Abstract

To address the need for more meaningful biomarkers of tauopathies, we have developed an ultrasensitive tau seed amplification assay (4R RT-QuIC) for the 4-repeat (4R) tau aggregates of progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), and other diseases with 4R tauopathy. The assay detected seeds in 106–109-fold dilutions of 4R tauopathy brain tissue but was orders of magnitude less responsive to brain with other types of tauopathy, such as from Alzheimer’s disease cases. The analytical sensitivity for synthetic 4R tau fibrils was ~ 50 fM or 2 fg/sample. A novel dimension of this tau RT-QuIC testing was the identification of three disease-associated classes of 4R tau seeds; these classes were revealed by conformational variations in the in vitro amplified tau fibrils as detected by thioflavin T fluorescence amplitudes and FTIR spectroscopy. Tau seeds were detected in postmortem cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from all neuropathologically confirmed PSP and CBD cases but not in controls. CSF from living subjects had weaker seeding activities; however, mean assay responses for cases clinically diagnosed as PSP and CBD/corticobasal syndrome were significantly higher than those from control cases. Altogether, 4R RT-QuIC provides a practical cell-free method of detecting and subtyping pathologic 4R tau aggregates as biomarkers.

Keywords: Tau, Progressive supranuclear palsy, Corticobasal degeneration, Strain, Diagnosis, Biomarker

Introduction

At least 26 different human neurodegenerative diseases involving tau pathology have been identified (reviewed in [19]) and collectively called tauopathies. These diseases can differ in their clinical presentations, but are often difficult to discriminate from one another and from other neurodegenerative diseases, especially in early clinical phases. Variations and overlaps in clinical features can complicate the identification of the underlying cause(s) of neurodegeneration, and hinder the selection and development of appropriately targeted therapies. Definite diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases still depends on postmortem neuropathological examination which reveals the anatomical and cellular distributions of intracytoplasmic filamentous aggregates made of hyperphosphorylated tau protein.

In the adult human brain, six tau isoforms are expressed, being produced by alternative mRNA splicing of transcripts from MAPT. Inclusion of exon ten results in the production of three tau isoforms with four repeats each (4R), and its exclusion results in three additional isoforms with three repeats each (3R) [17, 19]. Some diseases with tau pathology, such as Alzheimer disease (AD) and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), result in the pathological accumulation of both 3R and 4R tau aggregates (3R/4R tau pathology). Other diseases are associated with aggregation of either 3R (e.g., Pick disease) or 4R tau [e.g., progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and corticobasal degeneration (CBD)]. The tauopathies associated with mutations in the MAPT gene, and formerly grouped under the name of frontotemporal dementia and Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 MAPT (FTDP-17 MAPT), have clinical and pathological phenotypes that differ according to the exonic or intronic MAPT mutations. In fact, depending on the type of MAPT mutation, tau aggregates are made of 3R-, 4R-, or 3R/4R isoforms. The pathological tau deposits are made of different aberrant assemblies of tau that can propagate faithfully by apparent seeded polymerization mechanisms in cellular or in vivo systems [7, 18, 19, 24, 25, 31, 40, 50]. In this process, tau filaments, or even monomers [29, 42], appear to act as templates that guide the refolding of tau molecules as they add on to elongating filaments. In vitro studies have shown that different types of tau seeds can preferentially induce the fibrillization of 3R monomers, 4R monomers, or both [8].

For AD, CTE, and Pick disease, distinct cryo-electron microscopy-based tau filament amyloid core structures have been solved that could explain different seeding/templating activities. Specifically, the cores of paired helical and straight tau filaments from AD brain tissue are comprised of paired protofilaments containing stacks of either 3R and 4R tau molecules assembled in parallel in-register β-sheets [11, 13]. In contrast, the tau filaments of Pick disease, a 3R tauopathy, have conformationally distinct parallel in-register β-sheets of 3R tau [11]. These structures exemplify how incoming tau monomers adopt the conformations of the filament cores in a manner analogous to that proposed for prion strains [4, 22, 45, 48].

Given that pathologic forms of tau and other proteins such as prion protein, amyloid β, and α-synuclein characterize the various proteinopathies, the ability to detect them with high sensitivity and selectivity in patients’ tissues or fluids as biomarkers can be helpful in diagnostics. Indeed, our group and others have exploited seeded polymerization propagation mechanisms to obtain cell-free reactions that allow highly amplified detection of some types of disease-associated protein aggregates in human specimens such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [2, 10, 23, 33, 41, 49], nasal brushings [32, 36], urine [30], skin [35], or eyes [34]. In these assays, diseased tissue or fluid containing miniscule amounts of a given self-propagating protein aggregate (the seed) is incubated in a vast excess of recombinant monomers of the same, or similar, protein (the substrate) in multiwell plates. Over time, the aggregates incorporate the substrate to grow exponentially into recombinant amyloid fibrils that can then be detected using an amyloid-sensitive fluorescent dye, e.g., thioflavin T (ThT). For prion diseases [2, 5, 14], AD [39], and synucleinopathies such as Parkinson disease and dementia with Lewy bodies [10, 23, 41], seed amplification assays such as real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC) have provided promising new diagnostic and exploratory tools.

Recently, we have developed ultrasensitive RT-QuIC assays with preferential detection of either the 3R tau forms of Pick disease [37] or the 3R/4R tau forms of AD and CTE [26]. Here, we report development of a tau RT-QuIC for 4R tauopathies, specifically PSP, CBD, and FTDP-17 MAPT. A key novel feature of this particular tau RT-QuIC assay is an ability to detect disease-associated subtypes of 4R tau seeds as indicated by differences in their conformational templating of the fibrillar tau products of 4R RT-QuIC. Also, with respect to diagnostic potential, this new 4R RT-QuIC assay is the first cell-free assay to detect pathological tau seeds in intra-vitam CSF.

Materials and methods

Recombinant tau protein expression and purification

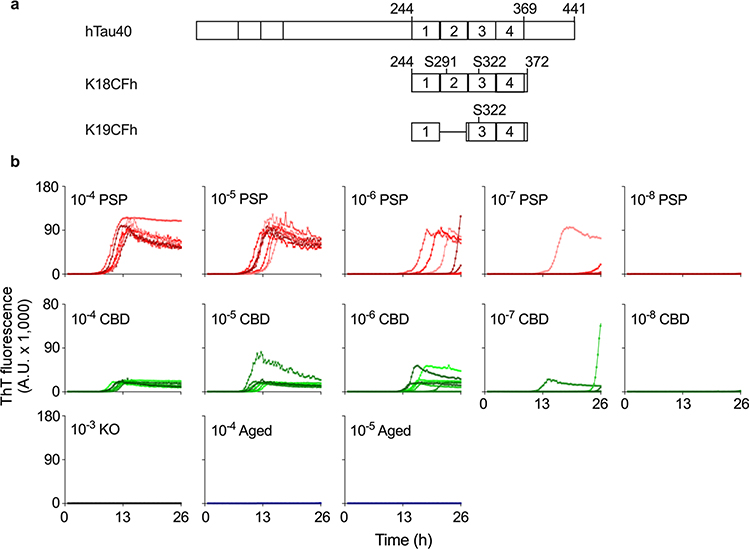

We used a 4R K18 construct called K18 cysteine-free (K18CFh) with mutations at residues 291 and 322 cysteine to serine [8, 47] and a poly-histidine tag and a 3R K19 construct called K19 cysteine-free (K19CFh) with a mutation at residue 322 cysteine to serine [8, 15, 16] and a poly-histidine tag [37] (Fig. 1a). These tau recombinant proteins were purified according to the protocol described previously [37, 38] (see K18CFh tau chromatograms in Online Resource Fig. 1) and stored frozen at − 80 °C. The tau substrates were thawed immediately before use in RT-QuIC reactions and filtered with a 100 kDa spin column filter (Pall, OD100C35) to remove any possible aggregates.

