Abstract

Background and Aims

Pollen tube growth rate (PTGR) is an important single-cell performance trait that may evolve rapidly under haploid selection. Angiosperms have experienced repeated cycles of polyploidy (whole genome duplication), and polyploidy has cell-level phenotypic consequences arising from increased bulk DNA amount and numbers of genes and their interactions. We sought to understand potential effects of polyploidy on several underlying determinants of PTGR – pollen tube dimensions and construction rates – by comparing diploid–polyploid near-relatives in Betula (Betulaceae) and Handroanthus (Bignoniaceae).

Methods

We performed intraspecific, outcrossed hand-pollinations on pairs of flowers. In one flower, PTGR was calculated from the longest pollen tube per time of tube elongation. In the other, styles were embedded in glycol methacrylate, serial-sectioned in transverse orientation, stained and viewed at 1000× to measure tube wall thicknesses (W) and circumferences (C). Volumetric growth rate (VGR) and wall production rate (WPR) were then calculated for each tube by multiplying cross-sectional tube area (πr2) or wall area (W × C), by the mean PTGR of each maternal replicate respectively.

Key Results

In Betula and Handroanthus, the hexaploid species had significantly wider pollen tubes (13 and 25 %, respectively) and significantly higher WPRs (22 and 18 %, respectively) than their diploid congeners. PTGRs were not significantly different in both pairs, even though wider polyploid tubes were predicted to decrease PTGRs by 16 and 20 %, respectively.

Conclusions

The larger tube sizes of polyploids imposed a substantial materials cost on PTGR, but polyploids also exhibited higher VGRs and WPRs, probably reflecting the evolution of increased metabolic activity. Recurrent cycles of polyploidy followed by genome reorganization may have been important for the evolution of fast PTGRs in angiosperms, involving a complex interplay between correlated changes in ploidy level, genome size, cell size and pollen tube energetics.

Keywords: Betula, cell size, evolution of development, genome size, Handroanthus, male gametophyte, nucleotype, plant reproduction, pollen tube growth rate, polyploidy, whole genome duplication

INTRODUCTION

In angiosperms, the fertilization process is mediated by the growth of a pollen tube, a tip-growing cell that carries sperm from stigma to ovule. The growth rate of pollen tubes (PTGR) is an important aspect of male fitness, because eggs are receptive for a limited time period after pollination (Palser et al., 1989; Sanzol and Herrero, 2001) and because pollen tubes compete for access to eggs. Angiosperms have evolved orders-of-magnitude faster PTGRs than gymnosperms (Williams, 2008; Reese and Williams, 2019), a pattern thought to have arisen rapidly because of the effectiveness of natural or sexual selection on the many haploid, gametophytically expressed genes that determine PTGR (Mulcahy, 1979; Walsh and Charlesworth, 1992; Arunkumar et al., 2013; Hafidh et al., 2016; Immler 2019). Yet, it now seems likely that angiosperm pollen tube growth rates have often evolved at diploid or higher levels, as angiosperms have high levels of ancient whole genome duplications (WGDs) (Jiao et al., 2011; Landis et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2018) and present-day polyploidy (Wood et al., 2009; Mayrose et al., 2011) compared to gymnosperms (Leitch and Leitch, 2012). Polyploidy is known to have both immediate and ongoing consequences on cell structure and function, but its effects on cell growth rates, and particularly on PTGR, are not well understood.

It is well known that nuclear size, cell size and cell cycle duration are positively correlated with bulk nuclear DNA amount (Bennett, 1971, 1972; Price et al., 1973; Shuter et al., 1983; Cavalier-Smith, 1985; Beaulieu et al., 2008), even if the mechanisms for such relationships have been elusive (Gregory, 2001; Cavalier-Smith, 2005; Doyle and Coate, 2019). Cell growth rate is usually negatively correlated with bulk nuclear DNA amount, at least when ‘growth rate’ represents the rate of increase in cell numbers or in cell sizes, averaged over whole cell cycles, in multicellular tissues or populations of single-celled organisms (Schuter, 1983; Robinson et al., 2018; D’Ario and Sablowski, 2019). The volumetric growth rates (VGRs) of individual cells within a single growth phase of the cell cycle have rarely been measured (Gregory, 2001; Šímová and Herben, 2012; Doyle and Coate, 2019).

Most plant cells enlarge by diffuse growth, in which cell wall construction occurs simultaneously across the entire expanding plasma membrane surface (Albersheim et al., 2011). In cells with diffuse growth, the construction rate of the cell wall (via the processes of secretion, synthesis and wall assembly) is somewhat decoupled from cell growth rate (Cosgrove, 2018). Cell walls can be overproduced before cells expand, or become thickened and reinforced after maturity. The actual speed of cell expansion is driven more by import rates of solutes into the vacuole and by wall stress relaxation, rather than by the actual construction rate of new wall.

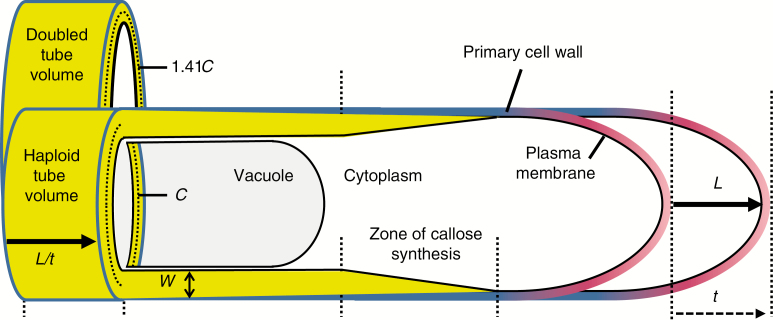

In contrast, tubular root hairs and pollen tubes elongate by tip-growth, in which the rate of new cell wall production is causally linked to the rate of cell expansion (Winship et al., 2010, 2011). As shown in Figure 1, tip-growth of pollen tubes occurs only at the apex, maintained by a short zone of active wall synthesis of constant size (Chebli et al., 2012). The angiosperm pollen tube is a terminally differentiated cell, with an active tube nucleus and exceptionally high metabolic rates (Rounds et al., 2011; Colaço et al., 2012; Obermeyer et al., 2013; Selinski and Scheibe, 2014; Chen et al., 2018). Pollen tube diameter and wall thickness are determined at the growing tube tip (Fayant et al., 2010; Geitmann, 2011; Sanati Nezhad et al., 2013) and remain constant during growth (Lancelle and Hepler, 1992; Williams et al., 2016; Rabillé et al., 2019). Tube shank walls are seen as being near their minimal thickness to function in resisting turgor pressure and compression stress (Benkert et al., 1997; Parre & Geitmann, 2005; Hu et al., 2017).

Fig. 1.

Measuring dimensions and growth rates of pollen tubes. Because circumference, C, and wall thickness, W, are constant over time, pollen tube growth rate (PTGR) can be measured as an increase in length, L over time, t. The synthesis of new plasma membrane and primary cell wall near the tip, and the subapical zone of secondary callose wall synthesis, track the forward movement of the tip, as does the leading edge of the elongating vacuole. As a result, total wall production rate, WPR, can be measured in mature tubes by multiplying circumference, C, by wall thickness, W, and PTGR. Because functional cytoplasm must be maintained between the elongating vacuole and tube tip, a doubling of cytoplasm volume after a whole genome duplication should cause up to a doubling of tube volume per unit of length, which results when tube diameter or circumference are increased by 41.4 %. Doubled tube volume doubles the volumetric growth rate (VGR) and requires a 41.4 % increase in WPR, if W and PTGR are held constant. Figure is not to scale.

It is not so clear how genome size and pollen tube cell size are correlated, because a pollen tube only functions while cell volume is increasing. However, most of the functional cytoplasm in a pollen tube, which includes the tube nucleus, sperm cells and organelles, is confined to a volume of roughly constant size between the leading edge of the advancing tube vacuole and the elongating tip (Hepler and Winship, 2015). If the volume of functional cytoplasm is proportional to genome size, as often reported for many different types of cells (Gregory, 2001; Cavalier-Smith, 2005; Chevalier et al., 2014), then in a polyploid pollen tube, either the distance between the tube tip and vacuole or the tube diameter must increase (Fig. 1). Pollen tubes of allotetraploid Nicotiana rupa were 39 % larger in diameter relative to the mean of its presumed diploid progenitors (Kostoff & Prokofieva, 1935), and pollen tubes from unreduced (2n) vs. reduced (n) pollen of Rosa hybrida individuals were more than 30 % wider (Gao et al., 2019). These values approach the 41 % increase in tube diameter or circumference needed to double the volume of the functional cytoplasm by altering only tube width (Fig. 1).

