Abstract

All causes of renal allograft injury, when severe and/or sustained, can result in chronic histological damage of which interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy are dominant features. Unless a specific disease process can be identified, what drives interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy progression in individual patients is often unclear. In general, clinicopathological factors known to predict and drive allograft fibrosis include graft quality, inflammation (whether “nonspecific” or related to a specific diagnosis), infections, such as polyomavirus-associated nephropathy, calcineurin inhibitors (CNI), and genetic factors. The incidence and severity of chronic histological damage have decreased substantially over the last 3 decades, but it is difficult to disentangle what effects individual innovations (eg, better matching and preservation techniques, lower CNI dosing, BK viremia screening) may have had. There is little evidence that CNI-sparing/minimization strategies, steroid minimization or renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade result in better preservation of intermediate-term histology. Treatment of subclinical rejections has only proven beneficial to histological and functional outcome in studies in which the rate of subclinical rejection in the first 3 months was greater than 10% to 15%. Potential novel antifibrotic strategies include antagonists of transforming growth factor-β, connective tissue growth factor, several tyrosine kinase ligands (epidermal growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor), endothelin and inhibitors of chemotaxis. Although many of these drugs are mainly being developed and marketed for oncological indications and diseases, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a number may hold promise in the treatment of diabetic nephropathy, which could eventually lead to applications in renal transplantation.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

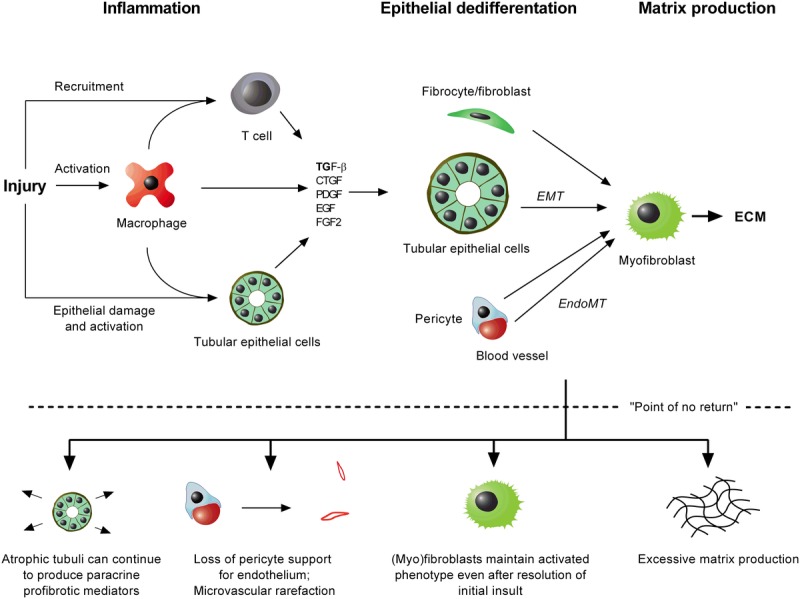

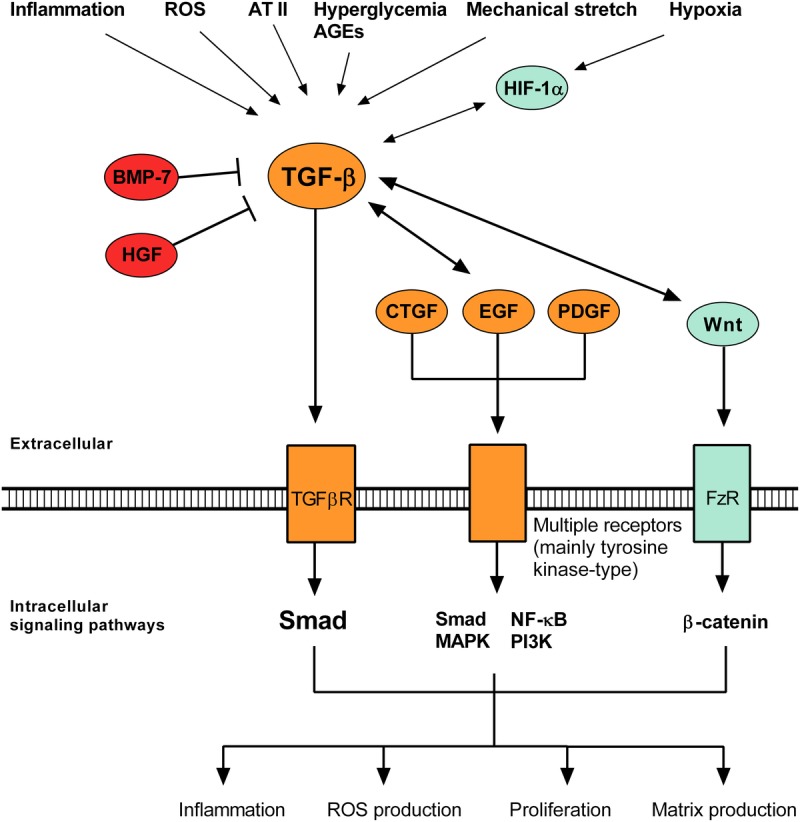

The basic mechanisms underlying renal allograft fibrosis are depicted in Figure 1. Interested readers are referred to several excellent in-depth reviews.1–3 In essence, most of the processes that cause renal injury result in an inflammatory cascade involving macrophage activation and recruitment of immune (mainly T) cells. Under the influence of inflammatory cytokines, several cell types including macrophages, T cells and tubular epithelial cells produce profibrotic mediators such as TGF-β.4 This results in activation of mesenchymal cells (fibroblasts, fibrocytes, and pericytes [which support the endothelium]) that then become contractile and matrix-producing myofibroblasts.5 At the same time, a wave of epithelial dedifferentiation occurs in which injured epithelial cells lose their polarity and transporter function, reorganize their cytoskeleton into stress fibers, disrupt the tubular basement membrane and migrate into the interstitium where they synthesize increasing amounts of extracellular matrix (ECM). Whether tubular epithelial and endothelial cells undergo the complete transformation to myofibroblasts (processes known as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [EMT] and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition) is not firmly established.5 The transformation of mesenchymal and epithelial cells to myofibroblasts is characterized by de novo production of α-smooth muscle actin, vimentin, S1004A, and the translocation of E-cadherin from the cell membrane to the cytoplasm. Some of the best-characterized profibrotic mediators and molecular pathways are summarized in Figure 2.

FIGURE 1.

Simplified diagram of renal fibrogenesis. Most injurious stimuli result in an inflammatory cascade characterized by recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells, as well as activation of damaged epithelial cells. All of these cell types produce not only proinflammatory but also profibrotic mediators that result in consecutive waves of epithelial dedifferentiation. Resident and recruited mesenchymal cells (fibrocytes, fibroblasts, pericytes) and possibly also epithelial cells (tubular and endothelial) transdifferentiate to become contractile myofibroblasts that produce ECM. When the injury is severe and/or persistent, eventually a point of no return may be reached beyond which fibrosis progresses on a local level even after resolution of injury. EndoMT, endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition; FGF, fibroblast growth factor.

FIGURE 2.

Canonical mediators and molecular pathways in renal fibrosis. Many injurious stimuli converge on the TGF-β pathway, which has context-dependent pleiotropic effects and interacts with several related pathways. AGEs, advanced glycation end products; BMP-7, bone morphogenetic protein 7; FzR, frizzled receptor; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

In normal wound repair, resolution of the initial injury is followed by wound contraction, ECM degradation, cessation of inflammation and restoration of normal tissue architecture. In case of persistent allograft injury, continued fibrogenesis ultimately results in irreversibly atrophied tubuli, excessive interstitial fibrosis (IF), microvascular rarefaction and glomerulosclerosis. It must be emphasized that progressive fibrosis almost invariably indicates continuing injury. Microarray studies of human renal allografts displaying IF have confirmed early and continued upregulation of genes related to immune activation, inflammation, fibrosis and remodeling, including TGF-β, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), mitogen-activated protein kinase, vimentin, α-smooth muscle actin, and matrix metalloproteinase-7.6–11 However, there seems to be a “point of no return” of structural injury, beyond which fibrosis progresses on a local level regardless of persisting injury. This has several reasons. (A) Even if the cause of renal injury is resolved, some atrophic tubuli do not recover and continue to produce paracrine profibrotic signals12; (B) arteriolar narrowing and microvascular rarefaction result in chronic hypoxia, which damages tubules and is potently profibrotic13; (C) myofibroblasts can maintain their activated phenotype after resolution of the initial insult.14 Importantly though, experimental (primarily nontransplant) chronic kidney disease models have revealed that fibrosis is only progressive on a local level.12 Fibrosis does not invade normal tissue. This is reflected by the sharp demarcation that is usually observed between fibrotic and normal areas in a kidney biopsy. This injury can be in any part of the nephron, as glomerulosclerosis, tubular damage, vascular rarefaction and obliteration all affect each other and ultimately result in a conglomerate of chronic histological lesions of which IF is only one of the hallmarks.

