Abstract

Lipedema is a chronic, progressive disease of adipose tissue with lack of consistent diagnostic criteria. The aim of this study was a thorough comparative characterization of extracellular microRNAs (miRNAs) from the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of healthy and lipedema adipose tissue. For this, we analyzed 187 extracellular miRNAs in concentrated conditioned medium (cCM) and specifically in small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) enriched thereof by size exclusion chromatography. No significant difference in median particle size and concentration was observed between sEV fractions in healthy and lipedema. We found the majority of miRNAs located predominantly in cCM compared to sEV enriched fraction. Surprisingly, hierarchical clustering of the most variant miRNAs showed that only sEVmiRNA profiles – but not cCMmiRNAs – were impacted by lipedema. Seven sEVmiRNAs (miR–16-5p, miR-29a-3p, miR-24-3p, miR-454-p, miR–144-5p, miR-130a-3p, let-7c-5p) were differently regulated in lipedema and healthy individuals, whereas only one cCMmiRNA (miR-188-5p) was significantly downregulated in lipedema. Comparing SVF from healthy and lipedema patients, we identified sEVs as the lipedema relevant miRNA fraction. This study contributes to identify the potential role of SVF secreted miRNAs in lipedema.

Subject terms: Mechanisms of disease, miRNAs, Biomarkers, Diseases, Biomarkers

Introduction

Lipedema is a chronic, progressive disease characterized by bilateral, symmetrical, disproportional deposition of adipose tissue in the extremities and buttocks1. Patients suffer from pain, reduced joint mobility, hematoma, edema and psychological impacts2. It was first described in 1940 as a connective tissue disorder, characterized by fluid being collected in the interstitium instead of entering into lymphatics3. This excess fluid in the interstitium potentially leads to growth of adipose tissue and hypoxia, which in turn might enhance angiogenesis of pathologic vessels4,5. The area of lymphatic vessels and the number of blood vessels were found increased in non-obese lipedema patients compared to controls6. Examination of adipose tissue from lipedema patients demonstrated hypertrophic adipocytes, crown-like structures and increased number of macrophages6–8.

Besides functioning as an energy storage, white adipose tissue (WAT) responds differentially to physiological and pathological metabolic changes by secreting a large diversity of proteins, hormones, lipids, non-coding ribonucleic acids (RNAs) – including microRNAs (miRNAs) – and extracellular vesicles (EVs)9,10. Small EVs (sEVs) are a fraction of 70–150 nm sized, membrane-enclosed particles, which contain cell-type specific proteins, enzymes, growth factors, cytokines, lipids, as well as coding and non-coding RNAs. It has been repeatedly reported, that WAT-derived vesicular miRNAs are involved in metabolic regulations11,12 and adipose tissue is considered a significant source of circulating sEV-miRNAs11. By acting in an autocrine, paracrine as well as systemic manner, these factors can contribute to metabolic abnormalities, modulation of osteogenic differentiation, inhibition of adipogenesis, adipocyte hypertrophy and infiltration of immune cells13–15. Many molecules released by adipose tissue originate from non-adipocyte cells, such as endothelial and immune cells present in the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of adipose tissue9,13.

Critical issues are the unknown etiology of the disease and the lack of consistent diagnostic criteria leading to misdiagnosis in many cases. Clinicians must consider multiple criteria during the physical examination and conducting the medical history. A frequent comorbidity with 21.5% is cardiac disease16, however the risk of diabetes, dyslipidemia and hypertension is low despite an obese median body mass index (BMI)1,17.

To our knowledge, there are no blood-based parameters to identify lipedema patients so far. Due to this lack of systemic differences, we previously focused on the diseased tissue itself, specifically on the cellular components in which the disease is manifested and analyzed SVF cells isolated from liposuction material of lipedema patients. The isolated cells showed a reduced adipogenic differentiation potential as compared to healthy controls, similar to Bauer et al.18. However, we observed a higher cell yield after isolation, which might be due to the enhanced cell number of cluster of differentiation (CD) 90 (mesenchymal) and CD146 (endothelial) positive cells7. Moreover, the proliferation capacity of adipose-derived stem/progenitor/stromal cells (Ki67 + CD34 + cells) was enhanced in lipedema tissue8.

miRNAs are small non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression through RNA interference. More than 70% of all human coding genes are under the control of miRNAs. Intracellular miRNA transcription and subsequent miRNA release from cells within EVs and protein complexes, which protect the RNA cargo from degradation, can inform about the onset and progression of human diseases19. Several studies have shown that either the overall number of EVs and/or the relative miRNA cargo can be altered in response to stress such as senescence or subtoxic liver damage20,21. Nevertheless, several studies suggest that the majority of extracellular miRNAs are contained in protein complexes rather than exosomes/microvesicles22,23.

Based on our previous knowledge about the relevance of SVF cells in lipedema and the potential link between extracellular miRNA profiles and disease phenotypes, the aim of this study was to perform a thorough characterization of the extracellular miRNA fraction produced by the SVF in healthy (control) individuals and lipedema patients. For this, we analyzed 187 extracellular miRNAs in the concentrated conditioned medium (cCM) and specifically in sEVs isolated thereof by size exclusion chromatography (SEC), to determine the relevant fraction containing the lipedema discriminating miRNAs.

Methods

SVF isolation

Table 1 provides patient characteristics. Subcutaneous adipose tissue was obtained during routine outpatient liposuction procedures from the hips and outer thighs (“saddlebags”) under local tumescence anaesthesia. Tumescence solution (per liter) contained 3.3 mg Volon-A (Dermapharm), 1 vial Suprarenin 1 mg/mL (Sanofi-Aventis), 15 mL bicarbonate 8.4% (Fresenius Kabi) and 23.3 mL Xylocaine 1% (GebroPharma). The harvesting cannulas were triport and 4 mm in diameter (MicroAire System power-assisted liposuction). 100 mL liposuction material was transferred to a blood bag (Macopharma, Langen, Germany) and washed with an equal volume of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to remove blood and tumescence solution. Next, for tissue digestion PBS was replaced with 0.2 U/mL collagenase NB4 (Nordmark, Uetersen, Germany) dissolved in 100 mL PBS containing Ca2+/Mg2+and 25 mM N-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (HEPES; Sigma, Vienna, Austria), resulting in a final collagenase concentration of 0.1 U/mL. The blood bag was incubated at 37 °C under moderate shaking (180 rpm) for 1 h. The digested tissue was transferred into 50 mL-tubes (Greiner, Kremsmünster, Austria). After centrifugation at 1200 × g for 7 min the supernatant was removed and the cell pellet was incubated with 100 mL erythrocyte lysis buffer for 5 min at 37 °C to eliminate red blood cells. The supernatant after centrifugation for 5 min at 500 × g was aspirated and the cell pellet was washed with PBS and filtrated through a 100-µm cell strainer (Greiner). After another centrifugation step at 500 × g for 5 min the supernatant was removed. The isolated SVF was resuspended in medium filtrated (0.22 µm; Merck, Vienna, Austria) before: DMEM-low glucose (Lonza, Vienna, Austria) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Sigma, Vienna, Austria), 2 mM L-glutamine (Lonza). Cell number was determined using trypan blue exclusion and quantification in a cell counter (TC-20, Bio-Rad, Vienna, Austria).

