Abstract

Background and Aims

The impact of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is unknown. We sought to characterize the clinical course of COVID-19 among patients with IBD and evaluate the association among demographics, clinical characteristics, and immunosuppressant treatments on COVID-19 outcomes.

Methods

Surveillance Epidemiology of Coronavirus Under Research Exclusion for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (SECURE-IBD) is a large, international registry created to monitor outcomes of patients with IBD with confirmed COVID-19. We calculated age-standardized mortality ratios and used multivariable logistic regression to identify factors associated with severe COVID-19, defined as intensive care unit admission, ventilator use, and/or death.

Results

525 cases from 33 countries were reported (median age 43 years, 53% men). Thirty-seven patients (7%) had severe COVID-19, 161 (31%) were hospitalized, and 16 patients died (3% case fatality rate). Standardized mortality ratios for patients with IBD were 1.8 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.9–2.6), 1.5 (95% CI, 0.7–2.2), and 1.7 (95% CI, 0.9–2.5) relative to data from China, Italy, and the United States, respectively. Risk factors for severe COVID-19 among patients with IBD included increasing age (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01–1.02), ≥2 comorbidities (aOR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1–7.8), systemic corticosteroids (aOR, 6.9; 95% CI, 2.3–20.5), and sulfasalazine or 5-aminosalicylate use (aOR, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.3–7.7). Tumor necrosis factor antagonist treatment was not associated with severe COVID-19 (aOR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.4–2.2).

Conclusions

Increasing age, comorbidities, and corticosteroids are associated with severe COVID-19 among patients with IBD, although a causal relationship cannot be definitively established. Notably, tumor necrosis factor antagonists do not appear to be associated with severe COVID-19.

Keywords: Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Crohn’s Disease, Ulcerative Colitis, COVID-19

Abbreviations used in this paper: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CD, Crohn’s disease; CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; ICU, intensive care unit; SMR, standardized mortality ratio; SECURE-IBD, Surveillance Epidemiology of Coronavirus Under Research Exclusion for Inflammatory Bowel Disease; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; UC, ulcerative colitis; 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylate

See Covering the Cover synopsis on page 407.

What You Need to Know.

Background and Context

The impact of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is unknown. We sought to characterize the clinical course of COVID-19 among IBD patients.

New Findings

Of 525 reported cases, 31% were hospitalized and 3% died. Risk factors for severe COVID-19 included increasing age, other comorbidities, systemic corticosteroids, and sulfasalazine/5-aminosalicylate use but not anti-TNF antagonist treatment.

Limitations

Possibility of reporting bias and unmeasured confounding.

Impact

Maintaining remission with steroid-sparing treatments is important in managing IBD patients through this pandemic. TNF antagonist therapy does not appear to be a risk factor for severe COVID-19.

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first reported in December 2019 and has rapidly spread throughout the world leading to an international pandemic.1 Although most cases of COVID-19 are mild, the disease can become severe and result in hospitalization, respiratory failure, or death with reported case fatality rates ranging from 2.3% to 7.2%.2 , 3 To date, the most frequently identified risk factors for severe COVID-19 have been age, cardiovascular disease, chronic lung conditions, obesity, and diabetes.2 , 4 In a recent report from the United States, 78% of patients requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission had at least 1 underlying comorbidity.4

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal tract affecting millions of people worldwide.5, 6, 7 Patients with IBD and related rheumatologic, dermatologic, and neurologic auto-inflammatory conditions frequently require treatment with immunosuppressant medications which can increase the risk of infection.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Corticosteroids, immunomodulators (thiopurines, methotrexate), biologics, and janus-kinase inhibitors, commonly used to treat chronic auto-inflammatory conditions, have been associated with higher rates of serious viral and bacterial infections including influenza and pneumonia.11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Yet, it is also possible that some forms of immune suppression may blunt the excessive immune response/cytokine storm characteristic of severe COVID-19 infection and consequently reduce mortality, as suggested by emerging case reports of anti-interleukin-6 therapy.16 , 17

Little is known about the impact of COVID-19 on patients with chronic auto-inflammatory diseases such as IBD, particularly those who require systemic immunosuppressant medications. An initial report of COVID-19 among 1099 patients in China included only 2 persons with immune deficiency.18 A subsequent report found that cancer patients had a higher risk of severe COVID-19, but this conclusion was based on only 16 patients.19 In Italy, Mazza et al20 reported a case of COVID-19 pneumonia leading to death in a patient with severe acute UC treated with systemic corticosteroids.

To provide better guidance to patients and their health care providers and to inform strategies for prevention of COVID-19 and medication management, more data are urgently needed regarding the impact of IBD and treatments on COVID-19 outcomes. In the present work, we report on the clinical course of COVID-19 and risk factors for adverse outcomes in a large cohort of patients with IBD collected through an international registry.

Materials and Methods

Case Identification and Data Collection

We created the Surveillance Epidemiology of Coronavirus Under Research Exclusion for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (SECURE-IBD) database to monitor outcomes of COVID-19 occurring in pediatric and adult patients with IBD. SECURE-IBD is an international, collaborative effort, endorsed and promoted by the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation (United States), the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation, the Pan American Crohn’s and Colitis Organization, the Asian Organization of Crohn’s & Colitis, and several regional/national organizations (Supplementary Table 1).

Physicians and other health care providers were encouraged to voluntarily report all cases of polymerase chain reaction–confirmed COVID-19 occurring in patients with IBD, regardless of severity. To foster international collaboration and promote transparency, we developed a project Web site (www.covidibd.org) to acknowledge the contributions of individual reporters and share crude, aggregate data along with an interactive Web-based map displaying the geographic location of reported cases (https://covidibd.org/map/).

We instructed health care providers to report cases after a minimum of 7 days from symptom onset and sufficient time had passed to observe the disease course through resolution of acute illness or death. In the event that a patient’s status changed after reporting or if there were concerns about data accuracy, we instructed reporters to re-report and contact the research team to remove their initial entry.

We utilized REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure, Web-based electronic data capture tool hosted at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to collect and manage study data. Health care providers recorded the following information: age, country of residence, state of residence (if applicable), year of COVID-19 diagnosis, name of center/practice/physician providing care, sex, race, ethnicity, height, weight, patient's diagnosis (CD, UC, or inflammatory bowel disease unclassified, IBD-U), disease activity (as defined by physician global assessment), medications at time of COVID-19 diagnosis, whether the patient was hospitalized, gastrointestinal symptoms related to COVID-19, COVID-19 treatments used, and whether the patient died of COVID-19 or complications related to COVID-19. For hospitalized patients, the name of hospital, length of stay, need for ICU, and need for a ventilator were additionally recorded.

