Abstract

For several decades, understanding ageing and the processes that limit lifespan have challenged biologists. Thirty years ago, the biology of ageing gained unprecedented scientific credibility through the identification of gene variants that extend the lifespan of multicellular model organisms. Here we summarize the milestones that mark this scientific triumph, discuss different ageing pathways and processes, and suggest that ageing research is entering a new era that has unique medical, commercial and societal implications. We argue that this era marks an inflection point, not only in ageing research but also for all biological research that affects the human healthspan.

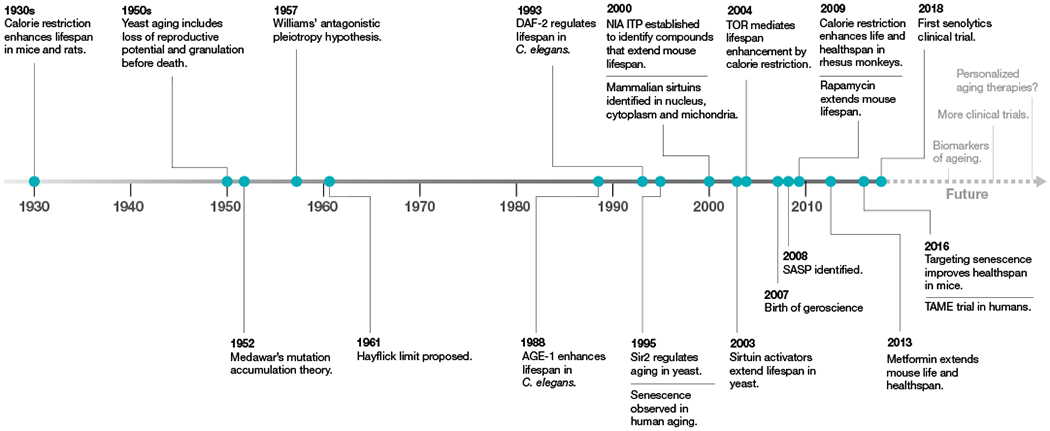

A key initial step in the field of ageing research was the observation in 1939 that restriction of caloric intake in mice and rats increased lifespan1 (Fig. 1). This discovery, reproduced in several species including, most recently, in primates2,3, was the first demonstration of the plasticity of the ageing process and a harbinger of the genetic studies that came 50 years later. Notably, dietary restriction increased not only the maximum lifespan but also suppressed the development of age-associated diseases4. These observations led to the concept that lifespan extension was associated with slowed ageing and increased healthspan—which describes both the length of healthy life and the fraction of total lifespan free from disease.

Fig. 1 |. Timeline of ageing research.

Key discoveries in the ageing field are highlighted, starting with the discovery of the effect of calorie restriction on ageing in 1930.

During the mid-1900s, the field began to debate the idea that ageing was the cause of age-related chronic disease. The use of the word ‘cause’ remains controversial because, although ageing is the largest risk factor for a multitude of age-related diseases5, causality has not been proven. In support of the idea, some apparently normal ageing phenomena, which interact with each other in a complex way, contribute to diseases. There was a realization that many of the molecular and biochemical mechanisms that determined the rate of ageing were also under investigation in laboratories that solely focused on individual chronic diseases. Increasingly, researchers who study lifespan genetics and work on disease models collaborate with scientists who have no expertise in ageing research. To distinguish this new field from gerontology, defined as the comprehensive multidisciplinary study of ageing and older adults, this interdisciplinary science at the interface of normal ageing and chronic disease was termed ‘geroscience’6.

A genetic approach to ageing research

Biologists have long known that lifespan is a heritable trait and thus has a genetic basis, as different species have radically different lifespans that range from days to decades. In 1952, Peter Medawar proposed that ageing is the result of the decline in the force of natural selection after reproduction7. This led some population-genetics and evolutionary biologists to culture large fly populations (usually Drosophila species) with high genetic diversity to selectively breed for late- and early-reproducing flies and test their genetic makeup. These studies showed that the late-reproducing flies lived almost twice as long as early-reproducing flies, and that these differences were heritable, supporting the model that genes determined lifespan8.

Over 30 years after Medawar’s writing on ageing, a landmark study in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans showed that a single gene, age-1, can determine the lifespan of an organism9. The lifespan of age-1-mutant worms increased by 40–60% on average9. This came as a surprise to many, as researchers assumed that hundreds or thousands of genes would be involved and that the effects of any single gene would be very small and even undetectable. Currently, over 800 genes have been identified that modulate lifespan in C. elegans according to GenAge (http://genomics.senescence.info/genes/search.php?organism=Caenorhabditis+elegans&show=4). The actual number of genes that modulate lifespan is probably higher, as new long-lived mutants continue to be identified and additional genes may also affect lifespan under different environmental conditions.

Ageing pathways and processes

The past 30 years of ageing research has transitioned from identifying ageing phenotypes to investigating the genetic pathways that underlie these phenotypes. The genetics of ageing research has revealed a complex network of interacting intracellular signalling pathways and higher-order processes10. Many of the pathways and processes, such as dietary restriction, that have been identified are known to be critical in homeostatic responses to environmental change.

Below, we selected a few key pathways and processes that have emerged during the past 30 years.

Insulin-like signalling pathway

In 1993, a C. elegans mutation in daf-2, which is involved in a switch between normal developmental progression and an alternate diapause larval stage (the dauer), was shown to almost double the adult lifespan11. This finding was followed by the discovery that two of the daf genes (daf-2 and daf-16) were located in a single pathway that influenced both the formation of the dauer larval stage and adult lifespan12. These ageing-associated genes were the C. elegans orthologues of mammalian genes that encode components of the insulin and insulin-like growth factor intracellular signalling pathway (ILS). age-1 turned out to be a phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase, daf-2 encodes an insulin-like receptor and daf-16 encodes a FOXO-like transcription factor that acts downstream of the insulin signalling pathway in mammals. This was supported by findings in yeast13 and flies14,15 that inhibition of components of the ILS pathway extended lifespan. This suggested that the earlier discoveries in worms were not a ‘private’ mechanism confined to nematodes but a common mechanism with the potential to be relevant to humans and human diseases.

Further studies in flies, worms and mice have since proven the conserved effects of inhibiting the insulin signalling pathway and extended lifespan16. Some alleles of the daf-16 orthologue in humans, FOXO3, are also associated with human centenarian populations across the globe17, which supports the idea that what we learn from model organisms may be relevant to ageing in humans.

Target of rapamycin

Target of rapamycin (TOR) proteins were first identified from rapamycin research. Rapamycin was originally discovered for its potent antifungal properties and later shown to inhibit the growth of cells and act as an immune modulator18,19. Insights into its mechanism of action came from the identification of mutants that suppressed the cell cycle-arrest properties of rapamycin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae18. These were later identified to be mutations in the genes that encode TOR1 and TOR2. Mammalian TOR genes are known as mTOR (mechanistic (or mammalian) target of rapamycin).

Studies have also elucidated the relationship between TOR and dietary restriction. Evolutionary hypotheses that explain the protective effects of dietary restriction argue that under nutrient restriction, there is a shift in metabolic investment from reproduction and growth towards somatic maintenance to extend survival10. The evidence for TOR as a conserved nutrient sensor made it an attractive candidate to mediate the switch between growth and maintenance and lifespan extension by dietary restriction across species. Consistently, flies with reduced activity of various components of the TOR pathway show extended lifespan in a manner that mimics dietary restriction20. A large-scale screen for long-lived mutants in yeast identified several mutations in the TOR pathway that also mimicked the effects of dietary restriction13,21. Notably, double mutants that carry mutations in genes of both the TOR and insulin signalling pathways have a nearly fivefold increased lifespan in C. elegans22. Both key longevity pathways—that is, TOR and ILS—have emerged as key parallel but interacting conserved nutrient-sensing pathways, with TOR being important for autonomous and the ILS pathway for non-autonomous growth signalling.