Table 1.

Characteristics of control and lipedema patients.

| Characteristics | control | lipedema |

|---|---|---|

| N | 3 | 3 |

| Sex (M/F) | female | female |

| Age (years) | 35.0 ± 18.4 | 43 ± 14.2 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 24.2 ± 5.0 | 28.0 ± 4.5 |

| Type I-IV | — | 3 |

| Stage 1–2 | — | 3 |

The cohort underwent liposuction in this study were characterized regarding sex, age, and BMI and for lipedema patients the type and stage of lipedema. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Collection of cell supernatants

For miRNA analysis, DMEM-low glucose containing 10% FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine was filtrated using 0.22 µm filter cups. Preliminary experiments usingphotometric analysis of total RNA concentration (NanoDrop, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vienna, Austria) and subsequent analysis with the HS RNA Kit (Agilent) showed a negligible RNA concentration of medium not conditioned by cells, in comparison to cell conditioned medium (Supplementary Fig. S1), a contribution of FCS-derived miRNAs was considered unlikely. Therefore, we decided to include FCS in our medium to provide best possible conditions for SVF culture. 6 × 106 freshly isolated SVF cells were seeded in 22 mL filtrated medium in a T175 flask. The conditioned medium (CM) was collected after 24 h in a 50 mL-tube and centrifuged at 500 × g for 15 min (Eppendorf, 5804 R; Vienna, Austria) to remove cellular debris. After transfer to a new tube (VWR, Vienna, Austria) and centrifugation at 14000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C (HeraeusMultifuge X3R; Thermo Fisher Scientific) the supernatant was filtered through a 0.8 µm strainer (VWR) and immediately frozen and stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

Processing of supernatants for miRNA analysis

CM was concentrated to 1 mL using centrifugation-based ultrafiltration, resulting incCM. Briefly, 20 mL of CM were transferred to an Amicon 30 kDa ultrafiltration column (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and centrifuged at room temperature for 15 minutes. Residual volumes were measured and diluted to 1 mL using sterile PBS solution. sEVs were subsequently enriched from cCM by SEC using qEV70s single columns (Izon Science, Christchurch, New Zealand): 150 µL of cCM were loaded based on recommendations from the manufacturer, and fraction 8–11 were collected and pooled to obtain the fraction of enriched sEVs. Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) was performed on all sEV samples to determine particle size and concentration.

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA)

For determination of size and concentration of particles CM, cCM and sEV fractions obtained by SEC were analyzed onZetaView PMX 110 V3.0 particle analyseras previously described24 (Particle Metrix GmbH, Meerbusch, Germany).

MACSPlex surface protein profiling

The MACSPlexExosome Kit (MiltenyiBiotec, BergischGladbach, Germany) is a bead-based multiplexed FACS-based assay for the analysis of surface markers present on EVs. We have used the MACSPlex kit according to the manufacturer’s instruction and following a validated standard operating procedure with 5 × 107 to 5 × 108 particles as input. Data acquisition was conducted on a FACS Canto II (BD Biosciences). Data normalization was directed towards to CD9/CD63/CD81 to assess the level of specific marker positive EVs. Isotype control normalization was performed essentially as described25.

Total RNA extraction

Total RNA extraction was performed using 200 µl cCM or 200 µL pooled sEV fractions (fraction 8–11) together with the miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Synthetic oligonucleotides obtained from the miRCURY Spike-In kit (Qiagen) were added to the Qiazollysis buffer (Qiagen) before homogenization of the cCM/sEV samples. Glycogen (5 mg/mL) was added to the chloroform extract at 1:100 dilution to enhance precipitation. All other steps were performed according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. Total RNA was eluted in 30 µL nuclease-free water and stored at −80 °C in low-bind tubes (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) until further analysis.

MiRNA analysis

Reverse transcription (RT) of total RNA to complementary desoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) was performed in 50 µL reaction volumes using the miRCURY RT kit (Qiagen) and 10 µL total RNA as input. The RT mix was incubated at 42 °C for 60 min. The resulting cDNA was stored at −20 °C until further analysis. Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) reactions were prepared using the miRCURY SYBR Green mastermix and a final cDNA dilution of 1:50. PCR amplification was performed in 384-well pick&mix plates (Qiagen) with customized selection of 192 LNA-enhance primers to detect 187 endogenous miRNAs and 5 spike-in controls per sample. The mastermix/cDNA sample was added to 384-well plates using an epMotion liquid handling robot (Eppendorf). Following the preparation of plates, an incubation at 4 °C for at least 60 min was performed before the plates were analyzed on a LightCycler 480 II (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) using 45 cycles and a temperature profile recommended by the manufacturer for miRCURY SYBR Green mastermix. Cycle quantification (Cq)-values were called using the second-derivate maximum method. Data quality was assessed using spike-in controls (Supplementary Fig. S2) to determine RNA extraction efficiency, enzymatic inhibition, and overall variability. Data normalization was performed using the global mean (i.e. average Cq-value for all endogenous miRNAs with Cq < 35) to obtain delta Cq-values. In preliminary tests, three technical replicates of cell conditioned medium from one donor were analyzed for four different miRNAs. High reproducibility between technical replicates of the same donor was observed (Supplementary Fig. S3), wherefore we analyzed one replicate of the isolated SVF of each donor for further analyses.

MiRNA target analysis

MicroRNA target analysis was performed using the publicly available tool miRNet26. The list of differentially regulated miRNAs was uploaded as miRbase IDs and analyzed for gene targets with experimental verification. No tissue was selected as “context”. The node degree filter was set to 2.0 and gene enrichment was performed using hypergeometric testing and the reactome pathway database/gene classification27. Gene-pathway enrichment was also tested using the empirical sampling method to lower the risk of false-positives.

Statistical analysis

Exploratory data analysis was performed using ClustVis28. Global-mean normalized delta Cq-values (dCqs) were used for clustering analysis based on Euclidean distance and complete linkage. Unit variance row scaling was applied. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired two-sided t-tests.

