this paper was also to determine whether SR could be a viable target for obesity prevention for children living in poverty.

This review includes only longitudinal studies, which, in the absence of an experimental design, are necessary for establishing a case for the presence of causal mechanisms among variables of interest. Without a longitudinal design in which baseline levels of the variable of interest are included in the model, the possibility of other variables driving the association, or that variables simply cooccur without a causal relationship, is difficult to rule out.

Methods

Operational definitions of variables

Poverty/Financial Hardship.

Although poverty can be defined and operationalized in many ways, the current review focused specifically on studies that define poverty based on income and/or financial strain. Studies often use measures of poverty that aggregate multiple indicators of socioeconomic status (SES), including income but also variables such as parental education and occupation. This review included studies that used such composites as long as income or another proxy for financial strain was included. Although parental education and occupation may play some role in influencing children’s weight (Lamerz et al. 2005), there is a stronger rationale for focusing on income specifically, as it is more malleable and its measurement more straightforward than other aspects of SES.

This review also includes studies in which income/financial strain was incorporated into a cumulative risk index that included other risks and stressors. The use of cumulative risk indices has strong theoretical and empirical support, with the rationale being that although the effect of any single risk may be small, multiple risks in combination are particularly detrimental and more damaging than their individual additive effects (Forehand, Biggar, & Kotchick 1998). Children living in poverty are much more likely to be exposed to multiple, interrelated risks, such as exposure to violence, substandard housing, marital conflict, and maternal psychopathology (Evans & Kim 2007; Rutter et al. 1997).

Lastly, food insecurity (FI) was also considered a measure of poverty/financial strain, as a family’s FI status indicates the presence or absence of an important resource (food) that is closely tied to financial hardship. FI has been defined by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) as “reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet,” with or without the presence of “disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake” (i.e., with or without hunger) (ColemanJensen, Gregory, & Singh 2014). FI is most commonly measured using an 18-item scale developed by the USDA (Hamilton & Cook 1997).

When income or an income-to-needs ratio was used as the indicator of poverty, the word “income” is used to encompass both. The term “SES” is used when the study employed a measure that included not only income but also either parental education, occupational status, or both. The term “poverty” is used to refer broadly to all measures of poverty or poverty-related stressors included in this review, including income, SES, cumulative risk, and FI.

Self-Regulation.

The definition of SR and its various components varies greatly and is frequently inconsistent across studies. Conceptually, the construct of SR is quite broad and is thus frequently deconstructed into distinct but often closely related components. However, these components (e.g., effortful control, inhibitory control, emotion regulation) may be difficult to differentiate, in part because there are no tasks that “cleanly” measure one without involving the others. Furthermore, the language used to label and categorize SR and its components is quite variable, with different terms being used to describe the same processes, and vice versa, and different literatures tending to adopt divergent language for describing SR.

In spite of these issues, overarching themes to characterize SR have emerged across disparate literatures. For one, it is common for researchers to conceptualize SR processes using some kind of a dual process model. A particularly common and well-accepted model conceptualizes SR as consisting of two systems referred to as “hot” and “cool” (Metcalfe & Mischel 1999). Hot SR is thought to be engaged in emotionally arousing situations, including tasks with “appetitive demands,” whereas cool SR is deployed primarily in emotionally neutral contexts and involves more conscious, cognitive attentional processes and planful reactions (Eisenberg & Zhou 2016). Cool SR overlaps with the construct of executive functioning as it is typically conceptualized (Willoughby, Kupersmidt, VoeglerLee, & Bryant 2011).

In the current review, regardless of how authors referred to constructs and measures in their papers, behavioral measures were categorized as “hot” or “cool” based on the author’s evaluation of the SR domain each task intended to measure, with measures that involved regulation or inhibition with an emotional or appetitive component categorized as “hot,” and emotionally neutral tasks as “cool.” One commonly used measure of hot SR is delay of gratification (DoG). In a DoG task, children are presented with some desired object or food (for example, a cookie), and are told that they can either eat one cookie now, or have two cookies later. During the waiting period, children are usually left alone with the desired object/food with no other opportunities for entertainment or distraction and they can alert the experimenter at any time to indicate that they are unable to wait any longer. Refer to Table 1 for a summary of how additional common observed measures of SR were categorized as “hot” or “cool.”

Table 1.

Examples of observed self-regulation measures categorized as hot versus cool

| Hot | Cool |

|---|---|

| Delay of gratification (food/non-food) (e.g., Seeyave et al., 2009) | Stroop and Stroop-like tasks (e.g., Lengua et al., 2007) |

| Gift delay (e.g., Thompson et al., 2013) | Motor control tasks (e.g., Balance Beam task) (e.g., Bassett et al., 2012) |

| High chair frustration task (Graziano et al., 2010) | Opposite of Commands task (e.g., Head-to-Toes) (e.g., Wanless et al., 2011) |

| Continuous Performance Test (e.g., Bub et al., 2016) |

A variety of methodologies for the measurement of child SR is included in the current review, such as observed measures of child SR and parent or teacher reports on questionnaires. Nearly all questionnaire measures assessing child SR capture aspects of both hot and cool domains. For example, items from the inhibitory control subscale of the Child Behavior Questionnaire (Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher 2001) measure both “hot” emotional, impulsive behaviors such as “has an easy time waiting to open a present,” and “cool,” measured behaviors or processes, as in “likes to plan carefully before doing something.” Therefore, in the current review, questionnaire measures are not categorized as “hot” or “cool.”

In her conceptualization of SR, Calkins (2007) adds a physiological component in addition to the systems she refers to as “emotional” and “attentional” (which map onto hot and cool SR, respectively). She highlights the importance of heart rate variability (HRV) as a measure of parasympathetic nervous system activation, which is crucial in modulating emotion regulation and reactivity (Calkins & Dedmon 2000; Porges 2007). Thus, measures of HRV such as respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) are also considered a marker of SR in the current review and categorized as “physiological.” Physiological SR is subsumed under the category of hot SR, as it is thought to be more relevant in situations that require the regulation of emotional or behavioral arousal.

Studies that used both observed and questionnaire methods that specifically assessed eating or appetite components of SR (e.g., emotional overeating) were also included and considered as a category separate from hot and cool SR, as SR of appetite likely contains aspects of both hot and cool SR. For example, some children may overeat as a way to cope with and/or regulate negative emotions (Goossens, Braet, Van Vlierberghe, & Mels 2009), which would capture aspects of hot SR. Alternatively, features of cool SR may be employed when children consciously restrain themselves from eating large amounts of palatable but unhealthy foods, an eating behavior that has been observed in children as young as 5 years old (Carper, Fisher, & Birch 2000).

The aspects of SR featured in this review had to be viable candidates for mediating the association between poverty and weight. Although there are alternative models for understanding SR, the hot/cool distinction was selected to categorize SR measures because the SR of healthy weight maintenance likely involves both emotional and cognitive processes.

Child Weight.

Two ways of operationalizing weight were used in the studies included in this review. The first is using BMI, a continuous variable, as the outcome of interest, and the second is using weight status, a categorical outcome variable such as the presence or absence of overweight and/or obesity. The use of BMI has the advantage of allowing for trajectories of weight gain over time to be analyzed with respect to income or income changes, while weight status offers the ability to differentiate clinically significant from normal child weight.