Dimensional correlates of genome size, such as larger tube size, impose higher construction costs, because more time and energy are required to synthesize more wall material per unit of length. If the rate of work stays the same, widening of the pollen tube will cause a decrease in the rate of elongation (tube length per unit of time, PTGR) (Williams et al., 2016). When genome size increase occurs by polyploidy, these higher materials costs could be offset by higher cell metabolic rates, as a result of higher gene dosage, greater sheltering of deleterious recessives and/or heterotic effects (Lande and Schemske, 1985; Birchler et al., 2010; Conant et al., 2014). Faster rates of work would be reflected in increased volume of solutes imported per unit of time (VGR) and faster plasma membrane and cell wall production (wall production rate, WPR) (Fig. 1). As such, higher materials costs might be offset by faster work rates, and one might predict conservation of PTGR in neo-polyploids.

Previous studies in intraspecific polyploids found that PTGRs of diploid pollen tubes of autotetraploids (2x pollen tube in 4x style) were consistently slower than those of haploid pollen tubes of their diploid progenitors (1x pollen tube in 2x style) (see Reese and Williams, 2019). Such studies assumed the cause of slower PTGRs in polyploids was related to their generally larger in vivo tube cell sizes (Kostoff & Prokofieva, 1935; Iyengar, 1938). On the other hand, a large phylogenetic comparative analysis found that stabilized neo-polyploid species, defined as having more than two chromosome sets relative to the base monoploid (1x) count in their genus (Wood et al., 2009), have often evolved faster PTGRs than their diploid (2x) relatives (Reese and Williams, 2019). No study has yet been designed to understand cell-level consequences of polyploidy on the evolution of PTGRs.

In this study, we compare closely related diploid–polyploid pairs within Betula (Betulaceae) and Handroanthus (Bignoniaceae). Both groups are woody perennials, but PTGRs in Handroanthus are about two orders of magnitude faster than in Betula. First, we investigate if there are differences between related diploids and polyploids in tube wall thicknesses, tube circumferences and PTGRs. Next, we use these measurements to quantify differences in VGR and WPR. Ultimately, we show that polyploids have similar PTGRs as their diploid relatives, but that this similarity arises as a consequence of both larger pollen tubes and faster WPRs and VGRs. Our comparative method will be useful for understanding the mechanistic aspects of PTGR evolution at any stage of diploid–polyploid divergence, from artificial or natural ancestor–descendant pairs to deeper divergences such as studied here.

METHODS

The species

In Betula (Betulaceae), B. occidentalis Hooker (2n = 2x = 28) ranges from northern New Mexico, USA, to central British Columbia, Canada. It frequently hybridizes with B. papyrifera Marsh. (2n = 6x = 84) in western North America (Williams and Arnold, 2001) and the species are closely related (Wang et al., 2016). Both species are monoecious, self-sterile and wind-pollinated (Williams, 2000). Intraspecific crosses were carried out in two parental populations in the Black Hills of South Dakota, 43.99°N, 103.40°W for B. occidentalis and 43.82°N, 103.55°W for B. papyrifera (Williams, 2000). To control for temperature effects, a similar number of crosses were made on each species each day and time of day (28 May to 3 June 1997). Each pollination was done with a multiple pollen donor mix by blowing pollen onto one female catkin (inflorescence with densely packed flowers) to simulate wind-pollination (N = 10 and 7 maternal plants for B. occidentalis and B. papyrifera, respectively).

Another genus of closely related woody perennials, Handroanthus (Bignoniaceae; Grose and Olmstead, 2007), was studied in Uberlândia, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Handroanthus ochraceus (Cham.) Mattos (2n = 2x = 40) and Handroanthus serratifolius (Vahl) S.O.Grose (2n = 6x = 120) are widely distributed in the Central Brazilian Cerrados, and trees in this study were sexual and completely self-sterile (Alves et al., 2013; Mendes et al., 2018). Handroanthus chrysotrichus (Jacq.) S.O.Grose (2n = 4x = 80) is putatively native to the Atlantic forest, and it is a self-fertile and sporophytic apomictic tree (Bittencourt and Moraes, 2010) cultivated in Uberlândia. All three have bright yellow, hermaphroditic, bee-pollinated flowers (Bittencourt and Moraes, 2010; Alves et al., 2013). Intraspecific crosses involved hand-pollinations using at least two pollen donors onto N = 2 maternal plants for each species (N = 3 for H. ochraceous). All crosses were done in the morning when the flowers were fully open, at temperatures near 20 °C.

Microscopy

Pollinated pistils were fixed in 3 : 1 [glacial acetic acid/distilled H2O (dH2O)] about 48 h after pollination (hap) in Betula (range : 43.5–49.2 hap), or in FAA (formaldehyde, glacial acetic acid and 70 % EtOH, 5 : 5 : 90) in Handroanthus, and stored in 70 % EtOH. Adjacent pairs of flowers where then treated separately as follows. In one set, whole mounts were prepared by splitting the style longitudinally (Handroanthus), or by softening styles in 8 m NaOH at 60 °C for 6 h, rinsing three times in dH2O (Betula), and then staining overnight with 0.1 % aniline blue in 0.1 m K3PO4 with 5 % added glycerol. Styles were viewed and photographed at 100× or 200× magnification under fluorescence using a modified Zeiss filter set (model no. 48702): excitation filter (365 nm, band pass 12 nm), dichroic mirror (FT395) and barrier filter (LP520) on a Zeiss Axioplan II light microscope.

In the second set, styles were dehydrated to 95 % ethanol, and then infiltrated and embedded in glycol methacrylate (JB-4 polymer; Polysciences, Warrington, PA, USA). Blocks were serial-sectioned (5 µm thick) perpendicular to the pollen tube pathway with glass knives on a Sorvall Dupont JB-4 microtome (Newtown, CT, USA). Mounted serial sections were stained overnight with 0.025 mg mL−1 aniline blue fluorochrome in dH2O (Stone et al., 1984; BioSupplies Australia, Bundoora, Australia) and then flooded with a 0.1 % aqueous solution of Calcofluor white M2R (Sigma 3543) for 0.5 h, lightly rinsed in dH2O and mounted in Permount (Fisher) while ribbons were still slightly moist (O’Brien and McCully, 1981). Slides were stored at 8 °C and viewed 24–48 h after first staining with the fluorescent filter set above.

Microphotography was done using a Zeiss Plan-neofluar 100× NA 1.30 oil objective on a Zeiss Axioplan II light microscope with a Zeiss Axiocam HRc digital camera mounted on a 0.63× phototube, such that 1 pixel = 0.035236 µm2. All measurements were done on micrographs using Zeiss Axiovision v. 4.8.2 software. All five species were processed and viewed under the same conditions at the University of Tennessee (see Williams et al., 2016).

Measurements

To measure PTGR, the longest pollen tube in each style was measured from pollen grain to tube tip. In Betula, PTGR was determined as pollen tube length divided by the time from pollination to collection, minus 2 h to account for pollen germination. One pollen tube per each of ten styles (actual mean N = 9.8) was used to calculate a mean for each maternal plant. A different approach was used for the ~30-mm-long styles of Handroanthus. These were fixed at two or three time points after pollination. Pollen tubes were photographed in segments and measurements were summed for the longest pollen tube for each style, and then mean PTGR was calculated as the difference in mean pollen tube lengths between successive time points, divided by the duration of the time interval (ranging from 4.5 to 4.9 h).

