Abstract

Background

Anlotinib has been shown to prolong progression‐free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) for non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Herein we sought to analyze the effect of anlotinib in managing brain metastases (BM) and its brain‐associated toxicities.

Methods

The PFS and OS of anlotinib versus placebo in those with and without BM recorded at baseline were calculated and compared respectively. Time to brain progression (TTBP), a direct indicator of intracranial control, was also compared between anlotinib and placebo. All calculations were adjusted for confounding factors, including stage, histology, driver mutation type, and therapy history.

Results

A total of 437 patients were included; 97 cases were recorded with BM at baseline. For patients with BM at baseline, anlotinib was associated with longer PFS (hazard ratio [HR], 0.29; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.15–0.56) and OS (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.42–1.12), presenting similar extent of improvement in those without BM (PFS: HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.24–0.45; OS: HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.50–0.91). Specifically, the intracranial objective response rate was 14.3% and the disease control rate was 85.7% in patients with BM who were treated with anlotinib. Anlotinib was associated with longer TTBP (HR, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.03–0.41; p = .001) despite all confounders. Additionally, anlotinib was associated with more neural toxicities (18.4% vs. 8.4%) and psychological symptoms (49.3% vs. 35.7%) but not with infarction or cerebral hemorrhage.

Conclusion

Anlotinib can benefit patients with advanced NSCLC with BM and is highly potent in the management of intracranial lesions. Its special effect on BM and cerebral tissue merits further investigation. (http://clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT02388919).

Short abstract

Anlotinib, a novel multi‐targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has a broad spectrum of inhibitory action on tumor angiogenesis. This article reports results of a phase III trial that explored whether anlotinib is effective for intracranial lesions in advanced non‐small cell lung cancer and evaluated the effect of anlotinib in managing brain metastases and its brain‐associated toxicities.

Background

Approximately 20%–30% of patients with advanced non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) present with brain metastases (BM) at the time of initial diagnosis 1; this rate is higher when driver mutations exist 2. Traditional chemotherapies are mostly ineffective, as they do not cross the blood‐brain barrier. Many clinical trials have demonstrated that tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs; e.g., lorlatinib, osimertinib) offer benefits in intracranial disease control 3. Antiangiogenesis therapy has also been reported to improve survival outcomes in patients with NSCLC 4, and life expectancy could be improved further when combined with erlotinib for patients harboring endothelial growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation 5. However, it remains unclear whether vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR)‐TKI is effective for brain metastases.

Anlotinib is a novel multitargeted TKI that has a broad spectrum of inhibitory action on tumor angiogenesis. A phase III trial (ALTER0303) showed that anlotinib improved progression‐free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) as a second‐ or third‐line therapy in patients with NSCLC 6. With an aim to explore whether anlotinib is effective for intracranial lesions in advanced NSCLC, we evaluated the effect of anlotinib in managing BM and its brain‐associated toxicities from this phase III trial.

Materials and Methods

All data were retrieved from the ALTER trial (NCT02388919) designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of anlotinib in patients with advanced NSCLC 6. Details on patient eligibility criteria, stratification, randomization, treatment, and assessments were described previously. In this study, the primary outcome was time to brain progression (TTBP), which was defined as the duration between randomization and objective intracranial progression. In terms of intracranial objective response rate, target brain lesions were those with the longest diameter larger than 1 cm and without previous radiotherapy.

Demographic characteristics were presented as categorical variables, which were performed using Pearson's chi‐square test or Fisher's exact test. The between‐group comparisons of PFS, OS, and TTBP were performed by multivariate Cox proportional hazards models. Subgroup analyses in TTBP were assessed with the use of stratified Cox proportional hazards models by randomized stratification factors. All statistical tests were two‐sided, and all tests were considered significant for p < .05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics version 25.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

