Abstract

Purpose:

Recruitment of participants from diverse backgrounds is crucial to the generalizability of genetic research, but has proven challenging. We retrospectively evaluated recruitment methods used for a study on return of genetic results.

Methods:

The costs of study design, development and participant enrollment were calculated, and the characteristics of the participants enrolled through the seven recruitment methods were examined.

Results:

A total of 1118 participants provided consent, a blood sample and questionnaire data. The estimated cost across recruitment methods ranged from $579 to $1666 per participant and required a large recruitment team. Recruitment methods using flyers and staff networks were the most cost-efficient and resulted in the highest completion rate. Targeted sampling that emphasized the importance of Latino/a participation, translated materials, and in-person recruitments contributed to enrolling a demographically diverse sample.

Conclusions

Although all methods were deployed in the same hospital or neighborhood and shared the same staff, each recruitment method was different in terms of cost and characteristics of the enrolled participants, suggesting the importance of carefully choosing the recruitment methods based on the desired composition of the final study sample. This analysis provides information about the effectiveness and cost of different methods to recruit adults for genetic research.

INTRODUCTION

Precision medicine holds many promises, including the implementation of genomic medicine for all.1 Like genetic risk factors which vary based on ancestry, concerns and expectations about genomic medicine may also differ based on individuals’ characteristics such as ethnicity, education, religion or culture.2 Therefore, enrollment of cohorts reflecting the heterogeneity of the United States’ population is crucial to ensure the wide applicability of research findings.

As enrollment inclusiveness is a problem across medical research, multiple recruitment methods have been tested, including targeted recruitment of minorities, recruitment in healthcare facilities serving under-represented communities, engagement of community leaders, and incentives.3-9 To overcome the historic disparities in participation in medical research, some strategies have also focused on educating prospective participants about the value of research, increasing communication and engagement with participants throughout the course of the study, and employing ethnically diverse and stable research teams.3,7,13

Enrolling minorities in genomic research has been reported to be especially challenging, in part due to concerns and mistrust regarding the use of DNA and genetic information.2,14,15 Banked samples from participants enrolled in prior studies are therefore often used as they provide a cost efficient option.12,16 However, depending on the scope of the original study, including the ability to re-contact participants or return research results, these cohorts may not help address questions important for the introduction of genomic medicine for all.17 Overall, genomic studies have reported variable success in enrolling diverse participants in terms of gender, age, race, ethnicity, health status, and education, with most reporting mainly on white, non-Latino individuals from high socioeconomic groups often with prior exposure to genetics or high health literacy.15,18-24 It is thus unknown whether the concerns and expectations of those participating in genetic studies differ from those who do not, and consequently whether the factors and considerations reported to influence use of genetic testing adequately reflect those that operate in the general population. If researchers cannot engage all stakeholders in genomic research, findings based on a homogeneous group of early-adopters of genomic technologies may mislead future decisions regarding the implementation of genomic medicine.

The eMERGE Network is a national consortium focused on integrating genomics with the electronic health record (EHR).25 For the Columbia eMERGE site, we developed a protocol to enroll adult participants for genetic screening of adult-onset conditions with available treatment or preventive interventions. Both positive and negative results were returned to all participants and placed in their EHR. We strove to enroll a sample with greater diversity in ethnicity, age and socioeconomic status than cohorts previously enrolled in genetic research.15,18-24

Currently, there is a scarcity of research literature on the cost and effectiveness of different methods for recruiting a diverse study sample for genetic research, so we began to address this gap by retrospectively examining data we had on the seven recruitment methods we employed at our single site within eMERGE. These data, although not prospectively collected as part of a study on recruitment strategies, contained information relevant to four outcomes: (1)consent rate, (2)completion rate for all components of the first phase of the study, (3)diversity among participants with respect to age, gender, race and ethnicity, education, and employment, and (4)estimated average cost per participant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Columbia Study Design

The Columbia University Medical Center is located in upper Manhattan, a socioeconomically disadvantaged area of New York City, that serves both the local community and individuals travelling to the hospital for specialized care. We developed seven recruitment methods to enroll 1475 participants for free preventative genetic screening; enrollment had to be completed over a 13 month period (Supplementary Methods; Table 1). As one important identified barrier to enrollment of minorities or individuals of low socioeconomic status is convenience,3,7 we developed a participant web-portal, accessible after invitation, to allow self-guided genetic education and electronic study consent at any time. To accomplish one of the eMERGE consortium’s goals of having the ability to interpret genetic data across ancestry, 26 we included a targeted study arm restricted to individuals who self-identified as Latino/a and/or Ashkenazi Jewish, and a general arm for participants of any ancestry. We originally aimed to enroll 475 participants into the targeted arm and 1000 participants of any ancestry into the general arm. Both arms of the study were approved by Columbia University institutional review board.