Pollen tube dimensions were measured on tubes that were perpendicular to the plane of view. Sample size for Betula was N = 10.8 pollen tubes from 2.1 flowers per maternal plant and for Handroanthus 18.7 pollen tubes from three flowers per maternal plant. For each tube, wall thickness (W) was calculated as the mean of ten measurements along the thinnest portions of the wall, whereas circumference (C) was measured once, along the midpoints of wall width. In rare cases, slightly oblique tubes were used, and then outside diameter was measured instead, using the narrowest portion of the tube as representative of the true diameter, and then converting to C according to: C = (Dod − W) × π

Total cross-sectional wall area (WA) was calculated for each tube as:

All measurements of Betula tube circumferences and walls were done by J.H.W., and most Handroanthus tube walls by P.E.O. To determine the repeatability of measurements of C and W, each author measured C and W of the same 36 pollen tubes (18 from each species of Betula). Wall thicknesses measured by J.H.W. were on average 9.1 % thinner than those measured by P.E.O. (mean ± s.e. difference in W between blind trials was 0.0191 ± 0.0039 µm; matched pair test, P < 0.0001). Therefore, a minus 9.1 % correction factor was applied to the measurements of W by P.E.O. in Handroanthus. Circumferences of the same set of tubes were not significantly different (mean difference in C was 0.1014 ± 0.2061 µm; P = 0.62).

Total cross-sectional tube area (TA), for the inside diameter (Did) of each tube was calculated as:

WPR and VGR were calculated for each tube using mean PTGR of the maternal plant (Betula) or mean PTGR of the species (Handroanthus):

Statistics

For Betula, the response variables PTGR, W, C, TA and WA were log10-transformed and analysed by ANOVA [least squares (LS) and restricted maximum likelihood method) with Species as a fixed effect, and Maternal plant nested in Species and Flower nested in Maternal plant as random effects. ANCOVA was used to compare VGR and WPR among Betula species, using LS means of maternal plants and PTGR as the covariate. For Handroanthus, LS means for W, C, TA and WA were estimated as above but pollen tube lengths at each time point were pooled and the difference in mean length at each time point was calculated, resulting in a single PTGR estimate for each species. In Handroanthus, the species mean PTGR was multiplied by the LS mean WA for each maternal plant, and WPRs were compared by ANOVA as above. All statistics were done in JMP v. 14.0.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Betula

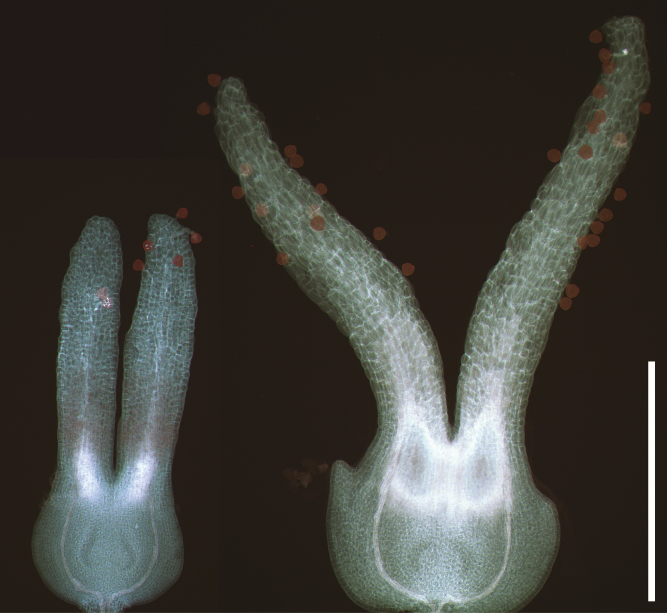

On average, fresh B. papyrifera pollen grain volume was 49 % larger than in B. occidentalis (8.31 × 103 µm3 vs. 5.56 × 103 µm3, respectively) (Williams et al., 1999). As shown in Fig. 2, styles were 22 % longer in B. papyrifera (970.5 ± 61.9 µm) compared to B. occidentalis (794.4 ± 53.0 µm) (R2adj = 0.7465; F1,75 = 4.6698, P = 0.0476; Maternal plant within Species, P = 0.0173).

Fig. 2.

Female flowers of Betula species 2 d after pollination. On left, B. occidentalis (2x) and on the right, B. papyrifera (6x). The ovary is undeveloped and contains two ovule primordia that mature 4–5 weeks later. Scale bar = 0.5 mm.

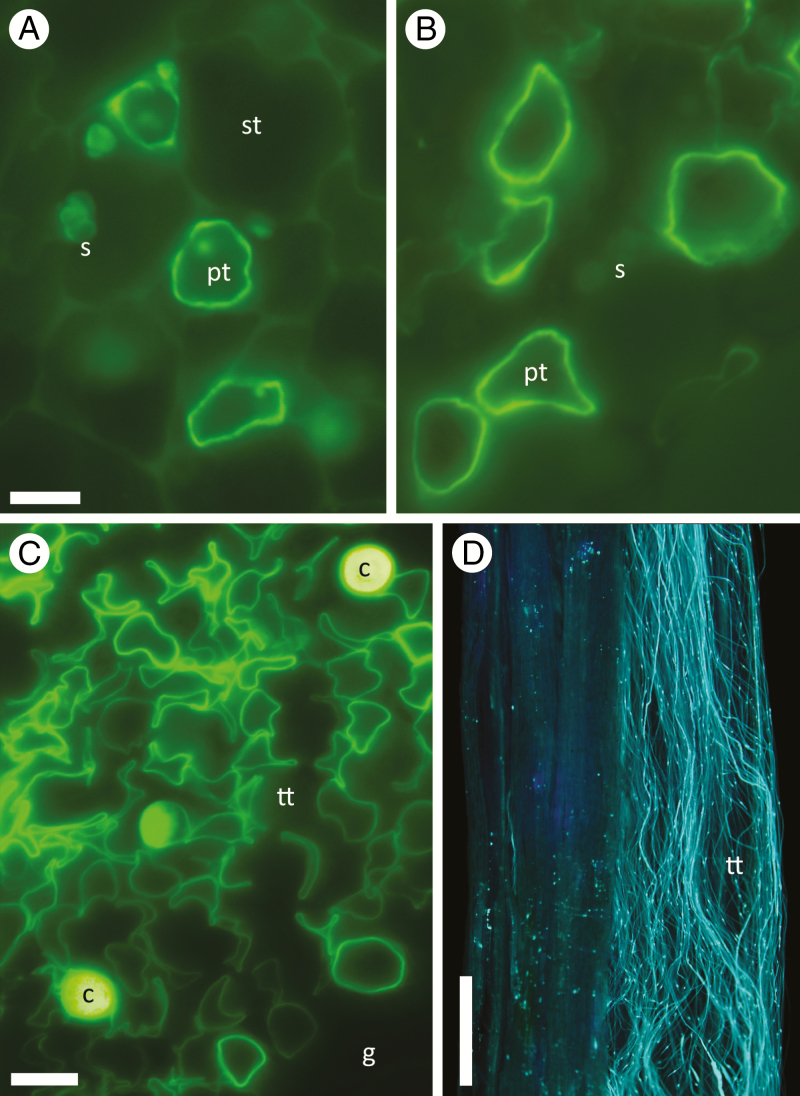

Pollen tubes of the 6x species (B. papyrifera) were 12.6 % larger in circumference than in the 2x species, B. occidentalis (P < 0.001), whereas tube walls were almost identical in thickness (P = 0.99; Table 1, Fig. 3A, B). As a result, the amount of wall material produced per unit of elongation (WA) was 13.1 % greater in the 6x than in the 2x species (P = 0.01; Table 1). Callose plugs were rare, but they displayed the same pattern of wider tubes in the 6x than in the 2x species (Table 1; N = 9 and 8 tubes averaged over five maternal plants each).

Table 1.

Estimates of pollen tube dimensions for Betula

| Species | W (µm) | C (µm) | C cp (µm) | W A (µm2) | T A (µm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. occidentalis (2x) | 0.2086 | 17.42 | 21.57 | 3.63 | 22.33 |

| {0.2003, 0.2173} | {16.72, 18.14} | {3.42, 3.84} | {20.53, 24.29} | ||

| B. papyrifera (6x) | 0.2085 | 19.60 | 23.91 | 4.10 | 28.53 |

| {0.1986, 0.2189} | {18.66, 20.59} | {3.83, 4.40} | {25.79, 31.56} | ||

| Model R2adj. | 0.25 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.52 | |

| P = 0.9867 | P = 0.0016 | P = 0.0122 | P = 0.0015 |

Wall thickness, W, circumference, C, wall area, WA, and tube area, TA, were each measured on the same pollen tubes. Circumference of callose plugs, Cp, is shown for comparison. Values are back-transformed, least-squares means with 95 % confidence intervals in curly brackets.

