Abstract

Objective

To evaluate viral loads at different stages of disease progression in patients infected with the 2019 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) during the first four months of the epidemic in Zhejiang province, China.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

A designated hospital for patients with covid-19 in Zhejiang province, China.

Participants

96 consecutively admitted patients with laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection: 22 with mild disease and 74 with severe disease. Data were collected from 19 January 2020 to 20 March 2020.

Main outcome measures

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) viral load measured in respiratory, stool, serum, and urine samples. Cycle threshold values, a measure of nucleic acid concentration, were plotted onto the standard curve constructed on the basis of the standard product. Epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory characteristics and treatment and outcomes data were obtained through data collection forms from electronic medical records, and the relation between clinical data and disease severity was analysed.

Results

3497 respiratory, stool, serum, and urine samples were collected from patients after admission and evaluated for SARS-CoV-2 RNA viral load. Infection was confirmed in all patients by testing sputum and saliva samples. RNA was detected in the stool of 55 (59%) patients and in the serum of 39 (41%) patients. The urine sample from one patient was positive for SARS-CoV-2. The median duration of virus in stool (22 days, interquartile range 17-31 days) was significantly longer than in respiratory (18 days, 13-29 days; P=0.02) and serum samples (16 days, 11-21 days; P<0.001). The median duration of virus in the respiratory samples of patients with severe disease (21 days, 14-30 days) was significantly longer than in patients with mild disease (14 days, 10-21 days; P=0.04). In the mild group, the viral loads peaked in respiratory samples in the second week from disease onset, whereas viral load continued to be high during the third week in the severe group. Virus duration was longer in patients older than 60 years and in male patients.

Conclusion

The duration of SARS-CoV-2 is significantly longer in stool samples than in respiratory and serum samples, highlighting the need to strengthen the management of stool samples in the prevention and control of the epidemic, and the virus persists longer with higher load and peaks later in the respiratory tissue of patients with severe disease.

Introduction

A novel human coronavirus first detected during an unexplained cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China in December 2019 has spread globally.1 2 As of 22 March 2020, the newly emerged severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (genus Betacoronavirus, family Coronaviridae) has been reported in 190 countries with more than 300 000 confirmed cases and 14 510 deaths.3 A predominant number of cases has occurred in China,4 with early clinical characterisation showing that 13.8% of those infected developed severe disease, and death occurred in 2.3% of the cases.

Viral load measurements from tissue samples are indicative of active virus replication and are routinely used to monitor severe viral respiratory tract infections, including clinical progression, response to treatment, cure, and relapse.5 6 7 One study described changes in viral loads in samples from the upper respiratory tract of 18 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19, an infectious disease caused by SARS-CoV-2), showing that the viral loads were equally high among asymptomatic patients and those with symptoms.8 However, the viral load dynamics in lower respiratory tract and other tissue samples and the relation between viral load and disease severity is unknown—information that are important for the formulation of disease control strategies and clinical treatment.

We systematically estimated the viral loads in more than 3000 samples collected from 96 patients after admission who were infected with SARS-CoV-2, and analysed the temporal change in viral loads and the correlation between viral loads in different sample types and disease severity.

Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective cohort study of patients with laboratory confirmed covid-19 admitted consecutively to the First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University from 19 January 2020 to 15 February 2020. This major general hospital has 3000 beds and serves as a designated hospital for patients with covid-19 in Zhejiang province.

Sample collection and laboratory confirmation

After admission, respiratory, serum, stool, and urine samples were collected daily whenever possible to determine the amount of SARS-CoV-2 ribonucleic acid (RNA) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. Sputum samples were collected from the respiratory tract of patients with sputum, and saliva after deep cough was collected from patients without sputum.9 Blood samples were collected in a special whole blood collection tube, and urine and stool samples were collected in a special sterile container. All medical staff were equipped with personal protection equipment for biosafety level 3 during sampling, including solid front wraparound gowns, goggles, and N95 respirators.