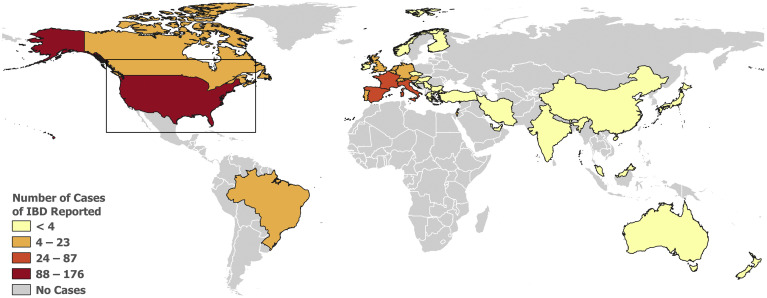

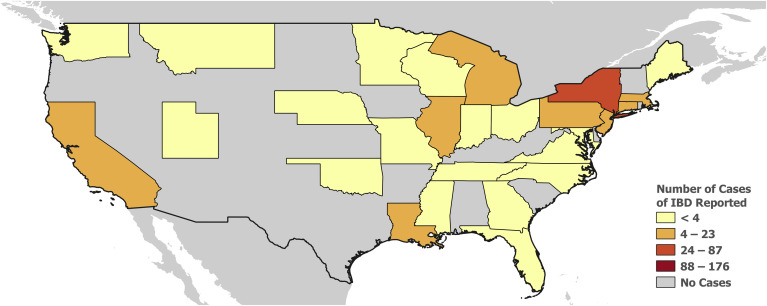

QGIS 3.4.4 (www.osgeo.org) was used to create a choropleth map of the number of reported cases of IBD stratified by 4 classes using Jenks Natural Breaks.21 ArcGIS Pro 2.4.1 and ArcGIS Online (www.esri.com/en-us/home) were used to create an interactive global map (https://covidibd.org/map/) that visualizes patients with IBD diagnosed with COVID-19, as well as their clinical course and characteristics.

The Pediatric IBD Porto group of the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition implemented a parallel reporting system at 102 affiliated sites. Recently reported preliminary data from this consortium are included in the analyses described as follows.22

Quality Control

We removed all known duplicate or erroneous reports. We identified additional potential duplicate records based on matching age, sex, IBD disease type, country, and state (United States only), and reviewed these manually. Reports from nonvalid e-mail addresses were flagged as potential errors and we performed a Google search of reporters and practice locations to confirm legitimacy of reports.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the basic demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. We summarized continuous variables using means and standard deviations. We expressed categorical variables as proportions. Comorbidities were collapsed into the following categories: cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, lung disease, kidney disease, liver disease, and cancer.

We analyzed a variety of COVID-19 outcomes, including outpatient care only, hospitalization, ICU or ventilator requirement, and death from COVID-19 or related complications. Crude data are provided for the overall study population, and stratified by a variety of demographic and clinical characteristics. To understand the impact of IBD on case fatality, we computed expected and observed deaths and age-standardized mortality ratios (SMR) using published age-stratified COVID-19 case fatality rates from China and Italy2 , 23 and publically available data from the United States.24 , 25

Multivariable logistic regression estimated the independent effects of age, sex, disease (CD vs UC/IBD-U), disease activity, smoking, body mass index ≥30, and number of comorbidities (0, 1, ≥2) on the primary outcome of severe COVID-19, defined as a composite of ICU admission, ventilator use, and/or death, consistent with existing COVID-19 literature.18 Models also included tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonist use (versus not) and sulfasalazine/5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA) use (vs not) as these were the 2 most commonly reported medication classes and systemic corticosteroid use (vs not) based on increased risk of infectious complications based on prior literature and crude data. A secondary outcome was the composite of any hospitalization and/or death. We also analyzed death as a separate endpoint. We reported adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each demographic or disease characteristic.

We also performed a series of exploratory sub-analyses. We compared TNF antagonist monotherapy versus combination therapy with immunomodulators (6-mercaptopurine, azathioprine, or methotrexate), controlling for the above demographic and clinical factors as well as the use of systemic corticosteroids and 5-ASA/sulfasalazine. In addition, given the surprising association between 5-ASA/sulfasalazine use and more severe COVID outcomes in our main analyses, we performed a sub-analysis to directly compare the effects of TNF antagonists vs 5-ASA/ sulfasalazine, controlling for the preceding factors as well as use of immunomodulators. The primary outcome of these exploratory analyses was the composite of any hospitalization and/or death. The number of events was too sparse to evaluate other outcomes. All data were prepared and analyzed using SAS v 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Two-sided P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

Each SECURE-IBD survey item met criteria for de-identified data, in accordance with the HIPAA Safe Harbor De-Identification standards. The UNC-Chapel Hill Office for Human Research Ethics has determined that the storage and analysis of de-identified data for this project does not constitute human subjects research as defined under federal regulations (45 CFR 46.102 and 21 CFR 56.102) and does not require institutional review board approval.

Results

At the time of this writing, a total of 525 cases were reported to the SECURE-IBD database from 33 different countries and 28 states within the United States (Figures 1 and 2 ; Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Demographic, clinical, and IBD treatment related characteristics are summarized in Table 1 . The median age was 41 years, with a range from 5 to ≥ 90 years, and there was a slight predominance of male individuals (52.6%). Most cases were reported in white individuals (84.2%). Ethnicity was reported as Hispanic/Latino in 14.3% of cases (Table 1).

Figure 1.

World map depicting cases of COVID-19 among patients with IBD reported to the SECURE-IBD database. Interactive web-based map: http://covidibd.org/map/

Figure 2.