TOR is a versatile protein that acts as a major hub that integrates signals from growth factors, nutrient availability, energy status and various stressors10. These signals regulate several outputs that include mRNA translation, autophagy, transcription and mitochondrial function, which have been shown to mediate extended lifespan23.

Sirtuins and NAD+

In 1995, a genetic screen identified epigenetic ‘silencing’ factors as longevity genes24. Five years later, Sir2 was identified as a conserved protein that regulates replicative lifespan in yeast25. A key discovery was the demonstration that Sir2 was a protein deacetylase that removed acetyl groups from histone proteins in a manner that is dependent on the cellular coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)26. Another key demonstration was the fact that Sir2 was a key protein in the lifespan extension observed under dietary restriction in yeast27. Other organisms also express Sir2-related proteins called sirtuins, which generally function as protein deacylases that remove acyl groups, including acetyl, succinyl and malonyl, from lysine residues on target proteins28. Mice and humans express seven sirtuins that are characterized by a conserved catalytic domain and variable N- and C-terminal extensions. SIRT1, SIRT2, SIRT3, SIRT6 and SIRT7 are bona fide protein deacetylases, whereas SIRT4 and SIRT5 do not exhibit deacetylase activity but remove other acyl groups from lysine residues in proteins29. Notably, SIRT1, SIRT2, SIRT6 and SIRT7 appear to function as epigenetic regulators, whereas SIRT3, SIRT4 and SIRT5 are located in mitochondria29. Sirtuins have emerged as global metabolic regulators that control the response to calorie restriction and protecting against age-associated diseases, thus increasing healthspan and—in some cases—lifespan30–33.

NAD+ is a critical redox coenzyme found in all living cells. It serves both as a critical coenzyme for enzymes that fuel reduction-oxidation reactions by carrying electrons from one reaction to another, and as a cosubstrate for other enzymes, such as sirtuins and polyadenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerases (PARPs). There is increasing evidence that NAD+ levels and the activity of sirtuins decrease with age and during senescence or in animals on a high-fat diet. By contrast, NAD+ levels increase in response to fasting, glucose deprivation, dietary restriction and exercise, which are all conditions associated with a lower energy load34–40. The fact that NAD+ levels increase under conditions that increase lifespan and healthspan, such as dietary restriction and exercise, and decrease during ageing or under conditions that decrease lifespan and healthspan, such as a high-fat diet, support the working model that decreased NAD+ levels might contribute to the ageing process. On the basis of this idea, it has been predicted and validated that NAD+ supplementation exerts protective effects during ageing41,42.

Circadian clocks

Research on sirtuins has also helped us to understand the link between circadian clocks and ageing. NAD+ levels fluctuate in a circadian manner and link the peripheral clock to the transcriptional regulation of metabolism by epigenetic mechanisms through SIRT1. The core circadian clock machinery, BMAL1 and CLOCK, directly regulates expression of NAMPT in the NAD+ salvage pathway in mice38. The deacetylase activity of SIRT1 depends on the presence of NAMPT to generate NAD+. The possibility that NAD+ concentrations are regulated semi-independently in different cellular compartments suggests that changes in unique local NAD+ concentrations could differentially affect the activity of distinct sirtuins.

Similarly, several other homeostatic responses are regulated by circadian clocks that are vital to maintaining health by rhythmic activity of neuronal, physiological and endocrine functions. One of the common hallmarks of ageing is the progressive loss of circadian behavioural patterns (sleep-wake cycles) and a dampening of circadian gene expression43. Given that the network of circadian clocks modulates various biological processes, it is not surprising that disruption of circadian rhythms—genetically or through environmental perturbation—is linked with age-related pathologies, including neurodegeneration, obesity and type 2 diabetes43.

Dietary restriction is also emerging as an important factor that can influence peripheral clocks, as it promotes circadian homeostasis in flies and mice by enhancing the circadian-regulated amplitude of gene expression44,45. More importantly, circadian clocks are required for the protective effects of dietary restriction on lifespan extension in both flies and mice44,45. There is an increase in the expression of rhythmic genes in the liver after dietary restriction that include targets of SIRT1, NAD+ metabolites and protein acetylation46. Time-restricted feeding, in which feeding is restricted to shorter periods when an organism is active, has emerged as a potential paradigm to improve circadian and metabolic homeostasis, resulting in increased healthspan47. These findings suggest that circadian rhythms are more than just a biomarker of ageing and may be a driving factor in organismal ageing.

Mitochondria and oxidative stress

In the 1950s, it was theorized that endogenous production of free radical molecules arising from oxygen and generated during fundamental metabolic processes, such as respiration, represent a key factor that drives ageing48. These theories particularly focused on mitochondrial production of superoxide as a key mediator of ageing pathophysiology49. Indeed, numerous publications have shown that oxidative damage accumulates in multiple tissues and species with age. Although it is indisputable that such damage is one of the most consistent consequences of increasing age in cells and tissues, whether such damage is a cause or a consequence of ageing has proved to be hard to determine. The free radical theory of ageing has proved extremely difficult to test, at least in part because reactive oxygen species are also important signalling molecules. Numerous studies have shown that the modulation of respiration can extend lifespan in model organisms50–53.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, model organisms were used to overexpress key genes involved in detoxifying free radical molecules such as superoxide. There were multiple successes that led to lifespan extension54,55, which suggests that oxidative damage arising from metabolism was limiting lifespan—at least to some degree. However, this finding was challenged by subsequent studies in mice that showed no increase in the lifespan of wild-type animals56 in which the key mitochondrial antioxidant protein superoxide dismutase 2 was overexpressed. However, further studies that specifically targeted the hydrogen peroxide scavenger protein catalase to the mitochondria resulted in improved healthspan and increased lifespan in mice57–59. The contradiction between these two findings in mice suggests that simple genetic overexpression in mammalian systems is very context-specific. This is not surprising, as free radical production within the mitochondria is complex, with at least ten sites of production within the respiratory chain60, and the rate of production under diverse physiological states, at various ages and in different cell types remains relatively poorly explored and characterized61.

Although free radicals are generally implicated in cellular damage and inflammation when present at high levels, they can also potentially increase cellular defenses through an adaptive response (termed ‘mitohormesis’) when present at lower levels62. Mitohormesis explains the paradoxical increase in lifespan observed after disruption of mitochondrial function in worms, flies and mice63,64. Genome-wide screens for lifespan extension in C. elegans revealed that disruption of several genes involved in the electron transport chain extended lifespan52,65. Inhibition of genes in the mitochondrial electron transport chain triggers the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt), which is also required for the extended lifespan found in these C. elegans mutants66. Disruption of mitochondrial function in neurons activates the UPRmt in distal tissues such as the intestine, which suggests the existence of circulating factors that coordinate metabolism between tissues66. Mitochondrial perturbation triggered a nuclear transcriptional response that regulates a large set of genes involved in protein folding, antioxidant defenses and metabolism. UPRmt is regulated by several factors including activating transcription factor associated with stress-1 (ATFS-1), the homeobox transcription factor DVE-1, the ubiquitin-like protein UBL-5, the mitochondrial protease ClpP and the inner mitochondrial membrane transporter HAF-167.

