Abstract

Background:

AKI after pediatric liver transplantation is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. The role of urinary biomarkers for the prediction of AKI in pediatric patients after liver transplantation has not been previously reported. The primary objective of this prospective pilot study was to determine the predictive capabilities of urinary KIM-1, NGAL, TIMP-2, and IGFBP7 for diagnosing AKI.

Methods:

Sixteen children undergoing liver transplantation were enrolled in the study over a 19-month time period. The Kidney Disease Improving Outcomes criteria for urine output and serum creatinine were used to define AKI. Predictive ability was evaluated using the area under the curve obtained by ROC analysis.

Results:

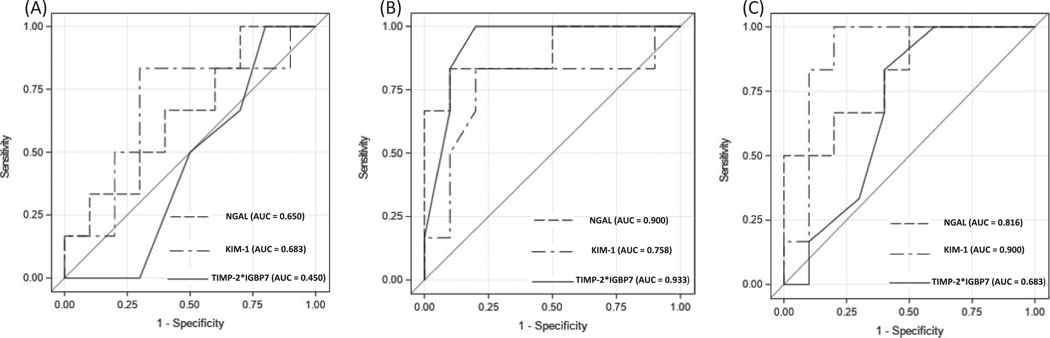

AKI occurred in 6 (37.5%) of the patients between 2 and 4 days after transplant. There were no differences in any of the biomarkers prior to transplant. When obtained within 6 hours after transplant, the area under the ROC curve for predicting AKI was 0.758 (95% CI: 0.458–1.00) for KIM-1, 0.900 (95% CI: 0.724–1.00) for NGAL, and 0.933 (95% CI: 0.812–1.00) for the product of TIMP-2 and IGFBP7 ([TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7]).

Conclusions:

Our results show that both NGAL and [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] provide significant discrimination for AKI risk following liver transplant in children. Larger studies are needed to determine the optimal time point for measuring these biomarkers and to validate our findings.

Keywords: kidney disease, liver transplantation, pediatrics, tubular biomarkers

1 |. INTRODUCTION

AKI is a rapid loss of kidney function and AKI following LTx adversely affects outcomes. In adult transplant recipients, the incidence of AKI ranges from 17% to 95%, with severe AKI requiring renal replacement therapy developing in 5%-35%.1 Likewise, AKI after pediatric LTx is common with investigators reporting incidence rates ranging from 28% to 57% based on differing criteria used to define AKI.2–4 Consistent with what is shown in other patient groups, AKI after pediatric LTx is associated with a significantly longer duration of mechanical ventilation, an increased hospital length of stay, and an increased risk of mortality.3,4 Furthermore, AKI is a well-known risk factor for the development of chronic kidney damage and longitudinal studies have demonstrated the presence of renal insufficiency in a substantial proportion of the LTx population, including children.5,6 The standard biomarker to asses AKI in children is serum creatinine; however, serum creatinine is commonly recognized to be a late and insensitive marker of AKI with changes often not apparent until 48–72 hours after injury.7 Therefore, improved detection of AKI in the perioperative period would have both short- and long-term benefits, reducing perioperative morbidity with appropriate management and lowering the incidence of chronic kidney disease development.