Results

In the present study, 437 patients (294 receiving anlotinib and 143 receiving placebo) were included in the full analysis, among whom 97 (22.2%) patients were identified with BM at baseline. Demographic and baseline characteristics were well balanced between treatment arms in patients with or without BM at baseline (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical baseline characteristics of patients with and without brain metastasis

| Characteristics | Brain metastasis group, n (%) | Without brain metastasis group, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anlotinib (n = 67) | Placebo (n = 30) | p value | Anlotinib (n = 227) | Placebo (n = 113) | p value | |

| Age, years | ||||||

| ≤60 | 45 (67.2) | 22 (73.3) | .540 | 103 (45.4) | 64 (56.6) | .05 |

| >60 | 22 (32.8) | 8 (26.7) | 124 (54.6) | 49 (43.3) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 42 (62.7) | 19 (63.3) | .951 | 146 (64.3) | 78 (69.0) | .386 |

| Female | 25 (37.3) | 11 (36.7) | 81 (35.7) | 35 (31.0) | ||

| Pathology | ||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 57 (85.1) | 29 (96.7) | .57 | 170 (74.9) | 82 (72.6) | .178 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 7 (10.4) | 1 (3.3) | 44 (19.4) | 31 (27.4) | ||

| Other subtypes | 3 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 13 (5.7) | 0 (0) | ||

| Driver gene EGFR | ||||||

| Wild type (−) | 47 (70.1) | 17 (56.7) | .199 | 154 (67.8) | 81 (71.7) | .468 |

| Mutant type (+) | 20 (29.9) | 13 (43.3) | 73 (32.2) | 32 (28.3) | ||

| Driver gene ALK | ||||||

| Wild type (−) | 65 (97.0) | 28 (93.4) | .55 | 221 (97.3) | 112 (99.1) | .521 |

| Mutant type (+) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (3.3) | 4 (1.8) | 1 (0.9) | ||

| Unclear | 1 (1.5) | 1 (3.3) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0) | ||

| Clinical staging | ||||||

| Stage III B | 2 (3.0) | 2 (6.7) | .417 | 13 (5.7) | 5 (4.4) | .608 |

| Stage IV | 65 (97.0) | 28 (93.3) | 214 (94.3) | 108 (95.6) | ||

| History of smoking | ||||||

| No | 36 (53.7) | 15 (50.0) | .734 | 117 (51.5) | 49 (43.4) | .155 |

| Yes | 31 (46.3) | 15 (50.0) | 110 (48.5) | 64 (56.6) | ||

| History of targeted medication | ||||||

| No | 27 (40.3) | 10 (33.3) | .512 | 109 (48.0) | 64 (56.6) | .134 |

| Yes | 40 (59.7) | 20 (66.7) | 118 (52.0) | 49 (43.4) | ||

| ECOG PS | ||||||

| 0 | 13 (19.4) | 5 (20.0) | .79 | 46 (20.3) | 17 (15.0) | .408 |

| 1 | 53 (79.1) | 25 (80.0) | 180 (79.3) | 95 (84.1) | ||

| 2 | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.9) | ||

| History of chemotherapy line | ||||||

| First line | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | .37 | 4 (1.7) | 0 (0) | .357 |

| Second line | 40 (59.7) | 15 (50) | 127 (55.9) | 63 (55.8) | ||

| Third line | 27 (40.3) | 15 (50) | 96 (42.3) | 50 (44.2) | ||

| History of brain radiotherapy | ||||||

| No | 42 (62.7) | 21 (70.0) | .482 | — | — | — |

| Yes | 25 (37.3) | 9 (30.0) | — | — | ||

Abbreviations: ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase fusion; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; EGFR, endothelial growth factor receptor.