Ethic statement

All experimental protocols concerning human adipose tissues were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Province of Upper Austria (application/approval number 200, 12.05.2005 and 19.05.2014). Informed consent was obtained from all patients, if subjects were under 18, from a parent and/or legal guardian. All methods involving humans in this study were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Clinical characteristics and sample collection

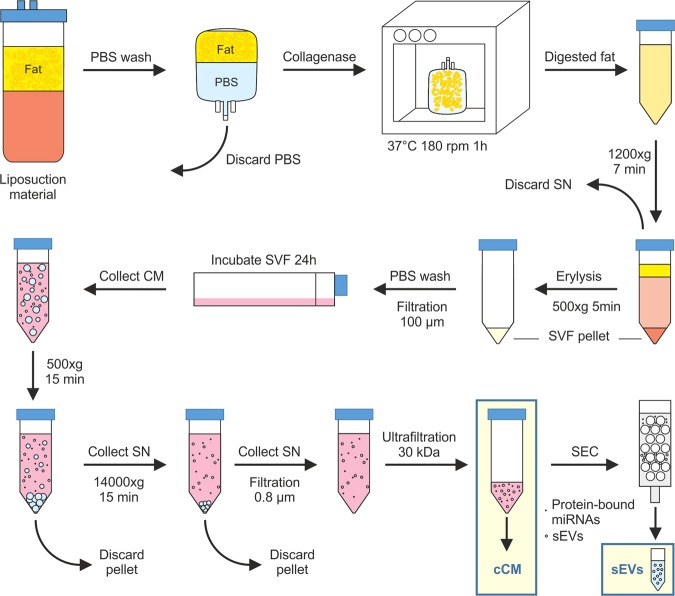

The cohorts that underwent liposuction in this study were all female, 3 healthy individuals (=control) and 3 lipedema (=lipedema) patients. Average age was 35.0 ± 18.4 for the control and 43 ± 14.2 years for the lipedema group. The BMI of the control group was 24.2 ± 5.0 kg/m2 and 28.0 ± 4.5 kg/m2 for the lipedema group. The BMI is similar in lipedema and healthy individuals (p-value 0.39), additionally the standard deviation was similar in healthy and lipedema indicating a comparable distribution within the cohorts. The slight enhancement in the lipedema cohort can be explained by the excessive fat accumulation in the thighs due to the disease. The three lipedema patients were categorized as type I-IV and stage 1–2 (according to Dr. Barsch and Dr. Sandhofer; Table 1). For collection of the samples (cCM and sEVs) all steps from liposuction (site, anesthesia, cannula) to SVF isolation, cultivation and preparation were performed consistently for each sample (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Experimental setup for SVF isolation, collection of cell supernatants and processing of supernatants for miRNA analysis.Subcutaneous adipose tissue was obtained during routine outpatient liposuction procedures. The liposuction material was washed and digested with collagenase. After centrifugation of the digested fat, the cell pellet was incubated with erythrocyte lysis buffer. After another centrifugation step, the cell pellet was washed and filtered and the isolated stromal vascular fraction (SVF) was incubated for 24 h in sterile filtered medium. Conditioned medium (CM) was collected and after two centrifugation steps and filtration, it was concentrated using centrifugation-based ultrafiltration to obtain concentrated CM (cCM). Small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) were enriched from cCM by size exclusion chromatography (SEC).

sEVs do not change in size or number in lipedema patients

In order to determine the relevance of SVF miRNAs in lipedema, we collected CM of adipose tissue derived SVF cells. NTA was employed to analyze particle size and concentration. By ultrafiltration a 17-fold enrichment of particles was achieved in the hereinafter called cCM (Supplementary Fig. S4a). sEVs were successfully separated from proteins of the cCM by SEC (Supplementary Fig. S4b). Fractions 8–11 showed the highest particle count and were pooled for further analysis. The particle diameter did not differ between cCM and sEVs (Supplementary Fig. S4c,d), indicating a comprehensive sEV enrichment. Particle size obtained by SEC ranged between 50 nm and 700 nm. The median particle size was determined to be 165 nm (+/−2.85) for the control group and 167 nm (+/− 10.78) for the lipedema group (Table 2). Similarly, no significant difference in particle concentration was observed between both groups, despite a trend towards higher concentrations in the lipedema group (FC = 1.41). Surface marker analysis of the EV preparation using a multiplex bead-based flow cytometry assay revealed also no significant differences between both groups (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Table 2.

Particle number and size of purified extracellular vesicles (EVs) from control and lipedema analyzed by nanoparticle tracking analysis.

| Group | Particle number [Particles/ul] | Median particle size [nm] | Mean particle size [nm] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| control 1 | 1.63E + 14 | 161 | 182 | |

| control 2 | 2.87E + 14 | 166 | 186 | |

| control 3 | 2.73E + 14 | 168 | 191 | |

| lipedema 1 | 5.07E + 14 | 153 | 167 | |

| lipedema 2 | 2.97E + 14 | 179 | 197 | |

| lipedema 3 | 2.20E + 09 | 168 | 187 | |

| control vs. lipedema | Effect Size (fold change) | 1.11 | 1.01 | 0.99 |

| control vs. lipedema | p-value (2-sided t test) | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.81 |

Nanoparticle tracking analysis was applied to the small EVs (sEVs) samples from controls and lipedema patients to determine concentration and size of purified nanoparticles. No significant differences were observed in particle concentration and particle size between controls and lipedema patients.

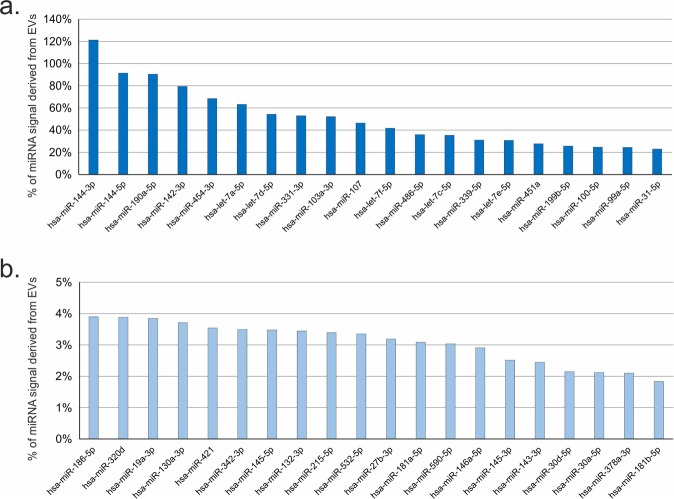

The majority of miRNAs are more abundant in cCM compared to sEV fraction

192-plex RT-qPCR panels were used to quantify 187 miRNAs and 5 control assays in all 12 samples (6x cCM and 6x sEV). Spike-in controls showed homogenous values across all 12 samples with low variability, demonstrating low analytical variability, no enzymatic inhibition and overall high quality of the analysis (Supplementary Fig. S2). In the cCM samples 182 out of 187 miRNAswere above the limit of detection, while 133 miRNAs were detectable in the sEV fractions. These 133 miRNAs were also detectable in the cCM. Therefore, this set of 133 miRNAs was used for all further statistical analyses. The global mean normalized miRNA levels in cCM samples were interpreted as the total miRNA signal, since the analysis captures miRNA cargo in EVs as well as protein complexes. In order to determine how much of the total signal came from the sEV fraction, the sEVenriched miRNA signals were related to the cCMmiRNA signals and expressed as percentage of miRNA signal derived from sEV. Figure 2 shows the top and bottom 20miRNAs (Fig. 2a,b) in sEV and cCM. Supplementary Table 1 presents the results for all 133 miRNAs. We identified three miRNAs, for which more than 90% of the signal in cCM originated from the sEV enriched fraction (miR-144-3p, miR-144-5p, miR-190a-5p), and 6 further miRNAs where >50% of the signal was derived from the sEV fraction. However, 83 out of 133 miRNAs were highly enriched in the non-sEV fraction as <10% of the total signal was obtained from the sEV fraction. This set of miRNAs included for example the miR-30 family and miR-23-24-27 family of miRNAs.

