Abstract

Background

Over the decades, a variety of psychological interventions for borderline personality disorder (BPD) have been developed. This review updates and replaces an earlier review (Stoffers‐Winterling 2012).

Objectives

To assess the beneficial and harmful effects of psychological therapies for people with BPD.

Search methods

In March 2019, we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, 14 other databases and four trials registers. We contacted researchers working in the field to ask for additional data from published and unpublished trials, and handsearched relevant journals. We did not restrict the search by year of publication, language or type of publication.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing different psychotherapeutic interventions with treatment‐as‐usual (TAU; which included various kinds of psychotherapy), waiting list, no treatment or active treatments in samples of all ages, in any setting, with a formal diagnosis of BPD. The primary outcomes were BPD symptom severity, self‐harm, suicide‐related outcomes, and psychosocial functioning. There were 11 secondary outcomes, including individual BPD symptoms, as well as attrition and adverse effects.

Data collection and analysis

At least two review authors independently selected trials, extracted data, assessed risk of bias using Cochrane's 'Risk of bias' tool and assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach. We performed data analysis using Review Manager 5 and quantified the statistical reliability of the data using Trial Sequential Analysis.

Main results

We included 75 randomised controlled trials (4507 participants), predominantly involving females with mean ages ranging from 14.8 to 45.7 years. More than 16 different kinds of psychotherapy were included, mostly dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) and mentalisation‐based treatment (MBT). The comparator interventions included treatment‐as‐usual (TAU), waiting list, and other active treatments. Treatment duration ranged from one to 36 months.

Psychotherapy versus TAU

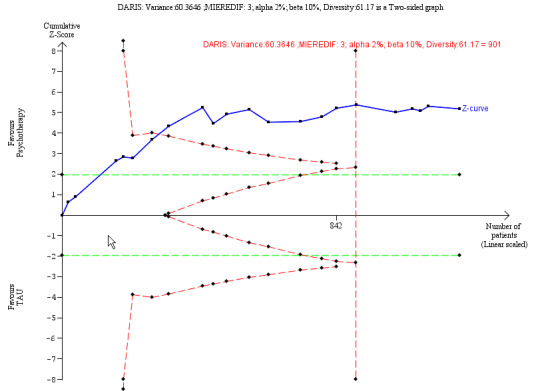

Psychotherapy reduced BPD symptom severity, compared to TAU; standardised mean difference (SMD) −0.52, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.70 to −0.33; 22 trials, 1244 participants; moderate‐quality evidence. This corresponds to a mean difference (MD) of −3.6 (95% CI −4.4 to −2.08) on the Zanarini Rating Scale for BPD (range 0 to 36), a clinically relevant reduction in BPD symptom severity (minimal clinical relevant difference (MIREDIF) on this scale is −3.0 points).

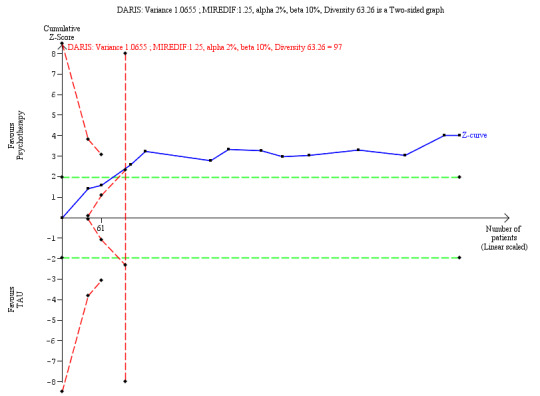

Psychotherapy may be more effective at reducing self‐harm compared to TAU (SMD −0.32, 95% CI −0.49 to −0.14; 13 trials, 616 participants; low‐quality evidence), corresponding to a MD of −0.82 (95% CI −1.25 to 0.35) on the Deliberate Self‐Harm Inventory Scale (range 0 to 34). The MIREDIF of −1.25 points was not reached.

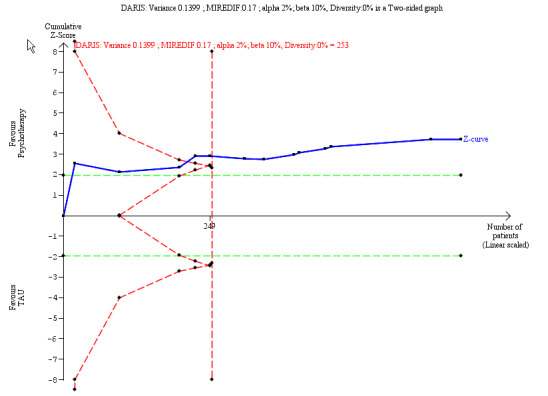

Suicide‐related outcomes improved compared to TAU (SMD −0.34, 95% CI −0.57 to −0.11; 13 trials, 666 participants; low‐quality evidence), corresponding to a MD of −0.11 (95% CI −0.19 to −0.034) on the Suicidal Attempt Self Injury Interview. The MIREDIF of −0.17 points was not reached.

Compared to TAU, psychotherapy may result in an improvement in psychosocial functioning (SMD −0.45, 95% CI −0.68 to −0.22; 22 trials, 1314 participants; low‐quality evidence), corresponding to a MD of −2.8 (95% CI −4.25 to −1.38), on the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (range 0 to 100). The MIREDIF of −4.0 points was not reached.

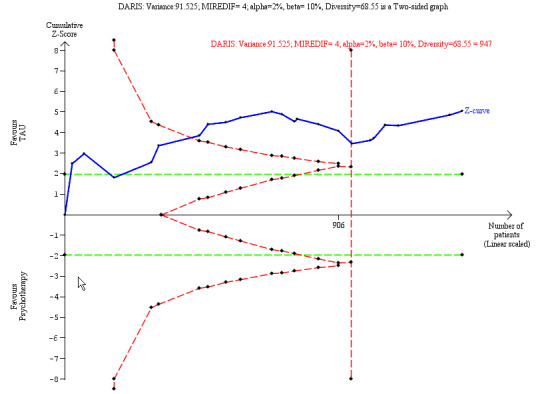

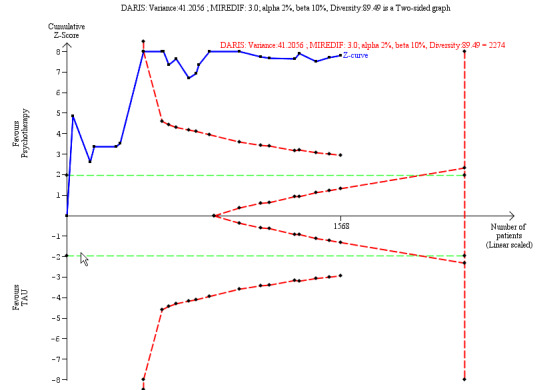

Our additional Trial Sequential Analysis on all primary outcomes reaching significance found that the required information size was reached in all cases.

A subgroup analysis comparing the different types of psychotherapy compared to TAU showed no clear evidence of a difference for BPD severity and psychosocial functioning.

Psychotherapy may reduce depressive symptoms compared to TAU but the evidence is very uncertain (SMD −0.39, 95% CI −0.61 to −0.17; 22 trials, 1568 participants; very low‐quality evidence), corresponding to a MD of −2.45 points on the Hamilton Depression Scale (range 0 to 50). The MIREDIF of −3.0 points was not reached.

BPD‐specific psychotherapy did not reduce attrition compared with TAU. Adverse effects were unclear due to too few data.

Psychotherapy versus waiting list or no treatment

Greater improvements in BPD symptom severity (SMD −0.49, 95% CI −0.93 to −0.05; 3 trials, 161 participants), psychosocial functioning (SMD −0.56, 95% CI −1.01 to −0.11; 5 trials, 219 participants), and depression (SMD −1.28, 95% CI −2.21 to −0.34, 6 trials, 239 participants) were observed in participants receiving psychotherapy versus waiting list or no treatment (all low‐quality evidence). No evidence of a difference was found for self‐harm and suicide‐related outcomes.

Individual treatment approaches

DBT and MBT have the highest numbers of primary trials, with DBT as subject of one‐third of all included trials, followed by MBT with seven RCTs.

