Abstract

Background

Sleep complaints are common health issues in the general population. These conditions are associated with poorer physical and psychological activity, and they may have important social, economic, and personal consequences. In the last years, several food supplements with different plant extracts have been developed and are currently taken for improving sleep. Study Objectives. The aim of this study is to systematically review recent literature on oral plant extracts acting on sleep disorders distinguishing their action on the different symptoms of sleep complaints: difficulty in initiating or maintaining sleep, waking up too early, and quality of sleep.

Methods

We searched the PubMed database up to 05/03/2020 based on data from randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, noncontrolled trials, and cohort studies conducted in children and adult subjects. The search words used contained the following terms: oral food supplement and sleep disorders and the like. The most studied compounds were further analyzed with a second search using the following terms: name of the compound and sleep disorders. We selected 7 emerging compounds and 38 relevant reports.

Results

Although nutraceutical natural products have been used for sleep empirically, there is a scarcity of evidence on the efficacy of each product in clinical studies. Valerian and lavender were the most frequently studied plant extracts, and their use has been associated (with conflicting results) with anxiolytic effects and improvements in quality and duration of sleep.

Conclusions

Sleep aids based on plant extracts are generally safe and well tolerated by the population. More high-quality research is needed to confirm the effectiveness of food supplements containing plant extracts in sleep complaints; in particular, it would be interesting to evaluate the association between plant extracts and sleep hygiene guidelines and to identify the optimal products to be used in a specific symptom of sleep complaint, giving more appropriate tools to the medical doctor.

1. Introduction

Insomnia is defined as dissatisfaction with sleep quality or quantity in addition to at least one other symptom among difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, or early morning awakening with inability to return to sleep [1]. Occasional insomnia is a very common disturb that has been reported to be experienced by about 30% of the U.S. general population [1–3]. Sleep disorders have an important societal and economic impact, with a consequent reduction in labour productivity or increased risk of accidents [4–6]. Chronic insomnia is also a risk factor for a variety of significant health problems, such as cardiovascular disease [7, 8], diabetes [9], and obesity [10], as well as bad mood and cognitive dysfunction [11–13]. Almost half of the individuals with sleep problems had never taken any steps to resolve them, and the majority of respondents had not spoken with a physician about their problems. Of those individuals who had consulted a physician, drug prescriptions had been given to approximately 50% in Western Europe and the USA [14]. The commonly used sleep aids based on benzodiazepine and non-benzodiazepine hypnotic drugs are often related to negative side effects such as daytime drowsiness, dependency, depression, hypnotic-withdrawal insomnia, and even excess mortality [15]. Moreover, there are limited data on long-term efficacy of hypnotic drugs [16]. Given these concerns and an increasing patient preference for nonpharmacological treatments [17], it is important to offer patients with insomnia evidence-based nonpharmacologic alternatives that may improve their sleep.

As defined in the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA), a dietary supplement is “a product (other than tobacco) intended to supplement the diet that bears or contains one or more dietary ingredients, including a vitamin, a mineral, an herb or other botanical, an amino acid, a dietary substance for use by humans to supplement the diet by increasing the total dietary intake of any of the aforementioned ingredients [18].” A growing body of evidence has shown promising results for these compounds in supporting health and body functions [19]. In particular, several dietary supplements are popularly used for sleep disorders [20], also in addition to other remedies (e.g., sleep hygiene and mind-body therapies) [21]. Moreover, no golden standard therapy is recommended to treat mild sleep disorders related to specific sleep stages (starting, maintaining, and ending sleep) [22, 23].

Our aim in this study was to systematically review recent literature on plant extracts and nutraceuticals administered orally and acting on sleep-related disorders. In particular, we differentiated the interventions and the outcomes of the studies based on the different sleep disorders (difficulty in initiating or maintaining sleep, quality and quantity of sleep, and waking up too early) and reviewed the available clinical data of the 7 most studied natural products: valerian, lavender, chamomile, hop, St. John's wort, hawthorn, and rosemary.