Figure 2.

Analysis of microRNA (miRNA) signal origin. miRNAs signals obtained in small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) were compared against the total miRNA signal in concentrated conditioned medium (cCM) and expressed as %. (a) Top 20 miRNAs with highest EV-derived signal: Three miRNAs, for which more than 90% of the signal in cCM originated from the sEV enriched fraction (miR-144-3p, miR-144-5p, miR-190a-5p), and 6 further miRNAs where more than 50% of the signal was derived from the sEV fraction could be found. (b) Bottom 20 miRNAs with signals mostly derived from non-EV miRNAs: 83 out of 133 miRNAs were highly enriched in the non-sEV fraction as less than 10% of the total signal was obtained from the sEV fraction.The 20 miRNAs with the lowest signal, were below 4%.

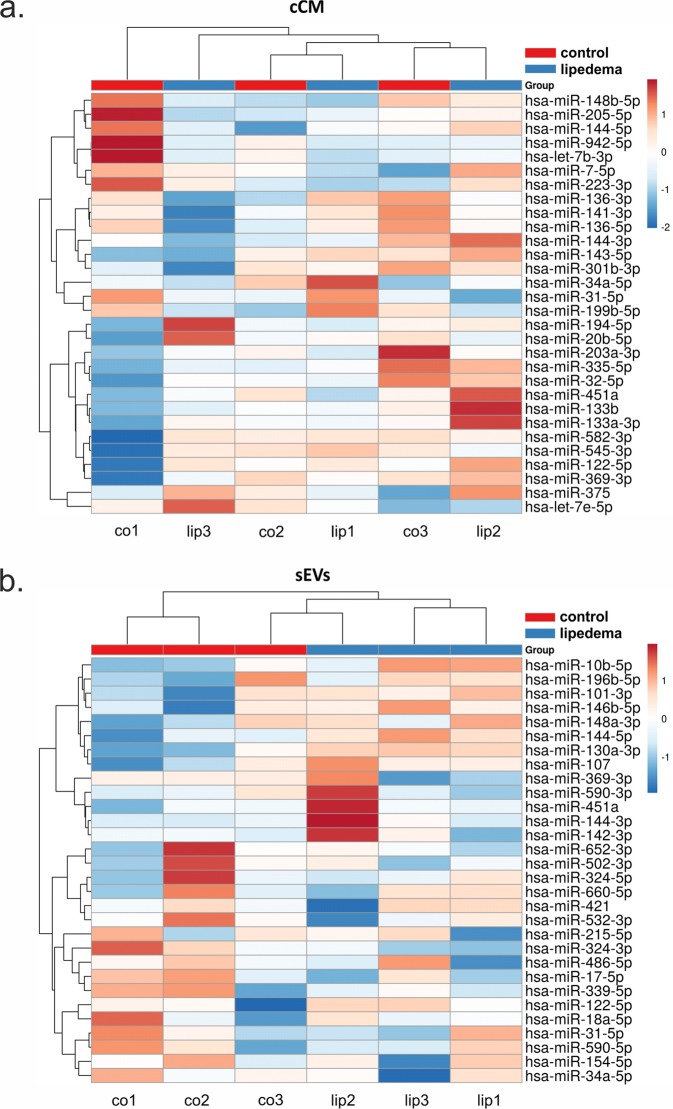

Clustering and differential expression analysis based on cCM and sEVmiRNA profiles