There is some evidence to suggest that weight status measured after approximately age two is relatively stable throughout childhood. Findings from one study suggest that children categorized as normal weight or obese at as early as age 3 were likely to remain the same weight status at age 15 (Tran, Krueger, McCormick, Davidson, & Main 2016). However, some research indicates that early childhood BMI is a poor predictor of later childhood weight when it is measured prior to adiposity rebound, when normative increases in BMI start to occur in all children, usually by the age of 6 (Rolland-Cachera, Deheeger, Maillot, & Bellisle 2006). Therefore, it is important to consider the age that weight was measured before drawing conclusions about the effects (or lack thereof) of environmental (e.g., exposure to poverty) or child characteristics (e.g., SR) on child weight.

Age periods covered

This review focuses on longitudinal studies in which the final measurement of the independent variable (poverty or SR) was prior to age 10, as exposure to poverty during early and middle childhood was of primary interest because of the possible implications for obesity prevention. Additionally, the review excluded studies in which the last measurement of the dependent variable (weight or SR) was after age 18, as the scope of the review was limited to childhood and adolescence. Studies that measured weight prior to age 2 were also excluded, as some research suggests that this early in childhood, child overweight/obesity is a poor predictor of later excess weight (Whitaker, Wright, Pepe, Seidel, & Dietz 1997).

To gain an understanding of which developmental stages have been most studied with regard to the pathways of interest and whether there were differences in the strength of associations depending on stage, age periods were categorized as follows: Early Childhood (0–5), Middle Childhood (6–11), and Adolescence (12–18).

Inclusion of Studies

Articles for the current review were identified through searches using the databases PsycINFO and PubMed. Separate searches were conducted for each of the three pathways. 1) SES search terms (appearing in title and/or abstract) were as follows: socioeconomic, poverty, income, cumulative risk, adversity, and food insecurity. 2) SR keywords, also in the title or abstract, consisted of the following: regulat* (the asterisk denotes that a word stem was searched), executive function, inhibitory control, executive control, effortful control, delay of gratification, eating in the absence of hunger, overeat*, appetit*, impulsiv*, and attent*. 3) Weight search terms appearing in the title or abstract were: body mass index, BMI, overweight, obes*, weight. For all, the term child*, boy, or girl had to appear in the abstract.

As an example, for the poverty→weight pathway, PsycINFO was searched first using the terms “socioeconomic” and “body mass index.” The search was repeated until every combination of the “poverty” and “weight” search terms had been entered. The citation for every article that resulted from each search was downloaded to a file for review. This search was then repeated in an identical fashion using the PubMed database. This procedure was then repeated for the poverty→SR (using the “poverty” and “SR” keywords) and SR→weight (using the “SR” and “weight” search terms) searches.

Next, some studies were identified using reference lists of the initial articles, and also searching for papers that cited them. Only longitudinal studies, where the dependent variable was measured after the independent variable, were included in the formal review. Experimental studies where poverty or SR was manipulated as part of an intervention were also included. Although many child weight loss interventions involve some aspect of SR (Braet, Tanghe, Decaluwé, Moens, & Rosseel 2004; Epstein, Wing, Koeske, Andrasik, & Ossip 1981), only studies that specifically measured SR pre- and post-intervention were included in the review on the SR to weight pathway.

Upon completion of the searches in PsycINFO and PubMed, the results for each pathway were compiled and duplicates were removed. Each article was reviewed to determine its appropriateness for inclusion in the systematic review. Inclusion criteria were as follows: a) published in a peer-reviewed journal, b) published or available in English, c) normative sample (i.e., excluded studies that tested associations with specific populations like very low birth weight infants or children prenatally exposed to substances, d) longitudinal, with at least 6 months between assessments (several studies used assessments at the beginning and end of school years). Studies were excluded if they were part of an intervention study (e.g., an early childhood intervention that tested SR as an outcome and included family income as a covariate), unless it was a weight loss intervention that specifically targeted SR. There were several other exclusion criteria that were unique to one of the pathways; these are described in the section specific to that pathway.

For the two pathways in which poverty was the independent variable, in some cases the poverty variable was measured when mothers were pregnant with the target child -- these studies were included in the review. In addition, it was frequently the case that poverty (usually income) was operationalized using an average of family income across multiple years of assessment. For example, one study averaged income over three years of assessment (when children were 5, 7, and 9 years old), with the outcome for BMI at age 9 (Tiberio et al. 2014). These studies were included as long as there were at least two other assessment points included in the SES variable in addition to the concurrent assessment (i.e., the age 9 assessment in this example). However, studies were excluded if they tested trajectories of family income or chronicity of poverty over a period of more than five years, as such analyses are not directly comparable to those testing poverty exposure at a single assessment point. Similarly, studies that tested growth in child weight or children’s weight trajectories over time were also excluded.

The review was primarily concerned with the relationship between poverty and obesity in the United States, although this phenomenon has been well documented in many other high-income countries. Therefore, studies with non-U.S. samples were included if the World Bank defined the country as a “high-income economy,” as the U.S. is categorized. This classification is based on gross national income per capita; those with a GNI of $12,056 per capita are considered high-income. As the pattern of the relationship between poverty and weight for individuals living in low-income countries may differ compared to high-income countries, and the relationship for individuals in middle-income countries appears to be inconsistent (Dinsa, Goryakin, Fumagalli, & Suhrcke 2012), the attention of the current review was focused on high-income countries.

Effect size aggregation

Articles that met criteria for the review were searched to locate the unadjusted relationship between the two variables of interest (e.g., bivariate, zero-order correlation, unadjusted odds ratio). In addition to effect size, the following information was also extracted from each paper that met inclusion criteria: age that the independent variable was measured, age(s) that the dependent variable was measured, how poverty was operationalized, type of SR (if applicable), and information about the sample, including the country where the study took place and whether it was described in the paper as predominantly low-income.

For the poverty→weight pathway, an overall total aggregated effect size was calculated for each pathway, along with three different effect sizes stratified by developmental stage (i.e., early childhood, middle childhood, adolescence), as one goal of the study was to determine whether the relationship between poverty and weight differed depending on when weight was measured. Similarly, for the poverty→SR and SR→ weight pathways, three different effect sizes were calculated based on which type of SR was tested (hot, cool, or questionnaire). For the SR→ weight pathways, it would have been ideal to assess age of outcome in addition to SR type, but the cell sizes would have been too small to detect meaningful differences in effect sizes. In addition, a “total effect size” was calculated without consideration of developmental stage or SR type.

If an unadjusted measure of effect size was not included in the manuscript, the first and/or corresponding author of the paper was contacted by email to request the necessary information. Only studies with an effect size were retained for inclusion in the systematic review. After any one sample was represented in the effect size list for a given pathway, authors of other papers that used the same sample were no longer contacted if the effect size information was not included in the manuscript. If effect size information from the same sample was available from more than one paper, effect sizes were averaged into a single “entry” for that sample.

One exception to the above rule was that if the developmental stage during which BMI was measured (for the poverty→ weight pathway) or the type of SR measured (for the poverty→SR and SR→ weight pathways) differed across multiple papers that used the same sample, multiple effect sizes were retained. For example, for the poverty→weight pathway, three studies utilized the Fragile Families dataset (Assari, Thomas, Caldwell, & Mincy 2018; Burdette & Whitaker 2007; Starkey & Revenson 2014). Although in all three papers researchers used the same measure of poverty (income at birth), each assessed their outcome of obesity or weight at a different age, with Burdette and Whitaker (2007) using obesity at age 3 (early childhood), Starkey and Revenson (2014) using BMI at age 9 (middle childhood), and Assari and colleagues (2018) testing effects on BMI at age 15 (adolescence). Therefore, the effect sizes for all three papers were retained for the analysis by developmental stage, but not for a separate “total effect size” that was calculated without consideration of age of outcome.