Newer markers of kidney injury including urinary NGAL and KIM-1 have demonstrated utility for early AKI prediction in subsets of pediatric populations, particularly in patients after cardiopulmonary bypass,8–10 with NGAL effectiveness being reported in adult LTx recipients.11–13 Most recently, the combination of two biomarkers of cell cycle arrest, TIMP-2 and IGFBP7, has become available for clinical use for predicting AKI in patients 21 years of age or older. The product of these two biomarkers (([TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7]) has been shown to be superior to other biomarkers for the prediction of AKI in adults.14,15 Ultimately, pediatric studies on the utility of NGAL, KIM-1, TIMP-2, or IGFBP7 (together or in combination) for predicting AKI in children are limited and no studies to date explore their use in pediatric LTx patients who are uniquely positioned to develop AKI.16–18

There is known variability among biomarker performance based on age and diagnosis.19 Therefore, our primary study objective was to determine the role of urinary IGFBP7, TIMP-2, NGAL, and KIM-1 in the diagnosis of AKI in pediatric LTx patients in the perioperative period.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Study design and participants

This prospective cohort study included patients under 18 years who underwent a first-time orthotopic LTx at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh between December 1, 2016 and July 30, 2018. Patients receiving renal replacement therapy at the time of transplant or whose diagnosis was associated with extra-hepatic renal involvement were excluded. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Health Sciences Research at the University of Pittsburgh (PRO15110488). Demographic and past medical history variables were collected along with baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate and intra- operative blood pressures. Baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated from the Schwartz Equation20 Perioperative variables included estimated blood loss, intravenous fluid volume administration, intraoperative lactate, need for ionotropic support, and perioperative nephrotoxic medication exposure (Table S1). For patients less than 12 years of age, the PELD score was calculated,21 and for patients 12 years of age or greater, the MELD score was determined.22 Using daily serum creatinine and continuous urine output monitoring for the first seven days following transplant, AKI was defined according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes criteria.23 The baseline serum creatinine was defined as the value obtained on all patients within 12 hours prior to LTx.

2.2 |. Urine biomarker collection and processing

At least 30 mL of urine was collected on all study participants for biomarker quantification preoperatively, within six hours after transplant, and 24 hours after transplant. Samples were centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 minutes, and the supernatants were stored in a −20°C freezer until analysis. The product of TIMP-2 and IGFBP7 ([TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7]) was measured with the NephroCheck™ Test (Astute Medical). Urine values for KIM-1 and NGAL (Millipore) were measured according to the manufacturers protocol.

2.3 |. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as median, percentage, or interquartile range. Differences between AKI and non-AKI patients were determined using the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Chi-Squared test, or Fisher’s exact test. ROC curves were generated with 95% CI at three time points to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of each biomarker. A two-sided P-value of .05 was used to indicate statistical significance. The analysis was done using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute).

3 |. RESULTS

During this 19 month period of the study, 38 pediatric patients underwent LTx at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. Two patients were excluded from the study because of the need for renal replacement therapy leading up to LTx. Two patients were excluded given renal involvement of their disease process (autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease, n = 1, and methyl malonic acidemia, n = 1). Thus, there were 34 eligible subjects of whom 17 were enrolled. One subject did not have adequate urine collection leaving 16 subjects included and enrolled in the study. The median age (IQR) at LTx was 102 (23–177) months and 9 (56.2%) patients were male. The median estimated glomerular filtrate rate (IQR) was 168.97 (122.47–209.68) mL/min/1.73 m2. Six out of the 16 (37.5%) patients in the study met criteria for AKI (two with stage 1 and four with stage 2). Four of the patients met AKI criteria using both urine output and serum creatinine criteria, one with urine output alone and one with serum creatinine alone. All patients reached their maximal AKI stage between two and four days after LTx. When we defined the baseline serum creatinine as the lowest value up to 6 months prior to LTx, the median estimated glomerular filtration rate (IQR) was greater 198.81 (125.36–211.17) than when we defined the baseline creatinine as the value within 12 hours prior to surgery. Using serum creatinine values 6 months prior to LTx to define a baseline did not change the incidence of AKI or which patients met criteria for AKI. No patients had a prior diagnosis of chronic kidney disease. Two patients had a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus prior to transplant and one of these patients developed AKI. No patients required renal replacement therapy following LTx. Induction therapy consisted of either thymoglobulin or steroids. The post-operative immunosuppression regimen was per protocol consisting of tacrolimus initiation on post-operative day two with goal trough levels 10–12 ng/mL.

