Abstract

Background

Erectile dysfunction has been associated with atrial fibrillation in cross-sectional studies, but the association of erectile dysfunction with incident atrial fibrillation is less well established.

Purpose

To determine whether erectile dysfunction is independently associated with incident atrial fibrillation after adjusting for conventional risk factors.

Methods

We studied 1760 male participants (mean age 68 ± 9 years) from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), who completed self-reported erectile dysfunction assessment at MESA Exam 5 (2010–2012). Cumulative incidence of atrial fibrillation was estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to calculate the unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) using three models in which variables were added in a stepwise manner. In Model 3, HR was adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education, smoking status, alcohol use, systolic blood pressure, body mass index, diabetes, anti-hypertensive medication use, lipid-lowering medication use, total cholesterol, and estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Results

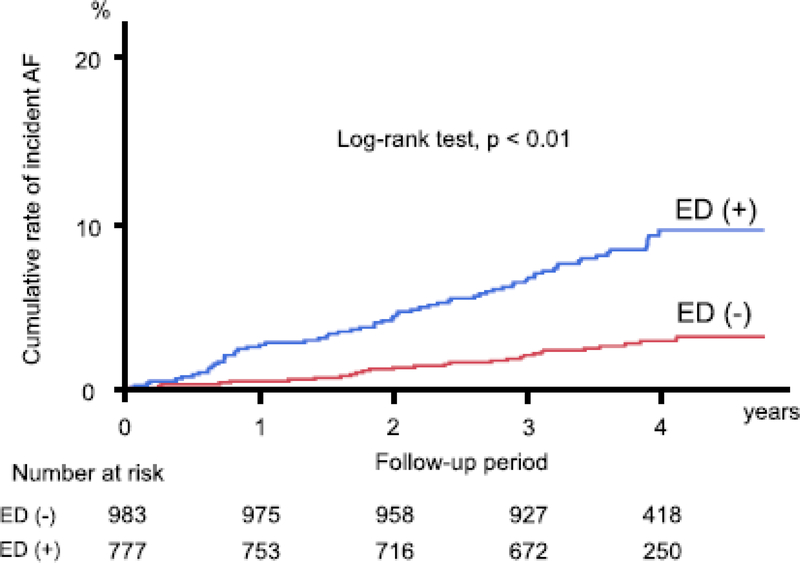

During the median follow-up of 3.8 (interquartile range, 3.5 – 4.2) years, 94 cases of incident atrial fibrillation were observed. There was a significant difference between men with and without erectile dysfunction for cumulative incident atrial fibrillation rates at 4 years (9.6 vs 2.9%, respectively, p < 0.01). In the fully adjusted model, erectile dysfunction remained associated with incident atrial fibrillation (Model 3; HR, 1.66; 95% Confidence Interval 1.01 – 2.72, p = 0.044).

Conclusions

Among older male participants in this prospective study, we found that self-reported erectile dysfunction was associated with incident atrial fibrillation.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Erectile dysfunction, Atherosclerosis

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation is one of the most clinically important tachyarrhythmias and the prevalence increases with aging. Complications of atrial fibrillation include embolic stroke or heart failure, both of which are life-threatening and increase socioeconomic burden.(1) Although the mechanisms of atrial fibrillation are not fully known, endothelial dysfunction due to atherosclerosis is considered to play a vital role.(2) Furthermore, inflammation and prothrombotic factors are known to be elevated in patients with atrial fibrillation, and they also might contribute to endothelial dysfunction and thrombus formation in the left atrium.(2, 3) Several risk factors for atrial fibrillation are known, including obesity and hypertension, but they do not fully explain all of the occurrence of atrial fibrillation.(4, 5)

Erectile dysfunction is characterized by inability to achieve or maintain penile erection for sexual intercourse. Erectile dysfunction affects approximately 40% of men aged 40 – 49 years and 70% of men aged 70 – 79 years (6) and is associated with cardiovascular diseases including coronary artery disease and stroke.(7) Erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular diseases share common risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and smoking habits.(8) One of the important mechanisms in erectile dysfunction is considered to be endothelial dysfunction, arising from atherosclerosis, which causes insufficient relaxation of the penile arteries.(9) Additionally, inflammation markers and prothrombotic markers are known to be increased among individuals with erectile dysfunction, similar to patients with atrial fibrillation.(3, 10)

Several studies reported an association between atrial fibrillation and erectile dysfunction.(11, 12) However, most of the data are derived from cross-sectional studies relating symptoms of erectile dysfunction and atrial fibrillation. Therefore, the temporal association of erectile dysfunction with incident atrial fibrillation is still unclear. Thus, this paper investigated the association of self-reported erectile dysfunction with incident atrial fibrillation using a prospective cohort study.

