Abstract

The rate constant for electron self-exchange (k11) between LCuOH and [LCuOH]− (L = bis-2,6-(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)carboximido-pyridine) was determined using the Marcus cross relation. This work involved measurement of the rate of the cross-reaction between [Bu4N][LCuOH] and [Fc][BAr4F] (Fc+ = ferrocenium; BAr4F = tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl]borate)) by stopped-flow methods at −88 °C in CH2Cl2 and measurement of the equilibrium constant for the redox process by UV–vis titrations under the same conditions. A value of k11 = 3 × 104 M−1 s−1 (−88 °C) led to estimation of a value 9 × 106 M−1 s−1 at 25 °C, which is among the highest values known for copper redox couples. Further Marcus analysis enabled determination of a low reorganization energy, λ = 0.95 ± 0.17 eV, attributed to minimal structural variation between the redox partners. In addition, the reaction entropy (ΔS°) associated with the LCuOH/[LCuOH]− self-exchange was determined from the temperature dependence of the redox potentials, and found to be dependent upon ionic strength. Comparisons to other Cu redox systems and potential new applications for the formally CuIII,II system are discussed.

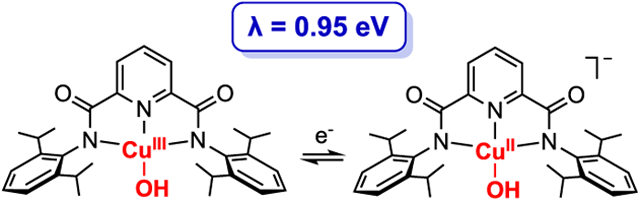

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

With the aim of evaluating proposals for intermediates involved in catalytic oxidations by enzymes,1 materials,2 and molecular systems,3,4 copper complexes at high formal oxidation states (>II) have been targeted for characterization and evaluation of their reactivity.5 Notable examples include complexes with [Cu2(μ-O)2)]2+,6 [Cu2(μ-OH)]n+ (n = 4 or 5),7 [CuO2]+,8 and [CuOH]2+9 cores postulated to contain formally Cu(III) ions; Cu(III) ions also have been stabilized by a variety of tetradentate anionic ligands10 and isolated with a metal–carbon bond.11 In recent work, we found that LCuOH (Figure 1) and derivatives rapidly attack C–H and O–H bonds, and through detailed kinetic, thermodynamic, and computational studies, we evaluated the mechanisms and key underlying reasons for their fast reactions.9 Typically, the complexes abstract H atoms in a concerted proton–electron transfer (CPET) process driven by the formation of a strong O–H bond in the product complex comprising the [Cu(OH2)]2+ core (bond dissociation enthalpy, BDE, ~ 90 kcal/mol for complex supported by L2−).9b,c This high BDE was determined through a square-scheme analysis (Figure 1) for LCuOH, with the low E1/2 for the CuIII,II couple (−0.074 V vs [Fc]+/Fc) being offset by the high pKa for [LCuOH]− (~19 in THF). Through application of an Evans–Polanyi (linear free energy) relationship, we proposed that the strength of the O–H bond in LCu(OH2) is a key contributor to the fast CPET reactions observed.9b,c

Figure 1.

(Top) Redox couple examined in this study, with formal oxidation states noted in the structures. (Bottom) Thermodynamic square scheme.

To explore other kinetic factors that may be at play, we have more closely examined the formally CuIII,II redox process by which LCuOH and [LCuOH]− interconvert. In particular, noting that the two complexes appear to have similar square planar geometries with structures that differ only with respect to the metal–ligand bond distances (average Cu–N/O bond shortens by 0.09 Å upon oxidation),9a we wondered if electron transfer (ET) self-exchange rates would be fast and the associated reorganization energy (λ) would be low. Kinetic studies of ET reactions involving CuIII,II couples are rare, the only examples of which we are aware being those of oligopeptide12 and imine–oxime complexes.13 Self-exchange rate constants k11 ~ 5 × 104 M−1 s−1 and ~5 × 105 M−1 s−1 at 25 °C, respectively, were measured for these complexes in H2O.12a,13 Reaction entropies for the reduction of CuIII to CuII were also determined for some oligopeptide complexes, using temperature-dependent cyclic voltammetry in H2O and CH3CN. These results were interpreted to indicate differences in solvent coordination between the two redox states (no binding to CuIII, axial binding to CuII).14 The paucity of data on CuIII,II systems contrasts with extensive information on CuII,I couples.15 Among the various factors that impact ET rates in such systems, geometry differences between the CuII and CuI states are particularly important. For example, ligand-induced distortions toward geometries intermediate between those favored for CuII (square planar) or CuI (tetrahedral) lowers λ and results in fast ET rates.15 Such effects have implications for understanding fast rates of ET in biological type 1 sites16 and for uses of copper complexes as redox mediators, such as in dye-sensitized solar cells.17–19

Herein, we describe the determination of k11, λ, and ΔS° for the LCuOH/[LCuOH]− couple (formally CuIII/II) that is central to the proton-coupled electron transfer chemistry related to the thermodynamic square scheme shown in Figure 1. Analysis of these results provides fundamental new insights into formal CuIII,II redox processes important in oxidation catalysis.

RESULTS

We aimed to use the Marcus relation eq 1 to determine λ. A key constraint is the inherent difficulties in isolating and handling LCuOH that made the use of NMR line broadening methods to directly determine k11 untenable. Instead, we targeted the rate- and equilibrium-constants (k12 and K12 respectively) for the cross reaction between [LCuOH]− and ferrocenium ([Fc]+), for use in the appropriately modified form of the Marcus cross-reaction expression to determine k11 (Scheme 1, eq 2).20

