Abstract

Background

The morphological and molecular identification of mites is challenging due to the large number of species, the microscopic size of the organisms, diverse phenotypes of the same species, similar morphology of different species and a shortage of molecular data.

Methods

Nine medically important mite species belonging to six families, i.e. Demodex folliculorum, D. brevis, D. canis, D. caprae, Sarcoptes scabiei canis, Psoroptes cuniculi, Dermatophagoides farinae, Cheyletus malaccensis and Ornithonyssus bacoti, were collected and subjected to DNA barcoding. Sequences of cox1, 16S and 12S mtDNA, as well as ITS, 18S and 28S rDNA from mites were retrieved from GenBank and used as candidate genes. Sequence alignment and analysis identified 28S rDNA as the suitable target gene. Subsequently, universal primers of divergent domains were designed for molecular identification of 125 mite samples. Finally, the universality of the divergent domains with high identification efficiency was evaluated in Acari to screen DNA barcodes for mites.

Results

Domains D5 (67.65%), D6 (62.71%) and D8 (77.59%) of the 28S rRNA gene had a significantly higher sequencing success rate, compared to domains D2 (19.20%), D3 (20.00%) and D7 (15.12%). The successful divergent domains all matched the closely-related species in GenBank with an identity of 74–100% and a coverage rate of 92–100%. Phylogenetic analysis also supported this result. Moreover, the three divergent domains had their own advantages. D5 had the lowest intraspecies divergence (0–1.26%), D6 had the maximum barcoding gap (10.54%) and the shortest sequence length (192–241 bp), and D8 had the longest indels (241 bp). Further universality analysis showed that the primers of the three divergent domains were suitable for identification across 225 species of 40 families in Acari.

Conclusions

This study confirmed that domains D5, D6 and D8 of 28S rDNA are universal DNA barcodes for molecular classification and identification of mites. 28S rDNA, as a powerful supplement for cox1 mtDNA 5’-end 648-bp fragment, recommended by the International Barcode of Life (IBOL), will provide great potential in molecular identification of mites in future studies because of its universality.

Keywords: Mites, rDNA 28S, Universal primers, Divergent regions, Molecular identification, DNA barcode

Background

Mites are a large group of microscopic arthropods, which exist widely in the natural environment, and are classified as Arachnida, Acari, Acariformes and Parasitiformes. For a long time, the classification of mites has mainly been dependent on morphological characteristics and/or parasitic hosts. However, this field has been facing challenges due to the large number of species, the microscopic size of the organisms, diverse phenotypes of the same species, similar morphology of different species, and a shortage of specialized taxonomists [1–3]. Medically important mites can serve as pathogens, allergens, or microorganism reservoirs and are significant for human and animal health. Sarcoptes, Demodex or Psoroptes mites as pathogens can directly infect humans or mammals and cause skin or external auditory canal lesions [4–7]. Dermatophagoides farinae, D. pteronyssinus and Euroglyphus maynei as allergen mites can cause allergic diseases [8]. Some species of gamasid mites and chigger mites, as vectors or reservoirs, can result in the spread of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, scrub typhus and other acute infectious diseases [9, 10]. Therefore, in order to take targeted measures to control mite-borne diseases, it is extremely important to distinguish medically important mites effectively.

Although rapidly developed molecular biology techniques have provided support for classification and identification of mites [11–14], there are still some problems with the classification technique of DNA barcoding: (i) a shortage of molecular data. More than 50,000 mite species have been identified in nature [15], whereas less than 100 species have molecular data available on GenBank. Therefore, for most species the gene sequence template for designing primers is not available, and thus they cannot be identified by molecular techniques; (ii) the limited research reports. Only a small number of mite species have been identified by DNA barcoding, mainly based on cox1 [16–26], 16S and 12S mtDNA gene fragments [2, 27–32], especially cox1 648-bp fragment. However, these studies usually involve one family, one genus, and a few species. In addition, there is a lack of clarity regarding the universality and identification efficiency of the primers as they are located at different positions of the same gene sequences in different species; and (iii) fewer reports on rDNA barcodes compared to mtDNA. The limited reports on rDNA are mainly concentrated on the ITS region [15, 19, 21], for which primers are not universal as they are located in different positions of sequences which are lacking in some mite species. It is unusual for 18S and 28S rRNA genes to be used for molecular identification at lower taxonomic ranks (species and genus) [14, 18, 33–35], which may result from the traditional opinion that both are conserved and thus suitable for identification at the higher taxonomic ranks. However, their true value in species identification at lower taxonomic ranks might be underestimated.

In the present study, 125 mite samples of nine medically important mite species belonging to six families were collected and identified based on morphology. Subsequently, sequences of the cox1, 16S and 12S mtDNA regions, and the ITS, 18S and 28S rDNA regions, were downloaded from GenBank for sequence alignment, and previously reported primers used for molecular identification of the nine mite species were marked. Based on the universality analysis of these primers, 28S rDNA, which is composed of alternated conserved regions and divergent regions with large sequence differences, was screened and confirmed as the target gene. Universal or degenerate primers of D2, D3, D5, D6, D7 and D8 regions were designed specifically for molecular identification of the nine mite species. By comparing the sequencing success rate, intraspecific divergence, and DNA barcoding gap of the six divergent regions, D5, D6 and D8 regions, were confirmed as DNA barcodes for the nine mite species. Finally, all partial 28S rRNA gene sequences of species of the Acariformes and Parasitiformes were retrieved from GenBank and aligned to verify the universality of the primers of the DNA barcodes. In summary, this study aimed to provide a novel approach for molecular classification of mites, and thereby to solve the difficulty in morphological and molecular identification through screening universal regions to be used in DNA barcoding of medically important mites.

Methods

Collection and morphological classification of mites

Medically important mites collected in this study were classified morphologically by two approaches. First, some mites were directly classified according to their parasitic habitats and hosts, including Ornithonyssus bacoti from rat-lingering areas [10], Psoroptes cuniculi isolated from the external auditory canal of rabbits [36], Sarcoptes scabiei canis [26], Demodex canis [37] collected from dogs suffering from mange and demodicosis, and D. caprae isolated from skin nodules of goats [38]. Next, mites of different species residing in the same habitat or host were further identified according to morphological characteristics such as size, shape, color, dermatoglyph, and chelicerae. These included D. farinae [39] and Cheyletus malaccensis [40] breeding in a flour-processing workshop, and D. folliculorum and D. brevis collected from humans [1]. A total of 125 mite samples were collected. Images were taken using a light microscope (MOTIC, Xiamen, China).

Target gene screening and universal primer design

The gene sequences of cox1, 16S and 12S mtDNA, and ITS, 18S and 28S rDNA for species of the six mite families involved in our study were downloaded from GenBank for alignment. The universality of the commonly used primers reported previously was analyzed based on the alignment results. Multiple pairs of universal or degenerate primers were designed in the conserved regions of the 28S rDNA.