Finally, although fibrosis does not spread throughout the graft, each allograft has a limited reserve capacity beyond which structural and functional deterioration will progress in the absence of persistent injury. This occurs if nephron loss reaches a critical point, after which compensatory hyperfiltration results in hypertensive damage to the remaining glomeruli and proteinuria can result in sustained tubular injury. It is important to keep in mind that in a patient who, for example, receives a single 50-year old kidney that has sustained the injury of ischemia-reperfusion, this threshold of critical nephron loss may be reached relatively quickly.

The Clustering and Prognostic Value of Chronic Histological Lesions

In the Banff classification of renal allograft histology, the individual chronic lesions are IF (ci), tubular atrophy (TA) (ct), arterial fibrous intimal thickening (cv), arteriolar hyalinosis (ah), mesangial matrix increase (mm) and transplant glomerulopathy (cg).15 There is a high degree of clustering between all these lesions except transplant glomerulopathy,16 which is a unique pathologic entity with specific prognostic implications.17 IF and TA, in particular, almost invariably occur together18 and are often considered as the single parameter IF/TA (previously chronic allograft nephropathy). Because the tubulointerstitium comprises 90% of kidney volume, IF/TA is generally the most prominent manifestation of structural allograft deterioration. However, grouping IF/TA with other related chronic lesions better reflects the global burden of histological damage and better predicts graft outcome, at least in indication biopsies.16 This review uses the terms fibrosis and IF/TA virtually interchangeably as they both indicate an accumulation of chronic histological damage that is not specific to any type of renal injury.

IF/TA cannot be considered a disease but only the final common end point of countless disease processes and, by itself, it is hardly ever actionable. However, it may become actionable (regardless of or, preferably, in addition to disease-specific therapy) in the near future as targeted antifibrotic therapies are being developed. This is discussed in the second part of this review. In addition, IF/TA still has major prognostic implications. IF is the strongest histological predictor of graft outcome in native kidney glomerulonephritis.19 Similarly, IF/TA of the renal allograft (assessed using the Banff scoring system or by computerized quantification of IF) associates with worse renal function20,21 and predicts future functional decline as well as graft survival.21–25 IF/TA implies a worse prognosis independent of the underlying diagnosis (eg, T cell-mediated rejection and antibody-mediated rejection [AMR]).26,27 Consequently, even though identifying specific disease processes in a renal biopsy is a priority for prognostic and therapeutic reasons, IF/TA has additional value as a proxy for outcome and can help qualify/quantify the impact of factors that are detrimental to the graft. It is important to note that only moderate to severe fibrosis is predictive of outcome in most studies whereas mild fibrosis, even with extended follow-up, is not.28–31

The “Natural Evolution” of Allograft Histology

Much of the studies mentioned in this review are based on protocol or “surveillance” biopsy programs. These involve performing kidney biopsies at fixed time points in renal recipients with stable renal function and have provided much information regarding the natural evolution of graft histology.32–34 It must be noted, however, that these studies are inherently biased to some extent, with an overrepresentation of low-risk patients. Particularly at later time points, many patients are no longer biopsied because they have lost their graft, have developed medical comorbidities, refuse or are lost to follow-up. Additionally, few centers perform protocol biopsies later than 2 years after transplantation, so our knowledge of the evolution of graft histology beyond that point is relatively limited.

Regardless of these limitations, most protocol biopsy programs consistently report the same basic trend. Fibrosis develops in many patients during the first year after transplantation, but is generally mild.21,25,32,33,35–37 Most of this fibrosis is accumulated in the first 3 months, after which the rate of progression slows significantly. It is likely that this early accumulation of fibrosis mainly results from self-limiting inflammation related to implantation stress.38,39 Nevertheless, it will often continue to progress. In the seminal study by Nankivell et al32 (performed in kidney-pancreas recipients treated with relatively high-dose cyclosporine), moderate-severe IF/TA was present in 66% of patients by 5 years and 90% by 10 years after transplantation. More recent studies report significantly lower rates of fibrosis at all time points with only limited progression beyond 1 year in most patients, at least in the intermediate term.34,40 The prevalence of moderate-severe fibrosis at 5 years was only 17% in a large analysis of predominantly living-donor, tacrolimus (Tac) treated single kidney recipients from the Mayo clinic.34 Several aspects of patient care have evolved in parallel over the last 2 decades, which makes it difficult to disentangle what effect individual innovations may have had on reducing the accumulation of histological damage. These possibly beneficial changes include better preservation techniques, lower dosing of calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), CNI minimization strategies and the use of Tac rather than cyclosporine. On the other hand, these factors may have been partly offset by increasing use of kidneys of suboptimal quality (expanded-criteria donor, donation after cardiac death [DCD]) in many regions of the world. The next section discusses the available evidence regarding the factors that drive fibrosis in the renal allograft.

Quality of the Graft

Several factors determine the intrinsic quality of the graft and the damage it sustains as a result of ischemia-reperfusion injury. These include donor age, donor type (living vs deceased; donation after brain death (DBD) vs DCD, cold ischemia time and warm ischemia time. In the context of fibrosis, donor age is arguably the most important factor. Donor age is a key predictor of graft outcome,41 not only because it is a strong determinant of graft quality at implantation.42 High donor age is also independently and consistently associated with accelerated progression of chronic histologic damage (mainly IF/TA and chronic vasculopathy) as well as functional decline in the years after transplantation.25,32,37,43–45 The fact that older kidneys deteriorate faster regardless of baseline histology is likely to be partly explained by an age-related loss in renal regenerative capacity.46 Delayed graft function (DGF), a proxy for suboptimal graft quality and/or significant ischemia-reperfusion injury, consistently associates with higher degrees of IF/TA early after transplantation.38,47–50 Surgical anastomosis time has been shown to predict IF/TA independently of its effect on DGF.51 The individual effects of cold ischemia time and donor type (living vs deceased) on early and long-term IF/TA, however, are not as consistent among studies.20,21,33,37,52

Inflammation

There is no doubt that inflammation in a renal allograft is a potent and, arguably, the most studied predictor of subsequent allograft fibrosis. Protocol biopsy studies performed on patients transplanted in the late 1980s and 1990s identified early biopsy-proven acute rejection (BPAR) as a risk factor for IF/TA.32,35,53,54 In this review, the term BPAR refers to clinical acute rejections (ie, accompanied by graft dysfunction). Subclinical rejections (SCR) are defined as histologic acute rejection in the absence of graft dysfunction. Borderline rejections do not meet the Banff criteria for acute rejection and can be either clinical or subclinical. Rush et al were among the first to report that early SCR, too, was independently predictive of IF/TA.55 Several groups have since reported accelerated progression of IF/TA related to BPAR,56 any rejection of at least Banff t2i2 severity (clinical or subclinical),21,57,58 any rejection of at least Banff t1i1 severity (ie, including borderline rejections [Banff ’97 criteria])59 and even just higher Banff i score on a 1-year protocol biopsy.60 Early acute rejections and (subclinical) inflammation also predict future development of de novo donor-specific antibodies (dnDSA) and chronic AMR, which are powerful predictors of graft loss.59,61–63 Not all groups have confirmed this.64 Two trends are noteworthy. First, just as the incidence and severity of BPARs has strongly decreased since the late 1980s, so has SCR become less frequent (reviewed by Mehta et al).65 Three-month SCR rates were often around 25% to 40% in earlier studies,36,57 whereas recently, they are generally < 10%.37,45,50,66 There is convincing evidence that SCR rates are lowered by Tac (compared with cyclosporine [CsA])24,32,63,64,67 and adequately dosed mycophenolate mofetil (MMF).68,69 Use of induction therapy, however, has not been proven to lower the risk of SCR. In fact, the opposite has been reported in a trial of low-risk pediatric patients.70 Second, there are indications that SCR has become a better predictor of IF/TA progression than BPAR. With modern immunosuppression, most early BPARs are mild, steroid-responsive and have no negative impact on graft outcome if renal function recovers after treatment71 or no histological damage is sustained,59 though they may still predispose to later dnDSA development.59 Some recent studies have reported that subclinical inflammation had a larger effect on IF/TA progression37,45,50,72 and dnDSA development63 than BPAR. The underlying reasons for these observations are not completely clear, but the fact that BPARs are systematically treated while borderline rejections and subclinical mild inflammation, in many centers, are not, could be a factor. However, steroids frequently do not result in complete resolution of subclinical inflammation73 and whether treating it has long-term benefits is still a matter of debate (see below).