Fig. 3.

Pollen tube growth in Betula and Handroanthus. (A, B) Cross-sections of (A) haploid B. occidentalis (2x) and (B) triploid B. papyrifera (6x) pollen tubes (pt) growing between starch-bearing (s) stylar cells (st). (C) Cross-section of H. serratifolius (6x) secretory transmitting tissue (tt) showing many collapsing pollen tubes, and some callose plugs (c). Dark area is stylar ground tissue (g). (D) Longitudinal view of H. ochraceous (2x) pollen tubes with callose plugs in transmitting tissue of mid-style. All stained with aniline blue. Scale bars = A, B, 5 µm; C, 10 µm; D, 0.5 mm.

The 6x and 2x species had similar PTGRs of about 9–10 µm h−1 (P = 0.33; Table 2). However, the VGR of the 6x species was 23.3 % faster than that of the 2x species (P = 0.013) and the WPR of the 6x species was 12.3 % faster (P = 0.0010; Table 2), after controlling for PTGR. The interaction effect was non-significant (P = 0.146 and P = 0.332, respectively) and was dropped from both models. Finally, in both analyses the slopes of the log–log relationships between VGR and PTGR or WPR and PTGR were both <1, indicating that for every ten-fold increase in PTGR there was a ~8.2-fold increase in wall production and volumetric growth rates.

Table 2.

Pollen tube growth and wall production rates for Betula

| Species | PTGR (µm L h−1) | VGR (μm3 h−1) | WPR (µm3 h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| B. occidentalis (2x) | 9.95 | 216.09 | 34.46 |

| {8.63, 11.46} | {195.6, 238.73} | {33.00, 35.98} | |

| B. papyrifera (6x) | 8.95 | 266.55 | 38.69 |

| {7.56, 10.60} | {236.47, 300.46} | {36.73, 40.76} | |

| Model R2adj. | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.34 |

| P = 0.3258 | P = 0.0130 | P = 0.0010 |

PTGR, pollen tube growth rate; VGR, volumetric growth rate; WPR, wall production rate. VGR and WPR estimates are from ANCOVA with log10PTGR as the covariate in a same-slopes model. Values are back-transformed, least-squares means with 95 % confidence intervals in curly brackets.

Handroanthus

Mature pollen grains of the 6x and 4x species were 75 and 46 % larger in volume than in the 2x species, respectively (mean ± s.d. 6x = 27.68 ± 6.15 × 103 µm3, 4x = 23.11 ± 5.97 × 103 µm3, and 2x = 15.78 ± 10.15 × 103 µm3; N = 21 pollen grains per species, P < 0.0001). The 6x and 4x species of Handroanthus had 28 and 21 % longer styles than the 2x species, respectively (mean ± s.d. of 6x = 32.33 ± 2.18 mm, 4x = 30.05 ± 4.91 mm and 2x = 25.20 ± 3.43 mm; N =10, 10 and 9 styles; P = 0.0008).

Pollen tubes of H. serratifolius (6x) and H. chrysotrichus (4x) were 25.1 and 24.5 % larger in circumference than those of H. ochraceous (2x), respectively (P = 0.05), whereas tube walls were similar in thickness (P = 0.33; Table 3). The two polyploid species also had wider callose plugs than the 2x species (P = 0.028; Table 3, Fig. 3C, D). WA of the 6x and 4x species was slightly higher than that of the 2x species (24.7 and 8.2 % more wall material per μm of elongation, respectively; P = 0.10).

Table 3.

Estimates of pollen tube dimensions for Handroanthus

| Species | W (µm) | C (µm) | C cp (µm) | W A (µm2) | T A (µm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. ochraceous (2x) | 0.2596 | 20.20 | 19.19 | 5.25 | 29.87 |

| {0.2287, 0.2947} | {17.94, 22.75} | {16.86, 21.84} | {4.61, 5.98} | {23.27, 38.34} | |

| H. chrysotrichus (4x) | 0.2314 | 24.54 | 26.02 | 5.68 | 45.07 |

| {0.1978, 0.2706} | {21.16, 28.47} | {22.33, 30.32} | {4.82, 6.69} | {32.99, 61.58} | |

| H. serratifolius (6x) | 0.2595 | 25.27 | 24.33 | 6.54 | 47.58 |

| {0.222, 0.3034} | {21.81, 29.29} | {20.58, 28.75} | {5.56, 7.71} | {34.87, 64.9} | |

| Model R2adj. | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.53 | 0.21 | 0.40 |

| P = 0.3263 | P = 0.0539 | P = 0.0277 | P = 0.1030 | P = 0.0548 |

Wall thickness, W, circumference, C, wall area, WA, and tube area, TA, were each measured on the same pollen tubes. Circumference of callose plugs, Cp, is shown for comparison. Values are back-transformed, least-squares means with 95 % confidence intervals in curly brackets.

The 6x and 2x species had similar PTGRs, but the 6x species had faster VGR and WPR (Table 4). The apomictic 4x species had slower PTGR than the 2x species, and its WPR was significantly slower (Table 4).

Table 4.

Estimates of growth rates for Handroanthus

| Species | PTGR (×103 µm h−1) | VGR (×103 µm3 h−1) | WPR (×103 µm3 h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H. ochraceous (2x) | 1.717 | 51.293 | 9.011 |

| {41.684, 63.117} | {7.916, 10.261} | ||

| H. chrysotrichus (4x) | 1.104 | 49.792 | 6.273 |

| {38.621, 64.194} | {5.322, 7.393} | ||

| H. serratifolius (6x) | 1.617 | 76.944 | 10.585 |

| {59.681, 99.200} | {8.991, 12.462} | ||

| Model R2adj. | 0.68 | 0.58 | |

| P = 0.0447 | P = 0.0072 |

PTGR, pollen tube growth rate; VGR, volumetric growth rate; WPR, wall production rate. Values are back-transformed, least-squares means with 95 % confidence intervals in curly brackets.

DISCUSSION

The pollen tube is an excellent model for studying cell-level consequences of whole genome duplication because it is a single cell that functions during a single phase of the cell cycle and its elongation rate, PTGR, is determined entirely by the amount and rate of new tube cell wall production. In this study, we estimated the magnitude of differences in pollen tube energetics and dimensions on PTGRs between diploids and their polyploid relatives. Dimensional effects can evolve independently of the energetics that underlie wall construction rates – for example, species with similar PTGRs vary in how efficiently they elongate their tubes (Williams et al., 2016). In both Betula and Handroanthus, the polyploid species had larger mature pollen grains that in turn formed larger pollen tubes, and hence required synthesis of more wall material and importation of more solutes per unit of tube length. That added materials cost, calculated as the change in PTGR that would occur if a polyploid pollen tube produced its walls at the same rate as its haploid relative, imposed a 16–20 % penalty on PTGR. The tube-size effect was largely compensated for by faster wall construction rates in both hexaploid species, resulting in an apparent evolutionary stasis of PTGR. Our two diploid–hexaploid pairs, although closely related, are not ancestor–descendant pairs, and thus we consider both immediate and subsequent effects of WGD on PTGR traits.

Comparative aspects of pollen tube cell dimensions among diploids and polyploids

Tube walls of hexaploid and diploid species were very similar in thickness, despite differences in tube circumference. Other studies have also found very small differences in wall thickness between distantly related species despite variation in tube circumference, chromosome number and DNA content (Williams et al., 2016). Wall thickness is expected to vary as a function of turgor pressure, which is affected by the structure and osmolarity of the pollen tube pathway (Parre and Geitmann, 2005; Hu et al., 2017). In Betula, pollen tubes grew within solid transmitting tissue in both species (Fig. 3A, B), and in Handroanthus, within a relatively open secretory transmitting tissue among loosely arranged cells in all species (Fig. 3C, D). The similarities in tube wall thicknesses probably reflect similarities in pollen tube pathway structure.

The two hexaploid species in this study had wider tube circumferences than their diploid relatives. A pollen tube only functions during growth, maintaining a functional cytoplasm of more or less constant size at the tube apex. After WGD, a tube can accommodate more cytoplasm in the tip area by widening of the tube or by increasing the distance from the leading edge of the vacuole to the tube tip (Fig. 1). We were unable to measure the latter, but the tubes of hexaploids had 13–25 % larger C, and accommodated 28–59 % more volume per unit length (TA), than the diploids. Because wall thicknesses were similar among species pairs, differences in circumference were the main determinants of wall and tube volumes, WA and TA.