Effect sizes were transformed such that all were consistently representing the relationship between poverty and weight. For example, if the variable for “poverty” used in the study was a continuous measure of family income, operationalized as dollars per year, the sign (+/−) was reversed so that it became an index of poverty rather than income (i.e., a positive r indicates that high poverty/low income is associated with higher BMI). Similarly, for the poverty→SR and SR→weight pathways, the way in which SR was operationalized was considered prior to aggregating effect sizes. When the variable of interest was operationalized in a study as a lack of SR (e.g., impulsivity, eating more in the absence of hunger), the sign was reversed to ensure consistency across studies.

Review of Literature

Longitudinal research linking poverty and food insecurity to childhood weight

Included in the review were studies in which the primary research aim was to assess the relationship between poverty and weight, and also studies in which the primary independent variable of interest was not poverty or SES, but some other variable (e.g., breastfeeding, parental smoking), with SES included as a covariate in analyses.

Results of aggregated effect size analysis for longitudinal associations between poverty exposure and weight.

Use of the search methodology described above resulted in the identification of 4,156 articles. Of those, 130 were found to meet criteria for inclusion in the review. Eighteen studies included effect size information in the paper. For 49 studies, authors were emailed. Of those, 17 provided effect size information. Twenty-five unique samples were represented in the analysis, with an additional five studies being from duplicate samples in which more than one paper included an effect size (in these cases, effect sizes were averaged across studies). Fifty-seven papers were from duplicate samples (e.g., ECLS-K, n =14; NICHD SECCYD, n = 9; NLSY79, n = 9) where the effect size was not available in the paper. As described above, authors were not emailed to obtain effect size information for studies that used duplicate samples (i.e., those samples for which an effect size had already been obtained via the paper itself or an email to the author).

Effect sizes were converted to r from odds ratios, risk ratios, spearman’s rho, and Cohen’s d (which was usually calculated by the first author using a table included in the paper) using an effect size calculation website (Lenhard & Lenhard 2016). Studies that had effect sizes of r ≥ .10 were enumerated, as r = .10 is generally considered to be the lower limit for what should be considered a “small” effect size (Cohen 1992). Out of the 25 effect sizes from the 25 unique samples, 14 exceeded that threshold with effect sizes of r ≥ .10 in the expected direction (i.e., greater poverty associated with higher weight) (see Tables 2 and 3). Two effect sizes were in the opposite direction, with correlation coefficients for the association between poverty and weight in the −.10 to −.20 range (i.e., higher poverty associated with lower weight) (Coley & Lombardi 2012; Tiberio et al. 2014). The total average effect size for the longitudinal association between poverty and weight was r = .09.

Table 2.

Studies with a positive relationship and effect size ≥ .10 for poverty-weight pathway

| Author | Sample | r (converted) |

|---|---|---|

| Bhargava (2008) | ECLS-K, N=7635 | 0.16 |

| Li (2007); Strauss (1999) | NLSY79; N=1739; 2913 | 0.24 |

| Williams (2018); Gibbs (2014) | ECLS-B; N=7022 | 0.12 |

| Evans (2012) | Community sample (NY); N=244 | 0.19 |

| Tandon (2015) | Community sample (WA); N=306 | 0.24 |

| Baldwin (2016) | E-Risk twins; N=2232 | 0.16 |

| Holm-Denoma (2014) | Community sample (OR); N=38 | 0.16 |

| Lee (2014); Lane (2013) | NICHD SECCYD; N=1150; 1238 | 0.11 |

| Hancock (2014) | Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC); N=2596 | 0.18 |

| Sen (2017) | Project VIVA; N=992 | 0.12 |

| Bush (2017) | Peers and Wellness Study; N=338 | 0.17 |

| Van Hulst (2015) | QUALITY Quebec; N=512 | 0.13 |

| Lim (2011) | Community sample (MI); N=317 | 0.39 |

| Strobino (2016) | Healthy Steps for Young Children National Evaluation; N = 4745 | 0.19 |

Table 3.

Studies with a negative relationship or effect size < .10 for poverty-weight pathway

| Author | Sample | r (converted) |

|---|---|---|

| Mészáros (2008) | Hungarian sample, N = 495 | −.04 |

| Janjua (2012) | Sample recruited from University of Alabama prenatal clinic, N = 740 | .06 |

| Slopen (2012) | Avon Longitudinal Study (UK), N = 3286 | .04 |

| Baptiste-Roberts (2012) | The National Collaborative Perinatal Project, N = 28358 | .05 |

| Carter (2012) | Longitudinal Study of Child Development in Quebec, N = 1566 | −.07 |

| Collings (2017) | Born in Bradford (UK); N = 1338 | −.03 |

| van Rossem (2010) | Generation R (Netherlands); N = 2954 | −.05 |

| Kwok (2010) | Children of 1997 (Hong Kong); N = 8237 | .04 |

| Bergmeier (2014) | Australian Research Council Discovery Grant Study; N = 201 | .03 |

Strength of associations by features of the sample.

Eight papers used predominantly low-income samples, with three from the Fragile Families study (Assari et al., 2018, Burdette & Whitaker, 2007; Starkey & Revenson, 2015) and five from other samples (Baptiste-Roberts, Nicholson, Wang, & Brancati 2012; Coley & Lombardi 2012; Collings et al. 2017; Janjua, Mahmood, Islam, & Goldenberg 2012; Lim, Zoellner, Ajrouch, & Ismail 2011). Of those, five studies found little to no association between poverty and weight (with r’s ranging from .06 to .03). For the sixth study, which used a low-income sample of 322 mother-child dyads from Boston, Chicago, and San Antonio, (Coley & Lombardi 2012), the effect size was in the small to moderate range (r =.19). However, the relationship was in the opposite direction of what was expected, with higher income in early childhood (age 0–2) associated with higher rates of child overweight/obesity at age 7.

Eleven of the 25 unique samples represented were comprised of non-U.S. participants (predominantly from the U.K., but also Canada, Hungary, Australia, Korea, and Hong Kong). Of the 11 studies that used non-U.S. samples, four found evidence for a small to moderate association between poverty and weight: one of the three studies from the U.K. (Baldwin et al. 2016), one of the two from Australia (Hancock, Lawrence, & Zubrick 2014), and one of the two studies from Canada (Van Hulst et al. 2015). As an example, Hancock and colleagues (2014) used a large longitudinal dataset from Australia (N = 2596) to address their primary research question of whether maternal protectiveness was associated with greater risk of child overweight/obesity. The study, which started when children were 4–5 years old, with follow-up assessments 2, 4, and 6 years later, included income quartile as a covariate in their analyses. At each follow-up visit, the group with the lowest income at baseline was consistently found to have greater risk of overweight/obesity compared to the highest income group, with odds ratios ranging from 1.7 (at the age 8–9 visit) to 2.3 (at the age 10–11 assessment). Of the other six studies in which the association between poverty and weight was minimal, samples were drawn from the Netherlands (van Rossem et al. 2010), Hungary (Mészáros et al. 2008), Korea (I. Lee, Bang, Moon, & Kim 2016), and Hong Kong (Kwok, Schooling, Lam, & Leung 2010). When the 11 non-U.S. samples were removed from the aggregated effect size calculation, the new aggregated effect size (n = 15) was r = .12.