Molecular identification of medically important mites

Genomic DNA was extracted from individual mites using the Chelex-100 method and used directly for PCR amplification and cloning as previously described in Cheng et al. [36]. Positive clones were sent to Genewiz Biological Co., Ltd (Suzhou, China) for sequencing. For each 28S rRNA gene fragment, five sequences were obtained for most mites, fewer than 5 sequences were obtained for only a few mites. Each sequence was assigned to a species according to its coverage rate and identity with the corresponding sequence in the GenBank database by BLAST analysis. Based on the sequencing success rate, candidate DNA barcodes were preliminarily screened.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed using maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods. The mite sequences of candidate DNA barcodes obtained in this study and the closely related species deposited in GenBank were aligned using Clustal X 1.8 with the multiple alignment model. The ML trees were reconstructed using the Kimura 2-parameter (K2P) model in MEGA 5.0 [41], with each node supported by 1000 bootstraps. Before BI analysis, the most appropriate models were selected based on Akaikeʼs information criterion (AIC) in MrModeltest 2.3 and Modeltest 3.7 [42, 43]. In terms of fit and parsimony, the model with the lowest AIC value was identified as the best [44]. The GTR + I + G model was used for nucleotide sequences of 28S rDNA D5 and D6, the HKY + I + G model was used for D8. The BI trees were performed in MrBayes 3.2.1 [45]. The Markov chain was run with 2,000,000 generations, and trees were sampled every 100th generation. The first 25% of samples were discarded as ‘burn-in’, and the remaining data were used to generate a 50% majority-consensus tree. The phylogenetic trees were visualized using TreeGraph 2 [46].

Sequence divergence and DNA barcoding gap

Taking each family involved in this study as a unit, the intraspecific divergences and interspecific divergences of each 28S rRNA gene fragment were calculated using MEGA 5.0. Frequency distribution plots of divergences were drawn using SPSS 18.0. According to the screening criteria for ideal DNA barcodes [2], DNA barcodes were confirmed for the nine mite species.

Universality analysis

Using “Acari” and “28S rRNA” as keywords, the partial sequences over 3000 bp were downloaded from GenBank. One representative sequence of each species was chosen for alignment in Clustal X 1.8. Taking the almost complete 28S rDNA sequence of D. farinae (GenBank: JQ000555) as a template, the universal primers designed for the screened DNA barcodes were marked in order to analyze their universality in the Acariformes and Parasitiformes.

Results

Collection and morphological classification of mites

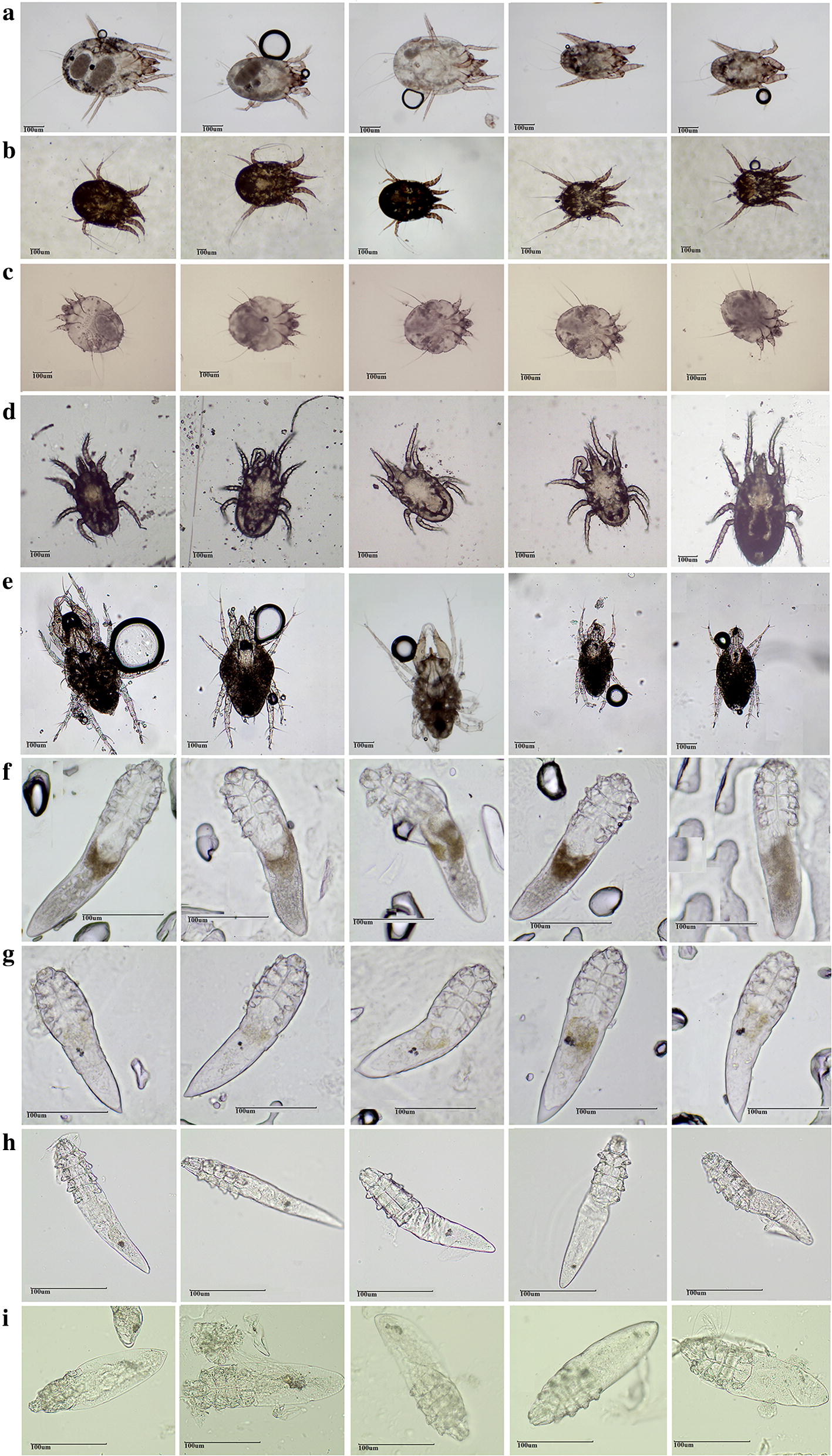

A total of nine medically important mite species were obtained in this study, including D. farinae (family Pyroglyphidae), P. cuniculi (family Psoroptidae), S. canis (family Sarcoptidae), O. bacoti (family Macronyssidae), C. malaccensis (family Cheyletidae), and D. folliculorum, D. brevis, D. canis and D. caprae (all of the family Demodicidae). Five mites were obtained for O. bacoti, 10 mites each for D. farinae, P. cuniculi, S. canis and C. malaccensis, and 20 mites each for the four Demodex species (D. folliculorum, D. brevis, D. canis and D. caprae). A total of 125 mites were photographed and identified based on morphology, and then used for genomic DNA extraction (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Adult morphology of the nine mite species. aDermatophagoides farinae (10 × 10); bPsoroptes cuniculi (10 × 4); cSarcoptes scabiei canis (10 × 10); dOrnithonyssus bacoti (10 × 10); eCheyletus malaccensis (10 × 10); fDemodex folliculorum (10 × 40); gDemodex brevis (10 × 40); hDemodex canis (10 × 40); iDemodex caprae (10 × 40). Scale-bars: 100 µm

Target gene screening and universal primer design

mtDNA gene fragments

Table 1 and Additional file 1: Figure S1 show the data for a total of 33 cox1 mtDNA gene sequences of the nine mite species retrieved from GenBank [2, 10, 36]. Taking the mtDNA complete sequence of D. farinae (GenBank: NC_013184) as a template, the sequence alignment showed that the forward primer of S. canis, and the forward and reverse primers of the C. malaccensis aligned well with the universal primers reported by Hebert et al. [47]. However, the other seven mite species had sequences of different lengths, and the primers were located at different positions where mutations or deletions occurred. Therefore, the cox1 mtDNA gene did not satisfy the requirements for designing universal primers.