There is evidence that the presence of inflammation, even below the threshold for borderline rejection, discriminates between fibrosis that is inactive scar tissue and fibrosis that reflects an underlying progressive (albeit poorly defined) process. Studies performed in the Mayo clinic demonstrated that, in low-risk renal recipients, fibrosis plus interstitial inflammation predicted poor graft survival but mild fibrosis without inflammation did not.31,74,75 The same has been reported for “IF/TA + SCR.”76 Persistence of low-grade inflammation in repeated protocol biopsies might be particularly detrimental.77,78

MAKING SENSE OF NONSPECIFIC INFLAMMATION

The goal of any histological evaluation of the renal allograft, whether for cause or per protocol, should be to identify specific diagnoses. By the time the graft fails, this is generally possible,26,79 but early (particularly protocol) biopsies will often demonstrate nonspecific IF/TA and relatively low-grade, nonspecific tubulitis and interstitial inflammation. The biological nature and long-term impact of these infiltrates is unclear: even though many are probably actual mild rejections or at least manifestations of alloimmune injury, it is likely that some of them are merely resorptive inflammatory responses. A key future challenge will be differentiating between types of inflammation, that is, separating harmful alloimmune activation from resorptive, nondetrimental or even beneficial (tolerogenic) immune activity.

First, every effort must be made to exclude a specific disease process by combining histological, clinical and laboratory information. For example, subclinical AMR (suggested by presence of DSA, glomerulitis, peritubular capillaritis, and/or C4d deposition) is more potently profibrotic and carries a worse prognosis80 in comparison with nonspecific subclinical inflammation.81 In late for-cause biopsies (>1 year), the detrimental effect of inflammation very often results from its association with progressive diseases such as AMR and recurrent glomerulonephritis.82

Second, severe inflammation is strongly suggestive of detrimental alloimmune injury. For example, acute rejection ≥ Banff grade IIA (arteritis or “v” score > 0) seems mostly incompatible with stable renal function as it is very rare in protocol biopsies.45,57,78 In less severe cases, however, light microscopy might not provide an accurate estimate of the severity of inflammation. Microarray studies have revealed significant upregulation of genes related to immunity, inflammation, remodeling and fibrosis in allografts indication biopsies displaying IF/TA,8,11,83 biopsies with IF/TA but no histological inflammation83,84 and even in completely normal protocol biopsies.84 Many of these immune-related gene sets are shared with acute rejection,83 indicating the presence of significant inflammatory and fibrotic activity even in the absence of clear histological inflammation. Microarray studies have also revealed qualitative and quantitative differences in gene expression between BPAR and SCR,85 between borderline rejections with and without graft dysfunction,44 and between early biopsies that later developed IF/TA or did not.11,86 In the future, gene expression analysis could be a promising strategy to differentiate between detrimental and harmless infiltrates and, by extension, determine which should be treated. Microarray studies have already been used to identify molecular signatures that predicted graft loss in indication biopsies87 and IF/TA progression in early protocol biopsies88 better than traditional clinicopathological risk factors.

Third, what renal compartments are inflamed? In the Banff classification, interstitial inflammation is scored in unscarred areas (i-Banff), but not in scarred areas (i-IF/TA), subcapsular cortex or adventitia around large vessels because these are not considered specific for acute rejection (the diagnosis of which was the original raison d’être for the Banff classification).15 There have, however, been reports that i-IF/TA is an independent predictor of IF/TA progression in 3-month protocol biopsies89 and graft loss90 in late for-cause biopsies. Total-i (inflammation in all scarred and unscarred cortical tissue) has also been reported to be a better predictor of graft survival than i-Banff.91 Total-i in 6-week protocol biopsies was not predictive of IF/TA progression by 1 year,92 although this does not necessarily contradict the previous findings, as inflammation at 6 weeks likely mainly reflects the injury response after implantation stress.39 It must be noted that i-IF/TA is very highly correlated with i-Banff90 and with the severity of IF/TA,82,93 that is, severely fibrotic areas contain more inflammatory cells. This is in agreement with the concept of fibrosis as a process that, beyond a certain threshold of severity, becomes self-perpetuating on a local level. Mannon et al90 noted that i-IF/TA in the absence of i-Banff almost never occurred, whereas others found that every protocol biopsy with fibrosis and i-Banff also had a total-i score > 0.74 Additional studies at different time points after transplantation will need to examine the precise prognostic value i-IF/TA after correction for i-Banff and fibrosis (which not all studies performed).

Fourth, what types of immune cells are present? In routine evaluation of renal allograft pathology, no differentiation is made between the various mononuclear cells (T cells, B cells, natural killer cells, dendritic cells and monocytes/macrophages) so they all contribute to the scoring of inflammation. Even though T cells are generally the most abundant infiltrating cells, histologically similar infiltrates may be composed of very different types of immune cells. In general, severe acute rejections are more heterogeneous15,94,95 and infiltrates with a higher proportion (or activity) of immune cells that are not “regular” T cells seem to portend a worse prognosis. There is convincing evidence regarding the negative prognostic value of natural killer cells (due to a strong association with AMR),96 dendritic cells97,98 and macrophages.99–101 Macrophage infiltration/activation has been reported to be more pronounced in severe compared with mild and subclinical acute rejections99,102 and to correlate with tubular dysfunction, chronic histological damage as well as with concurrent and future renal dysfunction,99–101 although this is not a consistent finding.103 The prognostic relevance of high B- and plasma cell infiltration in adults is unclear.103–106 Their presence and activity are strongly related to post transplant time,107–109 which may confound their relationship with graft outcome: late (often nonadherence) rejections often have a humoral component and have a worse prognosis compared with early rejections.110 The prognostic value of the T cell subsets of FOXP3 expressing regulatory T (Treg) cells in infiltrates is also unclear. Treg cells are crucial for containing inflammation, maintaining self- and donor-specific tolerance and play a central role in most tolerance inducing regimens in rodent models of allogeneic transplantation.111 However, FOXP3 may also be transiently expressed by activated CD4 cells that have no suppressor activity.112 Some reports have indicated that FOXP3 expression mainly mirrors the general degree of inflammation and FOXP3 expression in acute rejections carries no prognostic benefit.113,114 Others have reported that high urinary FOXP3 mRNA during acute rejections predicted better outcome,115 that there were proportionally more Treg cells in subclinical versus clinical rejection (compatible with successful damage control)116,117 and that their presence predicted better long-term renal outcome.117–121 Most studies showing a benefit of Treg cells used immunohistochemistry to quantify their presence as it has been argued that mRNA may be too sensitive.117 Treg cells are also more common in mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor–based regimens, which may partly confound their association with better estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).118,120 Finally, not only the infiltrate but also properties of the graft microenvironment play a role. For example, tubular cells overexpressing protease inhibitor 9 may be better protected against the action of cytotoxic T cells.122

Infections

Polyomavirus-associated nephropathy (PVAN), when untreated, results in rapid accumulation of IF/TA.123 Even with adequate reduction of immunosuppression, a history of PVAN has been associated with higher degrees of IF/TA in subsequent protocol biopsies21,50,75 and increases the risk of graft loss.26 When PVAN is diagnosed early through BK viremia screening and/or protocol biopsy programs, however, IF/TA is typically less severe at diagnosis.124 Furthermore, prompt reduction of immunosuppression in case of BK viremia seems to prevent further accumulation of IF/TA in sequential biopsies125 and is associated with excellent intermediate-term outcomes.126 In summary, the chronic lesions present at the time of PVAN diagnosis are irreversible, but early detection and correct management likely prevent further structural and functional decline.

Other viral infections including human herpesvirus 6/7, Epstein-Barr virus and particularly cytomegalovirus (CMV) have been associated with more severe IF/TA in concurrent127 and subsequent biopsies,128 as well as accelerated eGFR decline.49,129 However, causality has not been firmly established as CMV viremia is also strongly related to poor intrinsic graft quality.130 In a large retrospective study, patients who developed a CMV infection already had higher IF/TA on early protocol biopsies that were often performed before the CMV infection.131 Furthermore, occurrence of CMV did not predict future IF/TA progression or graft loss.

Immunosuppressive Therapy

CNIs have acute nephrotoxic effects, primarily resulting from hemodynamic alterations (vasoconstriction of the afferent arterioles) and reversible tubular dysfunction.132 Long-term exposure to CNIs, on the other hand, leads to irreversible damage to all compartments of the kidney.133,134 CNIs mediate this chronic nephrotoxicity through a variety of mechanisms: chronic vasoconstriction and arteriolar narrowing result in persistent local hypoxia; stimulation of reactive oxygen species production135,136 and chronic renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) stimulation, which has profibrotic effects.137 CNIs also seem to have direct cytotoxic effects on tubular cells, induce EMT-like changes138,139 and stimulate TGF-β production.140,141 Although the nephrotoxic effects of CNIs are well established, the morphological changes typically associated with their long-term use (IF/TA, de novo arteriolar hyalinosis, glomerular capsular fibrosis, glomerulosclerosis and tubular microcalcifications) are all nonspecific.132 As a result, how much the toxic and direct profibrotic effects of CNIs contribute to IF/TA accumulation remains unclear. Evidence regarding the effect of various CNI sparing/avoiding regimens on graft histology is discussed under “Therapeutic strategies to minimize progression of fibrosis”.