Studies that demonstrate the importance of mitohormesis in extending lifespan pose several challenges to the field as it is unclear whether using antioxidants would be a good strategy for lifespan extension. As a result, there is evidence both for and against lifespan extension by increasing oxidative stress63. It is also unclear how the above findings can be reconciled with results that show that mitochondrial function is enhanced by dietary restriction in multiple species68–70. Further studies are needed to determine how differing states of mitochondrial function influence ageing in different contexts.

Senescence

Nearly 60 years ago, the first formal description of the limited ability of human cells to divide in culture was published71,72. This phenomenon is now known to be an example of a more general phenomenon termed cellular senescence. Senescent cells are characterized by three main features: arrested cell proliferation, resistance to apoptosis and a complex senescence-associated secretory phenotype73. The senescence that limits cell proliferation is caused mostly by the short, dysfunctional telomeres that result from repeated DNA replication in the absence of telomerase74. Dysfunctional telomeres trigger a persistent DNA-damage response, which in turn induces cell cycle arrest75 and the expression of pro-inflammatory factors that are associated with the senescence-associated secretory phenotype76. Similarly, at least some of the oncogenes that induce senescence do so by causing replication stress and subsequent DNA damage77,78. However, other stressors can drive cells into senescence without a DNA-damage response, including epigenomic perturbations79 and mitochondrial dysfunction80.

Senescent cells are more abundant in aged and diseased tissues in multiple species81. Cell culture studies showed that senescent cells can fuel hallmarks of a variety of ageing phenotypes and diseases, largely through the cell non-autonomous effects of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype82. The development of two transgenic mouse models in which senescent cells can be selectively eliminated confirmed the idea that senescent cells can have a causal role in many age-related phenotypes and pathologies in vivo83,84. Both models have been used to show that senescent cells are drivers of a large number of age-related pathologies—at least in mice. These pathologies include Alzheimer’s85 and Parkinson’s86 disease, atherosclerosis87, cardiovascular dysfunction88 (including cardiovascular problems caused by certain genotoxic chemotherapies89), tumour progression88,89, loss of haematopoietic and skeletal muscle stem cell functions90, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease91, pulmonary fibrosis92, osteoarthritis93 and osteoporosis94.

This leads to the question of whether compounds could be identified that can eliminate senescent cells, similar to the action of the mouse transgenes, and that are therefore potentially translatable to use in humans. This approach led to the identification of a new class of drugs, termed senolytics, that is rapidly expanding90,95–99. Many senolytic drugs have been tested in mice and human cells or tissues, with promising results. However, clinical trials have only recently started and it therefore remains to be determined whether these drugs are safe and efficacious in humans.

Chronic inflammation

Senescence of the immune system (known as immunosenescence) is one of the causes of ‘inflammaging’, a term coined in 2000100 that refers to a phenomenon in which older organisms tend to have higher levels of inflammatory markers in their cells and tissues, which results in a low-grade, sterile and chronic pro-inflammatory status. In contrast to acute, transient inflammation—an evolutionarily conserved mechanism designed to protect the host from infections and injuries—inflammaging is linked to a myriad of age-related diseases such as cancer, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative diseases and frailty101–105.

Other factors that contribute to inflammaging include genetic susceptibility, obesity, oxidative stress, changes in the permeability of the intestinal barrier associated with translocation of bacterial products (‘leaky gut’), chronic infection and defective immune cells104 and pro-inflammatory factors that are associated with the senescence-associated secretory phenotype of non-immune senescent cells76. In addition, numerous environmental factors—such as the chemicals identified by the Tox21 consortium106—can be cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory101,102. Finally, longevity-enhancing interventions such as dietary restriction reduce inflammatory biomarkers107,108. On the basis of these findings, inflammaging is now considered to be a biomarker for accelerated ageing and one of hallmarks of ageing biology.

As discussed for other variables that influence ageing, an extended lifespan and healthspan may be a result of a fine balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory processes109. Consistent with this idea, it has been shown that although centenarians have an increased level of pro-inflammatory molecules (for example, interleukin-6, a commonly used marker for chronic morbidity105), the adverse consequences associated with these pro-inflammatory molecules are counterbalanced by high levels of anti-inflammatory molecules110.

Proteostasis

Protein homeostasis (known as proteostasis) is an essential process that maintains protein structure and function, a process that degrades during ageing. Proteome stability is associated with naturally long lifespan in organisms such as the naked mole-rat, which is characterized by high levels of homeostatic proteolytic activity111–113. During normal ageing, many hundreds of proteins become insoluble and accumulate in a wide variety of tissues. In C. elegans, these insoluble proteins are highly enriched for proteins that determine lifespan114,115. It appears that a proteome-wide failure in proteostasis accelerates ageing.

The major pathways that determine lifespan also regulate aspects of proteostatic factors. For example, insulin signalling pathways control the expression of molecular chaperones and TOR signalling pathways regulate many forms of autophagy including mitoautophagy, which is the mechanism by which damaged mitochondria are removed from the cell. Age-related failure in proteostasis may be mechanistically responsible for the processing and folding of neurotoxic peptides associated with Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and other proteotoxic diseases116. Indeed, this may be why age is such a high-risk factor for neurological diseases that are marked by protein aggregation.

An inflection point in ageing interventions

The rapid increase in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms that underlie ageing has created new opportunities to intervene in the ageing process. Two notable findings have emerged from these early studies. First, the number of genes that can extend lifespan is much larger than expected, which suggests a much higher level of plasticity in the ageing process than expected. Second, genes that control ageing—which define cellular pathways such as the TOR and insulin signalling pathways—are remarkably conserved in yeast, worms, fruit flies and humans. The conservation of these pathways across wide evolutionary distances and the fact that targeting these pathways in model organisms increases both lifespan and healthspan has brought to the fore the idea of interventions in humans.

Rapidly ageing societies across the world are seeing an increasing healthcare burden attributable to both morbidity and cost of age-related diseases, such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, neurodegeneration, osteoarthritis and macular degeneration. However, current medical care is highly segmented as well as organ- and disease-based, and ignores the fact that age and the ageing process are the strongest risk factor for each of these diseases. According to the concept of geroscience, targeting conserved ageing pathways is anticipated to protect against multiple diseases and represents a different approach to tackling the rapidly growing burden of diseases worldwide (Table 1).

Table 1 |.

Interventions to increase healthspan and/or lifespan

| Intervention | Target or process | Major effects |

|---|---|---|

| Rapamycin | mTOR | Geroprotective effects in mice and dogs. Human clinical trials with rapamycin and rapalogs are underway. |

| Senolytics | Cellular senescence | Protective against age-related disease in mice. Ongoing clinical trials in human diseases, including arthritis and eye degeneration. |

| NAD precursors | NAD metabolism | Geroprotective in animal models. Supplements available for human consumption, but no clinical trials have been reported yet. |

| Sirtuin-activating compounds | Sirtuins | Geroprotective in rodents and non-human primates but mixed results in humans; SRT2104 may have effects beyond mitigating some age-associated conditions. |

| Metformin | Mitochondrial respiration | Associated with increased lifespan in human patients with diabetes and decreased risk of cancer. TAME trial is planned to test effects in individuals without diabetes. |

| Exercise | Unknown | Associated with reduced risk of age-related disease, improved quality of life and increased lifespan in humans. |

| Calorie restriction | Several targets, including mTOR and sirtuins | Enhanced lifespan and protection from disease in worms, flies, mice, rats and non-human primates. Associated with decreased risk factors for disease in humans. |

Several key interventions that are currently under investigation in human trials for their potential to increase healthspan and lifespan are described (see text for further details).