Table 1:

Description of the seven recruitment methods

| Method | EHR | Flyers- Targeted | Community Events |

Clinic | Biobank | Staff Network | Flyers- General |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deployment period | 6/2016-4/2017 | 7/2016-7/2017 | 4 Events: 8/2016, 12/2016, 4/2017, 5/2017 | 11/2016 - 7/2017 | 11/2016-7/2017 | 1/2017-7/2017 | 1/2017-7/2017 |

| Sampling type | Targeted | Targeted | Targeted | General | Targeted | General | General |

| Invitation type | Active | Passive | Active invitation of a group | Active | Active | Active | Passive |

| Sample frame | CUMC Patients | CUMC Community (Patients, Employees and Students) | Washington Heights and Yeshiva University communities attending genetic education events | CUMC Patients of nephrology, hepatology, and oncology subspecialty outpatient clinics | Participants in a Washington Heights (Latino community) breast cancer biobank | CUMC Community (Family and friends of study staff) | CUMC Community (Patients, Employees and Students) |

| Electronic consent option | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Last step to complete enrollment (CBQ) | Blood draw | Blood draw | Blood draw | Questionnaire | Blood draw | Questionnaire | Questionnaire |

| Maximum number of attempted contacts | Up to 9 (letter, 2 phone calls, 6 reminders) | Up to 7 (flyer, 6 reminders) | Up to 7 (event, 6 reminders) | Up to 4 (invitation, 3 reminders) | Up to 9 (letter, 2 phone calls, 6 reminders) | Unknown | Up to 4 (flyer, 3 reminders) |

Abbreviations: consented, provided blood and completed the questionnaire (CBQ), electronic health records (EHR), Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC).

For sampling type, “Targeted” refers to the eligibility restricted to individuals self-identified as Ashkenazi Jewish and/or Latino/a; and “General” that there were no race or ethnicity eligibility criteria; “Maximum number of attempted contacts” refers to all attempted contacts to encourage potential participants and consented participants to complete blood and questionnaire (not counting potential viewing of the flyers across all recruitment types, supplementary methods)

Eligibility

Individuals 18 and older, able to speak and read English or Spanish, and to provide informed consent, were eligible to participate. All recruitment and patient educational materials, including the web-portal, were available to potential participants in both English and Spanish and were modified to be culturally appropriate for Latino/as, under the guidance of the Community Engagement Core Resource of the Columbia University Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research.

Recruitment Workforce

Participant recruitment and follow-up were conducted by eight clinical research coordinators and four research assistants. Both research coordinators and research assistants invited participants and explained the study, but they also had different roles and salaries: research coordinators obtained written consent and drew blood samples, while research assistants directed participants who verbally expressed interest in the study to the web-portal or mailed them written educational materials and consent forms, and scheduled blood draws. The research coordinators and research assistants were from diverse backgrounds including Latina, Jewish, Asian and European ancestry, and some were Spanish-speaking (Supplementary Methods).

Recruitment Methods

The seven methods differed in sampling type, sample arm, invitation method, deployment period and number of attempted contacts per potential participants (Table 1). In the general arm, blood collection occurred at the consent visit and a questionnaire was mailed or emailed, according to participant’s preference (Figure S1). In the targeted arm, following verbal interest, participants were mailed a paper consent and questionnaire or could chose to complete the consent and questionnaire via the web-portal. Following consent, blood collection was scheduled at multiple locations and times, including early, late and weekend hours.

The methods were deployed in a stepwise manner (Figure S2). They were characterized as either active or passive invitations on the part of the researcher. In the former case, potential participants were invited to the study in-person or by phone, while in the latter case they were made aware of the study through flyers. Active invitations and targeted recruitment were employed first. Two additional methods were subsequently deployed when the number enrolled by the first five methods indicated that, based on the study team capacity, the desired total sample size might not be attained within the study time frame.

A full description of the methods is provided in the Supplementary Methods and Figure S1. Each is succinctly described here in order of deployment.

Targeted active invitation of individuals identified through the EHR: A letter in English and Spanish was sent to patients identified through an EHR query of patients living in zip codes with a high proportion of Latino/a and/or Ashkenazi Jewish individuals (Appendix 1). Research assistants followed-up with phone calls to invite them to participate and to obtain verbal agreement to receive the study materials.

Targeted passive invitation through flyers: Two different formats of flyers were posted at Columbia University Medical Center, in both English and Spanish: one describing eligibility for people of Latino/a and/or Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry and one specifically encouraging people of Latino/a ancestry to enroll (Figure S3). Interested individuals contacted the research assistants to learn about enrollment procedures.

Targeted active invitation of attendees at genetic educational events in the community: Community organizers hosted events at which the study was described and attendees were invited to participate. Interested attendees shared their contact information and were later contacted by a research assistant.

General active invitation of patients in medical clinics: All patients seen in participating outpatient clinics were screened for eligibility. Patients approved by their provider were invited in-person immediately after their clinic appointment.

Targeted active invitation of prior research participants from the breast cancer biobank (biobank): Biobank participants were sent an invitation letter in English and Spanish (Appendix 1). Research assistants followed-up with phone calls to invite them to the study and obtain verbal agreement to receive the study materials.

General active invitation of staff network: Study staff invited their friends, family members and colleagues to the study. Interested individuals were given information on how to contact the study team to schedule an enrollment visit.