Compared to TAU, DBT was more effective at reducing BPD severity (SMD −0.60, 95% CI −1.05 to −0.14; 3 trials, 149 participants), self‐harm (SMD −0.28, 95% CI −0.48 to −0.07; 7 trials, 376 participants) and improving psychosocial functioning (SMD −0.36, 95% CI −0.69 to −0.03; 6 trials, 225 participants). MBT appears to be more effective than TAU at reducing self‐harm (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.80; 3 trials, 252 participants), suicidality (RR 0.10, 95% CI 0.04, 0.30, 3 trials, 218 participants) and depression (SMD −0.58, 95% CI −1.22 to 0.05, 4 trials, 333 participants). All findings are based on low‐quality evidence. For secondary outcomes see review text.

Authors' conclusions

Our assessments showed beneficial effects on all primary outcomes in favour of BPD‐tailored psychotherapy compared with TAU. However, only the outcome of BPD severity reached the MIREDIF‐defined cut‐off for a clinically meaningful improvement. Subgroup analyses found no evidence of a difference in effect estimates between the different types of therapies (compared to TAU) .

The pooled analysis of psychotherapy versus waiting list or no treatment found significant improvement on BPD severity, psychosocial functioning and depression at end of treatment, but these findings were based on low‐quality evidence, and the true magnitude of these effects is uncertain. No clear evidence of difference was found for self‐harm and suicide‐related outcomes.

However, compared to TAU, we observed effects in favour of DBT for BPD severity, self‐harm and psychosocial functioning and, for MBT, on self‐harm and suicidality at end of treatment, but these were all based on low‐quality evidence. Therefore, we are unsure whether these effects would alter with the addition of more data.

Plain language summary

Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder

Background

People affected by borderline personality disorder (BPD) often have difficulties with controlling their impulses and emotions. They may have a poor self‐image, experience rapid changes in mood, harm themselves and find it hard to engage in harmonious interpersonal relationships. Different types of psychological treatments ('talking treatments') have been developed to help people with BPD. The effects of these treatments must be investigated to decide how well they work and if they can be harmful.

Objective

This review summarises what we currently know about the effect of psychotherapy in people with BPD.

Methods

We compared the effects of psychological treatments on people affected by BPD who did not receive treatment or who continued their usual treatment, were on a waiting list or received active treatment.

Findings

We searched for relevant research articles, and found 75 trials (4507 participants, mostly female, mean age ranging from 14.8 to 45.7 years). The trials examined a wide variety of psychological treatments (over 16 different types). They were mostly conducted in outpatient settings, and lasted between one and 36 months. Dialectical behaviour Therapy (DBT) and Mentalisation‐Based Treatment (MBT) were the therapies most studied.

Psychotherapy compared with usual treatment

Psychotherapy reduced the severity of BPD symptoms and suicidality and may reduce self‐harm and depression whilst also improving psychological functioning compared to usual treatment. DBT may be better than usual treatment at reducing BPD severity, self‐harm and improving psychosocial functioning. Similarly, MBT appears to be more effective than usual treatment at reducing self‐harm, suicidality and depression. However, these findings were all based on low‐quality evidence and therefore we are uncertain whether or not these results would change if we added more trials. Most trials did not report adverse effects, and those that did, found no obvious unwanted reactions following psychological treatment. The majority of trials (64 out of 75) were funded by grants from universities, authorities or research foundations. Four trials reported that no funding was received. For the remaining trials (7), funding was not specified.

Psychotherapy versus waiting list or no treatment

Psychotherapy was more effective than waiting list at improving BPD symptoms, psychosocial functioning, and depression, but there was no clear difference between psychotherapy, and waiting list for outcomes of self‐harm, and suicide‐related outcomes.

Conclusions

In general, psychotherapy may be more effective than usual treatment in reducing BPD symptom severity, self‐harm, suicide‐related outcomes and depression, whilst also improving psychosocial functioning. However, only the decrease in BPD symptom severity was found to be at a clinically important level. DBT appears to be better at reducing BPD severity, self‐harm, and improving psychosocial functioning compared to usual treatment and MBT appears more effective than usual treatment at reducing self‐harm and suicidality. However, we are still uncertain about these findings as the quality of the evidence is low.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Psychotherapy versus treatment‐as‐usual.

| Psychotherapy versus treatment‐as‐usual | ||||||

|

Patient or population: borderline personality disorder Settings: inpatient and outpatient Intervention: psychotherapy Comparison: treatment‐as‐usual (TAU) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect(95% CI) |

Number of participants (RCTs) |

Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| TAU | Psychotherapy | |||||

|

BPD symptom severity Measured by: clinicians and self‐rated Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.52 SD lower (0.70 lower to 0.33 lower) | ‐ | 1244 (22 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea |

The SMD of −0.52 corresponds to −3.6 on the Zanarini BPD scale. The MIREDIF on this scale is 3.0 points TSA adjusted Cl = −5.49 to −1.90 on the Zanarini BPD scale TSA RIS = 901 |

|

Self‐harm (frequency) Measured by: clinicians and self‐rated Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.32 SD lower (0.49 lower to 0.14 lower) | ‐ | 616 (13 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | The SMD of −0. 32 corresponds to −0.82 on the DSHI. The MIREDIF on this scale is −1.25 points (½ SD) TSA adjusted CI = −0.59 to −0.08 on the DSHI TSA RIS = 97 |

|

Suicide‐related outcomes (suicidality) Measured by: clinicians and self‐rated Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.34 SD lower (0.57 lower to 0.11 lower) | ‐ | 666 (13 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b |

The SMD of −0. 34 corresponds to −0.11 on the SASII. The MIREDIF on this scale is −0.17 points (½ SD) TSA adjusted CI = −0.18 to −0.04 on the SASII TSA RIS = 253 |

|

Psychosocial functioning Measured by: clinicians and self‐rated Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.45 SD lower (0.68 lower to 0.22 lower) | ‐ | 1314 (22 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | The SMD of −0.45 corresponds to −2.8 on the GAF. The MIREDIF on this scale is −4.0 points TSA adjusted CI = −3.97 to −1.94 on the GAF TSA RIS = 947 |

|

Depression Measured by: clinicians and self‐rated Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.39 SD lower (0.61 lower to 0.17 lower) | ‐ | 1568 (22 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowa,b,c | The SMD of ‐0.45 corresponds to −2.45 on the Hamilton Depression Scale. The MIREDIF on this scale is 3.0 points TSA adjusted CI = −3.34 to −1.72 on the Hamilton Depression Scale TSA RIS = 2274 |

|

Attrition Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

328 per 1000 | 328 per 1000 (95% CI 56 fewer to 66 higher) | RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.20) | 2225 (32 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | ‐ |

|

Adverse effects Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

74 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (95% CI 41 fewer to 65 higher) | RR 0.92 (95% CI 0.45 to 1.88) | 381 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; DSHI: Deliberate Self‐Harm Inventory; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning scale; MIREDIF: Minimum relevant difference; RCTs: Randomised controlled trials; RIS: Required information size; RR: Risk Ratio; SASII: Suicide Attempt Self‐Injury Interview; SD: Standard deviation; SMD: Standardised mean difference; TAU: treatment‐as‐usual; TSA: Trial Sequential Analysis | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

aWe downgraded the quality of this evidence by one level due to risk of bias (other bias). bWe downgraded the quality of this evidence by one level due to imprecision. cWe downgraded the quality of this evidence by one level due to high heterogeneity.

Summary of findings 2. Psychotherapy versus waiting list or no treatment.

| Psychotherapy versus waiting list or no treatment | ||||||

|

Patient or population: borderline personality disorder Settings: inpatient and outpatient Intervention: psychotherapy Comparison: waiting list or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) |

Number of participants (RCTs) |

Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Waiting list or no treatment | Psychotherapy | |||||

|

BPD symptom severity Measured by: clinicians and self‐rated Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.49 SD lower (0.93 lower to 0.05 lower) | ‐ | 161 (3 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | An SMD of 0.49 represents a moderate effect. |

|

Self‐harm Measured by: clinicians and self‐rated Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was0.17 SD lower (0.52 lower to 0.18 higher) | ‐ | 128 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | An SMD of 0.17 represents a small effect. |

|

Suicide‐related outcomes Measured by: self‐rated Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 5.62 SD lower (16.39 lower to 5.16 higher) | ‐ | 108 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowa,b,c |

An SMD of 5.62 represents a large effect. |

|

Psychosocial functioning Measured by: clinicians and self‐rated Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.56 SD lower (1.01 lower to 0.11 lower) | ‐ | 219 (5 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | An SMD of 0.56 represents a moderate effect. |

|

Depression Measured by: clinicians and self‐rated Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 1.28 SD lower (2.21 lower to 0.34 lower) | ‐ | 239 (6 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | An effect size of 1.28 represents a large effect. |

|

Attrition Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

81 per 1000 | 147 per 1000 (95% CI 118 fewer to 74 higher) | RR 0.55 (95% CI 0.20 to 1.50) | 144 (3 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowa,b,c | ‐ |

| Adverse effects (not measured | See comments | See comments | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No studies were found that assessed this outcome |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RCTs: Randomised controlled trials; RR: Risk ratio; SMD: Standardized mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

aWe downgraded the quality of this evidence by one level due to risk of bias. bWe downgraded the quality of this evidence by one level due to imprecision (there was a wide CI). cWe downgraded the quality of this evidence by one level due to inconsistency.

