Abstract

Objective:

The objective was to describe characteristics of civil monetary penalties levied by the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) related to violations of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) involving psychiatric emergencies.

Methods:

Descriptions of EMTALA-related civil monetary penalty settlements from 2002 to 2018 were obtained from the OIG. Cases related to psychiatric emergencies were identified by inclusion of key words in settlement descriptions. Characteristics of settlements involving EMTALA violations related to psychiatric emergencies including date, amount, and nature of the allegation were described and compared with settlements not involving psychiatric emergencies.

Results:

Of 230 civil monetary penalty settlements related to EMTALA during the study period, 44 (19%) were related to psychiatric emergencies. The average settlement for psychiatric-related cases was $85,488, compared with $32,004 for non–psychiatric-related cases (p < 0.001). Five (83%) of the six largest settlements during the study period were related to cases involving psychiatric emergencies. The most commonly cited deficiencies for settlements involving psychiatric patients were failure to provide appropriate medical screening examination (84%) or stabilizing treatment (68%) or arrange appropriate transfer (30%). Failure to provide stabilizing treatment was more common among cases involving psychiatric emergencies (68% vs. 51%, p = 0.041). Among psychiatric-related settlements, 18 (41%) occurred in CMS Region IV (Southeast) and nine (20%) in Region VII (Central).

Conclusions:

Nearly one in five civil monetary penalty settlements related to EMTALA violations involved psychiatric emergencies. Settlements related to psychiatric emergencies were more costly and more often associated with failure to stabilize than for nonpsychiatric emergencies. Administrators should evaluate and strengthen policies and procedures related to psychiatric screening examinations, stabilizing care of psychiatric patients boarding in EDs, and transfer policies. Recent large, notable settlements related to EMTALA violations suggest that there is considerable room to improve access to and quality of care for patients with psychiatric emergencies.

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) is a landmark federal law governing emergency care.1 Passed in 1986 in response to highly publicized incidents of inadequate, delayed, or denied treatment of uninsured patients by emergency departments (EDs),2,3 EMTALA requires that patients presenting to a dedicated ED have a timely medical screening evaluation, stabilization of emergency medical conditions, and transfer to another facility for higher level of care if required stabilizing services are unavailable at the original facility.4 Receiving hospitals have a duty to accept transfer of patients requiring specialty care if the facility has an on-call specialist and capacity to treat the patient.4 EMTALA applies to all hospitals with Medicare provider agreements, and enforcement is conducted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). In the past decade, CMS has clarified that 1) EMTALA applies to psychiatric emergencies,5 2) many psychiatric evaluation areas qualify as dedicated EDs,5 and 3) psychiatric hospitals participating in Medicare are obligated to accept an appropriate transfer of patients requiring specialized psychiatric care for stabilization whether or not the facility has an area qualifying as a dedicated ED.6

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services regional offices authorize EMTALA investigations, issue citations for violations, and determine whether a facility has an adequate corrective action plan to ensure future compliance so that a citation can be resolved. The ultimate consequence of failure to resolve an EMTALA citation is termination of the Medicare provider agreement, which almost universally results in hospital closure.7 This is not a theoretical risk; more than a quarter of U.S. hospitals were cited for EMTALA violations over the past decade, although most resolved citations without Medicare provider agreement termination.7 Between 2005 and 2014, there were 355 citations for EMTALA violations related to psychiatric emergencies.7 Among 12 hospitals with Medicare provider agreements terminated for failure to comply with EMTALA, four cases (25%) involved EMTALA violations related to psychiatric emergencies.7 The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) of the Department of Health and Human Services receives information about EMTALA violations from CMS and may seek civil monetary penalties against hospitals or individual physicians that have violated EMTALA.8 Civil monetary penalty cases are resolved through settlement agreements, and hospitals and individual physicians can be held liable for penalties not covered by malpractice insurance. The historic maximum civil monetary penalty of $50,0004 for an EMTALA violation increased to $103,139 in 2016.9 Approximately 7.9% of EMTALA violations result in a civil monetary penalty.10

