Abstract

Objectives:

Mortality concern is a frequent driver of care-seeking in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Data on mortality in IBS are scarce and population-based studies have been limited in size. We examined mortality in IBS.

Methods:

Nationwide, matched population-based cohort study in Sweden. We identified 45,524 patients with a colorectal biopsy at any of Sweden’s 28 pathology departments and a diagnosis of IBS 2002-2016 according to the National Patient Register, a nationwide registry of inpatient and outpatient specialty care. We compared mortality risk between these individuals with IBS and age- and sex-matched reference individuals (n=217,316) from the general population as well as siblings (n=53,228). In separate analyses, we examined the role of mucosal appearance for mortality in IBS. Finally, we examined mortality in 41,427 IBS patients without a colorectal biopsy. Cox regression estimated hazard ratios (HRs) for death.

Results:

During follow-up, there were 3,290 deaths in IBS (9.4/1000 person-years) compared to 13,255 deaths in reference individuals (7.9/1000 person-years); resulting in an HR of 1.10 (95% CI=1.05-1.14). After adjustment for confounders, IBS was not linked to mortality (HR=0.96; 95%CI=0.92-1.00). Risk estimates were neutral when IBS patients were compared to their siblings. Underlying mucosal appearance on biopsy had only a marginal impact on mortality, and IBS patients without colorectal biopsy were at no increased risk of death (HR=1.02; 95%CI=0.99-1.06).

Conclusions:

IBS does not seem to confer an increased risk of death.

Keywords: IBS, histopathology, death, cohort study

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) affects an estimated 10-15% of the population with substantial impacts on quality of life and work productivity.(1, 2) The diagnosis relies on symptom-based criteria: today defined by abdominal pain associated with altered bowel habits in the absence of other explanatory conditions,(3-5) but with slight variations in definition during the last 30 years.(6, 7)

Fear about the potential serious nature of bowel symptoms may underlie much of the explanation for seeking care for IBS versus not,(8) and community estimates suggest that more than half of IBS patients fear that their illness will shorten their lifespan.(9) While existing literature demonstrates no increased risk of mortality from IBS, the majority of studies have not been population-based,(10-13) and the largest studies so far followed <400 IBS patients.(14, 15)

Despite clear diagnostic criteria, most clinicians consider IBS a diagnosis of exclusion.(16) Indeed, more than 50% of patients with IBS will undergo colonoscopy at some point in their diagnostic workup given patient and provider fears over missing organic disease.(17) However the role of colonoscopy for predicting disease outcome has not been defined.

We used a nationwide histopathology register to examine the overall risk of death in a large cohort of individuals with IBS undergoing colorectal biopsy compared to matched reference individuals. In a secondary cohort, we examined mortality in IBS patients without biopsy.

METHODS

Source database

IBS patients were selected from the Epidemiology Strengthened by histopathology Reports in Sweden (ESPRESSO) study, a histopathology-based cohort consisting of 6.1 million gastrointestinal (GI) pathology reports collected across Sweden’s 28 pathology departments from 1965-2017.(18) Between 2015 and 2017, the cohort was assembled by collecting all Swedish histopathology data from gastrointestinal tract sites accompanied by information on date of biopsy, topography (location of biopsy), and morphology. Each biopsy sample is categorized according to an individual’s person identity number (PIN), and includes information on date of birth and sex. Through linkage with individual PINs, it is possible to follow individuals over time across available Swedish registers (see below), and link data to information on healthcare diagnoses according to International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes. The cohort contains 2.1 million unique individuals corresponding to 6.1 million histopathology data entries (accounting for multiple biopsies in one individual). Individuals with histopathology data are matched with up to five controls from the general population (without GI histopathology) as well as all first-degree relatives and first spouses to encompass a total study population of 13.0 million individuals.