2. Materials and Methods

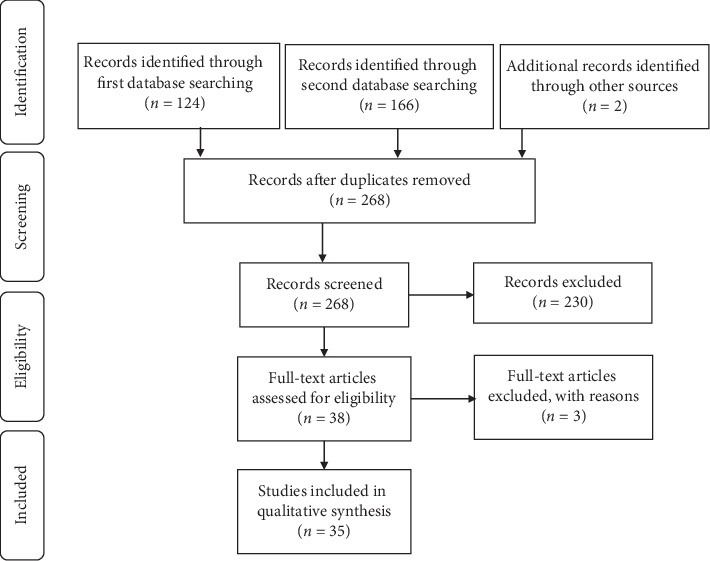

A literature search was performed using a primary medical search engine the PubMed database considering all articles published up to 05/03/2020; the registered review protocol can be found at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPEROFILES/126991_PROTOCOL_20190301.pdf. The review was registered on PROSPERO (international prospective register of systematic reviews in https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/), registration number CRD42019126991. The inclusion criteria were randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, noncontrolled trials, and cohort studies. We used the following search terms to search the PubMed register: (Oral food supplement) OR (Oral nutraceutical) OR (Oral natural products) AND (Sleep disorders) OR (Insomnia) AND “humans” [Filter] AND “English”[Filter]. The most studied compounds were singled out and further analyzed with a second search using the terms: (name of the compound) AND (Sleep disorders) OR (Insomnia) AND “humans”[Filter] AND “English”[Filter]. Only articles written in English and only studies conducted on humans were selected for this review. Additionally, the same research criteria were applied also for the Spanish language but no additional references were found. We contacted the study authors to retrieve the full article where only the abstract was available. We selected 7 emerging compounds and 35 relevant reports, excluding duplicates, nonrelevant articles, reviews, and works with no full article available (Figure 1). Information was extracted from each included trial in view of: (1) type of food supplement for sleep disorders (herbal component, dose, length of the treatment, and additional substances) and (2) clinical endpoints considering the different stages of sleep and sleep problems: sleep latency, sleep maintenance, quality of sleep, and quantity of sleep. Finally, the risk of bias of individual studies was considered both at study or outcome level, and the Jadad scale [24] for quality rating was used to assess the quality of works. Parameters considered were randomization, blinding, withdrawals, sample size, quality of data reported, and statistical analysis. Publication bias and selective reporting within studies are likely to be affecting the selected literature for this review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of information according to PRISMA 2009 [73].

3. Results

3.1. Valerian (Valeriana officinalis)

Valerian is the most studied plant for sleep disorders. We selected 17 articles on this subject to be included in the present review. The results of clinical trials performed to test valerian as a sleep aid are controversial and conflicting. Several studies showed an improvement in sleep quality [25–32] after administration of valerian at doses ranging from 160 to 600 mg a day. Differently, other studies reported no improvement in sleep quality (measured with Pittsburgh sleep quality index, PSQI, or perceived) [33–35]. Additionally, valerian was shown to reduce wake time after sleep onset [25, 27], to improve sleep latency and duration [36, 37], and to ameliorate insomnia severity score [38]. Conversely, a study from Jacobs and collaborators showed no changes in the insomnia severity score (ISI) compared to placebo [39]. Diaper and collaborators in a small study observed no changes in polysomnographic parameters or psychometric measures after one dose of 300 mg or 600 mg of valerian [40], and Coxeter reported no changes in total sleep time or number of nocturnal awakenings in the participants' responses in a n-of-1 analysis of 24 subjects [41].

Some trials investigated the possible mechanism of action of the effect of valerian as sleep aid. The study from Mineo and collaborators showed that a single oral dose of Valeriana officinalis extract caused a significant reduction in intracortical facilitation, a change associated with reduced anxiety [42].

3.2. Lavender (Lavandula)

In 2010, Woelk and collaborators showed in a double-blind, randomised study with 77 subjects that silexan, an oral lavender oil capsule preparation, is as effective as lorazepam in adults with generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) scores for anxiety and sleep diary scores demonstrated comparable positive effects [43]. Two studies from Kasper et al. in 2010 [44] and 2015 [45] with a dose of 80 mg of silexan showed significant improvement in sleep quality (PSQI) and anxiety (HAM-A) compared to placebo. Finally, an open-label trial with silexan and 47 participants indicated a reduction of nocturnal awakening frequency and duration after 6 weeks of assumption of the food supplement [46].

3.3. Hop

A double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial on 171 volunteers with sleep difficulties reported no significant changes in sleep quality (PSQI) after assumption of the LZComplex3 (hops 500 mg) for 2 weeks [47]. Another study with 101 volunteers with chronic primary insomnia assuming two gelatine capsules of Cyclamax® (50 mg hop) per day for a month, showed no effects on sleep quality Leeds sleep evaluation questionnaire (LSEQ), melatonin metabolism, and sleep-wake cycle [48].