Viral RNA was extracted using the MagNA Pure 96 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using a China Food and Drug Administration approved commercial kit specific for SARS-CoV-2 detection (BoJie, Shanghai, China). The detection limit of the ORFab1 qRT-PCR assays was about 1000 copies per millilitre. Samples with cycle threshold (Ct) values of ≤38.0 were considered positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Samples with Ct values >38.0 were repeated, and samples with repeated Ct values of >38.0 and samples with undetectable Ct values were considered negative. Viral load was calculated by plotting Ct values onto the standard curve constructed based on the standard product.

Data collection

The research team of the First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University analysed the medical records of patients. Epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory characteristics and treatment and outcomes data were obtained through data collection forms from hospital electronic medical records. A trained team of doctors reviewed the data. The clinical data included personal characteristics, comorbidities, date of symptom onset, symptoms and signs, timing of antiviral treatment, and progression and resolution of clinical illness. Comorbidities documented included diabetes mellitus, heart disease, chronic lung disease, renal failure, liver disease, HIV infection, cancer, and receipt of immunosuppressive treatment, including corticosteroids. We considered that the symptoms started when any of fever, cough, chills, dizziness, headache, and fatigue appeared.

The severity of illness was evaluated according to the sixth edition of the Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 issued by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China.10 Mild cases include non-pneumonia or mild pneumonia. Severe disease refers to dyspnoea, respiratory rate ≥30/min, blood oxygen saturation ≤93%, partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio <300, or lung infiltrates >50% within 24 to 48 hours. Patients who test negative for SARS-CoV-2 for two consecutive days in respiratory samples are considered to be clear of infection.

Statistical analysis

For most variables, we calculated descriptive statistics, such as medians with interquartile ranges (for data with skewed distribution) and proportions (percentages). Statistical comparisons between the mild and severe groups were evaluated by t test, analysis of variance, Mann-Whitney U tests, and Kruskal-Wallis tests when appropriate. To explore the variation of viral load across the days since symptom onset, we calculated the median of viral load each day, followed by fitting smooth lines using a loess method.11 For this analysis, we only included patients with viral loads monitored for more than five days in respiratory and stool samples. Statistical analyses were performed using the R software package, v3.6.2. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Patient and public involvement

This was a retrospective case series study and no patients were directly involved in the study design, setting the research questions, or the outcome measures. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results.

Results

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of 96 patients with confirmed covid-19: 22 with mild disease and 74 with severe disease. The median age was 55 years (interquartile range 44.3-64.8). Of the patients infected in Wuhan, a significantly higher proportion were in the severe group (35%) than in the mild group (9%). Hypertension (36%) and diabetes mellitus (11%) were the most common underlying disease. Most of the patients developed fever (89%) and cough (56%). Overall, 78 (81%) patients received glucocorticoids and 33 (34%) antibiotic treatment. All patients received antiviral treatment comprising interferon α inhalation, lopinavir-ritonavir combination, arbidol, favipiravir, and darunavir-cobicistat combination. Among them, 63 (66%) started antiviral treatment within five days from illness onset and 29 (30%) more than five days after illness onset. Thirty (41%) patients with severe disease were admitted to the intensive care unit. By 20 March, all patients tested negative for SARS-CoV-2, nine (9% of all patients) patients with severe disease were still in hospital, and no deaths had occurred. Supplementary figure S1 shows the outcome among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, and supplementary table S1 the laboratory findings.

Table 1.

Personal and clinical characteristics of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection by severity of disease

| Characteristics | Total (n=96) | Disease severity | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild (n=22) | Severe (n=74) | |||

| Median (interquartile range) age (years) | 55 (44.3-64.8) | 47.5 (36.8-56.3) | 57 (47.5-66) | 0.01 |

| Men | 58 (60) | 9 (41) | 49 (66) | 0.03 |

| Infected in Wuhan | 28 (29) | 2 (9) | 26 (35) | 0.01 |

| Underlying diseases: | ||||

| Hypertension | 35 (36) | 4 (18) | 31 (42) | 0.04 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (11) | 1 (5) | 10 (14) | 0.44 |

| Heart disease | 7 (7) | 0 (0) | 7 (9) | 0.30 |

| Lung disease | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (5) | 0.57 |