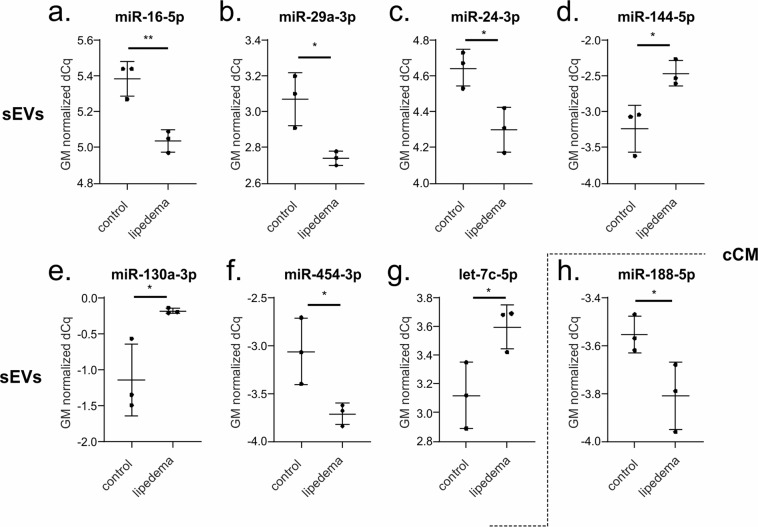

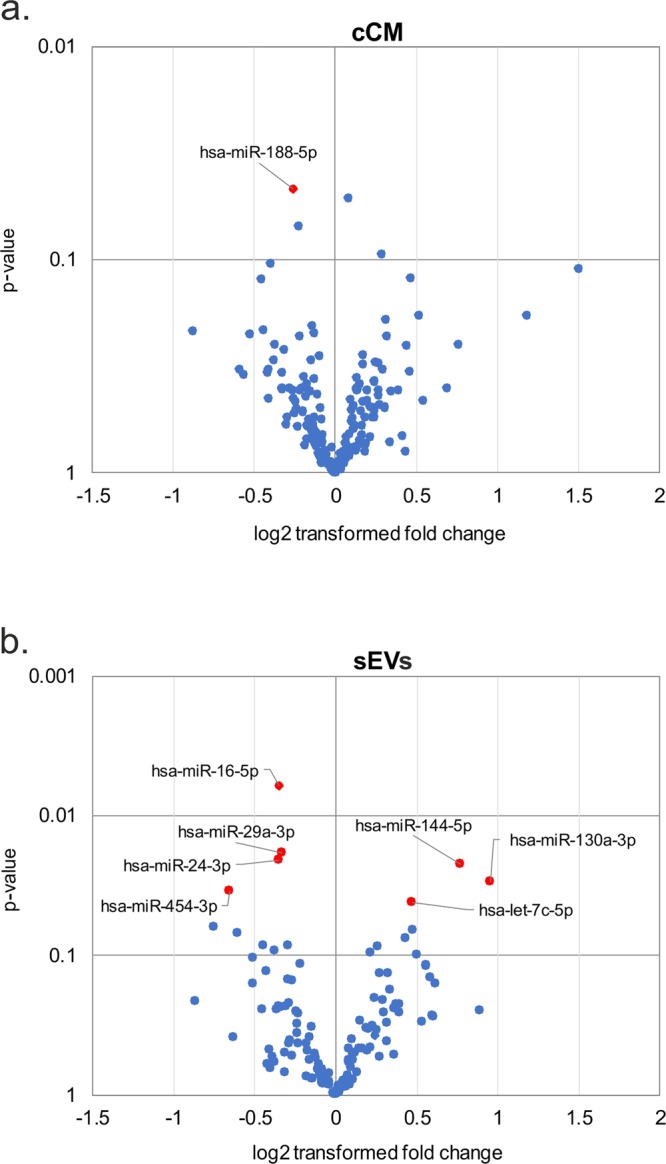

The most variant miRNAs in the cCM and sEV enriched fraction were selected based on the coefficient of variation and used for hierarchical clustering (Fig. 3). While the variability in the cCM miRNA data was not primarily influenced by the disease (Fig. 3a, no clusters corresponding to the groups), this was the case for sEV enriched miRNA data, where 2 control samples clustered, and 2 lipedema samples clustered. Next, we performed statistical analysis to identify potentially regulated miRNAs. In general, the overall trend in up- and down-regulated miRNAs between lipedema and control was balanced for both the cCM and sEV enriched fraction (Fig. 4a,b). When applying a cut-off of p < 0.05, we observed one miRNA (miR-188-5p, p = 0.047) to be significantly down-regulated in the cCM fraction of lipedema patients compared to controls (Fig. 5h). Interestingly, this miRNA was not detected in the sEV fraction. Vice-versa, 7 miRNAs (3 up: miR–144-5p, miR-130a-3p, let-7c-5p; 4 down; miR–16-5p, miR-29a-3p, miR-24-3p, miR-454-p,) were identified to be significantly regulated in the sEV enriched fraction (Fig. 5a–g).

Figure 3.

Hierarchical clustering of samples based on microRNA (miRNA) profiles observed in concentrated conditioned medium (cCM) or small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) from control (co) and lipedema (lip). The 30 most variant (according to coefficient of variation) miRNAs in cCM (a) and sEVs (b) were used for clustering analysis (Pearson correlation, average linkage). Rows are centered and unit variance scaling is applied to the global mean normalized expression values. Color indicates relative up- (red) or down-regulation for each miRNA (row). There were no clusters corresponding to the groups in the cCM miRNA data (a), while in the sEV enriched miRNA data 2 control samples clustered and 2 lipedema samples clustered (b).

Figure 4.

Differential secretion of extracellular microRNAs (miRNAs) between control and lipedema. 182 miRNAs were analyzed by RT-qPCR in concentrated conditioned medium (cCM) (a) and small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) (b) fractions. Volcano plots depict the log2 transformed fold change and p-value for the measured miRNAs. The overall trend in up- and down-regulated miRNAs between lipedema and control was balanced for both the cCM (a) and sEV (b) fraction. P-value < 0.05 are highlighted in red. n = 3 per group, unpaired two-tailed t-test.

Figure 5.

Scatterplots depicting global mean normalized levels of significantly regulated microRNAs (miRNAs) in small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) and concentrated conditioned medium (cCM) fraction.When applying a cut-off of p < 0.05, 7 miRNAs (3 up, 4 down) were identified to be significantly regulated in the sEV fraction: miR-16-5p (a), miR-29a-3p (b), miR-24-3p (c) and miR-454-3p (f) were downregulated in lipedema patients compared to controls, miR-144-5p (d), miR-130a-3p (e) and let-7c-5p (g) upregulated. One miRNA was identified to be significantly downregulated in the cCM fraction of lipedema patients compared to controls (h). n = 3 per group, unpaired two-tailed t-test, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Differentially regulated miRNAs analyzed for gene targets

In order to get insight into a biological potential impact of the differentially regulatedmiRNAs in lipedema, the 7 sEV- and 1 cCM- miRNAs were screened for experimentally validated miRNA/mRNA target pairs using miRNet. Pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the reactome pathway knowledgebase (Table 3). Thereby, we found in total 151 nodes comprising 144 target genes. To evaluate potentially impacted pathways, gene enrichment analysis of all annotated interactions between miRNAs and genes, identified 12 pathways with an adjusted p-value below 0.05. Among the pathways likely regulated by the 8 miRNAs were the NOTCH, Wnt and the SMAD/transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) signaling pathway, and pathways involved in processes such as oxidative stress and senescence. miR-130a-3p and miR-454-3p were found to be the miRNAs with the largest interaction network comprising 122 and 123 different mRNAs, respectively (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 3.

Reactome pathways identified by pathway enrichment analysis (www.mirnet.ca) for the differentially expressed miRNAs in lipedema versus control.

| Reactomepathway enrichment analysis | #Genes | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Oxidative Stress Induced Senescence | 7 | 0,0044 |

| Oncogene Induced Senescence | 5 | 0,0044 |

| Pre-NOTCH Transcription and Translation | 4 | 0,0064 |

| Pre-NOTCH Expression and Processing | 4 | 0,0102 |

| MicroRNA (miRNA) biogenesis | 4 | 0,0102 |

| Signaling by NOTCH | 6 | 0,0137 |

| SMAD2/SMAD3:SMAD4 heterotrimer regulates transcription | 4 | 0,0137 |

| Signaling by Wnt | 9 | 0,0228 |

| Cellular Senescence | 7 | 0,0228 |

| Signaling by TGF-beta Receptor Complex | 5 | 0,0383 |

| Gene Expression | 17 | 0,0410 |

| Transcriptional activity of SMAD2/SMAD3:SMAD4 heterotrimer | 4 | 0,0438 |

mRNA targets for miR–16-5p, miR-29a-3p, miR-24-3p, and miR-454-p, miR–144-5p, miR-130a-3p, let-7c-5p and miR-188-5p, which significantly discriminate lipedema versus control, were identified based on experimental data supporting interactions. Reactome pathway enrichment analysis was performed by miRNet. Among the pathways likely regulated by the 8 miRNAs were the NOTCH, Wnt and the SMAD/transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) signaling pathway, and pathways involved in oxidative stress and senescence. #Genes = number of detected genes, hypergeometric test p-value < 0.05 = significant.