General passive invitation through flyers: Flyers in English were posted at around Columbia University Medical Center (Figure S3). Interested individuals contacted the research coordinators to learn about enrollment procedures.

Consent Rate and Decliners

Only a subset of the recruitment methods (EHR, Clinics, Biobank and Community events) enabled the calculation of consent and decline rates. The consent rates for the clinics, EHR and biobank methods were calculated as the proportion of participants who consented to the study out of those invited and eligible. For the community events, the total number of attendees was counted as invited and eligible participants, even though probably not all were eligible. For all methods, if a potential participant declined the study, they were not approached again, though they may have seen the flyers afterwards. Reasons for declining were solicited for clinics, EHR and Biobank with a multiple-choice question (Supplementary Methods).

Enrollment completion

Even though all participants who provided a blood sample received free genetic screening, for the purpose of this report, participants were considered to have completed enrollment only after they gave written consent, provided a blood sample, and answered a questionnaire (CBQ participants; Supplementary Methods). A $25 gift card incentive was offered for questionnaire completion. In the general arm, up to three follow-up attempts were made to remind participants to complete the questionnaire (Table 1, Figure S1). In the targeted arm, methods included up to three follow-up attempts after verbal interest in participating was expressed to remind potential participants to complete consent and questionnaire and up to three follow-up attempts after the written consent to schedule the blood draw. CBQ completion rates were calculated as the proportion of individuals who completed enrollment (CBQ participants) out of those who consented to the study (Supplementary Methods).

Cost Analysis

A full description of the cost analysis can be found in the Supplementary Methods. In short, study start-up costs (fixed costs), recruitment cost per CBQ participant (marginal cost) and supply costs per CBQ participant were retrospectively estimated. The fixed cost was based on an estimate of the time each of the contributing researchers spent developing the study materials and their salaries, as well as outsourced work costs. The marginal cost was based on the estimated time spent on recruitment by each method, and the estimated percent efforts of each staff member (full-time equivalent, FTE). The supply costs were calculated for each method separately. Extrapolated recruitment numbers for each method per one FTE were estimated.

Participant Demographics

Demographic information, including age, gender, race, ethnicity, address, employment status, and education level, was collected at the time of informed consent or through the study questionnaire (Appendix 2, Supplementary Methods). Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry information was collected only for the targeted arm. Socio-economic background was evaluated using three variables: education level, employment status and geo-income as income was not collected from the participants.27

Evaluation of the Recruitment Methods

Using the full CBQ sample characteristics as a reference, we evaluated how each method contributed to the CBQ sample. The participants’ characteristics and the cost per CBQ participant were summarized for each method.

Statistical Analysis

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Columbia University.32 Results are presented as Ns and frequencies. Chi square and Fisher’s Exact test analyses were used to explore the differences between participants who did and did not complete CBQ. Analysis was completed in SAS28 and R.29

RESULTS

Study and Recruitment Costs

The development of the study materials required an estimated 3,600 hours of work by 24 people, including faculty and staff, for a fixed cost of approximately $408,665 (Supplementary Results, Table S1). Of the total time devoted to study development, 30% was dedicated to web-portal development, 18% to questionnaire development, 17% to study design, 17% to materials’ translation, and the remaining 18% were used for eight additional tasks. More training time was invested in the research coordinators than in the research assistants (120 hours versus 40 hours, respectively; Table S1a).

The length of time the recruitment methods were deployed varied from 4 to 12 months (Figure S2). Recruitment efforts involved 16 people, including research coordinators, research assistants, research scientists, a bioinformatician and a genetic counselor, which totaled 3.8 FTE employees, corresponding to an estimated marginal cost of $430,663 (Table S2). Due to the different protocols and their stepwise deployment, the number of FTEs invested in the study varied, with over a third of the study staff deployed in clinics (1.4 FTEs; Table S3). The extrapolated estimated number of CBQ participants per one FTE ranged between 91 participants/FTE for the EHR method to over 630 participants/FTE for the general flyer (Figure 1a).

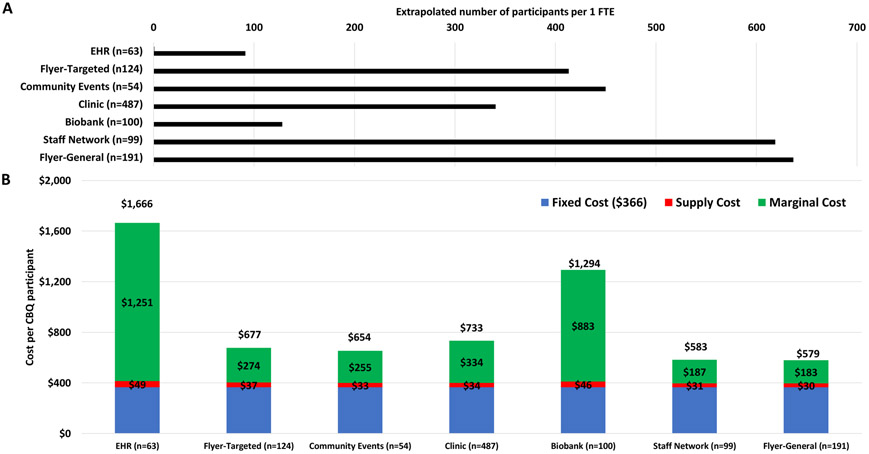

Figure 1.