Methods

Study population

Details of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) have been reported previously.(13) In short, a total of 6814 participants initially free of clinical cardiovascular disease, whose ages ranged from 45 to 84 years old at first enrollment, were recruited at six field centers between July 2000 and September 2002. All participants provided informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each center. Participants have undergone multiple repeat examinations and follow-up at least yearly for hospitalized cardiovascular Disease events including atrial fibrillation. The fifth MESA examination (out of 6 total) occurred in 2010–2012.

Eligible participants of this study were male participants who underwent the assessment of erectile dysfunction at Exam 5. Erectile dysfunction was assessed based on the single Massachusetts Male Aging Study (MMAS) erectile dysfunction question.(14) Male participants who answered “don`t know” on this question were excluded from the present study. To investigate the association between erectile dysfunction and incident atrial fibrillation, participants with prior atrial fibrillation or those with atrial fibrillation diagnosed at Exam 5 were excluded from the analysis. If participants were missing baseline characteristics and erectile dysfunction follow-up data, they were also excluded from the present study (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A schematic of the decision tree with sequential steps in selection of participants.

AF indicates atrial fibrillation; ED, erectile dysfunction.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the study population were obtained from MESA Exam 5. Family history of cardiovascular disease was self-reported and collected from MESA Exam 2 (2002–2004). Family history of cardiovascular disease was defined as positive history of heart attack, cardiac procedure, and stroke among the participant’s parents, siblings, and children. Baseline characteristics included age at Exam 5, race/ethnicity (White, African American, Hispanic, and Chinese American), education level, alcohol use, and smoking status, all of which were self-reported. Education levels were categorized as some college or more or high school or less. Alcohol use was defined as present alcohol use versus not. Smoking status was evaluated by pack years. Blood samples were obtained after a 12-hour fast, and total cholesterol, plasma glucose, and creatinine were used in analysis. Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose level ≥ 126 mg/dL or any types of glucose-lowering therapy including insulin injection or oral medications at Exam 5. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was estimated using Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation.(15) Blood pressure was separately measured 3 times in the seated position after 5 minutes observation. Systolic blood pressure was defined as the average of last two measurement of systolic blood pressure. Body mass index was defined as the weight (kilograms) divided by the square of the height (meters). The usage of anti-hypertensive medications, lipid-lowering medications, beta-blockers, erectile dysfunction, and antidepressant medications was self-reported. Antidepressants included tricyclics, non-tricyclics, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors. The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D) is a depression scale designed to measure self-reported depression symptoms; a CES-D score greater than 16 was defined as depression in the present study. This scale was assessed to evaluate the relationship between erectile dysfunction and depression (psychogenic erectile dysfunction).

Definition of erectile dysfunction

In the present study, men with erectile dysfunction were defined as those who answered “sometimes able” or “never able” in accordance with the MMAS question on erectile dysfunction. On the other hand, men without erectile dysfunction were defined as those who answered “always or almost always able” or “usually able”.

Ascertainment of atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, and heart failure

Study participants underwent 12-lead ECG recordings at baseline (Exam 5). All ECG recordings automatically coded as atrial fibrillation were re-checked by a trained cardiologist to confirm the diagnosis. MESA participants or a proxy were contacted by telephone every 9 to 12 months to identify all new hospitalizations.(13, 16) Medical records were obtained, and trained staff abstracted discharge diagnostic and procedure codes from these hospitalizations. These follow-ups were performed through 2015 and the final follow-up was completed in December 2015. Incident atrial fibrillation was defined as presence of International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Ninth or Tenth Revision diagnosis codes for atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter (427.31 or 427.32; I48). We also included Medicare inpatient, outpatient, and carrier claims for participants enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare.(17) Finally, participants newly found to have atrial fibrillation by 12-lead ECG at Exam 5 (2010–2012) were classified as having atrial fibrillation as of the visit date. Atrial fibrillation that occurred during a hospitalization with open cardiac surgery was not counted as an incident atrial fibrillation event.(18)