Food Insecurity and Child Weight.

Upon review of the literature, a separate aggregated effect size was calculated for food insecurity (FI), as the evidence of an association between FI and child weight outcomes is generally weaker than for income and SES-based measures of poverty (Gundersen, Lohman, Eisenmann, Garasky, & Stewart 2008). Five effect sizes from five different samples were included in the FI→weight pathway, all but one of which overlapped with the samples included in the poverty→weight pathway (i.e., five studies tested the associations between both income and weight and FI and weight separately). Of the five studies that tested relationships between exposure to FI and child weight, the average effect size was .07 (with r’s ranging from −.15 − .16). One study (Coley & Lombardi 2012, described above) found that early childhood FI was associated with lower rates of overweight and obesity in middle childhood (r = −.15). Three other studies found that FI was associated with higher weight in early childhood with an association of r ≥ .10. For the studies that also tested the association between poverty and weight (Bhargava, Jolliffe, & Howard 2008; Coley & Lombardi 2012), the direction and strength of the association between FI and weight were quite similar as they were for the association between poverty and weight.

Timing of exposure to poverty and weight outcome by developmental period.

In estimating effect sizes by age at which the weight outcome was measured, poverty was most strongly related to weight when weight was measured in adolescence (r = .15, n = 5), versus weight in early (r = .04, n = 7) and middle childhood (r = .07, n =14). However, none of the differences between the magnitudes of the correlation coefficients were statistically significant (z = .08, ns and z = .15, ns, for adolescence versus early childhood and adolescence versus middle childhood, respectively).

Two samples out of the seven that tested the association between poverty exposure and BMI measured in early childhood found an effect size where r ≥ .10 for the association between the two variables. Two studies used the ECLS-B, a large, representative U.S. dataset . Researchers assessed risk for overweight/obesity at age 2 (Gibbs & Forste 2014) and age 4–5 (Williams et al. 2018) by SES at birth, both finding effect sizes of small magnitude; averaged across the two studies, the effect size for this sample was r = .12. Although Gibbs and Forste found that family SES at 9 months was associated with obesity at age 2, infant feeding practices (i.e., being formula-fed and early introduction to solid foods) were a powerful mediator in this relationship. Another study using a very large sample of children across the U.S. found that lower income tertile measured when infants were 2–4 months was associated with higher risk of being in the 90th or 95th percentile of weight-for-length (a measure similar to BMI that is appropriate for infants from birth to age 2) at age 2 (Strobino et al. 2016).

It should be noted that for a majority of studies that tested exposure to poverty in early childhood (n = 20), it was not possible to assess differences in the strength of associations depending on when exposure to poverty occurred.

Summary of literature testing associations between poverty and child weight.

The overall average effect size for the pathway from poverty to child weight was small (r = .09). However, for 14 studies using 14 independent samples, the effect size was greater than r = .10, compared with nine studies where r < .10. None of the studies using a predominantly low-income sample (n = 6) found evidence for an association between poverty and weight in the expected direction. Of the studies that used a non-U.S. sample, a slight majority did not find evidence for an association between poverty and child weight. The average effect size was the strongest (r = .15) for studies that tested the relationship between poverty and weight when weight was measured in adolescence. There was no evidence that the relationship between FI and weight differed from the relationship between poverty and weight.

Longitudinal research linking poverty to childhood self-regulation

SR as a mediator in the poverty to obesity pathway.

Although other potential mechanisms are certainly involved in the pathway from poverty to child weight, SR was selected as the focus of this review because there are relatively rich literatures on 1) poverty predicting SR and 2) SR predicting child weight. In addition, SR may be more malleable than other mediators that have proven resistant to change in earlier trials (e.g., diet, physical activity) (Webster Stratton, Jamila Reid, & Stoolmiller 2008).

Similar to the poverty to weight pathway reviewed above, the review included studies in which authors primarily sought to test relationships between poverty and child SR. Also included were studies where the research question was not specifically about relations between poverty and SR, but about some other independent variable (e.g., maternal depression, family structure) and SR, with SES or family income included as a covariate in analyses.

Results of aggregated effect size analysis for longitudinal associations between poverty exposure and SR.

Searching PubMed and PsycINFO with the terms listed above for the poverty→SR pathway yielded 842 articles. Of those, 95 were found to meet criteria for inclusion in the review. Forty-one studies already reported effect size information in the paper. For 22 studies, authors were emailed to obtain this information. Of those, 15 provided data on effect sizes. Thirty-seven unique samples were represented in the effect size aggregation analysis; an additional 19 papers used an already included sample. Thus, for these already-included samples, effect sizes were averaged across these multiple studies. Twenty-four papers were from duplicate samples where the effect size was not available in the manuscript (e.g., the Family Life Project, n =10; ECLS-K, n = 2, the Early Head Start Research and Evaluation Project, n = 2).

Effect sizes for all but two of the studies in the poverty→SR pathway were already in the form of r and did not need to be converted. A total r for the association between poverty and SR was calculated. When a study tested hot, cool, and questionnaire-measured SR (or any combination of two or three of these), the highest of the r’s for any one measure was used to represent the total. The total average effect size for the longitudinal association between poverty and SR was r = −.16. As in the poverty→weight pathway, studies that had effect sizes of r ≥ .10 were tabulated. Out of the 37 effect sizes from the 37 unique samples, 28 exceeded that threshold with effect sizes of r ≥ .10 in the expected direction (i.e., greater poverty associated with lower SR) (see Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4.

Studies with a negative relationship and effect size ≥ .10 for poverty-self-regulation (SR) pathway

| Author | Sample | SR classification | r (total) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wanless (2011) | Community sample, N = 95 | Cool | −.26 |

| McClelland (2012) | Community sample, N = 34 | Cool | −.29 |

| Brown (2013) | Sample from PA Head Start, N = 205 | Cool | −.11 |

| Nesbitt (2013) | Durham Child Heath & Development Study, N = 206 | Cool | −.23 |

| Sturge-Apple (2015) | Community sample, N = 140 | Hot | −.24 |

| Lengua (2007) | Community sample, N = 70 | Questionnaire | −.26 |

| Lengua (2006) | Community sample, N = 120 | Questionnaire | −.22 |

| Thompson (2013); Tandon (2015), Lengua (2013; 2014; 2015) | Community sample, N = 306 | Hot; Cool | −.24 |

| Doan (2012) | Community sample, N = 265 | Cool; Questionnaire | −.31 |

| Sektnan (2010); Crook (2014); Dilworth-Bart (2007); Nievar (2014); Blums (2017); Pratt (2016) | NICHD SECCYD, N’s range from 10091364 | Hot; Cool; Questionnaire | −.26 |

| Conradt (2014) | Maternal Lifestyle Study, N = 1121 | Physiological | −.10 |

| Moilanen (2010) | Early Steps Study, N = 731 | Questionnaire | −.13 |

| King (2013) | Community sample, N = 214 | Questionnaire | −.17 |

| Bernier (2010; 2015); Rochette (2014) | Canadian community sample, N’s range from 60–114 | Hot; Cool; Questionnaire | −.27 |