Variable costs across seven recruitment methods

A. Extrapolated number of participants who completed enrollment per one FTE for each recruitment method (assuming the same average number of CBQ participants over 12 months).

Abbreviations: consent blood and questionnaire complete (CBQ), electronic health records (EHR), full time equivalent (FTE).

B. Average cost including fixed start-up cost, supply cost and marginal cost, per CBQ participant for each recruitment method.

Depending on the method, the estimated cost per CBQ participant ranged from $579-$1666 (Figure 1b). For most methods, at least 50% of the cost originated from the fixed cost ($366/participant). Despite the $25 gift cards, the supply costs accounted for only a minority of the expenses ($31-49 per CBQ participant, Table S4). The high FTE investment in the clinics enabled the recruitment of a high number of participants. The estimated cost per consented participant who provided a blood sample regardless of questionnaire completion was similar for the clinics, staff network and general flyers ($205, $173 and $173, respectively, Table S4).

Variable Consent, Decline and Completion Rates

Across all methods, a total of 1603 participants consented to the study, of whom 1118 were CBQ participants, 355 provided blood only and 130 completed the questionnaire only (Table S5). We observed a wide range of consent rates (22-87%), with the highest rate among those invited in-person in the clinics (Figure 2, Table S6). Furthermore, when examining all 4429 individuals who were sent invitation letters (EHR, Biobank), regardless of whether they were reached by phone, fewer than 6% consented (Supplementary Results). Twenty-five consented participants who were enrolled through the clinics, targeted flyers, general flyers, and staff network (17, 4, 3 and 1, respectively) were also sent an invitation letter through the EHR or the biobank methods, but it is unknown whether they received and read it.

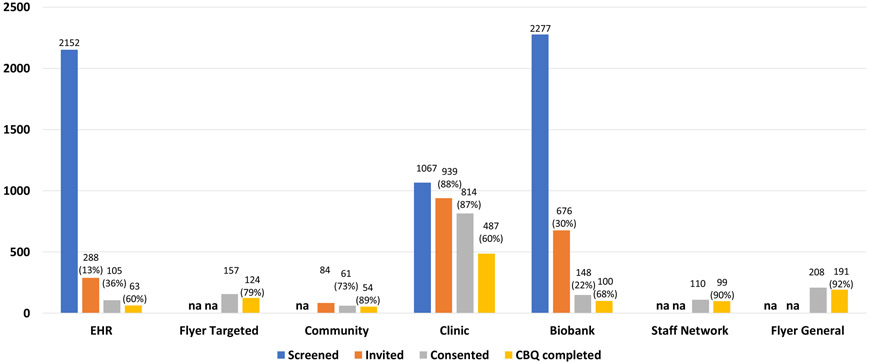

Figure 2.

Number of participants screened, invited, consented, who provided a blood sample and completed a questionnaire (CBQ) by each recruitment method. Only eligible individuals were invited, and for the EHR and Biobank only individuals who answered the phone call were counted as invited.

Abbreviations: not available for certain methods (na), electronic health records (EHR), individuals who provided written consent, blood and completed the questionnaire (CBQ completed)

Of the 517/909 decliners who provided a reason, a common reason in all three methods was “lack of interest” (n=183) and for the EHR and biobank it was “time constraints”, which was not a reason offered to the decliners in the clinics (n=143; Figure S4). Only 37 decliners cited concerns about privacy or discrimination, and 21 additional decliners indicated they did not want to learn their genetic results.

Enrollment rates varied over time and across methods (Figure S2). For some of the methods still being used at the time we reached our enrollment goal, we had not yet observed any decline in the number of participants being enrolled. We observed a peak of recruitment approximately a month after sending the invitation letters or holding the community events. The clinics’ enrollment required a period of familiarizing the health care team with the study during which recruitment was slow, but thereafter the recruitment was stable until the end of the study period. There were two peaks for the staff network enrollment, the first one soon after the method was deployed and the second close to the end of the study. Enrollment through the flyers began immediately after posting and appeared to be associated with number of flyers posted.

The CBQ completion rates varied across recruitment methods (60%−92%, Figure 2, Table S5). Because the order of completion differed between the general and the targeted arms (Figure S1), the CBQ completion rates were analyzed separately for each arm. In the general arm, of the 1132 participants who provided a blood sample at time of consent, only 777 also completed the questionnaire. The proportions of consented participants who did and did not complete the questionnaire across methods was significantly different (p-value=1.90E−23). Among the 471 in the targeted arm who completed the questionnaire at time of consent, only 341 provided a blood sample. Similarly, the proportions of consented participants who did and did not provide a blood sample across methods was significantly different (p-value=7.19E−05). Though the sample size goal was almost reached (1473 participants provided a blood sample), the CBQ sample consisted of only 1118 participants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographics of the 1118 participants who provided written consent and blood samples and completed the questionnaire (CBQ participants). Number and percentage of the total study sample.