US map depicting cases of COVID-19 among patients with IBD reported to the SECURE-IBD database. Interactive web-based map: http://covidibd.org/map/

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of SECURE-IBD Cohort (Total N = 525)

| Characteristica,b | |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 42.9 (18.2) |

| Sex, n (%)c | |

| Male | 276 (52.6) |

| Female | 243 (46.3) |

| Missing | 6 (1.1) |

| Race, n (%)d | |

| Reported at least selected one race (including other/unknown) | 523 (99.6) |

| White | 442 (84.2) |

| Black or African American | 26 (5.0) |

| American Indian/Native Alaskan | 1 (0.2) |

| Asian | 14 (2.7) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 47 (9.0) |

| Unknown | 13 (2.5) |

| Hispanic/Latino, n (%) | |

| Yes | 75 (14.3) |

| No | 350 (66.7) |

| Unknown | 45 (8.6) |

| Missing | 55 (10.5) |

| Disease type, n (%) | |

| CD | 312 (59.4) |

| UC | 203 (38.7) |

| IBD-unspecified | 7 (1.3) |

| Missing | 3 (0.6) |

| IBD disease activity, n (%)e | |

| Remission | 309 (58.9) |

| Mild | 100 (19.0) |

| Moderate | 76 (14.5) |

| Severe | 24 (4.6) |

| Unknown | 4 (0.8) |

| Missing | 12 (2.3) |

| IBD medication, n (%)f | |

| Any medication | 494 (94.1) |

| Sulfasalazine/mesalamine | 117 (22.3) |

| Budesonide | 18 (3.4) |

| Oral/parenteral steroids | 37 (7.0) |

| 6MP/azathioprine monotherapyg | 53 (10.1) |

| Methotrexate monotherapyg | 5 (1.0) |

| Anti-TNF without 6MP/AZA/MTX | 176 (33.5) |

| Anti-TNF + 6MP/AZA/MTX | 52 (9.9) |

| Anti-integrin | 50 (9.5) |

| IL-12/23 inhibitor | 55 (10.5) |

| JAK inhibitor | 8 (1.5) |

| Other IBD medication | 22 (4.2) |

| Comorbid conditions, n (%) | |

| Any condition | 192 (36.6) |

| Cardiovascular disease (eg, CAD, heart failure, arrhythmia) | 38 (7.2) |

| Diabetes | 29 (5.5) |

| Lung disease (eg, asthma, COPD) | 44 (8.4) |

| Hypertension | 63 (12.0) |

| Cancer | 10 (1.9) |

| History of stroke | 4 (0.8) |

| Chronic renal disease (eg, CKD) | 10 (1.9) |

| Chronic liver disease (eg, PSC, NAFLD, cirrhosis) | 26 (5.0) |

| Other | 53 (10.1) |

| Current smokerh | 23 (4.4) |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms, n (%) | |

| Any increase in baseline IBD symptoms | 161 (30.7) |

| Abdominal pain | 44 (8.4) |

| Diarrhea | 134 (25.5) |

| Nausea | 30 (5.7) |

| Vomiting | 17 (3.2) |

| Other | 13 (2.5) |

| Medications and/or investigational therapies used in COVID-19 treatment, n (%) | |

| Any medication | 146 (27.8) |

| Remdesivir | 2 (0.4) |

| Chloroquine | 14 (2.7) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 98 (18.7) |

| Oseltamivir | 6 (1.1) |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 28 (5.3) |

| Tocilizumab | 5 (1.0) |

| Corticosteroidsi | 12 (2.3) |

| Other | 67 (12.8) |

| No medications and/or investigational therapies were used | 321 (61.1) |

| Unknown | 16 (3.0) |

| Died of COVID-10 or other complications caused by or contributed to by COVID-19, n (%) | |

| Yes | 16 (3.0) |

| No | 498 (94.9) |

| Unknown | 8 (1.5) |

| Missing | 3 (0.6) |

| Emergency room, n (%) | |

| Yes | 199 (37.9) |

| No | 312 (59.4) |

| Unknown | 9 (1.7) |

| Missing | 5 (1.0) |

| Hospitalized, n (%) | |

| Yes | 161 (30.7) |

| No | 363 (69.1) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) |

| Hospital length of stay in days, mean (SD) | 8.5 (6.9) |

| ICU, n (%) | 24 (4.6) |

| Ventilator, n (%) | 21 (4.0) |

| ICU and/or ventilator use, n (%) | 27 (5.1) |

AZA, azathioprine; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GI, gastrointestinal; MTX, methotrexate; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; SECURE-IBD, Surveillance Epidemiology of Coronavirus Under Research Exclusion for Inflammatory Bowel Disease; 6MP, 6-mercaptopurine.

Unless otherwise specified, percentages do not include missing values or “unknown.” For all characteristics, less than 4% of data was missing and unknown, respectively, for each category.

Percentages and n from each subcategory may not add up to the exact number of total reported cases due to missing values and/or non-mutually exclusive variables.

No individuals identifying as other sex were reported to the database.

Individual cases could belong to ≥1 race, so percentages may sum to >100%.

By physician global assessment (PGA) at time of COVID-19 infection

At time of COVID-19 infection. Medication categories are not mutually exclusive unless otherwise noted.

Monotherapy indicates no concomitant TNF antagonist, anti-integrin, anti-IL12/23, or JAK inhibitor

Current smoker defined as current tobacco and/or e-cigarette use

Started specifically for COVID-19 treatment, not for IBD care

Most patients had CD (59.4%), and IBD disease activity by physician global assessment was classified as remission in 58.9% of cases. The most common class of IBD treatment was TNF antagonist therapy (43.4% overall, 33.5% monotherapy and 9.9% combination therapy with azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, or methotrexate). Use of other medications is described in Table 1. Most patients (63.4%) had no comorbidities other than IBD; 21.0% had 1, 6.7% had 2, and 5.5% had 3 or more. Four percent of the cohort reported using tobacco and/or electronic cigarettes (Table 1).