Genetic Factors

Genetically determined variation in genes relevant to alloimmunity, injury response, drug metabolism and fibrosis could have an influence on graft prognosis. For example, 1 study reported better long-term renal allograft outcome in recipients carrying the complement C3 slow/slow allotypes who received a fast/slow or fast/fast kidney.142 In the context of allograft fibrosis, genetic polymorphisms in 2 genes are specifically worth mentioning: ABCB1 (also MDR1, coding for P-glycoprotein) and CAV1 (coding for caveolin-1). P-glycoprotein is a wide-substrate efflux pump that is present on many epithelia including intestine, bile ducts and kidney tubules. It limits the intestinal absorption and facilitates renal elimination of various compounds including toxins and xenobiotics like CNIs. Early studies identified a link between reduced expression of P-glycoprotein at the apical side of tubular cells and increased CNI nephrotoxicity in rat models143 and human renal allografts,144,145 presumably resulting from higher intracellular concentrations of CNIs and possibly their metabolites. On the other hand, animal models suggest that P-glycoprotein deficiency protects against renal injury, which may be related to its anti-apoptotic properties.146 The net effect of loss-of-function ABCB1 SNPs (particularly C3435T147) on long-term renal function and histology remains unclear, as later studies have reported conflicting results.37,148–152 Specifically, Moore et al found that the wild-type donor CC genotype was associated with an increased risk of graft failure in a large cohort of (mainly CsA-treated) renal recipients. Bloch et al similarly reported that the loss-of-function T genotype independently predicted less fibrosis and less evidence of EMT on 3-month protocol biopsies in 140 Tac-treated patients. In contrast, in a protocol biopsy study of 252 Tac-treated patients by Naesens et al, a combined donor-recipient TT genotype independently predicted more severe IF/TA and worse renal function in the first 3 years after transplantation.

Caveolin-1, the primary structural component of caveolae, has antifibrotic properties related to its role in internalizing the TGF-β receptor.153 Presence of the donor AA genotype for the rs4730751 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in CAV1 independently predicted graft failure in 2 large cohorts of renal recipients.154 No protocol biopsies were performed, but 155/184 of failed grafts had a late for-cause biopsy. The incidence of IF/TA was higher in the AA group (59% vs 26%).

Therapeutic Strategies to Minimize Progression of Fibrosis

Because of the multifactorial etiology and nonspecific nature of fibrosis, all interventions aimed at minimizing damage to the allograft (such as controlling hypertension and hyperglycemia, optimal matching, reducing ischemia time and early recognition of PVAN) can be considered “antifibrotic” We focus on a few strategies that potentially interfere directly with major fibrotic pathways.

CNI SPARING/AVOIDING REGIMENS

As mentioned earlier, retrospective reports indicate that IF/TA severity is lower with modern (low-dose) Tac-based regimens compared with older (high-dose) CsA-based regimens, but other differences between the transplant eras could contribute to these observations (eg, screening for PVAN, better matching and preservation techniques, differences in induction regimens). Where possible, we will focus on the best available evidence: randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing different immunosuppressive regimens in which protocol biopsies were performed.

Belatacept

In the BENEFIT study of belatacept versus CsA, both belatacept arms had better renal function and lower prevalence of (mainly mild) IF/TA on 1-year protocol biopsies (20-29%) compared with the CsA arm (44%).155 Microarray analysis of a small subgroup of 1-year biopsies from the BENEFIT and BENEFIT-EXT showed that the CsA group was enriched for gene sets associated with fibrosis and chronic allograft injury.156 Comparative data with Tac in that regard are currently lacking.

CsA versus Tac

An RCT of CsA versus Tac (with high CNI target trough levels and use of azathioprine only for DCD kidneys) reported more fibrosis in the CsA group at 1 year, despite similar rates of acute rejection.157 However, 2 RCTs of Tac versus CsA using modern regimens (lower CNI dose, basiliximab induction, MMF and steroids) could not confirm this.24,64

Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Inhibitors

Two RCTs have shown that, in renal recipients treated with CsA-sirolimus(SRL)-steroids, stopping CsA at month 3 results in less IF/TA and better renal function at 1 and 3 years.158,159 However, this may be related to the fact that SRL aggravates the nephrotoxicity of CsA by increasing local tissue concentrations, an effect that is less pronounced for the combination Tac-SRL.160,161 A third study showed that Tac-SRL and CsA-SRL resulted in lower rates of clinical and SCR, as well as significantly less IF/TA accumulation over 5 years compared with Tac-MMF or CsA-MMF.162 Early steroid withdrawal in all patients, high CNI target trough levels in MMF-treated patients and high rates of DGF limit the generalizability of these findings. There is no consistent evidence that substituting SRL for a CNI or using Tac-SRL combinations is beneficial for the intermediate-term histological evolution of the graft.6,163–165 Finally, for Tac-MMF versus SRL-MMF, 1 trial reported higher rates of subclinical inflammation and moderate-severe IF/TA in the Tac-MMF group at 2 years (steroids were avoided),166 although a second study found no difference in 1-year IF/TA.167

Steroid Minimization

Early steroid withdrawal and steroid avoidance have been linked with an increased risk of mild rejections in CsA-based regimens,168 which could theoretically accelerate IF/TA progression. This has, however, not been assessed with protocol biopsy studies. For Tac-based regimens, early steroid withdrawal/avoidance is not associated with differences in the incidence of clinical rejection, SCR or the accumulation of IF/TA.43,169,170

CNI Exposure

The Symphony study established that the combination of low-dose Tac, MMF, steroids and daclizumab resulted in lower rates of acute rejection, better graft survival and better graft function at 1 and 3 years after transplantation compared with low-dose CsA, standard-dose CsA or low-dose SRL-based immunosuppression.171,172 The impact of CNI exposure on graft histology is not as clear. Studies have reported both high and low CsA exposure to be an independent predictor of IF/TA accumulation by 1 to 2 years.53,173,174 Similarly, Tac exposure is not consistently related to progression of IF/TA. Results of retrospective studies vary from no association30,45 to more IF/TA with low trough levels56 and less IF/TA with low trough levels.175 We recently found that high Tac exposure did not predict IF/TA or progression of chronicity score on 2-year protocol biopsies.45 Rather, high intrapatient variability in Tac trough levels was an independent predictor of increase in chronicity score, which has also been noted for CsA.174,176 This seems logical, as strongly fluctuating trough levels can lead to periods of overexposure (which might be profibrotic) as well as underexposure (which can result in surges in alloimmune activation that are also profibrotic). Intrapatient variability is strongly related to nonadherence, which itself has also been shown to predict IF/TA.177 We can conclude that there is insufficient evidence to suggest that, within the range of Tac trough levels commonly used today, any particular trough level target is associated with better preservation of renal histology in the short term. More generally, no immunosuppressive regimen has demonstrated better evolution of histology compared with the current standard-of-care, Tac-based triple therapy.

BLOCKADE OF THE RAAS

The RAAS has potent profibrotic effects, in part through renin-, angiotensin II- and aldosterone-mediated activation of the TGF-β system.178 In renal transplantation, however, it is not well established whether RAAS blockade slows the progression of fibrosis or improves graft or patient survival. Large retrospective analyses provided conflicting results regarding the effect of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) on graft loss and mortality,179–182 and a recent RCT in proteinuric renal recipients showed no benefit of ramipril on a combined endpoint of doubling of serum creatinine, end-stage renal disease (ESRD) or death after 4 years of treatment.183

With regard to histology, Rush et al performed a post-hoc analysis of an RCT in which renal recipients were randomized to standard care or a protocol biopsy program, with treatment of SCR only in the protocol biopsy arm. Use of ACE-I or ARB at any time in a subgroup of patients independently predicted less IF/TA progression between months 6 and 24.33 In nonalbuminuric, nontransplanted type I diabetics randomized to losartan, enalapril or placebo, there was no functional renal benefit and no difference in the increase in interstitial fractional volume at 5 years.184 Finally, an RCT of losartan versus placebo in renal recipients demonstrated that the odds ratio for doubling of fraction of renal cortical volume occupied by interstitium between baseline and 5 years was 0.39 for losartan, although the effect was only borderline significant (P = 0.08).185 To summarize: although ACE-I and ARB have antifibrotic properties in addition to reducing proteinuria and hyperfiltration, whether this translates into long-term structural and functional benefits in renal transplantation has yet to be established. The available prospective studies showed no convincing benefit, possibly because they mainly included low-risk patients and did not always correct for other profibrotic drivers such as inflammation.

