Discussion

Introduction

Recent studies estimate that 25 million people (0.5 – 1.3%) identify as transgender worldwide, approximately 1.4 million of whom reside in the United States (U.S.).1–3 These estimates are likely conservative because of the limited amount of studies that have attempted to measure the transgender population.

A recent survey by the French global market and research company Ipsos interviewed American panelists and showed that the majority (60%) of the 19,747 respondents aged 16–64 believe that their country is becoming more tolerant and want their government to do more to protect and support transgender people.4 Health governing bodies like the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and The World Health Organization (WHO) are following suit by reclassifying ‘gender identity disorder’ to ‘gender dysphoria’ and moving ‘gender incongruence’ from the panels’ mental health disorders chapter to the sexual health chapter respectively.

With this increase in visibility and acceptance, it is likely that more transgender people will present to a general surgical setting. Thus, there is a need for anesthesia providers to develop cultural competence and acquire the knowledge and skills necessary for safely managing transgender patients during the perioperative period.

Tprminnlngy

Critical to the understanding of what it means to be transgender is recognizing that although they are often used interchangeably, gender and sex are distinct. Sex refers to the sex assigned at birth, based on assessment of internal and external sex organs, chromosomes and hormonal activities within the body. Gender, on the other hand, is socially, culturally and personally defined. It includes how individuals see themselves, how others perceive them and expect them to behave, and the interactions that they have with others.

The conceptualization of gender as binary has dominated Western societies and continues to be enforced by the media, religion, mainstream education, and political, cultural, and social systems. However, the binary paradigm is not embraced by many cultures worldwide. Some examples include the Muxes in Juchitan de Zagroza 5, the two spirit native North American Navajo culture, the Fa’afines in Samoa 6 and the Hijra’s in South Asia who have recently been legally recognized as a third gender in several South Asian countries.7

Some people have a gender that is neither male nor female and may identify as both at the same time, as different genders at different times, as no gender at all or dispute the very idea of only two genders. Definitions of these categories vary and continue to evolve over time with an array of terms describing one’s gender or genders (Table 1).8

Table 1:

Definitions of gender categories

| Terminology | Definition |

|---|---|

| Cis gender | People whose gender identity matches their sex assigned at birth |

| Transgender male (female to male) | A person who was assigned female at birth, but identifies as a man or on the masculine spectrum |

| Transgender female (male to female) | A person who was assigned male at birth, but identifies as a woman or on the feminine spectrum |

| Gender nonconforming, genderqueer | A person whose gender identity differs from that which was assigned at birth, but may be more complex, fluid, multifaceted, or less clearly defined than a transgender person |

| Nonbinary | Transgender or gender nonconforming person who identifies as neither male nor female. |

| Transitioning | A person’s process of developing and assuming a gender expression to match their gender identity. |

| Transsexual | A clinical term previously used to describe those transgender people who sought medical intervention |

From Kuper LE, Nussbaum R, Mustanski B. Exploring the diversity of gender and sexual orientation identities in an online sample of transgender individuals. J Sex Res 2012;49(2–3):244–254; with permission.

It is also important to note that there is a difference between gender non-conformity and gender dysphoria. Gender non-conformity refers to the extent to which a person’s gender identity, role or expression differs from the cultural norms prescribed for people of a particular sex. Gender dysphoria based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5) criteria refers to the clinically significant impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning caused by a discrepancy between a person’s gender identity and that person’s sex assigned at birth.9,10

Barriers to healthcare

The transgender community is arguably the most marginalized and underserved population in medicine. Although being transgender does not determine a person’s health, the appalling effects of social and economic marginalization are associated with various adverse health outcomes. These include increased rates of HIV infection, smoking, some cancers, drug and alcohol use and suicide attempts compared to the general population.11–14

Access to healthcare as defined by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) is ‘timely use of personal health services to achieve the best possible outcome’. To understand a transgender patient’s pre-surgical needs, we first need to address the unique barriers to accessing healthcare they face. These barriers can be divided into three groups: personal, structural and financial barriers.

Personal barriers are largely driven by transgender stigma, the inferior status and relative powerlessness that society collectively assigns to this group of people. These widespread stigmas can prevent a transgender patient from attempting to access quality care.15

Structural barriers are faced at an institutional level including healthcare systems and insurance policies. Pro-transgender laws (such as the nondiscrimination provision of the Affordable Care Act) make healthcare discrimination against transgender and gender non-conforming people illegal under existing federal law.