Discussion

Since lipedema does not respond to lifestyle changes nor is there a treatment option other than liposuction of the diseased adipose tissue, a biomarker that would allow for identification of this disease and the prescription of liposuction by healthcare providers would be desirable. To date, diagnosis is based on clinical anamnesis, analytical weighing measurement and imaging of tissue composition by ultrasound. Additionally, non-invasive imaging such as MRI based quantification has been investigated. Adipose and sodium content in lipedema patients was found elevated in subcutaneous fat and skin, which hence has been suggested as potential biomarker for lipedema29. Since the disease is usually triggered by hormonal changes in females, a genetic susceptibility has been suggested30 (e.g. Williams-Beuern syndrome)31, however so far, no single gene causing the disease has been identified. The molecular load of EVs reflects the (patho-) physiological status of its original cells and thus can serve as a diagnostic tool, where sampling via liquid biopsies brings immense benefit to the physician and patient32. Besides the cell type-specific proteins, lipids and different classes of nucleic acids, EV contained miRNAs were found to be potent regulators in biological processes and in various diseases33,34. Numerous studies have already shown that the EV composition in diabetes, obesity, atherosclerosis, neurodegenerative diseases35, different cancers36–38 and renal damage39–41 distinguishes health and disease, which recommends them as potential diagnostic biomarkers. In fact, recent clinical trials have identified EVs as biomarker of prostate cancer42, Parkinson’s disease43 and difficult-to-treat arterial hypertension44.

Since miRNAs are crucial regulators of gene expression and are known to be involved in the progression of human diseases, our present study focused on extracellular miRNA in lipedema. Previously we identified that SVF cells from diseased subcutaneous WAT are altered in terms of adipogenesis, cell content and cellular subtype composition7. Thus, we sought to analyze the miRNA secretory profile of this cell population in lipedema versus healthy subjects (control). Considering the recent discussion about the relevance of extra- and intravesicular miRNAs45, we differentially analyzed the total and EV-contained miRNAssecreted by SVF from lipedemapatients and healthy controls. Turchinovich et al. postulated that extracellular miRNAs are predominantly non-vesicular, potentially a byproduct of dead cells but associated mostly with proteins22. In our study, the majority of the characterized miRNAs were indeed located extra-vesicular. However, we found that predominantly the EV-contained miRNA profile allowed discriminating healthy from lipedema, which was not the case for the secreted miRNA in the cCM, consisting mainly of extra-vesicular miRNAs. Additionally, when analyzing the surface marker profile of the EV preparations no significant differences between healthy individuals and lipedemapatients could be found. This demonstrates the importance of detailed characterization and especially the relevance of the EV cargo when characterizing the cellular status of a diseased tissue. We identifiedin our sEV preparations a significant reduction in miR–16-5p, miR-29a-3p, miR-24-3p, and miR-454-p, whereas miR–144-5p, miR-130a-3p and let-7c-5pwere significantly increased in lipedema compared to healthy controls. In the cCM, we found a significant reduction of one single miRNA, miR-188-5pin lipedema. MiR-188-5p has been described as a marker forage-related switch from osteogenic to adipogenic differentiation46. Further, miR-188-5p may have the potential to regulate migration and support of vascularization by mesenchymal stem cells (MSC), as previously described for a murine choroidal neovascularization model47. Deregulation of miR-188-5p might hence contribute to the endothelial barrier dysfunction and lymphangiopathy, which has been described in lipedema48. This suggests also a potential involvement of the MSC populations of the SVF in the progression of lipedema, since they are participating in the formation and stabilization of vessels49. It has been demonstrated that the total number of circulating particles (incl. their miRNA content) can be altered in disease34,50. In our study, particle number and size of enriched sEVs, analyzed by NTA, showed no difference between healthy individuals and lipedema patients. The majority of single miRNAsshowed higher abundance in cCM than in sEVs and only 9 of the analyzed miRNAs showed >50% signal originating from sEVs. miR-142-3p (80% sEV signal), was recently shown by another group to be selectively packaged in sEVs by a panel of oral squamous cell carcinoma cell lines, which resulted in lower intra-cellular levels and promoted malignant changes in these cells via increase of TGFBR1 expression51. Several miRNAs have recently been found to regulate adipose tissue biology and play a role in the development of obesity and related metabolic complications52–55. MiR-130 has been reported to inhibit adipocyte differentiation by the down-regulation of PPARγ56,57. Here, we found miR-130 significantly enhanced in lipedema which is in line with our previous work7 and the work of other groups18. Let-7 is one of the first miRNAs discovered. Knockout of let-7 family improved glucose tolerance in mice with diet-induced obesity58. In the present study, we observed a significant enhancement in let-7c-5p contents in sEVs from lipedema patients compared to healthy controls. Although we found significant increase in let-7c-5p, there is a consensus in the research field that lipedema does not favor the onset of diabetes, quite the opposite, lipedema negatively correlates with the development of insulin resistance. This is in line with observations by Pinnick et al. who found at cellular and miRNA level intrinsic differences between abdominal and gluteal adipose tissue. This result in an opposing metabolic disease risk, which is reduced forthe gluteal region – the site affected in lipedema59,60. Let-7c has been associated with regulation of macrophage polarization61. In a murine model of traumatic brain injury let-7c-5p protected mice from neuroinflammation and attenuated activation of microglia/macrophages62. This reported impact on macrophage polarization is also in consistence with another study demonstrating that miR-9, miR-127, miR-155, and miR-125b induce M1 polarization, while miR-124, miR-223, miR-34a, let-7c, miR-132, miR-146a, and miR-125a-5p promote M2 polarization in macrophages63. Since lipedema is an inflammatory disease accompanied by an infiltration of macrophages forming crown-like structure around adipocytes9, the local interplay of macrophages and cells of the diseased subcutaneous WAT, especially the contribution of EV miRNA communication, requires in depth investigation. When identifying potential target genes of the significantly up- and down-regulated miRNAs, we found regulatory molecules in Wnt signaling pathway, which play an important role in regulation of inflammation, oxidative stress and senescence64. Interestingly, our distinct secreted miRNAs were predicted to regulate a dynamic crosstalk of Wnt and another prominent pathway, NOTCH via targeting SMADs, which are also well-know nmediators of inflammatory, fibrotic, oxidative, proliferative, metabolic and angiogenic events65–67. The NOTCH super-signaling pathway plays an emerging role controlling key steps in the immune system and tissue homeostasis during repair and regeneration68. Notch interacts with SMADs to regulate blood vessel branching69 and promotes vascular sprouting through bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)/TGF-ß signaling70. The processes affected by regulation of the differentially regulated miRNAs - from oxidative stress to inflammation, angiogenesis, fibrosis have all been identified as part of the lipedema disease in the affected tissues6,8,18,71. This confirms the potential relevance of the identified SVF-secreted miRNAs in the cellular crosstalk during lipedema disease progression. As with the majority of studies, the design of the current study is subject to limitations. First, the sample size is too low to be able to control false-negative and false-positive rates sufficiently to claim the identified miRNAs more than biomarker candidates identified in a first discovery study. Second, when identifying sEV as the major source of the differentially regulated miRNA, we cannot exclude that even after the selected enrichment and purification steps, particles of other identity are enriched as stated in the latest misEV guidelines72. These data will now be useful to calculate power analysis for all future studies as it has become clear that differences exist. The important finding in this study is that differences in miRNA profile are mainly found in the sEV fraction. This indicates that in this disease, concerning SVF contribution, EVs rather than total RNA should be analyzed.