Fig. 1.

a Schematics of truncated and mutated tau RT-QuIC substrates relative to full-length human tau isoform (hTau40). The poly-histidine tags on K18CFh and K19CFh are not depicted. b End-point dilution 4R RT-QuIC analysis of PSP and CBD brain tissue. The designated dilutions of brain tissue from a human PSP (#12, top), CBD (#1, middle), and non-demented aged individuals (#2, bottom) were tested. Also shown was simultaneous testing of brain from tau-free KO mouse (bottom). Individual traces from eight replicate reactions are shown in each panel

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis

Samples were analyzed using previously described protocols [37]. Non-specific staining of proteins in gels was performed with GelCode Blue Safe Protein Stain (Thermo Scientific, 24594) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. To detect tau, a primary tau antibody (0.1 μg/ml, rabbit polyclonal, Abcam, 64193) was used.

Preparation of brain homogenates

The Dementia Laboratory of Department of Pathology at Indiana University School of Medicine provided frozen frontal cortex brain samples obtained postmortem from neuropathologically confirmed cases of senile change, cerebrovascular disease, diffuse Lewy body disease, multiple system atrophy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), primary age-related tauopathy (PART), Pick disease, PSP, CBD, AD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP 43 (FTLD-TDP), and FTDP-17 MAPT with IVS10 + 3G > A mutation. Tau knockout (KO) mice were obtained from Jackson laboratory [46]. Additional frozen brain samples of the superior frontal gyrus from PSP, CBD, FTDP-17 with N279K, P301L mutations, and neuropathologically normal control cases were provided by Mayo Clinic (Jacksonville, FL). Demographics and clinical diagnosis of each case are summarized in Online Resource Table 1. CTE samples were from previously described cases [9, 12, 26]. For test samples, brain tissue was homogenized to give 10% (w/v) in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4 using a multi-bead shocker (Fisher). Supernatants from 2 min spins at 2000 × g were collected and stored at − 80 °C until use. A modified protocol was employed to prepare the mouse KO brain homogenates that were used to dilute the test sample homogenates as described below. The mice were maintained under pathogen-free conditions at an American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care accredited animal facility at the NIAID and housed in accordance with the procedures outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under an animal study proposal approved by the NIAID Animal Care and Use Committee (ASP # 2016–058).

CSF samples

Postmortem PSP, CBD, and unaffected control CSF were obtained from the NIH NeuroBioBank. Intra-vitam PSP, CBD, AD, multiple system atrophy, CNS lymphoma, and meningeal carcinomatosis CSF samples were obtained from University of Bologna where specimens were collected with institutional permission to use for research purposes which the clinical data acquired from patients as health care providers, as well as the informed consent from the patients to use the leftover of the diagnostic samples for research studies. Blinded intra-vitam CSF samples including PSP, corticobasal syndrome (CBS), and AD were obtained from University of California, San Francisco with PPG IRB approval (#10–03946). These samples were used at NIH under OHSRP Exemption #19-NIAID-00774. Further intra-vitam CSF samples from Parkinson disease, Alzheimer disease, primary progressive aphasia, and non-neurological control cases were obtained from University of California, San Diego with UCSD IRB approval (#80012) and tested by NIH under OHSRP exemption 13461. Intra-vitam PSP, CBD, AD, multiple system atrophy, DLB, LBD, and rapidly progressive dementia (PPA) CSF samples were obtained from University of Verona. Additional intra-vitam AD and non-disease control CSF were purchased from Precision-Med. Pooled healthy human CSF was purchased from Innovative Research.

Sarkosyl extraction of tau aggregates

A previously described protocol was used to isolate sarkosyl-insoluble tau from human brain tissues [20]. The resulting sarkosyl-insoluble pellet was rinsed with PBS and resuspended in 1 × PBS pH 7.4 (0.2 ml per gram of starting material) and stored at − 80 °C.

4R RT-QuIC assay

Reactions were prepared in a biological safety cabinet using aerosol-resistant tips to prevent cross-contamination. Brain homogenate test samples were diluted in seed dilution buffer containing 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 0.017× N-2 supplement (Gibco, 17502–048), 0.5% KO brain homogenate. The latter was used to maintain consistent overall biomass in serial dilutions of brain homogenate test samples. Importantly, as noted above, the KO brain homogenate used for sample dilution was prepared differently than that used for brain test samples: the KO brain tissue was homogenized in 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 25 mM Tris–HCl, and pH 7.4 (when at room temperature) with an EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). In a 384-well optical BTM Polybase Black plate (Thermo Scientific, 242764), 2 μL of each brain homogenate dilution was added to 48 μL of brain 4R RT-QuIC reaction buffer containing 7.5 μM K18CFh and 3.75 μM K19CFh (a total of 11.25 μM) monomers, 90 μM poly-glutamate (Sigma, P1818), 40 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 300 mM sodium citrate, and 10 μM thioflavin T (ThT). After the plate was covered with sealing tape (Nunc, 236366), it was incubated at 37 °C in a plate reader (BMG Labtech FLUOstar Omega) with intermittent shaking, consisting of 60 s of orbital shaking at 500 rpm and no shaking for 60 s. Shaking was paused for 3.5 min to measure fluorescence every 15 min by bottom reading using 450–10 nm excitation and 480–10 nm emission. Instrument gains were set at below 600 relative fluorescence units (rfu) to allow less frequent saturation of the detector. The addition of a 0.8 mm silica bead (OPS Diagnostics, BMBG 800–200-02) per well in a 384-well plate prior to addition of brain 4R RT-QuIC reaction buffer accelerated templated fibril formation and was used for end-point dilution analysis of 4R brain homogenates.

For analysis of CSF, undiluted samples were first sonicated for 8 s at a power setting of 3 on a Misonix 3000 cuphorn sonicator, placed on ice, while others were sonicated and then added at 12 μL per well to a poly-d-lysine-coated 384-well plate (Thermo Scientific, 152029). The plate was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C prior to the addition of 38 μL of CSF 4R RT-QuIC reaction buffer containing 7.5 μM K18CFh and 3.75 μM K19CFh (a total of 11.25 μM) monomers, 90 μM poly-glutamate (Sigma, P1818), 20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 20 mM phosphate from 1x PBS pH 7.4 (20 mM sodium phosphate, 13 mM sodium chloride), 300 mM sodium citrate, and 10 μM thioflavin T (ThT). A single 1 mm glass bead (BioSpec Products, 11079110) was added to each well in the 384-well plate after incubating with CSF and before adding the CSF 4R RT-QuIC reaction buffer. CSF samples were tested without dilution, unless otherwise indicated in which case pooled healthy human CSF was used as the diluent. For each CSF test sample, three or four technical replicate reactions (unless otherwise indicated) were prepared in the 384-well plate to give a final total volume of 50 μL. The reaction plates were incubated in a plate reader and read as described in the preceding paragraph for brain homogenate samples.

4R RT-QuIC data analysis

Graph Pad Prism 8 was used to plot and analyze the RT-QuIC data. ThT fluorescence was recorded in rfu with saturation occurring at 260,000. For brain homogenate and synthetic tau fibril test samples, reactions were considered positive if the ThT fluorescence exceeded a threshold calculated as the average of mean baseline readings over the 2–7 h time window in the traces for the human samples in the given experiment plus 100 times the standard deviation of those readings (e.g., 387 + 3194 = 3582 rfu). Results were assessed within 60 h, except in designated reactions that included a bead, in which case ≤ 30-h time point was used due to the overall accelerating effect of the bead. This decision point was selected, because when reactions were allowed to extend beyond 60 h (or 30 h with a 0.8 mm silica bead), occasional negative control KO samples gave responses exceeding the threshold, suggesting that negative control KO samples can eventually allow spontaneous (tau aggregate-independent) K18CFh and/or K19CFh fibrillization. For CSF test samples, reactions were judged to be positive when the baseline-subtracted peak fluorescence exceeded an arbitrary threshold reading of 1500 rfu. This threshold was chosen empirically and provisionally as one that best distinguished intra-vitam CSF samples from patients clinically diagnosed as having PSP, CBD, or CBS from the others. Positive/negative assessments were made within 40 h for postmortem CSF or within 36 h for intra-vitam CSF. Statistical significance of differences in groups of baseline-subtracted peak fluorescence values was assessed with one-way ANOVA followed by an uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test using a significance level of 0.01 to generate the P values. CSF-seeded reactions were compared using values from individual replicates from all experiments. To assess statistical significance of differences in fractions of positive/total replicate wells, Fisher’s exact test was used.