| Suor (2018) | Community sample, N = 160 | Hot; Cool; Questionnaire | −.21 |

| Berry (2014); Vernon-Feagans (2016); Gueron-Sela (2018); Sulik (2015) | Family Life Project, N’s range from 1037–1235 | Cool; Questionnaire | −.26 |

| Bockneck (2014); Mistry (2010); Brophy-Herb (2013) | Early Head Start Research & Evaluation Project, N’s range from 1258–1851 | Cool; Questionnaire | −.16 |

| Peredo (2015) | Community sample, N = 100 | Hot | −.19 |

| Kidwell (2007) | Community sample, N = 56 | Questionnaire | −.27 |

| Sabol (2018) | National Center for Research on Early Childhood Education study, N = 211 | Cool | −.15 |

| Wade (2018) | Healthy Babies Healthy Children (Canada), N = 501 | Cool | −.13 |

| Eisenberg (2010) | Community sample, N = 209 | Hot; Questionnaire | −.18 |

| Gartstein (2013) | Community sample, N = 147 | Cool | −.13 |

| Martoccio (2014) | Sample from MI Head Start, N = 127 | Cool | −.12 |

| Hartanto (2018) | ECLS-K | Cool; Questionnaire | −.19 |

| Bassett (2012) | Community sample, N = 261 | Hot; Cool | −.15 |

| Evans (2005) | Community sample, N = 329 | Questionnaire | −.29 |

| Abenavoli (2015) | Community sample N = 207 | Cool; Questionnaire | −.15 |

Table 5.

Studies with a negative relationship or effect size < .10 for poverty-SR pathway

| Author | Sample | SR classification | r (total) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brown (2013) | Sample from PA Head Start; N = 205 | Questionnaire | .05 |

| Roy (2014a; 2014b); Raver (2013) | Chicago School Readiness Project; N’s range from 391–602 | Cool; Questionnaire | −.07 |

| Choi (2016) | Sample from OK Early Head Start/Head Start; N = 169 | Cool | −.03 |

| Marcovitch (2015) | Community sample; N = 226 | Cool | −.08 |

| Razza (2010) | Fragile Families; N = 1046 | Cool | −.07 |

| Degol (2015) | Community sample; N = 216 | Hot | −.06 |

| Pearce (2016) | UK Millenium Cohort Study; N = 5107 | Questionnaire | −.05 |

Association between exposure to poverty on hot, cool, and questionnaire-based measures of child SR.

Separate rs were then calculated to compare the effect sizes for the associations between poverty and each type of SR (hot, cool, questionnaire-based). When the SR variable used in a study was a composite of both observed and questionnaire measures, it was classified as questionnaire-based. In addition, if there was one sample that tested more than one type of SR in different studies or in the same study, effect sizes for each were included in this analysis. As an example, of the six studies that used the NICHD SECCYD sample and had an effect size included in the original paper, Crook and Evans (2014), Dilworth-Bart, Khurshid, and Vandell (2007), and Blums, Belsky, Grimm, and Chen (2017) all tested associations between poverty and cool SR, as measured by the Tower of Hanoi task (Blums et al. 2017; Crook & Evans 2014) and the Continuous Performance Test (Dilworth-Bart et al. 2007). The aggregated effect size for cool SR was calculated using an average of the rs from these three studies. Two of the studies (Blums et al. 2017; Nievar, Moske, Johnson, & Chen 2014) tested associations with hot SR using a delay task, and the hot SR aggregated effect size was calculated as the average from these two papers.

In comparing the magnitude of the aggregated effect sizes for the three types of SR, all were comparable to one another. For studies that tested the relationship between poverty and cool SR (n = 21), r = −.14; for poverty and hot SR (n = 11), r = −.13; and for poverty and questionnaire-based SR (n = 19), r = −.17. A Fisher’s z test indicated that none of the correlation coefficients were significantly different from one another. Although more studies used cool SR measures than hot, there was little evidence to indicate that the strength of the relationship between poverty and SR was weaker when hot SR measures were used.

Features of the sample and measurement of poverty.

Most studies used income-based measures of poverty. Of the eight studies from six independent samples that used a cumulative risk index that included a measure of poverty (Bocknek, Brophy-Herb, Fitzgerald, Schiffman, & Vogel 2014; Brophy-Herb, Zajicek-Farber, Bocknek, McKelvey, & Stansbury 2013; Chang, Shelleby, Cheong, & Shaw 2012; Conradt et al. 2014; Doan, Fuller-Rowell, & Evans 2012; Lengua, Honorado, & Bush 2007; Mistry, Benner, Biesanz, Clark, & Howes 2010; Wade et al. 2018), only Wade and colleagues used an observed measure of child SR, with the other studies using questionnaires. Using a relatively large Canadian sample, Wade and colleagues (2018) found that a cumulative risk index (including variables such as maternal depression and single parenthood along with low family income) in early infancy was associated with lower children’s cool SR (as measured by tasks that tested inhibitory control—the Bear/Dragon and cognitive flexibility—the Dimensional Change Card Sort) at age 3 (r = −.13).

Fifteen studies (not including duplicate samples) used predominantly low-income samples. The Family Life Project, a longitudinal study of children born in low-income, rural counties in North Carolina and Pennsylvania, was one such sample that was used in four different studies included in the aggregated effect size analysis. Using this sample, researchers consistently found an association between early childhood income (when children were 0−3 years) and SR, also measured in early childhood. The observed SR battery included multiple tasks assessing several aspects of cool SR, including working memory, attention shifting, and inhibitory control (Berry et al. 2014; Gueron-Sela et al. 2018; Sulik et al. 2015; Vernon-Feagans, Willoughby, & Garrett-Peters 2016); teachers also reported on children’s “behavioral regulation” in kindergarten (Vernon-Feagans et al. 2016). To determine whether the magnitude of effect sizes was comparable, an aggregated effect size was calculated for the association between poverty and SR for low-income (n = 15) versus representative samples (n = 22). The magnitude was stronger for representative samples (r = .18 versus r = .13), but not significantly so (z = .14, ns).

Child age.

The majority of studies (n = 27) tested the outcome of SR in early childhood, usually starting at preschool-age (i.e., age 3–4), with just three studies using SR measured in adolescence as a final outcome (Doan, Fuller-Rowell, & Evans 2012; Evans, Gonnella, Marcynyszyn, Gentile, & Salpekar 2005; King, Lengua & Monahan 2013). The study that used the earliest outcome measure for SR, at age 18 months, was the only one of all 37 studies in the analysis for which the effect size was in the opposite of the expected direction (i.e., higher poverty associated with higher SR, r = .13). In this study, Gartstein, Bridgett, Young, Panksepp, and Power (2013) found that income in early infancy was negatively associated with parent-reported SR at 18 months using the effortful control subscale from a measure of early childhood temperament; maternal parenting stress was positively associated with effortful control.

Many studies, however, found significant associations for the association between poverty and child SR when children were as young as 3 and 4 years old (e.g., Lengua et al. 2007; Sektnan, McClelland, Acock, & Morrison 2010; Sturge-Apple et al. 2016). As an example, Thompson and colleagues (2013), Tandon, Thompson, Moran, and Lengua (2015), and Lengua in three different studies (Lengua et al. 2014; Lengua et al. 2015; Lengua, Zalewski, Fisher, & Moran 2013) all used the same economically representative community sample to test associations between age 3 income and both hot and cool measures of child SR assessed four times at nine-month intervals. In all studies, researchers found significant associations between income and both hot and cool SR, with hot SR measured with a gift delay task and cool SR measured using a battery that included verbal inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility tasks. Importantly, Lengua and colleagues (2014) found that the effect of income on both types of SR was primarily explained by parenting variables (e.g., scaffolding, limit-setting).