Using geroscience to treat age-related disease

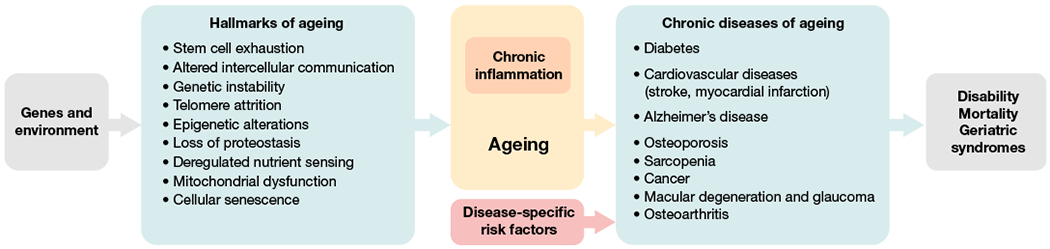

The concept of geroscience predicts that conserved ageing pathways are part of the pathophysiology of many age-related conditions and diseases (Fig. 2). For example, multimorbidity is seen as the multisystem expression of an advanced stage of ageing rather than a coincidence of unrelated diseases117. Targeting conserved ageing pathways should, therefore, prevent or ameliorate multiple clinical problems. This hypothesis remains to be tested in clinical trials, but is supported by several lines of evidence. A wide range of animal models of specific diseases can be affected by manipulating a single ageing mechanism (such as NAD+)118 or senescent cells95 in the laboratory. Rates of individual age-related diseases and of multimorbidity increase nonlinearly with age, and the rate of acquiring new chronic diseases may be higher in people who have an existing chronic disease119.

Fig. 2 |. The concept of geroscience and its approach to age-related disease.

Environmental and genetic factors exert influences on a number of key cellular processes and pathways, which have recently been defined as the hallmarks of ageing193. Many of these pathways contribute to the creation of a chronic inflammatory stage and to ageing. These in turn increase the risk for chronic diseases of ageing together with disease-specific risk factors (for example, cholesterol level and high-blood pressure can lead to cardiovascular diseases such as stroke and myocardial infarction).

Certain populations, such as people who live with HIV or are homeless, show an early onset of a wide range of age-related chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes that are not necessarily related to their specific disease risks120,121. A classic statistical analysis of human mortality showed that even curing an entire category of chronic disease, such as all types of cancer or cardiovascular diseases, would only modestly increase life expectancy owing to the expected mortality from other chronic diseases122. Conversely, humans with extreme longevity who presumably have favourable ageing mechanisms show delayed onset of most major chronic diseases123.

In clinical care, multimorbidity is increasingly viewed as an entity unto itself that requires a specific integrative management plan124, as intensive but uncoordinated treatment of individual diseases can give rise to the harmful syndrome of polypharmacy125. Frailty measures are the most widely used clinical assessments for quantifying the stage of ageing126,127, and these clinical biomarkers of ageing predict mortality while awaiting liver transplant128, complications of surgery129 and whether the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease manifests as clinical dementia130. Taken together, experimental data from preclinical models, epidemiological patterns of age-related conditions and the power of non-disease-specific clinical ageing assessments such as frailty to predict risk and mortality in diverse contexts all suggest that intervening in mechanisms of ageing could have broad clinical benefit.

Challenges ahead

However, to move from simple organisms to humans several key difficulties need to be overcome, as discussed below. First, it is already clear from the study of model systems that interventions that are beneficial in a given genetic environment might not work in another. For example, analyses of dietary restriction in multiple recombinant inbred mice strains found both an increase and a decrease in lifespan, which was dependent on the strain131. Similar results have been obtained using more than 150 strains of flies132. The molecular basis for these differences in response to what had been assumed to be a universally beneficial intervention has not been established. Future studies in invertebrates such as yeast, worms and flies hold promise for systematically explaining the genetic basis of lifespan extension by dietary restriction.

The human population is also characterized by a large genetic heterogeneity that has a critical role in disease susceptibility, lifespan and the response to drugs of an individual. This heterogeneity is the basis for the current field of precision medicine, which aims to identify critical genetic determinants of disease and to customize interventions and treatments to unique genetic variants. In the future, the field of precision medicine and geroscience will have to interact closely. As discussed above, FOXO3 is related to the DAF–insulin pathway, and unique polymorphisms in FOXO3 are found in centenarians around the world17. Furthermore, the APOE gene is involved in cholesterol metabolism, and unique alleles are associated with longevity and a lower risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease133,134. Many additional genes135, such as SIRT6136, are now known to be associated with human longevity.

Just as several animal studies have challenged the universality of the benefits of dietary restriction137–139, it is likely that pharmacological interventions will work with different success in distinct humans, owing to the natural genetic variation in the population138. As in mice, it has been hypothesized that selective pressures on the response to nutrient availability may vary across different human populations, resulting in genetic differences that may influence diabetes and obesity140. Furthermore, most of the interventions have arisen from research to show protection against ageing in animals. Thus, it is possible that humans that have optimized their nutrition and exercise are unlikely to derive much benefit from these interventions. Future studies on tailoring interventions based on personalized medicine approaches are likely to be most successful in deriving the most benefit from these interventions.

Additionally, it is clear that studies in mice are not always predictive for humans. Many important discoveries in mice have been translated successfully in humans, but many others have not. This can be due to intrinsic biological differences between mice and humans. In addition, the complexity of biology and the multiplicity of recognized and unrecognized variables that affect biological phenotypes have caused reproducibility problems between different laboratories that study the same organisms, not only in studies of mice but also other model systems141.

Although there are many examples of a connection between long lifespan and increased healthspan, more-recent studies in mice142,143, flies132 and worms144–146 have questioned the assumption that lifespan extension is always accompanied by an increase in healthspan. Future studies will need to address the effects of interventions on both of these aspects before attempting to translate these interventions into the treatment of human patients.

Drugs undergoing clinical trials

Both drugs that are being developed to target ageing and some drugs that are commonly used behave as geroprotectors in animal models. The multicentre Intervention Testing Program (ITP), which is supported by the National Institute for Ageing, has identified five drugs that reproducibly increase lifespan in genetically heterogenous mice147, including rapamycin, acarbose, nordihydroguaiaretic acid, 17-α-oestradiol and aspirin147. Some of these drugs also improve healthspan measures in some tissues of animal models148–150. Drugs found in other studies to extend rodent lifespan include metformin151 (although it did not repeat in the ITP at the same dose), drugs targeting the angiotensin-converting enzyme and the aldosterone receptor, and the sirtuin activators SRT2104152 and SRT1720153. Further work will be necessary to validate that these drugs act as true geroprotectors in model organisms.

A key question is how these interventions will be tested and eventually used clinically in humans. Geroscience predicts that ageing therapies will ameliorate or prevent several age-related diseases and conditions simultaneously. Clinical trials to test this hypothesis should therefore use clinical outcomes that inherently depend on multiple age-related diseases or conditions. Examples include multimorbidity, or the combination of several age-related chronic diseases; the multifactorial geriatric syndromes such as frailty or delirium; or resilience to health stressors such as surgery or infection154. Multimorbidity and frailty are also widely incorporated into measures of age-related risk that inform clinical decision-making155. Other examples of such measures that could be useful trial outcomes include grip strength, gait speed156, timed-up-and-go and activities of daily living.