Summary of findings 3. Dialectical behavioural therapy or mentalisation‐based therapy versus treatment‐as‐usual.

| Dialectical behavioural therapy or mentalisation‐based therapy versus treatment‐as‐usual | ||||||

|

Patient or population: borderline personality disorder Settings: inpatient and outpatient Intervention: dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) or mentalisation‐based therapy (MBT) Comparison: treatment‐as‐usual (TAU) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) |

Number of participants (RCTs) |

Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| TAU | DBT or MBT | |||||

| DBT | ||||||

|

BPD severity Measured by: clinicians Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.60 SD lower (1.05 lower to 0.14 lower) | ‐ | 149 (3 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | An SMD of 0.60 represents a moderate effect. |

|

Self‐harm Measured by: clinicians Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.28 SD lower (0.48 lower to 0.07 lower) | ‐ | 376 (7 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | An SMD of 0.28 represents a small effect. |

|

Psychosocial functioning Measured by: clinicians and self‐rated Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.36 SD lower (0.69 lower to 0.03 lower) | ‐ | 225 (6 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b, | An SMD of 0.36 represents a small effect. |

| MBT | ||||||

|

Self‐harm Measured by: clinicians Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

631 per 1000 | 240 per 1000 (95% CI 334 fewer to 126 fewer) | RR 0.62 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.80) | 252 (3 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | ‐ |

|

Suicide‐related outcomes Measured by: clinicians Timing of outcome assessment: end of treatment |

298 per 1000 | 268 per 1000 (95% CI 286 fewer to 209 fewer) | RR 0.10 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.30) | 218 (3 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; DBT: Dialectical behavioural therapy; MBT: Mentalisation‐based therapy; RCTs: Randomised controlled trials; RR: Risk ratio; SMD: Standardized mean difference; TAU: Treatment‐as‐usual | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

aWe downgraded the quality of this evidence by one level due to risk of bias. bWe downgraded the quality of this evidence by one level due to imprecision (there was a wide CI).

Background

Description of the condition

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a condition first formally described in the 20th century (Gunderson 2009). Historically, the term BPD was coined by Adolph Stern to describe a condition in the 'borderland' between psychosis and neurosis (Stern 1938). Subsequent psychoanalytic contributions (especially that of Kernberg 1975) have reaffirmed this distinction, emphasising that the capacity to test reality remains grossly intact but is subject to subtle distortions, especially under stress. The current evidence supports a biopsychological model of the aetiological factors in BPD, all of which may contribute. It is assumed that there is an interaction between the experience of adverse effects during childhood (like neglect, emotional or sexual abuse), and genetic or biological factors. Relevant biological factors include neurobiological structures, such as reduced aymgdala volume, increased volume of the pituitary gland, reduced grey matter volume in the anterior cingulate gyrus, posterior cingulate gyrus or hippocampus, and reduction in size of the right parietal cortex (Leichsenring 2011; Lieb 2004), and neurobiological dysfunctions (especially of the serotonergic system). In combination with psychosocial factors, personality traits (e.g. neuroticisms), personality functioning (self and interpersonal) and proneness to react highly emotionally may contribute to the core components of BPD, like affective and behavioural dysregulation, and disturbed relatedness (Leichsenring 2011; Lieb 2004).

According to current diagnostic criteria, BPD is characterised by a pervasive pattern of instability in affect regulation, impulse control, interpersonal relationships and self‐image (APA 2013; WHO 1993). Clinical hallmarks include, amongst other things, emotional dysregulation, impulsivity, anger, repeated self‐injury and chronic suicidal tendencies, together with inner emptiness and fear of abandonment (Dimaggio 2007; Fonagy 2009; Gunderson 2018; Karterud 2019; Lieb 2004). Despite the difficulties and controversies in defining and delimiting the condition, BPD is being vigorously researched still, not only in adults but also in childhood and adolescence (Chanen 2017), and is the only specific personality disorder to be carried over to the new, eleventh edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐11) (Bach 2018; WHO 2018). The importance of effective treatments for BPD stems from the considerable psychological suffering of the persons concerned (Stiglmayr 2005; Zanarini 1998), the burden incurred on their families and significant others (Bailey 2014; Bateman 2019a), the significant impact on mental health services (Cailhol 2015; Hörz 2010; Soeteman 2008a; Tyrer 2015; Zanarini 2004; Zanarini 2012), and not least the association of BPD with debilitating functional impairments and premature death (Fok 2012; Gunderson 2011a; Gunderson 2011b; Kjær 2018; Niesten 2016; Skodol 2002; Soeteman 2008b).

The definition of BPD in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), Fifth Edition (DSM‐5; APA 2013), Fourth Edition (DMS‐IV; APA 1994) and Fourth Edition Text Revision (DSM‐IV‐TR; APA 2000) comprises nine criteria that cover the features mentioned above. At least five criteria should be met for a definitive, categorical diagnosis of BPD to be made, and four criteria for a probable diagnosis (see Appendix 1). In the alternative diagnostic classification system of the World Health Organization (WHO), the ICD, which is currently in its tenth edition (ICD‐10; WHO 1993), the relating condition is referred to as "Emotionally unstable personality disorder (F60.3)", of which there is an impulsive type (F60.30) and a borderline type (F60.31; see Appendix 2). The latter essentially overlaps with the DSM‐IV definition and DSM‐5 criteria (Ottosen 2002).

In addition to categorical classification systems, the DSM‐5 also includes an alternative model for personality disorders (Section III: "Emerging Measures and Models"). This hybrid model is made up of two dimensions: 1) the severity of impairment in personality (self and interpersonal); and 2) the domains of personality traits (i.e. negative affectivity, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, psychoticism; APA 2013, Section III). The ICD‐11 (which will be in effect from 2022; WHO 2018) is also moving towards a dimensional approach, where the different types of personality disorders are being replaced with a model that focuses on the severity of core personality functioning instead. However, a specifier relating to a "Borderline pattern" will be retained. Preliminary studies have found that there is a substantial overlap between the current categorical and alternative models found in the DSM‐5 (Bach 2016; Bach 2018; Sellbom 2014), as well as overlap between the dimensional models of the DSM‐5 and ICD‐11 (Bach 2018). Therefore, sufficient continuity between current categorical and upcoming dimensional models is warranted. The findings of this review will be applicable also to populations diagnosed with the DSM‐5 Section III Hybrid BPD type and ICD‐11 Borderline pattern qualifier.

The prevalence of BPD in the general population is estimated to be 1.8 % (95% CI 1.2% to 2.5%) (Winsper 2020). In clinical populations, BPD occurs frequently (Munk‐Jørgensen 2010), with trials reporting a prevalence ranging from 9.3% to 46.3% and a mean point prevalence across studies of 28.5% (Torgersen 2012). BPD usually has its onset in childhood and adolescence, and younger people are affected as much as or even more often than adults (Neacsiu 2017). BPD has been found to peak around 14 to 17 years of age with a linearly decline into adulthood; however, it continues throughout the lifespan and can also be found in older people (Chanen 2007; Newton‐Howes 2015; Sharp 2018; Videler 2019). Though BPD is predominantly diagnosed in women (75%; APA 2000; APA 2013), it is estimated to be almost equally frequent in men in epidemiological studies (Lenzenweger 2007; Ten Have 2016; Torgersen 2001; Torgersen 2012). Moreover, BPD commonly co‐occurs with mood disorders, substance use disorder, eating disorders, post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and other specific personality disorders (Coid 2006; Lenzenweger 2007; Stepp 2012; Storebø 2014; Tomko 2014). Suicidal behaviour is reported to occur in up to 84% of people diagnosed with BPD (Goodman 2012; Soloff 2002), and it is estimated that up to 10% of those affected by BPD will die from suicide (Paris 2019). Comorbid mood disorders or substance use disorders are the most common risk factors associated with successful suicide attempts (Black 2004; Doyle 2016; Yen 2004).