Effect of poverty on physiological SR.

Very few studies examined direct effects of poverty or poverty-related stressors on children’s parasympathetic nervous system functioning, often assessed using respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA). Baseline RSA is thought to provide an indication of physiological SR while at rest, and higher RSA is usually associated with more optimal health and behavior outcomes (Propper 2012). Children’s RSA is known to be vulnerable to several types of environmental stressors, such as adolescents’ exposure to early life adverse events (Daches et al. 2017). Only one study was found that assessed the longitudinal relation between poverty and/or cumulative risk and RSA. Researchers found that a cumulative risk index (which included poverty) from birth to age 3 was associated with less RSA reactivity and less growth in reactivity from ages 3 to 6 (Conradt et al., 2014). This finding is opposite of what was expected, as greater RSA reactivity is typically associated with negative outcomes. However, by age 6, researchers found that there was a significant, positive association between early cumulative risk and RSA reactivity in the expected direction, indicating that perhaps there is a “latent” effect of early adversity on physiological regulation.

Effect of food insecurity on SR.

Only one study was found that tested the association between child FI and SR longitudinally. Using the ECLS-K dataset, Grineski, Morales, Collins, and Rubio (2018) found evidence for a small, negative association between FI in kindergarten and SR one year later, as measured by teacher report (r = −.07) and observed cool SR (using a working memory test and the Dimensional Change Card Sort test, which tests cognitive flexibility, r = −.10).

Summary of research linking poverty exposure to child SR.

Overall, exposure to poverty and poverty-related risk was associated with lower SR, with several studies indicating that the association between poverty and diminished SR may be detected at as early as age 3 or 4. The majority of the literature focused on cool rather than hot SR as an outcome, but there was no evidence that the association with poverty was stronger for cool SR. More research is needed to understand more about the effect of poverty on physiological SR and the effect of food insecurity on SR in general.

Longitudinal research linking self-regulation to childhood weight

The final pathway in the proposed model focuses on SR as a predictor of child weight. In this model, SR is thought to mediate the effects of poverty on child weight, and thus in the following section SR is discussed specifically as a variable that predicts child weight outcomes.

Longitudinal research on SR to child weight: Measurement and Overview.

Measures of SR in relation to weight tended to resemble those used in studies unrelated to eating or weight. However, there are some domain-specific measures used to measure SR specifically related to food intake. One example is the Eating in the Absence of Hunger (EAH) paradigm. In EAH tasks, children are usually first provided with a standardized meal. When children report that they are full, they begin a “free-access” session in which they are allowed to eat as much as they would like from an assortment of palatable sweet and savory snacks. The amount of snacks that they eat is then recorded, with children who consume fewer calories in the absence of hunger assumed to be better at self-regulating their caloric intake. In addition to the EAH protocol, there are also some questionnaire measures that assess child SR regarding eating behaviors (e.g., Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ); Wardle, Guthrie, Sanderson & Rapoport 2001).

The extent to which domain-specific eating SR tasks are associated with more global measures of SR remains unclear, with some studies finding associations between EAH and traditional SR measures (Tan & Holub 2010) and others not finding evidence of this association (Leung et al. 2014). Interestingly, Hughes and colleagues (2015) found a significant correlation between EAH and a food DoG task in low-income preschoolers in an unexpected direction, with greater SR in the food DoG task associated with more calories consumed in the absence of hunger. They also found that only eating-specific SR tasks or questionnaires (EAH, parent-reported satiety and food responsiveness on the CEBQ) were concurrently associated with BMI, while domain-general hot (food DoG, gift delay) and cool (tapping task, flexible item selection task) SR tasks having no significant relation. In addition, a cross-sectional study found that for preschoolers, eating more in the absence of hunger was associated with greater BMI, while waiting time on a food DoG task was not (Power et al. 2016). Together these studies suggest that domain-specific food SR tasks may measure different aspects of child SR in relation to eating behavior than traditional hot and cool SR tasks.

Results of aggregated effect size analysis for longitudinal associations between SR and weight.

Searching PubMed and PsycINFO with the terms listed above for the poverty→weight pathway yielded 1131 articles. Of those, 33 were found to meet criteria for inclusion in the review. Twelve studies already included effect size information in the paper. For 13 studies, authors were emailed to obtain this information. Of those, six provided effect size information. Seventeen unique samples were represented in the effect size aggregation analysis. Two additional papers that reported a correlation coefficient used a duplicate sample (in both cases, the sample was drawn from the NICHD study). Five other papers were from duplicate samples where the effect size did not appear in the manuscript.

The total average affect size was calculated in the same manner as for the poverty→SR pathway, with the highest of the rs for any one measure of SR (i.e., hot, cool, or questionnaire-based) used to represent the total. The total aggregated affect size for the SR→weight association was r = −.13, with greater SR associated with lower weight. Thirteen out of the 17 unique samples had an effect size of r ≥ .10 (see Tables 6 and 7).

Table 6.

Studies with a negative relationship and effect size ≺ .10 for self-regulation (SR)weight pathway

| Author | Sample | SR classification | r (total) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graziano (2010) | Community sample; N = 57 | Cool; Hot | −.14 |

| Anzman (2009) | Community sample; N = 197 | Questionnaire | −.30 |

| Evans (2012) | Community sample; N = 244 | Hot (food) | −.21 |

| Mallan (2014) | Community sample; N = 37 | Questionnaire (appetite-specific) | −.38 |

| Graziano (2013) | Community sample; N = 195 | Hot | −.19 |

| Francis (2009); Seeyave (2009); Bub (2016) | NICHD; N’s range from 8051061 | Hot (food); Cool; Questionnaire | −.14 |

| Duckworth (2010) | Community sample; N = 105 | Questionnaire/Observed composite | −.22 |

| Tandon (2015) | Community sample; N = 306 | Hot; Cool | −.10 |

| Steinsbekk (2015) | Sample from Norway; N = 687 | Questionnaire (appetite-specific) | −.21 |

| Asta (2016) | Sample from MI Head Start; N = 209 | Eating in the Absence of Hunger task | −.11 |

| Parkinson (2010) | Gateshead Millenium Study (UK); N = 583 | Questionnaire (appetite-specific) | −.15 |

| Carter (2012) | Longitudinal Study of Child Development in Quebec, N = 1566 | Questionnaire (appetite-specific) | −.41 |

Table 7.

Studies with a negative relationship and effect size < .10 for self-regulation (SR)weight pathway

| Author | Sample | SR classification | r (total) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson (2017) | Millenium Cohort Study; UK, N = 10,955 | Questionnaire | .05 |

| Piche (2012) | Longitudinal Study of Child Development in Quebec; N = 966 | Questionnaire | .04 |

| Stautz (2016) | Avon Longitudinal Study (UK); N = 6069 | Cool; Questionnaire | −.02 |

| Fogel (2018) | Growing up in Singapore Towards Healthy Outcomes; N = 158 | Eating in the Absence of Hunger task | −.05 |

| Bergmeier (2014) | Australian Research Council Discovery Grant Study; N = 201 | Questionnaire | .05 |

| Datar (2018) | ECLS-K; N = 7070 | Questionnaire | −.07 |

Type of self-regulation and longitudinal associations with weight.