Divergence of phenotypic traits may have occurred during WGD or afterwards. There is some evidence that pollen tube sizes of diploid species have been stable since WGD. For example, Betula pendula (2n = 2x = 28) pollen tubes had a circumference of C = 17.6 ± 1.4 µm (N = 5; Dahl and Fredrickson, 1996), similar to C = 17.4 µm in diploid B. occidentalis. The size differences between haploid and triploid pollen tubes we observed probably evolved mostly during WGD rather than afterwards, because artificial neo-autopolyploids consistently have larger pollen tubes (and slower PTGRs) than their diploid progenitors (Kostoff and Prokofieva, 1935; Blakeslee, 1941; Modlibowska, 1945; Gao et al., 2019; Reese and Williams, 2019). Similarly, The 1C genome size of 19 diploid Betula species (all 2n = 28) has evolved very little variation (CV = 4.6 %), and has the same mean of 1C = 0.48 pg as B. occidentalis (Wang et al., 2016). Sperm nuclei of B. papyrifera were visibly larger than in B. occidentalis and the relative 1C DNA content of in situ sperm nuclei scaled 2.90 : 1.00, respectively (Williams et al., 1999), which is similar to the ratio of 3.06 : 1.00, measured by flow cytometry for the same species (Wang et al., 2016). Similarly, a nearly 3 : 1 flow cytometry ratio was observed in 6x and 2x Handroanthus species (D. S. Sampaio, Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Brazil, unpubl. res.). Given the absence of large-scale genome downsizing, and the ubiquity of correlations between ploidy, genome size and cell size, our data suggest that divergences of these traits largely occurred during WGD.

Genome size changes by polyploidy might affect cell size via epigenetic, biophysical effects of increased bulk DNA amount (e.g. ‘nucleotypic theory’, reviewed by Doyle and Coate, 2019) or via altered gene expression patterns due to massive gene duplication, but our study was not designed to distinguish between these. Although ploidy–cell size correlations are ubiquitous, the direction and chain of causality is not at all clear (Tsukaya, 2013, 2019; Robinson et al., 2018). Polyploidy might cause larger cell sizes as a consequence of nucleotypic effects and/or higher net gene expression and protein synthesis and hence larger cytoplasmic volume accommodated by cell enlargement (Sugimoto-Shirasu and Roberts, 2003; Chevalier et al., 2014). However, it has also been argued that increases in cell size impose selection for larger genome size (Cavalier-Smith 1985), or higher gene dosage by WGD, which preserves stoichiometry while achieving the higher whole-cell biosynthetic rates needed to support large cells (Schmoller and Skotheim, 2015; Cantwell and Nurse, 2019).

How should ploidy and cell size be associated in a tip-growing cell? Pollen tube tips undergo self-similar growth, producing a tube of constant width (Fig. 1). Ploidy and cytoplasmic volume might be related through tube width, because the functional cytoplasm remains of constant size between the leading edge of the growing vacuole and the zone of wall production at the tube tip. The functional cytoplasm includes the active tube cell nucleus, male germ unit, organelles and other biosynthetic machinery which travel at fixed distances behind the elongating tip (Sanati-Nezhad et al., 2013; Geitmann and Nebenführ, 2015). With this unique cellular arrangement, enlargement of the cytoplasm without changing tube width would elongate the active cytoplasm zone, increasing intracellular trafficking distances between vacuole, nucleus and zones of new wall production. Increasing tube width would keep the functional cytoplasm compact and near the tip, but at the cost of having to produce more wall material. One might expect diploid tubes to accommodate double the volume of cytoplasm as haploids (as seen in many other cell types), but we found that polyploid tubes were only 13–25 % wider, which is less than the 41 % needed for a two-fold volume increase by width alone. Variation in the dimensional effect of ploidy probably reflects the degree to which the trade-off between cytoplasm length and width is resolved relative to maintaining a functional PTGR in each species.

Linking the contribution of dimensional and energetic changes to cell growth rates

As discussed above, the evidence suggests that the relationships between tube size, genome size and ploidy level have been stable since WGD in both genera. Thus, we consider the present-day differences in tube cell sizes to primarily correlate with ploidy increase, irrespective of the mechanisms or direction of causality (Robinson et al., 2018). Energetic differences may also have evolved in concert with changes in ploidy and cell size (Schoenfelder and Fox, 2015; Coate and Doyle, 2010; Chevalier et al., 2014), but energetics are likely to also evolve independently, because vastly different PTGRs have evolved in pollen tubes of similar size (Williams et al., 2016).

Larger tube size should cause slower PTGR in the absence of correlated changes in biosynthetic rates. The magnitude of the tube-size penalty on polyploid PTGR can be estimated by assuming polyploid pollen tubes retain the biosynthetic rates of their diploid relatives. The difference between the actual polyploid PTGR and the PTGR predicted by dimensional effects alone is an estimate of the magnitude of energetic effects on PTGR.

Our measures of biosynthetic rates, WPR and VGR, are a function of net rates of endocytosis, exocytosis, intracellular trafficking, and cell wall synthesis, assembly and modification (Cai et al., 2015; Geitmann and Nebenführ, 2015). To maintain turgor pressure by vacuole filling, VGR must track PTGR, but WPR ultimately determines the rate of tip-elongation, PTGR (Winship et al., 2011). And because

Assuming PTGR evolves only by a change in the volume of wall materials per unit of growth, WA, the predicted PTGR of larger polyploid pollen tubes (with 2x or 3x genome sizes) is a function of 1x WPR of its diploid relative and its 2x or 3x wall volume, WA. For the hexaploids:

The magnitude of the tube-size penalty on 3x PTGR is estimated as the predicted 3x PTGR minus actual 1x PTGR, whereas the size of the energetic effect on 3x PTGR is the actual 3x PTGR minus the predicted 3x PTGR (Table 5). Dimensional effects are always negative when polyploid pollen tubes are larger, whereas energetic effects can be positive or negative, depending on the evolved PTGR of the neo-polyploid. Polyploid tubes must grow slower or faster than those of their haploid relatives (or ancestor/s) only to the extent that energetic effects overcome or amplify the dimensional effect.

Table 5.

Magnitude of predicted dimensional and energetic effects on PTGRs of polyploid species

| Betula | Actual 1x | Actual 3x | Difference 3x – 1x | Predicted 3x | Dimensional effect (%) | Energetic effect (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W A (μm2) | 3.63 | 4.10 | +0.47 | |||

| WPR (μm3 h−1) | 34.46 | 38.69 | +4.23 | |||

| PTGR (μm h−1) | 9.95 | 8.95 | −1.00 | 8.405 | −1.545 (−15.5 %) | +0.545 (+5.5 %) |

| Handroanthus | Actual 1x | Actual 2x | Difference 2x – 1x | Predicted 2x | Dimensional effect | Energetic effect |

| W A (μm2) | 5.248 | 5.680 | +0.432 | |||

| WPR (μm3 h−1) | 9.011 | 6.273 | −2.738 | |||

| PTGR (μm h−1) | 1.717 | 1.104 | −0.613 | 1.586 | −0.131 (−7.6 %) | −0.482 (−28.1 %) |

| Handroanthus | Actual 1x | Actual 3x | Difference 3x – 1x | Predicted 3x | Dimensional effect | Energetic effect |

| W A (μm2) | 5.248 | 6.545 | +1.297 | |||

| WPR (μm3 h−1) | 9.011 | 10.585 | +1.574 | |||

| PTGR (μm h−1) | 1.717 | 1.617 | −0.100 | 1.378 | −0.339 (−19.7 %) | +0.239 (+13.9 %) |

The proximal effects occur via changes in wall area, WA, and wall production rate, WPR, respectively. The effects of each on PTGR are based on the differences between actual and predicted PTGRs of species with 1x, 2x or 3x pollen tubes. Effect size is percentage of 1x PTGR. Handroanthus values are ×103.