| Liver disease | 3 (3) | 1 (5) | 2 (3) | 0.55 |

| Renal disease | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1.00 |

| Malignancy | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1.00 |

| Immune compromise | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1.00 |

| Symptoms: | ||||

| Fever | 85 (89) | 17 (77) | 68 (92) | 0.13 |

| Cough | 54 (56) | 12 (55) | 42 (57) | 0.85 |

| Sputum | 26 (27) | 7 (32) | 19 (26) | 0.59 |

| Chest distress | 12 (13) | 2 (9) | 10 (14) | 0.85 |

| Dizziness | 7 (7) | 0 (0) | 7 (9) | 0.30 |

| Headache | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (5) | 0.57 |

| Nausea | 5 (5) | 2 (9) | 3 (4) | 0.32 |

| Vomiting | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 1.00 |

| Diarrhoea | 10 (10) | 0 (0) | 10 (14) | 0.15 |

| Myalgia | 19 (20) | 6 (27) | 13 (18) | 0.49 |

| Fatigue | 9 (9) | 1 (5) | 8 (11) | 0.64 |

| Treatment: | ||||

| Gammaglobulin | 53 (55) | 4 (18) | 49 (66) | <0.001 |

| Glucocorticoids | 78 (81) | 9 (41) | 69 (93) | <0.001 |

| Antibiotics | 33 (34) | 1 (5) | 32 (43) | 0.001 |

| Antivirals | 96 (100) | 22 (100) | 74 (100) | NC |

| Time from illness onset to antiviral treatment (days): | ||||

| ≤5 | 63 (66) | 14 (64) | 49 (66) | 0.82 |

| >5 | 29 (30) | 8 (36) | 21 (28) | 0.58 |

| Disease severity/support: | ||||

| Bilateral pulmonary infiltrates | 80 (83) | 12 (55) | 68 (92) | <0.001 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 10 (10) | 0 (0) | 10 (14) | 0.15 |

| ECMO | 5 (5) | 0 (0) | 5 (7) | 0.59 |

| Intensive care unit admission | 30 (31) | 0 (0) | 30 (41) | <0.001 |

ECMO=extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; NC=not calculable.

SARS-CoV-2 detection rates during disease progression and between sample types

A total of 1846 respiratory samples (668 sputum and 1178 saliva) were collected (average 18 samples per patient (range 3-40 samples)); 842 stool samples (7 samples per patient (1-32 samples)); 629 serum samples (7 samples per patient (1-20 samples)), and 180 urine samples (1 sample for each patient (1-6 samples)). Supplementary figure S2 shows the daily collection of different sample types.

SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed in all 96 patients by testing respiratory samples. Of these patients, viral nucleic acid was detected in the stool samples of 59% and serum samples of 41%. Rates of SARS-CoV-2 detection in the respiratory samples gradually decreased from 95% in the first week of symptom onset to 54% in he fourth week, with subsequent respiratory samples showing negative results, whereas the positive rate in stool samples and serum samples gradually increased from the first week and then decreased from the third week. In addition, the rate of detection in serum samples was higher in patients with severe disease than in patients with mild disease (45% v 27%), but the difference was not significant. The detection rate in stool did not differ between patients with mild disease and patients with severe disease. Only one urine sample collected from a critically ill patient on day 10 was positive for SARS-CoV-2 (table 2).

Table 2.

Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in patients with mild or severe disease at different stages after symptom onset in different sample types. Values are numbers affected/number tested (%) unless stated otherwise

| Sample types | After admission | Weeks since onset of symptoms | P values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| All patients: | ||||||

| Respiratory | 96/96 (100) | 42/44 (95) | 74/90 (82) | 64/89 (72) | 31/57 (54) | <0.001 |

| Stool | 55/93 (59) | 9/23 (39) | 28/59 (47) | 32/71 (45) | 20/57 (35) | 0.54 |

| Serum | 39/95 (41) | 5/36 (14) | 20/85 (23) | 19/85 (22) | 5/55 (9) | 0.12 |

| Urine | 1/67 (1) | 0/15 (0) | 1/53 (2) | 0/21 (0) | 0/19 (0) | NC |

| Mild disease: | ||||||

| Respiratory | 22/22 (100) | 11/12 (92) | 15/21 (71) | 9/19 (47) | 4/9 (44) | 0.04 |