The ascertainment of incident cardiovascular disease events has been described previously.(19) An incident cardiovascular disease event was defined as a composite of adjudicated myocardial infarction, resuscitated cardiac arrest, coronary heart disease-related death, stroke, or stroke-related death. History of myocardial infarction was defined as an incident myocardial infarction event detected prior to Exam 5. The ascertainment of incident heart failure events has been described previously.(20) History of heart failure was defined as a probable or definite heart failure event observed prior to Exam 5.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared by erectile dysfunction status. Data were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range: IQR) based on the normality of the data. Student t-test, chi-square test, and/or nonparametric tests were used for statistical analyses between two groups. A two-sided p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Follow-up time was defined as the duration between the date of Exam 5 and that of a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, death, loss of follow-up, or end of follow-up. Cumulative rate of incident atrial fibrillation by erectile dysfunction status was estimated using Kaplan-Meier curve analysis and statistical significance was evaluated by the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard models were used to calculate hazard ratios (HR) for the outcomes by erectile dysfunction status (yes/no). Unadjusted HRs and adjusted HRs by the following 3 models were assessed; Model 1 adjusted for age; Model 2 adjusted for Model 1 covariates plus race/ethnicity and education; Model 3 adjusted for Model 2 covariates plus smoking status (pack-year), BMI, diabetes, systolic blood pressure, anti-hypertensive medication use, lipid-lowering medication use, eGFR (CKD-EPI), and alcohol use. As supplemental analyses, we performed additional adjustment using history of myocardial infarction and heart failure (Model 4), both of which are included in CHARGE-AF risk model.(4) Beta blockers are known to cause drug-induced erectile dysfunction and depression can induce psychogenic erectile dysfunction. Therefore, further adjustment for beta blocker use, erectile dysfunction medication use, depression (CES-D > 16), and antidepressant use was assessed (Model 5). Variables included in the models were chosen based on prior literature, including the CHARGE-AF risk model variables.(4, 21) Diastolic blood pressure was excluded from the model since systolic and diastolic blood pressure were highly correlated (correlation coefficient, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.57 – 0.63, p < 0.01).

Age was considered as a significant confounder, and potential effect modifier for the association of erectile dysfunction and atrial fibrillation. Therefore, interaction between age and erectile dysfunction was evaluated using Cox proportional hazards models and the necessity of stratified analysis was judged by the p value for interaction. Additionally, to evaluate whether changes in the erectile dysfunction definition could affect the associations, the analysis above was repeated in sensitivity analyses using three different definitions of erectile dysfunction based on the MMAS question. In additional definition 1, men with erectile dysfunction were defined as those who answered “never able” based on MMAS question on erectile dysfunction (i.e. “severe erectile dysfunction”), and men without erectile dysfunction were defined as those who answered “always or almost always able”, “usually able”, and “sometimes able”. For additional definition 2, men with erectile dysfunction were defined as those who answered “sometimes able”, and men without erectile dysfunction were defined as those who answered “usually able” and “always or almost always able”. In the second definition, men with “never able” were excluded from the analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP version 14.

Results

A total of 1,760 participants were followed for a median of 3.8 (IQR, 3.5 – 4.2) years (Figure 1). During the follow-up period, 94 cases of incident atrial fibrillation were observed.

Baseline characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. Erectile dysfunction was observed in 777 (44.1%) of 1760 participants. Overall, the mean age was 68 ± 9 years. Family history of cardiovascular disease was found in 68% of the participants. The percentage of participants with CES-D > 16 was 11.1% and that of participants taking erectile dysfunction medication was 2.3%. There were statistically significant differences between men with and without erectile dysfunction in age, education level, blood pressure, smoking status, current alcohol use, history of diabetes, history of heart failure, family history of cardiovascular disease, total cholesterol, eGFR, anti-hypertensive and lipid-lowering medication use, beta blocker medication use, CES-D > 16, and antidepressant use. Erectile dysfunction medication use was uncommon in both groups (3.1% in erectile dysfunction positive group, and 1.7% in the erectile dysfunction negative group, p=0.06).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population by the presence of erectile dysfunction

| Overall, n = 1760 | ED (+), n = 777 | ED (−), n = 983 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year | 68 ± 9 | 73 ± 9 | 65 ± 8 | < 0.01 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White, n (%) | 734 (41.7) | 328 (42.2) | 406 (41.3) | 0.76 |