Despite these nondiscrimination provisions, transgender patients are still less likely to have health insurance coverage compared to their cisgender counterparts.16 Not only are they more likely to be uninsured than the general population, they are also less insured than lesbian, gay and bisexual persons.17 In a 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, 55% of patients who sought surgery and 25% of those on hormones reported difficulty obtaining insurance coverage.18

Even with these laws in place, having access to healthcare does not equate to having adequate high-quality care. Transgender patients report that lack of providers with expertise in transgender medicine represents the single largest component inhibiting access. 19 They often encounter ignorance about basic aspects of transgender health. In one widely disseminated study, 50% of respondents reported having to teach providers some aspect of their health needs. 13 Poor patient-provider communication is strongly associated with adverse health behaviors such as decreased levels of adherence to physician advice and decreased rates of satisfaction. 20 Transgender populations experience health inequities in part due to the exclusion of transgender-specific health needs from medical school and residency curricula. Of all LGBTQ topics, transgender health is the least well understood. Seventy-four percent of medical students report receiving less than two hours of curricular time devoted to transgender clinical competency.21

The rising cost of healthcare is another hurdle transgender patients must overcome to access quality care. A survey reported that transgender people are experiencing an unemployment rate of 14%, double the national average at the time and 15% reported a household income under $10,000 a year.13 The paucity of insurance coverage for hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgery, even among those who are able to secure health insurance, contributes to a high financial burden.22

Gender-affirming therapies

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) has established internationally accepted Standards of Care for the treatment of gender dysphoria. There are a wide range of therapeutic options which can be divided into four broad categories9:

1. Behavioral modification

Transgender people may use techniques such as genital tucking (pushing the testes into the inguinal canal and securing the penis back between the legs with an undergarment), packing (placing of a penile prosthesis in one’s underwear), or chest binding (methods of flattening breast tissue) to reduce the symptoms of gender dysphoria.23

2. Psychotherapy

The aim of psychotherapy is to treat the dysphoria and associated symptoms, not the person’s gender identity. Its goal is alleviating internalized transphobia, symptoms of depression, anxiety, fear, guilt, low self-esteem, shame and self-hatred.9

3. Medical management

Medical management consists of cross-sex hormone therapy (CSHT) as the primary intervention. CSHT can be divided into feminizing and masculinizing therapy.

The goal of feminizing hormone therapy is the development of female secondary sex characteristics and suppression of male secondary sex characteristics. Therapy consists mainly of estrogen, progestogens and anti-androgens. Estrogen (17-beta estradiol) is most commonly delivered via a transdermal patch, oral or sublingual tablet or injection of a conjugated ester. Anti-androgens include spironolactone and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors such as finasteride and dutasteride.24 Most physical changes occur over the course of two years depending on the dose, route of administration and medications used.

The goal of masculinizing hormone therapy is the development of male secondary sex characteristics, and suppression of female secondary sex characteristics. Therapy consists of several forms of parenteral or oral testosterone.25

Healthcare providers need to be cognizant of the risks when subjecting patients to CSHT. According to the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, transgender youth who receive inadequate treatment are at an increased risk for engaging in self-harm or obtaining injected hormones through illegal means.26

4. Surgical management

The number of patients presenting for gender-related medical and surgical care is increasing dramatically. This is thought to be, in large part, a result of the Affordable Care Act, which states that it is unlawful for an insurance carrier to “have or implement a categorical coverage exclusion or limitation for all health services related to gender transition”.

Female to Male (FTM) surgeries include:

Bilateral mastectomy (top surgery)

Removal of female genitalia and creating male genitalia through phalloplasty, scrotoplasty

Implantation of testicular prostheses (bottom surgery)

Non-genital non-breast surgeries (voice surgery and liposuction)9,27

It is important to note that many transgender men choose to retain their uterus and ovaries, which impacts future fertility options.

Male to Female (MTF) surgeries include:

Augmentation mammoplasty (top surgery)

Removal of male genitalia and constructing female genitalia through vaginoplasty, clitoroplasty and vulvoplasty (bottom surgery)

Non-genital non-breast surgeries (thyroid cartilage reduction, voice surgery)

Preoperative

A healthcare facility might be a traumatizing place for a transgender patient with a large portion of patients reporting harassment in a medical setting or violence at a doctor’s office.13 A culturally appropriate environment in which the patient feels safe and welcomed needs to be provided. It is imperative that all staff including nursing, front desk and allied health personal be aware of transgender terminology and health issues. Waiting areas should include transgender-themed posters, legal rights and pamphlets to emphasize the importance of this marginalized community. Bathroom policies should be clearly defined as either being gender-neutral or allowing the patient to choose bathrooms based on their own preference.

Transgender patients may have a chosen name and gender identity that differs from their current legally designated name and sex. It is important to record each patient’s preferred name and pronoun (Table 2) so that they can be used throughout the healthcare facility.28 Incorrect use or disregard of patients’ preferences reinforces stigmas and may lead the patient to not return for further care.

