Abstract

Despite regenerative medicine (RM) being one of the hottest topics in biotechnology for the past 3 decades, it is generally acknowledged that the field’s performance at the bedside has been somewhat disappointing. This may be linked to the novelty of these technologies and their disruptive nature, which has brought an increasing level of complexity to translation. Therefore, we look at how the historical development of the RM field has changed the translational strategy. Specifically, we explore how the pursuit of such novel regenerative therapies has changed the way experts aim to translate their ideas into clinical applications, and then identify areas that need to be corrected or reinforced in order for these therapies to eventually be incorporated into the standard‐of‐care. This is then linked to a discussion of the preclinical and postclinical challenges remaining today, which offer insights that can contribute to the future progression of RM.

In 1954, Dr. Joseph Murray performed the first transplant in a human when he transferred a kidney from one identical twin to another.1 This successful procedure, which would go on to have a profound impact on medical history, was the culmination of > 50 years of transplantation and grafting research. In the following years, organ replacement became more widespread but also led to a plateau in terms of landmark successes.1 The technology was working, but limitations were already being encountered; the most prominent of them being the lack of organ availability and the increasing need from the aging population.2 During the same time period, chronic diseases were on the rise and the associated process of tissue degeneration was becoming evident. Additionally, the available clinical interventions were merely capable of treating symptoms, rather than curing the disease, and, therefore, once a loss of tissue function occurred, it was nearly impossible to regain.3 Overall, the coupling of all these factors that took place in the 1960s and 1970s created urgency for disruptive technologies and led to the creation of tissue engineering (TE).

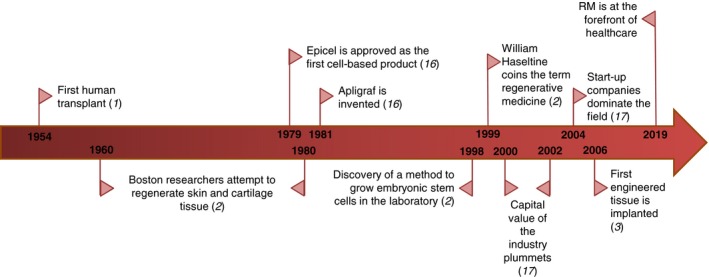

TE can be described as “a field that applies the principles of engineering and life sciences toward the development of biological substitutes that restore, maintain, or improve tissue function or a whole organ.”4 TE is considered to be under the umbrella of regenerative medicine (RM) and, according to Dr. Heather Greenwood et al., “regenerative medicine is an emerging interdisciplinary field of research and clinical applications focused on the repair, replacement or regeneration of cells, tissues or organs to restore impaired function resulting from any cause, including congenital defects, diseases, trauma and aging.”5 It uses a combination of technological approaches that moves it beyond traditional transplantation and replacement therapies. These approaches may include, but are not limited to, the use of soluble molecules, gene therapy, stem cell transplantation, tissue engineering, and the reprogramming of cell and tissue types.3, 6, 7 A summary of the recent history of RM is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A summary timeline of the recent history of regenerative medicine (RM). Selected milestones in the development of RM are presented starting from the 1950s all the way up to the present day.

Although RM may have seemed novel, the principles of regeneration are as old as humanity and are found in its many cultures.8 A common example used is the tale of Prometheus that appeared in 8th century BCE. Prometheus, an immortal Titan in Greek mythology, stole fire and gave it to humanity for them to use, defying the gods in consequence. As punishment, Zeus decreed that he was to be bound to a rock where an eagle would feast on his liver every day and said liver would regenerate itself every night, leading to a continuous loop of torture.9 RM came about at the time it did, not only because of the combining factors mentioned above, but also because researchers had been successfully keeping tissue alive in vitro and understanding the biological processes involved in regeneration and degeneration. Consequently, possible therapeutic outcomes came into fruition. Since the arrival of TE and RM, strides made on the benchside have been ever increasing with now > 280,000 search results on PubMed relating to regeneration. Discoveries and advances made by cell/molecular biologists, engineers, clinicians, and many more led to a paradigm shift from treatment‐based to cure‐based therapies.10 In addition to Greenwood’s definition, RM’s arsenal now contains controlled release matrices, scaffolds, and bioreactors.5, 8 Despite this impressive profile on the benchside, RM has so far underperformed in terms of clinical applications (i.e., poor therapy translation).8 Simply put, a disappointing number of discoveries are making it through clinical trials and onto the market.11 Although some experts say that the field is reaching a critical mass in terms of potential therapies and that we will soon see results, others, like Dr. Harper Jr. from the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, say that “the transformative power of RM is well recognized, but the complexity of translating isn’t.”7, 8, 12

This brings us to the subject matter of the present paper: RM and translation. The goals of this historical review are twofold. The first is to understand how RM, over the past 50 years or so, has changed the way discoveries/new technologies are transferred to the clinic. How has the translational strategy changed in response to these new therapies? The second is to identify challenges that have led to RM’s modest performance on the bedside. Some articles have already documented these but have focused on the clinical and postclinical factors, and whereas they will be briefly discussed here, the focus will be on preclinical factors.13 To accomplish these objectives, we will begin by summarizing the historical development of RM (which has been extensively documented by other works2, 3, 14, 15), followed by a detailed look at the definition of translational medicine (TM). With this background information established, we then look at the various preclinical and clinical impacts of RM on TM, as well as some of its effects on the private sector. Limiting factors of the field are then described, again focusing on those that are preclinical. This endeavor was initiated via a librarian‐assisted literature search for original research and historical documentation of the field of RM and other related subjects. The documents were then screened for relevance and the analyzed information was categorized into the themes discussed below. Conclusions were then drawn based on the interplay among these themes.