| (1) |

| (2) |

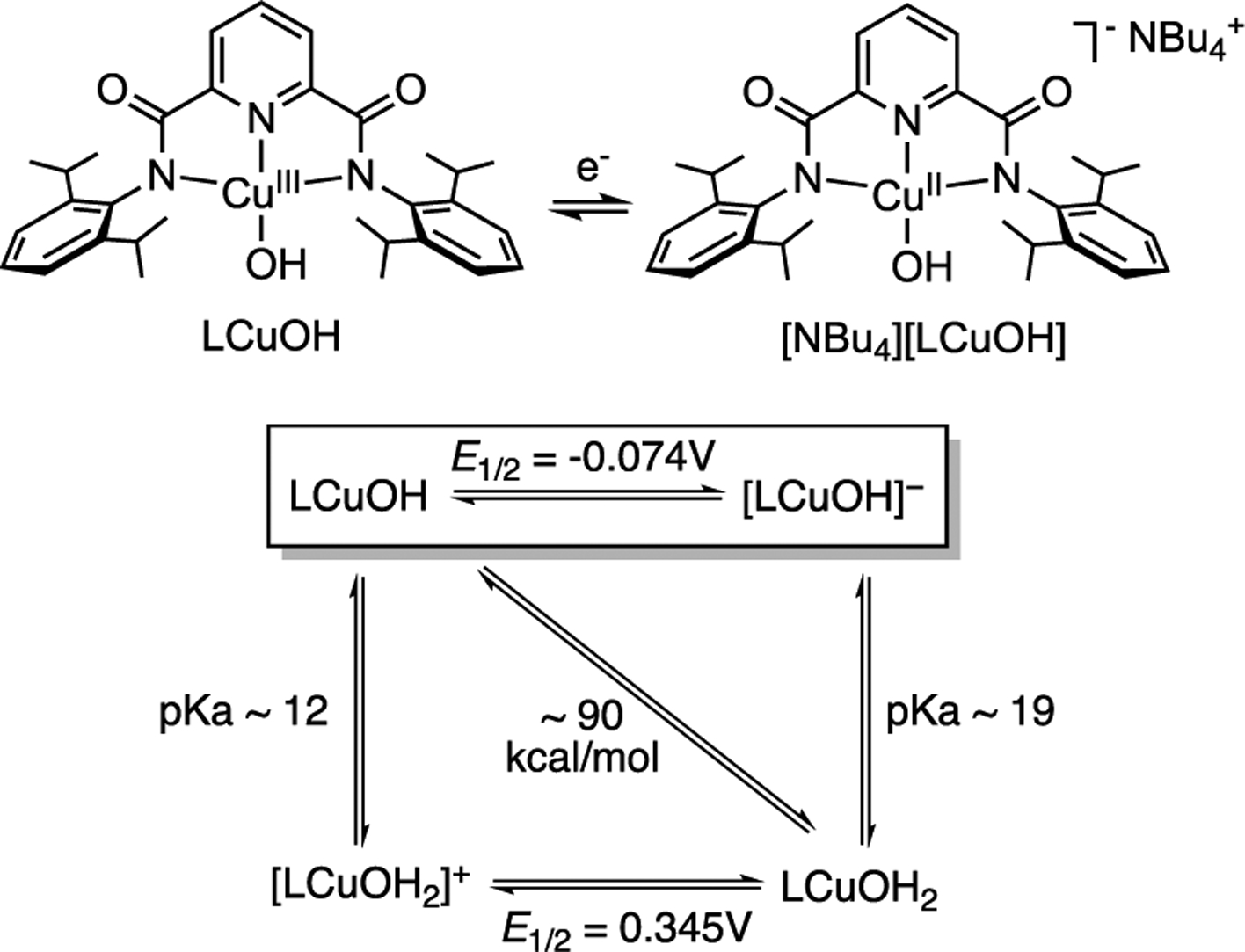

Scheme 1. ET Reactions and Associated Rate and Equilibrium Constants Considered in This Work.

To measure K12, we generated LCuOH by treatment of a solution of [Bu4N][LCuOH] (0.1 mM) at −88 °C with [Fc][BAr4F] (BAr4F = tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-borate). All of the experiments in this report were done in CH2Cl2; the optical experiments were all at −88 °C. Complete conversion was observed with a slight excess of oxidant (Figure S1). Comparison of the UV–vis spectra of LCuOH (ε560 nm = 11000 (±400) M−1 cm−1) to those of independent preparations using a stronger oxidant, [AcFc][BAr4F] confirmed the measured ε560 nm value (Figure S1). A back-titration was then performed by adding aliquots of a solution of ferrocene (50 μL, 4.0 mM stock solution, 1 equiv) to LCuOH generated from the reaction of [LCuOH]− with [Fc]+. From the absorbance changes at 560 nm, the concentrations of the compounds in the cross reaction were deduced and K12 was determined to be 400 ± 50 (see Supporting Information for details; Table 1).

Table 1.

Relevant Kinetic and Thermodynamic Parameters

| parametera | value |

|---|---|

| k12 | 6 (±2) × 107 M−1 s−1 |

| k22b | 5.6 × 105 M−1 s−1 |

| K12 | 400 (±50) |

| k11 | 3 (±8) × 104 M−1 s−1 |

| k11′ (25 °C)c | 9 × 106 M−1 s−1 |

| λ | 0.95 (±0.17) eV |

| λo | 0.50 eV |

| λi | 0.45 eV |

| S°(Cu) (I = 1.0 M [NBu4][PF6]) | −3.1 (±0.4) cal mol−1 K−1 |

| S°(Cu) (I = 0.2 M [NBu4][PF6]) | −23 (±0.5) cal mol−1 K−1 |

| S°(Fc*)d (I = 0.1 M [NBu4][PF6]) | 3.1 (±0.2) cal mol−1 K−1 |

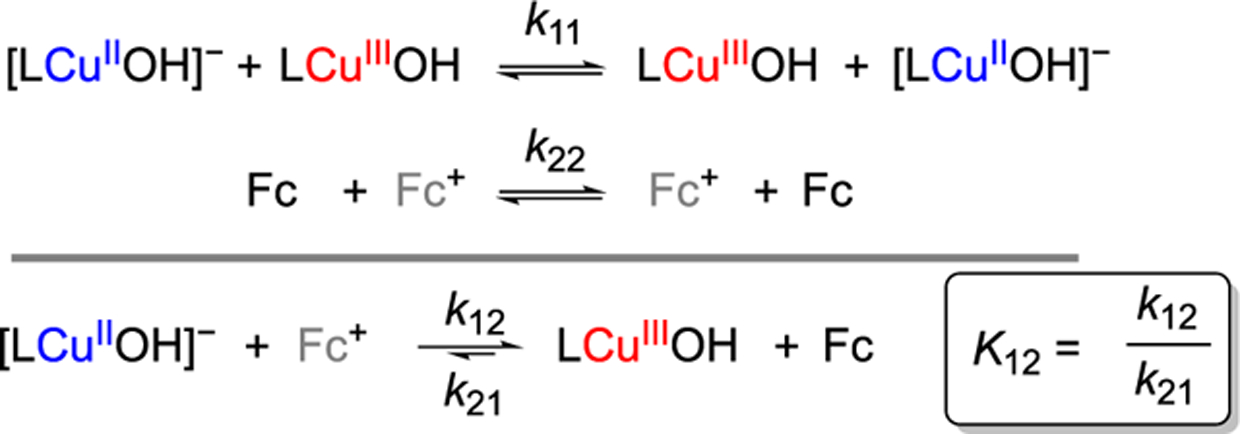

The cross-reaction rate constant k12 was measured by stopped-flow kinetics performed at −88 °C in CH2Cl2. The reaction was followed by UV–vis spectroscopy in the range 400–800 nm at 1.7 ms intervals. Mixing 0.1 mM solutions of [Bu4N][LCuOH] and [Fc][BAr4F] resulted in rapid conversion to LCuOH. Indeed, even under these dilute conditions the reaction was already >70% complete on the mixing time scale (~1–2 ms), complicating efforts to calculate an accurate rate constant. Nonetheless, global analysis of the data using ReactLab KINETICS23 provided a good fit to a simple, second order reaction mechanism (Figure 2), yielding k12 = 6 (±2) × 107 M−1 s−1 (average of four measurements).24

Figure 2.

(a) Stopped-flow spectra collected every 1.7 ms during the reaction of 0.1 mM [Bu4N][LCuOH] with 0.1 mM [Fc][BAr4F] in CH2Cl2 at −88.0 °C. Black curve is the spectrum of 0.1 mM [Bu4N][LCuOH]. (b) Experimental and modeled single wavelength profiles at 560 nm.

Use of eq 2 also required determination of the “work term” W12, which was estimated to be 23.3 ± 1.2 (unitless) from individual work terms associated with formation of the precursor/successor complexes of the cross- (w12 and w21) and self- (w11 and w22) exchange reactions (see Supporting Information, eqs S5–S7). The measured equilibrium constant K12 was used directly in eq 2 and the [Fc]+/Fc self-exchange rate constant (k22 at −88 °C) was taken as 5.6 × 105 M−1 s−1 (error analysis provided in Supporting Information).21 Together, the measured values of K12, k22, W12 and f12 (1.0; see Supporting Information) lead to a LCuOH/[LCuOH]− self-exchange rate constant (k11) of 3 (±8) × 104 M−1 s−1 at −88 °C in CH2Cl2. Substituting this value of k11 (which due to uncertainties in k12 is given to only one significant figure) into eq 1, using Z = 1011 M−1 s−1 and the relevant values of R and T, yields a reorganization energy λ of 0.95 (±0.17) eV for the LCuOH/[LCuOH]− electron exchange reaction. To facilitate comparisons to self-exchange rates reported for other systems (see Discussion), k11 = 9 × 106 M−1 s−1 at 25 °C was estimated using this λ in eq 1.