| African American, n (%) | 427 (10.9) | 188 (24.2) | 239 (24.3) | |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 407 (23.1) | 183 (23.6) | 224 (22.8) | |

| Chinese American, n (%) | 192 (10.9) | 78 (10.0) | 114 (11.6) | |

| Higher education, n (%) | 1295/1756 (73.7) | 531/776 (68.4) | 764/980 (78.0) | < 0.01 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.3 ± 4.7 | 28.4 ± 4.8 | 28.1 ± 4.5 | 0.17 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 122 ± 19 | 125 ± 21 | 120 ± 17 | < 0.01 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 71 ± 10 | 70 ± 10 | 73 ± 9 | < 0.01 |

| Smoking, pack-years | 2 (0 –19) | 4 (0 – 24) | 1 (0 – 16) | < 0.01 |

| Current alcohol use, n (%) | 930 (52.8) | 375 (48.3) | 555 (56.5) | < 0.01 |

| History of diabetes, n (%) | 359/1742 (20.6) | 221/765 (27,6) | 148/977 (15.2) | < 0.01 |

| History of heart failure, n (%) | 27 (1.5) | 18 (2.3) | 9 (0.9) | 0.02 |

| History of MI, n (%) | 37 (2.1) | 21 (2.7) | 16 (1.6) | 0.12 |

| Family history of CVD, n (%) | 1194/1757 (68.0) | 560/776 (72.2) | 634/981 (64.6) | < 0.01 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 173 ± 35 | 168± 34 | 177 ± 35 | < 0.01 |

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 80 ± 17 | 75 ± 18 | 84 ± 15 | < 0.01 |

| Anti-hypertensive medication use, n (%) | 910 (51.7) | 497 (64.0) | 413 (42.0) | < 0.01 |

| Lipid-lowering medication use, n (%) | 702 (39.9) | 367 (47.2) | 335 (34.1) | < 0.01 |

| Beta blocker medication use, n (%) | 271 (15.4) | 160 (20.6) | 111 (11.3) | < 0.01 |

| CES-D > 16, n (%) | 194/1743 (11.1) | 101/763 (13.2) | 93/980 (9.5) | 0.01 |

| Antidepressant use, n (%) | 127/1757 (7.2) | 73/776 (9.4) | 54/981 (5.5) | < 0.01 |

| ED medication use, n (%) | 41 (2.3) | 24 (3.1) | 17 (1.7) | 0.06 |

Abbreviation: CES-D indicates Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression; CVD, cardiovascular disease; ED, erectile dysfunction; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MESA, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; MI, myocardial infarction.

Continuous variables are summarized as mean ± SD and median (interquartile range).

Categorical variables are summarized as n (%). Student t test, Wilcoxon test, x2 square test (Pearson) are used for statistical analysis. A p value less than 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Figure 2 shows the proportion of erectile dysfunction responses and the number with incident atrial fibrillation in each age group. The proportion of participants with erectile dysfunction increased with age; 23.1%, in the group aged 54–64 years; 46.2%, 65–74 years; 69.8%, 75–84 years; 80.2%, ≥ 85 years.

Figure 2. The distribution of erectile dysfunction and incidence of atrial fibrillation in each age category.

Erectile dysfunction was defined as the combination of “Never” (light blue) with “Sometimes” (dark blue). The prevalence of erectile dysfunction increased as higher age groups, from 23.1% in the subgroup between 54 and 64 years to 80.2% in the subgroup > 85 years. The same trend was observed in the incidence rate of atrial fibrillation in each age group (below the bar chart). AF indicates atrial fibrillation; MMAS, Massachusetts Male Aging Study.

Cumulative incidence of atrial fibrillation was estimated using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (Figure 3). The 4-year atrial fibrillation incidence was significantly higher (p < 0.01) in the erectile dysfunction positive group than in the erectile dysfunction negative group (9.6 vs 2.9%, respectively).

Figure 3. The difference of atrial fibrillation-free survival by the presence or absence of erectile dysfunction.

During the median follow-up of 3.8 years, there was a significant distinction between two groups by log-rank test (p < 0.01). A 4-year incident AF rate was 9.6% (ED+) vs 2.9% (ED-), respectively. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; ED, erectile dysfunction.