Immunodepletion analysis

Serial immunodepletions were performed on PSP 5 brain homogenate using Dynabeads Protein G Immunoprecipitation kit (10007D, ThermoFisher Scientific) and HT7 anti-tau antibody (MN1000, ThermoFisher Scientific) as directed by the manufacturer’s protocol with minor modifications. Briefly, 0.75 mg of beads were conjugated with 2 μg of anti-tau IgG antibody HT7 or IgG control (14–4714-81, ThermoFisher Scientific) in 0.01% bovine serum albumin (BSA), PBS pH 7.4 (PBS-B) for 15 min with constant rotation at room temperature. Non-specific binding to beads was blocked by BSA. After washing with 200 μL of PBS-B, 500 μL of 10 −4 PSP brain homogenate in PBS-B was incubated with bead–antibody complexes for 26 min at constant rotation at room temperature. Bead–antibody–antigen complexes were isolated with a magnet, and 20 μL of supernatant (immunodepleted sample) was saved to test in 4R RT-QuIC. Bead–antibody–antigen complexes were resuspended in 20 μL of the manufacturer’s proprietary elution buffer and incubated for 2 min at room temperature, with eluant saved for 4R RT-QuIC analysis. Each remaining supernatant was subjected to an additional round of immunodepletion/immune capture.

Preparation of synthetic seeds for sensitivity determination

To assess the analytic sensitivity of the 4R RT-QuIC, synthetic K18CFh and K19CFh tau seeds were generated by adding 90 μM poly-l-glutamate to 1 mL tubes containing 50 μM K18CFh and K19CFh, separately. Tubes were agitated for 60 h at 1000 rpm, 37 °C on a benchtop shaker. The fibrils were centrifuged at 13,200 × g for 10 min, and pellets resuspended in a volume equivalent of water for SDS-PAGE analysis for percent conversion. Both K18CFh and K19CFh reactions reached nearly complete aggregation as determined by comparison of pellets and supernatants. Synthetic fibrils were then serially diluted as described above for brain homogenate and seeded into the 4R RT-QuIC for determination of analytic sensitivity for pure 4R fibrils (K18CFh alone), pure 3R fibrils (K19CFh alone), and a 1:1 mixture of 4R and 3R fibrils. For CSF analytical sensitivity estimations, PSP CSF-seeded QuIC products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE gel as described above to determine percent conversion of substrates. PSP CSF-seeded synthetic fibrils were then serially diluted tenfold into healthy pooled CSF for determination of analytical sensitivity of 4R RT-QuIC for CSF specimens.

FTIR

RT-QuIC reaction products were recovered from 384-well plates by scraping the bottom of the well with a pipette tip and transferring the contents of 3–16 replicate reactions at 10−4 dilution. CSF reaction products were scraped and pooled from 3–7 replicate reactions of 12 μL CSF/well. Reactions contained identical conditions to those described in the 4R RT-QuIC section, and were stopped when ThT fluorescence reached a plateau, prior to spontaneous fibrillization in KO-seeded reactions between 15 and 30 h. Pooled samples were centrifuged at 13,200 × g for 10 min, 4 °C, supernatant discarded and pellets washed in 3 × 200 μL H2O. The final pellet was resuspended in 5–10 μL ddH2O for FTIR analysis. Pellet-H2O slurry (1.5 μL) was applied to a Perkin Elmer Spectrum 100 FTIR with diamond crystal ATR attachment. The samples were dried with air until the 3400 cm−1 H2O band stopped decreasing. For each sample, 20–100 scans were averaged from 4000 to 800 cm−1, 4 cm−1 step, strong apodization, with continuous purge of sample and electronic chambers with dry air. Spectra with excess contribution from water vapor or CSF protein matrix were discarded and repeated. Spectra were normalized to amide I intensity and second derivatives were taken with nine points for slope analysis.

Electron microscopy

Standard carbon 200 mesh copper grids with Formvar/carbon coat (Electron Microscopy Sciences, FCFT200-Cu) were glow discharged and incubated with fibril solutions for 15 min at room temperature. Grids were washed through five sequential milliQ water washes prior to being stained with Nano-W stain (Nanoprobes, 2018–5) and wicked dry. Images were acquired on a T12 (Thermo Fisher) transmission electron microscope operating at 120 kV with a Rio (Gatan) CMOS camera.

Results

4R RT-QuIC analysis of brain

We tested recombinant tau substrates, polyanionic cofactors, and other reaction conditions to develop a 4R RT-QuIC assay optimized for the detection of seeding activities present in brain tissue from individuals with 4R tauopathies. For example, as will be detailed in a separate report (Metrick et al., PNAS, in press), substitution of sodium citrate for the sodium chloride that was used in previous tau RT-QuIC assays markedly improved 4R RT-QuIC assay sensitivity. The main substrate (K18CFh) was a cysteine-free, histidine-tagged construct (Fig. 1a) derived from a 4R tau fragment called K18 [47]. A 3R construct called K19CFh [37] was added at half the concentration of K18CFh to help reduce the formation of spontaneous (unseeded) fibrils of K18CFh and improve assay sensitivity [26]. Representative PSP and CBD brain specimens could be diluted to 10−6–10−7 before losing positive responses from individual replicate reactions (Fig. 1). In contrast, 10−4–10−5 dilutions of brain from a non-demented aged human control and tau-free KO mouse brain gave no positive reactions. Immune capture experiments provided evidence that a majority of the seeds in PSP brain homogenate contained tau (Online Resource Fig. 2). Efficient seeding of the assay reaction was also seen with pure synthetic recombinant K18CFh tau fibrils, or K18CFh fibrils mixed with K19CFh fibrils in case there was any major interference between the two seeds, indicating a analytical sensitivity of ~ 50 fM or ~ 2 fg per 2-μL sample (Online Resource Fig. 3). Electron microscopy confirmed that the PSP-seeded reaction products were fibrillar (Online Resource Fig. 4), consistent with their ability to enhance ThT fluorescence. SDS-PAGE analysis of the fibrillar products of PSP- and CBD-seeded 4R RT-QuIC reactions indicated the preferential aggregation of K18CFh despite the presence of both K18CFh and K19CFh in the reactions (Online Resource Fig. 5). Collectively, these results showed that 4R RT-QuIC sensitively detects both 4R tauopathy-associated and synthetic 4R tau seeding activities that are capable of inducing the fibrillization of recombinant 4R tau fragments.

Quantitative comparison of brains from multiple tauopathy and non-tauopathy cases