Psychiatric complaints comprise a significant and increasing proportion of ED visits.11-14 In 2011 there were 2.5 million ED visits for complaints related to mental health disorders, representing a 20% increase from 5 years prior.12 A concurrent decline in availability of inpatient psychiatric beds has led to an increase in prolonged boarding of psychiatric patients on involuntary commitments in EDs awaiting transfer to available inpatient psychiatric beds.15,16 As the number of patients seeking care for emergent psychiatric conditions increases, evaluating EMTALA enforcement for cases related to psychiatric conditions will be crucial to informing and identifying areas in which emergency psychiatric care can be improved. Characteristics of civil monetary penalties related to EMTALA violations involving psychiatric emergencies have not previously been described. The goal of this investigation is to describe characteristics of civil monetary penalty settlements levied by the OIG related to EMTALA violations involving psychiatric emergencies between 2002 and 2018.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Sources

This is a retrospective observational study evaluating EMTALA-related civil monetary penalty settlements from 2002 to 2018. Case descriptions of all civil monetary penalty settlements between 2002 and December 11, 2018, were obtained from the OIG.17-19 Civil monetary penalty settlements related to EMTALA violations specifically were identified by inclusion of the terms “EMTALA” or “patient dumping” in the title or text of the settlement description for inclusion, consistent with prior work in this field.20 OIG civil monetary penalty settlements unrelated to EMTALA (e.g., kickback allegations, fraudulent Medicare claims) were excluded from analysis. Entries included the settlement amount, location, and brief description of the involved patient’s medical and/or psychiatric condition and clinical course. Locations were categorized by CMS region, the level at which EMTALA is enforced. A map depicting CMS regions is included in Data Supplement S1, Figure S1 (available as supporting information in the online version of this paper, which is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/acem.13710/full).21

Identification of Cases Involving Psychiatric Emergencies

Settlements related to psychiatric conditions were identified by searching the text of the case settlement descriptions with the key words and stems psych-, depress-, suicid-, overdos-, mentally ill, emotional distress, overdose, and Baker Act. The Baker Act is a Florida Mental Health Act allowing for involuntary evaluation of an individual who possibly has a mental illness and is in danger of harm to self or others or of self-neglect. Settlements imposed upon dedicated psychiatric facilities were also included. Each case description was reviewed and coded by two authors (EB, ST), and kappa statistics were calculated to evaluate for inter-reliability for identification of psychiatric cases.22

Recording of Case Features

Date, location, and settlement amounts for each case were recorded. Settlement descriptions were reviewed to determine if there was stated 1) failure to provide appropriate medical screening examination, 2) failure to provide stabilizing treatment, 3) failure to arrange appropriate transfer, 4) failure to accept appropriate transfer for specialty services, or 5) failure of an on-call doctor to respond. These categories correspond to EMTALA deficiency tags involving clinical care. A list of deficiency tags and categories is included in Data Supplement S1, Table S1.

Data Analysis

Characteristics of cases resulting in OIG settlements were compared between those involving psychiatric emergencies and nonpsychiatric emergencies with t-tests, chi-square tests, and Fisher’s exact tests as indicated. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata/MP13 (StataCorp, 2013). The institutional review board at the University of Southern California has reviewed and approved the study.

Case Study

The largest OIG settlement related to an EMTALA violation involving a psychiatric emergency was identified and details of the EMTALA investigation are described to provide an illustrative case study. Reports from the EMTALA investigation including the facility’s proposed corrective actions were obtained from CMS via Freedom of Information Act Request. Individual patient-level identifiers were redacted in documents provided. News reports related to this EMTALA violation were examined to provide better understanding of the context in which the hospital operates. Investigation findings and facility corrective actions from this case are summarized to provide a richer example of the EMTALA enforcement process and hospital response to citation for an EMTALA violation.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Civil Monetary Penalties Related to Psychiatric Emergencies