Crude outcome data are summarized in Table 2 for the overall study population, stratified by a variety of demographic and clinical characteristics. Overall, 161 patients required hospitalization (31%), 24 stayed in an ICU (5%), and 21 used a ventilator (4%). The primary outcome (ICU/ventilator/death) was observed in 37 (7%) of 525 patients. Of these, 20 (20%) of 101 occurred in patients ≥60 years of age vs 0 of 29 pediatric cases (< 20 years). Only 3 pediatric patients (10%) required hospitalization; none required ICU or ventilator support. Patients with more comorbidities also experienced a higher proportion of adverse outcomes. Nine (24%) of 37 patients on systemic corticosteroids experienced the primary endpoint. Additional outcome data, stratified by medication use, are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Outcomes by Demographic, Clinical, and Treatment Characteristics of SECURE-IBD cohort

| Characteristica,b | Total N | Outpatient only, n (%) | Hospitalized, n (%) | ICU, n (%) | Ventilator, n (%) | Death, n (%) | ICU/Ventilator/death, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 525 | 363 (69) | 161 (31) | 24 (5) | 21 (4) | 16 (3) | 37 (7) |

| Age, y | |||||||

| 0–9 | 3 | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 10–19 | 26 | 23 (88) | 3 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 20–29 | 116 | 93 (80) | 23 (20) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

| 30–39 | 108 | 87 (81) | 20 (19) | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) |

| 40–49 | 95 | 64 (67) | 31 (33) | 4 (4) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 5 (5) |

| 50–59 | 74 | 45 (61) | 29 (39) | 3 (4) | 5 (7) | 2 (3) | 6 (8) |

| 60–69 | 54 | 30 (56) | 24 (44) | 10 (19) | 9 (17) | 3 (6) | 11 (20) |

| 70–79 | 24 | 7 (29) | 17 (71) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 3 (13) |

| >=80 | 23 | 9 (39) | 14 (61) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (26) | 6 (26) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 276 | 183 (66) | 93 (34) | 12 (4) | 9 (3) | 11 (4) | 21 (8) |

| Female | 243 | 175 (72) | 67 (28) | 12 (5) | 12 (5) | 5 (2) | 16 (7) |

| Disease type | |||||||

| CD | 312 | 228 (73) | 83 (27) | 12 (4) | 9 (3) | 5 (2) | 16 (5) |

| UC/unspecified | 210 | 133 (63) | 77 (37) | 12 (6) | 12 (6) | 11 (5) | 21 (10) |

| IBD disease activityc | |||||||

| Remission | 309 | 232 (75) | 76 (25) | 12 (4) | 14 (5) | 8 (3) | 19 (6) |

| Mild | 100 | 70 (70) | 30 (30) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | 5 (5) |

| Moderate/Severe | 100 | 52 (52) | 48 (48) | 9 (9) | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | 12 (12) |

| Unknown | 16 | 9 (56) | 7 (44) | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | 1 (6) |

| Smoking | |||||||

| Current smoker | 23 | 12 (52) | 11 (48) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

| Non-smoker | 502 | 351 (70) | 150 (30) | 24 (5) | 21 (4) | 15 (3) | 36 (7) |

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| 0 | 351 | 272 (77) | 79 (23) | 11 (3) | 8 (2) | 4 (1) | 13 (4) |

| 1 | 110 | 74 (67) | 35 (32) | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | 8 (7) |

| 2 | 35 | 10 (29) | 25 (71) | 4 (11) | 5 (14) | 3 (9) | 7 (20) |

| 3+ | 29 | 7 (24) | 22 (76) | 5 (17) | 4 (14) | 5 (17) | 9 (31) |

| IBD medicationd | |||||||

| Sulfasalazine/mesalamine | 117 | 60 (51) | 57 (49) | 12 (10) | 12 (10) | 9 (8) | 20 (17) |

| Budesonide | 18 | 9 (50) | 9 (50) | 3 (17) | 3 (17) | 1 (6) | 3 (17) |

| Oral/parenteral steroids | 37 | 11 (30) | 26 (70) | 6 (16) | 5 (14) | 4 (11) | 9 (24) |

| 6MP/azathioprine monotherapye | 53 | 29 (55) | 24 (45) | 3 (6) | 3 (6) | 1 (2) | 3 (6) |

| Methotrexate monotherapye | 5 | 2 (40) | 3 (60) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Anti-TNF without 6MP/AZA/MTX | 176 | 150 (85) | 25 (14) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 4 (2) |

| Anti-TNF + 6MP/AZA/MTX | 52 | 32 (62) | 20 (38) | 4 (8) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 5 (10) |

| Anti-integrin | 50 | 34 (68) | 16 (32) | 2 (4) | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 3 (6) |

| IL-12/23 inhibitor | 55 | 51 (93) | 4 (7) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| JAK inhibitor | 8 | 7 (88) | 1 (13) | 1 (13) | 1 (13) | 1 (13) | 1 (13) |

| Other IBD medication | 22 | 13 (59) | 9 (41) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

AZA, azathioprine; IL, interleukin; MTX, methotrexate; 6MP, 6-mercaptopurine.

Unless otherwise specified, percentages do not include missing values or “unknown.” For all characteristics, less than 4% of data was missing and unknown, respectively, for each category.

Percentages and n from each subcategory may not add up to the exact number of total reported cases due to missing values and/or non-mutually exclusive variables.

By physician global assessment (PGA) at time of COVID-19 infection

At time of COVID-19 infection. Medication categories are not mutually exclusive unless otherwise noted.

Monotherapy indicates no concomitant TNF antagonist, anti-integrin, anti-IL12/23, or JAK inhibitor

Sixteen deaths (3% of reported cases) are summarized in Supplementary Table 4. Eight deaths (50%) occurred in patients ≥70 years of age. No deaths occurred in patients <30 years of age. Most deaths had comorbidities, including 8 with cardiovascular disease. The age-standardized SMRs for the SECURE-IBD population relative to China, Italy, and the United States were 1.8 (95% CI, 0.9–2.6), 1.5 (95% CI, 0.7–2.2), and 1.7 (95% CI, 0.9–2.5), respectively (Tables 3 and 4 ).

Table 3.

Observed and Expected Deaths by Age and SMRs for SECURE-IBD Cohort vs China and Italya (IBD Overall)

| Age (y) | SECURE-IBD (n) | SECURE-IBD observed number of deaths | SECURE-IBD fatality rate (%) | China case fatality rate (%) | China expected number of deaths | Italy case fatality rate (%) | Italy expected number of deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–9 | 3 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10–19 | 26 | 0 | 0.0% | 0.2 | 0.052 | 0 | 0 |

| 20–29 | 116 | 0 | 0.0% | 0.2 | 0.232 | 0 | 0 |

| 30–39 | 108 | 1 | 0.9% | 0.2 | 0.216 | 0.3 | 0.324 |

| 40–49 | 95 | 2 | 2.1% | 0.4 | 0.38 | 0.4 | 0.38 |

| 50–59 | 74 | 2 | 2.7% | 1.3 | 0.962 | 1 | 0.74 |

| 60–69 | 54 | 3 | 5.6% | 3.6 | 1.944 | 3.5 | 1.89 |

| 70–79 | 24 | 2 | 8.3% | 8 | 1.92 | 12.8 | 3.072 |

| >=80 | 23 | 6 | 26.1% | 14.8 | 3.404 | 20.2 | 4.646 |

| All | 523 | 16 | 2.3 | 9.11 | 7.2 | 11.052 | |

| SMR (96% CI) | 1.76 (0.90–2.62) | 1.45 (0.74–2.16) |

Based on references 23 and 2, respectively.