Again, a correlation coefficient for the association between each type of SR (cool, hot, questionnaire) and later weight was calculated. Of the four studies that tested the relationship between cool SR and child weight, the average r = −.04, with just one study finding an association in which r ≥ .10. Of the studies that evaluated associations between hot SR and child weight, all seven r’s were ≥ 10 and the average effect size was r = −.14. In one study that tested multiple types of SR (hot, cool, and questionnaire-based) within the same large sample (NICHD), researchers used a single SR factor comprised of five indicators (hot, cool, and questionnaire-based, all measured at age 4) and found that higher SR predicted lower BMI at three different ages (8, 11, and 15) (Bub, Robinson, & Curtis 2016). In addition, researchers found that SR accounted for more of the variance in BMI when children were older. However, in considering the bivariate correlations between each SR indicator and BMI averaged across the three ages, the strongest relations were for hot SR (measured with a food DoG task) and the questionnaire measure (parent report of inhibitory control and attention focusing), r = −.10 and r = −.09, respectively, while the association between cool SR (measured with a Stroop and Continuous Performance Test) and average BMI was relatively lower (r = −.03).

A total of 11 studies analyzed questionnaire-based measures of SR in relation to child weight, with an aggregated effect size of r = −.14. Of those, eight used questionnaires that reported on general aspects of child SR (e.g., Children’s Behavior Questionnaire; Rothbart et al., 2001), and three used eating-specific questionnaires. The average effect size for questionnaires that assessed eating-specific behaviors was r = −.25, whereas for questionnaires that assessed SR broadly, r = −.07. All three of the studies that used eating-specific questionnaires used the CEBQ: some, but not all of the eight scales that comprise the CEBQ assess children’s SR of eating (e.g., emotional over-eating, satiety responsiveness).

Of the two studies that used an EAH task to predict later BMI, one study found some evidence for an association (Asta et al. 2016), while the other did not (Fogel et al. 2018). Asta and colleagues (2016), using a predominantly low-income sample, tested EAH twice in very early childhood (21 and 27 months) and BMI when children were 33 months. The association between 33-month BMI and EAH at 27 months was much stronger than for EAH at 21 months. Asta and colleagues note that in their study the number of calories consumed in the absence of hunger increased with age, particularly for sweet foods, supporting some prior research indicating that children’s eating SR declines with age (Johnson & Taylor-Holloway 2006). However, Fogel and colleagues’ (2018) study focused on a group of children in Singapore who were slightly older, with an EAH task at age 4 used to predict age 6 BMI, and did not find an association between EAH and BMI.

Developmental Timing.

In estimating effect sizes by age at which the weight outcome was measured, overall SR (i.e., not separated by SR type) was most strongly related to weight when measured in adolescence (r = −.18, n = 5), versus measuring weight in early (r = −.10, n = 6) and middle childhood (r = −.11, n =6). None of the differences between the magnitudes of the correlation coefficients were statistically significant (z = .09, ns and z = .08, ns, for adolescence versus early childhood and adolescence versus middle childhood, respectively).

Most studies (n = 13) measured SR beginning in early childhood. Six studies measured weight through adolescence and found significant effects for the relation between SR measured in early/middle childhood and adolescent weight. The association between SR measured in early childhood on adolescent weight was established using both observed (Francis & Susman 2009) and questionnaire measures of SR (Anzman & Birch 2009).

Effects of SR-Promoting Interventions on Child Weight.

Three studies were reviewed that used a weight loss intervention that included an SR component and measured SR pre- and post-treatment (see Table 8). One evaluated the effect of a general SR-building intervention as part of an obesity prevention program for low-income preschoolers (Lumeng et al. 2017) and two tested a weight loss intervention for obese children ages 8–13 (Israel, Guile, Baker, & Silverman 1994) and 8–14 (Verbeken, Braet, Goossens, & Van der Oord 2013).

Table 8.

SR-Promoting Weight Intervention Studies

| Author | Sample | Intervention | Intervention effects on SR | Intervention effects on weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumeng (2017) | N=697 Head Start preschoolers | Preschool Obesity Prevention Series (POPS) vs. POPS + Incredible Years Series (IYS) vs. Head Start (HS) only | HS+POPS+IYS group had improvements in teacher-reported SR compared to both other groups (r = .21 for HS+POPS+IYS vs. HS+POPS) | No effect of intervention on obesity at the end of academic year (r = .01) |

| Israel (1994) | N=34 obese children age 9–13 | Standard treatment (ST) vs. Enhanced Child Involvement (ECI), including training in self-management skills | ECI associated with lower parent and teacher-reported SR (average r = −.19) but higher child-reported SR (r = .16) | At 3-year follow-up, ECI associated with lower % of overweight children compared to ST (r = .30) |

| Verbeken (2013) | N=44 obese Dutch children age 8–14 in an inpatient treatment program | Executive Functioning (EF) training vs. care as usual | Better weight loss maintenance in EF-training group 8 weeks post-intervention, but not maintained through 12-week f/u (r = .05 for 12-week f/u) | Improvements in cool SR (Corsi Block Tapping task) associated with EF-training group (r = .20). Increased deficits in working memory and metacognition subscales of teacher-reported BRIEF for the control group while EF-training group remained stable (r = .27) |

An effect size (d) for the effect of each intervention on SR and weight was calculated and then converted to r to be consistent with the effect size measures used for the other associations. The total aggregated effect size for the effect of the interventions (N = 3) on SR was r = .13 in favor of the SR intervention. For two of the three intervention studies (Lumeng et al. 2017; Verbeken et al. 2013), there was some evidence that the intervention promoted children’s SR, as measured by questionnaires. Only Verbeken and colleagues (2013) used an observed SR measure to investigate changes in SR during the intervention period, finding that the intervention was associated with increases in cool SR (r = .20). Israel and colleagues (1994), using parent, teacher, and child report of SR, did not find consistent associations between the intervention, which included training in child self-management and SR, and improvements in child SR; in fact, averaging across parent, teacher, and child reports, greater SR improvements were demonstrated in the comparison group (average r = −.10, ns).

For calculating the aggregated effect size for the effect of the interventions on child weight, if there were multiple follow-up assessments of weight, the final outcome for weight was used. The average r was .12 for the effect of the interventions on child weight compared to the control group, with one study finding an effect on weight and the other two studies having no or minimal effect on weight change. Israel and colleagues (1994) found that their “enhanced child involvement” intervention was associated with a lower proportion of children who were overweight at three years post-treatment compared to the standard treatment group (r = .30). Interestingly, as noted above, Israel and colleagues (1994) did not find any effect of the intervention on SR, suggesting that the effects of the intervention on child weight at follow-up were operating through a mechanism other than improvements to children’s SR. For the other two intervention studies, there was no evidence to suggest a meaningful effect of SR training on weight loss or weight loss maintenance.

Summary.

The aggregated average effect size from SR to child weight was in the “small” range (r = −.13) and comparable to the magnitude of the correlation coefficients for the other two pathways. There was some evidence that hot SR is a stronger predictor of later weight than cool SR, with hot SR more commonly tested. Of the different measures of SR, there was also some evidence that eating-specific questionnaires were more predictive of later weight than domain-specific SR questionnaires, but only three studies used this measure. There was little evidence that SR-focused obesity prevention or intervention programs help reduce child weight, but only three studies were found that tested a child weight intervention and also measured SR.