The measured reorganization energy (λ) is the sum of the outer-sphere and inner-sphere contributions, λo and λi, respectively (eq 3).20 The outer sphere reorganization energy can be estimated by eq 4, where Δe is the elementary charge transferred during the self-exchange reaction (1), a1 and a2 are the radii of LCuOH and [LCuOH]−, r is the center-to-center separation distance (a1 + a2), and Dstat and Dopt are the static- and optical-dielectric constants of CH2Cl2 (at −88 °C). Substituting the relevant values for each of these parameters into eq 4 leads to an approximate estimate λo = 0.50 eV (see Supporting Information), thus giving λi = 0.45 eV.

| (3) |

| (4) |

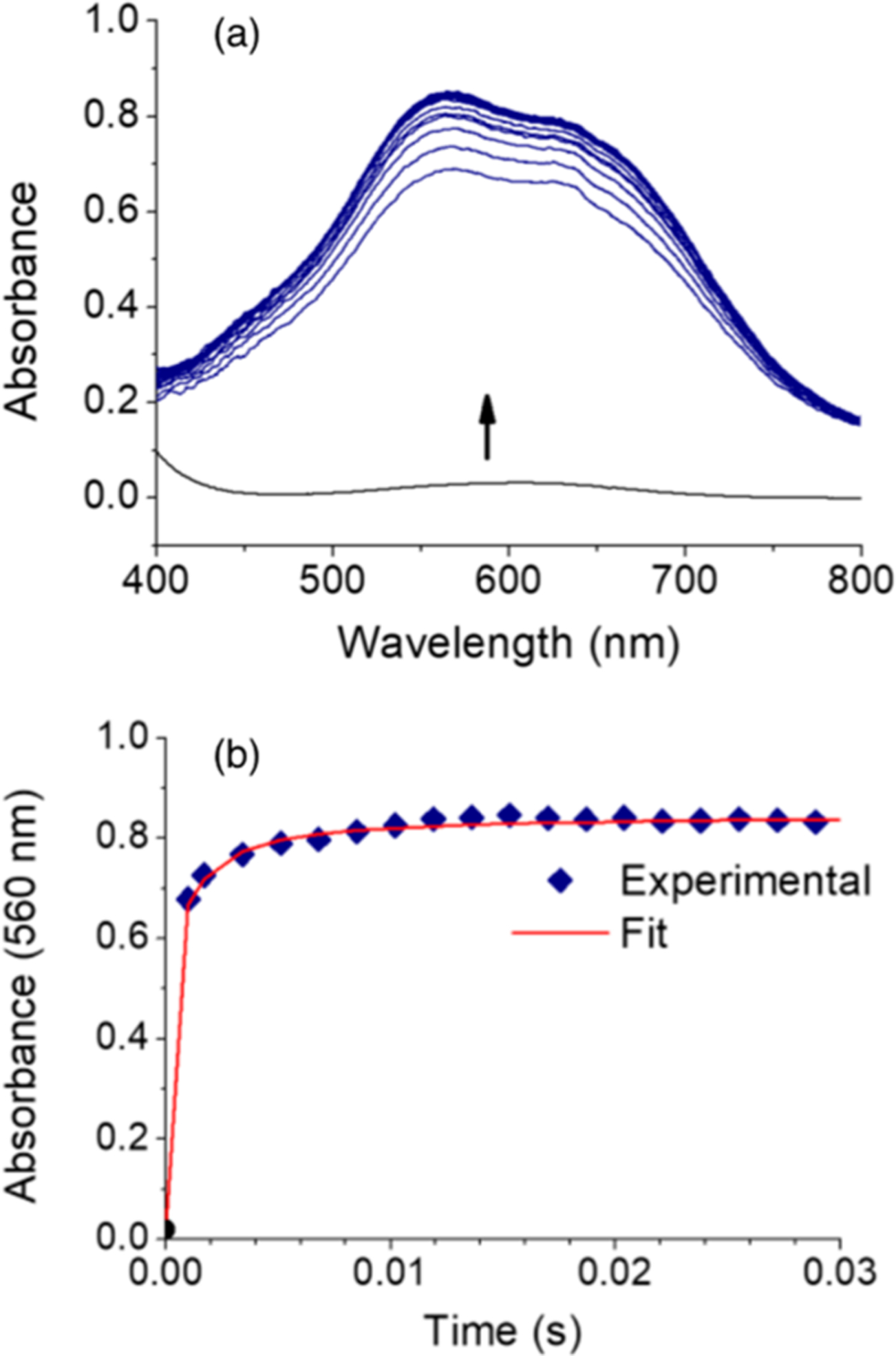

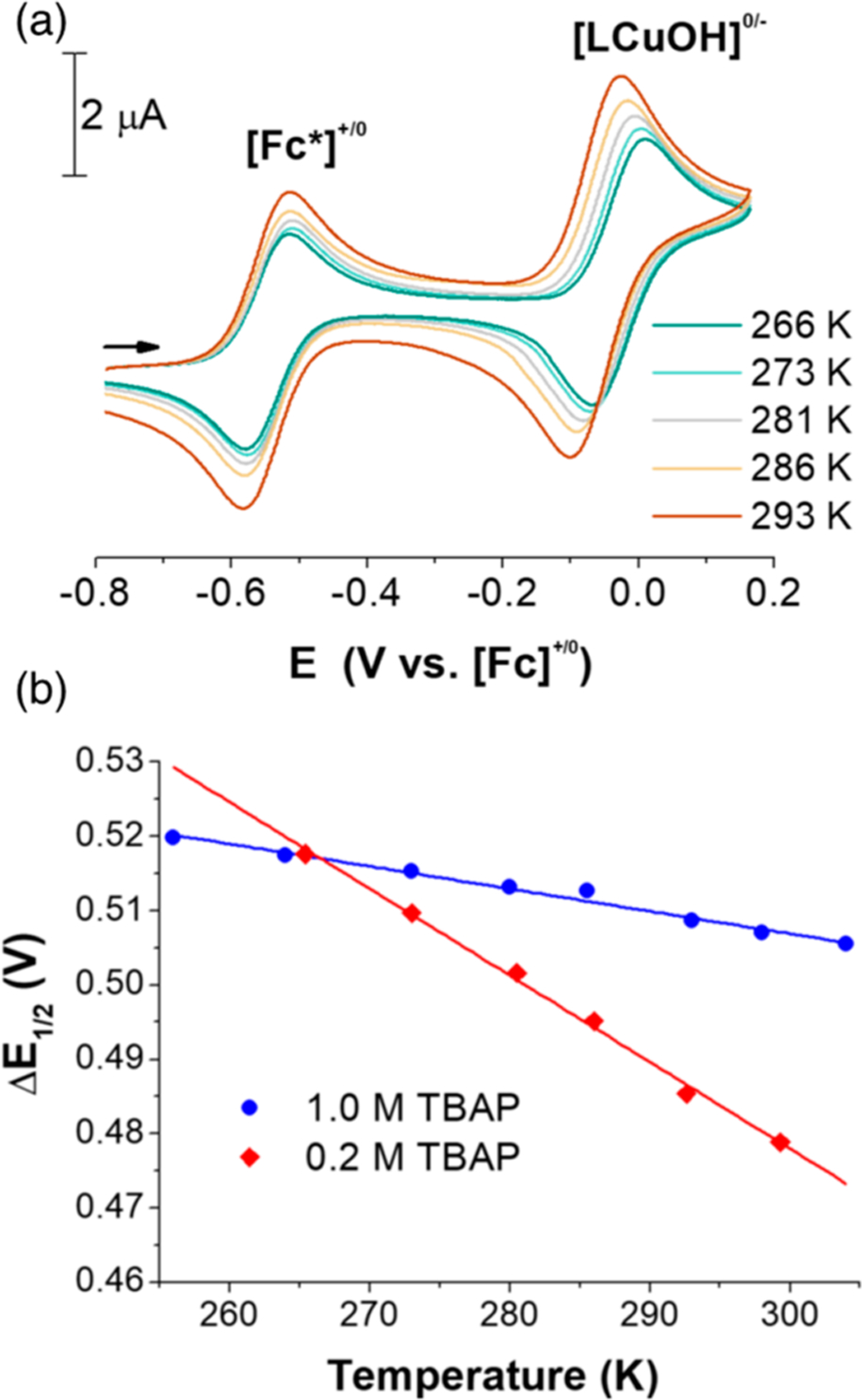

The reaction entropy (ΔS°) associated with the LCuOH/[LCuOH]− self-exchange was determined from the temperature dependence of the redox potentials of the [LCuOH]0/− couple (E°(Cu)) and an internal standard (E°(standard)) using an isothermal electrochemical cell (eq 5). The experimental procedure for these measurements has been described.25 Decamethylferrocene (Fc*) was selected as the internal reference (“standard”) because its redox potential is well resolved from the copper couple and ΔS°(Fc*) had been measured previously in CH2Cl2 (3.1 cal mol−1 K−1).22 The half-wave potential E1/2 determined by cyclic voltammetry in CH2Cl2 was used as an approximation for E° after this assumption was validated for both redox couples (see Supporting Information). The voltammetry is shown in Figure 3A with 0.2 M [Bu4N][PF6].

Figure 3.

(a) Temperature-dependent cyclic voltammograms of [Bu4N][LCuOH] (1.0 mM) + Fc* (0.5 mM) in CH2Cl2, at 1.0 M (blue) and 0.2 M (red) electrolyte (TBAP = [NBu4][PF6]). 0.2 M [Bu4N][PF6] as electrolyte; sweep rate = 50 mV s−1. (b) Plot of ΔE1/2 vs T, where ΔE1/2 = E1/2(Cu) − E1/2(Fc*).