These clinical measures of ageing could be useful for selecting patients at higher age-related risk to receive interventions. For example, the risk of multimorbidity increases steeply with age119; however, developing one chronic disease increases the risk of developing another by several fold157. How early or late in the ageing process interventions can be effective remains to be seen, although animal studies of drugs and human studies of exercise provide some reassurance that the window of opportunity extends quite late in life. At least five major classes of drugs are currently being tested in humans for their geroprotective potential.

Metformin.

Metformin is a widely prescribed antidiabetic drug that has been found to target several molecular mechanisms of ageing158. A retrospective analysis of patients with diabetes who received metformin showed increased lifespan in comparison to individuals without diabetes159. In randomized trials, metformin prevented the onset of diabetes, improved cardiovascular risk factors and reduced mortality160,161. Epidemiological studies have suggested that metformin use might also reduce the incidence of cancer and neurodegenerative disease158. These data underpin the proposed Targeting Aging with MEtformin (TAME) study, a large randomized controlled trial of metformin given to 65- to 80-year-old individuals without diabetes who are at high risk for the development of chronic diseases of ageing. The primary outcome of TAME is a composite of death or new major age-related chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, cancer and dementia. Other outcomes include geriatric measures such as mobility, independence in activities of daily living and cognitive function162.

Rapamycin analogues.

The compound identified by the ITP that has perhaps the most reproducible effects on lifespan is rapamycin. Rapamycin inhibits the TOR pathway, extends the lifespan of yeast and flies and increases mean and maximum lifespan in mice from multiple genetic backgrounds163–165. These basic research data led to a unique clinical trial that studied the effects of rapamycin on heart function, cognition, cancer and lifespan in household companion dogs as a preclinical model166. Rapamycin (also known as sirolimus) and its analogue everolimus are approved for clinical use as immunosuppressants in solid organ transplantation. Healthy older adults given a non-immunosuppressive dose of everolimus for six weeks showed an improved immunological response to influenza vaccination19. A subsequent clinical trial found that six weeks of low-dose everolimus plus a second TOR inhibitor improved vaccine response and, provocatively, reduced infection rates by over a third during the subsequent nine months167. These were two of the first examples of clinical trials that target a syndrome of ageing—immunosenescence—with a drug that targets the mechanisms of ageing.

Senolytics.

As discussed above, senolytic drugs—drugs that selectively target and eliminate senescent cells—have showed great geroprotective potential in animal models95. Some of these drugs are natural products96,97, whereas others are synthetic small molecules90,98,99. A growing number of biotechnology companies and research laboratories are developing new or repurposed senolytics that have just begun to be tested for safety in humans, with no results—thus far—regarding efficacy.

Sirtuin activators.

Sirtuin-activating compounds (STACs) enhance sirtuin activity and increase healthspan in mice and non-human primates168. However, mixed conclusions have been observed in clinical trials. Resveratrol (a natural STAC) and SRT1720 (an early synthetic STAC) have shown promising results in preclinical trials but failed in clinical trials, owing to low bioavailability, potency and limited target specificity169. The most promising synthetic STAC so far is SRT2104, a highly specific SIRT1 activator; the compound has completed several small clinical studies of effects on cardiovascular and metabolic markers, including in type 2 diabetes, cigarette smokers and the elderly, with larger trials underway118.

NAD+precursors.

NAD+ precursors such as nicotinamide riboside and nicotinamide mononucleotide aim to supplement the age-associated decrease in cellular NAD levels69. In animal models, both precursors have shown geroprotective activity against a number of ageing-associated diseases. Several companies are currently selling nicotinamide riboside and nicotinamide mononucleotide as supplements online. Although these supplements increase NAD levels in humans170, no efficacy or geroprotective effects for humans have been demonstrated thus far.

Exercise improves healthspan

Although much hope and investment are currently focused on drug development, it is important to note that exercise behaves as a true and effective geroprotector. In the absence of suitable treatments for age-related dysfunction, exercise is currently the only intervention that has shown a remarkable efficacy for reducing the incidence of age-related disease171,172, improving the quality of life173 and even increasing mean and maximum lifespan in humans174,175. Its benefits can be seen even with modest implementation173. Although the key molecular players that mediate the protective effects of exercise against age-related disease are unknown, efforts are underway to identify the molecular players and whether we can harness such knowledge to improve the health of the ageing population.

Nutrition and ageing

Diet is probably one of the most important influences on health and ageing. However, it is an enormously complicated topic and beyond the scope of this Review (extensive discussion on this topic has previously been published176). The field of ageing has focused almost exclusively on the lifespan and healthspan effects of dietary restriction but, at the other end of the spectrum, overeating and the accompanying obesity shortens lifespan and decreases healthspan. In between these two extremes, there is strong evidence that optimal eating is associated with increased life expectancy and a reduction in the risk of all types of chronic disease. Many claims have been made for the competitive merits of different diets relative to one another. However, it is very difficult to conduct rigorous, long-term studies that compare different diets for their lifespan and healthspan effects using methodology that is devoid of bias and confounding variables. Without such direct comparisons, no specific diet can claim superiority over any others. However, a number of themes have emerged from studies that compare different diets and from the study of populations that are geographically associated with increased longevity (so-called ‘blue zones’). Diets that favour longevity and healthspan are generally characterized by minimally processed foods, being predominantly plant-based, low alcohol consumption and a lack of overeating.

Exciting recent developments are emerging in the nutrition field, such as intermittent fasting177, diets that mimic fasting178 and time-restricted feeding179. Recently, interest has grown in a ketogenic diet that is characterized by the endogenous production of high levels of the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate. This diet has long been used as a treatment for childhood epilepsy and was recently shown to increase healthspan in two separate studies in mice180–182. The studies are supported by recent findings that β-hydroxybutyrate modulates the enzymatic activity of the epigenetic regulators, histone deacetylases, and thereby activates the expression of FOXO3183. Future research will focus on the healthspan and possible lifespan of these dietary interventions and the identification of their interactions with pathways that regulate ageing.

The need for biomarkers of ageing

The field of geroscience needs biomarkers to assess the ageing process and the efficacy of interventions to bypass the need for large-scale longitudinal studies. Medicine has undergone a progressive transformation during the past 40 years, changing from ‘sick care’—that is, care primarily focused on treating diseases after they occurred—to ‘healthcare,’ in which unique risk factors for disease development are recognized and suppressed before disease onset. For example, neither high plasma cholesterol nor high blood pressure is a disease by itself but both are important risk factors for the development of myocardial infarction and strokes.

Similarly, ageing is not a disease but a notably strong risk factor for multiple diseases that include myocardial infarction, stroke, some ageing-associated cancers, macular degeneration, osteoarthritis, neurodegeneration and many other diseases. For example, cardiovascular risk doubles every 10 years past the age of 40, even after adjustment for other risk factors—the rough equivalent of adding a major new risk factor (smoking, hypertension and so on) every decade184. Decades of cardiovascular studies identified risk factors and showed that treating risk factors even when patients are asymptomatic prevented harm. Treatment guided by these cardiovascular biomarkers now extends earlier and earlier in life. The availability of true biomarkers of ageing, and associated clinical health outcomes and malleability to interventions162, would allow geroprotectors to be tested on an accelerated time scale. They would further allow for early identification of patients at high age-related risk throughout life and in various clinical contexts to target geroprotective treatments.