The Development of Regenerative Medicine: a Brief History

As mentioned, the idea of regeneration first started in myths and legends. This is logical because, as Drs. Himanshu Kaul and Yiannis Ventikos put it, myths shape ideas, and ideas then shape technologies.8 In addition to the tale of Prometheus, there are many others. For example, there is the Hindu myth of Raktabeej whose blood drops could each form a clone of himself, or the Indian story of the birth of the Kaurava brothers where pieces of flesh were grown in pots and treated with herbs to grow full‐sized humans.8 The idea of regeneration has persisted throughout history and started to become a possibility in the early 1900s when scientists like Alexis Carrel (who invented the technique of cell culture) were finally able to keep cells and tissues alive outside of the body. This allowed them to study the mechanisms of cell renewal, regulation, and repair.8 In addition, studying regeneration goes hand‐in‐hand with developmental biology. Seminal work in experimental embryology began in the 1820s with the detailed description of the differentiation of embryonic germ layers.16 An increased understanding of basic embryological mechanisms led to Hans Spemann’s Nobel Prize for his theory of embryonic induction; a field that was further elaborated by his students and others, advancing it toward the possibility of cloning and demonstrating how development and regeneration are intimately linked.16 Before this era, the study of regeneration was done through the study of animals, with scientists studying the phenomena in serpents, snails, and crustaceans, for example.17, 18 However, the modern study of regeneration is said to have started with Abraham Trembley’s study of the hydra, which showed that it was possible for an entire organism to regenerate from its cut appendage.19 The 18th century on through to the 19th century is also when scientists became intrigued by the amphibian newts and axolotls for their astonishing regenerative capabilities, which are still used today as the gold standard models for studying regeneration along with certain fish, such as the zebrafish.20

Now, although the term RM as we know it today would only be coined in 1999 by William Haseltine, the field itself started in the late 1970s in the form of TE (pioneered by Drs. Joseph Vacanti and Robert Langer) in the city of Boston.2, 14, 21 To address the need for novel therapies, biomedical engineers, material scientists, and biologists at Harvard and MIT started working on regenerating parts of the largest and simplest organ of the human body: the skin. In 1979, the first cell‐based TE product appeared and was named Epicel.15 Developed by Dr. Howard Green et al., this technology consisted of isolating keratinocytes from a skin biopsy and having them proliferate outside of the body to make cell “sheets” that were then used as an autologous treatment for burn patients.15 Another famous product (this time allogeneic), developed in 1981, was Apligraf, a composite skin invention capable of rebuilding both the dermis and epidermis of skin wounds.15 With these two therapies and many more being created, TE in the 1980s was booming. At the time, researchers were also developing therapies for cartilage regeneration.

Once the 1990s came around, TE strategies were combined with stem cells (which had just been discovered) to create RM.3, 8 At that time, RM was a hot topic. After the first products for skin were commercialized, scientists became more enthused and started trying other tissues.15 Start‐up companies were popping up left and right, private funding was abnormally high, and public hype was gaining lots of traction. However, governments were not so quick to fund this research and took their time before making decisions, whereas private investors saw this field as very promising and thought it was their ticket to the top.14 Given that 90% of the funding of RM came from the private sector, this greatly influenced the direction of the research and its timeframe.14 People were simply trying to copy tissue formation rather than understanding it, so as to make the development process quicker.3 As a result, many of the technologies that initially looked promising failed in clinical trials or on the market.

These disappointing results coupled with the dot.com crash meant that by the end of 2002, the capital value of the industry was reduced by 90%, the workforce by 80%, and out of the 20 US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) products with clinical trials, only 4 were approved and none had any success.22 This phenomenon has been extensively studied and, according to Lysaght and Hazlehurst, five factors contributed to the industry crash22:

The products were not much better than the existing treatment options and so making the switch was not worth it for clinicians.

Even if the science was good, low‐cost manufacturing procedures did not exist.

The approval process for these novel therapies was unrealistically challenging and the regulatory cost was too high.

Companies lacked the skill to market their new products.

The reimbursement strategies were unclear.

Despite these events, the industry had 89 firms survive the crash and stem cell research was not affected. In fact, from 2000 to 2004, the number of companies increased but the number of jobs decreased, which means investors were supporting research in basic and applied science with smaller firms that were lower risk, and by 2004, the field was dominated by start‐up companies.22 Before the crash, RM was primarily happening in the United States, but in 2004, other countries like the United Kingdom and Japan started catching up.22 The industry slowly started growing again. In 2006, the first engineered tissue (bladder) was implanted, and by 2008, commercial successes were being achieved.3, 10 As an example, hematopoietic stem cell transplants were approved and are now a curative treatment for blood disorders and other immunodeficiencies.7 Now, the RM field had ironically regenerated itself.3 It has gained increased governmental attention (federal funding has increased) and has been recognized as being at the forefront of health care.7, 22 There is once again intense media coverage that is raising public expectations.23 The number and variety of clinical trials is also increasing everywhere.23 According to allied market research, RM is predicted to be worth US $67.5 billion by 2020.10

Unfortunately, regardless of these seemingly cheerful notes, the fact remains that cell therapies remain experimental, except for the aforementioned hematopoietic stem cell treatments.13 The market for RM is still small and will remain so until RM proves that its therapies are better and cheaper than the existing ones.15 Yet, the pressure for clinical translation is increasing through the needs of the population, investors that are eager to make a return on their investments, and scientists who believe that these technologies are the future.23 Moreover, there has been a growing appreciation of the magnitude and complexity of the obstacles the field is facing, but it remains to be seen how they will be solved; although initial steps have already been taken, which will be discussed further below.

The Definition of Translational Medicine

Now that we have established the background for RM, there needs to be a proper understanding of TM before conclusions on how the two are related can be drawn, which is the purpose of the following section.