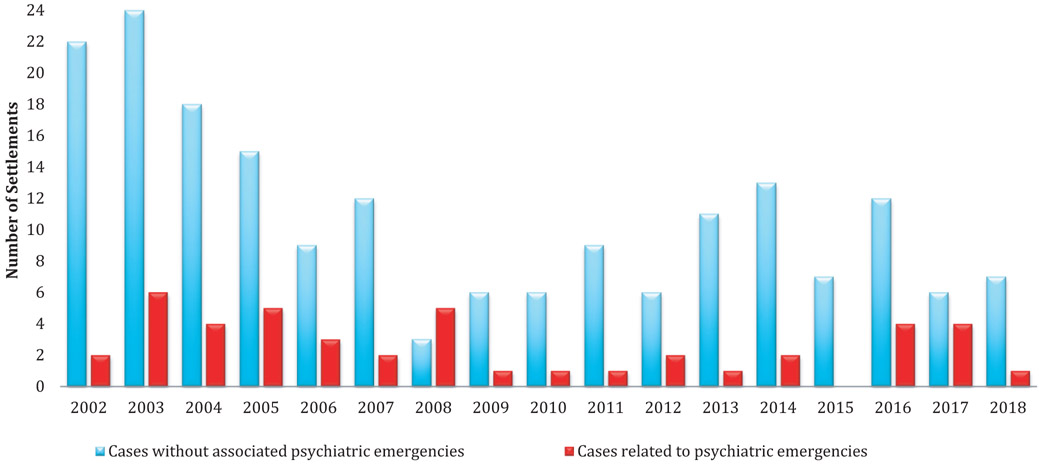

Between 2002 and 2018, a total of 230 civil monetary penalty settlements related to EMTALA were identified. Of these, 222 (97%) were levied against facilities and eight (3%) against individual physicians. We identified 44 (19%) of all civil monetary penalty settlements related to EMTALA involved psychiatric emergencies. The kappa inter-rater reliability for identification of psychiatric cases was 0.986, with the sole case with initial disagreement determined by consensus to be related to a psychiatric condition. All 44 of these settlements related to psychiatric emergencies were levied against hospitals and none against individual physicians. The number of annual settlements related to psychiatric and nonpsychiatric emergencies is graphically depicted in Figure 1. We observe a general decline in the number of annual OIG settlements for nonpsychiatric emergencies during the study period, while the number of settlements related to psychiatric emergencies appears relatively stable. Characteristics of OIG settlements related to EMTALA violations involving psychiatric emergencies are included in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Civil monetary penalty settlements related to EMTALA violations, 2002 to 2018. EMTALA = Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act.

Table 1.

Characteristics of EMTALA-related Civil Monetary Penalty Settlements, 2002 to 2018

| Psychiatric | Nonpsychiatric | p-value | Statistical test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number | 44 | 186 | ||

| Settlement (mean dollars) | $85,488 | $32,004 | 0.003 | t-test |

| Settlement against physician | 0 (0) | 8 (4) | 0.036 | Fisher’s exact test |

| Minor involved | 6 (14) | 24 (13) | 0.897 | Pearson chi-square |

| Failure to provide MSE | 37 (84) | 137 (74) | 0.147 | Pearson chi-square |

| Failure to stabilize | 30 (68) | 95 (51) | 0.041 | Pearson chi-square |

| Failure to arrange transfer | 13 (30) | 40 (22) | 0.363 | Pearson chi-square |

| Failure to accept transfer | 6 (14) | 28 (15) | 0.812 | Pearson chi-square |

| On-call failed to respond | 0 (0) | 14 (8) | 0.078 | Fisher’s exact test |

| CMS region | 0.456 | Fisher’s exact test | ||

| 1 | 1 (2) | 5 (3) | ||

| 2 | 0 (0) | 8 (4) | ||

| 3 | 3 (7) | 1 (1) | ||

| 4 | 15 (34) | 80 (43) | ||

| 5 | 4 (9) | 20 (11) | ||

| 6 | 8 (18) | 20 (11) | ||

| 7 | 2 (5) | 25 (13) | ||

| 8 | 0 (0) | 6 (3) | ||

| 9 | 5 (11) | 27 (15) | ||

| 10 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Data are reported as n (%).

CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; EMTALA = Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act; MSE = medical screening examination.