TREATMENT OF SCR

Most transplant centers that perform protocol biopsies treat subclinical acute rejections with high-dose steroids, as they would a clinical acute rejection. The approach to subclinical borderline rejection is more variable: often left untreated, decided case-by-case in some centers and treated almost systematically in others. Indeed, the belief that treating SCR has long-term benefits is arguably the strongest clinical argument for having a protocol biopsy program in the first place. The evidence, however, is not ironclad. A seminal study by Rush et al randomized renal recipients to undergo repeat protocol biopsies (with treatment of SCR) or no biopsies except at months 6 and 12 (blinded).36 Patients were treated with high-dose CsA-azathioprine-steroids; almost none received induction therapy. The incidence of SCR was 30% to 40% in the first 2 months, and the biopsy group had lower IF/TA at 6 months, less late acute rejections, better renal function and better graft survival at 2 years. However, a follow-up study with very similar design in low-risk renal recipients treated with Tac-MMF-steroids (no induction), showed no benefit of treatment with regards 6-month IF/TA or renal function.48 This was attributed to the very low overall incidence of SCR (4.6%). A retrospective analysis of patients treated with basiliximab-CNI-MMF-steroids showed that untreated SCR on 6-month protocol biopsies (incidence 7.4%) had no effect on the severity of 1-year fibrosis.42 Finally, another prospective study randomized renal recipients, almost all without previous induction therapy, to undergo protocol biopsies at 1 and 3 months. Treatment of SCR (incidence 12-17.3%) was associated with better renal function at 1 year.186 Borderline rejections had a similar outcome to no rejection. In summary, treating SCR has only proven beneficial to short-term structural and functional outcome in studies that did not use induction therapy, with an incidence of SCR greater than 10% to 15% in the first 3 months after transplantation. Long-term follow-up data are not available. Given the extensive evidence regarding the detrimental effect of SCR, we believe treatment is justifiable. However, the effect is not likely to be dramatic, and proving that a “SCR treatment” strategy is beneficial to a low-risk population (Tac-based triple therapy and systematic induction) with a low incidence of SCR would likely require an exceedingly large RCT. Given that the rate of serious complications from protocol biopsies is <0.5%187 and the rate of SCR in our center is 8% to 10% at 3 months, we perform protocol biopsies as we believe that the possible benefits of performing (treating early inflammation) outweigh the risks in our particular setting. Additionally, SCR is not the only actionable finding in protocol biopsies, as patients without significant inflammation at 3 months are weaned off steroids. There is, however, no evidence to support the latter strategy. There may also be a “window of opportunity” for protocol biopsies between 1 and 4 months, as much subclinical inflammation will have subsided spontaneously by 6 months (which does not mean it cannot have damaged the graft during that period). There are no data on whether subclinical borderline rejections should be treated. Even if it is assumed that many borderline rejections are predominantly on the mild end of a continuum of alloimmune injury, the potential benefit of treating them is likely to be even smaller.

VITAMIN D SUPPLEMENTATION

Chronic kidney disease models suggest that vitamin D may protect against inflammation, EMT and fibrosis.188 However, in a retrospective analysis comparing 64 renal recipients receiving vitamin D with historic controls that did not take vitamin D, there was no difference in evolution of eGFR or IF/TA between months 3 and 12 after transplantation.189 It is clear that a prospective study with longer histologic follow-up would be needed to definitively settle this issue.

POTENTIAL FUTURE STRATEGIES

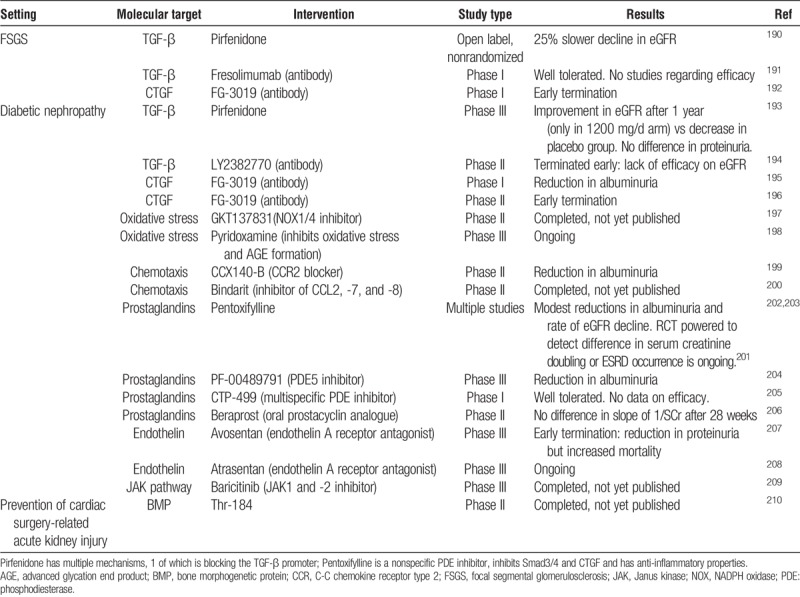

Novel antifibrotic interventions tested in human renal disease are summarized in Table 1. Many more molecules have shown promise in preclinical models; these are reviewed in detail elsewhere.211–214 The preclinical pipeline does not seem to be a problem, and neither is there a lack of interest from industry in antifibrotic drugs per se. Rather, bringing specific antifibrotic interventions to the clinic has proved very challenging, even in prototypical fibrotic disease states such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and systemic sclerosis, where these drugs are potentially lifesaving.215,216 This could have several reasons. Many profibrotic molecules also have beneficial effects, depending on the context. A typical example is the anti-inflammatory and antineoplastic effects of TGF-β, which could limit the benefits of systemic TGF-β antagonism.217,218 Downstream mediators of TGF-β, such as CTGF and the tyrosine kinase ligands (epidermal growth factor [EGF], platelet-derived growth factor [PDGF], vascular endothelial growth factor), are less pleiotropic but these pathways are at least partly redundant.219 Blocking several profibrotic pathways in parallel may be the best way to avoid escape phenomena, but could increase the probability of adverse effects. Finally, a crucial question in any fibrotic disease, and renal allograft pathology in particular, is how much can be gained from halting maladaptive tissue repair mechanisms and excessive matrix deposition if there is continuing underlying epithelial injury and inflammation. On the other hand, there are numerous factors that directly stimulate TGF-β (eg, CNIs, angiotensin II, hyperglycemia) and they might respond well to specific targeting of this pathway.

TABLE 1.

Studies of renal antifibrotic interventions in humans

Apart from a pilot study of renal recipients with chronic allograft nephropathy in which pentoxifylline reduced proteinuria in some patients,220 none of these drugs have been tested in renal transplantation. It is likely that most renal antifibrotic therapies will first be tested in diabetic nephropathy, as this is a large market with a homogeneous and strongly TGF-β-dependent disease process.221 The pleiotropic molecule pentoxifylline seems to reduce albuminuria and eGFR decline in diabetic nephropathy, although the results of a RCT powered to detect differences in ESRD occurrence and serum creatinine doubling are awaited.201 Pirfenidone, which is licensed for IPF, could be promising for diabetic nephropathy193 but no large RCT has currently been undertaken.

Overall, there are very few studies of novel antifibrotic drugs being performed in the setting of renal disease. Studies using the anti-CTGF monoclonal antibody FG-3019 for focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS)192 and diabetic nephropathy196 were terminated early. The focus seems to have shifted to other nonrenal indications including IPF222 and oncology,223,224 which is true for several other pipeline drugs. Particularly promising are several tyrosine kinase inhibitors (including EGF and PDGF antagonists), which are very well established antifibrotic strategies in preclinical models211 and have been studied extensively in human oncology, but have also never been tested in human (nonmalignant) renal disease. This may be partly related to the fact that side effect profiles acceptable in an oncological context will often be perceived as problematic for long-term use in transplant recipients. The multi-target tyrosine kinase inhibitor nintedanib is modestly effective and licensed for IPF,215 but to our knowledge, no trials of nintedanib or any other tyrosine kinase inhibitor are currently being performed in renal disease.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Like all organs, the renal allograft responds to a wide variety of injurious stimuli by highly conserved and stereotypical injury-response mechanisms that result in a limited number of chronic histological lesions. IF/TA is usually a dominant feature of chronic damage and carries major prognostic implications, but it is particularly nonspecific. The difficulty in tracing these generic histological features back to their underlying disease processes remains a key challenge in transplantation. As our knowledge regarding specific disease processes and the maladaptive tissue repair mechanisms that exacerbate their detrimental effects expands, novel therapeutic strategies are likely to emerge that prolong graft survival and improve quality of life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Evelyne Lerut for sharing her insights regarding renal allograft pathology in clinical practice.