Early efforts to identify such markers have been unsuccessful, but recent developments using newer technologies such as high-throughput proteomics, transcriptomics and epigenomics indicate that such biomarkers do exist and could be of high clinical importance185. One possible biomarker, the epigenetic clock, is based on the measurement of DNA methylation at multiple sites and appears to correlate with biological age and age-related risk more than chronological age186–188. Advanced glycation end products represent another potential biomarker that accumulates with age and in several age-related diseases189. Furthermore, increased levels of some advanced glycation end products are also associated with increased mortality in humans190. There already is evidence that ageing biomarkers can be modified by interventions that target ageing, such as in the CALERIE study of calorie restriction in humans191. The identification of further biomarkers that predict biological age and disease risk will represent a huge stride forward in the efforts to combat age-related disease and dysfunction in humans.

We are now entering an exciting era for research on ageing. This era holds unprecedented promise for increasing human healthspan: preventing, delaying or—in some cases—reversing many of the pathologies of ageing based on new scientific discoveries. Whether this era promises to increase the maximum life span of humans remains an open question192. What is clear is that, 30 years after the fundamental discoveries that link unique genes to ageing, a solid foundation has been built and clinical trials that directly target the ageing process are being initiated. Although considerable difficulties can be expected as we translate this research to humans, the potential rewards in terms of healthy ageing far outweigh the risks.

Acknowledgements

We thank I. Park and D. Powell for editing/proofreading this Review and J. Carroll for assistance with figures.

Footnotes

Competing interests J.C. is a scientific founder of Unity Biotechnology, a company that develops senolytics. G.J.L. and S.M. are scientific founders of Gerostate Alpha, a drug-development company focused on creating novel pharmaceuticals that mitigate age-related disease and dysfunction. J.C.N. and E.V are scientific founders of BHB Therapeutics, a company focused on the therapeutic effects of the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate. E.V. is a scientific founder of Napa Therapeutics, a company that studies NAD metabolism during ageing.

References

- 1.McCay CM, Maynard LA, Sperling G & Barnes LL Retarded growth, life span, ultimate body size and age changes in the albino rat after feeding diets restricted in calories: four figures. J. Nutr 18, 1–13 (1939). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study shows that the restriction of calories without malnutrition prolongs mean and maximum lifespan in rats compared to ad libitum feeding.

- 2.Mattison JA et al. Caloric restriction improves health and survival of rhesus monkeys. Nat. Commun 8, 14063 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pifferi F et al. Caloric restriction increases lifespan but affects brain integrity in grey mouse lemur primates. Commun. Biol 1, 30 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Omodei D & Fontana L Calorie restriction and prevention of age-associated chronic disease. FEBS Lett. 585, 1537–1542 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niccoli T & Partridge L Ageing as a risk factor for disease. Curr. Biol 22, R741–R752 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy BK et al. Geroscience: linking aging to chronic disease. Cell 159, 709–713 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medawar PB An Unsolved Problem of Biology (H. K. Lewis, 1952). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rose M & Charlesworth B A test of evolutionary theories of senescence. Nature 287, 141–142 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrates that delaying the age of reproduction for several generations extends lifespan.

- 9.Friedman DB & Johnson TE A mutation in the age-1 gene in Caenorhabditis elegans lengthens life and reduces hermaphrodite fertility. Genetics 118, 75–86 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study describes a C. elegans mutant strain that has an extended lifespan.

- 10.Kapahi P et al. With TOR, less is more: a key role for the conserved nutrient-sensing TOR pathway in aging. Cell Metab. 11, 453–465 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A & Tabtiang R A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature 366, 461–464 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study described that a mutation in the daf-2 gene that enhances dauer formation also extends lifespan.

- 12.Ogg S et al. The Fork head transcription factor DAF-16 transduces insulin-like metabolic and longevity signals in C. elegans. Nature 389, 994–999 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fabrizio P, Pozza F, Pletcher SD, Gendron CM & Longo VD Regulation of longevity and stress resistance by Sch9 in yeast. Science 292, 288–290 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tatar M et al. A mutant Drosophila insulin receptor homolog that extends life-span and impairs neuroendocrine function. Science 292, 107–110 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clancy DJ et al. Extension of life-span by loss of CHICO, a Drosophila insulin receptor substrate protein. Science 292, 104–106 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartke A Impact of reduced insulin-like growth factor-1/insulin signaling on aging in mammals: novel findings. Aging Cell 7, 285–290 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willcox BJ et al. FOXO3A genotype is strongly associated with human longevity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 13987–13992 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heitman J, Movva NR & Hall MN Targets for cell cycle arrest by the immunosuppressant rapamycin in yeast. Science 253, 905–909 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mannick JB et al. mTOR inhibition improves immune function in the elderly. Sci. Transl. Med 6, 268ra179 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kapahi P et al. Regulation of lifespan in Drosophila by modulation of genes in the TOR signaling pathway. Curr. Biol 14, 885–890 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study shows that lifespan extension by dietary restriction in flies is due to inhibtion of the TOR kinase.

- 21.Kaeberlein M et al. Regulation of yeast replicative life span by TOR and Sch9 in response to nutrients. Science 310, 1193–1196 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen D et al. Germline signaling mediates the synergistically prolonged longevity produced by double mutations in daf-2 and rsks-1 in C. elegans. Cell Rep. 5, 1600–1610 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapahi P, Kaeberlein M & Hansen M Dietary restriction and lifespan: lessons from invertebrate models. Ageing Res. Rev 39, 3–14 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kennedy BK, Austriaco NR Jr, Zhang J & Guarente L Mutation in the silencing gene SIR4 can delay aging in S. cerevisiae. Cell 80, 485–496 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaeberlein M, McVey M & Guarente L The SIR2/3/4 complex and SIR2 alone promote longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by two different mechanisms. Genes Dev. 13, 2570–2580 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M & Guarente L Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature 403, 795–800 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin SJ, Defossez PA & Guarente L Requirement of NAD and SIR2 for life-span extension by calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 289, 2126–2128 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study shows that lifespan extension by glucose restriction in yeast requires the activity of Sir2.