Table 1 summarizes the patient characteristics and perioperative variables based on the development of post-operative AKI. There was no statistically significant difference in the two groups regarding any of the demographic, baseline disease, or perioperative characteristics. Nephrotoxic medications exposure was common across all recipients with standardized antimicrobial and immunosuppressive medication administration. Ionotropic support was required for three study participants, two of whom developed AKI. No patients had documented intraoperative hypertension.24 Neither hospital length of stay (24.2 days vs 25.7 days, P = .8) nor duration of mechanical ventilation (1.5 days vs 2.7 days, P = .3) differed between those who developed AKI vs those who did not.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristicsa | AKI (n = 6) | No AKI (n = 10) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (mo) | 114 (23–192) | 102 (24–144) | .63 |

| Males | 4 (66.7) | 2 (20) | .51 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 21.44 (17.23–23.04) | 18.47 (16.34–20.00) | .19 |

| Pretransplant disease baseline | |||

| eGFRb (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 137.84 (135.09–203.75) | 198.82 (118.27–211.66) | .95 |

| Primary liver diagnosis | |||

| Biliary | 4 (66.7) | 6 (60.0) | .72 |

| Metabolic | 2 (33.3) | 3 (30.0) | |

| Other (hepatoblastoma) | 0 (0) | 1 (10.0) | |

| MELD score | 14 (12–18) | 8.5 (7–10) | .22 |

| PELD score | 33 (7.5–41) | 15 (0–22) | .28 |

| Perioperative variable | |||

| Intraoperative lactate (mg/dL) | 4.05 (2.10–8.50) | 1.90 (0.8–4.10) | .17 |

| Estimated operative blood loss (mL/kg) | 16.3 (7.3–25.2) | 16.6 (4.1–40.2) | .97 |

| Intraoperative fluid administration (mL/kg) | 164.0 (112.9–263.1) | 210.9 (58.6–339.3) | .42 |

Data expressed as median (interquartile range) or N (%).

Based on the Schwartz Equation.20

There were no significant differences when comparing patients who ultimately developed AKI vs patients who did not for any biomarker before surgery (Table 2). Conversely, both NGAL and [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] showed significant differences when obtained within six hours after transplant. KIM-1 values also differed significantly when comparing patients who did and did not develop AKI when obtained 24 hours after transplant. Figure 1 shows the area under the ROC curves for each of the biomarkers when obtained prior to transplant, within 6 hours after transplant, and 24 hours post-operatively. When obtained within 6 hours after transplant the area under the ROC curve was 0.758 (95% CI: 0.458–1.00) for KIM-1, 0.900 (95% CI: 0.724–1.00) for NGAL, 0.933 (95% CI: 0.812–1.00) for [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7], and 0.625 (95% CI: 0.313–0.936) for serum creatinine. The area under the ROC curves for the biomarkers obtained 24 hours after transplant were 0.900 (95% CI: 0.729–1.00) for KIM-1, 0.816 (95% CI: 0.594–1.00) for NGAL, and 0.683 (95% CI: 0.414–0.954) for [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7].

TABLE 2.