The European Society for Translational Medicine (EUSTM) has defined TM as an interdisciplinary branch of the biomedical field supported by three main pillars: benchside, bedside, and community. The goals of TM are to combine disciplines, resources, expertise, and techniques within these pillars to promote enhancements in prevention, diagnosis, and therapies.24 TM’s goals can be split into two categories: T1 and T2. T1 is to apply research from bench to bedside and back, whereas T2 is to help move successful new therapies from a research context to an everyday clinical context.25 In other words, TM is a medical practice explicitly devoted to helping basic research attain clinical application. Conceptual medical research, preclinical studies, clinical trials, and implementation of research findings are all included within TM.26

Between basic science and the clinic is an area that is popularly referred to as the valley of death.25 This gap is fraught with not only scientific obstacles (like an unknown molecular mechanism), but social and economic ones as well. This is where many novel ideas “die” and, consequently, companies are weary of going through this valley for fear of wasted financial resources.25 For these reasons, many of the approved drugs we get now are derivatives of others that have been previously approved.25 This is the area that TM seeks to impact, to be the bridge between idea and cure, and to act as a catalyst to increase the efficiency between laboratory and clinic.25, 26 The term “bench to bedside and back” is commonly used. The cost of development for a therapy is very high (estimated at US $800 million to $2.6 billion for a drug) because of increasing regulatory demands and the complexity of clinical trials, among others. TM aims to streamline the early development stages to reduce the time and cost of development.24

What will be important to note for the discussion below is that TM focuses more on the pathophysiological mechanisms of a disease and/or treatment and favors a more trial‐and‐error method rather than an evidence‐based method. Dr. Miriam Solomon argues in his book chapter entitled “What is Translational Medicine?” that most medical innovations proceed unpredictably with interdisciplinary teams and with shifts from laboratory to patient and back again, and that freedom of trial‐and‐error is what will lead to more therapeutic translation.25 Furthermore, for years, TM did not have any technical suggestions for improving translation, only two broad categories that were claimed to be essential for translatability: improving research infrastructure and broadening the goals of inquiry. This discrepancy has since been identified and efforts have been made to address it. For example, the EUSTM provided a textbook called Translational Medicine: Tools and Techniques as an initiative to provide concise knowledge to the field’s stakeholders.24

Presently, TM has attracted considerable attention with substantial funding and numerous institutions and journals committed to its cause.25, 27 But before this, its arrival had to be incited. TM emerged in the late 1990s to offer hope in response to the shortcomings of evidence‐based medicine and basic science research, such as the unsatisfactory results from the Human Genome Project, for instance.25 There were growing concerns that the explosion of biomedical research was not being translated in a meaningful manner proportionate with the expenditures and growing needs of the patients.27 The research had ignored what it took to properly disseminate new ideas.25 The difficulties of translation from bench to bedside have always been known, but what is different with TM is the amount of emphasis that is now put on translation and the recognition on how difficult and multifaceted it is to translate technologies.25 Over the past 20 years, the role, power, and research volume of the field has increased, and TM is now a top priority for the scientific community.26 TM is also often used as common justification for research funding and conveys the message to politicians and taxpayers that research activities ultimately serve the public, which is also why it appeals to today’s generation of students who want to work on big, real‐world problems and make a meaningful difference.28, 29

Impact on the Translational Strategy

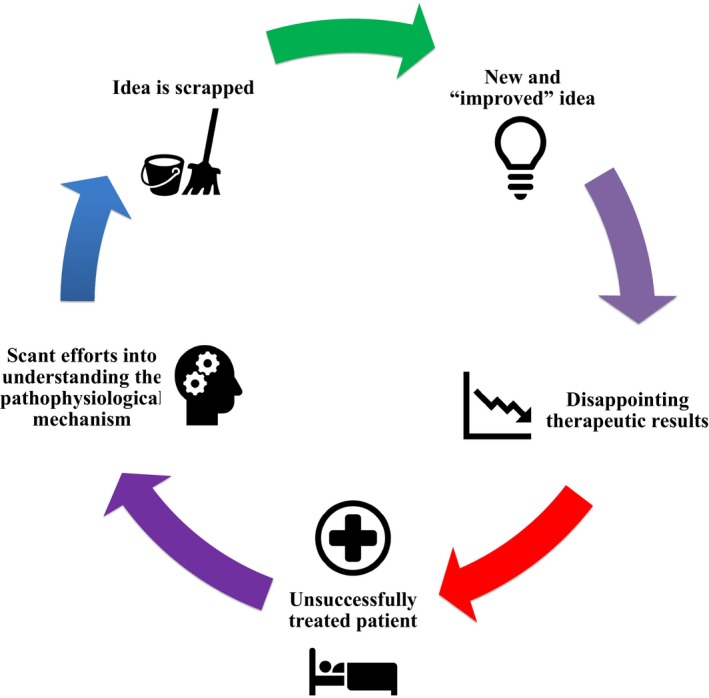

As already mentioned, RM therapies are proving difficult to translate to the clinic.11 Although the basic research discoveries are never ceasing (books such as New Perspectives in Regeneration by Drs. Heber‐Katz and Stocum30, and articles such as "Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine: Past, Present, and Future" by Dr. António Salgado et al.,31 provide comprehensive summaries of these advancements), therapy approval is practically nonexistent.30, 31, 32 This may be due, in part, to a tendency for people to blame the lack of translation of their technologies on extrinsic factors, thus removing responsibility.11 Additionally, the failures are not being studied. For example, stem cell research looks good in small animals but often fails in larger ones and then does not progress beyond phase II or III clinical trials because no benefits are found, and historically we have not been exploring why.11, 32 Consequently, the next therapies that are developed are “improved” by guesses rather than through a better understanding of the disease in mind (Figure 2 ).11

Figure 2.

The negative feedback cycle currently present in most discovery and development processes of regenerative medicine. This cycle obstructs progression of the field.

RM has the potential to impact not only the quality of healthcare but also the economy, because the costs that could be avoided with curative therapies are immense.33 For this reason, analyzing the impact of RM on the translational strategy over time can help identify aspects that should be encouraged or discouraged to drastically improve translation. Reflecting on this history cannot only help us to avoid past mistakes but can also aid in redirecting the field to a once‐productive path.34 In the following section, the preclinical impact of RM on TM will be discussed, focusing on the shift from evidence‐based medicine to trial‐and‐error, the role of the basic scientist, and the emergence of the multidisciplinary approach. Clinical impact is also covered, concentrating on regulatory modifications. Last, changes in the private sector are considered as the shift in business models is detailed.