Here, we analyzed for the first time lipedema on miRNA level. Interestingly, all significantly regulated miRNAs found in this study may impact cellular processes that are reportedly affected by lipedema, such as adipogenesis, angiogenesis, inflammation and fat metabolism. We found a panel of 7 miRNAs that are influenced by lipedema in sEVs, whereas this was the case for only one miRNA in the total miRNA fraction. This study contributes to identify the role of SVF in the complex interplay of tissue components in lipedema on a miRNA level, where sEVs derived miRNAs were identified as the most relevant fraction.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

E.P., K.S., C.L., M.H. and S.W. made substantial contributions to conception and design, enquired and drafted the manuscript. M.B. and M.S. as medical partner performed the patient study and collected patient data. E.P., K.S., M.W., C.L., D.A. and M.G. performed the scientific experiments and analyzed data. M.B., J.J., J.G., H.R. and S.W. have given final approval and revised the manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare no competing interests, either financial or non-financial, in the work described. Matthias Hackl and Johannes Grillari are co-founder of TAmiRNA GmbH, Vienna, Austria. Matthias Hackl and Moritz Weigl are employed by TAmiRNA GmbH, Vienna, Austria.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally:Matthias Hackl and Susanne Wolbank.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-64215-w.

References

- 1.Torre, Y. S., Wadeea, R., Rosas, V.&Herbst, K. L.Lipedema: friend and foe. Hormone molecular biology and clinical investigation33, 10.1515/hmbci-2017-0076 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Wollina U. Lipedema-An update. Dermatologic Ther. 2019;32:e12805. doi: 10.1111/dth.12805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wold LE, Hines EA, Jr., Allen EV. Lipedema of the legs; a syndrome characterized by fat legs and edema. Ann. Intern. Med. 1951;34:1243–1250. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-34-5-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider M, Conway EM, Carmeliet P. Lymph makes you fat. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:1023–1024. doi: 10.1038/ng1005-1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szolnoky G, Nemes A, Gavaller H, Forster T, Kemeny L. Lipedema is associated with increased aortic stiffness. Lymphology. 2012;45:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Ghadban S, et al. Dilated Blood and Lymphatic Microvessels, Angiogenesis, Increased Macrophages, and Adipocyte Hypertrophy in Lipedema Thigh Skin and Fat Tissue. J. Obes. 2019;2019:8747461. doi: 10.1155/2019/8747461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Priglinger E, et al. The adipose tissue-derived stromal vascular fraction cells from lipedema patients: Are they different? Cytotherapy. 2017;19:849–860. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2017.03.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suga H, et al. Adipose tissue remodeling in lipedema: adipocyte death and concurrent regeneration. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2009;36:1293–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheja L, Heeren J. The endocrine function of adipose tissues in health and cardiometabolic disease. Nat. reviews. Endocrinol. 2019;15:507–524. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0230-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Funcke, J. B.&Scherer, P. E.Beyond adiponectin and leptin: adipose tissue-derived mediators of inter-organ communication. Journal of lipid research, 10.1194/jlr.R094060 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Thomou T, et al. Adipose-derived circulating miRNAs regulate gene expression in other tissues. Nature. 2017;542:450–455. doi: 10.1038/nature21365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ying W, et al. Adipose Tissue Macrophage-Derived Exosomal miRNAs Can Modulate In Vivo and In Vitro Insulin Sensitivity. Cell. 2017;171:372–384e312. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karastergiou K, Mohamed-Ali V. The autocrine and paracrine roles of adipokines. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2010;318:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weilner S, et al. Vesicular Galectin-3 levels decrease with donor age and contribute to the reduced osteo-inductive potential of human plasma derived extracellular vesicles. Aging. 2016;8:16–33. doi: 10.18632/aging.100865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weilner S, et al. Secreted microvesicular miR-31 inhibits osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Aging Cell. 2016;15:744–754. doi: 10.1111/acel.12484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romeijn JRM, de Rooij MJM, Janssen L, Martens H. Exploration of Patient Characteristics and Quality of Life in Patients with Lipoedema Using a Survey. Dermatology Ther. 2018;8:303–311. doi: 10.1007/s13555-018-0241-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandhofer, M. et al.Prevention of Progression of Lipedema With Liposuction Using Tumescent Local Anesthesia; Results of an International Consensus Conference. Dermatologic surgery: official publication for American Society forDermatologic Surgery [et al.], 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002019 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Bauer, A. T. et al.Adipose stem cells from lipedema and control adipose tissue respond differently to adipogenic stimulation in vitro. Plastic and reconstructive surgery, 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005918 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Mitchell PS, et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S Am. 2008;105:10513–10518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804549105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terlecki-Zaniewicz L, et al. Small extracellular vesicles and their miRNA cargo are anti-apoptotic members of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Aging. 2018;10:1103–1132. doi: 10.18632/aging.101452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holman NS, Mosedale M, Wolf KK, LeCluyse EL, Watkins PB. Subtoxic Alterations in Hepatocyte-Derived Exosomes: An Early Step in Drug-Induced Liver Injury? Toxicological sciences: an. Off. J. Soc. Toxicol. 2016;151:365–375. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfw047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turchinovich A, Weiz L, Langheinz A, Burwinkel B. Characterization of extracellular circulating microRNA. Nucleic acids Res. 2011;39:7223–7233. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arroyo JD, et al. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S Am. 2011;108:5003–5008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019055108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holnthoner W, et al. Endothelial Cell-derived Extracellular Vesicles Size-dependently Exert Procoagulant Activity Detected by Thromboelastometry. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:3707. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03159-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiklander OPB, et al. Systematic Methodological Evaluation of a Multiplex Bead-Based Flow Cytometry Assay for Detection of Extracellular Vesicle Surface Signatures. Front. immunology. 2018;9:1326. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan Y, et al. miRNet - dissecting miRNA-target interactions and functional associations through network-based visual analysis. Nucleic acids Res. 2016;44:W135–141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jassal B, et al. The reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic acids Res. 2020;48:D498–D503. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metsalu T, Vilo J. ClustVis: a web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucleic acids Res. 2015;43:W566–570. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crescenzi R, et al. Tissue Sodium Content is Elevated in the Skin and Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue in Women with Lipedema. Obesity. 2018;26:310–317. doi: 10.1002/oby.22090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Child AH, et al. Lipedema: an inherited condition. Am. J. Med. genetics. Part. A. 2010;152A:970–976. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waxler JL, et al. Altered body composition, lipedema, and decreased bone density in individuals with Williams syndrome: A preliminary report. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2017;60:250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stremersch S, De Smedt SC, Raemdonck K. Therapeutic and diagnostic applications of extracellular vesicles. J. controlled release: Off. J. Controlled Rel. Soc. 2016;244:167–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samanta S, et al. Exosomes: new molecular targets of diseases. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018;39:501–513. doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li M, et al. MicroRNAs: control and loss of control in human physiology and disease. World J. Surg. 2009;33:667–684. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9836-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malloci M, et al. Extracellular Vesicles: Mechanisms in Human Health and Disease. Antioxid. redox Signal. 2019;30:813–856. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liang B, et al. Characterization and proteomic analysis of ovarian cancer-derived exosomes. J. Proteom. 2013;80:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park YH, et al. Prostate-specific extracellular vesicles as a novel biomarker in human prostate cancer. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:30386. doi: 10.1038/srep30386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rupp AK, et al. Loss of EpCAM expression in breast cancer derived serum exosomes: role of proteolytic cleavage. Gynecologic Oncol. 2011;122:437–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheruvanky A, et al. Rapid isolation of urinary exosomal biomarkers using a nanomembrane ultrafiltration concentrator. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. physiology. 2007;292:F1657–1661. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00434.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.du Cheyron D, et al. Urinary measurement of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 3 (NHE3) protein as new marker of tubule injury in critically ill patients with ARF. Am. J. kidney diseases: Off. J. Natl Kidney Found. 2003;42:497–506. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00744-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou H, et al. Urinary marker for oxidative stress in kidneys in cisplatin-induced acute renal failure in rats. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: Off. Publ. Eur. Dialysis Transpl. Assoc. - Eur. Ren. Assoc. 2006;21:616–623. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Exosome Diagnostics, I. Clinical Validation of a Urinary Exosome Gene Signature in Men Presenting for Suspicion ofProstate Cancer. NCT02702856 (2015).