3.4. Chamomile

A study on sixty elderly people who assumed chamomile extract capsules (200 mg) twice a day for 28 consecutive days reported improvements in general sleep quality and sleep latency (PSQI) [49].

Chang and colleagues conducted a study on the effects of drinking chamomile tea on sleep quality in sleep disturbed postnatal women and found a modest improvement in the PSQS (postpartum sleep quality scale) subscale “physical symptoms-related sleep inefficiency” at 2 weeks but not at 4 weeks [50]. Finally, Zick and colleagues performed a pilot trial with 34 subjects with DSM-IV primary insomnia and found no significant improvements in ISI and PSQI [51].

3.5. Hawthorn (Crataegus oxyacantha)

A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study with 264 subjects showed a reduction in total and somatic Hamilton scale scores for anxiety (p=0.005) [52].

No trial investigated directly the effects of hawthorn in sleep disorders.

3.6. St. John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum)

Many clinical trials tested the herb St. John's wort for mild to moderate depression. Al-Akoum et al. reported that 900 mg of St. John's wort decreased scores of the sleep problem scale compared with placebo in perimenopausal women after 12 weeks of oral administration [53].

No trial investigated directly the effects of St. John's wort in sleep disorders.

3.7. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.)

A randomized clinical trial from Nematolahi and collaborators on subjects who received 500 mg of rosemary showed a significant improvement in sleep quality using the PSQI after one month, but not on sleep latency and sleep duration [54].

3.8. Valerian and Hops

Some clinical trials investigated the combined effect of different plant extracts on sleep related problems; the most studied combination of ingredients is valerian and hop.

Dimpfel and Suter reported that a single dose administration of a valerian and hop fluid extract improved total sleep time and quality of sleep in poor sleepers [55]. Maroo et al. tested a mixture of valerian, passion flower, and hop extract and found significant improvements in sleep time, sleep latency, number of nightly awakenings, and insomnia severity index after a 2 week treatment [56]. Koetter et al. showed a reduction of sleep latency after a treatment period which lasted for 4 weeks with a fixed extract combination of valerian and hop [57].

Conversely, Morin et al. found very modest effects of a valerian and hop combination and only in quality of life scores [58]. Finally, a study from Sun investigated the effects of a mixture of herbal extracts (kava, hop, valerian, and many others) on sleep disturbance in menopausal women. The authors reported that the formula significantly reduced global PSQI score and scores in five components (sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep disturbance, and daytime dysfunction) [59].

Table 1 shows the 35 studies included in this review.

Table 1.

List of studies with selected compounds.

| Compound | First authors (year published) | Design | Total patients | Intervention | Reported outcomes/results | Journal | Jadad scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valerian | Taavoni 2013 [30] | Triple-blind, Randomized placebo-controlled trial |

100 | 160 mg of essence of valerian and lemon balm | Improvement in sleep quality (PSQI) | Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice | 3 |

| Taavoni 2011 [29] | Triple-blind, Randomized placebo-controlled trial |

100 | 530 mg valerian extract | Improvement in sleep quality (PSQI) | Menopause | 3 | |

| Barton 2011 [35] | Double-blind Randomized placebo-controlled trial |

119 | 450 mg of valerian | No improvement in sleep quality (PSQI) | The Journal of Supportive Oncology | 3 | |

| Cuellar 2009 [34] | Triple-blind, Randomized placebo-controlled trial |

37 | 800 mg of valerian | No improvement in sleep quality (PSQI) | Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine | 5 | |

| Waldschütz 2008 [37] | Open-label, prospective cohort study | 409 | Doses were at physicians' judgments | Improved sleep latency and duration | The Scientific World Journal | 1 | |

| Oxman 2007 [33] | Web-based randomized placebo-controlled trial | 405 | 200 mg extract per tablet (valerina forte). | No improvement in sleep quality perceived | PLoS One | 5 | |

| Müller 2006 [31] | Open, multicentre study | 918 | Euvegals forte (160 mg valerian root) | Reduced dyssomnia | Phytomedicine | 1 | |

| Jacobs 2005 [39] | Internet-based randomized, placebo-controlled trial | 391 | 2 valerian softgel capsules (3.2 mg of valerenic acids) | No changes in ISI | Medicine | 5 | |

| Diaper 2004 [40] | Placebo-controlled three way crossover | 16 | Acute valerian 300 mg or valerian 600 mg | No changes in EEG parameters or psychometric measures | Phytotherapy Research | 5 | |

| Coxeter 2003 [41] | Randomized n-of-1 trials | 24 | 225 mg V. officinalis root and rhizome extract | No changes in total sleep time or number of night awakenings | Complementary Therapies in Medicine | 5 | |

| Ziegler 2002 [28] | Randomized, double-blind, comparative trial | 202 | 600 mg/die valerian extract | Improvement in sleep quality | European Journal of Medical Research | NA | |