Table 2:

Gender pronouns

| Terminology | Pronoun |

|---|---|

| Cis-male | He/him/himself |

| Cis-female | She/her/herself |

| Transgender male | He/him/himself |

| Transgender female | She/her/herself |

| Gender nonconforming | They/them/themself |

| Gender neutral | Zhe/zhim/zher/zhers/zhimself |

Adapted from Deutsch MB, Buchholz D. Electronic health records and transgender patients--practical recommendations for the collection of gender identity data. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30(6):846; with permission.

The best practice for collecting gender identity data (sex assigned at birth, gender identity, preferred name and preferred pronoun) is through a two-step questionnaire using gender identity followed by sex assigned at birth (Box 1).29 This process has been made easier through The Joint Commission who now requires that all electronic health record systems certified under the Meaningful Use incentive program have the capacity to collect sexual orientation and gender identity information.30

Box 1. Collection of Gender Identity on a Patient Intake Form.

| 1. What is your current gender identity? (check and/or circle all that apply) |

| □ Female |

| □ Male |

| □ Transgender male/transman/FTM |

| □ Transgender female/transwoman/MTF |

| □ Genderqueer |

| □ Additional category (please specify):__________ |

| □ Decline to answer |

| 2. What sex were you assigned at birth? (check one) |

| □ Male |

| □ Female |

| □ Decline to answer |

Adapted from Tate CC, Ledbetter JN, Youssef CP. A two-question method for assessing gender categories in the social and medical sciences. J Sex Res 2013;50(8):767–776; with permission.

This, however, does not negate the fact that transgender patients may stili present to the preanesthetic clinic with legal documents incongruent with their preferred name and/or gender identity. To ensure proper documentation for legal and insurance purposes the patients’ legal photograph identification and insurance card should be noted.

Interview

Careful consideration should be taken when interviewing a transgender patient. Specific details regarding one’s transgender status and transition history, including an inventory of organs and information on hormone use should be recorded.28 Clinicians should inquire about silicone or other filler use as many are injected by unlicensed medical providers. Improper use can lead to devastating effects such as Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), sepsis, embolization, hypersensitivity pneumonitis or hypercalcemia.31,32

A detailed smoking history should be recorded, especially in transgender females, as hormone therapy (estrogen) and smoking are both independent factors for venous thromboembolism (VTE).33,34

Physical exam

As part of the preoperative assessment a focused physical examination must be performed. The exam should be relevant to the anatomy that is present, regardless of gender presentation, and without assumptions as to the anatomy or identity of the patient. During the examination the provider should be aware of the patient’s preferred pronoun and use a gender affirming approach. Gender affirmation refers to a process whereby a person receives social recognition and support for their gender identity and expression through social interactions.35

A chaperone should be present during physical examinations, with the appropriate gender of the chaperone decided by the patient. Transgender and gender-nonconforming patients should have the option to be examined by medical students or residents to help further the education and cultural sensitivity of future providers, but have the right to refuse if it makes them uncomfortable.

While examining the patient, be aware that secondary sex characteristics may present along a spectrum of development in patients undergoing hormone therapy.

Routine tests

Appropriate laboratory testing is an important process in the pre-procedural preparation of the patient. These investigations can be helpful to stratify risk, direct anesthetic choices and guide postoperative management. The use of these tests is generally guided by the patient’s clinical history, comorbidities and findings on physical examination. When interpreting preoperative laboratory results of a transgender patient it is important to understand how hormone therapy can affect these parameters.

The effects of testosterone and estrogen on a patient’s blood chemistry can vary depending on the drug and duration of therapy. CSHT decreases hemoglobin, hematocrit and creatinine levels in transgender women and increases these levels in transgender men. Additionally, a decrease in calcium, albumin and alkaline phosphatase levels can be expected in transgender woman with increased triglycerides and decreased HDL levels in transgender men (Table 3). 36–39

Table 3.

Changes in Laboratory Values for Transgender People on Hormone Therapy

| Transgender woman on HT | Transgender men on HT | |

|---|---|---|

| Increased | Red blood cell count Hemoglobin concentration Hematocrit Creatinine Triglycerides |

Red blood cell count Hemoglobin concentration Hematocrit Creatinine Alkaline phosphate Aspartate aminotransferase Alanine aminotransferase Triglycerides |

| Decreased | Calcium Albumin Alkaline phosphate |

HDL |

Modified from SoRelle JA, Jiao R, Gao E, et al. Impact of Hormone Therapy on Laboratory Values in Transgender Patients. Clin Chem 2019;65(1):174; with permission.

Preliminary research suggests that transgender patients on CSHT for longer than six months should have their laboratory values compared to that of their cis-counterparts rather than to those of their sex assigned at birth.40 Clearly new reference intervals need to be established for transgender patients. In the interim the Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People has created tables as tools for healthcare providers to interpret chemistry levels (Tables 4 and 5).41

Table 4.