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1118 | ||

| Gender | Male | 404 | 36.1% |

| Age | 18-24 | 109 | 9.7% |

| 25-44 | 410 | 36.7% | |

| 45-64 | 363 | 32.5% | |

| 65+ | 235 | 21.0% | |

| Race and Ethnicity | White, non-Latino/a | 513 | 45.9% |

| Black/African American, non-Latino/a | 70 | 6.3% | |

| Asian, non-Latino/a | 118 | 10.6% | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native, Non-Latino/a | 1 | 0.1% | |

| More than one race, Non-Latino/a | 12 | 1.1% | |

| Other, Non-Latino/a | 8 | 0.7% | |

| White, Latino/a | 118 | 10.6% | |

| Black/African American, Latino/a | 26 | 2.3% | |

| Asian, Latino/a | 4 | 0.4% | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native, Latino/a | 5 | 0.4% | |

| More than one Race, Latino/a | 64 | 5.7% | |

| Other, Latino/a | 179 | 16.0% | |

| Not born in the United States | 442 | 40% | |

| Education | Less than high school | 85 | 7.6% |

| High school or GED | 110 | 9.8% | |

| College some or degree | 550 | 49.2% | |

| Graduate some or degree | 370 | 33.1% | |

| NR | 3 | 0.3% | |

| Employment | Employed, full or part time | 670 | 59.9% |

| Unemployed | 45 | 4.0% | |

| Disabled, temporary or permanent | 88 | 7.9% | |

| Retired | 174 | 15.6% | |

| Student/ Other | 134 | 12.0% | |

| NR | 7 | 0.6% | |

| Geo-income | <$33,948 | 176 | 15.7% |

| 33,948-100,000 | 632 | 56.5% | |

| $100,000+ | 284 | 25.4% | |

| NA | 26 | 2.3% | |

| Questionnaire Format | English online | 881 | 78.8% |

| English on paper | 99 | 8.9% | |

| Spanish online | 19 | 1.7% | |

| Spanish on paper | 119 | 10.6% | |

| Recruitment modality | EHR | 63 | 5.6% |

| Flyers- Targeted | 124 | 11.1% | |

| Community Events | 54 | 4.8% | |

| Clinic | 487 | 43.6% | |

| Biobank | 100 | 8.9% | |

| Staff Network | 99 | 8.9% | |

| Flyers- General | 191 | 17.1% | |

Abbreviations: general equivalency degree (GED), , electronic health records (EHR), not reported (NR), not applicable (NA)

Different Demographic Distribution

The age range of the CBQ sample was 18-94 years-old, with 10% percent of the participants younger than 25 years-old, 21% older than 65 years-old, and the remainder evenly distributed in 10-year intervals between 25 and 65 years-old (Table 2). Though none of the methods was designed to recruit a specific age group, a higher proportion of individuals younger than 44 years were enrolled through the community, staff network, targeted and general flyers than through the other methods (Table S6, Figure S5).

A high proportion of women, who represented two-thirds of the CBQ sample (Table. 2), were recruited through the flyers (targeted and general), staff network, EHR, and, of course, the biobank (which almost exclusively invited women; Table S6, Figure S5). Only the clinics and the community events recruited male and female participants almost equally.

The CBQ sample was diverse in terms of ancestry. Fewer than half self-identified as white, non-Latino/a and 35% self-identified as Latino/a (Table 2). Highlighting the utility of the Spanish translation and the ability to complete the study offline, 30% of the Latino/a participants completed study materials in Spanish and on paper. Consistent with the targeted enrollment, 44% participants of this arm self-identified as Ashkenazi Jewish, including 9 participants who self-identified as both Latino/a and Ashkenazi Jewish. Similarly, the targeted flyer and the biobank enrolled the highest proportions of participants who self-identified as Latino/a (76% and 69%, respectively; Table S6, Figure S6).

Different Socio-Economic Backgrounds

In terms of socio-economic background, 18% of the CBQ sample had a high school education or less, 8% reported a disability preventing them from working, and 16% lived in a neighborhood with a low average annual household income (Table 2). The targeted flyers and the biobank methods resulted in the highest proportion of participants living in low income areas (26% and 31%, respectively; Table S6, Figure S6). The EHR and the staff network methods recruited the highest proportion of participants with graduate degrees (54% and 56%, respectively).

Effectiveness and cost evaluation of the seven recruitment methods

No two methods had the same combination of participants’ characteristics, CBQ completion rate and recruitment cost (Table 3, Figure S5 and Figure S6). CBQ completion rates were higher and recruitment costs were lower for methods resulting in a sample with comparatively higher education levels and employment rates, and lower ethnic diversity (Table S6). More expensive methods, enrolled a sample with comparatively lower education levels and employment rates, and greater ethnic diversity.

Table 3.