In the unadjusted Cox proportional hazards analysis, the presence of erectile dysfunction was significantly associated with incident atrial fibrillation (Table 2). Adjusting for Model 1 covariates, the association between erectile dysfunction and atrial fibrillation was attenuated, and slight additional attenuation of the association was observed in Model 2. In the fully adjusted model (Model 3), erectile dysfunction was still significantly associated with incident atrial fibrillation (HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.01 – 2.72; p value = 0.044). Additional adjustment for history of myocardial infarction and heart failure did not attenuate the association between erectile dysfunction and atrial fibrillation.

Table 2.

The association of prevalent erectile dysfunction on incident atrial fibrillation risk

| Hazard ratio | 95% Lower CI | 95% Upper CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | 3.20 | 2.05 | 4.97 | < 0.01 |

| Model 1 | 1.87 | 1.16 | 3.02 | 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 1.83 | 1.13 | 2.97 | 0.01 |

| Model 3 | 1.66 | 1.01 | 2.72 | 0.044 |

Abbreviation: BMI indicates body mass index; CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Model 1 is adjusted for age.

Model 2 is adjusted for Model 1 covariates plus race/ethnicity and education level.

Model 3 is adjusted for Model 1 covariates plus smoking (pack-years), current alcohol use, BMI, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, total cholesterol, eGFR (CKD-EPI), anti-hypertensive medication use, and lipid-lowering medication use.

In contrast, additional adjustment for beta blocker use, erectile dysfunction drug, depression (CES > 16), and antidepressant use did not attenuate the association between erectile dysfunction and atrial fibrillation (Supplemental Table 1). A p value for interaction between age and erectile dysfunction was computed across the same models in Table 2 and the p value was not significant across all models. Therefore, stratified analysis by age was not performed.

As a sensitivity analysis, we investigated the effect of different definitions of erectile dysfunction on incident atrial fibrillation (Supplemental Table 2). In the additional definition 1 (“severe erectile dysfunction”), statistical significance was only observed in the unadjusted model. In contrast, statistical significance was retained across all models in the additional definition 2. Across all definitions, the HR was considerably attenuated when adjusting for age (i.e. Model 1).

Finally, to evaluate the effect of history of myocardial infarction and heart failure on the association between erectile dysfunction and incident atrial fibrillation, we repeated the same analysis above after excluding participants with a history of myocardial infarction or heart failure. Statistical significance was observed in the unadjusted model, Model 1, and Model 2, but not in Model 3 (Supplemental Table 3), although HRs were similar to the main analysis.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that erectile dysfunction is significantly associated with incident atrial fibrillation after adjusting for several conventional risk factors for atrial fibrillation. Previous investigations of the association between atrial fibrillation and erectile dysfunction were conducted in cross-sectional studies or evaluated the incidence of erectile dysfunction in patients with atrial fibrillation.(11, 12, 22) To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the temporal association between erectile dysfunction and incident atrial fibrillation using a prospective cohort study in the US.

Vascular erectile dysfunction and atrial fibrillation share many risk factors such as age, hypertension, diabetes, obesity and renal impairment. In a previous study, higher levels of subclinical atherosclerosis measures, defined by coronary artery calcium score, carotid artery thickness, and ankle brachial index, were associated with a higher prevalence of erectile dysfunction 9 years later.(23) Additionally, erectile dysfunction symptoms are reportedly overt 2–3 years prior to cardiovascular disease symptoms.(24) These results suggest that vascular erectile dysfunction occurs as a result of accumulation of systemic atherosclerotic changes and can serve as an early warning sign before cardiovascular disease becomes clinically manifest and therefore can present an opportunity to initiate preventive therapy strategies.

Several pathophysiologic pathways are reportedly associated with erectile dysfunction progression other than atherosclerotic factors such as endocrine disorders including hypogonadism. Hypogonadism relating to testosterone-deficiency is especially noteworthy, as it may also explain the increased incidence of atrial fibrillation in individuals with erectile dysfunction. Tsuneda et al. reported in their rat experimental models that deficiency of testosterone caused arrhythmogenicity in the left atria.(25) These findings were replicated in at least two other prospective cohorts, the Framingham Heart Study and the FINRISK study.(26, 27) In contrast, a recent report found that testosterone level was positively associated with incident atrial fibrillation in men in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study.(28) Given the conflicting results, the role of testosterone in atrial fibrillation pathophysiology is still unclear.