Table 4.

Observed and Expected Deaths by Age and SMRs for SECURE-IBD Cohort vs United Statesa (IBD Overall)

| Age (y) | SECURE-IBD (n) | SECURE-IBD observed number of deaths | United States case fatality rate (%) | United States expected number of deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–14 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15–44 | 295 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.052 |

| 45–64 | 149 | 5 | 0.2 | 0.232 |

| 65+ | 69 | 10 | 0.2 | 0.216 |

| All | 523 | 16 | 0.4 | 0.38 |

| SMR (95% CI) | 1.66 (0.85–2.47) |

Based on references 24 and 25.

On multivariable analysis, increasing age (aOR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01–1.06), ≥2 comorbidities (aOR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1–7.8), systemic corticosteroids (aOR, 6.9; 95% CI, 2.3–20.5), and 5-ASA/sulfasalazine use (aOR, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.3–7.7) were positively associated with the primary endpoint after controlling for all other covariates listed in Table 5 . No significant association was seen between TNF antagonist use and the primary endpoint (aOR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.4–2.2). Similar associations were observed for our secondary outcomes, although TNF antagonist use was inversely associated with the outcome of hospitalization or death while only age and systemic corticosteroid use were positively associated with the outcome of death.

Table 5.

Multivariable regression for primary and secondary outcomes from SECURE-IBD cohort

| Variable (Referent group)a | ICU/Vent/Death Odds Ratio (95% CI) (n = 517) |

P | Hospitalization or death Odds Ratio (95% CI) (n =517) | P | Death Odds Ratio (95% CI) (n = 513) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.04 (1.01–1.06) | .002 | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | <.001 | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | <.001 |

| Male (Femaleb) | 1.20 (0.55–2.60) | .65 | 1.38 (0.89–2.15) | .15 | 2.78 (0.76–10.14) | .12 |

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| Crohn’s disease (ulcerative colitis/IBD unspecified) | 0.76 (0.31–1.85) | .54 | 0.84 (0.51–1.38) | .49 | 1.64 (0.42–6.43) | .48 |

| Disease severityc (remission) | ||||||

| Active disease | 1.14 (0.49–2.66) | .76 | 1.96 (1.23–3.11) | .005 | 0.97 (0.26–3.62) | .96 |

| Systemic corticosteroid (none) | 6.87 (2.30–20.51) | <.001 | 6.46 (2.74–15.23) | <.001 | 11.62 (2.09–64.74) | .005 |

| TNF antagonist (none) | 0.90 (0.37–2.17) | .81 | 0.60 (0.38–0.96) | .03 | 0.99 (0.23–4.23) | .99 |

| Current smoker | 0.55 (0.06–4.94) | .59 | 2.38 (0.92–6.16) | .07 | 1.47 (0.12–17.53) | .76 |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 2.00 (0.72–5.51) | .18 | 1.18 (0.61–2.31) | .63 | 1.58 (0.28–8.80) | .60 |

| Comorbidities (none) | ||||||

| 1 | 1.22 (0.45–3.26) | .70 | 1.29 (0.76–2.20) | .34 | 1.64 (0.35–7.67) | .53 |

| ≥2 | 2.87 (1.05–7.85) | .04 | 4.42 (2.16–9.06) | <.001 | 2.51 (0.56–11.24) | .23 |

| 5-ASA/sulfasalazine (none) | 3.14 (1.28–7.71) | .01 | 1.77 (1.00–3.12) | .05 | 1.71 (0.46–6.38) | .43 |

We adjusted each odds ratio for all other variables listed in this table.

Other sex excluded from analysis due to low numbers

By physician global assessment (PGA) at time of COVID-19 infection

In our exploratory analyses, we found that TNF antagonist combination therapy, compared with monotherapy, was positively associated with the outcome of hospitalization or death (aOR, 5.0; 95% CI, 2.0–12.3), after adjusting for clinical and demographic variables and use of systemic corticosteroids and 5-ASA/sulfasalazine. Compared with TNF antagonists, 5-ASA/sulfasalazine was positively associated with the outcome of hospitalization or death (aOR, 3.8; 95% CI, 1.7–8.5).

Discussion

We report the development of an international, physician-driven, reporting system to study the natural history of COVID-19 in pediatric and adult patients with IBD. Given the expanding knowledge that persons with comorbidities are disproportionately affected by COVID-19, there is an urgent need to evaluate this emerging infection on patients with systemic, auto-inflammatory conditions such as IBD, many of whom are treated with immunosuppressive medications. To date, no large, international reports describing the clinical course of COVID-19 in these patient populations have been published. Based on results from 525 patients with IBD from 33 countries, we observed an overall case fatality rate of 3% with 7% of reported cases experiencing a composite outcome of ICU admission, ventilator support, and/or death. Strong risk factors for adverse COVID-19 outcomes were older age, number of comorbidities, and use of systemic corticosteroids. Unexpectedly, use of 5-ASA/sulfasalazine was also associated with more severe COVID-19. Reassuringly, TNF antagonist biologic therapy was not an independent risk factor for more severe COVID-19.

In this international IBD population, we observed an age-standardized mortality ratio of approximately 1.5 to 1.8, as compared with the general populations of China, Italy, and the United States with CIs crossing the null. We note no deaths occurred in the 29 reported cases occurring in patients <20 years of age, extending the findings of an earlier case series suggesting a milder course of COVID-19 in pediatric patients.22 In contrast, 50% of deaths occurred in patients older than 70 years and 50% of patients who died had cardiovascular comorbidities.