| Poyares 2002 [27] | Double-blind, Randomized placebo-controlled trial |

37 | 100 mg valerian (valmane) | Improvement in sleep quality and wake time after sleep onset | Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry | 3 | |

| Herrera-Arellano 2001 [26] | Double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled study | 20 | 450 mg of valerian | Improvement in sleep quality and morning sleepiness | Planta Medica | 3 | |

| Wheatley 2001 [38] | Cross-over study compared to kava | 19 | 600 mg of valerian | Improvement in insomnia severity scores | Phytotherapy Research | 1 | |

| Donath 2000 [36] | Double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled study | 16 | 300 mg dry extract valerian (sedonium) | Improvement in slow-wave sleep latency | Pharmacopsychiatry | 4 | |

| Lindahl 1988 [32] | Double-blind, Randomized placebo-controlled trial |

27 | 400 mg of valepotriates | Improvement in sleep quality | Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior | 4 | |

| Leathwood 1982 [25] | Double-blind, Randomized placebo-controlled trial |

128 | 400 mg valerian for 3 days | Improvement in sleep quality and wake time after sleep onset | Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior | 4 | |

| Lavender | Kasper 2015 [45] | Double-blind, Randomized placebo-controlled trial |

170 | 80 mg of silexan daily for 10 weeks | Improvement in sleep quality (PSQI) and anxiety (HAMA) | European Neuropsychopharmacology | 4 |

| Uehleke 2012 [46] | Open-label, exploratory trial | 47 | 1 × 80 mg/day silexan over 6 weeks | Reduced waking-up frequency and duration | Phytomedicine | 1 | |

| Kasper 2010 [44] | Double-blind, Randomized placebo-controlled trial |

221 | 80 mg of silexan daily for 10 weeks | Improvement in sleep quality (PSQI) and anxiety (HAMA) | International Clinical Psychopharmacology | 5 | |

| Woelk 2010 [43] | Double-blind, Randomized lorazepam-controlled trial |

77 | 1 × 80 mg/day silexan over 6 weeks | Improvement in anxiety (HAMA) and sleep quality (sleep diary) | Phytomedicine | 4 | |

| Hop | Scholey 2017 [47] | Double-blind, Randomized placebo-controlled trial |

171 | LZComplex3 (lactium, Zizyphus, Humulus lupulus, magnesium, and vitamin B6) hop 500 mg for 2 weeks | No changes in sleep quality (PSQI) | Nutrients | 5 |

| Cornu 2010 [48] | Double-blind, Randomized placebo-controlled trial |

101 | Two gelatine capsules of Cyclamax® (50 mg hop, 260 mg soya oil, 173 mg Cannabis sativa) per day for a month | No effects on sleep quality (LSEQ), melatonin metabolism, and sleep-wake cycle | BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine | 3 | |

|

| |||||||

| Chamomile | Adib-Hajbaghery 2017 [49] | Single-blind randomized controlled trial | 60 | 200 mg twice a day for 28 days | Improvement in general sleep quality and sleep latency (PSQI) | Complementary Therapies in Medicine | 3 |

| Chang 2016 [50] | A single-blinded, randomized controlled | 80 | one cup of chamomile tea per day for 2 weeks | Improvement in PSQS | Journal of Advanced Nursing | 3 | |

| Zick 2011 [51] | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled pilot trial | 34 | 270 mg of chamomile twice daily for 28 days | No significant improvement in ISI and PSQI | BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine | 5 | |

|

| |||||||

| Hawthorn | Hanus 2003 [52] | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial | 264 | 150 mg twice daily for 3 months | Reduction in Hamilton Anxiety Scale | Current Medical Research and Opinion | 4 |

|

| |||||||

| St. John's wort | Al-Akoum 2009 [53] | Pilot double-blind, randomized | 47 | 900 mg three times daily | Improvement in general sleep quality (SPS) | Menopause | 5 |

|

| |||||||

| Rosemary | Nematolahi 2018 [54] | Double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial | 68 | 500 mg rosemary | Improvement in sleep quality (PSQI) | Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice | 3 |

| Valerian + hop | Maroo 2013 [56] | Double-blinded randomized Zolpidem-controlled trial | 78 | 300 mg valerian, 80 mg passion flower, and 30 mg hop | Improvement in total sleep time, sleep latency, number of nightly awakenings, and ISI | Indian Journal of Pharmacology | 5 |

| Dimpfel 2008 [55] | Double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial | 42 | 460 mg of valerian and 460 mg of hop single dose | Improvement in sleep quality (deep sleep) and sleep quantity | European Journal of Medical Research | 3 | |

| Koetter 2007 [57] | Double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial | 27 | 500 mg of valerian and 120 mg of hop for 4 weeks | Improvement in sleep latency | Phytotherapy Research | 2 | |

| Morin 2005 [58] | Double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial | 184 | 2 tablets of 187 mg of valerian and 41.9 mg of hop for 28 days | Improvement in quality of life (physical component) | Sleep | 3 | |

| Sun 2003 [59] | Open, noncomparative trial | 72 | 200 mg valerian, 100 mg hop, kava and other components | Improvement in sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep disturbance (PSQI) | The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine | 0 | |

SPS = sleep problem scale, PSQI = Pittsburg sleep quality inventory, PSQS = postpartum sleep quality scale, LSEQ = Leeds sleep evaluation questionnaire, and ISI = insomnia severity index.