Table 1.

Reported gene primers for medically important mites

| Mite | Gene | Length (bp) | Primers (5’-3’) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. farinae | cox1 | 832 (4–835) | F: GGACGATGATTAATATCCAC | Zhao et al. unpublished |

| R: CAATAGACACTATAGCATAAATCA | ||||

| 16S | 402 (65–466) | F: TCACACTAAGGTAGCGAG | ||

| R: ACGCCGACTTTAACTCA | ||||

| 12S | 837 (61–897) | F: CGGCTTTGGGAGTTGTAGAA | ||

| R: CTTATCTATCAAAAGAGTGACGGG | ||||

| ITS2 | 322 (116–437) | F: CGAACGCATATTGCAGCCATT | ||

| R: ATTCAGGGGGTAATCTCGCTTG | ||||

| P. cuniculi | cox1 | 652 (61–712) | F: GGTGTGTGAAGTGGTATATTG | Cheng et al. [36] |

| R: GCCCAAAAAACCAGAAA | ||||

| ITS2 | 275 (108–382) | F: GGCTTCGTTTGTCTGAG | ||

| R: GTAATCTCGCTTGATCTGA | ||||

| S. canis | cox1 | 819 (27–845) | F: GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGA | Zhao et al. [26] |

| R: CAATAGAAATCATAGCATAAA | ||||

| 16S | 320 (94–413) | F: TAGGGTCTTTTTGTCTTG | ||

| R: TATTATAAAAATATTAAATTAAAAAATTAG | ||||

| 12S | 743(61–803) | F: CATTAAGCAATTTCCCCA | ||

| R: CTAAACAAGAAACACTTTCCA | ||||

| ITS2 | 417 (94–510) | F: AGTATCCGATGGCTTCGTTTGTCT | ||

| R: AATCCCGTTTGGTTTCTTTTCCTC | ||||

| O. bacoti | cox1 | 479 (442–920) | F: CTTCATATYGCWGGTATTTCTT | Zhao et al. [10] |

| R: GTAGCTGTAGTAAAATARGCTCG | ||||

| 16S | 267 (97–363) | F: TGCTAAGAGAATGGAWDAA | ||

| R: CATCGRGGTCGCAAACT | ||||

| ITS | 510 (1–534) | F: GGTTTCCGTAGGTGAACC | ||

| R: CACTTGATTTCAGATACACGT | ||||

| C. malaccensis | cox1 | 709 (27–735) | F: GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTG | Zhao et al. unpublished |

| R: TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAA | ||||

| 12S | 388 (445–832) | F: CTAGGATTAGATACCCTATTA | ||

| R: ACTATGTTACGACTTATCTATC | ||||

| Demodex mites | cox1 | 750 (64–813) | F: CACATAGAACTTTCAATTCTAAA | Hu et al. [2] |

| R: CTCCTGCTGGGTCGAA | ||||

| 16S | 337 (52–388) | F: GAGGTATTTTGACTGTGCTA | ||

| R: TCAAAAGCCAACATCG | ||||

| 12S | 757 (79–835) | F: CTACTTTGTTACGACTTATTTTA | ||

| R: GCCAGCAGTTTCGGTTA |

Abbreviations: F, forward; R, reverse; Tm, melting temperature

A total of 25 16S mtDNA gene sequences were downloaded; no sequence was available for C. malaccensis. The sequence alignment showed that the primer positions of Demodex mites, D. farinae and O. bacoti were close, with the forward primers located at 570–610 bp and the reverse primers located at 900–1000 bp. However, the sequences were not conserved, and therefore, universal primers could not be designed.

A total of 22 12S mtDNA gene sequences were downloaded; no sequence was available for O. bacoti. For S. canis, D. farinae, and four Demodex mites, the forward primers were located at 190–230 bp, and the reverse primers were located at 790–840 bp. Nevertheless, the primer sequences differed greatly, so once again, universal primers could not be designed.

As the reported primers of cox1, 16S and 12S mtDNA genes were not universal for the nine mite species, these three genes could not be considered as the target genes for molecular identification in this study.

rRNA gene fragments

A total of 12 ITS rRNA gene sequences were obtained from GenBank; no sequences were available for species of the Cheyletidae and Demodicidae. As ITS2 sequences were too variable to be aligned, universal primers could not be designed (Additional file 2: Figure S2a). Therefore, the ITS rRNA was considered to be an unsuitable DNA barcode candidate.

A total of 18 complete 18S RNA gene sequences were obtained; no sequences were available for O. bacoti and S. canis. The sequence alignment showed that the 18S rRNA gene sequences were conserved and suitable for universal primer design; however, the sequence divergences were too small to identify the species efficiently. Thus, 18S rRNA was also not considered a suitable DNA barcode candidate gene (Additional file 2: Figure S2b).

Only 7 almost complete 28S rRNA gene sequences were obtained with sequences lacking for D. canis and D. caprae. Sequence alignment showed that 28S rDNA was significantly more variable than 18S rDNA, and obvious conserved regions were observed among D2, D3, D4, D5, D6, D7 and D8 regions (Additional file 3: Figure S3). Therefore, universal primers were successfully designed in the present study, with degenerate bases used for specific mutation sites (Table 2).

Table 2.