Interpreting selected lab tests in transgender women using feminizing hormone therapy

| Lab measure | Lower limit of normal | Upper limit of normal |

|---|---|---|

| Creatinine | Not defined | Male value |

| Hemoglobin/Hematocrit | Female value | Male value |

Adapted from UCSF Transgender Care, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California San Francisco. Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People; 2nd edition. Overview of feminizing hormone therapy. Deutsch MB, ed. June 2016. Available at transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines; with permission.

Table 5.

Interpreting selected lab tests in transgender men using masculinizing hormone therapy

| Lab measure | Lower limit of normal | Upper limit of normal |

|---|---|---|

| Creatinine | Not defined | Male value |

| Hemoglobin/Hematocrit | Male value * | Male value |

If menstruating regularly, consider using female lower limit of normal.

Adapted from UCSF Transgender Care, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California San Francisco. Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People; 2nd edition. Overview of masculinizing hormone therapy. Deutsch MB, ed. June 2016. Available at transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines; with permission.

Healthcare providers also need to be aware that transgender females are often prescribed spironolactone to suppress testosterone production. It is particularly important to monitor serum potassium and creatinine levels in these patients.37

Pregnancy testing

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Practice Advisory for Preanesthesia Evaluation recommends that pregnancy testing be offered to (biological) female patients of childbearing age for whom the result would alter the patient’s medical management. This rule extends to transgender men with intact female reproductive organs.42

In a recent study, 54% of transgender males reported that they desired to have children.43 Despite uncertainty about predictable fertility effects, transgender men with intact female reproductive organs have successfully conceived and carried a pregnancy after using testosterone. Transgender men may also have unintended pregnancies while taking or still amenorrheic from testosterone, which was previously thought to preclude pregnancy.44

Preoperative risk assessment

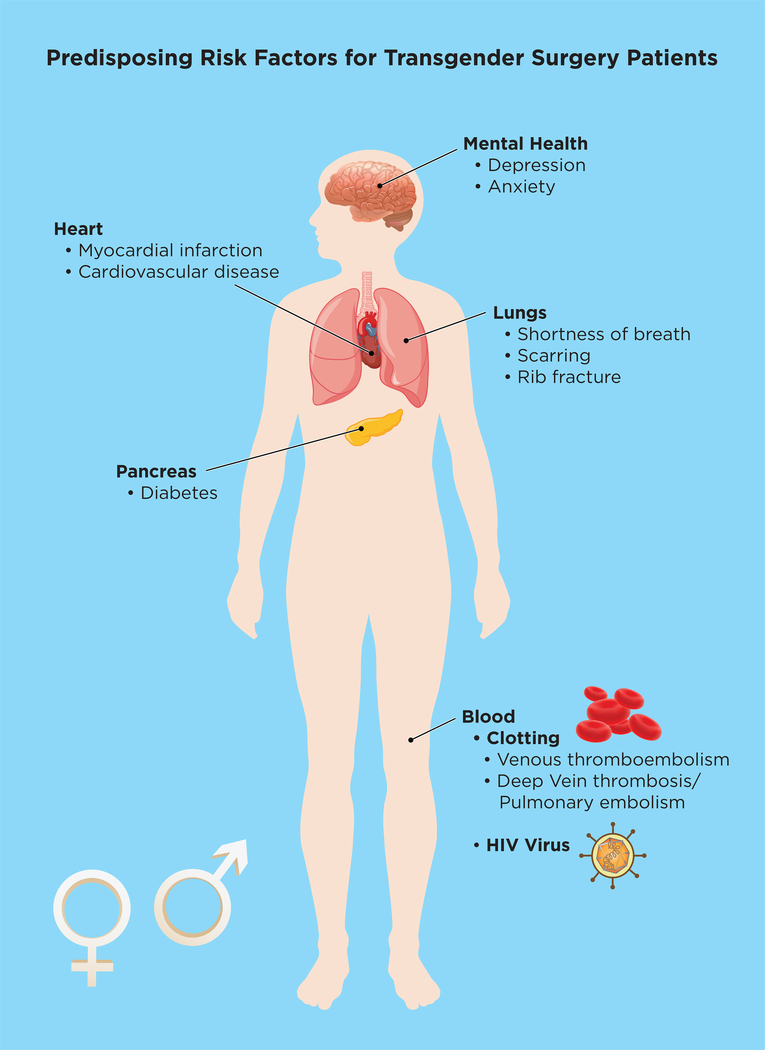

All patients scheduled to undergo surgery should be assessed for the risk of a perioperative cardiovascular events. Risk models have been designed to estimate patients’ perioperative risk based on information obtained from the history, physical examination, electrocardiogram and type of surgery. Special attention should be paid to transgender patients as they face a unique set of risks of which anesthesiologists may be unaware (Figure 1). Currently there is no guidance on whether to use risk calculators based on natal sex or affirmed gender.

