Abstract

Objective

Suicide remains a leading cause of death in the United States and recent reports have suggested the suicide rate is increasing. One of the most robust predictors of future suicidal behavior is a history of attempting suicide. Despite this, little is known about the factors that reduce the likelihood of a re-attempting suicide. This study compares theoretically-derived suicide risk indicators to determine which factors are most predictive of future suicide attempts

Method

We used data from a randomized controlled trial comparing three forms of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT; Linehan et al., 2015). Participants (N = 99, mean age = 30.3 years, 100% female, 71% White) met criteria for borderline personality disorder and had repeated and recent self-injurious behavior. Assessments occurred at four-month intervals throughout one year of treatment and one year of follow-up. Time-lagged generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) were used to evaluate relationship satisfaction, emotion dysregulation, and coping styles as predictors of suicide attempts.

Results

Both univariate and multivariate models suggested that higher between person variance in problem-focused coping and lack of access to emotion regulation strategies were weakly associated with additional suicide attempts over the two-year study. Within person variance in the time-lagged predictors were not associated with subsequent suicide attempts.

Conclusions

Among individuals with a recent suicide attempt, problem-focused coping and specific deficits in emotion regulation may differentiate those likely to re-attempt from those who stop suicidal behavior during and after psychotherapy. These results suggest that treatments for recent suicide attempters should target increasing problem-focused coping and decreasing maladaptive emotion regulation skills.

Public Health Significance

Suicide is a complex public health problem and researchers are unable to reliably predict when suicide attempts are likely to occur. Results from this study suggest that some of the risk factors studied to date explain differences between people who continue to be at high-risk for suicide, but individual deviations in these risk factors do not prospectively predict suicide attempts.

Keywords: Dialectical Behavior Therapy, Multi-level models, Suicide attempts, Borderline Personality Disorder

There were 47,173 deaths due to suicide in 2017, making suicide the 10th leading cause of death in the United States (Murphy, Xu, Kochanek, & Arias, 2018). Between the years 1999 and 2017, the rate of suicide has increased 33% from 10.5/100,000 deaths in 1999 to 14.0/100,000 in 2017 (Hedegaard, Curtin, & Warner, 2018). One of the most robust predictors of future suicidal behavior is a prior suicide attempt (Beghi, Rosenbaum, Cerri, & Cornaggia, 2013; Olfson et al., 2017; see O’Connor & Nock, 2014 for a comprehensive review). Indeed, individuals who have made a previous suicide attempt are up to 70 times more likely to attempt suicide (Sanchez-Gistau et al., 2013) and up to 40 times more likely to die by suicide (Harris & Barraclough, 1997) than people who have not attempted suicide.

A systematic review of risk factors for repeated suicide attempts found that a history of childhood sexual abuse, poor global functioning, presence of a psychiatric disorder (specifically depression, anxiety, and alcohol use disorders), and involvement with psychiatric treatment are associated with a higher likelihood of re-attempting suicide (Beghi et al., 2013). These studies provide useful information about between person differences that generally place one person at higher risk of re-attempting than another. However, from a treatment perspective, it is not only important to know which suicidal individuals are at higher risk of re-attempting than others, but also which time-varying factors need to change for a specific person to be less at risk of re-attempting in the future. This within person information could help clinicians to more precisely capitalize on important change targets, thereby leading to more efficient and effective treatments.

There is a relative paucity of RCTs that evaluate suicide attempts as an outcome (Miller et al., 2017). Of the studies that have focused on reducing suicide attempts, even fewer have examined factors that may explain the mechanisms that account for reductions in suicide attempts during treatment. Given the dearth of prior research in this area, the within and between person factors examined as predictors of suicide attempts in the present study were drawn from the empirical literature when available as well as leading theories of suicide.

Interpersonal factors have long been known to be associated with increased suicide risk (see King & Merchant, 2008 for a review), including increased risk for suicide attempts (You, Van Orden, & Conner, 2011). Leading theories of suicide implicate loneliness and lack of belongingness as important factors leading to death by suicide (e.g., Durkheim, 2005; Joiner, 2005). Despite the evidence for interpersonal factors contributing to the development of suicidal behaviors, only one study to our knowledge has investigated interpersonal factors, including perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, as a mediator of reduced risk for suicide attempts during psychotherapy (Bryan et al., 2018). This study did not find evidence for interpersonal factors as a mediator of suicide attempts within the context of brief cognitive behavioral therapy. However, this result requires replication given the otherwise strong evidence for the role of interpersonal factors in predicting suicide risk.

Difficulty with emotion regulation, or the ability to modify emotional responses to engage in goal-directed behavior (Gross, 2002), is a transdiagnostic risk factor for psychopathology as well as suicidal behavior (Neacsiu, Fang, Rodriguez, & Rosenthal, 2018). Individuals with a history of multiple suicide attempts have been shown to differ from those without a history of suicide attempts in their ability to access effective emotion regulation strategies (Rajappa, Gallagher, & Miranda, 2011). Additionally, an increase in more adaptive emotion regulation skills are theoretically hypothesized to account for the positive treatment effects in Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT; Lynch, Chapman, Rosenthal, Kuo, & Linehan, 2006). However, there are no studies that have examined how changes in emotion regulation strategies are associated with risk for re-attempting suicide within a psychotherapy treatment study.

Additionally, individuals with a history of attempting suicide engage in more passive, avoidant styles of coping as opposed to more direct, problem-focused coping methods (Pollack & Williams, 2004). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors have been conceptualized as an avoidant coping behavior given that they often function as way to escape from aversive negative emotions and other stressors (Chapman, Gratz, & Brown, 2006; Millner et al., 2019). To our knowledge only one study has examined coping strategies as a mediator of treatment response within a suicidal population and found that increases in DBT skills use, a form of problem-focused coping, explained the positive effects of DBT on suicide attempts (Neacsiu, Rizvi, & Linehan, 2010). This result requires replication as well as extension to consider the potential differential impact of within- and between-person changes in styles of coping on subsequent suicide attempts during treatment.

The present study aims to disentangle the between and within person differences in these hypothesized change targets in prospectively predicting the likelihood that an individual with a past year suicide attempt will engage in a repeat attempt during or after treatment. Data are drawn from a two-year RCT and component analysis of DBT (Linehan et al., 2015). A recent meta-analysis of 18 clinical trials found that DBT is effective in reducing deliberate self-harm (i.e., suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury) with an estimated effect size of −0.32 (Decou, Comtois, & Landes, 2018). The present study adds to this literature by investigating modifiable factors that may account for the well-established efficacy of DBT in reducing suicide attempts. We hypothesized that (H1) within-person increases in relationship satisfaction, emotion regulation skills, and problem-focused coping, as well as decreases in avoidant coping, would be associated with a decreased likelihood of a subsequent suicide attempt. We also hypothesized that (H2) between-person differences in relationship satisfaction, emotion regulation skills, avoidant coping and problem-focused coping would differentiate between those who did versus did not re-attempt suicide during and after treatment.

Method

Study Design

This study used data from a 3-arm, single blind RCT and dismantling study of DBT that was designed to evaluate the effect of the skills training component of DBT (Linehan et al., 2015). An adaptive randomization procedure matched participants on age, number of suicide attempts, number of NSSI episodes, psychiatric hospitalizations in the past year, and depression severity. Assessments were conducted by blinded independent evaluators at pre-treatment and quarterly over one year of treatment and one year of follow-up. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review board and the full study protocol can be found in (Linehan et al., 2015) and will be briefly reviewed here.

Participants

Participants were 97 women aged 18 to 60 years who met criteria for borderline personality disorder (BPD) on both the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Axis II (SCID-II; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Benjamin, & Williams, 1997) and the Personality Disorder Examination (PDE; Loranger, 1988). Additionally, participants were required to have engaged in at least two episodes of intentional self-injurious behavior (suicide attempts and/or NSSI) in the last 5 years, at least one episode in the 8-week period before entering the study and at least one suicide attempt in the past year.1

Participants were excluded if they had an IQ less than 70 on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test - Revised (PPVT-R; Dunn & Dunn, 1981), met criteria for current psychotic or bipolar disorders on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Axis I (SCID-I; First et al., 1997), had a seizure disorder requiring medication, or required primary treatment for another life-threatening condition. Participants were recruited via outreach efforts to health care providers in the local Seattle area.

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to condition using a minimization randomization procedure that successfully matched on five potential prognostic variables: age, number of suicide attempts, number of non-suicidal self-injury episodes, psychiatric hospitalizations in the past year, and depression severity. Assessments were conducted by independent evaluators who were blind to treatment condition at pre-treatment and every four months over the course of the 12-month treatment year and 12-month follow-up for seven assessment periods. Across all assessment points, an average of 80.14% of participants were retained (range = 73.74% to 100%).

Treatments

The three treatment arms were: (1) Standard DBT (S-DBT; n=33) that was delivered according to the treatment manual (Linehan, 1993) and included individual therapy, group skills training, therapist consultation team, and between-session phone coaching, (2) DBT Individual therapy (DBT-I; n=33) that included individual therapy without any teaching of DBT skills and an activity-based support group, and (3) DBT Skills (DBT-S; n=33) that included group skills training and individual manualized case management. In the parent study, no differences were observed between the three conditions on the probability of attempting suicide during treatment or follow-up (Linehan et al., 2015). Thus, we collapsed across all treatment conditions for the current secondary analyses.

Measures

Relationship satisfaction

The Social History Interview (SHI) measures psychosocial functioning and was adapted from the Social Adjustment Scale-Self Report (SAS-SR; Weissman & Bothwell, 1976) and the Longitudinal Interview Follow-up Evaluation Base-Schedule (LIFE; Keller et al., 1987). Two items within the SHI were used to assess the quality of the family (one item) and peer relationships (one item) for the worst week in the past month. Respondents rated how satisfied they were with both their family and peer situations for the worst week in the past month on a Likert-style item ranging from 1 (poor) to 5 (great). The two items were averaged for analysis.

Emotion regulation

Emotion regulation was assessed using the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004). The DERS is a 36-item self-report scale that measures participant perceived problems in multiple domains of effective emotion regulation. The DERS demonstrated high internal consistency in this sample (Cronbach’s α = .97), and adequate construct and predictive validity in other samples (Gratz & Roemer, 2004).

As emotion regulation and coping are overlapping constructs (Compas et al., 2017), and due to the fact that the DERS measures emotion regulation in a multidimensional and hierarchical fashion (see Smith, McCarthy, and Zapolski (2009) for an overview on limitations of analyzing these kinds of measures), we chose to analyze both the DERS total score and the individual DERS subscales to examine relations of specific deficits in emotion regulation with prospective suicide attempts. These subscale models should be considered exploratory, because we did not initially hypothesize differences among the subscales of the DERS.

There are six subscales of the DERS, which include nonacceptance of emotions (sample α = .93), difficulty engage in goal-directed behaviors (α = .89), impulse control difficulties (α = .91), lack of emotional awareness (α = .89), limited access to emotion regulation strategies (α = .92), and lack of emotional clarity (α = .88). Higher scores on the DERS indicates more problematic emotion regulation.

Coping strategies

We measured avoidant and problem focused coping with two subscales of the 42-item Revised Ways of Coping Checklist (RWCCL; Vitaliano, Russo, Carr, Maiuro, & Becker, 1985). The problem-focused coping subscale (15-items, α = .89) assessed active coping strategies (e.g., “[I] came up with a couple different solutions to the problem” and “[I] made a plan of action and followed it”). The avoidance subscale (10-items, α = .88) assessed avoidant coping strategies (e.g.,”[I] tried to forget the whole thing”). Items were rated on a Likert scale from 0 (“Never used”) to 3 (“Regularly used”) and averaged to create subscales. Higher scores on the problem-focused coping and avoidant coping subscales indicate more reliance on these two forms of coping.

Suicide attempts

The Suicide Attempt and Self-Injury Interview (SASII; Linehan, Comtois, Brown, Heard, & Wagner, 2006) is a structured clinical interview that assesses the frequency, intent, and medical severity of suicide attempts and NSSI acts. For the present analyses, a binary variable was computed to indicate the presence or absence of a suicide attempt (SA) during each 4-month assessment period (0 = no SA,1 = 1 or more SA). The SASII defines SAs as any type of intentional self-injury in which the person reported at least some intent to die as a result of the behavior.

Analytic Strategy

All analyses were conducted using the intent-to-treat sample (n = 97). We used generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs; McCulloch & Neuhaus, 2001) a form of generalized liner regression models (GLMs) and hierarchical linear modeling (HLM; Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992). GLMMs allow for the analysis of non-independent (e.g., repeated measures) longitudinal data and for models with non-normal outcomes (e.g., continuous, categorical, binary, and count data; Stoup, 2012). GLMMs also allow for the modeling of data within a nesting structure (within person effects) while also modeling effects across different levels of that nesting structure (between person effects). Treatment condition did not moderate any predictor effects. Based on these results, we removed treatment condition from the final time-lagged models for parsimony. For this study, all models were tested in R (R Core Team, 2013) using the lme4 package.

To test our hypotheses, we analyzed univariate GLMM models with each of the hypothesized predictor variables to determine whether any of our hypothesized time-lagged variables predicted subsequent suicide attempts. The following formula was used for each of the predictors to determine the relation between the centered predictor and the probability an individual attempts suicide by the following assessment point:

All predictor variables were both centered-within person and grand-mean-centered. Centering within person is calculated by subtracting the participant-level mean across observations from each participants’ score at each time point. Participants’ observation at each time point are therefore a deviation score, representing the individual’s departure from their own average at that time point. Grand mean centering is conducted by subtracting the grand mean of the sample from the participant-level mean. Grand mean centering thus reflects the individual’s average score on each predictor across all observations, representing divergence from the sample average (Enders & Tofighi, 2007). Centering in such a manner disaggregates the within- and between-person effects so that they were completely uncorrelated (r = 0.00). Approximately 20% of all data was missing; GLMMs are robust to missing data (Liu & Zhan, 2011) and all available Level 1 data were included. GLMM does use listwise deletion for Level 2 data, but, as all participants had baseline data, no Level 2 data were excluded. The parent study found no evidence to suggest that suicide attempts were biased by missing data (Linehan et al., 2015). Based on power of .80, alpha = .05, with 7 observations from 97 people, and an ICC of .48 (the average ICC from all models), the current sample could detect effects as small as f2 = .21, a medium effect size.

We tested initial models for the main outcome (SAs) from an unconditional growth model using deviance testing to compare linear and quadratic time models (Verbeke, 1997). We used - 2 * log likelihood, Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), and Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) to determine the best fitting model. Results indicated that a model in which time was included as a linear and quadratic fixed effect fit the data best. Models with a random effect of time did not converge using lme4, we confirmed that a random time slope did not improve model fit with Bayesian models using the rstanarm package (Gabry & Goodrich, 2018).

Hypothesis testing

To test our hypotheses, we first tested univariate GLMM models, one model for each of the predictor variables. We used the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (Benjamini Hochberg, 1995) to adjust alpha for false discovery, which allowed us to control for false positives on both levels of the GLMM. To calculate the adjusted alpha, the rate of false discovery rate was set at 5%. Finally, we simulated data to calculate the predicted probability of suicide attempts over the two year follow-up for each level (+/− 2 SD) of the significant associations.

Results

Descriptives

Descriptive data on suicide attempts is presented in Table 1. The probability of attempting suicide varied across assessment points (follow-up range = 6.58% - 23.53%). Approximately 30% of participants reported at least one SA over the two-year period. The average participant reported at least one SA at 33% of the assessment points (~2 suicide attempts per participant). Of those reporting a suicide attempt after baseline, the mean lethality of the most severe self-injurious act was 7.79/23 (range = 0 – 19). Across all self-injurious acts, participants with a suicide attempt had a mean lethality of 4.34/23 (range = 0 – 18). Table 2 presents descriptive data for all predictors and covariates.

Table 1.

Proportion of sample attempting suicide at each time point

| Any Suicide Attempts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | |

| Pre-treatmenta | 97 (100.00%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| 4-month | 20 (20.62%) | 64 (65.98%) |

| 8-month | 11 (11.34%) | 63 (64.95%) |

| 12-month | 9 (9.28%) | 65 (67.01%) |

| 16-month | 5 (5.15%) | 70 (72.16%) |

| 20-month | 5 (5.15%) | 67 (69.07%) |

| 24-month | 5 (5.15%) | 67 (69.07%) |

Includes suicide attempts over the past year

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for predictors and covariates by assessment point and condition

| Relationship Satisfaction | Emotion Regulation | |||||||||||

| S-DBT | DBT-I | DBT-S | S-DBT | DBT-I | DBT-S | |||||||

| Assessment Point | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Pre-treatment | 2.00 | 0.84 | 1.87 | 0.91 | 2.24 | 1.21 | 126.13 | 22.04 | 128.97 | 18.89 | 125.91 | 23.17 |

| 4-month | 2.04 | 0.98 | 1.83 | 0.82 | 2.14 | 0.98 | 104.97 | 23.47 | 119.25 | 25.01 | 97.63 | 24.45 |

| 8-month | 2.08 | 1.18 | 1.94 | 0.91 | 2.39 | 1.67 | 100.04 | 24.47 | 114.22 | 24.80 | 94.43 | 27.64 |

| 12-month | 2.12 | 0.98 | 2.11 | 1.02 | 2.07 | 0.95 | 86.96 | 25.69 | 97.24 | 25.75 | 86.09 | 24.84 |

| 16-month | 1.87 | 0.93 | 2.12 | 0.88 | 2.29 | 1.32 | 90.21 | 30.65 | 97.47 | 27.81 | 88.06 | 29.12 |

| 20-month | 1.90 | 0.94 | 1.64 | 0.90 | 2.26 | 1.01 | 89.21 | 29.01 | 91.57 | 24.72 | 87.11 | 26.90 |

| 24-month | 1.82 | 0.99 | 1.38 | 0.68 | 1.83 | 0.93 | 88.88 | 29.52 | 93.05 | 30.61 | 80.46 | 22.98 |

| Problem-Focused Coping | Avoidant Coping | |||||||||||

| S-DBT | DBT-I | DBT-S | S-DBT | DBT-I | DBT-S | |||||||

| Assessment Point | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Pre-treatment | 1.42 | 0.57 | 1.33 | 0.53 | 2.18 | 0.53 | 2.18 | 0.53 | 2.16 | 0.45 | 2.09 | 0.52 |

| 4-month | 1.96 | 0.50 | 1.64 | 0.54 | 2.00 | 0.53 | 1.82 | 0.64 | 2.04 | 0.47 | 1.61 | 0.60 |

| 8-month | 2.02 | 0.43 | 1.77 | 0.62 | 2.00 | 0.64 | 1.76 | 0.56 | 1.92 | 0.51 | 1.62 | 0.53 |

| 12-month | 2.16 | 0.41 | 1.93 | 0.51 | 2.06 | 0.52 | 1.56 | 0.71 | 1.72 | 0.64 | 1.42 | 0.68 |

| 16-month | 2.06 | 0.48 | 1.91 | 0.54 | 1.83 | 0.83 | 1.62 | 0.64 | 1.58 | 0.54 | 1.53 | 0.66 |

| 20-month | 2.02 | 0.56 | 1.91 | 0.71 | 2.07 | 0.61 | 1.56 | 0.78 | 1.44 | 0.64 | 1.59 | 0.70 |

| 24-month | 2.05 | 0.49 | 1.91 | 0.62 | 2.10 | 0.56 | 1.57 | 0.59 | 1.48 | 0.55 | 1.48 | 0.56 |

Identifying covariates

Baseline factors

Diagnoses (major depressive disorder, substance use disorder, any anxiety disorder), age, and the number of prior suicide attempts did not predict the proportion of assessments with suicide attempts during or after treatment. Given these results, multivariate models did not control for baseline clinical or demographic information. Results from univariate models are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Univariate binomial GLMM models predicting time lagged suicide attempts

| SA Predicted by Relationship Satisfaction | SA Predicted by Emotion Dysregulation | |||||||

| b | OR | 95% CI (OR) | p-value | b | OR | 95% CI (OR) | p-value | |

| Intercept | −2.32 | 0.10 | 0.04 – 0.18 | <.001* | −2.43 | 0.09 | 0.04 – 0.17 | <.001* |

| Between Effects | ||||||||

| Linear growth | −1.60 | 0.20 | 0.14 – 0.28 | <.001* | −1.54 | 0.21 | 0.14 – 0.30 | <.001* |

| Quadratic growth | 0.49 | 1.63 | 1.39 – 1.92 | <.001* | 0.53 | 1.70 | 1.43 – 2.04 | <.001* |

| Between person predictor | −0.74 | 0.47 | 0.17 – 1.21 | .13 | 0.03 | 1.03 | 0.99 – 1.06 | .10 |

| Predictor * linear growth | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.64 – 1.49 | .96 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.99 – 1.02 | .40 |

| Predictor * quadratic growth | 0.12 | 1.13 | 0.90 – 1.43 | .30 | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.99 – 1.01 | .65 |

| Within Effects | ||||||||

| Within person predictor | −0.41 | 0.66 | 0.40 – 1.05 | .09 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.99 – 1.04 | .27 |

| SA Predicted by Problem-Focused Coping | SA Predicted by Avoidant Coping | |||||||

| b | OR | 95% CI (OR) | p-value | b | OR | 95% CI (OR) | p-value | |

| Intercept | −2.40 | 0.09 | 0.04 – 0.18 | <.001* | −2.57 | 0.08 | 0.03 – 0.15 | <.001* |

| Between effects | ||||||||

| Linear growth | −1.56 | 0.21 | 0.14 – 0.29 | <.001* | −1.61 | 0.20 | 0.13 – 0.28 | <.001* |

| Quadratic growth | 0.52 | 1.68 | 1.42 – 2.03 | <.001* | 0.56 | 1.75 | 1.47 – 2.12 | <.001* |

| Between person predictor | −1.84 | 0.16 | 0.03 – 0.67 | .01* | 0.48 | 1.62 | 0.43 – 6.57 | .48 |

| Predictor * linear growth | −0.50 | 0.60 | 0.31 – 1.17 | .14 | −0.05 | 0.95 | 0.51 – 1.78 | .86 |

| Predictor * quadratic growth | 0.23 | 1.26 | 0.88 – 1.82 | .20 | 0.04 | 1.04 | 0.74 – 1.44 | .83 |

| Within effects | ||||||||

| Within person predictor | −0.32 | 0.73 | 0.24 – 2.19 | .56 | 0.66 | 1.94 | 0.69 – 5.71 | .22 |

Note. SA = suicide attempt

Relationship Satisfaction

We did not find support for relationship satisfaction to be related to subsequent suicide attempts, as neither within person relationship satisfaction (b = −0.41; OR = 0.66; p = .09; 95% CI (OR) = 0.40 – 1.05) nor between person relationship satisfaction (b = −0.74; OR = 0.47; p = .13; 95% CI (OR) = 0.17 – 1.21) were associated with suicide attempts over time.

Emotion Regulation

Neither within person emotion regulation (b = 0.01; OR =1.01; p = .27; 95% CI (OR) = 0.99 – 1.04) nor between person emotion regulation were related with the probability of attempting suicide over time (b = 0.03; OR = 1.03; p = .10; 95% CI (OR) = 0.99 – 1.06).

Emotion regulation subscale analysis

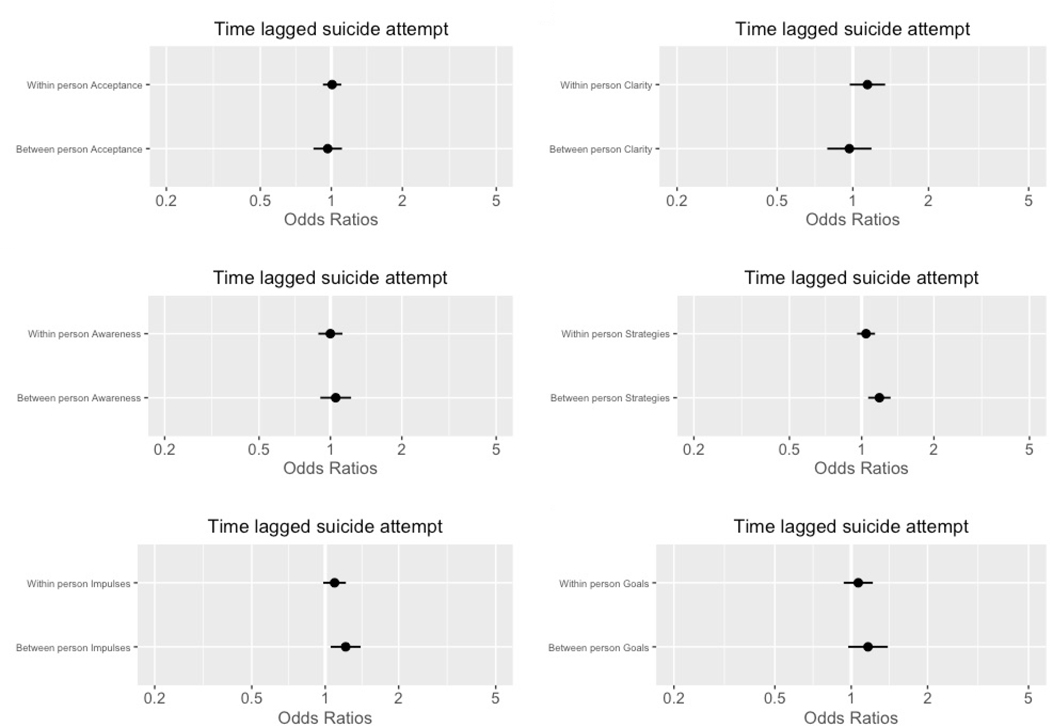

We analyzed the six subscales of the DERS in both univariate models and in one combined multivariate model. Results from univariate models are presented in Table 6 and Figure 1, while results from the combined multivariate model are presented in Table 7 and Figure 2. In both models, between person strategies emerged as a predictor of suicide attempts (b = 0.17; OR = 1.19; p < .01; 95% CI (OR) = 1.07 – 1.33; b = 0.22; OR = 1.25; p < .01; 95% CI (OR) = 1.09 – 1.46). In other words, participants who reported more limited access to emotion regulation strategies were more likely to attempt suicide over time. Between person clarity was not a predictor in a univariate model, but the unique variance of clarity not explained by the other subscales was predictive of suicide attempts in a combined model (b = −0.19; OR = 0.83; p = .04; 95% CI (OR) = 0.69 – 0.99). It is important to note that we observed no within-person effects of specific emotion regulation scales.

Table 6.

Univariate binomial GLMM models of DERS subscales predicting time lagged suicide attempts

| SA Predicted by Emotional Awareness | SA Predicted by Emotional Clarity | |||||||

| b | OR | 95% CI (OR) | p-value | b | OR | 95% CI (OR) | p-value | |

| Intercept | −2.62 | 0.07 | 0.03 – 0.15 | <.001* | −2.62 | 0.07 | 0.03 – 0.15 | <.001* |

| Between Effects | ||||||||

| Linear growth | −1.64 | 0.19 | 0.12 – 0.28 | <.001* | −1.59 | 0.20 | 0.13 – 0.29 | <.001* |

| Quadratic growth | 0.55 | 1.73 | 1.46 – 2.11 | <.001* | 0.55 | 1.73 | 1.47 – 2.12 | <.001* |

| Between person predictor | 0.05 | 1.05 | 0.91 – 1.23 | .51 | −0.03 | 0.97 | 0.78 – 1.18 | .76 |

| Predictor * linear growth | 0.04 | 1.03 | 0.97 – 1.12 | .25 | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.90 – 1.08 | .80 |

| Predictor * quadratic growth | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.97 – 1.04 | .99 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.97 – 1.07 | .59 |

| Within Effects | ||||||||

| Within person predictor | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.89 – 1.12 | .99 | 0.13 | 1.14 | 0.98 – 1.34 | .11 |

| SA Predicted by Acceptance | SA Predicted by ER Strategies | |||||||

| b | OR | 95% CI (OR) | p-value | b | OR | 95% CI (OR) | p-value | |

| Intercept | −2.71 | 0.07 | 0.03 – 0.14 | <.001* | −2.47 | 0.08 | 0.04 – 0.16 | <.001* |

| Between effects | ||||||||

| Linear growth | −1.68 | 0.19 | 0.12 – 0.27 | <.001* | −1.55 | 0.21 | 0.14 – 0.30 | <.001* |

| Quadratic growth | 0.58 | 1.79 | 1.49 – 2.18 | <.001* | 0.53 | 1.70 | 1.44 – 2.06 | <.001* |

| Between person predictor | −0.04 | 0.96 | 0.84 – 1.11 | .62 | 0.17 | 1.19 | 1.07 – 1.33 | <.01* |

| Predictor * linear growth | −0.03 | 0.97 | 0.91 – 1.04 | .45 | 0.04 | 1.04 | 0.99 – 1.10 | .13 |

| Predictor * quadratic growth | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.98 – 1.05 | .33 | −0.02 | 0.98 | 0.95 – 1.01 | .15 |

| Within effects | ||||||||

| Within person predictor | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.92 – 1.10 | .86 | 0.04 | 1.04 | 0.96 – 1.14 | .35 |

| SA Predicted by Impulse | SA Predicted by Goals | |||||||

| b | OR | 95% CI (OR) | p-value | b | OR | 95% CI (OR) | p-value | |

| Intercept | −2.30 | 0.10 | 0.04 – 0.18 | <.001* | −2.50 | 0.08 | 0.04 – 0.16 | <.001* |

| Between effects | ||||||||

| Linear growth | −1.51 | 0.22 | 0.15 – 0.31 | <.001* | −1.57 | 0.21 | 0.14 – 0.29 | <.001* |

| Quadratic growth | 0.51 | 1.66 | 1.41 – 2.00 | <.001* | 0.54 | 1.72 | 1.45 – 2.06 | <.001* |

| Between person predictor | 0.19 | 1.21 | 1.06 – 1.41 | <.01* | 0.15 | 1.16 | 0.98 – 1.41 | .10 |

| Predictor * linear growth | 0.05 | 1.05 | 0.98 – 1.12 | .15 | 0.03 | 1.03 | 0.95 – 1.12 | .46 |

| Predictor * quadratic growth | −0.02 | 0.98 | 0.95 – 1.02 | .30 | −0.01 | 0.99 | 0.94 – 1.03 | .55 |

| Within effects | ||||||||

| Within person predictor | 0.09 | 1.09 | 0.98 – 1.22 | .11 | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.93 – 1.22 | .34 |

Notes: SAs = suicide attempts; ER = emotion regulation

Figure 1.

Univariate estimates of the DERS subscales in relation to prospective suicide risk

Table 7.

Multivariate GLMM model of ER subscales predicting time lagged suicide attempts

| Multivariate GLMM ER model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | OR | 95% CI (OR) | p-value | |

| Intercept | −2.40 | 0.09 | 0.04 – 0.17 | <.001* |

| Between Effects | ||||

| Linear growth | −1.60 | 0.20 | 0.13 – 0.28 | <.001* |

| Quadratic growth | 0.55 | 1.73 | 1.47 – 2.11 | <.001* |

| Between person Emotional Awareness | 0.04 | 1.04 | 0.92 – 1.17 | .48 |

| Between person Emotional Clarity | −0.19 | 0.83 | 0.69 – 0.99 | .04* |

| Between person Acceptance | −0.12 | 0.89 | 0.78 – 1.01 | .05 |

| Between person ER Strategies | 0.22 | 1.25 | 1.09 – 1.46 | <.01* |

| Between person Impulse | 0.09 | 1.09 | 0.94 – 1.29 | .25 |

| Between person Goals | −0.11 | 0.90 | 0.75 – 1.06 | .22 |

| Within Effects | ||||

| Within person Emotional Awareness | −0.11 | 0.90 | 0.77 – 1.04 | .15 |

| Within person Emotional Clarity | 0.14 | 1.15 | 0.93 – 1.44 | .20 |

| Within person Acceptance | −0.07 | 0.93 | 0.82 – 1.05 | .23 |

| Within person ER Strategies | 0.04 | 1.04 | 0.89 – 1.21 | .62 |

| Within person Impulse | 0.04 | 1.04 | 0.89 – 1.22 | .60 |

| Within Person Goals | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.89 – 1.29 | .48 |

Notes: ER = emotion regulation; SAs = suicide attempts; GLMM = generalized linear mixed model

Figure 2.

Estimates of emotion regulation subscales in relation to prospective suicide risk Between person factors (top); Within person predictors (below)

Problem-Focused and Avoidant Coping

Within person problem-focused coping (b = −0.32; OR = 0.73; p = .56; 95% CI (OR) = 0.24 – 2.19) was not significantly associated with time-lagged suicide attempts, however, between person problem-focused coping did have an inverse association with suicide attempts over time (b = −1.84; OR = 0.16; p = .01; 95% CI (OR) = 0.03 – 0.67). Within person avoidant coping was not significant (b = 0.66; OR = 1.94; p = .22; 95% CI (OR) = 0.69 – 5.71), nor was between person avoidant coping (b = 0.48; OR = 1.62; p= .48; 95% CI (OR) = 0.43 – 6.57) in predicting subsequent suicide attempts.

Multivariate Analysis

Results from the multivariate model are presented in Table 6 This model examined the unique variance of both between person problem-focused coping and between person emotion regulation strategies in predicting subsequent suicide attempts. Only between person strategies (b = 0.09; OR = 1.09; p < .01; 95% CI (OR) = 1.03 – 1.17) remained predictive of time lagged suicide attempts. This model suggested, when all other predictors were at zero (i.e., their mean), a 1 unit increase in difficulty accessing emotion regulation strategies was associated with a 9% increase in the odds of attempting suicide at the next time point.

Predicted Probabilities

We used the results from univariate models to calculate predicted probabilities of suicide attempts for the range (+/− 2 SD) of between person problem-focused coping, and between person access to emotion regulation strategies. Results are presented in Figure 3. These models suggested that an individual reporting mean levels of problem-focused coping had about a 20% chance of attempting suicide, a 35% chance if 1 SD below the mean, while someone 2 SD below the mean had a 48% chance of attempting suicide over time. The DERS strategies subscale model suggests that an individual reporting mean levels of DERS Strategies had a 22% chance of attempting suicide, 35% chance if 1 SD above the mean, and someone 2 SD above the mean had a 45% chance of attempting suicide over time.

Figure 3.

Predicted probabilities of attempting suicide by between person problem-focused coping (top) and Predicted probabilities of suicide attempts by ER strategies (bottom)

Discussion

Although several evidence-based treatments for reducing suicide attempts exist, very little research has evaluated factors that explain why suicide attempts decrease in these treatments. The present study sought to determine whether relationship satisfaction, emotion regulation, and coping strategies predict subsequent suicide attempts among high-risk BPD patients during and after DBT. These potential change targets were examined at the between-person level (i.e., on-average differences between patients) as well as the within person level (i.e., a patient’s deviation from their own average at a given time point). Results suggest that, with two exceptions, these hypothesized change targets did not account for subsequent reductions in suicide attempts. We found that lower levels of between person problem-focused coping and less access to emotion regulation strategies were significantly associated with suicide attempts during and in the year after DBT. We did not find relationship satisfaction, other deficits in emotion regulation, or avoidant coping to be significantly associated with suicide re-attempts nor were any within person variables. Multivariate models found that only between person differences in access to emotion regulation strategies was significantly, albeit weakly, associated with subsequent suicide attempts.

We did not find evidence that within or between person relationship satisfaction were strongly associated with suicide attempts. These null effects may be due to the fact that interpersonal processes may have indirect relations with suicidality (e.g., through emotion regulation deficits; Adrian, Zeman, Erdley, Lisa, & Sim, 2011). It could also be that interpersonal functioning has associations with some facets of suicidality (e.g., non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation), that are not specific to suicide attempts, or the null findings may be due to the fact that relationship satisfaction did not change over the course of treatment and follow-up. It is important to mention that our measure of relationship satisfaction was an average of two Likert scales assessing the individuals’ satisfaction with friends and family. There are many interpersonal processes likely to be associated with attempting suicide not covered by this measure, such as rejection sensitivity and perceived burdensomeness.

We also did not find evidence that overall deficits in emotion regulation were strongly associated with suicide attempts in either within person or between person analysis. A recent meta-analysis found consistent cross-sectional relations of emotion dysregulation and nonsuicidal self-injury, including the strategies subscale of the DERS (Wolff et al., 2019), however, our findings suggest that, among a high-risk sample with broad emotion regulation deficits, some of the previous findings are not prospective and limited to some forms of self-injury (e.g., NSSI). Our findings also suggest that the association of emotion regulation and suicide attempts may be limited to one specific deficit in emotion regulation, access to emotion regulation strategies, and that the association is explained by between person differences which do not generalize to within person processes. This finding supports the notion that suicide attempts function as an emotion regulation strategy. People who no longer attempt suicide have access to a broader range of more adaptive emotion regulation skills than individuals continuing to attempt suicide. The lack of an observed significant association between emotion regulation broadly and suicide attempts could also be due to the hierarchical and multi-dimensional nature of the way emotion regulation was measured. It is surprising that within person changes in emotion regulation did not predict subsequent suicide attempts, given that emotion regulation is conceptualized as a core treatment mechanism of DBT (Lynch et al., 2006; Neacsiu et al., 2010).

Problem-focused coping differentiated individuals continuing to attempt suicide from those who stopped, although within person changes in problem-focused coping were not predictive of suicide attempts at the next time point. Prior findings have highlighted the relation between problem solving and suicide attempts in cross-sectional studies (Pollack & Williams, 2004), but no longitudinal or treatment studies have examined how these findings relate to re-attempting suicide. Findings from this study suggests that high levels of problem-focused coping may differentiate people who do not re-attempt suicide from those who continue to attempt suicide. Avoidant coping, either within or between person, was not associated with subsequent suicide attempts. This is also surprising given the strong association between avoidance and suicide (Chapman et al., 2006; Millner et al., 2019). As these two studies examined self-harm and a broad range of suicidal thoughts and behaviors respectively, discrepant findings from this study highlight the need for studies to focus on factors specifically related to suicide attempts. Additionally, it may be that avoidance is related to suicide attempts only through a lack of more direct forms of problem-focused coping.

There are several limitations to this study. First, emotion regulation and coping are highly overlapping constructs. This motivated our analysis of emotion regulation subscales, but still likely limits the conclusions from the final multivariate model with both strategies and problem-focused coping included since multi-collinearity likely biases the estimates produced from these models. However, the fact that these two subscales demonstrated effects, combined with the Benajamini-Hochberg procedure, suggests that these findings are not spurious. Second, a four-month interval between assessment periods may have limited the ability to detect a relationship between within person changes in potential predictors and later suicide attempts, and factors more proximal to a suicide attempt may be better able to predict is occurrence.

Indeed, the lack of with-person effects may be due to the relatively small numbers of suicide attempts and the long interval between assessment points. Future studies, particularly studies focused on the minutes and hours leading up to a suicide attempt, are sorely needed to shed light on within person processes predictive of attempting suicide. Finally, and importantly, the sample was relatively small in size and limited to largely Caucasian women meeting criteria for BPD who had previously attempted suicide and were receiving DBT. This significantly limits the generalizability of these findings and should not be underestimated. It is unknown whether these findings would extend to other populations of suicidal patients (e.g., those without BPD, males) or to other psychotherapies. These findings also do not address people who die by suicide on their first attempt, which prior research has estimated to include up to 75% of individuals dying by suicide (McKean, Pabbati, Geske, & Bostwick, 2018). Moreover, even though the sample was selected based on a high-risk for suicide, there were still relatively few suicide attempts over the course of the study, leading to wide confidence intervals, which limits the certainty of these estimates. The small sample size could also explain the lack of within person effects as we were underpowered to examine these effects. Finally, we chose to collapse the three treatment conditions given the lack of between-group differences in SAs and to increase our overall power. The small sample size within the conditions meant we were underpowered to examine possible treatment moderators. It is possible that the observed predictor effects might vary across the different treatment conditions.

This study highlights the difficulty of predicting suicide attempts in general, including within the context of psychotherapy in particular. The fact that suicide is a relatively low-base rate event leads to a large amount of uncertainty. Additionally, suicide attempts are likely the result of multiple interactive factors coming together at specific moments in time. Studies need to focus on the proximal risk factors of suicide attempts and use methodologies that allow for fine grained analysis of the periods leading up to these events. Nonetheless, problem-focused coping and abilities in emotion regulation do differentiate between individuals likely to make a repeat suicide attempt from those who discontinue attempting suicide, and treatments should continue to focus on teaching these forms of coping and emotion regulation skills to individuals with a history of attempting suicide.

Table 3.

Bivariate correlations of within person predictors

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relationship Satisfaction | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Emotion Dyresgulation | −.03 | - | |||||||||

| 3. Problem Focused Coping | .06 | −.59*** | - | ||||||||

| 4. Avoidant Coping | −.03 | .61*** | −.33*** | - | |||||||

| 5. ER Awareness | .02 | .72*** | −.43*** | .48*** | - | ||||||

| 6. ER Clarity | .01 | .81*** | −.53*** | .49*** | .65*** | - | |||||

| 7. ER Acceptance | −.04 | .84*** | −.43*** | .48*** | .48*** | .58*** | |||||

| 8. ER Strategies | −.05 | .92*** | −.57*** | .61*** | .55*** | .70*** | .72*** | - | |||

| 9. ER Impulse | −.05 | .88*** | −.54*** | .51*** | .52*** | .67*** | .67*** | .81*** | - | ||

| 10. ER Goals | −.01 | .84*** | −.47*** | .51*** | .54*** | .59*** | .66*** | .76*** | .70*** | - | |

| 11. Lagged suicide attempt | −.04 | .32*** | −.09 | .21*** | .26*** | .31*** | .20*** | .27*** | .29*** | .24*** |

Notes:

p < .001

p < .01

p < .05

Table 4.

Bivariate correlations of between person predictors

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relationship Satisfaction | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Emotion Dyresgulation | −.44** | - | |||||||||

| 3. Problem Focused Coping | .33*** | −.48*** | - | ||||||||

| 4. Avoidant Coping | −.34*** | .66*** | −.19*** | - | |||||||

| 5. ER Awareness | −.16*** | .63*** | −.52*** | .51*** | - | ||||||

| 6. ER Clarity | −.25*** | .79*** | −.34*** | .56*** | .63*** | - | |||||

| 7. ER Acceptance | −.28*** | .80*** | −.21*** | .54*** | .36*** | .60*** | - | ||||

| 8. ER Strategies | −.49*** | .90*** | −.45*** | .60*** | .41*** | .59*** | .67*** | - | |||

| 9. ER Impulse | −.42*** | .84*** | −.36*** | .49*** | .32*** | .52*** | .58*** | .79*** | - | ||

| 10. ER Goals | −.47*** | .80*** | −.38*** | .42*** | .27*** | .52*** | .55*** | .77*** | .75*** | - | |

| 11. Lagged suicide attempt | −.11 | .17*** | −.18*** | .10 | .11* | .09 | .08 | .19*** | .18*** | .14*** |

Notes:

p < .001

p < .01

p < .05

Table 8.

Multivariate GLMM model from univariate predictors of time lagged suicide attempts

| Multivariate Model Predicting SA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | OR | 95% CI (OR) | p-value | |

| Intercept | −2.36 | 0.09 | 0.05 – 0.16 | <.001* |

| Between Effects | ||||

| Linear growth | −1.55 | 0.21 | 0.16 – 0.28 | <.001* |

| Quadratic growth | 0.53 | 1.70 | 1.47 – 1.98 | <.001* |

| Between person ER Strategies | 0.09 | 1.09 | 1.03 – 1.17 | <.01* |

| Between person Problem-Focused Coping | −0.58 | 0.56 | 0.24 – 1.28 | .17 |

Notes: SA = suicide attempts; ER = emotion regulation; GLMM = generalized linear mixed model

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01MH034486 (PI - Linehan) and F31MH117827 – 01A1 (PI - Kuehn). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix

This manuscript includes secondary analyses from an RCT testing the importance of DBT skills on treatment outcomes. One other manuscript has been published from this dataset; the present analysis differs from that study in that the present study focuses on suicide attempts as the outcome variable.

Footnotes

Two participants who were included in the larger trial but who did not have a past year suicide attempt were excluded from the present analyses given the focus on predicting suicide reattempt.

References

- Adrian M, Zeman J, Erdley C, Lisa L, & Sim L (2011). Emotional dysregulation and interpersonal difficulties as risk factors for nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(3), 389–400. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9465-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beghi M, Rosenbaum JF, Cerri C, & Cornaggia CM (2013). Risk factors for fatal and nonfatal repetition of suicide attempts: A literature review. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 9, 1725–1736. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S40213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Wood DS, May A, Peterson AL, Wertenberger E, & Rudd MD (2018). Mechanisms of action contributing to reductions in suicide attempts following brief cognitive behavioral therapy for military personnel: A test of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide. Archives of Suicide Research, 22(2), 241–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, & Raudenbush SW (1992). Hierarchical models: Applications and data analysis methods Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AL, Gratz KL, & Brown MZ (2006). Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(3), 371–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Jaser SS, Bettis AH, Watson KH, Gruhn M, Dunbar JP, … Thigpen JC (2017). Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 143(9):939–991. doi: 10.1037/bul0000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decou CR, Comtois KA, & Landes SJ (2018). Dialectical Behavior Therapy Is effective for the treatment of suicidal behavior: A meta-analysis. Behavior Therapy, 50(1), 60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2018.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, & Dunn LM (1981). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised. American Guidance Service, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim E (2005). Suicide: A study in sociology. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla TJ, & Goldfried MR (1971). Problem solving and behavior modification. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 78(1), 107–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, & Tofighi D (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12(2), 121–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Benjamin LS, & Williams JB (1997). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders: SCID-II. American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Gabry J, & Goodrich B (2018). Bayesian Applied Regression Modeling via Stan. R Foundation for Statistical Computing Retrieved from http://discourse.mc-stan.org

- Gratz KL, & Roemer L (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39(3), 281–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris EC, & Barraclough B (1997). Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 170(3), 205–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, & Warner M (2018). Suicide Mortality in the United States, 1999–2017 (Tech. Rep. Nos. NCHS Data Brief, no 330). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T (2005). Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonald-Scott P, & Andreasen NC (1987). The longitudinal interval follow-up evaluation: a comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44(6), 540–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CA, & Merchant CR (2008). Social and interpersonal factors relating to adolescent suicidality: A Review of the literature. Archives of Suicide Research, 12(3), 181–196. doi: 10.1080/13811110802101203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Brown MZ, Heard HL, & Wagner A (2006). Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (SASII): Development, reliability, and validity of a scale to assess suicide attempts and intentional self-injury. Psychological Assessment, 18(3), 303–312. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Heard HL, & Armstrong HE (1993). Naturalistic Follow-up of a Behavioral Treatment for Chronically Parasuicidal Borderline Patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50(12), 971. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240055007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS, Gallop RJ, Lungu A, Neacsiu AD, … Murray-Gregory AM (2015). Dialectical Behavior Therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(5), 475. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loranger AW (1988). Personality Disorder Examination (PDE) manual. DV Communications. [Google Scholar]

- Liu FG, & Zhan X (2011). Comparisons of methods for analysis of repeated binary responses with missing data. Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics, 21(3), 371–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch T, Chapman A, Rosenthal M, Kuo J, & Linehan M (2006). Mechanisms of change in dialectical behavior therapy: theoretical and empirical observations. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(4), 1197–201. doi: 10.1002/jclp [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKean AJ, Pabbati CP, Geske JR, & Bostwick JM (2018). Rethinking lethality in youth suicide attempts: first suicide attempt outcomes in youth ages 10 to 24. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(10), 786–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller IW, Camargo CA, Arias SA, Sullivan AF, Allen MH, Goldstein AB, … others (2017). Suicide prevention in an emergency department population: the ed-safe study. JAMA psychiatry, 74(6), 563–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millner AJ, den Ouden HE, Gershman SJ, Glenn CR, Kearns JC, Bornstein AM, … Nock MK (2019). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors are associated with an increased decision-making bias for active responses to escape aversive states. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128(2), 106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner A, Spittal MJ, Kapur N, Witt K, Pirkis J, & Carter G (2016). Mechanisms of brief contact interventions in clinical populations: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, & Arias E (2018). Mortality in the United States, 2017 (Tech. Rep. Nos. NCHS Data Brief, no 328). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neacsiu AD, Fang CM, Rodriguez M, & Rosenthal MZ (2018). Suicidal behavior and problems with emotion regulation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 48(1), 52–74. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neacsiu AD, Rizvi SL, & Linehan MM (2010). Dialectical behavior therapy skills use as a mediator and outcome of treatment for borderline personality disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(9), 832–839. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RC, & Nock MK (2014). The psychology of suicidal behaviour. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(1), 73–85. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70222-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Wall M, Wang S, Crystal S, Gerhard T, & Blanco C (2017). Suicide following deliberate self-harm. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(8), 765–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack L, & Williams M (2004). Problem-solving in suicide attempters. Psychological Medicine, 34, 163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from http://www.r-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Gistau V, Baeza I, Arango C, Parellada M, Graell M, Paya B, … Castro-fornieles J (2013). Predictors of suicide attempt in early-onset, first-episode psychoses: A longitudinal 24-month follow-up study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(1), 59–66. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m07632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, McCarthy DM, & Zapolski TC (2009). On the value of homogeneous constructs for construct validation, theory testing, and the description of psychopathology. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 272–284. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CD, Quinn A, Plever S, & Emmerson B (2009). Comparing cognitive behavior therapy, problem solving therapy, and treatment as usual in a high risk population. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 39(5), 538–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke G (1997). Linear mixed models for longitudinal data In Linear mixed models in practice (pp. 63–153). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano PP, Russo J, Carr JE, Maiuro RD, & Becker J (1985). The ways of coping checklist: Revision and psychometric properties. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 20(1), 3–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, & Bothwell S (1976). Assessment of social adjustment by patient self-report. Archives of General Psychiatry, 33(9), 1111–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JC, Thompson E, Thomas SA, Nesi J, Bettis AH, Ransford B, … Liu RT (2019). Emotion dysregulation and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry, 59, 25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You S, Van Orden KA, & Conner KR (2011). Social connections and suicidal thoughts and behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25(1), 180–184. doi: 10.1037/a0020936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]