Universal or degenerate primers for divergent regions of 28S rDNA for the nine mite species

| Gene fragment | Length (bp) | Primers (5’-3’) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| D2 | 532 | F: AACAAGTACHGTGAKGGAA | 52 |

| R: CTCCTTGGTCCGTGTTTC | |||

| D3 | 252 | F: GTCTTGAAACACGGACCAA | 54 |

| R: ATCGATTTGCACGTCAGAA | |||

| D5 | 419 | F: TTCTGACGTGCAAATCGAT | 55 |

| R: GGCAGGTGAGTTGTTACACA | |||

| D6 | 202 | F: GTGTGTAACAACTCACCTGCC | 55 |

| R: TTGCTACTACCACCAAGATCTG | |||

| D7 | 465 | F: CAGATCTTGGTGGTAGTAGCA | 55 |

| R: CCTTGGAGACCTGCTGC | |||

| D8 | 314 | F: GCAKCAGGTCTCCAAGG | 52 |

| R: GTTTTAATTAGACAGTCGGATTC |

Abbreviations: F, forward; R, reverse; Tm, melting temperature

Note: The letters in bold in primers indicate degenerate bases

Molecular identification of nine mite species using divergent regions of 28S rDNA

PCR amplification, sequencing and alignment

The sequencing results and BLAST analysis of the nine mite species (Table 3) showed that the sequencing success rates for D2 (19.20%, 24/125), D3 (20.00%, 25/125) and D7 regions (15.12%, 13/86) were low due to the lower success rates for the four Demodex species (3.18%, 7/220). However, the sequencing success rates for D5 (67.65%, 46/68), D6 (62.71%, 37/59), and D8 (77.59%, 45/58) were significantly higher. Additionally, using the latter regions, the nine mite species were all matched with the corresponding species with sequences available on GenBank, with coverage rates of 92–100% and identities of 74–100%. Therefore, we concluded that D5, D6 and D8 regions could be considered as candidate DNA barcodes, while D2, D3 and D7 regions were excluded from further analysis.

Table 3.

Sequencing results of the six divergent regions of 28S rDNA for the nine mite species

| DD | Mite species | Length | SR% | GenBank ID | CRS | GenBank ID | I/C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D2 | D. farinae | 450–542 | 20.0 (2/10) | MH540331–32 | D. farinae | JQ000555 | 98/100 |

| P. cuniculi | 533 | 40.0 (4/10) | MH540338–41 | P. ovis | JQ000549 | 98/100 | |

| S. canis | 465–550 | 10.0 (1/10) | MH540342 | Mesalgoides sp. | JQ000537 | 77/100 | |

| O. bacoti | 465 | 100 (5/5) | MH540333–37 | O. bursa | FJ911789 | 92/100 | |

| C. malaccensis | 617 | 10.0 (1/10) | MH540329 | H. simplex | KP325024 | 99/100 | |

| D. folliculorum | / | 0 (0/20) | – | – | – | – | |

| D. brevis | / | 0 (0/20) | – | – | – | – | |

| D. canis | / | 0 (0/20) | – | – | – | – | |

| D. caprae | 773 | 5.0 (1/20) | MH540330 | H. holopus | KY922056 | 74/34 | |

| D3 | D. farinae | 252 | 50.0 (5/10) | MH001311–15 | D. farinae | JQ000555 | 99/100 |

| P. cuniculi | 252–256 | 40.0 (4/10) | MH001324–27 | P. ovis | JQ000549 | 99/100 | |

| S. canis | 256 | 0 (0/10) | – | – | – | ||

| O. bacoti | 256 | 100 (5/5) | MH001318–22 | C. haematophagus | FJ911790 | 99/100 | |

| C. malaccensis | 312–313 | 50.0 (5/10) | MH001306–10 | Oudemansicheyla sp. | KP276422 | 76/100 | |

| D. folliculorum | – | 0 (0/20) | – | – | – | – | |

| D. brevis | 358–362 | 20.0 (4/20) | MH540325–28 | D. folliculorum | KY922058 | 78/96 | |

| D. canis | 368 | 10.0 (2/20) | MH540323–24 | D. folliculorum | KY922058 | 86/95 | |

| D. caprae | – | 0 (0/20) | – | – | – | – | |

| D5 | D. farinae | 419 | 50.0 (5/10) | MH001255–59 | D. farinae | JQ000555 | 100/100 |

| P. cuniculi | 419 | 60.0 (6/10) | MH001275–80 | P. ovis | JQ000549 | 100/100 | |

| S. canis | 413–423 | 30.0 (3/10) | MH001267–69 | Cystoidosoma sp. | JQ000474 | 97/100 | |

| O. bacoti | 413 | 100 (5/5) | MH001260–64 | Melicharidae sp. | KP276394 | 99/100 | |

| C. malaccensis | 436 | 100 (5/5) | MH001270–74 | Oudemansicheyla sp. | KP276422 | 93/100 | |

| D. folliculorum | 456 | 83.3 (5/6) | KY305302–05, KY347877 | D. folliculorum | KY347877 | 99/100 | |

| D. brevis | 438–442 | 75.0 (6/8) | KY305306–11 | D. brevis | HQ718592 | 98/100 | |

| D. canis | 445–459 | 85.7 (6/7) | KY305312–17 | D. folliculorum | KY347877 | 93/100 | |

| D. caprae | 502–507 | 71.4 (5/7) | KY305318–22 | D. folliculorum | KY347877 | 83/100 | |

| D6 | D. farinae | 202 | 40.0 (2/5) | MH001286, MH001290 | D. farinae | JQ000555 | 99/100 |

| P. cuniculi | 192–200 | 40.0 (2/5) | MH001296, MH001300 | P. ovis | JQ000549 | 99/100 | |

| S. canis | 195–202 | 20.0 (1/5) | MH001301 | C. amazonae | KP325029 | 93/100 | |

| O. bacoti | 195 | 83.3 (5/6) | MH001291–95 | Melicharidae sp. | KP276394 | 98/100 | |

| C. malaccensis | 195–198 | 40.0 (4/10) | MH001281–84 | Oudemansicheyla sp. | KP276422 | 93/100 | |

| D. folliculorum | 241 | 100 (6/6) | KY305302–05, KY347876–77 | D. folliculorum | KY347876 | 99/100 | |

| D. brevis | 232 | 75.0 (6/8) | KY305306–11 | D. brevis | HQ718592 | 99/100 | |

| D. canis | 201 | 85.7 (6/7) | KY305312–17 | D. brevis | HQ718592 | 85/100 | |

| D. caprae | 228–230 | 71.4 (5/7) | KY305318–22 | D. brevis | HQ718592 | 90/100 | |

| D7 | D. farinae | 450–460 | 33.3 (2/6) | MH001334,36 | D. farinae | JQ000555 | 100/100 |

| P. cuniculi | 450–468 | 30.0 (3/10) | MH001343, MH001346, MH001347 | P. ovis | JQ000549 | 100/100 | |

| S. canis | 450–501 | 30.0 (3/10) | MH001349–51 | A. ocelatus | JQ000623 | 89/100 | |

| O. bacoti | 450 | 50.0 (5/10) | MH001338–42 | Laelapidae sp. | KP276392 | 96/100 | |

| C. malaccensis | 450 | 0/15 | – | – | – | – | |

| D. folliculorum | 450 | 0/15 | – | – | – | – | |

| D. brevis | 450 | 0/15 | – | – | – | – | |

| D. canis | 450 | 0/15 | – | – | – | – | |

| D. caprae | 450 | 0/15 | – | – | – | – | |

| D8 | D. farinae | 314 | 100 (5/5) | MH001240–44 | D. farinae | JQ000555 | 100/100 |

| P. cuniculi | 314 | 100 (5/5) | MH001250–54 | P. ovis | JQ000549 | 100/100 | |

| S. canis | 302–322 | 30.0 (3/10) | MH001229, MH001230, MH001234 | C. amazonae | KP325029 | 87/100 | |

| O. bacoti | 302 | 100 (5/5) | MH001245–49 | Laelapidae sp. | KP276392 | 95/100 | |

| C. malaccensis | 393 | 50.0 (5/10) | MH001235–39 | Oudemansicheyla sp. | KP276422 | 74/100 | |

| D. folliculorum | 519 | 100 (5/5) | KY305323–27 | D. folliculorum | HQ728004 | 100/100 | |

| D. brevis | 428–432 | 85.7 (6/7) | KY305328–33 | D. folliculorum | HQ728004 | 96/92 | |

| D. canis | 541–543 | 100 (5/5) | KY305334–38 | D. canis | HQ728002 | 99/100 | |

| D. caprae | 516 | 100 (6/6) | KY305339–44 | D. folliculorum | HQ728004 | 86/100 |