Biomarkers when comparing subject groups

| Biomarkers | AKIa (n = 6) | No AKIa (n = 10) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| KIM-1 (pg/mL) | |||

| Prior to transplant | 251.53 (238.00–267.80) | 208.45 (198.70–249.00) | .27 |

| Within 6 h after transplant | 300 (260.00–315.00) | 217.50 (199–249.00) | .12 |

| 24 h after transplant | 629.15 (526.89–667.89) | 235.00 (200.40–324.00) | .02 |

| NGAL (ng/mL) | |||

| Prior to transplant | 8.73 (5.68–14.29) | 6.41 (2.98–10.47) | .37 |

| Within 6 h after transplant | 190.12 (125.75–263.12) | 40.74 (18.90–71.03) | .02 |

| 24 h after transplant | 71.33 (48.90–89.90) | 42.44 (17.03–50.90) | .06 |

| [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] | |||

| Prior to transplant | 0.25 (0.20–0.40) | 0.25 (0.10–0.40) | .78 |

| Within 6 h after transplant | 0.90 (0.70–0.90) | 0.36 (0.20–0.50) | .01 |

| 24 h after transplant | 0.40 (0.31–0.50) | 0.30 (0.20–0.50) | .22 |

Bold: P-value < .05.

Median (interquartile range).

FIGURE 1.

ROC curves for the prediction of AKI. A, Prior to LTx; B, Within 6 hours after LTx; C, 24 h after LTx

4 |. DISCUSSION

We report for the first time on the feasibility and utility of the use of novel biomarkers NGAL, KIM-1, TIMP-2, and IGBP7 for the detection of AKI in pediatric LTx recipients. The incidence of AKI of 37.5% in our patient cohort is similar to what has been shown in previous studies.2–4 Patients that were diagnosed with AKI were diagnosed between days 2 and 4, and hence, more than 24 hours passed before AKI could be diagnosed using standard clinical criteria with serum creatinine. Our study results show NGAL and [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] are good predictors of AKI when measured within 6 hours after surgery. KIM-1 also predicted AKI but did not become significant until 24 hours.

A serum creatinine is the standard laboratory value followed after pediatric LTx. However, serum creatinine is insensitive for identifying early kidney damage.7 In our cohort, serum creatinine obtained within 6 hours after LTx did not identify patients more likely to develop AKI (AUC = 0.625). Finding alternative methods to serum creatinine to aid in the prediction and prevention of overt AKI could significantly benefit children after LTx. An earlier knowledge of kidney injury or stress may help to guide clinicians making decisions regarding initiation and dosage of potentially nephrotoxic medications, such as a calcineurin inhibitor or anti- viral medication post-operatively. Nephrotoxic medications could be adjusted or avoided, and fluid status could be more appropriately tailored to prevent progression to or worsening of AKI and/or promote recovery.

As expected, we found no diagnostic utility of measuring any of the biomarkers prior to transplant. The post-operative areas under the ROC curves for NGAL and KIM-1 in our study were similar to those reported in previous non-LTx pediatric cohorts.10,25,26 When quantified 24 hours after surgery, the area under the ROC curve for KIM-1 was more robust when compared to values obtained 6 hours post-operatively (0.900 vs 0.758). Our results are consistent with prior study results that have shown an earlier increase in NGAL when compared to KIM-1.10

Although pediatric studies using urine TIMP-2 and IGFB7 levels are limited, [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] results are similar when comparing adults to children. In a case-control study of 51 children undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass, Meersch et al16 found an area under the ROC 0.85 (CI: 0.72–0.94). Our study results show a median (IQR) [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] value of 0.9 (0.7–0.9) in patients with AKI within 6 hours after transplant. Interestingly, Meersch et al report similarly high area under the curve values for NGAL and [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] and a lower value for KIM-1 measured 4 hours after cardiopulmonary bypass. Similarly, [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] values may decrease rapidly after kidney injury has manifested if additional exposures do not occur because neither TIMP-2 nor IGFBP7 require gene transcription to be released.27,28 In other words, both molecules are preformed and can be expressed rapidly after an injurious (or even noxious) stimulus.27