In Betula and Handroanthus, the tube-size penalty predicts a 15.5–19.7 % PTGR slowdown in hexaploids (3x pollen) over diploids (1x pollen), respectively (Table 5). However, because actual polyploid PTGRs were not much slower than in the diploid species, positive energetic effects have counterbalanced negative dimensional effects (as also suggested by the higher WPRs of the polyploids). Energetic effects on PTGR were smaller than dimensional effects (Table 5), with the caveat that our estimates of PTGRs were not precise enough to detect significant differences (but neither can we accept them as equal).

In summary, polyploid pollen tubes were larger in width and produced more wall material per unit of growth. If wall synthesis rates were unaffected by polyploidy, dimensional effects would reduce PTGR proportionally. Instead we found that hexaploids had faster wall production rates than diploids and also faster volumetric growth rates, requiring more work to import and transfer solutes to their wider vacuoles. Thus, we conclude that hexaploids in this study have evolved higher per cell metabolic rates than their diploid relatives.

Polyploidy and the developmental evolution of PTGR

Polyploidy has long been associated with reduced developmental rates at the organismal or organ/tissue level, attributed to the effects of prolonged cell cycles and increased mature cell sizes (Bennett, 1971, 1972; Levin, 1983; Doyle and Coate, 2019). Although studies rarely measure the speed of individual cell growth, polyploidy is often associated with positive metabolic effects (Ohno, 1970; Birchler and Veitia, 2010; Pires and Conant, 2016). The prevalence of endopolypoidy in highly metabolically active cell types highlights the importance of gene dosage on physiological rates (D’Amato, 1984; Frawley and Orr-Weaver, 2015; but see Tsukaya 2019), whereas the effects of sheltering of deleterious recessives and/or heterosis on growth are well known in polyploids (Birchler et al., 2010), and are more likely to appear after a shift from haploid to polyploid gene expression.

Tip-growing cells are ideal models for understanding the balance between such effects on cell growth, because growth is restricted to a terminal stage of the cell cycle and because cell growth rate is tightly coupled to cell energetics (Bove et al., 2008; Rounds et al., 2011). In pollen tubes, tip-growth rate is a primary target of natural and sexual selection, because pollen tubes must transfer sperm to ovules before egg senescence and before any competing pollen tubes. Pollen tubes are known to have roughly ten-fold higher respiration rates than somatic cells (Tadege and Kuhlemeier 1997). The high metabolic rates in these haploid cells suggests that genes for biosynthetic rates are more likely to be DNA template-limited and therefore to respond to increases in gene dosage by WGD.

Our results indicate that polyploidy provides metabolic benefits to PTGR that are masked by cell-size effects, an important point, given that PTGR itself is often taken as an indicator of ‘metabolic vigor’ (Snow and Spira, 1991; Walsh and Charlesworth, 1992; Skogsmyr and Lankinen, 2002; Mazer et al., 2010; Baskin and Baskin, 2015; Williams et al., 2016). A large comparative study recently found that angiosperm neo-polyploids evolved around a faster PTGR optimum than diploids, and angiosperms had a more positive relationship between genome size and PTGR than gymnosperms (Reese and Williams, 2019). If the tube-size penalty of polyploidy is general, then substantial metabolic evolution must underlie the evolution of fast PTGRs in angiosperm neo-polyploids. Still, the relative contributions of ploidy change itself vs. subsequent evolutionary processes to changes in PTGR traits is unknown. That neo-autopolyploids typically do not have faster PTGRs than their progenitors suggests that metabolic rates also evolve after WGD, depending on the degree of genetic variation, gene sorting and gene sequence evolution.

Plant genome size–metabolic trait correlations in comparative studies typically have low explanatory power (see Beaulieu et al. 2007), and cell size and mode of genome size change are large sources of variation (Panchy et al., 2016). When genome size increases by WGD, the magnitude of potential energetic change depends on genetic diversity (Reese and Williams, 2019). Allopolyploids and highly outcrossing or hybridizing autopolyploids and have high heterozygosity (Lande and Schemske, 1985; Soltis and Soltis, 2000; Parisod et al. 2010). Betula papyrifera has much higher heterozygosity than B. occidentalis (HO = 0.44 vs. 0.23) and much evidence of autopolyploid ancestry based on lack of fixed heterozygosity of allozymes (Williams, 2000). Both Betula and Handroanthus diploids and hexaploids have outcrossed breeding systems (Williams and Arnold, 2001; Bittencourt and Moraes, 2010; Alves et al., 2013; Mendes et al., 2018). Thus, higher gene dosage and higher heterozygosity may affect both the immediate and the subsequent evolution of metabolic rates.

Notably, the diploids in this study both have high chromosome numbers (2n = 28, 40) and are almost certainly ancient polyploids that have undergone genome downsizing and diploidization (Leitch and Bennett, 2004; Conant et al., 2014; Dodsworth et al., 2016). In Betula and other Fagalean taxa, PTGRs are among the slowest known in angiosperms, and all have many traits that suggest a history of weak or relaxed directional selection on PTGR (Williams and Reese, 2019). PTGRs in Handroanthus are more than two orders of magnitude faster, well above the angiosperm median (Williams et al., 2016), and these species have many features indicative of strong pollen competition (Williams and Reese, 2019). The positive effects of polyploidy on pollen tube energetics in these extremely different selective environments highlight the importance of maintaining PTGR for successful sexual reproduction.

Finally, polyploids that have evolved inbred mating systems or apomixis, such as the 4x H. chrysotrichus (Bittencourt and Moraes, 2010), have reduced opportunity for heterosis and gene sorting. Inbreeding, and especially apomixis, is expected to relax directional selection on PTGR due to reduced intensity of pollen competition and increased relatedness of competitors (Mazer et al., 2010; Williams and Reese, 2019). The finding of slower WPR and PTGR in the 4x apomict than in the sexual 2x and 6x species is consistent with the hypothesis that there has been relaxed directional selection on PTGR after the loss of outcrossing and/or sexual reproduction, such that both dimensional and energetic effects were negative (Table 5).

Difficulties of measuring tube cell dimensions, WPR and PTGR

In the ideal world, one would measure tube width, wall thickness and PTGR on exactly the same pollen tube to understand direct associations of dimensions and growth rate. This is not easily done, because pollen tube length is on the order of millimetres or centimetres, whereas tube wall thicknesses are on the order of nanometres and need to be visualized in cross-section from specially prepared material. Our estimates of wall thickness were labour-intensive because under the light microscope, wall thicknesses were near the limits of resolution. Yet, transmission electron micrographs from other studies show pollen tube wall thicknesses near ours, in the range of 150–230 nm (reviewed by Williams et al., 2016). Note that in vivo pollen tube cell walls are highly hydrated, and fixation and preparation for microscopy entails substantial shrinkage (Vogler et al., 2013). Thus, it is important to make comparisons of material that has been treated the same way.

We have now found that differences in wall thickness are small relative to differences in tube circumference in two groups of close relatives (this study) and one group of distant relatives (Williams et al., 2016). If one assumes that wall thickness differences are small, then relative WPRs could be measured as: WPR = k × C × PTGR, where k is a wall thickness constant, but could range conservatively from 0.12 to 0.30 µm. That would allow one to use longitudinal whole-mount material to measure both diameter and length on the same pollen tube (Fig. 3D).

However, tube width is not always straightforward to measure. Tubes deform easily in solid transmitting tracts as they grow around pollen tube pathway cells, as in Betula and the upper style of Handroanthus, whereas in more open, secretory canals, such as in Handroanthus (Fig. 3C, D), distal areas of the tube can collapse. We found that circumferences of deformed and turgid tubes growing perpendicular to the plane of measurement were similar to circumferences of callose plugs, which preserve the cylindrical shape of the turgid tube. Thus, in longitudinal section, one could estimate C by measuring the diameters of callose plugs and multiplying by π. When tubes are visualized in whole mounts within cleared tissues after softening and crushing styles before staining (Kearns and Inouye, 1993), callose plugs can appear slightly larger due to their brightness or to being out of focus. However, even in very small styles, it is easy to slit the style in half, as done in Handroanthus, which allows much clearer visualization of pollen tube structure and callose plugs (Fig. 3D). Callose plugs can constrict or bulge, so one might measure tube width just above or below a callose plug. If one were able to estimate WPRs of individual pollen tubes in this way, a much greater sample size would be possible.