- 28.North BJ & Verdin E Sirtuins: Sir2-related NAD-dependent protein deacetylases. Genome Biol. 5, 224 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carrico C, Meyer JG, He W, Gibson BW & Verdin E The mitochondrial acylome emerges: proteomics, regulation by sirtuins, and metabolic and disease implications. Cell Metab. 27, 497–512 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen HY et al. Calorie restriction promotes mammalian cell survival by inducing the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science 305, 390–392 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanfi Y et al. The sirtuin SIRT6 regulates lifespan in male mice. Nature 483, 218–221 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Satoh A et al. Sirt1 extends life span and delays aging in mice through the regulation of Nk2 homeobox 1 in the DMH and LH. Cell Metab. 18, 416–430 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Someya S et al. Sirt3 mediates reduction of oxidative damage and prevention of age-related hearing loss under caloric restriction. Cell 143, 802–812 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cantó C et al. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature 458, 1056–1060 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen D et al. Tissue-specific regulation of SIRT1 by calorie restriction. Genes Dev. 22, 1753–1757 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Costford SR et al. Skeletal muscle NAMPT is induced by exercise in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab 298, E117–E126 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fulco M et al. Glucose restriction inhibits skeletal myoblast differentiation by activating SIRT1 through AMPK-mediated regulation of Nampt. Dev. Cell 14, 661–673 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakahata Y, Sahar S, Astarita G, Kaluzova M & Sassone-Corsi P Circadian control of the NAD+ salvage pathway by CLOCK-SIRT1. Science 324, 654–657 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramsey KM et al. Circadian clock feedback cycle through NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis. Science 324, 651–654 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodgers JT et al. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1α and SIRT1. Nature 434, 113–118 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belenky P, Bogan KL & Brenner C NAD+ metabolism in health and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci 32, 12–19 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mouchiroud L et al. The NAD+/Sirtuin pathway modulates longevity through activation of mitochondrial UPR and FOXO signaling. Cell 154, 430–441 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kondratov RV A role of the circadian system and circadian proteins in aging. Ageing Res. Rev 6, 12–27 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katewa SD et al. Peripheral circadian clocks mediate dietary restriction-dependent changes in lifespan and fat metabolism in Drosophila. Cell Metab. 23, 143–154 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patel SA, Chaudhari A, Gupta R, Velingkaar N & Kondratov RV Circadian clocks govern calorie restriction-mediated life span extension through BMAL1- and IGF-1-dependent mechanisms. FASEB J. 30, 1634–1642 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sato S et al. Circadian reprogramming in the liver identifies metabolic pathways of aging. Cell 170, 664–677 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Longo VD & Panda S Fasting, circadian rhythms, and time-restricted feeding in healthy lifespan. Cell Metab. 23, 1048–1059 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harman D Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J. Gerontol 11, 298–300 (1956). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harman D The biologic clock: the mitochondria? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 20, 145–147 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ristow M & Zarse K How increased oxidative stress promotes longevity and metabolic health: the concept of mitochondrial hormesis (mitohormesis). Exp. Gerontol 45, 410–418 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Houtkooper RH et al. Mitonuclear protein imbalance as a conserved longevity mechanism. Nature 497, 451–457 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dillin A et al. Rates of behavior and aging specified by mitochondrial function during development. Science 298, 2398–2401 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee S-J, Hwang AB & Kenyon C Inhibition of respiration extends C. elegans life span via reactive oxygen species that increase HIF-1 activity. Curr. Biol 20, 2131–2136 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun J, Folk D, Bradley TJ & Tower J Induced overexpression of mitochondrial Mn-superoxide dismutase extends the life span of adult Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 161, 661–672 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tower J Transgenic methods for increasing Drosophila life span. Mech. Ageing Dev 118, 1–14 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pérez VI et al. The overexpression of major antioxidant enzymes does not extend the lifespan of mice. Aging Cell 8, 73–75 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee HY et al. Mitochondrial-targeted catalase protects against high-fat diet-induced muscle insulin resistance by decreasing intramuscular lipid accumulation. Diabetes 66, 2072–2081 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dai DF et al. Overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria attenuates murine cardiac aging. Circulation 119, 2789–2797 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schriner SE et al. Extension of murine life span by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. Science 308, 1909–1911 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brand MD The sites and topology of mitochondrial superoxide production. Exp. Gerontol 45, 466–472 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goncalves RL, Quinlan CL, Perevoshchikova IV, Hey-Mogensen M & Brand MD Sites of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production by muscle mitochondria assessed ex vivo under conditions mimicking rest and exercise. J. Biol. Chem 290, 209–227 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yun J & Finkel T Mitohormesis. Cell Metab. 19, 757–766 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ristow M & Schmeisser S Extending life span by increasing oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med 51, 327–336 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun N, Youle RJ & Finkel T The mitochondrial basis of aging. Mol. Cell 61, 654–666 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee SS et al. A systematic RNAi screen identifies a critical role for mitochondria in C. elegans longevity. Nat. Genet 33, 40–48 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Durieux J, Wolff S & Dillin A The cell-non-autonomous nature of electron transport chain-mediated longevity. Cell 144, 79–91 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lin YF & Haynes CM Metabolism and the UPRmt. Mol. Cell 61, 677–682 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guarente L Mitochondria—a nexus for aging, calorie restriction, and sirtuins? Cell 132, 171–176 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Verdin E NAD+ in aging, metabolism, and neurodegeneration. Science 350, 1208–1213 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zid BM et al. 4E-BP extends lifespan upon dietary restriction by enhancing mitochondrial activity in Drosophila. Cell 139, 149–160 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hayflick L The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell Res 37, 614–636 (1965). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hayflick L & Moorhead PS The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell Res 25, 585–621 (1961). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Coppé JP et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 6, e301 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper describes the multi-faceted senescence-associated secretory phenotype, its induction by senescence-inducing stimuli and its potential role in driving both degenerative and hyperplastic diseases of ageing.