Definition of IBS

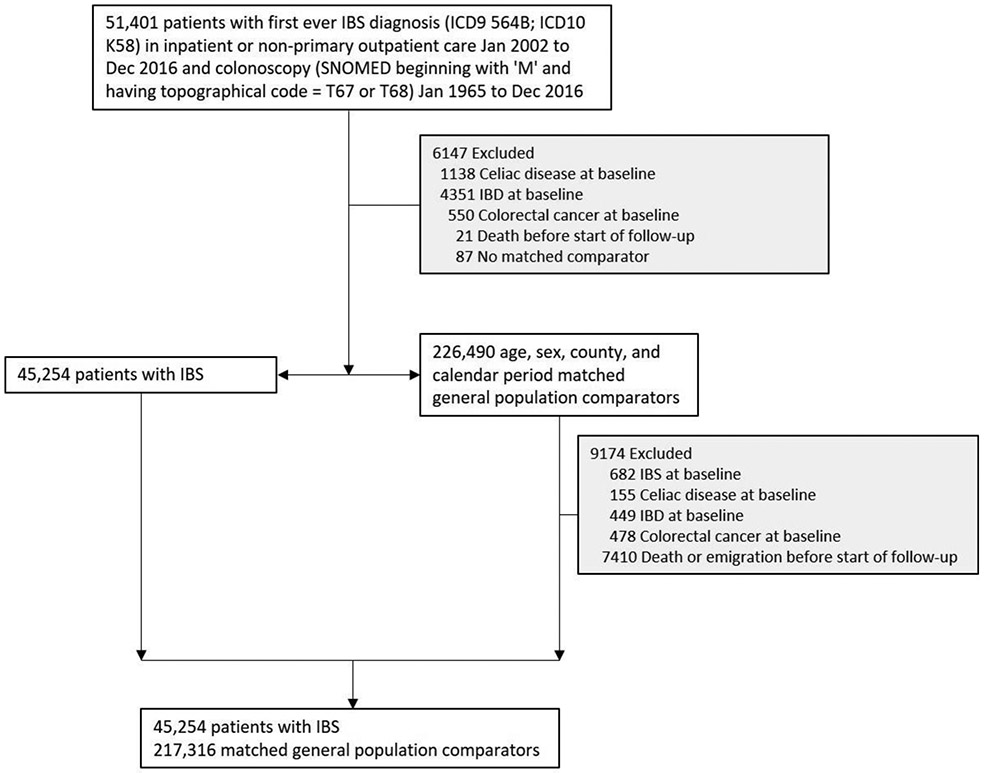

We first identified all individuals undergoing a colorectal biopsy (Table S1) in the ESPRESSO cohort. We used ICD codes to identify individuals within this cohort with a first-ever diagnosis of IBS (ICD-9 564B; ICD-10 K58) in inpatient or non-primary outpatient care 2002-2016 (Table S1) before or after colorectal biopsy. Both IBS patients and their reference individuals were excluded from all analyses if at baseline they had an earlier diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, or colorectal cancer (Table S1) since these disorders may lead to false-positive IBS diagnoses (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Flow chart of identified patients and their matched comparators

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; SNOMED, Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine

Patients with IBS were divided into those with diarrhea predominance (IBS-D) and those without diarrhea predominance (IBS non-D)(see ICD and SNOMED codes in Table S1). In secondary analyses, we did not restrict IBS patients to individuals who had undergone colonoscopy but identified IBS patients from the whole ESPRESSO study base (both biopsied individuals, reference individuals with no record of biopsy at date of matching, and first-degree relatives (regardless of biopsy status)).

Registers and covariates

Demographic data (dates of birth and death, immigration/emigration, sex, age, county of residence, and education) from all study participants were retrieved from the Total Population Register(19) and the longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labor market studies (LISA) using an individual’s PIN.(20) Data were linked to the Swedish Patient Register(21) to obtain data on inpatient and outpatient medical encounters. The diagnostic validity of the national patient register is generally 85-95%(21) with high validity seen for IBS diagnoses.(22)

Reference individuals

Index individuals with IBS were matched on age, sex, calendar year and county with up to five reference individuals from the Swedish general population.(19) Reference individuals had no GI biopsy prior to date of matching but could undergo biopsy thereafter. As controls were matched also for calendar year, they were subject to the same healthcare and access to medication as patients with IBS.

Siblings

IBS patients were also compared to their siblings. Siblings were identified through the Total Population Register. Sibling comparisons allowed us to examine the influence of intrafamilial confounding associated with shared genetic and early environmental factors on mortality in IBS.

Mortality data

Data on date of death were retrieved from the Total Population Register, which records almost all deaths within 30 days of occurrence.(19) Combined with comprehensive information on migration to and from Sweden, nearly all of the country’s population can be accounted for in medical research endeavors. Data on cause-specific mortality were obtained from the Swedish Cause of Death Registry(23) (covering >99% of all deaths) and cross-referenced with the Swedish Cancer Register(24) to evaluate deaths related to malignancies.

Covariates

Within the study population we determined medical comorbidities related to mortality in the last five years prior to study entry using ICD-10 codes prospectively recorded in routine clinical practice to determine presence of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, neurologic disease, and cancer (Table S2).

Statistical Analysis

Follow-up time started on latest of either a) first-ever IBS diagnosis or b) first colorectal biopsy (only individuals with both a medical IBS diagnosis and colorectal biopsy were eligible for case inclusion). The same date was used as index date for matched reference individuals so as not to introduce immortal time bias. Follow up ended with death, emigration, or December 31, 2017 (for cause-specific mortality, follow-up ended on December 31, 2016). We calculated mortality rate (death per 1000 person-years of follow-up) and used Cox regression to estimate unadjusted and multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for total and cause-specific mortality.

For our primary definition of IBS, we required a colorectal biopsy independent of its mucosal appearance. Using an alternative definition of IBS, we restricted our data to individuals with a normal mucosa (Table S1) to see what role a medical IBS diagnosis may play for the risk of death. In another analysis we examined IBS patients with normal mucosa and IBS patients with nonspecific colorectal inflammation separately (Table S1), to see if the underlying mucosal appearance could predict future mortality in IBS. Data on histopathology were obtained through ESPRESSO.(18) Inflammation was classified according to the recommendations from the Swedish quality and standardization committee for GI histopathology: KVAST.(25) To evaluate the influence of intrafamilial confounding, we compared IBS patients and their siblings. We also performed an analysis according to disease subtype (IBS-D and IBS non-D). We also performed an analysis using a more extensive exclusion criteria of IBS mimics, excluding those with a previous diagnosis of giardiasis, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, porphyria, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, sucrose-isomaltase deficiency, pelvic floor dysfunction, or microscopic colitis (Table S1).

Finally, because patients with IBS undergoing colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy with biopsy may represent a more severe subset of disease, we used an alternative definition of IBS in a separate analysis examining individuals with IBS who did not undergo colorectal biopsy compared to matched general population reference individuals.

All analyses were conditioned on matching factors (sex, age, county, year of biopsy), except in siblings where we conditioned on matching set within family. We further adjusted for baseline medical comorbidities (cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and neurologic disease) as well as for education since earlier research suggests an inverse relationship between education and seeking medical care(26) (and ascertainment of IBS) and mortality.(27) Because psychiatric disease could function as both a confounder and a mediator for IBS and mortality risk, we evaluated its presence and role in cause-specific mortality in all patient groups but did not adjust for it in our regression models. Statistics were carried out using SAS statistical software v9.4. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Confidence intervals for mortality rates were computed by assuming a Poisson distribution. The study was approved by the Stockholm Ethics Review Board. Informed consent was waived by the board since the study was strictly register-based.(28)

RESULTS

We identified 51,401 incident cases of IBS from 2002-16 undergoing colonoscopy (Figure 1). After exclusions there remained 45,254 IBS patients who were matched to 217,316 reference individuals (Figure 1).