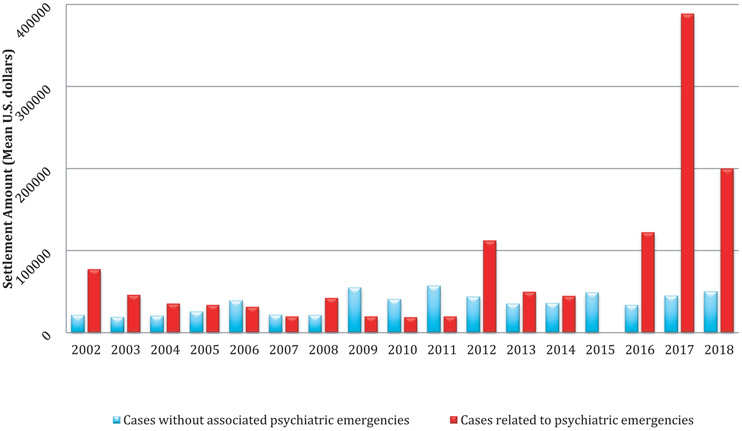

Average settlements related to psychiatric emergencies have increased in recent years, particularly in comparison to settlements not related to psychiatric conditions (Figure 2). The average psychiatric-related settlement ($85,488) was significantly higher than the mean amount for nonpsychiatric cases ($32,004; p = 0.003). Of six settlements for more than $100,000, five (83%) were related to cases involving psychiatric emergencies. The three largest civil monetary penalties settlements related to EMTALA violations during the study period all involved psychiatric emergencies and occurred in recent years. The three largest cases were settlements for $360,000 in 2016, $1,295,000 in 2017, and for $200,000 in 2018. Each of these cases involved several patients and serious violations of the EMTALA law. By comparison, the largest civil monetary penalty settlement related to an EMTALA violation for a nonpsychiatric case was for $170,000. After excluding the top three settlements from analysis, the mean for the remainder of settlements related to psychiatric emergencies ($46,500) was still significantly higher than settlements for nonpsychiatric cases (p = 0.008).

Figure 2.

Civil monetary penalty settlement amounts related to EMTALA violations, 2002 to 2018. EMTALA = Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act.

Failure to provide stabilizing treatment was cited in 30 of 44 (68%) cases involving psychiatric emergencies, compared with only 95 of 186 (51%) nonpsychiatric cases (p = 0.041). When comparing settlements for psychiatric emergencies to those without psychiatric emergencies, no difference in proportions was found for CMS region, involvement of a minor, failure to provide medical screening examination, failure to arrange appropriate transfer, or failure of an on-call provider to respond. Of the 44 civil monetary penalties related to psychiatric emergencies, 18 (41%) occurred in CMS Region IV, including nine (50%) in Florida and six (33%) in North Carolina. Region VII accounted for nine (20%) settlements related to psychiatric emergencies with seven (78%) imposed upon Missouri hospitals.

CASE STUDY

To provide a richer example of the EMTALA enforcement process and hospital response to citation for an EMTALA violation, investigation findings and facility corrective actions from the EMTALA investigation related to the largest OIG civil monetary penalty settlement involving a psychiatric emergency are included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Case Study

| In response to news media reports of psychiatric patients boarding for 38 days in an ED,23 CMS launched an EMTALA investigation against a hospital in the Southeast.24 After reviewing hospital records, investigators identified 36 EMTALA violations involving failure to provide appropriate screening examination, failure to provide appropriate stabilizing treatment, and failure to arrange appropriate transfer for patients with emergency psychiatric conditions.19 Per the OIG, “In these incidents, individuals presented to the hospital’s ED with unstable psychiatric emergency medical conditions. Instead of being examined and treated by an on-call psychiatrist, and despite empty beds in its psychiatric unit to which the patients could have been admitted for stabilizing treatment, the patients were involuntarily committed and kept in the ED for between 6 and 38 days each.”19 This facility is an important health care access center for patients in the region, as it is the only hospital operating in its county and the major referral center for eight counties.25 The hospital is located in the Appalachian foothills and serves a predominantly white population, with 15% living below the poverty level.26 It is the flagship of the largest private not-for-profit health care system in the state and the largest employer in the county and has been in operation for more than 100 years.25 While the patients in the investigation received medical screening examinations by an emergency physician, the facility was cited for failing to obtain psychiatric screening examinations. The report indicates that the on-call psychiatrist was not following the medical staff rules and regulation regarding urgent consultations (a 2-hour requirement). Additionally, although the on-call psychiatrist was prescribing treatment modalities to the ED provider when requested, CMS noted that they were not providing stabilizing treatment on a daily basis to the patients in the ED. Proposed corrective actions included reeducation of staff about requirements for psychiatrists to 1) see all involuntary hold patients in the ED upon commitment and 2) assume responsibility for the psychiatric care of involuntarily committed patients to provide stabilizing treatment until the patient is admitted for appropriate psychiatric care or transferred to another facility accepting involuntary commitment patients or discharged to an alternative safe environment. Additionally, policies were updated to require medical staff psychiatric providers to see the patients being held for capacity reasons in the ED each day until an appropriate admission, transfer, or discharge is arranged. |