Footnotes

The authors declare no funding or conflicts of interest.

T.V. wrote the article. R.G. and D.K. reviewed the article.

Correspondence: Dirk R J Kuypers, MD, PhD, Department of Nephrology and Renal Transplantation, University Hospitals Leuven, Herestraat 49, 3000 Leuven, Belgium. (dirk.kuypers@uzleuven.be).

Although the cause of fibrosis in renal allografts is nonspecific, fibrosis is a dominant feature of severe acute or chronic injury with poor prognostic implications and current strategies to prevent or control fibrosis are lacking and thus requiring novel therapeutic strategies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wynn TA, Ramalingam TR. Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease Nat Med 2012. 181028–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meng XM, Nikolic-paterson DJ, Lan HY. Inflammatory processes in renal fibrosis Nat Rev Nephrol 2014. 10493–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boor P, Floege J. Renal allograft fibrosis: biology and therapeutic targets Am J Transplant 2015. 15863–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of renal fibrosis Nat Rev Nephrol 2011. 7684–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falke LL, Gholizadeh S, Goldschmeding R. Diverse origins of the myofibroblast—implications for kidney fibrosis Nat Rev Nephrol 2015. 11233–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flechner SM, Kurian SM, Solez K. De novo kidney transplantation without use of calcineurin inhibitors preserves renal structure and function at two years Am J Transplant 2004. 41776–1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hotchkiss H, Chu TT, Hancock WW. Differential expression of profibrotic and growth factors in chronic allograft nephropathy Transplantation 2006. 81342–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mas V, Maluf D, Archer K. Establishing the molecular pathways involved in chronic allograft nephropathy for testing new noninvasive diagnostic markers Transplantation 2007. 83448–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carvajal G, Droguett A, Burgos ME. Gremlin: a novel mediator of epithelial mesenchymal transition and fibrosis in chronic allograft nephropathy Transplant Proc 2008. 40734–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rödder S, Scherer A, Raulf F. Renal allografts with IF/TA display distinct expression profiles of metzincins and related genes Am J Transplant 2009. 9517–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vitalone MJ, O’Connell PJ, Wavamunno M. Transcriptome changes of chronic tubulointerstitial damage in early kidney transplantation Transplantation 2010. 89537–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venkatachalam MA, Weinberg JM, Kriz W. Failed tubule recovery, AKI-CKD transition, and kidney disease progression J Am Soc Nephrol 2015. 261765–1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heyman SN, Khamaisi M, Rosen S. Renal parenchymal hypoxia, hypoxia response and the progression of chronic kidney disease Am J Nephrol 2008. 28998–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bechtel W, McGoohan S, Zeisberg EM. Methylation determines fibroblast activation and fibrogenesis in the kidney Nat Med 2010. 16544–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Racusen LC, Solez K, Colvin RB. The Banff 97 working classification of renal allograft pathology Kidney Int 1999. 55713–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naesens M, Kuypers DR, De Vusser K. Chronic histological damage in early indication biopsies is an independent risk factor for late renal allograft failure Am J Transplant 2013. 1386–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cosio FG, Gloor JM, Sethi S. Transplant glomerulopathy Am J Transplant 2008. 8492–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sis B, Einecke G, Chang J. Cluster analysis of lesions in nonselected kidney transplant biopsies: microcirculation changes, tubulointerstitial inflammation and scarring Am J Transplant 2010. 10421–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohle A, Wehrmann M, Bogenschütz O. The long-term prognosis of the primary glomerulonephritides. A morphological and clinical analysis of 1747 cases Pathol Res Pract 1992. 188908–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwarz A, Mengel M, Gwinner W. Risk factors for chronic allograft nephropathy after renal transplantation: a protocol biopsy study Kidney Int 2005. 67341–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cosio FG, Grande JP, Larson TS. Kidney allograft fibrosis and atrophy early after living donor transplantation Am J Transplant 2005. 51130–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nankivell BJ, Fenton-Lee CA, Kuypers DR. Effect of histological damage on long-term kidney transplant outcome Transplantation 2001. 71515–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grimm PC, Nickerson P, Gough J. Computerized image analysis of Sirius Red-stained renal allograft biopsies as a surrogate marker to predict long-term allograft function J Am Soc Nephrol 2003. 141662–1668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roos-van Groningen MC, Scholten EM, Lelieveld PM. Molecular comparison of calcineurin inhibitor-induced fibrogenic responses in protocol renal transplant biopsies J Am Soc Nephrol 2006. 17881–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Servais A, Meas-Yedid V, Noël LH. Interstitial fibrosis evolution on early sequential screening renal allograft biopsies using quantitative image analysis Am J Transplant 2011. 111456–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naesens M, Kuypers DR, De Vusser K. The histology of kidney transplant failure: a long-term follow-up study Transplantation 2014. 98427–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.John R, Konvalinka A, Tobar A. Determinants of long-term graft outcome in transplant glomerulopathy Transplantation 2010. 90757–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serón D, Moreso F, Fulladosa X. Reliability of chronic allograft nephropathy diagnosis in sequential protocol biopsies Kidney Int 2002. 61727–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pape L, Henne T, Offner G. Computer-assisted quantification of fibrosis in chronic allograft nephropathy by picosirius red-staining: a new tool for predicting long-term graft function Transplantation 2003. 76955–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cosio FG, Grande JP, Wadei H. Predicting subsequent decline in kidney allograft function from early surveillance biopsies Am J Transplant 2005. 52464–2472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cosio FG, El Ters M, Cornell LD. Changing kidney allograft histology early posttransplant: prognostic implications of 1-year protocol biopsies Am J Transplant 2016. 16194–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nankivell BJ, Borrows RJ, Fung CL. The natural history of chronic allograft nephropathy N Engl J Med 2003. 3492326–2333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rush DN, Cockfield SM, Nickerson PW. Factors associated with progression of interstitial fibrosis in renal transplant patients receiving tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil Transplantation 2009. 88897–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stegall MD, Park WD, Larson TS. The histology of solitary renal allografts at 1 and 5 years after transplantation Am J Transplant 2011. 11698–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solez K, Vincenti F, Filo RS. Histopathologic findings from 2-year protocol biopsies from a U.S. multicenter kidney transplant trial comparing tacrolimus versus cyclosporine: a report of the FK506 Kidney Transplant Study Group Transplantation 1998. 661736–1740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rush D, Nickerson P, Gough J. Beneficial effects of treatment of early subclinical rejection: a randomized study J Am Soc Nephrol 1998. 92129–2134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naesens M, Lerut E, de Jonge H. Donor age and renal P-glycoprotein expression associate with chronic histological damage in renal allografts J Am Soc Nephrol 2009. 202468–2480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuypers DR, Chapman JR, O’Connell PJ. Predictors of renal transplant histology at three months Transplantation 1999. 671222–1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mengel M, Chang J, Kayser D. The molecular phenotype of 6-week protocol biopsies from human renal allografts: reflections of prior injury but not future course Am J Transplant 2011. 11708–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nankivell BJ, P’Ng CH, O’Connell PJ. Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity through the lens of longitudinal histology: comparison of cyclosporine and tacrolimus eras Transplantation 2016. 1001723–1731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nickerson P, Jeffery J, Gough J. Identification of clinical and histopathologic risk factors for diminished renal function 2 years posttransplant J Am Soc Nephrol 1998. 9482–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scholten EM, Rowshani AT, Cremers S. Untreated rejection in 6-month protocol biopsies is not associated with fibrosis in serial biopsies or with loss of graft function J Am Soc Nephrol 2006. 172622–2632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naesens M, Salvatierra O, Benfield M. Subclinical inflammation and chronic renal allograft injury in a randomized trial on steroid avoidance in pediatric kidney transplantation Am J Transplant 2012. 122730–2743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hrubá P, Brabcová I, Gueler F. Molecular diagnostics identifies risks for graft dysfunction despite borderline histologic changes Kidney Int 2015. 88785–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vanhove T, Vermeulen T, Annaert P, et al. High intrapatient variability of tacrolimus concentrations predicts accelerated progression of chronic histologic lesions in renal recipients. Am J Transplant. 2016:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmitt R, Melk A. New insights on molecular mechanisms of renal aging Am J Transplant 2012. 122892–2900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naesens M, de Loor H, Vanrenterghem Y. The impact of renal allograft function on exposure and elimination of mycophenolic acid (MPA) and its metabolite MPA 7-O-glucuronide Transplantation 2007. 84362–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rush D, Arlen D, Boucher A. Lack of benefit of early protocol biopsies in renal transplant patients receiving TAC and MMF: a randomized study Am J Transplant 2007. 72538–2545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reischig T, Jindra P, Bouda M. Effect of cytomegalovirus viremia on subclinical rejection or interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy in protocol biopsy at 3 months in renal allograft recipients managed by preemptive therapy or antiviral prophylaxis Transplantation 2009. 