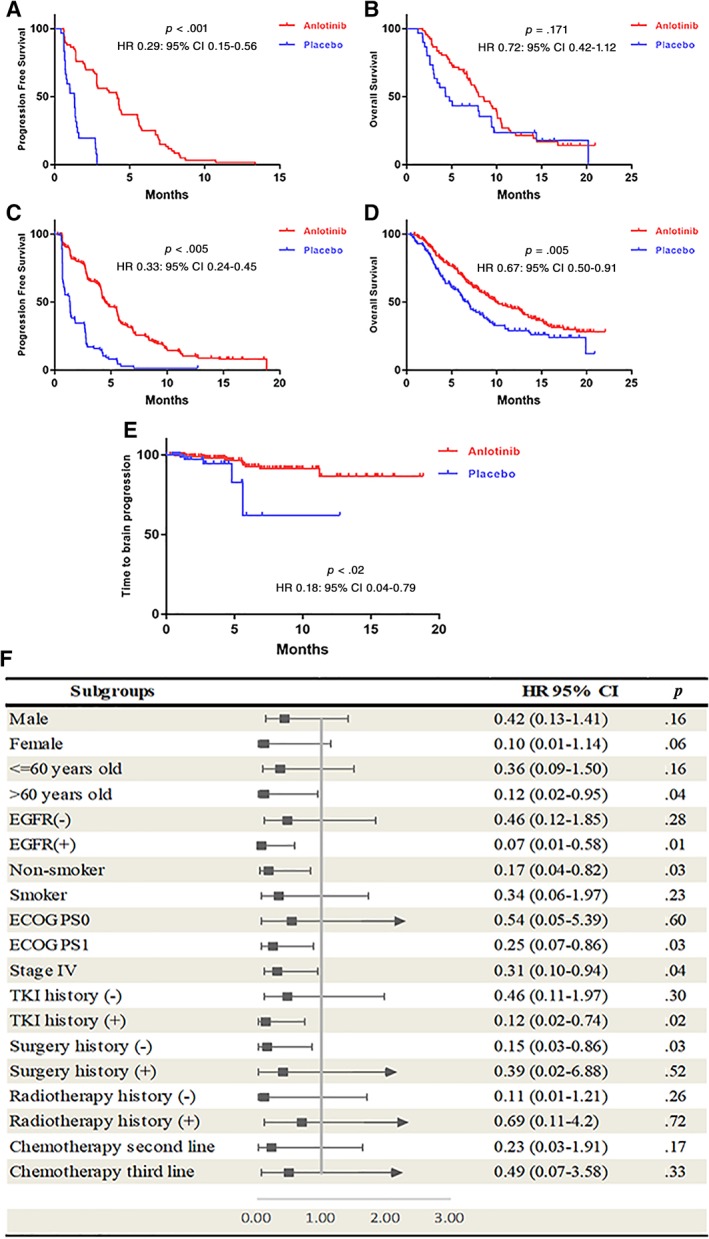

For patients with BM at baseline, anlotinib was associated with longer PFS (median PFS, 4.17 vs. 1.30 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.29; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.15–0.56) and OS (median OS, 8.57 vs. 4.55 months; HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.42–1.12), sharing similar extent of benefits with those without BM (median PFS, 4.53 vs. 1.37 months; PFS HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.24–0.45; median OS, 9.93 vs. 6.80 months; OS HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.50–0.91; Fig. 1A–D). There was no interaction effect between the PFS benefit (p = .69) and OS benefit (p = .79) in patients with and without BM.

Figure 1.

The survival analysis of Anlotinib in different population. (A): Progression‐free survival for patients with brain metastases (BM) at baseline. (B): Overall survival for patients with BM at baseline. (C): Progression‐free survival for patients without BM at baseline. (D): Overall survival for patients without BM at baseline. (E): Kaplan‐Meier estimates of time to brain progression. (F): Subgroup analysis for time to brain progression.Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; EGFR, endothelial growth factor receptor; HR, hazard ratio; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

In the anlotinib group, 14 patients with BM at baseline were identified with target brain lesions. The intracranial objective response rate was 14.3%, and the disease control rate was 85.7% in these patients, among whom 2 had partial response (14.3%), 10 had stable disease (71.4%), and 2 had progressive disease (14.3%).

Anlotinib was associated with significantly longer TTBP (HR, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.04–0.79; p = .02) compared with placebo (Fig. 1E). After adjustment of all confounders, the anlotinib group also showed longer TTBP (HR, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.03–0.41; p = .001).