| Regarding stabilization, the facility was noted to have an inpatient behavioral health unit licensed for 38 beds with capacity for additional patients while many of the psychiatric patients were boarding in the ED awaiting transfer to a state mental health facility. Although the hospital’s inpatient psychiatric facility had by policy and practice previously only accepted voluntary admissions, and only 28 of their 38 licensed beds were routinely staffed, CMS determined that the hospital had capability (available on-call psychiatric and psychiatric services) and capacity (available inpatient psychiatric beds on a behavioral health unit) to provide the psychiatry treatment and milieu needed for patients. CMS deemed the transfers inappropriate given that the sending facility had the capability to provide the same level of care as the receiving facility. In response to the EMTALA citations, the hospital proposed corrective actions including revising hospital policies to allow for admission of both voluntary and involuntary patients to the hospitals’ inpatient psychiatric unit and increasing the number of staffed beds in the unit to 34.27 On June 23, 2017, the hospital entered into a $1,295,000 civil monetary penalty settlement agreement with OIG related to violations of the EMTALA law for this case.19 |

CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; EMTALA = Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act; OIG = Office of the Inspector General

DISCUSSION

Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act is a landmark federal law governing emergency care,1 and in the past decade CMS has clarified that the law applies not only to medical emergencies and EDs, but also to psychiatric emergencies, many psychiatric intake areas, and inpatient psychiatric facilities as well.5,6 Since 2002, the OIG has reached 44 civil monetary penalty settlements related to EMTALA violations involving psychiatric emergencies. Generally, we found that civil monetary penalties for EMTALA violations related to psychiatric emergencies are associated with higher settlement amounts and are more likely to involve failure to provide stabilization compared to cases not involving psychiatric emergencies. Civil monetary penalty settlements involving psychiatric emergencies tend to concentrate in a few CMS regions. Study findings and the case study described highlight a number of key points important for hospital administrators, emergency physicians, and psychiatrists providing emergency and inpatient services to be aware of.

First, civil monetary penalties increased in amount in recent years, especially for cases involving psychiatric emergencies. For the majority of the study period, the maximum OIG civil monetary penalty for an EMTALA violation was set at $50,000, which approximately doubled in 2016.9 Multiple settlements for hundreds of thousands of dollars, with one for over a million dollars, indicate that the OIG has been stacking penalties for multiple violations identified during a single investigation. This is particularly true for cases involving psychiatric emergencies. Of the six settlements during the study period for more than $100,000, five involved psychiatric emergencies. EMTALA-related civil monetary penalties for psychiatric emergencies had a mean settlement amount of $85,488, more than double the average amount for settlements for nonpsychiatric emergencies.

Many evaluation areas at psychiatric facilities where patients are evaluated for emergent conditions on an unscheduled basis qualify as dedicated EDs and are required to comply with EMTALA if located within a hospital with a Medicare provider agreement.6 Among civil monetary penalty settlements involving psychiatric emergencies, failure to provide appropriate medical screening examination was the most commonly cited cause for EMTALA citation preceding the settlement, identified in 84% of cases. While it is commonly known that EMTALA applies for patients presenting to medical EDs, it is important for hospital administrators and psychiatrists to understand that many psychiatric facilities have evaluation or intake areas that qualify as dedicated EDs and are required to comply with screening, stabilization, and transfer requirements of EMTALA.

Reports from the case study provided indicate an expectation by CMS that on-call psychiatrists (when available) be involved in the care of psychiatric patients involuntarily committed in the ED. While it is certainly within the scope of practice for an emergency physician to screen and discharge patients experiencing psychiatric issues but not meeting criteria for involuntary hold, the case study highlights an expectation for further timely screening by a mental health provider for patients determined to meet hold criteria. Specifically, on-call psychiatrists should participate in psychiatric screening examinations of patients with psychiatric emergencies involuntarily committed in the ED.