| Stool | 13/22 (59) | 2/7 (29) | 8/16 (50) | 10/17 (59) | 5/9 (56) | 0.62 |

| Serum | 6/22 (27) | 0/9 (0) | 3/19 (16) | 2/17 (12) | 0/8 (0) | 0.67 |

| Urine | 0/19 (0) | 0/3 (0) | 0/15 (0) | 0/7 (0) | 0/3 (0) | NC |

| Severe disease: | ||||||

| Respiratory | 74/74 (100) | 31/32 (97) | 59/69 (86) | 55/70 (79) | 27/48 (56) | <0.001 |

| Stool | 42/71 (59) | 7/16 (44) | 20/43 (47) | 22/54 (41) | 15/48 (31) | 0.49 |

| Serum | 33/73 (45) | 5/27 (19) | 17/66 (26) | 17/68 (25) | 5/47 (11) | 0.20 |

| Urine | 1/48 (2) | 0/12 (0) | 1/38 (3) | 0/14 (0) | 0/16 (0) | NC |

NC=not calculable.

Correlation between viral duration in different sample types and disease severity

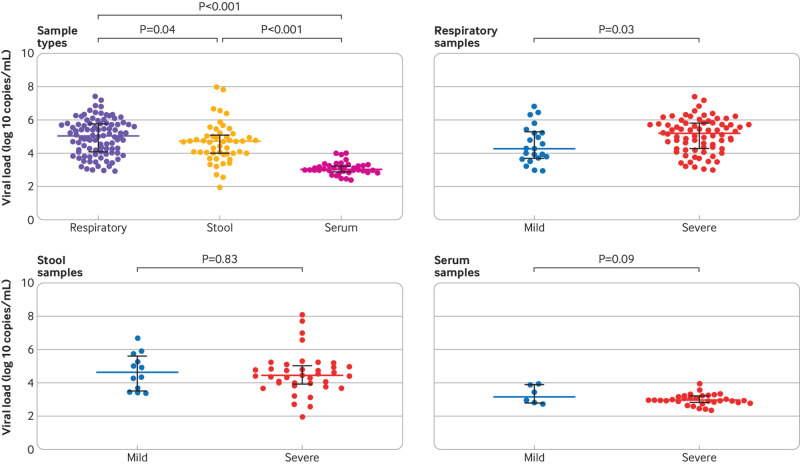

The median duration of virus in stool samples (22 days, interquartile range 17-31 days) was significantly longer than in respiratory (18 days, 13-29 days; P=0.02) and serum samples (16 days, 11-21 days; P<0.001) (fig 1). In the respiratory samples, the median duration of virus in patients with severe disease (21 days, 14-30 days) was significantly longer than in patients with mild disease (14 days, 10-21 days; P=0.04) (fig 1), whereas no significant difference was observed in the duration of virus between stool and serum samples among patients with different disease severities (fig 1). Supplementary figures S3-S5 show the duration of virus in different sample types in each patient.

Fig 1.

Duration of detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by sample types and disease severity. Coloured bars represent medians and black bars represent interquartile ranges

Correlation between viral load in different sample types and disease severity

Viral load differed significantly by sample type, with respiratory samples showing the highest, followed by stool samples, and serum samples showing the lowest (fig 2). In respiratory samples, patients with severe disease had significantly higher viral loads than patients with mild disease (fig 2). Viral loads in stool and serum samples showed no significant difference between patients with mild disease and patients with severe disease (fig 2).

Fig 2.