- 43.University of Alabama at, B., National Institute of Neurological, D. & Stroke. LRRK2and Other Novel Exosome Proteins in Parkinson’s Disease. NCT01860118 (2016).

- 44.University HospitalInselspital, B.&Universityof, Z. New Biomarkers and Difficult-to-treatHypertension. NCT03034265 (2017).

- 45.Sohel MH. Extracellular/Circulating microRNAs: release mechanisms, functions and challenges. Achiev. Life Sci. 2016;10:175–186. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li CJ, et al. MicroRNA-188 regulates age-related switch between osteoblast and adipocyte differentiation. J. Clin. investigation. 2015;125:1509–1522. doi: 10.1172/JCI77716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hou H, et al. MicroRNA-188-5p regulates contribution of bone marrow-derived cells to choroidal neovascularization development by targeting MMP-2/13. Exp. eye Res. 2018;175:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2018.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Szel E, Kemeny L, Groma G, Szolnoky G. Pathophysiological dilemmas of lipedema. Med. hypotheses. 2014;83:599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pill K, et al. Microvascular Networks From Endothelial Cells and Mesenchymal Stromal Cells From Adipose Tissue and Bone Marrow: A Comparison. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018;6:156. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2018.00156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luo J, Xiao Q. A novel approach for predicting microRNA-disease associations by unbalanced bi-random walk on heterogeneous network. J. Biomed. Inform. 2017;66:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dickman CT, et al. Selective extracellular vesicle exclusion of miR-142-3p by oral cancer cells promotes both internal and extracellular malignant phenotypes. Oncotarget. 2017;8:15252–15266. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pallante P, Battista S, Pierantoni GM, Fusco A. Deregulation of microRNA expression in thyroid neoplasias. Nature reviews. Endocrinology. 2014;10:88–101. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hossain MM, Sohel MM, Schellander K, Tesfaye D. Characterization and importance of microRNAs in mammalian gonadal functions. Cell tissue Res. 2012;349:679–690. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1469-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Derghal A, Djelloul M, Trouslard J, Mounien L. An Emerging Role of micro-RNA in the Effect of the Endocrine Disruptors. Front. Neurosci. 2016;10:318. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karbiener M, et al. MicroRNA-26 family is required for human adipogenesis and drives characteristics of brown adipocytes. Stem Cell. 2014;32:1578–1590. doi: 10.1002/stem.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee EK, et al. miR-130 suppresses adipogenesis by inhibiting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011;31:626–638. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00894-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qin L, et al. A deep investigation into the adipogenesis mechanism: profile of microRNAs regulating adipogenesis by modulating the canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. BMC genomics. 2010;11:320. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frost RJ, Olson EN. Control of glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity by the Let-7 family of microRNAs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U S Am. 2011;108:21075–21080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118922109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pinnick KE, et al. Distinct developmental profile of lower-body adipose tissue defines resistance against obesity-associated metabolic complications. Diabetes. 2014;63:3785–3797. doi: 10.2337/db14-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hilton C, et al. MicroRNA-196a links human body fat distribution to adipose tissue extracellular matrix composition. EBioMedicine. 2019;44:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Banerjee S, et al. MicroRNA let-7c regulates macrophage polarization. J. immunology. 2013;190:6542–6549. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lv J, et al. MicroRNA let-7c-5p improves neurological outcomes in a murine model of traumatic brain injury by suppressing neuroinflammation and regulating microglial activation. Brain Res. 2018;1685:91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Essandoh K, Li Y, Huo J, Fan GC. MiRNA-Mediated Macrophage Polarization and its Potential Role in the Regulation of Inflammatory Response. Shock. 2016;46:122–131. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ng, L. F.et al.WNT Signaling in Disease. Cells8, 10.3390/cells8080826 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Hu HH, et al. New insights into TGF-beta/Smad signaling in tissue fibrosis. Chemico-biological Interact. 2018;292:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bogaerts E, Heindryckx F, Vandewynckel YP, Van Grunsven LA, Van Vlierberghe H. The roles of transforming growth factor-beta, Wnt, Notch and hypoxia on liver progenitor cells in primary liver tumours (Review) Int. J. Oncol. 2014;44:1015–1022. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gordeeva, O. TGFbeta Family Signaling Pathways in Pluripotent and Teratocarcinoma Stem Cells’ Fate Decisions: Balancing Between Self-Renewal, Differentiation, and Cancer. Cells8, 10.3390/cells8121500 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Siebel C, Lendahl U. Notch Signaling in Development, Tissue Homeostasis, and Disease. Physiological Rev. 2017;97:1235–1294. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aspalter IM, et al. Alk1 and Alk5 inhibition by Nrp1 controls vascular sprouting downstream of Notch. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7264. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mouillesseaux KP, et al. Notch regulates BMP responsiveness and lateral branching in vessel networks via SMAD6. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:13247. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Siems W, Grune T, Voss P, Brenke R. Anti-fibrosclerotic effects of shock wave therapy in lipedema and cellulite. BioFactors. 2005;24:275–282. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520240132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Witwer KW, et al. Updating the MISEV minimal requirements for extracellular vesicle studies: building bridges to reproducibility. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2017;6:1396823. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2017.1396823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.