Age is considered the most important factor in erectile dysfunction progression.(29, 30) This was confirmed in the present study since the association between erectile dysfunction and atrial fibrillation was attenuated most significantly when adjusting for age. The number of participants complaining of erectile dysfunction symptoms increased with age and this observation was in parallel with the increase of incidence of atrial fibrillation (per year). However, the multiplicative interaction between age and erectile dysfunction was not statistically significant in the present study and erectile dysfunction symptoms are considered to be associated with incident atrial fibrillation homogeneously across any age groups.

The strengths of the present study include the use of a prospective cohort design with standardized measurement of all baseline factors including erectile dysfunction. Follow-up of incident atrial fibrillation was periodically performed which resulted in few missing data, and the definition of incident atrial fibrillation was universal across the different six clinical sites. Additionally, erectile dysfunction was assessed before incident atrial fibrillation events, which enabled us to evaluate the temporal association between erectile dysfunction and incident atrial fibrillation. The present study also includes several limitations. First, erectile dysfunction was diagnosed based on self-reported questionnaire and precise causes were not identified. Erectile dysfunction can be classified into two major categories, vascular erectile dysfunction and non-vascular erectile dysfunction. Non-vascular erectile dysfunction, especially psychogenic erectile dysfunction, is more frequently observed in younger men and is associated with the prevalence of psychogenic erectile dysfunction. However, we were not able to discern vascular vs non-vascular erectile dysfunction based on the MMAS survey question. Second, MESA is a multiethnic prospective cohort study conducted in six different cities throughout the US. However, White race/ethnicity represents the largest group of MESA participants. Therefore, we were unable to examine interactions by race/ethnicity for these associations. Finally, we undoubtedly failed to ascertain some cases of atrial fibrillation because some participants have asymptomatic atrial fibrillation, which prevented them from clinical recognition. Furthermore, we were not able to distinguish paroxysmal from persistent or permanent atrial fibrillation in the present study.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that erectile dysfunction was an independent predictor for incident atrial fibrillation using the prospective cohort data. History taking in terms of erectile dysfunction may provide a useful adjunct to risk assessment for atrial fibrillation.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Significance.

The proportion of participants with erectile dysfunction and incident atrial fibrillation increased with age.

Cumulative rate of incident atrial fibrillation was higher in study participants with erectile dysfunction than those without erectile dysfunction. Erectile dysfunction was independently associated with incident atrial fibrillation after adjusting for conventional risk factors for atrial fibrillation.

History of erectile dysfunction symptoms may provide a useful adjunct to risk assessment for atrial fibrillation.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciated the other investigators, the staffs, and the participants of MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) for their precious contribution.