As the temperature is raised, E1/2(Cu) undergoes a perceptible shift to more negative potentials while E1/2(Fc*) concomitantly undergoes a slight positive shift (Figure 3A). A plot of the differences between E1/2(Cu) and E1/2(Fc*), as a function of temperature, is shown in Figure 3B. Fitting this data to a linear function (eq 5) yields a line with a slope of 1.16 × 10−3 V K−1. From the known value of ΔS°(Fc*) (3.1 cal mol−1 K−1) and the slope, ΔS°(Cu) is calculated to be −23 (±0.5) cal mol−1 K−1. The opposite signs of ΔS°(Fc*) and ΔS°(Cu) relate to the differences in charge (vida infra). More striking are the different magnitudes of ΔS° which indicate that reduction of LCuOH is accompanied by more significant complex/solvent rearrangement. Suspecting that the larger magnitude of ΔS°(Cu) was due to ion-pairing effects, the voltammetry was remeasured with a higher (1.0 M) concentration of electrolyte (Figure S6). A much smaller temperature-dependent difference between E1/2(Cu) and E1/2(Fc*) was observed (slope = −2.7 × 10−4 V K−1) leading to ΔS°(Cu) = −3.1 ± 2 cal mol−1 K−1. The implications of this significant sensitivity of ΔS°Cu to ionic strength are discussed below.

| (5) |

DISCUSSION

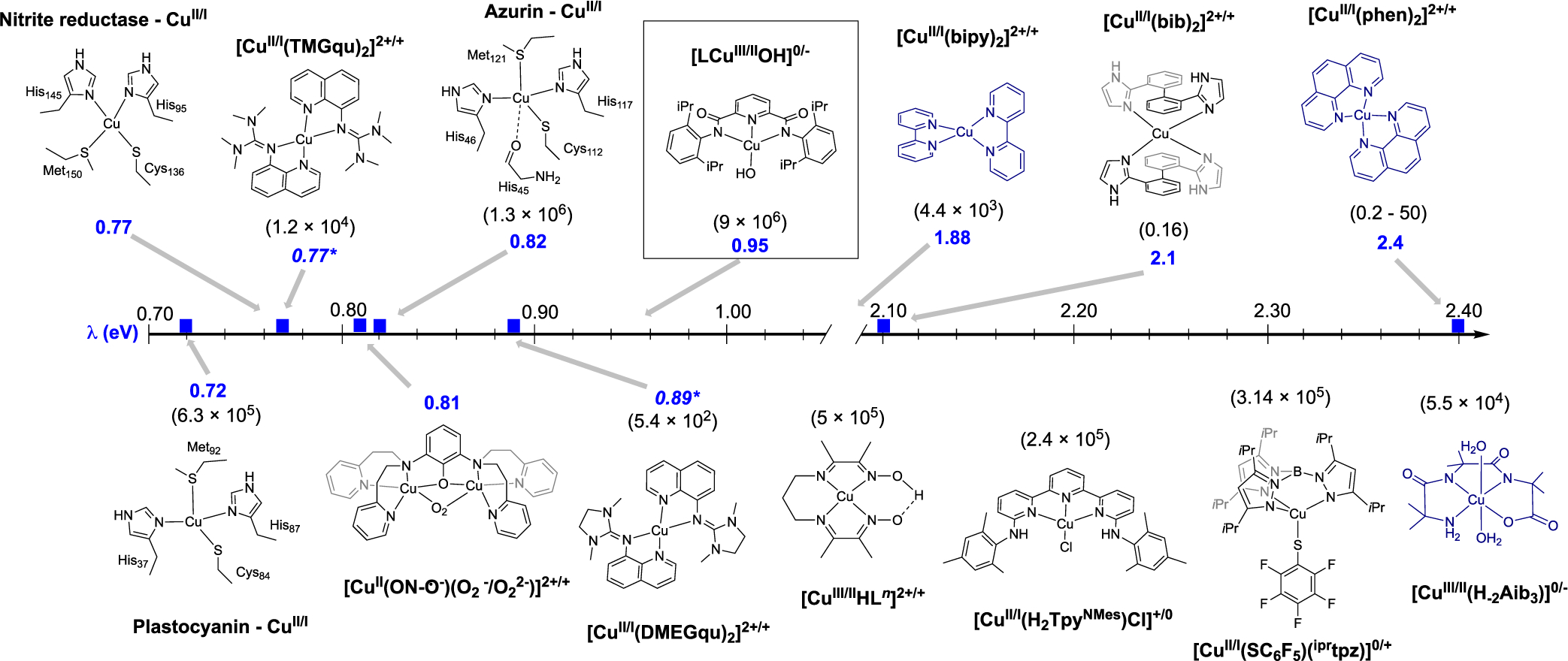

Since the results reported herein apparently represent the first determination of λ for a formally CuIII,II couple, comparisons to other copper systems are important to draw in order to put the findings into context. We compile a selection of such systems comprising CuII,I couples in Table 2 and Figure 4, which includes representative compounds and copper protein active sites that exhibit a range of λ values. Also shown are some examples of compounds for which self-exchange rate data are known but for which λ values are not, including data for the CuIII,II couples [CuIII,II(H−2Aib3)]0/− and [CuIII,IIHLn]2+/+; in the former and a few other cases, values of λ are estimated using eq 1 and are included in Table 2. Values of λ are estimated using eq 1 and are included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of Published Copper Self-Exchange Rate Constants (k11) and Reorganization Energies (λ) for Species Depicted in Figure 4