Figure 1:

Consideration for Transgender Patients Perioperatively.

Cardiovascular risk factors

Sex is an independent predictor of cardiovascular health outcomes. Few studies have investigated cardiovascular disease risk and burden among transgender people on hormone therapy thereby limiting appropriate primary and specialty care.

For transgender adults on hormone therapy, an association with increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors such as blood pressure elevation, insulin resistance, and lipid derangements has been appreciated. Up to recently, these changes have not been associated with an increase in morbidity or mortality in transgender men.45,46

Transgender women receiving hormone therapy have a higher prevalence of venous thrombosis, myocardial infarction, CVD and type 2 diabetes compared to the general population.36,46,47 Several factors may contribute to the increase in CVD such as higher rates of tobacco use, obesity, diabetes, lipid disorders, reduced physical activity and the use of ethinyl estradiol.

In a recent study published by the American Heart Association (AHA), transgender men on CSHT had a >2-fold increase in the rate of myocardial infarction compared with cisgender men and 4-fold increase compared to cisgender women. Transgender women on CHST had >2-fold increase in the rate of myocardial infarction compared with cisgender women, but showed no significant increase compared to cisgender men even after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors.

Diabetes Mellitus

The effect of gender-affirming hormone therapy on diabetes risk or disease course is unclear. Several studies have indicated that there is a higher prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in both transgender men and women compared to their respective controls.36,38 Transgender people were also shown to have several modifiable factors that contributes to diabetes complications, specifìcally high triglycerides and HDL cholesterol.48 The current recommendations for diabetes screening in transgender patients (regardless of hormone status) do not differ from current national guidelines.

Venous thromboembolism

Transgender women receiving cross-sex hormones are at increased risk of VTE as compared to both cisgender women and men.34,46 High rates of VTE have been attributed to historic use of ethinyl estradiol, which is no longer recommended. A retrospective cohort of Dutch transgender women found no increased risk in VTE once ethinyl estradiol was replaced by bioidentical estradiol49

Transdermal estrogen appears to be safer than estrogen taken orally in relation to the risk of thrombosis and VTE.34 Protocols on the use of estrogen in transgender women should consider additional VTE risk factors such as smoking, hypercoagulable disorders, cancer diagnosis, length of surgery and duration of immobilization.50

The following steps can be taken to reduce the risk of VTE in transgender women with cardiovascular risk factors. Stopping CSHT two weeks prior to major surgery and resuming after three weeks of full mobilization has been proposed. Conflicting evidence regarding its benefit has kept it from becoming the standard recommendation.49,51 If the decision is made to continue with hormone therapy, consider using a different estrogen formulation and route of administration, preferably transdermal. Additionally aspirin 81mg/day can also be considered as a preventive measure specifically in smokers.41 Lastly, intra-operative VTE prophylaxis in the form of subcutaneous heparin and sequential compression devices should be used.52

Pulmonary

Chest binding, or compressing the chest tissue, is a common practice among transgender males. There is a lack of research that directly assesses the long-term health impacts of chest binding, but negative physical symptoms have been reported. Symptoms range from chest pain and shortness of breath to scarring and rib fractures.53 Providers must clearly explain to patients that these devices should not be present during the intraoperative and immediate postoperative period to mitigate the associated cardiopulmonary derangements of binders.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

As previously discussed, HIV has a high prevalence in the transgender community with an estimated 14% of transgender women infected with the virus.54 Perioperative risks linked to HIV infection include hepatic and renal dysfunction, coronary artery disease, pulmonary arterial hypertension and cardiac abnormalities, respiratory complications, drug allergies and hematological abnormalities.55

Patient’s perspective

The anesthesiologist’s preoperative consultation is central to the enhancement of trust and the creation of a safe environment in which the patient feels comfortable. All staff should address the patient with the name, pronouns, and gender identity that the patient prefers.56 Discussion between the anesthesiologist and the patient should include room assignment, where they will wait during the preoperative period, how they will get to the operating room and where they will go postoperatively.

Intraoperative

Drug interactions

No drug interactions between estrogen, the various androgen blockers and testosterone with anesthesia medications have been reported.

Due to the high prevalence of HIV in the transgender community there is a chance that patients may be on antiretroviral therapy (ART). It is important to note that some ART medications, specifically the protease inhibitors and non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors, are primarily metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes. The clinician needs to be aware that these drugs may have significant interactions with sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics and antibiotics.57

Anatomical considerations

Transgender patients, especially transgender females may alter aspects of their voice through surgical procedures like laryngoplasty and/or chondroplasty to alleviate the symptoms of gender dysphoria. Risks of these procedures include vocal cord damage, reduction of tracheal lumen or stenosis, dysphagia or tracheal perforation all of which can affect intraoperative airway management.23,58

Gender-confìrming surgery involving the urethra (vaginoplasty, phalloplasty, or metoidioplasty with urethral lengthening) may require using a smaller urinary catheter. If there is uncertainty, consult a urologist or practitioner experienced with transgender anatomy.23

Postoperative

The postoperative period is a challenging and vulnerable time for the transgender patient as they deal with postoperative pain, withdrawal, anxiety and depression.