Table 2 summarizes the effects of the different compounds on sleep parameters.

Table 2.

Sleep outcomes.

| Compounds | SL | WASO | TST | QOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valerian | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Lavender | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Hop | ||||

| Chamomile | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Hawthorn | ||||

| St. John's wort | ✓ | |||

| Rosemary | ✓ |

SL = sleep latency, WASO = wake after sleep onset, TST = total sleep time, and QOS = quality of sleep.

4. Discussion

Sleep disturbances are widespread and affect a high percentage of the general population [1–3].

Food supplements use for sleep complaints is extensively adopted. In a survey in the province of Quebec on almost 1000 subjects, 18.5% participants reported having used natural products as sleep aids [60].

The most commonly used plant extracts for insomnia are valerian, chamomile, and lavender. In general, the selected studies showed a good quality with an average of 3, 4 points in the Jadad scale (0–5) [24] for quality rating, only 6 studies were evaluated with a score <3 and 10 studies with a score of 5. Many studies, however, are limited by small numbers of participants and, in some instances, inadequate design and sparse use of objective measurements. As mentioned by Fernández-San-Martín et al. in a metanalysis on lavender use for sleep disturbances [61], a wide range of dosages and types of preparations are often used and most measurement methods are open for interpretation. When the analysis is performed with quantifiable variables (latency time in minutes and sleep quality measured with VAS), no significant improvement is frequently found.

There is preliminary but conflicting evidence suggesting valerian and lavender as possible sleep aids for mild problems of quality of sleep, sleep latency, total sleep time, and waking up after sleep onset. Notably, the studies contrasted the efficacy of valerian rated with a high Jadad score (5 studies with score of 5, Table 1). On the other hand, a recent meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials showed a significant effect of lavender oil (Silexan) in reducing the HAMA total score for psychic and somatic anxiety and for observer-assessed and self-assessed anxiety [62].

Valerian activity on sleep disturbances has been attributed to the presence of isovaleric acids and valepotriates with reported calming action [63] and GABA reuptake inhibition with sedative effects [64]. Considering the data presented in the literature, valerian seems more effective for chronic insomnia than acute episodes.

The main components of the lavender preparations are linalyl acetate and linalool [65]. In mice, these components led to anticonvulsant effects [66], depression of motor activity, and calming effects [65].

Sparse or no scientific data were found to support the efficacy of most products as hypnotics, including chamomile, hop (alone), hawthorn, St. John's wort, and rosemary. Notably, one recently published systematic review and a meta-analysis indicated chamomile as efficacious and safe for improving sleep quality and generalized anxiety disorders but highlighted scarce effect for insomnia [67, 68].

Other plant extracts have been proposed and tested in clinical trials. Kava kava has been well studied and has showed good results in reducing anxiety and hypnotic effects [69], but because of its hepatotoxic effects, the prescription has been forbidden [64]. In addition, extracts from poppy, passionflower, and lemon balm (Melissa) to mention the most popular ones have been investigated in sleep disturbances, but so far, the amount of data is not sufficient to evaluate their effect on these disorders.

Unfortunately, not many trials tested the efficacy of a combined nonpharmacological intervention based on the administration of plant extracts and standardized sleep hygiene in subjects with mild to moderate insomnia. This combination could improve the efficacy in many trials where a single herbal extract was tested. In support of this hypothesis, a study by Maroo et al. [56] showed that a composition of valerian, passionflower, and hop improved total sleep time, sleep latency, number of nightly awakenings, and insomnia severity index. Moreover, a pilot study testing a combination of melatonin, vitamin B6, and various plant extract showed a positive result in sleep quality, sleep onset latency, and total sleep duration [70].

The management of sleep complaints relies on both pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches. The last years evidenced a decrease in using sedative and hypnotic drugs to treat these conditions. On the other hand, the population and the medical community are considering food supplements and other nonpharmacological approaches in the management of mild and recent insomnia [71]. To date, however, as pointed out in various recent systematic reviews [21, 72], more high-quality research is needed to confirm the effectiveness of plant extracts in sleep disorders, in particular for chronic conditions and in association with complementary and alternative medicine, such as sleep hygiene and mind-body therapies.