CONCLUSION

Despite the difficulties in measuring pollen tubes using light microscopy, our approach allowed us to decouple cell-level dimensional and energetic effects of polyploidy on pollen tube growth, with consequences for reproduction and evolution of angiosperms as a whole. Polyploidy imposed a substantial materials cost in the form of larger tube circumference, but also generated compensating energetic effects, as indicated by faster wall production rates, resulting in evolutionary stasis of PTGR. It is likely that dimensional effects on PTGR in both genera have persisted since diploid–polyploid divergence, because large tube size and slow PTGR are consistently seen in artificial autopolyploids (Reese and Williams, 2019). Yet, reduced PTGR is not inevitable in natural, stabilized polyploid species (Reese and Williams, 2019; this study), an indication that diverse energetic effects have evolved during and after polyploid speciation events. That selection plays a role in generating or maintaining faster net metabolic rates in polyploids is suggested by the much lower wall production rates in the self-compatible, apomictic tetraploid – an indicator of relaxed selection on PTGR. Given the pervasive cycles of WGDs in angiosperms relative to gymnosperms (Leitch and Leitch, 2012), if dimensional effects of polyploidy generally act as a brake on PTGR, our results suggest that selection on biosynthetic rates during the male gametophytic phase of angiosperm polyploids has probably contributed to their orders-of-magnitude faster PTGRs over those of gymnosperms.

FUNDING

This work was supported by National Science Foundation grant IOS 1052291 to J.H.W. and a Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior sabbatical grant (BEX 5838/14-2) to P.E.O. to work at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank M. Rankin for her careful microscopy work on Betula, J. Edwards for help in the lab and D. Sampaio for sharing unpublished estimates of DNA C-values for Handroanthus. We also thank J. Reese and especially one anonymous reviewer for comments, and G. T. di Lampedusa for help with the title.

LITERATURE CITED

- Albersheim P, Darvill A, Roberts K, Sederoff R, Staehelin A. 2011. Plant cell walls: from chemistry to biology. New York: Garland Science. [Google Scholar]

- Alves MF, Duarte MO, Oliveira PE, Sampaio DS. 2013. Self-sterility in the hexaploid Handroanthus serratifolius (Bignoniaceae), the national flower of Brazil. Acta Botanica Brasilica 27: 714–722. [Google Scholar]

- Arunkumar R, Josephs EB, Williamson RJ, Wright SI. 2013. Pollen-specific, but not sperm-specific, genes show stronger purifying selection and higher rates of positive selection than sporophytic genes in Capsella grandiflora. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 2475–2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin JM, Baskin CC. 2015. Pollen (microgametophyte) competition: an assessment of its significance in the evolution of flowering plant diversity, with particular reference to seed germination. Seed Science Research 25: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM, Leitch IJ, Knight CA. 2007. Genome size evolution in relation to leaf strategy and metabolic rates revisited. Annals of Botany 99: 495–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM, Leitch IJ, Patel S, Pendharkar A, Knight CA. 2008. Genome size is a strong predictor of cell size and stomatal density in angiosperms. New Phytologist 179: 975–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benkert R, Obermeyer G, Bentrup FW. 1997. The turgor pressure of growing lily pollen tubes. Protoplasma 198: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MD. 1971. Duration of meiosis. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 178: 277–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MD. 1972. Nuclear DNA content and minimum generation time in herbaceous plants. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 181: 109–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchler JA, Veitia RA. 2010. The gene balance hypothesis: implications for gene regulation, quantitative traits and evolution. New Phytologist 186: 54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchler JA, Yao H, Chudalayandi S, Vaiman D, Veitia RA. 2010. Heterosis. Plant Cell 22: 2105–2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittencourt NS, Moraes CIG. 2010. Self-fertility and polyembryony in South American yellow trumpet trees (Handroanthus chrysotrichus and H. ochraceus, Bignoniaceae): a histological study of postpollination events. Plant Systematics and Evolution 288: 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Blakeslee AF. 1941. Effect of induced polyploidy in plants. American Naturalist 75: 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Bove J, Vaillancourt B, Kroeger J, Hepler PK, Wiseman PW, Geitmann A. 2008. Magnitude and direction of vesicle dynamics in growing pollen tubes using spatiotemporal image correlation spectroscopy and fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. Plant Physiology 147: 1646–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai G, Parrotta L, Cresti M. 2015. Organelle trafficking, the cytoskeleton, and pollen tube growth. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 57: 63–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell H, Nurse P. 2019. Unravelling nuclear size control. Current Genetics 65: 1281–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smith T. 1985. Cell volume and the evolution of eukaryote genome size. In: Cavalier-Smith T, ed. The evolution of genome size. New York: Wiley and Sons, 105–184. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smith T. 2005. Economy, speed and size matter: evolutionary forces driving nuclear genome miniaturization and expansion. Annals of Botany 95: 147–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chebli Y, Kaneda M, Zerzour R, Geitmann A. 2012. The cell wall of the Arabidopsis pollen tube – Spatial distribution, recycling, and network formation of polysaccharides. Plant Physiology 160: 1940–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Gong P, Guo J et al. 2018. Glycolysis regulates pollen tube polarity via Rho GTPase signaling. PLoS Genetics 14: e1007373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier C, Bourdon M, Pirrello J, Cheniclet C, Gévaudant F, Frangne N. 2014. Endoreduplication and fruit growth in tomato: evidence in favour of the karyoplasmic ratio theory. Journal of Experimental Botany 65: 2731–2746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coate JE, Doyle JJ. 2010. Quantifying whole transcriptome size, a prerequisite for understanding transcriptome evolution across species: an example from a plant allopolyploid. Genome Biology and Evolution 2: 534–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colaço R, Moreno N, Feijó JA. 2012. On the fast lane: mitochondria structure, dynamics and function in growing pollen tubes. Journal of Microscopy 247: 106–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conant GC, Birchler JA, Pires JC. 2014. Dosage, duplication, and diploidization: clarifying the interplay of multiple models for duplicate gene evolution over time. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 19: 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. 2018. Diffuse growth of plant cell walls. Plant Physiology 176: 16–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl AE, Fredrikson M. 1996. The timetable for development of maternal tissues sets the stage for male genomic selection in Betula pendula (Betulaceae). American Journal of Botany 83: 895–902. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato F. 1984. Role of polyploidy in reproductive organs and tissues. In: Johri BM, ed. Embryology of angiosperms. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 519–566. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ario M, Sablowski R. 2019. Cell size control in plants. Annual Review of Genetics 53: 45–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodsworth S, Chase MW, Leitch AR. 2016. Is post-polyploidization diploidization the key to the evolutionary success of angiosperms? Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 180: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ, Coate JE. 2019. Polyploidy, the nucleotype, and novelty: the impact of genome doubling on the biology of the cell. International Journal of Plant Sciences 180: 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fayant P, Girlanda O, Chebli Y, Aubin CE, Villemure I, Geitmann A. 2010. Finite element model of polar growth in pollen tubes. Plant Cell 22: 2579–2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frawley LE, Orr-Weaver TL. 2015. Polyploidy. Current Biology 25: R353–R358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S-M, Yang M-H, Zhang F, Fan L-J, Zhou Y. 2019. The strong competitive role of 2n pollen in several polyploidy hybridizations in Rosa hybrida. BMC Plant Biology 19: 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geitmann A. 2011. Generating a cellular protuberance: mechanics of tip growth. In: Wojtaszek P, ed. Mechanical integration of plant cells and plants. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Geitmann A, Nebenführ A. 2015. Navigating the plant cell: intracellular transport logistics in the green kingdom. Molecular Biology of the Cell 26: 3373–3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory TR. 2001. The bigger the C-value, the larger the cell: genome size and red blood cell size in vertebrates. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases 27: 830–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grose SO, Olmstead R. 2007. Taxonomic revisions in the polyphyletic genus Tabebuia s. l. (Bignoniaceae). Systematic Botany 32: 660–670. [Google Scholar]

- Hafidh S, Fíla J, Honys D. 2016. Male gametophyte development and function in angiosperms: a general concept. Plant Reproduction 29: 31–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler PK, Winship LJ. 2015. The pollen tube clear zone: clues to the mechanism of polarized growth. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 57: 79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C, Munglani G, Vogler H et al.. 2017. Characterization of size-dependent mechanical properties of tip-growing cells using a lab-on-chip device. Lab Chip 17: 82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immler S. 2019. Haploid selection in “diploid” organisms. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 50: 219–236. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar NK. 1938. Pollen-tube studies in Gossypium. Journal of Genetics 37: 69–106. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao YN, Wickett NJ, Ayyampalayam S et al.. 2011. Ancestral polyploidy in seed plants and angiosperms. Nature 473: 97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns CA, Inouye DW. 1993. Techniques for pollination biologists. Niwot: University Press of Colorado. [Google Scholar]