87436–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heilman RL, Devarapalli Y, Chakkera HA. Impact of subclinical inflammation on the development of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy in kidney transplant recipients Am J Transplant 2010. 10563–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heylen L, Naesens M, Jochmans I. The effect of anastomosis time on outcome in recipients of kidneys donated after brain death: a cohort study Am J Transplant 2015. 152900–2907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yilmaz S, McLaughlin K, Paavonen T. Clinical predictors of renal allograft histopathology: a comparative study of single-lesion histology versus a composite, quantitative scoring system Transplantation 2007. 83671–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Serón D, Moreso F, Bover J. Early protocol renal allograft biopsies and graft outcome Kidney Int 1997. 51310–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yilmaz S, Tomlanovich S, Mathew T. Protocol core needle biopsy and histologic Chronic Allograft Damage Index (CADI) as surrogate end point for long-term graft survival in multicenter studies J Am Soc Nephrol 2003. 14773–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rush D, Jeffery J, Trpkov K. Effect of subclinical rejection on renal allograft histology and function at 6 months Transplant Proc 1996. 28494–495 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naesens M, Lerut E, Damme BV. Tacrolimus exposure and evolution of renal allograft histology in the first year after transplantation Am J Transplant 2007. 72114–2123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nankivell BJ, Borrows RJ, Fung CL. Natural history, risk factors, and impact of subclinical rejection in kidney transplantation Transplantation 2004. 78242–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lerut E, Naesens M, Kuypers DR. Subclinical peritubular capillaritis at 3 months is associated with chronic rejection at 1 year Transplantation 2007. 831416–1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.El Ters M, Grande JP, Keddis MT. Kidney allograft survival after acute rejection, the value of follow-up biopsies Am J Transplant 2013. 132334–2341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hertig A, Anglicheau D, Verine J. Early epithelial phenotypic changes predict graft fibrosis J Am Soc Nephrol 2008. 191584–1591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moreso F, Carrera M, Goma M. Early subclinical rejection as a risk factor for late chronic humoral rejection Transplantation 2012. 9341–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wiebe C, Gibson IW, Blydt-Hansen TD. Evolution and clinical pathologic correlations of de novo donor-specific HLA antibody post kidney transplant Am J Transplant 2012. 121157–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.García-Carro C, Dörje C, Åsberg A, et al. Inflammation in early kidney allograft surveillance biopsies with and without associated tubulointerstitial chronic damage as a predictor of fibrosis progression and development of de novo donor specific antibodies. Transplantation. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rowshani AT, Scholten EM, Bemelman F. No difference in degree of interstitial Sirius red-stained area in serial biopsies from area under concentration-over-time curves-guided cyclosporine versus tacrolimus-treated renal transplant recipients at one year J Am Soc Nephrol 2006. 17305–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mehta R, Sood P, Hariharan S. Subclinical rejection in renal transplantation: reappraised Transplantation 2016. 1001610–1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mengel M, Bogers J, Bosmans JL. Incidence of C4d stain in protocol biopsies from renal allografts: results from a multicenter trial Am J Transplant 2005. 51050–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moreso F, Serón D, Carrera M. Baseline immunosuppression is associated with histological findings in early protocol biopsies Transplantation 2004. 781064–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Choi BS, Shin MJ, Shin SJ. Clinical significance of an early protocol biopsy in living-donor renal transplantation: ten-year experience at a single center Am J Transplant 2005. 51354–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hymes LC, Warshaw BL, Hennigar RA. Prevalence of clinical rejection after surveillance biopsies in pediatric renal transplants: does early subclinical rejection predispose to subsequent rejection episodes? Pediatr Transplant 2009. 13823–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Offner G, Toenshoff B, Höcker B. Efficacy and safety of basiliximab in pediatric renal transplant patients receiving cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, and steroids Transplantation 2008. 861241–1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meier-Kriesche HU, Schold JD, Srinivas TR. Lack of improvement in renal allograft survival despite a marked decrease in acute rejection rates over the most recent era Am J Transplant 2004. 4378–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thierry A, Thervet E, Vuiblet V. Long-term impact of subclinical inflammation diagnosed by protocol biopsy one year after renal transplantation Am J Transplant 2011. 112153–2161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kee TY, Chapman JR, O’Connell PJ. Treatment of subclinical rejection diagnosed by protocol biopsy of kidney transplants Transplantation 2006. 8236–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Park WD, Griffin MD, Cornell LD. Fibrosis with inflammation at one year predicts transplant functional decline J Am Soc Nephrol 2010. 211987–1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gago M, Cornell LD, Kremers WK. Kidney allograft inflammation and fibrosis, causes and consequences Am J Transplant 2012. 121199–1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moreso F, Ibernon M, Gomà M. Subclinical rejection associated with chronic allograft nephropathy in protocol biopsies as a risk factor for late graft loss Am J Transplant 2006. 6747–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shishido S, Asanuma H, Nakai H. The impact of repeated subclinical acute rejection on the progression of chronic allograft nephropathy J Am Soc Nephrol 2003. 141046–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mengel M, Gwinner W, Schwarz A. Infiltrates in protocol biopsies from renal allografts Am J Transplant 2007. 7356–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.El-Zoghby ZM, Stegall MD, Lager DJ. Identifying specific causes of kidney allograft loss Am J Transplant 2009. 9527–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Haas M, Montgomery RA, Segev DL. Subclinical acute antibody-mediated rejection in positive crossmatch renal allografts Am J Transplant 2007. 7576–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Loupy A, Vernerey D, Tinel C. Subclinical rejection phenotypes at 1 year post-transplant and outcome of kidney allografts J Am Soc Nephrol 2015. 261721–1731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sellarés J, de Freitas DG, Mengel M. Inflammation lesions in kidney transplant biopsies: association with survival is due to the underlying diseases Am J Transplant 2011. 11489–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Modena BD, Kurian SM, Gaber LW. Gene expression in biopsies of acute rejection and interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy reveals highly shared mechanisms that correlate with worse long-term outcomes Am J Transplant 2016. 161982–1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Park W, Griffin M, Grande JP. Molecular evidence of injury and inflammation in normal and fibrotic renal allografts one year posttransplant Transplantation 2007. 831466–1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hoffmann SC, Hale DA, Kleiner DE. Functionally significant renal allograft rejection is defined by transcriptional criteria Am J Transplant 2005. 5573–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Scherer A, Gwinner W, Mengel M. Transcriptome changes in renal allograft protocol biopsies at 3 months precede the onset of interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy (IF/TA) at 6 months Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009. 242567–2575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Einecke G, Reeve J, Sis B. A molecular classifier for predicting future graft loss in late kidney transplant biopsies J Clin Invest 2010. 1201862–1872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.O’Connell PJ, Zhang W, Menon MC. Biopsy transcriptome expression profiling to identify kidney transplants at risk of chronic injury: a multicentre, prospective study Lancet 2016. 388983–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nankivell BJ, Borrows RJ, Fung CL. Delta analysis of posttransplantation tubulointerstitial damage Transplantation 2004. 78434–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mannon RB, Matas AJ, Grande J. Inflammation in areas of tubular atrophy in kidney allograft biopsies: a potent predictor of allograft failure Am J Transplant 2010. 102066–2073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mengel M, Reeve J, Bunnag S. Scoring total inflammation is superior to the current Banff inflammation score in predicting outcome and the degree of molecular disturbance in renal allografts Am J Transplant 2009. 91859–1867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dörje C, Reisaeter AV, Dahle DO. Total inflammation in early protocol kidney graft biopsies does not predict progression of fibrosis at one year post-transplant Clin Transplant 2016. 30802–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mengel M, Reeve J, Bunnag S. Molecular correlates of scarring in kidney transplants: the emergence of mast cell transcripts Am J Transplant 2009. 9169–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang PL, Malek SK, Prichard JW. Acute cellular rejection predominated by monocytes is a severe form of rejection in human renal recipients with or without Campath-1H (alemtuzumab) induction therapy Am J Transplant 2005. 5604–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Magil AB, Tinckam K. Monocytes and peritubular capillary C4d deposition in acute renal allograft rejection Kidney Int 2003. 631888–1893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Resch T, Fabritius C, Ebner S. The role of natural killer cells in humoral rejection Transplantation 2015. 991335–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zuidwijk K, de Fijter JW, Mallat MJ. Increased influx of myeloid dendritic cells during acute rejection is associated with interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy and predicts poor outcome Kidney Int 2012. 8164–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Batal I, De Serres SA, Safa K. Dendritic cells in kidney transplant biopsy samples are associated with T cell infiltration and poor allograft survival J Am Soc Nephrol 2015. 