Preclinical Impact

Because the RM field is essentially comprised of new ideas on cell renewal and tissue healing, it is logical that most of its impact would be on the preclinical side, as this is where ideas are tested, fine‐tuned, and developed. Coincidentally, it is also where the translational strategy begins. Considering certain aspects early in the developmental process, such as realistic applications and ease of use, can help facilitate translation. RM’s influence on TM can thus be separated into the three themes below.

From evidence‐based medicine to trial‐and‐error

Before the late 20th century, the majority of medical research was done using evidence‐based medicine. This is a systematic approach to solving a clinical problem that integrates the best available research evidence together with clinical signs, patient values, and individual clinical experience all to support scientific decision making and research progression.35 As such, evidence‐based medicine favors clinical trials and does not allow for much tinkering and only that which possesses high‐quality clinical evidence is to be pursued. This has its limitations, as it devalues mechanistic reasoning, and both in vitro and animal studies. Therefore, evidence‐based medicine may have played a role in RM’s downfall in the early 2000s. TE in the 1990s was using evidence‐based medicine and was simply trying to copy tissue formation rather than trying to understand it.3 That most of the funding was coming from the private sector probably did not help either. Investors saw TE as an opportunity for quick returns on their investments, so therapies were rushed to clinical trials, which led to inconsistent results.14, 25, 32

As well, evidence‐based medicine obscured the need for different methods of discovery. After RM’s decline and the idea of TM came about, a trial‐and‐error method was adopted. This technique favors a team effort, mechanistic reasoning, and seeks to change the social structure of research.25 Although clinical trials are still deemed important, the trial‐and‐error method identifies that an idea needs to first be explored and should not necessarily require the confirmation of a hypothesis.11, 25 This new method is based more so on facts and has stimulated a more informed dialogue among stakeholders (whereas the confirmation or refusal of a hypothesis cannot always be made relevant to people outside the field). This, in turn, can help the regulatory agencies reduce the burden on their review boards in the evaluation and acceptance of novel strategies.11 Therefore, the failures of RM had helped to highlight the boundaries of evidence‐based medicine and, combined with the rising intensity put on TM in the 1990s, assisted in defining the trial‐and‐error based method.

The role of the basic scientist

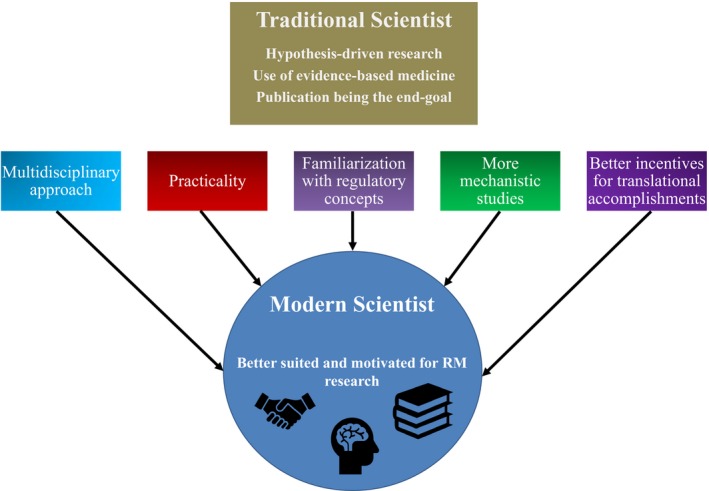

Another thing that is changed with the historical development of RM has been the role of the basic scientist. Please see Figure 3 for a summary of the differences between the traditional and modern scientist discussed in this review. Traditionally, basic scientists have worked with a discovery mindset, but without a noticeable regard for potential therapeutic applications. It has been noted that RM has made us realize how important it is to take the practical and industrializing aspects (like cost, for example) into account even at the basic research level.7, 14 The needs of the end users need to be considered during the developmental phase if RM is to establish a proper foothold within the market.15 In view of this, over the past 2 decades, medical philosophy has changed in that it encourages basic scientists to communicate more with clinicians and vice versa. Experts like Barry Coller, MD, Vice President for Medical Affairs and Physician‐in‐Chief at the Rockefeller University Medical Center, have identified various skills that a basic scientist must possess if translational research is to be improved.26, 28 Additionally, other researchers have commented that more and more basic scientists are motivated to have an impact on global health and this passion can be a source of inspiration that can help fuel interdisciplinary cooperation.28 Efforts have also been made to familiarize basic scientists with regulatory requirements. For example, the FDA publishes guide documents with recommendations on how to address these requirements.36 Despite this, much remains to be done, as there is still a lack of TM professionals and the current research environment hampers cooperation between experts (e.g., specialization is still encouraged, and achievement awards are individualized).26, 28

Figure 3.

A comparison between the traditional and modern scientist. Although traditional scientists are more hypothesis‐driven and rigid in terms of research methodology, if the concepts shown above are used, it can generate the modern scientist who is better suited for the translation of regenerative therapies. RM, regenerative medicine.

An additional point that can be argued is that because RM got basic scientists more involved in the translational process, this has consequently made them more realistic.37 As already mentioned, early RM therapies were comprised of complex cell therapies that were not fully understood. From 2004 onward, the field diversified to include research into “simpler” acellular products.38 Other avenues, such as induced pluripotent stem cells, endogenous repair, nanotechnology, and regenerative pharmacology, are also being explored.37, 39, 40, 41 Increasingly, experts are trying to spread this message; for instance, in the field of cardiology, Dr. Mark Sussman, a world renowned cardiac researcher, and his colleague Dr. Kathleen Broughton at the San Diego State University Heart Institute and the Integrated Regenerative Research Institute, recently stated that “After over a decade of myocardial regenerative research studies, the initial optimism and enthusiasm that fueled rapid and widespread adoption of cellular therapies for heart failure has given way to more pragmatic, realistic, and achievable goals.”9