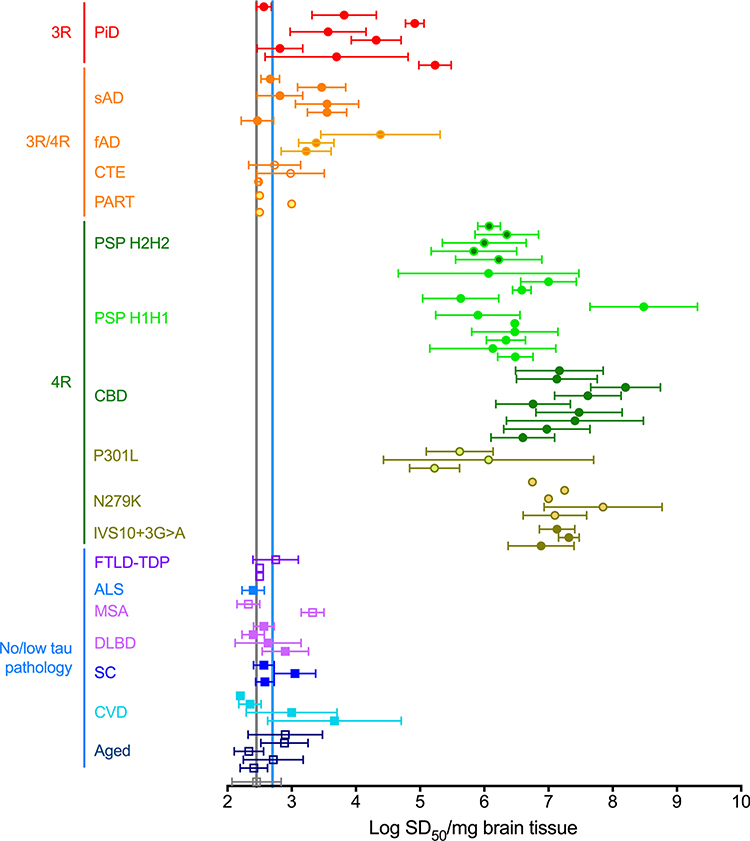

We compared seeding activities [in terms of log10 50% seeding units or doses ( SD50) per mg brain [49]] in superior frontal gyrus and frontal cortex samples from multiple types of tauopathy and apparent non-tauopathy cases (Fig. 2 and Online Resource Table 1). SD50 is defined as a unit of seeding activity that elicits positive reactions in 50% of replicate reactions under the given assay conditions [49]. Cases with predominant 4R tau pathology included PSP (n = 16), CBD (n = 9), FTDP-17 MAPT with the FTDP-17 MAPT with the P301L mutation (n = 3), FTDP-17 MAPT with the N279K mutation (n = 5) and IVS10 + 3G > A mutation, and predominant 4R tau deposition [43] (n = 3). These 4R cases had seeding activities that were 103–106-fold higher than the detection limit established by testing of tau KO mouse brain tissue. With PSP cases, both H1H1 (n = 11) and H2H2 (n = 5) MAPT haplotypes gave similarly high seeding activities (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Concentrations of seeding units (SD50s) in 4R tauopathy and other brain homogenates using 4R RT-QuIC analysis. Data points represent mean ± SD of multiple independent log SD50/mg brain determinations for individual cases with the designated diagnoses. Vertical grey and blue lines mark the average values from brains of tau KO mice and humans lacking immunohistochemical evidence of tau pathology, respectively. Case abbreviations: PiD pick disease, sAD sporadic AD, fAD familial AD, CTE chronic traumatic encephalopathy, PART primary age-related tauopathy, PSP progressive supranuclear palsy, CBD corticobasal degeneration, P301L frontotemporal dementia with Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 MAPT (FTDP-17 MAPT) with P301L mutation, N279K FTDP-17 MAPT with N279K mutation, IVS10 + 3G > A FTDP-17 MAPT with IVS10 + 3G > A mutation, FTLD-TDP frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43, ALS amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, MSA multiple system atrophy, DLBD diffuse Lewy body disease, SC senile changes (non-tau-associated), CVD cerebrovascular disease

In contrast, seeding activities in brain with 3R/4R tau pathology from sporadic AD (n = 6), familial AD (n = 3), CTE (n = 3), and PART (n = 3) cases ranged from undetectable to ~ 102-fold above the detection limit. Pick disease cases (n = 8) were more variable, with 4R RT-QuIC seeding activities ranging from essentially undetectable to levels that overlapped the low end of the range found for cases with 4R tau pathology by immunohistochemistry. Although Pick disease is known primarily as a 3R tauopathy, Pick disease-seeded aggregates formed under the 4R RT-QuIC conditions were predominantly comprised of the 4R substrate K18CFh, rather than the 3R substrate K19CFh (Online Resource Fig. 5). This suggested that some Pick disease cases may have 4R, as well as 3R, tau seeding activity, consistent with previous reports of both 3R and 4R tau deposits in some Pick disease cases [51]. Most aged or neurological control cases with non-tauopathy primary diagnoses had little to no detectable seeding activity. Given that tau RT-QuIC assays can be more sensitive than immunohistochemistry [26, 37], it is possible that tissue samples may contain tau seeds that are only detectable by tau RT-QuIC. Overall these results indicated strong 4R tauopathy selectivity with the 4R-optimized assay. This 4R selectivity was markedly different from the 3R and 3R/4R seed selectivities of our previous 3R- and AD-optimized RT-QuIC assays [26, 37], respectively.

Comparison of templating activities of different brain-derived seeds

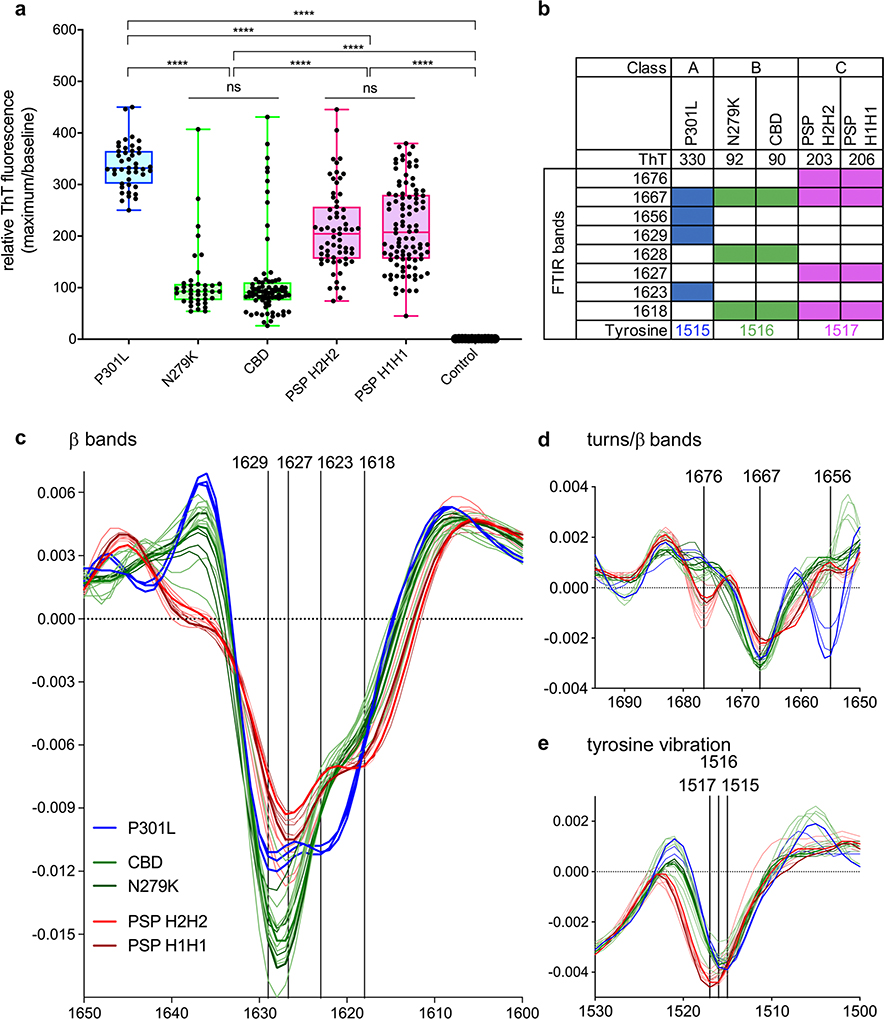

To test the possibility that various disease-associated types of 4R tau seeds differed in conformation, and thereby templating activity, we compared ThT fluorescence amplitudes and FTIR spectra of RT-QuIC products seeded by various brain samples. The fluorescence yields of ThT can depend on the seed-dependent conformations and ultrastructures of amyloid fibrils [14, 23], and FTIR spectra of amyloid fibrils are sensitive to differences in protein secondary structure [3, 6]. We observed three basic patterns in these parameters that indicated three distinctive types of 4R tau seeds (Classes A–C as designated in Fig. 3 and Online Resource Table 2). Class A was exemplified by the P301L mutation. Class B represented the N279K mutation and CBD. Class C was exemplified by PSP and one of five CBD cases. The relative ThT amplitudes obtained with different types of brain samples were largely independent of initial seed concentration and remained after the reactions had plateaued (e.g., compare PSP and CBD dilution series in Fig. 1). This, and the FTIR spectral variations, provided evidence that there were qualitative differences between the designated classes of RT-QuIC reaction products. This, in turn, suggested that three distinct 4R tau conformers (Classes A–C) in brain were propagated with at least partial conformational fidelity by 4R RT-QuIC.

Fig. 3.