Abbreviations: DD, divergent domains; SR, sequencing success rate; CRS, closely related species; I/C, identity/coverage; D. farinae, Dermatophagoides farinae; P. cuniculi, Psoroptes cuniculi; S. canis, Sarcoptes scabiei canis; O. bacoti, Ornithonyssus bacoti; C. malaccensis, Cheyletus malaccensis; D. folliculorum, Demodex folliculorum; D. brevis, Demodex brevis; D. canis, Demodex canis; D. caprae, Demodex caprae; P. ovis, Psoroptes ovis; O. bursa, Ornithonyssus bursa; H. simplex, Haplochthonius simplex; H. holopus, Harpypalpus holopus; C. haematophagus, Chiroptonyssus haematophagus; C. amazonae, Chirnyssoides amazonae; A. ocelatus, Amerodectes aff. ocelatus

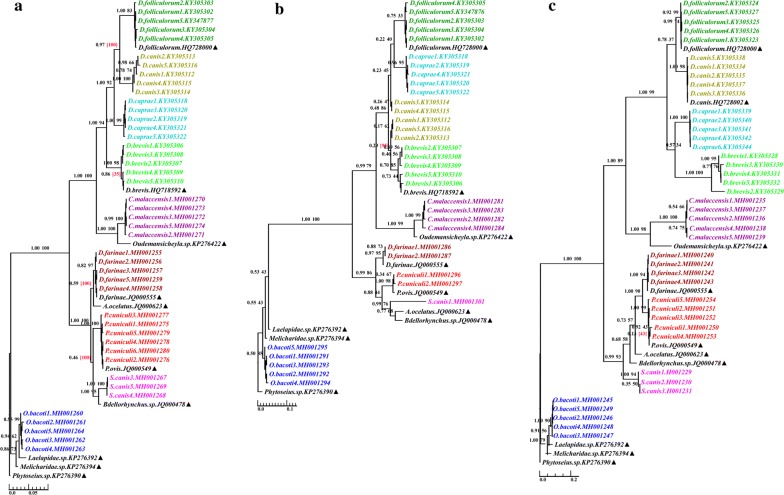

Phylogenetic relationships

The ML and BI trees based on 28S rDNA of D5, D6 and D8 yielded generally congruent topologies (Fig. 2). The bootstrap support (bs) and posterior probability (pp) values showed a similar trend, and posterior probability support was generally higher than bootstrap support, showing a more credible phylogenetic structure. The mites of the same species formed stable phylogenetic branches. The nine mite species formed distinct clusters within three major groups. The first group comprised the four Demodex species, C. malaccensis and the closely related species, all belonging to the Cheyletoidea in Acariformes (pp of 1.00, 0.99 and 1.00 in BI trees derived from D5, D6 and D8, respectively). The second group was formed by S. canis, P. cuniculi, D. farinae and the corresponding closely related species, all belonging to the Psoroptidia in Acariformes (pp of 1.00, 0.99 and 0.99 in BI trees derived from D5, D6 and D8, respectively). Ornithonyssus bacoti and its closely related species of Parasitiformes were clustered as a single group (pp of 1.00, 1.00 and 1.00 in BI trees derived from D5, D6 and D8, respectively). These clustering results were in accordance with the morphological identification.

Fig. 2.

Molecular phylogeny of the nine mite species and the closely related species based on data for the three divergent regions of 28S rDNA: D5 (a); D6 (b); D8 (c). Support values are shown above branches. The numbers in parentheses represent ML conflicting support values (which means the conflicting topology). Phytoseius sp. (GenBank: KP276390) was used as the outgroup. Triangles indicate sequences retrieved from GenBank

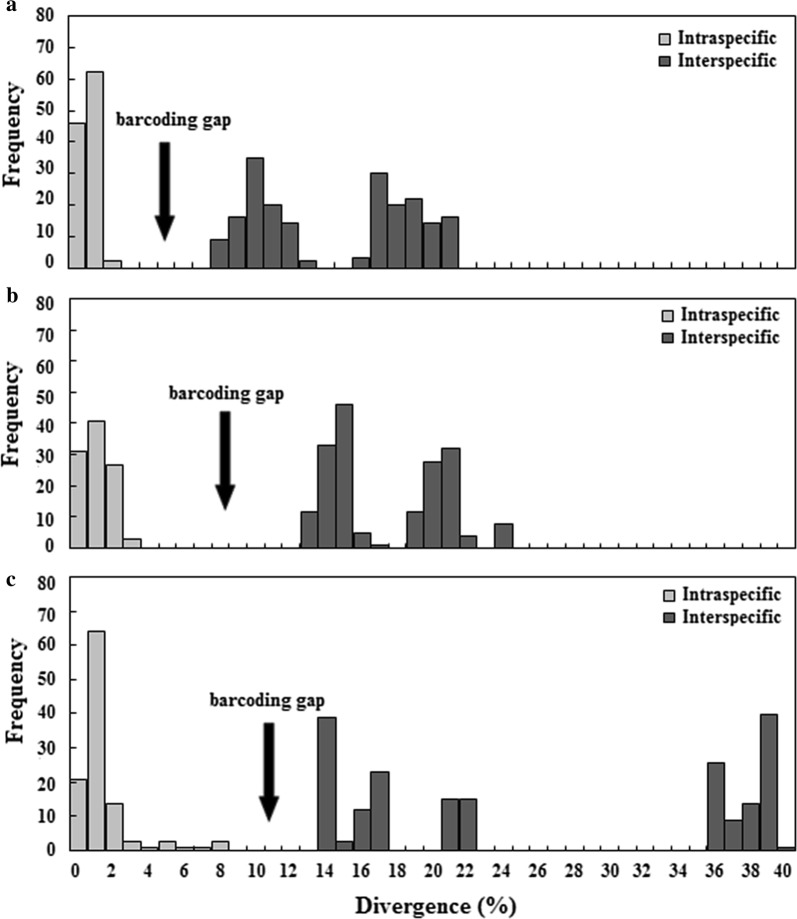

Comparison of DNA barcode candidates

Table 4 and Fig. 3 show the individual advantages of D5, D6 and D8 domains as DNA barcode candidates. The D5 domain had the smallest intraspecific divergences (0–1.26%), D6 had the largest DNA barcoding gap (10.54%) and the shortest length (192 bp), and D8 had the highest sequencing success rate (77.59%) and the longest indels (241 bp). Therefore, if the use of the three divergent regions was combined, they should complement each other, improving identification efficiency.