On average the time interval between first IBS diagnosis and biopsy was 3.0 (SD 4.9) years. In 58% of patients (n=26,432), the biopsy took place <1 year before/after IBS diagnosis. Biopsies could occur both before or after IBS diagnosis. Table 1 shows the characteristics of study participants according to IBS status. Both IBS patients and matched reference individuals were predominantly female with a mean age in the mid-40s. Compared to matched reference individuals without IBS, IBS patients were more likely to be born in the Nordic countries and suffer from comorbidities. The median follow-up of study participants was 7.3 years (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study cohort

| Characteristic | Irritable bowel

syndrome (n=45,254) |

Matched

comparators (n=217,316) |

|---|---|---|

| Female, no. (%) | 32 029 (70.8%) | 153 817 (70.8%) |

| Male, no (%) | 13 225 (29.2%) | 63 499 (29.2%) |

| Age | ||

| Mean (SD) | 46.0 (18.3) | 45.3 (17.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 44.9 (30.3-60.5) | 44.2 (29.9-59.5) |

| Range, min-max | 0.2-99.8 | 0.0-99.9 |

| Categories, no. (%) | ||

| <18y | 1062 (2.3%) | 5386 (2.5%) |

| 18y - <30y | 10 012 (22.1%) | 49 349 (22.7%) |

| 30y - <40y | 7754 (17.1%) | 38 032 (17.5%) |

| 40y - <50y | 7614 (16.8%) | 37 157 (17.1%) |

| 50y - <60y | 7173 (15.9%) | 34 877 (16.0%) |

| 60y - <70y | 6495 (14.4%) | 30 692 (14.1%) |

| ≥70y | 5144 (11.4%) | 21 823 (10.0%) |

| Country of birth, no (%) | ||

| Nordic country | 40 805 (90.2%) | 187 422 (86.2%) |

| Other | 4449 (9.8%) | 29 889 (13.8%) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (0.0%) |

| Level of education, no (%) | ||

| ≤9 years | 8743 (19.3%) | 43 291 (19.9%) |

| 10-12 years | 21 067 (46.6%) | 95 852 (44.1%) |

| >12 years | 14 934 (33.0%) | 73 791 (34.0%) |

| Missing | 510 (1.1%) | 4382 (2.0%) |

| Start year of follow-up | ||

| 2002-2005 | 9708 (21.5%) | 47 036 (21.6%) |

| 2006-2010 | 15 963 (35.3%) | 76 779 (35.3%) |

| 2011-2016 | 19 583 (43.3%) | 93 501 (43.0%) |

| Time to register-based definition of IBS onset* (time in years between first IBS diagnosis and biopsy) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.0 (4.9) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.4 (0.0-4.0) | |

| Range, min-max | 0.0-45.1 | |

| Disease history within 5 years before start of follow-up, no. (%) | ||

| Cardiovascular disease (CVD) | 6826 (15.1%) | 16 453 (7.6%) |

| Myocardial infarction (MI) | 387 (0.9%) | 1216 (0.6%) |

| Cardiovascular disease in inpatient care | 2769 (6.1%) | 7605 (3.5%) |

| Cancer | 8121 (17.9%) | 19 090 (8.8%) |

| Cancer using the Cancer register only | 1797 (4.0%) | 5075 (2.3%) |

| Diabetes | 1132 (2.5%) | 3357 (1.5%) |

| Neurologic disease | 4711 (10.4%) | 10 679 (4.9%) |

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

Or time between biopsy and first IBS diagnosis (biopsy could occur before or after IBS diagnosis).

Table 2.

Risk of all-cause and cause specific mortality in patients with IBS and matched general population comparators

| All-cause mortality | CVD | Cancer | Psychiatric disease | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBS | Comparators | IBS | Comparators | IBS | Comparators | IBS | Comparators | |

| N | 45 254 | 217 316 | 45 254 | 217 316 | 45 254 | 217 316 | 45 254 | 217 316 |

| Deaths, no (%) | 3290 (7.3%) | 13255 (6.1%) | 1511 (3.3%) | 6079 (2.8%) | 1058 (2.3%) | 4147 (1.9%) | 346 (0.8%) | 1759 (0.8%) |

| Follow-up years | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.7 (4.1) | 7.7 (4.1) | 6.8 (4.0) | 6.8 (4.0) | 6.8 (4.0) | 6.8 (4.0) | 6.8 (4.0) | 6.8 (4.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 7.3 (4.3-10.9) | 7.3 (4.3-10.9) | 6.4 (3.4-10.0) | 6.4 (3.4-10.0) | 6.4 (3.4-10.0) | 6.4 (3.4-10.0) | 6.4 (3.4-10.0) | 6.4 (3.4-10.0) |

| Incidence rate per 1000 PY (95% CI) | 9.4 (9.1-9.7) | 7.9 (7.8-8.0) | 4.9 (4.7-5.1) | 4.1 (4.0-4.2) | 3.4 (3.2-3.6) | 2.8 (2.7-2.9) | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | 1.2 (1.1-1.2) |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.19 (1.15-1.24) | 1.19 (1.13-1.26) | 1.22 (1.14-1.31) | 0.94 (0.84-1.06) | ||||

| Conditioned | 1.10 (1.05-1.14) | 1.06 (1.00-1.13) | 1.16 (1.08-1.24) | 0.84 (0.74-0.95) | ||||

| Adjusted I | 1.12 (1.08-1.17) | 1.09 (1.03-1.16) | 1.18 (1.10-1.26) | 0.87 (0.77-0.98) | ||||

| Adjusted II | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) | 0.92 (0.87-0.98) | 0.93 (0.86-1.00) | 0.81 (0.71-0.92) | ||||