263102–3113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Girlanda R, Kleiner DE, Duan Z. Monocyte infiltration and kidney allograft dysfunction during acute rejection Am J Transplant 2008. 8600–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Toki D, Zhang W, Hor KL. The role of macrophages in the development of human renal allograft fibrosis in the first year after transplantation Am J Transplant 2014. 142126–2136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bergler T, Jung B, Bourier F. Infiltration of macrophages correlates with severity of allograft rejection and outcome in human kidney transplantation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Grimm PC, McKenna R, Nickerson P. Clinical rejection is distinguished from subclinical rejection by increased infiltration by a population of activated macrophages J Am Soc Nephrol 1999. 101582–1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Moreso F, Seron D, O’Valle F. Immunephenotype of glomerular and interstitial infiltrating cells in protocol renal allograft biopsies and histological diagnosis Am J Transplant 2007. 72739–2747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bagnasco SM, Tsai W, Rahman MH. CD20-positive infiltrates in renal allograft biopsies with acute cellular rejection are not associated with worse graft survival Am J Transplant 2007. 71968–1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kayler LK, Lakkis FG, Morgan C. Acute cellular rejection with CD20-positive lymphoid clusters in kidney transplant patients following lymphocyte depletion Am J Transplant 2007. 7949–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Scheepstra C, Bemelman FJ, van der Loos C. B cells in cluster or in a scattered pattern do not correlate with clinical outcome of renal allograft rejection Transplantation 2008. 86772–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Desvaux D, Le Gouvello S, Pastural M. Acute renal allograft rejections with major interstitial oedema and plasma cell-rich infiltrates: high gamma-interferon expression and poor clinical outcome Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004. 19933–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Einecke G, Reeve J, Mengel M. Expression of B cell and immunoglobulin transcripts is a feature of inflammation in late allografts Am J Transplant 2008. 81434–1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gupta R, Sharma A, Mahanta PJ. Plasma cell-rich acute rejection of the renal allograft: a distinctive morphologic form of acute rejection? Indian J Nephrol 2012. 22184–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Opelz G, Döhler B. Influence of time of rejection on long-term graft survival in renal transplantation Transplantation 2008. 85661–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ochando JC, Homma C, Yang Y. Alloantigen-presenting plasmacytoid dendritic cells mediate tolerance to vascularized grafts Nat Immunol 2006. 7652–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wang J, Ioan-Facsinay A, van der Voort EI. Transient expression of FOXP3 in human activated nonregulatory CD4+ T cells Eur J Immunol 2007. 37129–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Veronese F, Rotman S, Smith RN. Pathological and clinical correlates of FOXP3+ cells in renal allografts during acute rejection Am J Transplant 2007. 7914–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bunnag S, Allanach K, Jhangri GS. FOXP3 expression in human kidney transplant biopsies is associated with rejection and time post transplant but not with favorable outcomes Am J Transplant 2008. 81423–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Muthukumar T, Dadhania D, Ding R. Messenger RNA for FOXP3 in the urine of renal-allograft recipients N Engl J Med 2005. 3532342–2351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Grimbert P, Mansour H, Desvaux D. The regulatory/cytotoxic graft-infiltrating T cells differentiate renal allograft borderline change from acute rejection Transplantation 2007. 83341–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Taflin C, Nochy D, Hill G. Regulatory T cells in kidney allograft infiltrates correlate with initial inflammation and graft function Transplantation 2010. 89194–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bestard O, Cruzado JM, Rama I. Presence of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells predicts outcome of subclinical rejection of renal allografts J Am Soc Nephrol 2008. 192020–2026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zuber J, Brodin-Sartorius A, Lapidus N. FOXP3-enriched infiltrates associated with better outcome in renal allografts with inflamed fibrosis Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009. 243847–3854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bestard O, Cuñetti L, Cruzado JM. Intragraft regulatory T cells in protocol biopsies retain Foxp3 demethylation and are protective biomarkers for kidney graft outcome Am J Transplant 2011. 112162–2172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Xu Y, Jin J, Wang H. The regulatory/cytotoxic infiltrating T cells in early renal surveillance biopsies predicts acute rejection and survival Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012. 272958–2965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Rowshani AT, Florquin S, Bemelman F. Hyperexpression of the granzyme B inhibitor PI-9 in human renal allografts: a potential mechanism for stable renal function in patients with subclinical rejection Kidney Int 2004. 661417–1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ramos E, Drachenberg CB, Wali R. The decade of polyomavirus BK-associated nephropathy: state of affairs Transplantation 2009. 87621–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Buehrig CK, Lager DJ, Stegall MD. Influence of surveillance renal allograft biopsy on diagnosis and prognosis of polyomavirus-associated nephropathy Kidney Int 2003. 64665–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Menter T, Mayr M, Schaub S. Pathology of resolving polyomavirus-associated nephropathy Am J Transplant 2013. 131474–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hardinger KL, Koch MJ, Bohl DJ. BK-virus and the impact of pre-emptive immunosuppression reduction: 5-year results Am J Transplant 2010. 10407–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sebeková K, Feber J, Carpenter B. Tissue viral DNA is associated with chronic allograft nephropathy Pediatr Transplant 2005. 9598–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tong CY, Bakran A, Peiris JS. The association of viral infection and chronic allograft nephropathy with graft dysfunction after renal transplantation Transplantation 2002. 74576–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Smith JM, Corey L, Bittner R. Subclinical viremia increases risk for chronic allograft injury in pediatric renal transplantation J Am Soc Nephrol 2010. 211579–1586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Erdbruegger U, Scheffner I, Mengel M. Impact of CMV infection on acute rejection and long-term renal allograft function: a systematic analysis in patients with protocol biopsies and indicated biopsies Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012. 27435–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Erdbrügger U, Scheffner I, Mengel M. Long-term impact of CMV infection on allografts and on patient survival in renal transplant patients with protocol biopsies Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2015. 309F925–F932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Naesens M, Kuypers DR, Sarwal M. Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009. 4481–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Feutren G, Mihatsch MJ. Risk factors for cyclosporine-induced nephropathy in patients with autoimmune diseases. International Kidney Biopsy Registry of Cyclosporine in Autoimmune Diseases N Engl J Med 1992. 3261654–1660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Isnard Bagnis C, Tezenas du Montcel S, Beaufils H. Long-term renal effects of low-dose cyclosporine in uveitis-treated patients: follow-up study J Am Soc Nephrol 2002. 132962–2968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Klawitter J, Gottschalk S, Hainz C. Immunosuppressant neurotoxicity in rat brain models: oxidative stress and cellular metabolism Chem Res Toxicol 2010. 23608–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Krauskopf A, Lhote P, Petermann O. Cyclosporin A generates superoxide in smooth muscle cells Free Radic Res 2005. 39913–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Lee DB. Cyclosporine and the renin-angiotensin axis Kidney Int 1997. 52248–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.McMorrow T, Gaffney MM, Slattery C. Cyclosporine A induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005. 202215–2225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Pallet N, Bouvier N, Bendjallabah A. Cyclosporine-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress triggers tubular phenotypic changes and death Am J Transplant 2008. 82283–2296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Prashar Y, Khanna A, Sehajpal P. Stimulation of transforming growth factor-beta 1 transcription by cyclosporine FEBS Lett 1995. 358109–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Slattery C, Campbell E, McMorrow T. Cyclosporine A-induced renal fibrosis: a role for epithelial-mesenchymal transition Am J Pathol 2005. 167395–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Brown KM, Kondeatis E, Vaughan RW. Influence of donor C3 allotype on late renal-transplantation outcome N Engl J Med 2006. 3542014–2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.del Moral RG, Andujar M, Ramírez C. Chronic cyclosporin A nephrotoxicity, P-glycoprotein overexpression, and relationships with intrarenal angiotensin II deposits Am J Pathol 1997. 1511705–1714 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Koziolek MJ, Riess R, Geiger H. Expression of multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein in kidney allografts from cyclosporine A-treated patients Kidney Int 2001. 60156–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Joy MS, Nickeleit V, Hogan SL. Calcineurin inhibitor-induced nephrotoxicity and renal expression of P-glycoprotein Pharmacotherapy 2005. 25779–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Huls M, Kramers C, Levtchenko EN. P-glycoprotein-deficient mice have proximal tubule dysfunction but are protected against ischemic renal injury Kidney Int 2007. 721233–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kimchi-Sarfaty C, Oh JM, Kim IW. A “silent” polymorphism in the MDR1 gene changes substrate specificity Science 2007. 315525–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Metalidis C, Lerut E, Naesens M. Expression of CYP3A5 and P-glycoprotein in renal allografts with histological signs of calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity Transplantation 2011. 911098–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]