Comparison of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral load by sample types and disease severity. Coloured bars represent medians and black bars represent interquartile ranges

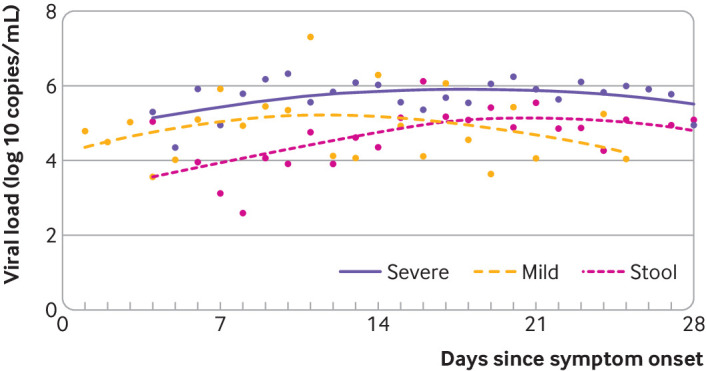

Using a loess regression analysis, we found that in the mild group, the viral load in respiratory samples was greater during the initial stages of the disease, reached a peak in the second week from disease onset, and was followed by lower loads (fig 3). In the severe group, however, the viral load in respiratory samples continued to be high during the third and fourth weeks after disease onset (fig 3). The viral load of stool samples was highest during the third and fourth weeks after disease onset (fig 3).

Fig 3.

Smooth lines were fitted using loess method to explore the variation of viral load of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) across the days since symptoms onset in respiratory samples from patients with mild and severe disease and in stool samples

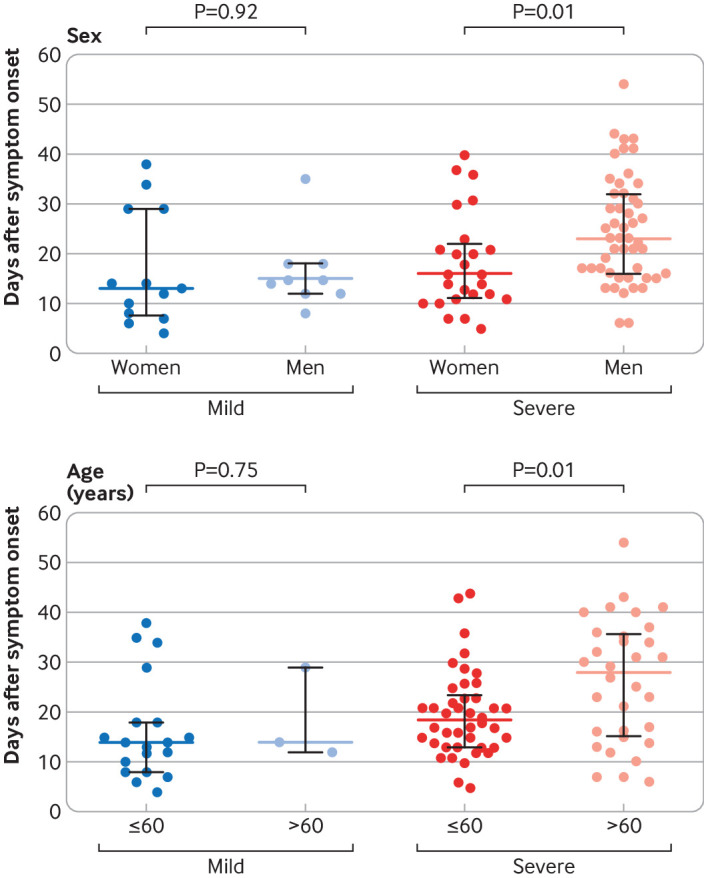

Factors associated with duration of virus and viral load

We found that types and timeliness of antiviral treatments had no overall effect on the duration of the virus and viral load. In the severe group, the duration of the virus was significantly higher in patients treated with glucocorticoids continuously for more than 10 days than in patients treated with glucocorticoids continuously for less than 10 days, whereas different treatments had no effect on viral load (supplementary table S2). When patients with severe disease were stratified, the duration of the virus was significantly longer in men than in women, and significantly longer in patients older than 60 years than younger (fig 4).

Fig 4.