ThT maxima and FTIR reveal three distinct RT-QuIC products from 4R tauopathy subtypes. a Points represent maximum relative ThT fluorescence (rfu) values (maximum/baseline) for 4R tauopathy seeded RT-QuIC reactions. Boxes represent interquartile range around the median and whiskers represent the maximum and minimum values; ****p < 0.0001, ns non-significant. b Summarized FTIR banding patterns from RT-QuIC products in panel a, filled boxes represent the presence of a band. c–e Second derivative FTIR spectra of RT-QuIC products from individual subject brain homogenates (individual traces); traces of same color indicate cases of the same type of tauopathy. Each trace represents 4–8 pooled RT-QuIC reaction wells seeded with an individual brain homogenate at 10−4 dilution for the specified 4R tauopathy

Comparison of banding profiles of insoluble tau in brain homogenates

We observed further evidence for disease-associated differences between the tau aggregates in brain by immunoblot analyses of ultracentrifuged pellets from either sarkosylextracted or unextracted brain homogenates. Using an antibody to tau residues 259–266, the CBD and N279K and P301L showed three tau bands at 64, 68, and 72 kDa. However, the 72 kDa band was absent or much weaker in PSP extracts (Online Resource Fig. 6, Online Resource Table 2). These distinctive immunoblot banding features were consistent within the 4R seed Classes A–C and thus were added to the 4R class descriptors defined in Online Resource Table 2.

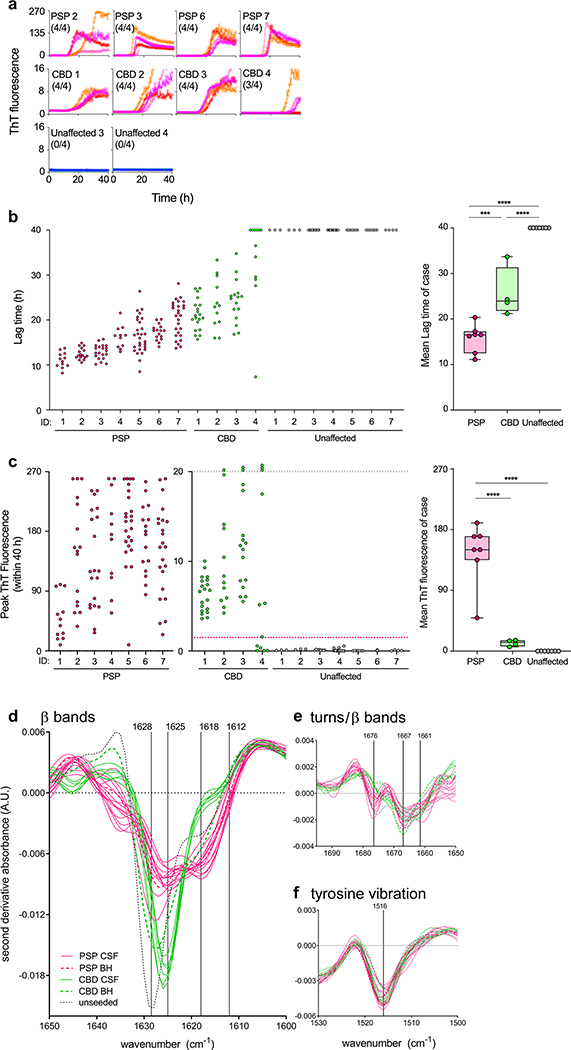

4R RT-QuIC analysis of postmortem CSF

Considering that CSF might be collected postmortem in lieu of a full brain dissection for the analysis of disease biomarkers for cause-of-death assessments, we first tested postmortem ventricular CSF from pathologically confirmed cases and unaffected controls (Fig. 4). In further optimizing the assay for CSF samples, we found that the use of poly-lysine-coated plates and a bead improved sensitivity (Online Resource Fig. 7). Under such conditions, the analytical sensitivity for initially PSP-seeded synthetic recombinant 4R RT-QuIC reaction products diluted into healthy pooled human CSF was ≤ 7.5 fM or ~ 0.3 fg per 12 μL sample. The PSP CSFs (n = 7) gave shorter lag times and higher peak fluorescence values than the CBD (n = 4) and unaffected control CSFs (n = 7) (Fig. 4a–c). The CBD samples gave significantly shorter lag times than the unaffected controls. Echoing what we saw with brain samples (Figs. 1b, 3a), there were striking differences in the peak ThT fluorescence values obtained in reactions seeded with PSP versus CBD CSF (note the > 16-fold higher fluorescence scales for the PSP reactions on the left in Fig. 4a, c). Moreover, FTIR analyses of PSP- and CBD-seeded RT-QuIC products revealed spectral differences in β sheet and turn/β band regions (Fig. 4d, e) that were mostly consistent with those seen with brain-seeded reaction products (Fig. 3c–e). End-point dilutions of 4 postmortem PSP CSF samples indicated that while one could be diluted 100-fold and still give 4/4 positive replicate reactions, others lost positivity at lesser dilutions (Online Resource Fig. 8). Thus, these CSF samples had orders of magnitude lower seeding activities than seen in corresponding types of brain samples. Altogether these results showed that 4R RT-QuIC seeding activity was readily detected in postmortem ventricular CSF samples from PSP and CBD decedents, and that the disease-dependent templating activities of these seeding activities largely recapitulated those seen with brain samples.

Fig. 4.

4R seeding activities detected in postmortem PSP and CBD CSF by 4R RT-QuIC. a CSF samples (12 μL) from PSP (n = 4), CBD (n = 4), and control (n = 2) cases, identified by their ID numbers from Online Resource Table 3, were analyzed by 4R RT-QuIC. Traces from individual quadruplicate reactions are plotted with ThT rfu indicated in thousands. The fraction of the quadruplicate reactions with rfu exceeding 1500 rfu is shown in parentheses. b Lag times (time to 1500 rfu within 40 h) for each reaction from all samples tested is shown in the dot plot. Right graph: Data points show average lag times for each case with the designated diagnosis. Boxes indicate the median and interquartile range, and whiskers indicate the maximum and minimum case averages. Significance of differences between means by one-way ANOVA followed by uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test: ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. c Baseline-subtracted maximum rfu values. CBD and unaffected control cases were plotted in the middle with a smaller y-axis. Off-scale values exceeding 20,000 rfu are stacked above the grey dotted line. Magenta dotted line: 1500 rfu threshold. Box plots as described in b, but with peak rfu instead of lag times. d–f Second derivative ATR-FTIR analysis of 4R RT-QuIC products seeded with individual PSP (magenta), CBD (greens), and control (black) CSF samples. Dashed lines are typical brain homogenate (BH) RT-QuIC product spectra reported in Fig. 3c for comparison

In diagnostic applications of prion and synuclein RT-QuIC assays, it is typical to set thresholds for reaction positivity within reaction times that best discriminate positive and negative control reactions. Applying the threshold described in Materials and Methods to the data obtained from the postmortem CSF specimens, 130/130 (100%) and 55/60 (92%) of the individual PSP- and CBD-seeded reactions, respectively, were significantly higher than the 0/49 (0%) positive reactions from unaffected controls (Online Resource Table 3). An additional criterion that is often used in calling diagnostic specimens (rather than individual RT-QuIC reactions) positive or negative is that to be considered positive overall, at least one SD50 is detected in the sample, that is, ≥ 50% of replicate reactions be above the fluorescence threshold [23, 28, 32, 33]. Applying this criterion to the postmortem CSF specimens, all of the PSP and CBD CSFs were positive, giving preliminary nominal diagnostic sensitivities of 100% for each, while 0/7 unaffected controls were positive, giving a diagnostic specificity of 100%.