| λ (eV) | k11 (M−1 s−1) | conditions | reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| type I proteins | azurin (CuII,I) | 0.82 | 7.94 × 105 to 1.26 × 106 | H2O, 25 °C | 30–32 |

| plastocyanin (CuII,I) | 0.72 | 3.16 × 105 to 6.31 × 105 | H2O, 25 °C | 33, 34 | |

| nitrite reductase (CuII,I) | 0.77 | – | H2O, 25 °C | 41 | |

| “classical” copper(II,I) complexes | [CuII,I(phen)2]2+/+ | 2.4 | 50 | H2O, 22 °C | 26–28 |

| 0.2 | CH3CN, 25 °C | ||||

| [CuII,I(bipy)2]2+/+ | 1.88 | 4.4 × 103 | H2O, 25 °C | 27 | |

| [CuII,I(bib)2] | 2.8c | 0.16 | CH3CN, 25 °C | 53 | |

| constrained copper(II,I) complexes | [CuII,I(dmp)2]2+/+ | 2.28c | 23 | CH3CN, 25 °C | 54 |

| [CuII,I(SC6F5)(iprtpz)]0/+ | 1.58c | 1.76 × 104 | acetone-d6, −20 °C | 55 | |

| 3.14 × 105 | acetone-d6, 25 °C | ||||

| [CuII,I(H2TpyNMes)Cl]+/0 | 1.33c | 2.4 × 105 | THF, 25 °C | 46 | |

| [CuII,I(TMGqu)2]2+/+ | 0.77 | 1.2 × 104 | CH3CH2CN, 20 °C | 36, 37 | |

| 4.2 × 10−3 | CH2Cl2, −90 °C | ||||

| [CuII,I(DMEGqu)2]2+/+ | 0.89 | 5.4 × 102 | CH3CH2CN, 20 °C | 36 | |

| [CuII(UN-O−)(O2•−/O22−)]2+/+ | 0.81a | – | CH2Cl2, −80 °C | 42 | |

| copper(III,II) complexes | [LCuIII,II(OH)]0/− | 0.95 | 3 × 104 | CH2Cl2, −88 °C | this work |

| 9 × 106 | CH2Cl2, 25 °C | this work | |||

| [CuIII,IIHLn]2+/+ | b | 5 × 105 | H2O, 25 °C | 13 | |

| [CuIII,II(H−2Aib3)]0/− | 1.48c | 5.5 × 104 | H2O, 25 °C | 12 |

The reorganization energy of the [CuII(ON-O−)(O2•−/O22−)]2+/+ self-exchange was determined by calculating λo for the complex in CH2Cl2 at −80 °C (using eq 4 and the information in the Supporting Information of ref 42) and adding this value to the computed value of λin.

The reported k11 for this complex may have been derived incorrectly using parameters from PCET steps.13 Therefore, no λ was estimated for this complex.

Calculated from eq 1 using the measured k11.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of electron-transfer self-exchange properties of copper centers in proteins and model complexes (all experimentally determined, except those italicized with asterisks36,37). Reorganization energies (eV) are given in blue, and self-exchange rate constants (M−1 s−1, at 25 °C) are given in parentheses. Complexes in black are coordination number invariant during redox-cycling; complexes in navy change coordination number. Complexes are depicted in their reduced forms.

Large reorganization energies (>1.5 eV) accompany CuII,I self-exchange (ET) reactions with “classical” copper compounds bearing, for example, phenanthroline (phen) or bipyridine (bipy) ligands.15,26–28 Cuprous complexes bearing such N-donor ligands are characteristically 4-coordinate, while oxidation is typically accompanied by an increase in coordination number.29 The geometries are also significantly different, with Cu(I) adopting a tetrahedral or “seesaw” geometry while the preferred geometry of copper(II) is either trigonal bipyramidal or square pyramidal. These changes in coordination number and geometry which accompany electron transfer work synergistically to yield large reorganization energies and sluggish rates of electron transfer, typically characterized by rate constants of 100–102 M−1 s−1.15

The electron self-exchange rate constant we measured for the LCuOH/[LCuOH]− couple is much larger: k11 = 3 × 104 M−1 s−1 at −88 °C and estimated to be ~ 9 × 106 M−1 s−1 at 25 °C. This latter value is similar to that reported for type 1 Cu proteins (105 – 106 M−1 s−1).16b,30–34 Also, the value we measured at −88 °C is 7 orders of magnitude larger than that measured at −90 °C in CH2Cl2 for [CuII(TMGqu)2]2+/[CuI (TMGqu)2]+ self-exchange (10−3 M−1 s−1) (Figure 4),35 which has been touted as a definitive example of a complex held in an entatic state (in a geometry poised between the extremes typical for CuI and CuII species and thus expected to undergo fast ET reactions).36–40 Finally, the estimated k11 value for LCuOH/[LCuOH]− ET at 25 °C (in CH2Cl2) is ~10 or 100 times larger than those for the known CuIII,II couples supported by imine–oxime or tetramide (H−2Aib3) ligands (in H2O), respectively (Figure 4).12,13 In separate work, it was shown for the latter system that the CuIII congener is strictly four-coordinate but the CuII complex is axially coordinated by one or two solvent water molecules.14 Thus, slower electron exchange may be rationalized by coupling of ET with a chemical reaction (ligand coordination/decoordination). On the basis of the much faster rates of electron transfer observed in our study, we postulate that ligand exchange does not accompany LCuOH/[LCuOH]− ET in CH2Cl2; this postulate is further substantiated by the electrochemistry data (vide infra).

Consistent with the fast electron self-exchange kinetics, a low λ value of 0.95 eV was determined for the LCuOH/[LCuOH]− couple that is only slightly larger than those reported for type 1 Cu proteins30–34,41 and calculated for the Cu/(TMGqu)2 and Cu/(DMEGqu)2 complexes.36–40 The inner sphere reorganization energy derived from our measurements for the LCuOH/[LCuOH]− system is very small (0.45 eV), indicating that almost half of the total energetic cost is due to reorganization of the solvent in the outer coordination sphere (λo = 0.50 eV). By comparison, λo values of 0.5–0.6 eV have been reported for redox couples of other systems measured in DMF or CH2Cl2.42,43 The low λi is consistent with minimal structural change upon electron self-exchange, as indicated by a small difference in the Cu–N and Cu–X bonds (by ~0.1 Å), but no other significant reorganization of the coordination sphere for LCuX/[LCuX]− pairs (X = OH or Cl).9a,44 Interestingly, the λi we measured is comparable to that measured for electron exchange involving superoxide/peroxide ligands in the [CuII(ON–O−)(O2•−)/(O22−)]2+/+ complexes (λi = 0.4 eV).42 The superoxide/peroxide exchange is ligand-rather than metal-centered and is accompanied by a small change in the solid-state structures. Indeed, all the examples reported to have λ < 1 eV appear to have such structural similarities between their redox states (small differences in metal–ligand bond distances and angles).

A related copper system supported by a mesitylene-substituted terpyridine ligand, “H2TpyNMes” is also a valuable comparator. When prepared with chloride as the auxiliary ligand, the resulting CuII and CuI complexes are both square planar (Figure 4) and fast CuII,I self-exchange kinetics were observed (k11 = 2.4 × 105 M−1 s−1).45 This system provides a particularly interesting comparison to LCuOH/[LCuOH]− because the charges and reduction potentials are very different, yet the structural similarities are striking and, in both cases, redox exchange involves a persistent square-planar geometry that correlates with fast kinetics. Lastly, we note that the low λ is a bit surprising in light of the importance of ion pairing in this system (vide infra). As noted by Savéant,46 the occurrence of ion pairing can add an additional free energy term to the intrinsic barrier, or can add mechanistic complexity. Both effects should slow the reactions, so the very rapid reaction reported here is particularly remarkable.