Table 4.

Comparison of the three DNA barcode candidates

| 28S | Intraspecific divergence (%) | Interspecific divergence (%) | DNA barcoding gap (%) | Length (bp) | Indel (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D5 | 0–1.26 | 7.46–20.51 | 6.20 (1.26–7.46) | 413–507 | 94 |

| D6 | 0–2.27 | 12.81–23.14 | 10.54 (2.27–12.81) | 192–241 | 49 |

| D8 | 0–7.18 | 13.10–38.75 | 5.92 (7.18–13.1) | 302–543 | 241 |

Fig. 3.

Frequency histogram plots of divergence for the three candidate DNA barcodes. a D5; b D6; c D8

Universality in acariformes and parasitiformes

A total of 225 almost complete 28S gene sequences for Acari were screened from GenBank, which belonged to 225 species of 40 families (186 species of 33 families in Acariformes and 39 species of 7 families in Parasitiformes) (Additional file 4: Table S1). The alignment results of the 225 sequences showed that the three pairs of primers designed for D5, D6 and D8 regions were universal, and base mutations were found in only two primers. The 11th base of the reverse primer (5′-TTG CTA CTA CCA CCA AGA TCT G-3′) of D6 was mutated from “T” to “C” in the Arrenuridae and Acaridae, and the 4th base of the forward primer (5′-GCA KCA GGT CTC CAA GG-3′) of D8 was mutated from “T” to “C” in the Gabuciniidae and Pterolichidae. Corresponding degenerate bases were utilized to replace the two mutation sites. Therefore, the primers for the D5, D6 and D8 regions of the 28S rRNA gene were also universal for the 225 species of 40 families in both Acariformes (Additional files 5: Figure S4, Additional file 6: Figure S5, Additional file 7: Figure S6) and Parasitiformes (Additional file 8: Figure S7).

Discussion

Considering that morphological identification of mites is difficult, and DNA identification is hampered by scarce molecular data, the present study provides three main insights. First, to the best of our knowledge, 28S rDNA was for the first time confirmed as the best potential candidate to be used in the identification and classification of 125 mites belonging to nine medically important mite species of six families. Domains D5, D6 and D8 were suitable DNA barcodes and each had its advantages. D5 had the smallest intraspecific divergences (0–1.26%), which is beneficial for identification of closely related species, while D6 showed the largest DNA barcoding gap (10.54%) between the intraspecific divergences (0–2.27%) and interspecific divergences (12.81–23.14%), which is beneficial for identification of distantly related species. Further, D8 had the highest sequencing success rate (77.59%) and the longest indels (241 bp), which enabled a preliminary discrimination of mite species using agarose-gel electrophoresis of PCR products, and if necessary, further sequencing and alignment could be performed for confirmation. Therefore, the combined use of the three divergent regions should be complementary and improve identification efficiency. Secondly, the universal primers or degenerate primers designed in the present study for D5, D6 and D8 domains had powerful expansibility. They were suitable not only for the identification of the nine medically important mite species, but also for 225 species of 40 families of Acariformes and Parasitiformes in Acari. Thirdly, the methods used in this study are worthy of much wider application and development. By retrieving and aligning molecular data of target genes from GenBank, the universality of the primers could be clearly defined. This provides new insights for molecular identification of thousands of other species besides Acari (which lack molecular data), and will contribute to the initiative of the International Barcode of Life (IBOL) programme.

IBOL was officially launched in 2009. The class Insecta, which comprises the largest number of species, forms the majority of the data in IBOL. The species currently active in IBOL include Lepidoptera (LepBOL), Trichoptera (TrichopteraBOL), Formicidae (FormicidaeBOL), bees (BeeBOL), trypetids (TBI), mosquitoes (MBI), invasive insects (INBIPS) and quarantine insects (QBOL). The medically important mites involved in this study belong to the Acari of arachnids. Although the DNA barcode programme for medically important mites and closely related species has been initiated with high priority, the application of DNA barcoding in mites is limited due to the large number of species, microscopic size, troublesome DNA extraction, and scarcity of specialist researchers. In particular, the lack of molecular data is the most prominent problem for most mite species. Motivated by the situation above, in the present study we successfully screened divergent regions of 28S rDNA as universal DNA barcodes for mites, based on bioinformatics analysis of the limited mtDNA and rDNA sequences of Acari retrieved from GenBank. This study will therefore have a strong effect on the execution of the DNA barcode programme for medically important mites and closely related species.

DNA barcoding was proposed by Canadian taxonomists Hebert et al. [48] in 2003. cox1 mtDNA 648-bp fragment was selected as a universal DNA barcode for global organisms, because it has the advantages of having maternal inheritance, low gene recombination incidence, sufficient mutation, and few indels. Based on the sequence alignment of the nine mite species tested, the present study found that although it could be used for molecular identification of different species, the primers lack universality as they were located at different positions. Even though the universal primers proposed by Herbert et al. [47] (F: 5′-GGT CAA CAA ATC ATA AAG ATA TTG G-3′; R: 5′-TAA ACT TCA GGG TGA CCA AAA AAT C-3′) aligned well with the primers for C. malaccensis and S. canis [26], in our study they were not universal for the remaining seven mite species belonging to the other four families. This result is not conducive to the feasibility of cox1 mtDNA recommended by IBOL for molecular identification of unknown mites. The analysis results for 16S and 12S mtDNA were similar to those for cox1 mtDNA.

ITS2 rDNA has also been used as a DNA barcode in the molecular identification and classification of some species of mite, such as flour mites, spider mites and gall mites [16, 19, 21], but is not appropriate for the Sarcoptes mites. Compared with cox1 and 16S mtDNA gene fragments, ITS2 rDNA could discriminate neither S. hominis from Sarcoptes spp. infesting animals nor different geographical populations of S. hominis as the intraspecific divergences and interspecific divergences almost completely overlapped without a clear DNA barcoding gap [26]. According to the sequence alignment results of the nine medically important mite species from six families, the ITS rDNA region is not a suitable DNA barcode because of the following three reasons. First, the primers for the medically important mites were located at different positions without universality. Secondly, ITS2 rDNA was too variable in sequence composition and sequence length to be aligned well. Thirdly, both the forward primer at the 5.8S region and the reverse primer at the 28S region were located at different positions in different mite species. Most importantly, the lack of sequences in some mite species conclusively proved that the ITS rDNA region is not suitable for designing universal primers.

Despite the fact that 18S and 28S, as nuclear genes, are rich in eukaryotes, they have not been considered to be suitable for identification and classification at lower taxonomic ranks (species and genus) due to the sequence conservation. However, the present study found that the divergent regions of 28S rDNA for mite species were more highly variable and rich in mutations, compared with 18S. In particular, domains D5, D6 and D8 exhibited good identification efficiency, effectively distinguishing species at both higher and lower taxonomic ranks. A significant barcoding gap was found between intraspecific divergences and interspecific divergences in the identification of the nine mite species. More importantly, the universal primers of these three divergent regions can be popularized to 225 species of 40 families in Acariformes and Parasitiformes.