CBQ sample: recruitment effectiveness, participants’ characteristics, and cost per CBQ participant for all methods combined.

| Full CBQ Sample |

EHR | Flyer- Targeted |

Community Events |

Clinic | Biobank | Staff Network |

Flyer- General |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invitation | Type | Active | Passive | Active invitation of a group | Active | Active | Active invitation of network | Passive | ||

| Recruitment effectiveness | N | 1118 | 63 | 124 | 54 | 487 | 100 | 99 | 191 | |

| Consent Rate | 56% | 36% | na | 73% | 88% | 22% | na | na | ||

| CBQ Rate | 70% | 60% | 79% | 89% | 60% | 68% | 90% | 92% | ||

| Participants characteristics | Age | <45y old | 47% | − | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| >65y old | 21% | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | ||

| Gender | male | 36% | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | |

| Race and Ethnicity | Latino/a | 35% | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | |

| not White non-Latino/a | 46% | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | ||

| Education | High school or less | 18% | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | |

| Employment | not employed | 40% | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | |

| Geo-Income | <$33,948 | 16% | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

| Cost (marginal and start-up) | $787 | $1,669 | $676 | $656 | $733 | $1,295 | $582 | $578 |

Abbreviations: consented, provided blood and completed the questionnaire (CBQ), electronic health records (EHR), not available (na)

Dark grey (+): higher consent or CBQ rate, more diverse cohort and lower cost per CBQ participant for the recruitment method compared to the full CBQ Sample.

White (−): lower consent or CBQ rate, less diverse cohort and higher cost per CBQ participant for the recruitment method compared to the full CBQ Sample.

DISCUSSION

Evaluation of seven recruitment methods for a genomic screening study revealed that each method differently contributed to the enrollment of a sample more demographically diverse than samples of previous studies offering genetic testing.15,18-24 While the retrospective nature of this assessment and the variability across the methods was a limitation and prevented a systematic comparative effectiveness analysis, we think this report of our experience with different recruitment methods for a genetic study may aid in the design of future studies.

Multiple barriers have been discussed as limiting recruitment of diverse samples, and several approaches have been developed to address them.10,12,14,30,31 The approaches implemented in this study included employment of a diverse and bilingual, stable study staff, online and offline bilingual study materials, diversified recruitment methods and incentives. The clinics, which had a high consent rate of a relatively diverse sample, were convenient for participants and provided in-person recruitment by a demographically diverse staff, all factors shown to increase enrollment and help foster trust among prospective participants.2,4,7,10,32 Utilizing additional approaches reported to be important in recruitment and retention of minority groups5-7,9 – targeted recruitment emphasizing the importance of Latino/a participation, bilingual study staff and study materials allowing participation in Spanish – likely contributed to the successful enrollment of a high proportion of Latino/as. Finally, the option for offline completion of the study, which was used by the majority of participants who completed the study in Spanish, may have also contributed to our sample’s ethnic diversity. The study design did not allow us to isolate the importance of each of these approaches. It is also unknown whether those approaches would provide effective enrollment of other underrepresented populations. Future studies should evaluate the cost and effectiveness of different recruitment strategies with other populations and of additional recruitment strategies, such as the use of social media.

The reported costs are only estimates as they were retrospectively calculated. Nevertheless, consistent with prior reports, the methods differed in cost, largely related to the number of attempted contacts when the active invitation was not in-person.4,12 In contrast to previous reports suggesting that bio-banked samples are cost-effective,12 the need in this case to recontact participants and obtain an additional blood draw and consent resulted in this approach being one of the most expensive.

The high start-up cost supports re-using protocols and materials. Compilation of genomic medicine education, recruitment materials and enrollment protocols into a central toolkit available to all researchers could leverage prior experience, minimize future study start-up costs, lead to their continuous improvement, and ultimately introduction to clinical care.

Since previous reports have described concerns about privacy and discrimination as being potential barriers to participation in genetic research,33-35 we were apprehensive about how placement of genetic results in the EHR might impact recruitment. Interestingly, few potential participants declined when invited in-person, possibly because they had a trusting relationship with the medical team, and few of them reported privacy or discrimination concerns. While this may be a function of the method (i.e. face-to-face recruitment), it may also reflect a shift in attitudes or the differences between this sample and those previously reported.

The EHR approach, though targeted to specific zip codes and individuals of specific ancestry, was the method most similar to recruitment of the general population. Its low consent rate may be attributable to limited awareness of or interest in genetic and medical research.33,36,37 Public education may be helpful across all recruitment strategies and may facilitate the implementation of genomic medicine. Future studies should systematically assess awareness of or interest in genetics and reasons for declining study participation and how enrollment rates differ by demographics characteristics.

This analysis has several limitations, including the utilization of data from a study that was not designed to assess recruitment cost and efficiency. Self-selection bias, is a common problem in studies, especially those that rely on passive recruitment methods as we did in the majority of our strategies. Because we could not know who was made aware of the opportunity to participate (e.g., saw a flyer) or their characteristics, we are unable to assess the nature of the self-selection bias this introduced. For instance, it was not possible to calculate what proportion of those who viewed the flyer went on to enroll. Other limitations precluded drawing firm conclusion about the relative effectiveness of different recruitment methods. For example, some methods were deployed longer, others had more follow-up attempts. Future prospective, randomized studies implementing different recruitment methods on defined populations, with a uniform workforce, identical timelines and eligibility would provide more rigorous assessment of recruitment methods.