Funding sources

The MESA cohort study is funded by contracts HHSN268201500003I, N01-HC-95159, N01-HC-95160, N01-HC-95161, N01-HC-95162, N01-HC-95163, N01-HC-95164, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168 and N01-HC-95169 and by grant HL127659 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and by grants UL1-TR-000040, UL1-TR-001079, and UL1-TR-001420 from NCATS. Dr. Tanaka was supported by American Heart Association Strategically Focused Research Network (SFRN), 18SFRN34110170. Dr. Bundy was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Cardiovascular Epidemiology training grant T32HL069771.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Santhanakrishnan R, Wang N, Larson MG, Magnani JW, McManus DD, Lubitz SA, et al. Atrial Fibrillation Begets Heart Failure and Vice Versa: Temporal Associations and Differences in Preserved Versus Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circulation. 2016;133(5):484–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krishnamoorthy S, Lim SH, Lip GY. Assessment of endothelial (dys)function in atrial fibrillation. Ann Med. 2009;41(8):576–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo Y, Lip GY, Apostolakis S. Inflammation in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(22):2263–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alonso A, Krijthe BP, Aspelund T, Stepas KA, Pencina MJ, Moser CB, et al. Simple risk model predicts incidence of atrial fibrillation in a racially and geographically diverse population: the CHARGE-AF consortium. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(2):e000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schnabel RB, Sullivan LM, Levy D, Pencina MJ, Massaro JM, D’Agostino RB, et al. Development of a risk score for atrial fibrillation (Framingham Heart Study): a community-based cohort study. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):739–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, McKinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 1994;151(1):54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raheem OA, Su JJ, Wilson JR, Hsieh TC. The Association of Erectile Dysfunction and Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Critical Review. Am J Mens Health. 2017;11(3):552–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson G, Boon N, Eardley I, Kirby M, Dean J, Hackett G, et al. Erectile dysfunction and coronary artery disease prediction: evidence-based guidance and consensus. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(7):848–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu T, Meng XY, Li T, Fu ZL, Zhao SG, Yao HC. Atherosclerosis is critical in the pathogenesis of erectile dysfunction. Int J Cardiol. 2016;203:367–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Ioakeimidis N, Rokkas K, Vasiliadou C, Alexopoulos N, et al. Unfavourable endothelial and inflammatory state in erectile dysfunction patients with or without coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(22):2640–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yılmaz S, Kuyumcu MS, Akboga MK, Sen F, Balcı KG, Balcı MM, et al. The relationship between erectile dysfunction and paroxysmal lone atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2016;46(3):245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Platek AE, Hrynkiewicz-Szymanska A, Kotkowski M, Szymanski FM, Syska-Suminska J, Puchalski B, et al. Prevalence of Erectile Dysfunction in Atrial Fibrillation Patients: A Cross-Sectional, Epidemiological Study. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2016;39(1):28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, et al. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(9):871–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleinman KP, Feldman HA, Johannes CB, Derby CA, McKinlay JB. A new surrogate variable for erectile dysfunction status in the Massachusetts male aging study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(1):71–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawut SM, Barr RG, Lima JA, Praestgaard A, Johnson WC, Chahal H, et al. Right ventricular structure is associated with the risk of heart failure and cardiovascular death: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA)--right ventricle study. Circulation. 2012;126(14):1681–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chrispin J, Jain A, Soliman EZ, Guallar E, Alonso A, Heckbert SR, et al. Association of electrocardiographic and imaging surrogates of left ventricular hypertrophy with incident atrial fibrillation: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(19):2007–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heckbert SR, Wiggins KL, Blackshear C, Yang Y, Ding J, Liu J, et al. Pericardial fat volume and incident atrial fibrillation in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and Jackson Heart Study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(6):1115–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beinart R, Zhang Y, Lima JA, Bluemke DA, Soliman EZ, Heckbert SR, et al. The QT interval is associated with incident cardiovascular events: the MESA study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(20):2111–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Neal WT, Mazur M, Bertoni AG, Bluemke DA, Al-Mallah MH, Lima JAC, et al. Electrocardiographic Predictors of Heart Failure With Reduced Versus Preserved Ejection Fraction: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uddin SMI, Mirbolouk M, Dardari Z, Feldman DI, Cainzos-Achirica M, DeFilippis AP, et al. Erectile Dysfunction as an Independent Predictor of Future Cardiovascular Events. Circulation. 2018;138(5):540–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin WY, Lin CS, Lin CL, Cheng SM, Lin WS, Kao CH. Atrial fibrillation is associated with increased risk of erectile dysfunction: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2015;190:106–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feldman DI, Cainzos-Achirica M, Billups KL, DeFilippis AP, Chitaley K, Greenland P, et al. Subclinical Vascular Disease and Subsequent Erectile Dysfunction: The Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Clin Cardiol. 2016;39(5):291–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gowani Z, Uddin SMI, Mirbolouk M, Ayyaz D, Billups KL, Miner M, et al. Vascular Erectile Dysfunction and Subclinical Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2017;9(4):305–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsuneda T, Yamashita T, Kato T, Sekiguchi A, Sagara K, Sawada H, et al. Deficiency of testosterone associates with the substrate of atrial fibrillation in the rat model. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20(9):1055–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magnani JW, Moser CB, Murabito JM, Sullivan LM, Wang N, Ellinor PT, et al. Association of sex hormones, aging, and atrial fibrillation in men: the Framingham Heart Study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7(2):307–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeller T, Schnabel RB, Appelbaum S, Ojeda F, Berisha F, Schulte-Steinberg B, et al. Low testosterone levels are predictive for incident atrial fibrillation and ischaemic stroke in men, but protective in women - results from the FINRISK study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25(11):1133–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berger D, Folsom AR, Schreiner PJ, Chen LY, Michos ED, O’Neal WT, et al. Plasma total testosterone and risk of incident atrial fibrillation: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Maturitas. 2019;125:5–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiri R, Koskimäki J, Hakama M, Häkkinen J, Tammela TL, Huhtala H, et al. Prevalence and severity of erectile dysfunction in 50 to 75-year-old Finnish men. J Urol. 2003;170(6 Pt 1):2342–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selvin E, Burnett AL, Platz EA. Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in the US. Am J Med. 2007;120(2):151–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.