Conclusions

In conclusion, domains D5, D6 and D8 of 28S rDNA are ideal areas to be used for molecular identification and classification of mites. The unique structure of the conserved regions and variable regions in the 18S, 28S and ITS regions could not only facilitate the design of universal primers, but also make rDNA suitable for classification and identification at different categories. Therefore, at the present stage, 28S rDNA, as a powerful supplement to cox1 mtDNA 648-bp fragment recommended by IBOL, could play a greater role in the molecular identification of mites.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Labeled primers of mtDNA gene fragments for mites involved in this study. acox1; b16S; c12S.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Labeled primers of rDNA regions for mites involved in this study. a ITS2; b18S.

Additional file 3: Figure S3. Labeled primers of 28S rDNA for mites involved in this study.

Additional file 4: Table S1. Information for 28S rDNA sequences involved in designing universal primers across Acari.

Additional file 5: Figure S4. Universal primers alignment of 28S rDNA D5 domain in 186 mite species of 33 families across Acariformes.

Additional file 6: Figure S5. Universal primers alignment of 28S rDNA D6 domain in 186 mite species of 33 families across Acariformes.

Additional file 7: Figure S6. Universal primers alignment of 28S rDNA D8 domain in 186 mite species of 33 families across Acariformes.

Additional file 8: Figure S7. Universal primers alignment of 28S rDNA domains D5, D6 and D8 in 39 mite species of 7 families across Parasitiformes. a D5; b D6; c D8.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- IBOL

International Barcode of Life

- 18S

small subunit ribosomal RNA gene

- 28S

large subunit ribosomal RNA gene

- rDNA

ribosomal DNA

- cox1

cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene

- ITS

internal transcribed spacer

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- BLAST

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- ML

maximum likelihood

- BI

Bayesian inference

- K2P

Kimura 2-parameter

- AIC

Akaike information criterion

- bs

bootstrap support

- pp

posterior probability

- LepBOL

Lepidoptera Barcode of Life

- TrichopteraBOL

Trichoptera Barcode of Life

- Formicidae BOL

Formicidae Barcode of Life

- BeeBOL

bees Barcode of Life Initiative

- TBI

Trypetid Barcode of Life Initiative

- MBI

mosquitoes Barcode of Life Initiative

- INBIPS

invasive insects Barcode of Life

- QBOL

quarantine insects Barcode of Life

Authors’ contributions

YEZ conceived and designed the study. RLW collected the samples and performed the experiments. YEZ, WYZ and DLN analyzed the data. YEZ, WYZ and DLN wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81471972).

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included in the article and its additional files. The newly generated sequences were submitted to the GenBank database under the accession numbers listed in Table 3.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yae Zhao, Email: zhaoyae@xjtu.edu.cn.

Wan-Yu Zhang, Email: 278992693@qq.com.

Rui-Ling Wang, Email: wangrl2015@stu.xjtu.edu.cn.

Dong-Ling Niu, Email: niudl2010@126.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13071-020-04124-z.