Subgroup analyses indicated a trend of TTBP benefits in favor of anlotinib (Fig. 1F). Significantly longer TTBP was observed in the following subgroups: age over 60 years (HR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.02–0.95), EGFR mutation (HR, 0.07; 95% CI, 0.01–0.58), nonsmoker (HR, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.04–0.82), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 1 (HR, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.07–0.86), stage IV (HR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.10–0.94), previous receipt of targeted TKI therapy (HR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.02–0.74), or surgery (HR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.03–0.86). These results indicated that anlotinib improves the intracranial local control in patients with advanced NSCLC.

Anlotinib was associated with more neural toxicities (18. 4% vs. 8.4%, p = .007) and psychological symptoms (49.3% vs. 35.7%, p = .008) compared with placebo, but not infarction or cerebral hemorrhage (supplemental online material).

Discussion

Antiangiogenesis therapy, such as ramucirumab and anlotinib, was reported to have a reasonable clinical efficacy versus placebo in second‐ or third‐line therapy for NSCLC 6, 7. This analysis was based on the ALTER 0303 trial, with well‐balanced treatment arms at baseline, thus providing a robust data set. Improvements in intracranial efficacy of anlotinib were seen in patients with and without BM at study entry; the survival outcomes also favored the anlotinib group, regardless of BM status. These results suggested that anlotinib has activity in the brain and plays a potential role in tumor control at intracranial sites.

Anlotinib suppressed tumor cell proliferation via inhibition of platelet‐derived growth factor receptors α and β, c‐Kit, and Ret as well as Aurora‐B, c‐FMS, and discoidin domain receptor 1, which was a group of newly identified kinase targets involving the tumor progression 8. In addition, anlotinib showed antitumor activity against tumor cells carrying mutations in platelet‐derived growth factor receptor α, c‐Kit, Met, and epidermal growth factor receptor. There has been no preclinical study indicating that anlotinib could cross the blood‐brain barrier; this clinical evidence suggests preclinical study should focus on the mechanism of anti–brain metastatic tumor effect of multitargeted agents.

Limitations of this analysis primarily stem from its post hoc nature, which affects heterogeneity and does not allow for randomization of the population and thus decreases the argument power. In addition, another inherent bias is owing to small case numbers with target brain lesions at baseline. Lastly, anlotinib is currently only available in China; however, it may be a good representation of multitargeted agents, such as sunitinib and sorafenib.

Conclusion

In this study, we indicated the potential efficacy of multitargeted inhibitor for BM in patients with advanced NSCLC. Further studies of other multitargeted inhibitors could validate this effect.

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Supporting information

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplemental Appendices

Supplemental Tables

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families who contributed to this study.

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

No part of this article may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or for any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. For information on purchasing reprints contact Commercialreprints@wiley.com. For permission information contact permissions@wiley.com.

Contributor Information

Jianxing He, Email: drjianxing.he@gmail.com.

Wenhua Liang, Email: liangwh1987@163.com.

References

- 1. Barnholtz‐Sloan JS, Sloan AE, Davis FG et al. Incidence proportions of brain metastases in patients diagnosed (1973 to 2001) in the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:2865–2872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bhatt VR, Kedia S, Kessinger A et al. Brain metastasis in patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer and epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3162–3164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Franchino F, Rudà R, Soffietti R. Mechanisms and therapy for cancer metastasis to the brain. Front Oncol 2018,8:161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hong S, Tan M, Wang S et al. Efficacy and safety of angiogenesis inhibitors in advanced non‐small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2015;141:909–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nakagawa K, Garon EB, Seto T et al.; RELAY Study Investigators . Ramucirumab plus erlotinib in patients with untreated, EGFR‐mutated, advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer (RELAY): A randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:1655–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han B, Li K, Wang Q et al. Effect of anlotinib as a third‐line or further treatment on overall survival of patients with advanced non‐small cell lung cancer: The ALTER 0303 phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:1569–1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Garon EB, Ciuleanu TE, Arrieta O et al. Ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel for second‐line treatment of stage IV non‐small‐cell lung cancer after disease progression on platinum‐based therapy (REVEL): A multicentre, double‐blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2014;384:665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sun Y, Niu W, Du F et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and antitumor properties of anlotinib, an oral multi‐target tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced refractory solid tumors. J Hematol Oncol 2016;9:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplemental Appendices

Supplemental Tables