We next compare ΔS° associated with reduction for the [CuIII,II(H−2Aib3)]0/− and [LCuOH]0/− systems. For the former, ΔS° was reported to be −17.0 and −13.1 cal mol−1 K−1 in 1.0 and 0.1 M aqueous solutions of [Na][ClO4], respectively.14 For the latter, we found ΔS° to be −3.1 and −19 cal mol−1 K−1 in CH2Cl2 with 1.0 and 0.2 M concentrations of [Bu4N][PF6], respectively. Thermodynamic relationships that underpin solvent- and complex-dependent reaction entropies are sophisticated and often involve a range of parameters, thus complicating comparison of specific values between systems.47,48 Nonetheless, we can attribute the differences in the dependencies of the ΔS° values on ionic strength for the two systems to ion pairing effects. In water, ion-pairing between [Cu(H−2Aib3)]− and the electrolyte counterion is minimal because of the high polarity of the solvent.49 Thus, a 10-fold increase in ionic strength does not appreciably alter the effective dielectric constant (εeff) of the medium. Since ΔS° is inversely proportional to εeff (albeit with exceptions),49 this small change in εeff results in a minimal dependence of ΔS° on ionic strength for the [CuIII,II(H−2Aib3)]0/− system. In contrast, ion pairing is significant in CH2Cl2.50, 51 Reduction of LCuOH is therefore expected to be accompanied by formation of the [LCuOH]-[Bu4N] ion pair complex, and at higher electrolyte concentrations the [Bu4N]+ cation is more readily available and less outer-sphere reorganization is required en route to formation of the ion pair. A 5-fold increase in the concentration of [Bu4N][PF6] also significantly increases εeff because of the lower polarity of the CH2Cl2 solvent.50 The net result is a significant dependence of ΔS° on the electrolyte concentration for the [LCuOH]0/− system.

The low value of ΔS° for [LCuOH]0/− (−3.1 cal mol−1 K−1), which is similar to ΔS° for [Fc*]+/0 (3.1 cal mol K−1), is strong evidence that solvent is not coordinated to the copper complex in either oxidation state. One of the reasons decamethylferrocene is considered the “gold standard” internal reference for electrochemistry is because its redox potential is essentially constant in a variety of solvents.22 This behavior is attributed to small structural differences between [Fc*]+ and Fc*, and weak solute–solvent interactions. These characteristics are correlated with small values of ΔS°, especially in nonpolar, or slightly polar solvents like CH2Cl2. The similar magnitudes of ΔS° for the [Fc*]+/0 and [LCuOH]0/− half reactions therefore indicate that in both cases electron transfer is accompanied by minimal reorganization within the inner- and outer-coordination spheres (i.e., solvent is not exchanged). The opposite signs of ΔS° for the two reactions clearly relate to the differences in charge; LCuOH reduction leads to the acquisition of a negative charge and minor organization of the solvent around the charged ion (a small loss of entropy), while [Fc*]+ reduction leads to charge neutralization and dissipation of the preorganized solvent cage (a small gain in entropy).

CONCLUSIONS

We analyzed low temperature stopped-flow kinetics, electro-chemical, and UV–vis spectroscopic data using the Marcus relations to determine key parameters for electron self-exchange between the complexes LCuOH and [LCuOH]− (Table 1). Key findings were a fast ET rate, low reorganization energy, and a ΔS° associated with reduction of LCuOH that is sensitive to ionic strength but is small at high concentrations of electrolyte. Comparisons to the few other CuIII,II systems and the more extensive data for CuII,I couples, including biological type 1 copper sites (Table 2, Figure 4), highlights the LCuOH/[LCuOH]− system as having among the fastest ET rates and lowest λ values. These results, in particular the low λi of 0.45 eV, are consistent with minimal structural differences between the complexes. By analogy, we propose that a low ET reorganization energy at least partially underlies the previously reported fast rates of PCET by LCuOH. While PCET intrinsic barriers do not always correlate with ET ones in the same system, the inner-sphere rearrangements are often similar.52 For example, large changes in V–O distances in a vanadiumdioxo system gave a large PCET intrinsic barrier.53d Thus, the rigidity of the LCuOH system should facilitate PCET as well as ET. These factors might also be important in catalysis by Cu(III) centers proposed as intermediates in oxidase and oxygenase enzymes.1,5

Finally, we note that the low reorganization energy for the LCuOH/[LCuOH]− system has potential implications for adoption of these or similar species as redox mediators. Notably, the similarities between the properties of CuII,I complexes used as highly efficient redox mediators and hole transport materials in dye sensitized solar cells (DSCs) with those of LCuX/[LCuX]− systems we have described herein suggests that explorations of the latter for potential DSC applications might be worthwhile.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the NIH (Grant R01GM47365 to W.B.T., Grant 1F32GM099316 for a postdoctoral fellowship to C.T.S., and Grant 2R01GM50422 to J.M.M.) for support of this research.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b02185.