References

- 1.Zhao YE, Hu L, Ma JX. Molecular identification of four phenotypes of human Demodex mites (Acari: Demodecidae) based on mitochondrial 16S rDNA. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:3703–3711. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3558-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu L, Yang YJ, Zhao YE, Niu DL, Yang R, Wang RL, et al. DNA barcoding for molecular identification of Demodex based on mitochondrial genes. Parasitol Res. 2017;116:3285–3290. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5641-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lima DB, Rezende-Puker D, Mendonca RS, Tixier MS, Gondim MGC, Melo JWS, et al. Molecular and morphological characterization of the predatory mite Amblyseius largoensis (Acari: Phytoseiidae): surprising similarity between an Asian and American populations. Exp Appl Acarol. 2018;76:287–310. doi: 10.1007/s10493-018-0308-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holt DC, McCarthy JS, Carapetis JR. Parasitic diseases of remote indigenous communities in Australia. Int J Parasitol. 2010;40:1119–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu L, Zhao YE, Cheng J, Ma JX. Molecular identification of four phenotypes of human Demodex in China. Exp Parasitol. 2014;142:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shang XF, Miao XL, Lv HP, Wang DS, Zhang JQ, He H, et al. Acaricidal activity of usnic acid and sodium usnic acid against Psoroptes cuniculi in vitro. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:2387–2390. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3910-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chivers CA, Vineer HR, Wall R. The prevalence and distribution of sheep scab in Wales: a farmer questionnaire survey. Med Vet Entomol. 2018;32:244–250. doi: 10.1111/mve.12290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas WR, Smith WA, Hales BJ, Mills KL, O’Brien RM. Characterization and immunobiology of house dust mite allergens. Int Arch Allergy Imm. 2002;129:1–18. doi: 10.1159/000065179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhate R, Pansare N, Chaudhari SP, Barbuddhe SB, Choudhary VK, Kurkure NV, et al. Prevalence and phylogenetic analysis of Orientia tsutsugamushi in rodents and mites from central India. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017;17:749–754. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2017.2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao YE. A case report of human bitten by gamasid mites in the laboratory. Chin J Vector Biol Contr. 2017;28:304. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navajas M, Fenton B. The application of molecular markers in the study of diversity in acarology: a review. Exp Appl Acarol. 2000;24:751–774. doi: 10.1023/A:1006497906793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhowmick B, Zhao JG, Oines O, Bi TL, Liao CH, Zhang L, et al. Molecular characterization and genetic diversity of Ornithonyssus sylviarum in chickens (Gallus gallus) from Hainan Island, China. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:553. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3809-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blattner L, Gerecke R, Fumetti S. Hidden biodiversity revealed by integrated morphology and genetic species delimitation of spring dwelling water mite species (Acari, Parasitengona: Hydrachnidia) Parasit Vectors. 2019;1:492. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3750-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu L, Zhao YE, Yang YJ, Niu DL, Yang R. LSU rDNA D5 region: the DNA barcode for molecular classification and identification of Demodex. Genome. 2019;62:295–304. doi: 10.1139/gen-2018-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schatz H, Behan-Pelletier V. Global diversity of oribatids (Oribatida: Acari: Arachnida) Hydrobiologia. 2008;595:323–328. doi: 10.1007/s10750-007-9027-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li GQ, Xue XF, Zhang KJ, Hong XY. Identification and molecular phylogeny of agriculturally important spider mites (Acari: Tetranychidae) based on mitochondrial and nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences, with an emphasis on Tetranychus. Zootaxa. 2010;41:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skoracka A, Dabert M. The cereal rust mite Abacarus hystrix (Acari: Eriophyoidea) is a complex of species: evidence from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences. Bul Entomol Res. 2010;100:263–272. doi: 10.1017/S0007485309990216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dabert M, Bigos A, Witalinski W. DNA barcoding reveals andropolymorphism in Aclerogamasus species (Acari: Parasitidae) Zootaxa. 2011;3015:13–20. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3015.1.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang B, Cai JL, Cheng XJ. Identification of astigmatid mites using ITS2 and COI regions. Parasitol Res. 2011;108:497–503. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2153-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mironov SV, Dabert J, Dabert M. A new feather mite species of the genus Proctophyllodes Robin, 1877 (Astigmata: Proctophyllodidae) from the long-tailed tit Aegithalos caudatus (Passeriformes: Aegithalidae)-morphological description with DNA barcode data. Zootaxa. 2012;3253:54–61. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3253.1.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skoracka A, Kuczynski L, Mendonca RS, Dabert M, Szydlo W, Knihinicki D, et al. Cryptic species within the wheat curl mite Aceria tosichella (Keifer) (Acari: Eriophyoidea), revealed by mitochondrial, nuclear and morphometric data. Invertebr Syst. 2012;26:417–433. doi: 10.1071/IS11037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niedbala W, Dabert M. Madeira’s ptyctimous mites (Acari, Oribatida) Zootaxa. 2013;3664:571–585. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3664.4.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stalstedt J, Bergsten J, Ronquist F. “Forms” of water mites (Acari: Hydrachnidia): intraspecific variation or valid species? Ecol Evol. 2013;3:3415–3435. doi: 10.1002/ece3.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao YE, Cheng J, Hu L, Ma JX. Molecular identification and phylogenetic study of Demodex caprae. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:3601–3608. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-4025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szydlo W, Hein G, Denizhan E, Skoracka A. Exceptionally high levels of genetic diversity in wheat curl mite (Acari: Eriophyidae) populations from Turkey. J Econ Entomol. 2015;108:2030–2039. doi: 10.1093/jee/tov180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao YE, Cao ZG, Cheng J, Hu L, Ma JX, Yang YJ, et al. Population identification of Sarcoptes hominis and Sarcoptes canis in China using DNA sequences. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:1001–1010. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-4266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dabert J, Dabert M, Mironov SV. Phylogeny of feather mite subfamily Avenzoariinae (Acari: Analgoidea: Avenzoariidae) inferred from combined analyses of molecular and morphological data. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2001;20:124–135. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2001.0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Rojas M, Mora MD, Ubeda JM, Cutillas C, Navajas M, Guevara DC. Phylogenetic relationships in rhinonyssid mites (Acari: Rhinonyssidae) based on mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequences. Exp Appl Acarol. 2001;25:957–967. doi: 10.1023/A:1020651214274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navia D, Domingos CA, Mendonca RS, Ferragut F, Rodrigues MAN, Morais EGF, et al. Reproductive compatibility and genetic and morphometric variability among populations of the predatory mite, Amblyseius largoensis (Acari: Phytoseiidae), from Indian Ocean Islands and the Americas. Biol Control. 2014;72:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2014.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andriantsoanirina V, Ariey F, Izri A, Bernigaud C, Fang F, Guillot J, et al. Wombats acquired scabies from humans and/or dogs from outside Australia. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:2079–2083. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang XQ, Ye QT, Xin TR, Zou ZW, Xia B. Population genetic structure of Cheyletus malaccensis (Acari: Cheyletidae) in China based on mitochondrial COI and 12S rRNA genes. Exp Appl Acarol. 2016;69:117–128. doi: 10.1007/s10493-016-0028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mutisya DL, El-Banhawy EM, VicenteDosSantos V, Kariuki CW, Khamala CPM, Tixier MS. Predatory phytoseiid mites associated with cassava in Kenya, identification key and molecular diagnosis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) Acarologia. 2017;57:541–554. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin P, Dabert M, Dabert J. Molecular evidence for species separation in the water mite Hygrobates nigromaculatus Lebert, 1879 (Acari, Hydrachnidia): evolutionary consequences of the loss of larval parasitism. Aquatic Sci. 2010;72:347–360. doi: 10.1007/s00027-010-0135-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glowska E, Dragun-Damian A, Dabert J. DNA-barcoding contradicts morphology in quill mite species Torotrogla merulae and T. rubeculi (Prostigmata: Syringophilidae) Folia Parasitol. 2013;60:51–60. doi: 10.14411/fp.2013.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lehmitz R, Decker P. The nuclear 28S gene fragment D3 as species marker in oribatid mites (Acari, Oribatida) from German peatlands. Exp Appl Acarol. 2017;71:259–276. doi: 10.1007/s10493-017-0126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng J, Liu CC, Zhao YE, Hu L, Yang YJ, Yang F, et al. Population identification and divergence threshold in Psoroptidae based on ribosomal ITS2 and mitochondrial COI genes. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:3497–3507. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4578-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao YE, Wu LP. Phylogenetic relationships in Demodex mites (Acari: Demodicidae) based on mitochondrial 16S rDNA partial sequences. Parasitol Res. 2012;111:1113–1121. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-2941-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao YE, Hu L, Ma JX. Phylogenetic analysis of Demodex caprae based on mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequence. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:3969–3977. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3586-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colloff MJ. Taxonomy and identification of dust mites. Allergy. 1998;53:7–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1998.tb04989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gerson U. The Australian Cheyletidae (Acari: Prostigmata) Invertebr Syst. 1994;8:435–447. doi: 10.1071/IT9940435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Bio Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nylander JAA, Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP, Nieves-Aldrey JL. Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of combined data. Syst Biol. 2004;53:47–67. doi: 10.1080/10635150490264699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Posada D, Crandall KA. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Multimodel inference: understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociol Methods Res. 2004;33:261–304. doi: 10.1177/0049124104268644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stöver BC, Müller KF. TreeGraph 2: combining and visualizing evidence from different phylogenetic analyses. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hebert PDN, Cywinska A, Ball SL, deWaard JR. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2003;270:313–322. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hebert PDN, Ratnasingham S, deWaard JR. Barcoding animal life: cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 divergences among closely related species. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2003;270:S96–S99. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Labeled primers of mtDNA gene fragments for mites involved in this study. acox1; b16S; c12S.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Labeled primers of rDNA regions for mites involved in this study. a ITS2; b18S.

Additional file 3: Figure S3. Labeled primers of 28S rDNA for mites involved in this study.

Additional file 4: Table S1. Information for 28S rDNA sequences involved in designing universal primers across Acari.

Additional file 5: Figure S4. Universal primers alignment of 28S rDNA D5 domain in 186 mite species of 33 families across Acariformes.

Additional file 6: Figure S5. Universal primers alignment of 28S rDNA D6 domain in 186 mite species of 33 families across Acariformes.

Additional file 7: Figure S6. Universal primers alignment of 28S rDNA D8 domain in 186 mite species of 33 families across Acariformes.

Additional file 8: Figure S7. Universal primers alignment of 28S rDNA domains D5, D6 and D8 in 39 mite species of 7 families across Parasitiformes. a D5; b D6; c D8.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included in the article and its additional files. The newly generated sequences were submitted to the GenBank database under the accession numbers listed in Table 3.