Although the short‐ to medium‐term social functioning of people with BPD is poor, diagnostic remission is around 85% within 10 years (Gunderson 2011b; Zanarini 2007). Here, however, remission only means that diagnostic criteria are not fulfilled; it does not indicate the absence of any symptoms. Indeed, whereas acute symptoms — such as self‐mutilation, help‐seeking suicide threats or attempts and impulsivity — decrease with time in most cases, affective symptoms reflecting areas of chronic dysphoria, such as chronic feelings of emptiness, intense anger or profound feelings of abandonment, largely remain (Zanarini 2007). Therefore, the majority of people with BPD still have significant levels of symptoms and experience severe and persistent impairment in social functioning over time (Kongerslev 2015; Ng 2016). Risk factors for poor, long‐term outcomes are comorbid substance use disorders, PTSD, and anxiety cluster disorders (Zanarini 2005; Zanarini 2007), as well as a family history of psychiatric disorder (especially mood disorders and substance use disorders), demographic issues such as older age, longer treatment history, pathological childhood experiences, temperament issues and adult psychosocial functioning (Chanen 2012; De Fruyt 2014; Kongerslev 2015; Zanarini 2007).

People with BPD have severe difficulties in achieving and maintaining vocational and social functioning over time (Hastrup 2019a; Paris 2014; Zanarini 2010). Furthermore, treatment‐seeking people with personality disorders, such as BPD, pose a high economic burden on society (Hastrup 2019b; Van Asselt 2007). Effective treatments could potentially decrease the high costs associated with the condition (Soeteman 2008a). The problem of deliberate self‐harm is also a particular issue within this group (Ayodeji 2015; Kongerslev 2015; Linehan 1997; Rossouw 2012b). In medical settings, people diagnosed with BPD often present after self‐harming behaviour or in suicidal crisis and are treated in emergency settings, often involving repeated psychiatric hospitalisations (Cailhol 2015).

In summary, BPD is a condition that has been studied extensively. It has a major impact on health facilities as those affected often present in crisis. Recovery from symptoms or functional impairment (or both) was previously considered likely for only a small percentage of people diagnosed with BPD. However, the long‐term course, in terms of symptomatic recovery, is favourable (Gunderson 2011b; Zanarini 2007; Zanarini 2012). Nonetheless, people diagnosed with BPD continue to have considerable interpersonal and functional problems, and sustainable recovery appears difficult to attain (Biskin 2015; Kongerslev 2015; Rossouw 2012b).

Description of the intervention

About three‐quarters of people with BPD present to mental healthcare professionals (Tomko 2014), and they are even more likely to do so than people with mood, anxiety, or other personality disorders (Ansell 2007). Most will receive psychological interventions, because drugs are not effective for the BPD core symptoms (Goodman 2010; Tomko 2014), and these psychosocial interventions will often be provided for a relatively long periods of time (e.g. for a period of one year or longer) (Ansell 2007; Zanarini 2015).

A broad range of psychotherapies exist for BPD. The therapy can be delivered in individual or group formats, or a combination of these two treatment modalities. As for most other mental disorders, psychological interventions can be based on the traditional, major psychotherapeutic schools such as psychodynamic psychotherapy, cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) or client‐centred/humanistic therapy. In addition, several specific treatment approaches have been developed within recent decades to meet the particular challenges of treating BPD. These disorder‐specific approaches are usually precisely structured and manualised (De Groot 2008; Levy 2006; Weinberg 2011). Strategies are provided for addressing interpersonal challenges, such as emotional dysregulation and impulsivity, which are core problems for people diagnosed with BPD and could lead to difficulties in forming a therapeutic alliance. Most BPD‐specific psychological interventions involve multimodal therapy, treatment contracts, actively taking measures to minimise premature non‐completion of treatment, providing a crisis intervention protocol and encouraging the affected one's sense of agency (Bateman 2018; Clarkin 2012; De Groot 2008; Kongerslev 2015; Livesley 2012; Weinberg 2011). They are typically highly focused on affect and the therapeutic relationship, with a relatively active therapist implementing interventions within a supportive and validating atmosphere (Bateman 2018; Clarkin 2012; De Groot 2008; Kongerslev 2015; Livesley 2012; Weinberg 2011). Eclectic therapy is an open, integrative form of psychotherapy, which adapts to the unique needs of each specific client, depending on the problem, the treatment goals and the person’s expectations and motivation (Sansone 2006). Eclectic therapies integrate elements from different forms of psychotherapy.

Among the specific psychological interventions for people diagnosed with BPD, the most commonly used are: transference‐focused therapy (Clarkin 1999; Yeomans 2015); mentalisation‐based treatment (Bateman 2004; Bateman 2006; Bateman 2016); dialectical behaviour therapy (Linehan 1993a; Linehan 2015b); cognitive analytic therapy (Chanen 2014; Ryle 1997); schema‐focused therapy (Arntz 2009; Young 2003); and the systems training for emotional predictability and problem‐solving (STEPPS) (Black 2009). Most of these treatments are designed as outpatient treatments of six to 24 months duration, with once or twice weekly individual sessions. Some also include additional group therapy sessions, inpatient or day‐hospital therapeutic community treatment and psychoeducation. Other potential therapies for BPD include the likes of CBT (Beck 2003), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Gratz 2006), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT; Markowitz 2006), and psychodynamic psychotherapy (e.g. psychoanalytic‐interactional therapy; Streeck 2009). Broadly speaking, psychodynamic therapies aim to help people understand and reflect on their inner mental processes and make links between their past and current difficulties. Treatments based on CBT place emphasis on self‐directed learning processes: people are encouraged to identify their core beliefs; evaluate and modify their behaviour accordingly; and gain new experiences. Psychotherapy is defined as the "treatment of mental illness or emotional disturbances primarily by verbal or nonverbal communication" (quote; NLM 2009).

Dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT; Linehan 1993a) is a highly structured and complex psychological therapy that was developed using some of the principles of CBT in combination with mindfulness‐based and Zen‐Buddhistic and dialectical thinking strategies. It aims to change behaviour and enhance the ability to tolerate difficult or painful feelings by focusing on improving skills in stress tolerance, emotion regulation, interpersonal behaviour, and mindfulness.

Mentalisation‐based therapy (Bateman 2004; Bateman 2016) is a complex psychodynamic and attachment‐based psychological therapy programme that aims to increase the reflective functioning or mentalising capacity of the individual, helping the person to understand and recognise the feelings they evoke in others and the feelings they experience themselves, as well as improving the capacity for emotion regulation in interpersonal relations.

Schema‐focused therapy (SFT; Young 2003) draws from both cognitive‐behavioural and psychoanalytic theories and helps people with BPD to identify their self‐defeating core themes arising from unmet emotional needs in childhood and presenting as maladaptive coping styles in adulthood. The goal of SFT is to aid people affected by BPD in getting their needs met in adaptive ways.

Transference‐focused psychotherapy (TFP; Clarkin 1999) strives to achieve integrated representations of self and others, modification of primitive defence operations, and resolution of identity diffusion by analysis of the transference within the therapeutic relationship. Primitive object relations, which can be polarised and split, may be transformed to advanced or mature object relations characterised by more integrated object relations. TFP relies on techniques of clarification, confrontation and transference interpretation within the relationship between patient and therapist.

Cognitive analytic therapy (CAT; Ryle 1997) assumes that people with BPD typically experience rapid switching from one self‐state to another in a dissociate manner. The aim is to work with the patient cognitively, to identify procedural sequences, chains of events, emotions, thoughts and motivations, in order to understand how a target problem (like self‐harm) is established and maintained, and to identify reciprocal roles (i.e. how early experiences are replayed later in life).

Systems training for emotional predictability and problem‐solving (STEPPS; Black 2009) combines group‐based psychoeducation with skills training, and targets biased social cognition driven by cognitive filters or schemas.

Dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy (DDP) is a manualised, 12‐ to 18‐month treatment for adults diagnosed with BPD and other complex co‐occurring disorders such as substance use disorders, additional personality disorders or eating disorders (Gregory 2008; Gregory 2010). The DDP model of BPD pathology draws on and combines elements of translational neuroscience, object relations theory, and the philosophy of deconstruction. The aim of DDP is to help people with BPD to connect with and verbalise their experience better, as well as to foster better interpersonal relations and self‐acceptance. DDP was used in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) conducted by its developer (Gregory 2008).

Relaxation techniques and patient education programmes will be considered their own intervention class (i.e. not CBT or psychoanalytically based), as long as they are not explicitly grounded in or taken from a specific treatment approach (such as psychoeducation according to the DBT approach, CBT, or the SFT approach, etc.).

How the intervention might work

Evidence‐based psychological therapies are based on assumptions about causality, core symptoms, and maintenance of the disorder (Kazdin 2004; Livesley 2003; Livesley 2004). The various psychotherapeutic approaches to BPD claim different mechanisms of action according to their respective models of causation (Gunderson 2018; Huprich 2015; Livesley 2004; Livesley 2016). However, they also contain a number of common elements that can account for why a number of seemingly different approaches appear to be effective in ameliorating BPD symptoms (Bateman 2015; Fonagy 2014; Kongerslev 2015; Weinberg 2011), including: a clear and highly structured treatment framework; an explicit model of BPD symptomatology; a consistent focus on the therapeutic relationship, affect regulation, tolerance of emotional states, and biases in social cognition; a high priority given to self‐harm and suicidal behaviour; active therapists who deliver both support and validation as well as explorative and change‐oriented interventions; mix of treatment formats (e.g. includes both individual and group therapy); and therapist support in the form of supervision and regular meetings. The symptoms of BPD are addressed using the following therapeutic approaches. Following Weinberg 2011:

'emotional dysregulation' (e.g. intense anger and affective instability) is addressed through attention to affect, including raising awareness of emotional states, their triggers, and enhancing tolerance and regulative strategies;

'behavioural dysregulation' (e.g. impulsivity, self‐harm and suicidal behaviours) is addressed through change‐oriented interventions, including, for example, challenging negative thoughts, skills training, behavioural experiments, praise, and limit setting; and

'interpersonal dysfunction' (e.g. unstable relationships and stress‐related paranoid ideation) is treated using interventions that enhance the social‐cognitive (or mentalising) capacities of the BPD patient, through making basic and often negatively biased automatic assumptions explicit and more realistic or adaptive, and through paying attention to the establishment and maintenance of a safe and sound working alliance within the therapy sessions.

There is a risk that psychological therapies might not be helpful for all people affected by BPD, either due to the interventions delivered or through factors in the therapeutic relationship (Kongerslev 2015; Lilienfeld 2007; Parry 2016), and very little research has been done on this in people with BPD. The effectiveness of the therapy depends on the skills of the therapist to create the possibility for change with each patient. There is, therefore, the added complexity that the relationship or working alliance between the therapist and the patient itself is an ‘active ingredient’ of the therapy and that the quality of this relationship is an important predictor of outcome (Horvath 2011; Norcross 2011). There is no guarantee that the therapy will deliver what was specified in the manual or what was investigated in a randomised clinical trial (Parry 2016).

Why it is important to do this review

People with BPD and their family and friends experience high levels of psychological suffering. BPD is associated with considerable social costs in terms of service use (e.g. presentation to emergency clinics due to self‐harm or suicidal crises and repeated hospitalisations) and poor psychosocial functioning (e.g. inability to complete education or get/maintain a job). Consequently, identification of effective psychological therapies for BPD is important (Stoffers‐Winterling 2012).

Our review aims to provide a systematic summary of the evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in order to help people with BPD, their family and friends, mental healthcare workers, and policy and decision managers in general, to make informed decisions about evidence‐based treatment for BPD.

This review is an update of two previous Cochrane Reviews on psychological therapies for BPD (Binks 2006; Stoffers‐Winterling 2012). In addition to updating the two former Cochrane Reviews, our study also seeks to address some of the methodological limitations of both past and current reviews (Bateman 2015; Cristea 2017; Kliem 2010), by using updated methods, including a more comprehensive search strategy. We also had a new protocol published prior to conducting this review (Storebø 2018).

Objectives

To assess the beneficial and harmful effects of psychological therapies for people with BPD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

Persons of all ages, in any setting, with a formal, categorical diagnosis of BPD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) Third Edition (DSM‐III; APA 1980), Third Edition Revised (DSM‐III‐R; APA 1987), Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV; APA 1994), Fourth Edition Text Revision (DSM‐IV‐TR; APA 2000), and Fifth Edition (DSM‐5; APA 2013), and the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) 10th version (WHO 1993), with or without comorbid conditions.

To meet our inclusion criteria, at least 70% of participants of a respective trial had to have a formal diagnosis of BPD. We included trials involving subsamples of people with BPD when data on those with BPD were provided separately (we asked for separate data from trials including less than 70% BPD participants). We did not include trials that focused on people with mental impairment, organic brain disorder, dementia or other severe neurologic/neurodevelopmental diseases.

Types of interventions

Any defined psychological intervention regardless of theoretical orientation (e.g. psychodynamic therapy, CBT, systemic therapy or eclectic therapies designed for BPD treatment), in any kind of treatment setting (e.g. inpatient, outpatient or day clinic), compared to:

control interventions, such as standard care, treatment‐as‐usual (TAU), waiting list or no treatment; and

specific psychotherapeutic interventions (that were well defined and theory driven).

We divided control interventions into two categories: The first category was “waiting list/no treatment”: participants did not receive any treatment or support from the study centre (like, e.g. clinical management, regular medical review, or support/encouragement to find a therapist outside the study centre). The second category, “TAU” included any other kinds of controls: participants were either free to use any treatment except from the respective experiential treatment (optional TAU), or they received usual community treatment, or standardised usual care (obligatory TAU).

We pooled the different types of TAU into one comparison in our main analyses, and compared the effects between the two types of TAU as well as the effect observed by comparison to TAU controls to the effects of comparisons to waiting‐list/no treatment controls (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

We allowed concomitant treatments provided they were applied to both treatment conditions.

We accepted trials with active controls, including relaxation techniques such as autogenic training or meditation regimens, or patient education programmes such as self‐management and community‐based education programmes.

Types of outcome measures

Outcomes were either self‐rated by the persons with BPD or observer‐rated by clinicians, with clinician‐rated outcomes being preferred. We included only adequately validated measures (plus spontaneous reporting of adverse effects).

We analysed all outcomes at post‐treatment and at six months follow‐up or longer.

Primary outcomes

BPD symptom severity, assessed by, for example, the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (Zan‐BPD; Zanarini 2003a); the Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index, Fourth version (BPDSI‐IV; Arntz 2003) or the Clinical Global Impression Scale for people with Borderline Personality Disorder (CGI‐BPD; Perez 2007).

Self‐harm, in terms of the proportion of participants with self‐harming behaviour, or assessed by, for example, the Deliberate Self‐harm Inventory (DSHI; Gratz 2001) or the Self‐harm behaviour Questionnaire (SHBQ; Guttierez 2001).

Suicide‐related outcomes, assessed by, for example, the Suicidal Behaviours Questionnaire (SBQ; Osman 2001) or the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI; Beck 1979), or in terms of the proportion of participants with suicidal acts.

Psychosocial functioning, assessed by, for example, the Global Assessment Scale (GAS; Endicott 1976), the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF; APA 1987) or the Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ; Tyrer 2005).

Secondary outcomes

Anger, assessed by, for example, the Hostility subscale of the Symptom Checklist ‐ 90 ‐ Revised (SCL‐90‐R; Derogatis 1994) or the State‐Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI; Spielberger 1988).

Affective instability, assessed by, for example, the relevant item or subscale on the Zan‐BPD (Zanarini 2003a), CGI‐BPD (Perez 2007) or BPDSI‐IV (Arntz 2003).

Chronic feelings of emptiness, assessed by, for example, the relevant item or subscale on the Zan‐BPD (Zanarini 2003a), CGI‐BPD (Perez 2007) or BPDSI‐IV (Arntz 2003).

Impulsivity, assessed by, for example, the Barrett Impulsiveness Scale (BIS; Barrett 1995), or the Anger, Irritability and Assault Questionnaire (AIAQ; Coccaro 1991).