Association between sex and age and duration of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. Coloured bars represent medians and black bars represent interquartile ranges

Discussion

We have systematically described the clinical characteristics of 96 patients with covid-19 and described the dynamic changes of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) loads and disease progression in 3497 samples of multiple types, revealing the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 replication and clearance by host defence mechanisms. The median duration of virus in respiratory samples was 18 days, which was consistent with the median duration of 20 days for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS).12 Peak viral shedding in respiratory specimens of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) occurred after about 10 to 12 days from symptom onset,13 14 which is similar to the peak observed for SARS-CoV-2 in our study. Consistent with earlier reports of SARS-CoV-2,15 we found differences in the viral load in patients with different disease severities, those with severe disease showing a significantly higher viral load than those with mild disease, which suggests that viral load can be used to assess prognosis.

Studies have found that the peak load of SARS-CoV-2 in upper respiratory tract specimens was during the early stages of the disease8 16; however, we found that the duration of virus shedding in lower respiratory tract samples was longer, and peak viral shedding occurred after about two weeks from symptom onset. These findings are important for effective control and prevention of the epidemic as it suggests strict management of the whole disease process in patients with SARS-CoV-2. In this study, we also found that the viral load in patients with severe disease was significantly higher than in patients with mild disease, suggesting that high viral load might be a risk factor for severe disease.

Active replication of SARS in the gut has been shown through live virus isolation.17 During 2003, the prevalence of SARS RNA in stool samples was so high that testing of stool was proposed as a reliable and sensitive way to routinely diagnose the disease,18 19 whereas MERS RNA was found in only 15% of stool samples, with a low RNA concentration.20 In this study, we detected SARS-CoV-2 in the stool samples from 59% of patients and found that the duration of virus was longer and viral load peaked later in stool samples compared with respiratory samples. Based on this study, we think the role of faecal excretion in the spread of SARS-CoV-2 cannot be ignored; however, the importance of high detection in stool samples in the prevention and control of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic requires comprehensive and careful evaluation. We rarely found SARS-CoV-2 RNA in urine samples in this study, although viral RNA detection rates of up to 50% have been found in the urine of patients with SARS.18 19

A clear difference between SARS and SARS-CoV-2 was in the detection of viral RNA in serum. Evidence has been found of SARS virus replicating in circulating lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells, albeit at low levels.21 22 23 In some studies, up to 79% of serum samples were found to contain SARS RNA during the first week of illness, and around 50% during the second week.24 25 26 The rates were similar in MERS.20 In this study, we found that the detection rate of SARS-CoV-2 in serum was only 41%.

At present, the therapeutic effect of glucocorticoids and antiviral drugs in patients with SARS-CoV-2 is unclear.27 28 We found that the duration of treatment with glucocorticoids was positively correlated with viral duration in patients with severe disease. As we did not analysis the type and dose of antiviral drugs and glucocorticoids, however, we cannot evaluate the effect of antiviral drugs and glucocorticoids. Monitoring the effectiveness of antiviral drugs and glucocorticoids needs to be validated by multicentre randomised studies.

A sex dependent increase in disease severity after infection with pathogenic coronavirus was reported for both SARS and MERS,29 30 and this was also found for SARS-CoV-2.31 In this study, we found that the duration of virus was significantly longer in men than in women. Our results shed light on the causes of disease severity in men in terms of the duration of the virus. In addition to differences in immune status between men and women, it has also been reported to be related to differences in hormone levels.32 In this study, we also found a correlation between age and duration of virus, which partly explains the high rate of severe illness in patients older than 60 years. This is partly because of immunosenescence.33 Another reason is that older people have higher levels of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in their alveoli,34 which is thought to be a receptor for novel coronaviruses.

Limitations of this study

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, this study is a single centre cohort study, and the sample size was insufficient to compare treatment effects in different subgroups, which could lead to an unbalanced distribution of confounders when evaluating viral shedding and viral load. Secondly, viral load is influenced by many factors. The quality of collected samples directly affects the viral load, so the study of viral load only partly reflects the amount of virus in the body. Thirdly, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) cannot distinguish between viable and non-viable virus and does not reflect the replication level of the virus in different tissue. However, PCR has higher sensitivity, is easy to perform, and is widely used in the detection of viral load.35 In addition, only collecting samples from patients who remain in hospital could overinflate estimates of viral load and duration at a later time point. Finally, since accurate diagnosis was not available during the early stages of the epidemic, stool and urine samples of the earliest infected patients were not collected until early February, hence we recruited patients with positive respiratory samples and could not evaluate patients with negative respiratory samples against other sample types.