Because the available data on the effectiveness of different recruitment strategies for genomic research studies and their associated costs is sparse, we conducted a retrospective analysis of our recruitment data. The study limitations and biases may limit the generalizability of our findings to other clinical settings, geographic regions of the country, or studies with other aims. However, much of our experience is likely transferable to recruitment for other genomic studies.38,39 We hope our observations will provide information that stimulates thinking about the importance of diverse recruitment options, helps to improve efficiency and effectiveness, and ultimately contributes to recruitment of samples that better reflect the heterogeneity of the US population.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: Recruitment steps for each method.

Each row represents one of the seven recruitment methods. Left to Right: The month and year at which the method was deployed. The methods either enrolled the general population (”General”) or targeted Ashkenazi Jewish and/or Latino/a individuals (“Targeted”). The method of invitation and the steps to complete the study. The legend for the cartoons appears on the bottom of the figure.

Figure S2: Number of CBQ participants consented over time stratified by recruitment method.

The months represent the time when the participant signed the informed consent. July 2017 is not displayed on the graph as recruitment did not take place for the full month.

Figure S3: Study recruitment flyers. The targeted flyers were posted in both English and Spanish

Figure S4: Reasons for declining participation for recruitment methods.

Reasons were solicited by multiple choice questions administered at the time of invitation. Decline rate is the proportion of decliners from all those invited and eligible. The Pie charts represent only those who provided a reason for decline. Only a subset of individuals invited through the EHR or Biobank provided a reason for decline and/or had an opportunity to provide a reason.

Abbreviations: electronic health records (EHR)

Figure S5: Distribution of gender, age and study mode by study recruitment method for the 1118 CBQ participants.

Abbreviations: electronic health records (EHR)

Figure S6: Distribution of race and ethnicity, education level, employment status and geo-income by study recruitment method for the 1118 CBQ participants.

Abbreviations: electronic health records (EHR)

Acknowledgments

Research was funded by U01HG008680 (PIs Weng, Hripcsak, and Gharavi). We would like to thank the participants of this research study. We also thank Evan Joiner, Emily Webster, Andria Reyes, Alejandra Aguirre, Nayrobi Ribera, Katrina Celis, Rachel Yarmolinsky, and Ilana Chilton for their guidance in the development and translation of the educational materials. We thank Ian Halim and Anoushka Sinha and the staff of the nephrology clinics for assistance with recruiting participants.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests:

The authors have no conflict of interests to report.

References

- 1.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Roundtable on Genomics and Precision Health. Implementing and Evaluating Genomic Screening Programs in Health Care Systems: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2018. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK500393/. Accessed December 24, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hindorff LA, Bonham VL, Brody LC, et al. Prioritizing diversity in human genomics research. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19(3):175–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoyo C, Reid ML, Godley PA, Parrish T, Smith L, Gammon M. Barriers and strategies for sustained participation of African-American men in cohort studies. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(4):470–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huynh L, Johns B, Liu S-H, Vedula SS, Li T, Puhan MA. Cost-effectiveness of health research study participant recruitment strategies: a systematic review. Clin Trials. 2014;11(5):576–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez-Owens M, Starkey K, Gil C, Armenta K, Maupomé G. The VidaSana Study: Recruitment Strategies for Longitudinal Assessment of Egocentric Hispanic Immigrant Networks. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholson LM, Schwirian PM, Groner JA. Recruitment and retention strategies in clinical studies with low-income and minority populations: Progress from 2004–2014. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(Pt A):34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George S, Duran N, Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):e16–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UyBico SJ, Pavel S, Gross CP. Recruiting vulnerable populations into research: a systematic review of recruitment interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):852–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown SD, Lee K, Schoffman DE, King AC, Crawley LM, Kiernan M. Minority recruitment into clinical trials: experimental findings and practical implications. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(4):620–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson VA, Powell-Young YM, Torres ER, Spruill IJ. A systematic review of strategies that increase the recruitment and retention of African American adults in genetic and genomic studies. ABNF J. 2011;22(4):84–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skinner HG, Calancie L, Vu MB, et al. Using community-based participatory research principles to develop more understandable recruitment and informed consent documents in genomic research. PloS one. 2015;10(5):e0125466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salowe R, O’Keefe L, Merriam S, et al. Cost and yield considerations when expanding recruitment for genetic studies: the primary open-angle African American glaucoma genetics study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Troost JP, Hawkins J, Jenkins DR, et al. Consent for Genetic Biobanking in a Diverse Multisite CKD Cohort. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(6):1267–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amendola LM, Berg JS, Horowitz CR, et al. The Clinical Sequencing Evidence-Generating Research Consortium: Integrating Genomic Sequencing in Diverse and Medically Underserved Populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;103(3):319–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Popejoy AB, Fullerton SM. Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature. 2016;538(7624):161–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carey DJ, Fetterolf SN, Davis FD, et al. The Geisinger MyCode Community Health Initiative: an electronic health record-linked biobank for Precision Medicine research. Genet Med. 2016;18(9):906–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolf SM, Crock BN, Van Ness B, et al. Managing incidental findings and research results in genomic research involving biobanks and archived data sets. Genet Med. 2012;14(4):361–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dewey FE, Murray MF, Overton JD, et al. Distribution and clinical impact of functional variants in 50,726 whole-exome sequences from the DiscovEHR study. Science. 2016;354(6319). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amendola LM, Dorschner MO, Robertson PD, et al. Actionable exomic incidental findings in 6503 participants: challenges of variant classification. Genome Res. 2015;25(3):305–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henderson G, Garrett J, Bussey-Jones J, Moloney ME, Blumenthal C, Corbie-Smith G. Great expectations: views of genetic research participants regarding current and future genetic studies. Genet Med. 2008;10(3):193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amiri L, Cassidy-Bushrow AE, Dakki H, et al. Patient Characteristics and Participation in a Genetic Study: A Type 2 Diabetes Cohort. J Investig Med. 2014;62(1):26–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Espeland MA, Dotson K, Jaramillo SA, et al. Consent for genetics studies among clinical trial participants: findings from Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD). Clin Trials. 2006;3(5):443–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis KL, Hooker GW, Connors PD, et al. Participant use and communication of findings from exome sequencing: a mixed-methods study. Genet Med. 2016;18(6):577–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanderson SC, Linderman MD, Suckiel SA, et al. Psychological and behavioural impact of returning personal results from whole-genome sequencing: the HealthSeq project. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25(3):280–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Human Genome Research Institute. eMERGE Network. https://emerge.mc.vanderbilt.edu/. Published 2018. Accessed October 10, 2018.