Failure to provide appropriate stabilizing treatment was the second most commonly cited cause for EMTALA citation leading to OIG settlement among patients with psychiatric emergencies, identified in more than two-thirds of these cases compared with only half of other cases. The case study described highlights the need for hospitals with the capability of providing stabilizing treatments (on call psychiatrists) to consider implementing and/or reinforcing compliance with policies requiring daily evaluation of psychiatric patients boarding in the ED on involuntary commitments for stabilizing treatment until admission or appropriate transfer can be arranged or until the patient is deemed stable for discharge. This will be particularly important as recent studies have shown that odds of boarding for psychiatric patients were nearly five times higher than for nonpsychiatric patients and that boarding times for psychiatric patients are significantly longer than for nonpsychiatric patients.28

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services recently issued EMTALA citations for inappropriate transfer for patients with psychiatric emergencies transferred to other facilities when inpatient beds within the sending hospital’s behavioral health unit were available and considered by CMS to represent the same level of care. Nearly one-third of OIG settlements in our study were cited for failure to arrange appropriate transfer. In the case study described, although the hospital’s inpatient psychiatric facility had by policy and practice previously only accepted voluntary admissions, CMS determined that because the hospital had available inpatient beds on a behavioral health unit, it had capacity to provide the psychiatry treatment and milieu needed to help stabilize patients with psychiatric emergencies, although the boarding patients were involuntarily committed. This case highlights the need for hospitals with inpatient behavioral health units to reevaluate exclusions to their admission policies, particularly when they have available beds and affiliated EDs are boarding patients with psychiatric emergency conditions.

In our study, approximately one in seven cases involving psychiatric emergencies referred to failure to accept appropriate transfer for specialized services. While inpatient psychiatric facilities without areas that qualify as a dedicated ED may not be obligated to adhere to other aspects of EMTALA (e.g., providing medical screening examinations), they are required to accept appropriate transfer of patients from another ED with emergent psychiatric conditions requiring specialized treatment if they have Medicare provider agreements. CMS has also clarified that a recipient hospital’s EMTALA obligation does not extend to patients admitted of another hospital.6

Office of the Inspector General settlements related to psychiatric conditions concentrate in two of the 10 CMS regions (IV and VII), with half occurring in three states (Florida, North Carolina, and Missouri). This is consistent with prior published work showing both high rates of EMTALA citations and subsequent OIG settlements in the same regions.10,29 Further work is needed to determine if the high rates of civil monetary penalty settlements in these regions reflect inadequate psychiatric emergency care or enhanced enforcement.

In recent years, EMTALA violations for patients with psychiatric emergencies have resulted in several record-breaking civil monetary penalties. Although we did not identify any civil monetary penalties against individual physicians related to psychiatric emergencies in this or prior studies,20 it is important that both physicians and hospital administrators be diligent to ensure appropriate patient care and that facilities are compliant with the EMTALA statute particularly for patients with psychiatric emergencies.

LIMITATIONS

Our study has some limitations worth noting. First, reported findings rely on administrative data provided by the OIG and may be limited by variability in reporting and enforcement of EMTALA cases related to psychiatric emergencies across regions or over time. However, the information analyzed represents the best available data source to study OIG penalties, and we have no reason to suspect systematic error in recording or reporting of data by the OIG. Second, available data only included EMTALA cases resulting in civil monetary penalty settlement agreements. It is possible that cases for which penalties were recommended, but for which a settlement agreement was not reached, were not reported. Third, as published settlement descriptions varied considerably in length and detail across the study period, it is possible that some descriptions were sufficiently vague such that settlements related to psychiatric emergencies may not have been identified using our methods. However, in the vast majority of OIG settlement descriptions, the nature of the condition was indicated, and the proportion of settlements related to psychiatric emergencies (19%) was similar to the proportion of overall EMTALA citations involving psychiatric emergencies identified in our prior work (17%).7

CONCLUSIONS

Nearly one in five civil monetary penalties related to Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act violations involved psychiatric emergencies. Settlements related to psychiatric conditions concentrate in two of the 10 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services regions, with half of all settlements occurring in three states (Florida, North Carolina, and Missouri). Average financial penalties related to psychiatric emergencies were over twice as high as penalties for nonpsychiatric complaints. Recent large penalties related to violations of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act law underscore the importance of improving access to and quality of care for patients with psychiatric emergencies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Adam Gomez for his contribution with data management and review and Raquel Martinez for her assistance with creation of tables and figures.

Dr. Terp began this work while supported by an F32 Postdoctoral Training Award from the AHRQ (F32 HS022402-01). ST, BW, EB, DC, SS, and MM report no conflict of interest. ST, SS, and MM recently received a grant from the AHRQ (R03 HS 25281-01A1) to support a separate EMTALA-related project but do not believe this to represent a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

The authors have no relevant financial information or potential conflicts to disclose.

Presented at the American College of Emergency Medicine Research Forum, San Diego, CA, October 1, 2018.