Experimental details, data, and plots (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Solomon EI; Heppner DE; Johnston EM; Ginsbach JW; Cirera J; Qayyum M; Kieber-Emmons MT; Kjaergaard CH; Hadt RG; Tian L Copper Active Sites in Biology. Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 3659–3853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ciano L; Davies GJ; Tolman WB; Walton PH Bracing copper for the catalytic oxidation of C–H bonds. Nature Catal. 2018, 1, 571–577. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Snyder BER; Bols ML; Schoonheydt RA; Sels BF; Solomon EI Iron and Copper Active Sites in Zeolites and Their Correlation to Metalloenzymes. Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 2718–2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Wendlandt AE; Suess AM; Stahl SS Coper-Catalyzed Aerobic Oxidative C-H Functionalizations: Trends and Mechanistic Insights. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2011, 50, 11062–11087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ryland BL; Stahl SS Practical Aerobic Oxidations of Alcohols and Amines with Homogeneous Copper/TEMPO and Related Catalyst Systems. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2014, 53, 8824–8838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Garcia-Bosch I; Siegler MA Copper-Catalyzed Oxidation of Alkanes with H2O2 under a Fenton-like Regime. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 12873–12876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Trammell R; See YY; Herrmann AT; Xie N; Diaz DE; Siegler MA; Baran PS; Garcia-Bosch I Decoding the Mechanism of Intramolecular Cu-Directed Hydroxylation of sp3 C-H Bonds. J. Org. Chem 2017, 82, 7887–7904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Mirica LM; Ottenwaelder X; Stack TDP Structure and Spectroscopy of Copper-Dioxygen Complexes. Chem. Rev 2004, 104, 1013–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lewis EA; Tolman WB Reactivity of Copper-Dioxygen Systems. Chem. Rev 2004, 104, 1047–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Elwell CE; Gagnon NL; Neisen BD; Dhar D; Spaeth AD; Yee GM; Tolman WB Copper–Oxygen Complexes Revisited: Structures, Spectroscopy, and Reactivity. Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 2059–2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lee JY; Karlin KD Elaboration of copper-oxygen mediated C-H activation chemistry in consideration of future fuel and feedstock generation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2015, 25, 184–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Quist DA; Diaz DE; Liu JJ; Karlin KD Activation of dioxygen by copper metalloproteins and insights from model complexes. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2017, 22, 253–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Keown W; Gary JB; Stack TD High-valent copper in biomimetic and biological oxidations. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2017, 22, 289–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Que L Jr.; Tolman WB Bis(μ-oxo)dimetal “diamond” cores in copper and iron complexes relevant to biocatalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2002, 41, 1114–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tolman WB Making and breaking the Dioxygen O-O Bond: New Insights from Studies of Syntheic Copper Complexes. Acc. Chem. Res 1997, 30, 227–237. [Google Scholar]; (c) Citek C; Herres-Pawlis S; Stack TDP Low Temperature Syntheses and Reactivity of Cu2O2 Active-Site Models. Acc. Chem. Res 2015, 48, 2424–2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Halvagar MR; Solntsev PV; Lim H; Hedman B; Hodgson KO; Solomon EI; Cramer CJ; Tolman WB Hydroxo-Bridged Dicopper(II,III) and -(III,III) Complexes: Models for Putative Intermediates in Oxidation Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 7269–7272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Cramer CJ; Tolman WB Mononuclear Cu-O2 Complexes: Geometries, Spectroscopic Properties, Electronic Structures, and Reactivity. Acc. Chem. Res 2007, 40, 601–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a) Donoghue PJ; Tehranchi J; Cramer CJ; Sarangi R; Solomon EI; Tolman WB Rapid C–H Bond Activation by a Monocopper(III)–Hydroxide Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 17602–17605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dhar D; Tolman WB Hydrogen Atom Abstraction from Hydrocarbons by a Copper(III)-Hydroxide Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 1322–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dhar D; Yee GM; Spaeth AD; Boyce DW; Zhang H; Dereli B; Cramer CJ; Tolman WB Perturbing the Copper(III)–Hydroxide Unit through Ligand Structural Variation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 356–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Dhar D; Yee GM; Markle TF; Mayer JM; Tolman WB Reactivity of the copper(III)-hydroxide unit with phenols. Chem. Sci 2017, 8, 1075–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Spaeth AD; Gagnon NL; Dhar D; Yee GM; Tolman WB Determination of the Cu(III)-OH Bond Distance by Resonance Raman Spectroscopy Using a Normalized Version of Badger’s Rule. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 4477–4485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Dhar D; Yee GM; Tolman WB Effects of Charged Ligand Substituents on the Properties of the Formally Copper(III)-Hydroxide ([CuOH]2+) Unit. Inorg. Chem 2018, 57, 9794–9806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).(a) Akbar Ali M; Bernhardt PV; Brax MAH; England J; Farlow AJ; Hanson GR; Yeng LL; Mirza AH; Wieghardt K The Trivalent Copper Complex of a Conjugated Bis-dithiocarbazate Schiff Base: Stabilization of Cu in Three Different Oxidation States. Inorg. Chem 2013, 52, 1650–1657. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Anson FC; Collins TJ; Richmond TG; Santarsiero BD; Toth JE; Treco BGRT Highly stabilized copper(III) complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1987, 109, 2974–2979. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Maurya YK; Noda K; Yamasumi K; Mori S; Uchiyama T; Kamitani K; Hirai T; Ninomiya K; Nishibori M; Hori Y; Shiota Y; Yoshizawa K; Ishida M; Furuta H Ground-State Copper(III) Stabilized by N-Confused/N-Linked Corroles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Redox Reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 6883–6892. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Koval CA; Margerum DW Determination of the self-exchange electron-transfer rate constant for a copper(III,II) tripeptide complex by proton NMR line broadening. Inorg. Chem 1981, 20, 2311–2318. [Google Scholar]; (b) Koval CA; Pravata RLA; Reidsema CM Steric effects in electron-transfer reactions. 1. Trends in homogeneous rate constants for reactions between members of structurally related redox series. Inorg. Chem 1984, 23, 545–553. [Google Scholar]; (c) Anast JM; Hamburg AW; Margerum DW Electron-transfer reactions of copper(III)-peptide complexes with ruthenium(II) ammine and copper(II)-peptide complexes. Inorg. Chem 1983, 22, 2139–2145. [Google Scholar]; (d) Owens GD; Phillips DA; Czarnecki JJ; Raycheba JMT; Margerum DW Electron-transfer kinetics of the reactions between copper(III,II) and nickel(III,II) deprotonated-peptide complexes. Inorg. Chem 1984, 23, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar]; (e) Anast JM; Margerum DW Electron-transfer reactions of copper(III)-peptide complexes with hexacyanoferrate(II). Inorg. Chem 1982, 21, 3494–3501. [Google Scholar]; (f) Owens GD; Margerum DW Rapid electron-transfer reactions between hexachloroiridate(IV) and copper(II) peptides. Inorg. Chem 1981, 20, 1446–1453. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Hussein A; Sulfab Y; Nasreldin M Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer between [Ni(cyclam)]2+ and Copper(III) Imine-Oxime Complexes. Inorg. Chem 1989, 28, 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Youngblood MP; Margerum DW Reaction entropies of copper(III,II) peptide and nickel(III,II) peptide redox couples and the role of axial solvent coordination. Inorg. Chem 1980, 19, 3068–3072. [Google Scholar]

- (15).(a) Rorabacher DB Electron Transfer by Copper Centers. Chem. Rev 2004, 104, 651–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Comba P Coordination compounds in the entatic state. Coord. Chem. Rev 2000, 200–202, 217–245. [Google Scholar]

- (16).(a) Solomon EI; Szilagyi RK; DeBeer George S; Basumallick L Electronic Structures of Metal Sites in Proteins and Models: Contributions to Function in Blue Copper Proteins. Chem. Rev 2004, 104, 419–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dennison C Investigating the structure and function of cupredoxins. Coord. Chem. Rev 2005, 249, 3025–3054. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Hattori S; Wada Y; Yanagida S; Fukuzumi S Blue Copper Model Complexes with Distorted Tetragonal Geometry Acting as Effective Electron-Transfer Mediators in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 9648–9654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Cao Y; Saygili Y; Ummadisingu A; Teuscher J; Luo J; Pellet N; Giordano F; Zakeeruddin SM; Moser JE; Freitag M; Hagfeldt A; Grätzel M 11% efficiency solid-state dye-sensitized solar cells with copper(II,I) hole transport materials. Nat. Commun 2017, 8, 15390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Saygili Y; Söderberg M; Pellet N; Giordano F; Cao Y; Muñoz-García AB; Zakeeruddin SM; Vlachopoulos N; Pavone M; Boschloo G; Kavan L; Moser J-E; Grätzel M; Hagfeldt A; Freitag M Copper Bipyridyl Redox Mediators for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells with High Photovoltage. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 15087–15096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Marcus RA; Sutin N Electron transfers in chemistry and biology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Rev. Bioenerg 1985, 811, 265–322. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Nielson RM; McManis GE; Golovin MN; Weaver MJ Solvent dynamical effects in electron transfer: comparisons of self-exchange kinetics for cobaltocenium-cobaltocene and related redox couples with theoretical predictions. J. Phys. Chem 1988, 92, 3441–3450. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Noviandri I; Brown KN; Fleming DS; Gulyas PT; Lay PA; Masters AF; Phillips L The Decamethylferrocenium/Decamethylferrocene Redox Couple: A Superior Redox Standard to the Ferrocenium/Ferrocene Redox Couple for Studying Solvent Effects on the Thermodynamics of Electron Transfer. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103 (32), 6713–6722. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Maeder M; King P Reactlab; Jplus Consulting Pty Ltd: East Freemantle, WA. Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- (24). We attempted to increase the accuracy and precision for the value of k12 by varying the ratios of reagents to access pseudo first order conditions (10:1, 1:5, and 1:2 ratios of Cu complex to Fc+ at both [Cu]0 = 0.1 mM and 0.01 mM). The reactions were too fast to obtain more accurate fits at the higher Cu complex concentration, and the signal-to-noise was insufficient at the lower Cu concentration. We note that inaccuracies in k12 translate to relatively small disparities in the final calculated value of the reorganization energy, λ. These and related issues are discussed further in the error analysis provided in the Supporting Information.