- 26.Zouk H Harmonizing Clinical Sequencing And Interpretation For The eMERGE III Network. BioRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Brokamp C, Wolfe C, Lingren T, Harley J, Ryan P. Decentralized and reproducible geocoding and characterization of community and environmental exposures for multisite studies. J Am Med Inform Assoc. November 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SAS Institute Inc. SAS 9.4 [Computer Program]. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skinner CS, Schildkraut JM, Calingaert B, et al. Factors associated with African Americans’ enrollment in a national cancer genetics registry. Community Genet. 2008;11(4):224–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levy D, Splansky GL, Strand NK, et al. Consent for genetic research in the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152a(5):1250–1256. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De La Rosa M, Babino R, Rosario A, Martinez NV, Aijaz L. Challenges and strategies in recruiting, interviewing, and retaining recent Latino immigrants in substance abuse and HIV epidemiologic studies. Am J Addict. 2012;21(1):11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hann KEJ, Freeman M, Fraser L, et al. Awareness, knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes towards genetic testing for cancer risk among ethnic minority groups: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowstuter KJ, Sand S, Blazer KR, et al. Influence of genetic discrimination perceptions and knowledge on cancer genetics referral practice among clinicians. Genet Med. 2008;10(9):691–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amendola LM, Robinson JO, Hart R, et al. Why Patients Decline Genomic Sequencing Studies: Experiences from the CSER Consortium. J Genet Couns. 2018;27(5):1220–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamilton JG, Shuk E, Arniella G, et al. Genetic Testing Awareness and Attitudes among Latinos: Exploring Shared Perceptions and Gender-Based Differences. Public Health Genomics. 2016;19(1):34–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cobb EM, Singer DC, Davis MM. Public interest in medical research participation: differences by volunteer status and study type. Clin Transl Sci. 2014;7(2):145–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malterud K Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hellström T Transferability and Naturalistic Generalization: New Generalizability Concepts for Social Science or Old Wine in New Bottles? Qual Quant. 2008;42(3):321–337. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Recruitment steps for each method.

Each row represents one of the seven recruitment methods. Left to Right: The month and year at which the method was deployed. The methods either enrolled the general population (”General”) or targeted Ashkenazi Jewish and/or Latino/a individuals (“Targeted”). The method of invitation and the steps to complete the study. The legend for the cartoons appears on the bottom of the figure.

Figure S2: Number of CBQ participants consented over time stratified by recruitment method.

The months represent the time when the participant signed the informed consent. July 2017 is not displayed on the graph as recruitment did not take place for the full month.

Figure S3: Study recruitment flyers. The targeted flyers were posted in both English and Spanish

Figure S4: Reasons for declining participation for recruitment methods.

Reasons were solicited by multiple choice questions administered at the time of invitation. Decline rate is the proportion of decliners from all those invited and eligible. The Pie charts represent only those who provided a reason for decline. Only a subset of individuals invited through the EHR or Biobank provided a reason for decline and/or had an opportunity to provide a reason.

Abbreviations: electronic health records (EHR)

Figure S5: Distribution of gender, age and study mode by study recruitment method for the 1118 CBQ participants.

Abbreviations: electronic health records (EHR)

Figure S6: Distribution of race and ethnicity, education level, employment status and geo-income by study recruitment method for the 1118 CBQ participants.

Abbreviations: electronic health records (EHR)