It is important that there are detailed reports and hand-offs between care providers at different stages in the postoperative period. This is a vulnerable period for the patient as the effects of residual anesthesia can impact and the patient’s ability to accurately confirm medical history and preferred names and pronouns.

Pain

Pain management is of great importance during the post-operative period, even more so for the transgender patient. Contributing elements to postoperative and chronic pain include psychological factors like depression, fear and anxiety as well as medical factors such as hormone-induced osteoporosis, previous surgeries and an impaired immune system. A multimodal approach, including non-pharmacologic psychological pain therapies should be used whilst being cognizant of the high drug addiction rate among transgender patients. Community and social work support is an important component of the long-term management of these patients and regular follow-ups might be required.59

Psychosocial

The transgender community is at higher risk of psychiatric morbidity due to depression and anxiety disorder. Budge et al estimated the rates of depression in transgender men and women at 48.3% and 51.4%, respectively.60 This is relevant to surgery as patients with a history of these disorders are at higher risk for poorer outcomes, including increased opioid use and mortality.61,62 Furthermore, surgery and prolonged inpatient hospital stays may worsen these conditions.63 It is important to have a holistic approach when managing a transgender patient during the postoperative period. Incorporate all team members in the decision-making process and consult mental healthcare, social work and spiritual care to address the patient’s specific needs.

Room assignment

Post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) room assignment should ideally be discussed during the preoperative assessment. Where room assignments are gender-based, transgender patients should be assigned to rooms based on their self-identified gender.64 Consider a private room if there is availability, as the increased privacy may provide additional comfort to the patient. Clear communication with PACU staff is needed to avoid unnecessary confrontations and potentially embarrassing situations for the patient.

Conclusion

Transgender and gender non-conforming people face rampant discrimination in every area of life. Access to quality healthcare should not be denied to this large, underrepresented population. Anesthesiologists need to acquire an in-depth understanding of the transgender patient’s medical and psychosocial needs. A thoughtful approach throughout the entirety of the perioperative period is key to the successful management of the transgender patient.

Disclosure statement

The authors work was supported and funded in part by NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 LET serves a paid consultancy and advisory role for Merck & Co. Pharmaceutical Company.

Synopsis.

With a shift in the cultural, political and social climate surrounding gender and gender identity, an increase in the acceptance and visibility of transgender individuals can be expected. Anesthesiologists are thus more likely to encounter transgender and gender nonconforming patients in the perioperative setting.

The purpose of this review is to provide anesthesiologists with a culturally relevant and evidence-based approach to transgender patients during the pre-, intra- and postoperative periods.

Key Points.

Barriers to healthcare: The transgender community is arguably the most marginalized and underserved population in medicine. Personal, structural and financial barriers restrict access to health services for this patient population.

Preoperative assessment: Healthcare facilities should be safe and welcoming places with progressive and inclusive hospital policies. Clinicians should use a gender affirming approach when interviewing or examining a transgender patient and must be aware of the effect cross hormone therapy can have on laboratory results.

Risk assessment: All patients scheduled to undergo surgery should be assessed for the risk of a perioperative cardiovascular event. Transgender patients are at an increased risk of myocardial infarction, diabetes, venous thromboembolism and pulmonary complications.

Intraoperative management: Clinicians should be aware of altered anatomy that could affect intraoperative airway management, possible drug interactions and the increased risk of venous thromboembolism.

Postoperative management: The postoperative period is a vulnerable time for the transgender patient. A multidisciplinary approach must be taken when managing pain, respecting privacy and assuring mental wellbeing.

Acknowledgments

LET is a grant recipient through Merck Investigators Studies Program (MISP) to fund clinical trial at MSKCC (NCT03808077)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.FARHJLGGJB TN. Howmanyadults identifyas transgenderin the united States? : The Williams Institute;2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J, et al. Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: a review. TheLancet. 2016;388(10042):412–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zucker KJ. Epidemiology of gender dysphoria and transgender identity. Sexualhealth. 2017;14(5):404–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark JJC. Global Attitudes Toward Transgender People. IPSOS;2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez FR, Semenyna SW, Court L, Vasey PL. Familial patterning and prevalence of male androphilia among Istmo Zapotec men and muxes. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0192683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Semenyna SW, Vasey PL. Striving for Prestige in Samoa: A Comparison of Men, Women, and Fa’afafine. Journal of homosexuality. 2018:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hossain A The paradox of recognition: hijra, third gender and sexual rights in Bangladesh. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2017; 19(12):1418–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuper LE, Nussbaum R, Mustanski B. Exploring the diversity of gender and sexual orientation identities in an online sample of transgender individuals. Journal of sex research. 2012;49(2–3):244–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Health TWPAfT. The World Professional Association for Transgender HealthStandards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People. 2011.