The multidisciplinary approach

The last preclinical impact of RM to be discussed is the arrival of the multidisciplinary approach. This now widespread notion identifies that to improve translation and accelerate technology development, it is better to have a team composed of experts from multiple disciplines, because the various backgrounds and schools of thought can be combined with each contributing to a project in a different way.25, 39 What has surely incited its evolution is that RM inherently requires contributions from biologists, chemists, engineers, and medical professionals. This need has led to the formation of institutions that house all the required expertise under the same roof (such centers have increased in number since 2003), which promotes more teamwork between laboratories and clinics.28 Dr. Jennifer Hobin et al.28 states that bringing dissimilar research expertise together in close proximity is the key to creating an environment that facilitates collaboration. In addition, it could be said that these collaborative environments help minimize the flaws of medical specialization, which occurred in the second half of the 19th century; where the ideological basis that the human body can be categorized combined with the rapid arrival of new medical technologies led to the specialization of medical practice, which, in turn, led to the segregation of medical professionals from each other and the patient.42 Coincidentally, if one recalls the definition of TM, it, along with the trial‐and‐error based method, suggests that improved research infrastructures and team efforts can facilitate the translation of therapies.

Clinical Impact

We now look at the influence that RM has had on the clinical side of therapy development. Before the subject is discussed, it is important to note that the reason clinical research has been affected is because of the uniqueness of RM therapies. Their novelty does not fit within the current regulatory process or use in clinical trials, and although the latter has yet to adapt, the regulatory sector has attempted over the years to facilitate the journey from bench to bedside.7, 43, 44

Regulatory modifications

Initially, when RM was in its infancy, its therapies were regulated by the criteria originally developed for drugs; and as we have seen, this was identified as a factor that led to its downfall. Now, in 2019, several regulatory changes have been implemented to rectify this. What has helped has been the input from other countries. As mentioned above, RM started in the United States, but after the crash, other countries like the United Kingdom and Japan caught up, and their less stringent regulatory procedures have allowed them to better adapt the framework for these new therapies.22 In 2007, the European Union passed the Advanced Therapy Products Regulation law, which defined regenerative therapies, categorized them, and provided them with separate regulatory criteria for advanced approval.13, 43 In 2014, public pressure and researcher demands led Japan to enact three new laws: the Regenerative Medicine Promotion Act, the Pharmaceuticals, Medical Devices, and Other Therapeutic Products Act, and the Act on the Safety of Regenerative Medicine. These unprecedented national policies now help therapies gain accelerated and conditional approval to better conduct clinical trials and to better meet the demands of the patients.7, 13, 44, 45 During this time, the United States has not stood idle. In 2012, the US Congress passed the FDA Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA), which expanded its existing Accelerated Approval Pathway to include “breakthrough therapies,” a category created for new emerging technologies, including regenerative strategies.13, 46 Drs. Celia Witten, Richard McFarland, and Stephanie Simek provide a well‐written overview on the efforts of the FDA to accommodate RM.36 By and large, it is safe to say that RM has spurred a drastic change in traditional regulatory pathways to not only better manage these novel therapies but also put more weight on efficient translation.

Impact on the Private Sector

It is also important to discuss changes in the private sector because manufacturing and marketing is and will remain one of the greatest obstacles facing RM, and, once again, the novelty of the field is responsible. Although the bulk of the problems remain, there has nonetheless been a change in business strategies that is worth appreciating.

Shifting business models

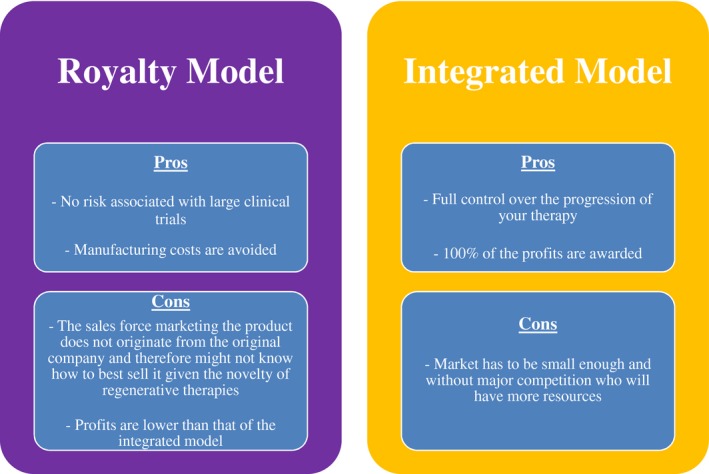

Throughout its history, RM research has been carried out by academic research institutions or small and medium‐sized enterprises.23, 47 With this in mind, the business model used in the health industry varies depending on the type of company. The royalty model is the one primarily used by biotech companies.8, 14 Here, businesses will develop a therapy up to the clinical stage and then hand it off to a company with more resources (usually a pharmaceutical one) who can carry out the larger scale studies. With this model, biotech companies make money simply through royalties and this carries both pros and cons (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A comparison of both the royalty and integrated business models used by private companies in the biomedical industry. The pros and cons are listed with the assumption that they are for a start‐up company in regenerative medicine.

Because the market for regenerative therapies currently is not big enough for the royalty model, start‐ups have had to shift to an integrated model where the discovery, development, approval, and manufacturing of a new therapy are all done internally (which is unusual for small start‐ups).8 Using this strategy, the companies can reap all the rewards but obviously also assume all the risk.

The market for regenerative therapies has so far been small enough that smaller firms do not have to manufacture large quantities of their products (like they do in the pharmaceutical industry) and they can start making money in a quicker fashion.8 Whether the business model will change again as the market grows or if the original start‐ups will grow in proportion remains to be seen.14 What is to be highlighted here is that those who seek to commercialize regenerative therapies have had to shift to an integrated business model (that was not previously the norm for smaller ventures), which has affected translation by letting them have more influence in determining how their therapy is being developed, marketed, and manufactured.

Translational Challenges

Having detailed RM’s relationship with the translation strategy and the aspects that changed in conjunction with the field’s development, the remainder of the review will summarize the challenges that are contributing to RM’s modest performance in the clinic.