The strong positive association between systemic corticosteroid use and our primary and secondary outcomes is consistent with extensive prior literature in IBD and other auto-inflammatory conditions describing the infectious complications of corticosteroid use as well as more recent data indicating that corticosteroids are not beneficial, and may even be harmful, in the treatment of coronavirus and similar viruses (eg, Middle East respiratory syndrome, severe acute respiratory syndrome).26 Forty-three percent of our cohort was exposed to TNF antagonist medications. In the adjusted analysis of our primary outcome, we observed no association between TNF antagonist use and severe COVID-19. As TNF antagonists are the most commonly prescribed biologic therapy for patients with IBD, these initial findings should be reassuring to the large number of patients receiving TNF antagonist therapy and support their continued use during this current pandemic. In our exploratory subgroup analysis, we observed a higher risk of hospitalization and/or death with TNF antagonist combination therapy vs monotherapy, consistent with prior studies of other infectious complications.12 Given the overall effect estimate of TNF antagonists (combination and monotherapy combined) in our primary model was 0.9, one can hypothesize that TNF antagonist monotherapy may have a protective effect against severe COVID-19, as suggested in a recent commentary.27

We observed a higher risk of our primary outcome in patients exposed to 5-ASA/sulfasalazine. This finding persisted after controlling for age, comorbidities, IBD disease characteristics, corticosteroid use, and other factors. Furthermore, in a direct comparison, we observed that 5-ASA/sulfasalazine–treated patients fared worse than those treated with TNF inhibitors. Although we cannot exclude unmeasured confounding, further exploration of biological mechanisms is warranted. Conversely, although the number of reported cases exposed to other IBD treatments is currently small, it is worth noting that 51 (93%) of 55 patients treated with anti-interleukin12/23 required outpatient care only and none died.

The strengths of this study include the robust, worldwide collaboration that enabled us to assemble clinical data on a large, geographically diverse sample of pediatric and adult patients with IBD and rapidly define the course of COVID-19 in this population. The reporting directly by physicians or their trained medical staff strengthens the validity of these data. Although our study sample is diverse in terms of age, geography, race, and other factors, we acknowledge the possibility of reporting bias. Reported cases may overrepresent patients with more severe COVID-19 who come to the attention of their provider and patients in areas with readily available COVID-19 testing. Conversely, our sample may underrepresent those severely ill patients who may be hospitalized at an outside hospital or die without their physician’s awareness. The registry includes only confirmed cases of COVID-19 in accordance with other reporting initiatives from national authorities and the World Health Organization,2 , 4 , 18 although we recognize many patients with suspected infection are never tested. Although we adjusted for many factors, such as age, comorbidities, and IBD disease type and severity, we acknowledge the possibility of unmeasured confounding. Additional research is needed to further evaluate causality between the use of corticosteroids and other medications and COVID-19 outcomes. Finally, we computed age-SMRs using case fatality rates reported from China, Italy, and the United States, yet our study sample arose from 31 different countries. Given the profound effects of age on COVID-19–related mortality, we believe it was useful to standardize to existing data. That our SMR estimates were roughly equivalent when standardizing to Chinese, Italian, or US data suggest the overall validity of this approach.

In summary, older age, increased number of comorbidities, and systemic corticosteroid use among patients with IBD are strong risk factors for adverse COVID-19 outcomes. Maintaining remission with steroid-sparing treatments will be important in managing patients with IBD through this pandemic. It appears that TNF antagonist therapy is not associated with severe COVID-19, providing reassurance that patients can continue TNF antagonist therapy.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the physicians and other health care providers worldwide who have reported cases to the SECURE-IBD database and the organizations who supported or promoted the SECURE-IBD database. (Reporter names available at www.covidibd.org/reporter-acknowledgment/. See Supplementary Table 4 for organization names.)