Acknowledgments

This work was entirely funded by Opera CRO S.r.l., Timisoara (Romania).

Disclosure

An abstract and preliminary data relevant to this review were presented at the conference Vitafoods 2019 in Geneva in a poster titled as “Food supplements for sleep disorders: a systematic review.”

Conflicts of Interest

SG, DFB and SR are employed at Opera CRO, the Contract Research Organization.

Authors' Contributions

SG, DFB, and SR conceived the work.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) 5th. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ancoli-Israel S., Roth T. Characteristics of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 national sleep foundation survey. I. Sleep. 1999;22(2):S347–S353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roth T. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2007;3(5):S7–S10. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.26929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Léger D., Bayon V. Societal costs of insomnia. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2010;14(6):379–389. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler R. C., Berglund P. A., Coulouvrat C., et al. Insomnia and the performance of US workers: results from the America insomnia survey. Sleep. 2011;34(9):1161–1171. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarsour K., Kalsekar A., Swindle R., Foley K., Walsh J. K. The association between insomnia severity and healthcare and productivity costs in a health plan sample. Sleep. 2011;34(4):443–450. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.4.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suka M., Yoshida K., Sugimori H. Persistent insomnia is a predictor of hypertension in Japanese male workers. Journal of Occupational Health. 2003;45(6):344–350. doi: 10.1539/joh.45.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chien K.-L., Chen P.-C., Hsu H.-C., et al. Habitual sleep duration and insomnia and the risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause death: report from a community-based cohort. Sleep. 2010;33(2):177–184. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vgontzas A. N., Liao D., Pejovic S., Calhoun S., Karataraki M., Bixler E. O. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with type 2 diabetes: a population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(11):1980–1985. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel S. R., Blackwell T., Redline S., et al. The association between sleep duration and obesity in older adults. International Journal of Obesity. 2005;32(12):1825–1834. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth T., Ancoli-Israel S. Daytime consequences and correlates of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 national sleep foundation survey. II. Sleep. 1999;22(2):S354–S358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohayon M. M., Roth T. Place of chronic insomnia in the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2003;37(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez-Mendoza J., Calhoun S., Bixler E. O., et al. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with deficits in neuropsychological performance: a general population study. Sleep. 2010;33(4):459–465. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.4.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Léger D., Poursain B., Neubauer D., Uchiyama M. An international survey of sleeping problems in the general population. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2008;24(1):307–317. doi: 10.1185/030079907x253771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kripke D. Hypnotic drug risks of mortality, infection, depression, and cancer: but lack of benefit. 5:p. 918. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.8729.3. , F1000Research, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buscemi N., Vandermeer B., Friesen C., et al. The efficacy and safety of drug treatments for chronic insomnia in adults: a meta-analysis of RCTs. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(9):1335–1350. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0251-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morin C. M., Gaulier B., Barry T., Kowatch R. A. Patients’ acceptance of psychological and pharmacological therapies for insomnia. Sleep. 1992;15(4):302–305. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.4.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rehnquist J. Department of Health and Human Services: Office of the Inspector General—Dietary Supplement Labels: Key Elements (OEI-01-01-00120) Washington, DC, USA: United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nasri H., Baradaran A., Shirzad H., Rafieian-Kopaei M. New concepts in nutraceuticals as alternative for pharmaceuticals. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;5(12):1487–1499. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meoli A. L., Rosen C., Kristo D., et al. Oral nonprescription treatment for insomnia: an evaluation of products with limited evidence. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2005;1(2):173–187. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.26314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou E. S., Gardiner P., Bertisch S. M. Integrative medicine for insomnia. Medical Clinics of North America. 2017;101(5):865–879. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pagel J. F., Parnes B. L. Medications for the treatment of sleep disorders: an overview. The Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;3(3):118–125. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v03n0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roth T., Roehrs T., Pies R. Insomnia: pathophysiology and implications for treatment. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2007;11(1):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jadad A. R., Moore R. A., Carroll D., et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Controlled Clinical Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leathwood P. D., Chauffard F., Heck E., Munoz-Box R. Aqueous extract of valerian root (Valeriana officinalis L.) improves sleep quality in man. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1982;17(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrera-Arellano A., Luna-Villegas G., Cuevas-Uriostegui M., et al. Polysomnographic evaluation of the hypnotic effect of Valeriana edulis standardized extract in patients suffering from insomnia. Planta Medica. 2001;67(8):695–699. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poyares D. R., Guilleminault C., Ohayon M. M., Tufik S. Can valerian improve the sleep of insomniacs after benzodiazepine withdrawal? Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2002;26(3):539–545. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ziegler G., Ploch M., Miettinen-Baumann A., Collet W. Efficacy and tolerability of valerian extract LI 156 compared with oxazepam in the treatment of non-organic insomnia—a randomized, double-blind, comparative clinical study. European Journal of Medical Research. 2002;7(11):480–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taavoni S., Ekbatani N., Kashaniyan M., Haghani H. Effect of valerian on sleep quality in postmenopausal women: a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Menopause. 2011;18(9):951–955. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31820e9acf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taavoni S., Nazem Ekbatani N., Haghani H. Valerian/lemon balm use for sleep disorders during menopause. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2013;19(4):193–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Müller S. F., Klement S. A combination of valerian and lemon balm is effective in the treatment of restlessness and dyssomnia in children. Phytomedicine. 2006;13(6):383–387. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindahl O., Lindwall L. Double blind study of a valerian preparation. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1989;32(4):1065–1066. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oxman A. D., Flottorp S., Håvelsrud K., et al. A televised, web-based randomised trial of an herbal remedy (valerian) for insomnia. PLoS One. 2007;2(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001040.e1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cuellar N. G., Ratcliffe S. J. Does valerian improve sleepiness and symptom severity in people with restless legs syndrome? Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 2009;15(2):22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barton D. L., Atherton P. J., Bauer B. A., et al. The use of Valeriana officinalis (Valerian) in improving sleep in patients who are undergoing treatment for cancer: a phase III randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study (NCCTG trial, N01C5) The Journal of Supportive Oncology. 2011;9(1):24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donath F., Quispe S., Diefenbach K., Maurer A., Fietze I., Roots I. Critical evaluation of the effect of valerian extract on sleep structure and sleep quality. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2000;33(2):47–53. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-7972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waldschütz R., Klein P. The homeopathic preparation neurexan® vs. valerian for the treatment of insomnia: an observational study. The Scientific World Journal. 2008;8:10. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2008.61.689282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wheatley D. Kava and valerian in the treatment of stress-induced insomnia. Phytotherapy Research. 2001;15(6):549–551. doi: 10.1002/ptr.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobs B. P., Bent S., Tice J. A., Blackwell T., Cummings S. R. An internet-based randomized, placebo-controlled trial of kava and valerian for anxiety and insomnia. Medicine. 2005;84(4):197–207. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000172299.72364.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diaper A., Hindmarch I. A double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation of the effects of two doses of a valerian preparation on the sleep, cognitive and psychomotor function of sleep-disturbed older adults. Phytotherapy Research. 2004;18(10):831–836. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coxeter P. D., Schluter P. J., Eastwood H. L., Nikles C. J., Glasziou P. P. Valerian does not appear to reduce symptoms for patients with chronic insomnia in general practice using a series of randomised n-of-1 trials. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2003;11(4):215–222. doi: 10.1016/s0965-2299(03)00122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mineo L., Concerto C., Patel D., et al. Valeriana officinalis root extract modulates cortical excitatory circuits in humans. Neuropsychobiology. 2017;75(1):46–51. doi: 10.1159/000480053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woelk H., Schläfke S. A multi-center, double-blind, randomised study of the Lavender oil preparation Silexan in comparison to Lorazepam for generalized anxiety disorder. Phytomedicine. 2010;17(2):94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kasper S., Gastpar M., Müller W. E., et al. Silexan, an orally administered Lavandula oil preparation, is effective in the treatment of “subsyndromal” anxiety disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;25(5):277–287. doi: 10.1097/yic.0b013e32833b3242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kasper S., Anghelescu I., Dienel A. Efficacy of orally administered Silexan in patients with anxiety-related restlessness and disturbed sleep: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. European Neuropsychopharmacologyl. 2015;25(11):1960–1967. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uehleke B., Schaper S., Dienel A., Schlaefke S., Stange R. Phase II trial on the effects of Silexan in patients with neurasthenia, post-traumatic stress disorder or somatization disorder. Phytomedicine. 2012;19(8-9):665–671. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scholey A., Benson S., Gibbs A., Perry N., Sarris J., Murray G. Exploring the effect of Lactium™ and zizyphus complex on sleep quality: a double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients. 2017;9(2):p. 154. doi: 10.3390/nu9020154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cornu C., Remontet L., Noel-Baron F., et al. A dietary supplement to improve the quality of sleep: a randomized placebo controlled trial. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2010;10(1):p. 29. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adib-Hajbaghery M., Mousavi S. N. The effects of chamomile extract on sleep quality among elderly people: a clinical trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2017;35:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chang S.-M., Chen C.-H. Effects of an intervention with drinking chamomile tea on sleep quality and depression in sleep disturbed postnatal women: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2016;72(2):306–315. doi: 10.1111/jan.12836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zick S. M., Wright B. D., Sen A., Arnedt J. T. Preliminary examination of the efficacy and safety of a standardized chamomile extract for chronic primary insomnia: a randomized placebo-controlled pilot study. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011;11(1):p. 78. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-11-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hanus M., Lafon J., Mathieu M. Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a fixed combination containing two plant extracts (Crataegus oxyacantha and Eschscholtzia californica) and magnesium in mild-to-moderate anxiety disorders. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2004;20(1):63–71. doi: 10.1185/030079903125002603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Al-Akoum M., Maunsell E., Verreault R., Provencher L., Otis H., Dodin S. Effects of Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s wort) on hot flashes and quality of life in perimenopausal women: a randomized pilot trial. Menopause. 2009;16(2):307–314. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818572a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nematolahi P., Mehrabani M., Karami-Mohajeri S., Dabaghzadeh F. Effects of Rosmarinus officinalis L. on memory performance, anxiety, depression, and sleep quality in university students: a randomized clinical trial. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2018;30:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dimpfel W., Suter A. Sleep improving effects of a single dose administration of a valerian/hops fluid extract: a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled sleep-EEG study in a parallel design using electrohypnograms. European Journal of Medical Research. 2008;13(5):200–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maroo N., Hazra A., Das T. Efficacy and safety of a polyherbal sedative-hypnotic formulation NSF-3 in primary insomnia in comparison to zolpidem: a randomized controlled trial. Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 2013;45(1):34–39. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.106432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koetter U., Schrader E., Käufeler R., Brattström A. A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled, prospective clinical study to demonstrate clinical efficacy of a fixed valerian hops extract combination (Ze 91019) in patients suffering from non-organic sleep disorder. Phytotherapy Research. 2007;21(9):847–851. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morin C. M., Koetter U., Bastien C., Ware J. C., Wooten V. Valerian-hops combination and diphenhydramine for treating insomnia: a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Sleep. 2005;28(11):1465–1471. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.11.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun J. Morning/evening menopausal formula relieves menopausal symptoms: a pilot study. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2003;9(3):403–409. doi: 10.1089/107555303765551624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sánchez-Ortuño M. M., Bélanger L., Ivers H., LeBlanc M., Morin C. M. The use of natural products for sleep: a common practice? Sleep Medicine. 2009;10(9):982–987. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fernández-San-Martín M. I., Masa-Font R., Palacios-Soler L., Sancho-Gómez P., Calbó-Caldentey C., Flores-Mateo G. Effectiveness of Valerian on insomnia: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Sleep Medicine. 2010;11(6):505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Möller H.-J., Volz H.-P., Dienel A., Schläfke S., Kasper S. Efficacy of Silexan in subthreshold anxiety: meta-analysis of randomised, placebo-controlled trials. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2019;269(2):183–193. doi: 10.1007/s00406-017-0852-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morazzoni P., Bombardelli E. Valeriana officinalis: traditional use and recent evaluation of activity. Fitoter. 1995;66(2):p. 99. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wheatley D. Herbal products, stress, and the mind. In: Yehuda S., Mostofsky D. I., editors. Nutrients, Stress, and Medical Disorders. Totowa, NJ, USA: Humana Press; 2005. pp. 137–153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Buchbauer G., Jirovetz L., Jäger W., Dietrich H., Plank C. Aromatherapy: evidence for sedative effects of the essential oil of lavender after inhalation. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C. 1991;46(11–12):1067–1072. doi: 10.1515/znc-1991-11-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lis-Balchin M., Hart S. Studies on the mode of action of the essential oil of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia P. Miller) Phytotherapy Research. 1999;13(6):540–542. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1573(199909)13:6<540::aid-ptr523>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shang B., Yin H., Jia Y., et al. Nonpharmacological interventions to improve sleep in nursing home residents: a systematic review. Geriatric Nursing. 2019;40(4):405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hieu T. H., Dibas M., Surya Dila K. A., et al. Therapeutic efficacy and safety of chamomile for state anxiety, generalized anxiety disorder, insomnia, and sleep quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials and quasi-randomized trials. Phytotherapy Research. 2019;33(6):1604–1615. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schulz V., Hänsel R., Tyler V. E. Rational Phytotherapy: A Physicians’ Guide to Herbal Medicine. 4th. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lemoine P., Bablon J.-C., Da Silva C. A combination of melatonin, vitamin B6 and medicinal plants in the treatment of mild-to-moderate insomnia: a prospective pilot study. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2019;45:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cheung J. M. Y., Bartlett D. J., Armour C. L., Saini B., Laba T.-L. Patient preferences for managing insomnia: a discrete choice experiment. The Patient—Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. 2018;11(5):503–514. doi: 10.1007/s40271-018-0303-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wheatley D. Medicinal plants for insomnia: a review of their pharmacology, efficacy and tolerability. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2005;19(4):414–421. doi: 10.1177/0269881105053309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G., The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.e1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA 2009 Checklist.