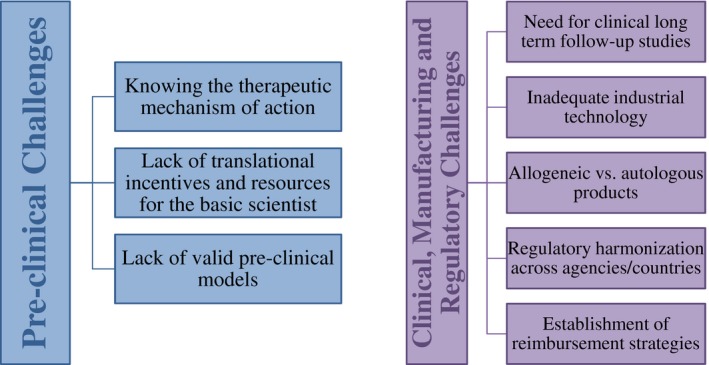

With increased funding and a growing number of committed institutions, many countries have become increasingly invested in RM’s success. For example, the US Department of Health and Human Services recognizes RM as being at the forefront of healthcare.7 As well, the UK government has identified RM as a field in which they can become global leaders and that will generate significant economic returns.44 The literature indicates that RM is reaching a critical mass and is on the verge of a significant clinical transition. The optimism is as high as it has ever been and the rush to succeed with clinical trials is equally felt.23 However, the bottom line is that the clinical and market performance is still very poor. Being that a gold standard for treatment in RM remains elusive, clinicians are often ill‐informed about current applications, and studies on safety and efficacy are lacking.23, 44, 48, 49 The National Institute of Health estimates that 80–90% of potential therapies run into problems during the preclinical phase.28 Naturally, scientists have offered various explanations for these results, such as deficiencies in translational science and poor research practices in the clinical sciences.50 Shockingly, in a 2004 analysis, 101 articles by basic scientists were found that clearly promised a product with major clinical application, and yet 20 years later, only 5 were licensed and only 1 had a major impact.50 Therefore, it is easily deducible that many challenges still lie ahead. The perceived risk‐benefit ratio remains high and, as a consequence, clinical trials have been proceeding with caution.13, 23, 33 Numerous reviews have been published on these challenges but with an emphasis on those relating to the clinical phase.11, 13, 22, 51 Although these will be summarized below, the present study highlights the identification and analysis of the preclinical challenges. Please see Figure 5 for a summary of the preclinical and clinical obstacles discussed herein.

Figure 5.

Summary of the preclinical and postclinical challenges discussed. Even though preclinical obstacles to the translation of regenerative medicine therapies are more elusive, they are just as significant as their counterparts.

Preclinical Challenges

To begin, a possible explanation for the preclinical obstacles being under‐represented in the literature is because of the pliability of the phase itself. Although the clinical phase is composed of numerous subphases and strict protocols, the preclinical research is much less structured with less oversight. Whereas rigorous scientific method is applied to the experiments themselves, which usually consist of in vitro followed by in vivo experiments, the basic scientist has more flexibility regarding experimental organization, structure, and backtracking; thus, making explicit challenges possibly harder to recognize.

Some researchers have nevertheless attempted to do so. For example, Dr. Jennifer Hobin et al. have identified three major risks associated with RM technologies as being tumorigenicity, immunogenicity, and risks involved with the implantation procedure.13 The first two relate to arguably the largest preclinical challenge, which have been identified as needing a better understanding of the mechanism of action.12 Although the difficulties of identifying a mechanism are appreciated in the scientific community, it is imperative that improvements in this area are made as it will affect application and manufacturing decisions. Hence, greater emphasis on identifying the mechanism of action(s) will need to be adopted by basic scientists who are looking to develop a technology.

Another significant preclinical challenge is the lack of translation streamlining for basic scientists. Although basic scientists have become more involved in the translational process and more pragmatic over the years, there is, in general, still a lack of incentive and available resources to help a scientist translate their research. Academic faculty members are given tenure and promotion based on funding success (grants) and intellectual contributions (publications).28 Thus, researchers who have received money to conduct research and publish their work on a promising new therapy might stop short of translation as there may be no additional recognizable accomplishment or motivation for such an endeavor. For example, Jennifer Hobin et al. described the case of Dr. Daria Mochly‐Rosen at Stanford University’s Translational Research Program, who sought help for an interesting idea for a heart rate regulation therapy.13 She was turned down by numerous companies that found the clinical challenges too daunting and her colleagues offered no support but rather discouraged her from pursuing the idea saying that it would not be worthwhile for her career.

Last, a very important preclinical challenge that has gained recognition over the past few years is the lack of appropriate preclinical testing models. It is often reported that novel therapies that do well in the laboratory but then fail in larger animal studies or clinical trials. This is partly due to a lack of mechanistic insight, but also because of a shortage of appropriate in vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo models.9, 36 With properly validated preclinical models, we would be better able to gauge the performance of novel therapies and predict their future clinical success, but instead we are misidentifying the potential of therapies. Notably, the lack of appropriate models also contributes to the difficulty in obtaining reliable data on the underlying mechanism(s) of action of RM therapies, as differences may exist between the preclinical and clinical settings.