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Erica June Brenner, MD (Conceptualization: Equal; Formal analysis: Equal; Investigation: Equal; Methodology: Equal; Writing – original draft: Equal). Ryan C. Ungaro, MD, MS (Conceptualization: Equal; Formal analysis: Equal; Funding acquisition: Equal; Investigation: Equal; Methodology: Equal; Writing – original draft: Equal). Richard B. Gearry, MBChB, PhD, FRACP (Formal analysis: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal). Gilaad G. Kaplan, MD, MPH, FRCPC (Formal analysis: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal). Michele Kissous-Hunt, PA-C, DFAAPA (Formal analysis: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal). James D. Lewis, MD, MSCE (Formal analysis: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal). Siew C. Ng, MD, PhD (Formal analysis: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal). Jean-Francois Rahier, MD, PhD (Formal analysis: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal). Walter Reinisch, MD (Formal analysis: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal). Frank M. Ruemmele, MD, PhD (Formal analysis: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal). Flavio Steinwurz, MD, MSc, MACG (Formal analysis: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal). Fox E Underwood, MSc (Software: Equal; Visualization: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal). Xian Zhang, PhD (Data curation: Lead; Formal analysis: Equal; Methodology: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal). Jean-Frederic Colombel, MD (Conceptualization: Equal; Formal analysis: Equal; Investigation: Equal; Supervision: Equal; Writing – original draft: Equal). Michael D. Kappelman, MD, MPH (Conceptualization: Equal; Formal analysis: Equal; Funding acquisition: Lead; Investigation: Equal; Methodology: Equal; Supervision: Equal; Writing – original draft: Equal).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest These authors disclose the following: Ryan C. Ungaro: Supported by an NIH K23 Career Development Award (K23KD111995–01A1); has served as an advisory board member or consultant for Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, and Takeda; research support from AbbVie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Pfizer. Richard B. Gearry: Speaker fees and Scientific Advisory Boards for AbbVie and Janssen. Gilaad G. Kaplan: Received honoraria for speaking or consultancy from AbbVie, Janssen, Pfizer, and Takeda. He has received research support from Ferring, Janssen, Abbvie, GlaxoSmith Kline, Merck, and Shire. He shares ownership of a patent: TREATMENT OF INFLAMMATORY DISORDERS, AUTOIMMUNE DISEASE, AND PBC. UTI Limited Partnership, assignee. Patent WO2019046959A1. PCT/CA2018/051098. 7 Sept. 2018. Michele Kissous-Hunt: Speaker/consultant for AbbVie, Janssesn, Takeda. James Lewis: Personal fees from Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc, grants, personal fees and other from Takeda Pharmaceuticals, personal fees and nonfinancial support from AbbVie, grants and personal fees from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Eli Lilly and Company, personal fees from Samsung Bioepis, personal fees from UCB, personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, grants and personal fees from Nestle Health Science, personal fees from Bridge Biotherapeutics, personal fees from Celgene, personal fees from Merck, personal fees and other from Pfizer, personal fees from Gilead, personal fees from Arena Parmaceuticals, personal fees from Protagonist Therapeutics, outside the submitted work. Siew C. Ng: Received honoraria for speaking or consultancy from AbbVie, Janssen, Ferring, Tillotts and Takeda. She has received research support from Ferring and AbbVie. Jean-Francois Rahier: Received lecture fees from AbbVie, MSD, Takeda, Pfizer, Ferring, and Falk, consulting fees from AbbVie, Takeda, Hospira, Mundipharma, MSD, Pfizer, GlaxoSK, and Amgen, and research support from Takeda and AbbVie. Walter Reinisch: Served as a speaker for Abbott Laboratories, AbbVie, Aesca, Aptalis, Astellas, Centocor, Celltrion, Danone Austria, Elan, Falk Pharma GmbH, Ferring, Immundiagnostik, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, MSD, Otsuka, PDL, Pharmacosmos, PLS Education, Schering-Plough, Shire, Takeda, Therakos, Vifor, Yakult. He has been a consultant for Abbott Laboratories, Abbvie, Aesca, Algernon, Amgen, AM Pharma, AMT, AOP Orphan, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Avaxia, Roland Berger GmbH, Bioclinica, Biogen IDEC, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cellerix, Chemocentryx, Celgene, Centocor, Celltrion, Covance, Danone Austria, DSM, Elan, Eli Lilly, Ernest & Young, Falk Pharma GmbH, Ferring, Galapagos, Genentech, Gilead, Grünenthal, ICON, Index Pharma, Inova, Intrinsic Imaging, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Pharma, Lipid Therapeutics, LivaNova, Mallinckrodt, Medahead, MedImmune, Millenium, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, MSD, Nash Pharmaceuticals, Nestle, Nippon Kayaku, Novartis, Ocera, OMass, Otsuka, Parexel, PDL, Periconsulting, Pharmacosmos, Philip Morris Institute, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Prometheus, Protagonist, Provention, Robarts Clinical Trial, Sandoz, Schering-Plough, Second Genome, Seres Therapeutics, Setpointmedical, Sigmoid, Sublimity, Takeda, Therakos, Theravance, Tigenix, UCB, Vifor, Zealand, Zyngenia, and 4SC. He has been an advisory board member for Abbott Laboratories, AbbVie, Aesca, Amgen, AM Pharma, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Avaxia, Biogen IDEC, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cellerix, Chemocentryx, Celgene, Centocor, Celltrion, Danone Austria, DSM, Elan, Ferring, Galapagos, Genentech, Grünenthal, Inova, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Pharma, Lipid Therapeutics, MedImmune, Millenium, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, MSD, Nestle, Novartis, Ocera, Otsuka, PDL, Pharmacosmos, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Prometheus, Sandoz, Schering-Plough, Second Genome, Setpointmedical, Takeda, Therakos, Tigenix, UCB, Zealand, Zyngenia, and 4SC. He has received research funding from Abbott Laboratories, Abbvie, Aesca, Centocor, Falk Pharma GmbH, Immundiagnsotik, and MSD. Frank Ruemmele: Received consultation fee, research grant, or honorarium from Janssen, Pfizer, AbbVie, Takeda, Celgene, Nestlé Health Science, Nestlé Nutrition Institute. Flavio Steinwurz: Speaker and consultant for AbbVie, Eurofarma, Ferring, Janssen, Pfizer, Sanofi, Takeda, and UCB. Jean-Frederic Colombel: Research grants from AbbVie, Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Takeda; receiving payment for lectures from AbbVie, Amgen, Allergan, Inc. Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Shire, and Takeda; receiving consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celgene Corporation, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Enterome, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Landos, Ipsen, Medimmune, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Shire, Takeda, Tigenix, Viela bio; and hold stock options in Intestinal Biotech Development, and Genfit. Michael D. Kappelman: Consulted for AbbVie, Janssen, and Takeda, is a shareholder in Johnson & Johnson, and has received research support from AbbVie and Janssen. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This work was funded by CTSA grant number UL1TR002489 and K23KD111995–01A1 (to Ryan C. Ungaro). The study sponsor (National Institutes of Health) had no role in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.032.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1.

Acknowledgement of Additional Organizations That Supported or Promoted the SECURE-IBD database

| Professional organization |

| Agrupación Chilena de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (ACTECCU) |

| American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) |

| American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) |

| Asia-Pacific Association of Gastroenterology (APAGE) |

| BRICS IBD Consortium |

| Canadian Association of Gastroenterology |

| Crohn’s and Colitis Australia (CCA) |

| Crohn’s and Colitis Canada (CCC) |

| Crohn’s and Colitis India (CCI) |

| Crohn’s and Colitis New Zealand (CCNZ) |

| Grupo Argentino de Estudio de Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa |

| Grupo de Estudio de Crohn y Colitis Colombiano |

| Grupo de Estudos de Doenca Inflamatória Intestinal do Brasil (GEDIIB) |

| Grupo uruguayo de trabajo en enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (GUTEII) |

| Grupo Venezolano de Trabajo en Enfermedad Inflamatoria Intestinal |

| Hong Kong IBD Society (HKIBS) |

| Improve Care Now (ICN) |

| Indian Society of Gastroenterology |

| Japanese IBD Society |

| Korean Society for the Study of Intestinal Diseases |

| Malaysia Society of Gastroenterology |

| National Taiwan GI society |

| Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease Network (PIBD-NET) |

| Taiwan IBD society |

| The Gastroenterological Society of Australia (GESA) |

| The New Zealand Society of Gastroenterology (NZSG) |

| United European Gastroenterology (UEG) |

Supplementary Table 2.

Number of Cases Reported to the SECURE-IBD Database by Country

| Country | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| Australia | 3 |

| Austria | 8 |

| Bahrain | 1 |

| Belgium | 19 |

| Brazil | 7 |

| Bulgaria | 1 |

| Canada | 10 |

| China | 1 |

| Croatia | 1 |

| Czech Republic | 4 |

| Finland | 1 |

| France | 52 |

| Germany | 10 |

| Greece | 2 |

| Hungary | 1 |

| India | 1 |

| Iran, Islamic Republic of | 3 |

| Ireland | 4 |

| Israel | 11 |

| Italy | 39 |

| Japan | 1 |

| Malaysia | 1 |

| Netherlands | 17 |

| New Zealand | 1 |

| Norway | 2 |

| Portugal | 8 |

| Qatar | 2 |

| Serbia | 1 |

| Spain | 88 |

| Switzerland | 16 |

| Turkey | 4 |

| United Arab Emirates | 1 |

Supplementary Table 3.

Number of Cases Reported to the SECURE-IBD Database by State

| State | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| California | 9 |

| Connecticut | 7 |

| District of Columbia | 2 |

| Florida | 4 |

| Georgia | 2 |

| Illinois | 13 |

| Indiana | 2 |

| Louisiana | 8 |

| Maine | 2 |

| Maryland | 2 |

| Massachusetts | 7 |

| Michigan | 5 |

| Minnesota | 1 |

| Mississippi | 2 |

| Missouri | 4 |

| Montana | 1 |

| Nebraska | 1 |

| New Jersey | 12 |

| New York | 71 |

| North Carolina | 2 |

| Ohio | 1 |

| Oklahoma | 1 |

| Pennsylvania | 8 |

| Tennessee | 2 |

| Utah | 1 |

| Virginia | 1 |

| Washington | 2 |

| Wisconsin | 3 |

Supplementary Table 4.

Description of Deaths Reported to SECURE-IBD Cohorta

| Age group, y | Sex | Diagnosis | Disease activity | Medications | Comorbidities | Hospital stay? | ICU? | Ventilator use? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >=80 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Mild | Mesalamine | Cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer |

Yes | No | No |

| >=80 | Male | Crohn's disease | Remission | Adalimumab | Cardiovascular disease | No | Unknown | Unknown |

| 40-49 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Severe | Prednisone or prednisolone, JAK inhibitor |

None reported | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 70-79 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Remission | Mesalamine | Cardiovascular disease, Diabetes, COPD, Hypertension, Cancer, Chronic liver disease |

Yes | No | No |

| 50-59 | Male | Crohn's disease | Remission | Adalimumab, Methotrexate |

None reported | Yes | No | No |

| >=80 | Male | Crohn's disease | Mild | None reported | Cardiovascular disease, Hypertension, Chronic renal disease |

Yes | No | No |

| 30-39 | Female | Crohn's disease | Mild | Adalimumab, Azathioprine, Prednisone or prednisolone |

Familial Mediterranean fever, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis |

Yes | Yes | Yes |

| >=80 | Female | Ulcerative colitis | Remission | Mesalamine | Cardiovascular disease, epilepsy, recent orthopedic surgery |

Yes | No | No |

| >=80 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Remission | Mesalamine | Cardiovascular disease, COPD, Hypertension, Current cigarette smoker |

Yes | No | No |

| >=80 | Female | Ulcerative colitis | Severe | Mesalamine, Prednisone or prednisolone |

Hypertension | Yes | No | No |

| 60-69 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Moderate | Mesalamine | Cancer | Yes | No | No |

| 70-79 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Mild | Prednisone or prednisolone | Cardiovascular disease, Hypertension, CMV infection |

Yes | No | No |

| 60-69 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Unknown | Mesalamine, Azathioprine |

Cardiovascular disease, Diabetes, Hypertension |

Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 40-49 | Female | Crohn's disease | Remission | None reported | Asthma | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 60-69 | Female | Ulcerative colitis | Remission | Sulfasalazine, Budesonide |

None reported | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 50-59 | Male | Ulcerative colitis | Remission | Mesalamine | None reported | Yes | Yes | Yes |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Meds, medications.

Note that 1 of these deaths was described in a previous case report (Mazza S, Sorce A, Peyvandi F, et al. A fatal case of COVID-19 pneumonia occurring in a patient with severe acute ulcerative colitis. Gut 2020;69:1148–1149).

References

- 1.Morens D.M., Daszak P., Taubenberger J.K. Escaping Pandora's box - another novel coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1293–1295. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2002106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onder G., Rezza G., Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy [published online ahead of print March 23, 2020]. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4683 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention [published online ahead of print February 24, 2020]. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 - United States, February 12-March 28, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:382–386. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ng S.C., Shi H.Y., Hamidi N., et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2018;390:2769–2778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torres J., Mehandru S., Colombel J.F., et al. Crohn's disease. Lancet. 2017;389:1741–1755. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31711-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ungaro R., Mehandru S., Allen P.B., et al. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389:1756–1770. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32126-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lichtenstein G.R., Loftus E.V., Isaacs K.L., et al. ACG clinical guideline: management of Crohn's disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:481–517. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2018.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuoka K., Kobayashi T., Ueno F., et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:305–353. doi: 10.1007/s00535-018-1439-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahier J.F., Magro F., Abreu C., et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:443–468. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ananthakrishnan A.N., McGinley E.L. Infection-related hospitalizations are associated with increased mortality in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirchgesner J., Lemaitre M., Carrat F., et al. Risk of serious and opportunistic infections associated with treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:337–346.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Long M.D., Martin C., Sandler R.S., et al. Increased risk of pneumonia among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:240–248. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma C., Lee J.K., Mitra A.R., et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: efficacy and safety of oral Janus kinase inhibitors for inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:5–23. doi: 10.1111/apt.15297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tinsley A., Williams E., Liu G., et al. The incidence of influenza and influenza-related complications in inflammatory bowel disease patients across the United States: 1833. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013:108. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michot J.M., Albies L., Chaput N., et al. Tocilizumab, an anti-IL6 receptor antibody, to treat Covid-19-related respiratory failure: a case report. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:961–964. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X., Song K., Tong F., et al. First case of COVID-19 in a patient with multiple myeloma successfully treated with tocilizumab. Blood Advances. 2020;4:1307–1310. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of Coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang W., Guan W., Chen R., Wang W., et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazza S., Sorce A., Peyvandi F., et al. A fatal case of COVID-19 pneumonia occurring in a patient with severe acute ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2020;69:1148–1149. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenks G. The data model concept in statistical mapping. Int Yearb Carto. 1967;7:186–190. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner D., Huang Y., Martín-de-Carpi J., et al. COVID-19 and paediatric inflammatory bowel diseases: global experience and provisional guidance (March 2020) from the Paediatric IBD Porto group of ESPGHAN. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;70:727–733. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.[The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China] Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:145–151. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus Disease 2019 Cases in U.S. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html Available at: Published April 16, 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020.

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Provisional Death Counts for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/ Available at: Published April 17, 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020.

- 26.Russell C.D., Millar J.E., Baillie J.K. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet. 2020;395:473–475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30317-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldmann M., Maini R.N., Woody J.N., et al. Trials of anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy for COVID-19 are urgently needed. Lancet. 2020;395:1407–1409. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30858-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]