4R RT-QuIC analysis of intra-vitam CSF

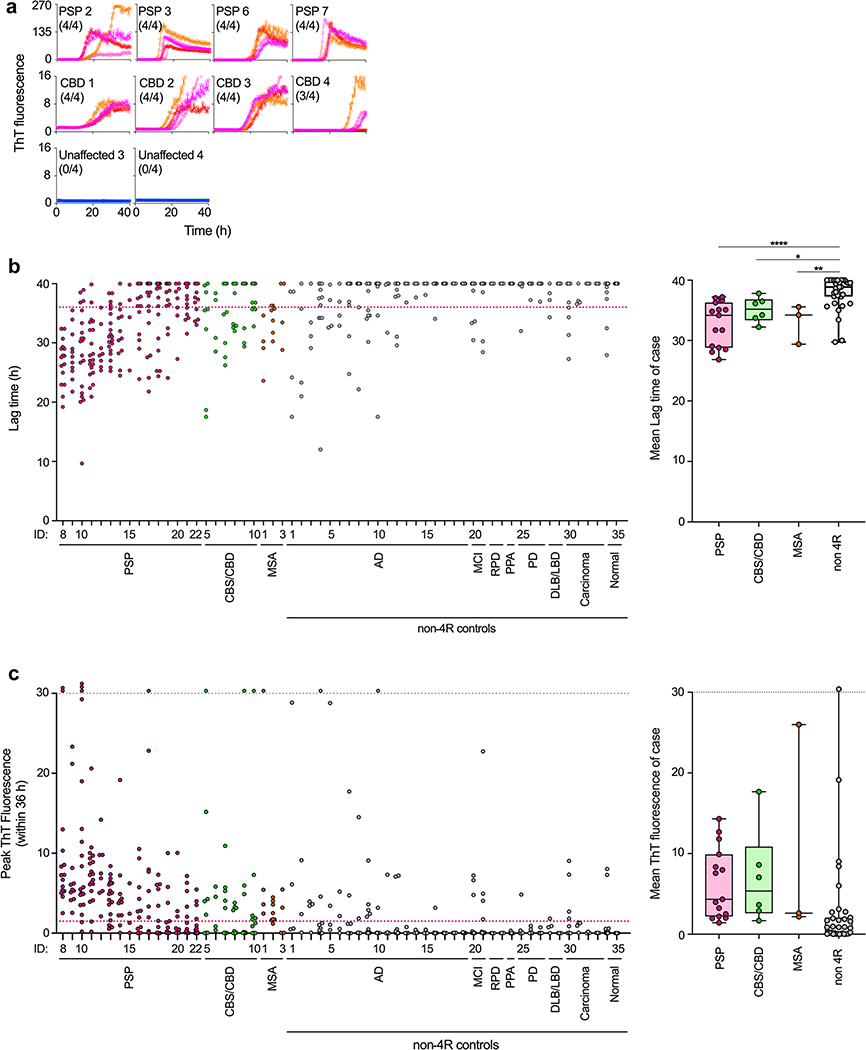

We then tested intra-vitam lumbar CSFs, considering that they can differ in composition from postmortem ventricular CSFs. We found that the 4R RT-QuIC responses from intra-vitam PSP and CBD/CBS CSF samples were much weaker than those of postmortem CSF samples (Fig. 5) consistent with previous observations of seeding detected by cellular assays [44]. We note that diagnosis of most of these cases was based on clinical criteria from living individuals without neuropathological confirmation, enhancing the possibility of misdiagnosis, and contributing to the preliminary and exploratory nature of our initial findings. Nonetheless, our clinically diagnosed PSP (n = 15) and CBD/CBS (n = 6) intra-vitam CSF samples gave significantly shorter lag times on average when compared to samples from normal controls who lacked clinical signs of neurological disease, or were diagnosed with neurological diseases that are not primary 4R tauopathies (n = 35) (Fig. 5b). We saw a range of PSP case RT-QuIC responses, which we have ordered with respect to lag times (fast to slow) in Fig. 5b. Interestingly, samples from three cases clinically diagnosed with multiple system atrophy were more consistently positive than the other non 4R controls, and as such, were not distinguishable statistically from the PSP or CBS/CBD cases. This might be due to the difficulty in accurately discriminating PSP, CBD and multiple system atrophy on a purely clinical basis [1, 21]. When we compared maximum ThT amplitudes, the mean values for the PSP and CBS/CBD cases were higher than those for the non 4R controls, but several outliers in the latter group eliminated statistical significance for the difference in means (Fig. 5c). Analysis of individual reaction positivity with respect to a fluorescence threshold indicated that 137/199 (69%) and 24/48 (50%) of PSP- and CBD/CBS-seeded reactions, respectively, were positive. These proportions were significantly higher than those obtained from the other groups, except for the multiple system atrophy cases (Online Resource Table 3). These results provided initial evidence that although 4R RT-QuIC seeding activities in intra-vitam CSF specimens from PSP and CBD/CBS subjects were much lower than in brain or CSF collected postmortem, the average assay responses were significantly faster than those obtained with intra-vitam CSFs from individuals who were not suspected of having 4R tau pathology.

Fig. 5.

4R seeding activities detected in intra-vitam PSP and CBD CSF by 4R RT-QuIC. a Representative CSF samples (12 μL) from PSP, CBD, AD, and non-neurological (normal) control cases, identified by their ID numbers from Online Resource Table 3, were analyzed by 4R RT-QuIC. Traces from individual quadruplicate reactions are plotted with ThT rfu indicated in thousands. The fraction of the quadruplicate reactions exceeding the 1500 rfu threshold is shown in parentheses. b Lag times (times to 1500 rfu within 40 h) for individual reactions seeded with CSF from the designated PSP, CBS/CBD, MSA, AD, MCI mild cognitive impairment, RPD rapidly progressive dementia, PPA primary progressive aphasia, PD Parkinson disease, dementia with Lewy bodies/Lewy body dementia (DLB/LBD), carcinoma and normal control cases (ID numbers on x-axis) were shown in the dot plot. Right graph: data points show average lag times for each case with the designated diagnosis. Boxes indicate the median and interquartile range, and whiskers indicate the maximum and minimum case averages. Significance of differences between means by one-way ANOVA followed by uncorrected Fisher’s LSD test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. c Baseline-subtracted rfu values within 36 h. Off-scale values exceeding 30,000 rfu are stacked above the grey dotted line. Magenta dotted line:1500 rfu threshold. Box plots as described in b, but for peak rfu values instead of lag times

Discussion

Here, we have demonstrated a practical, ultrasensitive method for selectively detecting pathologic 4R tau, and conformational subtypes thereof, in crude biospecimens. With the addition of this new assay, we now have complementary ultrasensitive and selective assays for each of the major types of pathological tau aggregates, namely 3R [37], 4R (present study), or combined 3R/4R [26]. Collectively, these seeded polymerization reactions emphasize the distinctive seeding or templating selectivity of different types of disease-associated tau, consistent with previous observations of prion strain-like propagation of distinct types of tau aggregates in cellular and animal models [18, 19, 24, 25, 31]. In our chemically defined cell-free RT-QuIC reactions, we have shown that preferences of various tau seeds for 3R, 4R, or mixed 3R/4R substrates can result in profound multi-log differences in seeding efficiencies, at least under the conditions that we have selected for optimal kinetic separation of seeded versus mock-seeded fibrillization. These distinct seeding activities appear to reflect differences in disease-associated tau filament composition and conformation, which, in a few cases, have been differentiated by cryo-electron microscopy [11, 13]. As was shown for prion strains, ordered protein aggregates can imprint their conformations on newly recruited monomers [4, 22, 45, 48], providing a mechanistic basis for the faithful conformer propagation in vitro and in vivo. Not only have we seen evidence for this in the overall selectivity of 4R tau seeds in the 4R RT-QuIC, but also in the ability of at least three different classes (A–C) of 4R tau seeds to template conformationally distinct 4R RT-QuIC products from the K18CFh tau substrate (Fig. 3, Online Resource Table 2).

The primary mechanistic bases for the profoundly different seeding selectivities of the 3R, 4R, and AD (3R/4R) RT-QuIC assays remain uncertain. In developing these assays, we often found it difficult to predict which conditions would work the best based on what was thought to occur in vivo. The primary goals of such assay optimization are practical and conflicting, namely, to encourage efficient polymerization of the substrate in the presence of a pathological tau seed in a biospecimen on one hand, while on the other discouraging spontaneous nucleation and polymerization when such seeds are lacking. The assays that best achieve these goals are not natural, nor do they fully recapitulate the pathological processes that occur in vivo. Highly influential compositional differences between these assays include the recombinant tau substrates, salts, and polyanionic cofactors. Not surprisingly, 3R RT-QuIC uses a modified 3R tau fragment, K19CFh, to be seeded by 3R (Pick disease) tau seeds [37]; the AD RT-QuIC uses a tau fragment that encompasses the amyloid core residues of AD-associated paired helical and straight filaments (306–378) [13, 26]; and our current 4R RT-QuIC includes a 4R tau substrate, K18CFh. More surprising was our observation that inclusion of K19CFh slowed the formation of spontaneous (unseeded) fibrils of K18CFh without blocking polymerization seeded by tauopathy specimens; This, in turn, improved 4R RT-QuIC sensitivity.

Also unexpected was the relatively poor seeding of K18CFh by AD and CTE seeds under our current 4R RT-QuIC conditions (Fig. 2). We can only surmise that one or more of the many conditions, cofactors, and K18-based substrate molecules that differ between intact cells and our simple cell-free reactions accounts for the differences in the selectivities of our respective experimental tau seed amplification systems.