Interpersonal problems, assessed by, for example, the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP; Horowitz 1988), or the relevant item or subscale on the Zan‐BPD (Zanarini 2003a), CGI‐BPD (Perez 2007), BPDSI‐IV (Arntz 2003), or SCL‐90‐R (Derogatis 1994).

Abandonment, assessed by, for example, the relevant item or subscale on the Zan‐BPD (Zanarini 2003a), CGI‐BPD (Perez 2007) or BPDSI‐IV (Arntz 2003).

Identity disturbance, assessed by, for example, the relevant item or subscale on the Zan‐BPD (Zanarini 2003a), CGI‐BPD (Perez 2007) or BPDSI‐IV (Arntz 2003).

Dissociation and psychotic‐like symptoms, assessed by, for example, the Dissociative Experience Scale (DES; Bernstein 1986), or the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Overall 1962).

Depression, assessed by, for example, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck 1961) or the Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; Montgomery 1979).

Attrition, in terms of participants lost after randomisation in each group.

Adverse effects, measured by the use of standardised psychometric rating scales, such as the Systematic Assessment for Treatment Emergent Events (SAFTEE; Levine 1986), or by laboratory values or spontaneous reporting. We defined adverse effects as unfavourable outcomes that occurred during or after psychotherapy but that were not necessarily caused by it (see Chapter 19 in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Peryer 2019. We divided any reported adverse effects into severe and non‐severe, according to the International Committee of Harmonization guidelines (ICH 1996). We defined serious adverse effects as any event that led to death, was life‐threatening, required inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, resulted in persistent or significant disability, or any important medical event that may have jeopardised the participant’s health or required intervention to prevent one of the aforementioned outcomes occurring. We considered all other adverse effects to be non‐serious.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the electronic databases and trials registers listed below up to March 2019.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 3), in the Cochrane Library, which includes the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Specialised Register (searched 20 March 2019).

MEDLINE Ovid (1948 to 20 March 2019).

Embase Ovid (1980 to 20 March 2019).

CINAHL EBSCOhost (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1980 to 20 March 2019).

PsycINFO Ovid (1806 to 20 March 2019).

ERIC EBSCOhost (Education Resources Information Center; 1966 to 20 March 2019).

BIOSIS Previews Web of Science Clarivate Analytics (1969 to 20 March 2019).

Web of Science Core Collection Clarivate Analytics (1900 to 20 March 2019).

Sociological Abstracts ProQuest (1952 to 20 March 2019).

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database; lilacs.bvsalud.org/en; searched 20 August 2019).

OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu; searched 20 August 2019).

Library Hub Discover,previously COPAC (Library Hub Discover; searched 20 August 2019).

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses A&I (1743 to 20 March 2019).

DART Europe E‐Theses Portal (www.dart-europe.eu/basic-search.php; searched 20 August 2019).

Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD; www.ndltd.org; searched 20 August 2019).

Australian New Zealand Clinical trials Registry (ANZCTR; www.anzctr.org.au/BasicSearch.aspx; searched 20 August 2019).

Clinicaltrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov; searched 20 March 2019).

EU Clinical trials Register (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/search; searched 20 August 2019).

ISRCTN Registry (www.isrctn.com; searched 20 August 2019).

Be Part of research (www.ukctg.nihr.ac.uk/#popoverSearchDivId; searched 20 August 2019).

WHO International Clinical trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; who.int/ictrp/en; searched 20 March 2019).

The search strategies for all databases can be found in Appendix 3. We did not limit our searches by language, year of publication, or type of publication. We sought translation of the relevant sections of non‐English language articles.

Searching other resources

We handsearched relevant journals, including: Journal of Personality Disorders; American Journal of Psychiatry; JAMA Psychiatry; British Journal of Psychiatry; ACTA Psychiatrica Scandinavica; Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; Personality Disorders: Theory, Research and Treatment; and Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. Additionally, we emailed researchers working in the field, to ask for unpublished data. We also checked abstracts of key conferences for BPD (congresses of the European and the International Society for the Study of Personality Disorders; ESSPD and ISSPD, respectively) and asked for any relevant unpublished data. We traced cross‐references from relevant literature. On 13 December 2019, we ran searches to make sure that none of our included trials had been retracted due to error or fraud. In the next update of this review, we will handsearch additional journal titles for relevant trials, (see Differences between protocol and review).

Data collection and analysis

We conducted this review in accordance with the guidelines set out in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019), and performed analyses using the latest version of Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5), Cochrane's statistical software (Review Manager 2014).

We report only the methods used in successive sections below. Planned but unused methods can be found in the protocol, Storebø 2018, and additional Table 4.

1. Unused methods.

| Section | Protocol (Storebø 2018) | Review |

|

Unit of analysis issues

|

Cross‐over trials We would have included cross‐over trials. We planned to include data up to the point of first cross‐over (first period only; Curtin 2002). We did not intend to use data from subsequent periods due to the likelihood of carry‐over effects from the preceding treatment(s). We planned not to combine repeated participant interventions in one meta‐analysis. |

We did not include any cross‐over trial. |

|

Cluster‐randomised trials Had trials used cluster randomisation, we would have anticipated that investigators would have presented their results after appropriately controlling for clustering effects (robust standard errors or hierarchical linear models). If it had been unclear whether a cluster‐randomised trial had used appropriate controls for clustering, we would have contacted the investigators for further information. We would have requested and re‐analysed individual patient data using multilevel models that controlled for clustering, if appropriate controls had not been used. Following this, we would have analysed effect sizes and standard errors in RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2014), using the generic inverse method (Higgins 2011). If there had been insufficient information to control for clustering, we would have entered outcome data using individuals as the units of analysis, and then conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the potential biasing effects of inadequately controlled cluster‐randomised trials (Donner 2002). If individual participant data had not been available, we would have looked for information on intra‐class correlation coefficients to adjust for the potential clustering effects. |

We did not include any cluster‐randomised trial. | |

|

Adjustment for multiplicity We planned to adjust the P values and CIs for multiplicity due to the many secondary outcome comparisons following the method described by Jakobsen 2014. |

We only adjusted the primary outcomes and one secondary outcomes for multiplicity, i.e. those outcomes presented in the SoF table. | |

| Dealing with missing data | Had dichotomous data not been presented on the basis of ITT data, we would have added the number of participants lost in each group to the participants with unfavourable results, acting on the assumption that most people with BPD do not get lost at random. | We were unable to perform this analysis due to insufficient information |

| Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity | We intended to conduct subgroup analyses to make hypotheses about the subgroups mentioned below.

|

We did not conduct these preplanned analyses because of lack of data. |

| Sensitivity analysis | We intended to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the overall pooled effect estimate by removing studies ('outliers') that contributed to heterogeneity. We intended to remove outliers one by one and assess the impact on the overall outcome.

|

We were not able to perform these analyses, due to a lack of sufficient data. |

| TSA | We intended to calculate post hoc, low bias, risk diversity‐adjusted required information size TSA analyses for the primary outcomes. | We were not able to perform these analyses with low risk of bias trials. |

BPD: borderline personality disorder; CI: confidence interval;ITT: intention to treat; TAU: treatment‐as‐usual

Selection of studies

Twelve review authors (OJS, JMSW, BAV, JTM, HEC, AT, CPS, MTK, SSN, MLK, MSJ, EF) worked in six pairs and independently screened titles and abstracts of all records retrieved by the searches. For any record that could have been an eligible RCT, we obtained the full‐text report and assessed it for eligibility against the inclusion criteria (see Criteria for considering studies for this review). During all stages of study selection, we resolved uncertainty or disagreement by consensus. When agreement could not be reached, the review authors discussed disagreements and consulted a third review author (KL, OJS, JMSW or ES).

We list apparently relevant RCTs that did not fulfil the inclusion criteria, along with reasons for their exclusion, in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables. We used Covidence software to keep track of appraised trials and decisions. To ensure transparency of study selection, we provided flow charts according to the QUOROM statement, showing how many records have been excluded for a certain reason (Moher 1999).

Data extraction and management

We developed data extraction forms to facilitate standardisation of data extraction. The form was piloted by OJS, SSN, MTK.

Working in pairs, all review authors extracted data independently using the data collection form to ensure accuracy. We resolved disagreements by discussion or by using an arbiter (ES), if required.