- (25).Koval CA; Gustafson RM; Reidsema CM Use of internal standards for the measurement of reaction entropies. Inorg. Chem 1987, 26, 950–952. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Winkler JR; Wittung-Stafshede P; Leckner J; Malmström BG; Gray HB Effects of folding on metalloprotein active sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1997, 94, 4246–4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Lee CW; Anson FC Recalculation of the rate of electron exchange between copper(II) and copper(I) in their 1,10-phenanthro-line and 2,2′-bipyridine complexes in aqueous media. J. Phys. Chem 1983, 87, 3360–3362. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Augustin MA; Yandell JK Rates of electron-transfer reactions of some copper(II)-phenanthroline complexes with cytochrome c(II) and tris(phenanthroline)cobalt(II) ion. Inorg. Chem 1979, 18, 577–583. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Zerk TJ; Bernhardt PV Redox-coupled structural changes in copper chemistry: Implications for atom transfer catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev 2018, 375, 173–190. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Di Bilio AJ; Hill MG; Bonander N; Karlsson BG; Villahermosa RM; Malmström BG; Winkler JR; Gray HB Reorganization Energy of Blue Copper: Effects of Temperature and Driving Force on the Rates of Electron Transfer in Ruthenium- and Osmium-Modified Azurins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119, 9921–9922. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Groeneveld CM; Dahlin S; Reinhammar B; Canters GW Determination of the electron self-exchange rate of azurin from Pseudomonas aeruginosa by a combination of fast-flow/rapid-freeze experiments and EPR. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1987, 109, 3247–3250. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Groeneveld CM; Canters GW NMR study of structure and electron transfer mechanism of Pseudomonas aeruginosa azurin. J. Biol. Chem 1988, 263, 167–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Di Bilio AJ; Dennison C; Gray HB; Ramirez BE; Sykes AG; Winkler JR Electron Transfer in Ruthenium-Modified Plastocyanin. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 7551–7556. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Dennison C; Kyritsis P; McFarlane W; Sykes AG Determination of the self-exchange rate constant for plastocyanin from Anabaena variabilis by nuclear magnetic resonance line broadening. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans 1993, 1959–1963. [Google Scholar]

- (35). We note that using the reorganization energies computed in ref 33, self-exchange rates constants much larger than the experimental value are predicted for the Cu/(TMGqu)2 and Cu/(DMEGqu)2 complexes.

- (36).Stanek J; Konrad M; Mannsperger J; Hoffmann A; Herres-Pawlis S Influence of Functionalized Substituents on the Electron-Transfer Abilities of Copper Guanidinoquinoline Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2018, 2018, 4997–5006. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Stanek J; Sackers N; Fink F; Paul M; Peters L; Grunzke R; Hoffmann A; Herres-Pawlis S Copper Guanidinoquinoline Complexes as Entatic State Models of Electron-Transfer Proteins. Chem. - Eur. J 2017, 23, 15738–15745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Hoffmann A; Binder S; Jesser A; Haase R; Flörke U; Gnida M; Salomone Stagni M; Meyer-Klaucke W; Lebsanft B; Grünig LE; Schneider S; Hashemi M; Goos A; Wetzel A; Rübhausen M; Herres-Pawlis S Catching an Entatic State—A Pair of Copper Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2014, 53, 299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Hoffmann A; Stanek J; Dicke B; Peters L; Grimm-Lebsanft B; Wetzel A; Jesser A; Bauer M; Gnida M; Meyer-Klaucke W; Rübhausen M; Herres-Pawlis S Implications of Guanidine Substitution on Copper Complexes as Entatic-State Models. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2016, 2016, 4731–4743. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Dicke B; Hoffmann A; Stanek J; Rampp MS; Grimm-Lebsanft B; Biebl F; Rukser D; Maerz B; Göries D; Naumova M; Biednov M; Neuber G; Wetzel A; Hofmann SM; Roedig P; Meents A; Bielecki J; Andreasson J; Beyerlein KR; Chapman HN; Bressler C; Zinth W; Rübhausen M; Herres-Pawlis S Transferring the entatic-state principle to copper photochemistry. Nat. Chem 2018, 10, 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Farver O; Eady RR; Pecht I Reorganization Energies of the Individual Copper Centers in Dissimilatory Nitrite Reductases: Modulation and Control of Internal Electron Transfer. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 9005–9007. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Cao R; Saracini C; Ginsbach JW; Kieber-Emmons MT; Siegler MA; Solomon EI; Fukuzumi S; Karlin KD Peroxo and Superoxo Moieties Bound to Copper Ion: Electron-Transfer Equilibrium with a Small Reorganization Energy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 7055–7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Anderson BL; Maher AG; Nava M; Lopez N; Cummins CC; Nocera DG Ultrafast Photoinduced Electron Transfer from Peroxide Dianion. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 7422–7429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Dhar D; Yee GM; Spaeth AD; Boyce DW; Zhang H; Dereli B; Cramer CJ; Tolman WB Perturbing the Copper(III)–Hydroxide Unit through Ligand Structural Variation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 356–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Dahl EW; Szymczak NK Hydrogen Bonds Dictate the Coordination Geometry of Copper: Characterization of a Square-Planar Copper(I) Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 3101–3105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Savéant J-M Evidence for Concerted Pathways in Ion-Pairing Coupled Electron Transfers. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 4732–4741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Sutin N; Weaver MJ; Yee EL Correlations between outer-sphere self-exchange rates and reaction entropies for some simple redox couples. Inorg. Chem 1980, 19, 1096–1098. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Hupp JT; Weaver MJ Solvent, ligand, and ionic charge effects on reaction entropies for simple transition-metal redox couples. Inorg. Chem 1984, 23, 3639–3644. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Reichardt C Solvatochromic Dyes as Solvent Polarity Indicators. Chem. Rev 1994, 94, 2319–2358. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Tran D; Hunt JP; Wherland S Molar volumes of coordination complexes in nonaqueous solution: correlation with computed van der Waals volumes, crystal unit cell volumes, and charge. Inorg. Chem 1992, 31, 2460–2464. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Matsumoto M; Swaddle TW The Decamethylferrocene(+/0) Electrode Reaction in Organic Solvents at Variable Pressure and Temperature. Inorg. Chem 2004, 43, 2724–2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).(a) Roth JP; Lovell S; Mayer JM Intrinsic Barriers for Electron and Hydrogen Atom Transfer Reactions of Biomimetic Iron Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 5486–5498. [Google Scholar]; (b) Iordanova N; Decornez H; Hammes-Schiffer S Theoretical Study of Electron, Proton, and Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in Iron Bi-imidazoline Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 3723–3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Soper JD; Mayer JM Slow Hydrogen Atom Self-Exchange Between Os(IV) Anilide and Os(III) Aniline Complexes: Relationships with Electron and Proton Transfer Self Exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 12217–12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Waidmann CR; Zhou X; Tsai EA; Kaminsky W; Hrovat DA; Borden WT; Mayer JM Slow Hydrogen Transfer Reactions of Oxo- and Hydroxo-Vanadium Compounds: the Importance of Intrinsic Barriers. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 4729–4743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Xie B; Elder T; Wilson LJ; Stanbury DM Internal Reorganization Energies for Copper Redox Couples: The Slow Electron-Transfer Reactions of the [CuII,I(bib)2]2+/+ Couple. Inorg. Chem 1999, 38, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Hattori S; Wada Y; Yanagida S; Fukuzumi S Blue Copper Model Complexes with Distorted Tetragonal Geometry Acting as Effective Electron-Transfer Mediators in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127 (26), 9648–9654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Fujisawa K; Fujita K; Takahashi T; Kitajima N; Moro-oka Y; Matsunaga Y; Miyashita Y; Okamoto K.-i. Synthetic models for active sites of reduced blue copper proteins: minimal geometric change between two oxidation states for fast self-exchange rate constants. Inorg. Chem. Commun 2004, 7, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.