None of the preoperative patient characteristics differed when we compared patients that developed AKI to those that did not. However, there was a trend toward higher intraoperative lactate values, MELD Scores, and PELD Scores in the patients that developed AKI. It is possible that we did not detect the differences due to our small sample size. Interestingly, the mean baseline estimated glomerular filtrate rate of the patient cohort appears elevated, suggestive of possible glomerular hyperfiltration. In patients with diabetes and hypertension, for example, glomerular hyperfiltration is thought to be a possible early marker of renal dysfunction.29,30

While this work represents the first study to specifically explore the use of NGAL, KIM1, and cell cycle arrest biomarkers for the prediction of AKI in pediatric patients after liver transplantation, we recognize several limitations. A small sample size and the single center approach suggest the need for validation in larger, multi-center populations. Monitoring patients for only 7 days post-LTx may not have captured all variables which contribute to ongoing renal injury in this group. Additionally, serum creatinine was not corrected for fluid overload, which has been shown in prior studies in other patient groups to increase the sensitivity for detecting AKI.31,32 However, a notable strength of the study is the prospective design which enabled access to urine output and serum creatinine values for 7 days after transplant as well as preoperative serum creatinine values in all patients. We note that even the lower bounds of the 95% CI for the area under the ROC curves for NGAL and [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] were 0.724 and 0.812, respectively, at 6 hours following surgery. Thus, it is likely that these markers will show clinically relevant performance.

In conclusion, when measured as early as six hours after pediatric LTx NGAL and [TIMP-2]·[IGFBP7] can predict subsequent development of AKI manifesting over the next 2–4 days. Future efforts to expand on these initial findings will benefit transplant recipients and care teams, enabling more careful monitoring of AKI and earlier intervention to prevent its progression. Ultimately, improvements in the field of perioperative kidney injury, a well-recognized comorbidity and confounder, will be reflected in an improvement of outcomes following pediatric liver transplantation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alexis Rzempoluch for the coordination of the study. We would also like to thank Vanessa Jackson and the Clinical Research, Investigation, and Systems Modeling of Acute Illness (CRISMA) Center Laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh for processing the urine samples.

Funding information

This work was supported by a Hillman Innovation Development Award to JES by the Transplantation Program at the UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and the Hillman Foundation.

JAK discloses grant support and consulting fees from Astute Medical.

Abbreviations:

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- AUC

area under the curve

- CI

confidence intervals

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- IGFBP7

insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7

- KIM-1

kidney injury molecule-1

- LTx

liver transplant

- MELD

model for end-stage liver disease

- NGAL

neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin

- PELD

pediatric end-stage liver disease

- ROC

receiver-operator characteristic

- TIMP-2

tissue inhibitor of meta lloproteinases-2

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

DYF, ELJ, YM, GVM, AG, and JES report no relevant conflicts.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barri YM, Sanchez EQ, Jennings LW, et al. Acute kidney injury following liver transplantation: definition and outcome. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamada M, Matsukawa S, Shimizu S, et al. Acute kidney injury after pediatric liver transplantation: incidence, risk factors, and association with outcome. J Anesth. 2017;31:758–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sahinturk H, Ozdemirkan A, Zeyneloglu P, et al. Early postoperative acute kidney injury among pediatric liver transplant recipients. Exp Clin Transplant. 2019. 10.6002/ect.2018.0214 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nahum E, Kadmon G, Kaplan E, et al. Prevalence of acute kidney injury after liver transplantation in children: comparison of the pRI-FLE, AKIN, and KDIGO criteria using corrected serum creatinine. J Crit Care. 2019;50:275–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Israni AK, Xiong H, Liu J, et al. Predicting end-stage renal disease after liver transplant. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:1782–1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell KM, Yazigi N, Ryckman FC, et al. High prevalence of renal dysfunction in long-term survivors after pediatric liver transplantation. J Pediatr. 2006;148:475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waikar SS, Bonventre JV. Creatinine kinetics and the definition of acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:672–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parikh CR, Coca SG, Thiessen-Philbrook H, et al. Postoperative biomarkers predict acute kidney injury and poor outcomes after adult cardiac surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1748–1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng J, Xiao Y, Yao Y, et al. Comparison of urinary biomarkers for early detection of acute kidney injury after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery in infants and young children. Pediatr Cardiol. 2013;34:880–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krawczeski CD, Goldstein SL, Woo JG, et al. Temporal relationship and predictive value of urinary acute kidney injury biomarkers after pediatric cardiopulmonary bypass. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2301–2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagener G, Minhaz M, Mattis FA, et al. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a marker of acute kidney injury after orthotopic liver transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1717–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sirota JC, Walcher A, Faubel S, et al. Urine IL-18, NGAL, IL-8 and serum IL-8 are biomarkers of acute kidney injury following liver transplantation. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hryniewiecka E, Gala K, Krawczyk M, et al. Is neutrophil gelatinase- associated lipocalin an optimal marker of renal function and injury in liver transplant recipients? Transplant Proc. 2014;46:2782–2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bihorac A, Chawla LS, Shaw AD, et al. Validation of cell-cycle arrest biomarkers for acute kidney injury using clinical adjudication. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:932–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoste EA, McCullough PA, Kashani K, et al. Derivation and validation of cutoffs for clinical use of cell cycle arrest biomarkers. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29:2054–2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meersch M, Schmidt C, Van Aken H, et al. Validation of cell-cycle arrest biomarkers for acute kidney injury after pediatric cardiac surgery. PLoS ONE One. 2014;9:e110865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westhoff JH, Tonshoff B, Waldherr S, et al. Urinary tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 (TIMP-2) * insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) predicts adverse outcome in pediatric acute kidney injury. PLoS ONE One. 2015;10:e0143628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gist KM, Goldstein SL, Wrona J, et al. Kinetics of the cell cycle arrest biomarkers (TIMP-2*IGFBP-7) for prediction of acute kidney injury in infants after cardiac surgery. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32:1611–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett MR, Nehus E, Haffner C, et al. Pediatric reference ranges for acute kidney injury biomarkers. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30:677–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz GJ, Munoz A, Schneider MF, et al. New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:629–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDiarmid SV, Anand R, Lindblad AS, et al. Development of a pediatric end-stage liver disease score to predict poor outcome in children awaiting liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;74:173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamath PS, Kim WR,Advanced Liver Disease Study Group. The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD). Hepatology. 2007;45:797–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.KDIGO Board Members. Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2012;2:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, et al. Clinical practice guide-line for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20171904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Filho LT, Grande AJ, Colonetti T, et al. Accuracy of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin for acute kidney injury diagnosis in children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32:1979–1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mishra J, Dent C, Tarabishi R, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a biomarker for acute renal injury after cardiac surgery. Lancet. 2005;365:1231–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emlet DR, Pastor-Soler N, Marciszyn A, et al. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 and tissue inhibitor of metalloprotein-ases-2: differential expression and secretion in human kidney tubule cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017;312:F284–F296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson ACM, Zager RA. Mechanisms underlying increased TIMP2 and IGFBP7 urinary excretion in experimental AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:2157–2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magee GM, Bilous RW, Cardwell CR, et al. Is hyperfiltration associated with the future risk of developing diabetic nephropathy? A meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2009;52:691–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmieder RE, Veelken R, Schobel H, et al. Glomerular hyperfiltration during sympathetic nervous system activation in early essential hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:893–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basu RK, Andrews A, Krawczeski C, et al. Acute kidney injury based on corrected serum creatinine is associated with increased morbidity in children following the arterial switch operation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:e218–e224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu KD, Thompson BT, Ancukiewicz M, et al. Acute kidney injury in patients with acute lung injury: impact of fluid accumulation on classification of acute kidney injury and associated outcomes. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:2665–2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.