- 10.Davy Z, Toze M. What Is Gender Dysphoria? A Critical Systematic Narrative Review. Transgend Health. 2018;3(1):159–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean L, Meyer IH, Robinson K, et al. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health: Findings and Concerns. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. 2000;4(3):102–151. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ, McKleroy VS, Neumann MS, Crepaz N. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS and behavior. 2008; 12(1):1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant JM, Mottet L, Tanis JE, et al. Injustice at every turn : a report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. 2011.

- 14.Barboza GE, Dominguez S, Chance E. Physical victimization, gender identity and suicide risk among transgender men and women. Prev Med Rep. 2016;4:385–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Safer JD, Pearce EN. A simple curriculum content change increased medical student comfort with transgender medicine. Endocrine practice : official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. 2013;19(4):633–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts TK, Fantz CR. Barriers to quality health care for the transgender population. Clinical biochemistry. 2014;47(10–11):983–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daniel H, Butkus R, Health ft, Physicians PPCotACo. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Disparities: Executive Summary of a Policy Position Paper From the American College of PhysiciansLGBT Health Disparities. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2015;163(2):135–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James SHJ, Rankin S, et al. 2015 US Transgender survey report on health and healthcare. National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanchez NF, Sanchez JP, Danoff A. Health care utilization, barriers to care, and hormone usage among male-to-female transgender persons in New York City. American journal of public health. 2009;99(4):713–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown J, Noble Lorraine M, Papageorgiou A, Kidd J. 2015.

- 21.Dubin SN, Nolan IT, Streed CG Jr., Greene RE, Radix AE, Morrison SD. Transgender health care: improving medical students’ and residents’ training and awareness. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:377–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lane M, Ives GC, Sluiter EC, et al. Trends in Gender-affirming Surgery in Insured Patients in the United States. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6(4):e1738–e1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tollinche LE, Walters CB, Radix A, et al. The Perioperative Care of the Transgender Patient. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(2):359–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis P, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, et al. Endocrine Treatment of Transsexual Persons:An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2009;94(9):3132–3154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gardner IH, Safer JD. Progress on the road to better medical care for transgender patients. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 2013;20(6):553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Committee Opinion no. 512: health care for transgender individuals. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2011;118(6):1454–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berli JU, Knudson G, Fraser L, et al. What Surgeons Need to Know About Gender Confirmation Surgery When Providing Care for Transgender Individuals: A ReviewWhat Surgeons Need to Know About Gender Confirmation SurgeryWhat Surgeons Need to Know About Gender Confirmation Surgery. JAMA Surgery. 2017;152(4):394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deutsch MB, Buchholz D. Electronic health records and transgender patients--practical recommendations for the collection of gender identity data. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(6):843–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tate CC, Ledbetter JN, Youssef CP. A two-question method for assessing gender categories in the social and medical sciences. Journal of sex research. 2013;50(8):767–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cahill SR, Baker K, Deutsch MB, Keatley J, Makadon HJ. Inclusion of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Stage 3 Meaningful Use Guidelines: A Huge Step Forward for LGBT Health. LGBT health. 2016;3(2):100–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hage JJ, Kanhai RC, Oen AL, van Diest PJ, Karim RB. The devastating outcome of massive subcutaneous injection of highly viscous fluids in male-to-female transsexuals. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2001;107(3):734–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Visnyei K, Samuel M, Heacock L, Cortes JA. Hypercalcemia in a male-to-female transgender patient after body contouring injections: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2014;8:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng Y-J, Liu Z-H, Yao F-J, et al. Current and former smoking and risk for venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS Med 2013;10(9):e1001515–e1001515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan W, Drummond A, Kelly M. Deep vein thrombosis in a transgender woman. CMAJ. 2017;189(13):E502–E504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sevelius JM. Gender Affirmation: A Framework for Conceptualizing Risk Behavior among Transgender Women of Color. Sex Roles. 2013;68(11–12):675–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wierckx K, Elaut E, Declercq E, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease and cancer during cross-sex hormone therapy in a large cohort of trans persons: a case-control study. European journal of endocrinology. 2013;169(4):471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts TK, Kraft CS, French D, et al. Interpreting laboratory results in transgender patients on hormone therapy. The American journal of medicine. 2014;127(2):159–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Defreyne J, Vantomme B, Van Caenegem E, et al. Prospective evaluation of hematocrit in gender-affirming hormone treatment: results from European Network for the Investigation of Gender Incongruence. Andrology. 2018;6(3):446–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.SoRelle JA, Jiao R, Gao E, et al. Impact of Hormone Therapy on Laboratory Values in Transgender Patients. Clinical Chemistry. 2018:clinchem.2018.292730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldstein Z, Corneil TA, Greene DN. When Gender Identity Doesn't Equal Sex Recorded at Birth: The Role of the Laboratory in Providing Effective Healthcare to the Transgender Community. Clinical Chemistry. 2017;63(8):1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deutsch MB. Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People. 2016; 2:www.transhealth.ucsf.edu/guidelines, 2019.