- 74.Shay JW & Wright WE Hayflick, his limit, and cellular ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 1, 72–76 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.d’Adda di Fagagna F Living on a break: cellular senescence as a DNA-damage response. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 512–522 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rodier F et al. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat. Cell Biol 11, 973–979 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bartkova J et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is part of the tumorigenesis barrier imposed by DNA damage checkpoints. Nature 444, 633–637 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Di Micco R et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is a DNA damage response triggered by DNA hyper-replication. Nature 444, 638–642 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shah PP et al. Lamin B1 depletion in senescent cells triggers large-scale changes in gene expression and the chromatin landscape. Genes Dev. 27, 1787–1799 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wiley CD et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction induces senescence with a distinct secretory phenotype. Cell Metab. 23, 303–314 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Campisi J Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu. Rev. Physiol 75, 685–705 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Childs BG et al. Senescent cells: an emerging target for diseases of ageing. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 16, 718–735 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Baker DJ et al. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature 479, 232–236 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Krizhanovsky V et al. Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell 134, 657–667 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bussian TJ et al. Clearance of senescent glial cells prevents tau-dependent pathology and cognitive decline. Nature 562, 578–582 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chinta SJ et al. Cellular senescence is induced by the environmental neurotoxin paraquat and contributes to neuropathology linked to Parkinson’s disease. Cell Rep. 22, 930–940 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Childs BG et al. Senescent intimal foam cells are deleterious at all stages of atherosclerosis. Science 354, 472–477 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Baker DJ et al. Naturally occurring p16Ink4a-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature 530, 184–189 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Demaria M et al. Cellular senescence promotes adverse effects of chemotherapy and cancer relapse. Cancer Discov. 7, 165–176 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chang J et al. Clearance of senescent cells by ABT263 rejuvenates aged hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Nat. Med 22, 78–83 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ogrodnik M et al. Cellular senescence drives age-dependent hepatic steatosis. Nat. Commun 8, 15691 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schafer MJ et al. Cellular senescence mediates fibrotic pulmonary disease. Nat. Commun 8, 14532 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jeon OH et al. Local clearance of senescent cells attenuates the development of post-traumatic osteoarthritis and creates a pro-regenerative environment. Nat. Med 23, 775–781 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Farr JN et al. Targeting cellular senescence prevents age-related bone loss in mice. Nat. Med 23, 1072–1079 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kirkland JL, Tchkonia T, Zhu Y, Niedernhofer LJ & Robbins PD The clinical potential of senolytic drugs. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 65, 2297–2301 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xu M et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat. Med 24, 1246–1256 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang Y et al. Discovery of piperlongumine as a potential novel lead for the development of senolytic agents. Aging 8, 2915–2926 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg H et al. Identification of HSP90 inhibitors as a novel class of senolytics. Nat. Commun 8, 422 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yosef R et al. Directed elimination of senescent cells by inhibition of BCL-W and BCL-XL. Nat. Commun 7, 11190 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Franceschi C et al. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann. NY Acad. Sci 908, 244–254 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Renz H et al. An exposome perspective: early-life events and immune development in a changing world. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 140, 24–40 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sly PD et al. Health consequences of environmental exposures: causal thinking in global environmental epidemiology. Ann. Glob. Health 82, 3–9 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Floreani A, Leung PSC & Gershwin ME Environmental basis of autoimmunity. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol 50, 287–300 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ferrucci L & Fabbri E Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat. Rev. Cardiol 15, 505–522 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Franceschi C & Campisi J Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J. Gerontol. A 69, S4–S9 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kleinstreuer NC et al. Phenotypic screening of the ToxCast chemical library to classify toxic and therapeutic mechanisms. Nat. Biotechnol 32, 583–591 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Barzilai N, Huffman DM, Muzumdar RH & Bartke A The critical role of metabolic pathways in aging. 61, 1315–1322 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fontana L Neuroendocrine factors in the regulation of inflammation: excessive adiposity and calorie restriction. Exp. Gerontol 44, 41–45 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Franceschi C et al. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech. Ageing Dev 128, 92–105 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Franceschi C, Ostan R & Santoro A Nutrition and inflammation: are centenarians similar to individuals on calorie-restricted diets? Annu. Rev. Nutr 38, 329–356 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pérez VI et al. Protein stability and resistance to oxidative stress are determinants of longevity in the longest-living rodent, the naked mole-rat. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 3059–3064 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Treaster SB et al. Superior proteome stability in the longest lived animal. Age 36, 9597 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kaushik S & Cuervo AM Proteostasis and aging. Nat. Med 21, 1406–1415 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Reis-Rodrigues P et al. Proteomic analysis of age-dependent changes in protein solubility identifies genes that modulate lifespan. Aging Cell 11, 120–127 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.David DC et al. Widespread protein aggregation as an inherent part of aging in C. elegans. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000450 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Klaips CL,Jayaraj GG & Hartl FU Pathways of cellular proteostasis in aging and disease. J. Cell Biol 217, 51–63 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Fabbri E et al. Aging and multimorbidity: new tasks, priorities, and frontiers for integrated gerontological and clinical research. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc 16, 640–647 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kane AE & Sinclair DA Sirtuins and NAD+ in the development and treatment of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. Circ. Res 123, 868–885 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.St Sauver JL et al. Risk of developing multimorbidity across all ages in an historical cohort study: differences by sex and ethnicity. BMJ Open 5, e006413 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kaplan-Lewis E, Aberg JA & Lee M Aging with HIV in the ART era. Semin. Diagn. Pathol 34, 384–397 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Brown RT et al. Geriatric conditions in a population-based sample of older homeless adults. Gerontologist 57, 757–766 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Olshansky SJ, Carnes BA & Cassel C In search of Methuselah: estimating the upper limits to human longevity. Science 250, 634–640 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ismail K et al. Compression of morbidity is observed across cohorts with exceptional longevity. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 64, 1583–1591 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 60, E1–E25 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Steinman MA Polypharmacy—time to get beyond numbers. JAMA Intern. Med 176, 482–483 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Fried LP et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A 56, M146–M157 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO & Rockwood K Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 381, 752–762 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lai JC et al. Development of a novel frailty index to predict mortality in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology 66, 564–574 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kim SW et al. Multidimensional frailty score for the prediction of postoperative mortality risk. JAMA Surg. 149, 633–640 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Wallace LMK et al. Investigation of frailty as a moderator of the relationship between neuropathology and dementia in Alzheimer’s disease: a cross-sectional analysis of data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Lancet Neurol. 18, 177–184 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Liao CY, Rikke BA, Johnson TE, Diaz V & Nelson JF Genetic variation in the murine lifespan response to dietary restriction: from life extension to life shortening. Aging Cell 9, 92–95 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wilson KA, Nelson CS, Beck JN, Brem RB & Kapahi P Genome-wide analysis reveals distinct genetic mechanisms of diet-dependent lifespan and healthspan in D. melanogaster. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/153791v2 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 133.Shinohara M et al. APOE2 eases cognitive decline during aging: clinical and preclinical evaluations. Ann. Neurol 79, 758–774 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Garatachea N et al. ApoE gene and exceptional longevity: insights from three independent cohorts. Exp. Gerontol 53, 16–23 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Partridge L, Deelen J & Slagboom PE Facing up to the global challenges of ageing. Nature 561, 45–56 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.TenNapel MJ et al. SIRT6 minor allele genotype is associated with >5-year decrease in lifespan in an aged cohort. PLoS ONE 9, e115616 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Harper JM, Leathers CW & Austad SN Does caloric restriction extend life in wild mice? Aging Cell 5, 441–449 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Swindell WR Dietary restriction in rats and mice: a meta-analysis and review of the evidence for genotype-dependent effects on lifespan. Ageing Res. Rev 11, 254–270 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Mattison JA et al. Impact of caloric restriction on health and survival in rhesus monkeys from the NIA study. Nature 489, 318–321 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Olson MV Human genetic individuality. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet 13, 1–27 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Lucanic M et al. Impact of genetic background and experimental reproducibility on identifying chemical compounds with robust longevity effects. Nat. Commun 8, 14256 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Richardson A et al. Measures of healthspan as indices of aging in mice—a recommendation. J. Gerontol. A 71, 427–430 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Fischer KE et al. A cross-sectional study of male and female C57BL/6Nia mice suggests lifespan and healthspan are not necessarily correlated. Aging 8, 2370–2391 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Pincus Z, Smith-Vikos T & Slack FJ MicroRNA predictors of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002306 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Zhang WB et al. Extended twilight among isogenic C. elegans causes a disproportionate scaling between lifespan and health. Cell Syst. 3, 333–345 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Bansal A, Zhu LJ, Yen K & Tissenbaum HA Uncoupling lifespan and healthspan in Caenorhabditis elegans longevity mutants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E277–E286 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Nadon NL, Strong R, Miller RA & Harrison DE NIA interventions testing program: investigating putative aging intervention agents in a genetically heterogeneous mouse model. EBioMedicine 21, 3–4 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Zaseck LW, Miller RA & Brooks SV Rapamycin attenuates age-associated changes in tibialis anterior tendon viscoelastic properties. J. Gerontol. A 71, 858–865 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Flynn JM et al. Late-life rapamycin treatment reverses age-related heart dysfunction. Aging Cell 12, 851–862 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Lin AL et al. Chronic rapamycin restores brain vascular integrity and function through NO synthase activation and improves memory in symptomatic mice modeling Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 33, 1412–1421 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Martin-Montalvo A et al. Metformin improves healthspan and lifespan in mice. Nat. Commun 4, 2192 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Mercken EM et al. SRT2104 extends survival of male mice on a standard diet and preserves bone and muscle mass. Aging Cell 13, 787–796 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Mitchell SJ et al. The SIRT1 activator SRT1720 extends lifespan and improves health of mice fed a standard diet. Cell Rep. 6, 836–843 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Justice J et al. Frameworks for proof-of-concept clinical trials of interventions that target fundamental aging processes. J. Gerontol. A 71, 1415–1423 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Consensus report from the multidisciplinary Geroscience Network describing clinical trial designs to test novel ageing interventions.

- 155.Makary MA et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J. Am. Coll. Surg 210, 901–908 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Studenski S et al. Gait speed and survival in older adults. J. Am. Med. Assoc 305, 50–58 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Melis R, Marengoni A, Angleman S & Fratiglioni L Incidence and predictors of multimorbidity in the elderly: a population-based longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 9, e103120 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Barzilai N, Crandall JP, Kritchevsky SB & Espeland MA Metformin as a tool to target aging. Cell Metab. 23, 1060–1065 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Bannister CA et al. Can people with type 2 diabetes live longer than those without? A comparison of mortality in people initiated with metformin or sulphonylurea monotherapy and matched, non-diabetic controls. Diabetes Obes. Metab 16, 1165–1173 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]