Conclusion

The duration of SARS-CoV-2 is significantly longer in stool samples than in respiratory and serum samples, highlighting the need to strengthen the management of stool samples in the prevention and control of the epidemic, especially for patients in the later stages of the disease. Compared with patients with mild disease, those with severe disease showed longer duration of SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory samples, higher viral load, and a later shedding peak. These findings suggest that reducing viral loads through clinical means and strengthening management during each stage of severe disease should help to prevent the spread of the virus.

What is already known on this topic

As of 9 April 2020, more than 1.5 million people globally have been affected by covid-19, and the numbers continue to increase rapidly

SARS-CoV-2 viral loads have been reported from respiratory, stool, serum, and urine samples in a small number of patients; however, changes in viral load during disease progression of different severities is not known

What this study adds

The duration of SARS-CoV-2 is significantly longer in stool samples than in respiratory and serum samples, highlighting the need to strengthen the management of stool samples in the prevention and control of the epidemic

The virus persists longer with higher load and peaks later in the respiratory tissue of patients with severe disease

To prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2 it is therefore necessary to carry out strict management during each stage of severe disease

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of other clinical and technical staff of the First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University; Lanjuan Li (State Key Laboratory for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases) for guidance in the study design; Vijaykrishna Dhanasekaran (Monash University, Australia) for comments on the manuscript; and Jie Wu (State Key Laboratory for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases) for data analysis.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplementary information: tables S1 and S2 and figures S1-S5

Contributors: TL and YC contributed equally to this paper and are joint corresponding authors. SZ, JF, FY, and BF are joint first authors. The corresponding and first authors conceived and designed the study. All authors selected the articles and extracted data. TL and YC were co-principal investigators. They designed and supervised the study and wrote the grant application (assisted by SZ). KX, XL, GW, JZ, QF, HC, YQ, and JS had roles in recruitment, data collection, and clinical management. SZ, JF, FY, BF, BL, QZ, GX, SL, RW, XY, WC, QW, DZ, YL, RG, ZM, SL, YX, YG, JZ, and HY did clinical laboratory testing and analysis. SZ, FY, BF, YC, and TL drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final version. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. TL and YC are the guarantors.

Funding: This work was supported by the China National Mega-Projects for Infectious Diseases (grant Nos 2017ZX10103008 and 2018ZX10101001) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant Nos 81672014 and 81702079). The research was designed, conducted, analysed, and interpreted by the authors entirely independently of the funding sources.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: support from the China National Mega-Projects for Infectious Diseases and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (2020IIT A0107).

Patient consent: Obtained.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

The lead authors and manuscript’s guarantors affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: No study participants were involved in the preparation of this article. The results of the article will be summarised in media press releases from the Zhejiang University and presented at relevant conferences.

References

- 1. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020;382:727-33. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1199-207. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World health organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak situation. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Accessed 22 March 2020.

- 4. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020; published online 24 February. 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rainer TH, Lee N, Ip M, et al. Features discriminating SARS from other severe viral respiratory tract infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2007;26:121-9. 10.1007/s10096-006-0246-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1814-20. 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Memish ZA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Makhdoom HQ, et al. Respiratory tract samples, viral load, and genome fraction yield in patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. J Infect Dis 2014;210:1590-4. 10.1093/infdis/jiu292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in Upper Respiratory Specimens of Infected Patients. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1177-9. 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. To KK, Tsang OT, Chik-Yan Yip C, et al. Consistent detection of 2019 novel coronavirus in saliva. Clin Infect Dis 2020; published online 12 February. 10.1093/cid/ciaa149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 (the sixth edition). www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/8334a8326dd94d329df351d7da8aefc2.shtml. Accessed 19 February 2020.