- Kostoff D, Prokofieva AA. 1935. Studies on pollen tubes 1. Trudy Instituta Genetiki 10: 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lancelle SA, Hepler PK. 1992. Ultrastructure of freeze-substituted pollen tubes of Lilium longiflorum. Protoplasma 167: 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Lande R, Schemske DW. 1985. The evolution of self‐fertilization and inbreeding depression in plants. I. Genetic models. Evolution 39: 24–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JB, Soltis DE, Li Z. 2018. Impact of whole‐genome duplication events on diversification rates in angiosperms. American Journal of Botany 105: 348–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch I, Bennett M. 2004. Genome downsizing in polyploid plants. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 82: 651–663. [Google Scholar]

- Leitch A, Leitch I. 2012. Ecological and genetic factors linked to contrasting genome dynamics in seed plants. New Phytologist 194: 629–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin DA. 1983. Polyploidy and novelty in flowering plants. American Naturalist 122: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mayrose I, Zhan SH, Rothfels CJ et al.. 2011. Recently formed polyploid plants diversify at lower rates. Science 333: 1257–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazer SJ, Hove AA, Miller BS, Barbet-Massin M. 2010. The joint evolution of mating system and pollen performance: predictions regarding male gametophytic evolution in selfers vs. outcrossers. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 12: 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes MG, de Oliveira AP, Oliveira PE, Bonetti AM, Sampaio DS. 2018. Sexual, apomictic and mixed populations in Handroanthus ochraceus (Bignoniaceae) polyploid complex. Plant Systematics and Evolution 304: 817–829. [Google Scholar]

- Modlibowska I. 1945. Pollen tube growth and embryo-sac development in apples and pears. PhD Thesis, University of London, London. [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahy DL. 1979. The rise of the angiosperms – a genecological factor. Science 206: 20–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermeyer G, Fragner L, Lang V, Weckwerth W. 2013. Dynamic adaption of metabolic pathways during germination and growth of lily pollen tubes after inhibition of the electron transport chain. Plant Physiology 162: 1822–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S. 1970. Evolution by gene duplication. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien TP, McCully ME. 1981. The study of plant structure: principles and selected methods. Melbourne: Termarcarphi Pty. Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Palser BF, Rouse JL, Williams EG. 1989. Coordinated timetables for megagametophyte development and pollen tube growth in Rhododendron nuttallii from anthesis to early postfertilization. American Journal of Botany 76: 1167–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Panchy N, Lehti-Shiu M, Shiu S-H. 2016. Evolution of gene duplication in plants. Plant Physiology 171: 2294–2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisod C, Holderegger R, Brochmann C. 2010. Evolutionary consequences of autopolyploidy. New Phytologist 186: 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parre E, Geitmann A. 2005. More than a leak sealant. The mechanical properties of callose in pollen tubes. Plant Physiology 137: 274–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires JC, Conant GC. 2016. Robust yet fragile: expression noise, protein misfolding, and gene dosage in the evolution of genomes. Annual Review of Genetics 50: 113–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price H, Sparrow A, Nauman AF. 1973. Correlations between nuclear volume, cell volume and DNA content in meristematic cells of herbaceous angiosperms. Experientia 29: 1028–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Rabillé H, Billoud B, Tesson B, Le Panse S, Rolland É, Charrier B. 2019. The brown algal mode of tip growth: Keeping stress under control. PLoS Biology 17: e2005258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese JB, Williams JH. 2019. How does genome size affect the evolution of pollen tube growth rate, a haploid performance trait? American Journal of Botany 106: 1011–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren R, Wang H, Guo C et al.. 2018. Widespread whole genome duplications contribute to genome complexity and species diversity in angiosperms. Molecular Plant 11: 414–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DO, Coate JE, Singh A et al.. 2018. Ploidy and size at multiple scales in the Arabidopsis sepal. Plant Cell 30: 2308–2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounds CM, Winship LJ, Hepler PK. 2011. Pollen tube energetics: respiration, fermentation and the race to the ovule. AoB Plants 2011: plr019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanati Nezhad A, Geitmann A. 2013. The cellular mechanics of an invasive lifestyle. Journal of Experimental Botany 64: 4709–4728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanzol J, Herrero M. 2001. The “effective pollination period” in fruit trees. Scientia Horticulturae 90: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Schmoller KM, Skotheim JM. 2015. The biosynthetic basis of cell size control. Trends in Cell Biology 25: 793–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfelder KP, Fox DT. 2015. The expanding implications of polyploidy. Journal of Cell Biology 209: 485–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selinski J, Scheibe R. 2014. Pollen tube growth: where does the energy come from? Plant Signaling & Behavior 9: e977200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuter BJ, Thomas J, Taylor WD, Zimmerman AM. 1983. Phenotypic correlates of genomic DNA content in unicellular eukaryotes and other cells. American Naturalist 122: 26–44. [Google Scholar]

- Šímová I, Herben T. 2012. Geometrical constraints in the scaling relationships between genome size, cell size and cell cycle length in herbaceous plants. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 279: 867–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skogsmyr I, Lankinen A. 2002. Sexual selection: an evolutionary force in plants. Biological Reviews 77: 537–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow AA, Spira TP. 1991. Pollen vigour and the potential for sexual selection in plants. Nature 352: 796–797. [Google Scholar]

- Soltis PS, Soltis DE. 2000. The role of genetic and genomic attributes in the success of polyploids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 97: 7051–7057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone B, Evans NA, Bonig I, Clarke AE. 1984. The application of Sirofluor, a chemically defined fluorochrome from aniline blue for the histochemical detection of callose. Protoplasma 122: 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto-Shirasu K, Roberts K. 2003. “Big it up”: endoreduplication and cell-size control in plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 6: 544–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadege M, Kuhlemeier C. 1997. Aerobic fermentation during tobacco pollen development. Plant Molecular Biology 35: 343–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukaya H. 2013. Does ploidy level directly control cell size? Counterevidence from Arabidopsis genetics. PLoS One 8: e83729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukaya H. 2019. Has the impact of endoreduplication on cell size been overestimated? New Phytologist 223: 11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogler H, Draeger C, Weber A. 2013. The pollen tube: a soft shell with a hard core. Plant Journal 73: 617–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh NE, Charlesworth D. 1992. Evolutionary interpretations of differences in pollen tube growth rates. Quarterly Review of Biology 67: 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, McAllister HA, Bartlett PR, Buggs RJ. 2016. Molecular phylogeny and genome size evolution of the genus Betula (Betulaceae). Annals of Botany, 117: 1023–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JH., Jr. 2000. Evolution of a broad diploid–polyploid birch (Betula) hybrid zone. PhD Thesis, University of Georgia, Athens, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JH. 2008. Novelties of the flowering plant pollen tube underlie diversification of a key life history stage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 105: 11259–11263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JH, Arnold ML. 2001. Sources of genetic structure in the woody perennial Betula occidentalis. International Journal of Plant Sciences 162: 1097–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JH, Edwards JA, Ramsey AJ. 2016. Economy, efficiency, and the evolution of pollen tube growth rates. American Journal of Botany 103: 471–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JH Jr, Friedman WE, Arnold ML. 1999. Developmental selection within the angiosperm style: using gamete DNA to visualize interspecific pollen competition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 96: 9201–9206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JH, Reese JB. 2019. Evolution of development of pollen performance. Current Topics in Developmental Biology 131: 299–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winship LJ, Obermeyer G, Geitmann A, Hepler PK. 2010. Under pressure, cell walls set the pace. Trends in Plant Science 15: 363–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winship LJ, Obermeyer G, Geitmann A, Hepler PK. 2011. Pollen tubes and the physical world. Trends in Plant Science 16: 353–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood TE, Takebayashi N, Barker MS, Mayrose I, Greenspoon PB, Rieseberg LH. 2009. The frequency of polyploid speciation in vascular plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 106: 13875–13879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]