Conditioned: Conditioned on age, sex, county, and calendar period;

Adjusted I: Conditioned and further adjusted for level of education;

Adjusted II: Adjusted I and further adjusted for baseline medical comorbidities (cancer, diabetes, CVD, and neurologic disease)

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; CVD, cardiovascular disease; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range

Main results

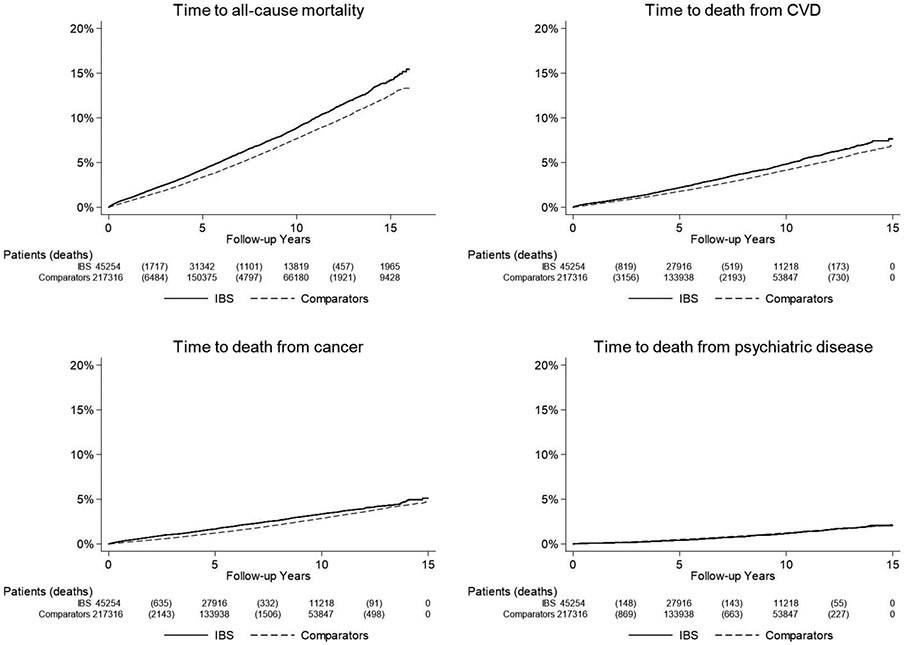

The crude incidence for death was higher in IBS (9.4 per 1,000 person-years) than in general population reference individuals who had not undergone biopsy at time of matching (7.9 per 1,000 person-years)(Table 2), as was the cumulative incidence over time presented using Kaplan-Meier estimators (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of time to all-cause mortality (follow-up until Dec 31, 2017) and cause-specific mortality (follow-up until Dec 31, 2016) in patients with IBS and matched comparators

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; CVD, cardiovascular disease

This translated into a 1.10-fold increased risk of death (95% CI=1.05-1.14)(Table 2). This positive association was completely attenuated after adjustment for potential confounders including education and baseline medical comorbidities (HR=0.96; 95% CI=0.92-1.00). All-cause mortality did not vary with follow-up time or comorbidity, but we found a small decreased risk of mortality in women with IBS (multivariable HR 0.92; 95%CI=0.99-0.97)(Table 3). Compared to age-matched reference individuals, individuals with younger IBS onset had somewhat increased mortality while mortality was decreased in groups of older IBS onset.

Table 3.

Risk of all-cause mortality overall and by subgroups in patients with IBS and matched general population comparators

| Group | N (%) | Time at risk (years) | N events | Incidence rate (95% CI) | HR* (95%CI) |

HR** (95%CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBS | Comparators | IBS | Comparators | IBS | Comparators | IBS | Comparators | |||

| Overall | 45 254 (100.0%) | 217 316 (100.0%) | 349 808 | 1 678 516 | 3290 (7.3%) | 13 255 (6.1%) | 9.4 (9.1-9.7) | 7.9 (7.8-8.0) | 1.10 (1.05-1.14) | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) |

| Follow-up | ||||||||||

| 0-<1y | 45 254 (100.0%) | 217 316 (100.0%) | 44 964 | 216 019 | 436 (1.0%) | 1370 (0.6%) | 9.7 (8.8-10.6) | 6.3 (6.0-6.7) | 1.35 (1.21-1.51) | 1.08 (0.96-1.21) |

| 1-5y | 44 737 (98.9%) | 214 755 (98.8%) | 184 141 | 883 250 | 1563 (3.5%) | 6258 (2.9%) | 8.5 (8.1-8.9) | 7.1 (6.9-7.3) | 1.09 (1.03-1.15) | 0.92 (0.87-0.98) |

| >5y | 31 342 (69.3%) | 150 375 (69.2%) | 150 205 | 720 824 | 1573 (5.0%) | 6771 (4.5%) | 10.5 (10.0-11.0) | 9.4 (9.2-9.6) | 1.05 (0.99-1.11) | 0.96 (0.91-1.02) |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Women | 32 029 (70.8%) | 153 817 (70.8%) | 248 657 | 1 192 278 | 2152 (6.7%) | 8951 (5.8%) | 8.7 (8.3-9.0) | 7.5 (7.4-7.7) | 1.05 (1.00-1.11) | 0.92 (0.88-0.97) |