The ability of 4R RT-QuIC to detect miniscule amounts of disease-associated tau seeding activity suggests that it may prove useful in measuring tau aggregates as relevant biomarkers in fundamental research, diagnostics, and the development of therapeutics for diseases involving 4R tau pathology. Coupling of 4R RT-QuIC with the 3R- and 3R/4R-optimized assays [26, 37], each with their respective multi-log selectivities, should aid the identification of the predominant form(s) of tau that have accumulated as seeds in specimens with enough seeding activity such as brain or postmortem ventricular CSF. This may facilitate the classification of tau-associated morbidities and co-morbidities in human decedents with neurodegenerative diseases, or in animal models of tau pathology.

Classification of 4R tau seeds by 4R RT-QuIC and FTIR of RT-QuIC products might help to increase the inter-rater reliability of postmortem pathologic diagnosis. Even with the established criteria, inter-rater disagreement of pathologic diagnosis is inevitable in neurodegenerative diseases [27]. Both PSP and CBD are 4R tauopathies characterized by neuronal and glial tau pathology. Tufted astrocytes and astrocytic plaques are morphologically different astrocytic lesions, which are pathologic hallmarks of PSP and CBD, respectively. In some cases, however, it is challenging to distinguish between the two lesions for pathologists. In this study, for instance, postmortem CSF from a CBD subject (CBD 1 in Online Resource Table 3) was initially provided to us as a sample from PSP case. After 4R RT-QuIC and FTIR instead indicated CBD, this case was re-evaluated by another neuropathologist blindly, and the diagnosis was changed to CBD due to the presence of astrocytic plaques and abundant tau-positive threads in the white matter regions.