Supporting Information

The following supporting information is available in the online version of this paper available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/acem.13710/full

Data Supplement S1. Supplemental material.

References

- 1.Rosenbaum S, Cartwright-Smith L, Hirsh J, Mehler PS. Case studies at Denver Health: ‘patient dumping’ in the emergency department despite EMTALA, the law that banned it. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1749–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiff RL, Ansell DA, Schlosser JE, Idris AH, Morrison A, Whitman S. Transfers to a public hospital. A prospective study of 467 patients. N Engl J Med 1986;314:552–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ansell DA. Patient dumping. Status, implications, and policy recommendations. JAMA 1987;257:1500–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Code § 1395dd. Examination and treatment for emergency medical conditions and women in labor. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.CMS. Appendix V Interpretive Guidelines - Responsibilities of Medicare Participating Hospitals in Emergency Cases. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.CMS. Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) 2009 Final Rule Revisions to Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) Regulations. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terp S, Seabury SA, Arora S, Eads A, Lam CN, Menchine M. Enforcement of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act, 2005 to 2014. Ann Emerg Med 2017;69(155–62):e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Civil Monetary Penalties and Affirmative Exclusions. 2018. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/enforcement/cmp/background.asp. Accessed September 1, 2018.

- 9.Annual Civil Monetary Penalties Inflation Adjustment(82 FR § 9174). 2016.

- 10.Zuabi N, Weiss LD, Langdorf MI. Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) 2002-15: review of Office of Inspector General patient dumping settlements. West J Emerg Med 2016;17:245–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayangbayi T, Okunade A, Karakus M, Nianogo T. Characteristics of hospital emergency room visits for mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv 2017;68:408–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capp R, Hardy R, Lindrooth R, Wiler J. National trends in emergency department visits by adults with mental health disorders. J Emerg Med 2016;51(131–5):e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owens PL, Mutter R, Stocks C. Mental Health and Substance Abuse-Related Emergency Department Visits among Adults, 2007: Statistical Brief #92 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss AJ, Barrett ML, Heslin KC, Stocks C. Trends in Emergency Department Visits Involving Mental and Substance Use Disorders, 2006–2013: Statistical Brief #216 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torrey E, Fuller D, Geller J, Jacobs C, Rastoga K. No Room at the Inn: Trends and Consequences of Closing Public Psychiatric Hospitals. Arlington, VA: Treatment Advocacy Center, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuller DA, Siniclair E, Geller J, Quanbeck C, Snook J. Going, Going, Gone: Trends and Consequences of Eliminating State Psychiatric Beds. Arlington, VA: Treatment Advocacy Center, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Civil Monetary Penalties: Patient Dumping. http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/enforcement/cmp/patient_dumping.asp. Accessed December 9, 2015.

- 18.Patient Dumping Archives. http://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/archives/enforcement/patient_dumping_archive.asp. Accessed March 7, 2016.

- 19.Civil Monetary Penalties and Affirmative Exclusions. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/enforcement/cmp/. Accessed December 11, 2018.

- 20.Terp S, Wang B, Raffetto B, Seabury SA, Menchine M. Individual physician penalties resulting from violation of Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act: a review of office of the inspector general patient dumping settlements, 2002-2015. Acad Emerg Med 2017;24:442–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.CMS Regional Map. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landis JR, Koch GG. An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics 1977;33:363–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armour S South Carolina Psychiatric Patient Stuck 38 Days in ER. Bloomberg News July 17, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.CMS. CMS Region IV investigation report and related correspondence related to EMTALA investigation SC00023639. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Obtained via Freedom of Information Act. [Google Scholar]

- 25.AnMed Health. Available at: http://anmedhealth.org/About. Accessed August 1, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.QuickFacts. Anderson County, South Carolina: Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/andersoncountysouthcarolina/PST045217. Accessed September 1, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer H S.C. Hospital to Pay $1.3 Million for Not Properly Treating Emergency Psych Patients. Modern Healthcare, July 5, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nolan JM, Fee C, Cooper BA, Rankin SH, Blegen MA. Psychiatric boarding incidence, duration, and associated factors in United States emergency departments. J Emerg Nurs 2015;41:57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eads A, Terp S, Arora S, Menchine M. Regional Variation in EMTALA Violations from 2004 to 2013. Acad Emerg Med 2015;22(S1). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.