| Men | 13 225 (29.2%) | 63 499 (29.2%) | 101 151 | 486 238 | 1138 (8.6%) | 4304 (6.8%) | 11.3 (10.6-11.9) | 8.9 (8.6-9.1) | 1.19 (1.11-1.28) | 1.03 (0.96-1.11) |

| Age# | ||||||||||

| <18y | 1062 (2.3%) | 5386 (2.5%) | 8 018 | 40 117 | 3 (0.3%) | 15 (0.3%) | 0.4 (0.0-0.8) | 0.4 (0.2-0.6) | 1.01 (0.29-3.53) | 1.33 (0.33-5.36) |

| 18y -<30y | 10 012 (22.1%) | 49 349 (22.7%) | 76 780 | 372 646 | 54 (0.5%) | 165 (0.3%) | 0.7 (0.5-0.9) | 0.4 (0.4-0.5) | 1.59 (1.17-2.17) | 1.53 (1.08-2.16) |

| 30y - <40y | 7754 (17.1%) | 38 032 (17.5%) | 63 575 | 307 415 | 88 (1.1%) | 239 (0.6%) | 1.4 (1.1-1.7) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 1.80 (1.40-2.30) | 1.67 (1.28-2.17) |

| 40y - <50y | 7614 (16.8%) | 37 157 (17.1%) | 62 118 | 302 417 | 163 (2.1%) | 578 (1.6%) | 2.6 (2.2-3.0) | 1.9 (1.8-2.1) | 1.41 (1.19-1.69) | 1.17 (0.97-1.42) |

| 50y - <60y | 7173 (15.9%) | 34 877 (16.0%) | 60 045 | 290 628 | 338 (4.7%) | 1688 (4.8%) | 5.6 (5.0-6.2) | 5.8 (5.5-6.1) | 0.96 (0.85-1.08) | 0.81 (0.71-0.92) |

| 60y - <70y | 6495 (14.4%) | 30 692 (14.1%) | 48 828 | 232 182 | 776 (11.9%) | 3273 (10.7%) | 15.9 (14.8-17.0) | 14.1 (13.6-14.6) | 1.13 (1.04-1.22) | 0.95 (0.88-1.04) |

| ≥70y | 5144 (11.4%) | 21 823 (10.0%) | 30 444 | 133 111 | 1868 (36.3%) | 7297 (33.4%) | 61.4 (58.6-64.1) | 54.8 (53.6-56.1) | 1.06 (1.00-1.12) | 0.94 (0.89-1.00) |

| Year# | ||||||||||

| 2002-2005 | 9708 (21.5%) | 47 036 (21.6%) | 125 911 | 605 930 | 1223 (12.6%) | 5375 (11.4%) | 9.7 (9.2-10.3) | 8.9 (8.6-9.1) | 1.03 (0.96-1.10) | 0.93 (0.87-0.99) |

| 2006-2010 | 15 963 (35.3%) | 76 779 (35.3%) | 142 257 | 681 993 | 1342 (8.4%) | 5450 (7.1%) | 9.4 (8.9-9.9) | 8.0 (7.8-8.2) | 1.08 (1.02-1.15) | 0.94 (0.88-1.01) |

| 2011-2016 | 19 583 (43.3%) | 93 501 (43.0%) | 81 640 | 390 593 | 725 (3.7%) | 2430 (2.6%) | 8.9 (8.2-9.5) | 6.2 (6.0-6.5) | 1.27 (1.16-1.38) | 1.05 (0.96-1.15) |

| Country of birth | ||||||||||

| Nordic | 40 805 (90.2%) | 187 422 (86.2%) | 316 037 | 1 465 132 | 3099 (7.6%) | 12347 (6.6%) | 9.8 (9.5-10.2) | 8.4 (8.3-8.6) | 1.10 (1.05-1.14) | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) |

| Other | 4449 (9.8%) | 29 889 (13.8%) | 33 771 | 213 353 | 191 (4.3%) | 908 (3.0%) | 5.7 (4.9-6.5) | 4.3 (4.0-4.5) | 0.90 (0.65-1.25) | 0.69 (0.47-1.00) |

| Level of education | ||||||||||

| ≤9 years | 8743 (19.3%) | 43 291 (19.9%) | 67 106 | 335 510 | 1332 (15.2%) | 6117 (14.1%) | 19.8 (18.8-20.9) | 18.2 (17.8-18.7) | 1.07 (0.99-1.16) | 0.93 (0.86-1.01) |

| 10-12 years | 21 067 (46.6%) | 95 852 (44.1%) | 164 178 | 755 212 | 1297 (6.2%) | 4930 (5.1%) | 7.9 (7.5-8.3) | 6.5 (6.3-6.7) | 1.13 (1.04-1.22) | 0.96 (0.88-1.04) |

| >12 years | 14 934 (33.0%) | 73 791 (34.0%) | 115 559 | 562 586 | 609 (4.1%) | 1958 (2.7%) | 5.3 (4.9-5.7) | 3.5 (3.3-3.6) | 1.17 (1.02-1.35) | 0.96 (0.83-1.12) |

| Missing | 510 (1.1%) | 4382 (2.0%) | 2 965 | 25 208 | 52 (10.2%) | 250 (5.7%) | 17.5 (12.8-22.3) | 9.9 (8.7-11.1) | 2.02 (0.76-5.37) | 2.22 (0.77-6.35) |