- 42.Practice Advisory for Preanesthesia Evaluation: An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. 2012;116(3):522–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wierckx K, Van Caenegem E, Pennings G, et al. Reproductive wish in transsexual men. Human Reproduction. 2011;27(2):483–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Light AD, Obedin-Maliver J, Sevelius JM, Kerns JL. Transgender men who experienced pregnancy after female-to-male gender transitioning. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2014;124(6):1120–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith FD. Perioperative Care of the Transgender Patient. AORN journal. 2016; 103(2):151–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alzahrani T, Nguyen T, Ryan A, et al. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors and Myocardial Infarction in the Transgender Population. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2019;12(4):e005597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Irwig MS. Cardiovascular health in transgender people. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders. 2018;19(3):243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elbers JM, Giltay EJ, Teerlink T, et al. Effects of sex steroids on components of the insulin resistance syndrome in transsexual subjects. Clinical endocrinology. 2003;58(5):562–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asscheman H, Giltay EJ, Megens JA, de Ronde WP, van Trotsenburg MA, Gooren LJ. A long-term follow-up study of mortality in transsexuals receiving treatment with cross-sex hormones. European journal of endocrinology. 2011;164(4):635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tangpricha V, den Heijer M. Oestrogen and anti-androgen therapy for transgender women. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(4):291–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boskey ER, Taghinia AH, Ganor O. Association of Surgical Risk With Exogenous Hormone Use in Transgender Patients: A Systematic ReviewAssociation of Surgical Risk With Exogenous Hormone Use in Transgender Patients—A Systematic ReviewAssociation of Surgical Risk With Exogenous Hormone Use in Transgender Patients—A Systematic Review. JAMA Surgery. 2019;154(2):159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kozek-Langenecker S, Fenger-Eriksen C, Thienpont E, Barauskas G. European guidelines on perioperative venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: Surgery in the elderly. European journal of anaesthesiology. 2018;35(2):116–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jarrett BA, Corbet AL, Gardner IH, Weinand JD, Peitzmeier SM. Chest Binding and Care Seeking Among Transmasculine Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Transgend Health. 2018;3(1):170–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Becasen JS, Denard CL, Mullins MM, Higa DH, Sipe TA. Estimating the Prevalence of HIV and Sexual Behaviors Among the US Transgender Population: A Systematic Review and Meta- Analysis, 2006–2017. American journal of public health. 2019;109(1):e1–e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Committee MCC. Perioperative Management. 2012; https://www.hivguidelines.org/hiv-care/perioperative-management/#tab1 Accessed 20 May, 2019.

- 56.Rosa DF, Carvalho MVdF, Pereira NR, Rocha NT, Neves VR, Rosa AdS. Nursing Care for the transgender population: genders from the perspective of professional practice. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem. 2019;72:299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oluwabukola A, Adesina O. Anaesthetic considerations for the hiv positive parturient. Ann Ib Postgrad Med. 2009;7(1):31–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nolan IT, Morrison SD, Arowojolu O, et al. The Role of Voice Therapy and Phonosurgery in Transgender Vocal Feminization. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pisklakov S, Carullo V. Care of the Transgender Patient: Postoperative Pain Management. Topics in Pain Management. 2016;31(11):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Budge SLAJ, Howard KAS. Anxiety and Depression in Transgender Individuals: The Roles ofTransition Status, Loss, Social Support, and Coping. J Consult Clin Psychol 2013;81(3):545–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Armaghani SJ, Lee DS, Bible JE, et al. Preoperative opioid use and its association with perioperative opioid demand and postoperative opioid independence in patients undergoing spine surgery. Spine (PhilaPa 1976). 2014;39(25):E1524–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Connerney I, Sloan RP, Shapiro PA, Bagiella E, Seckman C. Depression is associated with increased mortality 10 years after coronary artery bypass surgery. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(9):874–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nickinson RSJ, Board TN, Kay PR. Post-operative anxiety and depression levels in orthopaedic surgery: a study of 56 patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2009;15(2):307–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.CREATING EQUAL ACCESSTO QUALITY HEALTH CARE FOR TRANSGENDER PATIENTS, TRANSGENDER-AFFIRMING HOSPITAL POLICIES. 2016.