- 11. Goh EH, Jiang L, Hsu JP, et al. Epidemiology and Relative Severity of Influenza Subtypes in Singapore in the Post-Pandemic Period from 2009 to 2010. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65:1905-13. 10.1093/cid/cix694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guery B, Poissy J, el Mansouf L, et al. MERS-CoV study group Clinical features and viral diagnosis of two cases of infection with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus: a report of nosocomial transmission. Lancet 2013;381:2265-72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60982-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hung IF, Lau SK, Woo PC, Yuen KY. Viral loads in clinical specimens and SARS manifestations. Hong Kong Med J 2009;15(Suppl 9):20-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cheng PK, Wong DA, Tong LK, et al. Viral shedding patterns of coronavirus in patients with probable severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2004;363:1699-700. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16255-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu Y, Yang Y, Zhang C, et al. Clinical and biochemical indexes from 2019-nCoV infected patients linked to viral loads and lung injury. Sci China Life Sci 2020;63:364-74. 10.1007/s11427-020-1643-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He X, Lau EH, Wu P, et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. medRxiv 2020.20036707. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17. Leung WK, To KF, Chan PK, et al. Enteric involvement of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus infection. Gastroenterology 2003;125:1011-7. 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Poon LL, Guan Y, Nicholls JM, Yuen KY, Peiris JS. The aetiology, origins, and diagnosis of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis 2004;4:663-71. 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01172-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peiris JS, Chu CM, Cheng VC, et al. HKU/UCH SARS Study Group Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet 2003;361:1767-72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13412-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Corman VM, Albarrak AM, Omrani AS, et al. Viral Shedding and Antibody Response in 37 Patients With Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection. Clin Infect Dis 2016;62:477-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gu J, Gong E, Zhang B, et al. Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J Exp Med 2005;202:415-24. 10.1084/jem.20050828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Law HK, Cheung CY, Ng HY, et al. Chemokine up-regulation in SARS-coronavirus-infected, monocyte-derived human dendritic cells. Blood 2005;106:2366-74. 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li L, Wo J, Shao J, et al. SARS-coronavirus replicates in mononuclear cells of peripheral blood (PBMCs) from SARS patients. J Clin Virol 2003;28:239-44. 10.1016/S1386-6532(03)00195-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grant PR, Garson JA, Tedder RS, Chan PK, Tam JS, Sung JJ. Detection of SARS coronavirus in plasma by real-time RT-PCR. N Engl J Med 2003;349:2468-9. 10.1056/NEJM200312183492522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ng EK, Hui DS, Chan KC, et al. Quantitative analysis and prognostic implication of SARS coronavirus RNA in the plasma and serum of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Chem 2003;49:1976-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang WK, Fang CT, Chen HL, et al. Members of the SARS Research Group of National Taiwan University College of Medicine-National Taiwan University Hospital Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus RNA in plasma during the course of infection. J Clin Microbiol 2005;43:962-5. 10.1128/JCM.43.2.962-965.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Russell CD, Millar JE, Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet 2020;395:473-5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30317-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A Trial of Lopinavir-Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; published online 18 March. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Karlberg J, Chong DS, Lai WY. Do men have a higher case fatality rate of severe acute respiratory syndrome than women do? Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:229-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alghamdi IG, Hussain II, Almalki SS, Alghamdi MS, Alghamdi MM, El-Sheemy MA. The pattern of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Saudi Arabia: a descriptive epidemiological analysis of data from the Saudi Ministry of Health. Int J Gen Med 2014;7:417-23. 10.2147/IJGM.S67061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team [The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China]. [In Chinese.] Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2020;41:145-51. 32064853 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Channappanavar R, Fett C, Mack M, Ten Eyck PP, Meyerholz DK, Perlman S. Sex-Based Differences in Susceptibility to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection. J Immunol 2017;198:4046-53. 10.4049/jimmunol.1601896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pera A, Campos C, López N, et al. Immunosenescence: Implications for response to infection and vaccination in older people. Maturitas 2015;82:50-5. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen Y, Shan K, Qian W. Asians Do Not Exhibit Elevated Expression or Unique Genetic Polymorphisms for ACE2, the Cell-Entry Receptor of SARS-CoV-2. Preprints 2020;2020020258. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet 2020;395:514-23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information: tables S1 and S2 and figures S1-S5