| IBS | ||||||||||

| Diagnosis before biopsy | 21 547 (47.6%) | 105 664 (48.6%) | 171 085 | 832 950 | 1244 (5.8%) | 5680 (5.4%) | 7.3 (6.9-7.7) | 6.8 (6.6-7.0) | 1.03 (0.96-1.10) | 0.91 (0.85-0.97) |

| Diagnosis after biopsy | 22 678 (50.1%) | 106 570 (49.0%) | 170 893 | 807 113 | 2000 (8.8%) | 7372 (6.9%) | 11.7 (11.2-12.2) | 9.1 (8.9-9.3) | 1.15 (1.09-1.21) | 0.99 (0.94-1.05) |

| Comorbidity | ||||||||||

| CVD | 6826 (15.1%) | 16 453 (7.6%) | 46 627 | 110 829 | 1304 (19.1%) | 3462 (21.0%) | 28.0 (26.4-29.5) | 31.2 (30.2-32.3) | 0.96 (0.87-1.06) | 0.92 (0.83-1.02) |

| MI | 387 (0.9%) | 1216 (0.6%) | 2 227 | 8 068 | 146 (37.7%) | 402 (33.1%) | 65.6 (54.9-76.2) | 49.8 (45.0-54.7) | 1.20 (0.55-2.59) | 1.47 (0.52-4.17) |

| CVD inpatient | 2769 (6.1%) | 7605 (3.5%) | 18 053 | 49 650 | 876 (31.6%) | 2411 (31.7%) | 48.5 (45.3-51.7) | 48.6 (46.6-50.5) | 0.94 (0.82-1.09) | 0.86 (0.74-1.01) |

| Cancer | 8121 (17.9%) | 19 090 (8.8%) | 56 166 | 131 002 | 1146 (14.1%) | 2286 (12.0%) | 20.4 (19.2-21.6) | 17.5 (16.7-18.2) | 1.00 (0.88-1.13) | 0.94 (0.83-1.07) |

Conditioned on matching set.

Conditioned on matching set and adjusted for education and baseline medical comorbidities (cancer, diabetes, CVD, and neurologic disease). # Age and year at start of follow-up.

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; CVD, cardiovascular disease; MI, myocardial infarction; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range

Cause-specific mortality

IBS patients were at a lower risk of cardiovascular disease (HR=0.92; 95%CI=0.87-0.98), cancer (HR=0.93; 95%CI=0.86-1.00), and psychiatric disease (multivariable HR 0.81; 95%CI=0.71-0.92)(Table 2).

Sensitivity analyses

In subgroup analysis of IBS patients with <1 year between biopsy and IBS diagnosis (n IBS = 26,432; n general population reference individuals = 130,073), the adjusted HR was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.88-1.00). We examined mortality in 116,802 unique patients with normal mucosal biopsies (i.e. no inflammation of any type) according to IBS status (see flow chart of the identification of study participants in Figure S3 and patient characteristics in Table S6). In this comparison, IBS was associated with a lower risk of death (HR=0.80; 95%CI=0.74-0.85, Table S7 and Figure S4).

When comparing 29,456 IBS patients and their siblings (n=53,228)(Figure S5 and Table S8), IBS was associated with a 9% increased risk of death (95%CI=1.00-1.18, Figure S6 and Table S9). Since a diagnosis of IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D) can potentially represent several other non-IBS diagnoses, we examined the role of IBS subtype (IBS-D and IBS non-D) in 45,184 IBS patients (Figure S7 and Table S10). We found no association with death in IBS-D but a lower risk of death in IBS non-D (Figure S8 and Tables S11-12). Excluding patients with additional IBS mimickers (giardiasis, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, porphyria, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, sucrose-isomaltase deficiency, pelvic floor dysfunction, or microscopic colitis) left an IBS population of 42,777 compared to 202,972 controls. In that population, the unadjusted HR for mortality was 1.09 (95%CI=1.05-1.14) with an adjusted HR of 0.96 (95%CI=0.92-1.00).

Finally, we examined the role of colorectal inflammation on mortality (Figure S9 and Table S13). Compared to matched reference individuals, IBS patients without inflammation had lower mortality (HR=0.88; 95%CI=0.83-0.94, Table S14 and Figure S10) while IBS patients with nonspecific colorectal inflammation had an increased mortality (HR 1.16; 95%CI=1.04-1.30, Table S15 and Figure S10).

Alternative IBS cohort

In a cohort of 41,427 IBS patients without colorectal biopsy (alternative definition), mortality was not increased (HR=1.02; 95%CI=0.99-1.06) compared to 204,890 non-biopsied reference individuals (Table S3 and Figure S1; Tables S4 and S5 and Figure S2).

DISCUSSION

In this nationwide population-based study of over 45,000 patients with IBS, we found no increased risk of all-cause or cause-specific death. Extensive sensitivity analyses consistently found HRs between 0.8 and 1.2, with a slightly increased mortality in those with colorectal inflammation and a lower mortality in those with normal mucosa. Compared to siblings without IBS, mortality in IBS-affected siblings was not significantly increased.

To date, there have been limited population-based data on mortality in IBS. The existing literature has been largely based on small numbers of IBS patients seeking care at single tertiary care centers and followed longitudinally without a comparator group.(10-13) To our knowledge the largest population-based survey study so far included less than 400 IBS patients and was limited to one US county.(14) However, that study similarly found no increased risk of death in IBS (HR=1.06; 95%CI=0.86-1.32).(14)

The lack of excess mortality risk in IBS in the current and other studies, seemingly runs counter to the established impacts on quality of life, work productivity, and healthcare resource utilization of the disease. Although IBS patients are greatly affected by their symptoms, tension arises when healthcare professionals rarely find a non-IBS diagnosis despite frequently exhaustive evaluations.(29) More than 50% of IBS patients worry that IBS will shorten their lifespan.(9) Importantly, many people with IBS will never seek care for their symptoms (between 30% and 90%),(30) and thus our formally-diagnosed population might represent a more severe subset of individuals with IBS. In this context, it is important that we analyzed both IBS patients with and without colorectal biopsies; in neither of the two groups did we detect any excess mortality.