OJS, HEC, AT, EF, and JMSW entered data into RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2014). After all data had been entered, another reviewer (JMSW, OJS) re‐checked the data for completeness and accuracy, to make sure the data were complete, correct and appropriately categorised. Any entered data were verified against the original publication, and we updated the list of outcomes (Appendix 4), if necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Using Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011), all review authors assessed the risk of bias in each included trial across the following domains: random sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of outcome assessment; incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting; and other potential sources of bias. Data extractors independently assigned each trial to one of three categories (low risk of bias, unclear (uncertain) risk of bias or high risk of bias), according to guidelines provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), using the criteria set out in Appendix 5. We called upon a third review author (ES) to resolve any ongoing disagreements, when needed.

Considering bias due to a lack of blinding is undoubtedly of importance, but it remains unclear how best to deal with this issue in research practice (Boutron 2008). We decided not to judge the likelihood of detection bias due to inadequate blinding of participants and personnel, as it is almost impossible to blind therapists and people receiving treatment in psychological therapy outcome research. However, we assessed the likelihood of detection bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors.

In accordance with Cochrane’s guidelines (Higgins 2011), we also included other potential sources of bias as a final bias component. Here, we included: the likelihood of performance bias due to inadequate treatment adherence; the likelihood of bias due to different amounts of attention given to the treatment groups (attention bias); and other potential sources of bias, such as allegiance bias. We defined allegiance bias as a therapist’s personal belief both in the superiority and the efficacy of a particular treatment. This belief can be based on an education in that particular treatment. This bias is especially strong if the inventor of a treatment is investigating the effects of the particular treatment he/she has invented.

We considered trials with one or more unclear or high risk of bias domains as trials at high risk of bias overall, due to the risk of overestimating beneficial effects and underestimating harmful effects in RCTs with unclear or inadequate methodological quality (Kjaergard 2001; Lundh 2012; Moher 1998; Savović 2012a; Savović 2012b; Schulz 1995; Wood 2008). We defined trials with a low risk of bias in all domains to be at low risk of bias overall.

Measures of treatment effect

Continuous data

For continuous data, we compared the mean score between the two groups to give a mean difference (MD) and presented this with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We used the overall MD, where possible, to combine the same outcome measures from trials. If two or more different instruments were used to measure the same construct, we reported the effect sizes as standardised mean differences (SMD) in the meta‐analysis. We calculated SMDs on the basis of post‐treatment results and, in separate analyses, follow‐up data. We grouped follow‐up data in six‐month intervals (zero to six months, six to 12 months and 12 months and over). Where the direction of a scale was opposite to most of the other scales, we multiplied the corresponding mean values by −1 to ensure adjusted values. If the trials did not report means and standard deviations (SDs) but reported other values like t‐tests and P values, we tried to transform these into SDs.

To identify the minimum relevant clinical difference (MIREDIF), we transformed the SMD to MD, using the scale with the best validity and reliability for the given outcome. For the analyses of the four primary outcomes in the comparison of psychotherapy versus TAU, we transformed SMDs into MDs on the following scales, to assess whether results exceeded the MIREDIF: ZAN‐BPD Scale, Delibarate Self‐Harm Inventory (DSHI), Suicidal Attempt Self Injury Interview (SASII), Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), and the Hamilton Depression scale. We identified a MIREDIF of −3.0 points on the ZAN‐BPD, ranging from 0 to 36 points, based on a trial by Crawford 2018a; a MIREDIF of −1.25 points on the DSHI, ranging from 0 to 34 points, which corresponds to ½ SD based on a trial by Farivar 2004; a MIREDIF of −0.17 points on the Suicidal Attempt Self Injury Interview, ranging from 0 to 4 points, which corresponds to ½ SD based on a trial by Farivar 2004; and a MIREDIF of −4.0 on the GAF scale, ranging from 0 to 100, based on a trial by Amri 2014. The MIREDIF of the Hamilton Depression scale is 3.0 points (NICE CG90). For other outcomes, we provided an interpretation of the effect size using Cohen's D, considering 0.2 as a small effect, 0.5 as a medium effect size, and 0.8 as a large effect size (Cohen 1988).

Dichotomous data

We summarised dichotomous data as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% CIs. The RR is the ratio of the risk of an event in the two groups. We decided to use the RR as it may be easier to interpret than odds ratios (ORs).

Unit of analysis issues

Repeated observations

We calculated trial estimates on the basis of post‐treatment group results. We conducted separate analyses for data from different points of measurement (i.e. post‐treatment, follow‐up data of 0‐ to 6‐month, 6‐ to 12‐month, and above 12‐month intervals, where we used the last measurement within these intervals). If a trial reported data at both 7‐month and 11‐month follow‐up periods, we included both; however, we categorised cases like the 11‐month follow‐up as above 12‐month follow‐up. We did not use interim observations (Thalheimer 2002).

Adjustment for multiplicity

Multiplicity reflects the concern that performing multiple comparisons increases the risk of falsely rejecting the null hypothesis. Multiplicity, therefore, may affect the results found within a systematic review and, as a result, needs to be adjusted for. We adjusted the P values and CIs of the primary outcomes and one secondary outcome (depression) for multiplicity using the method described by (Jakobsen 2014).

Dealing with missing data

We tried to obtain any missing data, including incomplete outcome data, by contacting trial authors. We report this information in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

We evaluated the methods used to handle the missing data in the publications and to what extent it was likely that the missing data had influenced the results of outcomes of interest. We calculated effect sizes on the basis of intention‐to‐treat data, if that was possible. If only available case analysis data were reported, we calculated effect sizes on this basis.

We consulted a statistician if data were not reported in an immediately usable way and if data required processing before being analysed. We assessed results derived from statistically processed data in sensitivity analyses. See Sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed trials for clinical homogeneity with respect to type of therapy, therapy setting and control group. We evaluated methodological heterogeneity by comparing the designs of trials. For any trials judged as homogeneous and adequate for pooling, we investigated statistical heterogeneity by both visual inspection of the graphs and the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). We considered I2 values between 0% and 40% as indication of little heterogeneity, between 30% and 60% as indication of moderate heterogeneity, between 50% and 90% as indication of substantial heterogeneity, and between 75% and 100% as indication of considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2019). Along with the size of the I2 scores, we also took into account the P value, CI and the overall number of included trials in the respective analysis when interpreting the values (Deeks 2019).

Assessment of reporting biases

We drew funnel plots (estimated differences in treatment effects against their standard error) and performed Egger's statistical test for small‐study effects for the primary outcomes; asymmetry in the funnel plot could be due to publication bias or could indicate genuine heterogeneity between small and large trials (Higgins 2019). It is important to assess the funnel axis in the funnel plot as a significant Egger's test could also indicate publication bias or be due to genuine small treatment effects. We did not visually inspect the funnel plot if fewer than 10 trials were included in the meta‐analysis, in accordance with the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019; Egger 1997; Sterne 2017).

Data synthesis

We performed the statistical analyses in accordance with the recommendations in the latest version of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019).

In carrying out meta‐analyses, we used the inverse‐variance method, to give more weight to more precise estimates from trials with less variance (mostly larger trials). This minimises the imprecision of the pooled effect estimate, and is a common and simple approach to conducting meta‐analyses (Higgins 2019). We used the random‐effects model for our meta‐analyses, since we expected some degree of clinical heterogeneity to be present in most cases, though not too substantial to prevent pooling in principle. Where only one trial was included in an analysis, we used the fixed‐effect model, and where different models led to different results (Sensitivity analysis), we reported the results of both models.

For trials with a high level of statistical heterogeneity, and where the amount of clinical heterogeneity made it inappropriate to use these trials in meta‐analyses, we provide a narrative description of the trial results. If data pooling seemed feasible, we pooled the primary trials' effects and calculated their 95% CIs.

If a trial reported data for a particular outcome using two or more assessment instruments (e.g. several questionnaires for the assessment of depression), we selected the one used most often in the whole pool of included trials for effect size calculation, in order to minimise heterogeneity of outcomes in form and content. If a trial reported data of two assessment instruments that were equally frequently used, two review authors discussed the issue and chose the one that was, in its content, the most appropriate for the assessment of people affected by BPD.

We divided the doses and the controls into the different comparisons, ensuring that the treatment comparisons were comparable and homogeneous.