Clinical, Manufacturing, and Regulatory Challenges

As far as clinical challenges go, they are numerous. Stem cell trials in particular have received criticism from a perceived lack of rigor and controlled trials.23 Related to this, a potent point that has arisen over the past few years is the absence of long‐term follow‐up studies for clinical trials, which is clearly necessary to establish the safety and efficacy of these interventions.13, 33 Unfortunately, they are costly and they are time‐consuming. Efforts are nonetheless being made to overcome these obstacles. For example, in 2015, the Mayo Clinic released an RM build‐out perspective offering “a blueprint for the discovery, translation and application of regenerative medicine therapies for accelerated adoption into standard of care.”7 Institutions, such as Canada’s Center for Commercialization of Regenerative Medicine, have been launched to help researchers mitigate the risks of cell therapy development by offering technical as well as business services.12, 51 Experts are also stepping up; for example, Drs. Arnold Caplan and Michael West proposed a new regulatory pathway that incorporates large postmarket studies into clinical trials.33

In terms of manufacturing, it is difficult to engage industry because the necessary technology to produce RM therapies at an industrial level does not exist yet. Scale‐out and automated production methods for the manufacturing of regenerative therapies are needed.7, 10, 12, 23, 52, 53 This challenge stems from the complexity and natural intrinsic variation of the biological components, which makes long‐term stability difficult to achieve and increases manufacturing costs.13, 44 Now, if RM therapies could establish their superiority over conventional treatments, then this would potentially alleviate costs and increase the likelihood of being reimbursed, but it remains to be seen.13 A hot topic at the moment is the choice between autologous or allogeneic‐based products, which would entail either a centralized or decentralized manufacturing model, respectively (although hybrid models have been proposed).7, 23, 54 Autologous products, being patient‐specific, have the advantage of having smaller start‐up costs, simpler regulations, and point of care processing.47 As for allogeneic products, they are more suitable for an “off the shelf” product, for a scale‐out model and quality controls can be applied in bulk.47, 54 Dr. Yves Bayon et al.51 provided a thorough description of this topic while simultaneously indicating areas that have been identified for improvement.

As mentioned above, regulatory challenges are what have been most addressed thus far through scientific and public pressure. Moving forward, the goal identified by expert think‐tank sessions is to harmonize RM‐specific regulations across agencies and countries.7, 36 Reimbursement is the last of the regulatory challenges to be considered. In order for RM treatments to become broadly available, reimbursement is a necessity and both public and private healthcare need to determine how the regulations will be modified for disruptive therapies coming down the pipeline.13, 23, 44

Conclusion

RM has had an undeniable influence on the process of bench to bedside research. Preclinically, it has helped identify the limitations of evidence‐based medicine and contributed to the paradigm shift to the trial‐and‐error method. Likewise, the field has changed its mindset and the basic scientist is adopting new responsibilities becoming more motivated, pragmatic, and involved in TM, rivaling researchers in the applied sciences. The multidisciplinary approach has also been promoted by RM over the years and institutions dedicated to fostering collaborative research in RM have increased in numbers. Clinically, regulatory pathways that were developed for drugs and biomedical devices, and which have been in place for decades, have been adapted to aid RM’s disruptive technologies, leading to new guidelines that favor translation. In the private sector, the novel nature of RM therapies has led to start‐up companies using an alternative business model that provides them top‐to‐bottom authority over the development of their products and it is yet to be seen if the business strategy in place will be sufficient as the industry grows.

If the translation of RM therapies is to be improved, many of the challenges to be overcome lie in the early stages of therapy development, such as identifying the mechanism(s) of action, validating preclinical experimental models, and incentivizing translational research for basic scientists. In later stages, regulatory changes have been made, but much still needs to be addressed. This includes the adoption of clinical trials that are more rigorous and include long‐term follow‐up studies, the development of appropriate manufacturing technology, the synchronization of regulatory agencies, and a clear plan for reimbursement strategies. Once again, these challenges have been discussed in greater detail in previous works.2, 3, 7, 12, 13, 15, 22, 23, 26, 31, 38, 44, 48, 51, 52 While it seems that the field may be at a tipping point with many challenges remaining, the fact that translation has been influenced in a positive way gives promise to the future progression of RM therapies.

Funding

This work was supported by a Collaborative Research Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC; CPG‐158280 to E.J.S.), and the Hetenyi Memorial Studentship from the University of Ottawa (to E.J.).

Conflict of Interest

All authors declared no competing interest for this work.

References

- 1. Barker, C.F. & Markmann, J.F. Historical overview of transplantation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 3, 1–18 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sampogna, G. , Guraya, S.Y. & Forgione, A. Regenerative medicine: historical roots and potential strategies in modern medicine. J. Microsc. Ultrastruct. 3, 101–107 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Slingerland, A.S. , Smits, A.I.P.M. & Bouten, C.V.C. Then and now: hypes and hopes of regenerative medicine. Trends Biotechnol. 31, 121–123 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Langer, R. & Vacanti, J.P. Tissue engineering. Science 13260, 920–926 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Greenwood, H.L. , Thorsteinsdottir, H. , Perry, G. , Renihan, J. , Singer, P. & Daar, A. Regenerative medicine: new opportunities for developing countries. Int. J. Biotechnol. 8, 60–77 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mason, C. & Dunnill, P. A brief definition of regenerative medicine. Regen. Med. 3, 1–5 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Terzic, A. , Pfenning, M.A. , Gores, G.J. & Harper, C.M. Jr. Regenerative medicine build‐out. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 4, 1373–1379 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kaul, H. & Ventikos, Y. On the genealogy of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 21, 203–217 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Broughton, K.M. & Sussman, M.A. Enhancement strategies for cardiac regenerative cell therapy. Circ. Res. 123, 177–187 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Allickson, J.G. Emerging translation of regenerative therapies. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 101, 28–30 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marincola, F.M. The trouble with translational medicine. J. Intern. Med. 270, 123–127 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heathman, T.R. , Nienow, A.W. , McCall, M.J. , Coopman, K. , Kara, B. & Hewitt, C.J. The translation of cell‐based therapies: clinical landscape and manufacturing challenges. Regen. Med. 10, 49–64 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mount, N.M. , Ward, S.J. , Kefalas, P. & Hyllner, J. Cell‐based therapy technology classifications and translational challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 370, 20150017 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kemp, P. History of regenerative medicine: looking backwards to move forwards. Regen. Med. 1, 653–669 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berthiaume, F. , Maguire, T.J. & Yarmush, M.L. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: history, progress, and challenges. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2, 403–430 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Murillo‐González, J. Evolution of embryology: a synthesis of classical, experimental, and molecular perspectives. Clin. Anat. 163, 158–163 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goss, R.J. The natural history (and mystery) of regeneration In A History of Regeneration Research: Milestones in the Evolution of a Science. (ed. Dinsmore C.E.) 7–23 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1991). [Google Scholar]

- 18. Skinner, D.M. & Cook, S.J. New limbs for old: some highlights in the history of regeneration in Crustacae In A History of Regeneration Research: Milestones in the Evolution of a Science. (ed. Dinsmore C.E.) 25–45 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1991). [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lenhoff, H.M. , Lenhoff, S.G. & Trembley, A. The origins of research on regeneration in animals In A History of Regeneration Research: Milestones in the Evolution of a Science. (ed. Dinsmore C.E.) 47–65 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1991). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Singer, M. & Géraudie, J. The neurotrophic phenomenon: its history during limb regeneration in the newt In A History of Regeneration Research: Milestones in the Evolution of a Science. (ed. Dinsmore C.E.) 101–110 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1991). [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smit, F.E. & Dohmen, P.M. Cardiovascular tissue engineering: where we come from and where are we now? Med. Sci. Monit. Basic Res. 20, 1–3 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lysaght, M.J. & Hazlehurst, A.L. Tissue engineering: the end of the beginning. Tissue Eng. 383, 193–195 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li, M.D. , Atkins, H. & Bubela, T. The global landscape of stem cell clinical trials. Regen. Med. 9, 27–39 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shahzad, A. Translational Medicine: Tools and Techniques. (Elsevier, Amsterdam, UK, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25. Solomon, M. What is translational medicine? In Making Medical Knowledge. (ed. Solomon, M. ). (Oxford Scholarship Online, Oxford, UK, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen, F.M. , Zhao, Y.M. , Jin, Y. & Shi, S. Prospects for translational regenerative medicine. Biotechnol. Adv. 30, 658–672 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Woolf, S.H. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 299, 211–213 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hobin, J.A. et al Engaging basic scientists in translational research: identifying opportunities, overcoming obstacles. J. Transl. Med. 10, 1 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gannon, F. The steps from translatable to translational research. EMBO Rep. 15, 1107–1108 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Heber‐Katz, E. & Stocum, D. New Perspectives in Regeneration. Vol. 367. (Springer, New York, NY, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 31. Salgado, A.J. et al Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine: Past, Present, and Future. Vol. 108. (Elsevier, Amsterdam, UK, 2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dulak, J. , Szade, K. , Szade, A. , Nowak, W. & Józkowicz, A. Adult stem cells: hopes and hypes of regenerative medicine. Acta Biochim. Pol. 62, 329–337 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Caplan, A.I. & West, M.D. Progressive approval: a proposal for a new regulatory pathway for regenerative medicine. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 3, 560–563 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maienschein, J. Regenerative medicine’s historical roots in regeneration, transplantation, and translation. Dev. Biol. 358, 278–284 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Masic, I. , Miokovic, M. & Muhamedagic, B. Evidence based medicine ‐ new approaches and challenges. Acta Inform. Medica 16, 219 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Witten, C.M. , McFarland, R.D. & Simek, S.L. Concise review: the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and regenerative medicine. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 4, 1495–1499 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lu, B. & Atala, A. Small molecules and small molecule drugs in regenerative medicine. Drug Discov. Today 19, 801–808 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lysaght, M.J. , Jaklenec, A. & Deweerd, E. Great expectations: private sector activity in tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, and stem cell therapeutics. Tissue Eng. Part A 14, 305–315 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen, C. , Dubin, R. & Kim, M.C. Emerging trends and new developments in regenerative medicine: a scientometric update (2000–2014). Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 14, 1295–1317 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chen, C. , Hu, Z. , Liu, S. & Tseng, H. Emerging trends in regenerative medicine: a scientometric analysis in CiteSpace. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 12, 593–608 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Christ, G.J. , Saul, J.M. , Furth, M.E. & Andersson, K.‐E. The pharmacology of regenerative medicine. Pharmacol. Rev. 65, 1091–1133 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Reiser, S.J. Medical specialisation and the centralization of medical care In Medicine and the Reign of Technology. (ed. Reiser, S.J. ) 144–158. (Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, 1978). [Google Scholar]

- 43. Faulkner, A. Law’s performativities: shaping the emergence of regenerative medicine through European Union legislation. Soc. Stud. Sci. 42, 753–774 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gardner, J.G. , Faulkner, A. , Mahalatchimy, A. & Webster, A.J. Are there specific translational challenges in regenerative medicine? Lessons from other fields. Regen. Med. 10, 885–895 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tobita, M. , Konomi, K. , Torashima, Y. , Kimura, K. , Taoka, M. & Kaminota, M. Japan’s challenges of translational regenerative medicine: act on the safety of regenerative medicine. Regen. Ther. 4, 78–81 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mason, C. et al The global cell therapy industry continues to rise during the second and third quarters of 2012. Cell Stem Cell 11, 735–739 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Corbett, M.S. , Webster, A. , Hawkins, R. & Woolacott, N. Innovative regenerative medicines in the EU: a better future in evidence? BMC Med. 15, 1–8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Colombo, F. , Sampogna, G. , Cocozza, G. , Guraya, S.Y. & Forgione, A. Regenerative medicine: clinical applications and future perspectives. J. Microsc. Ultrastruct. 5, 1–8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Daley, G.Q. , Goodell, M.A. & Snyder, E.Y. Realistic prospects for stem cell therapeutics. Hematol. Educ. B 1, 398–418 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ioannidis, J.P.A. Materializing research promises: opportunities, priorities and conflicts in translational medicine. J. Transl. Med. 2, 5 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bayon, Y. et al Turning regenerative medicine breakthrough ideas and innovations into commercial products. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 21, 560–571 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Griffith, L.G. & Naughton, G. Tissue engineering–current challenges and expanding opportunities. Science 295, 1009–1014 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Williams, D.J. et al Precision manufacturing for clinical‐quality regenerative medicines. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 370, 3924–3949 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hunsberger, J. et al Manufacturing road map for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine technologies. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 4, 130–135 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]