IBS patients were slightly less likely to die from cancer (HR, 0.93) and had a 19% reduced risk of death from psychiatric disease. In surveys of IBS patients, fear of potential malignancy is common (>20%)(9) and associated with increased healthcare seeking.(8) Thus, our findings provide reassurance to patients and their providers that a diagnosis of IBS is unlikely to be a harbinger of undetected cancer. The reduced risk of death from psychiatric disease is surprising given the well-established connection between IBS, decreased quality of life, and psychiatric comorbidities.(1) Therefore, we urge caution when interpreting these results. It should be noted that this data does not suggest that the IBS patients in this cohort have lower incident rates of psychiatric disease, but rather lower rates of death directly attributed to psychiatric disease—an important distinction. Because we were reliant on registry information for death from psychiatric illness, there may be some misclassification bias in that psychiatric disease could lead to excess mortality by other means (i.e. failure to monitor one’s chronic medical disease). To that point, death from cardiovascular disease was the most common cause for excess mortality in Swedish patients with unipolar depression, a common comorbidity in IBS patients.(31)

In our sensitivity analyses, the only group with IBS and increased risk of mortality were those with histopathology suggestive of mucosal inflammation (16% increased mortality). Biomarkers of inflammation have consistently been linked to risk of all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality.(32) Some clinicians would argue that this subpopulation with known colonic inflammation would inherently represent an alternative diagnosis to IBS, which is not thought to be associated with colonic inflammation. However, the true incidence of minor mucosal abnormalities in IBS is unknown, with some evidence suggesting a variety of subtle morphologic changes among the colonic mucosa of patients with IBS,(33) and characterizing this subpopulation was beyond the scope of the current study. Although one might expect diarrhea to be a similar marker of organic disease, we found no increased mortality among those with IBS-D. Meanwhile, patients with IBS and a normal mucosa had an even lower mortality than their age- and sex-matched reference individuals who also had a normal mucosa.

Our study benefited from several notable strengths. It was 100 times larger than the largest prior population-based study of IBS and mortality.(14) The great statistical power allowed us to calculate precise risk estimates and to rule out more than marginal risk increases even in subgroups of patients. Of note the upper limit of our adjusted risk estimate for all-cause mortality was 1.00.

Our linkage to histopathology data, allowed us to examine the role of normal mucosa vs. inflammation. The well-validated Swedish registers with linkage through personal identity numbers(34) ensures virtually no loss to follow up. We were able to conduct extensive sensitivity analyses to confirm our main findings, specifically among IBS patients in the general population without histopathology, siblings, and varying degrees of histopathologic inflammation. We also accounted for relevant comorbidities using the Patient Register with a positive predictive value of 85-95%.(19)

We should acknowledge several limitations, including the risk of residual confounding (as in all observational studies). Most importantly, there is a potential for selection bias in a cohort of individuals undergoing biopsy in a disease that does not require biopsy for diagnosis. Therefore, our population may represent a subset of IBS patients in whom suspicion for organic disease is high enough to warrant endoscopic investigation. Nevertheless, a sensitivity analysis of over 40,000 individuals without colorectal biopsy showed no increase in mortality compared to non-biopsied reference individuals. Because the majority of those with IBS will never seek care for their symptoms,(30) and all IBS patients in our main analysis underwent lower endoscopy with biopsy, our analysis may represent a more severe subset of healthcare-seeking individuals. Despite this, we still did not find any increased mortality. To counter the influence of healthcare-seeking patterns in IBS patients, we were able to adjust for education through the LISA database,(20) which is an important predictor of care-seeking among those with gastrointestinal symptoms.(35) Furthermore, we relied on a single diagnostic code for identification of IBS patients. However, the ICD system is thought to have strong validity in IBS,(22) with an IBS diagnosis stable over time.(10, 36) Conditioning the IBS diagnosis on having an associated gastrointestinal biopsy also likely increases data validity and reduces the risk of misclassification error, which can occur when transcription error occurs in ICD coding. Limiting IBS diagnoses to a single code also minimizes the potential for immortal time bias in a study examining risk of death. Because Sweden is a single, relatively homogenous country there is a possibility that our findings may have limited generalizability to other parts of the world. However, Sweden has seen significant immigration in recent years such that almost 9% of our IBS cohort and almost 14% of our control cohort were born outside of a Nordic country. Finally, we did not have access to other laboratory values that may indicate an alternative diagnosis or severity of disease. We would argue, however, that histopathology data are likely a more reliable indicator of an alternative diagnosis, and the yield of additional investigations in patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of IBS is quite low.(29)

In conclusion, we show that IBS is not associated with increased mortality. Our findings should provide reassurance to IBS patients that their disease is unlikely to be life-shortening, while simultaneously allowing clinicians to spend greater time on patient education and effective treatment approaches for a disease with significant economic and societal burdens.

Supplementary Material

WHAT IS KNOWN

Mortality concern is one driver of care-seeking in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Data on mortality in IBS are limited to small studies and may suffer from selection bias.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

In this nationwide cohort study of >45,000 individuals with IBS, we found no association with mortality.