We have two main overarching comparisons. In the first comparison, we pooled all of the different types of psychotherapy together and compared them with the different types of TAU pooled together. In the second comparison, we pooled all of the different types of psychotherapy and compared them with waiting list or no treatment. Within in each comparison, we broke down the interventions by therapeutic category compared with different types of TAU, waiting list, no treatment or with another psychotherapy (active control).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted the following prespecified subgroup analyses for two primary outcomes (BPD symptom severity and psychosocial functioning), where data were sufficient, in order to make hypotheses.

Therapeutic approaches: specific therapies versus each other (only analyses with two or more trials were included in this subgroup)

Age: mean age of 15 to 18 years versus older than 18 years

Duration: less than six months versus six to 12 months versus over 12 months

Mode of therapy: individual therapy versus group therapy and with the combination of individual and group therapy

Setting: inpatient versus outpatient and the combination of inpatient and outpatient

In addition, we added the following four subgroup analyses post hoc, for the primary outcomes of BPD symptom severity and psychosocial functioning.

Type of raters: self‐rated versus clinician‐rated

Types of TAU: obligatory TAU versus unspecified TAU

Type of comparison group: trials comparing psychotherapy plus TAU versus trials comparing psychotherapy with waiting list or no treatment

Types of scales: different measuring scales versus each other

Trial Sequential Analysis

Trial Sequential Analysis (TSA) is a methodology that combines a required information size (RIS) calculation for a meta‐analysis with the threshold for statistical significance (Brok 2008; Brok 2009; Thorlund 2009; Wetterslev 2008). TSA is a tool for quantifying the statistical reliability of the data in a cumulative meta‐analysis, adjusting P values for sparse data and for repetitive testing on accumulating data (Brok 2008; Brok 2009; Thorlund 2009; Wetterslev 2008).

Comparable to the a priori sample size estimation in a single randomised trial, a meta‐analysis should include an RIS calculation at least as large as the sample size of an adequately powered single trial to reduce the risk of random error. TSA calculates the RIS in a meta‐analysis and provides an alpha‐spending boundary to adjust the significance level for sparse data and repetitive testing on accumulating data (CTU 2011; Wetterslev 2008); hence, the risk of random error can be assessed. Multiple analyses of accumulating data when new trials emerge leads to repeated significant testing and introduces multiplicity. Thus, use of a conventional P value is prone to exacerbate the risk of random error (Berkey 1996; Lau 1995). Meta‐analyses not reaching the RIS are analysed with trial sequential alpha‐spending monitoring boundaries analogous to interim monitoring boundaries in a single trial (Wetterslev 2008). This approach will be crucial in coming updates of the review.

If a TSA does not reveal significant findings (no crossing of the alpha‐spending boundary and no crossing of the conventional boundary of P = 0.05) before the RIS has been reached, then the conclusion should either be that more trials are needed to reject or accept an intervention effect that was used for calculation of the required sample size or — in case the cumulated Z‐curve enters the futility area — the anticipated effect can be rejected.

We used a MIREDIF from studies defining this or, where we could not find this, we used an assumption that the minimal relevant clinical intervention effect was approximately ½ SD on the used scale, which can be used as a MIREDIF (Norman 2003).

We calculated the diversity‐adjusted required information size (DARIS; that is the number of participants required to detect or reject a specific intervention effect in a meta‐analysis), and performed a TSA for the primary outcomes at the end of treatment for the main comparison versus TAU, based on the following a priori assumptions:

the SD of the primary outcomes;

an anticipated MIREDIF defined in a trial reporting on this or we used a ½ SD on the used scale;

a maximum type I error of 2.0% (due to four primary outcomes; Jakobsen 2014);

a maximum type II error of 10% (minimum 90% power; Castellini 2018); and

the diversity observed in the meta‐analysis.

We furthermore performed a TSA for the three secondary outcomes (for the main comparison versus TAU) not closely connected to the BPD core symptoms (depression, attrition and adverse effects) based on the following priori assumptions:

the SD of the primary outcomes;

an anticipated MIREDIF defined in a trial reporting on this or we used a ½ SD on the used scale;

a maximum type I error of 0.8% (due to 11 secondary outcomes; Jakobsen 2014);

a maximum type II error of 10% (minimum 90% power; Castellini 2018); and

the diversity observed in the meta‐analysis.

We only performed a TSA for depression as this was the only significant finding.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses to determine whether findings were sensitive to:

imprecision, as assessed by GRADE, by conducting TSA analyses on all primary outcomes and for the three secondary outcomes (for the main comparison versus TAU) not closely connected to the BPD core symptoms (depression, attrition and adverse effects) with significant findings.

random‐effects or fixed‐effect models.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach to construct 'Summary of findings' tables in which to document the results of review outcomes. Two reviewers (HEC and JSW) , working independently, assessed the quality of the evidence. Any conflicts were resolved by consulting a third author (OJS). The GRADE approach appraises the quality of a body of evidence based on the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed. Considerations are due to: within‐trial risk of bias; directness of the evidence; heterogeneity of the data; precision of effect estimates; and risk of publication bias (Andrews 2013a; Andrews 2013b; Balshem 2011; Brunetti 2013; Guyatt 2011a; Guyatt 2011b; Guyatt 2011c; Guyatt 2011d; Guyatt 2011e; Guyatt 2011f; Guyatt 2011g; Guyatt 2013a; Guyatt 2013b; Guyatt 2013c; Mustafa 2013). When possible, we reported the MD or the RR, and we used TSA to rate imprecision (Jakobsen 2014). TSA can be used as a secondary analysis in Cochrane Reviews, to provide an additional interpretation of the data from a specific perspective, and can be used for testing imprecision (Thomas 2019).

We report the four primary outcomes (BPD severity, self‐harm, suicide‐related outcomes and psychosocial functioning) and three secondary outcomes not closely connected to the BPD core symptoms (depression, attrition and adverse effects) in 'Summary of findings' tables for our two main comparisons (Atkins 2004): psychotherapy versus treatment‐as‐usual (Table 1); and psychotherapy versus waiting list or no treatment (Table 2). We also created a third 'Summary of findings' table in which we report data from the DBT and MBT treatments with the highest numbers of primary trials, with DBT being the subject of roughly one‐third of all included trials, followed by MBT with seven RCTs. In this table, we report only the primary outcomes (see Table 3).

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, Characteristics of studies awaiting classification and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

All electronic databases and search periods are listed in the Methods section (see Electronic searches). There were no language, date or document format restrictions. This current review is part of a series of reviews on interventions for BPD. Therefore, we used a very comprehensive search strategy, covering all psychotherapeutic or pharmacological treatment (or both) of BPD.

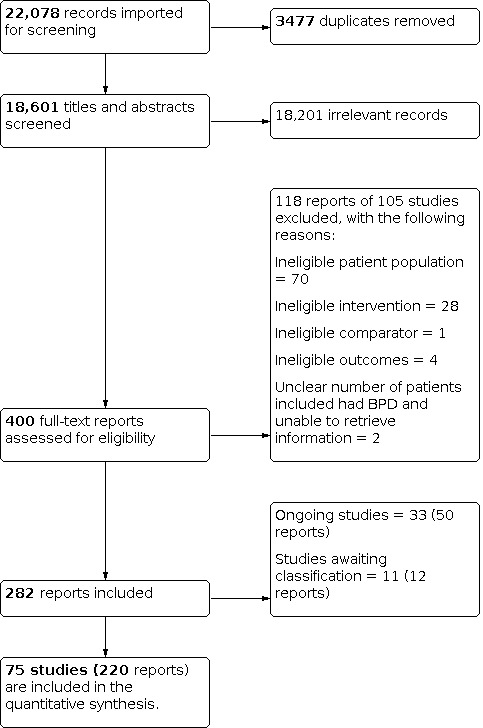

Altogether, the searches generated 22,078 records, of which 3477 were duplicates. Following screening of titles and abstracts, 400 citations merited closer inspection. An assessment of full texts for possible inclusion into this review led to the exclusion of 118 reports. This left 282 reports included. Of these, 50 reports referred to 33 different ongoing trials (see Ongoing studies). Another 12 reports related to 11 different trials that we were unable to classify definitively as included or excluded at this point of time, despite our best efforts to retrieve further information from the trial authors (see Studies awaiting classification). This finally left 220 reports relating to 75 different included trials (see Included studies, and Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies