Abstract

Prior infection with adenovirus 36 (Adv36) has been associated with increased adiposity, improved insulin sensitivity, and a lower prevalence of diabetes. This study investigated the prevalence of Adv36 seropositivity and its association with obesity and diabetes among adults attending a diabetes centre in the UAE.Participants (N = 973) with different weight and glucose tolerance categories were recruited. Adv36 seropositivity (Adv36 + ) was assessed using ELISA. Differences among groups were analyzed using statistical tests as appropriate to the data. Prevalence of Adv36+ in the study population was 47%, with no significant difference in obese and non-obese subgroups (42.5% vs 49.6% respectively; p=non-significant). Females were more likely to be Adv36+ compared to males (odds ratio 1.78; 95% CI 1.36–2.32, p < 0.001). We found no significant association between Adv36 seropositivity and different BMI categories, or glucose tolerance status. In our population, the effect of Adv36 infection on lipid profile varied between healthy individuals and individuals with obesity. Adv36 infection is more prevalent in the UAE than in other countries but has no association with obesity. Our study found that females were more likely to be Adv36 positive regardless of weight or diabetes status.

Subject terms: Predictive markers, Epidemiology

Introduction

Obesity is the fifth leading risk factor for global deaths, and promotes the development of several chronic illnesses, including cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and diabetes1. The global obesity prevalence has increased dramatically over the last 40 years, from 3.2% in 1975 to 10.8% in 2014 in men, and from 6.4% to 14.9% in women. In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, obesity prevalence surpassed 30% in 2014. The largest share of the world’s population with severe obesity in 2014 was in high income English-speaking countries (27.1%; 50 million), followed by 13.9% (26 million) in the MENA region2. Furthermore, according to the global burden of disease (GBD) study3, the MENA region had the second highest prevalence of obesity in women of 33.9% in 2013. The majority of the countries within the MENA region are among those with the highest rates of obesity worldwide3.

Studies investigating the reasons underlying the epidemic of obesity in the MENA region have mainly focused on the role of sociocultural variables including dietary, lifestyle and physical activity in addition to hereditary factors. Along with the dramatic rise in obesity has come a rapid rise in diabetes in the MENA region, which now has the second highest prevalence in the world4.

Over the last 20 years, there has been accumulating evidence supporting the hypothesis that viral infections may be associated with obesity in animals and humans. Eight infectious agents, including canine distemper virus, Rous associated virus, type 7 (RAV-7), Borna virus, scrapie agents, SMAM-1 avian adenovirus, human adenovirus-5, human adenovirus-37, and human adenovirus-36 (Adv36) have been implicated in contributing to obesity in animals and humans5. Adenoviruses are the only infectious agents reported to be linked with adiposity in both experimental animal models and human studies6.

Three human adenoviruses have been related to obesity, with adenovirus 36 being the most studied serotype7–9. Bioinformatics comparisons have identified significant differences between Adv36 and other human adenoviruses, suggesting unique functions of Adv36 that possibly can be linked with adipose tissue10.

In humans, the correlation of natural Adv36 infection with the development of obesity has been implicated in several studies across different ethnic populations, in both adults and children. Association of Adv36 infection with obesity in humans was first reported from a US population11. Although a few studies have been inconsistent with these findings12–14, many others in multiple ethnic populations, including North Americans15–18, Mexico19, Europeans20–24, Turkey25,26 and East Asians27,28, Chileans29 have confirmed them. The prevalence of adenovirus seropositivity differed across ethnic groups, with an average prevalence ranging from 65% in Italy to 6% in Belgium/Holland13.

The association of Adv36 with diabetes is more controversial. In vitro studies show Adv36 enhances glucose transport into cells and improves insulin sensitivity. Animal studies also show that Adv36 infection improves glucose tolerance and tends to lower insulin levels30,31. Some human studies indicate a decreased prevalence of diabetes in individuals with Adv36 antibodies28,32, but others have suggested that prior Adv36 infection is associated with a higher prevalence of diabetes33.

In 2013, the UAE was estimated to have an obesity prevalence of 29% among adults, and was ranked number 21 worldwide3 and to have a prevalence of diabetes of 15.58% in 201734. In this study, we aimed to investigate the role of Adv36 infection in the epidemic of obesity and diabetes in this population by: (1) identifying the prevalence of Adv36 seropositivity among adults living in the UAE; and (2) assessing the association of Adv36 with obesity and diabetes in the population.

Results

Study population characteristics and prevalence of Adenovirus 36 seropositivity

Characteristics of the population studied are summarized in Table 1. Ninety percent (N = 875) of the study population were Emiratis (natives of the United Arab Emirates) and the remaining were expatriates, predominantly of Arab ethnicity. Among the 973 adults who participated in the study, 458 (47.1%) were found to be seropositive for Adv36 while 515 (52.9%) were seronegative. The sex distribution among the participants was comparable with a male to female ratio of 0.96. The prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) in this population was 35.8%; a further 35.6% were overweight (BMI ≥ 25 and ≤29.9 kg/m2) and 28.6% had a normal weight (BMI ≤ 24.9 kg/m2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population.

| Characteristics | Sub group | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| N | Male | 477 (49.1) |

| Female | 496 (50.9) | |

| Total | 973 | |

| Adenovirus 36 | Seropositive | 458 (47.1) |

| Seronegative | 515 (52.9) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <24.9 (Normal weight) | 278 (28.6) |

| 25–29.9(Overweight) | 346 (35.6) | |

| >30 (Obese) | 349 (35.8) | |

| Characteristics | Sub-group | Mean ± SD |

| Age (years) | Male | 43.3 ± 13.8 |

| Female | 42.4 ± 12.9 | |

| All Subjects | 42.9 ± 13.4 | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | All subjects | 95.8 ± 12.8 |

| Waist to hip ratio | All Subjects | 0.9 ± 0.08 |

| Blood Pressure (mmHg) | Systolic | 120.2 ± 16.8 |

| Diastolic | 71.3 ± 21.7 | |

| Lipid Profile (mmol/l) | HDL-c | 1.3 ± 0.4 |

| LDL-c | 2.9 ± 0.9 | |

| TC | 4.5 ± 1.0 | |

| TG | 1.4 ± 0.9 | |

| Glycaemic Control | HbA1C (%) | 6.6 ± 1.6 |

BMI: Body mass index, LDL-c: Low Density Lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL-c: High Density Lipoprotein cholesterol, TC: Total Cholesterol, TG: Triglycerides, HbA1c: Glycosylated Haemoglobin.

Comparison of Adv36 seropositive and seronegative participants

Comparison of mean BMI, HbA1c, lipid profile, and body composition between seropositive and seronegative individuals are summarized in Table 2. After adjusting for age, gender and BMI, there was no significant difference in clinical and anthropological parameters between Adv36+ and Adv36- groups. Other clinical parameters such as Blood pressure, Liver enzymes and haemoglobin were also compared between the two groups (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2.

Difference in clinical and anthropometric parameters between Adv36 seropositive and seronegative individuals.

| Overall (N = 973) | Males (N = 477) | Females (N = 496) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADV 36 (+) | ADV 36 (-) | P value | ADV 36 (+) | ADV 36 (-) | P value | ADV 36 (+) | ADV 36 (-) | P value | |

| N | 458 | 515 | 197 | 280 | 261 | 235 | |||

| Anthropometry | |||||||||

| Age (yrs.) | 42.2 ± 13.9 | 42.6 ± 14.0 | 0.622a | 41.9 ± 14.3 | 43.6 ± 14.3 | 0.199a | 42.4 ± 13.7 | 41.4 ± 13.7 | 0.439a |

| Weight (kg) | 76.2 ± 17.0 | 79.0 ± 16.3 | 0.09 | 82.0 ± 15.9 | 82.5 ± 16.4 | 0.71 | 71.8 ± 16.5 | 74.8 ± 15.1 | 0.26 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.5 ± 5.7 | 28.9 ± 5.6 | 0.158 | 27.8 ± 4.7 | 28.0 ± 5.0 | 0.539 | 29.0 ± 6.3 | 29.8 ± 6.0 | 0.148 |

| Waist (cm) | 95.2 ± 13.5 | 96.3 ± 12.0 | 0.427 | 98.7 ± 12.2 | 98.2 ± 12.0 | 0.117 | 91.8 ± 13.5 | 94.1 ± 12.0 | 0.067 |

| WHR | 0.9 ± 0.08 | 0.9 ± 0.07 | 0.284 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.06 | 0.104 | 0.9 ± 0.08 | 0.9 ± 0.07 | 0.48 |

| Body composition | |||||||||

| Fat (%) | 31.3 ± 9.5 | 30.7 ± 9.3 | 0.67 | 25.1 ± 7.3 | 25.4 ± 7.0 | 0.957 | 36.3 ± 7.9 | 37 ± 7.5 | 0.236 |

| Fat Mass (kg) | 25.0 ± 11.4 | 25.5 ± 10.8 | 0.178 | 21.5 ± 10.1 | 22.2 ± 10.7 | 0.588 | 27.3 ± 11.7 | 28.7 ± 10.7 | 0.147 |

| Fat Free mass (kg) | 52.4 ± 10.8 | 54.3 ± 10.3 | 0.365 | 60.9 ± 8.7 | 60.7 ± 8.7 | 0.617 | 44.8 ± 5.7 | 46.1 ± 5.9 | 0.03 |

| Lipid profile | |||||||||

| HDL-c (mmol/L) | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 0.156 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 0.793 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.038 |

| LDL-c (mmol/L) | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 0.308 | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 0.127 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 0.993 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 0.354 | 4.3 ± 1.0 | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 0.163 | 4.6 ± 0.9 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 0.961 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 0.704 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 0.766 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 0.205 |

| Glycaemic profile | |||||||||

| HbA1c (%) | 6.7 ± 1.8 | 6.5 ± 1.7 | 0.055b | 6.9 ± 1.9 | 6.7 ± 1.6 | 0.2 | 6.5 ± 1.7 | 6.2 ± 1.6 | 0.037 |

ANCOVA with age, gender and BMI as covariates. BMI: Body mass index, WHR: Waist to Hip Ratio, HDL-c: High Density Lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-c: Low Density Lipoprotein cholesterol, TC: Total Cholesterol, TG: Triglycerides, HbA1c: Glycated Haemoglobin. a Unpaired t test, b Mann - Whitney U test.

Adv36 seropositivity and its associations

Gender

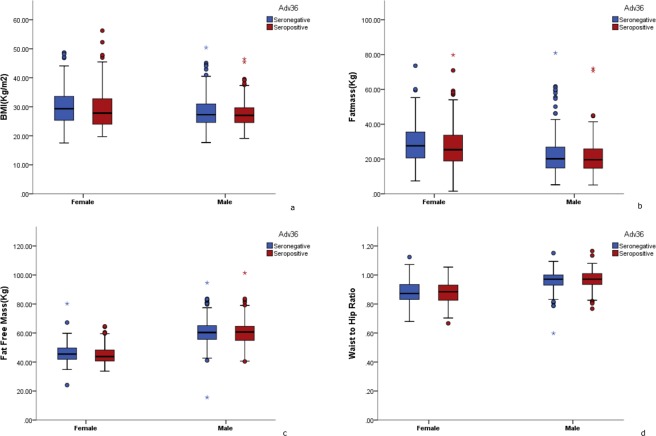

Prevalence of Adv36 seropositivity was significantly higher in women (53%) compared to men (41%) and in general, women had increased likelihood of being Adv36 + (OR 1.78; 95% CI 1.36–2.32, p < 0.001) (Table 3). There was no difference in studied parameters between Adv36 positive and negative men (Fig. 1). However, in women, seropositivity was associated with decreased fat free mass (p = 0.030), increased HDL-c (p = 0.038) and increased HbA1c (p = 0.037) (Table 2).

Table 3.

Association of Adv 36 seropositivity with gender, obesity and diabetes.

| N | ADV 36 + (N %) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 477 | 197 (41.3) | Ref. | |

| Female | 496 | 261 (52.6) | 1.78 (1.36–2.32) | <0.001 |

| Obesity a | ||||

| Non - obese (BMI ≤ 29.9) | 625 | 310(49.6) | Ref. | |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30) | 348 | 148(42.5) | 0.696 (0.532–0.912) | 0.034 |

| BMI Categories b | ||||

| Normal Weight (BMI ≤ 24.9) | 279 | 140 (50.4) | Ref. | |

| Overweight (BMI 25–29.9) | 346 | 169 (48.8) | 0.98 (0.71–134) | 0.889 |

| Obese Class I (BMI 30–34.9) | 221 | 87 (39.7) | 0.61 (0.42–0.87) | 0.007 |

| Obese Class II (BMI 35–39.9) | 84 | 42 (48.8) | 0.95 (0.58–1.55) | 0.834 |

| Obese Class III (BMI ≥ 40) | 43 | 20 (45.4) | 0.74 (0.39–1.56) | 0.546 |

| Glycaemic Status c | ||||

| Normal Glucose Tolerance | 301 | 135 (44.8) | Ref. | |

| Type 1 Diabetes | 181 | 94 (52.0) | 1.41 (0.97–2.08) | 0.073 |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 289 | 141 (48.8) | 1.45 (0.99–2.13) | 0.055 |

| Prediabetes | 202 | 88 (43.5) | 1.07 (0.74–1.57) | 0.702 |

Logistic regression analysis with Adv36 status (indicator): seropositive and seronegative (seronegative as reference).

aBinary logistic regression analysis; Covariates: Age in years and Gender.

bMultinomial logistic regression analysis; Covariates: Age in years and Gender.

cMultinomial logistic regression analysis; Covariates: Age in years, Gender and BMI.

Figure 1.

Body composition analysis in females and males based on Adv36 status. Blue bars represent Adv36 seronegatives, red bars represent Adv36 seropositives1) Body mass index by sex and Adv36 status 2) Fat mass by sex and Adv36 status, 3) Fat free mass by sex and Adv36 status, 4) Waist to hip ratio by sex and Adv36 status.

Obesity

The prevalence of seropositivity was higher (49.6%) in subjects who were not obese compared to subjects with obesity (42.5%). Seropositivity was found to be negatively correlated with obesity [obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) vs non-obese (BMI ≤ 29.9 kg/m2);(β = −0.362; OR = 0.696 (0.532–0.912); Pearson Chi-Square p = 0.034)]. There was a negative association between BMI categories and Adv36+ overall, and only Class I obesity had statistically significant association with Adv36 + (crude OR 0.61; 95%CI 0.42–0.987, p = 0.007) (Table 3). Adenovirus seropositivity was significantly associated with lower LDL cholesterol (p = 0.013), total cholesterol (p = 0.009) and triglycerides (p = 0.007) in healthy weight individuals (N = 279). In the subgroup with obesity, Adv36 seropositive individuals had significantly higher total cholesterol (p = 0.023; Table 4).

Table 4.

Difference in clinical and anthropometric characteristics between Adv36 positive and negative groups among subgroups based on BMI.

| Normal weight (N = 279) | Overweight (N = 346) | Obese (N = 348) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADV 36 (+) | ADV 36 (-) | P value | ADV 36 (+) | ADV 36 (-) | P value | ADV 36 (+) | ADV 36 (-) | P value | |

| N | 141 | 138 | 169 | 177 | 148 | 200 | |||

| Anthropometry | |||||||||

| Age (years) | 39.9 ± 14.5 | 41.2 ± 15.7 | 0.485a | 44.2 ± 13.9 | 43.5 ± 14.1 | 0.646a | 41.9 ± 13.3 | 42.8 ± 12.9 | 0.514a |

| Weight (kg) | 60.4 ± 8.2 | 63.5 ± 8.9 | 0.239 | 74.8 ± 9.3 | 75.6 ± 8.3 | 0.923 | 91.9 ± 15.6 | 92.5 ± 14.7 | 0.618 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.8 ± 1.4 | 22.7 ± 1.7 | 0.718 | 27.4 ± 1.5 | 27.3 ± 1.4 | 0.607 | 34.9 ± 4.8 | 34.5 ± 4.2 | 0.455 |

| Waist (cm) | 83.3 ± 9.8 | 85.5 ± 8.9 | 0.541 | 93.6 ± 8.9 | 94.6 ± 7.7 | 0.76 | 105.3 ± 12.1 | 104.5 ± 11.1 | 0.145 |

| WHR | 0.9 ± 0.08 | 0.9 ± 0.09 | 0.654 | 0.9 ± 0.08 | 0.9 ± 0.07 | 0.56 | 0.9 ± 0.08 | 0.9 ± 0.08 | 0.221 |

| Body composition | |||||||||

| Fat (%) | 23.8 ± 7.5 | 22.4 ± 6.9 | 0.513 | 29.9 ± 6.9 | 29.4 ± 7.07 | 0.983 | 39.2 ± 7.6 | 37.6 ± 7.2 | 0.716 |

| Fat Mass (kg) | 14.3 ± 4.6 | 15.1 ± 8.3 | 0.056 | 22.3 ± 5.1 | 22.0 ± 4.76 | 0.991 | 36.3 ± 10.6 | 34.8 ± 9.3 | 0.897 |

| Fat Free mass (kg) | 46.3 ± 8.6 | 49.4 ± 8.7 | 0.208 | 52.9 ± 10.1 | 53.5 ± 9.71 | 0.322 | 55.8 ± 11.3 | 57.6 ± 11.1 | 0.449 |

| Lipid profile | |||||||||

| HDL -c (mmol/L) | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 0.246 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.719 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 0.08 |

| LDL-c (mmol/L) | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 0.013 | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 0.254 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 0.052 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.3 ± 1.0 | 4.6 ± 0.9 | 0.009 | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 0.198 | 4.7 ± 0.9 | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 0.023 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 0.007b | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 0.267 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 0.854 |

| Glycaemic profile | |||||||||

| HbA1c (%) | 6.6 ± 1.8 | 6.8 ± 2.0 | 0.689 | 6.7 ± 1.8 | 6.5 ± 1.6 | 0.164 | 6.8 ± 1.8 | 6.3 ± 1.5 | 0.019b |

ANCOVA with age, gender and BMI as covariates. BMI: Body Mass Index, WHR: Waist to Hip Ratio, HDL-c: High Density Lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein cholesterol, TC: Total Cholesterol, TG: Triglycerides, HbA1c: Glycated Haemoglobin.

a Unpaired t test, b Mann - Whitney U test.

Diabetes status

Type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes and prediabetes showed no significant association with Adv 36 seropositivity (Table 3). There were no differences in studied parameters between Adv36 seropositive and seronegative individuals in different diabetes subgroups and with the normal glucose tolerance group (Table 5). In type 1 diabetes group, there was no difference in mean Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase (GAD) antibody titer between ADV 36 seropositive and seronegative individuals (p = 0.272). However, when individuals with type 1 diabetes were stratified into GAD negative, low positive and positive subgroups, Adv36 seropositivity significantly correlated with high GAD antibody titer (Spearman p = 0.036) (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 5.

Difference in clinical and anthropometric characteristics between Adv36 positive and negative groups among subgroups based on glycaemic status.

| NGT (N = 301) | Prediabetes(N = 202) | Type 1(N = 181) | Type 2 (N = 289) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADV 36 (+) | ADV 36 (-) | P value | ADV 36 (+) | ADV 36 (-) | P value | ADV 36 (+) | ADV 36 (-) | P value | ADV 36 (+) | ADV 36 (-) | P value | |

| N | 135 | 166 | 88 | 104 | 94 | 87 | 141 | 148 | ||||

| Anthropometry | ||||||||||||

| Age (yrs.) | 36.7 ± 11.3 | 37.8 ± 11.5 | 0.399a | 43.9 ± 9.8 | 43.4 ± 12.3 | 0.750a | 31.6 ± 10.0 | 33.2 ± 12.3 | 0.327a | 53.8 ± 11.4 | 53.5 ± 10.8 | 0.864a |

| Weight (kg) | 73.2 ± 19.9 | 76.7 ± 1.3 | 0.24 | 81.0 ± 17.8 | 84.8 ± 16.2 | 0.266 | 74.3 ± 17.4 | 76.0 ± 14.0 | 0.808 | 77.4 ± 17.2 | 78.6 ± 15.2 | 0.875 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.6 ± 5.2 | 28.4 ± 5.9 | 0.247 | 30.4 ± 6.5 | 30.8 ± 5.4 | 0.288 | 27.3 ± 5.0 | 27.2 ± 4.7 | 0.973 | 28.9 ± 5.8 | 28.7 ± 5.4 | 0.967 |

| Waist (cm) | 93.8 ± 11.6 | 94.9 ± 13.0 | 0.063 | 95.3 ± 11.3 | 98.9 ± 10.9 | 0.11 | 89.8 ± 14.8 | 91.6 ± 11.7 | 0.411 | 99.1 ± 12.3 | 98.8 ± 11.7 | 0.425 |

| WHR | 0.8 ± 0.08 | 0.9 ± 0.08 | 0.098 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 0.9 ± 0.06 | 0.101 | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 0.9 ± 0.07 | 0.412 | 0.9 ± 0.06 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 0.087 |

| Body composition | ||||||||||||

| Fat (%) | 31.0 ± 9.3 | 30.4 ± 9.4 | 0.564 | 34.0 ± 9.7 | 33.1 ± 9.0 | 0.706 | 28.2 ± 9.0 | 28.0 ± 9.0 | 0.218 | 32.0 ± 9.2 | 30.7 ± 9.1 | 0.832 |

| Fat Mass (kg) | 23.4 ± 10.0 | 24.5 ± 12.1 | 0.527 | 26.6 ± 12.8 | 28.2 ± 11.6 | 0.692 | 21.6 ± 9.9 | 21.9 ± 9.5 | 0.142 | 25.4 ± 11.8 | 24.9 ± 9.9 | 0.353 |

| Fat Free mass (kg) | 50.4 ± 9.3 | 52.6 ± 10.7 | 0.745 | 53.1 ± 10.9 | 56.1 ± 10.4 | 0.841 | 53.0 ± 12.2 | 54.3 ± 8.8 | 0.905 | 52.0 ± 10.7 | 53.6 ± 10.9 | 0.169b |

| Lipid profile | ||||||||||||

| HDL-c (mmol/L) | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 0.304 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.057 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 0.562 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.464 |

| LDL-c (mmol/L) | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 0.779 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 0.471 | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 0.921 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 0.325 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.6 ± 0.9 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 0.888 | 4.8 ± 0.9 | 4.7 ± 0.9 | 0.397 | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 0.673 | 4. 1 ± 0.9 | 4.2 ± 1.0 | 0.232 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 0.362 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 0.365 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 0.874 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 1.1 | 0.475 |

| Glycaemic profile | ||||||||||||

| HbA1c (%) | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 0.897 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 0.454 | 8.3 ± 1.7 | 8.2 ± 1.7 | 0.676 | 7.5 ± 1.6 | 7.2 ± 1.6 | 0.202 |

ANCOVA with age, gender and BMI as covariates. NGT: Normal Glucose Tolerance, BMI: Body Mass Index, WHR: Waist to Hip Ratio, HDL-c: High Density Lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL: Low Density Lipoprotein cholesterol, TC: Total Cholesterol, TG: Triglycerides, HbA1C: Glycated Haemoglobin.

a Unpaired t test, b Mann - Whitney U test.

Discussion

Obesity and type 2 diabetes are highly prevalent in the Middle East. The rapid increased prevalence in the Gulf region in the last few decades is generally attributed to urbanisation and the accompanying unfavourable lifestyle changes. While there are no doubts about the drastic change in lifestyle in this region, whether the physical lifestyle change alone can be responsible for a phenomenon rightly termed an epidemic is a matter of debate.

Epidemics are often attributable to infectious organisms including viruses. It is thus not surprising that a virus that has been proven as a causative agent of obesity. In vivo infection with Adv36 in primates35, rodents, and chickens30 have shown increases in body fat and weight gain. Meta analyses suggest association of Adv36 infection with risk of obesity and weight gain36,37.

In the current study, we found around 47% Adenovirus 36 seropositivity prevalence in the UAE population. This prevalence is similar to that reported from Iran38 and Italy22,23, but higher than that reported from US11, South Korea27 and Sweden21, and lower than Mexico19. To our knowledge, ours is the first such study in an Arab population. Similar to studies from Iran38 and China39, and in contrast to several other studies, in our population, we found no correlation between Adv36 seropositivity with obesity in spite of its the high prevalence.

Apart from having an effect on fat accumulation and weight gain, Adv36 infection has been reported to result in metabolic changes including alterations in lipid profile. The mechanisms of altered lipid profile in Adv 36 seropositive individuals remains unclear11.The reports are inconsistent and range from favourable effect on the serum lipid profile in Adults in US population11 to an undesirable increase in LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol and triglycerides and a decrease in HDL cholesterol in other populations20. In our population, the effect of Adv36 infection on lipid profile varied between healthy individuals and individuals with obesity. Among individuals with healthy BMI ( ≤ 24.9), decreased serum levels of LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol and triglycerides were observed in Adv36 positive individuals. However, Adv36 infection in individuals with obesity was found to be associated with increased HDL, LDL and Total cholesterol in the population we studied. The protective or favourable effect of Adv 36 seropositivity on the lipid profile might be masked by obesity in this group.

Other effects of Adv 36 infection include changes in insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance status. Adv36 infection has been linked to enhanced insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake in vitro8,30,40–42 and improved glucose tolerance and/or insulin sensitivity in humans and animals28,31–33. Interestingly, we did not find an improved glucose tolerance in Adv36 seropositive subjects in our study. Indeed, we found a significantly higher HbA1c in Adv36 seropositive patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes, p = 0.004 (Supplementary Table 3). Viral infections are known to trigger autoimmunity in pancreatic beta cells and further clinical presentation of type 1 diabetes43. However, association of Adv36 infection with GAD antibodies has not been reported so far. In our patients with type 1 diabetes, Adenovirus 36 seropositivity was associated a high GAD antibody titer suggesting that adenovirus infection could be a trigger for autoimmunity in pancreatic beta cells.

Establishing a causative role for an infective organism in human obesity is challenging for ethical reasons. Population studies such as the current study may offer support to such hypotheses. However, results from different studies have been inconsistent and reported association with obesity and diabetes has been variable. It may be that for Adv36 exposure to result in obesity humans the presence of some other predisposition such as racial or genetic background is needed.

Another possibility for the variation in Adv36 prevalence in different populations may be methodological. Serum neutralizing assay and ELISA are broadly used to measure the presence of ADV36 infection. If a given ELISA assay is insufficiently specific, it will pick up antibodies against other adenoviruses and dilute the Adv36-obesity correlation. This has been shown for some ELISAs in comparison to the serum neutralization assay44. However, the serum neutralization assay is significantly less sensitive than our ELISA assay. In a study from Sweden, we reported that the ELISA scored positive for 36.9% of the Adv36-SNA-seronegative samples24. Additional studies in our lab comparing known highly Adv36 positive samples serially diluted showed that the ELISA was 2–4 fold more sensitive than serum neutralization. Furthermore, this ELISA assay was tested against other animal and human adenovirus antibodies and found that there is little or no cross-reaction confirming the specificity of the test for Adenovirus 36 (unpublished data).

Finally, the absence of correlation of Adv36 seropositivity and obesity in our current study and in some other more recent studies38,39 as compared to the fairly strong correlations in earlier reports, suggests changes in the virus, or the environment. However, Na et al. showed that Adv36 was very stable across three decades with essentially no mutation45. It is noteworthy that the more recent studies with higher Adv36 seropositivity have been conducted mostly in the Asian populations38,39. Potentially, other changing environmental factors may be of importance in predisposing Adv36 positive individuals to the effects of the virus on adipose tissue46. It is also possible that as with many other viral infections, Adv36 antibody titers decrease over time to levels below the value for “positivity”, and thus diluting an otherwise expected association with obesity.

In conclusion, we have identified a high overall prevalence of Adv36 seropositivity, but no apparent association with weight in an Arab Middle Eastern population with a rapid rise in obesity and diabetes prevalence over a relatively short period. We have also shown a hitherto unreported finding of a higher GAD titer in Adv 36 seropositive patients with type 1 diabetes and also found Adv36 seropositivity to be associated with worse glycaemic control in women and people with obesity. The findings of this study are somewhat different from those reported in Europe and America and these findings merit confirmation in other populations.

Methods

Study population

The study was conducted at Imperial College London Diabetes Centre (ICLDC), Abu Dhabi. The ICLDC is a large out-patient facility, offering medical care to patients with diabetes, obesity, endocrine and general medical conditions. Participants were recruited with a pre-defined target population with the aim of achieving comparable number of subjects from different BMI classes and glucose tolerance. The study subjects were recruited from among patients visiting the clinic during their regular visits. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants at the time of recruitment. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at ICLDC and followed the Declaration of Helsinki, 1996.

Anthropometric measures and clinical examination

All participants were examined by trained nurses at ICLDC. Anthropometric measures were made, and included weight, height, waist and hip circumference and blood pressure. Height was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm, and body weight was measured to the nearest 100 g. Waist circumference was measured at the midpoint between ribs and iliac crest, and hip circumference was measured at the greater trochanters. Waist-to-hip ratio was calculated as waist circumference (cm) divided by hip circumference (cm). Body composition including BMI, fat percentage, fat mass and fat free mass were analysed using bio electric impedance analyzer (SECA, Hamburg, Germany). Obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2. Relevant clinical data were extracted from patients’ electronic records at time of recruitment, and included age of onset of obesity and/or diabetes, family history of obesity and/or diabetes, complications of obesity and/or diabetes, and smoking history. Alcohol intake was not recorded as consumption in the population studied is known to be rare. Classification of diabetes type was based on American Diabetes Association guidelines 2019.

Laboratory investigations

Blood samples were collected from participants following an overnight fast. HbA1c, haemoglobin and Lipid profile were analysed as part of routine laboratory investigations and the results were extracted from the electronic records. Presence of Adv36 antibodies in serum were assayed using the competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method (ELISA-Obetech Laboratories, Richmond VA)21,24. Samples were sent in batches and were anonymized to maintain confidentiality and blinding. Results of the assays were sent to the principal investigator along with the ELISA cut off values. Based on the cut-off values in each ELISA assay, samples were coded seropositive or seronegative.

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics of the study population were analysed for frequency and mean distribution using descriptive statistics function. Homogeneity of variable distributions were tested using Levene’s test47. Binary logistic regression analysis on Adv 36 seropositivity was performed between individuals with and without obesity with age and gender as covariates. Differences in characteristics between Adv36 seropositive and seronegative groups were analysed using unpaired t test and ANCOVA with age, gender and BMI as covariates for normally distributed variables and Mann - Whitney U test for non-normally distributed variables. Differences in characteristics based on Adv36 status were analysed in males and females separately to avoid sex bias. The variables were transformed using natural logarithm to normalise the data and were analysed for differences in means in seropositive and seronegative groups. The sample population was further stratified into groups based on BMI (Healthy, Overweight, Obese I, Obese II and Obese III) and Glycaemic status (Normal, Prediabetic, Type 1 and Type 2) and analysed for differences in characteristics between Adv36 positive and negative subjects. Multinomial logistic regression on Adv36 seropositivity among different BMI groups and Glycaemic statuses were also performed with the healthy group and normal glucose tolerance group as references respectively. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Ms Zara Hannoun and Ms Kristel Gines towards the conduct of the study. This research was funded by Imperial College London Diabetes Centre, a Mubadala Company.

Author contributions

N.L. and R.L.A. designed the study and contributed to the manuscript. K.R.S. performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. B.A. collected data and contributed to the manuscript writing. M.M. contributed to statistical analysis and manuscript writing. Z.P.L.L. performed the Adv36 assays and reviewed and contributed to the manuscript. M.T.B. reviewed and contributed to the manuscript. N.L. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis.

Competing interests

Nader Lessan, Koramannil Radha Saradalekshmi, BudourAlkaf, Maria Majeed and Maha T Barakat declare no competing interest. Richard Atkinson owned Obetech LLC, a closed company that provided Adv36 assays and had patents regarding Adv36. Zendra PL Lee was an employee of Obetech.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-65008-x.

References

- 1.Bray GA, Bellanger T. Epidemiology, trends, and morbidities of obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Endocrine. 2006;29:109–117. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:29:1:109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collaboration NRF. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19· 2 million participants. The Lancet. 2016;387:1377–1396. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30054-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The lancet. 2014;384:766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abuyassin B, Laher I. Diabetes epidemic sweeping the Arab world. World journal of diabetes. 2016;7:165. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v7.i8.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkinson, R. L. in Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1192-1198 (Elsevier). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Akheruzzaman M, Hegde V, Dhurandhar NV. Twenty‐five years of research about adipogenic adenoviruses: A systematic review. Obesity Reviews. 2019;20:499–509. doi: 10.1111/obr.12808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhurandhar N, et al. Increased adiposity in animals due to a human virus. International journal of obesity. 2000;24:989. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vangipuram S, et al. Adipogenic human adenovirus-36 reduces leptin expression and secretion and increases glucose uptake by fat cells. International journal of obesity. 2007;31:87. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whigham LD, Israel BA, Atkinson RL. Adipogenic potential of multiple human adenoviruses in vivo and in vitro in animals. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2006;290:R190–R194. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00479.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold J, et al. Genomic characterization of human adenovirus 36, a putative obesity agent. Virus research. 2010;149:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atkinson RL, et al. Human adenovirus-36 is associated with increased body weight and paradoxical reduction of serum lipids. International Journal Of Obesity. 2004;29:281. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broderick, M. et al. Adenovirus 36 seropositivity is strongly associated with race and gender, but not obesity, among US military personnel. International journal of obesity 34, 302 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.J.Goossens V, et al. Lack of Evidence for the Role of Human Adenovirus‐36 in Obesity in a European Cohort. Obesity. 2011;19:220–221. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bil-Lula I, et al. Infectobesity in the Polish population-evaluation of an association between adenoviruses type 5, 31, 36 and human obesity. International Journal of Virology and Molecular Biology. 2014;3:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atkinson RL, Lee I, SHIN HJ, He J. Human adenovirus‐36 antibody status is associated with obesity in children. Pediatric Obesity. 2010;5:157–160. doi: 10.3109/17477160903111789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vander Wal JS, Huelsing J, Dubuisson O, Dhurandhar NV. An observational study of the association between adenovirus 36 antibody status and weight loss among youth. Obesity facts. 2013;6:269–278. doi: 10.1159/000353109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voss JD, Burnett DG, Olsen CH, Haverkos HW, Atkinson RL. Adenovirus 36 antibodies associated with clinical diagnosis of overweight/obesity but not BMI gain: a military cohort study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2014;99:E1708–E1712. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berger PK, et al. Association of adenovirus 36 infection with adiposity and inflammatory-related markers in children. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2014;99:3240–3246. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parra-Rojas, I. et al. Adenovirus-36 seropositivity and its relation with obesity and metabolic profile in children. International journal of endocrinology 2013 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Aldhoon-Hainerová I, et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of 1179 Czech adolescents evaluated for antibodies to human adenovirus 36. International Journal Of Obesity. 2013;38:285. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Almgren M, et al. Adenovirus-36 is associated with obesity in children and adults in Sweden as determined by rapid ELISA. Plos one. 2012;7:e41652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trovato GM, et al. Human obesity relationship with Ad36 adenovirus and insulin resistance. International Journal Of Obesity. 2009;33:1402. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trovato GM, et al. Adenovirus-36 seropositivity enhances effects of nutritional intervention on obesity, bright liver, and insulin resistance. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2012;57:535–544. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1903-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabin M, et al. Longitudinal investigation of adenovirus 36 seropositivity and human obesity: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. International journal of obesity. 2015;39:1644. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ergin S, et al. The role of adenovirus 36 as a risk factor in obesity: the first clinical study made in the fatty tissues of adults in Turkey. Microbial pathogenesis. 2015;80:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karamese M, Altoparlak U, Turgut A, Aydogdu S, Karamese SA. The relationship between adenovirus-36 seropositivity, obesity and metabolic profile in Turkish children and adults. Epidemiology & Infection. 2015;143:3550–3556. doi: 10.1017/S0950268815000679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Na H, et al. Association of human adenovirus-36 in overweight Korean adults. International Journal of Obesity. 2012;36:281. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin W-Y, et al. Long-Term Changes in Adiposity and Glycemic Control Are Associated With Past Adenovirus Infection. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:701–707. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sapunar, J. et al. Adenovirus 36 seropositivity is related to obesity risk, glycemic control, and leptin levels in Chilean subjects. International Journal of Obesity, 1 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Pasarica M, et al. Human adenovirus 36 induces adiposity, increases insulin sensitivity, and alters hypothalamic monoamines in rats. Obesity. 2006;14:1905–1913. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhurandhar NV, Dhurandhar EJ, Ingram DK, Vaughan K, Mattison JA. Natural infection of human adenovirus 36 in rhesus monkeys is associated with a reduction in fasting glucose. Journal of diabetes. 2014;6:614–616. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almgren M, et al. Human adenovirus-36 is uncommon in type 2 diabetes and is associated with increased insulin sensitivity in adults in Sweden. Annals of medicine. 2014;46:539–546. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.935469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waye, M., Chan, J., Tong, P., Ma, R. & Chan, P. Association of human adenovirus-36 with diabetes, adiposity, and dyslipidaemia in Hong Kong Chinese. Hong Kong Med J 21 (2015). [PubMed]

- 34.IDF. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 8th Edition, 2017, Country reports -United Arab Emirates, http://reports.instantatlas.com/report/view/846e76122b5f476fa6ef09471965aedd/ARE (2017).

- 35.Dhurandhar NV, et al. Human adenovirus Ad-36 promotes weight gain in male rhesus and marmoset monkeys. The Journal of Nutrition. 2002;132:3155–3160. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.10.3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qinglong S, et al. Serological data analyses show that adenovirus 36 infection is associated with obesity: A meta‐analysis involving 5739 subjects. Obesity. 2014;22:895–900. doi: 10.1002/oby.20533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamada T, Hara K, Kadowaki T. Association of Adenovirus 36 Infection with Obesity and Metabolic Markers in Humans: A Meta-Analysis of Observational. Studies. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ehsandar S, et al. Prevalence of Human Adenovirus 36 and Its Association with Overweight/Obese and Lipid Profiles in the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Iranian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2014;16:88–94. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou, Y. et al. The relationship between human adenovirus 36 and obesity in Chinese Han population. Bioscience reports, BSR20180553 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Wang ZQ, et al. Human Adenovirus Type 36 Enhances Glucose Uptake in Diabetic and Nondiabetic Human Skeletal Muscle Cells Independent of Insulin Signaling. Diabetes. 2008;57:1805–1813. doi: 10.2337/db07-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krishnapuram R, et al. Insulin receptor-independent upregulation of cellular glucose uptake. International Journal of Obesity. 2013;37:146. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McMurphy, T. B. et al. Hepatic Expression of Adenovirus 36 E4ORF1 Improves Glycemic Control and Promotes Glucose Metabolism via AKT Activation. Diabetes, db160876 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Mäkelä M, et al. Enteral virus infections in early childhood and an enhanced type 1 diabetes-associated antibody response to dietary insulin. Journal of autoimmunity. 2006;27:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dubuisson O, Day RS, Dhurandhar NV. Accurate identification of neutralizing antibodies to adenovirus Ad36,-a putative contributor of obesity in humans. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications. 2015;29:83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nam J, Na H, Atkinson R, Dhurandhar N. Genomic stability of adipogenic human adenovirus 36. International Journal of Obesity. 2014;38:321. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sang, Y. et al. Ileal transcriptome analysis in obese rats induced by high-fat diets and an adenoviral infection. International Journal of Obesity, 1 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Glass GV. Testing Homogeneity of Variances. American Educational Research Journal. 1966;3:187–190. doi: 10.3102/00028312003003187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.