Discussion

Synthesis of Literature and Presentation of Updated Model

At the outset of this review, it was proposed that child SR might be one explanatory mechanism by which poverty influences children’s weight outcomes. In each of the pathways of interest, effect sizes were in expected direction, albeit in the “small” range, with r = .09 (poverty→weight), r = −.16 (poverty→SR), and r = −.13 (SR→weight).

Although the aggregated effect size for the pathway from poverty to weight was particularly small, it is comparable to the effect sizes that previous systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses have established for other risk factors of child obesity. Examples include the following: maternal smoking during pregnancy and child overweight: OR = 1.5 (equivalent to r = .11) (Oken, Levitan, & Gillman 2008); breast-feeding and child obesity: OR = .78 equivalent to r = .07 (Arenz, Rückerl, Koletzko, & von Kries 2004); and TV viewing and child body fat: r = .07 (Marshall, Biddle, Gorely, Cameron, & Murdey 2004).

For the pathway from poverty to SR, the effect size found in the current review (r = −.16) was identical to one found in a recent meta-analysis on the association between SES and behavioral executive functioning tasks (i.e., observed cool SR) (Lawson, Hook, & Farah 2018). There was minimal overlap of the studies include in both analyses -- of the 25 unique samples in their meta-analysis and the 37 in the effect size analysis in the current review, only four samples overlapped. Lawson, Hook, and Farah’s meta-analysis also included education and occupation-based measures of SES and was not limited to longitudinal studies.

Although to our knowledge no other systematic reviews or meta-analyses have been conducted on the relationship between SR and weight in children, a recent meta-analysis of the association between behavioral task and questionnaire measures of impulsivity and adult BMI also found evidence for a small but significant effect size (r = .07) (Emery & Levine 2017).

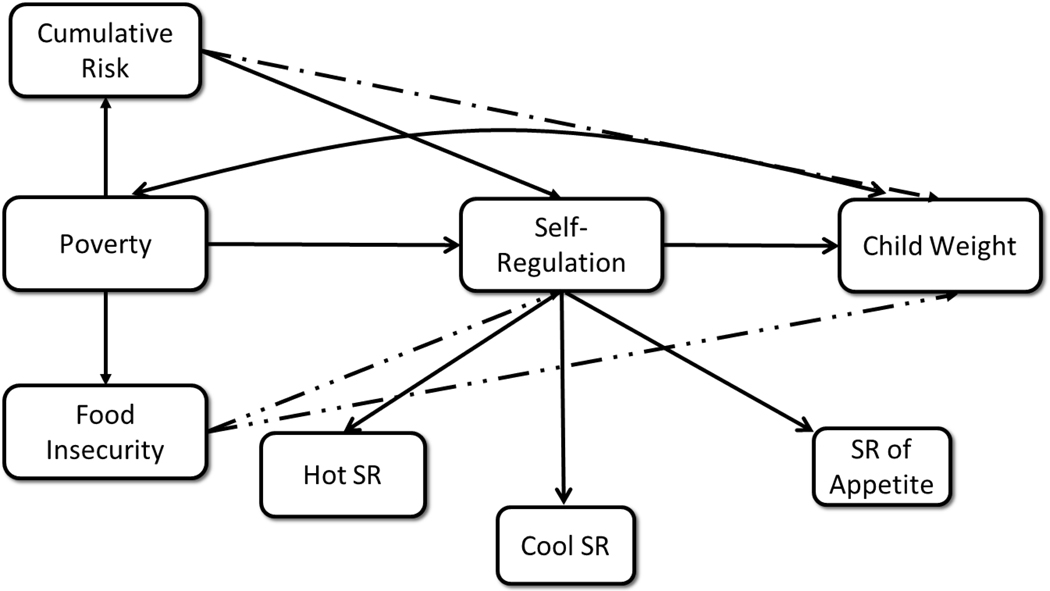

Based on the literature reviewed, Figure 1 represents a theoretical model depicting relationships among the variables of interest. The model includes both food insecurity and cumulative risk as variables related to poverty that may influence child weight. The dotted lines from FI to SR and child weight and from cumulative risk to child weight reflect that there is not yet enough evidence to suggest an association for these pathways and the need for more research examining these paths.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of associations between poverty, SR, and child weight. * Dotted lines indicate that there is not yet enough evidence to suggest an association for these pathways and the need for more research examining these paths

Limitations of the Current Literature

Poverty to Weight.

The majority of studies reviewed in this pathway measured exposure to poverty during early childhood. Although there are compelling reasons to suspect that exposure to poverty in early childhood may be particularly harmful, such as early adversity impacting reactivity to stress (Shonkoff et al. 2012), it remains necessary to specifically test this assumption by comparing children’s exposure to poverty at various points in development in relation to later weight. It would be important to isolate the effects of poverty exposure during different developmental stages on child weight to determine the extent to which early poverty has unique effects on child BMI. Alternatively, more prospectively ascertained data are also needed to examine the cumulative effects of experiencing poverty across multiple developmental periods (e.g., early and middle childhood vs. early childhood through adolescence).

Poverty to SR.

A major limitation of the poverty to SR literature was that only three studies tested SR in adolescence. Moreover, few studies spanned multiple developmental periods. Therefore, it remains unclear whether early exposure to poverty continues to predict SR later in childhood and adolescence.

Prior research suggests that early exposure to poverty may be particularly detrimental for outcomes much later in development such as academic achievement and employment (Duncan & Magnuson 2013), but there is not yet enough evidence to indicate that this is also the case for SR.

Only one study evaluated the longitudinal relationship between FI and SR, using both teacher report and cool SR measures (Grineski et al. 2018). For developing a better understanding of the relationship between poverty and weight outcomes, it would be particularly interesting and important to test the relationship between FI and SR as measured by DoG tasks. When children are food insecure, they may not know exactly when their next meal might be, which could affect whether they are willing to wait for a bigger reward. Additionally, no studies were found that tested the longitudinal relationship between poverty or FI and eating-specific child SR, although a cross-sectional study found that children living in homeless shelters reported overeating as a coping strategy for FI (C. Smith & Richards 2008).

SR to Weight.

Surprisingly little research has tested the extent to which eating-specific SR measures, particularly EAH, predict later child weight or weight gain over time, with only one observational EAH study evaluating this association in early to middle childhood and three studies using parent report. It would be helpful to learn more about relationships between different types of SR, including EAH and hot/cool observed measures, and child weight longitudinally across developmental stages.

Self-Regulation across Literatures

A challenge of the proposed model that future research should address is the extent to which each type of SR (hot, cool, appetite-specific) is a viable candidate to mediate the association between poverty and weight. The current review revealed that although there is some overlap in how SR is conceptualized in relation to the poverty to SR and the SR to weight pathways, there are also important differences. In the poverty to SR pathway, more of the literature has focused on cool SR. The relatively greater emphasis on cool SR in most studies may be because of a greater emphasis in the literature of identifying possible mechanisms for the relationship between poverty exposure and academic achievement. As an example, some research suggests that cool SR, rather than hot, is more strongly associated with academic performance (Willoughby et al. 2011). In line with this explanation, for many of the studies that used exclusively cool SR measures, authors emphasized the importance of SR in the context of academic achievement (McClelland & Wanless 2012; Nesbitt, Baker-Ward, & Willoughby 2013; Thompson, Lengua, Zalewski, & Moran 2013; Wanless, McClelland, Tominey, & Acock 2011).