Despite having significant impacts on quality of life, IBS does not seem to affect the risk of death.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: KS is supported by an American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) career development award. HK is supported by NIDDK K23DK099681. ATC is supported by NIH DK098311.

Potential Competing Interests: KS has received research support from AstraZeneca, Takeda, and Gelesis, has served as a speaker for Shire, and has served as a consultant to Bayer Ag, Synergy, and Shire. JFL coordinates a study on behalf of the Swedish IBD quality register (SWIBREG). This study has received funding from Janssen. OO has been PI for projects (unrelated to the current paper) at KI partly financed by investigator-initiated grants from Janssen and Pfizer.

Abbreviations:

- CI

confidence interval

- HR

Hazard ratio

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

REFERENCES

- 1.Chey WD, Kurlander J, Eswaran S. Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. JAMA 2015;313:949–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:712–721 e714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, Spiller R. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyams JS, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, Shulman RJ, Staiano A, van Tilburg M. Functional Disorders: Children and Adolescents. Gastroenterology 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adriani A, Ribaldone DG, Astegiano M, Durazzo M, Saracco GM, Pellicano R. Irritable bowel syndrome: the clinical approach. Panminerva Med 2018;60:213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1480–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Irvine EJ, Muller-Lissner SA. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut 1999;45 Suppl 2:II43–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kettell J, Jones R, Lydeard S. Reasons for consultation in irritable bowel syndrome: symptoms and patient characteristics. Br J Gen Pract 1992;42:459–461. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halpert A, Dalton CB, Palsson O, Morris C, Hu Y, Bangdiwala S, Hankins J, et al. What patients know about irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and what they would like to know. National Survey on Patient Educational Needs in IBS and development and validation of the Patient Educational Needs Questionnaire (PEQ). Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1972–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owens DM, Nelson DK, Talley NJ. The irritable bowel syndrome: long-term prognosis and the physician-patient interaction. Ann Intern Med 1995;122:107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang YR, Wang P, Yin R, Ge JX, Wang GP, Lin L. Five-year follow-up of 263 cases of functional bowel disorder. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:1466–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes KM, Salter RH. Irritable bowel syndrome--a safe diagnosis? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;285:1533–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey RF, Mauad EC, Brown AM. Prognosis in the irritable bowel syndrome: a 5-year prospective study. Lancet 1987;1:963–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang JY, Locke GR 3rd, McNally MA, Halder SL, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Impact of functional gastrointestinal disorders on survival in the community. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:822–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford AC, Forman D, Bailey AG, Axon AT, Moayyedi P. Effect of dyspepsia on survival: a longitudinal 10-year follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:912–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spiegel BM. Do physicians follow evidence-based guidelines in the diagnostic work-up of IBS? Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;4:296–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talley NJ, Gabriel SE, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Evans RW. Medical costs in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1995;109:1736–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ludvigsson JF, Lashkariani M. Cohort profile: ESPRESSO (Epidemiology Strengthened by histoPathology Reports in Sweden). Clin Epidemiol 2019;11:101–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy AK, Ljung R, Michaelsson K, Neovius M, Stephansson O, et al. Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2016;31:125–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ludvigsson JF, Svedberg P, Olen O, Bruze G, Neovius M. The longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA) and its use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2019;34:423–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, Heurgren M, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navkiran J, Backman AS, Linder M, Altman M, Simren M, O O, Törnblom H. Validation of the Use of the ICD-10 Diagnostic Code for Irritable Bowel Syndrome in the Swedish National Patient Register. Gastroenterology 2014;146:S543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooke HL, Talback M, Hornblad J, Johansson LA, Ludvigsson JF, Druid H, Feychting M, et al. The Swedish cause of death register. Eur J Epidemiol 2017;32:765–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barlow L, Westergren K, Holmberg L, Talback M. The completeness of the Swedish Cancer Register: a sample survey for year 1998. Acta Oncol 2009;48:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swedish Society of Pathology. KVAST-dokument. In. Lund, Sweden: Swedish Society of Pathology; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westin M, Ahs A, Brand Persson K, Westerling R. A large proportion of Swedish citizens refrain from seeking medical care--lack of confidence in the medical services a plausible explanation? Health Policy 2004;68:333–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pappas G, Queen S, Hadden W, Fisher G. The increasing disparity in mortality between socioeconomic groups in the United States, 1960 and 1986. N Engl J Med 1993;329:103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ludvigsson JF, Haberg SE, Knudsen GP, Lafolie P, Zoega H, Sarkkola C, von Kraemer S, et al. Ethical aspects of registry-based research in the Nordic countries. Clin Epidemiol 2015;7:491–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ford AC, Lacy BE, Talley NJ. Irritable Bowel Syndrome. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2566–2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canavan C, West J, Card T. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Epidemiol 2014;6:71–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osby U, Brandt L, Correia N, Ekbom A, Sparen P. Excess mortality in bipolar and unipolar disorder in Sweden. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:844–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zuo H, Ueland PM, Ulvik A, Eussen SJ, Vollset SE, Nygard O, Midttun O, et al. Plasma Biomarkers of Inflammation, the Kynurenine Pathway, and Risks of All-Cause, Cancer, and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality: The Hordaland Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 2016;183:249–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirsch R, Riddell RH. Histopathological alterations in irritable bowel syndrome. Mod Pathol 2006;19:1638–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:659–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Almario CV, Ballal ML, Chey WD, Nordstrom C, Khanna D, Spiegel BMR. Burden of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in the United States: Results of a Nationally Representative Survey of Over 71,000 Americans. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:1701–1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Canavan C, Card T, West J. The incidence of other gastroenterological disease following diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome in the UK: a cohort study. PLoS One 2014;9:e106478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.