Importantly, our study is the first demonstration of tau seeding activity in CSF collected from living patients by any type of tau RT-QuIC assay. We previously reported detection of 3R tau seeding activity in CSF collected postmortem from Pick disease decedents [37] and have been able here to detect 4R tau seeds in postmortem CSF from decedents with PSP and CBD (Fig. 4). However, we have not yet clearly detected seeds reliably in intra-vitam specimens from Pick disease individuals, providing evidence that postmortem ventricular CSF is not equivalent to intra-vitam lumbar CSF. Notably, the postmortem collection of ventricular CSF may allow more contamination with central nervous tissue. Interestingly a recent study of intra-vitam CSF from AD subjects reported detection of seed-competent tau aggregates using a cell culture-based seeding assay [44]. This raises the possibility that, with further assay development, tau seeds might also become detectable in intra-vitam AD CSF by the relatively high-throughput cell-free 3R/4R tau RT-QuIC assay. For now, our current data provide proof-of-concept that tau seeding activity can be detected in the CSF of living individuals with PSP and CBD. More extensive studies involving larger, more diverse and deeply characterized samples sets will be required to evaluate the clinical significance and diagnostic performance of 4R RT-QuIC testing. In particular, it will be important to evaluate matched sets of intra-vitam CSF samples and immunohistochemically characterized postmortem brain specimens from the same individuals, as they become available, to better establish the relationship between CSF tau seeding activity and brain tauopathy. Such information might not only improve the potential for intra-vitam diagnostics, but also justify longitudinal measurements of these 4R tauopathy-associated seeds as biomarkers during therapeutic trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank David Dorward and Cindi Schwartz of the NIAID Research Technology Branch for help with electron microscopy. We thank Drs. Suzette Priola, Ankit Srivastava, and Bradley Groveman for helpful internal review of the initial manuscript. This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIAID. MM is supported by the NIH/Cambridge Scholars program. B. G. was supported by a grant of the US National Institutes of Health (P30AG010133) and the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine. D. G. is supported by NIH grant AGO5131 and the Shiley-Marcos Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at UCSD. S. K. was supported by a research grant from the CBD Solutions. Some of the tissue specimens were obtained with support of the Massachusetts Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (P50 AG005134). We also acknowledge the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Kansas School of Medicine. Human tissue was obtained from the NIH NeuroBioBank. The UCSF Neurodegenerative Disease Brain Bank is supported by NIH Grants AG023501 and AG019724, the Tau Consortium, and the Bluefield Project to Cure FTD. LTG is funded by NIH K24053435. This study is also supported by Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Grant No. ZIA AI001086-08). SS is funded by NIH K08 AG052648.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-019-02080-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alster P, Nieciecki M, Koziorowski DM, Cacko A, Charzynska I, Krolicki L et al. (2019) Thalamic and cerebellar hypoperfusion in single photon emission computed tomography may differentiate multiple system atrophy and progressive supranuclear palsy. Medicine (Baltimore) 98:e16603 10.1097/MD.0000000000016603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atarashi R, Satoh K, Sano K, Fuse T, Yamaguchi N, Ishibashi D et al. (2011) Ultrasensitive human prion detection in cerebrospinal fluid by real-time quaking-induced conversion. Nat Med 17:175–178. 10.1038/nm.2294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron GS, Hughson AG, Raymond GJ, Offerdahl DK, Barton KA, Raymond LD et al. (2011) Effect of glycans and the glycophosphatidylinositol anchor on strain dependent conformations of scrapie prion protein: improved purifications and infrared spectra. Biochemistry 50:4479–4490. 10.1021/bi2003907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bessen RA, Kocisko DA, Raymond GJ, Nandan S, Lansbury PT Jr, Caughey B (1995) Nongenetic propagation of strain-specific phenotypes of scrapie prion protein. Nature 375:698–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bongianni M, Orrù CD, Groveman BR, Sacchetto L, Fiorini M, Tonoli G et al. (2017) Diagnosis of human prion disease using real-time quaking-induced conversion testing of olfactory mucosa and cerebrospinal fluid samples. JAMA Neurol 74:1–8. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.4614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caughey B, Raymond GJ, Bessen RA (1998) Strain-dependent differences in beta-sheet conformations of abnormal prion protein. JBiolChem 273:32230–32235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung DC, Carlomagno Y, Cook CN, Jansen-West K, Daughrity L, Lewis-Tuffin LJ et al. (2019) Tau exhibits unique seeding properties in globular glial tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol Commun 7:36 10.1186/s40478-019-0691-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinkel PD, Siddiqua A, Huynh H, Shah M, Margittai M (2011) Variations in filament conformation dictate seeding barrier between three- and four-repeat tau. Biochemistry 50:4330–4336. 10.1021/bi2004685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drachman DA, Newell KL, Scully RE, Mark EJ, McNeely WF, Ebeling SH et al. (1999) A 67-year-old man with three years of dementia—multisystem neurodegenerative disease (characterized by neurofibrillary changes and few plaques), findings consistent with dementia pugilistica. New Engl J Med 340:1269–1277. 10.1056/Nejm199904223401609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fairfoul G, McGuire LI, Pal S, Ironside JW, Neumann J, Christie S et al. (2016) Alpha-synuclein RT-QuIC in the CSF of patients with alpha-synucleinopathies. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 3:812–818. 10.1002/acn3.338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falcon B, Zhang W, Murzin AG, Murshudov G, Garringer HJ, Vidal R et al. (2018) Structures of filaments from Pick’s disease reveal a novel tau protein fold. Nature 561:137–140. 10.1038/s41586-018-0454-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falcon B, Zivanov J, Zhang W, Murzin AG, Garringer HJ, Vidal R et al. (2019) Novel tau filament fold in chronic traumatic encephalopathy encloses hydrophobic molecules. Nature 568:420–423. 10.1038/s41586-019-1026-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzpatrick AWP, Falcon B, He S, Murzin AG, Murshudov G, Garringer HJ et al. (2017) Cryo-EM structures of tau filaments from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 547:185–190. 10.1038/nature23002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foutz A, Appleby BS, Hamlin C, Liu X, Yang S, Cohen Y et al. (2017) Diagnostic and prognostic value of human prion detection in cerebrospinal fluid. Ann Neurol 81:79–92. 10.1002/ana.24833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedhoff P, Schneider A, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E (1998) Rapid assembly of Alzheimer-like paired helical filaments from microtubule-associated protein tau monitored by fluorescence in solution. Biochemistry 37:10223–10230. 10.1021/bi980537d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedhoff P, von Bergen M, Mandelkow EM, Davies P, Mandelkow E (1998) A nucleated assembly mechanism of Alzheimer paired helical filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:15712–15717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghetti B, Oblak AL, Boeve BF, Johnson KA, Dickerson BC, Goedert M (2015) Invited review: frontotemporal dementia caused by microtubule-associated protein tau gene (MAPT) mutations: a chameleon for neuropathology and neuroimaging. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 41:24–46. 10.1111/nan.12213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibbons GS, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ (2019) Mechanisms of cell-to-cell transmission of pathological tau: a review. JAMA Neurol 76:101–108. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goedert M, Eisenberg DS, Crowther RA (2017) Propagation of tau aggregates and neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci 40:189–210. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-072116-031153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Cairns NJ, Crowther RA (1992) Tau proteins of Alzheimer paired helical filaments: abnormal phosphorylation of all six brain isoforms. Neuron 8:159–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greene P (2019) Progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, and multiple system atrophy. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 25:919–935. 10.1212/CON.0000000000000751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groveman BR, Dolan MA, Taubner LM, Kraus A, Wickner RB, Caughey B (2014) Parallel in-register intermolecular beta-sheet architectures for prion-seeded prion protein (PrP) amyloids. J Biol Chem 289:24129–24142. 10.1074/jbc.M114.578344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groveman BR, Orru CD, Hughson AG, Raymond LD, Zanusso G, Ghetti B et al. (2018) Rapid and ultra-sensitive quantitation of disease-associated alpha-synuclein seeds in brain and cerebrospinal fluid by alphaSyn RT-QuIC. Acta Neuropathol Commun 6:7 10.1186/s40478-018-0508-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo JL, Lee VM (2011) Seeding of normal tau by pathological tau conformers drives pathogenesis of Alzheimer-like tangles. J Biol Chem 286:15317–15331. 10.1074/jbc.M110.209296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufman SK, Sanders DW, Thomas TL, Ruchinskas AJ, Vaquer-Alicea J, Sharma AM et al. (2016) Tau prion strains dictate patterns of cell pathology, progression rate, and regional vulnerability in vivo. Neuron 92:796–812. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kraus A, Saijo E, Metrick MAI, Newell K, Sigurdson C, Zanusso G et al. (2019) Seeding selectivity and ultrasensitive detection of tau aggregate conformers of Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol 137:585–598. 10.1007/s00401-018-1947-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Litvan I, Hauw JJ, Bartko JJ, Lantos PL, Daniel SE, Horoupian DS et al. (1996) Validity and reliability of the preliminary NINDS neuropathologic criteria for progressive supranuclear palsy and related disorders. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 55:97–105. 10.1097/00005072-199601000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGuire LI, Peden AH, Orru CD, Wilham JM, Appleford NE, Mallinson G et al. (2012) RT-QuIC analysis of cerebrospinal fluid in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Ann Neurol 72:278–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mirbaha H, Chen D, Morazova OA, Ruff KM, Sharma AM, Liu X et al. (2018) Inert and seed-competent tau monomers suggest structural origins of aggregation. Elife. 10.7554/eLife.36584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moda F, Gambetti P, Notari S, Concha-Marambio L, Catania M, Park KW et al. (2014) Prions in the urine of patients with variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. N Engl J Med 371:530–539. 10.1056/NEJMoa1404401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Narasimhan S, Guo JL, Changolkar L, Stieber A, McBride JD, Silva LV et al. (2017) Pathological tau strains from human brains recapitulate the diversity of tauopathies in nontransgenic mouse brain. J Neurosci 37:11406–11423. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1230-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orru CD, Bongianni M, Tonoli G, Ferrari S, Hughson AG, Groveman BR et al. (2014) A test for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease using nasal brushings. New Engl J Med 371:519–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orru CD, Groveman BR, Hughson AG, Zanusso G, Coulthart MB, Caughey B (2015) Rapid and sensitive RT-QuIC detection of human Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease using cerebrospinal fluid. MBio. 10.1128/mBio.02451-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orru CD, Soldau K, Cordano C, Llibre-Guerra J, Green AJ, Sanchez H et al. (2018) Prion seeds distribute throughout the eyes of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease patients. MBio. 10.1128/mBio.02095-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orru CD, Yuan J, Appleby BS, Li B, Li Y, Winner D et al. (2017) Prion seeding activity and infectivity in skin samples from patients with sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Sci Transl Med 10.1126/scitranslmed.aam7785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Redaelli V, Bistaffa E, Zanusso G, Salzano G, Sacchetto L, Rossi M et al. (2017) Detection of prion seeding activity in the olfactory mucosa of patients with fatal familial insomnia. Sci Rep 7:46269 10.1038/srep46269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saijo E, Ghetti B, Zanusso G, Oblak A, Furman JL, Diamond MI et al. (2017) Ultrasensitive and selective detection of three-repeat tau seeding activity in Pick disease brain and cerebrospinal fluid. Acta Neuropathol 133:751–765. 10.1007/s00401-017-1692-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saijo E, Groveman BR, Kraus A, Metrick M, Orru CD, Hughson AG et al. (2019) Ultrasensitive RT-QuIC seed amplification assays for disease-associated tau, alpha-synuclein, and prion aggregates. Methods Mol Biol 1873:19–37. 10.1007/978-1-4939-8820-4_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salvadores N, Shahnawaz M, Scarpini E, Tagliavini F, Soto C (2014) Detection of misfolded Abeta oligomers for sensitive biochemical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Rep 7:261–268. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanders DW, Kaufman SK, DeVos SL, Sharma AM, Mirbaha H, Li A et al. (2014) Distinct tau prion strains propagate in cells and mice and define different tauopathies. Neuron 82:1271–1288. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shahnawaz M, Tokuda T, Waragai M, Mendez N, Ishii R, Trenkwalder C et al. (2017) Development of a biochemical diagnosis of parkinson disease by detection of alpha-synuclein misfolded aggregates in cerebrospinal fluid. JAMA Neurol 74:163–172. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.4547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma AM, Thomas TL, Woodard DR, Kashmer OM, Diamond MI (2018) Tau monomer encodes strains. Elife. 10.7554/eLife.37813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spillantini MG, Goedert M, Crowther RA, Murrell JR, Farlow MR, Ghetti B (1997) Familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia: a disease with abundant neuronal and glial tau filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:4113–4118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takeda S, Commins C, DeVos SL, Nobuhara CK, Wegmann S, Roe AD et al. (2016) Seed-competent HMW tau species accumulates in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s disease mouse model and human patients. Ann Neurol. 10.1002/ana.24716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Telling GC, Parchi P, DeArmond SJ, Cortelli P, Montagna P, Gabizon R et al. (1996) Evidence for the conformation of the pathologic isoform of the prion protein enciphering and propagating prion diversity. Science 274:2079–2082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tucker KL, Meyer M, Barde YA (2001) Neurotrophins are required for nerve growth during development. Nat Neurosci 4:29–37. 10.1038/82868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Bergen M, Barghorn S, Li L, Marx A, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM et al. (2001) Mutations of tau protein in frontotemporal dementia promote aggregation of paired helical filaments by enhancing local beta-structure. J Biol Chem. 10.1074/jbc.M105196200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wickner RB, Edskes HK, Gorkovskiy A, Bezsonov EE, Stroobant EE (2016) Yeast and fungal prions: amyloid-handling systems, amyloid structure, and prion biology. Adv Genet 93:191–236. 10.1016/bs.adgen.2015.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilham JM, Orrú CD, Bessen RA, Atarashi R, Sano K, Race B et al. (2010) Rapid end-point quantitation of prion seeding activity with sensitivity comparable to bioassays. PLoS Path 6:e1001217 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woerman AL, Aoyagi A, Patel S, Kazmi SA, Lobach I, Grinberg LT et al. (2016) Tau prions from Alzheimer’s disease and chronic traumatic encephalopathy patients propagate in cultured cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:E8187–E8196. 10.1073/pnas.1616344113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhukareva V, Mann D, Pickering-Brown S, Uryu K, Shuck T, Shah K et al. (2002) Sporadic Pick’s disease: a tauopathy characterized by a spectrum of pathological tau isoforms in gray and white matter. Ann Neurol 51:730–739. 10.1002/ana.10222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.